Abstract

Objective: The objective of this study was to estimate the importance of risk factors affecting sexual function in sexually active midlife women.

Materials and Methods: A cohort of 780 women undergoing the menopausal transition was surveyed each year for up to 7 years. Data were collected from sexually active women on sexual function, including frequencies of enjoyment, arousal, orgasm, passion for partner, satisfaction with partner, pain, lack of lubrication, fantasizing, and sexual activity. Data were also collected on a large number of potential risk factors for sexual dysfunction, including behaviors (smoking and alcohol use), health status (overall and frequency of different disorders), and demographic information (race, education, income, etc.). Height and weight were measured at an annual clinic visit; serum hormone concentrations were assayed using blood samples donated annually. Data on individual outcomes were examined with ordinal logistic regression models using individual as a random effect. An overall sexual function score was constructed from individual outcome responses, and this score was examined with linear regression. All factors with univariate associations of p < 0.1 were considered in multivariate model building with stepwise addition.

Results: A total of 1,927 women-years were included in the analysis. Women with much more physical work than average had higher sexual function scores and higher rates of enjoyment, passion, and satisfaction. Higher family income was associated with lower sexual function score and more frequent dry sex. Married women had significantly lower sexual function scores, as did those with frequent irritability or vaginal dryness. A higher step on the Ladder of Life was associated with a higher sexual function score and higher frequency of sexual activity.

Conclusions: The factors associated with sexual outcome in menopausal women are complex and vary depending on the sexual outcome.

Keywords: : sexual function, menopause, cohort study

Introduction

Sexual dysfunction is a common, complex issue with many potential contributing factors. Up to 43% of women overall1 and up to 50% of midlife and older women2 experience some level of sexual dysfunction, with roughly 30% of U.S. women reporting a lack of interest in sex, ∼25% unable to achieve orgasm, and 23% not finding sex pleasurable.3s

As women transition through menopause, they frequently experience changes in their sexual function, with increases in sexual dysfunction being common1,4–8 and diagnosed as a group under the term “genitourinary syndrome of menopause.”2 Although at least one survey showed a decrease in sexual dysfunction with age,3 others have found that, for women, sexual problems peak in middle age,1,9 although serious sexual dysfunction remains rare.10 The causes of sexual dysfunction during midlife are likely multifactorial and include decreasing estrogen levels,4 relationship changes,11 and changes in general health.4,12 However, most studies examining sexual function in menopausal women have been cross sectional,7,13–20 which limits their ability to study sexual function during the menopausal transition. In addition, many physical and psychological factors are associated with sexual dysfunction,3,8,21 and these must be considered in any analysis.

One longitudinal study, which followed women for 8 years during the menopausal transition found a decrease in desire, arousal, orgasm, and frequency of sex during the transition22 and an increase in vaginal dryness over the same period23; the most important predictor in that study was prior sexual function as defined by the Personal Experiences Questionnaire.12 This study was limited in the risk factors analyzed, however, as only the effects of menopausal status, hormone levels, and previous sexual function were reported; thus, the effects of health status, relationship status, and activity levels were not considered. We previously reported that in the Midlife Women's Health Study, sexual activity was affected by relationship status, health, activity levels, and estradiol levels.24

The objective of this study was to estimate the importance of a number of risk factors for sexual dysfunction among sexually active women during the menopausal transition. Toward this objective, we analyzed data available from a cohort study of perimenopausal women aged 45–54 years at baseline who were followed for up to 7 years and queried about a large number of sexual function outcomes and many potential risk factors.

Materials and Methods

All participants provided written informed consent according to procedures approved by the University of Illinois and Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Boards. The study design for the parent study is described in detail elsewhere.25 Briefly, a cohort study of hot flashes among women 45–54 years of age was conducted starting in 2006 among residents of Baltimore and its surrounding counties. Women were recruited by mail, and were included if they were in the target age range, had intact ovaries and uteri, and were pre- or perimenopausal. Exclusion criteria consisted of pregnancy, a history of cancer, exogenous female hormone or herbal/plant substance, and no menstrual periods within the past year.

Participants made a baseline clinic visit, which included measurement of height and weight to calculate body mass index (BMI) and completion of a detailed 26-page baseline survey. The questionnaires have been used in many previous studies to assess self-report of menopausal symptoms.26–28 Although we and others have not validated the self-report of menopausal symptoms by comparing self-report of menopausal symptoms to an objective measurement such as change in core body temperature, self-report of hot flashes has been accepted as a valid measure by both the National Institute on Aging and the Food and Drug Administration.29,30

Participants were asked to complete a brief questionnaire during a clinic visit annually after the baseline visit. This questionnaire repeated all previous questions about sexual activity and behavior in the previous year, and BMI was calculated during the visit. Blood samples were collected at each scheduled clinic visit and stored until measurement of hormone levels as described below. Menopausal status was defined as follows: premenopausal women were those who experienced their last menstrual period within the past 3 months and reported 11 or more periods within the past year; perimenopausal women were those who experienced (1) their last menstrual period within the past year, but not within the past 3 months or (2) their last menstrual period within the past 3 months and experienced 10 or fewer periods within the past year; postmenopausal women were those women who had not experienced a menstrual period within the past year.

Follow-up was discontinued for women if they reported hormone therapy, an oophorectomy, or a cancer diagnosis. At the year 4 visit, follow-up was discontinued for women determined to be postmenopausal. Recruitment and follow-up were completed in late June 2015, with women followed for 1–7 years, based on time of enrollment and menopause status at year 4.

Serum samples extracted from the collected blood samples were used to measure estradiol and progesterone levels in each sample using commercially available, previously validated ELISA kits (DRG, Springfield, NJ).31–34 The minimum detection limits and intra-assay coefficients of variation were as follows: estradiol 7 pg/mL, 3.3% ± 0.17%; testosterone 0.04 ng/mL, 2.2% ± 0.56%; and progesterone 0.1 ng/mL, 2.1% ± 0.65%. The average interassay coefficient of variation for all assays was <5. No testosterone values were below the limit of detection; for estradiol concentrations among all women enrolled in this study, the number of values below the limit of detection during year 1 was as follows: visit 1, n = 7; visit 2, n = 3; visit 3, n = 13; and visit 4, n = 6. In the case of values lower than the detection limits for the assay, we used the limit of detection as the hormone value. Each sample was measured in duplicate within the same assay. Progesterone, testosterone, and estradiol levels were log transformed to meet normality assumptions.

This analysis was conducted among the subset of women who reported being sexually active. A variety of outcomes were considered based on the items included in the Short Personal Experiences Questionnaire (SPEQ)35,36 related to the women themselves: frequency of enjoyment of sex, frequency of arousal during sex, frequency of orgasm during sex, frequency of passion for partner, frequency of satisfaction with partner, frequency of pain during sex, frequency of lubrication during sex, frequency of sexual fantasies, and frequency of sex. Responses were recorded on a Likert scale, with 1 being “Not at All” and 5 being “A Great Deal”; the exceptions were frequency of sexual fantasies and frequency of sex, in which the possible responses for frequency in the last month were “Never,” “Less than once a week,” “Once or twice a week,” “Several times a week,” “Once a day, Sometimes twice,” and “Several times a day.”

Analyses regarding individual outcomes among sexually active women were conducted using ordinal logistic regression. A summary variable for a group of outcomes (enjoyment, arousal, orgasm, passion, satisfaction, lubrication, fantasies, and frequency) was created, and participant scores were calculated by adding the Likert scale values, with higher values indicating a “better” outcome; this is comparable to the SPEQ total score (SPEQT) measure,35,36 but is not identical as this study did not ask sexually active women about partner difficulties with sex. Analyses of this summary variable were conducted using a linear regression.

As some of the previously identified risk factors to be considered (hot flashes, smoking, and alcohol use) could be measured in a variety of ways, different potential forms were considered. Hot flashes experienced over the last year and for the last 30 days were considered as both binary variables (yes/no) and ordinal variables for frequency (never, monthly, weekly, or daily) and severity (none, mild, moderate, or severe). Smoking was considered as a categorical variable (current, former, and never smokers) and as a linear variable (packs per year), transformed by square root to meet linearity assumptions. Alcohol consumption was considered as a binary variable (at least 12 drinks in the last year or not) and as linear variables for number of days drinking per month, number of drinks per day drinking, and number of drinks per month; days per month and drinks per day were also square root transformed. BMI was included as a linear variable, as were current step on the Ladder of Life (a measure of quality of life),37 number of pregnancies, and log-transformed values for estradiol, progesterone, and testosterone. Menopause status (pre, peri, or post-), race (white, black, or other), education (graduated college or not), playing a sport (yes/no), and history of pregnancy, hormone replacement therapy, herbal treatment for menopause, and contraceptive use (yes/no) were included only as categorical variables. A number of variables (physicality of work, physicality of leisure activity, income, health, and frequency of fatigue, depression, vaginal discharge, vaginal dryness, incontinence, and irritability) were considered in both categorical and linear form; if both forms of the variable were significant in the univariate analysis and the categorical version showed a clear linear trend, the linear version was used in multivariate model building.

For each outcome, univariate models were fit for all potential risk factors. All risk factors with a p-value of ≤0.1 were considered in multivariate models with only main effects, and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC)-based backward selection was used to identify the final models. All models were fit in R 3.0.3,38 with linear regression models fit using lme439 and ordinal logistic regression models fit using multgee.40

Results

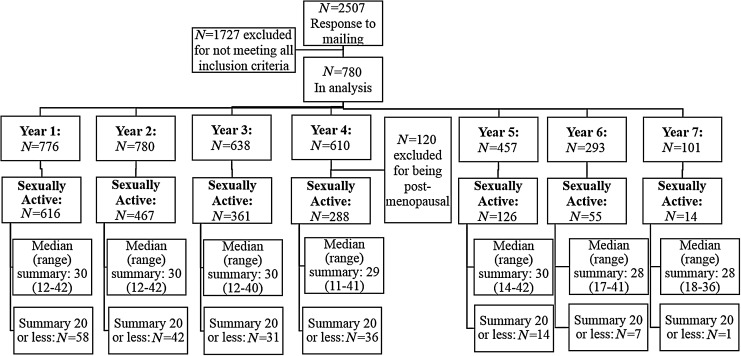

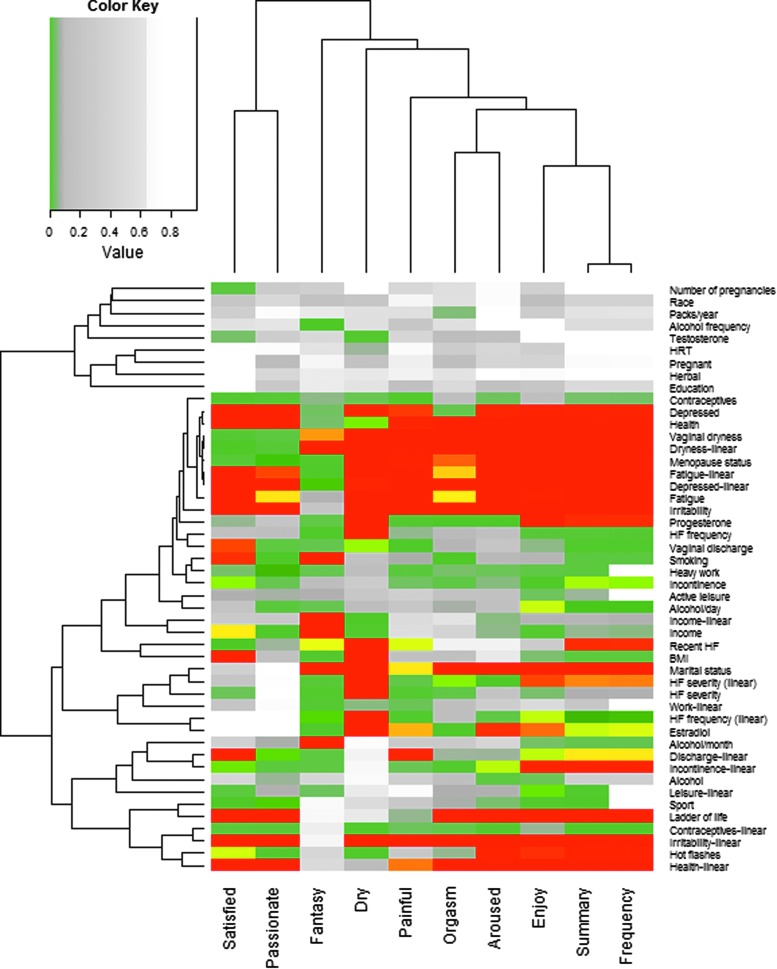

Figure 1 shows the number of women in each phase of the study, and Table 1 shows the distribution of responses to each of the potential outcomes. The decreasing sample size in later years was primarily due to censoring by the end of the study. The results of the univariate analyses within the subset of sexually active women are shown in Figure 2. Risk factors associated with increasing the frequency of fantasizing were distinct from most other outcomes, including increased alcohol consumption, smoking, lower income, and increased vaginal dryness. Frequency of dry sex was also somewhat distinct from other outcomes, being increased by risk factors related to menopause (hot flashes, peri- and postmenopausal status, vaginal dryness and discharge, and decreased progesterone and estrogen levels).

FIG. 1.

Flowchart of women enrolled in the study. The summary is a calculated value to summarize scores across all outcomes.

Table 1.

Number of Woman-Years Reporting Each Level of Each Outcome Among Sexually Active Women

| Question | 1 (not at all) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (a great deal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How enjoyable are sexual activities currently for you? | 68 | 199 | 456 | 656 | 640 |

| How often during sex activities do you feel aroused or excited? | 67 | 201 | 397 | 681 | 670 |

| Do you currently experience orgasm (climax) during sex activity? | 114 | 201 | 344 | 669 | 688 |

| How much passionate love do you feel for your partner? | 103 | 238 | 335 | 461 | 792 |

| Are you satisfied with your partner(s) as a lover? | 121 | 185 | 323 | 514 | 782 |

| Do you currently experience any pain during intercourse? | 1214 | 393 | 193 | 106 | 47 |

| Do you currently experience any lack of vaginal wetness (lubrication) during sex activities? | 759 | 484 | 353 | 263 | 134 |

| Never | <Weekly | Weekly | Daily | Several times/day | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| About how many times have you had sexual thoughts or fantasies (e.g., daydreams) during the past month? | 223 | 632 | 959 | 144 | 85 |

| How many times during the past month have you had sexual intercourse? | 357 | 665 | 991 | 19 | 10 |

FIG. 2.

Bonferroni-corrected p-values from univariate analyses for sexual factors among sexually active women, by risk factor. Red values are highly significant (p ≤ 0.01), yellow values are moderately significant (p ≤ 0.05), gray values are borderline significant (p ≤ 0.1), and white values are nonsignificant (p > 0.1). Dendrograms are based on Euclidean distance. BMI, body mass index; HRT, hormone replacement therapy.

Most other outcomes were strongly related to increased frequency of depression (decreased frequency, arousal, enjoyment, satisfaction, passion, and orgasms but increased fantasizing, pain, and dry sex), fatigue (decreased frequency, arousal, enjoyment, satisfaction, passion, and orgasms, but increased fantasizing, pain, and dry sex), and irritability (decreased frequency, arousal, enjoyment, satisfaction, passion, and orgasms but increased fantasizing and pain), higher health status (increased frequency, arousal, enjoyment, satisfaction, passion, and orgasms but decreased fantasizing), and postmenopausal status (decreased fantasizing, enjoyment, satisfaction, passion, and arousal but increased pain). Several outcomes were also related to higher estrogen levels (increased arousal, enjoyment, and orgasms but decreased pain), increased frequency of vaginal dryness (decreased arousal, enjoyment, satisfaction, passion, and orgasms but increased pain) or discharge (decreased frequency, arousal, enjoyment, satisfaction, passion, and orgasms but increased), being married (increased pain and dry sex but decreased arousal, enjoyment, and orgasms), hot flashes (decreased frequency, arousal, enjoyment, satisfaction, passion, and orgasms but increased pain), or higher perceived quality of life (increased arousal, enjoyment, satisfaction, passion, and orgasms but decreased pain).

The results of the multivariable analysis for the summary sexual function score are shown in Table 2; positive coefficients indicate increasing sexual function score, while negative coefficients indicate decreasing sexual function score. A higher sexual function score was significantly associated with much heavier work physicality and a higher step on the Ladder of Life. Lower sexual function was significantly associated with increasing income, more frequent irritability and vaginal dryness, less time using oral contraceptives, and being married.

Table 2.

Results of the Fitted Multivariate Model for a Summary Sexual Function Score in Sexually Active Midlife Women

| Coefficient | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| How does your work compare physically to others your age? (average is reference) | ||

| Much heavier | 5.01 | 1.81 to 8.21 |

| Heavier | 0.11 | −1.29 to 1.52 |

| Lighter | 0.32 | −0.74 to 1.39 |

| Much lighter | 0.62 | −0.82 to 2.06 |

| How long did you use oral contraceptives? (1–2 years is reference) | ||

| <1 month | 1.12 | −2.24 to 4.49 |

| 1–5 months | −1.7 | −3.84 to 0.44 |

| 6 months–1 year | −2.38 | −4.41 to −0.36 |

| 3–4 years | −0.63 | −2.27 to 1.01 |

| 5–10 years | −0.01 | −1.49 to 1.47 |

| >10 years | 0.81 | −0.75 to 2.38 |

| Menopause status (perimenopausal is reference) | ||

| Post | −1.08 | −2.90 to 0.74 |

| Pre | −0.15 | −1.22 to 0.95 |

| Annual family income (1 ≤ $20,000 to 4 ≥ $100,000) | −0.72 | −1.37 to −0.07 |

| How many pregnancies have you had? | 0.12 | −0.15 to 0.39 |

| Number of alcoholic drinks/year (estimate) | 0.01 | −0.01 to 0.03 |

| Step on Ladder of Life at present | 1.09 | 0.74 to 1.45 |

| Depressed (0 = never to 4 = more than 5 times per week) | 0.25 | −0.29 to 0.78 |

| Did you ever use HRT? | 0.08 | −2.65 to 2.82 |

| Hot flash frequency (0 = never to 3 = daily) | 0.03 | −0.45 to 0.51 |

| Marital status (divorced is reference) | ||

| Married or living with partner | −2.55 | −3.97 to −1.13 |

| Single | −0.03 | −1.98 to 1.93 |

| Widowed | −0.03 | −4.11 to 4.04 |

| Irritable (0 = never to 4 = more than 5 times per week) | −0.99 | −1.52 to −0.45 |

| Do you play a sport? | 0.68 | −0.43 to 1.78 |

| Health (0 = poor to 4 = excellent) | 0.43 | −0.19 to 1.05 |

| Vaginal dryness (0 = never to 4 = more than 5 times per week) | −0.97 | −1.42 to −0.53 |

Values in bold are significant at the p ≤ 0.05 level.

95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

HRT, hormone replacement therapy.

The results of the multivariable analyses for sexual outcomes among sexually active women are shown in Table 3–5. More physical work activity was associated with more frequent enjoyment, passion, and satisfaction. Women who used oral contraceptives for a longer time experienced more frequent enjoyment and arousal and less frequent painful or dry sex. Postmenopausal women had more frequent painful sex than peri- and premenopausal women and slightly less frequent arousal and activity. Increasing income is associated with higher frequency of arousal and lower frequency of dryness; the effect of income on satisfaction with a partner and sexual enjoyment was nonlinear, with women with moderately high incomes less frequently satisfied than high-income women and middle-income women more frequently enjoying sex than high-income women.

Table 3.

Results (ORs) of the Fitted Multivariate Models for Sexually Active Women During the Menopausal Transition, Showing Only Variables Included in at Least 4 Final Models

| Enjoy | Arousal | Orgasm | Passion | Satisfied | Pain | Dry | Fantasy | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How does your work compare physically to others your age? (average is reference) | |||||||||

| Much heavier | 4.39 (1.51–12.78) | 1.36 (0.53–3.47) | 1.34 (0.27–6.57) | 19.32 (2.24–167.04) | 3.19 (1.2–8.51) | 1.25 (1.07–1.46)a | 1.27 (1.11–1.45)a | 1.19 (1.02–1.38)a | 1.12 (0.5–2.5) |

| Heavier | 1.19 (0.71–2) | 1.14 (0.75–1.74) | 0.75 (0.36–1.58) | 0.98 (0.65–1.47) | 1.16 (0.75–1.77) | 1.12 (0.96–1.31)a | 1.13 (0.99–1.29)a | 1.09 (0.94–1.27)a | 1.36 (0.82–2.25) |

| Lighter | 1.48 (1.01–2.18) | 1.01 (0.73–1.41) | 0.88 (0.51–1.51) | 1.24 (0.88–1.74) | 0.93 (0.67–1.3) | 0.89 (0.76–1.05)a | 0.89 (0.78–1.01)a | 0.92 (0.79–1.07)a | 1.01 (0.69–1.5) |

| Much lighter | 1.29 (0.8–2.06) | 1.09 (0.7–1.69) | 0.62 (0.33–1.18) | 1.34 (0.87–2.08) | 1.55 (0.99–2.43) | 0.8 (0.68–0.94)a | 0.79 (0.69–0.9)a | 0.84 (0.72–0.98)a | 1.25 (0.74–2.11) |

| How long did you use oral contraceptives? (1–2 years is reference) | |||||||||

| <1 month | 0.64 (0.58–0.71)a | 0.71 (0.65–0.78)a | 0.74 (0.65–0.85)a | NA | 2.15 (0.71–6.44) | 0.64 (0.2–2.05) | 1.47 (1.36–1.59)a | 0.51 (0.24–1.11) | 0.88 (0.8–0.97)a |

| 1–5 months | 0.75 (0.67–0.82)a | 0.8 (0.73–0.87)a | 0.82 (0.72–0.94)a | NA | 0.82 (0.46–1.46) | 0.74 (0.41–1.36) | 1.29 (1.19–1.4)a | 0.96 (0.47–1.95) | 0.92 (0.84–1.01)a |

| 6 months–1 year | 0.86 (0.78–0.96)a | 0.89 (0.82–0.97)a | 0.9 (0.79–1.04)a | NA | 0.68 (0.37–1.26) | 1.06 (0.59–1.91) | 1.14 (1.05–1.23)a | 0.69 (0.35–1.35) | 0.96 (0.87–1.06)a |

| 3–4 years | 1.16 (1.05–1.28)a | 1.12 (1.03–1.22)a | 1.11 (0.97–1.27)a | NA | 0.98 (0.59–1.61) | 0.67 (0.4–1.11) | 0.88 (0.81–0.95)a | 0.86 (0.5–1.46) | 1.04 (0.95–1.15)a |

| 5–10 years | 1.34 (1.21–1.48)a | 1.25 (1.15–1.37)a | 1.22 (1.07–1.4)a | NA | 1.08 (0.68–1.72) | 0.61 (0.38–0.96) | 0.77 (0.72–0.84)a | 0.76 (0.47–1.21) | 1.08 (0.99–1.19)a |

| >10 years | 1.55 (1.4–0.13)a | 1.4 (1.29–1.53)a | 1.35 (1.18–1.55)a | NA | 0.89 (0.54–1.45) | 0.4 (0.23–0.67) | 0.68 (0.63–0.74)a | 1.04 (0.64–1.68) | 1.13 (1.03–1.24)a |

| Menopause status (perimenopausal is reference) | |||||||||

| Post | NA | 0.69 (0.44–1.07) | 0.79 (0.39–1.58) | 0.66 (0.38–1.16) | NA | 1.95 (1.14–3.32) | NA | NA | 0.75 (0.42–1.31) |

| Pre | NA | 1.19 (0.86–1.64) | 1.05 (0.59–1.88) | 0.79 (0.56–1.12) | NA | 0.91 (0.66–1.25) | NA | NA | 0.89 (0.62–1.27) |

| Severity of hot flashes (mild is reference) | |||||||||

| None | 1.35 (1.15–1.58)a | NA | 0.84 (0.65–1.09)a | NA | 0.76 (0.53–1.08) | NA | 0.42 (0.29–0.6) | 1.36 (0.88–2.11) | NA |

| Moderate | 0.74 (0.63–0.87)a | NA | 0.6 (0.46–0.78)a | NA | 0.71 (0.48–1.05) | NA | 0.71 (0.49–1.03) | 1.16 (0.74–1.82) | NA |

| Severe | 0.55 (0.47–0.65)a | NA | 0.5 (0.39–0.65)a | NA | 1 (0.47–2.14) | NA | 0.58 (0.25–1.35) | 1.8 (0.82–3.96) | NA |

| Annual family income (>$100,000 is reference) | |||||||||

| <$20,000 | 1.92 (0.84–4.4) | 1.57 (1.34–1.85)a | NA | NA | 0.87 (0.43–1.77) | NA | 0.52 (0.45–0.61)a | NA | NA |

| $20,000–49,999 | 1.83 (1.05–3.18) | 1.35 (1.15–1.59)a | NA | NA | 1.07 (0.69–1.64) | NA | 0.65 (0.56–0.76)a | NA | NA |

| $50,000–99,999 | 1.06 (0.75–1.51) | 1.16 (0.99–1.37)a | NA | NA | 0.65 (0.48–0.88) | NA | 0.81 (0.69–0.94)a | NA | NA |

| How many pregnancies have you had? | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.87 (0.81–0.95) | 0.94 (0.85–1.03) | 1.01 (0.99–1.29) | NA | 1.11 (1.01–1.22) |

Values in bold are significant at the p ≤ 0.05 level. Values in italics are significant at the p ≤ 0.10 level.

Variable was fit as a linear variable.

NA, variable was not included in fitted model.

Table 4.

Results (ORs) of the Fitted Multivariate Models for Sexually Active Women During the Menopausal Transition, Showing Variables Included 2 to 3 Final Models

| Enjoy | Passion | Pain | Dry | Fantasy | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of alcoholic drinks/year (estimate) | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 1.01 (1–1.01) | NA | NA | NA | 1 (0.99–1.01) |

| Hot flashes in the last 30 days (don't know/no is reference) | ||||||

| No | NA | 0.97 (0.73–1.28) | Base | NA | NA | NA |

| Yes | NA | 0.84 (0.59–1.2) | 1.22 (0.89–1.68) | NA | NA | NA |

| Vaginal discharge (1–4/week is reference) | ||||||

| Never | NA | NA | 0.84 (0.73–0.98)a | 1.54 (0.86–2.73) | NA | NA |

| <1/month | NA | NA | 0.92 (0.79–1.06)a | 2.06 (1.18–3.59) | NA | NA |

| 1–4/month | NA | NA | 1.09 (0.94–1.26)a | 1.93 (1.07–3.49) | NA | NA |

| >5/week | NA | NA | 1.19 (1.02–1.38)a | 1.25 (0.56–2.78) | NA | NA |

| Step on Ladder of Life at present | NA | NA | 0.94 (0.85–1.05) | NA | NA | 1.17 (1.02–1.33) |

| Depressed (0 = never to 4 = more than 5 times/week) | NA | NA | 1.14 (0.95–1.37) | NA | NA | 1.02 (0.86–1.22) |

| Did you ever use HRT? | NA | NA | NA | 1.56 (0.64–3.78) | NA | 1.53 (0.59–3.95) |

| How active are you in your leisure time (−2 = much less to 2 = much more) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.07 (0.92–1.23) | 1 (0.83–1.2) |

Values in bold are significant at the p ≤ 0.05 level. Values in italics are significant at the p ≤ 0.10 level.

Variable was fit as a linear variable.

Table 5.

Results (ORs) of the Fitted Multivariate Models for Sexually Active Women During the Menopausal Transition, Showing Variables Included Only 1 Final Model

| Arousal | Orgasm | Pain | Fantasy | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot flash frequency (0 = never to 3 = daily) | 0.92 (0.8–1.06) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Do you drink at least 12 alcoholic beverages a year? | 1.44 (1.04–1.99) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Number of alcoholic drinks at an average sitting | NA | 1.31 (1.07–1.61) | NA | NA | NA |

| How many packs do you smoke a year? | NA | 0.98 (0.95–1.01) | NA | NA | NA |

| Marital status (divorced is reference) | |||||

| Married or living with partner | NA | NA | 1.18 (0.7–1.98) | NA | NA |

| Single | NA | NA | 0.85 (0.43–1.67) | NA | NA |

| Widowed | NA | NA | 0.25 (0.03–1.92) | NA | NA |

| Irritable (0 = never to 4 = more than 5 times/week) | NA | NA | 1.08 (0.88–1.32) | NA | NA |

| Incontinent (base is 1–4/week) | |||||

| Never | NA | NA | 1.19 (0.64–2.21) | NA | NA |

| <1/month | NA | NA | 1.28 (0.68–2.42) | NA | NA |

| 1–4/month | NA | NA | 1.27 (0.65–2.48) | NA | NA |

| >5/week | NA | NA | 1.36 (0.53–3.48) | NA | NA |

| Number of days consuming alcohol/year | NA | NA | NA | 1 (0.98–1.02) | NA |

| Log (progesterone) | NA | NA | NA | 1.02 (0.92–1.13) | NA |

| Do you play a sport? | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.24 (0.82–1.88) |

| Health (0 = poor to 4 = excellent) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.29 (1.01–1.64) |

| Did you graduate college? | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.85 (0.59–1.2) |

Values in bold are significant at the p ≤ 0.05 level.

Although hot flash-related variables were included in several final models, their effect was rarely significant; women who never have hot flashes enjoyed sex more often than women with daily hot flashes and had dry sex less frequently than women with mild hot flashes. Increasing numbers of pregnancies decreased the frequency of satisfaction, but increased the overall frequency of sexual activity. Higher alcohol use was associated with more frequent enjoyment and arousal and more frequent orgasms. Women reporting rare or infrequent vaginal discharge also reported more frequent dry sex compared to women reporting weekly vaginal discharge. Women with self-perceived higher quality of life (a higher step on the Ladder of Life) and better health reported more frequent sexual activity.

Discussion

This study identified a number of factors associated with sexual function during the menopausal transition. Some factors were common across most or all possible sexual outcomes (physicality of work, oral contraceptive use, menopause status, and hot flashes), and may be areas worth researching for possible interventions in sexual dysfunction.

Women who perceived their work to be much heavier physically than others their age reported significantly more frequent enjoyment of sex, passion, and satisfaction with their partner, and had a significantly higher sexual function score. Very physical work could result in women being more physically fit, which could increase the ability of women to participate in and enjoy sexual activity. However, women whose work was physically lighter or much lighter than average also reported significantly more frequent enjoyment of sex and borderline significant more frequent satisfaction with their partner. This relationship should be considered in greater detail in future studies of sexual function to clarify the mechanism underlying the association.

Increased duration of oral contraceptive use was associated with more frequent arousal and enjoyment of sex and less frequent painful and dry sex, although overall sexual function score was only significantly associated with short-term oral contraceptive use. These are outcomes with which estradiol was associated in the univariate analysis, as well, which may suggest a mechanism to be explored with more advanced models in further studies; hormonal changes caused by oral contraceptive use could alter response to sexual cues, resulting in decreased arousal and lubrication and increased pain, although this effect has not been uniformly observed.41 Estrogens are known to reduce vaginal dryness,4 which would also reduce pain during sex. Postmenopausal women had significantly more frequent painful sex and had borderline significantly less frequent arousal, which would support that supposition.

As total annual family income increased, sexual function score decreased, as did the frequency of enjoyment of sex and the frequency of arousal during sex; increasing total family income also increased the frequency of dry sex. The mechanism for this effect is not immediately discernable, as the opposite effect has been noted previously.13 Changes in family income have also been associated with sexual dysfunction,3 so the effect may be related to stress over income shifts.

Hot flashes are one of the most common menopausal symptoms, but this study found little association between hot flashes and sexual activity when controlling for other variables. The exception is that women reporting no hot flashes enjoyed sex significantly more frequently and had dry sex significantly less frequently than women reporting any frequency or severity of hot flashes, respectively. Previous studies have found that women experiencing hot flashes were less likely to have weekly sexual activity than women not experiencing hot flashes.42 Vaginal dryness, another common menopausal symptom, was associated with a decreased sexual function score. It has been suggested that the causality may lie in the opposite direction, with increased sexual activity protecting against vaginal atrophy.43

An increased number of pregnancies were associated with a decreased frequency of satisfaction with one's partner and an increased frequency of sexual activity. Both were previously found to be nonsignificant, but that was in a cross-sectional study and so lacked the power of this analysis.44 The former may require a sociological study to determine a mechanism behind the relationship. The latter may be related to the protective effects of pregnancy against vaginal atrophy.43 No other sexual functions were associated with parity, which agrees with previously reported findings.45

Marriage was associated with a significantly decreased sexual function score. The mechanism for this is uncertain, but in the univariate marital status is strongly associated with fantasy, enjoyment, arousal, orgasm, frequency, and dryness, and is weakly associated with pain; this has been observed previously with respect to desire and arousal.1 It could be that the effect of marital status in any individual outcome is not strong enough to be retained in the final model, but the effect on the many outcomes making up the sexual function score is sufficient. The biological mechanism for this effect is unknown, but may be related to expectations for women living with their sexual partner to engage in sexual activity more frequently than they would prefer.

Other variables are associated with a broad range of sexual function outcomes, and many of these are associated with mental states: step on the Ladder of Life, depression, fatigue, and irritability, as well as self-reported health status. In the final models, higher steps on the Ladder of Life were associated with a higher sexual function score and a higher frequency of sexual activity, and better health status was associated with a higher frequency of sexual activity. In contrast, higher frequency of irritability was associated with a lower sexual function score. It is understandable that women who are frequently tired, depressed, or irritable are less likely to enjoy sexual activity, and mental health score has been previously linked to sexual satisfaction14,19,46 and to other factors associated with sexuality,8,16,47 with depression highly associated with sexual dysfunction48 and anxiety49 and depression8,50 associated with ability to achieve orgasm. Previous studies have also found an association between poor health and sexual function.1,8 However, this study found that few of these variables were significant in the final multivariate models, meaning that their effect is mostly accounted for by other variables.

Few behavioral variables were associated with sexual outcomes in the final models, and none was significant in the final model of sexual function score. The primary exception was alcohol use; increased alcohol use was associated with significant increases in the frequency of enjoying sex, being aroused, or experiencing orgasm, and was borderline associated with an increase in frequency of passion. Our previous work24 also found that an increase in drinking alcohol was associated with an increased likelihood of being sexually active. Previous studies have found an association between alcohol use and testosterone,51 which could control libido, or with passion for a sexual partner,15 but those correlations were not significant in these data. The overall size of the relationship is rather small, so the potential for intervention may be limited based on these data.

Many variables in the study had no significant relationship with most outcomes; these include race, education level, leisure activity, past use of herbal menopause therapies, testosterone levels, and amount of smoking. Androgens in particular have been proposed to play a role in sexual function during aging, although both a trial of hormone replacement17 and a cross-sectional study18 found, as we did, that androgens did not increase sexual activity. Education has previously been found related to sexual function with equivocal results,3,13,15,19,20 but in this study it was related only to frequency of sex in the univariate models, and was not significant in the final model.

This study could be limited by the self-reporting of symptoms and risk factor exposure, both of which may be affected by recall bias or reporter bias. In addition, the sample of women included in the study included few Hispanic or Asian individuals, which could limit the validity of the results for those groups.

This study found that sexual function in the menopausal transition is a complex topic. We examined many possible outcomes and found that while some risk factors are common across multiple outcomes, each outcome has a unique set of risk factors. The conclusion we must draw is that no recommendations can be made to improve “sexual function” during the menopausal transition. Instead, each area of sexual function must be considered independently; a patient-centered approach is most likely to be effective in these circumstances.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG18400).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Shifren JL, Monz BU, Russo PA, Segreti A, Johannes CB. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: Prevalence and correlates. Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:970–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Portman DJ, Gass MLS, Kingsberg S, et al. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: New terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the international society for the study of women's sexual health and The North American menopause society. J Sex Med 2014;11:2865–2872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC, Page P. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: Prevalence and predictors. J Am Med Assoc 1999;281:537–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Novi JM, Book NM. Sexual dysfunction in perimenopause: A review. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2009;64:624–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nappi RE, Lachowsky M. Menopause and sexuality: Prevalence of symptoms and impact on quality of life. Maturitas 2009;63:138–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goberna J, Francés L, Paulí A, Barluenga A, Gascón E. Sexual experiences during the climacteric years: What do women think about it? Maturitas 2009;62:47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nusbaum MRH, Helton MR, Ray N. The changing nature of women's sexual health concerns through the midlife years. Maturitas 2004;49:283–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laumann EO, Nicolosi A, Glasser DB, et al. Sexual problems among women and men aged 40–80 years: Prevalence and correlates identified in the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. Int J Impot Res 2005;17:39–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kingsberg SA, Woodard T. Female sexual dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:477–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeLamater J, Koepsel E. Relationships and sexual expression in later life: A biopsychosocial perspective. Sex Relatsh Ther 2015;30:37–59 [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeLamater J. Sexual expression in later life: A review and synthesis. J Sex Res 2012;49:125–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dennerstein L, Lehert P, Burger H. The relative effects of hormones and relationship factors on sexual function of women through the natural menopausal transition. Fertil Steril 2005;84:174–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verit FF, Verit A, Billurcu N. Low sexual function and its associated risk factors in pre- and post-menopausal women without clinically significant depression. Maturitas 2009;64:38–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nappi RE, Nijland EA. Women's perception of sexuality around the menopause: Outcomes of a European telephone survey. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2008;137:10–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomic D, Gallicchio LM, Whiteman MK, Lewis LM, Langenberg P, Flaws JA. Factors associated with determinants of sexual functioning in midlife women. Maturitas 2006;53:144–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yangin HB, Sözer GA, Şengün N, Kukulu K. The relationship between depression and sexual function in menopause period. Maturitas 2008;61:233–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myers LS, Dixen J, Morrissette D, Carmichael M, Davidson JM. Effects of estrogen, androgen, and progestin on sexual psychophysiology and behavior in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1990;70:1124–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis SR, Davison SL, Donath S, Bell RJ. Circulating androgen levels and self-reported sexual function in women. J Am Med Assoc 2005;294:91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Addis IB, Van den Eeden SK, Wassel-Fyr CL, et al. Sexual activity and function in middle-aged and older women. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:755–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elnashar AM, El-Dien Ibrahim M, El-Desoky MM, Ali OM, El-Sayd Mohamed Hassan M. Female sexual dysfunction in Lower Egypt. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol 2007;114:201–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Latif EZ, Diamond MP. Arriving at the diagnosis of female sexual dysfunction. Fertil Steril 2013;100:898–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dennerstein L, Dudley E, Burger H. Are changes in sexual functioning during midlife due to aging or menopause? Fertil Steril 2001;76:456–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dennerstein L, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, Guthrie JR, Burger HG. A prospective population-based study of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol 2000;96:351–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith RL, Gallicchio LM, Flaws JA. Factors affecting sexual activity in mid-life women: Results from the midlife health study. J Womens Health 2016;26:103–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gallicchio LM, Miller SR, Kiefer J, Greene T, Zacur HA, Flaws JA. Change in body mass index, weight, and hot flashes: A longitudinal analysis from the midlife women's health study. J Womens Health 2014;23:231–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith RL, Flaws JA, Gallicchio LM. Does quitting smoking decrease the risk of midlife hot flashes? A longitudinal analysis. Maturitas 2015;82:123–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith RL, Gallicchio LM, Miller SR, Zacur HA, Flaws JA. Risk factors for extended duration and timing of peak severity of hot flashes. PLoS One 2016;11:e0155079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ziv-Gal A, Gallicchio L, Chiang C, et al. Phthalate metabolite levels and menopausal hot flashes in midlife women. Reprod Toxicol 2016;60:76–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller HG, Li RM. Measuring hot flashes: Summary of a National Institutes of Health Workshop. Mayo Clin Proc 2004;79:777–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maki PM, Freeman EW, Greendale GA, et al. Summary of the National Institute on Aging-sponsored conference on depressive symptoms and cognitive complaints in the menopausal transition. Menopause 2010;17:815–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cochran CJ, Gallicchio LM, Miller SR, Zacur H, Flaws JA. Cigarette smoking, androgen levels, and hot flushes in midlife women. Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:1037–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gallicchio LM, Schilling C, Romani WA, Miller SR, Zacur H, Flaws JA. Endogenous hormones, participant characteristics, and symptoms among midlife women. Maturitas 2008;59:114–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gallicchio LM, Visvanathan K, Miller SR, et al. Body mass, estrogen levels, and hot flashes in midlife women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;193:1353–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Visvanathan K, Gallicchio LM, Schilling C, et al. Cytochrome gene polymorphisms, serum estrogens, and hot flushes in midlife women. Obstet Gynecol 2005;106:1372–1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dennerstein L, Lehert P, Dudley E. Short scale to measure female sexuality: Adapted from McCoy Female Sexuality Questionnaire. J Sex Marital Ther 2001;27:339–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dennerstein L, Anderson-Hunt M, Dudley E. Evaluation of a short scale to assess female sexual functioning. J Sex Marital Ther 2002;28:389–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kilpatrick FP, Cantril H. Self-anchoring scaling: A measure of individuals' unique reality worlds. J Individ Psychol 1960;16:158–173 [Google Scholar]

- 38.R Foundation for Statistical Computing. The R Development Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2014. Available at: www.r-project.org Accessed March6, 2014

- 39.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, et al. Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. J Stat Softw, 2014. Available at: http://lme4.r-forge.r-project.org Accessed April16, 2016

- 40.Touloumis A. GEE Solver for Correlated Nominal or Ordinal Multinomial Responses. 2014. Available at: cran.r-project.org/web/packages/multgee/multgee.pdf Accessed February3, 2016

- 41.Pastor Z, Holla K, Chmel R. The influence of combined oral contraceptives on female sexual desire: A systematic review. Contraception 2013;18:27–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCoy N, Culter W, Davidson JM. Relationships among sexual behavior, hot flashes, and hormone levels in perimenopausal women. Arch Sex Behav 1985;14:385–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Castelo-Branco C, Cancelo MJ, Villero J, Nohales F, Juliá MD. Management of post-menopausal vaginal atrophy and atrophic vaginitis. Maturitas 2005;52(Suppl 1):46–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hawton K, Gath D, Day A. Sexual function in a community sample of middle-aged women with partners: Effects of age, marital, socioeconomic, psychiatric, gynecological, and menopausal factors. Arch Sex Behav 1994;23:375–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fehniger JE, Brown JS, Creasman JM, et al. Childbirth and female sexual function later in life. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:988–997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gallicchio LM, Schilling C, Tomic D, Miller SR, Zacur H, Flaws JA. Correlates of sexual functioning among mid-life women. Climacteric 2007;10:132–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amore M, Di Donato P, Berti A, et al. Sexual and psychological symptoms in the climacteric years. Maturitas 2007;56:303–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Atlantis E, Sullivan T. Bidirectional association between depression and sexual dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med 2012;9:1497–1507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lucena B, Abdo CHN. Personal factors that contribute to or impairs women's ability to achieve orgasm. Int J Impot Res 2014;26:177–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fabre LF, Smith LC. The effect of major depression on sexual function in women. J Sex Med 2012;9:231–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cigolini M, Targher G, Bergamo Andreis IA, et al. Moderate alcohol consumption and its relation to visceral fat and plasma androgens in healthy women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1996;20:206–212 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]