Abstract

Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) is a spiritual program and involvement in it has been associated with increases in spirituality. Some who pursue recovery outside AA also use spirituality for support. Decreasing drinking without AA involvement might result in spiritual change, but this has not been explored in previous research. This study investigates drinking and AA behavior to determine their association with seven dimensions of subsequent spirituality.

Methods

A 30-month panel study recruited 364 individuals with alcohol dependence. Multilevel models examined drinking and AA at six months as predictors of both the levels and trajectories of seven dimensions of spirituality assessed five times over 6 – 30 months.

Results

Controlling for AA involvement, less drinking was associated with higher levels of purpose in life, self-forgiveness, and spiritual/religious practices. Controlling for drinking, greater AA involvement was associated with higher levels of positive religious coping, daily spiritual experiences, forgiveness of others, and spiritual/religious practices. Neither AA nor drinking predicted trajectories of spirituality. Data visualizations identified a pattern of elevated purpose in life and self-forgiveness among individuals who were abstinent and among individuals who drank less intensely.

Conclusions

Reduced drinking influenced aspects of spirituality that have been shown to respond to experience and maturation. AA was associated with aspects of spirituality embedded in the 12 steps which have been shown to be responsive to learning and modeling. This knowledge has the potential to inform decisions about recovery options, and contributes to theoretical understandings of the nature of spiritual change over the course of addiction recovery.

One of the contributions of the addiction recovery advocacy movement (White, 2007b) is greater acceptance of the various pathways through which individuals recover from addiction (Flaherty, Kurtz, White, & Larson, 2014; White, 2007b; White & Kurtz, 2010). While spirituality plays an important role in distinguishing different recovery pathways, this relationship is complex. For example, spirituality is a hallmark of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and yet some in AA are atheists and agnostics (see, e.g., aaagnostica.com and Freedman (2014)). Conversely, some who recover outside of AA actively use spirituality and/or religiousness to support and sustain recovery (e.g., Morjaria-Keval (2006) and Morjaria-Keval & Keval (2015)). Clarification of the role of spirituality outside of the 12 step model is necessary to better understand the complex relationship between spirituality and recovery. AA has been shown to foster some dimensions of spiritual change such as spiritual/religious practices, daily spiritual experiences, and forgiveness of others (Krentzman, Cranford, & Robinson, 2013). An important question that has not been addressed is whether decreased drinking is associated with increases in spirituality while holding AA participation constant. Quitting or reducing drinking by itself can result in improvements in physical, social, and emotional wellness including reconciliation with loved ones and improved occupational performance. In addition to these benefits, could decreasing or stopping drinking result in increases in spirituality or religiousness?

The question is important for a number of reasons. First, spirituality is important to recovery (Miller, 2013). Increases in spirituality and/or religiousness have been associated with subsequent reduced drinking (Robinson, Cranford, Webb, & Brower, 2007; Robinson, Krentzman, Webb, & Brower, 2011; Tonigan, Rynes, & McCrady, 2013). Certain spiritual experiences, such as having had a spiritual awakening, have predicted lower rates of drinking, specifically, higher rates of abstinence and no return to heavy drinking, among patients in treatment for alcohol dependence (Strobbe, Cranford, Wojnar, & Brower, 2013). Having had a spiritual awakening also has been associated with lower craving among individuals who are in recovery (Galanter, Dermatis, & Santucci, 2012; Galanter, Dermatis, Stanievich, & Santucci, 2013). Higher frequency of “Feeling God’s presence” among individuals in recovery has been associated with lower levels of craving and depression, factors protective against relapse (Galanter, Dermatis, Post, & Sampson, 2013).

Second, the relationship between decreased drinking and spirituality is important because evidence suggests that spirituality is valued by some who recover outside of AA. Granfield and Cloud (2001) studied individuals who achieved natural recovery and found that many had had spiritual awakenings, religious conversions, and/or had turned to religious institutions for support. Matzger and colleagues conducted a study of problem drinkers recruited from addiction treatment programs and the general community. Among those who were drinking “a lot less” one year later, 16% of the untreated and 43% of the treated sample stated that they drank less because of a “religious or spiritual experience.” For both groups, having had a religious or spiritual experience significantly predicted sustained remission at follow-up (Matzger, Kaskutas, & Weisner, 2005).

Third, knowledge of the role of spirituality in diverse recovery pathways can help counselors make appropriate recommendations. Evidence suggests that finding a good match between spiritual/religious beliefs and the right recovery pathway is important. One study of different recovery groups (12-step programs, Self Management for Addiction Recovery (SMART Recovery), Women for Sobriety, and Secular Organizations for Sobriety (SOS)) showed that while average length of sobriety was similar across groups, spiritual and religious factors were more likely to predict higher levels of program participation among 12-step members than SMART or SOS members (Atkins & Hawdon, 2007).

Dataset Employed in the Current Study

The current study uses the Life Transitions Study dataset (Robinson et al., 2011). The study collected data from 364 individuals diagnosed with alcohol dependence at baseline and every three months for 30 months from 2004 to 2009. The current study addresses one of the primary aims of the Life Transitions Study: the investigation of change in spirituality and religiousness among individuals with alcohol use disorders. In prior work from this study, Robinson and colleagues (2011) studied the relationship between change in spirituality at an earlier time point and subsequent drinking. This is in reverse to the causal assumption of the current study, which is that decreases in drinking at an earlier time point would have an effect on subsequent spirituality. Robinson and colleagues found that several dimensions of spirituality changed between baseline and six months and that these changes were associated with less drinking at nine months. In addition, Krentzman and colleagues (2013) employed the Life Transitions Study to explore a set of spiritual mediators of the effect of AA on drinking and in so doing, found that AA Involvement at 6 months was associated significantly with private religious practices, daily spiritual experiences, and forgiveness of others at 12 months. Therefore, as we set out to conduct the current study, we were aware that AA at an earlier time point was related to certain dimensions of spirituality (although only to the level of the spirituality variable at the 12 month follow up and not to spiritual change over time) and we were aware of the association of early spiritual change on later drinking. No prior published work that we are aware of has examined the important question of the effects of early change in drinking on subsequent changes in spirituality while controlling for the effects of AA involvement.

Research Questions Guiding the Current Study

Because the recovery phase from alcohol use disorders can be many years in duration, long-term assessment of spirituality is important. We hypothesize that early changes in AA and drinking will have an effect on levels of subsequent spirituality and on the rate of change in subsequent spirituality over 30 months. In the current study, seven dimensions of spirituality are examined: daily spiritual experiences, positive religious coping, negative religious coping, forgiveness of others, forgiveness of self, purpose in life, and spiritual/religious practices. As mentioned, prior work suggests that AA involvement will be associated with private religious practices, daily spiritual experiences, and forgiveness of others (Krentzman et al., 2013) and we hypothesize that AA involvement should still affect these factors as they evolve over 30 months. However the existing literature does not provide enough guidance to pose specific hypotheses related to which of these seven spirituality dimensions will change in terms of level or slope over 30 months nor which of the spirituality dimensions will be affected by previous reductions in drinking while controlling for AA. Therefore, this exploratory study employs a sample of individuals diagnosed with alcohol use disorders to answer the following questions: What is the association between decreases in drinking between baseline and 6 months on subsequent levels and trajectories of seven dimensions of spirituality, while controlling for AA involvement? What is the association between increases in AA involvement between baseline and 6 months on subsequent levels and trajectories of seven dimensions of spirituality, while controlling for drinking?

Method

The current study is part of a larger investigation of long-term spiritual changes secondary to recovery from alcohol use disorders. The study is a three-year naturalistic, longitudinal investigation of 364 individuals with alcohol dependence undertaken to assess relationships between alcohol dependence, recovery, and multiple dimensions of spirituality, including the nature of spiritual change (Robinson et al., 2011). This work was inspired in part by the work of Idler, et al. (2003) and Pargament (2001) who defined spirituality and religiousness as a multi-dimensional construct comprised of diverse dimensions including theistic, non-theistic, religious, and spiritual aspects. Therefore, the study assessed diverse dimensions of spirituality including the seven included in the current study.

Respondents were recruited from two abstinence-based outpatient treatment programs (one within a university health care system (n = 157, 43.1%) and one within the Veterans Administration (n = 80, 22.0%)); a moderation-based program which promoted healthier drinking behavior including reduced drinking (n = 34, 9.3%); and the community at large (n = 93, 25.5%). The community sample was not in treatment for alcohol-use disorders at baseline but 44.1% had been in treatment previously and 39.8% entered treatment between baseline and the study’s 30 month follow-up. Inclusion criteria included being at least 18 years of age, diagnosis of lifetime alcohol dependence, drinking alcohol in the last 90 days, and English literacy. Exclusion criteria were active suicidality, homocidality, and/or psychosis. Chart reviews identified potential participants in the abstinence-based programs, clinician recommendations identified potential participants in the moderation-based program, and newspaper advertisements recruited individuals in the community. Of those contacted for recruitment, the majority (77.6%) were successfully enrolled. At baseline and every 6 months for 30 months, participants were compensated for assessment of substance use, spirituality, religiousness, participation in AA, and psychosocial characteristics. Written informed consent was obtained and the appropriate institutional review boards approved the study. For additional details about the study design and data collection procedures, see Robinson et al. (2011).

Sample Characteristics

The sample ranged in age from 18–80 (M=44.0, SD=12.8), 34.3% were female. The majority identified as European-American (81.9%, n=298) and others identified as African-American (10.4%, n=38), Hispanic (1.6%, n=6), Native American (1.1%, n=4), Asian (0.5%, n=2), multi-racial (3.3%, n=12) and other (1.1%, n=4). Over one-third (38.2%) were married or co-habitating, and 56.0% were employed. Half (52.5%) had been in treatment previously and averaged 4.1 (SD 8.1) previous treatment episodes. More than half (57.4%) met criteria for severe alcohol dependence. The majority (86.5%) had family members with alcohol problems. At baseline, respondents reported 56.1% (SD = 31.3%) days abstinent and 9.5 (SD = 8.2) average drinks per drinking day in the previous 90 days.

Measures

AA involvement

AA involvement was assessed with the Alcoholics Anonymous Involvement Scale (Tonigan, Connors, & Miller, 1996). The items were 1) considering oneself a member, 2) attending 90 meetings in 90 days, 3) celebrating an AA anniversary, 4) being a sponsor and 5) having a sponsor. Individuals received 1 point for each response of “yes” and items were totaled to produce a single score (Cronbach’s alpha = .80). One item was excluded, “Have you ever had a spiritual awakening or conversion experience since your involvement in AA?” so that the measure would capture involvement not explicitly of a spiritual nature as has been employed elsewhere, e.g., Owen et al. (2003).

Drinking

The TimeLine FollowBack Interview (Sobell, Brown, Leo, & Sobell, 1996; Sobell & Sobell, 1992) was used to collect drinking data and calculate average drinks per drinking day (DDD) as a measure of drinking intensity and percent days abstinent (PDA) as a measure of drinking frequency over the previous 90 days. We refer to these two measures as measures of drinking behavior.

Spirituality/Religiousness

Daily spiritual experiences

Everyday experiences such as feelings of peacefulness and love were measured with the Daily Spiritual Experiences instrument (Underwood & Teresi, 2002). Fifteen items used a 6-point response format ranging from never or almost never to many times a day, while one item assessed closeness to God using a 4-point response format ranging from not at all close to as close as possible. Eight items referenced God (e.g., “I feel God’s love for me, through others”) while eight items did not (e.g., “I feel deep inner peace or harmony”). Cronbach’s alpha = .94.

Positive and negative religious coping

The original architects of the Life Transitions study used a combination of two versions of the Brief RCOPE instrument (Fetzer Institute, 2003; Pargament, Smith, Koenig, & Perez, 1998) to measure the degree to which God is experienced as benevolent (positive religious coping) or punitive (negative religious coping) during stressful times. They retained 13 items of the Brief RCOPE listed on page 718 of Pargament, et al. (1998) omitting the item, “Wondered whether my church had abandoned me.” They removed this item so that the scale would be relevant to participants who did not have a church affiliation. They included three additional positive religious coping and two additional negative religious coping items from the Brief RCOPE listed on page 717 of Pargament, et al. (1998, items 1–3, 14, and 17) yielding a total of 18 items: 10 assessing positive religious coping and 8 assessing negative religious coping. All items employed a 4-point Likert-type response format ranging from not at all to a great deal. Fourteen of the 18 items reference God including seven positive religious coping items (e.g., “Looked to God for strength, support and guidance”) and seven negative religious coping items (e.g., “Wondered what I did for God to punish me”), Cronbach’s alpha at baseline was .93 for positive religious coping and .74 for negative religious coping.

Forgiveness

Forgiveness was measured with two subscales of the Behavior Assessment System instrument: Forgiveness of Self (“It is easy for me to admit that I am wrong”) and Forgiveness of Others (“I feel that other people have done more good than bad for me”) (Mauger et al., 1992). Each subscale employs 15 true/false items, Cronbach’s alphas at baseline were .83 and .77, respectively. Scores were coded so that high sub-scale values represented high levels of forgiveness.

Purpose in life

The Purpose in Life scale was employed to measure the presence of higher meaning and purpose in life (Crumbaugh, 1968; Crumbaugh & Maholick, 1964; Frankl, 1969). The scale employs 20-items and a 7-point response format with anchors defining lowest and highest scores, e.g., “In life I have…” 1=no goals or aims at all to 7=very clear goals and aims, Cronbach’s alpha at baseline was .88.

Spiritual/religious practices

The frequency of prayer, scripture reading, listening to religious programming, and saying grace before meals was assessed with the four-item Private Religious Practices instrument (Fetzer Institute, 2003). The response format ranged from 1=several times a day to 8=never. A fifth item assessed frequency of meditation. Cronbach’s alpha for the five items was .77 at baseline.

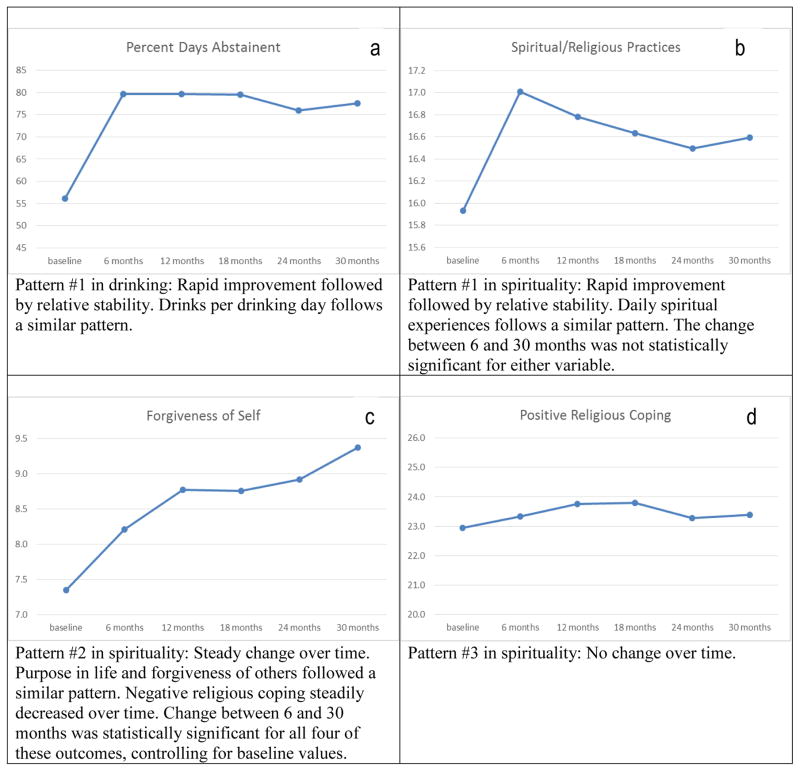

Research Design

The longitudinal prospective panel study design enabled the examination of the effects of shorter-term behavioral change in drinking and AA on longer-term levels and trajectories of seven dimensions of spirituality. The shorter-term phase from which to examine AA and drinking was defined as the period between baseline and the 6-month follow-up. This time frame was selected for two reasons. First, it was the period representing the greatest change in drinking (See Figure 1a). Second, during this period, statistically significant decreases in drinking occurred within each recruitment group. Among those who had just entered abstinent-based treatment at baseline (University and VA samples), drinks per drinking day decreased from 9.9 to 3.2 from baseline to 6 months, t(199) = 10.07, p < .001, and percent days abstinent increased from 65.1% to 91.6%, t(199) = −12.75, p < .001. For those who had just entered the moderation treatment program, drinks per drinking day decreased from 4.7 to 3.9 from baseline to 6 months, t(30) = 2.19, p < .05, and percent days abstinent increased from 34.6% to 53.6%, t(30) = −3.00, p < .01. For the remainder of the sample who were not in treatment at baseline, drinks per drinking day decreased from 8.9 to 5.4 from baseline to 6 months, t(84) = 3.16, p < .01, and percent days abstinent increased from 45.4% to 61.0%, t(84) = −4.50, p < .001. The sample therefore comprises individuals with alcohol use disorders who had diverse treatment experiences and drinking goals. Thus the data represented spirituality patterns associated with multiple recovery pathways.

Figure 1.

Visual inspection of average patterns of change for drinking and spirituality.

Six to 30 months was selected as the range to capture the spirituality outcome variables because it immediately followed the predictors of interest and because in this time frame, there is a linear structure for all outcome variables. Singer and Willett (2003) recommend visual inspection of data as the first step in multi-level modeling to determine the underlying structure of the data. Upon visual inspection of the two dimensions of drinking and each dimension of spirituality over all waves (i.e., baseline, 6, 12, 18, 24, and 30 months) for the sample average, we observed one pattern for change in drinking (Figure 1a) and three patterns for change in spirituality (Figure 1b–d). We observed a pattern of rapid initial change followed by stabilization for both drinking variables (Figure 1a). Spiritual/religious practices and daily spiritual experiences showed a pronounced change between baseline and 6 months and no difference between 6 and 30 months (Figure 1b). The remaining spirituality variables were either flat throughout time (positive religious coping, Figure 1d) or steadily changing throughout time (forgiveness of others, forgiveness of self, and purpose in life were increasing, negative religious coping was decreasing, Figure 1c). Therefore, from 6–30 months, each of these outcomes could be reasonably fit with linear models.

For each outcome, a series of nested models were fit as suggested by Singer and Willett (2003): an unconditional means model, an unconditional growth model, and conditional growth models. Conditional growth models tested (1) the effects of AA and drinking at 6 months on average levels of spirituality/religiousness from 6–30 months and (2) the effects of AA and drinking at 6 months on trajectories of spirituality/religiousness from 6–30 months. AA involvement and drinking were included in the same model to assess the effect of each while controlling for the other. Baseline AA and baseline drinking were included to adjust for the levels of these constructs at baseline. Separate sets of models were tested for the two different dimensions of drinking (drinks per drinking day on the left side of Table 1 and percent days abstinent on the right side of Table 1); each model included AA involvement.

Table 1.

Conditional Growth Model: Alcoholics Anonymous Involvement with each of Two Dimensions of Drinking at 6 Months Predict Six Dimensions of Spirituality from 6 to 30 Months

| Outcome: Average spirituality between 6 months to 30 months (Possible Range of Scores) | AA Involvement and Drinks per Drinking Day | AA Involvement and Percent Days Abstinent | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Predictor: AA and drinking assessed at 6 months | Beta Coefficient | p value | Confidence Interval | % Variance | Predictor: AA and drinking assessed at 6 months | Beta Coefficient | p value | Confidence Interval | % variance | |||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Lower | upper | lower | upper | |||||||||

| Spiritual/Religious Practices (5–37) | AA Involvement | 1.07 | 0.000 | 0.64 | 1.49 | 10.3% | AA Involvement | 0.90 | 0.000 | 0.47 | 1.33 | 11.8% |

| Drinks per Drinking Day | 0.07 | 0.117 | −0.02 | 0.15 | Percent Days Abstinent | 0.02 | 0.014 | 0.01 | 0.04 | |||

| Positive Religious Coping (10–40) | AA Involvement | 1.25 | 0.000 | 0.75 | 1.75 | 9.3% | AA Involvement | 1.20 | 0.000 | 0.69 | 1.71 | 9.0% |

| Drinks per Drinking Day | 0.08 | 0.111 | −0.02 | 0.18 | Percent Days Abstinent | 0.00 | 0.762 | −0.03 | 0.02 | |||

| Negative Religious Coping (8–32) | AA Involvement | −0.21 | 0.077 | −0.44 | 0.02 | 3.4% | AA Involvement | −0.21 | 0.083 | −0.44 | 0.03 | 4.3% |

| Drinks per Drinking Day | 0.04 | 0.063 | 0.00 | 0.09 | Percent Days Abstinent | −0.01 | 0.198 | −0.02 | 0.00 | |||

| Daily Spiritual Experiences (16–94) | AA Involvement | 2.64 | 0.000 | 1.63 | 3.65 | 13.4% | AA Involvement | 2.59 | 0.000 | 1.56 | 3.62 | 13.1% |

| Drinks per Drinking Day | 0.00 | 0.984 | −0.19 | 0.20 | Percent Days Abstinent | 0.01 | 0.829 | −0.04 | 0.05 | |||

| Purpose in Life (20–140) | AA Involvement | 0.96 | 0.172 | −0.42 | 2.34 | 6.6% | AA Involvement | 0.67 | 0.347 | −0.73 | 2.08 | 8.9% |

| Drinks per Drinking Day | −0.56 | 0.000 | −0.83 | −0.29 | Percent Days Abstinent | 0.13 | 0.000 | 0.07 | 0.19 | |||

| Forgiveness of Self (0–15) | AA Involvement | 0.11 | 0.467 | −0.18 | 0.39 | 3.6% | AA Involvement | 0.11 | 0.479 | −0.19 | 0.40 | 1.1% |

| Drinks per Drinking Day | −0.08 | 0.003 | −0.14 | −0.03 | Percent Days Abstinent | 0.01 | 0.085 | 0.00 | 0.03 | |||

| Forgiveness of Others (0–15) | AA Involvement | 0.33 | 0.005 | 0.10 | 0.56 | 2.9% | AA Involvement | 0.35 | 0.004 | 0.12 | 0.58 | 2.1% |

| Drinks per Drinking Day | −0.03 | 0.184 | −0.08 | 0.01 | Percent Days Abstinent | 0.00 | 0.975 | −0.01 | 0.01 | |||

Note. Table depicts results of 14 multi-level analyses, one for each spirituality outcome and each drinking predictor. Covariates included in each analysis but not shown include site, age, employment status, gender, race, marital status, and number of prior treatment episodes. Baseline levels of drinking, AA, and spirituality were entered into each model. “% Variance” is the percentage of the variance in the level of the outcome that is accounted for by the model above and beyond the unconditional growth model. Effect of predictors on slope were not significant for any spiritual/religious outcome.

Statistical Methods

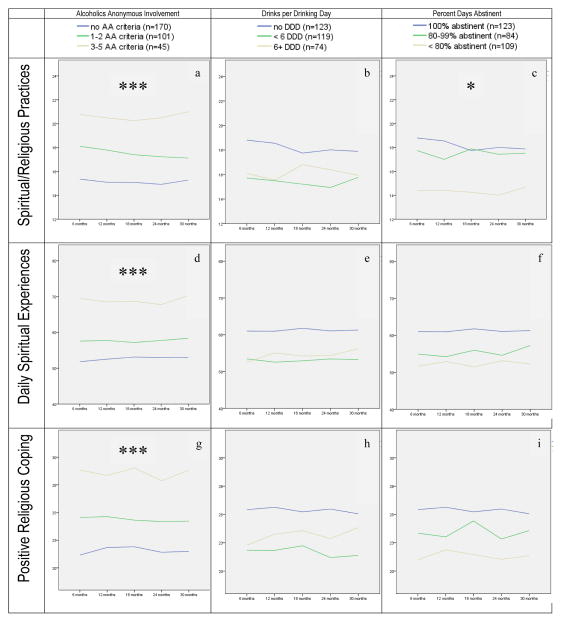

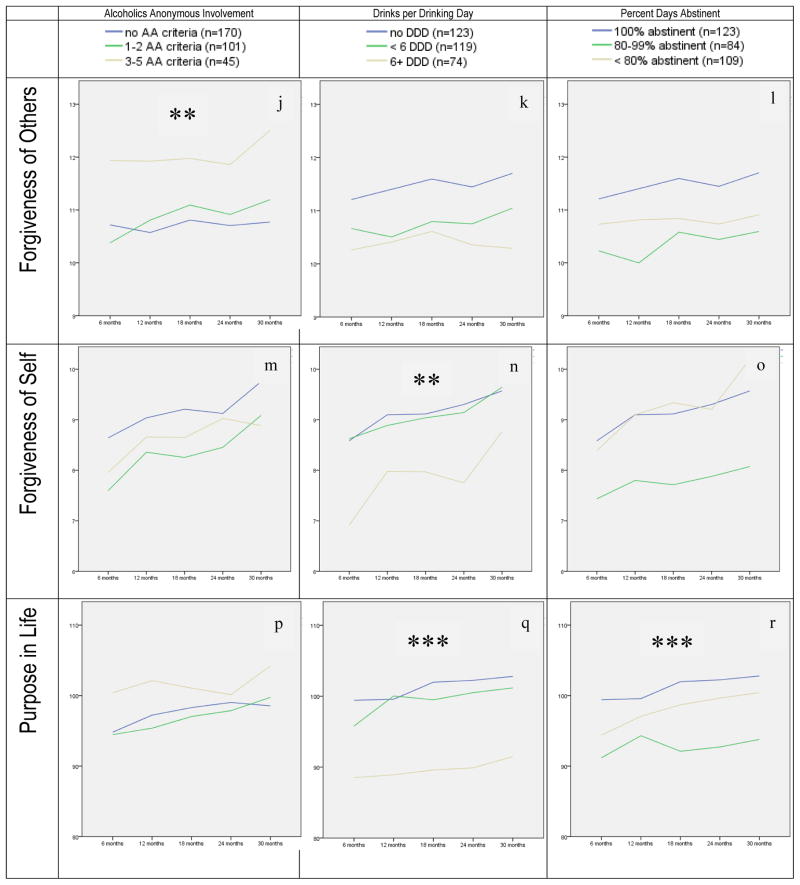

The unconditional means models were estimated to allow for calculation of the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), a ratio of between persons variation to between and within person variation. Next, the unconditional growth models were estimated. This enabled comparison with the first models to determine the percent of total variation within individuals that was accounted for by time. These models also tested whether outcomes changed significantly for the sample as a whole (i.e., the fixed effect of time), and whether the outcomes varied significantly between participants in their levels of spirituality at 6 months and in the ways they changed over time (i.e., random effects for the intercept and slope). The next set of models, the conditional growth models, took two forms: 1) the main effects of AA and drinking on average spiritual/religious levels over 6 to 30 months and 2) the interaction between AA and time, and drinking and time, to determine statistically significant differences in rate of change in spirituality/religiousness over 6 to 30 months based on 6-month AA involvement and 6-month drinking levels adjusted for baseline levels of these constructs. SPSS version 22 was used for all analyses. Multi-level modeling was employed using the “MIXED” command and restricted maximum likelihood was the method of estimation. All models included the baseline level of the outcome; conditional growth models additionally included baseline AA involvement, baseline drinking, and a set of clinical and demographic covariates (listed in Table 1) as well as the interaction of the covariates with time. Age and baseline levels of the outcome were mean centered. Finally, all spirituality outcomes over time were graphed based on low, medium, and high levels of the key predictors at 6 months (See Figure 2) to aid interpretation of the results of the statistical models.

Figure 2.

Figure 2a–r. Significant spirituality outcomes from 6–30 months based on 6-month levels of Alcoholics Anonymous involvement (column 1, drinking not controlled), drinks per drinking day (column 2, AA involvement not controlled), and percent days abstinent (column 3, AA involvement not controlled). Asterisks (*) represent statistical significance of the predictor at 6 months (column heading) on levels of the spirituality indicator (row heading) using multi-level modeling (see Table 1). * p<.05, ** p<.01, *** p<.001.

Missing Data

Multi-level modeling excludes cases with missing level 2 data (Woltman, Feldstain, MacKay, & Rocchi, 2012). In the current analyses, individuals excluded for missing level 2 data included those with missing baseline values for spirituality (n=6), and those who were absent at 6 months (when AA and drinking were assessed) (n=46). Those excluded from the analyses (n=52) and those included in the analyses (n=312) were compared on a set of baseline spirituality, clinical, and demographic criteria using independent samples t-tests and chi-square analyses. The two groups were similar on all variables with one exception. Those excluded had higher drinks per drinking day at baseline than those included 11.9 versus 9.1, t(362) = −2.30, p < .05. The SPSS MIXED procedure does not require that respondents are measured at the same set of occasions; therefore, all level 1 data can be included, even if some level 1 assessments are missing (Cnaan, Laird, & Slasor, 1997). Therefore, out of a total of 364 individuals who participated, the current study included 312 at baseline (85.7%), 312 at 6 months (85.7%), 285 at 12 months (78.3%), 272 at 18 months (74.7%), 268 at 24 months (73.6%), and 256 at 30 months (70.3%).

Results

The unconditional means model produced ICCs that ranged from 39.4% for negative religious coping to 59.1% for spiritual/religious practices and forgiveness of self, indicating that approximately one third to one half of the total variance observed in spirituality/religiousness was between persons. The percentage of total within-person variance explained by time ranged from 6.0% for forgiveness of others to 17.3% for daily spiritual experiences. As previously stated, spiritual outcomes were assessed from 6 to 30 months. Purpose in life, forgiveness of others, and forgiveness of self increased significantly over time (with beta coefficients of 0.9, 0.1 and 0.2, respectively) while negative religious coping decreased significantly over time (with a beta coefficient of −0.2). Spiritual/religious practices, daily spiritual experiences, and positive religious coping did not change significantly over time. As mentioned, the random effects of intercept and slope assessed whether levels and changes in spirituality between 6–30 months varied between participants. These assessments were statistically significant in all models with one exception. The random effects of slope were p<.10 for negative religious coping in the conditional growth models.

The conditional growth models explained between 1.1% and 13.4% of the variance in levels of spirituality/religiousness over and above the unconditional growth model. The percent variance accounted for by each model is listed in Table 1.

As displayed in Table 1, reduction in drinking at 6 months (as indicated by PDA, DDD, or both) was significantly associated with greater levels of purpose in life, forgiveness of self, and spiritual/religious practices over the course of 6 to 30 months, controlling for AA involvement and all of the covariates in the model. AA involvement at 6 months was significantly associated with greater levels of positive religious coping, daily spiritual experiences, forgiveness of others, and spiritual/religious practices, over the course of 6 to 30 months, controlling for drinking and all of the covariates in the model. Neither AA involvement nor either measure of drinking were significantly associated with negative religious coping over time. Neither AA involvement nor drinking at 6 months were significant predictors of slope in any spiritual/religious dimension from 6–30 months (see Figure 2a–r which illustrates that spirituality trajectories over time were roughly parallel despite different levels of 6 month AA and drinking, suggesting that levels of AA and drinking at 6 months did not differentially influence the slope for the spirituality outcomes).

Data visualization can provide additional insights into the results of statistical models (Singer & Willett, 2003). In Figure 2, each spirituality outcome with a statistically significant result is represented by a row and each predictor (AA involvement, drinks per drinking day, and percent days abstinent) by a column. Participants were grouped into categories by their status at 6 months to represent high, medium, and low levels of AA and drinking. Each group’s average was then drawn in Figure 2 as a trajectory between 6–30 months.

Statistically Significant Results

Figures 2a, 2d, and 2g suggest a linear relationship between AA involvement at 6 months and levels of subsequent spiritual/religious practices, daily spiritual experiences, and positive religious coping: as AA involvement increases, levels of these spirituality constructs increase. Figures 2n and 2q suggest that no drinking and lower levels of drinking intensity at 6 months (blue and green lines) were related to very similar patterns of self forgiveness and purpose in life over time while those drinking more than 6 drinks per drinking day at 6 months had lower levels of these constructs (beige line). Figure 2r depicts that while percent days abstinent at 6 months was a statistically significant predictor of purpose in life over time, the relationship does not appear to be linear: drinking most frequently (beige line) is associated with higher purpose in life scores than drinking with moderate frequency (green line). Figure 2c shows that those who were totally abstinent and those who had moderate levels of abstinence (blue and green lines) reported more frequent prayer/meditation over time than those drinking more than 20% of days (beige line).

Discussion

This study extends the current literature in several ways. It is the first study to report on the nature of longitudinal variance in seven dimensions of spirituality and religiousness for individuals with alcohol dependence who have diverse drinking goals at baseline. We found that some dimensions of spirituality change significantly over time in general (purpose in life, forgiveness of others, forgiveness of self, and negative religious coping) but that other dimensions do not change (spiritual/religious practices, daily spiritual experiences, and positive religious coping). Results of analyses of random effects indicated that each dimension of spirituality varied significantly between people both at 6 months (the “intercept”) and, for all variables with the exception of negative religious coping, varied significantly over time between 6–30 months in slope indicating much variation in the experience of spirituality in the sample.

Additionally, the findings contribute to what is known about spirituality and alcoholism by demonstrating that AA involvement tends to be related to some aspects of spirituality whereas drinking behaviors are related to different dimensions of spirituality. When we layered the information gleaned from the data visualization depicted in Figure 2 with the results of statistical analyses, what emerged was a link between AA and some dimensions of spirituality and a link between lower-intensity drinking and other dimensions of spirituality, described below in depth.

Spirituality and the 12 Steps

The statistically significant pattern between AA and spirituality depicted in Figures 2a, 2d, 2g, and 2j might be due to the strong association between these spirituality dimensions and concepts within the 12 steps. Positive religious coping, that is, viewing God as compassionate in times of stress, is relevant to AA’s 3rd step, which emphasizes trust in a benevolent higher power. Forgiving others is an explicit component of Steps 5, 8, and 10. For example, regarding Step 5, AA literature states, “Often it was while working on this Step with our sponsors or spiritual advisers that we first felt truly able to forgive others” (AA World Services, 1953, pp. 57–58). Spiritual/religious practices such as prayer and meditation are recommended in Step 11. Higher levels of daily spiritual experiences may be a function of more frequent prayer and meditation (Geary & Rosenthal, 2011).

Self Forgiveness and Purpose in Life

Self forgiveness has been negatively associated with guilt and shame (Hall & Fincham, 2005). Figures 2n and 2q suggests that having greater purpose in life and greater forgiveness of self seems possible both for those who are abstinent and those who drink less intensely. Individuals reporting no drinking at 6 months or an average of fewer than 6 drinks per drinking day at 6 months might not experience the high levels of guilt, shame, or self-recrimination that are associated with heavier drinking. Spending a great deal of time recovering from the effects of drinking and giving up important activities and are two of the diagnostic criteria for alcohol use disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Those who have quit or who drink less intensely should have more time available in which to engage in meaningful activities outside of drinking, which might result in greater purpose in life than is possible with concurrent heavy drinking. It is noteworthy that reduced drinking, and not only total abstinence, is associated with these forms of spiritual benefit.

The Qualitative Nature of Spirituality Associated with AA versus Drinking

Spirituality dimensions responsive to AA were related to God/Higher Power and have been shown to be responsive to learning (Geary & Rosenthal, 2011; Louchakova, 2005; Plante, 2009), while spirituality dimensions responsive to drinking were non-theistic and have been shown to be associated with maturation and experience (Hill, Sumner, & Burrow, 2014; Ishida, 2012; Ishida & Okada, 2011). Spiritual practices and daily spiritual experiences have proven responsive to intervention (Geary & Rosenthal, 2011; Louchakova, 2005; Plante, 2009), suggesting that they are amenable to learning. AA is an environment in which learning about spirituality arguably takes place, either by the modeling of other members, actual prayer and meditation practices within meetings, or instructions in program literature. In contrast, research indicates that purpose in life increases as the result of maturation and experience, versus learning. For example, experiential and maturational factors, such as having early caregivers who listened empathically, can lay the foundation for the development of higher life purpose and meaning later in life (Hill et al., 2014; Ishida, 2012; Ishida & Okada, 2011). Two of the spiritual/religious dimensions associated with AA involvement reference God in their questionnaire items (the daily spiritual experiences questionnaire references God in 8 of 16 items; the positive religious coping instrument references God in 7 of 10 items), again drawing associations to the 12 steps which reference God or a Higher Power. None of the instruments which assessed the forms of spirituality that were significantly associated with drinking (spiritual/religious practices, purpose in life, forgiveness of self) mention God or a Higher Power in any of the items.

The Slope of Spirituality

Neither AA nor drinking at 6 months were associated with differences in slope for any spirituality outcome. However, conditional growth models revealed significant random effects of slope and intercept even after controlling for AA involvement, drinking, and key covariates for all spirituality variables except negative religious coping. Negative religious coping results depicted significant variation between subjects at the 6-month assessment but no significant difference between subjects in trajectory from 6–30 months. On average, participants declined in negative religious coping over time. With the exception of the slope of negative religious coping, there was significant variation still present even in our final models which could be explained by additional factors which we did not measure. Future research should identify other predictors responsible for the levels and slope observed in the spirituality outcomes.

Implications for Practice

The findings suggest that AA involvement is related to forms of spirituality which are promoted in the 12 steps. In addition, those who are abstinent and those who drink less intensely at 6 months sustain higher levels of self forgiveness and purpose in life over time than the heaviest drinkers. Clinicians making referrals to AA might employ these findings to explain the kinds of spiritual change that might come about from increasing involvement with AA to enable clients to make choices about recovery pathways that will be agreeable to them. Clinicians advising clients who have harm-reduction or moderation objectives might use these findings to show that cutting back on drinking can be associated with positive changes such as higher purpose in life and greater self forgiveness. Therefore, the results of the current study can be used by clinicians, recovery coaches, and others to help clients to better understand the nature of spirituality that is and is not dependent upon AA and/or complete abstinence to make decisions about options that would be a good fit for the person.

Should a client become highly involved in AA (Figure 2, beige lines in the first column) and achieve abstinence (Figure 2, blue line in the second and third columns), the results of this study suggest that such a person might experience higher levels of six of the spirituality indicators since each of the behaviors (AA and drinking) contributed to spirituality in a positive manner. This idea was not explicitly tested in the current study but is a worthwhile question for future research. Taken together, greater spiritual/religious practices, more frequent daily spiritual experiences, increased consideration of God as helpful in times of stress, greater life purpose, and greater forgiveness of self and others should have a positive impact on quality of life in recovery, which would reinforce abstinence and discourage relapse.

Limitations and Future Research

This study comprised individuals with varying levels of AA involvement and varying drinking behaviors and statistically controlled for these differences. The study did not directly compare AA members with individuals who were moderating their drinking. A carefully designed study which explicitly compares those in AA with similar participants in different treatment modalities could be more robust in evaluating the results of treatment on spirituality. Such a study would be useful in confirming and clarifying our findings.

In past work, studies of AA, spirituality, and drinking have varied in their temporal order, however, it is likely they are mutually reinforcing. Further work can clarify the direction of causal influence and ascertain accurate time lags. Study participants were primarily of European-American heritage, which limits the study’s generalizability to more diverse ethnic and racial groups of individuals with alcohol use disorders. Individuals excluded from the analyses had higher drinks per drinking day than those retained. While the heaviest drinkers are often lost to follow-up in longitudinal studies, their exclusion presents a limitation of the current study’s generalizability to all with alcohol use disorders.

Finally, it seems there is a subsample of individuals with alcohol use disorders who drink less intensely and report greater purpose in life and self-forgiveness. Future research can further clarify this trend and determine the clinical and demographic characteristics that are associated with this behavior pattern. Criteria which defined the groups depicted in Figure 2 were selected to produce approximately equal groups but it is important to note that the way that moderate drinking intensity is depicted in the graphs (as more than one but less than six drinks per drinking day) still represents a range of drinking behavior that includes both moderate and heavy drinking. The 2010 U.S. Dietary Guidelines recommend a maximum of one drink per day for women and two for men (U.S. Department of Agriculture & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010); therefore, drinking less than six drinks per drinking day does not depict successful “moderate” drinking by these standards. Future research should clarify the experience of individuals diagnosed with alcohol use disorders who maintain their drinking within the U.S. Dietary Guidelines, and the association of such a pattern of drinking with spirituality over time. The term moderated recovery has been suggested for those who had previously met criteria for substance dependence but have since sustained a pattern of reduced drinking and reduced alcohol-related problems (White, 2007a). The term partial recovery may apply to such persons if their ability to drink moderately is sustained over time, if alcohol-related problems continue to lessen, and if there is evidence of “enhanced global … health” including ontological, or spiritual, wellness (White, 2007a, p. 236). The results of the current study depict that such spiritual health might take the form of purpose in life and self-forgiveness.

Research on the ways in which spirituality is learned in AA would make important contributions. It would also be useful to determine whether teaching spiritual practices, or using the therapeutic relationship to develop more relational or developmental aspects of spirituality, would ultimately impact drinking outcomes. This study found that there were differences in the slope of some dimensions of spirituality unexplained by AA and drinking; future research should identify other predictors responsible for change over time observed in spirituality outcomes.

References

- AA World Services. Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions. New York: AA World Services; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5. 5. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins RG, Hawdon JE. Religiosity and participation in mutual-aid support groups for addiction. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;33(3):321–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.07.001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cnaan A, Laird NM, Slasor P. Using the general linear mixed model to analyse unbalanced repeated measures and longitudinal data. Statistics in Medicine. 1997;16(20):2349–2380. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19971030)16:20<2349::aid-sim667>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crumbaugh JC. Cross-validation of purpose-in-life test based on Frankl’s concepts. Journal of Individual Psychology. 1968;24:74–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crumbaugh JC, Maholick LT. An experimental study in existentialism: The psychometric approach to Frankl’s concept of noogenic neurosis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1964;20:200–207. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(196404)20:2<200::aid-jclp2270200203>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer Institute. Multidimensional measurement of religousness/spirituality for use in health research: A report of the Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging working group. Kalamazoo, MI: Author; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty MT, Kurtz E, White W, Larson A. An Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis of Secular, Spiritual, and Religious Pathways of Long-Term Addiction Recovery. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2014;32(4):337–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347324.2014.949098. [Google Scholar]

- Frankl V. The Will to Meaning: Foundations and Applications of Logotherapy. New York, NY: New American Library; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman SG. Alcoholics Anonymous, Without the Religion. The New York Times. 2014 Feb 21; Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/22/us/alcoholics-anonymous-without-the-religion.html.

- Galanter M, Dermatis H, Post S, Sampson C. Spirituality-based recovery from drug addiction in the twelve-step fellowship of Narcotics Anonymous. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2013;7(3):189–195. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31828a0265. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0b013e31828a0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanter M, Dermatis H, Santucci C. Young people in Alcoholics Anonymous: The role of spiritual orientation and AA member affiliation. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2012;31(2):173–182. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2012.665693. https://doi.org/10.1080/10550887.2012.665693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanter M, Dermatis H, Stanievich J, Santucci C. Physicians in long-term recovery who are members of Alcoholics Anonymous. The American Journal on Addictions. 2013;22(4):323–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.12051.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.12051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geary C, Rosenthal SL. Sustained impact of MBSR on stress, well-being, and daily spiritual experiences for 1 year in academic health care employees. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2011;17(10):939–944. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0335. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2010.0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granfield R, Cloud W. Social Context and “Natural Recovery”: The Role of Social Capital in the Resolution of Drug-Associated Problems. Substance Use & Misuse. 2001;36(11):1543–1570. doi: 10.1081/ja-100106963. https://doi.org/10.1081/JA-100106963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JH, Fincham FD. Self–Forgiveness: The Stepchild of Forgiveness Research. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2005;24(5):621–637. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2005.24.5.621. [Google Scholar]

- Hill PL, Sumner R, Burrow AL. Understanding the pathways to purpose: Examining personality and well-being correlates across adulthood. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2014;9(3):227–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.888584. [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Musick MA, Ellison CG, George LK, Krause N, Ory MG, … Williams DR. Measuring multiple dimensions of religion and spirituality for health research: Conceptual background and findings from the 1998 General Social Survey. Research on Aging. 2003;25(4):327–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027503025004001. [Google Scholar]

- Ishida R. Purpose in life (ikigai), a frontal lobe function, is a natural and mentally healthy way to cope with stress. Psychology. 2012;3(3):272–276. [Google Scholar]

- Ishida R, Okada M. Factors influencing the development of “purpose in life”and its relationship to coping with mental stress. Psychology. 2011;2(1):29–34. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2011.21005. [Google Scholar]

- Krentzman AR, Cranford JA, Robinson EAR. Multiple dimensions of spirituality in recovery: A lagged mediational analysis of Alcoholics Anonymous’ principal theoretical mechanism of behavior change. Substance Abuse. 2013;34(1):20–32. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2012.691449. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2012.691449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louchakova O. On advantages of the clear mind: Spiritual practices in the training of a phenomenological researcher. The Humanistic Psychologist. 2005;33(2):87–112. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15473333thp3302_2. [Google Scholar]

- Matzger H, Kaskutas LA, Weisner C. Reasons for drinking less and their relationship to sustained remission from problem drinking. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2005;100(11):1637–1646. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01203.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauger PA, Perry JE, Freeman T, Grove DC, McBride AG, McKinney KE. The measurement of forgiveness: Preliminary research. Journal of Psychology and Christianity. 1992;11(2):170–180. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR. Addiction and spirituality. Substance Use & Misuse. 2013;48:1258–1259. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.799024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morjaria-Keval A. Religious and Spiritual Elements of Change in Sikh Men with Alcohol Problems. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2006;5(2):91–118. doi: 10.1300/J233v05n02_06. https://doi.org/10.1300/J233v05n02_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morjaria-Keval A, Keval H. Reconstructing Sikh Spirituality in Recovery from Alcohol Addiction. Religions. 2015;6(1):122–138. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel6010122. [Google Scholar]

- Owen PL, Slaymaker V, Tonigan J, McCrady BS, Epstein EE, Kaskutas LA, … Miller W. Participation in Alcoholics Anonymous: intended and unintended change mechanisms. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27(3):524–532. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000057941.57330.39. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ALC.0000057941.57330.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament K. The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, Practice. 1. New York: The Guilford Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament K, Smith BW, Koenig HG, Perez L. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1998;37(4):710–724. https://doi.org/10.2307/1388152. [Google Scholar]

- Plante TG. Spiritual practices in psychotherapy: Thirteen tools for enhancing psychological health. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson EAR, Cranford JA, Webb JR, Brower KJ. Six-month changes in spirituality, religiousness, and heavy drinking in a treatment-seeking sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(2):282–290. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.282. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2007.68.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson EAR, Krentzman AR, Webb JR, Brower KJ. Six-month changes in spirituality and religiousness in alcoholics predict drinking outcomes at nine months. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72(4):660–668. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. 1. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, USA; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L, Brown J, Leo GI, Sobell MB. The reliability of the Alcohol Timeline Followback when administered by telephone and by computer. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1996;42(1):49–54. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01263-x. https://doi.org/10.1016/0376-8716(96)01263-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L, Sobell MB. Timeline Follow-Back. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption. Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. Retrieved from http://link.springer.com.ezp2.lib.umn.edu/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4612-0357-5_3. [Google Scholar]

- Strobbe S, Cranford JA, Wojnar M, Brower KJ. Spiritual awakening predicts improved drinking outcomes in a Polish treatment sample. Journal of Addictions Nursing. 2013;24(4):209–216. doi: 10.1097/JAN.0000000000000002. https://doi.org/10.1097/JAN.0000000000000002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan J, Connors GJ, Miller WR. Alcoholics Anonymous Involvement (AAI) scale: Reliability and norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1996;10(2):75–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.10.2.75. [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan J, Rynes KN, McCrady BS. Spirituality as a change mechanism in 12-step programs: A replication, extension, and refinement. Substance Use & Misuse. 2013;48(12):1161–1173. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.808540. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2013.808540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood LG, Teresi JA. The daily spiritual experience scale: Development, theoretical description, reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;24(1):22–33. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 7. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- White W. Addiction recovery: Its definition and conceptual boundaries. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007a;33(3):229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.04.015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White W. The new recovery advocacy movement in America. Addiction. 2007b;102(5):696–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01808.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White W, Kurtz E. A message of tolerance and celebration: The portrayal of multiple pathways of recovery in the writings of Alcoholics Anonymous co-founder Bill Wilson. 2010 Retrieved from www.williamwhitepapers.com.

- Woltman H, Feldstain A, MacKay J, Rocchi M. An introduction to hierarchical linear modeling. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology. 2012;8(1):52–69. [Google Scholar]