Abstract

Significance: Successful matching of cardiac metabolism to perfusion is accomplished primarily through vasodilation of the coronary resistance arterioles, but the mechanism that achieves this effect changes significantly as aging progresses and involves the contribution of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Recent Advances: A matricellular protein, thrombospondin-1 (Thbs-1), has been shown to be a prolific contributor to the production and modulation of ROS in large conductance vessels and in the peripheral circulation. Recently, the presence of physiologically relevant circulating Thbs-1 levels was proven to also disrupt vasodilation to nitric oxide (NO) in coronary arterioles from aged animals, negatively impacting coronary blood flow reserve.

Critical Issues: This review seeks to reconcile how ROS can be successfully utilized as a substrate to mediate vasoreactivity in the coronary microcirculation as “normal” aging progresses, but will also examine how Thbs-1-induced ROS production leads to dysfunctional perfusion and eventual ischemia and why this is more of a concern in advancing age.

Future Directions: Current therapies that may effectively disrupt Thbs-1 and its receptor CD47 in the vascular wall and areas for future exploration will be discussed. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 27, 785–801.

Keywords: : blood flow, cardiac, reactive oxygen species, microvessel, age, CD47

Introduction

Coronary blood flow (BF) is unique compared to other tissues in the body due to the high oxygen extraction rate during baseline or resting conditions, near 70%, leaving a limited ability to increase oxygen extraction during higher levels of myocardial metabolism. If a coronary vascular network is restricted in its ability to carry more BF when stimulated (89, 90), the distal cardiac tissue it supplies can become hypoxic immediately. In a general sense, blood is delivered to the section of the circulation with very high pressures in very stiff tubes and exits in very low-pressure conditions in highly distensible tubes. The primary purpose of the resistance vessels and microcirculation in any vascular bed is to diffuse the blood pressure, deliver and exchange oxygen-rich blood, and carry away metabolites. The sheer area that the small resistance vessels cover in the myocardium warrants particular attention as a means to influence minute-to-minute oxygen exchange and impact BF distribution. This perfusion fine-tuning is accomplished primarily through vasodilation of the coronary resistance arterioles, but the mechanism that achieves this effect changes significantly as cardiac metabolism increases, as aging occurs, and as comorbidities arise.

Not surprisingly, advancing age is associated with the increased generation and presence of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in nearly all tissues. Specific to this review, more attention has recently been given to the role of a particular matricellular protein, thrombospondin-1 (Thbs-1), in the production and modulation of ROS in large vessels and peripheral networks. This review will reconcile how ROS can be successfully utilized during increased metabolic demand as a substrate to mediate vasoreactivity in the coronary microcirculation, and how this signaling changes as “normal” aging progresses, but will also discuss how Thbs-1-induced ROS can lead to dysfunctional perfusion and eventual ischemia in cardiac tissue. Finally, current therapies that may effectively disrupt Thbs-1 signaling in the vascular wall and areas for future exploration will be examined.

Free Radicals and Coronary Perfusion in Health and Disease

Myocardial perfusion and cardiac output

The successful connection between heart muscle metabolism and coronary BF is the most important factor for adequate oxygen delivery to the heart tissue (113, 129). Identifying the mechanisms that couple myocardial metabolism and coronary BF has been an objective of coronary physiology research for over five decades. Vasodilation as a response to increased shear stress is an endothelium-dependent process and is responsible for properly regulating coronary BF and maintaining necessary cardiac flow (41). The majority of vasodilation occurs across the resistance arteries and arterioles, and the distribution of blood volume depends on vascular resistance and amount of BF (21). Vascular resistance is determined by diameter and length of the vessel and the viscosity of the blood. Those resistance vessels (<150 μm in diameter) are in charge of distributing up to 70% of coronary vascular resistance and blood pressure (21, 108) primarily through changes in vessel diameter (since length of vessel and viscosity of the blood remain relatively constant).

These changes in vessel diameter are accomplished by signaling between vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and endothelial cells (ECs) (106, 107). ROS are recognized as secondary messengers in many cellular processes between VSMCs and ECs. They are derived from various sources in the vascular wall and are involved in the regulation of redox-sensitive physiological processes such as vasodilation and/or vasoconstriction (15, 125, 131). ROS involvement is critical in the physiological regulation of arterial BF, especially regulation of coronary BF.

Mechanisms of coronary vasodilation

The primary purpose of the microcirculation in a vascular bed is to dampen arterial blood pressures, deliver oxygen-rich blood in close proximity to the cells, and carry away metabolites. Sufficient dilation of the coronary arteries in response to increased workload is a critical mechanism to eliminate vascular wall injury and ischemia/infarction in the heart muscle. Metabolic activity of the myocardial tissue regulates coronary vascular resistance (108), and there are numerous metabolic factors that may contribute to this event, including adenosine and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Adenosine may contribute to modulating vascular resistance in conditions of low BF or extreme cardiac demand, but has been shown to not play a role in minute-to-minute matching of coronary BF to cardiac demand (108). Instead, a feedforward regulatory mechanism has been proposed to regulate coronary BF, through which a metabolite is continually released in response to periods when oxygen demand exceeds delivery, resulting in vasodilation. In this feedforward system, levels of released metabolites would decrease once sufficient BF is achieved (108, 129). H2O2 serves as a feedforward link between metabolism and BF in the heart (Fig. 1A) (129).

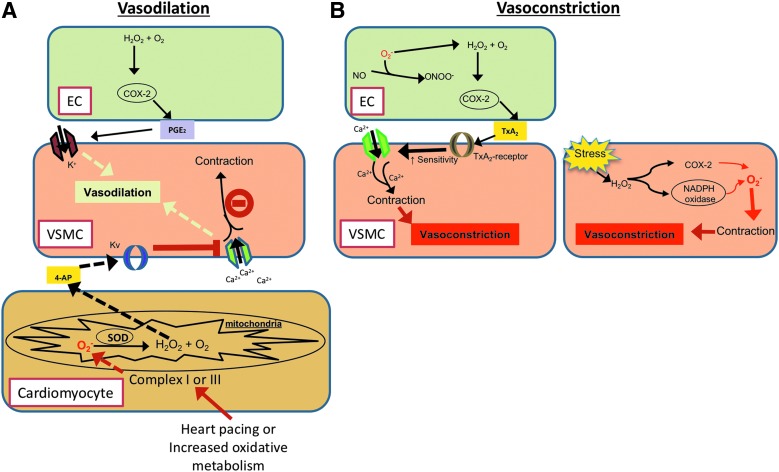

FIG. 1.

Schematic depicting redox-mediated vasoreactivity effects in the myocardium. (A) Redox-mediated cardiomyocyte-dependent vasodilation: Superoxide (O2•−) is produced in proportion to cardiac metabolism by mitochondrial electron transport in cardiomyocytes. Dismutation of O2•− by SOD forms easily diffusible vascular vasodilator metabolite, H2O2, which diffuses to VSMCs and increases activity of 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) sensitivity in Kv channels. Kv channels inhibit Ca2+ influx into the VSMC, which prevents contraction and allows for VSMC relaxation. Endothelium-dependent vasodilation is also mediated by PGE2, which is stimulated by H2O2-induced COX-2 production in ECs. (B) Endothelial-dependent vasoconstriction (left): O2•− formed in ECs are converted into H2O2, which elicits COX-2 dependent release of thromboxane-A2 (TxA2). Thromboxane receptors increase Ca2+ sensitivity into VSMC, leading to vasoconstriction. Endothelial-independent vasoconstriction (right): increased oxidative stress increases H2O2 production in VSMC, which can stimulate either COX-2 or NADPH oxidases leading to O2•−-mediated vasoconstriction. COX, cyclooxygenase; ECs, endothelial cells; NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; SOD, superoxide dismutase; VSMCs, vascular smooth muscle cells.

During oxidative cardiac metabolism, the cardiomyocyte mitochondria produce ROS, such as superoxide (O2•−), converted to H2O2 by the superoxide scavenger superoxide dismutase (SOD), and the concentration is proportionate to myocardial oxygen consumption (75, 115, 129). Being easily diffusible is a key factor of H2O2 as a coronary metabolic dilator, since it is produced in cardiomyocytes and links the coronary tone to myocardial metabolism (115, 128). H2O2 causes dilation by redox-dependent mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAP kinase) p38-mediated oxidation of intracellular thiols, accordingly, coronary metabolic dilation appears to be mediated by redox-dependent signaling (Fig. 1A) (115, 128). H2O2 directly activates redox- and 4-aminopyridine-sensitive voltage-gated K+ channels (Kv channels) in vascular smooth muscle and causes vasodilation (Fig. 1A) (125, 126). Therefore, Kv channels act as critical modulators of coronary BF by sensing and responding to metabolic signals from the cardiomyocytes (50, 113, 129). Summarily, the production of H2O2 from the dismutation of O2•−, formed during mitochondrial electron transport, is vital in the coupling between increased oxygen metabolism and BF in the heart (115, 128, 129), and is produced in sufficient amounts to be vasoactive (115, 128, 129).

Endothelium-dependent H2O2 induces vasodilation through cyclooxygenase (COX)-mediated release of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). H2O2 can also cause smooth muscle hyperpolarization and lead to vasodilation through opening of calcium-activated potassium channels (Fig. 1A) (153, 164, 168). Another mechanism by which H2O2 influences vasodilation is by acting directly on VSMC in rat (75, 115, 129), dog (125), and human (104) coronary arteries, thereby bypassing EC signaling. Regardless, H2O2 has all the requirements of being an effective metabolic dilator: a short half-life in cells (48), it is vasoactive (12, 99), it rapidly reacts with free thiol groups and is metabolized rapidly by catalase (35), and the main characteristic of H2O2 is that it is membrane permeable and diffusible (Fig. 1A) (48).

The endothelium also contributes to the modulation of vascular tone through the release of vasoactive compounds such as nitric oxide (NO), prostacyclin, endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors, and vasoconstrictors under varying physiological and pathophysiological conditions. In the coronary microcirculation, numerous animal and clinical studies have revealed the specific importance of NO in controlling and regulating vascular tone in the resistance vasculature (90, 130, 146). Endothelium-dependent generation of NO occurs via the enzyme NO synthase (NOS), which catalyzes NO from l-arginine and the cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), and is released constantly during baseline conditions in small coronary vessels (82). However, NO-mediated dilation is susceptible to the insult of various stressors, such as circulating oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL), inflammation, and presence of cardiovascular disease (56, 83). For example, during myocardial ischemia (MI), enhanced O2•− production reduces l-arginine bioavailability, which is a substrate required of NO synthesis, and leads to endothelial dysfunction in coronary arterioles (55). Interestingly, during stress, vasodilation action of H2O2 appears to compensate for the impaired NO-mediated dilation and protects the heart from ischemic injury (162). Summarily, both redox-sensitive vasodilation through H2O2 and endothelial-dependent NO signaling help to ensure adequate myocardial BF during baseline conditions and when cardiac demand increases in the heart, and both serve to counter the effects of coronary vasoconstrictors.

ROS-induced vasoconstriction

While studies have clearly shown a role of oxygen species and H2O2 in the pacing-induced metabolic coronary vasodilation (125, 129, 163), other groups have demonstrated that H2O2 also has an endothelium-dependent vasoconstrictor effect (84, 132). The eventual vasoreactive effect (dilation or constriction) of H2O2 depends on the arterial size and is also coupled to various intracellular signaling pathways such as COX and thromboxane A2 (TxA2) in ECs (7, 120, 132). Generally, the bigger the artery, the more the vasoconstrictive effect by H2O2, suggesting that H2O2 causes vasoconstriction in proximal segments of coronary arteries but dilation in the terminal end of the microcirculation (132). H2O2-induced vasoconstriction is mediated through intracellular sources of COX and TxA2 in VSMC and EC, which stimulate MAP and Pho kinase-mediated voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels in VSMC (7, 120, 160). Under stress conditions, H2O2 induces TxA2 production in the coronary arteries, enhancing COX-mediated vasoconstriction coupled to Ca2+ entry through L-type channels (Fig. 1B) (40, 45, 46, 120, 132).

ROS, like H2O2, have been shown to contribute to the vascular tone dysfunction in distal coronary vessels by enhancing vasoconstriction and promoting endothelial dysfunction during hypertension and metabolic syndrome (46, 47). Increased oxidative stress, such as an overabundance of O2•−, can augment production of H2O2 leading to enhanced vasoconstriction during hypertension (Fig. 1B) (45, 46). Vascular effects of H2O2 are complex, and the mechanisms of H2O2-induced vasoconstriction can differ if the endothelium is intact versus the presence of endothelial dysfunction. Thakali et al. and Yang et al. have shown physiologically relevant dose-dependent H2O2-induced constriction in rat aortas (152, 165). However, the presence of a stronger contractile effect of H2O2 observed on artery segments after removal of the endothelium suggests that the maximum contractile responses of the vessels to H2O2 are endothelium independent (152).

Advanced aging increases H2O2 generation

Aging contributes to the occurrence of cardiovascular diseases, including stroke, MI, arrhythmias, and cardiac failure (150). Structural and functional changes in the vascular system and ventricles occur with normal aging, however, the presence of cardiovascular risk factors such as atherosclerosis, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome accelerates these changes (91, 136). Age-related left ventricular dysfunction is associated with an increase in arterial vascular stiffness due to deterioration of elastic components within the arterial wall (58). Chronological aging in aorta is characterized by an increase of intima-media thickness (94), calcification of the smooth muscle cells of aorta (150), aortic dilation (134), and stiffness of the vascular wall (91). An increase in vascular stiffness increases left ventricular work demand, and over time this can lead to an imbalance between the metabolic demand of cardiac tissue and the oxygen-rich blood supply (78). In addition, there is a decrease in the ability of a vascular network to respond to a stimulus and augment BF with aging (Fig. 2) (138), which also leads to an imbalance in supply/demand, decreased overall cardiac function, and contributes to regional ischemia (6, 154). Furthermore, abnormal circulation (such as in obstructive atherosclerosis) upstream of the microcirculation can also contribute to the clinical spectrum of MI as it contributes to microvascular perfusion deficits (14, 26).

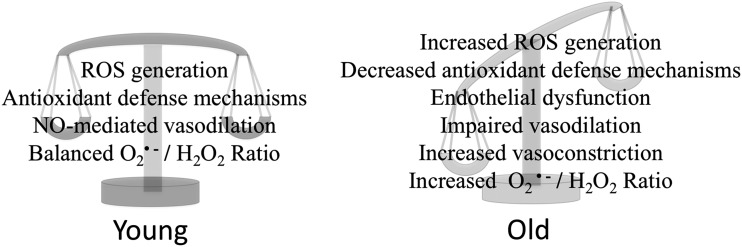

FIG. 2.

The age-related balance between redox signaling and endogenous buffering. In healthy, young myocardium, a balance between deleterious insults and protective systems exists. With advancing age, however, this balance is progressively lowered, which leads to endothelial dysfunction and deranged vascular reactivity.

Aging is a major risk factor to an impaired coronary circulation (96). The progressive changes of the functional behavior of ECs and SMCs occurring from youth to old age have been studied (106). ROS have been implicated in the progression of age-related EC dysfunction, and multiple studies have shown that these age-related deficits are related to altered ROS endothelial signaling mechanisms; specifically, decreased NO signaling and production (31, 34, 77, 90) and ineffective buffering of O2•− (76). In fact, one of the most prominent age-dependent alterations is the gradual loss of NO-dependent vasodilation accompanied by an increase in ROS production due to higher nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidases (Nox) (31), which leads to the formation of O2•−. As a result, NO becomes increasingly inactivated in advancing age through overproduction of O2•− (31, 148), which scavenges available NO by forming the highly reactive oxidant peroxynitrate (ONOO−). Indeed, ONOO− formation has been shown to substantially increase in advancing age and contributes to vasomotor dysfunction (148). A major source of intracellular ROS during advanced aging is O2•− produced by mitochondria leading to increased H2O2 generation in rats (20, 84).

Excess mitochondrial H2O2 release has been shown to occur as soon as young adulthood (106, 107). Until middle age, the heart could have sufficient antioxidant defenses to ameliorate the overabundant production of ROS such as H2O2 (106), however, this defense mechanism progressively deteriorates into old age (106). Excess mitochondrial ROS production that is unresolved plays a role in the development of pathophysiological conditions, such as metabolic syndrome, but has also been proposed as a signal for accelerated senescence (16). Maintaining the balance of O2•−/H2O2 is imperative for successful flow-induced vasodilation (Fig. 2) (77). Disruption of this balance, whether due to increased production of O2•− or age-induced changes in endogenous scavenging system, leads to an impairment of coronary arteriolar response to increased flow (77), possibly leading to ischemia. At the same time, old cardiomyocytes produce excess angiotensin, which is sufficient to induce coronary arteriolar constriction and contribute to decreased perfusion (24, 96).

Whether or not simply normalizing the vascular wall ROS imbalance is sufficient to reverse age-related vascular dysfunction is not clear. Certainly, this approach has improved functional parameters such as flow-mediated dilation in isolated vessels (41, 93). Whether such interventions improve overall cardiac perfusion is yet to be demonstrated. Importantly, this maladaptation in ROS utilization further compromises responses to ischemic or reperfusion injury in which oxidative stress is increased (169), thereby leading to more advanced vascular dysfunction and heart disease. However, not all ROS produced in the vascular wall are detrimental to vascular reactivity, as alluded to above.

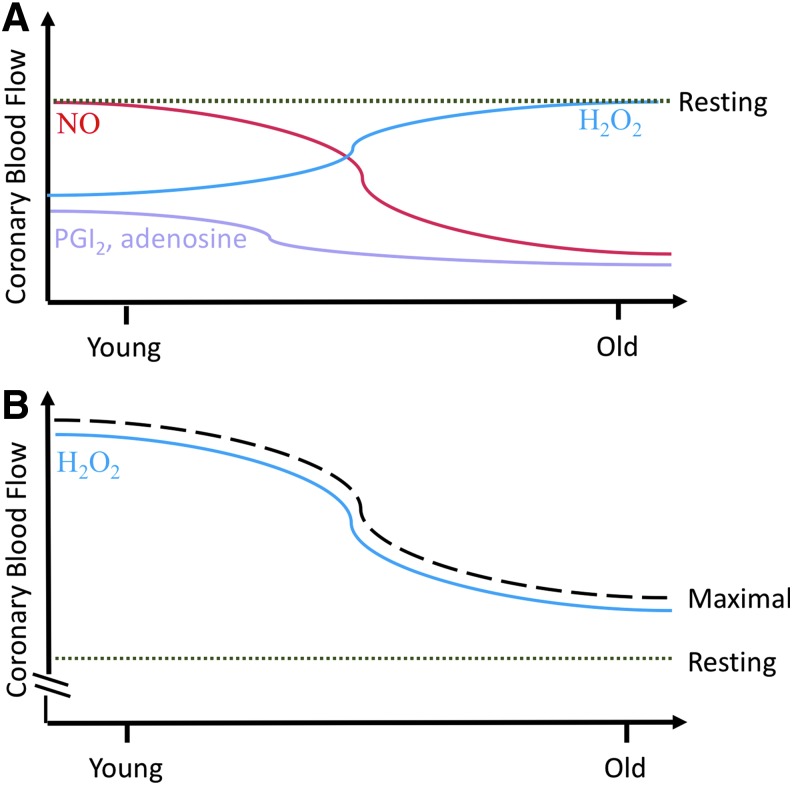

With chronic loss of NO in disease states, compensatory mechanisms can sometimes preserve coronary microcirculatory BF by shifting NO-mediated dilation to H2O2-mediated dilation (22, 49). It has been shown that in healthy adults, regardless of age, H2O2 is normally utilized as a mediator of flow-dependent vasodilation during acute exercise (37). Based on this and that aged arterioles depend more on H2O2 (vs. NO) to mediate basal coronary vascular tone (77), it appears that vascular aging is associated with a limited ability to buffer ROS substrate on a chronic level. To summarize, mitochondrial ROS generated from cardiomyocytes regulate coronary vascular tone to elicit vasodilation, allowing for the matching between increased cardiac demand and coronary BF. However, the confounding influence from metabolites and endothelial-derived factors, such as O2•− and H2O2 balance, NO, and age-related decreases in antioxidant defense signaling, can ultimately impact and decide coronary microvascular perfusion (Figs. 2 and 3).

FIG. 3.

Factors contributing to resting and maximal coronary blood flow change with advancing age. (A) Coronary blood flow during the rest or baseline conditions is influenced by metabolic and endothelial factors, such as NO, H2O2, adenosine, and prostaglandins. With advancing age, NO contribution to mediating blood flow (red line) decreases while H2O2 contribution increases (blue line). Conversely, a small contribution to resting coronary blood flow comes from prostaglandins and adenosine at a young age, and this decreases prior to middle age (purple line). The level of resting blood flow (green dotted line) throughout the myocardium remains relatively the same throughout the life span due to compensatory structural and functional changes in the ventricle and circulation. (B) Even though H2O2 contribution to maintain resting blood flow (green dotted line) is increasing with age, increased H2O2 and other unregulated ROS in the vascular wall lead to impaired vasodilation and coronary vasoconstriction, which lowers maximal blood flow (black dashed line) that can be achieved in the aged population. H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; NO, nitric oxide; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Thrombospondin-1 Discovery

Thrombospondin-1 (Thbs-1) is a matricellular glycoprotein that can exert a variety of different effects on angiogenesis, cell proliferation, chemotaxis, adhesion, migration, and survival. It has been nearly four decades since Thbs-1 was properly named to emphasize its secretion in response to thrombin, rather than as a result of direct proteolysis (87). Sequencing experiments in 1986 by Lawler and Hynes confirmed earlier reports of the estimated size of the three chains, each around ∼133–145 kDa, establishing that total molecular weight of Thbs-1, including carbohydrates, is closer to 450 kDa (86). Subsequently, Thbs-1 is a huge, multidomain structure that allows for multiple cell-based interactions through a variety of cell surface receptors, such as integrins, CD36, CD47, heparin sulfate proteoglycans, LDL-related protein 1, and very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) receptor (19, 109).

Thbs-1 is stored preformed in platelet alpha granules and is primarily released from platelets on activation, but can also be secreted from multiple primary cells in response to stress, including VSMC, EC, epithelial, fibroblasts, and immune cells (including macrophages and T cells) (85, 122). In 1982, a study by Mosher et al. found that confluent human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) secrete thrombospondin in vitro (105). Further investigation found that the levels of intracellular thrombospondin were similar between HUVECs and saphenous vein cells, but there existed a fivefold difference in the ability to secrete more thrombospondin in cells derived from HUVECs (61). This suggests that the level of circulating Thbs-1 found in the blood at one particular moment depends heavily on the individualized response to stress from a specific cell type. Typically, picomolar amounts of Thbs-1 normally circulate in the plasma (∼40 μg/L) of healthy, young adults (13), and there is a linear correlation between higher circulating Thbs-1 levels and disease states, such as peripheral artery disease, where plasma Thbs-1 levels rise to ∼500 μg/L according to one study (140).

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a potent angiogenic factor, has been shown to be directly and indirectly influenced by the presence of Thbs-1 to inhibit angiogenesis. Early work from Gupta et al. described how Thbs-1 accomplished angiogenic inhibition via displacement of VEGF (164), the human molecular weight VEGF, from the EC membrane and also by directly binding to VEGF (54, 164). Further studies expounded on this relationship between Thbs-1 and VEGF (52, 79), describing how the cell surface receptor, CD47, is constitutively associated with VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2) (79). Ligation of CD47 by Thbs-1 inhibits this association and prevents VEGFR2 phosphorylation and downstream Akt signaling (79). Summarily, the bulk of thrombospondin-related research to date has been associated with these antiangiogenic properties until the year 2005, when a seminal pair of studies established that the level of NO was a critical influencer on the actions of Thbs-1 in angiogenesis (118) and also played a large role in influencing vascular cell signaling (71). Consequential for the purpose of this review, the latter study showed that at the lowest doses of NO, the cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) pathway, critical for proper vascular relaxation, was inactivated by Thbs-1 and also prevented proliferation, chemotaxis, and adhesion. However, it was the unexpected discovery that Thbs-1 had such a consistently high potency for inhibiting NO responses (71) that is particularly relevant in this review, given that NO is essential to vessel structural integrity and endothelium-dependent relaxation (71, 72).

Thrombospondin-1 Signaling and ROS Dynamics

NO and endothelial NOS pathway

The past decade has brought attention to Thbs-1 and its ability to impact vascular homeostasis through the disruption of NO signaling, and both CD36 and CD47 cell surface receptors have been found to be involved in this process (70, 71). CD36, a membrane glycoprotein receptor, was discovered first in 1987 as a negative regulator of adhesion when bound by Thbs-1 (8), but also participates in other activities such as angiogenesis, immunity, metabolism, and behavior (32, 74, 139). CD36 can indirectly affect endothelial NOS (eNOS) activity as well, at least, in part, through the inhibition of fatty acid translocase (FAT) activity (66). Specifically, FAT activity of the CD36 receptor allows for the uptake of myristic acid into ECs and promotes NO/cGMP/cGK signaling via activation of Src family kinases and signaling target Fyn (66). However, Thbs-1 at 1–10 nM potently inhibits the FAT activity of CD36, which can lead to a decrease in cGMP signaling (66).

CD47, first established as an integrin-associated protein for Thbs-1 in 1996 (43), is notable for promoting self-recognition between macrophages and nonmacrophages, thereby acting as a “don't eat me” signal, which leads to reduced or inhibited inflammation (114). While both CD36 and CD47 receptors are vital in carrying out many downstream signaling effects of Thbs-1, it was a 2006 study that found Thbs-1 inhibition on NO signaling persisted even in CD36-null cells, but not CD47-null cells, revealing the absolute requirement of CD47 in hindering NO (70). CD47 can also bind to other thrombospondins (Thbs-2 and Thbs-4), but the interaction is relatively weak compared to high affinity of Thbs-1 (62). And despite similar antiangiogenic activities of both Thbs-1 and Thbs-2, the selectivity of Thbs-1 to CD47 suggests a more potent inhibition of the NO/cGMP pathway in vascular cells compared to other thrombospondins (62).

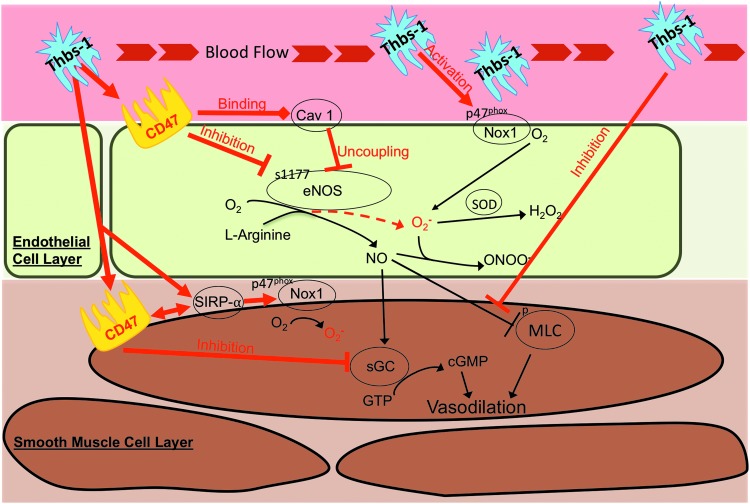

Figure 4 illustrates the variety of ways Thbs-1 can alter intracellular and intercellular signaling in the vascular wall. Thbs-1 impairs NO-stimulated cGMP accumulation by CD47-dependent inhibition of the downstream target soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) in vitro (71, 73), but upstream eNOS activity could be influenced by Thbs-1 and could also contribute to inhibition of NO. This was evidenced by Bauer et al., who found that Thbs-1/CD47 signaling inhibits eNOS activation in ECs and that Thbs-1-null cells exhibit a greater eNOS activity (10), suggesting that basal eNOS activity is dependent on the presence or absence of Thbs-1. Thbs-1 inhibits eNOS activity through a variety of mechanisms, including modulating Ca2+ transients, inhibiting phosphorylation at serine1177, and limiting association with Hsp90 (10), effectively restricting production of the diffusible vasodilator NO. Furthermore, Thbs-1 antagonizes NO signaling through a disruption in VSMC cytoskeletal and contractile responses via inhibiting NO-driven dephosphorylation of myosin light chain (MLC), resulting in vasoconstriction (64). Moreover, Thbs-1 has also been shown to uncouple eNOS by activating CD47 to constitutively associate with caveolin-1 (11), which results in significant generation of O2•− in the vascular wall due to resultant hyperactivity of eNOS (31, 98, 142) (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Thrombospondin-1 (Thbs-1) effects on vasoreactivity in endothelial and VSMCs. Red lines and arrows indicate deleterious effects of Thbs-1, which may lead to microvascular vasoconstriction and coronary perfusion deficits. Pathways downstream of CD47 are implicated in the exacerbated response to Thbs-1 observed in coronary arterioles from aged rats. Downstream effects of CD47 include activation of NADPH oxidase (Nox1), uncoupling of eNOS, inhibition of sGC, activation of SIRPα, and promoting MLC phosphorylation. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase. MLC, myosin light chain; sGC, soluble guanylyl cyclase.

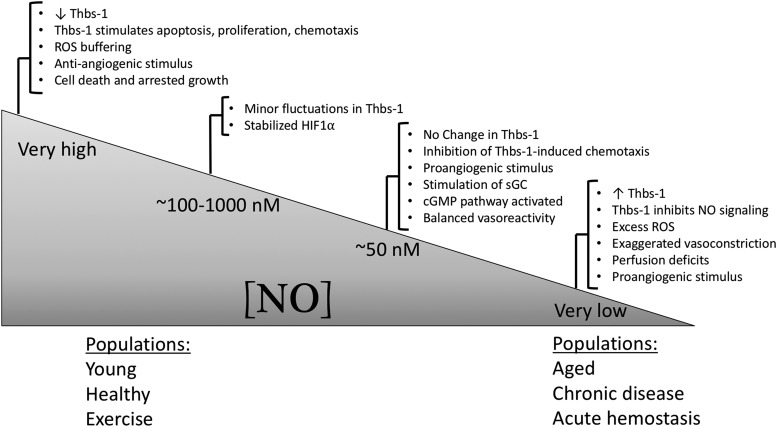

Conversely, levels of NO can regulate some aspects of Thbs-1 release and signaling. For example, basal levels of NO production in HUVECs were insufficient to modulate Thbs-1 expression, but higher levels of NO significantly downregulated Thbs-1 and resulted in a more Thbs-1-induced apoptosis, proliferation, and chemotaxis rather than negative vascular reactivity effects (118). Very low levels of NO, typically associated with the aged population or in chronic diseases, result in increased Thbs-1 expression and deranged perfusion due to inhibition of NO/cGMP signaling (63) (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Concentration-dependent control of Thbs-1-mediated angiogenic and vascular signaling by NO. At intermediate (physiological) up to very high levels of NO, Thbs-1 does not have a large vasoreactive role, but stimulates apoptosis, proliferation, and chemotaxis. These levels of NO correspond to those typically reported in young, healthy, and/or exercise-trained populations. Furthermore, balanced vasodilation and vasoconstriction in tissues and ROS buffering allow for efficient blood flow and perfusion. Conversely, very low concentrations of NO are typically reported in advanced age, chronic diseases, and during acute hemostasis, and correspond to Thbs-1-induced impairment of NO signaling (through inhibition of sGC), exaggerated vasoconstriction, excess ROS, and resultant perfusion deficits. Figure adapted from references (63, 71, 118, 122, 137).

NADPH oxidase pathway

To limit NO-mediated perfusion in a tissue, one can influence eNOS in such a way as to decrease the amount of NO that is produced, antagonize the NO-dependent MLC machinery (discussed in “NO and endothelial NOS pathway” section), or by the production of free radicals that effectively act to sequester NO away from VSMC. The latter is perhaps the most detrimental method that Thbs-1 can exert on the vascular wall, namely via generation of the specific ROS product and NO scavenger, O2•−. In total, there are a limited number of studies regarding the effect of any matricellular protein on ROS production in any cells or tissue (133, 161), much less with Thbs-1. However, in 2012, Csanyi et al. reported that Thbs-1 acted as a prolific and robust regulator of tissue ROS through signaling events, including Nox organizer subunit p47phox and subsequent Nox1 activation (29) (Fig. 4).

The Nox1 enzyme complex produces O2•− levels that diminish the normal relaxation effect of NO and is a major source of ROS in the vascular wall under physiological and pathophysiological conditions, thereby making it an essential mediator of vascular disease (28, 116). In terms of hierarchy of deleterious ROS subtypes, O2•− is the most pathological ROS impacting the vasculature, not only because it rapidly scavenges NO as discussed previously (60) but because it also produces H2O2 and ONOO− and stimulates additional free radical production (117). In general, upregulation of Nox subunits and increased O2•− production by vascular Nox isoforms are common in cardiovascular disease.

Of the major isoforms, Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4 play distinct and important roles in the vasculature due to their different vascular expressions and subcellular locations and have been described as the “master oxidases” (33, 53, 155). The endothelial injury and reduced NO signaling occurring in the early stages of vascular disease are largely mediated by Nox2 oxidase-derived O2•− (17, 36), but a relationship between Nox2 and Thbs-1 has not been identified. Interestingly, Nox4 is an isoform that is selectively upregulated by hypoxia and produces H2O2 rather than O2•− (95), but Thbs-1 does not stimulate H2O2 under normal in vitro conditions (29). However, in a hypoxic environment, Thbs-1 upregulates Nox4 expression and the subsequent H2O2 generation in human VSMC (51).

Overall, these studies indicate that O2•− production is occurring primarily via Thbs-1/CD47/Nox1 signaling in the vessel wall, but the contribution of non-CD47 signaling pathways is also capable of generating ROS. Recently, Yao et al. discovered two other pathways Thbs-1 can stimulate production of O2•− through Nox1 activation, both of which include the phosphorylation of signal regulatory protein-α (SIRPα), a cell surface receptor expressed on VSMC (167). The results recognized that Thbs-1 elicits ROS via CD47 to activate SIRPα, or by direct phosphorylation of SIRPα itself (167) (Fig. 4), thus identifying SIRPα as a new physiologically important activator of Nox-derived O2•− in vascular cells.

Circulating Levels of Thbs-1

Thbs-1 normally circulates in young, healthy adults in the picomolar plasma range (∼40 μg/L, or 0.26 nM) (13), but the amount of circulating Thbs-1 found in human vascular disease [2.2 nM (102)] results in increased O2•− generation in endothelial and VSMC in a CD47-dependent and CD47-independent manner (Fig. 4) (29). Peripheral arterial disease patients showed a significant upregulation of Thbs-1 plasma levels (∼3.3 nM) compared to age-matched controls (1.6 nM, ∼57 ± 7.2 years), supporting the hypothesis that aging alone results in an increase in circulating Thbs-1 levels (140). It is important to note that at concentrations found in healthy individuals (∼0.22 nM), O2•− levels were unchanged (29). Other studies have shown that plasma Thbs-1 levels increase following inhalation of inflammatory particulates (5), and in conditions with dysregulated BF, such as ischemia/reperfusion (IR) injury (124), atherosclerosis (119), pulmonary hypertension (11), and sickle cell anemia (112). As an obvious example of systemic dysregulated BF, there is a significant correlation between diabetes and elevated serum Thbs-1 levels in humans (100). In fact, a recent study of 164 patients has suggested that circulating Thbs-1 levels may serve as a novel biomarker of metabolic syndrome, as levels are positively correlated with the quantitative traits of obesity and diabetes (100). Furthermore, Thbs-1 is also markedly upregulated in large-vessel walls in experimental and clinical peripheral vascular disease (87, 145) and in small vessels from patients with pulmonary hypertension (123). Thus, how the increased presence of O2•− from Thbs-1 influences vascular reactivity and tissue perfusion in a diseased or aged population becomes an important area of research.

Thbs-1 and its vasoreactive contribution in the vessel wall

Large conductance vessels

The majority of the studies investigating how Thbs-1 signaling alters vasoreactivity and overall blood pressure have utilized large conductance vessels (such as segments of the aorta and pulmonary artery). Recently, Aragon et al. demonstrated that inhalation of multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT), an inflammatory nanomaterial, resulted in a significant elevation in serum Thbs-1 in wild-type (WT) mice (5). Aortic vasodilation is diminished when incubated in serum from mice exposed to MWCNT, but this effect is not observed in CD36−/− aortic rings (4). In the 2010 study by Bauer et al., Thbs-1 null vessels (thoracic aorta) demonstrate enhanced acetylcholine-induced vasodilation compared to wild-type vessels, and could be reversed with exogenous Thbs-1 (10). Notably, the authors also demonstrated that CD47-null arteries were resistant to Thbs-1-mediated inhibition of eNOS-stimulated vasodilation (10). As one would expect, Thbs-1 also significantly decreased vasodilation to the NO donor, sodium nitroprusside (SNP) in thoracic aorta from mice, but this could be prevented via silencing Nox1 (29). A 2017 study by Rogers et al. extended those findings into pulmonary artery segments from humans, where Thbs-1 decreased dilation to SNP, but αCD47 pretreatment limited this impairment (123). Using endothelial-free aortic segments, Thbs-1 can rapidly stimulate the production of O2•−, but this could be abrogated through a CD47 blocking antibody (29).

Not surprisingly, Thbs-1- and CD47-null mice exhibit a greater hypotensive response to systemic administration of NO-donor agents compared to WT mice, along with increased cardiac output and ejection fraction (69). Another study found that incubation with an SIRPα antibody that blocks Thbs-1 activation of SIRPα was able to completely reverse Thbs-1-induced impairment of relaxation to NO and reduce O2•− in aortic rings, and increase renal BF following IR injury (167). On the other side of vasoreactivity, Thbs-1 can also influence vasoconstriction, as exogenous Thbs-1 has been shown to increase phenylephrine-mediated vasoconstriction in aortic segments (10) and can lead to an increase in mean arterial blood pressure in WT mice (10). Recently, pulmonary artery segments collected from older patients (∼57 years old) without chronic disease were incubated with Thbs-1 (2.2 nM), which resulted in exaggerated vasoconstriction to the potent coronary vasoconstrictor, endothelin-1 compared to untreated vessels (123).

Microvasculature and the coronary microcirculation

While large vessels are useful for relative ease of isolation and denudation, consecutive segments for multiple vessel preparations, and the amount of tissue available for other molecular biology applications, the primary responsibility of perfusion in a given tissue occurs in the smaller arteries and arterioles. To date, only a few studies have specifically examined the vasoactive effect of Thbs-1 signaling on microvessels (under 200 μm in diameter), but they give a glimpse into how much is yet to be explored in the periphery and coronary microvasculature on this pathway. Using real-time laser Doppler to observe superficial perfusion in a rat, Csanyi et al. showed that intravenous Thbs-1 (2.2 nM) acutely decreased recovery of hind limb BF following IR, but this could be prevented by CD47 blocking antibody injection before injury (29).

Another study utilizing intravital microscopy of the gluteus maximus muscle demonstrated that endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent concentration/response curves were both decreased by 39% and 47%, respectively, in WT mice following pulmonary exposure to MWCNT, and this exposure resulted in a more than fivefold increase in Thbs-1 protein content in skeletal muscle when compared to sham-control exposed mice (97). When Thbs-1 was deleted (Thbs-1 knocked out [KO] mice), there were no changes in vasodilatory capability of the microcirculation after exposure, suggesting that Thbs-1 may act as a key mediator in the peripheral microvascular dysfunction that follows nanomaterial exposure or a similar inflammatory event. In addition, this study found that the absence of Thbs-1 (Thbs-1 KO mice) afforded protection to the microvasculature, as evidenced by reduced leukocyte adhesion and rolling in third-order venules compared to WT exposed mice (97), a process that has been shown to create significant amounts of ROS (143). This highlights another mechanism by which Thbs-1 and ROS may interfere with NO signaling in an endothelium-independent manner in a given tissue.

In 2016, Nevitt et al. first reported that Thbs-1/CD47 signaling alters vasoreactivity to NO in the heart, using isolated coronary arterioles from young (3–6 months) or old (24 months) Fischer-344 rats. Exogenous Thbs-1 (2.2 nM) significantly decreased relaxation to NO in resistance arterioles from rats of advanced age, while arterioles from young rats treated with Thbs-1 did not show altered NO-responsiveness (111). Furthermore, suppression of NO-dependent vasodilation (via concentration/response curves) and production of O2•− (via dihydroergotamine fluorescence intensity) in the presence of Thbs-1 were both attenuated by pretreatment with a CD47 blocking antibody in coronary arterioles of old rats. Interestingly, pretreatment with ROS scavengers tempol and catalase before Thbs-1 incubation did not fully restore the reduced responsiveness to NO in the arterioles from old rats, supporting the conclusion that Thbs-1 elicits microvascular dysfunction via multiple mechanisms other than primarily through the generation of ROS. In the coronary microcirculation, this study clearly demonstrated that by interrupting CD47 signaling, circulating levels of Thbs-1 are unable to suppress NO-dependent vasodilation in the coronary microvasculature in advanced age (111). Overall, both the large- and small-vessel studies support the likelihood that circulating levels of Thbs-1 contribute to vascular pathology and reactivity.

Aging and Thbs-1

The study by Nevitt et al. (111) provides initial insight into an understanding of the mechanism by which Thbs-1 potentially contributes to coronary microvascular dysfunction in advanced age, but much remains unsettled. Initially, one should consider the local environment (tissue of interest) and the aged phenotype when discussing the full impact of the presence of circulating Thbs-1. In mice, Thbs-1 immunostaining was significantly increased (>3.5-fold) in the myocardium of aged (30 months) compared to juvenile (2 months) (18). This age-related upregulation of Thbs-1 is in congruence with other tissues and cells in small rodents, such as skin (121), adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (39), and stromal vascular fraction cells (2). However, the recent study by Nevitt et al., reported that plasma, heart, and coronary arteriolar levels of Thbs-1 did not differ statistically based on age in rats (3 months vs. 24 months old) (111). One potential reason for the disparate results by Nevitt et al. includes the use of female Fischer-344 rats compared to male mice and rats used in other studies, suggesting this difference may be related to sex or species. As an aside, the phase of estrus cycle in young hormonally active females was not shown to influence the circulating levels of Thbs-1 (111).

Given the growing body of literature showing that Thbs-1 suppresses NO signaling in general (10, 103, 166), it is somewhat surprising that coronary arterioles from young rats did not also show impaired NO-dependent vasodilation in the study by Nevitt et al. (111). A possibility is that healthy coronary arterioles are protected from the action of Thbs-1 through mechanisms such as adequate oxidative stress buffering, and that this protection is lost in advancing age. Decreased antioxidant defenses such as SOD, responsible for converting O2•− into a less harmful ROS, are known contributors to the development of vascular dysfunction in aging (1, 27, 30, 31, 34). While Thbs-1 has not been shown to directly alter SOD activity in VSMC (29), levels of SOD have been shown to be decreased in the myocardium of aged mice (18), Yet, treating vessels with the antioxidants tempol and catalase to reduce O2•− and H2O2 levels, respectively, only minimally rescued vasodilation in arterioles from aged rats (111). These results support the theory that Thbs-1 suppresses NO-dependent vasodilation in aging coronary arterioles through a variety of mechanisms, not all are O2•− dependent (Fig. 4). This might include direct inhibition of sGC (103), which has previously been noted to decrease in expression and activity in advanced age (81, 127, 149).

Aging, Thbs-1, and the response to stress

In consideration of the local environment and Thbs-1 content, it is also important to note the response to stress in aging. For example, baseline Thbs-1 expression in adipose tissue and stromal vascular fraction (SVF, a subset of cells from adipose tissue) was not altered with advancing age in mice, but showed significant upregulation in Thbs-1 gene expression following systemic inflammation activation via lipopolysaccharide injection (144). Along those lines, another study investigated both the resting platelet proteome and the platelet releasate (activated release) from children (mean age 4.3 years ±1.6) or adults (mean age 35.1 years ±9.5), and found that Thbs-1 protein was significantly downregulated in children in baseline and following platelet activation (25). The authors suggested that the decreased levels of Thbs-1 from platelets during these conditions may contribute to the relative state of thromboprotection (less thrombotic or hemorrhagic events) in children compared to adults. This supports prior studies which have shown that younger age is associated with protection against IR injury in animal models and in humans (156, 159). Furthermore, Isenberg et al. demonstrated how Thbs-1 limited ischemic tissue survival in advancing age in mice, but the absence of CD47 or Thbs-1 allowed senescent mice (aged 14–18 months) to maintain perfusion in the hind limb, normalizing BF to that observed in young mice (65).

Chronic stress that comes by way of additional pathologies such as coronary artery disease (CAD), diabetes mellitus (DM), obesity, and hypertension, likely only intensify the deleterious effects of Thbs-1 in advanced age. In a study of 374 patients with suspected CAD, Choi et al. reported that plasma Thbs-1 levels were significantly increased in those patients with both CAD and DM, compared with CAD or DM alone, despite similar ages (23). This is supported by another study which found that adipose-derived stromal cells collected from patients with CAD and/or DM exhibited increased Thbs-1 mRNA compared to age-matched controls (38). Functionally, the ischemic pathology-related increase in Thbs-1 was correlated with a sharp decline in angiogenic activity of these cells in vitro (38). Therefore, while the majority of this review focuses on the relationship between aging, Thbs-1-induced ROS, and vascular reactivity, it is important to keep in mind the likely exacerbation of this relationship when other chronic stressors are present.

Anti-CD47 Therapies and Coronary Influence

Inhibition of CD47 in the periphery

Attempting to control Thbs-1 levels via antisense strategies may be ineffective because some cells, particularly platelets, contain stores of preformed Thbs-1 (141) and also because the stimulus to secrete Thbs-1 protein from cells and tissue is unclear or may be different in a particular end organ. A variety of therapeutics targeting CD47 signaling are under clinical development (preclinical or Phase I), including conventional antibodies, recombinant polypeptides, and bispecific molecules. Although CD47 is ubiquitously expressed on all cells throughout the body, preclinical studies suggest that anti-CD47 antibodies are well tolerated with anemia being a primary side effect (92). This is probably due to the fact that CD47 actually serves an age marker on red blood cells (RBC), and older RBC may be more susceptible to phagocytosis (3, 80, 158). Peptides that mimic the CD47 binding domain of Thbs-1 have exhibited efficacy as antiangiogenic therapies (57), and humanized antibodies against CD47 have shown promise for cancer treatment in a preclinical setting and have progressed on to clinical trials because of their demonstrated efficacy in vitro and in vivo (92, 158). In 2017, Weiskopf detailed a list of four studies utilizing CD47-targeting therapeutics currently in preclinical development and nine different anti-CD47 antibodies already into Phase I and II trials (158), all in the spotlight of cancer immunotherapy. Interestingly, clinically used biomaterials are also being developed with immunomodulation to CD47 as an approach to enhance the bioavailability of therapeutic agents and longevity of medical devices, effectively creating immune-evasive artificial surfaces (151).

Whatever the circulating concentration of Thbs-1 may be, blocking CD47 activation (via multiple corroborating methods) has been shown to completely nullify Thbs-1-stimulated Nox1 activation and O2•− production in aortic segments (29). Although there still may be some direct stimulation on SIRPα by Thbs-1 that results in ROS generation (167), this non-CD47 pathway has not been fully investigated to determine its relative contribution to overall ROS generation in the vascular wall. CD47 signaling redundantly controls NO bioavailability and downstream effector pathways, enabling it to control both intracellular and intercellular signaling. Subsequently, targeting of CD47 to decrease pathological ROS production and accordingly treat age-related vascular dysfunction appears to be the most strategic and effective approach. In fact, when CD47 is absent from cells seeded in implanted Matrigel plugs, in vivo neovascularization potential (or the ability to grow new blood vessels from those seeded cells) is greatly improved compared to WT cells, and could be enhanced further if either cell type were implanted into a CD47-null environment (CD47 KO mouse) (44). These data support applications for therapy in peripheral vascular disease and critical limb ischemia, for example, where vessel rarefication is a major hurdle to revascularization (88). Treatment with an αCD47 antibody also prevents the development of pulmonary arterial hypertension in animal models (11), increases skin graft healing (68), and preserves BF and tissue survival in ischemia and/or following IR injury in skin flaps (65, 67). Targeting CD47 is also effective at promoting BF and protecting at-risk tissue after reperfusion has been reestablished, which enables a broader clinical applicability, especially in instances of delayed presentation to healthcare providers (101).

Aging populations in Western societies exhibit many diseases where acute and chronic loss of BF plays a contributing role. If a Thbs-1/CD47-related therapy is developed and proven to augment microvascular function, it could have widespread applications for almost all vascular diseases. Related to the aging variable, CD47 deficiency in EC increases the percentage of cells in the S phase and also lowers senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity in vitro, which suggests a critical role for CD47 in the regulation of cell cycle progression and cellular senescence (44). EC senescence has been reported to contribute to the pathogenesis of age-associated vascular diseases (110); therefore, efforts to restore and/or rejuvenate senescent cells are currently a major trending area for regenerative medicine and therapeutic applications in the aged population. Also, inhibiting CD47 activation does not benefit perfusion in an older age group merely, as Rogers et al. utilized a CD47 blocking antibody in WT mice to show increased cutaneous BF via laser Doppler in both young and old mice (121).

CD47 therapies to improve coronary perfusion

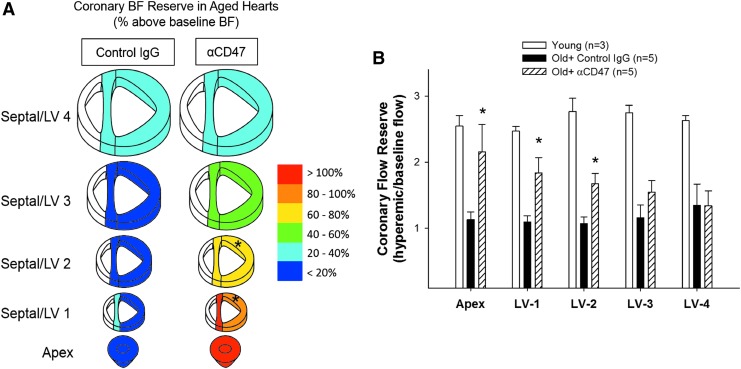

Identifying therapeutic targets to reverse coronary microvascular dysfunction in aging remains a primary goal to help decrease the risk for CVD, prevent potential ischemic events, and improve recovery from MI. Unfortunately, effective therapeutic approaches to improve cardiovascular dynamics and coronary perfusion in the aging population remain elusive. Elevated circulating levels of Thbs-1 in aged humans may limit the effectiveness of therapies designed to enhance NO levels or target downstream effectors, such as sGC or cGMP (141). Therefore, targeting CD47 remains an optimistic approach. In the study by Nevitt et al., both suppression of NO-dependent vasodilation and production of O2•− in the presence of Thbs-1 were completely reversed by treatment with a CD47 blocking antibody in coronary arterioles of old rats (111). The beneficial effect of αCD47 treatment was also confirmed in vivo. Aged rats treated with αCD47 for 45 min before microsphere injection showed improved coronary perfusion during increased cardiac demand, achieved via dobutamine administration. Coronary blood flow reserve (CFR), a measure of the vasoactive capability of the microcirculation, was significantly increased in distal sections of the heart supplied by the left anterior descending artery, which is responsible for generating much of the contractile force of the LV (Fig. 6A) (111). Decreased CFR, associated with aging and CVD, limits the ability of the heart to respond to increased demand (42, 135) and is depicted graphically in Figure 6B, where a young group was added for reference. Therefore, blocking of CD47 appears to be a promising therapeutic strategy for increasing CFR and addressing age-related coronary microvascular dysfunction. Currently, CD47 antagonists utilized in clinical trials are being evaluated for their potential efficacies, outcomes, and arising concerns specific to cancer immunotherapy (59, 92). Hopefully, these trials will also reveal potential vascular benefits, potentially bringing CD47 blockade as a therapy to reverse age-related coronary microvascular dysfunction one step closer to reality.

FIG. 6.

CD47 blockade improves coronary blood flow reserve in advanced age. (A) Coronary blood flow reserve (CFR) was calculated from measurements of blood flow at baseline and with dobutamine stimulation. Hearts from control IgG-treated (n = 5) and αCD47-treated (n = 5) 24-month-old female Fischer-344 rats were sectioned to allow for analysis of regional perfusion changes. Color for each section corresponds to percent increase in blood flow with dobutamine stimulation over baseline. *Indicates significant difference between αCD47 and control IgG sections. Figure from Nevitt et al. (111). (B) CFR was calculated from measurements of hyperemic (post-dobutamine) and baseline blood flow (hyperemic/baseline flow). Hearts from young rats (female Fischer-344 rats aged 3–6 months, n = 3) are included as reference, along with old rats treated for 45 min with control IgG (n = 5) or with αCD47 (n = 5). *Indicates significant difference between αCD47 and old control IgG. Graph adapted from data in Nevitt et al. (111) and from unpublished data (young rats).

Conclusions

Future areas of study

With our aging population, the physiological functions of all Thbs-1 interactions in the myocardium need to be explored. As it stands, the study by Nevitt et al. remains the sole investigation into how the Thbs-1/CD47 signaling affects coronary microvessels in an aged model. Below are research areas that may contribute significantly to our understanding of the relationship between aging, Thbs-1, ROS, and coronary perfusion.

To date, there have been very few sex-specific comparisons of the Thbs-1/CD47 signaling pathway and expression as age progresses, making this an understudied research area. Straface et al. demonstrated that in patients with metabolic syndrome, there was a significant decrease in CD47 in RBC from men compared to women, but no gender difference was found in cells from age-matched healthy donors (147). Considering the relative risk protection to cardiovascular-related events that women experience up until menopause compared to age-matched men (9), the contribution of Thbs-1 and CD47 signaling during this time could be an impactful study.

Isenberg et al. reported that Thbs-2 and Thbs-4 are lower affinity ligands of CD47 compared to Thbs-1 (62), but these interactions have not been fully tested in vivo, nor in an aged model. Furthermore, the non-CD47-dependent signaling that allows for SIRPα to directly stimulate Nox1 was recently described in the past 4 years and has not been evaluated in the heart. It is possible that CD47 targeting antibodies might be most effective at restoring perfusion when coupled with an SIRPα blocking antibody (59). Finally, all Nox isoforms are major sources of ROS in vascular cells, but Nox4 is unique because it is constitutively active and stimulates the production of H2O2 (33). Yet, in in vitro conditions, Thbs-1 did not stimulate H2O2 production in VSMC (29). Interestingly, a recent study reported that Nox4 was significantly upregulated in the vascular walls of aged mice (16 months old vs. young group) and suggested that Nox4 is a mediator of CVD in aging (157). Further studies are needed to determine if Nox4 is contributing to ROS levels via Thbs-1 in the coronary microcirculation.

Reconciling ROS in aging—when is it good, when is it bad?

During oxidative cardiac metabolism, the cardiomyocyte mitochondria produce ROS, such as O2•−, which is then converted to H2O2 by SOD, and its concentration is proportionate to myocardial oxygen consumption. SOD activity in cardiomyocytes is able to fully convert O2•− to H2O2 in healthy hearts, but this does not happen during Thbs-1-induced generation of ROS. The influence of metabolites and endothelial-derived factors, such as O2•− and H2O2 balance, NO, and age-related decreases in antioxidant defense signaling, can ultimately impact and decide coronary microvascular perfusion. However, one of the most prominent age-dependent alterations in the development of microvascular dysfunction in the heart is the gradual loss of NO-dependent vasodilation accompanied by an increase in ROS production due to higher Nox and subsequent formation of O2•− (31). The age-related decrease in antioxidant defense mechanisms in older age and the increase in circulating Thbs-1 set the stage for ROS generation, leading to perfusion deficits in a highly metabolic tissue such as the heart. Increased Thbs-1 activity that occurs in advancing age and disease may tip the scale that balances antioxidant stress and defense toward unattainable ROS sequestration and buffering.

While non-CD47 pathways exist, it appears as though the activation of CD47 by Thbs-1 remains the pathway by which overt vascular dysfunction is set into motion. Regardless of the mechanism, age-dependent response to Thbs-1 may be a direct contributor to the development of a negative vascular phenotype in aging, with consequences for cardiovascular health. Studies suggest that even without increases in circulating levels of Thbs-1 or CD47 concentration, Thbs-1 can elicit a significant vascular impairment in aging via enhanced CD47 activity and ROS generation, which may lead to coronary ischemia. Blockade of CD47 attenuates the effects of Thbs-1 and, therefore, represents an attractive therapeutic target for age-related cardiovascular dysfunction that deserves further attention.

Abbreviations Used

- 4-AP

4-aminopyridine

- BF

blood flow

- BH4

tetrahydrobiopterin

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CFR

coronary blood flow reserve

- cGMP

cyclic guanosine monophosphate

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- ECs

endothelial cells

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- FAT

fatty acid translocase

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- HUVECs

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- IR

ischemia/reperfusion

- KO

knocked out

- Kv channels

voltage-gated K+ channels

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- MAP kinase

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MWCNT

multiwalled carbon nanotube

- MI

myocardial ischemia

- MLC

myosin light chain

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- Nox

NADPH oxidases

- O2•−

superoxide

- ONOO−

peroxynitrate

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- RBC

red blood cell

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- sGC

soluble guanylate cyclase

- SIRPα

signal regulatory protein α

- SNP

sodium nitroprusside

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- SVF

stromal vascular fraction

- Thbs-1

thrombospondin-1

- TxA2

thromboxane A2

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VLDL

very-low-density lipoprotein

- VSMCs

vascular smooth muscle cells

- WT

wild type

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by RO1 AG053585 from NIA (A.J.L.), Jewish Heritage Fund for Excellence (A.J.L.), and the Gheens Foundation (A.J.L.).

References

- 1.Adler A, Messina E, Sherman B, Wang Z, Huang H, Linke A, and Hintze TH. NAD(P)H oxidase-generated superoxide anion accounts for reduced control of myocardial O2 consumption by NO in old Fischer 344 rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H1015–H1022, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aird AL, Nevitt CD, Christian K, Williams SK, Hoying JB, and LeBlanc AJ. Adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction cells isolated from old animals exhibit reduced capacity to support the formation of microvascular networks. Exp Gerontol 63C: 18–26, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anniss AM. and Sparrow RL. Expression of CD47 (integrin-associated protein) decreases on red blood cells during storage. Transfus Apher Sci 27: 233–238, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aragon M, Erdely A, Bishop L, Salmen R, Weaver J, Liu J, Hall P, Eye T, Kodali V, Zeidler-Erdely P, Stafflinger JE, Ottens AK, and Campen MJ. MMP-9-Dependent serum-borne bioactivity caused by multiwalled carbon nanotube exposure induces vascular dysfunction via the CD36 scavenger receptor. Toxicol Sci 150: 488–498, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aragon MJ, Topper L, Tyler CR, Sanchez B, Zychowski K, Young T, Herbert G, Hall P, Erdely A, Eye T, Bishop L, Saunders SA, Muldoon PP, Ottens AK, and Campen MJ. Serum-borne bioactivity caused by pulmonary multiwalled carbon nanotubes induces neuroinflammation via blood-brain barrier impairment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114: E1968–E1976, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arbab-Zadeh A, Dijk E, Prasad A, Fu Q, Torres P, Zhang R, Thomas JD, Palmer D, and Levine BD. Effect of aging and physical activity on left ventricular compliance. Circulation 110: 1799–1805, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ardanaz N. and Pagano PJ. Hydrogen peroxide as a paracrine vascular mediator: regulation and signaling leading to dysfunction. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 231: 237–251, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asch AS, Barnwell J, Silverstein RL, and Nachman RL. Isolation of the thrombospondin membrane receptor. J Clin Invest 79: 1054–1061, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bairey Merz CN, Shaw LJ, Reis SE, Bittner V, Kelsey SF, Olson M, Johnson BD, Pepine CJ, Mankad S, Sharaf BL, Rogers WJ, Pohost GM, Lerman A, Quyyumi AA, and Sopko G. Insights from the NHLBI-sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Study: part II: gender differences in presentation, diagnosis, and outcome with regard to gender-based pathophysiology of atherosclerosis and macrovascular and microvascular coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 47: S21–S29, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauer EM, Qin Y, Miller TW, Bandle RW, Csanyi G, Pagano PJ, Bauer PM, Schnermann J, Roberts DD, and Isenberg JS. Thrombospondin-1 supports blood pressure by limiting eNOS activation and endothelial-dependent vasorelaxation. Cardiovasc Res 88: 471–481, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauer PM, Bauer EM, Rogers NM, Yao M, Feijoo-Cuaresma M, Pilewski JM, Champion HC, Zuckerbraun BS, Calzada MJ, and Isenberg JS. Activated CD47 promotes pulmonary arterial hypertension through targeting caveolin-1. Cardiovasc Res 93: 682–693, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beny JL. and von der Weid PY. Hydrogen peroxide: an endogenous smooth muscle cell hyperpolarizing factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 176: 378–384, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergseth G, Lappegard KT, Videm V, and Mollnes TE. A novel enzyme immunoassay for plasma thrombospondin. Comparison with beta-thromboglobulin as platelet activation marker in vitro and in vivo. Thromb Res 99: 41–50, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beyer AM. and Gutterman DD. Regulation of the human coronary microcirculation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 52: 814–821, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bogeski I, Kappl R, Kummerow C, Gulaboski R, Hoth M, and Niemeyer BA. Redox regulation of calcium ion channels: chemical and physiological aspects. Cell Calcium 50: 407–423, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonomini F, Rodella LF, and Rezzani R. Metabolic syndrome, aging and involvement of oxidative stress. Aging Dis 6: 109–120, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brandes RP. and Schroder K. Composition and functions of vascular nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases. Trends Cardiovasc Med 18: 15–19, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cai H, Yuan Z, Fei Q, and Zhao J. Investigation of thrombospondin-1 and transforming growth factor-beta expression in the heart of aging mice. Exp Ther Med 3: 433–436, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlson CB, Lawler J, and Mosher DF. Structures of thrombospondins. Cell Mol Life Sci 65: 672–686, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Q, Vazquez EJ, Moghaddas S, Hoppel CL, and Lesnefsky EJ. Production of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria: central role of complex III. J Biol Chem 278: 36027–36031, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chilian WM, Eastham CL, and Marcus ML. Microvascular distribution of coronary vascular resistance in beating left ventricle. Am J Physiol 251: H779–H788, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chlopicki S, Kozlovski VI, Lorkowska B, Drelicharz L, and Gebska A. Compensation of endothelium-dependent responses in coronary circulation of eNOS-deficient mice. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 46: 115–123, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi KY, Kim DB, Kim MJ, Kwon BJ, Chang SY, Jang SW, Cho EJ, Rho TH, and Kim JH. Higher plasma thrombospondin-1 levels in patients with coronary artery disease and diabetes mellitus. Korean Circ J 42: 100–106, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cingolani HE, Villa-Abrille MC, Cornelli M, Nolly A, Ennis IL, Garciarena C, Suburo AM, Torbidoni V, Correa MV, Camilionde Hurtado MC, and Aiello EA. The positive inotropic effect of angiotensin II: role of endothelin-1 and reactive oxygen species. Hypertension 47: 727–734, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cini C, Yip C, Attard C, Karlaftis V, Monagle P, Linden M, and Ignjatovic V. Differences in the resting platelet proteome and platelet releasate between healthy children and adults. J Proteomics 123: 78–88, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coelho-Filho OR, Rickers C, Kwong RY, and Jerosch-Herold M. MR myocardial perfusion imaging. Radiology 266: 701–715, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collins AR, Lyon CJ, Xia X, Liu JZ, Tangirala RK, Yin F, Boyadjian R, Bikineyeva A, Pratico D, Harrison DG, and Hsueh WA. Age-accelerated atherosclerosis correlates with failure to upregulate antioxidant genes. Circ Res 104: e42–e54, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Csanyi G, Taylor WR, and Pagano PJ. NOX and inflammation in the vascular adventitia. Free Radic Biol Med 47: 1254–1266, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Csanyi G, Yao M, Rodriguez AI, Al Ghouleh I, Sharifi-Sanjani M, Frazziano G, Huang X, Kelley EE, Isenberg JS, and Pagano PJ. Thrombospondin-1 regulates blood flow via CD47 receptor-mediated activation of NADPH oxidase 1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32: 2966–2973, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Csiszar A, Labinskyy N, Zhao X, Hu F, Serpillon S, Huang Z, Ballabh P, Levy RJ, Hintze TH, Wolin MS, Austad SN, Podlutsky A, and Ungvari Z. Vascular superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production and oxidative stress resistance in two closely related rodent species with disparate longevity. Aging Cell 6: 783–797, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Edwards JG, Kaminski P, Wolin MS, Koller A, and Kaley G. Aging-induced phenotypic changes and oxidative stress impair coronary arteriolar function. Circ Res 90: 1159–1166, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dawson DW, Pearce SF, Zhong R, Silverstein RL, Frazier WA, and Bouck NP. CD36 mediates the In vitro inhibitory effects of thrombospondin-1 on endothelial cells. J Cell Biol 138: 707–717, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dikalov SI, Dikalova AE, Bikineyeva AT, Schmidt HH, Harrison DG, and Griendling KK. Distinct roles of Nox1 and Nox4 in basal and angiotensin II-stimulated superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production. Free Radic Biol Med 45: 1340–1351, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donato AJ, Eskurza I, Silver AE, Levy AS, Pierce GL, Gates PE, and Seals DR. Direct evidence of endothelial oxidative stress with aging in humans: relation to impaired endothelium-dependent dilation and upregulation of nuclear factor-kappaB. Circ Res 100: 1659–1666, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dringen R. and Hamprecht B. Involvement of glutathione peroxidase and catalase in the disposal of exogenous hydrogen peroxide by cultured astroglial cells. Brain Res 759: 67–75, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drummond GR, Selemidis S, Griendling KK, and Sobey CG. Combating oxidative stress in vascular disease: NADPH oxidases as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 10: 453–471, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Durand MJ, Dharmashankar K, Bian JT, Das E, Vidovich M, Gutterman DD, and Phillips SA. Acute exertion elicits a H2O2-dependent vasodilator mechanism in the microvasculature of exercise-trained but not sedentary adults. Hypertension 65: 140–145, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dzhoyashvili NA, Efimenko AY, Kochegura TN, Kalinina NI, Koptelova NV, Sukhareva OY, Shestakova MV, Akchurin RS, Tkachuk VA, and Parfyonova YV. Disturbed angiogenic activity of adipose-derived stromal cells obtained from patients with coronary artery disease and diabetes mellitus type 2. J Transl Med 12: 337, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Efimenko A, Starostina E, Kalinina N, and Stolzing A. Angiogenic properties of aged adipose derived mesenchymal stem cells after hypoxic conditioning. J Transl Med 9: 10, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Erdei N, Bagi Z, Edes I, Kaley G, and Koller A. H2O2 increases production of constrictor prostaglandins in smooth muscle leading to enhanced arteriolar tone in Type 2 diabetic mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H649–H656, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Freed JK, Beyer AM, LoGiudice JA, Hockenberry JC, and Gutterman DD. Ceramide changes the mediator of flow-induced vasodilation from nitric oxide to hydrogen peroxide in the human microcirculation. Circ Res 115: 525–532, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galderisi M, Rigo F, Gherardi S, Cortigiani L, Santoro C, Sicari R, and Picano E. The impact of aging and atherosclerotic risk factors on transthoracic coronary flow reserve in subjects with normal coronary angiography. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 10: 20, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao AG, Lindberg FP, Finn MB, Blystone SD, Brown EJ, and Frazier WA. Integrin-associated protein is a receptor for the C-terminal domain of thrombospondin. J Biol Chem 271: 21–24, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao Q, Chen K, Gao L, Zheng Y, and Yang YG. Thrombospondin-1 signaling through CD47 inhibits cell cycle progression and induces senescence in endothelial cells. Cell Death Dis 7: e2368, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gao YJ. and Lee RM. Hydrogen peroxide induces a greater contraction in mesenteric arteries of spontaneously hypertensive rats through thromboxane A(2) production. Br J Pharmacol 134: 1639–1646, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garcia-Redondo AB, Briones AM, Beltran AE, Alonso MJ, Simonsen U, and Salaices M. Hypertension increases contractile responses to hydrogen peroxide in resistance arteries through increased thromboxane A2, Ca2+, and superoxide anion levels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 328: 19–27, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garcia-Redondo AB, Briones AM, Martinez-Revelles S, Palao T, Vila L, Alonso MJ, and Salaices M. c-Src, ERK1/2 and Rho kinase mediate hydrogen peroxide-induced vascular contraction in hypertension: role of TXA2, NAD(P)H oxidase and mitochondria. J Hypertens 33: 77–87, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giorgio M, Trinei M, Migliaccio E, and Pelicci PG. Hydrogen peroxide: a metabolic by-product or a common mediator of ageing signals? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 722–728, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Godecke A. and Schrader J. Adaptive mechanisms of the cardiovascular system in transgenic mice—lessons from eNOS and myoglobin knockout mice. Basic Res Cardiol 95: 492–498, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goodwill AG, Noblet JN, Sassoon D, Fu L, Kassab GS, Schepers L, Herring BP, Rottgen TS, Tune JD, and Dick GM. Critical contribution of KV1 channels to the regulation of coronary blood flow. Basic Res Cardiol 111: 56, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Green DE, Kang BY, Murphy TC, and Hart CM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) regulates thrombospondin-1 and Nox4 expression in hypoxia-induced human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation. Pulm Circ 2: 483–491, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Greenaway J, Lawler J, Moorehead R, Bornstein P, Lamarre J, and Petrik J. Thrombospondin-1 inhibits VEGF levels in the ovary directly by binding and internalization via the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (LRP-1). J Cell Physiol 210: 807–818, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Griendling KK. Novel NAD(P)H oxidases in the cardiovascular system. Heart 90: 491–493, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gupta K, Gupta P, Wild R, Ramakrishnan S, and Hebbel RP. Binding and displacement of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) by thrombospondin: effect on human microvascular endothelial cell proliferation and angiogenesis. Angiogenesis 3: 147–158, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hein TW. and Kuo L. LDLs impair vasomotor function of the coronary microcirculation: role of superoxide anions. Circ Res 83: 404–414, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hein TW, Liao JC, and Kuo L. oxLDL specifically impairs endothelium-dependent, NO-mediated dilation of coronary arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H175–H183, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Henkin J. and Volpert OV. Therapies using anti-angiogenic peptide mimetics of thrombospondin-1. Expert Opin Ther Targets 15: 1369–1386, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hu Y, Li L, Shen L, and Gao H. The relationship between arterial wall stiffness and left ventricular dysfunction. Neth Heart J 21: 222–227, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang Y, Ma Y, Gao P, and Yao Z. Targeting CD47: the achievements and concerns of current studies on cancer immunotherapy. J Thorac Dis 9: E168–E174, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huie RE. and Padmaja S. The reaction of no with superoxide. Free Radic Res Commun 18: 195–199, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hunter NR, Dawes J, MacGregor IR, and Pepper DS. Quantitation by radioimmunoassay of thrombospondin synthesised and secreted by human endothelial cells. Thromb Haemost 52: 288–291, 1984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Isenberg JS, Annis DS, Pendrak ML, Ptaszynska M, Frazier WA, Mosher DF, and Roberts DD. Differential interactions of thrombospondin-1, −2, and −4 with CD47 and effects on cGMP signaling and ischemic injury responses. J Biol Chem 284: 1116–1125, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Isenberg JS, Frazier WA, and Roberts DD. Thrombospondin-1: a physiological regulator of nitric oxide signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci 65: 728–742, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Isenberg JS, Hyodo F, Matsumoto K, Romeo MJ, Abu-Asab M, Tsokos M, Kuppusamy P, Wink DA, Krishna MC, and Roberts DD. Thrombospondin-1 limits ischemic tissue survival by inhibiting nitric oxide-mediated vascular smooth muscle relaxation. Blood 109: 1945–1952, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Isenberg JS, Hyodo F, Pappan LK, Abu-Asab M, Tsokos M, Krishna MC, Frazier WA, and Roberts DD. Blocking thrombospondin-1/CD47 signaling alleviates deleterious effects of aging on tissue responses to ischemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 2582–2588, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Isenberg JS, Jia Y, Fukuyama J, Switzer CH, Wink DA, and Roberts DD. Thrombospondin-1 inhibits nitric oxide signaling via CD36 by inhibiting myristic acid uptake. J Biol Chem 282: 15404–15415, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Isenberg JS, Maxhimer JB, Powers P, Tsokos M, Frazier WA, and Roberts DD. Treatment of liver ischemia-reperfusion injury by limiting thrombospondin-1/CD47 signaling. Surgery 144: 752–761, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Isenberg JS, Pappan LK, Romeo MJ, Abu-Asab M, Tsokos M, Wink DA, Frazier WA, and Roberts DD. Blockade of thrombospondin-1-CD47 interactions prevents necrosis of full thickness skin grafts. Ann Surg 247: 180–190, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Isenberg JS, Qin Y, Maxhimer JB, Sipes JM, Despres D, Schnermann J, Frazier WA, and Roberts DD. Thrombospondin-1 and CD47 regulate blood pressure and cardiac responses to vasoactive stress. Matrix Biol 28: 110–119, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Isenberg JS, Ridnour LA, Dimitry J, Frazier WA, Wink DA, and Roberts DD. CD47 is necessary for inhibition of nitric oxide-stimulated vascular cell responses by thrombospondin-1. J Biol Chem 281: 26069–26080, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Isenberg JS, Ridnour LA, Perruccio EM, Espey MG, Wink DA, and Roberts DD. Thrombospondin-1 inhibits endothelial cell responses to nitric oxide in a cGMP-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 13141–13146, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Isenberg JS, Ridnour LA, Thomas DD, Wink DA, Roberts DD, and Espey MG. Guanylyl cyclase-dependent chemotaxis of endothelial cells in response to nitric oxide gradients. Free Radic Biol Med 40: 1028–1033, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Isenberg JS, Wink DA, and Roberts DD. Thrombospondin-1 antagonizes nitric oxide-stimulated vascular smooth muscle cell responses. Cardiovasc Res 71: 785–793, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jimenez B, Volpert OV, Crawford SE, Febbraio M, Silverstein RL, and Bouck N. Signals leading to apoptosis-dependent inhibition of neovascularization by thrombospondin-1. Nat Med 6: 41–48, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]