Abstract

Prior studies concerning patterns of intermarriage among immigrants have primarily focused on how factors such as race/ethnicity, educational attainment, and country of origin shape the choice of a spouse. Moreover, they have focused on intermarriage patterns among immigrants who are already in the US. Using the 2010–2014 American Community Survey (ACS), we focus on immigrants who were not US citizens at the time of their marriage and highlight patterns of status exchange, specifically, the exchange of youth for citizenship. Towards this end, we compare the age gap between spouses across four different groups of respondents: 1) non-citizens married to a citizen before or upon arrival to the US; 2) non-citizens married to a citizen after arrival to the US; 3) non-citizens married to a non-citizen before or upon arrival to the US; and 4) non-citizens married to a non-citizen after arrival in the US. We document the fact that a large fraction of marriages between citizens and non-citizens occurred before or upon arrival to the US. We also provide evidence that immigrants who migrate to the US after marrying a US citizen, particularly women, tend to be partnered with much older spouses, signaling an exchange of youth for citizenship.

The proportion of marriages that includes partners of different nationalities has increased dramatically in recent decades and may be a sign of increasing globalization. This growth in marriages between partners of different nationalities—frequently referred to as cross-border marriages—has generated public interest in this practice. These cross-border marriages are often characterized by a pattern in which men from wealthier countries, after a relatively brief courtship, marry women from less developed countries. Increasingly, these marriages occur with the assistance of international marriage brokers or through social media networks (Lu and Yang 2010). Much of what we know about cross-border marriages is based on studies conducted in Asia or Europe. In Asia, increases in marriages between natives and immigrants have been sparked by local marriage squeezes, while in Europe increases have been attributed to shortages in labor that attract individuals from other countries. Popular and ethnographic accounts, as well as population-based studies conducted in Asia and Europe, suggest these marriages are often characterized by an unusually large age gap between partners, with the native-born husband being much older than the immigrant wife (e.g. Elbert 2016; Ma, Lin, and Zhang 2010; Nguyen and Tran 2010).

We know very little about the prevalence and characteristics of cross-border marriages in the US. While an extensive body of sociological and economic research has considered the mechanism of status exchange to theoretically account for intermarriage between US natives and immigrants, studies in the US have not considered age and citizenship status as elements of exchange. Instead, researchers have focused on racial/ethnic and educational assortative marriage patterns (e.g. Jasso, Massey, Rosenzweig and Smith 2000; Choi, Tienda, Cobb-Clark and Sinning 2012; Kalmijn 2012). Yet, qualitative studies and journalistic accounts suggest that a substantial number of American citizen men have gone abroad to areas such as Russia, Southeast Asia and East Asia in search of a bride. Many of the narratives involve older men who are seeking younger women; the se men offer entry to the US and the promise of an economically secure future. In exchange, the women offer youth and the hope of domesticity with traditional gender roles and companionship (e.g. Schaeffer 2013; Bernstein 2010; Constable 2003). However, these accounts are inadequate in addressing the relative prevalence of these relationships, and whether they are fundamentally different from marriages that occur between two immigrants in the US.

This omission reflects the fact that few studies of cross-border marriages in the US have examined the timing of marriage and migration (for an exception see Stevens et al. 2012). Indeed, the extant quantitative research on marriage patterns of immigrants in the US necessarily makes two assumptions: first, marriages occur well before immigrants arrive in the US or they occur sometime after arrival to the US. Marriages in the former category occur largely outside the purview of research on intermarriage. Marriages in the latter category are often viewed as an indicator of the assimilation status of different racial and ethnic groups (see Lighter, Ian and Tumid 2015 for example). However, a nontrivial number of marriages that involve immigrants occur at roughly the same time as migration. Recent estimates find that 19 percent of immigrant wives and 8 percent of immigrant husbands entered the country the same year they married. In addition, over a quarter of the husbands and roughly 30 percent of the wives who migrated and married in the same year had a native-born spouse (Stevens et al. 2012). For a growing number of immigrants, marriage and the ability to migrate to the US are integrally entwined.

The exclusion of such a large proportion of immigrant marriages is a significant oversight because marriage to a native-born American has long been viewed as the ‘final step’ in the assimilation process for immigrants and their offspring (Gordon 1964; Qian and Lichter 2007). Specifically, studies routinely assume that cross-border marriages occur after cultural (i.e. language and social practices) and structural (i.e. socioeconomic) integration which increases with time spent in the United States. Most prior research on intermarriage between immigrant and native populations in the US routinely focuses on immigrants who married after migrating, thus excluding marriages that were formed prior to migration. Immigrants who form a relationship with a US citizen before migration defy the notion that intermarriage is the final step in the process of becoming an American. It may be that migration on behalf of marriage to a US citizen (i.e. during the same year of arrival or even before entering the US) serves as the necessary first step in the trajectory from newcomer status to an integrated American for some migrants, but serves as the final step for other migrants.

Data from several recent years of the American Community Survey (hereafter ACS) offer us an unprecedented opportunity to study the intersection of marriage, migration, and citizenship among cross-border marriages in the United States. We add to the existing literature by utilizing information on year of migration and year of marriage to identify immigrants whose timing of migration is closely linked to their timing of marriage (i.e. those who marry in their home country or marry the same year they enter the US). We compare these marriage migrants to immigrants who marry their spouse after residing in the US over a year. We also extend the literature on immigrant marriage patterns in the US by considering the citizenship status of their spouse rather than simply their nativity. Emerging research suggests that “the citizenship status of the marriage partner is crucial” toward understanding the experiences of immigrants and that “marriages involving one or more non-citizens are qualitatively different from marriages joining partners who share a secure status in their country of residence” (Williams 2010: 24). This is a clarifying distinction because citizenship, regardless of nativity status, offers many advantages related to economic opportunity and civil liberties (Appear 2015).

We consider the intersection of timing and spousal citizenship status to contrast four groups of immigrants. These four groups form a continuum of marital integration, with immigrants marrying a US citizen either in their home country or upon arrival, thus occupying a fast track toward becoming a permanent resident or American citizen. We provide a descriptive profile of these four groups of immigrant men and women, examining how they differ in terms individual characteristics and partner homogeny. We also feature how immigrant men and women from different regions of the world are distributed across these four groups. Finally, we provide evidence that immigrants trade valued characteristics (e.g. youth) for an expedited path toward becoming a legal permanent resident or a US citizen.

BACKGROUND

Paths to Cross-Border Marriage

Increasing levels of globalization, greater international travel for work, tourism, and study, and the rising use of technology and social media have enhanced the opportunities for relationships to form between American citizens and immigrants from a wide range of countries (Stevens et al 2012). For example, cross-border marriages may result from increased contact as more immigrants travel to the US, or more American citizen’s travel to other countries in pursuit of educational or work opportunities. In addition, the formation of cross-border relationships is also enhanced by America’s military presence around the world (e.g., Korea, Vietnam, Germany). Large numbers of immigrants, predominately women, have long traveled to the US as brides or fiancées of American service members (Jasso and Rosenzweig 1990). While marriage migration streams from some countries are historically rooted in the military connection with the US, they persist after the military connection between the two counties is diminished (Hidalgo and Banks ton 2011).

A growing number of marriages are facilitated by agencies that offer specific information on (predominately) women residing in countries such as Russia, Colombia and the Philippines (Schaeffer 2013). Individuals can access these international marriage brokers (Iambs) via the Internet, newspaper advertisements, traditional mail correspondence, or organized “matchmaking” tours (Constable 2005; Lu 2008). These brokers are not necessarily arranging marriages but provide a venue for individuals to locate their own match across borders. Prior research suggests that US natives (predominately men) who seek international marriage partners through brokers seek partners that (they believe) hold more traditional views of marriage and family than American women in their local marriage market (e.g., Johnson 2007; Levenchenko and Isocheim 2013; Schaeffer 2013; Constable 2005). Somewhat ironically, many of the women seeking a partnership with a man from a Western country like the US may have expectations of a more modern and egalitarian marriage (Constable 2005).

Immigrants who have already settled in the US can similarly “import” a partner from their home country through marriage brokers, but they also have the option of recruiting partners through ties to kin in their home country. In many non-Western societies, individuals have traditionally relied on parents or extended family to arrange their marriage (e.g., Ballard 2001; Shaw 2001). In countries with a history of arranged marriages (e.g., India or Pakistan), having a grown child who holds citizenship status or legal permanent residency in a Western country such as Canada or the US is seen as a strong bargaining tool for families that are hoping to enhance their social standing (Backer 1994; Hooghiemstra 2001). For instance, Kalpagam (2008) finds that in India when a man who has emigrated to the US and holds legal permanent residence or citizenship he is considered a highly prestigious and a top-ranked choice for families that are arranging a marriage for their daughter. Migrants themselves also benefit from these arranged marriages, as they are able fulfill obligations to kin while also strengthening ties to their home country.

Under US law, an American citizen has the right to reside with their chosen spouse in the United States, regardless of when or how they meet (Jasso, Massey, Rosenzweig and Smith 2000). If an American citizen marries a foreign national outside of the US or marries a foreign national already legally residing in the US, under the family provisions of US immigration law the new spouse may be issued a permit allowing them to live and work permanently in the US. If an American citizen wishes to bring in a foreign national living abroad to marry, a K-1 or fiancé(e) visa is issued with the condition that the couple marries within 90 days (US Dept. of Homeland Security, 2017). Fiancé(e) visas are only available to American citizens; legal permanent residents to the US can only seek visas for spouses (Jackson 2006). Further, immigrants with spouses who hold American citizenship are eligible to apply for citizenship after just 3 years of residence rather than 5 years as is the case for other immigrants holding legal permanent residency. For immigrants, marriage to an American citizen represents an expedited route to permanent US residency and citizenship (Lichter et al 2015).

Prior Research on Cross-Border Marriages in the US

Prior studies on marriages between immigrant and US natives classify the spouses of immigrants in a variety of ways. To offer some recent examples, several studies merely distinguish spouses by whether they are native-born versus foreign-born (e.g. Choi et al. 2012; Stevens et al. 2012; Levenshenko et al. 2013). Kalmijn (2012) captures whether immigrants are paired with white native-born partners versus a same national origin partner. Lichter et al. (2015) use US Census data to contrast Hispanic and Asian immigrants by whether they are married to a foreign-born co-pan ethnic, native-born co-ethnic, White, or other minority partner. Bohra-Mishra and Massey (2015) define intermarriage in a similar fashion using a select sample of recent immigrants to the US. The vast majority of previous studies does not capture possible differences based on spousal citizenship and routinely exclude immigrants who married prior to or around the time of migration to ensure that the marriages occurred in the host country where the immigrant was exposed to US marriage market conditions.

Prior studies of cross-border marriages that are formed in the US find a strong positive association between educational attainment and intermarriage. This association is driven primarily by the tendency for married partners to match each other in their levels of education. Positive assortative mating along the lines of education presumably reflects both opportunities for contact provided by schools and workplaces, as well as preferences for a partner who is similar regarding socioeconomic status and cultural tastes. Interestingly, education gradients are weaker for immigrant groups that have higher levels of education on average (Kalmijn 2012). More educated immigrants from these groups (e.g. Asians) presumably have more opportunities to meet other more educated individuals from their own group. This, of course, assumes they have a preference for in-group marriage.

Using data from both the US and Australia, Choi and colleagues (2012) found that both same-nativity and mixed-nativity marriages are more likely to include partners with equal levels of education than different levels; however, immigrant men (but not women) in mixed-nativity marriages are more apt than their counterparts in same-nativity marriages to marry down in terms of education. This finding suggests that men trade higher education for nativity (Choi et al. 2012). Understanding patterns of exchange for cross-border marriages is complicated by the fact that immigrants may have completed their education in their countries of origin. As immigrants may receive lower economic returns from education in their countries of origin (Betts and Lofstrom 2000), they may be less able to use their education as a resource in exchange for citizenship. Notwithstanding this limitation, the findings of Choi and colleagues (2012) hint that exchange is an important “secondary force” that facilitates mixed-nativity marriages (Rosenfeld 2005). Like studies concerning intermarriage more generally, studies on this topic fail to measure characteristics that women traditionally trade on marriage markets, such as youth (for an exception see Sassler and Joyner 2011). This is a major oversight because the stream of cross-border marriage migrants are predominately composed of women (e.g., Constable 2005; Stevens et al 2013).

Studies on specific sending regions to the US using population-based data are scant. An exception is Levchenko and Solheim (2013) who used ACS data to contrast East European (e.g. from Russia, the Ukraine, Poland, and Romania) women who moved to the US as “marriage migrants” (defined as entering the US and marrying a non-Hispanic white native in the same year) with US- born non-Hispanic white women married to non-Hispanic white men (p 30). Regarding couple-level characteristics, they found an overriding tendency for all groups of women to be similar to their partners with respect to education and marital history. At the same time, they found that the age gap between partners, with the male partner being older than the female partner, was four times greater for the East European marriage migrants than for the US born women. In fact, Russian and Ukrainian women were, on average, eleven years younger than their American husbands were. Such a pattern is also found in cross-border marriages in East Asia (Jones and Sheen 2008; Tsai 2011), Italy (Guyton Assoiling 2015) and Sweden (Gustafson and Branson 2015; Elbert 2016). These studies are critical as they highlight a resource that women exchange in cross-border marriages: youth.

Another line of research centered in European and Asian countries examines cross-border marriages anchored in the literature of gender, globalization and transnational families. Much of this research is qualitative and concerns marriage migrants in other nations, mainly focusing on the prosperity gap between developed and less-developed countries as a key driver of cross-border marriages. This gap, combined with the increased globalization of culture and media representations of the West, is thought to inspire migration among those living in less-developed countries (Epidural 1991). Beck-Gresham (2007) argues that ‘the very difference between the sending country and the receiving country leads to the marriage union: this difference is the secret matchmaker’ (p. 277). Other research considers how globalization results in the greater commodification of intimate relationships, including marriage. Hochschild (2003) likens the love provided by women from developing countries to the extraction of resources such as gold from these countries in the nineteenth century. Recently, scholars have begun to consider that women in cross-border marriages are often simplistically characterized in popular and academic discussions as passive victims of trafficking or active agents with interests in ensuring their economic security (Constable 2009; Kim 2010; Beck-Gerstein 2010). While contested, these dualistic characterizations suggest that exchange may play a prominent role in marriages occurring between US citizens and non-citizens. Typically ignored are the non-migrant spouses who are often the initiator of cross-border marriage contact (Williams 2010).

Research utilizing population-based data have only recently begun to consider how patterns of matching and exchange in cross-border marriage are complicated by citizenship status. One recent study which examines intermarriage in Italy provides some evidence of an exchange between youth and citizenship. Guetto and Azzolini (2015) find that among migrants, the acquisition of citizenship reduces the likelihood that immigrants have a native-born spouse versus a foreign-born spouse. This finding is consistent with the notion that immigrants who have already obtained citizenship have less of an incentive to marry a native-born spouse. Further, this study found that spousal age gaps are greatest in marriages that involve immigrant women who do not possess Italian citizenship and an Italian man with Italian citizenship (Guetto and Azzolini 2015). Using data from Sweden, Elwert (2016) finds evidence of status exchange on age in cross-border marriages. These studies also find that the prominence of status exchange in cross-border marriages differs according to the country of origin of the immigrant partner (Elwert 2016; Guetto et al. 2015). Taken together, the above studies on cross-border marriages suggest that age and citizenship may operate as key mechanisms of exchange among immigrant marriages.

DATA AND METHODS

We use microdata from the 2010–2014 American Community Survey (ACS) made available by the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) (Ruggles et al. 2015). Each year, the ACS selects a representative sample of roughly 3.5 million addresses in the United States and collects a variety of demographic and economic information. Our analysis is based 90,302 female immigrant respondents and 75,713 male immigrant respondents who are currently married (spouse present) to a different-sex spouse, were married in the last ten years and who entered the US as adults (i.e., ages 18 and older). We merge spouse characteristics to each immigrant respondent record. Beginning in 2008, the ACS began to include the year of last marriage, current marital status, and the number of times married. For foreign-born respondents, the survey also asked about the year of arrival in the United States and if a citizen, the year of naturalization. These data allow us to determine which marriages occurred before the immigrant came to the United States, which marriages are closely tied to migration (i.e. occurring in the same year of migration), and which happened in the years after arriving in the United States. Also, these data allow us to determine the citizenship status of the spouse at the time of marriage. To better capture possible exchange, we limit our analysis to immigrant respondents who were not citizens at the time of marriage, acknowledging that immigrants with citizenship at marriage constitute a small fraction of recently married immigrants (i.e., 13% of female respondents and 19% of male respondents).

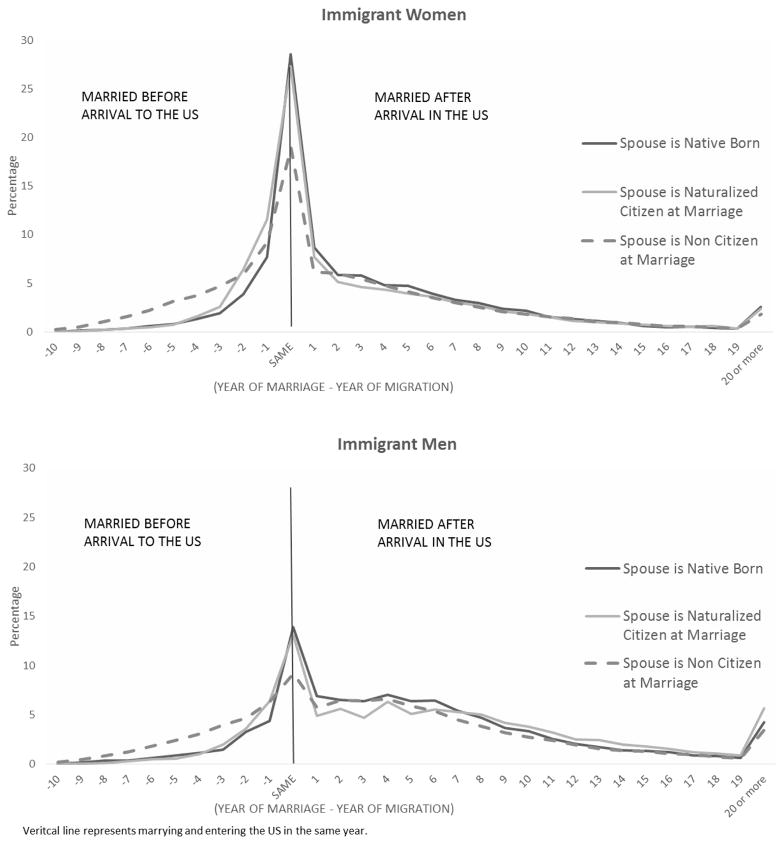

Figure 1 helps to illustrate the relationship between the timing of marriage and migration. Here, the percentage distribution is shown separately for immigrant respondents for three groups: 1) those who are married to native-born citizens, 2) those married to foreign-born immigrants who had become naturalized citizens prior to marriage, and 3) those who were married to foreign-born immigrants who were non-citizens at the time of marriage. The x-axis measures the difference between the year of marriage and the year of arrival in the US and the y-axis measures the percentage distribution of the three types of spouses. For each of these three types the percentages sum to 100 percent.

Figure 1.

The Percentage Distribution of the Timing of Marriage and Migration among Currently Married Non-Citizens by Spousal Citizenship Status.

The top panel of Figure 1 shows that roughly 29% of immigrant women married to a native-born citizen and 27% married to a naturalized citizen did so the same year that they migrated to the US. This is a sizable share of the total population of immigrant women who were non-citizens when they married. An additional 17% married to a US native did so before entering the country while roughly 24% of those married to a naturalized citizen married before arrival. The remaining 55% of immigrant women married to native-born citizens, and 49% married to a naturalized citizen did so at least a year or more after arrival. Among immigrant women in our sample married to non-citizen husbands, the patterns are less extreme, with roughly 19% marrying the same year they entered the US and 32% marrying before entering.

The bottom panel of Figure 1 indicates that the bulk of male migrants marry after residing in the US for at least a year. Almost three-quarters of immigrant men married to either a native or naturalized citizen married at least a year after arrival. Roughly 13% of immigrant men married to a native or married to a naturalized citizen did so the same year that they last entered the US. Among non-citizen men married to non-citizen women, nearly two-thirds marry at least a year after arrival, and just 9% marry the same year they enter. These patterns support the importance of classifying the spouse by citizenship rather than simply by nativity status as done in prior research that examines the relationship between migration and marriage.

Measures

Dependent variable

Our dependent variable is a continuous measure of the difference between spouses’ age—the spousal age gap. This is measured from the perspective of the husband for both male and female respondents and is created by subtracting the wife’s age from the husband’s age. If the gap is positive, the husband is older, and if the wife is older, the gap is negative.

Independent variables

Our key independent variable represents the intersection of the timing of migration, marriage, and spousal citizenship. First, we collapse the timing of marriage and migration into two groups, marrying and migrating before or upon arrival and marrying at least one year after arrival. We then create a categorical variable consisting of four mutually exclusive categories for our non-citizen respondents: 1) married a citizen before or upon arrival, 2) married a citizen after arrival, 3) married a non-citizen before or upon arrival, and 4) married anon-citizen after arrival.

Prior research on immigrant marriage in the US typically focuses on marriages that occur after the immigrant has arrived in the US. Our decision to collapse the timing of marriage and migration into two groups is conceptually driven by the idea that marriages (in particular, marriages between an immigrant and a US citizen) which occur outside the US or during the same year of migration represent a ‘fast track’ toward permanent residency or US citizenship compared to marriages that take place after the immigrant has arrived in the country.

We also classify the country of origin of our non-citizen respondents into 13 world regions: Latin America and the Caribbean, South America, Northern/Western Europe, Southern Europe, Central/Eastern Europe, Russia/Baltic States, East Asia, Southeast Asia, India and Southwest Asia, the Middle East/Asia Minor, Africa, Australia, and Canada. Details of the countries included in these categories are presented in Appendix 2 (female respondents) and Appendix 3 (male respondents).

Control variables

Our multivariate models control for several characteristics. We include immigrant respondent’s age at marriage as higher ages of marriage have been found to be associated with larger spousal age differences (England and McClintock 2009). We also include a measure of the immigrant respondent’s educational attainment expressed as number of years of schooling, along with an indicator of remarriage. We control for whether the immigrant respondent had a previous marriage because prior studies found less similarity in spousal ages with higher order marriages (Dean and Guar 1978; Wheeler and Gunter 1987). For illustrative purposes, we also present descriptive statistics for several characteristics of the spouse, including age at marriage, educational attainment, and remarriage..

Analysis

We present descriptive statistics by these four mutually exclusive marriage categories, separately for our male and female respondents. For the continuous variables, we conduct tests of statistical significance to assess differences in means across our four migration/marriage/spousal citizenship groups. Our multivariate analysis is a series of OLS regressions, stratified by gender of the respondent and region of the world adjusted with person-level ACS weights (Appendix 1). We present model-based predicted values of the age gap by gender and region.

RESULTS

Tables 1 and 2 show the sample characteristics and distribution by sex for our four categories of immigrant respondents: 1) married a citizen before or upon arrival, 2) married a citizen after arrival, 3) married a non-citizen before or upon arrival, and 4) married a non-citizen after arrival. Among our sample of immigrant women (Table 1), one in five (20.3%) marry a citizen either prior to or upon entering the US, 22.1% marry a citizen after they have been in the US at least a year, with the remaining marrying a non-citizen either prior to during the same year they arrive (29.5%), or marrying a fellow non-citizen after residing in the US at least a year (28.2%). Patterns of immigrant marriages differ starkly by gender. Just under 9 percent of immigrant men in our sample marry a US citizen close to the time they migrate, while 2.53% marry a citizen after residing in the US at least a year (Table 2). The largest share of immigrant male respondents marries a fellow non-citizen after living in the US at least a year (44.8%). These patterns support prior research that shows migration streams to be highly gendered (e.g., Stevens 2012; Donator, Alexander, Abaci and Linemen 2011) with a much larger fraction of immigrant women than immigrant men meeting and marrying someone with US citizenship before they arrive in the country.

TABLE 1.

Select Characteristics of Noncitizen Women by Timing of Marriage, Migration and Spousal Citizenship Status

| Marriage/Migration Timing Categories | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Spouse is a Citizen at Marriage | Spouse is a Non-Citizen at Marriage | ||||

|

| |||||

| Total Sample | Marry Before/On Arrival | Marry After Arrival | Marry Before/On Arrival | Marry After Arrival | |

|

|

|||||

| Distribution of marriages (sums across to 100%) | 100% | 20.3% | 22.1% | 29.5% | 28.2% |

| Dependent Variable | |||||

| Mean Spousal Age Difference (years, husbands age minus wife’s age) | 3.9 | 7.4 | 4.5 | 3.4 | 1.6 |

| Median Spousal Age Difference (years) | 3.0 | 6.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 |

| Respondent Characteristics | |||||

| Age at time of survey | 35.4 | 35.1 | 38.8 | 32.1 | 36.5 |

| Age married | 27.9 | 27.7 | 31.8 | 23.8 | 29.3 |

| Education (in years) | 13.2 | 13.8 | 13.7 | 14.0 | 11.6 |

| On second or higher marriage (%) | 16.1% | 16.3% | 30.0% | 5.9% | 16.2% a |

| US Veteran (%) | 0.11% | 0.11% | 0.21% | 0.06%a | 0.09%ab |

| Spouse Characteristics | |||||

| Age at survey | 39.4 | 42.6 | 43.3 | 35.4 | 38.1 |

| Age married | 33.9 | 37.2 | 38.4 | 29.2 | 32.9 |

| Education (in years) | 13.4 | 14.1 | 13.8 | 14.4 | 11.5 |

| On second or higher marriage (%) | 23.9% | 38.9% | 40.5% | 8.3% | 16.5% |

| US Veteran (%) | 5.2% | 13.3% | 10.2% | 0.4% | 0.6% |

| Difference Between Respondent and Spouse | |||||

| Education gap (husband years of education - wife’s years of education) | 0.16 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.32a | −0.10 |

| Different race/ethnicity than spouse (%) | 14.6% | 30.1% | 31.6% | 2.1% | 3.2% |

| Unweighted N | 90,302 | 20,037 | 21,299 | 25,382 | 23,584 |

Weighted estimates. IPUMS ACS 2010–2014. Citizenship status is determined at time of marriage.

Differences in means across marital and migration timing categories are all statistically significant to the p< .05 level unless indicated.

Estimate not significantly different from “Spouse Citizen, Married prior to/upon arrival in the US”

Estimate not significantly different from “Spouse Non-Citizen, Married prior to/upon arrival in the US”

TABLE 2.

Select Characteristics of Noncitizen Men by Timing of Marriage, Migration and Spousal Citizenship Status

| Marriage/Migration Timing Categories | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Spouse is a Citizen at Marriage | Spouse is a Non-Citizen at Marriage | ||||

|

| |||||

| Total Sample | Marry Before/On Arrival | Marry After Arrival | Marry Before/On Arrival | Marry After Arrival | |

|

|

|||||

| Distribution of marriages (sums across to 100%) | 100% | 8.6% | 23.5% | 23.1% | 44.8% |

| Dependent Variable | |||||

| Mean Spousal Age Difference (years, husbands age minus wife’s age) | 2.6 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 3.3 |

| Median Spousal Age Difference (years) | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

| Respondent Characteristics | |||||

| Age at time of survey | 37.2 | 36.2 | 38.6 | 35.2 | 37.7 |

| Age married | 29.7 | 28.9 | 31.8 | 26.7 | 30.4 |

| Education (in years) | 13.0 | 13.7 | 13.0 | 14.2 | 12.3 |

| On second or higher marriage | 15.7% | 14.9% | 26.6% | 6.7% | 14.7%a |

| US Veteran | 0.49% | 0.55% | 0.83% | 0.33% | 0.38%b |

| Spouse Characteristics | |||||

| Age at survey | 34.6 | 35.5 | 36.7 | 32.6 | 34.4 |

| Age married | 29.1 | 30.2 | 31.9 | 26.1 | 29.1 |

| Education (in years) | 13.2 | 14.4 | 13.8 | 13.9 | 12.3 |

| On second or higher marriage | 16.6% | 24.6% | 30.8% | 6.8% | 12.7% |

| US Veteran | 0.33% | 0.93% | 0.81%a | 0.07% | 0.09%b |

| Difference Between Respondent and Spouse | |||||

| Education gap (husband years of education-wife’s years of education) | −0.16 | −0.67 | −0.77 | 0.34 | −0.01 |

| Different race/ethnicity than spouse | 8.8% | 17.1% | 23.5% | 2.2% | 2.8% |

| Unweighted N | 75,713 | 7,273 | 19,135 | 17,162 | 32, 143 |

Weighted estimates. IPUMS ACS 2010–2014. Citizenship status is determined at time of marriage.

Differences in means across marital and migration timing categories are all statistically significant to the p< .05 level unless indicated.

Estimate not significantly different from “Spouse Citizen, Married prior to/upon arrival in the US”

Estimate not significantly different from “Spouse Non-Citizen, Married prior to/upon arrival in the US”

If men value youth, and immigrant women value US citizenship, then we would expect to find the largest differences in age between non-citizen women married to citizen men. In addition, if an immigrant woman has already borne the cost of migrating to the United States, then any marriage that takes place after arrival should ‘cost less’ in terms of youth. Evidence for this expectation is found in Table 1, which shows that spousal age differences among female respondents follow a distinct gradient. Specifically, among immigrant women who marry a US citizen either before or upon entering the US, husbands are, on average, 7.4 years older than these immigrant women. When she marries a citizen after residing in the US at least a year, the average age difference declines to 4.5 years. Further evidence is found among marriages of immigrant women to non-citizen men. The spousal age difference is smaller overall compared to marriages involving a non-citizen woman and a citizen man, but the cost of the relative timing of arrival is still apparent. When an immigrant woman marries a fellow non-citizen man either before or upon arrival in the US, she is 3.4 years younger than her spouse, on average. The age difference falls to 1.6 years when she marries a fellow non-citizen after she has already resided in the US.

If the exchange between youth and spousal citizenship or access to the US operates the same for male immigrants as it does for comparable female immigrants we would expect the smallest spousal age difference, that is the unions in which the husband is closest in age to his wife, among non-citizen men who married citizen women either before or upon migrating to the US. Evidence for this expectation is found at the top of Table 2, which presents parallel information for male respondents. The smallest spousal age difference (0.7 years) was found among non-citizen men who married a citizen woman either prior to or upon arrival to the US. This suggests that citizen women may be able to exchange their citizenship and access to the US, for a younger husband. Similar to the patterns presented for women, among non-citizen men who marry citizen women after residing in the US, the spousal age gap increases to 1.9 years. If the non-citizen man marries a fellow non-citizen woman prior to or upon arrival he is roughly 2.6 years older than his wife, whereas if he marries a non-citizen woman after arriving in the US, the gap increases to 3.3 years.

To place these values in context, we calculated the average difference in spousal ages for a similar sample of marriages between two native-born respondents of the ACS. We found that husbands are on average 2.1 years older than their wives. To account for any skewness in the distribution, Tables 1 and 2 also presents the median values of the spousal age gap by our four-category migration/marriage/spousal citizenship groups. We find similar patterns of a possible exchange between youth and spousal citizenship. Tables 1 and 2 also present select characteristics of immigrant women and men first for the entire sample, and then by our four-category typology. (Differences across the four groups are all statistically significant to at least the p<.05 level unless indicated). Among women respondents (Table 1), the youngest average age at marriage occurs among those who marry a non-citizen either in their home country or upon arrival in the US, (23.8 years) while the oldest age at marriage (31.8 years) is found among immigrant women who marry a US citizen after they have arrived in the US, possibly because this group is more likely to be in their second or higher marriage. Indeed, 30.0% of non-citizen women who married a citizen after arrival in the US were married at least once before, compared with just 5.9% of non-citizen women who married a non-citizen man prior to or upon arrival in the US. Migrant educational levels exhibit little variation by their spouse’s citizenship status and marital timing. Respondents who are non-citizen women have, on average, approximately 14 years of education with the exception of those who married a non-citizen spouse after arriving in the US. They are the least educated with just under a high school diploma (11.6 years).

Turning to the characteristics of the spouse, we see that the citizen husbands of immigrant women are more likely to be on their second or higher marriage (38.9% and 40.5%) compared to non-citizen husbands (8.3% and 16.5%). Additionally, 13.3% of women who marry a citizen prior to or upon entry and 10.2% who marry after arrival have married a US military veteran. The education gap between the non-citizen wife and their husband is also modest – about 0.3 years for those that marry a citizen or a non-citizen prior to or upon arrival, and 0.15 years for those that marry a citizen after arrival in the US. However, immigrant women who marry a fellow non-citizen spouse after one year or more in the US are, on average, better educated than their husbands. Finally, among non-citizen women, marriages to a citizen, regardless of timing of entry, are much more likely to be an interracial/ethnic marriage. For example, 30.1% of women who marry a citizen before or upon entry to the US and 31.6% of women who marry a citizen after arrival are a different race/ethnicity than their spouse. Interracial/ethnic marriages are much less likely when two non-citizens marry.

Among immigrant male respondents (Table 2), the youngest age at marriage occurs for those who marry a fellow non-citizen prior to or upon arrival in the US (26.7 years), while the oldest age at marriage occurs among non-citizen men married to citizen women after arrival in the US (31.8 years). Similar to women, non-citizen men married to citizen women are the group most likely to be on their second or higher marriage. Over a quarter (26.6%) of non-citizen men who married a citizen woman after residing in the US were on their second or higher marriage, while fewer than seven percent (6.7%) of non-citizen men married to non-citizen women prior to or upon entry were married more than once. Respondents who are non-citizen grooms who married a citizen bride either prior to or upon arrival are slightly more educated (13.7 years of education) compared to their counterparts who married a citizen after arrival, who have about 13.0 years of education. Non-citizen grooms that married a non-citizen bride close to their time of arrival have about 14.2 years of education compared to 12.3 years of education of the average non-citizen grooms that married a non-citizen bride after migration.

Interestingly, non-citizen husbands who married a citizen wife were less educated than their wives. Non-citizen men who married citizen women either prior to or upon arrival had 0.7 fewer years of education than their citizen wives, and non-citizen men who married their citizen wives later also had about 0.8 years less education than their wives. Non-citizen men who married non-citizen women around the time of arrival had about 0.34 years more education than their wives did. Finally, non-citizen men who married a non-citizen woman after more than a year in the US had education levels almost identical to their wives (gap = −0.01 years). Non-citizen men married to US citizens are much more likely to have a spouse of a different race/ethnicity than are non-citizen men married to fellow non-citizens. For example, 17.1% of non-citizen men married to citizen women prior to or upon arrival and 23.5% married to citizen women after arrival are a different race/ethnicity than their wife, compared to fewer than 3% of non-citizen men married to non-citizen women.

These patterns may be confounded by the distribution of immigrants from various regions into different migration/marriage/spousal citizenship categories (i.e., respondents from certain regions may be clustered in specific categories). We address this issue by presenting regional differences in our 4-category group membership in Table 3. We find very clear regional patterns of marriage, migration, and spousal citizenship. For example, non-citizen women from Southeast Asia (46.2%), Canada (33.8%) and Russia (31.2%) are the most likely among the thirteen world regions represented to be married to a US citizen prior to or upon arrival. In contrast, just 11.3% of women respondents from Latin America/Caribbean, and 12.4% from India are married to a US citizen prior to migrating or upon arrival. Among men, the top sending regions for migrants married to US citizens are quite different than those for women. For example, 27.9% of male respondents from Northern/Western Europe (i.e. France, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland), 27.7% of male respondents from Australia, and 20.2% of male respondents from Canada marry a US citizen woman either prior to or upon entering the country. Table 2 also reveals striking gender differences in these patterns. For example, almost a quarter (23.1%) of female respondents from East Asia (i.e. China, Korea) and almost a third of female respondents from Russia are married to a citizen prior to or upon arrival, yet just 4.3% of men from East Asia and 7.8% of men from Russia share the same status.

TABLE 3.

Region of Origin by Timing of Marriage, Migration and Spousal Citizenship Status, Percent Distribution

| Non-Citizen Female Respondents | Non-Citizen Male Respondents | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Spouse is a Citizen | Spouse is a Non- Citizen |

Spouse is a Citizen | Spouse is a Non- Citizen |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Marry Before/On Arrival |

Marry After Arrival |

Marry Before/On Arrival |

Marry After Arrival |

Marry Before/On Arrival |

Marry After Arrival |

Marry Before/On Arrival |

Marry After Arrival |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| World Region (sum across to 100%) | ||||||||

| Latin America/Caribbean | 11.3 | 18.8 | 23.3 | 46.6 | 6.1 | 23.7 | 14.9 | 55.2 |

| South America | 21.2 | 35.1 | 17.2 | 26.5 | 7.0 | 31.7 | 19.4 | 41.9 |

| Northern/Western Europe | 25.7 | 34.7 | 27.9 | 11.7 | 27.9 | 42.0 | 20.1 | 10.0 |

| Southern Europe | 25.8 | 30.6 | 27.7 | 15.9 | 17.5 | 33.1 | 27.0 | 22.4 |

| Central/Eastern Europe | 26.6 | 36.2 | 18.3 | 18.9 | 11.9 | 35.5 | 21.5 | 31.1 |

| Russia/Baltic States | 31.2 | 30.9 | 22.0 | 15.8 | 7.8 | 23.7 | 32.9 | 35.6 |

| East Asia | 23.1 | 25.4 | 30.5 | 21.0 | 4.3 | 14.1 | 37.3 | 44.3 |

| Southeast Asia | 46.2 | 28.1 | 12.8 | 12.9 | 12.5 | 23.0 | 26.8 | 37.7 |

| India/South West Asia | 12.4 | 5.6 | 65.6 | 16.3 | 5.7 | 8.7 | 35.7 | 49.9 |

| Middle East/Asia Minor | 26.5 | 13.2 | 49.2 | 11.1 | 14.9 | 25.6 | 35.6 | 23.9 |

| Africa | 22.5 | 21.5 | 33.5 | 22.5 | 12.7 | 31.3 | 26.1 | 29.8 |

| Australia | 28.8 | 28.5 | 23.6 | 19.2 | 27.7 | 32.8 | 22.5 | 16.9 |

| Canada | 33.8 | 40.1 | 18.5 | 7.6 | 20.2 | 47.9 | 18.5 | 13.5 |

| Unweighted N | 20,037 | 21,299 | 25,382 | 23,584 | 7,273 | 19,135 | 17,162 | 32, 143 |

Weighted estimates. IPUMS 2010–2014. Citizenship status is determined at time of marriage.

Regression Analyses

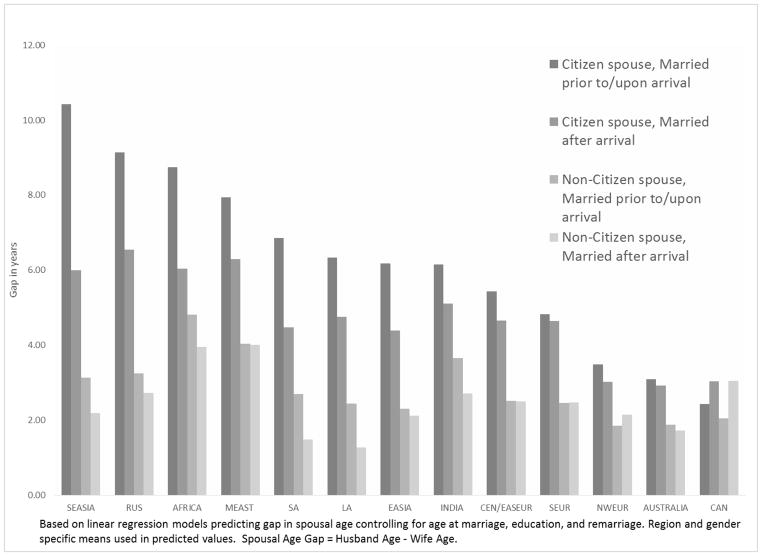

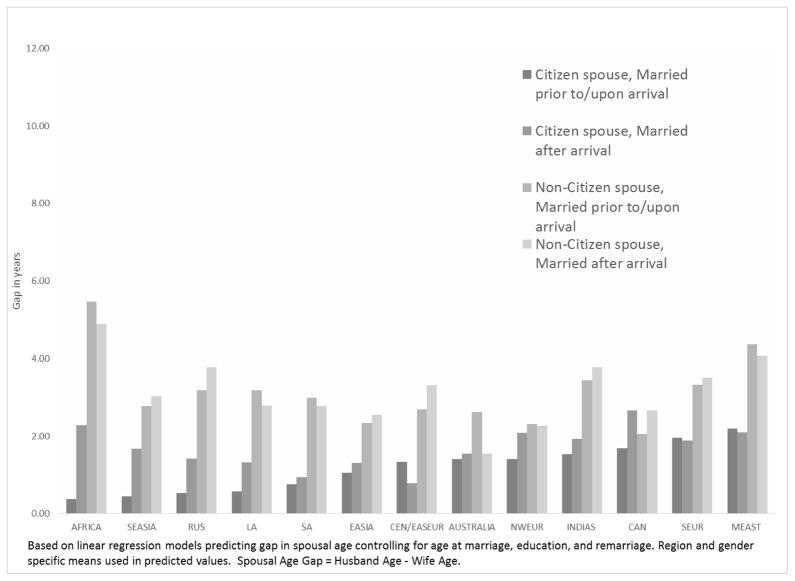

We next regress the gap in spousal ages on three indicators for our migration/marriage/spousal citizenship categories (with married to a citizen prior to or upon serving as the reference category) and following England et al. (2009) we control for the immigrant respondents age at marriage, number of times they were married, and the number of years of respondent education. We stratify the models by gender and region and show the coefficients in Appendix Table 1. For ease of interpretation, we present the predicted age gap adjusted for region and sex-specific mean levels of the control variables. The predicted age gap by category and region for men and women migrants is presented in Figures 2 and 3. (Appendix Tables 3 and 4 present the predicted age gap by region and country for male and female respondents).

Appendix Table 1.

Results from the region and gender stratified linear regression models of spousal age gap.

| MODEL COEFFICIENTS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Key Independent Variable: Marriage/Migration Categories a | Control variables | |||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| World Region of Origin | Intercept | Married citizen after arrival in US | Married non-citizen before/upon arrival | Married non-citizen after arrival | Age married (respondent) | Number of years of education (respondent) | Remarriage (respondent) | Unweighted Sample Size |

| A. Women Respondents | ||||||||

| Total Sample | 11.35 *** | −2.50 *** | −4.44 *** | −5.77 *** | −0.12 *** | −0.06 *** | 0.61 *** | 90,302 |

| Models stratified by region | ||||||||

| Latin America/Caribbean | 10.34 *** | −1.58 *** | −3.89 *** | −5.07 *** | −0.13 *** | −0.03 ** | 0.37 * | 29,374 |

| South America | 11.37 *** | −2.39 *** | −4.16 *** | −5.38 *** | −0.10 *** | −0.12 *** | 0.38 | 8,231 |

| Northern/Western Europe | 6.94 *** | −0.46 | −1.63 *** | −1.34 ** | −0.09 *** | −0.05 | 0.66 | 2,800 |

| Southern Europe | 9.98 *** | −0.18 | −2.36 *** | −2.35 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.10 | 0.37 | 972 |

| Central/Eastern Europe | 8.71 *** | −0.77 * | −2.92 *** | −2.93 *** | −0.10 *** | −0.04 | 0.65 + | 3,821 |

| Russia/Baltic States | 11.15 *** | −2.60 *** | −5.90 *** | −6.42 *** | −0.05 * | −0.06 | 1.18 ** | 3,080 |

| East Asia | 9.65 *** | −1.79 *** | −3.88 *** | −4.06 *** | −0.06 *** | −0.13 *** | 1.96 *** | 10,553 |

| Southeast Asia | 17.23 *** | −4.42 *** | −7.29 *** | −8.23 *** | −0.12 *** | −0.23 *** | −0.04 | 9,950 |

| India/South West Asia | 13.72 *** | −1.05 ** | −2.49 *** | −3.45 *** | −0.19 *** | −0.20 *** | 1.44 *** | 12,295 |

| Middle East/Asia Minor | 12.26 *** | −1.66 * | −3.91 *** | −3.94 *** | −0.11 *** | −0.12 ** | 1.30 + | 2,084 |

| Africa | 14.87 *** | −2.70 *** | −3.94 *** | −4.80 *** | −0.13 *** | −0.17 *** | −0.84 + | 4,250 |

| Australia | 6.21 *** | −0.17 | −1.22 + | −1.37 | −0.11 ** | −0.01 | 1.57 + | 573 |

| Canada | 4.97 *** | 0.60 | −0.39 | 0.61 | −0.04 * | −0.08 | 0.26 | 2,319 |

| B. Male Respondents | ||||||||

| Total Sample | −6.45 *** | 0.62 *** | 2.46 *** | 2.36 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.04 *** | −0.07 | 75,713 |

| Models stratified by region | ||||||||

| Latin America/Caribbean | −5.97 *** | 0.74 *** | 2.61 *** | 2.22 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.02 | 0.15 | 29,440 |

| South America | −7.74 *** | 0.19 | 2.23 *** | 2.02 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.07 ** | −0.25 | 5,309 |

| Northern/Western Europe | −8.32 *** | 0.68 * | 0.90 ** | 0.85 * | 0.24 *** | 0.10 ** | 0.72 * | 4,265 |

| Southern Europe | −4.77 *** | −0.08 | 1.37 * | 1.54 ** | 0.21 *** | −0.04 | 1.50 * | 1,142 |

| Central/Eastern Europe | −4.76 *** | −0.55 | 1.34 ** | 1.97 *** | 0.21 *** | −0.02 | −0.62 | 2,822 |

| Russia/Baltic States | −5.15 *** | 0.89 | 2.66 ** | 3.25 *** | 0.20 *** | −0.01 | 0.38 | 1,521 |

| East Asia | −5.00 *** | 0.25 | 1.29 *** | 1.49 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.00 | −0.24 | 6,102 |

| Southeast Asia | −6.45 *** | 1.23 ** | 2.32 *** | 2.58 *** | 0.25 *** | −0.06 + | −0.56 | 3,666 |

| India/South West Asia | −5.96 *** | 0.39 | 1.90 *** | 2.24 *** | 0.30 *** | −0.04 * | −0.28 | 12,044 |

| Middle East/Asia Minor | −6.50 *** | −0.10 | 2.17 *** | 1.88 *** | 0.32 *** | −0.01 | −0.14 | 2,165 |

| Africa | −11.36 *** | 1.91 *** | 5.09 *** | 4.52 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.04 | −0.38 | 4,574 |

| Australia | −5.49 *** | 0.14 | 1.22 * | 0.14 | 0.22 *** | −0.01 | 0.52 | 729 |

| Canada | −5.30 *** | 0.98 * | 0.36 | 0.97 | 0.18 *** | 0.04 | −0.60 | 1,934 |

Weighted regressions. IPUMS ACS 2010–2014. See text for model descriptions.

p<.001;

p<.01;

p<.05;

p<.10

Reference category is “Married to a citizen before/upon arrival”.

Figure 2.

Predicted Spousal Age Gap by Region of Origin and Marriage, Migration and Spousal Citizenship Groups, Non-citizen Women

Figure 3.

Predicted Spousal Age Gap by Region of Origin and Marriage, Migration and Spousal Citizenship Groups, Non-citizen Men

Appendix Table 3.

Predicted Spousal Age Gap by Timing of Marriage, Migration and Spousal Citizenship and Country of Origin: Noncitizen Female Respondents.

| Women Respondents | Unweighted Number of Cases | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Spouse is a Citizen at Marriage | Spouse is a Non-Citizen at Marriage | ||||

|

|

|

||||

| Marry Before/On Arrival | Marry After Arrival | Marry Before/On Arrival | Marry After Arrival | ||

|

| |||||

| CANADA | 2.43 | 3.03 | 2.04 | 3.04 *** | 2,319 |

| LATIN AMERICA/CARIBEAN | 6.33 *** | 4.75 *** | 2.45 *** | 1.27 *** | 29,374 |

| Mexico | 5.14 *** | 4.20 *** | 2.11 *** | 1.17 *** | 19,117 |

| Central America | 7.84 *** | 5.53 *** | 2.41 *** | 1.18 *** | 5,679 |

| Cuba | 8.27 *** | 6.89 *** | 2.59 | 2.85 *** | 1,005 |

| West Indies | 8.03 *** | 5.45 *** | 4.24 *** | 2.47 *** | 3,573 |

| SOUTH AMERICA | 6.86 *** | 4.47 *** | 2.70 *** | 1.48 *** | 8,231 |

| NORTHERN/WESTERN EUROPE | 3.48 ** | 3.02 * | 1.85 | 2.14 *** | 2,800 |

| Sweden | 4.81 + | 2.91 | 2.72 | 1.87 | 170 |

| UK | 3.25 ** | 2.72 * | 1.77 | 1.41 * | 1,578 |

| France | 3.56 | 4.41 | 1.89 + | 3.28 *** | 493 |

| Netherlands | 3.56 | 2.51 | 2.16 + | 5.82 * | 154 |

| Denmark/Norway/Finland/Iceland | 3.21 | 3.00 | 2.64 | 1.14 * | 182 |

| Switzerland/Belgium/Austria | 3.27 | 2.58 | 0.52 | 1.68 * | 223 |

| SOUTHERN EUROPE | 4.82 ** | 4.63 ** | 2.45 | 2.47 *** | 972 |

| Albania | 6.97 + | 6.57 | 4.82 | 4.11 *** | 179 |

| Greece | 6.25 * | 5.05 * | 3.25 | 1.79 | 133 |

| Italy | 2.88 | 4.00 | 1.63 | 3.44 | 296 |

| Spain | 4.94 ** | 3.89 * | 1.43 | 0.88 | 364 |

| CENTRAL/EASTERN EUROPE | 5.42 *** | 4.65 *** | 2.51 | 2.49 *** | 3,821 |

| Bulgaria | 3.94 | 6.26 ** | 2.03 | 2.71 | 278 |

| Czechoslovakia | 6.69 *** | 6.81 *** | 3.46 | 2.20 | 277 |

| Germany | 3.80 | 3.52 | 2.68 | 2.51 ** | 1,160 |

| Hungary | 9.25 * | 7.35 + | 2.56 | 3.64 | 157 |

| Poland | 6.32 *** | 4.66 *** | 1.87 | 2.53 *** | 1,056 |

| Romania | 7.90 *** | 4.78 * | 2.57 | 2.67 ** | 515 |

| Yugoslavia | 5.39 *** | 4.16 + | 3.50 | 2.48 *** | 378 |

| RUSSIA/BALTIC STATES | 9.14 *** | 6.54 *** | 3.24 | 2.72 *** | 3,080 |

| EAST ASIA | 6.18 *** | 4.38 *** | 2.30 | 2.12 *** | 10,553 |

| China | 8.59 *** | 5.46 *** | 2.61 * | 2.21 *** | 6,340 |

| Japan | 2.26 | 2.75 * | 1.17 | 1.52 + | 1,743 |

| Korea | 2.98 * | 3.29 ** | 1.93 | 1.91 *** | 2,148 |

| Other Asia | 8.28 *** | 6.01 | 3.91 | 3.88 + | 322 |

| SOUTH EAST ASIA | 10.42 *** | 6.00 *** | 3.13 ** | 2.19 *** | 9,950 |

| Cambodia | 10.46 ** | 6.67 | 5.65 | 5.23 ** | 323 |

| Indonesia | 9.47 *** | 4.79 *** | 2.22 + | 0.99 * | 437 |

| Malaysia | 5.04 ** | 2.76 | 1.86 | 2.09 ** | 263 |

| Philippines | 10.79 *** | 6.09 *** | 2.51 | 2.06 *** | 5,614 |

| Thailand | 11.06 *** | 7.46 *** | 2.20 | 3.47 *** | 863 |

| Vietnam | 9.25 *** | 5.60 *** | 5.03 ** | 2.54 *** | 2,138 |

| INDIA/SOUTHWEST ASIA | 6.15 *** | 5.10 *** | 3.66 *** | 2.70 *** | 12,295 |

| Afghanistan | 11.27 ** | 6.61 | 5.62 | 4.13 | 109 |

| India | 5.74 *** | 5.00 *** | 3.61 *** | 2.71 *** | 11,246 |

| Iran | 8.21 *** | 6.05 * | 3.22 | 3.83 *** | 567 |

| Nepal | 7.23 ** | 4.21 | 4.16 | 3.44 *** | 373 |

| MIDDLE EAST/ASIA MINOR | 7.94 *** | 6.29 ** | 4.04 | 4.00 *** | 2,084 |

| Iraq | 9.00 ** | 6.82 | 4.97 | 4.79 *** | 388 |

| Israel | 4.46 | 4.43 | 2.10 | 3.07 ** | 280 |

| Jordan | 9.36 | 11.51 + | 7.94 | 6.41 ** | 134 |

| Lebanon | 9.33 * | 6.11 | 4.97 + | 6.91 *** | 235 |

| Saudi | 8.42 *** | 6.21 ** | 3.99 + | 1.41 * | 242 |

| Syria | 9.69 | 11.92 * | 5.02 | 6.18 *** | 157 |

| Turkey | 7.44 *** | 6.71 ** | 2.15 | 2.24 ** | 443 |

| Yemen | 6.04 + | 4.28 | 3.52 | 1.47 | 205 |

| AFRICA | 8.74 *** | 6.04 *** | 4.80 ** | 3.95 *** | 4,250 |

| Nigeria | 10.53 *** | 5.55 | 4.80 | 5.23 *** | 614 |

| Ethiopia | 7.56 ** | 9.03 *** | 4.78 | 4.04 *** | 443 |

| Egypt/UAE | 7.56 * | 7.38 + | 4.66 | 4.82 *** | 397 |

| Ghana | 7.79 *** | 5.10 * | 3.42 | 3.19 *** | 502 |

| Kenya | 10.07 *** | 4.57 | 4.54 | 3.15 | 446 |

| Morocco | 10.14 *** | 7.05 | 5.13 | 4.93 *** | 382 |

| South Africa | 5.84 *** | 5.15 ** | 5.33 ** | 2.31 *** | 348 |

| Other Africa | 9.48 *** | 6.48 ** | 5.17 | 4.29 *** | 1,118 |

| AUSTRALIA | 3.09 | 2.92 | 1.87 | 1.72 ** | 573 |

Predicted age gap based on regression models including age at marriage, years of education and an indicator of remarriage.

p<.001;

p<.01;

p<.05;

p<.10

Appendix Table 4.

Predicted Spousal Age Gap by Timing of Marriage, Migration and Spousal Citizenship and Region: Noncitizen Male Respondents.

| Men Respondents | Unweighted Number of Cases | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Spouse is a Citizen at Marriage | Spouse is a Non-Citizen at Marriage | ||||

|

| |||||

| Marry Before/On Arrival | Marry After Arrival | Marry Before/On Arrival | Marry After Arrival | ||

|

| |||||

| CANADA | 1.69 | 2.67 | 2.06 | 2.67 ** | 1,934 |

| LATIN AMERICA/CARIBEAN | 0.58 *** | 1.32 *** | 3.18 *** | 2.80 *** | 29,440 |

| Mexico | 1.45 *** | 1.48 *** | 3.17 *** | 2.55 *** | 19,137 |

| Central America | −0.13 *** | 0.78 *** | 3.60 ** | 2.82 *** | 5,552 |

| Cuba | −1.44 ** | 1.19 ** | 3.93 + | 3.06 *** | 1,334 |

| West Indies | −0.05 *** | 1.33 *** | 2.45 *** | 4.00 *** | 3,417 |

| SOUTH AMERICA | 0.76 *** | 0.95 *** | 2.99 | 2.78 *** | 5,309 |

| NORTHERN/WESTERN EUROPE | 1.41 * | 2.09 | 2.31 | 2.27 *** | 4,265 |

| Sweden | 1.37 | 1.80 | 2.12 | 1.19 ** | 131 |

| UK | 1.77 | 2.42 | 2.56 | 2.46 *** | 2,787 |

| France | 0.91 | 0.62 + | 1.30 | 1.65 ** | 578 |

| Netherlands | 0.53 | 2.27 | 2.57 | 1.16 *** | 250 |

| Denmark/Norway/Finland/Iceland | 1.36 | 3.66 | 2.19 | 3.33 * | 221 |

| Switzerland/Belgium/Austria | 0.65 + | 0.87 * | 3.61 | 3.06 | 298 |

| SOUTHERN EUROPE | 1.96 ** | 1.89 ** | 3.33 | 3.51 ** | 1,142 |

| Albania | 3.18 | 0.03 ** | 5.90 + | 3.92 | 148 |

| Greece | 3.94 | 1.57 | 4.52 | 3.20 | 148 |

| Italy | 2.35 | 2.98 | 2.92 | 2.59 ** | 424 |

| Spain | −0.38 ** | 0.54 * | 2.01 | 2.73 * | 422 |

| CENTRAL/EASTERN EUROPE | 1.34 *** | 0.79 *** | 2.69 * | 3.32 *** | 2,822 |

| Bulgaria | 3.05 | 0.47 + | 2.30 | 2.63 ** | 195 |

| Czechoslovakia | −0.80 * | 0.27 ** | 1.20 * | 3.60 | 158 |

| Germany | 1.57 ** | 1.29 *** | 3.12 | 3.72 ** | 971 |

| Hungary | 2.93 | −1.01 * | 2.54 | 2.26 * | 112 |

| Poland | 2.67 | 1.43 ** | 2.40 + | 3.25 | 665 |

| Romania | 1.58 + | −0.14 ** | 2.38 | 3.07 * | 363 |

| Yugoslavia | 0.34 ** | 0.65 *** | 3.32 | 3.52 | 358 |

| RUSSIA/BALTIC STATES | 0.53 *** | 1.42 *** | 3.19 + | 3.78 + | 1,521 |

| EAST ASIA | 1.06 *** | 1.31 *** | 2.35 | 2.55 *** | 6,102 |

| China | 0.67 *** | 1.12 *** | 2.50 | 2.55 *** | 3,787 |

| Japan | 1.02 | 0.88 | 1.94 | 2.21 *** | 660 |

| Korea | 1.02 ** | 1.60 + | 2.07 | 2.36 *** | 1,403 |

| Other Asia | 4.00 | 2.66 | 3.66 | 3.99 | 252 |

| SOUTH EAST ASIA | 0.45 *** | 1.68 *** | 2.77 | 3.03 *** | 3,666 |

| Cambodia | 1.98 | 2.50 | 4.56 | 3.04 | 107 |

| Indonesia | −0.02 + | 2.20 | 3.25 | 2.96 ** | 208 |

| Malaysia | 3.09 | 3.39 | 2.49 | 2.33 | 159 |

| Philippines | 0.34 *** | 1.17 ** | 2.36 | 2.61 *** | 2,055 |

| Thailand | 3.38 | 0.15 | 3.51 | 2.23 | 192 |

| Vietnam | 1.00 *** | 2.47 ** | 3.47 | 4.33 * | 802 |

| INDIA/SOUTHWEST ASIA | 1.54 *** | 1.93 *** | 3.44 *** | 3.78 *** | 12,044 |

| Afghanistan | 2.33 * | 3.69 + | 4.91 | 6.34 | 11,173 |

| India | 1.57 *** | 1.85 *** | 3.46 ** | 3.75 *** | 414 |

| Iran | 1.83 * | 2.54 ** | 3.00 * | 4.91 * | 348 |

| Nepal | 1.88 | 2.83 | 4.04 | 3.99 *** | 109 |

| MIDDLE EAST/ASIA MINOR | 2.20 *** | 2.10 *** | 4.37 | 4.08 *** | 2,165 |

| Iraq | 3.71 | 4.55 | 5.34 | 4.14 ** | 376 |

| Israel | 2.03 | 0.83 ** | 1.88 + | 3.38 | 366 |

| Jordan | 5.03 | 2.86 * | 7.29 | 6.14 | 160 |

| Lebanon | 3.04 * | 2.89 * | 5.51 | 5.76 | 223 |

| Saudi | 1.48 + | 2.30 | 3.86 | 3.73 ** | 225 |

| Syria | 1.54 * | 4.36 + | 5.91 | 6.40 | 137 |

| Turkey | −1.07 ** | 0.86 ** | 2.31 | 2.84 ** | 480 |

| Yemen | 4.17 | 3.92 | 3.88 | 3.82 + | 198 |

| AFRICA | 0.38 *** | 2.29 *** | 5.47 * | 4.89 *** | 4,574 |

| Nigeria | 2.14 *** | 3.14 ** | 4.79 | 5.05 *** | 679 |

| Ethiopia | 1.24 *** | 0.45 ** | 5.61 | 4.79 *** | 351 |

| Egypt/UAE | −1.07 *** | 2.24 ** | 5.28 | 5.79 | 464 |

| Ghana | 0.27 ** | 3.16 | 5.59 + | 4.14 *** | 539 |

| Kenya | 2.40 | 3.11 | 5.61 *** | 3.19 *** | 422 |

| Morocco | −1.76 *** | 1.79 *** | 5.29 | 5.69 *** | 402 |

| South Africa | 1.92 | 2.18 | 5.59 | 3.81 ** | 397 |

| Other Africa | −0.46 *** | 1.75 *** | 5.73 | 5.55 ** | 1,320 |

| AUSTRALIA | 1.41 | 1.55 | 2.63 | 1.55 ** | 729 |

Predicted age gap based on regression models including age at marriage, years of education and an indicator of remarriage.

p<.001;

p<.01;

p<.05;

p<.10

The result provides strong evidence of exchange – youth for access to spousal citizenship net of education, past marital history and age at marriage. For example, among brides from Southeast Asia, those marrying a citizen either before or upon entering the US are roughly 10 years younger than their spouse. Once the non-citizen woman is in the US and marries a citizen, the predicted spousal age difference drops to 6 years. When a Southeast Asian woman marries a non-citizen outside of the US or upon entering the exchange is smaller at only 2.5 years, falling to 2 years when marrying a non-citizen in the US. Among non-citizen women from Russia and the Baltic States, the predicted age gap is 9.1 years for marriages to a citizen that occur prior to or upon her arrival, falling to 6.5 for marriages to a non-citizen after she has resided in the US for at least a year, 3.2 years for marriages to a fellow non-citizen either prior to or upon arrival, and 2.7 years for marriages to a non-citizen after she has resided in the US for at least a year. We find this continuum of exchange for all regions with the exception of immigrant women from Canada.

It is notable that the exchange also appears for male immigrants but the patterns are less pronounced. Figure 3 shows that for many regions, immigrant men who marry a citizen either before entry or upon arrival are closest in age to their bride. For example, among Southeast Asian non-citizen men married to citizen women the predicted age gap is just 0.45 years, for African men 0.38 years, and for Russian men 0.53 years. This gap widens with marriage to a non-citizen.

To examine the robustness of our findings we also conducted several sensitivity analyses. While the decision to collapse the timing of migration and marriage into two categories –marriage before or upon arrival vs. marriage after arrival—was conceptually driven by prior research, we explored whether the patterns varied if we used an unclasped version of marriage/migration timing. Appendix Table 2 presents the unadjusted weighted mean spousal age difference for respondent men and women by spousal citizenship status for those who married prior to migrating to the US, those who married and migrated in the same year, and those who married after arrival in the US. Here, we find still find evidence that marriage to a citizen is associated with large spousal age differences for female respondents and small spousal age differences for male respondents compared with marriage to a non-citizen. Female respondents who marry a citizen prior to entering the US are on average 7.2 years younger than their husbands, and those who marry a citizen the same year they enter the US are 7.6 years younger than their husbands—both figures are much higher than the difference when she marries a citizen after already arriving in the US(4.5 years). Among male respondents we see a similar pattern: the spousal age gap for marriage to a citizen prior to migrating is 0.9 years and 0.4 years when marrying a citizen the same year as arrival. Again, both figures are smaller (meaning the husbands are much closer in age to their wives) than when a non-citizen man marries a citizen woman after he has already arrived in the US. Similar patterns are found for both male and female respondents married to non-citizens.

Appendix Table 2.

Spousal age gap across uncollapsed categories of timing of marriage, migration and spousal citizenship, Weighted means (unweighted N)

| IMMIGRANT WOMEN RESPONDENTS | IMMIGRANT MEN RESPONDENTS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| SPOUSE CHARACTERISTICS | Married prior to arrival in US | Married the same year as arrival | Married after arrival in US | Married prior to arrival in US | Married the same year as arrival | Married after arrival in US |

| SPOUSE HELD US CITIZENSHIP AT MARRIAGE | 7.2 | 7.6 | 4.5 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 1.9 |

| 15,961 | 9,421 | 23,584 | 3,538 | 3,735 | 19,135 | |

| Native born Spouse | ||||||

| Same-race/panethnicity | 4.5 | 5.2 | 3.3 | 1.78 | 0.65 | 2.35 |

| 2,106 | 3,456 | 6,854 | 1,690 | 1,919 | 8,633 | |

| Different-race/panethnicity | 7.7 | 9.3 | 4.6 | −0.37 | −.80a | 1.86 |

| 1,994 | 3,813 | 6,319 | 556 | 641 | 3,994 | |

| Naturalized Spouse | ||||||

| Same-race/panethnicity | 8.3 | 7.8 | 5.4 | 0.34 | 0.60a | 1.41 |

| 3,856 | 4,336 | 7,436 | 1,226 | 1,080 | 5,916 | |

| Different-race/panethnicity | 10.0 | 10.6a | 6.1 | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.75 |

| 166 | 310 | 690 | 66 | 95 | 592 | |

| SPOUSE DID NOT HOLD US CITIZENSHIP AT MARRIAGE | 3.4 | 3.3a | 1.6 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 3.3 |

| 8,122 | 11,915 | 21,299 | 12,504 | 4,658 | 32,143 | |

| Same-race/panethnicity | 3.4 | 3.3a | 1.5 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 3.3 |

| 15,548 | 9,193 | 22,688 | 12,158 | 4,512 | 31,090 | |

| Different-race/panethnicity | 3.0 | 3.5a | 2.1 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 3.1 |

| 413 | 228 | 896 | 346 | 146 | 1,053 | |

Weighted means and unweighted sample sizes shown. Spousal age gap = (Husband age - Wife age). Differences in mean spousal age gap across timing categories are all statistically significant to the p< .05

Estimate not significantly different from “Married prior to arrival in the US”

Estimates not significantly different across all marriage/migration categories.

As we noted earlier, prior studies on cross-border marriages classify the spouses of immigrants in a variety of ways. For instance, Lichter et al. (2015) distinguish the race of spouses in examining intermarriage between immigrants and natives. In Appendix Table 2, we also show the age gap by spousal nativity and citizenship status at the time of marriage for same-and different-race/ethnic marriages. Here, we still see the importance of the relationship between timing and citizenship status of the spouse, and also the importance of race/ethnicity. For example, among non-citizen women marrying a native-born citizen either before entering the US or the same year of entry the cost in terms of youth is higher for women marrying a different-race/ethnic spouse than those marrying a same-race/ethnic spouse.

Another possible explanation for these patterns might be that there are cultural preferences for age heterogamous marriages. In other words, perhaps in certain countries large spousal age differences are normative. While we do not have comparable data on recent marriages of non-migrants in the sending countries (i.e., Philippines, India, Russia), in supplemental analyses we examined the spousal age differences among couples in our sample who share the same country of origin (not shown). If a large spousal age gap is culturally normative in certain sending countries, then we would expect little variation by either citizenship of the partner or timing of migration and marriage among couples who are from the same country. However, we find the opposite. For example, among non-citizen women respondents married to naturalized citizen men who share the same country of birth, the spousal age difference ranged from 7.6 years for those married prior to or upon arrival, 5.1 years for those married to a naturalized citizen after arrival, 3.2 years for those married to a non-citizen either prior to or upon arrival, and finally 1.6 years for those married to a fellow non-citizen. Among non-citizen men married to a citizen woman who shares the same country of origin the spousal age difference ranges from 0.6 years for those married prior to or upon arrival, 1.5 years for those married to a citizen woman after arrival, 2.6 years for those married to a non-citizen woman prior to or upon arrival and 3.3 years for those married to a non-citizen woman after arrival. Similar patterns were found when we examined couples that shared the same region of origin.

DISCUSSION

Prior studies on marriage patterns of immigrants assume that they meet their partners in the US. This research was unable to consider how the relative timing of marriage and migration may affect the matching of spouses by citizenship status and relative age. As less traditional patterns of migration and courtship emerge, scholars studying intermarriage in the US must revise their notion that migration and marriage are independent processes. Indeed, as cross-border marriages become more visible, it is likely that these immigrant spouses face unique opportunities (e.g. a ‘fast track’ toward permanent residency or American citizenship) and challenges (e.g. power differentials due to differences in the citizenship of partners) relative to immigrants who marry other immigrants. While journalistic accounts of “mail-order brides” or marriage tourism are common, virtually no research using nationally-representative population-based data from the US has examined unions formed through these channels. The few quantitative studies of this phenomenon has focused on European and Asian countries. While we are not able to account for the circumstances under which the couple met, our innovation is to examine immigrant marriages by being attentive to the relative timing of marriage and migration as well as the citizenship status and the relative age of spouses.

The large scale of the Census data with the newly available information on the timing of marriage, migration and citizenship acquisition enabled us to present a more complete portrait of cross-border marriage in the US than was previously possible. Our analyses of these data give us a broader view of partner selection and allow us to more carefully examine the possible exchange of desired characteristics (youth and citizenship status) between partners. Our research highlights the complex association between marriage and migration in a way that has been neglected by most demographers, sociologists and economists. We find that among non-citizens, marriage to a citizen (whether native-born or naturalized) is a common event, particularly among women. Nearly 43% of non-citizen female migrants married in the last ten years are married to a citizen of the US, in contrast to 32% of comparable male migrants. Also, the importance of the timing of migration vis-à-vis marriage should not be understated. A substantial proportion of non-citizen female migrants marry a citizen before or upon arrival, suggesting that for many, the decision to marry and the decision to migrate are linked.

We also find that the nexus of marriage, migration, and spousal citizenship provides possible evidence of status exchange for men and women alike—citizens in the US who reach beyond their local marriage markets and across international borders for a spouset end to secure a relatively more youthful partner. On average, non-citizen female migrants marrying a citizen either before or upon entry are 7 years younger than their spouses. Once she is in the US, the exchange becomes less pronounced but is still substantial. The opposite holds true for men. We find evidence that non-citizen men who marry a woman with citizenship either prior to or upon arrival in the US are closer in age to their spouse than their counterparts who marry a non-citizen.

Qualitative research suggests that settled migrants, in this case, those who have earned citizenship, may have a strategic advantage in marriage negotiations (e.g. Charsley 2005). Beck-Gernsheim suggests “(s)ince they have much to offer—the ticket to migration—they can likewise demand much in return” (2007: p. 280). Our findings support this notion. Among respondent marriages to non-citizens spouses, we find evidence of exchange based on the timing of marriage and migration. Non-citizen women who marry a non-citizen man in their home country or upon entering face a more expensive 'ticket’ with respect to spousal age than comparable women who arrive in the US and marry later. In many sending communities, the social position of the migrant is enhanced by migrating to the US (e.g. Kanaiaupuni 2000; Lievens 1999; Charsley and Shaw 2006). It may be that once the migrant comes to the US and earns citizenship, s/he is in a better social position to choose a spouse (i.e. younger) from his/her countries than before the migrant received his/her US citizenship.

Future research should consider whether marriage migrants to the US are entering into communities that are at least some what culturally familiar and whether their movement is part of a larger stream of transnational movement into local areas. Given the prior studies show that dissimilarity between partners in characteristics such as age, ethnicity and nativity increase the risk of marital instability (e.g., Zhang and Van Hook 2009; Kalmijin et al 2005), future studies should also examine cross-border marriages in the long-term. In addition, future studies could examine how the elasticity of the effect of husband’s age at marriage differs by whether they are partnered with native-born women versus non-citizen or women who naturalized prior to marriage. Finally, the patterns of spousal age gaps found here suggest a need for more research on the longer term health and well-being of marriage migrants and spouses in the US. Particularly since having a much younger spouse is beneficial for men’s longevity, but it is detrimental for women’s (Drefahl 2010).

Some limitations are worth noting. First, our findings cannot assess specific cultural or structural conditions influencing the timing of marriage and migration, nor are we able to determine what motivates men and women to seek out partners outside of their local marriage market. Nor can we understand how these motivations contribute to marital quality or gendered imbalances in power. We do not know how or where the cross-border couples first met, whether they were introduced through the auspices of a marriage broker website, or were introduced through links with extended kin or transnational communities. While there is exciting new qualitative research on these types of marriages in the US that sheds light on possible motivations and outcomes, our research fills a void by providing evidence of a marital exchange that occurs at the intersection of timing of migration and spousal citizenship. Our findings are consistent with many of the findings suggested by qualitative research on marriage migration. Importantly, they indicate that for many immigrants, particularly female immigrants, marriage may not be the final but the first step in the process of obtaining full citizenship in American society.

Acknowledgments

This research received infrastructure support from The Center for Family and Demographic Research at Bowling Green State University which has core funding from The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (R24HD050959).

Contributor Information

Kelly Stamper Balistreri, Assistant Professor of Sociology, Bowling Green State University.

Kara Joyner, Professor of Sociology, Bowling Green State University.

Grace Kao, Professor of Sociology, Education and Asian American Studies, University of Pennsylvania.

References

- Appadurai A. Marriage, migration and money. Visual Anthropology. 1991;4:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Aptekar S. The Road to Citizenship: What Naturalization Means for Immigrants in the United States. Rutgers University Press; New Jersey: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Beck-Gernsheim E. Transnational lives, transnational marriages: A review of the evidence from migrant communities in Europe. Global Networks. 2007;7(3):271–288. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein N. Do You Take This Immigrant? New York Times. 2010 http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/13/nyregion/13fraud.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0.

- Betts JR, Lofstrom M. Issues in the Economics of Immigration. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2000. The Educational Attainment of Immigrants: Trends and Implications; pp. 51–116. [Google Scholar]

- Bohra-Mishra P, Massey DS. Intermarriage among New Immigrants in the U.S.A. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2015;38(5):734–758. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2014.937726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charsley K. Unhappy husbands: Masculinity and migration in transnational Pakistani marriages. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 2005;11(1):85–105. [Google Scholar]

- Charsley K, Shaw K. South Asian transnational marriages in comparative perspective. Global Networks. 2006;6(4):331–344. [Google Scholar]

- Choi K, Tienda M, Cobb-Clark D, Sinning M. Immigration and Status Exchange in Australia and the United States. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. 2012;30(1):49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K, Vasunilashorn S. Widowhood, age heterogamy, and health: The role of selection, marital quality, and health behaviors. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2013;69B(1):123–134. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SYP, Cheung YW, Cheung AKL. Social isolation and spousal violence: Comparing female marriage migrants with local women. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74:444–461. [Google Scholar]

- Constable N. The commodification of intimacy: Marriage, sex, and reproductive labor. Annual Review of Anthropology. 2009;38:49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Constable N. Romance on a Global Stage: Pen Pals, Virtual Ethnography, and Mail Order Marriages. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dean G, Gurak DT. Marital homogamy the second time around. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1978;40(3):559–70. [Google Scholar]

- Drefahl S. How does the age gap between partners affect their survival? Demography. 2010;47(2):313–326. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwert A. Opposites attract: Evidence of status exchange in ethnic intermarriages in Sweden. Lund Papers in Economic History, Population Economics. 2016:147. [Google Scholar]

- England P, McClintock EA. The gendered double standard of aging in U.S. marriage markets. Population and Development Review. 2009;35(4):797–816. [Google Scholar]

- Donato KM, Alexander JT, Gabaccia DR, Leinonen J. Variations in the gender composition of immigrant populations: How they matter. International Migration Review. 2011;45:495–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2011.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon Milton M. Assimilation in American Life. New York: Oxford University Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Guetto R, Azzolini D. An empirical study of status exchange through migrant/native marriages in Italy. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 2015;41(13):2149–2172. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson Per, Urban Fransson. Age Differences between Spouses: Sociodemographic Variation and Selection. Marriage & Family Review. 2015;51(7):610–632. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild AR. Love and Gold. In: Ehrenreich Barbara, Hochschild Arlie R., editors. Global Woman: Nannies, Maids, and Sex Workers in the New Economy. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books; 2003. pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hooghiemstra E. Migrants, Partner Selection and Integration: Crossing Borders? Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 2001;32(4):601–626. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SH. Marriages of convenience: International marriage brokers, mail-order brides, and domestic servitude. U Tol L Rev. 2006;38:895. [Google Scholar]

- Jasso G, Massey DS, Rosenzweig M, Smith JP. The New Immigrant Survey Pilot (NIS-P): Overview and new findings about U.S. legal immigrants at admission. Demography. 2000;37(1):127–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]