Abstract

Background

Post-mortem studies have not identified an association between beta-amyloid or tau and rates of hippocampal atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. TAR DNA binding protein of 43kDa (TDP-43) is another protein recently linked to Alzheimer’s disease. We aimed to determine whether hippocampal TDP-43 is associated with faster rates of hippocampal atrophy.

Methods

Two-hundred ninety-eight autopsied cases with Alzheimer’s spectrum disease that had antemortem head MRI scans between 1/1/1999–12/31/2012 recruited into the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center or Patient Registry/Study of Aging were analyzed. TDP-43 immunohistochemistry was performed and cases classified as follows: no TDP-43; TDP-43 restricted to amygdala; and TDP-43 spreading into hippocampus. Eight-hundred sixteen MRI scans, spanning 1.0–11.2 years prior to death, were analyzed. We utilized longitudinal FreeSurfer and tensor-based morphometry with symmetric normalization to calculate hippocampal volume on all serial MRI and performed linear mixed-effects regression models to estimate associations between TDP-43 and rate of hippocampal atrophy, and determine the trajectory of TDP-43 associated atrophy.

Findings

One-hundred forty-one cases showed no TDP-43, 33 had TDP-43 restricted to the amygdala and 124 had TDP-43 in hippocampus. Cases with hippocampal TDP-43 had faster rates of hippocampal atrophy compared to cases with amygdala-only TDP-43 and those without TDP-43 in cases with an intermediate-high likelihood of having Alzheimer’s disease (N=261). Hippocampal TDP-43 was not associated with rate of hippocampal atrophy in cases with low likelihood of having Alzheimer’s disease (N=37). The trajectory analysis suggested that increased rates of TDP-43 associated hippocampal atrophy may be occurring at least 10-years before death. Results were similar for FreeSurfer and tensor-based morphometry.

Interpretation

In Alzheimer’s disease, TDP-43 should be considered a potential factor related to increased rates of hippocampal atrophy. Given the importance of hippocampal atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease, it is imperative that we develop techniques for detecting TDP-43 pathology in-vivo.

Funding

National Institute of Aging

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease is a neurodegenerative condition characterized by the presence of two abnormal proteins, beta-amyloid and tau. Hippocampal atrophy is one of the main features of Alzheimer’s disease. Cross-sectional MRI-histological studies of Alzheimer’s disease have found smaller hippocampal volumes to be associated with beta-amyloid1 and tau deposition1,2. Over time, patients with Alzheimer’s disease classically show increased rates of hippocampal atrophy3. Not surprising therefore, is the belief that hippocampal atrophy is related to beta-amyloid and tau. Intriguingly, two longitudinal MRI-histological studies have assessed whether rates of hippocampal atrophy are associated with beta-amyloid and tau, and surprisingly, neither study found an association with either protein4,5. Given that hippocampal atrophy is one of the key features of Alzheimer’s disease, it is of dire importance to understand the basis of increased hippocampal atrophy rates.

Over the past decade, it has been debated whether a third protein may also contribute to the Alzheimer’s disease neurodegenerative process. This protein, the TAR DNA binding protein of 43kDa (TDP-43) was originally reported to be associated with only two neurodegenerative diseases, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal lobar degeneration6. Subsequent studies however, reported finding TDP-43 in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease7, with TDP-43 reported in over 65% of cases of Alzheimer’s disease in some series8. In cross-sectional studies, TDP-43 in Alzheimer’s disease has also been associated with smaller hippocampal volume on MRI closest to death9. Hence, TDP-43 is becoming an important player in the Alzheimer’s disease field.

We have shown that TDP-43 when deposited in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease follows a stereotypical pattern10. TDP-43 appears to first be deposited in the amygdala (stage 1), followed by the subicular region of the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex (stage 2), then the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus and occipitotemporal cortex (stage 3), then ventral striatum, basal forebrain, insular and inferior temporal cortex (stage 4), brainstem regions (stage 5) and middle frontal cortex and basal ganglia (stage 6)11. It is unknown whether TDP-43 is associated with faster rates of hippocampal atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease, and whether such an association is dependent on TDP-43 spreading into the hippocampus. To address these unknowns, we perform an MRI-histological analysis to determine whether the spread of TDP-43 into the hippocampus is associated with faster rates of hippocampal atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. We hypothesize that TDP-43 deposition in the hippocampus would be associated with faster rates of hippocampal atrophy.

METHODS

Subject selection

We identified all cases that had been prospectively followed in the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center or Patient Registry/Study of Aging, had died with a brain autopsy between January 1st 1999 and December 31st 2012, had received an Alzheimer’s disease spectrum pathologic diagnosis according to the National Institute of Aging-Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) diagnostic criteria (Braak stage≥1)12, had a complete set of available paraffin blocks of brain tissue for TDP-43 analysis and had at least one usable antemortem volumetric head MRI. Cases with a pathological diagnosis of any other neurodegenerative disease, such as frontotemporal lobar degeneration or Lewy body disease were excluded. Only one case with Braak stage 0 was excluded. We identified 298 cases meeting these criteria with a total of 816 usable MRI scans, spanning 1.0–11.2 years of the disease, available for analysis. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotyping was performed.

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic IRB. Prior to death, all subjects or their proxies had provided written consent for brain autopsy examination.

Pathological Analysis

All 298 cases had undergone pathological examination according to the recommendations of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s disease13 and each case had been assigned a Braak and Braak neurofibrillary tangle stage14. For this study we followed the recommendations of the NIA-AA for the staging of neurofibrillary tangle deposition using AT8 tau immunohistochemistry12. Hence, all cases were classified as neurofibrillary tangle stages B1, B2 or B3 based on the following: B1 (transentorhinal stage) = Braak I+II, B2 (limbic stage) = Braak III+IV and B3 (isocortical stage) = Braak V+VI. Amyloid status was classified as A0 (Thal=0) or A1 (Thal≥1) according to NIA-AA. Hippocampal sclerosis was diagnosed based on the presence of neuronal loss in the subiculum and CA1 regions of the hippocampus out of proportion to the observable burden of extracellular neurofibrillary tangle pathology, based on consensus recommendations15.

Assessment of TDP-43

For this study, all 298 cases were assessed for the presence of TDP-43 as previously described9. We screened the amygdala given that the amygdala has been shown to be first affected in Alzheimer’s disease10,11. For all cases in which TDP-43 was observed in the amygdala, we subsequently assessed for the presence of TDP-43 in the hippocampus (subiculum, CA1 and dentate fascia). All cases were then classified as: TDP-43 stage 0 = those without any TDP-43 immunoreactivity; TDP-43 stage 1 = those with TDP-43 restricted to the amygdala; and TDP-43 stage≥2 = those with TDP-43 in hippocampus with or without lesions elsewhere. This categorization was used to allow the TDP-43 effect to vary by stage 0 versus stage 1 versus stage≥2. The grouping of those in stages 2 and above was based on the commonality of hippocampal TDP-43 and to keep the analyses tractable.

MRI analysis

All MRI were performed using a standardized protocol that included a T1-weighted 3-dimensional volumetric sequence. While some subjects had been scanned at 1.5T and some at 3T (Table 1), longitudinal analyses were always run using sets of serial scans performed at the same field strength. All images underwent pre-processing that included corrections for gradient non-linearity and intensity inhomogeneity16.

Table 1.

Demographics of subjects by TDP-43 stages

| TDP Stage 0 (N=141) |

TDP Stage 1 (N=33) |

TDP Stage ≥ 2 (N=124) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Female | 72 (51%) | 20 (61%) | 72 (58%) | 0.41 |

| Education, yrs. | 14 [12, 16] | 13 [12, 16] | 14 [12, 16] | 0.86 |

| Age at death, yrs. | 83 [75, 90] | 86 [79, 90] | 87 [82, 93] | 0.001* |

| APOE ε4 carrier | 58 (41%) | 19 (58%) | 73 (59%) | 0.01 |

| Mini-Mental State Examination | 22 [10, 28] | 25 [17, 27] | 14 [9, 20] | 0.0001 |

| NIA-AA neurofibrillary tangle stage | 0.0005* | |||

| B1 | 26 (18%) | 7 (21%) | 4 (3%) | |

| B2 | 33 (23%) | 6 (18%) | 17 (14%) | |

| B3 | 82 (58%) | 20 (61%) | 103 (83%) | |

| Presence of amyloid | 122 (87%) | 26 (79%) | 121 (98%) | 0.0010.0002 |

| Presence of hippocampal sclerosis | 8 (6%) | 3 (9%) | 57 (46%) | 0.0001 |

| No. of scans | 2 [1, 3] | 3 [2, 4] | 2 [1, 4] | 0.06 |

| Distribution of MRI scans | 0.08 | |||

| 1 scan | 41 (29%) | 6 (18%) | 41 (33%) | |

| 2 scans | 38 (27%) | 5 (15%) | 32 (26%) | |

| 3 scans | 30 (21%) | 7 (21%) | 16 (13%) | |

| 4+ scans | 32 (23%) | 15 (45%) | 35 (28%) | |

| Distribution of field strength | 0.06* | |||

| No. subjects with 1.5T only | 108 (77%) | 28 (85%) | 110 (89%) | |

| No. subjects with 3T only | 23 (16%) | 2 (6%) | 8 (6%) | |

| No. subjects with both 1.5 and 3T | 10 (7%) | 3 (9%) | 6 (5%) | |

| MRI scan duration, yrs. | 2.9 [1.9, 4.5] | 4.0 [2.7, 6.1] | 2.8 [1.6, 4.9] | 0.17 |

| Within subjects with 2 MRI scans | 1.3 [1.1, 2.4] | 1.1 [1.0, 1.2] | 1.4 [1.1, 1.8] | 0.26 |

| Within subjects with 3 MRI scans | 2.8 [2.3, 4.1] | 3.3 [2.7, 3.9] | 2.3 [2.2, 2.7] | 0.10 |

| Within subjects with ≥ 4 MRI scans | 5.0 [4.1, 6.4] | 5.4 [4.1, 8.3] | 5.0 [4.3, 6.1] | 0.71 |

| Years from last scan to death | 2.9 [1.5, 5.0] | 2.0 [1.0, 3.9] | 3.9 [2.1, 6.4] | 0.0010.0005* |

Group-wise comparisons were performed using Fisher's Exact and Kruskal-Wallis Rank Sum Tests. Data shown are median [quartiles] or N (%).

Presence of amyloid was defined as Thal stage ≥1

Variable is accounted for in analyses.

Serial hippocampal volumes were calculated using FreeSurfer software version 5.3.0 (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/)17. All scans were first run through the FreeSurfer cross-sectional pipeline, followed the longitudinal pipeline. For subjects with only one MRI, hippocampal volumes were calculated from the cross-sectional FreeSurfer pipeline. To ensure that our results were not biased by a specific measurement technique, serial hippocampal volumes were also calculated using tensor-based morphometry run using symmetric normalization18 (TBM-SyN) using Advanced Normalization Tools (ANTs) (http://picsl.upenn.edu/software/ants) and Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM5) (www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) software19. The automated anatomical labelling atlas was used to obtain hippocampal grey matter volume estimates for both scans. For subjects with only one MRI, volumes were calculated using atlas-based parcellation9.

Given that TDP-43 stage 1 involves the amygdala, we also measured amygdala rates of atrophy to determine whether amygdala rates are associated with TDP-43 in the amygdala (TDP stage 1) or hippocampus (TDP stage≥2). In addition, to determine specificity, we also investigated associations between TDP-43 and rates of whole brain atrophy.

Statistical analyses

We used longitudinal linear mixed effects models to evaluate how brain volumes change over time in various pathologically defined groups. Details of our modeling approach can be found in the Supplementary Material (Appendix, p1–3) but are outlined here. Rather than fitting separate models for separate pathologically defined groups, we fit longitudinal models based on including data from all pathologically classified individuals with one or more MRI scans prior to death. A longitudinal linear mixed effects model can be considered as simultaneously estimating both cross-sectional parameters and longitudinal, or within-subject change, parameters20. Individuals with one MRI primarily contribute information to the cross-sectional parameters (e.g., brain volume prior to death) whereas individuals with multiple MRIs contribute to both cross-sectional and longitudinal parameters (e.g., rates of change over time).

We obtained rates for different pathologically defined groups via interactions in the linear mixed effects models. For our primary analysis, we obtained estimated rates of hippocampal atrophy for each TDP stage stratified by neurofibrillary tangle stage via fitting a model with all subjects and including a three-way interaction between TDP-43, neurofibrillary tangle stage, and time. For purposes of comparison, we also fit linear mixed effects models but with the log of amygdala volume or the log of whole brain volume as the response. To assess the effect of TDP-43 conditional on amyloid status, we fit a model with an interaction between TDP-43, amyloid and time, omitting neurofibrillary tangle stage.

All of our linear mixed effects models included subject-specific random intercepts and slopes and a time scale based on years from death. We included as covariates age at death, total intracranial volume (TIV), and field strength (1.5T versus 3T). We also included an interaction between age at death and time to allow an individual’s rate of atrophy to depend on his/her age at death. We log-transformed the volume estimates so that estimated change can be interpreted on an annual percentage scale.

In a follow-up analysis we classified subjects by whether they were in TDP stage 0 or 1 versus TDP stage ≥2 and modeled their hippocampal volumes over time with a model similar to our main analysis but using a restricted cubic spline with knots at -10 years, -5 years, and -1 years to allow for some non-linearity in mean hippocampal volumes over time. Due to the added complexity of fitting a non-linear term, we omitted neurofibrillary tangle stage and amyloid status from this analysis.

Given that concomitant pathologies in older individuals are likely the rule rather than the exception, in a secondary analysis we fit an additive, or main effects only, model that allowed rates of atrophy to depend on age at death, TDP-43 stage, neurofibrillary tangle stage, presence of amyloid, and presence of hippocampal sclerosis. We also assessed how the relationship between neurofibrillary tangle stage and rate of hippocampal atrophy varied by TDP-43 stage, by treating neurofibrillary tangle stage as a binary measure (B1/B2 vs. B3) and fitting a model with an interaction between TDP-43 stage and this binary variable.

All models were fit with the lmer function in the lme4 package in R. Estimates and 95% CIs were based on parametric bootstrapping of the fitted model using the sim function in the arm package with 10,000 replicates21.

Role of the funding source

The study sponsor did not have any role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

FINDINGS

One-hundred and forty-one cases were classified as TDP-43 stage 0, 33 as TDP-43 stage 1 and 124 as TDP-43 stage≥2. There were differences across TDP-43 stages in age at death, neurofibrillary tangle stage, amyloid, hippocampal sclerosis, and time from last MRI scan to death, although there were no significant differences in MRI scan duration (time from first scan to last scan) (Table 1).

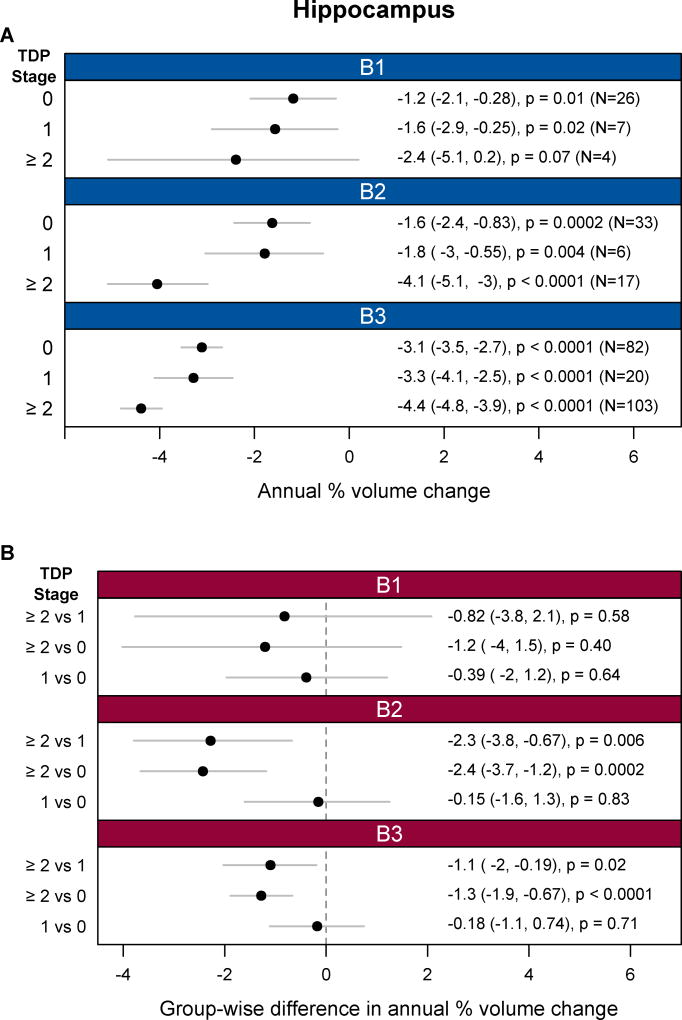

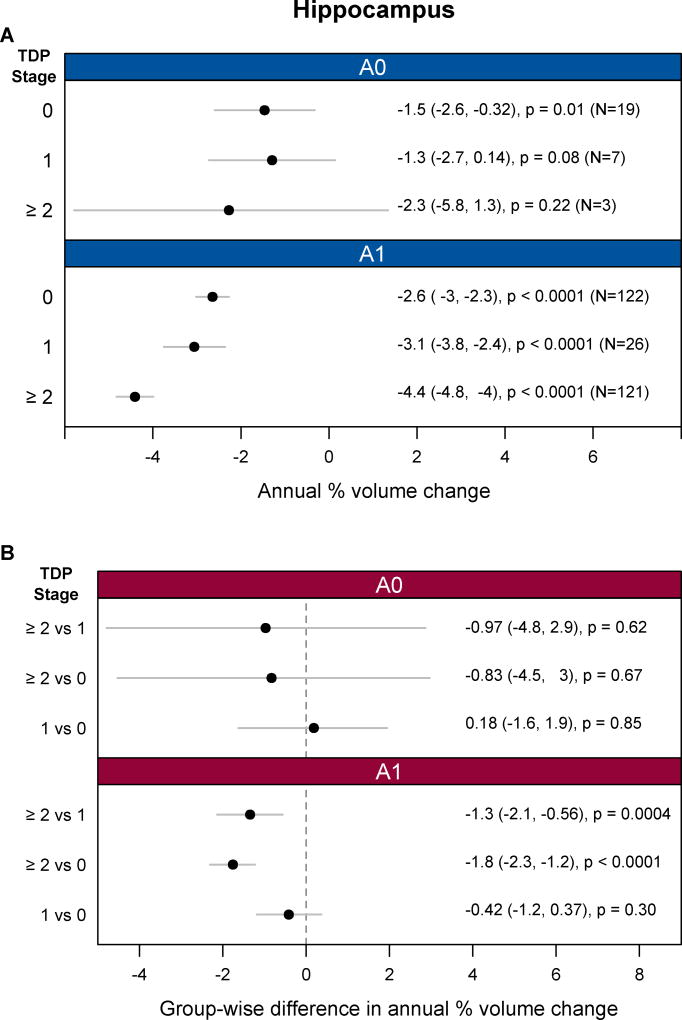

Across all three neurofibrillary tangle stages (B1–B3) significant hippocampal atrophy was observed in each TDP-43 stage (0, 1, and ≥2) (Figure 1). For neurofibrillary tangle stages B2 and B3, cases with TDP-43 in the hippocampus (TDP-43 stage≥2) showed significantly faster rates of hippocampal atrophy than cases with TDP-43 in the amygdala only (TDP-43 Stage 1), and cases without any TDP-43 (TDP-43 stage 0) (Figure 1). There were no differences in the rates of hippocampal atrophy between cases classified as TDP-43 stage 1 and those classified as TDP-43 stage 0. For neurofibrillary tangle stage B1, we did not observe any significant differences in the rates of hippocampal atrophy between TDP-43 stages. Furthermore, there was no significant dose-response trend for increasing TDP-43 stage and greater atrophy in B1 (estimate -0.5%/y (95% CI:-1.6%/y, 0.6%/y, p=0.39). TDP-43 stage≥2 also showed faster hippocampal rates than TDP-43 stage 0 and 1 in cases with amyloid (A1) (Figure 2). The associations between hippocampal atrophy and TDP-43 stage were very similar when using TBM-SyN and stratifying on either neurofibrillary tangle stage or amyloid (Appendix, p4). We also observed an association between TDP-43 stage≥2 versus stage 0 and faster rates of amygdala atrophy in cases with higher neurofibrillary tangle stages (B2 and B3) or with amyloid (A1) (Appendix, p5). No associations were observed with whole brain rates (Appendix, p6).

Figure 1.

Analyses of FreeSurfer hippocampal atrophy rates by TDP-43 and neurofibrillary tangle stages based on linear mixed effects regression modeling. (A) Shows hippocampal atrophy rates, expressed as an annual percent volume change, by TDP-43 stage separately for neurofibrillary tangles stages B1, B2, and B3. (B) Compares the rates of hippocampal atrophy, expressed as differences in annual percent volume change, between TDP-43 stages for each of the three neurofibrillary tangle stages. Annual percent volume changes and group-wise difference values are provided in Appendix, p8.

Figure 2.

Analyses of FreeSurfer hippocampal atrophy rates by TDP-43 and amyloid stage (amyloid- (A0), and amyloid + (A1)) based on linear mixed effects regression modeling. (A) Shows hippocampal atrophy rates, expressed as an annual percent volume change, by TDP-43 stage separately for two amyloid stages. (B) Compares the rates of hippocampal atrophy, expressed as differences in annual percent volume change, between TDP-43 stages for each of the two amyloid stages. Annual percent volume changes and group-wise difference values are provided in Appendix, p8.

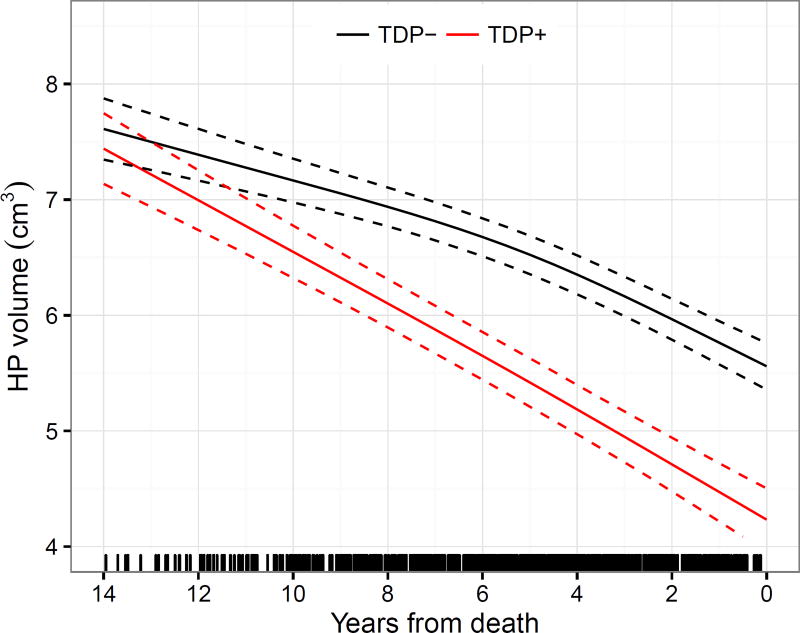

In our trajectory analysis we found that subjects with TDP-43 in the hippocampus showed a faster rate of hippocampal atrophy compared to those without TDP-43 in the hippocampus. The trajectories were observed to diverge at least 10 years prior to death (Figure 3, Appendix, p7).

Figure 3.

Trajectories of FreeSurfer hippocampal volumes for cases with and without hippocampal TDP-43 based on linear mixed effects regression modeling. The estimates assumed age at death of 80 years, MRI scan field strength of 1.5T, and a total intracranial volume of 1.4L. Note that cases with TDP-43 in the hippocampus (TDP+) had faster rates of hippocampal atrophy compared to cases without TDP-43 in the hippocampus (TDP−). The separation of the confidence intervals of the trajectories appears roughly a decade prior to death. Tick marks on the x-axis indicate available MRI data points in terms of years from death. Overall, on an annual basis and assuming death at age 80 years, mean decline was an estimated 0.19 cm3/year (95% CI, 0.17 to 0.20).

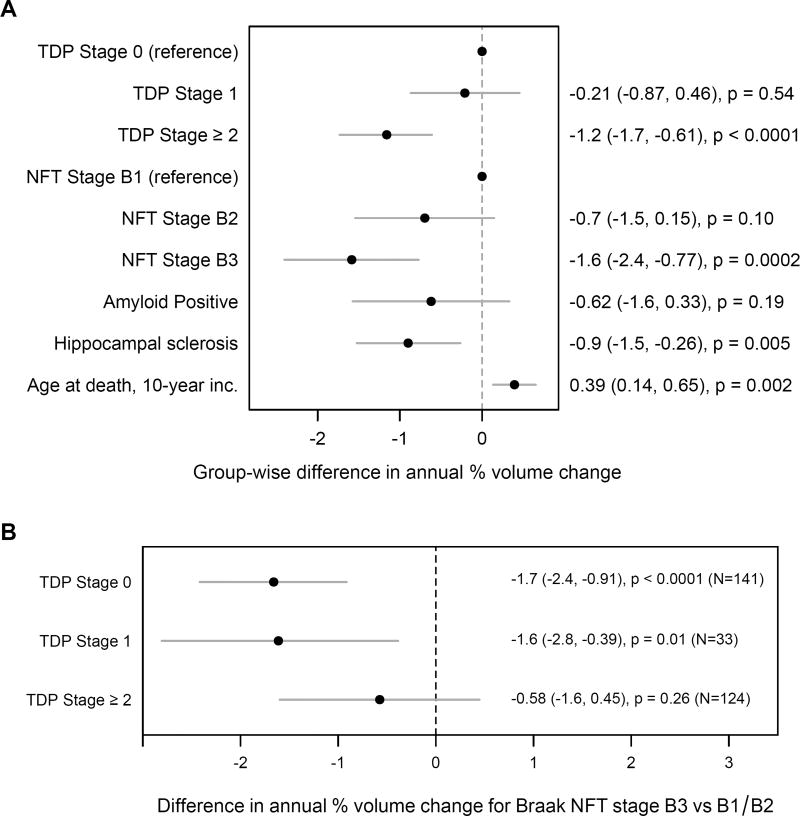

When we fit a model that included TDP-43 stage, neurofibrillary tangle stage, presence of amyloid, and presence of hippocampal sclerosis, faster rates of hippocampal atrophy were associated with higher TDP-43 and neurofibrillary tangle stages, as well as hippocampal sclerosis (Figure 4A). The evidence for an amyloid association was more equivocal. When APOE was added to the model e4 carriers declined an estimated 1.1 percentage points faster (95% CI, −3.6 to +1.4), a difference that was not significant (p=0.40). When we looked in greater detail at the relationship between neurofibrillary tangle stage and rate of hippocampal atrophy, we found significant associations between higher neurofibrillary tangle stages and faster rates of hippocampal atrophy in TDP-43 stages 0 and 1. There was no significant association at TDP-43 stage≥2 (p=0.26) (Figure 4B) (p=0.48 when run with TBM-SyN).

Figure 4.

Models assessing the role of additional pathologies. (A) Analysis of the independent effect of each of multiple pathologies on hippocampal atrophy rates based on linear mixed effects regression modeling assuming no interactions among the effects. Estimates are from a mixed model with TDP-43, neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) stage, amyloid positivity, hippocampal sclerosis, and age at death. For reference, the estimated rate of decline for an individual who died at age 80 with TDP Stage 0, NFT Stage B1, no amyloid, and no hippocampal sclerosis is 0.7% per year (95% CI, −1.7 to +0.25). (B) FreeSurfer hippocampal atrophy rates in each TDP-43 stage contrasting those with neurofibrillary tangle stage B3 versus those with neurofibrillary tangle stage of B1 or B2. The atrophy rates are statistically significant in TDP-43 stages 0 and 1. Group-wise difference values are provided in Appendix, p8.

INTERPRETATION

In this study we identify a strong association between the presence of TDP-43 in the hippocampus and faster rates of hippocampal atrophy. The association was identified in subjects with a higher likelihood of Alzheimer’s disease (i.e., neurofibrillary tangle stages B2 and B3) but not in those with a low likelihood of Alzheimer’s disease (neurofibrillary tangle stage B1).

Two previous studies4,5 found no associations between rates of hippocampal atrophy and the presence of the two cardinal pathological lesions of Alzheimer’s disease, senile plaques and the neurofibrillary tangles, as indirect markers of beta-amyloid and tau, respectively. The results of this study show a strong association between TDP-43 in the hippocampus and rates of hippocampal atrophy. Given that we have previously shown that TDP-43 first appears in the amygdala before spreading to the hippocampus, and the fact that we did not find any association between TDP-43 in the amygdala and faster rates of hippocampal atrophy, it appears that the observed association is specific to TDP-43 spreading into the hippocampus. The lack of an association between TDP-43 in the amygdala and rates of hippocampal atrophy is another piece of evidence that TDP-43 in the amygdala may be relatively silent10,22. In fact, we also did not observe an association between TDP-43 in the amygdala and amygdala rates of atrophy. Instead, an association was observed between hippocampal TDP-43 and amygdala rates of atrophy, showing that TDP-43 stage≥2 is not just related to hippocampal rates. However, the association does appear specific to the medial temporal lobe given that hippocampal TDP-43 was not associated with rates of whole brain atrophy.

Another important finding was the fact that the association between TDP-43 in the hippocampus and faster rates of hippocampal atrophy was limited to cases with neurofibrillary tangle stages B2 and B3, which is equivalent to Braak stages III-VI12 and hence an intermediate-high likelihood of Alzheimer’s disease23. In stages B2 and B3 moderate-severe amounts of neurofibrillary tangles can be identified in limbic regions and isocortex. We did not find strong evidence for an association between TDP-43 and faster rates of hippocampal atrophy in cases with neurofibrillary tangle stage B1 which represent Braak stages I–II12, and hence a low likelihood of Alzheimer’s disease23. In neurofibrillary tangle stage B1, absent-scant amounts of neurofibrillary tangles can be identified in transentorhinal cortex and the pre alpha cells of entorhinal cortex. To the extent TDP-43 is not associated with hippocampal atrophy rates in B1, there are at least three explanations for this finding. First, cases classified as B1 have a high likelihood of meeting criteria for primary age related tauopathy (PART)24 which is believed to be distinct from Alzheimer’s disease25, although this issue remains controversial26. Hence, if Alzheimer’s disease is indeed distinct from PART, the association between hippocampal TDP-43 and faster rates of hippocampal atrophy may be specific to Alzheimer’s disease. A second possibility is that the association between hippocampal TDP-43 and hippocampal rates depends on tau spreading into limbic and isocortex regions which could also be interpreted as TDP-43 having a later effect than tau on hippocampal rates. Given that we did find hippocampal atrophy rates to be greater than 0 even for cases with minimal pathology in the brain (TDP-43 stage 0 and neurofibrillary tangle stage B1) it is certainly possible that in such cases without TDP-43, possibly representing an early degenerative process, that tau is the driver of hippocampal atrophy and presumed neuronal loss. A third possibility is that a certain amount of tau deposition is required for TDP-43 to have an influence on hippocampal atrophy, possibly via an aggravation on the amount of local hippocampal tau pathology. Hence, tau alone may influence hippocampal atrophy while TDP-43 depends on tau. However, if both TDP-43 pathology and considerable tau pathology (B2/3) is present, TDP-43 then has an effect on hippocampal atrophy which is significantly stronger and somewhat masks the effect of higher tau pathology as reflected by neurofibrillary tangle stages. However, it is unclear whether higher neurofibrillary tangle stages, which measure distribution, are equivalent to having more hippocampal tau.

The primary aim of this study was to determine whether TDP-43 deposition in the hippocampus is associated with faster rates of hippocampal atrophy. However, Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by multiple different proteins, i.e. tau and amyloid, as well as being commonly associated with other pathologies, such as hippocampal sclerosis, the latter itself closely linked with TDP-4327. When we accounted for all these different pathologies, TDP-43 remained strongly associated with rates of hippocampal atrophy. Our analysis also showed that neurofibrillary tangle stage was independently associated with faster rates of hippocampal atrophy. Hence, it appears that both tau and TDP-43 maybe influencing rates of hippocampal atrophy. With that said, we do not know the directionality of these associations, and hence we cannot exclude the possibility that tau and/or TDP-43 deposition are secondary to neurodegeneration. Not surprisingly, hippocampal sclerosis was also associated with faster rates of hippocampal atrophy, but, importantly, was not driving our TDP-43 associations. One intriguing mechanistic possibility is that genetic factors may be at play. Specifically, polymorphisms in the progranulin gene, such as rs5848 that has been shown to be associated with hippocampal sclerosis and possibly TDP-43 in Alzheimer’s disease28, could be related to rate of hippocampal atrophy.

In addition, there was some suggestion that the neurofibrillary tangle association with rates of hippocampal atrophy may vary according to TDP-43. Our data indicates increasing neurofibrillary tangle stage was associated with faster rates of hippocampal atrophy among those with TDP-43 stages 0 and 1, but not at TDP-43 stage≥2. This may be further evidence that tau is playing a stronger role in determining hippocampal atrophy earlier in the disease course. Hence, biologically, tau deposition may occur early resulting in reduced hippocampal volume with little subsequent change over time, whereas TDP-43 deposition occurs later and spreads to the hippocampus in the decade before death producing further shrinkage. However, these results could also suggest that tau has a stronger relationship with hippocampal rates in young onset and atypical Alzheimer’s disease cases which tend to not have TDP-43 deposition8,29. Conversely, the results may support a stronger association between rates of hippocampal atrophy and TDP-43, than tau, in typical late-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

Our trajectory analysis showed that TDP-43 was associated with faster rates of hippocampal atrophy at least a decade before death. However, a divergence in the two groups does not exclude other reasons that may account for the differences. Regardless, our findings could have important implications for targeted treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Treatment trials for Alzheimer’s disease sometimes utilize rate of hippocampal atrophy as an outcome measure, yet many of these trials assess therapies targeting beta-amyloid, and less commonly tau. Our results suggest that it would be important for these trials to take into account the fact that there is a strong association with TDP-43 that could confound results.

Two limitations of our study are the fact that the number of subjects within specific groups defined by TDP-43 and neurofibrillary tangle stage were relatively small and we were unable to assess cases with no neurofibrillary tangles (B0 cases) to provide a pure healthy control group. Furthermore, our cohort was relatively old and therefore our findings may not generalize to young-onset or genetic variants of Alzheimer’s disease.

Treating Alzheimer’s disease is likely to be a complex process and although the findings from this study add further complexity, the results supports the notion that TDP-43 should also be considered a therapeutic target, especially since TDP-43 is found in other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Lewy body disease30. Our data also argues for the importance of developing techniques for detecting TDP-43 pathology in-vivo in order to understand the pathological profile of individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. In fact, given that TDP-43 first deposits in the amygdala before spreading to the hippocampus we ponder whether detecting amygdala TDP-43 prior to it spreading into the hippocampus could be an achievable potential point of targeted treatment. Clearly, however, given the observed association with TDP-43 and faster rates of hippocampal trophy occurring at least a decade prior to death, any treatment implementation of TDP-43 would likely need to occur early in the disease course if it is to be successful.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the US National Institute of Heath (NIA) grants R01 AG037491, P50 AG16574, U01 AG006786, R01 AG11378 and R01 AG041851. We wish to thank the families of the patients who donated their brains to science allowing completion of this study.

KAJ, DWD, LP, JEP, MEM and JLW receive research support from the NIH. LP has a U.S. patent #9,448,232 entitled “Methods and materials for detecting C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion positive frontotemporal lobar degeneration or C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion positive amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.” DSK served as Deputy Editor for Neurology®; served on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lilly Pharmaceuticals; serves on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals and for the DIAN study; served as a consultant to TauRx Pharmaceuticals ending in November 2012; was an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Baxter and Elan Pharmaceuticals in the past 2 years; is currently an investigator in a clinical trial sponsored by TauRx; and receives research support from the NIH. RCP serves as a consultant for Roche, Inc., Merck, Inc., Genentech, Inc., Biogen, Inc., Eli Lilly and Company and receives research support from the NIH. CRJ serves as a consultant for Janssen, Bristol-Meyer-Squibb, General Electric, and Johnson & Johnson; is involved in clinical trials sponsored by Allon and Baxter, Inc.; and receives research support from Pfizer, Inc., the NIH, and the Alexander Family Alzheimer's Disease Research Professorship of the Mayo Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

KAJ was responsible for study concept and design, data interpretation and drafting the original report which was reviewed and revised by all co-authors. KAJ, MEM, AS and DWD were responsible for acquisition of TDP-43 data and pathological classification. JLW, MLS and AJS were responsible for all neuroimaging analyses. SDW and NT were responsible for statistical analysis and for creating Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4. LP was responsible for providing the TDP-43 antibodies utilized in this study. CRJ was responsible for acquisition of MRI. RCP and DSK were responsible for acquisition of clinical data. Pathological examinations were performed by DWD and JEP. Funding was obtained by KAJ, RCP and CRJ.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

SDW, NT, AJS, MLS and AML do not have any declarations of interest.

References

- 1.Zarow C, Vinters HV, Ellis WG, et al. Correlates of hippocampal neuron number in Alzheimer's disease and ischemic vascular dementia. Ann Neurol. 2005;57(6):896–903. doi: 10.1002/ana.20503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jack CR, Jr, Dickson DW, Parisi JE, et al. Antemortem MRI findings correlate with hippocampal neuropathology in typical aging and dementia. Neurology. 2002;58(5):750–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.5.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jack CR, Jr, Petersen RC, Xu Y, et al. Rate of medial temporal lobe atrophy in typical aging and Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1998;51(4):993–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.4.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erten-Lyons D, Dodge HH, Woltjer R, et al. Neuropathologic basis of age-associated brain atrophy. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(5):616–22. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silbert LC, Quinn JF, Moore MM, et al. Changes in premorbid brain volume predict Alzheimer's disease pathology. Neurology. 2003;61(4):487–92. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000079053.77227.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314(5796):130–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amador-Ortiz C, Lin WL, Ahmed Z, et al. TDP-43 immunoreactivity in hippocampal sclerosis and Alzheimer's disease. Annals of neurology. 2007;61(5):435–45. doi: 10.1002/ana.21154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Tosakulwong N, et al. TAR DNA-binding protein 43 and pathological subtype of Alzheimer's disease impact clinical features. Annals of neurology. 2015;78(5):697–709. doi: 10.1002/ana.24493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Weigand SD, et al. TDP-43 is a key player in the clinical features associated with Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127(6):811–24. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1269-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Josephs KA, Murray ME, Whitwell JL, et al. Staging TDP-43 pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127(3):441–50. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1211-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Josephs KA, Murray ME, Whitwell JL, et al. Updated TDP-43 in Alzheimer's disease staging scheme. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(4):571–85. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1537-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1991;41(4):479–86. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82(4):239–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rauramaa T, Pikkarainen M, Englund E, et al. Consensus recommendations on pathologic changes in the hippocampus: a postmortem multicenter inter-rater study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013;72(6):452–61. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e318292492a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sled JG, Zijdenbos AP, Evans AC. A nonparametric method for automatic correction of intensity nonuniformity in MRI data. IEEE transactions on medical imaging. 1998;17(1):87–97. doi: 10.1109/42.668698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33(3):341–55. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Avants BB, Epstein CL, Grossman M, Gee JC. Symmetric diffeomorphic image registration with cross-correlation: evaluating automated labeling of elderly and neurodegenerative brain. Medical image analysis. 2008;12(1):26–41. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jack CR, Jr, Wiste HJ, Knopman DS, et al. Rates of beta-amyloid accumulation are independent of hippocampal neurodegeneration. Neurology. 2014;82(18):1605–12. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied Longitudinal Analysis. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gelman A, Hill J. Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.James BD, Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Trojanowski JQ, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. TDP-43 stage, mixed pathologies, and clinical Alzheimer's-type dementia. Brain. 2016 doi: 10.1093/brain/aww224. pii: aww224. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WorkingGroup. Consensus recommendation for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. The National Institute on Aging, and Reagan Institute Working Group on Diagnostic Criteria for Neuropathologic Assessment of Alzheimer's Disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18(Supp1):S1–S2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crary JF, Trojanowski JQ, Schneider JA, et al. Primary age-related tauopathy (PART): a common pathology associated with human aging. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128(6):755–66. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1349-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jellinger KA, Alafuzoff I, Attems J, et al. PART, a distinct tauopathy, different from classical sporadic Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129(5):757–62. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1407-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duyckaerts C, Braak H, Brion JP, et al. PART is part of Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129(5):749–56. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1390-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nag S, Yu L, Capuano AW, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis and TDP-43 pathology in aging and Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2015;77(6):942–52. doi: 10.1002/ana.24388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dickson DW, Baker M, Rademakers R. Common variant in GRN is a genetic risk factor for hippocampal sclerosis in the elderly. Neurodegener Dis. 2010;7(1–3):170–4. doi: 10.1159/000289231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bigio EH, Mishra M, Hatanpaa KJ, et al. TDP-43 pathology in primary progressive aphasia and frontotemporal dementia with pathologic Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120(1):43–54. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0681-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McAleese KE, Walker L, Erskine D, Thomas AJ, McKeith IG, Attems J. TDP-43 pathology in Alzheimer's disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and ageing. Brain Pathol. 2016 doi: 10.1111/bpa.12424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.