Abstract

The contractile property of the myocardium is maintained by cell-cell junctions enabling cardiomyocytes to work as a syncytium. Alterations in cell-cell junctions are observed in heart failure, a disease characterized by the activation of Transforming Growth Factor beta 1 (TGFβ1). While TGFβ1 has been implicated in diverse biologic responses, its molecular function in controlling cell-cell adhesion in the heart has never been investigated. Cardiac-specific transgenic mice expressing active TGFβ1 were generated to model the observed increase in activity in the failing heart. Activation of TGFβ1 in the heart was sufficient to drive ventricular dysfunction. To begin to understand the function of this important molecule we undertook an extensive structural analysis of the myocardium by electron microscopy and immunostaining. This approach revealed that TGFβ1 alters intercalated disc structures and cell-cell adhesion in ventricular myocytes. Mechanistically, we found that TGFβ1 induces the expression of neural adhesion molecule 1 (NCAM1) in cardiomyocytes in a p38-dependent pathway, and that selective targeting of NCAM1 was sufficient to rescue the cell adhesion defect observed when cardiomyocytes were treated with TGFβ1. Importantly, NCAM1 was upregulated in human heart samples from ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy patients and NCAM1 protein levels correlated with the degree of TGFβ1 activity in the human cardiac ventricle. Overall, we found that TGFβ1 is deleterious to the heart by regulating the adhesion properties of cardiomyocytes in an NCAM1-dependent mechanism. Our results suggest that inhibiting NCAM1 would be cardioprotective, counteract the pathological action of TGFβ1 and reduce heart failure severity.

Keywords: heart failure, TGFβ1, cell adhesion, NCAM1, intercalated disc

Introduction

Heart failure is a complex disease that results from the impairment of cardiac muscle function and often develops as a consequence of chronic neurohormonal and mechanical stress. While select heart failure treatments are available to reduce neuroendocrine signaling, such therapies do not prevent death and only mildly extend lifespan [1]. Hence, a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying cardiac dysfunction is needed to aid in the development of new treatments that extend beyond neuroendocrine modulation.

The diseased heart is associated with remodeling of the intercalated discs (ID), structures responsible for transmission of contractile force between cardiomyocytes [2]. Proper organization of intercalated discs is necessary to maintain normal cell-cell interactions between myocytes and therefore preserve cardiac function [3]. Intercalated discs are composed of adherens junctions, desmosomes, and gap junctions [4]. The classical adhesion receptor present in the adherens junctions and desmosomes is composed of cadherins. The extracellular domain of cadherins promotes homophilic interactions that mediate strong myocyte-myocyte adhesion and allow proper maintenance of tissue structure [5]. In addition to cadherins, other receptors are targeted to the intercalated discs and regulate cardiomyocytes’ coupling. Specifically, connexin proteins are key components of gap junctions, structures specialized in intercellular electric coupling [6]. In the past years it has become clear that intercalated discs are dynamic structures that are a target of complex signaling events that can alter their composition and compromise their function during disease states. Indeed, mislocalization of intercalated disc proteins is observed in heart failure and contributes to cardiac dysfunction [7]. Also, numerous mutations in intercalated disc proteins have been described, resulting in alterations to intercalated disc structure and consequently increasing susceptibility to deterioration of heart pump function [8].

During chronic stress or following insults (i.e. myocardial infarction or cardiotropic viral infection) complex signaling events perturb the homeostasis of the heart [9]. During these injury conditions secreted molecules coordinate the response of the heart to stress [10]. How this response results in disruption of cell adhesion in cardiomyocytes and overall dysfunction is not clear. A master regulator of tissue stress responses is Transforming Growth Factor beta 1 (TGFβ1) [11]. Activation of TGFβ1 is observed in the injured heart and a direct role of TGFβ1 in affecting cardiomyocytes function post-stress has been proven by Koitabashi and colleagues using genetic mouse models of cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of TGFβ1 receptors [12]. However, attempts to generate gain-of-function mouse models recapitulating the pathologic effects of TGFβ1 in the myocardium have been challenging, likely because TGFβ1 activation is tightly regulated and overexpression per se is typically not sufficient to increase its activity. Indeed, TGFβ1 is secreted as part of a complex with two other polypeptides, the latent TGFβ1 binding protein (LTBP) and the latency-associated peptide (LAP), together making up the latency complex [13, 14]. Attachment of TGFβ1 to the latency complex occurs through disulfide bonds that prevent the release of active TGFβ1 and therefore limit TGFβ1 bioavailability [14]. In 2000, Nakajima and colleagues successfully generated a mouse model expressing a mutant form of TGFβ1 (cysteine-to-serine substitution at residue 33) showing increased TGFβ1 activity in the heart, but not sufficient to uncover a ventricular phenotype [15]. These results have left an unmet need to fully understand the role of TGFβ1 signaling in ventricular cardiomyocyte dysfunction.

Here we adopted a mouse model of active TGFβ1 that mimics the degree of TGFβ1 activation observed in cardiomyopathy and we report a novel mechanism of TGFβ1-mediated ventricular dysfunction through a pathway dependent on Neural Adhesion Molecule 1 (NCAM1) to facilitate defective cardiomyocyte adhesion.

Material and Methods

Procurement of human heart samples

The studies on human heart tissue were performed under the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, with oversight by the Institutional Review Boards at The Ohio State University (protocol no. 2012H0197). Failing heart samples were obtained from patients who were diagnosed with end-stage heart failure and were receiving a heart transplant at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. Non-failing hearts were obtained in collaboration with the Lifeline of Ohio Organ Procurement program from organ donors without diagnosed heart failure whose hearts were not suitable for transplantation. These donors died from causes other than heart failure. Hearts were removed from the patients/donors and immediately submersed in ice-cold cardioplegic solution containing 110 mM NaCl, 16 mM KCl, 16 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaHCO3, and 0.5 mM CaCl2. Tissues were then flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until used for this study. Biopsies from the free wall of the left ventricle were used in this study.

Mice

A tetracycline/doxycycline (Dox)-responsive binary α-myosin heavy chain (α-MHC) transgene system was used to temporally regulate expression of a constitutively active mutant form of TGFβ1 carrying a switch in cysteines 223 and 225 to serines (TGFβ1cys223,225ser) in cardiomyocytes [16, 17]. These two mutations allow TGFβ1 to escape latency and be constitutively active; therefore increasing TGFβ1 bioavailability. TGFβ1cys223,225ser mice were then crossed with cardiac-restricted α-MHC transgenic mice expressing the tetracycline transactivator (tTA) protein (all in the FVB/N background) to generate a Dox regulated transgenic system [16, 17]. Both males and females have been used throughout the study, and show no difference in phenotype. All experiments involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The Ohio State University.

Hemodynamics, echocardiography and electrocardiograms

Cardiac hemodynamic measurements were assessed via a closed chest approach using a 1.4 French Millar Pressure catheter (AD Instruments) advanced into the left ventricle through the right carotid artery [18]. In brief, mice were anaesthetized by ketamine (55 mg/kg) plus xylazine (15 mg/kg) in saline solution and placed in supine position on a heat pad. Following a midline neck incision, the underlying muscles were pulled to expose the carotid artery. Using a 4-0 suture the artery was tied and the pressure–volume catheter was advanced through the artery into the left ventricle of the heart. After 5 min of stabilization, values at baseline and stimulation at varying frequencies (4–10 Hz) were recorded. Echocardiography was performed using a VEVO 2100 Visual Sonics (Visual Sonics, Toronto) system. The mice were lightly anaesthetized (1.5% isoflurane) and wall thickness and ventricular chamber dimensions were determined through M mode using the parasternal short axis view. Subsurface electrocardiographic (ECG) recordings were obtained from mice anesthetized with 1.5% isofluorane and oxygen at a rate of 1.0 L/min. The baseline ECG was recorded at baseline and after administration of isoprenaline (0.05 mg/kg, intraperitoneally). ECGs were recorded and analyzed using LabChart 7 Pro (AD Instruments, Sidney Australia).

Cardiomyocyte isolation and treatments

Neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes (NRVM) were isolated as previously published.[19] Isolated cardiomyocytes were plated in geltrex® coated 24-well plates to be used for cellular adhesion assays or protein and RNA isolation or on MatTek® dishes for immunofluorescence. Cardiomyocytes were allowed to attach for 24 hours prior to transient transfection and treatments. Treatments included incubation with recombinant TGFβ1 (10ng/ml; R&D systems) or vehicle control for 72 hours. For knockdown studies, siRNAs scramble (CGUUAAUCGCGUAUAAACGCGUAT) or three in combination against NCAM1 (1-AAGUCACUCUGACAUGUGAAGCCTC, 2-GCAGUUUCCCUGCAGGUAGAUAUTG, 3-GUUUCCCUGCAGGUAGAUAUUGUTC) were delivered by transfection using the TransIT-X2 transfection reagent (Mirus Bio LLC). For gain of function studies empty plasmids or plasmids encoding for NCAM1 (kindly provided by Dr. Patricia Maness, UNC-Chapel Hill) were delivered by transfection using the TransIT-LT1 transfection reagent (Mirus Bio LLC).

Cellular adhesion and differential heart digestion assays

Cellular adhesion assays were performed as previously described with minor modifications [20]. Primary NRVM were plated at 90% confluence in 24-well plates and transiently transfected as noted. Cells were subsequently treated with vehicle or TGFβ1. At 72 hours post-transfection, NRVM were washed with sterile PBS and incubated with 2.4 U/mL dispase II (Roche Diagnostics, IN) for 10 minutes at 37°C. Fragmentation of released monolayers was achieved by orbital rotation (70 RPM) for 10 minutes at 37°C. The number of fragments for each condition was quantified using a dissecting microscope. The assay was repeated 6 times for each experimental condition. For differential heart digestion assay, mouse hearts were placed into pre-warmed Tyrodes buffer containing 3mg/ml of collagenase and incubated at 37°C with gentle agitation. After 2 hours the hearts were placed in fresh collagenase buffer and heart dissociation was recorded after an additional hour of gentle agitation.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), histological analysis, hydroxyproline assay and immunofluorescence

Hearts from control and TGFβ1 transgenic mice were excised and cut into appropriate size pieces for TEM studies using standard procedure [21]. Observations were made on an FEI Tecnai G2 Biotwin TEM operating at 80 kV and micrographs captured using an AMT camera. To assess intercalated disc integrity, ID length and amplitude as well as tread width and step length were measured. The number of steps and treads per ID length were calculated. In addition, the distances between membranes of opposing myocytes at adhesion, gap and desmosomal junctions were measured. Masson’s trichrome staining for fibrosis (blue) was performed using histological sections generated from paraffin-embedded hearts. Hydroxyproline content to assay for fibrosis was performed as previously described [22]. Immunohistochemistry was performed on cryosections of hearts and isolated cardiomyocytes using standard protocols. Antibodies used were N-Cadherin (Pierce 33–3900), α-Actinin (Sigma Aldrich A7732), Desmocollin-2 and -3 (Pierce 32–6200), NCAM1 (Proteintech 14255), Desmin (Pierce PA5-16705), Connexin-43 (abcam ab11370) and TGFβ1 (abcam ab92486). Percent organization of ID structures was determined using ImageJ software (NIH). First a filter was applied to the raw image to match an intensity threshold then a surface plot of fluorescence intensity was drawn and the number of IDs in a stair step or disorganized formation (multiple peaks on the surface plot) vs normal ID staining (single peak on a surface plot) per field of view was calculated.

Western blotting, ELISA and mRNA expression analysis

Standard western blot analysis was performed from isolated cardiomyocytes, mouse heart and human heart homogenates. Antibodies used were N-cadherin (Pierce 33–3900), GAPDH (Sigma G8795), NCAM1 (Proteintech 14255), and Connexin-43 (abcam ab11370). Densitometry of the western blots was performed using ImageJ software. GAPDH served as loading controls for normalization purposes. TGFβ1 ELISA was performed on heart homogenates using a kit purchased from R&D Systems (SMB100B). RNA was extracted from ventricles or isolated myocytes using Trizol. Reverse transcription was performed using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). Selected gene expression differences were analyzed by real-time qPCR using SYBR green (Biorad). Primers used were: mouse Ncam1 (5′-CGAACGGAGGAAGAACGGA-3′, 5′-CCGTCTTGACTTCAGTTGGC-3′); rat Ncam1 (5′-TCCTGAACAAGTGTGGCCTG-3′, 5′-CTCCTCCGTTCGGACCTCTA-3′); Cdh2 (5′-CGTGGGAATCAGACGGCTAG-3′, 5′-GCTGCCCTCGTAGTCAAAGA-3′); Dsc2 (5′-GAGGGGCTGGCTATCATCAC-3′, 5′-ACTACAGCAACCCACAGAGC-3′); Dag1 (5′-TGCACTCAGTTCTCTCCGAC-3′, 5′-GGTCCCAGTGTAGCCAAGAC-3′); Dsg2 (5′-AACACAGAAGCCTCCTCACC-3′, 5′-AAGGTCGTCTTCCCCATTGT-3′); Cldn1 (5′-TTCTATGACCCCTTGACCCC-3′, 5′-CCGTGGTGTTGGGTAAGAGG-3′); Ocln (5′-CAGGCAGAACTAGACGACGT-3′, 5′-CCGTCTGTCATAATCTCCCACC-3′); mouse Rpl7 (5′-TGGAACCATGGAGGCTGT-3′, 5′-CACAGCGGGAACCTTTTTC-3′); rat Rpl7 (5′-AAAAGAAGGTTGCCGCTG-3′, 5′-TAGAAGTTGCCAGCTTTCC-3′). Quantified mRNA levels were normalized to Rpl7 and expressed relative to controls.

Statistics

All results are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed with unpaired 2-tailed t-test (for 2 groups) and 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction (for groups of 3 or more). P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

TGFβ1 activation induces ventricular dysfunction

TGFβ1 is induced in the injured heart and is considered a central player in cardiac diseases [17, 23]. Indeed, we observed increase in TGFβ1 activity in human failing hearts by ELISA (Figure 1A). We have also found that cardiomyocytes are a source for TGFβ1 in human failing myocardium (Supplemental Figure 1A and B). To mimic the TGFβ1 activation occurring during cardiomyopathies and to study the direct mechanistic role of TGFβ1 in cardiomyocytes we have adopted a transgenic mouse model for cardiac-specific expression of active TGFβ1 under the control of α-myosin heavy chain promoter. Considering that TGFβ1 is secreted as a latent complex (latency-associated peptide or LAP) that prevents it from being bioavailable, we utilized a mutant construct where introduction of serine residues at positions 223 and 225 (cys223,225ser) allows for production of bioavailable TGFβ1 (Figure 1B and C). Unrepressed transgene expression led to a significant increase in TGFβ1 activity in the heart of TGFβ1 transgenic mice (TG), which was evident at postnatal day 5 and further increased at postnatal day 10 and 20 (Figure 1D). Importantly, the levels of active TGFβ1 in the TG were sufficient to recapitulate the naturally occurring TGFβ1 activity in human heart failure. Activation of TGFβ1 in the murine heart resulted in decreased survival in the absence of cardiac hypertrophy with an average life span of 21 days in TGFβ1 TG mice (Figure 1E and Supplemental Figure 2A–C). Lack of cardiac remodeling was further confirmed by echocardiographic measurements of ventricular wall thickness and ventricular chamber dimension (Supplemental Figure 2D–F). Also, we observed a significant increase in collagen deposition in TGFβ1 TG hearts both by Masson Trichrome staining and quantification of hydroxyproline content (Supplemental Figure 2G–I). To assess if activation of TGFβ1 was sufficient to impair cardiac contractility we performed invasive hemodynamics studies. We found that both systolic function (measured by dP/dT max) and relaxation (measured by dP/dT min) were compromised in TGFβ1 TG mice (Figure 1F and G). We then performed electrocardiograms (ECG) at baseline and following isoproterenol stimulation to assess if TGFβ1 activation induced electrical abnormalities in the heart. TGFβ1 TG showed significant prolongation of PR and QT intervals at baseline; in addition, their isoproterenol response revealed lower increase in heart rate and prolonged RR intervals (Table 1). We have also observed arrhythmic events in 50% of TGFβ1 TG mice tested, independently from isoproterenol stimulation. Additionally, the TGFβ1 TG mice showed typical heart failure signs, such as lack of grooming, difficulty breathing, and lethargy (Supplemental video 1 and Supplemental Figure 2J). Thus, activation of TGFβ1 in the heart is sufficient to deteriorate cardiac function.

Figure 1. TGFβ1 activation induces ventricular dysfunction.

A, ELISA for TGFβ1 activity in human non-failing (NF) or failing (F) hearts. B–C, Schematic of wild type (WT) TGFβ1 latent complex (B), and mutant TGFβ1 construct used for generation of transgenic (TG) mice (C). D, ELISA for TGFβ1 activity in WT and TGFβ1 TG mouse hearts at postnatal day 5 (d5), day 10 (d10) or day 20 (d20). E, Survival curves for WT and TGFβ1 TG mice. F–G, Hemodynamics measurement of ventricular contractility (dP/dT max; F) and cardiac relaxation (dP/dT min; G) in WT and TGFβ1 TG. H–I, Representative TEM images of intercalated discs (ID) in WT and TGFβ1 TG. Scale bar = 500 nm. J–M, quantification of ID length (J), amplitude (K), number of steps (L) and number of treads (M). Number of animals used is indicated in each graph. For TEM quantification, number of animals = 3 per genotype, with number of IDs analyzed indicated in each graph. *P<0.05 versus WT.

Table 1.

Echocardiographic analyses of TGFβ1 TG and control mice.

| TGFβ1 | WT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −iso | +iso | −iso | +iso | |

| Heart Rate (bpm) | 370.2 +/− 21.5 | 422 +/− 27.5*# | 405 +/− 34.4 | 556.0 +/− 38.6# |

| RR Interval (ms) | 166.4 +/− 9.9 | 145.9 +/− 9.1*# | 153.9 +/− 11.8 | 111.5 +/− 9.1# |

| PR Interval (ms) | 33.3 +/− 2.6* | 32.5 +/− 2.5* | 29.9 +/− 1.1 | 28.3 +/− 1.3 |

| QRS Interval (ms) | 7.9 +/− 0.6 | 8.3 +/− 0.7 | 8.1 +/− 0.3 | 8.0 +/− 0.3 |

| QT Interval (ms) | 21.4 +/− 2.0* | 22.3 +/− 2.7 | 17.0 +/− 0.9 | 18.9 +/− 0.1# |

TG: n = 6; WT: n = 6

p < 0.05 compared to WT same treatment

p< 0.05 compared to non-iso baseline

TGFβ1 alters intercalated disc structure and composition

To more deeply understand the origin of TGFβ1 driven contractile dysfunction, we examined cardiomyocyte ultrastructure by transmission electron microscopy and found defective intercalated discs (IDs) in TGFβ1 TG myocardium, suggestive of impaired cell-cell adhesion (Figure 1H–M and Table 2). Specifically, although ID length was unchanged, we found reduced ID amplitude (peak to peak distances) in TGFβ1 TG (Figure 1J and K). Also, we observed an increased number of ID steps and treads, resulting in a staircase appearance in cardiomyocytes from TGFβ1 TG (Figure 1L and M). To ascertain the mechanistic function of TGFβ1 in cardiomyocytes we further analyzed their IDs. Immunofluorescence analysis for adherens junctions, gap junctions, and desmosomes (by staining with N-cadherin, connexin-43 and desmocollin-2, respectively) revealed disorganized IDs in TGFβ1 TG hearts (Figure 2A–G). Specifically, cell-cell junctions from TGFβ1 TG hearts showed a typical dysfunctional staircase ID structure (multiple peaks in the fluorescence intensity surface plot). Indeed, approximately 75% of all ID analyzed showed disorganized adherens junctions, gap junctions, and desmosomes (Figure 2G). To understand if TGFβ1 alters ID composition through transcriptional regulation we assessed the expression of membrane proteins that are known to localize to cardiomyocyte adhesion compartments at either baseline or during disease. We found a specific induction of Neural Adhesion Molecule 1 (NCAM1) messenger RNA in the transgenic hearts (Figure 2H). All other adhesion molecules tested, including ID cadherins, showed no change (Figure 2H). Western blot analysis also revealed induction of NCAM1 protein by TGFβ1 (Figure 2I). NCAM1, also called CD56, is a cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion receptor that can be expressed as three main isoforms (NCAM-120kDa, NCAM-140kDa and NCAM-180kDa) [24]. We found that TGFβ1 upregulated NCAM-140kDa and NCAM-180kDa isoforms in the heart (Figure 2I), and that TGFβ1 activity correlated with NCAM1 expression (Figure 2J). Cardiac expression of NCAM1 was reported to occur with cardiomyopathy, although cell-specificity and consequences of this induction are undefined [25, 26].

Table 2.

Characteristics of Intercalated Discs in TGFβ1 TG and control mice.

| TGFβ1 TG | WT | |

|---|---|---|

| ID Amplitude (nm) | 251 +/− 29.0* | 552 +/− 46.1 |

| ID Length (μm) | 30.5 +/− 3.5 | 33.2 +/− 4.0 |

| Tread Width (μm) | 1.66 +/− 0.16* | 3.11 +/− 0.29 |

| Step Length (μm) | 1.98 +/− 0.18 | 1.90 +/− 0.25 |

| Number of Steps/ID Length | 0.21 +/− 0.03* | 0.10 +/− 0.01 |

| Number of Treads/ID Length | 0.24 +/− 0.04* | 0.13 +/− 0.01 |

| Membrane Distance at AJ (nm) | 23.9 +/− 0.75 | 26.1 +/− 0.49 |

| Membrane Distance at DJ (nm) | 22.9 +/− 0.82 | 26.4 +/− 1.18 |

| Membrane Distance at GJ (nm) | 108.2 +/− 31.7* | 10.4 +/− 0.51 |

TG: n = 3 mice, 95 cells; WT: n = 3 mice, 87 cells;

p < 0.01;

Intercalated Disc (ID), Adherens Junction (AJ), Desmosomal Junction (DJ), Gap Junction (GJ)

Figure 2. TGFβ1 alters intercalated disc structure and composition.

A–F, Immunofluorescence analysis for the indicated ID proteins in WT and TGFβ1 TG hearts. N-cadherin (green; A,B) was used to specifically stain adherens junctions; connexin 43 (green; C,D) was used for gap junctions; desmocollin-2 (green; E,F) was used to stain for desmosome junctions. Desmin (red, A–B and E–F) and α-actinin (red, C–D) were used to counterstain cardiomyocytes. Original magnification 40x. Scale bar = 20 μm. a–f, Representative fluorescence intensity surface plots used to quantify ID organization. G, Quantification of ID organization for adherens junctions (AJ), gap junctions (GJ) and desmosomal junctions (DJ). H, qPCR analysis of mRNA levels for the indicated adhesion molecules (Cdh2=cadherin-2/N-cadherin; Dsc2=desmocollin-2; Dsg2=desmoglein-2; Dag1=dystroglycan-1; Cldn=claudin; Ocln=occludin; Ncam1=neural cell adhesion molecule-1) normalized to Rpl7 housekeeping gene. I, Western blot analysis for the indicated proteins. Densitometry quantification (I’) was performed using ImageJ software (NCAM1-140kDa and NCAM1-180kDa were both included in the analysis). J, Correlation between NCAM1 expression and TGFβ1 activity in mouse transgenic (TG) hearts. Number of animals used is indicated in each graph. For quantification of ID % organization, number of animals = 3 per genotype, with number of IDs analyzed indicated in each graph. *P<0.05 versus WT.

Thus, activation of TGFβ1 in the heart induces NCAM1 expression and alters ID morphology.

NCAM1 mediates TGFβ1-dependent adhesion defects in ventricular cardiomyocytes

Considering that TGFβ1 induced alterations in ID structure and composition in the heart, we tested if TGFβ1 alters heart integrity. Specifically, we assessed the response of WT and TGFβ1 TG hearts to collagenase digestion and found that activation of TGFβ1 led to accelerate tissue disruption post-digestion in TGFβ1 TG hearts (Figure 3A and B). We then tested if TGFβ1 specifically affects the adhesion properties of cardiomyocytes. To this end, we isolated primary rat ventricular myocytes and tested their adhesion strength in response to TGFβ1 treatment. We saw that indeed TGFβ1 reduced cell-cell adhesion in cardiomyocytes, as evidenced by the higher number of fragments observed in TGFβ1 treated myocytes when enzymatically and mechanically stimulated to dissociate with a dispase assay (Figure 3C and D). To examine if the observed defect in cardiomyocyte adhesion following TGFβ1 treatment implicates NCAM1 expression, we tested if TGFβ1 could induce NCAM1 directly in cardiomyocytes. We found that the expression of NCAM-140kDa and NCAM-180kDa proteins was significantly upregulated in cardiomyocytes treated with TGFβ1 (Figure 3E). To more deeply understand the downstream pathways involved in NCAM1 induction, we then treated isolated cardiomyocytes with TGFβ1 in the presence of specific inhibitors for canonical (SMAD-dependent) and non-canonical (SMAD-independent) signaling pathways. We found that inhibition of p38 MAPK (component of the non-canonical TGFβ1 pathway) was sufficient to inhibit NCAM1 induction following TGFβ1 treatment, while SMAD inhibition had no significant effect (Figure 3F). To assess if TGFβ1-mediated expression of NCAM1 could interfere with cardiomyocyte adhesion we first analyzed NCAM1 localization in isolated myocytes. By immunofluorescence we revealed NCAM1 localization at cell-cell junctions in cardiomyocytes treated with TGFβ1 (Figure 3G and H). To assess the contribution of NCAM1 to TGFβ1-mediated cell-cell adhesion fragility, we then knocked-down NCAM1 in isolated cardiomyocytes and tested if inhibition of NCAM1 expression rescued the adhesion phenotype observed post-treatment with TGFβ1. As assessed by western blotting NCAM1 was successfully downregulated by siRNA (Figure 3I). More importantly, the loss of NCAM1 was efficient to abrogate TGFβ1’s ability to inhibit cell-cell adhesion when dispase assays were performed in isolated cardiomyocytes (Figure J–L). To then assess if NCAM1 can directly affect cell-cell adhesion in cardiomyocytes, we overexpressed NCAM1 in isolated cardiomyocytes (Figure 3M). We found that NCAM1 upregulation is sufficient to deteriorate the adhesion properties of cardiomyocytes as shown by higher fragment numbers post dispase assay (Figure N and O).

Figure 3. NCAM1 mediates TGFβ1-dependent adhesion defect in ventricular cardiomyocytes.

A–B, Differential digestion assay for heart tissue integrity in WT and TGFβ1 TG mice. C–D, Dispase assay for adhesion properties of isolated neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVM) following control (Ctrl) or TGFβ1 treatment. Quantification of number of fragments generated following dispase assay is shown in D. E, Western Blot for NCAM1, connexin-43 and GAPDH loading control in NRVM with or without TGFβ1 treatment. Quantification (E’) was performed with densitometry analysis using ImageJ software and represented normalized to GAPDH expression. F, qPCR for Ncam1 mRNA levels normalized to Rpl7 housekeeping gene. NRVM were treated with TGFβ in presence of vehicle, SMAD inhibitor (SMADi) or p38-MAPK inhibitor (p38i). G–H, Immunofluorescence analysis of NCAM1 localization (green) and α-actinin (red) in NRVM following control or TGFβ1 treatment, arrow indicates areas of cell-cell junctions. Scale bar = 20 μm. I, Western blot for the indicated proteins from NRVM treated with control siRNA or siRNA against Ncam1. J–L, Dispase assay for adhesion properties of NRVM following control or TGFβ1 treatment with or without Ncam1 knock-down. Quantification of number of fragments generated following dispase assay is shown in J. M, Western blot for the indicated proteins from NRVM transfected with control or Ncam1 plasmids. N–O, Dispase assay for adhesion properties of NRVM following NCAM1 upregulation. Quantification of number of fragments generated following dispase assay is shown in N. Number of biological replicates is indicated in each graph. *P<0.05 versus Control same treatment; #P<0.05 versus Vehicle (Figure 3F) or siRNA control same treatment (Figure 3J).

These results revealed that TGFβ1 affects the cell-cell adhesion properties of cardiomyocytes in an NCAM1-dependent manner.

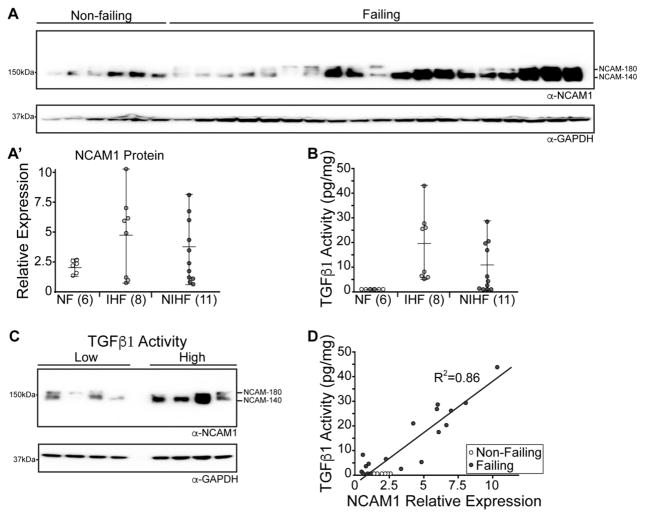

NCAM1 is induced in human failing hearts proportionally to TGFβ1 activity

Our data suggested a TGFβ1-NCAM1 axis acting on cardiomyocyte intercalated disc structure and cell-cell adhesion. This prompted us to test the role of NCAM1 in relation to TGFβ1 activation in the human failing heart. We first tested if NCAM1 protein levels were elevated in human heart failure samples of various etiologies (clinical data listed in Supplemental Table 1). We found that NCAM1 was increased in a number of ischemic and non-ischemic left ventricle samples, although variability was observed (Figure 4A). To understand the origin of this variability we tested TGFβ1 activity by ELISA in the same set of human heart samples. Similar to what we observed for NCAM1 levels, we found that TGFβ1 was activated to various degrees in both ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy (Figure 4B). We then reasoned that NCAM1 levels could be dependent upon the degree of TGFβ1 activity. Indeed, when we assessed NCAM1 protein expression in human failing heart samples with low and high TGFβ activity we observed upregulation of NCAM1 in samples where TGFβ1 was most active (Figure 4C). We then calculated how NCAM1 expression correlates to TGFβ1 activity throughout the entire dataset and found a powerful positive correlation linking NCAM1 expression to TGFβ1 activity (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. NCAM1 is induced in human failing hearts proportionally to TGFβ1 activity.

A, Western blot for NCAM1 and GAPDH loading control from human non-failing and failing hearts. Densitometry quantification was performed on human hearts grouped into non-failing (NF), ischemic heart failure (IHF) and non-ischemic heart failure (NIHF). B, ELISA for TGFβ1 activity in human samples from non-failing (NF), ischemic heart failure (IHF) and non-ischemic heart failure (NIHF). C, Western blot analysis of NCAM1 protein expression in human heart failure samples showing low or high TGFβ1 activity. GAPDH was used as loading control. D, Correlation between NCAM1 expression and TGFβ1 activity in human heart failure samples.

Overall, our findings revealed a novel mechanism by which TGFβ1 induces NCAM1 levels and regulates cell-cell adhesion in cardiomyocytes.

Discussion

The TGFβ1 signaling pathway has been recognized as critical in the context of stress responses as well as in the development of multiple organ systems, including the heart [27]. The importance of understanding how TGFβ1 exerts its downstream action is demonstrated by the fact that perturbation of TGFβ1 signaling is known to occur in disease states in the heart and beyond. Also, genetic mutations affecting TGFβ1 activation are a primary cause of disease or act as disease modifiers in both cardiac and skeletal muscle [28, 29]. Although therapeutic strategies have been developed in order to counteract the pathologic consequences of TGFβ1 activation, the complexity of TGFβ1 biology gives rise to numerous potential adverse effects that a global inhibition strategy can carry. Indeed, studies utilizing neutralizing antibodies against TGFβ1 have shown that their detrimental effect on the heart overcomes the potential benefit of such a global therapy against TGFβ1 [12]. With this knowledge, it is of primary importance to dissect the specific downstream mechanisms responsible for the TGFβ1-dependent pathology as this knowledge can lead to the development of therapies that target TGFβ1’s downstream harmful actions without affecting its positive roles.

To date, different mouse models have been generated to study the consequences of TGFβ1 activity in the heart, albeit their results are limited by the amount of increased TGFβ1 activity [15, 30, 31]. By using a double mutant construct for TGFβ1 we were able to obtain high levels of bioavailable TGFβ1, with levels similar to that seen in failing human hearts, and observe a ventricular phenotype in these mice. Our data connects, for the first time, TGFβ1 signaling to changes in ID structure and cell-cell adhesion in cardiomyocytes. Previous studies had focused their attention on the ability of TGFβ1 to activate a pro-fibrotic program, which is likely dependent on fibroblast activation [32]. In the heart, it was shown that atria are more prone to develop fibrosis in response to TGFβ1, and that atrial deposition of fibrotic tissue can promote a predisposition for atrial fibrillation [31]. Our results show that when levels of TGFβ1 activation mimic stress responses in the heart, ventricular fibrosis is observed and even more importantly the role of TGFβ1 in directly affecting ventricular cardiomyocytes is elucidated. Using human heart samples, as well as our mouse model for TGFβ1 activation in the heart and isolated rat cardiomyocytes we revealed that TGFβ1 induced the expression of NCAM1 in cardiomyocyte’s cell-cell junctions and that this induction is responsible for deterioration of cardiomyocyte to cardiomyocte adhesion.

NCAM1 was reported to be induced in ischemic heart failure, although the mechanism for its induction and its functional consequences were unknown [25, 26, 33, 34]. Here, we found that NCAM1 induction is driven by TGFβ1 and functions to modulate the cell adhesion properties of cardiomyocytes. A previous study utilizing genetic knock-down of TGFβ1 receptors in cardiomyocytes showed that the signaling of TGFβ1 directly to cardiomyocytes is an important contributor to TGFβ1-mediated cardiac dysfunction and affects the cardiac response to stress [12]. Interestingly, this study demonstrated that the non-canonical TGFβ1 pathway plays a primary role in cardiomyocytes [12]. Similarly, we found that in isolated cardiomyocytes non-canonical TGFβ1 signaling is responsible for TGFβ1 induction of NCAM1 expression, further supporting the hypothesis that inhibiting non-canonical TGFβ1 signaling would counteract the deleterious effect of TGFβ1 in cardiomyocytes. It is possible that in the heart, SMAD-dependent canonical signaling plays a more important role in cardiac fibroblasts and collagen deposition. Our results highlight a previously unrecognized role for the TGFβ1 non-canonical pathway in modulating the composition of cell-cell junctions in the heart that could explain the impaired cardiac contractility observed in mice exposed to active TGFβ1. It is possible that TGFβ1 acts by favoring adhesion to extracellular matrix, compromising cardiomyocytes’ ability to adhere to each other. This type of interference would prevent their necessary cell-cell adhesion, which is an essential feature for maintenance of contractile force and electric conduction.

By using human heart tissues we demonstrated that NCAM1 is upregulated in both ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy in a TGFβ1 dependent manner. To our knowledge this is the first study reporting a mechanistic relationship between TGFβ1 and NCAM1 in cardiomyocytes. Also, the functional consequences of NCAM1 expression in the heart were unknown and we now show that NCAM1 is responsible for TGFβ1-mediated cell-cell adhesion impairment in isolated ventricular myocytes. In cancer cells, as well as other cell types such as epithelial and neural cells, a link between TGFβ1 and NCAM1 expression has been observed [35–38]. In these contexts, TGFβ1-dependent induction of NCAM1 primarily promoted cell migration, a process that is dependent upon the ability of cells to adhere to the extracellular matrix. In specialized non-migratory cells such as cardiomyocytes, NCAM1 localization to cell-cell junctions might lead to aberrant cell behaviors where cardiomyocytes now favor attachment to the extracellular matrix compromising cell-cell adhesion. Indeed, our results showed that NCAM1 expression at cell-cell junctions mediates TGFβ1-dependent disruption of cardiomyocyte to cardiomyocyte adhesion.

Our study proposes NCAM1 as valid therapeutic target for heart failure treatment and provides a novel way to counteract the deleterious effects of TGFβ1 activation in the heart.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

TGFβ1 affects intercalated disc composition leading to ventricular dysfunction.

TGFβ1 alters cardiomyocyte adhesion through NCAM1.

NCAM1 in failing human hearts is driven by TGFβ1 activation.

Targeting NCAM1 counteracts TGFβ1 deleterious effects in the heart.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank: Susan Montgomery, Erin Bumgardner, and Emily Jarvis for their help in consenting the patients for this study; Abraham Zawodni (Lifeline of Ohio) for help with obtaining clinical correlates for the donor hearts; Nathaniel Murphy for help with mouse phenotyping; Dr. Patricia Maness (UNC-Chapel Hill) for providing Ncam1 plasmids.

Sources of funding: This work was supported by grants from the NIH R00HL121284 and R01HL136951 (to F.A.), R00HL116778 (to M.A.A.), R01HL113084 (to P.M.L.J.), T32GM068412 (to J.M.P.).

Non-standard abbreviations

- TGFβ1

transforming growth factor beta 1

- NCAM1

neural cell adhesion molecule 1

- TG

transgenic mice

- Dox

doxycycline

- MHC

myosin heavy chain

- WT

wild-type

- ID

intercalated disc

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pugh PJ, Jones RD, Jones TH, Channer KS. Heart failure as an inflammatory condition: potential role for androgens as immune modulators. European journal of heart failure. 2002;4:673–80. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(02)00162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinali C, Bennett HJ, Davenport JB, Caldwell JL, Starborg T, Trafford AW, et al. Three-dimensional structure of the intercalated disc reveals plicate domain and gap junction remodeling in heart failure. Biophys J. 2015;108:498–507. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyon RC, Zanella F, Omens JH, Sheikh F. Mechanotransduction in cardiac hypertrophy and failure. Circ Res. 2015;116:1462–76. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vermij SH, Abriel H, van Veen TA. Refining the molecular organization of the cardiac intercalated disc. Cardiovasc Res. 2017;113:259–75. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvw259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perez TD, Nelson WJ. Cadherin adhesion: mechanisms and molecular interactions. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2004:3–21. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-68170-0_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stroemlund LW, Jensen CF, Qvortrup K, Delmar M, Nielsen MS. Gap junctions - guards of excitability. Biochem Soc Trans. 2015;43:508–12. doi: 10.1042/BST20150059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J. Alterations in cell adhesion proteins and cardiomyopathy. World J Cardiol. 2014;6:304–13. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v6.i5.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calore M, Lorenzon A, De Bortoli M, Poloni G, Rampazzo A. Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy: a disease of intercalated discs. Cell Tissue Res. 2015;360:491–500. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-2015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kehat I, Molkentin JD. Molecular pathways underlying cardiac remodeling during pathophysiological stimulation. Circulation. 2010;122:2727–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.942268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou B, Honor LB, He H, Ma Q, Oh JH, Butterfield C, et al. Adult mouse epicardium modulates myocardial injury by secreting paracrine factors. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1894–904. doi: 10.1172/JCI45529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leask A, Abraham DJ. TGF-beta signaling and the fibrotic response. FASEB J. 2004;18:816–27. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1273rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koitabashi N, Danner T, Zaiman AL, Pinto YM, Rowell J, Mankowski J, et al. Pivotal role of cardiomyocyte TGF-beta signaling in the murine pathological response to sustained pressure overload. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2301–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI44824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinz B. The extracellular matrix and transforming growth factor-beta1: Tale of a strained relationship. Matrix Biol. 2015;47:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robertson IB, Horiguchi M, Zilberberg L, Dabovic B, Hadjiolova K, Rifkin DB. Latent TGF-beta-binding proteins. Matrix Biol. 2015;47:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakajima H, Nakajima HO, Salcher O, Dittie AS, Dembowsky K, Jing S, et al. Atrial but not ventricular fibrosis in mice expressing a mutant transforming growth factor-beta(1) transgene in the heart. Circ Res. 2000;86:571–9. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanbe A, Gulick J, Hanks MC, Liang Q, Osinska H, Robbins J. Reengineering inducible cardiac-specific transgenesis with an attenuated myosin heavy chain promoter. Circulation research. 2003;92:609–16. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000065442.64694.9F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Accornero F, van Berlo JH, Correll RN, Elrod JW, Sargent MA, York A, et al. Genetic Analysis of Connective Tissue Growth Factor as an Effector of Transforming Growth Factor beta Signaling and Cardiac Remodeling. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35:2154–64. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00199-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang B, Davis JP, Ziolo MT. Cardiac Catheterization in Mice to Measure the Pressure Volume Relationship: Investigating the Bowditch Effect. J Vis Exp. 2015:e52618. doi: 10.3791/52618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogers TB, Gaa ST, Allen IS. Identification and characterization of functional angiotensin II receptors on cultured heart myocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1986;236:438–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hobbs RP, Amargo EV, Somasundaram A, Simpson CL, Prakriya M, Denning MF, et al. The calcium ATPase SERCA2 regulates desmoplakin dynamics and intercellular adhesive strength through modulation of PKCα signaling. FASEB J. 2011;25:990–1001. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-163261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ackermann MA, Ziman AP, Strong J, Zhang Y, Hartford AK, Ward CW, et al. Integrity of the network sarcoplasmic reticulum in skeletal muscle requires small ankyrin 1. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:3619–30. doi: 10.1242/jcs.085159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Accornero F, van Berlo JH, Benard MJ, Lorenz JN, Carmeliet P, Molkentin JD. Placental growth factor regulates cardiac adaptation and hypertrophy through a paracrine mechanism. Circulation research. 2011;109:272–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.240820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim H, Zhu YZ. Role of transforming growth factor-beta in the progression of heart failure. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2584–96. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6085-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barbas JA, Chaix JC, Steinmetz M, Goridis C. Differential splicing and alternative polyadenylation generates distinct NCAM transcripts and proteins in the mouse. EMBO J. 1988;7:625–32. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02856.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gattenlohner S, Waller C, Ertl G, Bultmann BD, Muller-Hermelink HK, Marx A. NCAM(CD56) and RUNX1(AML1) are up-regulated in human ischemic cardiomyopathy and a rat model of chronic cardiac ischemia. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1081–90. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63467-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagao K, Sowa N, Inoue K, Tokunaga M, Fukuchi K, Uchiyama K, et al. Myocardial expression level of neural cell adhesion molecule correlates with reduced left ventricular function in human cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:351–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacLellan WR, Brand T, Schneider MD. Transforming growth factor-beta in cardiac ontogeny and adaptation. Circ Res. 1993;73:783–91. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.5.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verstraeten A, Alaerts M, Van Laer L, Loeys B. Marfan Syndrome and Related Disorders: 25 Years of Gene Discovery. Hum Mutat. 2016;37:524–31. doi: 10.1002/humu.22977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swaggart KA, McNally EM. Modifiers of heart and muscle function: where genetics meets physiology. Exp Physiol. 2014;99:621–6. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.075887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verheule S, Sato T, Everett Tt, Engle SK, Otten D, Rubart-von der Lohe M, et al. Increased vulnerability to atrial fibrillation in transgenic mice with selective atrial fibrosis caused by overexpression of TGF-beta1. Circ Res. 2004;94:1458–65. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000129579.59664.9d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi EK, Chang PC, Lee YS, Lin SF, Zhu W, Maruyama M, et al. Triggered firing and atrial fibrillation in transgenic mice with selective atrial fibrosis induced by overexpression of TGF-beta1. Circ J. 2012;76:1354–62. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-11-1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Derangeon M, Montnach J, Ore Cerpa C, Jagu B, Patin J, Toumaniantz G, et al. TGF-beta receptor inhibition prevents ventricular fibrosis in a mouse model of progressive cardiac conduction disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2017 doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx026. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Arnett DK, Meyers KJ, Devereux RB, Tiwari HK, Gu CC, Vaughan LK, et al. Genetic variation in NCAM1 contributes to left ventricular wall thickness in hypertensive families. Circ Res. 2011;108:279–83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.239210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tur MK, Etschmann B, Benz A, Leich E, Waller C, Schuh K, et al. The 140-kD isoform of CD56 (NCAM1) directs the molecular pathogenesis of ischemic cardiomyopathy. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:1205–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roubin R, Deagostini-Bazin H, Hirsch MR, Goridis C. Modulation of NCAM expression by transforming growth factor-beta, serum, and autocrine factors. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:673–84. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.2.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schafer H, Struck B, Feldmann EM, Bergmann F, Grage-Griebenow E, Geismann C, et al. TGF-beta1-dependent L1CAM expression has an essential role in macrophage-induced apoptosis resistance and cell migration of human intestinal epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2013;32:180–9. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geismann C, Morscheck M, Koch D, Bergmann F, Ungefroren H, Arlt A, et al. Up-regulation of L1CAM in pancreatic duct cells is transforming growth factor beta1- and slug-dependent: role in malignant transformation of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4517–26. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perides G, Safran RM, Downing LA, Charness ME. Regulation of neural cell adhesion molecule and L1 by the transforming growth factor-beta superfamily. Selective effects of the bone morphogenetic proteins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:765–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.