Abstract

Barley (1–3)β-D-Glucan (BBG) enhances angiogenesis. Since pasta is very effective in providing a BBG-enriched diet, we hypothesized that the intake of pasta containing 3% BBG (P-BBG) induces neovascularization-mediated cardioprotection. Healthy adult male C57BL/6 mice fed P-BBG (n = 15) or wheat pasta (Control, n = 15) for five-weeks showed normal glucose tolerance and cardiac function. With a food intake similar to the Control, P-BBG mice showed a 109% survival rate (P < 0.01 vs. Control) after cardiac ischemia (30 min)/reperfusion (60 min) injury. Left ventricular (LV) anion superoxide production and infarct size in P-BBG mice were reduced by 62 and 35% (P < 0.0001 vs. Control), respectively. The capillary and arteriolar density of P-BBG hearts were respectively increased by 12 and 18% (P < 0.05 vs. Control). Compared to the Control group, the VEGF expression in P-BBG hearts was increased by 87.7% (P < 0.05); while, the p53 and Parkin expression was significantly increased by 125% and cleaved caspase-3 levels were reduced by 33% in P-BBG mice. In vitro, BBG was required to induce VEGF, p53 and Parkin expression in human umbelical vascular endothelial cells. Moreover, the BBG-induced Parkin expression was not affected by pifithrin-α (10 uM/7days), a p53 inhibitor. In conclusion, long-term dietary supplementation with P-BBG confers post-ischemic cardioprotection through endothelial upregulation of VEGF and Parkin.

Introduction

Early primary coronary revascularization significantly restores the blood supply to the ischemic myocardium and limits the loss of cardiac cells1, yet its clinical efficacy varies widely among patients2 and with increasing age3. An individual’s tolerance to the post-ischemic reperfusion insult of the heart depends on the variation in density of the native coronary collaterals4,5. These collaterals lead to retrograde perfusion of the obstructed coronary tree by limiting the magnitude of the myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury in animal models6 and also in humans7. The rarefaction of the native coronary collaterals limits the efficacy of coronary reperfusion8 and may worsen the outcome of ischemic patients who are not eligible for reperfusion therapy5,9.

De novo formation of coronary collaterals thus has the potential to prevent myocardial injury at early stages of post-ischemic reperfusion10. The formation of collateral vessels is attributable to the production of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)11, which plays a key role in improving angiogenic sprout formation12 and endothelial cell/cardiomyocyte cross-talk13. In addition, autocrine endothelial VEGF is essential for normal metabolic functions and endothelial cell preservation14. Importantly, the regulation of endothelium-cardiomyocyte cross-talk may prevent the post-ischemic decay of cardiomyocyte contractility15, even in a VEGF- dependent manner16. In fact, the paracrine actions of VEGF promptly affect the function of adjacent cardiac cells with a high potential for myocardial repair17.

Effective de novo formation of coronary collaterals is dependent on endothelial cell integrity, which is maintained by Parkin, an E3-ligase that combines target proteins with ubiquitin, leading to their proteasomal degradation, and protects mitochondrial function18. Parkin deficiency abolishes the ischemic preconditioning-induced cardioprotection19 and it reduces cardiac tolerance to hypoxia20. Although gene therapy increases the myocardial expression of VEGF21 or Parkin20 by protecting the heart from ischemic insult, non-invasive approaches to upregulating these proteins remain a desirable goal. Recently, we demonstrated that long-term exposure of human endothelial cells to 3% BBG increases manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) expression and nitric oxide (NO) production, which promote the formation of new vessels22. Although a previous in vitro study revealed that VEGF induces endothelial MnSOD expression23, it is still unknown whether sustained dietary intake of BBG promotes cardioprotection in vivo through endothelial upregulation of VEGF and Parkin.

Short-term oral intake of a higher dose of β-1.3/1.6-Glucan isolated from Saccharomyces cerevisae prevents cardiac injury in pigs24 and in humans25 subject to myocardial I/R. The cardioprotective effects of long-term dietary intake of water-soluble barley-derived (1.3) β-D-Glucan (BBG), whose antioxidant activity is higher than fungal β-Glucan26, have not yet been investigated.

Since pasta plays a key role in human nutrition and is very effective in providing a BBG-enriched diet27, we tested whether the daily intake of diet supplemented with pasta containing 3% BBG (P-BBG) noninvasively increases coronary collaterals and cell survival through the simultaneous endothelial expression of VEGF and Parkin, which might mitigate the cardiac injury due to post-ischemic reperfusion. For this purpose, we used an established murine open-chest model of acute cardiac I/R injury28,29. Finally, we further explored the BBG-induced VEGF and Parkin expression in cultured human umbelical endothelial cells (HUVECs) at rest and during acute exposure to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which is an established model of early post-ischemic reperfusion injury in vitro 30.

Results

Effects of P-BBG diet on body weight, food intake and blood glucose levels

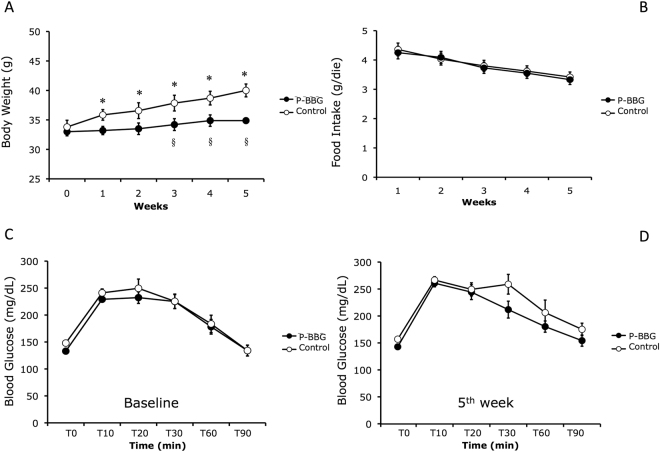

As shown in Fig. 1A, starting from the baseline, mice fed with the P-BBG diet did not gain weight compared to the Control group. The difference in body weight gain between groups was significant after three, four and five weeks, yet the daily food intake was similar between the two groups (Fig. 1B). At the fifth week of the diet, the basal blood glucose levels (T0) were similar to corresponding values before the diet (baseline) in each experimental group. During the intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT), the profile of blood glucose levels was similar between the two groups before (Fig. 1C) and after (Fig. 1D) the experimental feeding.

Figure 1.

Long-term intake of P-BBG diet prevents body weight gain without altering glucose tolerance. (A) Time-dependent effects of diet supplemented with P-BBG (n = 15) or regular pasta (Control; n = 15) on murine body weight. (B) Time-dependent changes in food intake in both experimental groups. (C) Levels of blood glicemia before (T0) and after intraperitoneal bolus of glucose solution (1 mg/g body weight) at baseline in P-BBG (n = 15) and Control group (n = 15). (D) Levels of blood glicemia before (T0) and after intraperitoneal bolus of glucose solution (1 mg/g body weight) after 5 weeks of experimental feeding in both experimental groups. P-BBG: low fat diet supplemented with barley beta-D-glucan enriched pasta (3 g/100 g of dry weight). All measurements are mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 vs. 0 weeks; § p < 0.05 vs. Control.

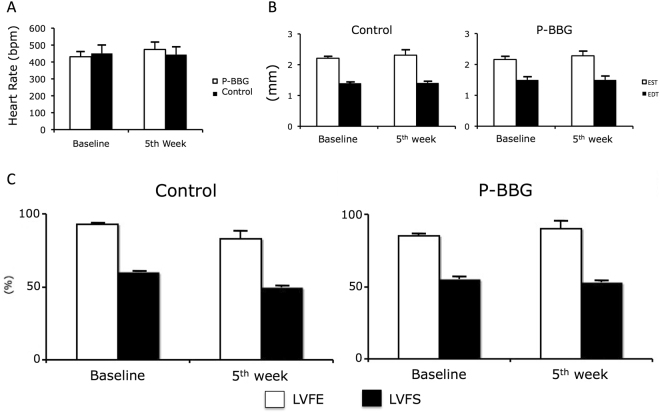

Effects of P-BBG diet on heart rate and cardiac function

As shown in Fig. 2, after five weeks of regular feeding, the P-BBG diet did not adversely affect the heart rate, the left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic wall thickness, and the LV systolic function of mice.

Figure 2.

Long-term intake of P-BBG diet does not alter cardiac function. (A) The heart rate at baseline and after five weeks of diet is similar in P-BBG (n = 15) and Control (n = 15) mice. (B) The sustained intake of diet supplemented with P-BBG does not alter both the end-systolic and end-diastolic left ventricular (LV) wall thickness, which are similar to Control mice. (C) The indexes of global LV function are not altered by diet in each experimental group. P-BBG: low fat diet supplemented with barley beta-D-glucan enriched pasta (3 g/100 g of dry weight); EST: end-systolic thickness; EDT: end-diastolic thickness; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; LVFS: left ventricular fractional shortening. All measurements are mean ± SD.

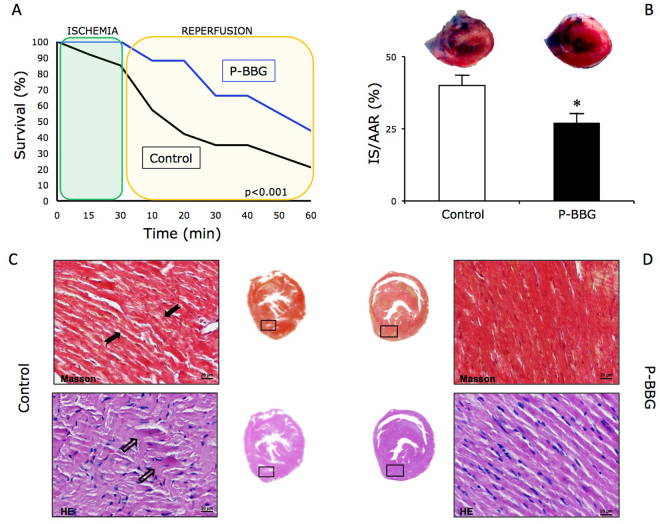

Effects of P-BBG diet on survival, infarct scar size and myocardial structure after left ventricular ischemia/reperfusion injury

As shown in Fig. 3A, 44% of the mice fed with the P-BBG diet survived after one hour of post-ischemic reperfusion, whereas only 21% of the Control animals survived after a similar injury at the same time. Hearts harvested from Control mice that had undergone I/R, showed a larger LV necrotic infarct area than those collected from infarcted P-BBG mice (Fig. 3B). The Masson and hematoxylin-eosin staining of LV tissue revealed contraction band necrosis in the hearts of Control mice (Fig. 3C), but not in treated mice (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Effects of long-term intake of P-BBG diet on left ventricular ischemia/reperfusion injury. (A) The survival rate of mice chronically fed with P-BBG diet (n = 15) exposed to cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury is significantly higher than Control (n = 15) mice. (B) P-BBG diet reduced the left ventricular (LV) infarct size compared to Control mice. The LV infarct size was quantified as a percentage of the ischemic area at risk (IS/AAR (%)) (see methods section). (C) Effects of Control diet on the occurrence of contraction band necrosis in Masson (black arrows) and in hematoxylin-eosin (transparent arrows) staining of LV tissue. (D) Effects of P-BBG diet on the occurrence of contraction band necrosis in Masson and in hematoxylin-eosin staining of LV tissue. P-BBG: low fat diet supplemented with barley beta-D-glucan enriched pasta (3 g/100 g of dry weight); IS/AAR: infarct size/area at risk; HE: hematoxylin-eosin. All measurements are mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 vs Control.

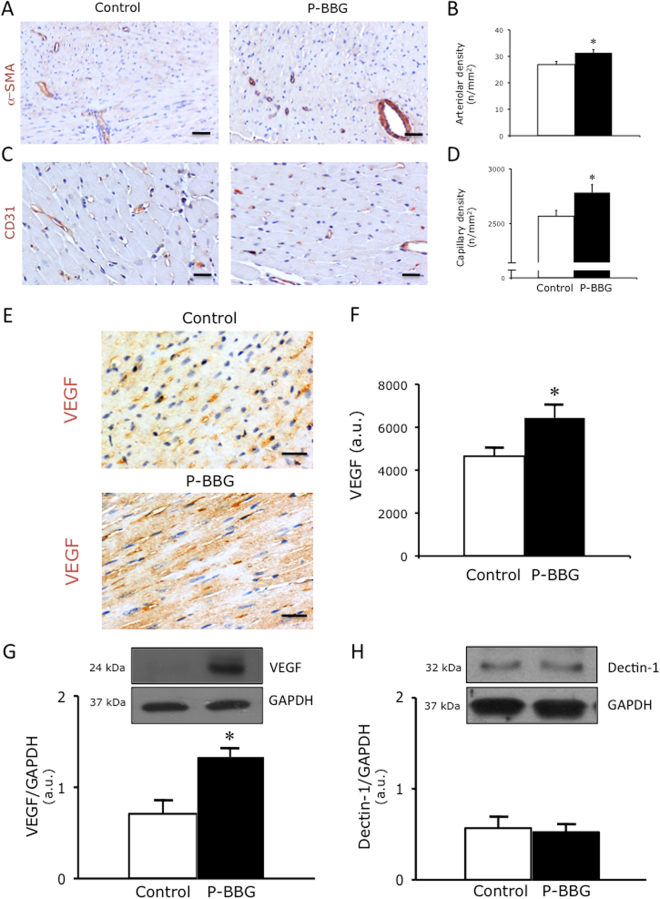

Effects of P-BBG diet on capillary and arteriolar density, VEGF and dectin-1 protein levels

The myocardial capillary (Fig. 4A–B) and arteriolar (Fig. 4C–D) density of the P-BBG mice was significantly higher than that of the Control hearts. As shown in panels E and F of Fig. 4, cardiac VEGF was considerably more evident in P-BBG than in the Control mice. Similarly, the VEGF protein levels of P-BBG hearts were significantly higher than those of the Control hearts (Fig. 4G). Higher levels of VEGF did not affect the myocardial expression of dectin-1, whose protein levels were similar in both groups (Fig. 4H).

Figure 4.

Effects of long-term intake of P-BBG diet on left ventricular capillary and arteriolar density, VEGF and dectin-1 protein levels. (A) Representative images of left ventricular (LV) coronary arterioles stained with α–smooth muscle actin in Control and P-BBG hearts. (B) The P-BBG diet (n = 15) increased the number of LV coronary arterioles compared to Control group (n = 15); the results are shown as number of arterioles per mm2. (C) Representative images of LV coronary capillaries stained with CD31 in Control and P-BBG hearts. (D) The P-BBG diet (n = 15) increased the number of LV coronary capillaries compared to Control diet (n = 15); the results are shown as number of capillaries per mm2. (E) Representative images of myocardial VEGF detected in Control and P-BBG left ventricles. (F) The P-BBG diet (n = 15) determined a detectable elevation of myocardial VEGF compared to Control diet (n = 15); the results are shown as arbitrary units of intense VEGF staining. (G) P-BBG diet (n = 7) increased the myocardial protein expression of VEGF compared to Control diet (n = 7). Levels of VEGF are expressed as arbitrary units of VEGF (24 kDa, MW)/GAPDH (37 kDa, MW) ratio. Representative images of cropped densitometric bands of VEGF are shown. The full-length blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Figure 1A. (H) Representative images of cropped densitometric bands of dectin-1 are shown. The full-length blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Figure 1B. The myocardial protein levels of dectin-1 are similar in both Control (n = 7) and P-BBG (n = 7) hearts. Levels of dectin-1 are expressed as arbitrary units of dectin-1 (28 kDa, MW)/GAPDH (37 kDa, MW) ratio. P-BBG: low fat diet supplemented with barley beta-D-glucan enriched pasta (3 g/100 g of dry weight); α-SMA: α–smooth muscle actin; CD31: cluster of differentiation 31; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. All measurements are mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 vs. Control.

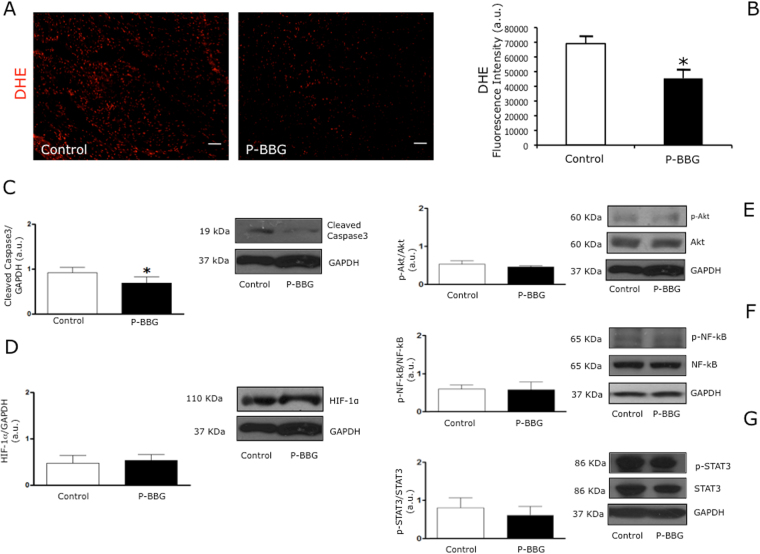

Effects of P-BBG diet on levels of myocardial oxidative stress, cleaved caspase-3, HIF1-α, pAkt/Akt, pSTAT3/STAT3 and pNF-kB/NF-kB

As shown in panels A and B of Fig. 5, the myocardial production of anion superoxide in response to I/R insult was significantly reduced in P-BBG compared to the Control hearts. At one hour of post-ischemic reperfusion, the myocardial cleavage of caspase-3 in the P-BBG hearts was markedly attenuated compared to the Control hearts (Fig. 5C) in the presence of similar protein levels of hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF1-α) (Fig. 5D). The phospho(p)Akt/Akt (Fig. 5E), pSTAT3(signal transducer and activator of transcription 3)/STAT3 (Fig. 5F) and pNF-kB(nuclear factor Kappa b)/NF-kB (Fig. 5G) ratios were similar in both experimental groups.

Figure 5.

Effects of P-BBG diet on levels of myocardial oxidative stress, cleaved caspase-3, HIF-1α, pAkt/Akt, pSTAT3/STAT3 and pNF-kB/NF-kB. (A) Representative images of DHE (dihydroethidium) staining of Control and P-BBG left ventricles. (B) P-BBG diet (n = 15) prevented an increase in anion superoxide generation following cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury compared to Control diet (n = 15); the results are shown as arbitrary units of fluorescence intensity (see Methods). (C) The myocardial levels of cleaved caspase-3 were lower in P-BBG (n = 7) than Control (n = 7) hearts. Levels of cleaved caspase-3 are expressed as arbitrary units of cleaved caspase-3 (19 kDa, MW)/GAPDH (37 kDa, MW) ratio. Representative images of cropped densitometric bands of cleaved caspase 3 AND GAPDH are shown. The full-length blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Figure 1C. (D) The myocardial levels of HIF-1α are similar in P-BBG (n = 7) and Control (n = 7) hearts. Levels of HIF-1α are expressed as arbitrary units of HIF-1α (110 kDa, MW)/GAPDH (37 kDa, MW) ratio. Representative images of cropped densitometric bands of HIF-1α and GAPDH are shown. The full-length blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Figure 1C. (E) The myocardial levels of p-Akt/Akt ratio are similar in P-BBG (n = 7) and Control (n = 7) hearts. Levels of p-Akt (60 kDa, MW)/Akt (60 kDa, MW), normalized to GAPDH levels, are expressed as arbitrary units. Representative images of cropped densitometric bands of p-Akt, Akt and GAPDH are shown. The full-length blots/gels are shown in Supplementary Figure 1C. (F) The myocardial levels of p-NF-kB/NF-kB ratio are similar in P-BBG (n = 7) and Control (n = 7) hearts. Levels of p-NF-kB (65 kDa, MW)/NF-kB (65 kDa, MW), normalized on GAPDH levels, are expressed as arbitrary units. Representative images of cropped densitometric bands of p-NF-kB, NF-kB and GAPDH are shown. The full-length blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Figure 1D. (G) The myocardial levels of p-STAT3/STAT3 ratio are similar in P-BBG (n = 7) and Control (n = 7) hearts. Levels of p-STAT3 (86 kDa, MW)/STAT3 (86 kDa, MW), normalized on GAPDH levels, are expressed as arbitrary units. Representative images of cropped densitometric bands of p-STAT3, STAT3 and GAPDH are shown. The full-length blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Figure 1E. P-BBG: low fat diet supplemented with barley beta-D-glucan enriched pasta (3 g/100 g of dry weight); HIF-1α: hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; p-Akt: phospho-Akt; p-NF-kB: phospho- nuclear factor Kappa b; p-STAT3: phospho- signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. All measurements are mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 vs. Control.

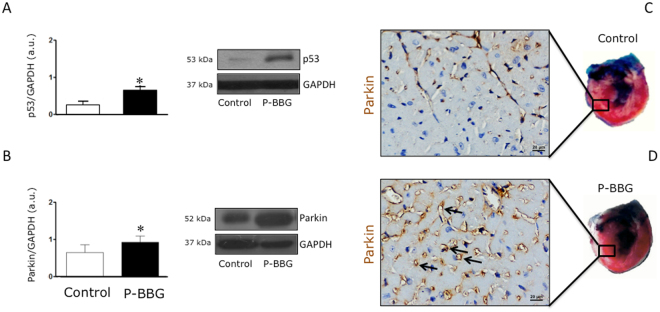

Effects of P-BBG diet on myocardial levels of p53 and Parkin

As shown in Fig. 6A, the myocardial protein expression of p53 was higher in P-BBG than the Control mice. Conversely, Parkin protein levels were significantly upregulated in P-BBG compared with the Control hearts (Fig. 6B). Although Parkin was weakly detectable in the Control hearts (Fig. 6C), its expression was highly focused in the coronary endothelial cells of the P-BBG hearts (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

Effects of P-BBG diet on levels of myocardial p53 and Parkin. (A) P-BBG diet (n = 7) increased the myocardial protein levels of p53 compared to Control (n = 7) diet. Levels of p53 are expressed as arbitrary units of p53 (53 kDa, MW)/GAPDH (37 kDa, MW) ratio. Representative images of cropped densitometric bands of p53 and GAPDH are shown. The full-length blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Figure 1F. (B) P-BBG diet (n = 7) increased the myocardial protein levels of Parkin compared to Control diet (n = 7). Levels of Parkin are expressed as arbitrary units of Parkin (52 kDa, MW)/GAPDH (37 kDa, MW) ratio. Representative images of cropped densitometric bands of Parkin and GAPDH are shown. The full-length blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Figure 1G. (C) Representative images of Parkin localization in coronary endothelium of Control left ventricles. (D) Representative images of Parkin localization in coronary endothelium of P-BBG left ventricles. P-BBG: low fat diet supplemented with barley beta-D-glucan enriched pasta (3 g/100 g of dry weight); GAPDH: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. All measurements are mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 vs. Control.

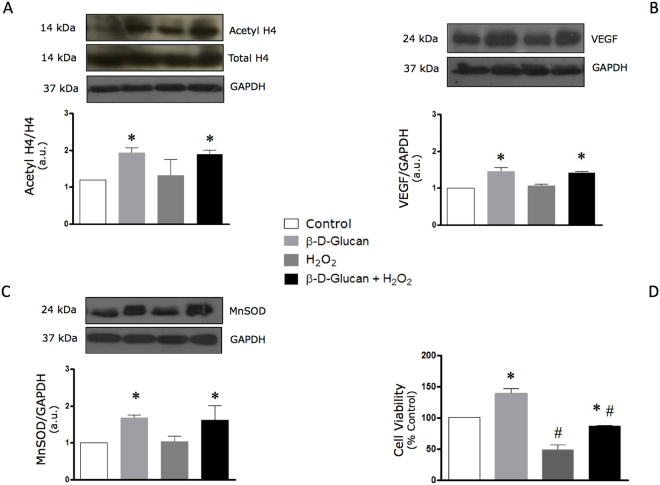

Acute oxidative stress does not affect the levels of H4 histone acetylation, VEGF and MnSOD in viable endothelial cells treated with barley β-D-glucan

As shown in Fig. 7, the BBG-induced increase in endothelial levels of H4 histone acetylation (panel A), VEGF (panel B) and MnSOD (panel C) were not altered during the transient exposure of HUVECs to exogenous H2O2. The decay of cell viability following the acute exposure to hydrogen peroxide was significantly preserved by long-term treatment with BBG (panel D).

Figure 7.

Acute oxidative stress does not affect levels of H4 histone acetylation, VEGF and MnSOD in viable endothelial cells chronically treated with barley β-D-glucan. (A) 7-day treatment with 3% barley β-D-glucan (BBG) increases the endothelial levels of acetyl H4 histone compared to untreated HUVECs, which are not affected by acute oxidative stress. Levels of acetyl H4 (14 kDa, MW)/H4 (14 kDa, MW), normalized on GAPDH levels, are expressed as arbitrary units. Representative images of cropped densitometric bands of acetyl H4, H4 and GAPDH are shown. The full-length blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Figure 2A. (B) The protein levels of VEGF in HUVECs increase after long-term exposure to 3% BBG compared to untreated cells at rest and during acute oxidative stress. Levels of VEGF are expressed as arbitrary units of VEGF (24 kDa, MW)/GAPDH (37 kDa, MW) ratio. Representative images of cropped densitometric bands of VEGF and GAPDH are shown. The full-length blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Figure 2B. (C) The protein levels of MnSOD in HUVECs are increased after long-term exposure to 3% BBG compared to untreated cells, yet are not altered after 1 h exposure to hydrogen peroxide (see Methods). Levels of MnSOD are expressed as arbitrary units of MnSOD (24 kDa, MW)/GAPDH (37 kDa, MW) ratio. Representative images of cropped densitometric bands of MnSOD and GAPDH are shown. The full-length blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Figure 2C. (D) BBG promotes the endothelial cell survival after 1 hour treatment with 400 μM H2O2. HUVECs: human umbelical vascular endothelial cells; H4: histone H4; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; MnSOD: manganese superoxide dismutase; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; H2O2: hydrogen peroxide. All measurements are mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 vs. untreated condition; #p < 0.05 vs. resting condition.

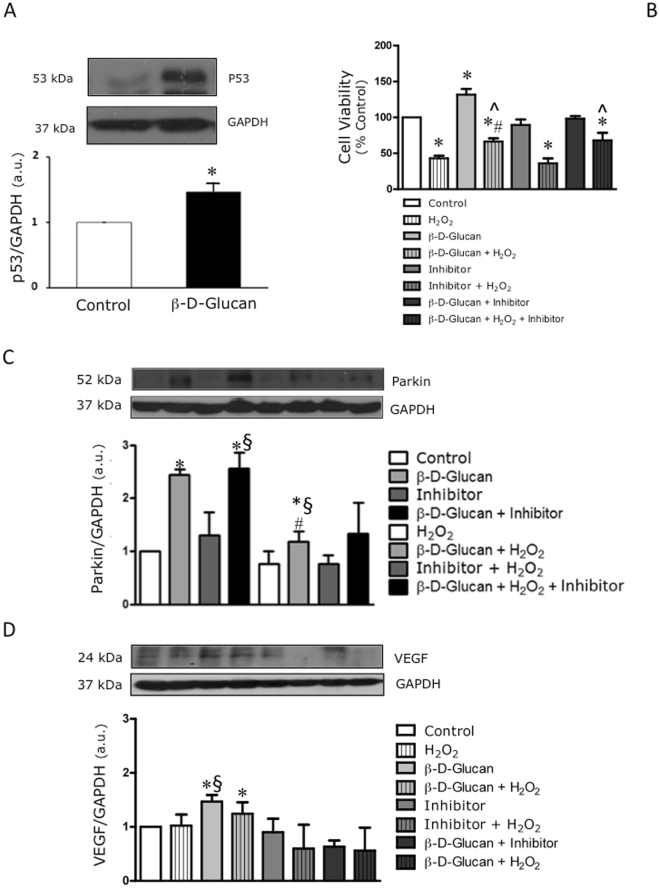

BBG induces the protein expression of Parkin independently of p53 activity

The interplay between p53, VEGF and Parkin governs tissue homeostasis through the modulation of angiogenesis31 and cellular tolerance to stress32. BBG increases the expression of p53 (Fig. 8A) without affecting cell viability, but preserving the cell viability under H2O2 (Fig. 8B). Although pifithrin-alpha (PFT-α), a well-known inhibitor of p53 activity, does not affect cell viability in resting conditions, it is unable to protect the cells against acute oxidative stress (Fig. 8B). Interestingly, the BBG-induced increase in protein levels of Parkin is not affected by PFT-α. In line with the BBG effects on the viability of H2O2-stressed cells during co-exposure to PFT-α (Fig. 8B), BBG attenuates the decay of Parkin protein levels in HUVECs exposed to acute oxidative stress independently of p53 activity (Fig. 8C). Conversely, the inhibition of p53 activity by PFT-α counteracts the BBG-induced VEGF expression in HUVECs at rest and during stress (Fig. 8D).

Figure 8.

BBG induces the protein expression of Parkin independently of p53 activity. (A) 7-day treatment with 3% barley β-D-glucan (BBG) increases the endothelial levels of p53 compared to untreated HUVECs. Levels of p53 are expressed as arbitrary units of p53 (53 kDa, MW)/GAPDH (37 kDa, MW) ratio. Representative images of cropped densitometric bands of p53 and GAPDH are shown. The full-length blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Figure 2D. (B) The sustained co-treatment of HUVECs with 3% BBG and PFT-α (Inhibitor) does not impair cell viability. BBG preserves the viability of H2O2-stressed cells, but not Inhibitor. (C) The sustained treatment of HUVECs with 3% BBG increases the protein levels of Parkin compared to untreated cells (Control). The co-treatment with PFT-α does not affect the BBG-induced protein expression of Parkin. In addition, the decay of Parkin protein expression in stressed BBG-treated cells is smaller than in stressed untreated cells. (D) HUVECs co-treated with 3% BBG and PFT-α show lower protein levels of VEGF. GAPDH: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; PFT-α: pifithrin-alpha; H2O2: hydrogen peroxide; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor. All measurements are mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 vs. untreated condition; §p < 0.05 vs. Inhibitor; #p < 0.05 vs. corresponding resting condition; ^p < 0.05 vs H2O2.

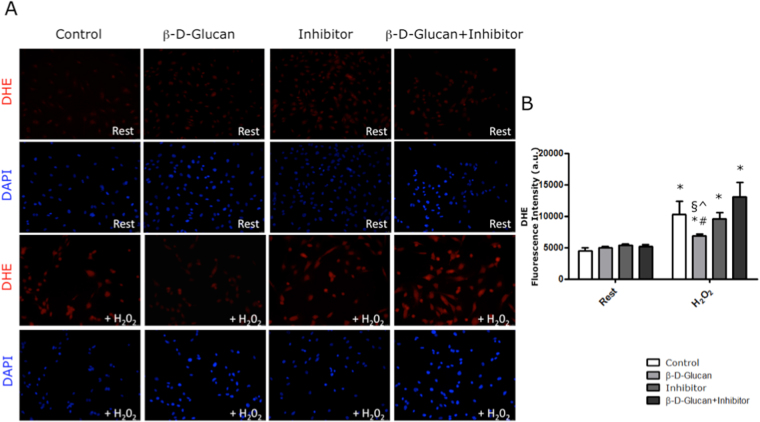

BBG prevents the rise of anion superoxide levels in a p53-dependent manner

BBG precludes the rise of anion superoxide levels in H2O2-stressed endothelial cells, as previously reported by us22. HUVECs co-treated for seven days with BBG and non-toxic concentration of PFT-α do not show anion superoxide levels higher than Control cells (Fig. 9A). Interestingly, the inhibition of p53 activity by PFT-α counteracts the BBG-induced reduction of anion superoxide levels in HUVECs exposed to acute oxidative stress (Fig. 9B).

Figure 9.

BBG prevents the rise of anion superoxide levels in a p53-dependent manner. (A) Representative images of DHE (dihydroethidium) staining of HUVECs at rest and after acute oxidative stress (+H2O2). (B) At rest, the 7-day treatment with 3% BBG (β-D-Glucan), PTF-α (Inhibitor) and β-D-Glucan + Inhibitor did not increase the anion superoxide levels in untreated HUVECs (Control). At stress (+H2O2), β-D-Glucan prevented an increase in anion superoxide generation compared to untreated cells (Control). Conversely, the 7-day co-treatment with β-D-Glucan + Inhibitor precluded the anti-oxidant effects of BBG in cells exposed to acute oxidative stress. The results are shown as arbitrary units of fluorescence intensity (see Methods). PFT-α: pifithrin-alpha; H2O2: hydrogen peroxide. All measurements are mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 vs. corresponding resting condition; #p < 0.05 vs. Control + H2O2; §p < 0.05 vs. Inhibitor + H2O2; ^p < 0.05 vs. β-D-Glucan + Inhibitor + H2O2.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that the long-term supplementation of a low fat diet with pasta enriched with BBG increases the survival rate of mice undergoing LV I/R injury. The magnitude of the LV infarct scar size and of the contraction necrotic bands was safely attenuated in mice fed with P-BBG for five weeks. The dietary intake of P-BBG also prevented an increase in body weight without altering the systemic glucose tolerance, cardiac function, and the well-being of mice. Compared to the Control group, the histological analysis revealed a higher density of coronary capillaries and arterioles in the explanted hearts of P-BBG mice, which support higher tissue viability downstream of the obstructed coronary tree. Regarding the cardioprotective pathways, our data revealed, for the first time, the relationship between myocardial VEGF, p53 and Parkin protein upregulation, vasculogenesis enhancement and reduction of caspase-3 cleavage at the early stages of post-ischemic reperfusion conferred by the sustained dietary intake of P-BBG.

It is largely recognised that cardiac ischemic preconditioning enhances the myocardial protein expression of VEGF33, a growth factor that induces myocardial angiogenesis and cell survival34. In line with the cardioprotective effects of VEGF, other researchers have perfused the heart with VEGF35 or have upregulated the myocardial VEGF expression using gene therapy36,37 in order to enhance the local adaptive response naturally occurring under oxidative microenvironment. However, none of these invasive approaches may be ethically permissible in healthy subjects. Hence, the urgent need to develop a noninvasive strategy to enhance collateral artery growth in the adult myocardium and to promote the survival of cardiac cells following I/R injury.

In a previous study, we demonstrated that chronic exposure of endothelial cells to water-soluble BBG enhances the pro-angiogenic and pro-survival expression of manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD)22, which is a mediator of ischemic preconditioning38.

In the current study, we thus hypothesized that the daily dietary intake of water-soluble BBG might promote the formation of new coronary vessels in healthy subjects and prevent myocardial I/R injury.

For this purpose, healthy mice were fed with a low fat diet supplemented with pasta made with a mixture of barley flour and wheat flour, which guarantees a high content of viscous polysaccharides and a regular BBG intake. Our hypothesis is supported by the evidence that pasta safely provides a BBG-enriched diet27,39. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has assessed the effects of diet supplemented with BBG-enriched pasta to counteract the onset of myocardial I/R injury.

First, we have observed that P-BBG-enriched diet precludes gain weight in mice. Our data are consistent with recent clinical study showing that daily intake of barley beta-D-Glucan prevents visceral fat obesity and body weight gain in humans40. In fact, the ability of soluble BBG to form highly viscous solutions in the human gut slows gastric emptying, digestion and absorption of dietary fat41.

In our study, the survival rate at an early stage of post-ischemic reperfusion was significantly higher in mice fed with P-BBG than with the wheat pasta. Compared to the Control group, the IS/AAR ratio revealed that the left ventricles of P-BBG mice were less injured and the contraction band necrosis, a hallmark of immediate necrotic cell death during the first minutes of reperfusion42, was undetectable in treated hearts. Since myocardial injury is induced after an overnight fasting period, it is conceivable that cardioprotection depends on increased myocardial angiogenesis due to the sustained intake of P-BBG. Our hypothesis is well supported by previous clinical evidence showing that individual tolerance to cardiac post-ischemic reperfusion injury is due to a higher density of coronary collaterals4,5.

In line with our hypothesis, the myocardial density of coronary capillaries and arterioles was higher in mice fed with a diet supplemented with P-BBG than with regular pasta. Although the myocardial protein levels of dectin-1, a receptor that mediates endothelial β-D-Glucan effects43, were similar in both experimental groups, the marked increase in VEGF protein levels in the P-BBG hearts is noteworthy and is closely linked to the regular intake of BBG and to the weight loss. Indeed, we cannot exclude that BBG-based diet may induce VEGF expression in other tissues. It is known that an increase in VEGF expression in adipose tissue can result in increasing vascular density44, in reducing adipocyte size and in precluding gain weight in mice45,46.

In addition, the myocardial levels of anion superoxide decreased significantly in the reperfused hearts of mice fed with P-BBG rather than in the Control mice.

These new in vivo findings strongly support our previous study22. In fact, VEGF likely enhances the local expression of MnSOD23, a key anti-oxidant enzyme, which contributes to the angiogenesis22 and higher cardiac tolerance against ischemia/reperfusion injury47 in P-BBG mice.

Since natural compounds may promote VEGF/antioxidant signaling and inhibit the onset of apoptosis in hearts undergoing I/R48, we assessed the myocardial levels of cleaved caspase-3, an established pro-apoptotic factor. The levels of cleaved caspase-3 were significantly lower in P-BBG hearts, even though the myocardial protein expression of HIF-1α, a transcriptional factor involved in the induction of VEGF expression49 as well as in the inhibition of apoptosis50, was similar in both experimental groups. These results are in agreement with our previous in vitro study22 and suggest the activation of different signaling pathways by BBG.

Although several studies have found a key role for phosphorylated Akt to mediate the cardioprotective phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling pathway51 during preconditioning, the myocardial levels of phospho-Akt/total-Akt ratio were the same in treated and untreated mice.

We then examined the role of the P-BBG diet on myocardial STAT3 signaling pathways since STAT3 activation has been implicated in the inhibition of caspase-3 cleavage52 and also in the upregulation of MnSOD53 and VEGF54 genes. Surprisingly, cardiac STAT3 was also similarly expressed and phosphorylated in both experimental groups.

Lastly, although active NF-kB promotes the VEGF-dependent modulation of MnSOD expression55, the myocardial levels of phospho-NF-kB/total-NF-kB ratio were similar in both the P-BBG and Control hearts.

Although the activation of the pathways so far investigated plays a role in regulating VEGF levels during preconditioning, it seems that they are not activated by BBG in our model. Since p53 has been recently considered an important regulator of cardiac gene transcription56, we have hypothesized that it may play a key role in mediating the BBG-induced cardioprotection.

Farhang Ghahremani et al.57 demonstrated that p53 induces the expression of VEGF. In our study, the expression of p53 in P-BBG hearts was higher than in the Control hearts. It is conceivable that p53 leads to VEGF promoter activation by acting synergistically with HIF-1α, as previously demonstrated by others57.

We have demonstrated, for the first time, that dietary intake of P-BBG induces myocardial p53 upregulation without promoting systemic toxicity or cardiac cell death. Our findings are not in agreement with a previous study that found that dietary anti-oxidants increase p53 levels to the point where they induce apoptosis58. This can be explained by the fact that P-BBG diet also increased the myocardial protein expression of Parkin, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, which plays a key role in promoting mitophagy59 and in delaying caspase-3 activation60. Since healthy mice were safely fed with the P-BBG-enriched diet for five weeks, our results would seem to suggest that the physiological interplay between higher levels of p53 and Parkin may contribute to the non-invasive regulation of the VEGF expression and myocardial viability status.

As β-Glucan receptors are expressed on the surface of endothelial cells61, the upregulation of Parkin protein was localized in the coronary endothelial cells of P-BBG hearts. The binding affinity of dectin-1 to β-D-Glucan and its biological activity are similar in humans and mice22,62, it would thus appear that we have revealed BBG-dependent mechanisms in cultured HUVECs at rest and under acute oxidative stress. On day 7 after the exposure of HUVECs to 3% BBG, the levels of acetylated H4 histone, VEGF and MnSOD increased and were not affected by acute oxidative stress. Our in vitro results suggest that the acute oxidative burst induced by I/R injury in vivo did not counteract the BBG-induced regulatory effects on the abovementioned proteins.

Finally, we have demonstrated that the 7-day treatment of HUVECs with BBG similarly increased the protein expression of p53 and Parkin in the presence of increased histone acetylation. Our data agree with previous studies showing that class I HDAC inhibitors, such as BBG, upregulate the protein expression of p5363 and Parkin64. As a function of expression levels, p53 can either prevent or promote apoptosis65. In vitro, however, BBG-induced p53 upregulation did not affect the viability of endothelial cells.

Although the inhibition of p53 activity is essential to enhancing the mitophagic activity of Parkin66, it is still unknown whether the VEGF and Parkin protein expression induced by BBG depends on p53 activity. Consequently we performed additional experiments by treating HUVECs with BBG in the presence of PFT-α, an established inhibitor of p53 activity66. Although PFT–α did not alter the expression of Parkin, the BBG-induced upregulation of Parkin was not affected by inhibition of p53 activity.

At least, BBG mitigates the H2O2-induced reduction of Parkin protein expression independently of p53 activity. Hence, our results suggest that the Parkin expression induced by BBG is independent of p53 activity. Conversely, the BBG-induced increase in VEGF protein levels was hampered by PFT–α, which confirms that BBG increased the VEGF expression in a p53-dependent manner. Similarly, PFT–α hindered the BBG-induced decrease in anion superoxide levels in stressed cells, which confirms that BBG decreased the oxidative stress in a p53-dependent manner. Our findings reveal for the first time the impact of BBG on the simultaneous endothelial expression of VEGF and Parkin interacting differently with p53 activity. Moreover, we have demonstrated that the anti-oxidant effects of BBG depends on the p53 activation.

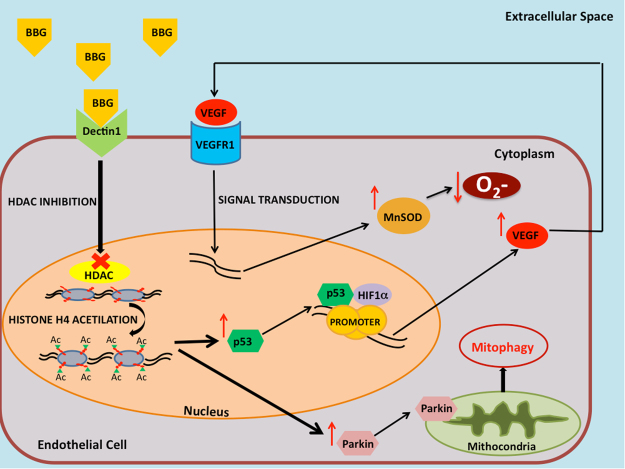

Therefore, by enhancing class I HDAC inhibition, the long-term dietary intake of P-BBG may simultaneously promote the neoangiogenesis and higher tolerance to oxidative stress due to enhanced endothelial expression of VEGF/MnSOD signaling and Parkin (the proposed mechanism is summarized in Fig. 10).

Figure 10.

Proposed mechanism of BBG-mediated regulation of endothelial tolerance to ischemia-reperfusion injury The proposed mechanism of BBG-mediate regulation of endothelial tolerance to oxidative stress following ischemia-reperfusion injury through upregulation of VEGF and Parkin. BBG: barley-derived (1.3) β-D-Glucan; HDAC: class I histone deacetylase; Ac: acetyl; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; VEGFR1: vascular endothelial growth factor receptor type 1; HIF-1α: hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha; MnSOD: manganese superoxide dismutase; O2−: anion superoxide.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to show in vivo data demonstrating that a sustained dietary intake of pasta enriched with BBG safely increases coronary collaterals, limits the infarct size, and reduces mortality. This is achieved through the simultaneous myocardial upregulation of p53, VEGF and Parkin without interfering with the ability of cardiac cells to phosphorylate Akt, STAT3 and NF-kB during the post-ischemic reperfusion. Higher p53, VEGF and Parkin protein levels in endothelial cells chronically treated with BBG are not affected by exposure to acute oxidative stress. Finally, Parkin responsiveness to BBG is not driven by the inhibition of p53 activity, which in turn may contribute to VEGF expression31 and anion superoxide decay.

We believe our findings will help in the design a novel nutraceutical approach in the clinical noninvasive prevention of cardiac I/R injury.

Methods

Experimental protocol and animal model of left ventricular I/R injury

Thirty adult male C57BL/6 J mice (body weight 22–25 g; 4–8 weeks old) were housed with a constant light and dark phase of 12 hours at 20–23 °C. They were fed for five weeks with a low fat diet (LFD; 3.085 Kcal/g metabolizable energy; 3.5% fat; 17.6% proteins; A. Rieper SpA, BZ, Italy) supplemented with BBG-enriched pasta (3 g/100 g of dry weight) (P-BBG, n = 15) or regular wheat pasta (Control, n = 15), kindly provided by Granoro srl (Corato, Italy). The body weight and food intake of mice were assessed once a week. The composition of the diets is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Composition of normal diet supplemented with regular or functional pasta.

| Control | P-BBG | |

|---|---|---|

| Proteins (%) | 17.6 | 17.6 |

| Fat (%) | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| Carbohydrates (%) | 60.3 | 61.6 |

| Ashes (%) | 5.5 | 4.1 |

| Others (%) | 3.7 | 3.7 |

| Calories (Kcal/g) | 3.085 | 3.085 |

P-BBG, low fat diet supplemented with barley beta-D-glucan enriched pasta (3 g/100 g of dry weight).

At the beginning and the end of the experimental feeding, transthoracic echocardiography67 and an intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test68 were performed in 6 h fasted mice. At the end of the fifth week of the diet, the mice underwent acute myocardial I/R, as previously described69. Briefly, the chest was opened and the left anterior descending coronary artery was transiently ligated at 2 mm lower than the tip of the left auricle in animals anesthetized with isoflurane (1.5–2%) in 100% oxygen with a flow rate of 0.4 L/min until loss of righting reflex, ventilated via a tracheal intubation at a tidal volume of 0.30 ml and respiratory rate of 100 breaths/min (Ugo Basile Srl, Varese, Italy). Body temperature was maintained constant between 36.8 °C and 37 °C by a thermoregulated surgical table connected to a rectal probe (Ugo Basile Srl, Varese, Italy). Thirty minutes of coronary occlusion was followed by reperfusion for 60 min under monitoring of three-lead electrocardiography (ECG). At the end of myocardial reperfusion, the LAD was reoccluded and the phtalocyanine blue dye was injected into the LV cavity to perfuse the nonischemic portions of the myocardium. Then, the heart was rapidly removed for infarct size, histological and molecular assessment. All animal procedures were approved by the Italian Ministry of Health and conducted in conformity with the guidelines from Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes.

Transthoracic echocardiography

Cardiac function in mice lightly sedated by intraperitoneal injection with Zoletil® (tiletamine 15 mg/kg, zolazepam 15 mg/kg; Virbac, Peakhurst, New South Wales, Australia) was assessed by transthoracic echocardiography using a commercially available ecocardiographer equipped with a 12-MHz probe (MyLab30, Esaote, Italy), as previously described70.

Each parameter was measured using B-mode guided M-mode imaging in the parasternal short axis-view at the level of the papillary muscles. Images were analysed offline in a blinded fashion. The global cardiac function was calculated as the percentage ejection fraction of the left ventricle (%LVFE). Heart rate was simultaneously obtained with a three-lead ECG monitor.

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test

The glucose tolerance test was performed as previously described68. Briefly, glucose sterile solution was intraperitoneally injected (1 mg/g body weight) in each awake 6 h fasting mouse after baseline blood glucose measurement. The blood glucose levels were measured at 10, 20, 30, 60, and 120 min after bolus glucose.

Infarct size, histological and immunohistochemical assays

The LV infarct size was assessed as previously described28. Each one-millimeter-thick left ventricular transverse section was photographed with a light microscopy (Olympus BX43) at 10X original magnification and digitized by a video system (Olympus DP20 camera) interfaced with a computer with dedicated software (CellSens Dimension, Olympus) for morphometric and/or color analysis. The infarct size (IS; non stained by 1% solution of 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride, Sigma-Aldrich) was measured with Image J software, and expressed as percentage of the ischemic area at risk (AAR; non stained by phtalocyanine blue dye, Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co, MO, USA).

Serial 5-μm frozen heart sections were stained with H&E for overall morphology assessment. The density of the left ventricular coronary arterioles and capillaries stained by immunohistochemistry was quantified as the number of smooth muscle α-actin - (α-SMA, 1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, USA) and/or CD31-positive structures (1:100, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, UK) per mm2 using Image J. Finally, to show the cell source of VEGF, additional LV sections were further stained with an anti-VEGF antibody (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, USA).

Detection of myocardial anion superoxide generation

We used a dihydroethidium assay (DHE; Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co, MO, USA) to examine the anion superoxide formation in the frozen heart tissue sections, as previously described71. In vitro, endothelial superoxide anion generation was determined by staining of HUVECs in each experimental condition as previously described by us22. Fluorescence microscopy was performed with a Leica TCS DMIRE 2 (LCS Lite Software; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Western blot assays

Heart tissues were homogenized in a RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Pierce, Rockford, USA) at high-frequency (25 Hz) with TissueLyser (Quiagen S.p.A, Milan, Italy). Homogenates were centrifuged at 12000 g for 15 minutes at 4 °C to remove nuclei and cell debris. The protein concentration in supernatants was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, USA). Equal amounts of protein (30 μg) were fractionated by 8–15% SDS polyacrylamide gel and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (PVDF, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dried milk in TBS/Tween20 (0.01%) at room temperature (RT) for 1 hour, and then probed with primary antibodies at a p-Akt (p-Akt; 1:1000, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), total Akt (1:1000, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), p-STAT3 (1:1000, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) and total STAT3 (1:1000, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), which are pro-survival signaling proteins involved in some cardioprotective pathways72, Parkin (1:500, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, UK), a key protein mediating mitophagy59, p53 (1:1000, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, UK), a potential regulator of Parkin expression73, p-NF-kB (1:1000, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) and total NF-kB (1:1000, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), a transcriptional factor involved in the inflammatory response and VEGF secretion by cardiomyocytes74, cleaved-caspase3 (1:1000 Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, USA), a pro-apoptotic factor75, hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF1-α;1:1000 Abcam Inc., Cambridge, UK), VEGF (1:1000 Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, USA), manganese superoxide dismutase, a key antioxidant enzyme (MnSOD, 1:1000, Millipore, MA, USA), and dectin-1 (1:1000 Novus Biologicals, USA), the β-Glucan receptor.

The ratio between pan-acetylated histone H4 type (1:1000, Millipore, MA, USA) and total histone H4 type (1:1000, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, UK) was assessed as previously described22. The membranes were reprobed for GAPDH (1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, USA) to verify the uniformity of protein loading. The phospho/total ratio were calculated using the normalized values. After incubation with the above mentioned antibodies, and rinsing with TBS/Tween20 (0.01%) three times for 10 minutes, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated (HRP-conjugated) anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Abcam Inc., Cambrige, UK) for one hour at room temperature. Specific protein bands were detected using an ECL Plus Western blot detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., CA, USA). Densitometry analysis of protein bands was performed using ImageJ software (National Institute of Healt, USA). We checked the predicted molecular weight trough the use of Precision Plus Protein™ Dual Color Standards (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). All Western blot experiments were performed in triplicate.

Cell lines and in vitro experimental protocol

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs, Combrex Bio Science Inc, Walk-ensville, MD, USA) were cultured in EndoGroTM Basal Medium (Millipore, MA, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% L-glutamin. HUVECs were cultured with 3% w/v β-D-glucan (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co, MO, USA) or with PBS (negative control) for seven days and then were exposed for 1 h to H2O2 (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co, MO, USA) with a pro-apoptotic dose (400uM). The acute exposure to H2O2 recapitulates the reperfusion injury30. Unstressed cells were used as the Control. In order to evaluate the BBG-dependent regulation of endothelial Parkin protein expression, HUVECs were co-treated for seven days with BBG and non-toxic concentration of PFT-α (10 uM; Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co, MO, USA), a p53’s mitochondrial translocation inhibitor76.

MTT assay

After 1 h exposure to H2O2 or PBS, the cell viability was assessed using the MTT reduction assay (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co, MO, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and as previously described by us77.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD. One-way and two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test were used to compare multiple groups. P < 0.05 was set as a threshold for statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows, version 11.1 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). The survival curves were developed using the Kaplan-Meier function with the logrank test (GraphPad Prism 4.0).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a research grant provided by Pastificio Attilio Mastromauro Granoro s.r.l., Corato (BA), Italy (V.L.).

Author Contributions

Valentina Casieri: designed research, performed research; Marco Matteucci, Claudia Cavallini: performed research, collected data; Valentina Casieri, Marco Matteucci, Claudia Cavallini: analyzed and interpreted data; Milena Torti, Michele Torelli: contributed vital new reagents or analytical tools, interpreted data; Vincenzo Lionetti: designed research, interpreted data, wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-13949-1.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ. Myocardial reperfusion injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:1121–1135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoller M, Seiler C. Salient features of the coronary collateral circulation and its clinical relevance. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2015;145:w14154. doi: 10.4414/smw.2015.14154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shanmugam VB, Harper R, Meredith I, Malaiapan Y, Psaltis PJ. An overview of PCI in the very elderly. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2015;12:174–184. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen M, Rentrop KP. Limitation of myocardial ischemia by collateral circulation during sudden controlled coronary artery occlusion in human subjects: a prospective study. Circulation. 1986;74:469–476. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.74.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Regieli JJ, et al. Coronary collaterals improve prognosis in patients with ischemic heart disease. Int. J. Cardiol. 2009;132:257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.11.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chalothorn D, Clayton JA, Zhang H, Pomp D, Faber JE. Collateral density, remodeling, and VEGF-A expression differ widely between mouse strains. Physiol. Genomics. 2007;30:179–191. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00047.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meier P, et al. Beneficial effect of recruitable collaterals: a 10-year follow-up study in patients with stable coronary artery disease undergoing quantitative collateral measurements. Circulation. 2007;116:975–983. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.703959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Laan AM, Piek JJ, van Royen N. Targeting angiogenesis to restore the microcirculation after reperfused MI. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2009;6:515–523. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desch S, et al. Effect of coronary collaterals on long-term prognosis in patients undergoing primary angioplasty for acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 2010;106:605–611. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah AM, Mann DL. In search of new therapeutic targets and strategies for heart failure: recent advances in basic science. Lancet. 2011;378:704–712. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60894-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucitti JL, et al. Formation of the collateral circulation is regulated by vascular endothelial growth factor-A and a disintegrin and metalloprotease family members 10 and 17. Circ. Res. 2012;111:1539–1550. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.279109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Smet F, Segura I, De Bock K, Hohensinner PJ, Carmeliet P. Mechanisms of vessel branching: filopodia on endothelial tip cells lead the way. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009;29:639–649. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.185165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winegrad S, Henrion D, Rappaport L, Samuel JL. Vascular endothelial cell-cardiac myocyte crosstalk in achieving a balance between energy supply and energy use. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1998;453:507–514. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-6039-1_56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Domigan CK, et al. Autocrine VEGF maintains endothelial survival through regulation of metabolism and autophagy. J. Cell. Sci. 2015;128:2236–2248. doi: 10.1242/jcs.163774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lionetti V, Bianchi G, Recchia FA, Ventura C. Control of autocrine and paracrine myocardial signals: an emerging therapeutic strategy in heart failure. Heart Fail. Rev. 2010;15:531–542. doi: 10.1007/s10741-010-9165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li J, et al. VEGF, flk-1, and flt-1 expression in a rat myocardial infarction model of angiogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;270:H1803–1811. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.5.H1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bulysheva AA, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-A gene electrotransfer promotes angiogenesis in a porcine model of cardiac ischemia. Gene Ther. 2016;23:649–656. doi: 10.1038/gt.2016.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu W, et al. PINK1-Parkin-Mediated Mitophagy Protects Mitochondrial Integrity and Prevents Metabolic Stress-Induced Endothelial Injury. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang C, et al. Preconditioning involves selective mitophagy mediated by Parkin and p62/ SQSTM1. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubli DA, et al. Parkin protein deficiency exacerbates cardiac injury and reduces survival following myocardial infarction. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:915–926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.411363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woitek F, et al. Intracoronary Cytoprotective Gene Therapy: A Study of VEGF-B167 in a Pre-Clinical Animal Model of Dilated Cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015;66:139–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.04.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agostini S, et al. Barley beta-glucan promotes MnSOD expression and enhances angiogenesis under oxidative microenvironment. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2015;19:227–238. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abid MR, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor induces manganese-superoxide dismutase expression in endothelial cells by a Rac1-regulated NADPH oxidase-dependent mechanism. FASEB J. 2001;15:2548–2550. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0338fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aarsæther E, Straumbotn E, Rösner A, Busund R. Oral β-glucan reduces infarction size and improves regional contractile function in a porcine ischaemia/reperfusion model. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2012;41:919–925. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezr125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aarsaether E, Rydningen M, Einar Engstad R, Busund R. Cardioprotective effect of pretreatment with beta-glucan in coronary artery bypass grafting. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 2006;40:298–304. doi: 10.1080/14017430600868567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kofuji K, et al. Antioxidant Activity of b-Glucan. ISRN Pharm. 2012;2012:125864. doi: 10.5402/2012/125864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yokoyama WH, et al. Effect of Barley β-Glucan in Durum Wheat Pasta on Human Glycemic Response. Cereal Chem. 1997;74:293–296. doi: 10.1094/CCHEM.1997.74.3.293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roubille F, et al. Delayed postconditioning in the mouse heart in vivo. Circulation. 2011;124:1330–1336. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.031864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu Y, Liu B, Zweier JL, He G. Formation of hydrogen peroxide and reduction of peroxynitrite via dismutation of superoxide at reperfusion enhances myocardial blood flow and oxygen consumption in postischemic mouse heart. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008;327:402–410. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.142372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.von Harsdorf R, Li PF, Dietz R. Signaling pathways in reactive oxygen species-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Circulation. 1999;99:2934–2941. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.99.22.2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang P, et al. Regenerative repair of Pifithrin-α in cerebral ischemia via VEGF dependent manner. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:26295. doi: 10.1038/srep26295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song, Y.M. et al. Metformin Restores Parkin-Mediated Mitophagy, Suppressed by Cytosolic p53. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, pii: E122; doi:10.3390/ijms17010122 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Banai S, et al. Upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression induced by myocardial ischaemia: implications for coronary angiogenesis. Cardiovasc. Res. 1994;28:1176–1179. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.8.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawata H, et al. Ischemic preconditioning upregulates vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA expression and neovascularization via nuclear translocation of protein kinase C epsilon in the rat ischemic myocardium. Circ. Res. 2001;88:696–704. doi: 10.1161/hh0701.088842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo Z, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1997;64:993–998. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(97)00715-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zentilin L, et al. Cardiomyocyte VEGFR-1 activation by VEGF-B induces compensatory hypertrophy and preserves cardiac function after myocardial infarction. FASEB J. 2010;24:1467–1478. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-143180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giusti II, et al. High doses of vascular endothelial growth factor 165 safely, but transiently, improve myocardial perfusion in no-option ischemic disease. Hum. Gene Ther. Methods. 2013;24:298–306. doi: 10.1089/hgtb.2012.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamashita N, et al. Induction of manganese superoxide dismutase in rat cardiac myocytes increases tolerance to hypoxia 24 hours after preconditioning. J. Clin. Invest. 1994;94:2193–2199. doi: 10.1172/JCI117580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bourdon I, et al. Postprandial lipid, glucose, insulin, and cholecystokinin responses in men fed barley pasta enriched with beta-glucan. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999;69:55–63. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aoe S, et al. Effects of high β-glucan barley on visceral fat obesity in Japanese individuals: A randomized, double-blind study. Nutrition. 2017;42:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schneeman BO. Dietary fiber and gastrointestinal function. Nutr. Rev. 1987;45:129–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1987.tb06343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruiz-Meana M, García-Dorado D. Translational cardiovascular medicine (II). Pathophysiology of ischemia-reperfusion injury: new therapeutic options for acute myocardial infarction. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2009;62:199–209. doi: 10.1016/S0300-8932(09)70162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ikeda Y, et al. Blocking effect of anti-Dectin-1 antibodies on the anti-tumoractivity of 1,3-beta-glucan and the binding of Dectin-1 to 1,3-beta-glucan. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2007;30:1384–1389. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shimizu I, et al. Vascular rarefaction mediates whitening of brown fat in obesity. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124:2099–2112. doi: 10.1172/JCI71643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun K, et al. Dichotomous effects of VEGF-A on adipose tissue dysfunction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:5874–5879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200447109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elias I, et al. Adipose tissue overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor protects against diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2012;61:1801–1813. doi: 10.2337/db11-0832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen Z, et al. Overexpression of MnSOD protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in transgenic mice. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1998;30:2281–2289. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang L, et al. Resveratrol attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor B. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016;101:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim CH, Cho YS, Chun YS, Park JW, Kim MS. Early expression of myocardial HIF-1alpha in response to mechanical stresses: regulation by stretch-activated channels and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling pathway. Circ. Res. 2002;90:E25–33. doi: 10.1161/hh0202.104923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keränen MA, et al. Cardiomyocyte-targeted HIF-1alpha gene therapy inhibits cardiomyocyte apoptosis and cardiac allograft vasculopathy in the rat. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:1058–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Milano G, et al. Impact of the phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase signaling pathway on the cardioprotection induced by intermittent hypoxia. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Diao J, et al. Rosmarinic Acid suppressed high glucose-induced apoptosis in H9c2 cells by ameliorating the mitochondrial function and activating STAT3. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016;477:1024–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Negoro S, et al. Activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 protects cardiomyocytes from hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced oxidative stress through the upregulation of manganese superoxide dismutase. Circulation. 2001;104:979–981. doi: 10.1161/hc3401.095947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Osugi T, et al. Cardiac-specific activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 promotes vascular formation in the heart. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;77:6676–6681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108246200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abid MR, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated induction of manganese superoxide dismutase occurs through redox-dependent regulation of forkhead and IkappaB/NF-kappaB. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:44030–44038. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408285200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mak TW, Hauck L, Grothe D, Billia F. p53 regulates the cardiac transcriptome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:2331–2336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1621436114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Farhang Ghahremani M, et al. p53 promotes VEGF expression and angio-genesis in the absence of an intact p21-Rb pathway. Cell Death. Differ. 2013;20:888–897. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lim DY, Park JH. Induction of p53 contributes to apoptosis of HCT-116 human colon cancer cells induced by the dietary compound fisetin. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver. Physiol. 2009;296:G1060–1068. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90490.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moyzis AG, Sadoshima J, Gustafsson ÅB. Mending a broken heart: the role of mitophagy in cardioprotection. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2015;308:H183–192. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00708.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Darios F, et al. Parkin prevents mitochondrial swelling and cytochrome c release in mitochondria-dependent cell death. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:517–526. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lowe EP, et al. Human vascular endothelial cells express pattern recognition receptors for fungal glucans which stimulates nuclear factor kappaB activation and interleukin 8 production. Winner of the Best Paper Award from the Gold Medal Forum. Am. Surg. 2002;68:508–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu ML, et al. Investigation of beta-glucans binding to human/mouse dectin-1 and associated immunomodulatory effects on two monocyte/macrophage cell lines. Biotechnol. Prog. 2010;26:1391–1399. doi: 10.1002/btpr.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nural-Guvener HF, et al. HDAC class I inhibitor, Mocetinostat, reverses cardiac fibrosis in heart failure and diminishes CD90 + cardiac myofibroblast activation. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2014;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hasson SA, et al . Chemogenomic profiling of endogenous PARK2 expression using a genome-edited coincidence reporter. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015;10:1188–1197. doi: 10.1021/cb5010417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sionov RV, Haupt Y. The cellular response to p53: the decision between life and death. Oncogene. 1999;18:6145–6157. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hoshino A, et al. Cytosolic p53 inhibits Parkin-mediated mitophagy and promotes mitochondrial dysfunction in the mouse heart. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2308. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hecker PA, et al. Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency increases redox stress and moderately accelerates the development of heart failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 2013;6:118–126. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.969576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kusmic C, et al. Improved myocardial perfusion in chronic diabetic mice by the up-regulation of pLKB1 and AMPK signaling. J. Cell. Biochem. 2010;109:1033–1044. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Michael LH, et al. Myocardial ischemia and reperfusion: a murine model. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;269:H2147–2154. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.6.H2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stypmann J, et al. Age and gender related reference values for transthoracic Doppler-echocardiography in the anesthetized CD1 mouse. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2006;22:353–362. doi: 10.1007/s10554-005-9052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mukhopadhyay P, et al. Role of superoxide, nitric oxide, and peroxynitrite in doxorubicin-induced cell death in vivo and in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009;296:H1466–1483. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00795.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Skyschally A, et al. Across-Species Transfer of Protection by Remote Ischemic Preconditioning With Species-Specific Myocardial Signal Transduction by Reperfusion Injury Salvage Kinase and Survival Activating Factor Enhancement Pathways. Circ. Res. 2015;117:279–288. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.306878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Viotti J, et al. Glioma tumor grade correlates with parkin depletion in mutant p53-linked tumors and results from loss of function of p53 transcriptional activity. Oncogene. 2014;33:1764–1775. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Leychenko A, Konorev E, Jijiwa M, Matter ML. Stretch-induced hypertrophy activates NFkB-mediated VEGF secretion in adult cardiomyocytes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Prescimone T, et al. Apoptotic transcriptional profile remains activated in late remodeled left ventricle after myocardial infarction in swine infarcted hearts with preserved ejection fraction. Pharmacol. Res. 2013;70:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lafargue A, et al. Ionizing radiation induces long-term senescence in endothelial cells through mitochondrial respiratory complex II dysfunction and superoxide generation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017;108:750–759. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dushpanova A, et al. Gene silencing of endothelial von Willebrand Factor attenuates angiotensin II-induced endothelin-1 expression in porcine aortic endothelial cells. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:30048. doi: 10.1038/srep30048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.