Abstract

Background and Purpose

The development of subtype‐selective ligands to inhibit voltage‐sensitive sodium channels (VSSCs) has been attempted with the aim of developing therapeutic compounds. Tetrodotoxin (TTX) is a toxin from pufferfish that strongly inhibits VSSCs. Many TTX analogues have been identified from marine and terrestrial sources, although their specificity for particular VSSC subtypes has not been investigated. Herein, we describe the binding of 11 TTX analogues to human VSSC subtypes Nav1.1–Nav1.7.

Experimental Approach

Each VSSC subtype was transiently expressed in HEK293T cells. The inhibitory effects of TTX analogues on each subtype were assessed using whole‐cell patch‐clamp recordings.

Key Results

The inhibitory effects of TTX on Nav1.1–Nav1.7 were observed in accordance with those reported in the literature; however, the 5‐deoxy‐10,7‐lactone‐type analogues and 4,9‐anhydro‐type analogues did not cause inhibition. Chiriquitoxin showed less binding to Nav1.7 compared to the other TTX‐sensitive subtypes. Two amino acid residues in the TTX binding site of Nav1.7, Thr1425 and Ile1426 were mutated to Met and Asp, respectively, because these residues were found at the same positions in other subtypes. The two mutants, Nav1.7 T1425M and Nav1.7 I1426D, had a 16‐fold and 5‐fold increase in binding affinity for chiriquitoxin, respectively.

Conclusions and Implications

The reduced binding of chiriquitoxin to Nav1.7 was attributed to its C11–OH and/or C12–NH2, based on reported models for the TTX‐VSSC complex. Chiriquitoxin is a useful tool for probing the configuration of the TTX binding site until a crystal structure for the mammalian VSSC is solved.

Abbreviations

- CHTX

chiriquitoxin

- ORF

open reading frames

- STX

saxitoxin

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- VSSC

voltage‐sensitive sodium channel

Introduction

Voltage‐sensitive sodium channels (VSSCs) are composed of a pore‐forming α‐subunit and auxiliary β‐subunits (Catterall et al., 2005). The primary group of the α‐subunit is classified into Nav1.1 to Nav1.9 subgroups (Catterall et al., 2005), which play various physiological roles in different organs and are potentially responsible for genetic diseases, chronic pain, epilepsy and cardiac dysrhythmia (Tan et al., 2001; Antzelevitch et al., 2005; Meisler and Kearney, 2005; Amir et al., 2006). Various models for VSSCs have been constructed; however, a mammalian VSSC has yet to be crystalized. Therefore, patch‐clamp studies, binding assays and photoaffinity‐labelling experiments, which utilize naturally occurring toxins and synthetic compounds that modulate VSSCs, have been important for the understanding of the structures and functions of mammalian VSSCs and to develop improved therapies.

Naturally occurring toxins that bind to VSSCs are classified into six groups based on their binding sites (Sites 1 to 6) (Catterall et al., 2007). However, most of these natural toxins do not recognize a specific subtype of VSSCs and are not applicable for clinical use. Local anaesthetics, anticonvulsants and antiarrhythmic drugs are not natural toxins but are known to block VSSCs; although they are used clinically, they have unavoidable side effects (Bagal et al., 2014). Thus, despite the high sequence identity between different VSSC subtypes, subtype‐specific inhibitors have been targeted for drug development. Site 1 is located at the entrance of the pore overlapping the ion selectivity filter. Here, tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1, Figure 1), saxitoxin (STX) and μ‐conotoxin block the sodium current by occluding the ion permeation pathway (Narahashi et al., 1964; 1967; Ohizumi et al., 1986). The molecular determinants of the high affinity binding of TTX (1) to VSSCs have been investigated using various TTX analogues in binding assays with rat brain synaptosomes (Yotsu‐Yamashita et al., 1999), or cell‐based assays using the neuroblastoma cell line Neuro 2A (Yotsu‐Yamashita et al., 2003; Kudo et al., 2014; Saruhashi et al., 2016). However, rat brain synaptosomes and mouse neuroblastoma Neuro 2A cells express multiple subtypes of VSSCs (Lou et al., 2005). The molecular determinants of VSSCs that generate high affinity binding to TTX (1) were also demonstrated by VSSC mutants, mostly those of Nav1.2 and Nav1.4 (Terlau et al., 1991; Choudhary et al., 2003). TTX (1) and its various analogues have been identified in many marine and terrestrial species (Yotsu‐Yamashita, 2001). With subtle modifications of the TTX (1) structure, we believe that a TTX analogue would exhibit subtype selectivity.

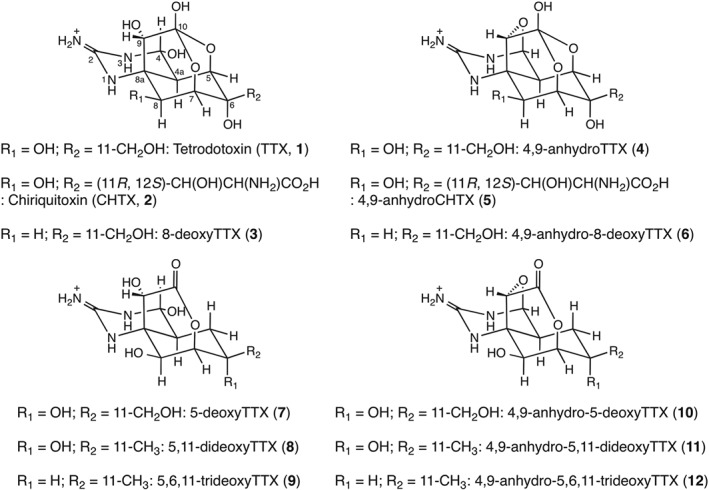

Figure 1.

The structures of TTX and its analogues: TTX (1), CHTX (2), 8‐deoxyTTX (3), 4,9‐anhydroTTX (4), 4,9‐anhydroCHTX (5), 4,9‐anhydro‐8‐deoxyTTX (6), 5‐deoxyTTX (7), 5,11‐dideoxyTTX (8), 5,6,11‐trideoxyTTX (9), 4,9‐anhydro‐5‐deoxyTTX (10), 4,9‐anhydro‐5,11‐dideoxyTTX (11) and 4,9‐anhydro‐5,6,11‐trideoxyTTX (12) are shown.

Therefore, we expressed human VSSCs (Nav1.1–Nav1.7) in HEK293T cells and evaluated the ability of TTX analogues (1–12, Figure 1) to block each subtype using whole‐cell patch‐clamp recordings. Chiriquitoxin (CHTX, 2) exclusively exhibited less binding to Nav1.7 than to the other TTX‐sensitive subtypes. Molecular determinants for the specific reduction of CHTX (2) blockade against Nav1.7 were deduced to be Met1425 and Asp1426 in domain III of the VSSC. We discuss the spatial location of the CHTX (2) based on VSSC models reported in the literature.

Methods

Preparation of the plasmid DNA for VSSC subtype expression

The cDNA for each sodium channel subtype was obtained from Origene Technologies (Rockville, MD, USA). Plasmids expressing each VSSC subtype in HEK293T cells, including pCDM8 Nav1.2, pCDM8 Nav1.4, pCDM8 Nav1.5, pCDM8 Nav1.6 and pCDM8 Nav1.7, were constructed as follows. First, the open reading frames (ORF) of Nav1.2, Nav1.4, Nav1.5, Nav1.6 and Nav1.7 were amplified by PCR using the forward and reverse primers AGG GAG ACC CAA GCT GAA TTC GTC GAC TGG ATC CGG and TGG AAG ATC CCT CGA GCC GGC CGT TTA AAC CTT ATC, respectively, with KOD‐plus as the polymerase. The reaction mixture was subjected to PCR conditions of 94°C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 60°C for 30 s and 68°C for 3 min. Using the same PCR conditions, linearized pCDM8 was amplified using pCDM8 as the template and forward and reverse primers of CTC GAG GGA TCT TCC and AAG CTT GGG TCT CCC respectively. The amplified ORF and linearized vector were subjected to the In‐Fusion HD Cloning kit to obtain the desired vector. Next, pCDM8 Nav1.1 and pCDM8 Nav1.3 were constructed in a conventional manner. PCR was conducted with the cDNA purchased from Origene Technologies, Inc. as the template. The forward primer ATCT CTC GAG GAA TTC GTC GAC TGG and reverse primers AAC TAT GCG GCC GCG TTA TTT CCC TTT GGC (for Nav1.1) and GGC TAT GCG GCC GCG TTA CTT TTG ATT TTC (for Nav1.3) were designed. The PCR product and pCDM8 were both cut with XhoI and NotI and ligated to each other with T4 DNA ligase.

The plasmid pCDM8 Nav1.7 T1425M was constructed as follows. The forward and reverse primers for generating T1425M were CCG TAG CTA AGG GAT GGA TGA T and GTC GCC CAT AAT AAT CAT CCA TCC respectively. For the first step in generating T1425M, PCR was performed using two pairs of primers, ATC TCT CGA GGA ATT CGT CGA CTG G and GTC GCC CAT AAT AAT CAT CCA TCC, as well as CCG TAG CTA AGG GAT GGA TGA T and GGC TAT GCG GCC GCG TTA TTT TTT GCT TTC, with pCDM8 Nav1.7 as the template. The PCR conditions were 94°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 60°C for 30 s and 68°C for 3 min. The two amplified fragments were used as the templates, and a second cycle of PCR was performed using the same conditions with another pair of primers, ATCT CTC GAG GAA TTC GTC GAC TGG and GGC TAT GCG GCC GCG TTA TTT TTT GCT TTC. The PCR product and pCDM8 were both cut with XhoI and NotI and ligated to each other with T4 DNA ligase. After ligation, in all cases, competent TOP10/P3 cells were used to recruit a single plasmid DNA, and the pCDM8 plasmid was extracted with the Viogene Midi Plus Purification System (Viogene BioTek Corp., Sijhih Dist., New Taipei City, Taiwan). The plasmid was analysed at Fasmac Co., Ltd. to obtain confirmation of the sequences.

The plasmid pCDM8 Nav1.7 I1426D was constructed as follows. The forward and reverse primers for generating I1426D were CCT ATA CGG ATG GAC GGA CAT T and CCT ATA CGG ATG GAC GGA CAT T respectively. For the first step in generating I1426D, PCR was performed using two pairs of primers, ATCT CTC GAG GAA TTC GTC GAC TGG and CCT ATA CGG ATG GAC GGA CAT T as well as CCT ATA CGG ATG GAC GGA CAT T and GGC TAT GCG GCC GCG TTA TTT TTT GCT TTC, using pCDM8 Nav1.7 as the template. The subsequent procedures, including the PCR conditions, digestion with restriction enzymes, ligation, cloning and sequencing, were identical to those used for the construction of pCDM8 Nav1.7 T1425M.

Expression of each VSSC subtype in HEK293T cells

HEK293T cells were maintained in minimum essential medium (MEM) containing 10 U·mL−1 penicillin, 10 μg·mL−1 streptomycin (Thermo Fischer Scientific K. K., Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan) and 10% v.v−1 FBS. HEK293T cells at 40–50% confluency were co‐transfected using a calcium phosphate method (Chen and Okayama, 1987), with the pCDM8 plasmid carrying the cDNA of the VSSC and EBO pCD Leu2 (ATC 59565) carrying the cDNA of the CD8 antigen. After 8–12 h, the cells were treated with 0.05% EDTA (Thermo Fischer Scientific K. K., Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan) to obtain single cells in a 35 mm dish for whole‐cell patch‐clamp recordings. VSSC expression in the transfected cells was detected with anti‐CD8 conjugated magnetic beads (Dynabeads CD8, Thermo Fischer Scientific K. K., Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan).

We originally planned to heterologously express Nav1.8 and Nav1.9 in the ND7/23 cell line, which was generated from mouse neuroblastoma and rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. However, an endogenous sodium current in ND7/23 cells was observed upon depolarization, which was inappropriate for the present study.

Patch‐clamp recordings

Patch‐clamp recordings were conducted using a whole‐cell recording configuration. The extracellular buffer comprised 140 mM NaCl, 1.0 mM MgCl2·6H2O, 5.0 mM CsCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2 and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4, adjusted with NaOH). The intracellular buffer contained 189 mM N‐methyl‐D‐glucamine, 1.0 mM NaCl, 4.0 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM 1,2‐bis(2‐aminophenoxy)ethane‐N,N,N′,N′‐tetraacetic acid, 25 mM tris‐phosphocreatine, 2.0 mM ATP disodium salt, 0.2 mM GTP monosodium salt, and 40 mM HEPES (pH 7.4, adjusted with CsOH) (Bricelj et al., 2005). Recordings were performed at room temperature using an EPC10 USB amplifier (HEKA Elektronik Dr. Schulze GmbH, Lambrecht, Pfalz, Germany) that was controlled using Patchmaster software. When a glass capillary was attached to the bath solution, the capillary resistance was 2–5 MΩ. The series resistance was compensated at more than 50%. Experimental investigations into the activities of TTX and its analogues were conducted as long as the ‘gigaseal’ was retained.

Data analysis

The whole‐cell patch‐clamp experiments were analysed using IgorPro software. Steady‐state activation was analysed according to the following protocol. The holding potential was set at −100 mV, and a series of rectangular pulses consisting of −100 mV for 10 ms, test potential in the range −80 to +40 mV in 10 mV increments for 20 ms and −100 mV for 10 ms were applied to the cell every 5 s to obtain an I–V relationship. Linear fitting of this I–V curve between 0 and 40 mV was performed to calculate the V‐intercept, which is the reversal potential of Vrev. Conductance was calculated at each membrane potential using the Boltzmann equation: G = I peak/(V − V rev), where G, I peak, V and V rev represent the conductance, peak sodium current, membrane potential and reversal potential respectively. G was divided by the maximum conductance to obtain the normalized conductance, G n (V), which was plotted against the membrane potential (V) and fitted to the Boltzmann equation in the following form: Gn (V) = 1/[1 + exp ((V − V a)/S)], where G n (V), V, V a and S represent the normalized conductance, the membrane potential, half‐activation potential and the slope factor respectively. Steady‐state inactivation was also analysed using a double‐pulse protocol as follows. The holding potential was set at −100 mV, and a series of rectangular pulses consisting of −100 mV for 10 ms, the test potential ranging from −120 to 0 mV in 10 ms increments for 100 ms, −100 mV for 1 ms, −10 mV for 50 ms and −100 mV for 10 ms were applied to the cell every 5 s. The peak sodium current induced by the test pulse at −10 mV in the fourth step was normalized to the maximum sodium current observed. The normalized current, I h (V), was plotted against the 100 ms conditioning pulse in the second step. I h (V) was fitted as a function of I h (V) = 1/[1 + exp ((V − V i)/S)], where I h (V), V, V i and S represent the normalized current, membrane potential, half‐inactivation potential and slope factor respectively.

The dose‐dependent inhibition of the expressed VSSC by the test compound was investigated as follows. Test pulses to −10 mV for 20 ms were applied to the cell every 5 s. Extracellular buffer containing the test compound was applied to the cell by a Y‐tube system (Yamaoka et al., 2004), and the effect was evaluated by means of a decrease in the peak current. Experimental data with a run‐down effect of less than 15% were chosen, and the inhibitory effect of the test compound was compensated against the run‐down effect. The inhibition ratio (%) was plotted against the concentration of the test compound, and the dose–response curve was fitted to the Hill equation in the form R (L) = R min + (R max − R min)/[1 + (IC50/L)rate], where R (L), R min, R max, L and rate represent the inhibition ratio at a concentration of the test compound, maximum inhibition ratio, minimum inhibition ratio, concentration of the test compound and Hill coefficient respectively.

The use‐dependent block of the expressed VSSC by the test compound was investigated using the following procedure. The cell was subjected to a series of 2 ms depolarization pulses from a holding potential of −100 mV to the test potential of −10 mV, with frequencies of 1 Hz for 5 s, 2 Hz for 5 s, 5 Hz for 5 s and 10 Hz for 5 s. The test compound with extracellular buffer was applied to the cell by a Y‐tube system (Yamaoka et al., 2004), and the effect was evaluated by means of a decrease in the peak current.

Compliance with design and statistical analysis requirements

The data and statistical analysis comply with the recommendations on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology (Curtis et al., 2015).

Group sizes

A priori power analysis and post hoc tests were performed with G'power (Faul et al., 2007) to determine and confirm the size of treatments. For a priori power analysis, α error probability, power and effect size were 0.05, 0.8 and 0.5 respectively. The limited quantities of synthetic samples did not permit all group sizes to be greater than five. However, the data subjected to statistical analysis were derived from more than five experiments in each group.

Randomization and blinding

Randomization and blinding were not performed as they are not standard procedures in whole‐cell patch‐clamp recording. Instead, to improve the transparency of the study, one person designed and wrote the pulse protocols for the whole‐cell patch‐clamp recordings, four different persons conducted the whole‐cell patch‐clamp recordings and two persons independently analysed the experimental data. Extracellular buffers containing the test compound at various concentrations were prepared on the day of experiment.

Statistical comparison

Group mean values and statistical analyses used independent values. When comparing any two groups, the threshold for statistical significance was defined as P = 0.05 and was kept constant in the present study. After ANOVA, a post hoc test was performed only if F was statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Translation

This study is a basic research study and is not subject to clinical relevance.

Materials

TTX (1) (Ohyabu et al., 2003; Nishikawa et al., 2004; Urabe et al., 2006), CHTX (2) (Adachi et al., 2014a), 8‐deoxyTTX (3) (Satake et al., 2014), 4,9‐anhydroTTX (4) (Ohyabu et al., 2003; Nishikawa et al., 2004; Urabe et al., 2006), 4,9‐anhydroCHTX (5), 4,9‐anhydro‐8‐deoxyTTX (6), 5‐deoxyTTX (7) (Satake et al., 2014), 5,11‐dideoxyTTX (8) (Nishikawa et al., 1999; Asai et al., 2001; Yotsu‐Yamashita et al., 2013), 5,6,11‐trideoxyTTX (9) (Adachi et al., 2014b), 4,9‐anhydro‐5‐deoxyTTX (10) (Satake et al., 2014), 4,9‐anhydro‐5,11‐dideoxyTTX (11) (Nishikawa et al., 1999; Asai et al., 2001; Yotsu‐Yamashita et al., 2013) and 4,9‐anhydro‐5,6,11‐trideoxyTTX (12) (Adachi et al., 2014b) were synthesized as reported in the literature (Figure 1).

cDNAs for each subtype of human voltage‐dependent sodium channel were purchased from Origene Technologies, Inc. (Rockville, MD, USA). A vector for the expression of VSSCs in a HEK cell line, pCDM8, was kindly provided by associate professor Frank H. Yu of the School of Dentistry, Seoul National University. HEK293T cells were obtained from the Riken Bioresource Centre through the National Bio‐Resource Project of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan.

KOD‐Plus, T4 ligase and the In‐Fusion HD Cloning kit were purchased from Takara Bio, Inc. (Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan). PCR primers were purchased from Fasmac Co., Ltd. (Atsugi, Kanagawa, Japan). Competent TOP10/P3 cells and the restriction enzymes HindIII, XhoI and NotI were purchased from Thermo Fischer Scientific (Thermo Fischer Scientific K. K., Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan). Bacto agar, bacto tryptone and bacto yeast extract were purchased from Becton, Dickinson and Company (Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA). All other chemicals were purchased from Nacalai Tesque, Inc. (Nakagyo, Kyoto, Japan); Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Chuou, Osaka, Japan); or Sigma‐Aldrich Japan, Inc. (Shinagawa, Tokyo, Japan).

Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Southan et al., 2016), and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16 (Alexander et al., 2015).

Results

Inhibition of the VSSC subtypes by TTX and its analogues

Whole‐cell patch‐clamp recordings were conducted to confirm the expression of each VSSC, and the steady‐state activation (Supporting Information Figure S1) and inactivation (Supporting Information Figure S2) of the channels were subsequently analysed (Supporting Information Figure S3). The half‐activation potentials (Supporting Information Figure S3A) and half‐inactivation potentials (Supporting Information Figure S3B) were identical, within error, to the reported values (Supporting Information Figure S3C) (Catterall et al., 2005).

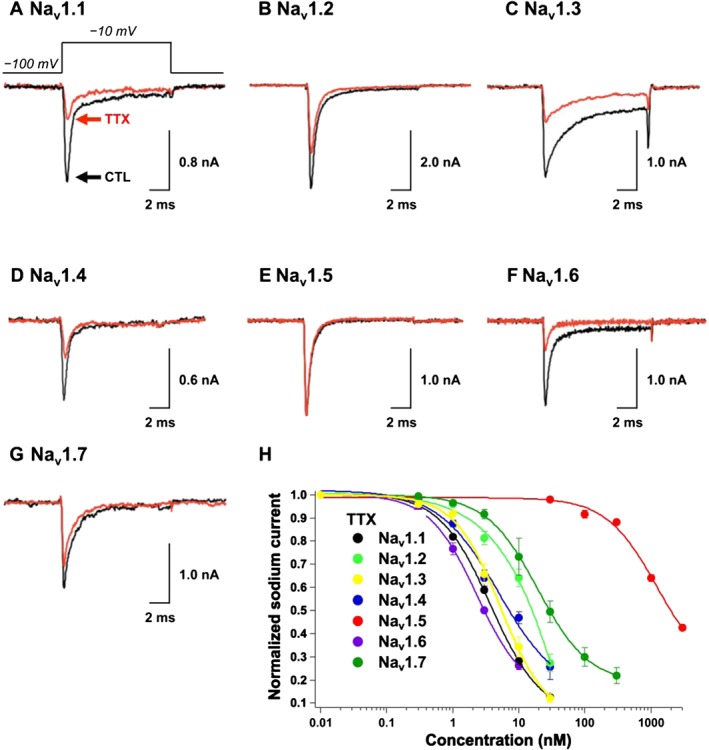

First, the inhibitory activity of TTX (1) was evaluated (Figure 2). The peak sodium currents of Nav1.1 (Figure 2A), Nav1.2 (Figure 2B), Nav1.3 (Figure 2C), Nav1.4 (Figure 2D), Nav1.6 (Figure 2F) and Nav1.7 (Figure 2G) were inhibited by 72 ± 2% (n = 4), 36 ± 4% (n = 3), 67 ± 4% (n = 8), 53 ± 3% (n = 3), 74 ± 2% (n = 3) and 25 ± 7% (n = 6), respectively, in the presence of 10 nM TTX (1). By contrast, Nav1.5 (Figure 2E) was insensitive to TTX (1), with a 6.9 ± 2.0% block at 30 nM because of the lack of an aromatic amino acid residue at the TTX binding site in Nav1.5 (Satin et al., 1992). The blocking activity was reversible. When the cell was perfused with TTX‐free extracellular buffer, the Nav1.1−Nav1.7 sodium currents were restored to levels observed for the control. Other TTX analogues (2–12) tested in the present study exhibited reversible binding similar to that of TTX (1). The dose response of TTX (1) against Nav1.1−Nav1.7 was investigated, and the IC50 value was determined by fitting the dose–response curve to the Hill equation (Figure 2H). The IC50 values shown in Table 1, in addition to the parameters for steady‐state activation and inactivation (Supporting Information Figure S3C), indicated the successful establishment of the assay system.

Figure 2.

Inhibitory effects of TTX (1) on Nav1.1–Nav1.7 expressed in HEK293T cells. The sodium currents in (A) Nav1.1, (B) Nav1.2, (C) Nav1.3, (D) Nav1.4, (E) Nav1.5, (F) Nav1.6 and (G) Nav1.7 were recorded in the absence (black line) and presence (red line) of TTX (1). The TTX concentration was 10 nM in (A−D, F, G) and 30 nM in (E). (H) The dose‐dependent inhibitory effects of TTX (1) on Nav1.1, Nav1.2, Nav1.3, Nav1.4, Nav1.5, Nav1.6 and Nav1.7 are shown.

Table 1.

The IC50 concentration or the maximum concentrations of compounds (1–12) against Nav1.1–Nav1.7

| Compound | Nav1.1 | Nav1.2 | Nav1.3 | Nav1.4 | Nav1.5 | Nav1.6 | Nav1.7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTX (1) | 4.1 ± 0.2 nM (n = 4) | 14 ± 2 nM (n = 3) | 5.3 ± 0.6 nM (n = 5) | 7.6 ± 2.6 nM (n = 3) | 1.0 ± 0.1 μM (n = 3) | 2.3 ± 0.0 nM (n = 3) | 36 ± 7 nM (n = 5) |

| CHTX (2) | 26 ± 1 nM (n = 5) | 27 ± 7 nM (n = 3) | 14 ± 2 nM (n = 7) | 50 ± 3 nM (n = 3) | 1.9 ± 0.9 μM (n = 4) | 43 ± 10 nM (n = 4) | 471 ± 27 nM (n = 7) |

| 8‐deoxyTTX (3) | 4.8 ± 0.46 μM (n = 3) | >300 nM | 4.9 ± 0.4 μM (n = 3) | 5.1 ± 1.4 μM (n = 3) | >300 nM | 4.6 ± 0.2 μM (n = 3) | >300 nM |

| 4,9‐anhydro‐TTX (4) | ND | ND | ND | >100 nM | >100 nM | 294 ± 25 nM (n = 3) | ND |

| 4,9‐anhydro‐CHTX (5) | ND | ND | ND | >100 nM | >100 nM | ND | ND |

| 4,9‐anhydro‐8‐deoxyTTX (6) | ND | ND | ND | >100 nM | >100 nM | ND | ND |

| 5‐deoxyTTX (7) | 57 ± 6 μM (n = 3) | >300 nM | 12 ± 1 μM (n = 3) | 4.5 ± 1.0 μM (n = 3) | >300 nM | >300 nM | >300 nM |

| 5,11‐dideoxyTTX (8) | >300 nM | >300 nM | >300 nM | >300 nM | >300 nM | >300 nM | >300 nM |

| 5,6,11‐trideoxyTTX (9) | >300 nM | >300 nM | >300 nM | >300 nM | >300 nM | >300 nM | >300 nM |

| 4,9‐anhydro‐5‐deoxyTTX (10) | ND | ND | ND | >100 nM | >100 nM | ND | ND |

| 4,9‐anhydro‐5,11‐dideoxyTTX (11) | ND | ND | ND | >100 nM | >100 nM | ND | ND |

| 4,9‐anhydro‐5,6,11‐trideoxyTTX (12) | ND | ND | ND | >100 nM | >100 nM | ND | ND |

The IC50 concentrations for TTX (1), CHTX (2), 8‐deoxyTTX (3) and 5‐deoxyTTX (7) are presented as the means ± SEM. The number of experiments is indicated in parentheses below the IC50 values. VSSC subtypes that were not tested for inhibitory activity of the test compound are marked as ND.

Next, the TTX analogues (3–12) were evaluated for their inhibitory effects on the Nav subtypes. When these analogues were tested at a maximum concentration of 300 nM, the channels were largely insensitive to 8‐deoxyTTX (3), 5‐deoxyTTX (7), 5,11‐dideoxyTTX (8) and 5,6,11‐trideoxyTTX (9) with less than 10% inhibition (Supporting Information Table S1). 8‐DeoxyTTX (3) was tested at a higher concentration against Nav1.1, Nav1.3, Nav1.4 and Nav1.6, while 5‐deoxyTTX (7) was tested at a higher concentration against Nav1.1, Nav1.3 and Nav1.4 (Table 1). The IC50 value of either of the two compounds for each subtype of VSSC was approximately three orders of magnitude larger than that of TTX (1). Rosker et al. (2007) showed that 4,9‐anhydroTTX (4) selectively inhibits Nav1.6 with an IC50 value of 7.8 ± 2.3 nM but does not affect other subtypes. Teramoto et al. revealed the inhibition of a resurgent‐like current through Nav1.6 expressed in mouse vas deferens myocytes (Teramoto et al., 2012; Teramoto and Yotsu‐Yamashita, 2015). We attempted to reproduce the remarkable activity of 4,9‐anhydroTTX (4) and administered the compound to Nav1.6, as well as TTX‐sensitive Nav1.4 and TTX‐resistant Nav1.5 for comparison. However, we observed that 300 nM 4,9‐anhydroTTX (4) inhibited 51 ± 10% of Nav1.6 (Supporting Information Table S1), and the IC50 value was 294 ± 25 nM (Table 1). The sodium currents for Nav1.4 and Nav1.5 were also reduced by 3.4 ± 0.2% and 3.1 ± 0.8% (n = 3), respectively (Supporting Information Table S1). In addition, no other 4,9‐anhydrotype analogues (5, 6 and 10–12) inhibited Nav1.4 and Nav1.5 (Table 1).

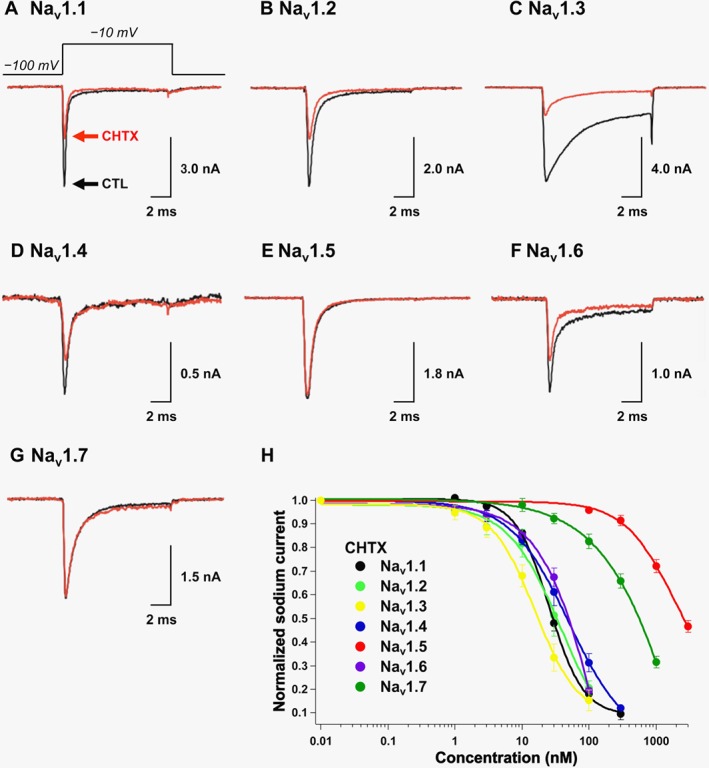

Inhibition of VSSC subtypes by chiriquitoxin and reduced binding of chiriquitoxin to Nav1.7

CHTX (2) is a TTX analogue with a glycine functionality connected to C11 (Kao et al., 1981; Yotsu et al., 1990) that is known to inhibit both voltage‐sensitive potassium channels and sodium channels (Kao et al., 1981; Yang and Kao, 1992). Our study presents the first investigation of CHTX (2) subtype selectivity. The initial screening of Nav1.1−Nav1.7 was conducted using 30 nM CHTX (2), which was found to inhibit Nav1.1 (Figure 3A), Nav1.2 (Figure 3B), Nav1.3 (Figure 3C), Nav1.4 (Figure 3D) and Nav1.6 (Figure 3F) by 52 ± 3% (n = 5), 63 ± 8% (n = 3), 72 ± 3% (n = 9), 40 ± 6% (n = 3), 33 ± 4% (n = 4) and 7.9 ± 2.2% (n = 10) respectively (n = 3), whereas for Nav1.5, 5.3 ± 1.0% inhibition (n = 3) was observed for 100 nM CHTX (2) (Figure 3E). The dose–response relationship was deduced for CHTX (2) and Nav1.1−Nav1.7; their IC50 values were 2–19‐fold greater than those for TTX (1, Table 1). However, it should be noted that Nav1.7 was approximately 34‐fold less sensitive to CHTX (2) than Nav1.3 (P < 0.05, Table 1).

Figure 3.

Inhibitory effects of CHTX (2) on Nav1.1–Nav1.7 expressed in HEK293T cells. The sodium currents in (A) Nav1.1, (B) Nav1.2, (C) Nav1.3, (D) Nav1.4, (E) Nav1.5, (F) Nav1.6 and (G) Nav1.7 were recorded in the absence (black line) and presence (red line) of CHTX (2). The CHTX concentration was 30 nM in (A−D, F, G) and 100 nM in (E). (H) The dose‐dependent inhibitory effects of CHTX (2) on Nav1.1, Nav1.2, Nav1.3, Nav1.4, Nav1.5, Nav1.6 and Nav1.7 are shown.

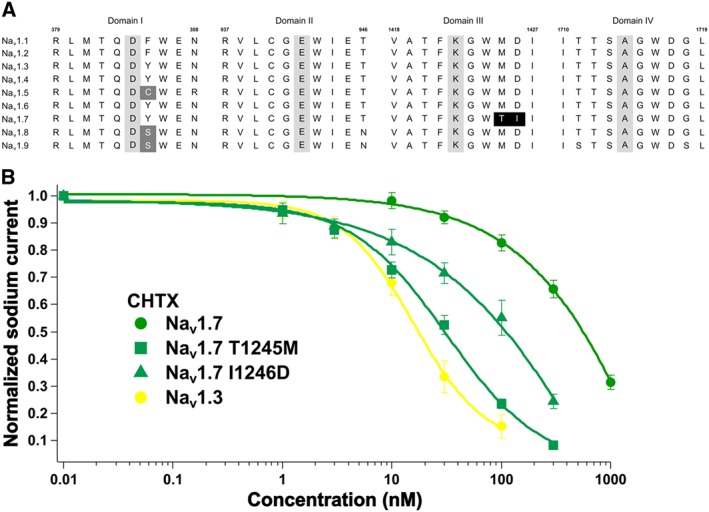

Alignment of the amino acid residues for the TTX binding sites from domain I to domain IV was performed to determine the molecular determinants that generated the reduced binding of CHTX (2) to Nav1.7. As shown in Figure 4A, most of the amino acid sequences of the TTX binding sites were highly conserved from Nav1.1 to Nav1.7, except Thr1425 and Ile1426 in Nav1.7, which occurred where Met1425 and Asp1426 were positioned in other subtypes. Thr1425 and Ile1426 in Nav1.7 were mutated to Met and Asp, respectively, and the inhibitory effect of CHTX (2) on the mutant was evaluated (Figure 4B). CHTX (2) inhibited Nav1.7 T1425M and Nav1.7 I1426D with IC50 values of 30 ± 2 nM (n = 7, P < 0.05, significantly different from Nav1.7) and 94 ± 18 nM (n = 7, P < 0.05, significantly different from Nav1.7) respectively. Thus, the T1425M and I1426D mutations decreased the IC50 by 16‐fold and 5‐fold, respectively, and CHTX (2) exhibited a comparable affinity for Nav1.7 T1425M and Nav1.3.

Figure 4.

An evaluation of the molecular determinants for the reduced binding of CHTX (2) to Nav1.7. (A) An alignment of the Nav sequences at the TTX‐binding sites from domains I to IV; the letters represent the amino acid residues. The numbers 379, 937, 1418 and 1710 indicated above the first residue in each domain, and 388, 946, 1427 and 1719 above the last residue in each domain are based on those in Nav1.2. The letters in the grey background are the aspartate‐glutamate‐lysine‐alanine (DEKA) residues important for ion selectivity, and the white letters ‘C’ and ‘S’ in the grey background indicate the residue responsible for the reduced binding of TTX (1). The white letters ‘T’ and ‘I’ in the black background represent the key residues for the reduced binding of CHTX (2) identified in the present study. (B) The dose‐dependent inhibition of Nav1.3, Nav1.7, Nav1.7 T1425M and Nav1.7 I1426D by CHTX (2). The dose–response curves for Nav1.3 and Nav1.7 were identical to those in Figure 3H.

An extra glycine unit connected to C11 in CHTX (2) was speculated to be responsible for the difference in mode of action between TTX (1) and CHTX (2). However, when the dose–responses of TTX (1, Supporting Information Figure S5) and CHTX (2, Supporting Information Figure S6) were drawn at different membrane potentials and superimposed, it was shown to be less likely that TTX (1) and CHTX (2) exhibit voltage‐dependent blocks. Furthermore, use‐dependent blocks of Nav1.3 and Nav1.7 by TTX (1, Supporting Information Figure S7) and CHTX (2, Supporting Information Figure S8) were not observed.

Molecular modelling of TTX (1) and CHTX (2) was then performed using Spartan'14 (Supporting Information Figure S9). Their tricyclic scaffolds were almost superimposed, but there were differences in the side chain connected to C11. The dihedral angle of HO−C6−C11−OH was −49.9° in TTX (1) and 41.8° in CHTX (2). In contrast, the dihedral angle of HO−C6−C11−C12 in CHTX (2) was −82.5°. In addition, the distance between C6−OH and C12−O, C4−OH and C11−OH and C11−OH and C12−NH2 were 1.7, 5.3 and 3.0 Å respectively. This indicated the existence of an intramolecular hydrogen bond between C6−OH and the carboxyl functionality in CHTX (2), which directed C11−OH and/or C12–NH2 to the same spatial area where C4−OH was directed.

Discussion

In the present study, the inhibitory effects of the various TTX analogues (2–12) against each VSSC subtype were investigated for the first time to elucidate the structure–activity relationship between TTX (1) and VSSCs. The results show that the subtypes tested are largely insensitive to 8‐deoxyTTX (3), 5‐deoxyTTX (7), 5,11‐dideoxyTTX (8) and 5,6,11‐trideoxyTTX (9) at 300 nM (Supporting Information Table S1). The IC50 values determined in the present study for 5‐deoxyTTX (7), 5,11‐dideoxyTTX (8) and 5,6,11‐trideoxyTTX (9) were comparable to those determined in cell‐based assays (Satake et al., 2014). Most importantly, 5‐deoxyTTX (7), 5,11‐dideoxyTTX (8) and 5,6,11‐trideoxyTTX (9) lack the 10,7‐hemilactal scaffold (Figure 1), which appears to be necessary to achieve high affinity for VSSCs. The significance of the hydroxy functionality of 4‐OH, 6‐OH, 8‐OH and 11‐OH in TTX (1) for achieving high affinity to VSSCs was reported by Yotsu‐Yamashita et al. (Choudhary et al., 2003; Yotsu‐Yamashita et al., 2003; Kudo et al., 2014; Saruhashi et al., 2016) and proposed in modelling studies (Lipkind and Fozzard, 1994; Choudhary et al., 2003; Tikhonov and Zhorov, 2005). In addition, the present study investigated the blocking activity of VSSCs by 8‐deoxyTTX (3), a synthetic analogue of TTX (1) that has not yet been identified from natural sources, in whole‐cell patch‐clamp recordings and emphasizes the importance of hydroxyl functionality in the high‐affinity binding of TTX (1).

We were unable to reproduce the subtype‐specific action of 4,9‐anhydroTTX (4) (Rosker et al., 2007). We verified the purity of synthetic 4,9‐anhydroTTX (4) via NMR (Ohyabu et al., 2003; Nishikawa et al., 2004; Urabe et al., 2006) and used it to treat HEK293T cells expressing a single VSSC subtype; however, we observed that the working solution containing 100 nM 4,9‐anhydroTTX (4) caused inhibition of Nav1.6 (Supporting Information Figure S4) when it was stored for half a year, implying that the production of TTX (1) and 4‐epiTTX occurred, probably attributable to an equilibrium between TTX (1), 4‐epiTTX and 4,9‐anhydroTTX (4), which may not support Rosker's results. Indeed, 300 nM 4,9‐anhydroTTX (4) preferentially inhibited Nav1.6 over that of Nav1.4 and Nav1.5 (Supporting Information Table S1). Because the voltage‐dependent block of Nav1.6 by 4,9‐anhydroTTX (4) was assumed from the previous studies (Hargus et al., 2013; Rogers et al., 2016), optimization of the recording conditions might be able to restore the marked action of 4,9‐anhydroTTX (4).

Herein, we present the first report regarding the inhibitory effects of CHTX (2) on Nav1.1–Nav1.7. The IC50 values of CHTX (2) (Table 1) appear to be related to the half‐activation and/or inactivation potential of Nav1.1–Nav1.7 (Supporting Information Figure S3C), although neither CHTX (2, Supporting Information Figure S6) nor TTX (1, Supporting Information Figure S5) exhibited a voltage‐dependent action. Use‐dependent blocks of VSSCs have been characterized as a mode of action of TTX (1) (Boccaccio et al., 1999). Many studies have assessed use‐dependent blocks of VSSCs by TTX (1) with longer repetitive depolarization pulses than those used in the present study. As such, the present study applied a duration of 2 ms to the repetitive depolarization pulses and could not confirm use‐dependent blocks by TTX (1) and CHTX (2). Indeed, use‐dependent blocks of VSSCs by lidocaine, a local anaesthetic, depended on the duration period for the repetitive depolarization pulses (Nuss et al., 1995), indicating that binding of a ligand to the inactivated state of VSSCs could induce use‐dependent blocks. Thus, use‐dependent blocks of the VSSCs by TTX (1) require conditions that facilitate the binding of TTX (1) to the inactivated state of VSSCs, although TTX (1) and CHTX (2) did not apparently affect VSSC inactivation when their steady‐state VSSC blocks were being assessed (Figures 2 and 3). Further investigations are necessary to clarify the differences in mode of action between TTX (1) and CHTX (2).

We attributed the specific reduction of CHTX (2) binding to Nav1.7 to Thr1425 and Ile1426 (Figure 4A), which are located at the outer vestibule of domain III of the VSSC, where Trp1424 was predicted to contact C4−OH (Tikhonov and Zhorov, 2005). We identified differences between TTX (1) and CHTX (2) by means of molecular modelling on the side chains connected at C11 (Supporting Information Figure S9). The small dihedral angle of HO−C6−C11−OH in TTX (1) explains the interaction between these two hydroxyl functionalities and Asp1717 in domain IV of the VSSC (Lipkind and Fozzard, 1994; Tikhonov and Zhorov, 2005). In contrast, an intramolecular hydrogen bond between C6−OH and the carboxyl functionality in CHTX (2), as addressed by Yotsu et al. (1990) (Supporting Information Figure S9), indicates a loss of the hydrogen bond between C11−OH and Asp1717 (Choudhary et al., 2003), which explains the finding that CHTX (2) binding affinities for each TTX‐sensitive VSSC subtype were one order of magnitude weaker than those of TTX (1) (Table 1). C11−OH and/or C12−NH2 in CHTX (2) were directed to the same spatial area where C4−OH was directed to Trp1424; consequently, C11−OH and/or C12−NH2 were accessible to the adjacent amino acid residues of Met1425 and/or Asp1426 in Nav1.4 (Thr1425 and/or Ile1426 in Nav1.7).

These two consecutive amino acid residues are the key amino acid residues for STX (Walker et al., 2012). The rodent Nav1.4 has Met1425 and Asp1426 at these positions and shows a high affinity for STX, with an IC50 value of 2.8 ± 0.1 nM, whereas mammalian Nav1.7 has Thr1425 and Ile1426 at those positions and has a low affinity for STX (IC50 = 702 ± 53 nM). The mammalian Nav1.7 mutant carrying the T1425M and I1426D mutations had a 305‐fold increase in binding affinity for STX (IC50 = 2.3 ± 0.2 nM), which was almost identical to the IC50 value for rodent Nav1.4. We therefore propose that CHTX (2) was embedded in the binding pocket in a similar manner to that of STX (Walker et al., 2012), in which the bulky Thr residue repels CHTX (2) and the Asp residue provides electrostatic stabilization with CHTX (2) (Walker et al., 2012). The interactions between TTX (1)/STX and VSSC have been revealed experimentally or are based on models that were primarily constructed per the crystal structure of potassium channels. Thus, there is risk involved when applying CHTX (2) to the reported VSSC models to explain the high affinity binding of TTX (1). Furthermore, identification of mammalian VSSC crystal structures would be desirable to map the binding site of CHTX (2).

Overall, we confirmed the molecular determinants in TTX (1) for generating high affinity binding to VSSCs. We also propose a similar mode of action for STX and CHTX (2), which results in the discrimination of human Nav1.7 from other human TTX‐sensitive VSSCs. The binding mode should be elucidated for CHTX (2), which would illustrate a novel model for binding TTX (1) to VSSCs. A thorough systemic method might be applicable to the search for subtype‐specific blockers among TTX analogues for the development of therapeutic compounds.

Author contributions

T.T. and Y.C. (Chiba) independently conducted the whole‐cell patch‐clamp recordings. T.Y. and S.T superseded T.T. and Y.C. (Chiba) in responding to reviewer comments. M.W. analysed the data. R.S., T.I., S.T., Y.S., M.A. and T.N. conducted the organic syntheses. T.N., M.Y.‐Y. and K.K designed the research study; Y.C. (Cho) contributed essential comments; and T.T. and K.K. wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of transparency and scientific rigour

This Declaration acknowledges that this paper adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigour of preclinical research recommended by funding agencies, publishers and other organisations engaged with supporting research.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Whole‐cell patch‐clamp recordings of (A) Nav1.1, (B) Nav1.2, (C) Nav1.3, (D) Nav1.4, (E) Nav1.5, (F) Nav1.6, and (G) Nav1.7 for analysis of steady‐state activation. The common pulse sequence was shown above (A).

Figure S2 Whole‐cell patch‐clamp recordings of (A) Nav1.1, (B) Nav1.2, (C) Nav1.3, (D) Nav1.4, (E) Nav1.5, (F) Nav1.6, and (G) Nav1.7 for analysis of steady‐state inactivation. The common pulse sequence was shown above (A).

Figure S3 Analysis of (A) steady state activation and (B) steady state inactivation of Nav1.1−Nav1.7. For both of (A) and (B), data from each of Nav1.1–Nav1.7 was represented as black circles (Nav1.1), light green circles (Nav1.2), yellow circles (Nav1.3), blue circles (Nav1.4), red circles (Nav1.5), purple circles (Nav1.6), and green circles (Nav1.7). Each symbol represents the mean ± SEM (n = 3). (C) Half activation potential (Va) and half inactivation potential (Vi) were listed in the table. Each data represents the mean ± SEM (n = 3).

Figure S4 Blockade of (A and B) Nav1.6, (C) Nav1.4, and (D) Nav1.5 by 4,9‐anhydroTTX (4). The working solution of 4,9‐anhydroTTX (4) freshly prepared from the frozen stock was applied in (A) Nav1.6, (C) Nav1.4, and (D) Nav1.5, whereas 4,9‐anhydroTTX (4) prepared as the working solution a half year before was applied to (B).

Figure S5 Voltage‐dependent block of (A) Nav1.3 and (B) Nav1.7 by TTX (1). The I–V relationships were obtained in the absence (control condition) and presence of 0.3, 1, 3, 10, and 30 nM of TTX (1). The inhibition rate in the presence of TTX (1) was determined based on the control condition and plotted versus concentration of TTX (1). Each symbol represents the mean ± SEM (n = 5).

Figure S6 Voltage‐dependent block of (A) Nav1.3, (B) Nav1.7, (C) Nav1.7 T1425 M and (D) Nav1.7 I1246D by CHTX (2). The I–V relationships were obtained in the absence (control condition) and presence of 0.3, 1, 3, 10, and 30 nM of CHTX (2). The inhibition rate in the presence of CHTX (2) was determined based on the control condition and plotted versus concentration of CHTX (2). Each symbol represents the mean ± SEM (n = 5).

Figure S7 Use‐dependent blocks of Nav1.3 and Nav1.7 by TTX (1). Use‐dependent blocks of Nav1.3 in the absence (closed circles, control) and presence (open circles) of 3 nM TTX (1) with depolarizing stimuli at A) 1 Hz, B) 2 Hz, C) 5 Hz, and D) 10 Hz were investigated. Use‐dependent blocks of Nav1.7 in the absence (closed circles, control) and presence (open circles) of 10 nM TTX (1) with depolarizing stimuli at E) 1 Hz, F) 2 Hz, G) 5 Hz and H) 10 Hz were investigated. Each symbol represents mean value ± SEM (n = 5).

Figure S8 Use‐dependent blocks of Nav1.3 and Nav1.7 by CHTX (2). Use‐dependent blocks of Nav1.3 in the absence (closed circles, control) and presence (open circles) of 10 nM CHTX (2) with depolarizing stimuli at A) 1 Hz, B) 2 Hz, C) 5 Hz, and D) 10 Hz were investigated. Use‐dependent blocks of Nav1.7 in the absence (closed circles, control) and presence (open circles) of 300 nM CHTX (2) with depolarizing stimuli at E) 1 Hz, F) 2 Hz, G) 5 Hz, and H) 10 Hz were investigated. Each symbol represents mean value ± SEM (n = 5).

Figure S9 The stabilized conformations of TTX (1) and CHTX (2). The conformations were optimized with Spartan´14 version 1.1.9. (Wavefunction, Inc., Irvine, CA, United States) using a conventional personal computer. Global calculations for equilibrium geometry at ground state were performed using Molecular Mechanics on Merck Molecular Force Field 94 (MMFF94).

Table S1 Inhibitory effect of TTX analogues of 3–12 on Nav1.1–Nav1.7. Each subtype from Nav1.1 to Nav1.7 was stimulated by each TTX derivative at 300 nM. Exceptions were 30 μM of 5‐deoxyTTX (7) against Nav1.5, 3 μM of 5,11‐dideoxyTTX (8) against Nav1.3, and 1 μM of 5,11‐dideoxyTTX (8) against Nav1.5. The values in the table represent the inhibitory effect (%) of each compound on the designated Nav subtype. Each value was determined from three independent experiments except those with grey (two independent experiments) and ocher background (a single experiment).

Acknowledgements

The present study was funded by the JSPS KAKENHI of Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research (B) (JP17H02199); the Naito Foundation (K.K.); the ERATO Murata Lipid Active Structure Project, the Japan Science and Technology Agency (K.K.); a Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas ‘Chemical Biology of Natural Products’ from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan (K.K. and T.N.); and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Funding Program for the Next Generation World‐Leading Researchers (LS012) (M.Y.‐Y.). The authors thank the Riken Bioresource Centre through the National Bio‐Resource Project of the MEXT, Japan, for the supply of the HEK cell line 293T (RCB2202) and Frank H. Yu of the Graduate School of Dentistry, Seoul National University, for kindly providing the plasmid pCDM8. The authors are grateful to Professor Kaoru Yamaoka, Faculty of Rehabilitation, Hiroshima International University; Professor Noriyoshi Teramoto, Faculty of Medicine, Saga University; and Assistant Professor Shin Hamamoto, Graduate School of Engineering, Tohoku University for their technical assistance in building the electrophysiology set‐up in our laboratory.

Tsukamoto, T. , Chiba, Y. , Wakamori, M. , Yamada, T. , Tsunogae, S. , Cho, Y. , Sakakibara, R. , Imazu, T. , Tokoro, S. , Satake, Y. , Adachi, M. , Nishikawa, T. , Yotsu‐Yamashita, M. , and Konoki, K. (2017) Differential binding of tetrodotoxin and its derivatives to voltage‐sensitive sodium channel subtypes (Nav1.1 to Nav1.7). British Journal of Pharmacology, 174: 3881–3892. doi: 10.1111/bph.13985.

References

- Adachi M, Imazu T, Sakakibara R, Satake Y, Isobe M, Nishikawa T (2014a). Total synthesis of chiriquitoxin, an analogue of tetrodotoxin isolated from the skin of a dart fog. Chem A Eur J 20: 1247–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi M, Sakakibara R, Satake Y, Isobe M, Nishikawa T (2014b). Synthesis of 5,6,11‐trideoxytetrodotoxin. Chem Lett 43: 1719–1721. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Catterall WA, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE et al (2015). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Voltage‐gated ion channels. Br J Pharmacol 172: 5904–5941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir R, Argoff CE, Bennett GJ, Cummins TR (2006). The role of sodium channels in chronic inflammatory and neuropathic pain. J Pain 7: S1–S29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, Brugada J, Brugada R, Corrado D et al (2005). Brugada syndrome – report of the second consensus conference – endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Circulation 111: 659–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai M, Nishikawa T, Ohyabu N, Yamamoto N, Isobe M (2001). Stereocontrolled synthesis of (−)‐5,11‐dideoxytetrodotoxin. Tetrahedron 57: 4543–4558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagal SK, Chapman ML, Marron BE, Prime R, Storer RI, Swain NA (2014). Recent progress in sodium channel modulators for pain. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 24: 3690–3699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boccaccio A, Moran O, Imoto K, Conti F (1999). Tonic and phasic tetrodotoxin block of sodium channels with point mutations in the outer pore region. Biophys J 77: 229–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricelj VM, Connell L, Konoki K, MacQuarrie SP, Scheuer T, Catterall WA et al (2005). Sodium channel mutation leading to saxitoxin resistance in clams increases risk of PSP. Nature 434: 763–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA, Cestele S, Yarov‐Yarovoy V, Yu FH, Konoki K, Scheuer T (2007). Voltage‐gated ion channels and gating modifier toxins. Toxicon 49: 124–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA, Goldin AL, Waxman SG (2005). International Union of Pharmacology. XLVII. Nomenclature and structure‐function relationships of voltage‐gated sodium channels. Pharmacol Rev 57: 397–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Okayama H (1987). High‐efficiency transformation of mammalian‐cells by plasmid DNA. Mol Cell Biol 7: 2745–2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary G, Yotsu‐Yamashita M, Shang L, Yasumoto T, Dudley SC (2003). Interactions of the C‐11 hydroxyl of tetrodotoxin with the sodium channel outer vestibule. Biophys J 84: 287–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MJ, Bond RA, Spina D, Ahluwalia A, Alexander SPA, Giembycz MA et al (2015). Experimental design and analysis and their reporting: new guidance for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3461–3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A (2007). G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 39: 175–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargus NJ, Nigam A, Bertram EH, Patel MK (2013). Evidence for a role of Na(v)1.6 in facilitating increases in neuronal hyperexcitability during epileptogenesis. J Neurophysiol 110: 1144–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao CY, Yeoh PN, Goldfinger MD, Fuhrman FA, Mosher HS (1981). Chiriquitoxin, a new tool for mapping ionic channels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 217: 416–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo Y, Finn J, Fukushima K, Sakugawa S, Cho Y, Konoki K et al (2014). Isolation of 6‐deoxytetrodotoxin from the pufferfish, Takifugu pardalis, and a comparison of the effects of the C‐6 and C‐11 hydroxy groups of tetrodotoxin on its activity. J Nat Prod 77: 1000–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkind GM, Fozzard HA (1994). A structural model of the tetrodotoxin and saxitoxin binding‐site of the Na+ channel. Biophys J 66: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou JY, Laezza F, Gerber BR, Xiao ML, Yamada KA, Hartmann H et al (2005). Fibroblast growth factor 14 is an intracellular modulator of voltage‐gated sodium channels. J Physiol (Lond) 569: 179–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisler MH, Kearney JA (2005). Sodium channel mutations in epilepsy and other neurological disorders. J Clin Invest 115: 2010–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narahashi T, Haas HG, Therrien EF (1967). Saxitoxin and tetrodotoxin – comparison of nerve blocking mechanism. Science 157: 1441–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narahashi T, Moore JW, Scott WR (1964). Tetrodotoxin blockage of sodium conductance increase in lobster giant axons. J Gen Physiol 47: 965–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa T, Asai M, Ohyabu N, Yamamoto N, Isobe M (1999). Stereocontrolled synthesis of (−)‐5,11‐dideoxytetrodotoxin. Angew Chem Int Ed 38: 3081–3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa T, Urabe D, Isobe M (2004). An efficient total synthesis of optically active tetrodotoxin. Angew Chem Int Ed 43: 4782–4785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuss HB, Tomaselli GF, Marban E (1995). Cardiac sodium channels (hH1) are intrinsically more sensitive to block by lidocaine than are skeletal muscle (μ 1) channels. J Gen Physiol 106: 1193–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohizumi Y, Minoshima S, Takahashi M, Kajiwara A, Nakamura H, Kobayashi J (1986). Geographutoxin II, a novel peptide inhibitor of Na channels of skeletal muscles and autonomic nerves. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 239: 243–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyabu N, Nishikawa T, Isobe M (2003). First asymmetric total synthesis of tetrodotoxin. J Am Chem Soc 125: 8798–8805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M, Zidar N, Kikelj D, Kirby RW (2016). Characterization of endogenous sodium channels in the ND7‐23 neuroblastoma cell line: implications for use as a heterologous Ion channel expression system suitable for automated patch clamp screening. Assay Drug Dev Technol 14: 109–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosker C, Lohberger B, Hofer D, Steinecker B, Quasthoff S, Schreibmayer W (2007). The TTX metabolite 4,9‐anhydro‐TTX is a highly specific blocker of the Nav1.6 voltage‐dependent sodium channel. Am J Physiol Cell 293: C783–C789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saruhashi S, Konoki K, Yotsu‐Yamashita M (2016). The voltage‐gated sodium ion channel inhibitory activities of a new tetrodotoxin analogue, 4,4a‐anhydrotetrodotoxin, and three other analogues evaluated by colorimetric cell‐based assay. Toxicon 119: 72–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satake Y, Adachi M, Tokoro S, Yotsu‐Yamashita M, Isobe M, Nishikawa T (2014). Synthesis of 5‐and 8‐deoxytetrodotoxin. Chem Asian J 9: 1922–1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satin J, Kyle JW, Chen M, Bell P, Cribbs LL, Fozzard HA et al (1992). A mutant of TTX‐resistant cardiac sodium channels with TTX‐sensitive properties. Science 256: 1202–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southan C, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Alexander SPH et al (2016). The IUPHAR/BPS guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2016: towards curated quantitative interactions between 1300 protein targets and 6000 ligands. Nucl Acids Res 44: D1054–D1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan HL, Bink‐Boelkens MTE, Bezzina CR, Viswanathan PC, Beaufort‐Krol GCM, van Tintelen PJ et al (2001). A sodium‐channel mutation causes isolated cardiac conduction disease. Nature 409: 1043–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teramoto N, Yotsu‐Yamashita M (2015). Selective blocking effects of 4,9‐anhydrotetrodotoxin, purified from a crude mixture of tetrodotoxin analogues, on Nav1.6 channels and its chemical aspects. Mar Drugs 13: 984–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teramoto N, Zhu HL, Yotsu‐Yamashita M, Inai T, Cunnane TC (2012). Resurgent‐like currents in mouse vas deferens myocytes are mediated by Nav1.6 voltage‐gated sodium channels. Pflug Arch Eur J Phys 464: 493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terlau H, Heinemann SH, Stühmer W, Pusch M, Conti F, Imoto K et al (1991). Mapping the site of block by tetrodotoxin and saxitoxin of sodium channel II. FEBS Lett 293: 93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonov DB, Zhorov BS (2005). Modeling P‐loops domain of sodium channel: homology with potassium channels and interaction with ligands. Biophys J 88: 184–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urabe D, Nishikawa T, Isobe M (2006). An efficient total synthesis of optically active tetrodotoxin from levoglucosenone. Chem Asian J 1: 125–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JR, Novick PA, Parsons WH, McGregor M, Zablocki J, Pande VS et al (2012). Marked difference in saxitoxin and tetrodoxin affinity for the human nociceptive voltage‐gated sodium channel (Nav1.7). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: 18102–18107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka K, Inoue M, Miyahara H, Miyazaki K, Hirama M (2004). A quantitative and comparative study of the effects of a synthetic ciguatoxin CTX3C on the kinetic properties of voltage‐dependent sodium channels. Br J Pharmacol 142: 879–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Kao CY (1992). Actions of chiriquitoxin on frog skeletal muscle fibers and implications for the tetrodotoxin saxitoxin receptor. J Gen Physiol 100: 609–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yotsu M, Yasumoto T, Kim YH, Naoki H, Kao CY (1990). The structure of chiriquitoxin from the Costa Rican frog Atelopus chiriquiensis . Tetrahedron Lett 31: 3187–3190. [Google Scholar]

- Yotsu‐Yamashita M (2001). Chemistry of puffer fish toxin. J Toxicol Toxin Rev 20: 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Yotsu‐Yamashita M, Abe Y, Kudo Y, Ritson‐Williams R, Paul VJ, Konoki K et al (2013). First identification of 5,11‐dideoxytetrodotoxin in marine animals, and characterization of major fragment ions of tetrodotoxin and its analogs by high resolution ESI‐MS/MS. Mar Drugs 11: 2799–2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yotsu‐Yamashita M, Sugimoto A, Takai A, Yasumoto T (1999). Effects of specific modifications of several hydroxyls of tetrodotoxin on its affinity to rat brain membrane. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 289: 1688–1696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yotsu‐Yamashita M, Urabe D, Asai M, Nishikawa T, Isobe M (2003). Biological activity of 8,11‐dideoxytetrodotoxin: lethality to mice and the inhibitory activity to cytotoxicity of ouabain and veratridine in mouse neuroblastoma cells, Neuro‐2a. Toxicon 42: 557–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Whole‐cell patch‐clamp recordings of (A) Nav1.1, (B) Nav1.2, (C) Nav1.3, (D) Nav1.4, (E) Nav1.5, (F) Nav1.6, and (G) Nav1.7 for analysis of steady‐state activation. The common pulse sequence was shown above (A).

Figure S2 Whole‐cell patch‐clamp recordings of (A) Nav1.1, (B) Nav1.2, (C) Nav1.3, (D) Nav1.4, (E) Nav1.5, (F) Nav1.6, and (G) Nav1.7 for analysis of steady‐state inactivation. The common pulse sequence was shown above (A).

Figure S3 Analysis of (A) steady state activation and (B) steady state inactivation of Nav1.1−Nav1.7. For both of (A) and (B), data from each of Nav1.1–Nav1.7 was represented as black circles (Nav1.1), light green circles (Nav1.2), yellow circles (Nav1.3), blue circles (Nav1.4), red circles (Nav1.5), purple circles (Nav1.6), and green circles (Nav1.7). Each symbol represents the mean ± SEM (n = 3). (C) Half activation potential (Va) and half inactivation potential (Vi) were listed in the table. Each data represents the mean ± SEM (n = 3).

Figure S4 Blockade of (A and B) Nav1.6, (C) Nav1.4, and (D) Nav1.5 by 4,9‐anhydroTTX (4). The working solution of 4,9‐anhydroTTX (4) freshly prepared from the frozen stock was applied in (A) Nav1.6, (C) Nav1.4, and (D) Nav1.5, whereas 4,9‐anhydroTTX (4) prepared as the working solution a half year before was applied to (B).

Figure S5 Voltage‐dependent block of (A) Nav1.3 and (B) Nav1.7 by TTX (1). The I–V relationships were obtained in the absence (control condition) and presence of 0.3, 1, 3, 10, and 30 nM of TTX (1). The inhibition rate in the presence of TTX (1) was determined based on the control condition and plotted versus concentration of TTX (1). Each symbol represents the mean ± SEM (n = 5).

Figure S6 Voltage‐dependent block of (A) Nav1.3, (B) Nav1.7, (C) Nav1.7 T1425 M and (D) Nav1.7 I1246D by CHTX (2). The I–V relationships were obtained in the absence (control condition) and presence of 0.3, 1, 3, 10, and 30 nM of CHTX (2). The inhibition rate in the presence of CHTX (2) was determined based on the control condition and plotted versus concentration of CHTX (2). Each symbol represents the mean ± SEM (n = 5).

Figure S7 Use‐dependent blocks of Nav1.3 and Nav1.7 by TTX (1). Use‐dependent blocks of Nav1.3 in the absence (closed circles, control) and presence (open circles) of 3 nM TTX (1) with depolarizing stimuli at A) 1 Hz, B) 2 Hz, C) 5 Hz, and D) 10 Hz were investigated. Use‐dependent blocks of Nav1.7 in the absence (closed circles, control) and presence (open circles) of 10 nM TTX (1) with depolarizing stimuli at E) 1 Hz, F) 2 Hz, G) 5 Hz and H) 10 Hz were investigated. Each symbol represents mean value ± SEM (n = 5).

Figure S8 Use‐dependent blocks of Nav1.3 and Nav1.7 by CHTX (2). Use‐dependent blocks of Nav1.3 in the absence (closed circles, control) and presence (open circles) of 10 nM CHTX (2) with depolarizing stimuli at A) 1 Hz, B) 2 Hz, C) 5 Hz, and D) 10 Hz were investigated. Use‐dependent blocks of Nav1.7 in the absence (closed circles, control) and presence (open circles) of 300 nM CHTX (2) with depolarizing stimuli at E) 1 Hz, F) 2 Hz, G) 5 Hz, and H) 10 Hz were investigated. Each symbol represents mean value ± SEM (n = 5).

Figure S9 The stabilized conformations of TTX (1) and CHTX (2). The conformations were optimized with Spartan´14 version 1.1.9. (Wavefunction, Inc., Irvine, CA, United States) using a conventional personal computer. Global calculations for equilibrium geometry at ground state were performed using Molecular Mechanics on Merck Molecular Force Field 94 (MMFF94).

Table S1 Inhibitory effect of TTX analogues of 3–12 on Nav1.1–Nav1.7. Each subtype from Nav1.1 to Nav1.7 was stimulated by each TTX derivative at 300 nM. Exceptions were 30 μM of 5‐deoxyTTX (7) against Nav1.5, 3 μM of 5,11‐dideoxyTTX (8) against Nav1.3, and 1 μM of 5,11‐dideoxyTTX (8) against Nav1.5. The values in the table represent the inhibitory effect (%) of each compound on the designated Nav subtype. Each value was determined from three independent experiments except those with grey (two independent experiments) and ocher background (a single experiment).