Abstract

The aim of the present study was to examine the protective effects and mechanism of sika deer (Cervus nippon Temminck) velvet antler polypeptides (VAPs) against MPP+ exposure in the SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell line. MPP+ cytotoxicity and the protective effects of VAPs on the SH-SY5Y cells were determined using an MTT assay. Cell apoptosis and mitochondrial membrane potential were detected using Hoechst 33342 and Rhodamine123 staining, respectively. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress-related reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in the SH-SY5Y cells was detected using 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate fluorescent probes. The expression levels of proteins, including caspase-12, glucose regulated protein 78 (GRP78), CCAAT/enhancer binding protein homologous protein (CHOP) and phosphorylated c-Jun N-terminal kinase (p-JNK) were detected using western blot analysis. The results showed that the half inhibitory concentration of MPP+ at 72 h was 120.9 µmol/l, and that 62.5, 125, and 250 µg/ml concentrations of VAPs protected the SH-SY5Y cells under MPP+ exposure. When exposed to 120.9 µmol/l MPP+, changes in cell nucleus morphology, mitochondrial membrane potential and intracellular ROS were observed. VAPs at concentrations of 62.5, 125, 250 µg/ml reduced this damage. Western blot analysis showed that protein expression levels of caspase-12, GRP78 and p-JNK were upregulated in the SH-SY5Y cells exposed to 120.9 µmol/l MPP+ for 72 h. In addition, 62.5, 125, and 250 µg/ml VAPs downregulated the expression levels of caspase-12 and p-JNK in a concentration- dependent manner, particularly the p-JNK pathway. The effects of VAPs on GRP78 and CHOP were weak. In conclusion, MPP+-induced SH-SY5Y cell death may be linked to ER stress. VAPs prevented MPP+-induced SH-SY5Y cell death by affecting the p-JNK pathway and caspase-12-mediated apoptosis. These findings assist in understanding the mechanism underlying the protective effect of VAPs on neurons.

Keywords: velvet antler polypeptides, neuroblastoma, endoplasmic reticulum stress, apoptosis, glucose regulated protein 78, caspase-12, c-Jun N-terminal kinase

Introduction

Velvet antler polypeptides (VAPs) of sika deer (Cervus nippon Temminck) are extracts obtained from the traditional Chinese medicine, sika deer velvet antler. VAPs have several biological benefits, including the perfect regeneration of neurons, blood vessels, connective tissue, cartilage and bones (1–3), in addition to immunomodulatory effects (4). However, their neuroprotective effects in neurodegenerative diseases remain to be reported.

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a general neurodegenerative disease affecting the aged population worldwide. The pathological features of PD involve the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantial nigra (5,6), causing decreased dopamine levels in the striata. Until now, the mechanism underlying the onset of PD remained to be fully elucidated. Studies have revealed the types of mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of PD, including mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress and the ubiquitin-proteasomal pathway (7–10). Misfolded proteins associated with endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress have been investigated in detail for their actions in PD-associated neuronal cell death (11,12). Accumulated misfolded proteins cause dysregulation of ER homeostasis, triggering ER stress. ER stress initiates the conserved cellular process of the unfolded protein response (UPR) to maintain a stable intracellular environment (13,14). In this process, a molecular chaperone, glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), enables misfolded proteins to restore their naive structures and functions. If UPR protracts or fails to repair misfolded proteins, programmed ER stress-associated cell death occurs. The cell death pathways include the downstream PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) and type I transmembrane protein kinase/endoribonuclease (IRE-1) signaling pathways (15,16). In addition, ER stress-associated cell apoptosis involves changes in mitochondrial membrane potential at the initial stage of apoptosis.

Based on the above understanding, the 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+), a neurotoxin most commonly used for establishment of PD models in vitro, has been utilized to establish a PD model in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells (17–19). In the present study, SH-SY5Y cells exposed to MPP+ were selected for comparison of the features of ER stress-mediated cell death. The neuroprotective effect of sika deer velvet antler polypeptides (VAPs) was evaluated to develop a potential therapeutic agent for the treatment of PD.

Materials and methods

VAPs

The VAPs of sika deer (Cervus nippon Temminck) were extracted according to the method described previously (20). Briefly, 100 g fresh sika deer velvet antler (Institute of Special Animal and Plant Sciences of CAAS, Changchun, China) were cut into 0.5 cm-thick sections, washed with cold distilled water to remove blood, and then homogenized in ice-cold acetic acid solution (pH 3.5) using a colloid mill (Shanghai Nuoni Light Industrial Machinery Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The collected homogenates were centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and the supernatants were collected. Following ammonium sulfate precipitation, dialysis was performed in a Spectra/Por dialysis membrane 1000 Da (Spectrum Laboratories, Inc., Rancho Dominguez, CA, USA). Gel filtration was performed on a Sephadex G-50 column (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) to remove salts in the VAP extracts. The VAPs were lyophilized and these VAPs consisted of a single chain of 32 amino-acid residues: VLSAT DKTNV LAAWG KVGGN APAFG AEALE RM (20).

Cell culture

The SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells were donated by the Second Hospital of Jilin University (Changchun, China) and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) containing 10% fetal calf serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The present study was approved by the Experimental Animal Management Committee of Jilin University (Changchun, China) and the Experimental Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of Jilin University. All animal care and experimental procedures were in accordance with the Administration of Affairs Concerning Experimental Animals of the State Science and Technology Commission of the People's Republic of China (1988) (21,22).

MTT assay

Cell viability was measured using an MTT assay. Briefly, the SH-SY5Y cells were seeded into a 96-well plate with 5,000 cells per well. The half inhibitory concentration (IC50) of MPP+ in the SH-SY5Y cell lines was measured, which was 120.9 µmol/l. The cells were subsequently exposed to VAPs at concentrations of 0, 15.6, 31.2, 62.5, 125, 250, 500, 1,000 and 2,000 µg/ml, respectively, together with 120.9 µmol/l MPP+ for 72 h at 37°C. Subsequently 10 µl MTT solution (5 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was added into each well for a further 4 h. Finally, the medium was discarded and 200 µl DMSO was added into each well to dissolve the formazan. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a microplate reader (Tecan Austria GmbH, Grödig, Austria) and cellular viability was determined.

Hoechst 33342 staining

Hoechst 33342 is a fluorescent probe, which binds to the nucleus. The normal nuclei and condensed nuclei of apoptotic cells are distinguishable using Hoechst 33342 staining. In the present study, the SH-SY5Y cells were plated in a 24-well plate at a density of 105 cells per well. Following incubation overnight, the cells were exposed to 0, 62.5, 125 and 250 µg/ml VAPs, with or without 120.9 µmol/l MPP+ for 72 h. The cells were then incubated with 10 µg/ml Hoechst 33342 in the dark for 15 min at 37°C, following which they were washed 3 times with PBS and fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde. Images were captured with a fluorescent microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). A total of 200 cells were counted in each image and the numbers of apoptotic cells were calculated using Image-Pro Plus software version 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Inc, Rockville, MD, USA) in each image for measurement of apoptotic rate.

Rhodamine123 staining

Rhodamine123 is a fluorescent probe, which is used in the determination of mitochondrial membrane potential. The procedure for the Rhodamine123 staining was similar to that of the Hoechst 33342 staining section, although the cells were incubated with 0.1 µg/ml Rhodamine123. Images were captured with a fluorescent microscope (Olympus Corporation). The fluorescent intensity of each image was measured using ImageJ software version 1.37 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MA, USA).

2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) staining. H2DCFDA is a fluorescent probe used to detect the production of ROS. The procedure used for the H2DCFDA staining in the present study was similar to that described above for the Hoechst 33342 staining section, however, the cells were incubated with 10 µmol/l H2DCFDA in the dark for 30 min at 37°C. The fluorescence intensity of the images was analyzed, as described for the Rhodamine123 staining above.

Western blot analysis

The SH-SY5Y cells were plated in a 6-well plate at a density of 2×105 cells/well. The cells were exposed to 0, 62.5, 125 and 250 µg/ml VAPs with 120.9 µmol/l MPP+ for 72 h. The expression of ER stress-related proteins was then detected using western blot analysis. Briefly, the cells were precipitated and suspended in ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer containing 1 mmol/l phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Following centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C, the supernatants were collected. The protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay. The proteins were denatured at 100°C for 5 min. Equal amounts of extracted protein samples (40 µg) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were then incubated with the following primary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Rockford, IL, USA) at 4°C overnight: Anti-phosphorylated (p)-JNK/SAPK chicken polyclonal antibody (1:1,000; cat no. PA1-9594), anti-CHOP mouse monoclonal antibody (1:1,000; cat no. MA1-250), anti-Glucose regulated protein rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:100; cat no. PA5-40336), anti-caspase-12 rat monoclonal antibody (1:1,000; cat no. MA1-24704) or anti-β-actin antibody (1:5,000; cat no. bs-0061R; Beijing Biosynthesis Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The membranes were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti- mouse/rabbit immunoglobulin G (1:100; cat no. PV-6000; Beijing Zhong Shan-Golden Bridge Biological Technology Co. Ltd, Beijing, China) at room temperature for 2 h. Protein bands were visualized using SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). Blots were semi-quantified by densitometry using Image-Pro Plus software version 6.0. β-actin was used as the loading control.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of 3 independent experiments. SPSS software version 13.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The statistical significance of the differences between groups was assessed using one-way analysis of variance was performed followed by a post hoc Dunn's test for multiple comparisons. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

VAPs protect SH-SY5Y cells against MPP+-induced cytotoxicity

To measure the protective effects of VAPs against MPP+-induced cytotoxicity, the viability of SH-SY5Y cells were determined using an MTT assay. The IC50 of MPP+ reagent in SH-SY5Y cells was 120.9 µmol/l at 72 h. Following exposure to 120.9 µmol/l MPP+, SH-SY5Y cell viability was markedly decreased. A series of VAP concentrations was then used to treat SH-SY5Y cells, together with 120.9 µmol/l MPP+. Concentrations in the range of 0–500 µg/ml protected the SH-SY5Y cells from MPP+-induced damage, and the protective effects of 125, 250 and 500 µg/ml VAPs were significant (P<0.05; Fig. 1). High VAP concentrations (1,000 and 2,000 µg/ml) resulted in poor protection. Therefore, VAP concentrations of 62.5, 125 and 250 µg/ml were used in the subsequent experiments.

Figure 1.

Protective effects of VAPs against MPP+-induced cytotoxicity in SH-SY5Y human neuroblast cells. (A) Half inhibitory concentration of MPP+ was 120.9 µmol/l at 72 h. (B) SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 0, 15.6, 31.2, 62.5, 125, 250, 500, 1,000 and 2,000 µg/ml VAPs together with 120.9 µmol/l MPP+. VAPs concentrations of 125, 250 and 500 µg/ml significantly increased cell viability. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (n=3). *P<0.05, compared with MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells. MPP+, 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium; VAPs, velvet antler polypeptides.

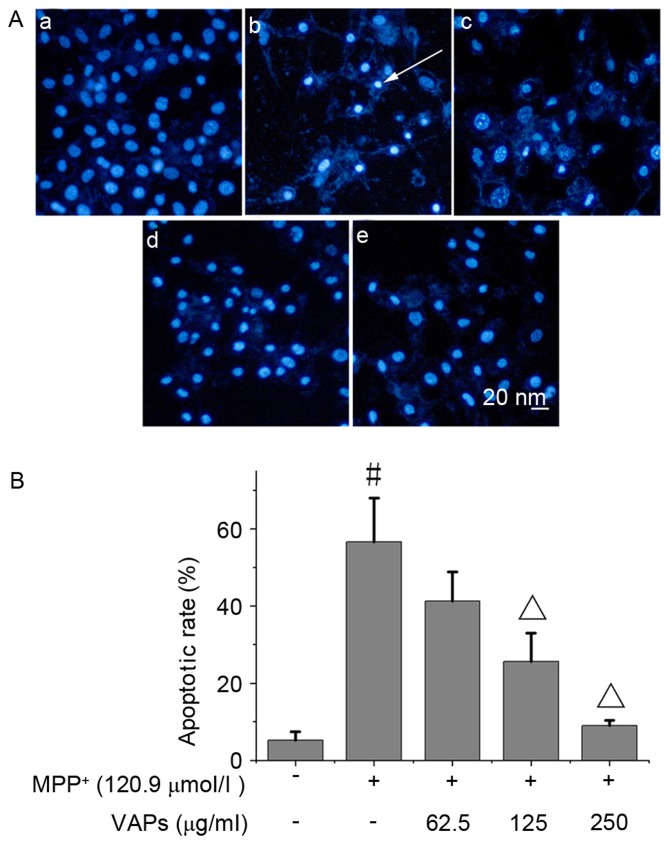

VAPs suppress MPP+-induced apoptosis

The normal nuclei of SH-SY5Y cells are shown in Fig. 2Aa. Following exposure of cells to 120.9 µmol/l MPP+, marked nuclear condensation was observed in the SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 2Ab), indicating severe apoptosis. VAPs at concentrations of 62.5, 125 and 250 µg/ml (Fig. 2Ac-e) relieved cell apoptosis in a concentration-dependent manner, of which 125 and 250 µg/ml VAPs decreased the number of apoptotic cells significantly (P<0.05; Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

VAPs inhibit MPP+-induced apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells. (Aa) No apoptosis was observed in normal cells. (Ab) Following exposure to 120.9 µmol/l MPP+, cells exhibited nuclear condensation and nuclear fragmentation. Exposure to VAPs concentrations of (Ac) 62.5, (Ad) 125 and (Ae) 250 µg/ml with 120.9 µmol/l MPP+ reduced the apoptotic rates to 40.2±6.9, 25.7±7.4 and 9.0±1.4%, respectively. The white arrow indicates apoptotic cells. (B) Apoptotic rate of the cells following exposure to 120.9 µmol/l MPP+ was 55.7±11.4%. #P<0.05, compared with the normal control; ΔP<0.05, compared with the MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells. Scale bar, 20 nm. MPP+, 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium; VAPs, velvet antler polypeptides.

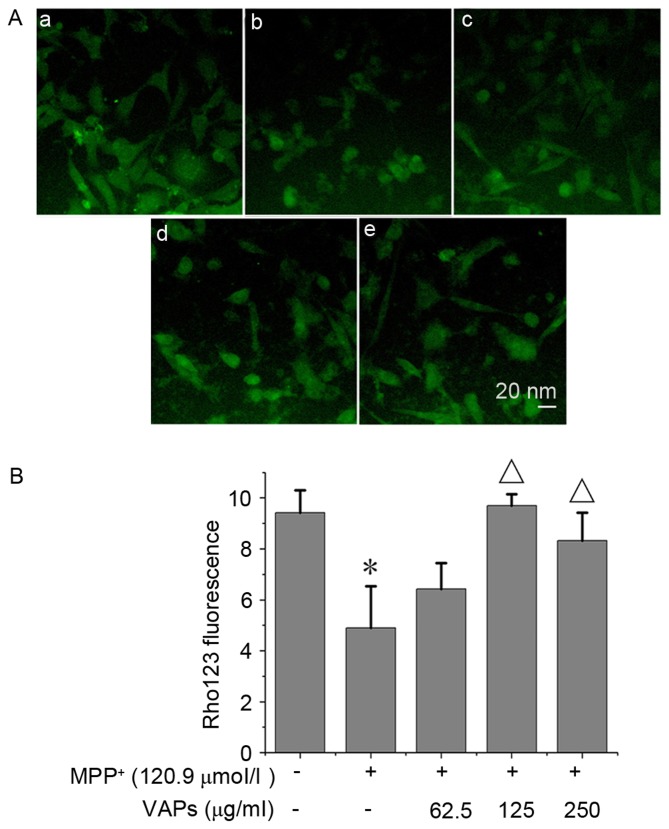

VAPs decrease MPP+-induced mitochondrial membrane potential dissipation

The normal nuclei presented with bright intracellular fluorescence, as shown in Fig. 3Aa. Following exposure to 120.9 µmol/l MPP+, dissipation of mitochondrial membrane potential was observed in SH-SY5Y cells, and this collapse was identified by a decrease of Rhodamine123 fluorescent intensity (Fig. 3Ab). Treatment with VAPs at concentrations of 62.5, 125 and 250 µg/ml (Fig. 3Ac-e) restored the mitochondrial membrane potential, partially or completely, in a concentration-dependent manner, of which 125 and 250 µg/ml restored the mitochondrial membrane potential significantly (P<0.05; Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

VAPs inhibit MPP+-induced collapse of MMP in SH-SY5Y cells. (Aa) Normal cells served as normal controls. (Ab) 120.9 µmol/l MPP+ induced the loss of MMP. VAPs concentrations of (Ac) 62.5, (Ad) 125 and (Ae) 250 µg/ml attenuated MPP+-induced loss of MMP. (B) Rhodamine 123 fluorescence was also detected using NIH Image J software. *P<0.05, compared with normal controls; ΔP<0.05, compared with the MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells. MPP+, 1-methyl-4- phenylpyridinium; VAPs, velvet antler polypeptides; MMP, mitochondria membrane potential.

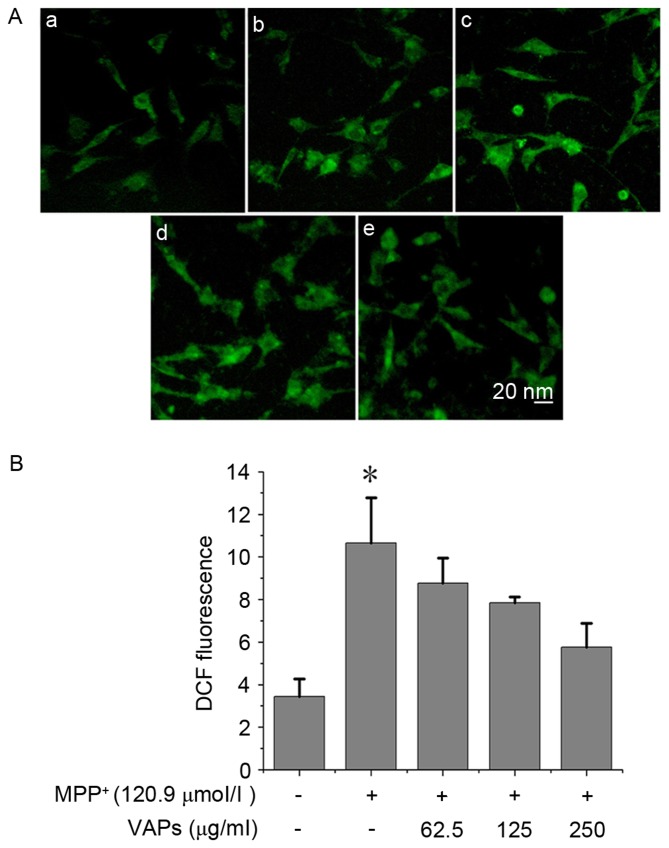

VAPs suppress MPP+-induced ROS production

Compared with normal SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 4Aa), marked ROS production was observed in the MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 4Ab). VAP concentrations of 62.5, 125 and 250 µg/ml (Fig. 4Ac-e) reduced the level of intracellular ROS in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

VAPs prevent against MPP+-induced ROS production in SH-SY5Y cells. (Aa) Normal cells were used as normal controls. (Ab) 120.9 µmol/l MPP+ induced intracellular ROS production, characterized by increased H2DCFDA metabolites showing DCF fluorescence. VAPs concentrations of (Ac) 62.5, (Ad) 125 and (e) 250 µg/ml reduced the levels of ROS in MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells. (B) Reduction in ROS occurred in a concentration-dependent manner. *P<0.05, compared with the normal controls. MPP+, 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium; VAPs, velvet antler polypeptides; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

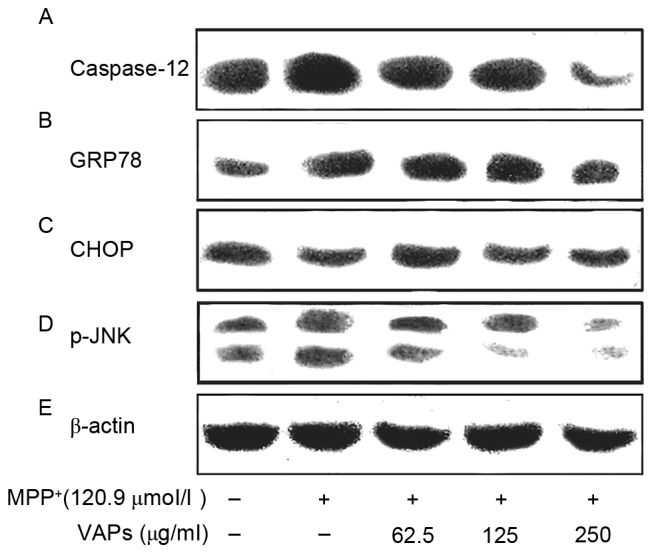

Expression of proteins

The SH-SY5Y cells were exposed to MPP+ at the same time as VAPs were added. The expression levels of ER stress-related proteins CHOP, GRP78, caspase-12 and p-JNK were detected using western blot analysis. The results of the western blot analysis are shown in Fig. 5 and Table I. Under exposure of MPP+ alone, the expression levels of caspase-12, GRP78 and p-JNK in the SH-SY5Y cells were upregulated, compared with those in the normal control, although no difference was observed in the expression of CHOP. VAPs intervention at concentrations of 62.5, 125 and 250 µg/ml reduced the expression levels of p-JNK in a concentration-dependent manner. The levels of GRP78 in the 62.5, 125 and 250 µg/ml VAP groups were marginally reduced, compared with those in the MPP+-only group, in a concentration- dependent manner, however, they were higher than those in the normal control. The levels of caspase-12 in the 62.5, 125 and 250 µg/ml VAP groups were downregulated, compared with in the MPP+-only group in a concentration-dependent manner. The level of caspase-12 in the 250 µg/ml VAP group was downregulated, compared with that in the MPP+-only group control. VAP treatment had no significant effect on the expression of CHOP (Fig. 5 and Table I).

Figure 5.

Western blot analysis of the effects of VAPs on ER stress-related proteins, (A) caspase-12, (B) GRP78, (C) CHOP, (D) p-JNK and (E) β-actin in SH-SY5Y cells exposed to MPP+. Cells were incubated with 62.5, 125 and 250 µg/ml VAPs together with 120.9 µmol/l MPP+. MPP+ upregulated the protein expression levels of caspase-12, GRP78 and p-JNK. VAPs downregulated the expression of p-JNK in SH-SY5Y cells in a concentration-dependent manner. Levels of caspase-12 decreased rapidly up to a VAPs concentration of 250 µg/ml. Levels of GRP78 showed no marked reduction following exposure to VAPs. No changes in the expression of CHOP expressions were observed. MPP+, 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium; VAPs, velvet antler polypeptides; GRP78, glucose regulated protein 78; CHOP, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein homologous protein; p-JNK, phosphorylated c-Jun N-terminal kinase.

Table I.

Results of western blot analysis showing relative grayscales, compared with β-actin.

| 120.9 µmol/l MPP+ | VAPs (µg/ml) | Caspase-12a | GRP78 | CHOP | p-JNKa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| − | − | 1.23 | 0.55 | 0.87 | 0.53 |

| + | − | 1.62 | 1.13 | 0.78 | 0.63 |

| + | 62.5 | 1.51 | 1.09 | 0.88 | 0.47 |

| + | 125.0 | 1.14 | 0.85 | 0.71 | 0.27 |

| + | 250.0 | 0.61 | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.23 |

P<0.05, vs. cells treated with 120.9 µmol/l MPP+. Significant change in protein levels was observed in VAPs in a concentration-dependent manner. MPP+, 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium; VAPs, velvet antler polypeptides; GRP78, glucose regulated protein 78; CHOP, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein homologous protein; p-JNK, phosphorylated c-Jun N-terminal kinase.

Discussion

With the problems associated with an increasingly aging population, PD has become a socio-economic burden on society. Although certain pathological mechanisms are involved in the onset of the sporadic form of PD, dopamine replacement therapy (DRT) is the most effective treatment for PD (23,24). Levodopa (L-dopa) is the primary medicine used for the treatment of behavior disorders in patients with PD. The molecular mechanism of L-dopa treatment involves supplying dopamine to patients with PD suffering dopaminergic neuron loss (25–27). However, DRT is unable to prevent the apoptosis of dopaminergic neurons, and DRT itself has adverse side-effect profiles, including on-off phenomena, resulting in a requirement for increased L-dopa dosage (28–30). Therefore, novel therapeutic agents with lower adverse effects are required for the treatment of PD.

In the present study, VAPs separated from silka deer velvet antler were used to protect SH-SY5Y human dopaminergic neuroblastoma cells from cytotoxicity induced by MPP+ intervention. This was based on the rapid growth feature and abundance of growth factors of velvet antler (31–34). Studies have shown that VAPs and velvet antler proteins facilitate the growth rate of neural stem cells, hippocampal neuronal cells and PC12 cells (35–37). VAPs also exhibit neuroprotective effects against β-amyloid via regulating the expression of caspase-3 (38). However, there are no reports regarding the potential protective effect of VAPs in a PD model. The present study observed a decrease in cell survival, collapse of mitochondrial membrane potential and elevated intracellular ROS in SH-SY5Y cells in response to MPP+ exposure. The VAPs protected the SH-SY5Y cells against MPP+-induced cell death, mitochondrial potential collapse and ROS production, in a concentration- dependent manner. These data substantiated the protective activity of VAPs in neuronal cells. These results are the first, to the best of our knowledge, to show the neuroprotective effects of VAPs against a neurotoxin-induced PD model in vitro. In the present study, the cytotoxic effect of MPP+ at 72 h was determined as 120.9 µmol/l and the protective effects of VAPs were evident at 72 h.

Studies have shown that ER stress has a causative role in the pathogenesis of PD (7,39,40). This has been confirmed by post-mortem investigations in patients with PD (41,42). A mild, early ER stress response is essential for cell defense against stimuli and misfolded/unfolded protein processing. However, prolonged ER stress leads to the activation of UPR and triggers cell death downstream signaling pathways, including the PERK, ATF6 and IRE-1 pathways. In turn, ER stress-related markers, for example, caspase-12, GRP 78, CHOP and JNK, are activated (43,44). In the present study, SH-SY5Y cells exposed to MPP+ expressed higher levels of caspase-12, GRP78 and p-JNK. VAP intervention downregulated caspase-12 and p-JNK in a concentration- dependent manner, particularly p-JNK, indicating that the VAPs had an effect on the p-JNK pathway and prevented caspase-12-mediated apoptosis in the SH-SY5Y cells. The marginal downregulation of GRP78 in the VAP treatment groups, compared with the MPP+-only group was concentration-dependent, however, the levels of GRP78 in the VAPs groups remained higher, compared with that in the normal control, suggesting that VAPs had a weak effect on GRP78 signaling. No changes in the expression levels of CHOP were observed in the cells, which may be due to missing the optimal detection time point.

MPP+ is an inducing agent of ER stress, which can induce a rise in cytosolic Ca2+ and the production of ROS, triggering the activation of calpain (45). There is evidence substantiating MPP+-induced calpain activation in dopaminergic MN9D neuronal cells, the process of which was inhibited by Ca2+ chelator (46). Therefore, it is possible that the Ca2+-calpain-caspase-12 pathway is involved in the activation of caspase-12 in SH-SY5Y cells exposed to MPP+, and that VAPs have protective effects. However, previous evidence also suggests that ER Ca2+ leakage-evoked cell apoptosis is independent of caspase-12 activation (47). Therefore, the mechanism underlying the toxic effects of MPP+ in SH-SY5Y cells and the protective role of VAPs require further elucidation.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81503412) and the Jilin Provincial Science and Technology Development Project (grant no. 20140204017YY). The authors would like to thank senior engineer Huaisheng Wang of Jilin Tianyao Science and Technology Co., Ltd. for his support in the velvet antler experiments and pharmacological evaluation. The authors would also like to thank Dr Lengxin Duan and Dr Shoumin Xi of the Medical School, Henan University of Science and Technology (Henan, China).

References

- 1.Zha E, Gao S, Pi Y, Li X, Wang Y, Yue X. Wound healing by a 3.2kDa recombinant polypeptide from velvet antler of Cervus nippon Temminck. Biotechnol Lett. 2012;34:789–793. doi: 10.1007/s10529-011-0829-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tseng SH, Sung CH, Chen LG, Lai YJ, Chang WS, Sung HC, Wang CC. Comparison of chemical compositions and osteoprotective effects of different sections of velvet antler. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;151:352–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huo YS, Huo H, Zhang J. The contribution of deer velvet antler research to the modern biological medicine. Chin J Integr Med. 2014;20:723–728. doi: 10.1007/s11655-014-1827-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zha E, Li X, Li D, Guo X, Gao S, Yue X. Immunomodulatory effects of a 3.2kDa polypeptide from velvet antler of Cervus nippon Temminck. Int Immunopharmacol. 2013;16:210–213. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shan L, Diaz O, Zhang Y, Ladenheim B, Cadet JL, Chiang YH, Olson L, Hoffer BJ, Bäckman CM. L-Dopa induced dyskinesias in Parkinsonian mice: Disease severity or L-Dopa history. Brain Res. 2015;1618:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawong HY, Patterson JR, Winner BM, Goudreau JL, Lookingland KJ. Comparison of the structure, function and autophagic maintenance of mitochondria in nigrostriatal and tuberoinfundibular dopamine neurons. Brain Res. 2015;1622:240–251. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chigurupati S, Wei Z, Belal C, Vandermey M, Kyriazis GA, Arumugam TV, Chan SL. The homocysteine-inducible endoplasmic reticulum stress protein counteracts calcium store depletion and induction of CCAAT enhancer-binding protein homologous protein in a neurotoxin model of Parkinson disease. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18323–18333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.020891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Exner N, Lutz AK, Haass C, Winklhofer KF. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson's disease: Molecular mechanisms and pathophysiological consequences. EMBO J. 2012;31:3038–3062. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blesa J, Trigo-Damas I, Quiroga-Varela A, Jackson-Lewis VR. Oxidative stress and Parkinson's disease. Front Neuroanat. 2015;9:91. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2015.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schapira AH, Tolosa E. Molecular and clinical prodrome of Parkinson disease: Implications for treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:309–317. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egawa N, Yamamoto K, Inoue H, Hikawa R, Nishi K, Mori K, Takahashi R. The endoplasmic reticulum stress sensor, ATF6α, protects against neurotoxin-induced dopaminergic neuronal death. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:7947–7957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.156430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szegezdi E, Logue SE, Gorman AM, Samali A. Mediators of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:880–885. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao SS, Luo KL, Shi L. Endoplasmic reticulum stress interacts with inflammation in human diseases. J Cell Physiol. 2016;231:288–294. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernández A, Ordóñez R, Reiter RJ, González-Gallego J, Mauriz JL. Melatonin and endoplasmic reticulum stress: Relation to autophagy and apoptosis. J Pineal Res. 2015;59:292–307. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seo S, Kwon YS, Yu K, Kim SW, Kwon OY, Kang KH, Kwon K. Naloxone induces endoplasmic reticulum stress in PC12 cells. Mol Med Rep. 2014;9:1395–1399. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duan Z, Zhao J, Fan X, Tang C, Liang L, Nie X, Liu J, Wu Q, Xu G. The PERK-eIF2α signaling pathway is involved in TCDD-induced ER stress in PC12 cells. Neurotoxicology. 2014;44:149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Y, Zhang RY, Zhao J, Dong Z, Feng DY, Wu R, Shi M, Zhao G. Ginsenoside Rd protects SH-SY5Y cells against 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium induced injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:14395–14408. doi: 10.3390/ijms160714395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaudhuri AD, Kabaria S, Choi DC, Mouradian MM, Junn E. MicroRNA-7 promotes glycolysis to protect against 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-induced cell death. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:12425–12434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.625962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monti C, Bondi H, Urbani A, Fasano M, Alberio T. Systems biology analysis of the proteomic alterations induced by MPP(+), a Parkinson's disease-related mitochondrial toxin. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:14. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guan SW, Duan LX, Li YY, Wang BX, Zhou QL. A novel polypeptide from Cervus nippon Temminck proliferation of epidermal cells and NIH3T3 cell line. Acta Biochim Pol. 2006;53:395–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lou Q, Zhang Y, Ren D, Xu H, Zhao Y, Qin Z, Wei W. Molecular characterization and developmental expression patterns of thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) and their responsiveness to TR agonist and antagonist in Rana nigromaculata. J Environ Sci (China) 2014;26:2084–2094. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu P, Li Y, Du SY, Lu Y, Bai J, Guo QL. Comparative pharmacokinetics of borneol in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion and sham-operated rats. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2014;15:84–91. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1300141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brasnjevic I, Steinbusch HW, Schmitz C, Martinez-Martinez P. European NanoBioPharmaceutics Research Initiative: Delivery of peptide and protein drugs over the blood-brain barrier. Prog Neurobiol. 2009;87:212–251. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang G, Xiong N, Zhang Z, Liu L, Huang J, Yang J, Wu J, Lin Z, Wang T. Effectiveness of traditional Chinese medicine as an adjunct therapy for Parkinson's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118498. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herz DM, Haagensen BN, Christensen MS, Madsen KH, Rowe JB, Løkkegaard A, Siebner HR. The acute brain response to levodopa heralds dyskinesias in Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2014;75:829–836. doi: 10.1002/ana.24138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salat D, Tolosa E. Levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson's disease: Current status and new developments. J Parkinsons Dis. 2013;3:255–269. doi: 10.3233/JPD-130186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olanow CW, Stern MB, Sethi K. The scientific and clinical basis for the treatment of Parkinson disease (2009) Neurology. 2009;72(21 Suppl 4):S1–S136. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a1d44c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quik M, Bordia T, Huang L, Perez X. Targeting nicotinic receptors for Parkinson's disease therapy. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2011;10:651–658. doi: 10.2174/187152711797247849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Won L, Ding Y, Singh P, Kang UJ. Striatal cholinergic cell ablation attenuates L-DOPA induced dyskinesia in Parkinsonian mice. J Neurosci. 2014;34:3090–3094. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2888-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ostock CY, Hallmark J, Palumbo N, Bhide N, Conti M, George JA, Bishop C. Modulation of L-DOPA's antiparkinsonian and dyskinetic effects by α2-noradrenergic receptors within the locus coeruleus. Neuropharmacology. 2015;95:215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garcia RL, Sadighi M, Francis SM, Suttie JM, Fleming JS. Expression of neurotrophin-3 in the growing velvet antler of the red deer Cervus elaphus. J Mol Endocrinol. 1997;19:173–182. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0190173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li C, Stanton JA, Robertson TM, Suttie JM, Sheard PW, Harris AJ, Clark DE. Nerve growth factor mRNA expression in the regenerating antler tip of red deer (Cervus elaphus) PLoS One. 2007;2:e148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pita-Thomas W, Fernández-Martos C, Yunta M, Maza RM, Navarro-Ruiz R, Lopez-Rodríguez MJ, Reigada D, Nieto-Sampedro M, Nieto-Diaz M. Gene expression of axon growth promoting factors in the deer antler. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yao B, Zhao Y, Wang Q, Zhang M, Liu M, Liu H, Li J. De novo characterization of the antler tip of Chinese Sika deer transcriptome and analysis of gene expression related to rapid growth. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012;364:93–100. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-1209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng L, Su G, Ren J, Gu L, You L, Zhao M. Isolation and characterization of an oxygen radical absorbance activity peptide from defatted peanut meal hydrolysate and its antioxidant properties. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:5431–5437. doi: 10.1021/jf3017173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alvarez-Fischer D, Noelker C, Vulinović F, Grünewald A, Chevarin C, Klein C, Oertel WH, Hirsch EC, Michel PP, Hartmann A. Bee venom and its component apamin as neuroprotective agents in a Parkinson disease mouse model. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61700. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reglodi D, Kiss P, Lubics A, Tamas A. Review on the protective effects of PACAP in models of neurodegenerative diseases in vitro and in vivo. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:962–972. doi: 10.2174/138161211795589355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oh YM, Jang EH, Ko JH, Kang JH, Park CS, Han SB, Kim JS, Kim KH, Pie JE, Shin DW. Inhibition of 6-hydroxyldopamine-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress by l-carnosine in SH-SY5Y cells. Neurosci Lett. 2009;459:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang P, Gan M, Lin WL, Yen SH. Nutrient deprivation induces α-synuclein aggregation through endoplasmic reticulum stress response and SREBP2 pathway. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:268. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Francisco AB, Singh R, Li S, Vani AK, Yang L, Munroe RJ, Diaferia G, Cardano M, Biunno I, Qi L, et al. Deficiency of suppressor enhancer Lin12 1 like (SEL1L) in mice leads to systemicc endoplasmic reticulum stress and embryonic lethality. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13694–13703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.085340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baek JH, Whitfield D, Howlett D, Francis P, Bereczki E, Ballard C, Hortobágyi T, Attems J, Aarsland D. Unfolded protein response is activated in Lewy body dementias. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2016;42:352–365. doi: 10.1111/nan.12260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chung CY, Khurana V, Auluck PK, Tardiff DF, Mazzulli JR, Soldner F, Baru V, Lou Y, Freyzon Y, Cho S, et al. Identification and rescue of α-synuclein toxicity in Parkinson patient-derived neurons. Science. 2013;342:983–987. doi: 10.1126/science.1245296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeng XS, Jia JJ, Kwon Y, Wang SD, Bai J. The role of thioredoxin-1 in suppression of endoplasmic reticulum stress in Parkinson disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;67:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu X, Li Y, Wang W, Chen S, Liu T, Jia D, Quan X, Sun D, Chang AK, Gao B. 3β-hydroxysteroid-Δ 24 reductase (DHCR24) protects neuronal cells from apoptotic cell death induced by endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86753. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ray SK, Wilford GG, Ali SF, Banik NL. Calpain upregulation in spinal cords of mice with 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced Parkinson's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;914:275–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim C, Yun N, Lee YM, Jeong JY, Baek JY, Song HY, Ju C, Youdim MB, Jin BK, Kim WK, Oh YJ. Gel-based protease proteomics for identifying the novel calpain substrates in dopaminergic neuronal cell. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:36717–36732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.492876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakano T, Watanabe H, Ozeki M, Asai M, Katoh H, Satoh H, Hayashi H. Endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ depletion induces endothelial cell apoptosis independently of caspase-12. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69:908–915. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]