Abstract

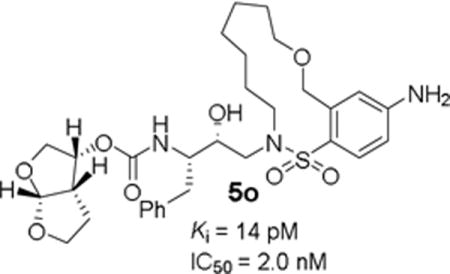

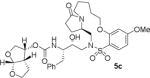

Design, synthesis, and evaluation of a new class of HIV-1 protease inhibitors containing diverse flexible macrocyclic P1′–P2′ tethers are reported. Inhibitor 5a with a pyrrolidinone-derived macrocycle exhibited favorable enzyme inhibitory and antiviral activity (Ki = 13.2 nM, IC50 = 22 nM). Further incorporation of heteroatoms in the macrocyclic skeleton provided macrocyclic inhibitors 5m and 5o. These compounds showed excellent HIV-1 protease inhibitory (Ki = 62 pM and 14 pM, respectively) and antiviral activity (IC50 = 5.3 nM and 2.0 nM, respectively). Inhibitor 5o also remained highly potent against a DRV-resistant HIV-1 variant.

Keywords: HIV protease, Drug resistance, P1′ P2′ ligands, Macrocyclic inhibitors, Structure-based design

Graphical abstract

The introduction of combined active antiretroviral treatment (cART) in late nineteen-nineties marked the beginning of a breakthrough treatment for patients with HIV infection and AIDS.1,2 cART treatment regimens with protease inhibitors and reverse transcriptase inhibitors dramatically improved HIV-related disease progression and mortality.3,4 The cART is not a cure, however, it has significantly improved quality of life and transformed the HIV/AIDS pandemic to a manageable chronic ailment with normal life expectancy.5,6 The impact of cART is remarkable, however, current cART suffers from a number of major drawbacks. The most concerning is the rapid emergence of drug-resistant HIV-1 variants making cART ineffective for some HIV/AIDS patient groups.7–,9 Current patients who achieve initial viral suppression may ultimately experience treatment failure.10,11 Furthermore, it has been suggested that these drug-resistant variants can be transmitted to new individuals. The ability to provide long-term cART benefits remains a complex issue. HIV protease inhibitors (PIs) are critical components of cART regimens particularly for salvage treatments. Therefore, design and development of new, more potent, safer therapeutics with high genetic barrier against HIVs acquisition of drug resistance are very important.

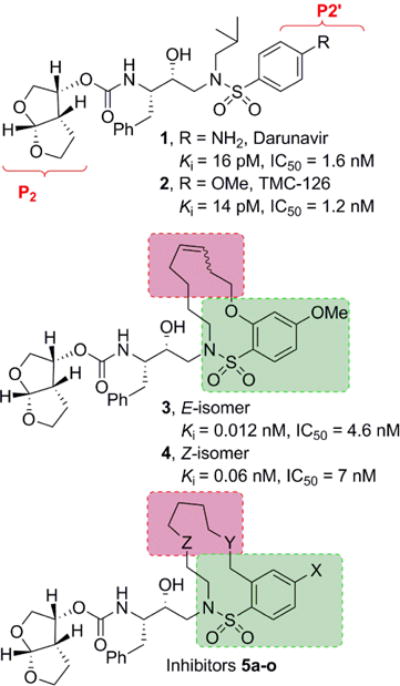

Our laboratories have been involved in the design and synthesis of nonpeptide PIs that are active against HIV-1 variants resistant to the currently approved PIs.12–14 One of the PIs is darunavir (DRV, 1), an FDA approved first-line therapeutic agent for the treatment of HIV/AIDS patients.15,16 DRV contains a structure-based designed privileged template, (3R,3aS,6aR-bis-tetrahydrofuranyl urethane (bis-THF) as the P2 ligand imbedded in a hydroxyl ethylamine sulfonamide isostere (1, Figure 1).14,17 DRV showed a high genetic barrier, to acquire drug-resistance associated mutations.18–20 One of our key design strategies is to promote the extensive network of hydrogen bonding interactions with the active site backbone atoms of HIV-1 protease.13,17 Based upon these strategies, we developed a range of PIs with broad-spectrum activity against multidrug-resistant HIV-1 variants.2,17

Figure 1.

Structure of inhibitors 1–4 and general structures of macrocyclic inhibitors 5a–o.

In an alternative approach to develop PIs with broad-spectrum activity, we have designed a number of macrocyclic PIs with exceptional antiviral activity and drug-resistance profiles.21–24 Among them, we have reported macrocyclic inhibitors typified by 13-membered unsaturated derivatives 3 and 4, modifying P1′–P2′-ligands of darunavir-like PIs (Figure 1). Both geometrical isomers displayed excellent inhibitory potency as well as antiviral activity. The corresponding saturated derivatives are significantly less potent. The rationale underlying the design of these inhibitors is based on crystallographic data and modeling studies indicating decreased van der Waals interactions and inhibitor side-chain repacking across representative mutant strains in the vicinity of the S1’ subsite area.25,26 In this context, the introduction of specific heterocyclic scaffolds or heteroatoms on the P1′–P2′ tether of the macrocycle could allow effective inhibitor adaptation to a range of side chain mutations. With the aim of developing novel broad-spectrum HIV-1 PIs we explored the combination of a flexible macrocyclic P1′–P2′ tether with the pyrrolidinone ring as the potential source for additional backbone interactions. Furthermore, we sought to investigate the outcome of a small set of flexible macrocycles incorporating suitably functionalized nitrogen and oxygen heteroatoms to interact with the backbone residues. Herein, we report design, synthesis and biological results of a series of potent macrocyclic HIV-1 protease inhibitors.

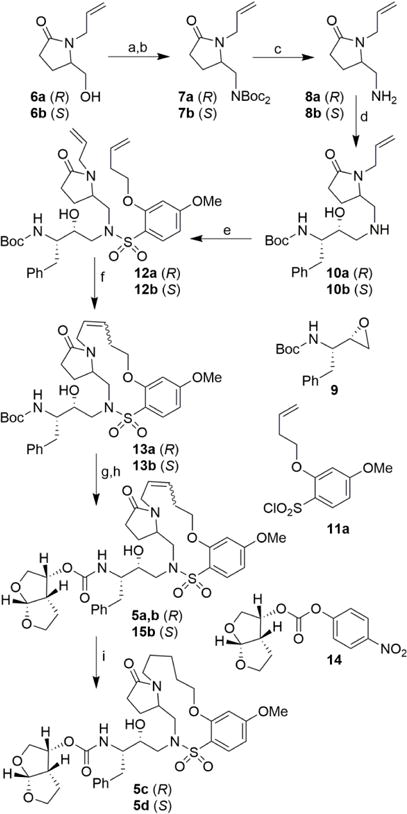

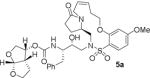

Based upon our previous studies, our current design plan was to further explore 13- and 14-membered macrocycles.21 Early approaches of the work focused on the incorporation of 2-pyrrolidinone heterocycles with (S)- and (R)-configuration to promote hydrogen bonding interaction with Gly27 backbone amide NH.27 Furthermore, we planned to incorporate N-methyl sulfonamide and alkyl ether functionalities to promote interactions with backbone atoms in the active site. The synthesis of the pyrrolidinone-containing macrocyclic inhibitors are described in Scheme 1. Commercially available allylpyrrolidinone 6a was converted to the corresponding tosylate derivative by treatment with tosyl chloride and triethylamine in the presence of a catalytic amount of DMAP in CH2Cl2 at 23 °C. The resulting tosylate was reacted with NaH and di-tert-butyl iminodicarboxylate in DMF at 0 °C. The resulting mixture was then heated at 65 °C for 12 h to provide Boc-derivative 7a in excellent yield. Exposure of 7a to trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) at 23 °C provided the amine 8a in 82% yield. Reaction of amine 8a with commercially available optically active oxirane 9 in isopropanol at 60 °C for 24 h provided Boc-aminoalcohol derivative 10a in good yield. Amine 10a was reacted with the known21 sulfonyl chloride 11a in CH2Cl2 in the presence of aqueous NaHCO3 solution at 23 °C to provide diene derivative 12a. Exposure of diene 12a to ring closing metathesis (RCM) using Grubb’s second-generation catalyst (Grubbs II) (5 mol%) in CH2Cl2 at 23 °C for 14 h afforded macrocyclic derivative 13a as a E/Z mixture nearly 60:40 by HPLC analysis. Removal of the Boc group by treatment with TFA provided the corresponding amine. The reaction of the resulting amine with activated carbonate derivative 14 afforded a mixture of unsaturated derivatives. These E/Z isomers were separated by HPLC using a reverse phase C18 column to provide the pure E- and Z-isomers 5a and 5b, respectively. Catalytic hydrogenation of E/Z mixture in the presence of 10% Pd-C in ethyl acetate under a hydrogen-filled balloon afforded the saturated inhibitor 5c in good yield. The corresponding saturated derivative 5d containing (S)-pyrrolidinone was synthesized following the same sequence of reactions using (S)-allylpyrrolidinone 6b as the starting material.

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) p-TsCl, DMAP, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 16 h, (R) 63%, (S) 74%; (b) NHBoc2, NaH, dry DMF, 0 °C to 65 °C, 12 h, (R) 90%, (S) 93%; (c) TFA, CH2Cl2, 23 °C, 13 h, (R) 82%, (S) 75%; (d) 9, iPrOH, 60 °C, 24 h, (R) 56%, (S) 57%; (e) 11a, aqueous NaHCO3, CH2Cl2, 23 ° C, 14 h, (R) 55%, (S) 80%; (f) Grubbs II, dry CH2Cl2, 23 °C, 12 h, (R) 64% (E/Z mixture 57:43 by HPLC), (S) 53%,(E/Z mixture); (g) TFA, CH2Cl2, 23 °C, 8 h; (h) 14, N,N-DIPEA, MeCN, 23 °C, 5 days, (R) 64%, (S) 92%, (E/Z mixture); (i) H2, 10 % Pd/C, EtOAc, 23 °C, 12 h, (R) 73%, (S) 89%.

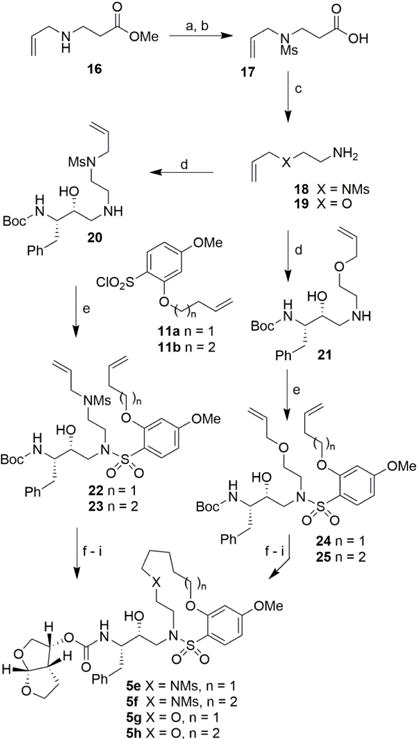

The synthesis of heteroatom-containing macrocyclic inhibitors is described in Scheme 2. Commercially available methyl allylaminopropionate 16 was reacted with MsCl in CH2Cl2 in the presence of aqueous NaHCO3 at 23 °C to provide the corresponding mesylate derivative. Saponification of the methyl ester with LiOH in aqueous THF at 23 °C furnished carboxylic acid 17. Curtius rearrangement of acid 17 with diphenylphosphoryl azide (DPPA) in the presence of triethylamine in toluene afforded amine 18 in good yield. For incorporation of ether functionality within the macrocycle, we utilized commercially available allyloxyethylamine 19. Both amines 18 and 19 were reacted with commercially available optically active oxirane 9 in isopropanol at 56 °C for 14 h to provide Boc-aminoalcohol derivatives 20 and 21, respectively. Amine 20 was then reacted with known21 sulfonyl chlorides 11a and 11b in CH2Cl2 in the presence of aqueous NaHCO3 solution at 23 °C to afford diene sulfonamide derivatives 22 and 23, respectively. Similarly, reaction of amine 21 with sulfonyl chlorides 11a and 11b furnished diene sulfonamide derivatives 24 and 25 in excellent yields. Dienes 22–25 were converted macrocyclic inhibitors 5e–h as follows. The acyclic dienes 22–25 were exposed to RCM using Grubbs’ 2nd generation catalyst16 to give the corresponding unsaturated macrocyclic derivatives. The Boc-group was deprotected using TFA and the resulting amines were reacted with the mixed carbonate of activated bis-THF derivative 14 providing the corresponding unsaturated macrocyclic derivatives. The resulting unsaturated compounds were hydrogenated over 10% Pd-C as catalyst to yield inhibitors 5e–h.

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions: (a) MsCl, aq. NaHCO3, CH2Cl2, 23 °C, 16 h, 86%; (d) LiOH.H2O, aq. THF, 23 °C, 18 h, 95%; (c) DPPA, Et3N, toluene, 23 °C to reflux, 5 h then aq. NaOH, 98 °C 12 h, 67%; (d) 9, i-PrOH, 56 °C, 14 h, 56-63%; (e) 11a or 11b, aq. NaHCO3, CH2Cl2, 23 °C, 14 h, 90– 98%; (f) Grubbs II, dry CH2Cl2, 40 °C, 3–6 h, 52–92% (E/Z mixture); (g) TFA, CH2Cl2, 23 °C, 48 h; (h) 14, DIPEA, MeCN, 23 °C, 3–7 days, 23–60%; (i) H2, 10 % Pd/C, EtOAc, 23 °C, 12 h, 75–90%.

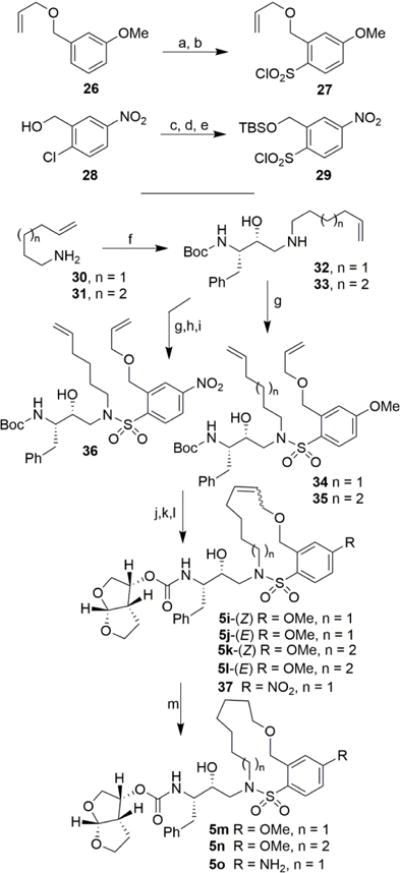

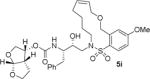

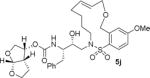

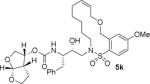

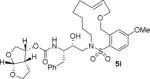

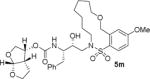

Based upon X-ray structure of our previous macrocyclic inhibitor-bound HIV-1 protease, we sought to investigate macrocycles with isomeric benzyl ether oxygen which would be within proximity to form hydrogen bonds with backbone atoms in the S2′-site. These benzyl ether derivatives may exhibit better stability than the phenyl ether derivatives. The synthesis of these benzyl ether-derived macrocyclic inhibitors is described in Scheme 3. Preparation of sulfonyl chloride 27 was carried out from commercially available 3-allyloxymethylanisole 26 as described by Blotny and co-workers28 by treatment with chlorosulfuric acid at 0 °C followed by reaction of the resulting sulfonic acid with cyanuric chloride in dry acetone in the presence of triethylamine to provide sulfonyl chloride 27 in 37% yield. For the synthesis of benzyl ether derivative with 4-amino substitution, the corresponding sulfonyl chloride derivative 29 was prepared from commercially available 2-chloro-5-nitrobenzyl alcohol 28. Reaction of alcohol with NaH in the presence of TBSCl in dry THF provided the TBS ether. This was converted to the corresponding thiophenol derivative by reaction with sodium disulfide, freshly prepared from sodium sulfide and elemental sulfur in ethanolic solution in the presence of NaOH to provide a mixture of the corresponding thiol along with its oxidized disulfide derivative.29 Oxidation of this mixture by a combination of N-chlorosuccinimide and dilute hydrochloric acid in MeCN afforded the corresponding sulfonyl chloride 29 in moderate yield.30 Commercially available 5-hexenylamine and 6-heptenylamine 30 and 31 were reacted with chiral epoxide 9 providing epoxide opening products 32 and 33, respectively in excellent yield. Reaction of these amines with sulfonyl chloride derivative 27 afforded the corresponding diene sulfonamide derivatives 34 and 35. For the synthesis of diene 36, sulfonamide intermediate derived from sulfonyl chloride 29 was subjected to n-Bu4N+F− in THF. The resulting alcohol was subjected to O-allylation with allyl-tert-butylcarbonate in the presence of catalytic Pd(PPh3)4 to provide 36. For the synthesis of the unsaturated inhibitors with p-OMe sulfonamides 5i–l, diene derivatives 34 and 35 were exposed to RCM to provide the corresponding unsaturated macrocycles with E/Z mixtures (approximately 1:2 E/Z ratio). Deprotection of Boc-group with TFA followed by reaction of the resulting amines with activated bis-THF derivative 14 furnished unsaturated inhibitors as a mixture of E/Z isomers. The mixture of isomers were separated by HPLC using a C18 column to furnish macrocyclic inhibitors 5i–5l (34-60% yield). Diene sulfonamide with a p-NO2 group was converted to macrocyclic inhibitors 37 by similar sequence of reactions. Catalytic hydrogenation of unsaturated macrocycles over 10% Pd-C provided saturated inhibitors 5m and 5n. For the synthesis of the terminal p-NH2-derived inhibitor 5o, unsaturated macrocycle 37 was exposed to SnCl2-mediated reduction in EtOH to afford the corresponding aniline derivative in 82% yield. Hydrogenation of the resulting olefin mixture over 10% Pd-C furnished saturated macrocyclic inhibitor 5o.

Scheme 3.

Reagents and conditions: (a) HSO3Cl, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 20 min; (b) cyanuric chloride, Et3N, dry acetone, 23 °C to 60 °C, 24 h, 37% over 2 steps; (c) TBSCl, NaH (60% susp. in mineral oil), TBAI, dry THF, 0 °C, 1 h, 90%; (d) Na2S2 in EtOH, NaOH, EtOH, reflux, 2 h; (e) NCS, 2M HCl in MeCN, − 10 °C to 20 °C, 30 min, 35% over 2 steps; (f) 9, iPrOH, 56 °C, 14 h, 82% for n = 1, 63% for n = 2; (g) 27 or 29, aqueous NaHCO3, CH2Cl2, 23 °C, 18 h, 85–92%; (h) TBAF, dry THF, 0 °C, 15 min, 78%; (o) allyl-tert-butylcarbonate, Pd(PPh3)4, dry THF, 60 °C, 3 h; (j) Grubbs II, dry CH2Cl2, 40 °C, 3–6 h, 85–93%; (k) TFA, CH2Cl2, 23 °C, 3 h; (l) 14, DIPEA, MeCN, 23 °C, 8 days, 34–60%; (m) H2, 10% Pd/C, EtOAc, 23 °C, 12 h, 87–90%.

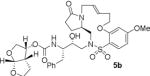

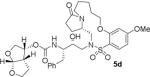

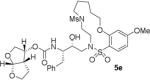

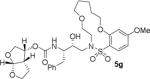

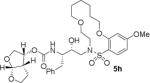

HIV-1 protease inhibitory potency of all synthesized inhibitors was evaluated using the assay protocol reported by Toth and Marshall.31 These results are shown in Tables 1 and 2. A selected number of compounds was further evaluated in antiviral assay following a previously published assay protocol using MT-2 cells exposed to HIV-1LAI.32 We first investigated a set of macrocyclic inhibitors containing both E- and Z-olefins along with R-pyrrolidinone on the macrocyclic tether to form backbone hydrogen bonding with Gly27 in the S1’-subsite. We specifically investigated (R)-pyrrolidinone in inhibitors 5a to 5c (entries 1–3, Table 1) as this stereochemistry showed enhanced potency over the (S)-isomer in acyclic inhibitors. As can be seen, inhibitor 5b with an E-isomer is significantly potent in enzyme inhibitory assay. However, inhibitor 5a with Z-isomer showed better antiviral activity. Saturated inhibitor 5c displayed good enzyme activity however its antiviral activity was not improved over inhibitor 5a. We have also prepared inhibitor 5d incorporating a (S)-pyrrolidinone derivative. It showed significant reduction of enzyme Ki as well as antiviral activity. We previously observed that macrocyclic inhibitors with 13- and 14- membered rings are nicely accommodated by the S1–S2′ subsites. In an effort to promote hydrogen bonding interactions in this region, we incorporated N-methylsulfonamide functionality. The corresponding 13- and 14-membered macrocyclic inhibitors 5e and 5f (entries 5 and 6, Table 1) showed reduced enzyme inhibitory activity compared to the corresponding inhibitors with carbon chains. The corresponding oxocyclic inhibitors 5g and 5h (entries 7 and 8, Table 1) showed improved enzyme inhibitory activity, however, inhibitor 5h did not show appreciable antiviral activity (IC50 > 1 μM).

Table 1.

Structures and activity of inhibitors 5a–h

| Entry | Inhibitor structure | Ki | IC50a,b |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| (nM) | |||

| 1. |

|

13.2 | 22 |

| 2. |

|

0.47 | 176 |

| 3. |

|

0.46 | 122 |

| 4. |

|

27.0 | >1000 |

| 5. |

|

33.3 | nt |

| 6. |

|

13.3 | nt |

| 7. |

|

4.21 | nt |

| 8. |

|

9.85 | >1000 |

Darunavir (1) exhibited Ki = 16 pM, antiviral IC50 = 3 nM;

nt = not tested.

Table 2.

Structures and activity of inhibitors 5i–o

| Entry | Inhibitor structure | Ki | IC50a,b |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| (nM) | |||

| 1. |

|

0.029 | 54 |

| 2. |

|

0.015 | 46 |

| 3. |

|

0.64 | nt |

| 4. |

|

0.55 | nt |

| 5. |

|

0.062 | 5.3 |

| 6. |

|

0.062 | 31 |

| 7. |

|

0.014 | 2.0 |

Darunavir (1) exhibited Ki = 16 pM, antiviral IC50 = 3 nM;

nt = not tested.

The X-ray crystal structure of the inhibitor 3-bound HIV-1 protease revealed that the phenolic oxygen on the macrocycle do not form any hydrogen bonds in the S1′-subsite. Based upon this X-ray structure, we envisioned that the corresponding positional isomer, particularly incorporation of oxygen at the benzylic position may lead to improved potency as this oxygen would be within proximity to interact with backbone atoms in the S2′-subsite. Inhibitors 5i and 5j incorporated the benzyl ether oxygen within the 13-membered ring cycle with both Z- and E-olefin (entries 1 and 2, Table 2). Both inhibitors showed excellent enzyme inhibitory activity. However, the antiviral activity of both compounds was significantly reduced compared to the corresponding phenolic ether derivatives 3 and 4. In contrast, the 14-membered macrocyclic inhibitors with E- and Z-derivatives (compounds 5k and 5l, entries 3 and 4, Table 2) showed greater than 20-fold reduction of enzyme inhibitory activity over inhibitors 5i and 5j. Interestingly, both 13- and 14-membered saturated macrocyclic inhibitors 5m and 5n showed much improved enzyme inhibitory activity. Also, inhibitor 5m with 13-membered macrocyclic e exhibited antiviral IC50 of 5.3 nM.

Inhibitor 5o with a para-aminosulfonamide derivative showed excellent enzyme inhibitory potency as well as antiviral activity (entry 7, Table 2).

We selected inhibitors 5m and 5o for further evaluation against a DRV-resistant HIV-1 variants. These DRV-resistant HIV-1DRVR variants are highly resistant to all current clinically used PIs including DRV and nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors such as tenofovir. In these assay, MT-4 cells (1 × 104) were exposed to wild-type HIV-1 and a DRV-resistant variant (HIV-1DRVRP20) and subjected to various concentrations of each PI. IC50 values were determined using p24 assay.32,33 The results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Antiviral activity of inhibitors 5m and 5o against HIV-1DRVRP20 resistant HIV-1 variant.

| Cpd | mean IC50 in nM (fold-change)a

|

|

|---|---|---|

| HIV-1NL4 3 | HIV-1DRVRP20 | |

| 5m | 3.6 | 240 (67) |

| 5o | 1.5 | 20 (13) |

| DRV (1) | 1.8 | 87 (48) |

MT-4 cells (1 × 104) were exposed to 50 TCID50 of wild-type HIV-1NL4 3 or HIV-1DRVRP20, and cultured in the presence of various concentrations of each PI, and the IC50 values were determined using the p24 assay. The amino acid substitutions identified in protease of HIV-1DRVRP20, compared to HIV-1NL4 3 include L10I/I15V/K20R/L24I/V32I/M36I/M46L/L63P/V82A/L89M. All assays were conducted in triplicate, and the data shown represent mean values derived from the results of three independent experiments.

Inhibitor 5o potently blocked the replication of wild-type HIV-1NL4 3 showing improved antiviral activity compared to inhibitor 5m and DRV. Furthermore, this inhibitor suppressed the replication of HIV-1 DRVRP20-resistent variant. As can be seen, the fold-difference in the IC50 values of 5o against HIV-1DRVRP20 compared to wild-type HIV-1NL4 3 was 13-fold, while the fold-differences for DRV (1) and inhibitor 5m were 48- and 67-fold, respectively.

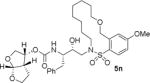

To gain molecular insight into the binding properties of macrocyclic inhibitors containing benzyl ether functionality on the macrocycle, we determined the X-ray crystal structure of inhibitor 5j and wild-type HIV-1 protease complex. The structure was refined at 1.27 Å resolution to give R-value of 15.9%. The X-ray structure contains a protease dimer and inhibitor 5j in two orientations related by a 180° rotation with relative occupancies of 65/35%. A stereoview of the active site interactions is shown in Figure 2. The X-ray showed similarity to the structure of darunavir-bound HIV-1 protease complex33 with root mean square difference of 0.16Å for Cα atoms. Larger differences between the corresponding Cα atoms are less than 0.5Å. Inhibitor 5j shares identical P1 and P2 ligands like darunavir. However, the major difference is in the P1′–P2′ regions where a 13-membered macrocycle linking P1′ and P2′ ligands have been incorporated. Interestingly, this macrocycle differs from previously reported macrocyclic ligands with respect to a specific oxymethyl functionality on the macrocycle.21 Most of the interaction of the bis-THF P2 ligand, phenylmethyl P1-ligand as well as the transition state hydroxyl group are comparable to those of the HIV-1 protease-darunavir complex.34 The flexible P1′–P2′ macrocyclic ring, containing an E-olefin, nicely packs between the S1′–S2′ subsites in a zigzag crown-like shape. The protease-inhibitor complex reveals interesting new water-mediated hydrogen bonding interactions of the oxymethyl oxygen with backbone atoms at the S2′-site. The ring oxygen makes water-mediated hydrogen bonds with backbone NH of Asp29′ as well as with the carboxyl oxygen of Gly27′, with distances ranging from 2.9–3.4 Å. The new backbone binding with the main chain atoms may be responsible for its ability to maintain high potency against multidrug-resistant HIV-1 variants.12,17 Inhibitor maintains the water-mediated hydrogen bonding interactions with Ile50 and Ile50′ amide NHs that are conserved in the majority of inhibitor-protease complexes.35,36 Furthermore, inhibitor 5j makes weaker C–H…O interactions throughout the active site of HIV-1 protease.37,38

Figure 2.

Stereoview of the X-ray structure of inhibitor 5j (turquoise)-bound HIV-1 protease (PDB code: 5WLO). All strong active site hydrogen bonding interactions of inhibitor 5j with HIV-1 protease are shown as dotted lines.

In summary, we have designed novel HIV-1 protease inhibitors containing diverse flexible macrocyclic P1′–P2′ tethers for the HIV-1 protease active site and investigated their biological activity. We based our rational design upon the premise that P1′–P2′ tethers in the contrast of a flexible macrocycle enable effective inhibitor adaptation across a range of side chain mutations. With the aim of developing broad-spectrum inhibitors we also planned to establish additional contacts with key backbone residues. Accordingly, a series of pyrrolidinone-fused macrocyclic inhibitors have been designed and synthesized, leading to the identification of inhibitor 5a endowed with a favorable enzyme inhibitory profile and relevant antiviral activity. We subsequently performed a systematic study involving the strategic placement of oxygen (and nitrogen) heteroatoms along the macrocycle skeleton which led to identification of derivative 5m and its aniline analogue 5o as potent inhibitors of HIV-1 protease in the picomolar range. Of particular importance, inhibitor 5o remained highly potent against a DRV-resistant HIV-1 variant. The flexible P1′–P2′ macrocyclic nicely packs between the S1′–S2′ subsites in a zigzag crown-like shape. To obtain molecular insight into the ligand-binding site interactions, we determined X-ray crystal structure of inhibitor 5j-bound HIV-1 protease. The structure shows interesting new water-mediated hydrogen bonding interactions of the macrocyclic ring oxygen with backbone atoms at the S2′-site. This may be responsible for inhibitor’s high affinity. Further design and improvement of inhibitor properties are currently in progress in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant GM53386, AKG and Grant GM62920, ITW). The X-ray data was collected at the Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team (SER-CAT) beamline 22ID at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. This work was also supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Priority Areas) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (Monbu Kagakusho), a Grant for Promotion of AIDS Research from the Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Labor of Japan, and the Grant to the Cooperative Research Project on Clinical and Epidemiological Studies of Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases (Renkei Jigyo) of Monbu-Kagakusho. The authors would like to thank the Purdue University Center for Cancer Research, which supports the shared NMR and mass spectrometry facilities.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version.

References and notes

- 1.Edmonds A, Yotebieng M, Lusiama J, Matumona Y, Kitetele F, Napravnik S, Cole SR, Van Rie A, Behets F. PLoS Med. 2011:8e1001044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghosh AK, Osswald HL, Prato G. J Med Chem. 2016;59:5172–5208. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitsuya H, Maeda K, Das D, Ghosh AK. Adv Pharmacol. 2008;56:169–197. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(07)56006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hue S, Gifford RJ, Dunn D, Fernhill E, Pillay D. J Virol. 2009;83:2645–2654. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01556-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diffenbach CW, Fauci AS. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:766–771. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-11-201106070-00345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel K, Hernán MA, Williams PL, Seeger JD, McIntosh K, Van Dyke RB, Seage GR., III Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:507–515. doi: 10.1086/526524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta R, Hill A, Sawyer AW, Pillay D. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:712–722. doi: 10.1086/590943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cihlar T, Fordyce M. Curr Opin Virol. 2016;18:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pennigs PS. Infect Dis Rep. 2013;5:21–25. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conway B. Future Virol. 2009;4:39–41. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghosh AK, Chapsal B, Mitsuya H. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim. 2010:205–243. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghosh AK, Chapsal BD, Weber IT, Mitsuya H. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:78–86. doi: 10.1021/ar7001232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh AK, Sridhar PR, Kumaragurubaran N, Koh Y, Weber IT, Mitsuya H. ChemMedChem. 2006;1:939–950. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200600103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghosh AK, Chapsal BD. Design of the anti-HIV protease inhibitor darunavir. In: Ganellin CR, Roberts SM, Jefferis R, editors. From Introduction to Biological and Small Molecule Drug Research and Development. 2013. pp. 355–384. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghosh AK, Dawson ZL, Mitsuya H. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:756–7580. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghosh AK, Anderson DD, Weber IT, Mitsuya H. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:1778–1802. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koh Y, Nakata H, Maeda K, Ogata H, Bilcer G, Devasamudram T, Kincaid JF, Boross P, Wang Y-F, Tie Y, Volarath P, Gaddis L, Harrison RW, Weber IT, Ghosh AK, Mitsuya H. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3123–3129. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.10.3123-3129.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Béthune MP, Sekar V, Spinosa-Guzman S, Vanstockem M, De Meyer S, Wigerinck P, Lefebvre E. “Darunavir (Prezista, TMC114): From bench to clinic, improving treatment options for HIV-infected patients” Antiviral drugs: From basic discovery through clinical trials. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2011. pp. 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Meyer S, Azijn H, Surleraux D, Jochmans D, Tahri A, Pauwels R, Wigerinck P, de Béthune MP. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2314–2321. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.6.2314-2321.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghosh AK, Kulkarni S, Anderson DD, Hong L, Baldridge A, Wang YF, Chumanevich AA, Kovalevsky AY, Tojo Y, Amano M, Koh Y, Tang J, Weber IT, Mitsuya H. J Med Chem. 2009;52:7689–7705. doi: 10.1021/jm900695w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghosh AK, Swanson L, Liu C, Cho H, Hussain A, Walters DE, Holland L. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2002;12:1993–1996. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00300-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghosh AK, Swanson LM, Cho H, Leshchenko S, Hussain KA, Kay S, Walters DE, Koh Y, Mitsuya H. J Med Chem. 2005;48:3576–3585. doi: 10.1021/jm050019i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghosh AK, Schiltz GE, Rusere LN, Osswald HL, Walters DE, Amano M, Mitsuya H. Org Biomol Chem. 2014;12:6842–6854. doi: 10.1039/c4ob00738g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erickson J, Neidhart DJ, Van Drie J, Kempf DJ, Wang XC, Norbeck DW, Plattner JJ, Rittenhouse JW, Turon M, Wideburg N, Kohlbrenner WE, Simmer R, Helfrich R, Paul DA, Knigge M. Science. 1990;249:527–533. doi: 10.1126/science.2200122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baldwin ET, Bhat TN, Liu B, Pattabriaman N, Erickson JW. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:244–249. doi: 10.1038/nsb0395-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghosh AK, Leshchenko-Yashchuk S, Anderson DD, Baldridge A, Noetzel M, Miller HB, Tie Y, Wang Y-F, Koh Y, Weber IT, Mitsuya H. J Med Chem. 2009;52:3902–3914. doi: 10.1021/jm900303m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blotny G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:1499–1501. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Price CC, Stacy GW. J Am Chem Soc. 1946;68:498–500. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishiguchi A, Maeda K, Miki S. Synthesis. 2006;24:4131–4134. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toth MV, Marshall GR. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1990;36:544–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1990.tb00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koh Y, Amano M, Towata T, Danish M, Leshchenko-Yashchuk S, Das D, Nakayama M, Tojo Y, Ghosh AK, Mitsuya H. J Virol. 2010;84:11961–11969. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00967-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koh Y, Das D, Leschenko S, Nakata H, Ogata-Aoki H, Amano M, Nakayama M, Ghosh AK, Mitsuya H. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:997–1006. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00689-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kovalevsky AY, Tie Y, Liu F, Boross PI, Wang YF, Leshchenko S, Ghosh AK, Harrison RW, Weber IT. J Med Chem. 2006;49:1379–1387. doi: 10.1021/jm050943c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gustchina A, Sansom C, Prevost M, Richelle J, Wodak S, Wlodawer A, Weber I. Protein Eng. 1994;7:309–317. doi: 10.1093/protein/7.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tie Y, Boross PI, Wang YF, Gaddis L, Liu F, Chen X, Tozser J, Harrison RW, Weber IT. FEBS J. 2005;272:5265–5277. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Panigrahi T, Desiraju G. Proteins. 2007;67:128–141. doi: 10.1002/prot.21253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.PDB code: 5WLO. For details of X-ray studies, please see supplementary information.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.