Abstract

Background: People with serious illness frequently rely on religion/spirituality to cope with their diagnosis, with potentially positive and negative consequences. Clergy are uniquely positioned to help patients consider medical decisions at or near the end of life within a religious/spiritual framework.

Objective: We aimed to examine clergy knowledge of end-of-life (EOL) care and beliefs about the role of faith in EOL decision making for patients with serious illness.

Design: Key informant interviews, focus groups, and survey.

Setting/Subjects: A purposive sample of 35 active clergy in five U.S. states as part of the National Clergy End-of-Life Project.

Measurement: We assessed participant knowledge of and desire for further education about EOL care. We transcribed interviews and focus groups for the purpose of qualitative analysis.

Results: Clergy had poor knowledge of EOL care; 75% desired more EOL training. Qualitative analysis revealed a theological framework for decision making in serious illness that balances seeking life and accepting death. Clergy viewed comfort-focused treatments as consistent with their faith traditions' views of a good death. They employed a moral framework to determine the appropriateness of EOL decisions, which weighs the impact of multiple factors and upholds the importance of God-given free will. They viewed EOL care choices to be the primary prerogative of patients and families. Clergy described ambivalence about and a passive approach to counseling congregants about decision making despite having defined beliefs regarding EOL care.

Conclusions: Poor knowledge of EOL care may lead clergy to passively enable congregants with serious illness to pursue potentially nonbeneficial treatments that are associated with increased suffering.

Keywords: : clergy, clinical decision making, palliative care, pastoral care, religion, serious illness, spirituality

Introduction

Religion and spirituality (R/S) play important roles in the lives of most Americans,1 and those with serious illness frequently rely on R/S to cope with their diagnosis and its implications.2–4 For example, measures of R/S and spiritual well-being are associated with improved quality of life for patients facing advanced illnesses5 and, among seriously ill patients, existential and spiritual questions are common.6–11 Accordingly, studies suggest that spiritual support provided by religious community leaders (clergy) to terminally ill cancer patients and their families influences end-of-life (EOL) decision making.12

Advanced cancer patients reporting high support from religious communities receive less hospice care and more aggressive medical interventions at the end of life.13,14 Data indicate that such intensive measures, aimed at prolonging life, may contribute to patient and caregiver suffering without meeting that aim.15,16 These findings contrast with findings that contemporary teachings from religious faith communities and leaders rarely uphold intensive hospital-based care as an ideal for dying.17,18 This raises the question of what clergy believe regarding EOL care and how they support and counsel their seriously ill congregants.

Patients' beliefs in miracles, the sacredness of life, and a spiritual call to endure suffering within illness may influence EOL treatment decisions.14,19–21 Clergy may be called upon to provide spiritual guidance related to these beliefs and their impact on decision making, but many report inadequate knowledge concerning EOL medical issues.17,22,23 Understanding clergy beliefs and perspectives on EOL decision making is a critical step in helping oncology and palliative care clinicians uphold religious patients' values and better engage faith communities as they support congregants at the end of life. In this study, we examine clergy knowledge of EOL care and beliefs about the role of faith in EOL decision making for patients with serious illness.

Methods

Sample

The National Clergy Project on End-of-Life Care is a National Cancer Institute-funded mixed methods study designed to examine the beliefs and practices of US clergy regarding spiritual care to congregants near the end of life.17,24 Our purposive sample of active clergy represented preidentified racial, educational, theological, and denominational categories hypothesized to be associated with more intensive utilization of interventions intended to prolong life at the end of life. The study oversampled Asian, black, and Hispanic Christian ministers to capture the perspectives of those from religious communities associated with high medical utilization at the end of life.13 We conducted key informant interviews (n = 14) and focus groups (n = 21) with participants in five U.S. states (California, Illinois, Massachusetts, New York, and Texas). Participants had no prior relationship to the researchers. All participants provided informed consent as per protocols approved by the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board.

Focus group and qualitative interviewing procedures

An interdisciplinary panel of oncology and palliative care clinicians, health services researchers, medical educators, and theologians developed a semistructured interview guide to explore clergy perspectives on EOL decision making (see Supplementary Data for questions; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/jpm). Specifically, clergy were asked to consider a congregant facing terminal cancer and respond to a variety of religiously motivating factors that may influence patients' decisions to pursue aggressive or comfort-focused care.

Between November 2013 and September 2014, MJB, JP, and TL conducted 2 focus groups and 14 individual interviews in English (n = 31), Spanish (n = 2), and Mandarin (n = 2). Participants received a $25 gift card for participation. Focus groups and key informant interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Spanish-language transcripts were translated into English for analysis.

Participants completed preinterview surveys assessing sociodemographic factors and a 9-item measure of medical knowledge concerning hospice/palliative care, intensive care, and pain management.

Qualitative analysis

We utilized multiple methods of triangulation to enhance and test validity and transferability, including the use of multiple data sources, and the use of multiple analysts from different genders and relevant professional backgrounds (nursing, medicine, sociology, theology), including those with formal training in qualitative methods (M.J.B. and J.S.).25 All authors independently analyzed all transcripts and identified themes and subthemes using an editing style of thematic analysis based on grounded theory.26 We derived a final coding scheme through a collaborative process of consensus building among all authors. Four authors (A.B., J.S., R.Q., and V.C.) applied the finalized codes to all transcripts using NVivo (v10, QSR International) and resolved coding discrepancies by consensus. All team members contributed to the article and graphical representations.

Results

Participant characteristics, knowledge, and attitudes toward end-of-life medical care

Table 1 provides participant demographic information on the clergy, who averaged 20 years of service. Half of clergy were non-white, greater than three quarters of participants were Protestant, and a majority identified themselves as theologically conservative.

Table 1.

Clergy Demographic Characteristics, n = 35

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 32 | 91.4 |

| Average years serving as clergy (n = 32a) | 20 years | |

| Geographical location | ||

| Northeast (Massachusetts and New York) | 11 | 31.4 |

| Southwest (Texas) | 11 | 31.4 |

| Midwest (Illinois) | 10 | 28.6 |

| West (California) | 3 | 8.6 |

| Race (n = 32) | ||

| White | 16 | 50.0 |

| Black | 14 | 43.7 |

| Asian | 2 | 6.3 |

| Ethnicity (n = 30) | ||

| Latino/Hispanic | 2 | 6.7 |

| Religious tradition (n = 35) | ||

| Protestantb | 27 | 77.1 |

| Roman Catholic | 4 | 11.4 |

| Eastern Orthodox | 1 | 2.9 |

| Jewish | 2 | 5.7 |

| Other (Center for Spiritual Living) | 1 | 2.9 |

| Theological orientation (n = 32) | ||

| Theologically conservativec | 21 | 65.6 |

| Theologically liberal | 11 | 34.4 |

| Educational level (n = 34) | ||

| Below Master's Degree | 6 | 17.7 |

| Master's Degree (e.g., MDiv) | 15 | 44.1 |

| Doctoral Degree | 13 | 38.2 |

Not all participants responded to every question.

Protestant clergy identified with the following Protestant denominations: Assemblies of God (2), Baptist (5), Congregational (4), Episcopalian (1), Methodist (3), Nondenominational (6), Presbyterian (1), and Seventh-Day Adventist (1). Four Protestant clergy did not disclose specific denominational information.

Clergy were categorized as theologically conservative if they agreed with the following statement: “My religious tradition's Holy Book is perfect because it is the Word of God.”

Clergy knowledge of hospice and palliative care was poor, as illustrated in Table 2. Over 40% did not understand the role of palliative care in addressing symptoms. Similarly, they overestimated the negative impact of using pain medications and underestimated the ability to address their side effects. Most (81%) overestimated the success of in-hospital CPR. A majority of respondents (73.4%) desired to participate in EOL training.

Table 2.

Clergy Knowledge and Desire for Training Regarding End-of-Life Care, n = 31

| Correctly answered (%) | Incorrect or not sure (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Understanding of hospice and palliative care | ||

| 1. Hospice care focuses on the comfort of patients who have 6 months or less. | 74 | 26 |

| 2. Palliative care is care that helps with symptoms (e.g., pain) of incurable disease. | 61 | 39 |

| Understanding of intensive care | ||

| 3. In the hospital, the percentage of people who survive CPR when their heart or breathing stops is 25% or less. | 19 | 81 |

| 4. When a person is intubated or has a tube connected to a machine that helps them breathe, they cannot talk. | 84 | 16 |

| 5. When a person is intubated or has a tube connected to a machine that helps them breathe, they cannot eat with their mouth. | 100 | 0 |

| 6. When a person is intubated or has a tube connected to a machine that helps them breathe, they are usually sedated (not conscious). | 71 | 29 |

| Understanding of pain management | ||

| 7. There is much that can be done for cancer pain. | 90 | 10 |

| 8. Cancer patients do not frequently become addicted to pain medications. | 26 | 74 |

| 9. There are effective treatments if you have side effects to pain medicines. | 68 | 32 |

CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

A theological framework for end-of-life decision making

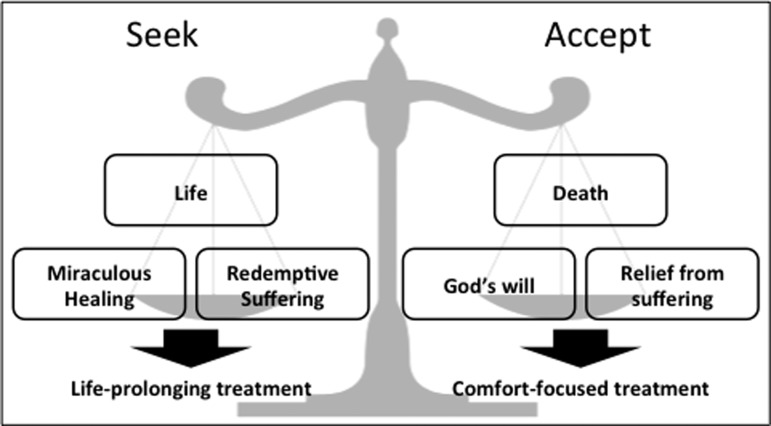

Qualitative data analysis suggested that clergy rely on a theological framework for EOL decision making that aims to balance two constructs, seeking and accepting. Refer to Figure 1 for a diagrammatic illustration and to Table 3 for representative quotes.

FIG. 1.

Theological framework for end-of-life decision making.

Table 3.

Themes and Representative Quotations Comprising a Theological Framework for End-of-Life Decision Making

| Seek… | Accept… |

|---|---|

| …Life | …Death |

| Every individual life is sacred…one should seek healing both through prayer and through available medical means.” (CG124) | How is your life going to glorify God? How, when you face this, can you face this in a way that will bring glory to the God who gave you life? (FG MJB314-2) |

| We do practice and we do believe in a culture of life… So I would say that yes, I would advise people to get aggressive treatment but it would depend on the situation. (JP414) | My faith tells me love God and we are here a short time. Very short time and we are going to die. So, time is short; do all the good you can. Love and help as many people as you can. That is very important. It is not written anywhere that you have to live longer. (CM1217) |

| Life is a gift. We don't take it for granted. It is precious. It is to be fought for. It is to be cherished. … The second piece, though, is that life is finite…and it comes to an end and then we enter into glory. The third piece then is God is sovereign and God's intention is that all would come to Him through His son. Therefore, we are all in, zealously striving to live into the kingdom on the earth and value life and the gifts that life gives us right up until the moment where you draw that last breath. (FG MJB314-3) | |

| …Miraculous Healing | …God's Will |

| “It's faith, I think, that if we can keep you going and keep praying and asking God and get enough people to pray… then maybe we'll reach that threshold, and God will answer the prayer and keep you going” (MB107). | First thing, [a congregant]… told the doctor, “Well, I don't want you to do CPR. If God calls me it means it is my time to go home and I don't want you to get in between God and me, but if God heals me then it means I still have things to do here. And so I will believe, but I don't want you to do CPR.” And he rejected CPR and all the way to the end he told people, “you know what, the best thing to do is to accept God's will; we were created to live.” … That is the thing, when you have that confidence you accept Gods' will on one hand, on the other hand you have faith. (FG MJB416-4) |

| I never want to foreclose the possibility of some healing. (FG MJB416-1) | |

| If we are not praying for the impossible sometimes we have no faith. (FG MJB416-11) | |

| That God can perform a miracle; obviously, that is true from our perspective. The reason we call them miracles is that the probabilities are not special high. They are miraculous and therefore not something you should plan on. If it happens, then glory to God but if in the meantime if you are told that you are dying then I think you should try to come to terms with that; make peace with that and place yourself in God's hands. (CG124) | |

| God can do everything. He can raise someone from the dead if he wants. Yes, God can do a miracle. Don't be angry if he doesn't make a miracle because God's will is inscrutable. We don't know his ways. (CM1217) | |

| …Redemption through Suffering | …Relief from Suffering |

| Our Lord Jesus Christ suffered a lot for a good purpose; for a higher purpose: our salvation. … Suffering is part of life but united to Christ it is possible. (CM1217) | I'm the kind of person that if you have a pill or breakthrough that can relieve suffering, I'm not going to sit there and suffer. Give me the shot. Just give me the shot because I also believe that God gave you the wisdom to make the medications and whatever means to offer and administer health. (MB129) |

| “I do think there is a kind of testing, a sort of reckoning, almost a reevaluation of a relationship with God that comes through illness. Maybe we can call that testing, in a way of reaching out to God and God reaching out to us in our suffering, and you find some value in the suffering” (RT1114). | |

| I don't think God calls us perhaps to suffer in that kind of way. (FG MJB1030A) | |

| We do think that suffering is part of God's way of testing me but at the same time we don't invite or embrace painful procedures. (CG124) | |

| A lot of people think also that they must suffer; that when I suffer I place my sufferings at the foot of the cross and it is redemptive suffering, which is true, but nobody should suffer if there are ways to relieve them from suffering. (CM1219) | |

Seek life and accept death

Participants widely agreed that human life is sacred. However, the preservation of life as a precious gift from God in the setting of serious illness needed to be understood in the context of human mortality. More than mere biological function, clergy viewed life as a process of meaning–making in the eyes of God. Moreover, as one's God-endowed identity and human dignity become threatened by the suffering and reduced consciousness resulting from invasive medical care, a transition from seeking life to accepting death as the next stage in God's plan rises to critical importance. Clergy highlighted the critical importance of the transition from seeking life to accepting death, as noted in these words from a Hispanic Pentecostal pastor:

“We do believe in a culture of life…but there are some situations where I think … you might even be losing more than gaining something by trying… There are some moments where you need to let go and…accept that you are dying” (JP414).

Seek miracles and accept God's will

Participants frequently referenced divine miraculous healing as a source of hope and a potential motivation for life-prolonging interventions. Miracles were unanimously viewed as possible, with several participants sharing personal accounts. However, all clergy upheld that miracles are rare and should not be depended upon. Many expressed concern that a focus on miracles could be disingenuous when a patient is dying, could engender false hope, and/or could precipitate a crisis of faith should a miracle not transpire.

In fact, clergy frequently referenced acceptance of God's will as a critical counterpoint to seeking miraculous healing. “I always say ‘If God wants.’ … God is not your [genie] lamp with your three wishes” (CM1217). Since death was not viewed as a finale, but rather as portal to God calling you home (FG Texas 3), clergy encouraged the acceptance of God's will. One black Chicago minister remarked, “Death itself is a cure to what ails you. It's the healing” (FG MJB1030-I).

Seek redemption through and accept relief from suffering

Clergy generally viewed suffering as a complex phenomenon: inevitable and therefore to be accepted; redemptive and therefore valuable; and important to relieve by all means necessary. As one said, “We don't suffer for the faith” (CM 1219).

Participants saw faith as therapeutic against suffering: “I think that a strong faith can minimize suffering and…help people endure pain” (CG124). Christian clergy viewed Christ's suffering on the cross as emblematic of God's companionship with those in distress. In this way, illness could strengthen one's intimacy with God and, in turn, give meaning to and alleviate their suffering. Similarly, a rabbi noted, “sort of reckoning, almost a reevaluation of a relationship with God that comes through illness. Maybe we can call that testing, in a way of reaching out to God and God reaching out to us in our suffering, and you find some value in the suffering” (RT11142014).

A moral framework for end-of-life decision making

Clergy highlighted themes that suggest a moral framework for guiding EOL decisions. Using these criteria to determine what is reasonable and rational (MB107), or proportionate (CM1219), patients can make treatment decisions informed by the benefits and burdens of treatment. Table 4 summarizes these themes with representative quotations.

Table 4.

Themes and Representative Quotations Comprising a Moral Framework for End-of-Life Decision Making

| Age, family, and community responsibility |

|---|

| If you look at a 25 year old and a 95 year old, there are two different mindsets on decision making with those ages. A 95 year old a DNR may be a totally moral decision to make. For a 25 year old to say I don't want a DNR and they are a healthy person, that is an immoral decision to make. (CM1219) |

| I might have a heart attack, but I am 35 years old and I have three children. And my wife, she is not working. I need to have a resuscitate me order. It's like, “Yes! Resuscitate me! Please! If possible.” It depends. Maybe ‘I am 93 years old. Let me die. If God calls me I've already lived a long time. I don't mind. If I have a heart attack, it's my time.’ So it depends. It's neither moral nor immoral. (CM1217) |

| There does come a point where, just out of duty and a sense of obligation, the people are investing resources where it's just not rational; it just doesn't make sense. But because they feel guilty, or pressure from the family, they just had to do it. (MB107) |

| The family is just convinced that they have to do everything possible; they don't want to lose this loved one. Like my mom she died of pancreatic cancer and when she came out of surgery and they told her it was cancer and what they had done, she immediately started getting ready for death. I mean, she was just as courageous as anybody I've ever seen in my life. And the family, we're just like “you have to do everything possible.” (FG MJB416-11) |

| Prognosis and treatment burden |

|---|

| Once the dying process is recognized as basically having the upper hand, I guess the teaching of the church would lean toward those that want to make heroic measures may do so, but the teaching of the church would lean toward saying that dying is a part of this life, that is nothing to be afraid of. (CG124) |

| Sometimes you will have to forgo some medical treatment because they are too evasive or burdensome and you just, with the help of doctors, better forgo it and accept the natural course of events or natural process of death. That is part of acceptance. (CM1217) |

| You come to that third, forth, filth round of chemotherapy your body is being ravished. You are miserable and the cancer itself has no known cure. You can let it take its normal course. … But you can also say, wait a minute, enough is enough. The burdens are outweighing the benefits and it is disproportionate for me to continue on, and you could say, no I just want comfort care. (CM1219) |

| “We know there is nothing medicine can do, but we know God can. God can. I heard stories about people that doctors said are going to die in 2, 3 months, 4 months, and they live 10, 15 years.” (MB1021) |

| Now if they tell me she had a two percent possibility of living, even that two percent is valid because it could be that among one hundred God says she will live. … If the person says there is no percent chance of life but I will still trust that God can do a miracle and I will submit, I would tell them that that is a good option because sometimes doctors steal their hope and say they are not going to live, but God does other things and they end up living longer (JP0049). |

| Free will |

|---|

| I would say my belief in God encourages me to think about a healthcare proxy, it encourages me to think about a DNR; which can be appropriate at times. …. We have been given the ability to think and to reason and to make free choice and these are the choices that we have to make. Depending on the benefits and burdens of where I am in my lifetime and what those benefits and burdens are, a DNR may be appropriate. (CM1219) |

| I would just be an automaton if I did not think about things. So I still have choice in the matter although ultimately God trumps me, but he gives me freedom of choice. So I can choose although in the end of the day his will shall be done. So I am not relieved of my ability or choice to think about it. (MJB1030) |

| You hear, you learn and based on your convictions, you decide. Based on the convictions of the scriptures, His word, your understanding; you decide. Do you want the treatment or do you not want the treatment? … I don't jump into those kinds of things because I think that is up to the patient to decide; how much, how little or when. (MB129) |

| Dying the way you want to die is consistent with our religion. If you want to die in ICU pursuing life, that's your choice. If you want to die at home with hospice care, that's your choice and we support both of them. Neither one is right or wrong. One is definitely more comfortable than the other. (RT0819) |

DNR, do-not-resuscitate order.

Age, family, and community responsibility

Clergy cited age and family or community responsibility as factors that should impact decision making. In contrast to the elderly, young people were thought to have more responsibility to pursue therapies aimed at prolonging life. Similarly, clergy indicated that family and community responsibilities might or should lead one to pursue intensive treatment options, whether out of duty or a sense of obligation (MB107).

Prognosis and treatment burden

Faith in God's ultimate power to heal and examples of patients outliving the prognoses given by their physicians led several clergy to feel that decisions to pursue invasive treatment may be justified by prognostic uncertainty. Although death is inevitable, many felt the timing was potentially unknowable by clinicians. As one said, “We know there is nothing medicine can do, but we know God can. I heard stories about people that doctors said are going to die in 2, 3 months, 4 months, and they live 10, 15 years” (MB1021).

Despite doubts about prognostic accuracy, most clergy viewed the recognition of approaching death as an inflection point around which treatment decisions might change. When the burden of illness and invasive treatments result in excessive suffering, the pursuit of life-prolonging interventions should be abandoned in favor of accepting the natural course of events (CM1217).

Free will

Clergy consistently underscored the individual nature of decision making in serious illness because of God's gift of free will, that is, a sense of agency or autonomy in decision making. On the one hand, free will gives people the power to choose. As one said, “Some people want [more aggressive care] and some people don't” (MB1030). While some tied this choice to faith, others indicated that it was a choice independent of faith. Of note, however, free will imparted the weight of moral responsibility. Thus, deferring or neglecting medical decision making in deference to faith was considered problematic: “Nothing relieves me of needing to think. I believe it is because God gives me, if you want to put a theological term on it, free will.” (MJB1030-H).

The clergy role in EOL decision making

Clergy were ambivalent about and adopted a passive approach to counseling congregants about decision making despite having defined beliefs regarding EOL care. No respondent viewed aggressive care as a clear good; several said that it hampered a good death, and one indicated that it was an absolute bad. The majority indicated that the appropriateness of the decision depended on each patient's preferences, circumstances, and self-assessment of likely treatment outcomes. Beliefs about free will lead clergy to refrain from influencing EOL medical decisions to value patient discretion over moral consideration. They embraced the role of supporting, not questioning, a seriously ill patient's decision to pursue aggressive or comfort-focused care. Descriptions of their faith tradition's view on the moral appropriateness of aggressive care (Table 5) both reinforced the individual nature of EOL decision making and highlighted the tension inherent to their passivity.

Table 5.

Clergy and Their Faith Tradition's Views on the Appropriateness of Aggressive Care at the End of Life

| “[Getting aggressive care is] not consistent with my personal faith. Maybe the organization as a whole might consider it one way or the other, but again, I think it has to do with a lot of things that are personal to the patient and what they are dealing with specific to their family, to their environment, to those things.” (RT729) |

| “Bad. … Again, if the family wants to do that we are not going to tell them that it is bad. But I think the generally attitude would be that the person needs to come to terms with death to accept the fact that they are dying, and to reduce their fear of it. Again, that is something we all have to go through. But, in our situation that is not the end of everything; it is not oblivion. (CG124) |

| I would be inclined for the palliative care and forgo that extraordinary measurements in which the person is almost unconscious and the person cannot even speak or relate to family members; cannot even pray, perhaps. I would see those things as kind of a handicap for a good death. … But I think the spiritual good of a good death is a high priority. (CM1217) |

| I think it is an individual decision based on benefits and burdens and proportions and disproportions. … You can't just say one way or the other. (CM1219) |

| My theology sees the real world, and it really does weigh, it does consider the cost in terms of what is reasonable and rational and what is unreasonable and irrational. There does come a point where, just out of duty and a sense of obligation, the people are investing resources where it's just not rational; it just doesn't make sense. (MB107) |

| There are ways we can extend life, but also if someone has a conviction that they rather die, if they consider dying with dignity and it has to do with leaving this earth with peace and they don't want to take any treatment, I don't think they are turning their backs to their faith. (JP414) |

| Dying the way you want to die is consistent with our religion. If you want to die in ICU pursuing life, that's your choice. If you want to die at home with hospice care, that's your choice and we support both of them. Neither one is right or wrong. One is definitely more comfortable than the other. (RT0819) |

| I don't know if I could answer whether it's good or bad. It depends on what the patient, patient's family has discussed before. As long as they've thought about their decisions before, at that point I'm not going to evaluate it or judge it. I'd say it's not consistent or inconsistent with the traditions' vision of a good and faithful death. It just really depends on if it's done with a sense of peace, concern, and thoughtfulness. I guess, in general, it's not, but I would be reluctant to judge it if it's entered into with open eyes on part of the family and the patient. (RT1114) |

| I don't think it is a good death. It is very traumatic even to the family going into ICU seeing the patient. Many cry instantly. And seeing the person struggling for air and with all its tubes, are cut in the throat, inserting. It's not my idea of a good death. (TC1030) |

A few clergy suggested that they may be too passive in this role: “We have not done a good job…on preparing people to die–that they don't need to live the last days of their lives under terrible and excruciating pain” (JP414). Another located clergy passiveness within a general culture of death denial: “I am not real sure that there is a lot of being in touch with the reality of death. There is always this sense of false hope when death is inevitable, when death is something we should be embracing, we want to heal them…in the name of Jesus” (MJB1030-E). A few lamented that clergy passiveness was partially a result of the patient or family not consulting the minister on medical issues until it is too late: “…people don't come to ask for advice. They do things and call us when they are dead or at the point of dying” (CM1219).

Discussion

This multimethod study describes how clergy conceptualize religious rationales for, and their role in, medical decision making by congregants facing terminal illness. Clergy described a balanced approach to spiritual care in which they upheld the sanctity of life while validating the timely acceptance of death. Most affirmed that comfort-focused treatments were consistent with their faith and may facilitate a good death. Clergy apply theological and moral principles to determine the appropriateness of EOL decision making, which uphold free will, balance seeking life and accepting death as God's will, and weigh the impact of age, family responsibility, and burden of treatment. A comfort-focused approach to EOL care was upheld as ideal, yet EOL care choices were viewed to be the primary prerogative of patients and their families.

Clergy demonstrated little knowledge of EOL care, such as the role and benefits of palliative care and potential harms inherent to invasive interventions. Many grossly overestimated the benefits of aggressive medical procedures at end of life. Few clergy expressed awareness of other key factors such as disease staging and the burdens of invasive treatment, and many distrusted prognostic information. Most desire more EOL care training, which may reflect their uncertainty about these topics and hence their ambivalence about counseling congregants about EOL care decisions. Given the complexities of and uncertainties about decision making in this context and an emphasis on free will, clergy overwhelmingly viewed their role in their congregants' EOL medical decision making as passive.

These findings extend and contextualize previous studies in this area, which have reported that religious or spiritual coping and religious community spiritual support are associated with patient preferences for intensive EOL care,27 optimistic prognostic perceptions,28,29 more intensive cancer care, and less frequent and shorter hospice use.14,20 Our data indicate that many clergy view these EOL outcomes to be undesirable and inconsistent with their own religious traditions.17 Despite their balanced approach of seeking and accepting, clergy were reluctant to confront potentially simplistic patient presuppositions about the sanctity of life and miracles that drive the pursuit of life prolongation at any cost. This is, in part, because religious expressions of hope reflect faith in God, which clergy seek to strengthen rather than undermine. Some clergy acknowledged this apparent tension and rationalized it by upholding congregants' free will to make EOL decisions.

Our data indicate that clergy, in their role as theological and moral guides, may unintentionally enable congregants' decisions to pursue nonbeneficial invasive care when terminally ill. This may be true even when they feel that such care may be neither theologically mandated nor morally proscribed and may both contribute to suffering and impede a good death. For example, while hope in a miracle in the setting of terminal prognosis can be an authentic expression of faith, it can also be a sign of unexpressed fears and/or denial of dying.30 Furthermore, it may lead to spiritual crisis if no miracle occurs.

Our study reveals an opportunity for clergy to guide their congregants by proactively presenting a theological account that upholds each axis point of seeking and accepting (Fig. 1). In circumstances where the patient or loved ones are focused exclusively on cure despite a poor prognosis, it may be especially incumbent upon the patient's minister to pastorally introduce the importance of acceptance, even if still legitimizing hope for cure. This theological balance parallels a strategy articulated in the palliative care in oncology literature, which strives to balance hope and realism as a therapeutic goal.31 Clergy may benefit from learning communication approaches that help strike this balance for patients facing poor prognoses.

Rather than undermining free will, helping seriously ill congregants navigate decision making using a framework that balances seeking and accepting may provide a richer understanding of the spiritual implications of treatment decisions. A growing medical literature in shared-decision making supports this approach.32,33 Patients may feel abandoned by clinicians who, to avoid paternalism, rigidly apply the bioethical principle of autonomy and provide treatment options without guidance.34 They may find clergy's passive approach to counseling similarly inadequate. These findings suggest an opportunity for clergy to embrace a more active role, not by proscribing medical decisions per se, but by emphasizing a wider theological framework that accounts for poor prognosis, the potential futility of treatment, acceptance of death, and consideration of comfort-focused care. This suggests the need for greater clergy education in EOL care.

Community-based outreach and education by medical professionals to clergy and faith communities remain untapped opportunities and a strategic step forward in disease-based and palliative care.35–37 Community clergy forge long-term relationships with congregants, carry spiritual influence, and may therefore be best qualified to advise on challenging religious issues.36,38 Consistent with other studies, clergy in this study desire additional education around decision making in serious illness and EOL care.22,23

We have proposed elsewhere a framework for clergy education that accounts for who clergy are, what they do, and what they believe.25 Because clergy neither advocate for invasive medical care nor perceive it necessarily as a moral good, this study highlights a tension between beliefs and practice that reveals a potential target for educational intervention. For example, a deeper understanding of the factors that shape clinician prognostication, the impact of invasive medical procedures in the setting of terminal illness, and the care models available to alleviate suffering (e.g., palliative care and hospice) would empower clergy to counsel congregants about the moral and spiritual implications of EOL medical decisions.

This study has some notable limitations. Foremost among these, qualitative design offers in-depth perspectives that may not be generalizable. While ethnically diverse and representative of US congregations,39 our sample was predominantly male, Christian, and theologically conservative (the latter a feature of our purposive sampling). Perspectives of clergy representing other religions require further exploration. Finally, our sample had a higher than average level of education, which may suggest that the need for further education is understated by our sample.

Conclusions

Clergy describe a theological framework that balances seeking life and accepting death, but their moral framework dominated by free will may lead to pastoral care approaches that passively enable congregants to pursue potentially nonbeneficial EOL treatments associated with increased suffering. Clergy education represents an important opportunity to close the gap between clergy's beliefs and actions, to support religiously informed decision making by patients that minimizes unnecessary physical and spiritual suffering, and to partner with disease-based and palliative care clinicians to improve the EOL care of patients with serious illness.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The study was made possible by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) #CA156732, The Issachar Fund, and supporters of the Initiative on Health, Religion, and Spirituality within Harvard University. J.S. acknowledges the generous support of the Richard A. Cantor Fund for Communications Research in Palliative Care.

Research staff provided critical support, including Christine Mitchell, MDiv, PhD candidate, Carol Green, BS, and Richard Timms, MD.

Author Disclosure Statement

No conflicting financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Pew Research Center: America's Changing Religious Landscape. May 12, 2015. www.pewforum.org/2015/05/12/americas-changing-religious-landscape (last accessed September15, 2016)

- 2.Thune-Boyle IC, Stygall JA, Keshtgar MR, Newman SP: Do religious/spiritual coping strategies affect illness adjustment in patients with cancer? A systematic review of the literature. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:151–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. : Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA 2000;284:2476–2482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puchalski CM: Spirituality in the cancer trajectory. Ann Oncol 2012;23 Suppl 3:49–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vallurupalli M, Lauderdale K, Balboni MJ, et al. : The role of spirituality and religious coping in the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative radiation therapy. J Support Oncol 2012;10:81–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coats H, Crist JD, Berger A, et al. : African American Elders' Serious Illness Experiences: Narratives of “God Did,” “God Will,” and “Life Is Better”. Qual Health Res 2015. [Epub ahead of print; DOI: 10.1177/1049732315620153] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Loike J, Gillick M, Mayer S, et al. : The critical role of religion: Caring for the dying patient from an Orthodox Jewish perspective. J Palliat Med 2010;13:1267–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopez-Sierra HE, Rodriguez-Sanchez J: The supportive roles of religion and spirituality in end-of-life and palliative care of patients with cancer in a culturally diverse context: A literature review. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2015;9:87–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salsman JM, Fitchett G, Merluzzi TV, et al. : Religion, spirituality, and health outcomes in cancer: A case for a meta-analytic investigation. Cancer 2015;121:3754–3759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alcorn SR, Balboni MJ, Prigerson HG, et al. : “If God wanted me yesterday, I wouldn't be here today”: Religious and spiritual themes in patients' experiences of advanced cancer. J Palliat Med 2010;13:581–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winkelman WD, Lauderdale K, Balboni MJ, et al. : The relationship of spiritual concerns to the quality of life of advanced cancer patients: Preliminary findings. J Palliat Med 2011;14:1022–1028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balboni TA, Vanderwerker LC, Block SD, et al. : Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:555–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balboni TA, Balboni M, Enzinger AC, et al. : Provision of spiritual support to patients with advanced cancer by religious communities and associations with medical care at the end of life. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1109–1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phelps AC, Maciejewski PK, Nilsson M, et al. : Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. JAMA 2009;301:1140–1147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, et al. : Family perspectives on aggressive cancer care near the end of life. JAMA 2016;315:284–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, et al. : Place of death: Correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers' mental health. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4457–4464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LeBaron VT, Cooke A, Resmini J, et al. : Clergy views on a good versus a poor death: Ministry to the terminally ill. J Palliat Med 2015;18:1000–1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans AR: Is God Still at the Bedside?: The Medical, Ethical, and Pastoral Issues of Death and Dying. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balboni TA, Paulk ME, Balboni MJ, et al. : Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: Associations with medical care and quality of life near death. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:445–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balboni TA, Balboni M, Phelps AC, Gallivan K, et al. : Provision of spiritual support to advanced cancer patients by religious communities and associations with medical care at the end of life. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1109–1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Widera EW, Rosenfeld KE, Fromme EK, et al. : Approaching patients and family members who hope for a miracle. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;42:119–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams ML, Cobb M, Shiels C, Taylor F: How well trained are clergy in care of the dying patient and bereavement support? J Pain Symptom Manage 2006;32:44–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abrams D, Albury S, Crandall L, et al. : The Florida clergy end-of-life education enhancement project: A description and evaluation. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2005;22:181–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LeBaron VT, Smith PT, Quinones R, et al. : How community clergy provide spiritual care: Toward a conceptual framework for clergy end-of-life education. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:673–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malterud K: Qualitative research: Standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet 2001;358:483–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crabtree BF, Miller WL: Doing Qualitative Research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 27.True G, Phipps EJ, Braitman LE, et al. : Treatment preferences and advance care planning at end of life: The role of ethnicity and spiritual coping in cancer patients. Ann Behav Med 2005;30:174–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyd EA, Lo B, Evans LR, et al. : “It's not just what the doctor tells me:” factors that influence surrogate decision-makers' perceptions of prognosis. Crit Care Med 2010;38:1270–1275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zier LS, Burack JH, Micco G, et al. : Surrogate decision makers' responses to physicians' predictions of medical futility. Chest 2009;136:110–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sulmasy DP: Distinguishing denial from authentic faith in miracles: A clinical-pastoral approach. South Med J 2007;100:1268–1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell TC, Carey EC, Jackson VA, et al. : Discussing prognosis: Balancing hope and realism. Cancer J 2010;16:461–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hinkle LJ, Bosslet GT, Torke AM: Factors associated with family satisfaction with end-of-life care in the ICU: A systematic review. Chest 2015;147:82–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kvale K, Bondevik M: What is important for patient centred care? A qualitative study about the perceptions of patients with cancer. Scand J Caring Sci 2008;22:582–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roeland E, Cain J, Onderdonk C, et al. : When open-ended questions don't work: The role of palliative paternalism in difficult medical decisions. J Palliat Med 2014;17:415–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balboni MJ, Balboni TA: Reintegrating care for the dying, body and soul. Harv Theol Rev 2010;103:351–364 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. : Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: The report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med 2009;12:885–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Balboni MJ, Sullivan A, Enzinger AC, et al. : United States clergy religious values and relationships to end-of-life discussions and care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Rodin D, Balboni M, Mitchell C, et al. : Whose role? Oncology practitioners' perceptions of their role in providing spiritual care to advanced cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2015;23:2543–2550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chaves M: Congregations in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.