Abstract

Bisexual youth are at elevated risk for depression compared to lesbians and gay men. Research on bisexual stigma suggests these youth are uniquely vulnerable to stress related to sexual identity disclosure. Depression associated with this stress may be buffered by social support from parents and friends. We examined the differential influence of social support from parents and friends (Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale) on the relation between disclosure stress (LGBTQ Coming Out Stress Scale) and depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory) and differences by gender in a sample of cisgender bisexual youth (n = 383) using structural equation modeling. Parental support buffered the association between stressful disclosure to family and depressive symptoms, especially for bisexual men; bisexual women seemed not to benefit from such support when disclosure stress was high. This nuanced examination elucidates the ways family members and clinicians can best support bisexual youth sexual identity disclosure.

Keywords: Gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, social support, stress, coping, and/or resiliency, depression, youth/emergent adulthood

Depression is a serious problem for lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) youth; researchers have extensively documented that LGB youth report higher rates of depression compared to their heterosexual counterparts (Institute of Medicine, 2011). Research findings also indicate that bisexual people specifically report higher levels of depression and suicidal ideation and behavior than their lesbian and gay peers (Marshal et al., 2011; Pompili et al., 2014). Such evidence suggests that bisexual people are vulnerable to stress in distinct ways, even within the LGB community. One mechanism that may help explain higher levels of depression among LGB people, and particularly among bisexual people, is disclosure; i.e., the act of revealing one’s sexual or gender identity.

Disclosing is often difficult, and the related stress has been linked to depression (e.g., Russell, Ryan, Toomey, & Diaz, 2014). Although less is known about sexual identity disclosure among youth than adults, the stress of disclosing likely differs depending on whether someone discloses to family or friends. At the same time, social support from family and friends may alleviate stress related to disclosure. Additionally, bisexual people experience unique stigma beyond that experienced by lesbian and gay people, including invisibility in relationships and rejection by both heterosexual and gay/lesbian people (Israel & Mohr, 2004), which may result in distinct disclosure experiences among bisexual youth (Scherrer, Kazyak, & Schmitz, 2015). However, few researchers have studied these associations among bisexual people, a group for whom depression is especially high (Pompili et al., 2014).

The minority stress model (Meyer, 2003) has been used extensively to examine the relation between stress and mental health for LGB people. In particular, the minority stress model focuses on stigma-related mechanisms of stress that are unique to sexual minorities, including expectations of rejection or discrimination, prejudice events, concealment of sexual identity, and internalized homophobia (see Meyer, 2003 for a full description of the minority stress model). Disclosure stress is stress experienced by sexual minority people due to expectations of rejection after disclosure of sexual identity. The model posits that the influence of such stressors on mental health depends in part on the sources and quality of social support. In this study, we focus on how the presence of social support may serve to buffer the association between disclosure stress and depressive symptoms. One limitation of research using the minority stress model up to this point is that it “fails to distinguish bisexual individuals from lesbian and gay individuals” (Meyer, 2013, p. 19). However, this limitation is more a reflection of historically small samples that required combining bisexual with lesbian and gay participants for analytic purposes rather than a shortcoming in the model itself.

To address this limitation in the literature, and in an effort to capture more accurately the unique disclosure experiences of bisexual people, in this study we investigate the relation between disclosure stress and depressive symptoms as moderated by social support and gender among bisexual youth. Differences between cisgender (those whose gender identity matches their sex and gender assigned at birth) bisexual young men and women are also explored. Because this study focuses on bisexual youth and there is limited research on the disclosure experiences of transgender youth, we predominantly review literature about the disclosure process with combined samples of cisgender lesbian, gay, and bisexual people. Thus, though the acronym LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) is often used in reference to research on sexual and gender minorities, we use the term LGB (lesbian, gay, and bisexual) to reflect our focus on sexual minorities. Moreover, all references to and discussion of gender are informed by literature on cisgender people unless otherwise noted.

Disclosure Stress

Disclosing one’s same-sex or multiple-sex sexual identity to others is an experience common to sexual and gender minority people that is often highly stressful for many LGB people, especially youth. Within the minority stress model (Meyer, 2003), disclosure stress is related to expectations of rejection: Disclosure of one’s sexual identity is an act often marked by fear, particularly of the reactions of others and the potential loss of social, emotional, and financial support (D’Augelli, Hershberger, & Pilkington, 1998; Mufioz-Plaza, Quinn, & Rounds, 2002).

Research on reactions to and outcomes of LGB youths’ sexual identity disclosure are mixed. While some research suggests youth are met with tolerance or acceptance (D’Augelli et al., 1998; Savin-Williams & Ream, 2003), other research suggests otherwise (D’Augelli & Grossman, 2001; D’Augelli et al., 1998). Positive outcomes include higher positive affect and self-esteem and less anxiety in lesbian women (Jordan & Deluty, 2000) and less anger and depression and higher self-esteem in LGB adults who have disclosed (Legate, Ryan, & Weinstein, 2011) than those who had not disclosed. Lastly, despite negative reactions to disclosure, being out as an adolescent appears to be associated with positive adjustment years later (Russell et al, 2014). Thus, even though youth who were out at school were more likely to report being victimized, being out was associated with lower depression, higher self-esteem, and greater life satisfaction in adulthood compared to youth who did not come out.

Although researchers and community members conceptualize disclosure as a positive step towards well-being and identity integration (e.g., Cass, 1979), they have focused on negative outcomes following disclosure, which may be a period of heightened risk. Youth who disclosed their sexual identity at younger ages reported more victimization and abuse than youth who disclosed at older ages (D’Augelli & Grossman, 2001). After disclosure, LGB youth reported verbal and physical violence (D’Augelli et al., 1998), increased alcohol use (Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2004) and, among gay and bisexual men, anxiety (Rosario, Hunter, Maguen, Gwadz, & Smith, 2001; Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2006). Though disclosure is associated with stress-related growth and positive outcomes over time (Jordan & Deluty, 2000; Legate et al, 2011; Russell et al., 2014), it is a unique LGB stressor associated with a heightened risk for negative outcomes, especially immediately following disclosure.

Compared to lesbians and gay men, bisexual people face additional complexities when navigating disclosure. Bisexual people face multiple forms of discrimination (Grollman, 2012) because they occupy a space at the intersection of two systems of oppression: both heterosexism that gay and lesbian people face and monosexism, or the structural privileging of attraction to only one gender (Eisner, 2013). Monosexism results in the invisibility of bisexuality because people are assumed to only fall into two identity categories, based on the gender of their partners: heterosexual or lesbian/gay. Thus, bisexual people may not disclose to family members when they are in mixed-gender relationships because they are presumed to be heterosexual (McLean, 2007; Scherrer et al., 2015). At the same time, some bisexual people disclose as gay or lesbian because they believe their family members will understand those identities more readily than a bisexual identity (Scherrer et al., 2015). Even when family members are accepting of bisexuality, they still believe their bisexual loved ones should “pick a side” (McClelland, Rubin, & Bauermeister, 2016, p. 8). The effects of monosexism are evident in research that shows lesbian and gay youth report greater acceptance and support from parents and friends than bisexual youth (Watson, Grossman, & Russell, 2016; Shilo & Savaya, 2011).

In addition to the navigation of disclosure to family members, bisexual people may expect rejection in the form of hostility or resistance (due to persistent myths about bisexuality that stem from monosexism) when they disclose their bisexual identity. Many bisexual people hesitate to come out to others in the lesbian and gay community for fear of losing support of peers because of bisexual stereotypes (Bostwick & Hequembourg, 2014; Hequembourg & Brallier, 2009; McLean, 2007; Ross, Dobinson, & Eady, 2010). This fear is similar to LG youths’ fears that disclosing will lead to the loss of social and emotional support from heterosexual peers (D’Augelli et al., 1998; Mufioz-Plaza et al., 2002). For example, adult bisexual women report that their bisexual identities are met with hostility, denial, confusion, pressure to change, and feeling “not being ‘gay enough’” (Bostwick & Hequembourg, 2014, p. 9). In one study, bisexual people reported being asked to explain their identities and answer invasive questions about their sexual history (McLean, 2007). These reactions to disclosure are rooted in stereotypes that bisexuality is a transitional identity; i.e., that bisexual people are in transition to identifying as either gay or straight (Israel & Mohr, 2004). The expectation to validate or prove one’s sexual identity is a unique aspect of disclosing for bisexual people compared to their lesbian and gay peers. In a study of minority stress, one bisexual woman stated, “It makes you not wanna come out and try and be honest with people, and try to make new friends, and possibly meet somebody you can be with—because you’re too afraid” (Hequembourg & Brallier, 2009, p. 291).

As a consequence of this unique stigma, bisexual people are less likely to be out (Shilo & Savaya, 2012; Weinberg, Williams, & Pryor, 1994) and come out at later (Rust, 1993) than lesbians and gay men. In addition, though bisexual people report less difficulty when disclosing, they report less acceptance than gay men and lesbians (Cox, Dewaele, van Houtte, & Vincke, 2001; Shilo & Savaya, 2011). Ultimately, these distinct experiences influence the mental health of bisexual people through greater stress (Ross, Dobinson, & Eady, 2010). In the current study, we extend the literature on bisexual disclosure by examining the experiences of disclosure stress, a minority stressor associated with mental health, among bisexual youth. In particular, we examine whether disclosure to family and friends differentially influences mental health and whether these associations are buffered by perceived social support.

The Protective Role of Support

The minority stress model suggests that the causal effect of minority stress, such as disclosure stress, on health can be moderated by coping and social supports, such as support from community, friends, and family (Meyer, 2013). Despite the complexities of the disclosure experience, studies repeatedly identify social support as an important element in countering the possible negative effects of minority stressors (Hershberger & D’Augelli, 1995; Meyer, 2013; Sheets & Mohr, 2009; Shilo & Savaya, 2011; Shilo & Savaya, 2012). Family support and acceptance of LGB youth have been shown to buffer the association between victimization and psychological stress (Hershberger & D’Augelli, 1995). Greater support from family and friends has been shown to be associated with higher well-being and lower mental distress among LGB youth (Shilo & Savaya, 2011; Shilo & Savaya, 2012). Research finds bisexual people report less support from LGBTQ communities (e.g., Hequembourg & Brallier, 2009; Ross et al., 2010). For example, in an online sample of bisexual college students, general social support predicted lower depression and higher life satisfaction whereas LGB-specific support did not predict lower internalized binegativity (Sheets & Mohr, 2009). Support from family and loved ones may substitute the social support bisexual youth might not receive from the LGBTQ community.

Though overall support from loved ones has been shown to be associated with positive adjustment in LGB youth, friend and family support each have been found to independently predict lower depression and higher life satisfaction and self-esteem among LGB youth (Watson et al., 2016; Sheets & Mohr, 2009). There is inconsistency in the literature on whether support from family or friends is more influential individually or combined on well-being. Friends are often more supportive than parents and LGB youth rely heavily on their close friends for emotional support, especially their LGB-identified friends (Mufioz-Plaza et al., 2002). LGB youth often seek support from non-family members such as LGB friends after family rejection; however, youth were likely to seek this support even if their family was supportive, especially when seeking sexual minority specific information (Nesmith, Burton, & Cosgrove, 1999).

Conversely, other studies have shown that family support in family-centered cultures, e.g. Israel, has a greater impact on well-being and mental distress among LGB youth than does friend support (Shilo & Savaya, 2011; Shilo & Savaya, 2012). Bisexual youth report less family support than their lesbian and gay peers (Shilo & Savaya, 2012); however, there may be important gender differences in family and friend support among bisexual youth. For example, parent support has been found to be associated with less depression for bisexual men while close friend support buffered against depressive symptoms among bisexual women (Watson et al., 2016). Thus, in the current study, we expand on these findings to examine how parent and close friend support differentially buffer the association between disclosure stress and depressive symptoms among bisexual women and men.

Gender Differences between Bisexual Women and Men

Much of the research on bisexual disclosure has focused on the experiences of bisexual women, perhaps because studies include more women who identify as bisexual than men, especially in nonrandom samples (Diamond, 2013). However, what is known about bisexual men broadly indicates potential differences in disclosure between bisexual women and men. Bisexual men are more likely to be gender conforming than gay men (Li, Pollitt, Russell, 2015). Bisexual men could be more likely to be friends with heterosexual men than with gay men because of this gender conformity, in addition to the difficulty that bisexual people have finding acceptance in gay communities due to bisexual stereotypes and invisibility (Callis, 2013; Hequembourg & Brallier, 2009). Disclosing to straight friends can have serious consequences for bisexual men, as one man stated, “My male friends, if I admitted anything to them, they would probably try to attack and kill me…I would think guys, in general, would be opposed to it” (Hequembourg & Brallier, 2009, p. 292). These men have “more to lose” (e.g., privilege, safety) by disclosing their bisexuality. Thus, bisexual identity disclosure could be particularly stressful for bisexual men because they would rather conceal their sexual identity to avoid disclosure and stress related to disclosure.

It is a common belief that identifying as bisexual is easier for woman than it is for men because sexual fluidity in women is sanctioned; that is, bisexuality in women is considered acceptable because women are objectified and hypersexualized as potential partners for group sex and considered sexual attention seekers (Callis, 2013; Diamond 2005). Though descriptively different, the underlying stereotype remains the same for bisexual men and women: “Bisexual women are considered trendy (and thus, not real), whereas bisexual men are considered gay (and thus, not real)” (Callis, 2013, p. 84). These studies suggest that disclosure experiences for bisexual men and women could be uniquely different.

The Current Study

Numerous studies have established that LGB youth and young adults are at higher risk for depression, among other negative health outcomes (e.g., Marshal et al., 2011; Pompili et al., 2014). Similar research has established the vital role social support plays in buffering the negative effects of disclosure stress for LGB people, including bisexual young people (e.g., Sheets & Mohr, 2009). However, much of this literature is limited because it has historically and predominately focused on experiences of lesbian and gay people to draw conclusions about experiences of all same-sex attracted people. Recent literature suggests the disclosure experiences of bisexual people are uniquely different from that of their lesbian and gay peers, which necessitates additional examination of the experiences of bisexual people (Hequembourg & Brailler, 2009; Scherrer et al., 2015). Differences between bisexual women and men suggest there could be a moderating effect of gender on their disclosure stress and depressive symptoms (Callis, 2013; Diamond, 2005). In the present study, we examined the relation between disclosure stress and depressive symptoms of bisexual youth as well as the moderating roles of family support, friend support, and gender.

Method

Participants

Data come from the first of four panels in a longitudinal panel study of the risk and protective factors of suicide among 1061 sexual minority youth in three urban cities (one each in the Northeast, Southwest, and on the West Coast) of the United States collected in 2012. The majority of the youth were recruited from community-based agencies or college groups for LGBTQ youth, and other participants were referred by earlier participants. While the sample was diverse in terms of sexual orientation and gender identity, the majority of participants identified as cisgender (n = 932), which was defined for the current study as youth whose reported gender identity was either woman or man and corresponded with their sex assigned at birth, explained in more detail below. We limited our analysis to cisgender bisexual youth due to the small sample size of transgender and gender nonconforming bisexual youth (n = 37) in the sample. One female cisgender participant was missing on all indicators but had data for controls; this case was dropped from analyses for a total sample size of 383. The final sample, then, is comprised of cisgender bisexual men (n = 128) and women (n = 255) ages 15–21 (M = 18.3 and 17.6, respectively).

Using current federal reporting guidelines, 39.2% were of Hispanic or Latino background. Regarding race, 22.5% were White/Caucasian, 23.2% Black or African American, 4.7% Asian or Asian American, 3.1% American Indian or Alaskan Native, 1.0% Native Hawaii or Other Pacific Islander, 24.8% more than one race, and 20.6% did not report their race. All but four participants reported being out to at least one person; two of these four participants reported disclosure stress. Results did not change when these four participants were excluded from analyses, thus they were retained.

Measures

We included cisgender bisexual women and men based on their responses to three items: birth sex, gender identity, and sexual identity. In response to the question, “What is your birth sex?” youth could indicate male, female, or intersex. Youth indicated their gender identity (“What is your gender identity?”) as either man, woman, queer, trans-man, trans-woman, or could write in their gender identity. Categories for “How would you describe your sexual identity?” included gay; lesbian; bisexual, but mostly gay or lesbian; bisexual, equally gay/lesbian and heterosexual/straight; bisexual, but mostly heterosexual/straight; heterosexual/straight; or questioning/uncertain. We included youth who indicated that their birth sex corresponded to their gender identity (male/man, female/woman) and identified as bisexual.

Social support was measured as two latent constructs using the Parents (N items = 12, α = .95) and My Close Friend (N items = 12, α = .96) subscales of the Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale (Malecki, Demaray, Elliott, & Nolten, 1999). The Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale consists of 60 items that measure general perceived support on five subscales assessing how often from 1 (never) to 6 (always) it is that parents, teachers, classmates, a close friend, and people in the youths’ school support them. Example items of this measure include “My close friend takes time to help me solve my problems” and “My parents tell me I did a good job when I do something well.” We parceled both scales into three indicators each such that items with lower reliability were averaged with items of higher reliability (e.g., Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002).

We created two latent constructs of disclosure stress: stress of disclosure to family and stress of disclosure to friends. We used items from the LGBTQ Coming Out Stress Scale, a modified version of the Gay-Related Stress Scale (Rosario, Rotheram-Borus, & Reid, 1996). Stress of disclosure to family members contained five items probing different ways to disclose (α = .87), each of which assessed how stressful it was—from 1 (no stress) to 4 (extremely stressful)—when participants either told their (1) parents and (2) siblings that they were LGBTQ or when (3) parents, (4) siblings, and (5) other family members found out that they were LGBTQ. We parceled these items similarly to parent and close friend support (Little et al., 2002). Stress of disclosing to friends was measured in three items (α = .76): (1) when they told their friends, (2) when their friends found out, and (3) when a friendship ended due to the participant being LGBTQ, each treated as a single indicator.

Depressive symptoms was measured with the Beck Depression Inventory for Youth (Beck, 1996), a 20-item (α = .94) scale which asked participants how often in the past two weeks they felt: “I think that my life is bad” and “I feel no one loves me,” etc. Participants could respond 0 (never), 1 (sometimes), 2 (often), or 3 (always). Three parcels for depressive symptoms were created based on reliability (Little et al., 2002).

We included multiple control variables. Time since first disclosure was created by subtracting age of first disclosure, measured with the item, “How old were you when you first told someone that you were lesbian/gay/bisexual/queer?” from age at the time of the survey. Race was dummy coded into White, Black, Multiracial, and A/PI/NA racial groups with White as the referent group. The A/PI/NA group consisted of Asian, Pacific Islander, and Native American youth due to small sample size. Ethnicity was dummy coded 0 (not Hispanic or Latino) and 1 (Hispanic or Latino).

Analysis Plan

Our analysis proceeded in five stages: (1) confirmatory factor analysis of all latent constructs included in the final model (reported above); (2) measurement invariance of latent constructs between bisexual women and men; (3) full sample model of main effects (stress of disclosure to family, stress of disclosure to friends, parental support, and close friend support) predicting depressive symptoms; (4) full sample model with latent interactions; and (5) multiple group model with latent interactions. The stress of disclosing to family and friends were regressed on gender, years since first disclosure of sexual identity, and race/ethnicity. Depressive symptoms was regressed on gender, years since first disclosure, and race/ethnicity. Parental and close friend support were regressed on years since first disclosure and gender. We conducted all structural equation models in Mplus 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012) using maximum likelihood estimation for all models except the latent interaction models, in which we used maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR).

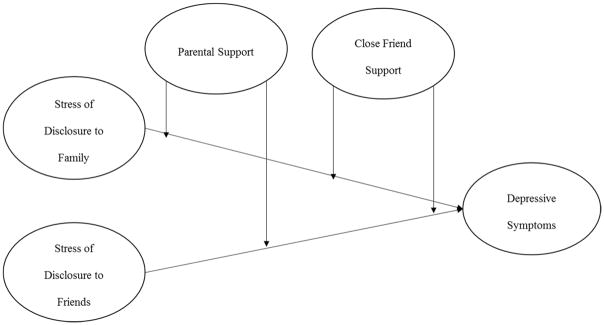

We show the hypothesized latent interaction model in Figure 1. We used the XWITH command in Mplus to conduct latent interaction models. We examined model fit using model chi-square. However, model chi-square values are sensitive to sample size and should thus be used in conjunction with other goodness-of-fit indices. For the current study, we examined model fit with the comparative fit indices Comparative Fit Index (CFI; values > .90 indicate good fit) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI; values > .90 indicate good fit) which compare each model to a model with an independence model with no covariances. We also examined model fit using the parsimony-corrected index Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; values < .05 indicate good fit) which includes a penalty for complex models. However, these fit indices are not available for latent interaction models; thus, we examined fit of these models with the likelihood ratio test (i.e., −2 times log likelihood). To obtain accurate log likelihood values, we treated continuous control variables as parameters in the model so that maximum likelihood would estimate the missing data, rather than use multiple imputation. This is because model log likelihoods do not follow a chi-square distribution when missing data are imputed and thus do not provide accurate values for comparison testing (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2010). This is important for the current analysis because maximum likelihood derived chi-square values do not correctly assess misfit of latent interactions (Mooijaart & Satorra, 2009).

Figure 1.

Hypothesized Latent Interaction Model of Parental Support and Close Friend Support Moderating Stress of Disclosure to Family and Stress of Disclosure to Friends Predicting Depressive Symptoms.

Results

Descriptive analyses including bivariate correlations, observed means, and standard deviations on scales by gender are in Table 1. Women and men did not differ on years since first disclosure of their sexual identity. Disclosure to family and friends was significantly more stressful for men than for women. Both men and women reported greater close friend support than parental support and greater stress of disclosure to family than stress of disclosure to friends. From the bivariate correlations, we found close friend support and parental support were significantly positively related. Stress of disclosure to friends was negatively related to close friend support and positively related to stress of disclosure to family. Depressive symptoms were negatively associated with both types of support and positively associated with both types of disclosure stress. Time since first disclosure was not correlated with any construct. We created and examined a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to establish validity and reliability of measures. While model fit was good (see Table 2 for model fit information), the third indicator of stress of disclosure to friends loaded on the construct poorly (λ = .08), likely because of high missingness. We dropped this item, despite no significant difference between the CFA model without this indicator (χ2 = 86.27, df = 67, p = .06) and the model with this indicator (χ2 = 98.95, df = 80, p = .07; Δ χ2 = 12.68, Δdf = 13, p = .47).

Table 1.

Pearson Correlations, Means and Standard Deviations by Gender, and t-test Comparisons by Gender of Key Variables

| Women (N = 255, 66.6%) | Men (N = 128, 33.4%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| 1. Parental Support | -- | 41.52 (16.6) | 43.44 (16.9) | |||||

| 2. Close Friend Support | .26** | -- | 58.41 (13.9) | 56.94 (12.7)** | ||||

| 3. Stress of Disclosure to Family | −.11 | −.09 | -- | 1.60 (1.3) | 2.05 (1.3)*** | |||

| 4. Stress of Disclosure to Friends | −.04 | −.21** | .42** | -- | 0.90 (1.2) | 1.51 (1.3) | ||

| 5. Depressive Symptoms | −.43** | −.24** | .17** | .27** | -- | 0.94 (0.7) | 0.85 (.58) | |

| 7. Years Since First Disclosure | −.09 | −.15** | .07 | .02 | −.06 | -- | 2.92 (2.3) | 3.02 (2.8) |

p < .05;

p < .01.

Table 2.

Model Fit Statistics

| Model tested | χ2 | df | p | Δχ2 | Δdf | p | RMSEA | RMSEA 90% CI | CFI | ΔCFI | TLI | ΔTLI | −2 Log Likelihood | Satorra-Bentler Scaling Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample null model | 4146.70 | 91 | <.001 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Full sample CFA | 86.27 | 67 | .06 | -- | -- | -- | .027 | .000; .043 | .995 | -- | .990 | -- | -- | -- |

| Multiple group configural model | 164.03 | 134 | .04 | -- | -- | -- | .034 | .008; .051 | .993 | -- | .990 | -- | -- | -- |

| Multiple group metric model | 176.95 | 143 | .03 | 12.92 | 9 | .17 | .035 | .012; .051 | .992 | .001 | .989 | .001 | -- | -- |

| Multiple group scalar model | 193.72 | 152 | .01 | 16.77 | 9 | .05 | .038 | .019; .053 | .990 | .002 | .988 | .001 | -- | -- |

| Full sample main effects model | 177.12 | 136 | .01 | -- | -- | -- | .028 | .014; .039 | .990 | -- | .987 | -- | -- | -- |

| Full sample interaction model | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | −6345.94 | 1.22 |

| Interactions constrained to zero | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | −6350.13 | 1.21 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Multiple group null model | 4434.58 | 322 | <.001 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Multiple group main effects model | 347.97 | 271 | .01 | -- | -- | -- | .039 | .025; .050 | .981 | -- | .978 | -- | -- | -- |

| Multiple group interaction model | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | −6561.55 | 1.16 |

| Interactions constrained to zero | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | −6567.21 | 1.16 |

Note. RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index. The multiple group models compared women to men.

To ensure accurate group comparisons in the multiple group models we used this well-fitting CFA to test for measurement invariance, which examines whether the factorial structure, factor loadings, and intercepts are equivalent between women and men. Configural invariance occurs when the underlying factorial structure of the measurement model is the same between groups and indicates that men and women understand the constructs in the same way. Factor loadings are constrained to be equal across groups for metric invariance and indicates that men and women responded to items in similar ways. Finally, scalar invariance allows us to compare latent mean scores across groups as it indicates that observed scores are related to latent scores (Milfont & Fischer, 2011). Factors were configurally, metric and scalar invariant. Though the chi-square difference test between the scalar and metric model was significant at p = .05, small differences between metric and scalar model CFI, TLI and RMSEA confirmed scalar measurement invariance (Little, 2013). Collectively, then, results indicated that we can compare latent means and regression coefficients across groups.

We then fit a main effects SEM model with stress of disclosure to family, stress of disclosure to friends, parental support and close friend support predicting depressive symptoms with controls and with the combined full sample. To scale the factors in this and subsequent models, we constrained the latent variances of the factors to 1 and freely estimated each of the indicators (Little, 2013). In this model, high parental support moderately predicted less depressive symptoms (see Table 3 for unstandardized regressions betas, standard errors, and R2 for all regression models). Further, high levels of stress of disclosure to friends moderately positively predicted depressive symptoms.

Table 3.

Model Unstandardized Regression Coefficients, Standard Errors, and R2

| Model 1: Main Effects Model | Model 2: Interaction Model | Model 3: Multiple Group Main Effects Model | Model 4: Multiple Group Interaction Model | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| DV: Depressive Symptoms | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE |

| Mana | −0.29* | 0.12 | −0.31** | 0.12 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Years Since First Disclosure | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.04 |

| Latinob | −0.06 | 0.09 | −0.06 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.12 | −0.02 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.14 | −0.02 | 0.13 |

| Black or African Americanc | −0.41** | 0.15 | −0.39* | 0.17 | −0.57** | 0.19 | −0.04 | 0.28 | −0.61** | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.28 |

| A/PI/NAc | −0.07 | 0.21 | −0.03 | 0.20 | −0.14 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.45 | −0.19 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.35 |

| Multiracialc | −0.07 | 0.14 | −0.06 | 0.13 | −0.17 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.24 | −0.21 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.18 |

| Parental Support | −0.46*** | 0.07 | −0.52*** | 0.09 | −0.46*** | 0.08 | −0.45*** | 0.11 | −0.55* | 0.23 | −0.53*** | 0.13 |

| Close Friend Support | −0.10 | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.08 | −0.15* | 0.08 | −0.08 | 0.12 | −0.38 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0.15 |

| Stress of Disclosure to Family | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.16* | 0.08 | −0.02 | 0.10 | 0.28* | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.12 |

| Stress of Disclosure to Friends | 0.18* | 0.07 | 0.18* | 0.09 | 0.24** | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.25* | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.12 |

| Parental Support X Stress of Disclosure to Family | -- | -- | −0.21* | 0.10 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.05 | 0.25 | −0.39*** | 0.09 |

| Parental Support X Stress of Disclosure to Friends | -- | -- | 0.07 | 0.11 | -- | -- | -- | -- | −0.12 | 0.15 | 0.23* | 0.11 |

| Close Friend Support X Stress of Disclosure to Family | -- | -- | 0.18 | 0.10 | -- | -- | -- | -- | −0.11 | 0.23 | 0.39*** | 0.11 |

| Close Friend Support X Stress of Disclosure to Friends | -- | -- | −0.13 | 0.10 | -- | -- | -- | -- | −0.18 | 0.15 | −0.14 | 0.11 |

| R2 | 0.28*** | 0.04 | 0.32*** | 0.05 | 0.31*** | 0.05 | 0.26*** | 0.07 | 0.37*** | 0.06 | 0.33*** | 0.06 |

Reference group: Woman.

Reference group: Non-Latino.

Reference group: White.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

We then fit a latent interaction model to examine whether parental support and close friend support differed in whether each buffered the relation between stress of disclosure to family, stress of disclosure to friends, and depressive symptoms. Then we compared fit between the interaction model and a model with latent interactions constrained to zero with scaling corrected log likelihood difference testing to determine whether the non-interaction model resulted in significant loss of fit (Maslowsky, Jager, & Hemken, 2015). Using the Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square difference test (Satorra & Bentler, 2001), the difference between models was not significant, Δχ2 = 5.79, df = 4, p = .22. Thus, the model with interactions did not fit significantly better than the model without interactions. The interaction between parental support and stress of disclosure to family was significant, indicating a weak buffering effect of parental support on the relation between stress of disclosure to family and depressive symptoms. Parental support did not moderate the relation between stress of disclosure to friends and depressive symptoms; further, close friend support did not interact with either type of disclosure stress to predict depressive symptoms. Those who reported the lowest parental support and the highest stress of disclosure to family reported the highest depressive symptoms. At low levels of stress of disclosure to family, those who reported higher parental support reported higher depressive symptoms than those who reported low levels of parental support.

We then conducted a main effects model by groups to establish adequate model fit. For bisexual women, high levels of parental and close friend support predicted lower levels of depressive symptoms; high levels of stress of disclosure to friends predicted higher levels of depressive symptoms. For men, high levels of parental support and low levels of stress of disclosure to family significantly predicted lower levels of depressive symptoms. All other main effects were nonsignificant.

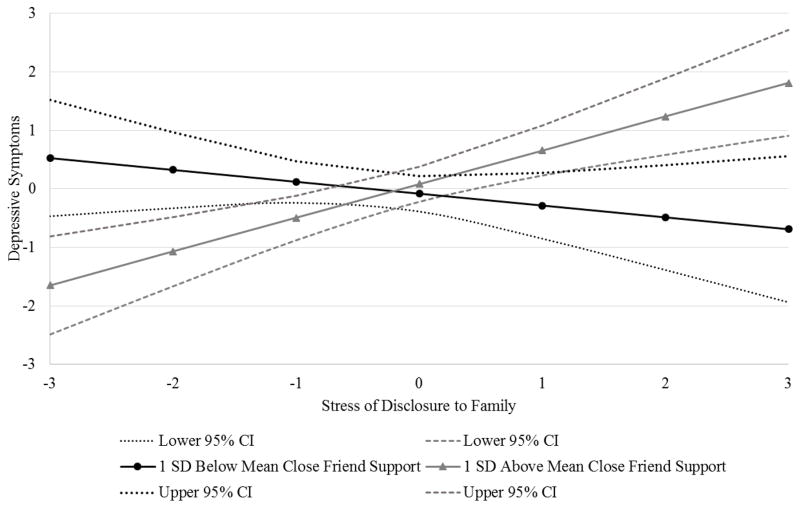

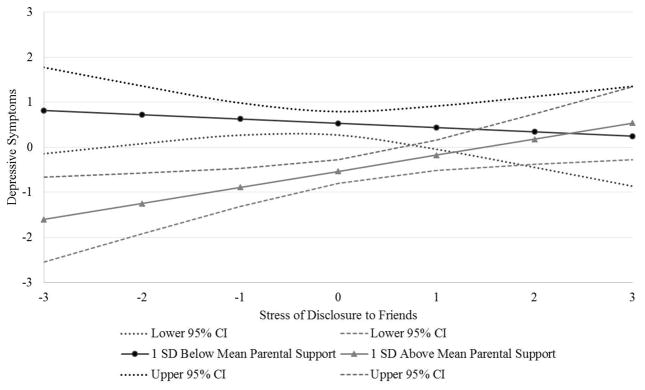

To examine our research question of whether there were differences between bisexual women and men on interactions between social support and disclosure stress on depressive symptoms, we then conducted a multiple group latent interaction model. We held metric invariance in this model: factor loadings on latent constructs were constrained to be equal across groups. The multiple group interaction model fit significantly better than the model with interactions constrained to zero, Δχ2 = 21.23, df = 8, p = .007. There were no significant interactions predicting depressive symptoms for bisexual women. For men, the interactions between parental support and stress of disclosure to family, parental support and stress of disclosure to friends, and close friend support and stress of disclosure to family moderately predicted depressive symptoms. Similar to the interaction between parental support and stress of disclosure to family in the single group model, for bisexual men, low levels of parental support were associated with the highest levels of depressive symptoms when stress of disclosure to family is similarly high. We show a graphical representation of the interaction between stress of disclosure to family and close friend support with confidence intervals for regions of significance in Figure 2. Notably, high levels of close friend support appear to exacerbate depressive symptoms at high levels of stress of disclosure to family. Finally, the interaction between parental support and stress of disclosure to friends suggested a similar exacerbating effect of parental support on the association between stress of disclosure to friends and depressive symptoms. However, visual inspection of this interaction and its regions of significance (Figure 3) showed that parental support has little effect on depressive symptoms when stress of disclosure to friends is high.

Figure 2.

Graphical Representation of the Interaction Between Close Friend Support and Stress of Disclosure to Family on Depressive Symptoms for Bisexual Men.

Figure 3.

Graphical Representation of the Interaction Between Parental Support and Stress of Disclosure to Friends on Depressive Symptoms for Bisexual Men.

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to examine the influence of social support on the relation between disclosure stress and depressive symptoms in a sample of cisgender bisexual youth using the framework of the minority stress model (Meyer, 2003). Results show a complex interplay between family and friend contexts and health, including both intuitive and surprising findings.

In the full sample main effects model, when holding all other factors including covariates constant, the only variables that had unique effects on depressive symptoms were stress of disclosure to friends and parental support. At first glance, this finding seems counter-intuitive considering there were additional significant zero-order correlations between study variables and depressive symptoms, including parental and close friend support. However, considering the domain of the minority stress model we have examined, i.e., expectations of rejection (Meyer, 2003), it is likely that LGB youth anticipate negative reactions, discrimination, and a loss of support from their parents when they come out, yet are often met with warmth and support (D’Augelli et al., 1998; Mufioz-Plaza et al., 2002). Such unanticipated support could bolster mental health. On the other hand, if youth are accurate in their perception that family members will respond negatively, disclosure stress may simply have less influence on mental health than if youth expected family members to be supportive. Thus, negative parental reaction to youths’ disclosure would likely have stronger impact on youth who did not anticipate a negative reaction than for those who expected it. Similarly, research has shown that support from close friends has less influence on well-being than other types of peer support, such as support from classmates (Harter, 1990), likely because support from close friends is expected. When bisexual youths’ close friends are supportive, such support may have less impact than support from others in their lives; in contrast, unsupportive responses from close friends have major impacts on mental health among bisexual youth. We extend the current literature to show that disclosure stress and social support from family and friends differentially influence depressive symptoms among bisexual youth; however, the links between overall minority stress, reactions to disclosure, and outcomes for bisexual youth should be examined in depth for further explication of these findings.

In the full group model, the interaction between parental support and stress of disclosure to family was the only significant interaction associated with depressive symptoms. Though an intuitive finding, it is interesting in the context of research that has shown bisexual people report that, even at their most accepting, family members respond to bisexual disclosure with “that’s fine, but…” (McClelland et al., 2016, p. 8). This finding expands on studies to show that parental support is helpful as bisexual youth navigate the disclosure process with family members even if prior studies show that this support can be ambivalent or undermined by parents’ attitudes toward bisexuality (McClelland et al., 2016).

Further, when it is difficult to disclose to friends, support from others may not make it easier: Stress related to disclosure to friends significantly predicted depressive symptoms as a main effect but was not buffered by either parental or close friend support. Bisexual youth also report stigmatized responses and rejection from close friends after disclosure (McClelland et al., 2016; McLean, 2007), thus bisexual youth must navigate between stress related to concealment of their sexual identity and stress related to disclosure (Meyer, 2003). Developmentally, this may be especially stressful for bisexual youth as they experience the typical developmental changes of adolescence, increasingly turning to their friends rather than their parents for support, asserting their autonomy, formulating an identity separate from their family (Brown & Lawson, 2009), and initiating intimate romantic relationships (Collins & Sroufe, 1999). Thus, the vital developmental role of friends at this time may make bisexual youth especially vulnerable to rejection from friends and subsequently increase the stress associated with disclosure to them.

However, these models differed by gender, as can be seen in the multiple group and interaction models. Parental support predicted depressive symptoms for bisexual women and men; close friend support also predicted depressive symptoms for bisexual women. Yet, this interaction only holds for bisexual men: Men who received the lowest parental support reported the highest depressive symptoms when the stress of disclosing was high. Further, at high levels of stress of disclosing to family, depressive symptoms were highest for men who reported high close friend support. Longitudinal data would help disentangle this finding: Depending on directionality, bisexual men may seek out more support from close friends because they are depressed or because of rejection from family members. There is also a possibility that these men may be co-ruminating with their close friends, exacerbating depressive symptoms. Sexual minority youth have been found to ruminate more than their heterosexual counterparts, which in turn mediated their higher reports of depression and anxiety (Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2008). Further, bisexual people report more sexual identity rumination than do gay men and lesbians (Galupo, Mitchell, & Davis, 2015). Considering the high levels of close friend support reported by the bisexual youth in this study and evidence that sexual minority youth tend to go to their LGB close friends for support regarding sexual identity concerns (Nesmith et al., 1999; Mufioz-Plaza et al., 2002), this rumination could be especially harmful to bisexual men. Another possible explanation for this finding is that the tension between close friend support and disclosure to family stress may stem from young male friendships that increasingly become gendered and sexualized during the transition from childhood to adulthood (Way, 2011). As such, cisgender bisexual male youth may turn to a trusted friend who provides general support but who is rejecting of their bisexuality. This interplay between family and friendships suggests future research should carefully consider the role of friendships on the health and well-being of sexual minority male youth.

For bisexual women, close friend and parental support may be protective for depressive symptoms, but they do little to buffer the stress of disclosing to family members and friends, at least with respect to depressive symptoms. Research shows disclosure stress has important implications for bisexual women’s mental health (Baams, Grossman, & Russell, 2015); yet, in this study, we expand on this literature to find that support from people in bisexual women’s lives does not buffer disclosure stress in the ways that it does for bisexual men. Higher reports of mental distress and poor well-being among bisexual youth have been shown to be mediated by less family acceptance, less LGB social contact, less family support, higher internalized homophobia, and lower levels of disclosure (Shilo & Savaya, 2012). In addition, female bisexual youth report less family acceptance and LGB social contact. This study did not explore the potential interactions between these constructs, but it could be likely that bisexual women report elevated levels of minority stressors associated with social and cognitive aspects of sexual identity (internalized homophobia, family acceptance, and disclosure) that are then not buffered by social coping resources (family support and LGB social contact). Further, considering we did not find protective effects of parental and close friend support among bisexual women, support from families and friends may not serve as a substitute for the role of LGB communities, with which bisexual people are less likely to have contact (Shilo & Savaya, 2012), in reducing poor mental health among bisexual youth.

Finally, stress of disclosure to friends, but not stress of disclosure family, was related to depressive symptoms among women. We speculate that this finding, and the fact that neither parental or close friend support was protective, could be because bisexual women and their sexual identities are often sexualized by others when they disclose, including by romantic partners (McAllum, 2014; McClelland et al., 2016). Thus, the people bisexual women expect to be supportive are also the people most likely to minimize their bisexual identities or to stigmatize or blame them. Though numerous studies show bisexual women can clearly describe instances of bisexual stigma (Bostwick & Hequembourg, 2013; McAllum, 2014; McClelland et al., 2016), they deny labeling these experiences as discrimination. Researchers should further explore the distinct role of stress related to sexualization and objectification on the mental health of bisexual women.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study is cross-sectional; thus, it is not possible to confirm the direction of the associations. However, temporality may be inferred: Disclosure stress questions were related to events that occurred in the past, social support questions referred to the present time, and we measured depressive symptoms in the past two weeks. A longitudinal examination would illuminate whether the influence of disclosure stress on depressive symptoms lessens over time, similar to other studies that show positive outcomes associated with disclosing across the lifespan (D’Augelli & Grossman, 2001; D’Augelli et al., 1998; Russell et al., 2014). However, as a post-hoc analysis, we examined whether the association between disclosure stress and depressive symptoms was moderated by time since first disclosure; this interaction was not significant, suggesting that the current models are robust and the findings are not dependent on time since first disclosure.

We recognize the nuanced complexities of the disclosure process that we were unable to address with the data available. Though these data provided us with a unique opportunity to explore disclosure processes among bisexual youth, they were not immune from the same limitations of much of the literature on disclosure, particularly in regards to items addressing the unique disclosure experiences of bisexual youth. Disclosure of sexual or gender identity does not occur just once in a young person’s life; instead, the decision to disclose or not occurs with every new person met (Cox et al., 2011). We do not know whether the close friend to whom youth disclosed or from whom they received support was straight, lesbian/gay, bisexual, or transgender, which could have important implications for mental health considering bisexual people report rejection from both straight and gay/lesbian peers (Ross et al., 2010). Moreover, we do not know whether the youth came out as bisexual or as some other non-heterosexual sexual identity, which would provide important context for our results considering that recent research has demonstrated that bisexual people may come out as bisexual, lesbian/gay, or not at all (Scherrer et al., 2015) and which could have critical implications for stress and health.

Our sample originally came from a study of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth. Bisexual people are rarely studied independently of lesbians and gay men, which then results in datasets that assume singular experiences of LGB (and sometimes T) people, including the data used in the current study. We strongly encourage researchers who study disclosure among sexual and gender minority youth to not assume the experiences of LGB people are the same and include questions that capture nuances of disclosure, especially among those who do not identify as gay or lesbian. These questions include asking youth their relationship to whom they disclosed and this person’s sexual and gender identity; the sexual or gender identity they initially disclosed as and what identity they subsequently identified as for each disclosure thereafter. We recognize these limitations and acknowledge we are unable to capture these important nuances with the current data; however, we also acknowledge the important contribution of our study in illuminating the unique disclosure experiences of cisgender bisexual youth.

This study utilizes a nonpopulation-based sample of cisgender bisexual youth. In addition to our limited ability to generalize to all bisexual youth, a limitation of this sample is their uniform identification as cisgender. As we are unaware of any studies examining the experiences of transgender and gender diverse bisexual men and women we encourage researchers to address this gap by specifically recruiting from such populations. Research clearly illustrates transgender and gender diverse people experience greater levels of discrimination and victimization than their cisgender peers (Almeida, Johnson, Corliss, Molnar, & Azrael, 2009); the results of an examination on the intersection of gender diverse and bisexual identities would yield great insight into the role of social support during disclosure processes.

Still, our sample is also a strength as this is one of the largest samples of bisexual youth collected in a study that addresses sexual minority-specific questions (such as experiences associated with disclosing one’s sexual identity) and important outcomes such as depressive symptoms. Results and interpretation are limited in their generalizability; however, results still contribute to gaps in the literature on disclosure experiences of bisexual youth. Our results suggest different processes based on the gender of bisexual youth that contribute to minority stressors associated with monosexism, heterosexism, and gender nonconformity. Our study demonstrates the importance of research that examines monosexist stigma and stress as this system of inequality has been understudied, especially quantitatively. This study speaks to mounting evidence in health sciences of the nuances and variations embedded within contemporary LGB experiences and well-being and their relations to significant others within and beyond families. Researchers should examine the influence of gender differences, societal gender norms, and sexism among bisexual people, not only in disclosure experiences and support networks, but also in psychological processes and societal pressures influencing decisions about sexual identity disclosure.

Conclusion and Implications

Bisexual people are at risk for greater health disparities than their lesbian and gay counterparts; yet, these youths’ experiences are rarely examined independently. Within the scope of the minority stress model, we contribute to the literature on disclosure stress for bisexual youth. Disclosure to friends is stressful and related to depressive symptoms. Parental support has an important mitigating influence when coming out to family members is stressful, especially for bisexual men; at the same time, close friend support may exacerbate poor health related to stressful disclosure to parents among bisexual men. In contrast, bisexual women seem not to benefit from social support even when stressful disclosure to friends influences health. Our nuanced examination of these relationships demonstrate ways in which family members and clinicians can best support bisexual youth as they disclose their sexual identities. Clinicians can encourage parents to support their bisexual youth, regardless of gender and gender role expectations, and can help bisexual youth navigate potentially difficult disclosure experiences with both family and friends. Supportive adults should also recognize that they may hold monosexist beliefs, even when they are supportive, and should accept youths’ bisexuality without qualification.

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from the Risk and Protective Factors for Suicide among Sexual Minority Youth study, designed by Arnold H. Grossman and Stephen T. Russell, and supported by Award Number R01MH091212 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Almeida J, Johnson RM, Corliss HL, Molnar BE, Azrael D. Emotional distress among LGBT youth: The influence of perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:1001–1014. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9397-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Chi-square statistics with multiple imputation. 2010 Retrieved from http://statmodel2.com/download/MI7.pdf.

- Baams L, Grossman AH, Russell ST. Minority stress and mechanisms of risk for depression and suicidal ideation among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Developmental Psychology. 2015;51:688–696. doi: 10.1037/a0038994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Beck Depression Inventory II. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick W, Hequembourg A. “Just a little hint”: Bisexual-specific microaggression and their connection to epistemic injustices. Culture, Health, & Sexuality. 2014;16:488–503. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.889754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B, Larson J. Peer relationships in adolescence. In: Lerner R, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 3. Vol. 2. New York: Wiley; 2009. pp. 74–103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Callis AS. The black sheep of the pink flock: Labels, stigma, and bisexual identity. Journal of Bisexuality. 2013;13:82–105. doi: 10.1080/15299716.2013.755730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cass VC. Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality. 1979;4:219–235. doi: 10.1300/J082v04n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Sroufe LA. Capacity for intimate relationships: A developmental construction. In: Furman W, Brown BB, Feiring C, editors. The development of romantic relationships in adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 125–147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cox N, Dewaele A, van Houtte M, Vincke J. Stress-related growth, coming out, and internalized homonegativity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: An examination of stress-related growth within the minority stress model. Journal of Homosexuality. 2011;58:117–137. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2011.533631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH. Disclosure of sexual orientation, victimization, and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:1008–1027. doi: 10.1177/088626001016010003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Hershberger SL, Pilkington NW. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and their families: Disclosure of sexual orientation and its consequences. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68:361–371. doi: 10.1037/h0080345. discussion 372–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM. “I”m straight, but I kissed a girl’: The trouble with American media representations of female-female sexuality. Feminism & Psychology. 2005;15:104–110. doi: 10.1177/0959353505049712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond L. Just how different are female and male sexual orientation? 2013 Oct 17; [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.cornell.edu/video/lisa-diamond-on-sexual-fluidity-of-men-and-women.

- Eisner S. Bi: Notes for a bisexual revolution. New York: Seal Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Galupo MP, Mitchell RC, Davis KS. Sexual minority self-identification: Multiple identities and complexity. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2015;2:355–364. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grollman EA. Multiple forms of perceived discrimination and health among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2012;53:199–214. doi: 10.1177/0022146512444289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Developmental differences in the nature of self-representations: Implications for the understanding, assessment, and treatment of maladaptive behavior. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1990;14:113–142. doi: 10.1007/BF01176205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Emotion regulation and internalizing symptoms in a longitudinal study of sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:1270–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01924.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hequembourg AL, Brallier SA. An exploration of sexual minority stress across the lines of gender and sexual identity. Journal of Homosexuality. 2009;56:273–298. doi: 10.1080/00918360902728517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger SL, D’augelli AR. The impact of victimization on the mental health and suicidality of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:65–74. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.31.1.65. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel T, Mohr JJ. Attitudes toward bisexual women and men. Journal of Bisexuality. 2004;4:117–134. doi: 10.1300/J159v04n01_09. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan KM, Deluty RH. Social support, coming out, and relationship satisfaction in lesbian couples. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2000;4:145–164. doi: 10.1300/J155v04n01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Legate N, Ryan RM, Weinstein N. Is coming out always a “good thing”? Exploring the relations of autonomy support, outness, and wellness for lesbian, gay, and bisexual Individuals. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2011;3:145–152. doi: 10.1177/1948550611411929. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Pollitt AM, Russell ST. Depression and sexual orientation during young adulthood: Diversity among sexual minority subgroups and the role of gender nonconformity. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0515-3. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little T. Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widaman KF. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:151–173. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malecki CK, Demaray MK, Elliott SN, Nolten PW. The child and adolescent social support scale. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, Stall R, Smith Ha, McGinley J, … Brent Da. Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A meta-analytic review. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;49:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslowsky J, Jager J, Hemken D. Estimating and interpreting latent variable interactions: A tutorial for applying the latent moderated structural equations method. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2015;39:87–96. doi: 10.1177/0165025414552301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllum MA. “Bisexuality is just semantics…”: Young bisexual women’s experiences in New Zealand secondary schools. Journal of Bisexuality. 2014;14:75–93. doi: 10.1080/15299716.2014.872467. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland SI, Rubin JD, Bauermeister JA. Adapting to injustice: Young bisexual women’s interpretations of microaggressions. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0361684316664514. Advance online publication. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLean K. Hiding in the closet?: Bisexuals, coming out and the disclosure imperative. Journal of Sociology. 2007;43:151–166. doi: 10.1177/1440783307076893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2013;1:3–26. doi: 10.1037/2329-0382.1.S.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milfont TL, Fischer R. Testing measurement invariance across groups: Application in cross cultural research. International Journal of Psychology Research. 2010;3:111–121. doi: 10.21500/20112084.857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mooijaart A, Satorra A. On insensitivity of the chi-sqaure model test to non-linear misspecification in structural equation models. Psychometrika. 2009;74:443–455. doi: 10.1007/s11336-009-9112-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mufioz-Plaza C, Quinn SC, Rounds KA. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender students: Perceived social support in the high school environment. The High School Journal. 2002;85:52–63. doi: 10.1353/hsj.2002.0011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 7. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nesmith AA, Burton DL, Cosgrove TJ. Gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth and young adults. Journal of Homosexuality. 1999;37:95–108. doi: 10.1300/J082v37n01_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompili M, Lester D, Forte A, Seretti ME, Erbuto D, Lamis DA, … Girardi P. Bisexuality and suicide: A systematic review of the current literature. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2014;11:1903–1913. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Hunter J, Maguen S, Gwadz M, Smith R. The coming-out process and its adaptational and health-related associations among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: Stipulation and exploration of a model. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:133–160. doi: 10.1023/A:1005205630978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Reid H. Gay-related stress and its correlates among gay and bisexual male adolescents of predominantly Black and Hispanic background. Journal of Community Psychology. 1996;24:136–159. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6629(199604)24:2<136::AID-JCOP5>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Predictors of substance use over time among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: An examination of three hypotheses. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:1623–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. A model of sexual risk behaviors among young gay and bisexual men: Longitudinal associations of mental health, substance abuse, sexual abuse, and the coming-out process. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18:444–460. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross LE, Dobinson C, Eady A. Perceived determinants of mental health for bisexual people: A qualitative examination. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:496–502. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.156307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Toomey RB, Ryan C, Diaz RM. Being out at school: The implications for school victimization and young adult adjustment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84:635–643. doi: 10.1037/ort0000037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rust PC. “Coming out” in the age of social constructionism. Gender & Society. 1993;7:50–77. doi: 10.1300/J155v01n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika. 2001;66:507–514. doi: 10.1007/BF02296192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Ream GL. Sex variations in the disclosure to parents of same-sex attractions. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:429–438. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer KS, Kazyak E, Schmitz R. Getting “bi” in the family: Bisexual people’s disclosure experiences. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2015;77:680–696. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets RL, Mohr JJ. Perceived social support from friends and family and psychosocial functioning in bisexual young adult college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:152–163. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.56.1.152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shilo G, Savaya R. Effects of family and friend support on LGB youths’ mental health and sexual orientation milestones. Family Relations. 2011;60:318–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00648.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shilo G, Savaya R. Mental health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and young adults: Differential effects of age, gender, religiosity, and sexual orientation. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2012;22:310–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00772.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson RJ, Grossman AH, Russell ST. Sources of social support and mental health among LGB youth. Youth & Society. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0044118X16660110. Advance online publication 0044118X16660110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way N. Deep secrets: Boys’ friendships and the crisis of connection. Boston: Harvard University Press; 2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg MS, Williams CJ, Pryor DW. Dual attraction: Understanding bisexuality. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]