Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the most common cause of lower respiratory tract infections in infants younger than 1 year. Premature infants, infants with chronic lung disease, infants with major congenital heart diseases, or infants with severe immunodeficiencies are at highest risk of hospital admission for RSV. Palivizumab, a monoclonal antibody, reduces pulmonary viral replication by 100-fold at serum drug levels greater than 40 μg/mL in the cotton rat model.1 On the basis of randomized clinical trials, monthly administration of 15mg/kg of palivizumab reduces hospitalizations by approximately 55% in these infants.2 However, the costliness of this drug restrains its broader use. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a maximum of 5 palivizumab doses in selected risk groups during the RSV season,2 although pharmacokinetic analyses suggest that equivalent antibody protection may be sustainably achieved with fewer doses.3,4

Methods

In British Columbia, administration of palivizumab necessitates central approval through the British Columbia RSV Immunoprophylaxis Program, and eligible infants are closely followed up by program-coordinated clinics across the province. The RSV season extends from November to April, with the first and last palivizumab doses given the closest day to November 15 and on April 15, respectively. All infants receive a maximum of 3 or 4 doses based on criteria listed in the Table, with maximal dose intervals of 28 days after the first dose and 35 days after the second and subsequent approved doses (prospectively defined as the scheduled dosing period). Hospitalizations in the preceding month are assessed in program clinics before each dose and up to April 30 each year. Program data were linked to the Discharge Abstract Database of the British Columbia Health Authorities to confirm hospitalizations, according to 7 diagnostic codes for RSV bronchiolitis or acute respiratory infection of unspecified cause using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification. The study was approved by the Children’s & Women’s Research Ethics Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in whom blood samples were obtained for RSV neutralizing antibody measures.

Table.

Administration Criteria for Respiratory Syncytial Virus Immunoprophylaxis in British Columbia

| Indication | Maximum No. of Doses |

|---|---|

| BPD or CLD requiring oxygen or continuous positive airway pressure at >28 days of age and <1 year of age by November 1 AND receiving supplemental oxygen on or after July 1 | 4 |

| Born at <29 weeks of gestation and discharged home on or after September 1 | 4 |

| Tracheostomy, receiving home oxygen, or receiving home ventilatory support on or after November 1 and <2 years of age by November 1 | 4 |

| Multiples (twins or triplets) of approved child and born on or after November 1, 2012 | Same as approved sibling |

| Hemodynamically significant CHD and <2 years of age by November 1 | 4 |

| Severe immunodeficiency (eg, stem cell transplantation) and <2 years of age by November 1 | 4 |

| Cystic fibrosis with lung disease and born on or after January 1 | |

| Trisomy 21 without hemodynamically significant CHD and discharged home on or after October 1 and with a risk factor score ≥42 pointsa | 4 |

| Significant pulmonary disability (pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary malformations, severe BPD, progressive neuromuscular disease, other) and <2 years of age by November 1 | 4 |

| Infants born between 29 and <35 completed weeks of gestation without BPD or CLD and discharged home on or after October 1 and with a risk factor score ≥42 pointsa | 3 |

Abbreviations: BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; CHD, congenital heart disease; CLD, chronic lung disease.

Risk factor score is calculated as follows: Infant attends day care regularly during first 3 months after discharge (22 points); discharged home in December, January, or February (20 points); discharged home in November or March (10 points); gestational age at birth of 29weeks to less than 31weeks of completed gestation (10 points); more than 5 people living in household (12 points); sibling younger than 5 years (14 points); remote community, travel of more than 1 hour or of more than 100 km required to the nearest hospital (10 points); girl not receiving breastmilk, or boy (8 points); birthweight less than 10th percentile (8 points); and 2 or more smokers in household (8 points).

Results

We report our population-based intent-to-treat analysis with 100% follow-up rate. Since we adopted this abbreviated program, 514 infants and 666 infants have been approved in the 3- and 4-dose schedules for 4 (2010–2014) and 2 seasons (2012–2014), respectively. In the 3-dose cohort, 1 of 514 infants (0.2%) was hospitalized with RSV during the scheduled dosing period, and 1 was hospitalized 58 days after the third dose. In the 4-dose cohort, 10 infants (1.5%) were hospitalized with RSV during the scheduled dosing period, and 2 twins (0.3%) were hospitalized 65 days after the fourth dose. Moreover, 7 infants (1.4%) and 18 infants (2.7%) in the 3-dose and 4-dose cohorts, respectively, were hospitalized for acute bronchiolitis with no viral studies performed (unspecified cause)within the scheduled dosing period. No infants in either cohort were hospitalized for unspecified bronchiolitis beyond the same period. These outcomes are comparable to historical cohorts treated under the 5-dose regimen.5

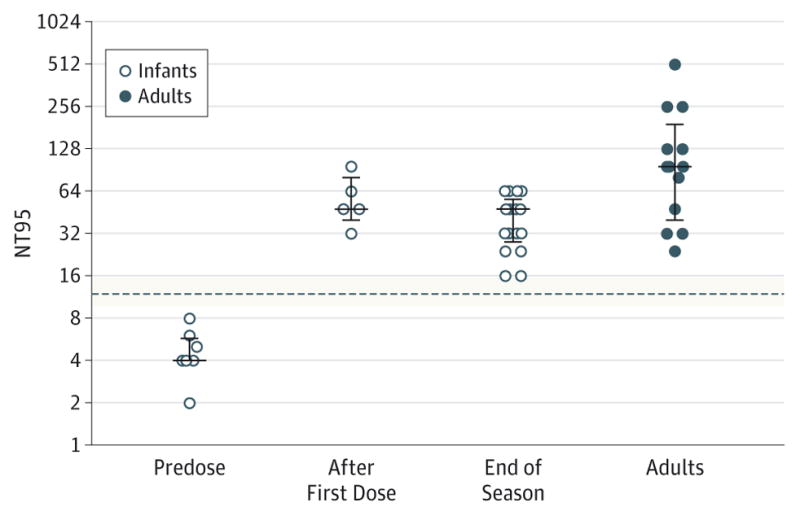

Our results agree with end-of-season RSV neutralizing serum antibodies measured in a subgroup of program infants approved to receive 3 or 4 doses of palivizumab. Before the first palivizumab dose, antibody titers in all infants were below protective levels, consistent with low preexisting immunity (Figure). In contrast, a first palivizumab dose resulted in RSV neutralizing antibody titers above protective equivalents in infants in our abbreviated dose program. In these infants, protective neutralizing antibody levels persisted beyond the end of the RSV season (Figure).

Figure. Serum Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Neutralizing Antibody Titers in Infants in the Abbreviated Palivizumab Dosing Program.

A subset of infants approved to receive either 3 or 4 doses of palivizumab were tested before any palivizumab dose, between 1 and 5 days after a first dose of palivizumab, and at the end of the RSV season (at least 30 days after the last palivizumab dose or after April 15, whichever came last). The RSV neutralizing antibody titers were also determined in season-matched healthy adults. The RSV neutralizing serum antibody titer equivalents (NT95) are based on the ability of a serum dilution (expressed as 1/titer) to inhibit 95%or more of viral infection. In this assay, we determined that palivizumab serum concentrations of 40 μg/mL correspond to a median neutralizing antibody titer of 1:12 (dotted line with minimum and maximum values [shaded area from 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate]). Detection limit was NT95 of approximately 4 (or 1/4), equivalent to a serum concentration of palivizumab of approximately 6.25 μg/mL except for predose serum samples for which the detection limit of the assay was NT95 of approximately 2. Error bars represent median with interquartile range.

Discussion

The RSV neutralizing antibodies comprise palivizumab and natural immunity against the virus, which is important because preexisting antibodies correlate best with protection against infection in humans.6 In summary, our experience in British Columbia provides real-world evidence of adequate protection using an abbreviated palivizumab dosing schedule in infants at higher risk for RSV hospitalization. These data have considerable resource implications for RSV prevention in other medical jurisdictions.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was funded in part by grants MOP-123478 (Dr Lavoie) and MOP-133691 (Dr Turvey) from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, by the British Columbia RSV Immunoprophylaxis Program (Dr Solimano), and British Columbia Lung Association (Dr Marr).

Footnotes

Additional Contributions: George S. McRae, MN, of the Provincial Health Services Authority provided access to provincial data; Laurence Bayzand, MA, Alison Butler, BSc, Cheryl Christopherson, BSc, RN, Patricia Eastman, RN, Nadine Lusney, RN, and Joy Markowski, RN, from the British Columbia RSV Immunoprophylaxis Program provided data and program management; Allison Callejas, MD, and Amitava Sur, MD, provided recruitment of participants for serum antibody testing; Mark Peeples, PhD, of the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, and Peter Collins, PhD, of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, Maryland, provided recombinant RSV strain rgRSV30 used in the antibody assay.

Author Contributions: Dr Solimano had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Lavoie, Solimano, Taylor, Kwan, Marr.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Lavoie, Solimano, Claydon, Turvey, Marr.

Drafting of the manuscript: Lavoie, Solimano.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Lavoie, Marr.

Obtained funding: Lavoie, Solimano, Turvey, Marr.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Solimano, Taylor, Claydon, Turvey, Marr.

Study supervision: Lavoie, Solimano.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Lavoie reported receiving salary support from Child & Family Research Institute Clinician-Scientist and Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR) Career Investigator Awards. Dr Turvey reported holding the Aubrey J. Tingle Professorship in Pediatric Immunology and receiving a Clinical Research Scholar Award from the MSFHR. No other disclosures were reported.

References

- 1.Johnson S, Oliver C, Prince GA, et al. Development of a humanized monoclonal antibody (MEDI-493) with potent in vitro and in vivo activity against respiratory syncytial virus. J Infect Dis. 1997;176(5):1215–1224. doi: 10.1086/514115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brady MT American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases; American Academy of Pediatrics Bronchiolitis Guidelines Committee. Updated guidance for palivizumab prophylaxis among infants and young children at increased risk of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):415–420. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gutfraind A, Galvani AP, Meyers LA. Efficacy and optimization of palivizumab injection regimens against respiratory syncytial virus infection. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(4):341–348. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinberger DM, Warren JL, Steiner CA, Charu V, Viboud C, Pitzer VE. Reduced-dose schedule of prophylaxis based on local data provides near-optimal protection against respiratory syncytial virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(4):506–514. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell I, Paes BA, Li A, Lanctôt KL CARESS investigators. CARESS: the Canadian Registry of Palivizumab. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(8):651–655. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31821146f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luchsinger V, Piedra PA, Ruiz M, et al. Role of neutralizing antibodies in adults with community-acquired pneumonia by respiratory syncytial virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(7):905–912. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]