Abstract

Background: Pediatric fellows receive little palliative care (PC) education and have few opportunities to practice communication skills.

Objective: In this pilot study, we assessed (1) the relative effectiveness of simulation-based versus didactic education, (2) communication skill retention, and (3) effect on PC consultation rates.

Design: Thirty-five pediatric fellows in cardiology, critical care, hematology/oncology, and neonatology at two institutions enrolled: 17 in the intervention (simulation-based) group (single institution) and 18 in the control (didactic education) group (second institution). Intervention group participants participated in a two-day program over three months (three simulations and videotaped PC panel). Control group participants received written education designed to be similar in content and time.

Measurements: (1) Self-assessment questionnaires were completed at baseline, post-intervention and three months; mean between-group differences for each outcome measure were assessed. (2) External reviewers rated simulation-group encounters on nine communication domains. Within-group changes over time were assessed. (3) The simulation-based site's PC consultations were compared in the six months pre- and post-intervention.

Results: Compared to the control group, participants in the intervention group improved in self-efficacy (p = 0.003) and perceived adequacy of medical education (p < 0.001), but not knowledge (p = 0.20). Reviewers noted nonsustained improvement in four domains: relationship building (p = 0.01), opening discussion (p = 0.03), gathering information (p = 0.01), and communicating accurate information (p = 0.04). PC consultation rate increased 64%, an improvement when normalized to average daily census (p = 0.04).

Conclusions: This simulation-based curriculum is an effective method for improving PC comfort, education, and consults. More frequent practice is likely needed to lead to sustained improvements in communication competence.

Keywords: : communication, end-of-life, medical education, palliative care, pediatric fellows, pediatrics, simulation

Introduction

Over 400,000 U.S. children live with life-threatening or chronic, complex conditions, spending significant time in the hospital interacting with healthcare professionals (HCPs).1,2 Their families depend on excellent communication, guidance, and care coordination as they make difficult medical decisions, including choices around end-of-life care.3–5 Supporting these families requires physicians trained in palliative care (PC) communication. Multiple professional societies recommend that physicians who care for seriously ill patients have basic PC skills: competency in pain and symptom management, end-of-life care, communication, decision-making support, ethics, and psychological and spiritual dimensions of care.2,6,7 Although PC skills can be learned through clinical encounters, pediatric residents (post-medical school years one–three) and fellows (years four–six) have few opportunities to do so as they conduct few PC conversations, care for a small number of patients who die, and receive inconsistent feedback and supervision regarding these skills; this learning method can be harmful for patients and families, and has led to pediatricians and pediatric subspecialists who lack PC experience, knowledge, competence, and respectful communication skills.5,8–19

Families, trainees, and program directors have recognized this gap.6–8,12,15,17,20–22 Yet, most pediatric fellowship programs lack formalized PC education; when education is provided, it is often lecture-based rather than experiential.17,20,21,23–26 Simulation-based training, successful in other high-stakes communication encounters,27,28 has the potential to change PC education in pediatrics.29,30 Similar to communication during resuscitation, communication around PC/end-of-life care is a discrete skill to be learned, practiced, and mastered. Prior PC simulation research has focused on adult clinicians,31–37 pediatric residents,26,38–40 and nurses of varying levels.41,42 Few studies have targeted pediatric fellows43–46 or followed longitudinally.47

The goal of this study was to assess the relative effectiveness of simulation-based versus didactic training on pediatric fellow self-efficacy (comfort), knowledge, and satisfaction with PC medical education. For the simulation-based group, we assessed fellow communication competence including retention over time, and monitored referrals to a pediatric PC team. We hypothesized that fellows receiving simulation-based education, compared to fellows receiving didactic education, would perceive that they received better PC education, and demonstrate improved PC comfort, knowledge, and competence.

Methods

Study design

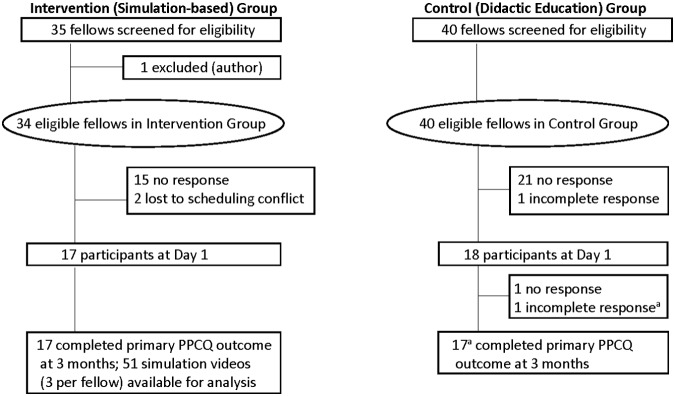

From August to November 2014, pediatric fellows enrolled at two sites: Stanford University (simulation-based site) and the University of Colorado (didactic site). Eligible fellows were first, second, or third-year fellows in Pediatric Cardiology, Critical Care, Hematology/Oncology, or Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine (Fig. 1). Recruitment occurred by e-mail invitation. Fellows signed consent for videotaping and were compensated (≤$25 gift card) for their participation. Both institutions have free-standing children's hospitals with similar patient volume and complexity, and similar size fellowships that lack a formal PC curriculum. Institutional Review Board approvals were waived at both institutions.

FIG. 1.

Fellows are first, second, or third-year fellows in Pediatric Critical Care, Cardiology, Hematology/Oncology, or Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine. aData used for analysis when full section completed (self-efficacy, adequacy of medical education, knowledge, barriers to palliative care).

Curriculum details

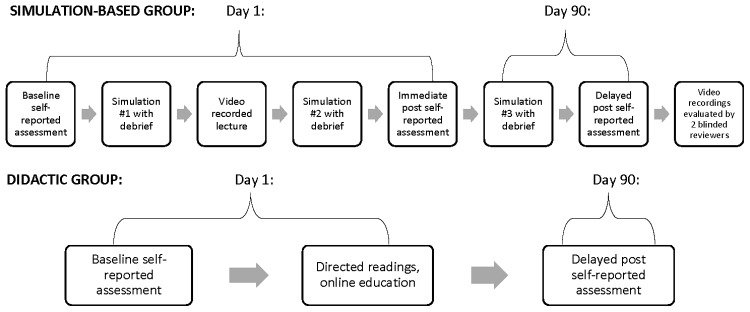

Fellows in the simulation group individually participated in a two-day, 4.5-hour curriculum consisting of (Fig. 2):

FIG. 2.

Study timeline for the simulation-based and didactic groups. Each simulation-based participant completed the entire schema above. Each simulation scenario was allotted 15 minutes with 30 minutes for debriefing. Didactic group fellows were able to complete education at a self-directed pace.

-

1. Three specialty-specific simulated scenarios with debriefing (by K.B and patient “mother”). Each involved children with life-threatening conditions, focusing on three themes of increasing complexity:

(a) introducing PC

(b) discussing goals of care including end-of-life and resuscitation preferences, and

(c) mediating disagreement between the family and medical team.

2. A 75-minute videotaped PC panel discussion delivered by PC faculty (H.C., B.S., J.G) and bereaved parents. Full curriculum and surveys available at MedEdPORTAL.48

Two scenarios occurred on day one; the third was conducted three months later to assess retention. To ensure reproducibility, all scenarios utilized four learning goals, uniform room setup, similar family background information across specialties for each theme, one trained simulation specialist acting as the patient's mother, and a standardized debriefing guide.48

Control group participants received didactic PC education via hyperlink and e-mail after finishing their baseline assessment, allowing curriculum completion over the study period duration. This was designed to be similar in content and time to the intervention group (one published article, four online videos, and six PowerPoint presentations) highlighting PC communication, family meetings, pain and symptom management, medical decision making, and values, benefits, and burdens of treatments.49–54 No fellows were prohibited from educational experiences that occurred throughout fellowship.

Fellow self-assessment data collection

Both groups completed self-assessments using the Pediatric Palliative Care Questionnaire (PPCQ) at baseline and day 90 (intervention group mean 90 days [standard deviation, SD 14 days], control group mean 101 days [SD 14 days]).55 Intervention group fellows also completed the PPCQ after day one (Fig. 2).

The PPCQ has good test-retest reliability, internal consistency, and validity with subscales measuring: Self-Efficacy (comfort) with pediatric PC and communication, perceived adequacy of prior medical education in PC and symptom management, PC knowledge, and barriers to PC.55 Self-efficacy questions were scored from 1 to 5 with five being the most comfortable (summary score range 23–115).55 Adequacy of prior medical education questions were scored from 1 to 5 with five indicating more adequate training (summary score range 6–30).55 Knowledge questions included seven multiple-choice and three true-false questions (score range 0–10).55 Both groups completed post-intervention satisfaction questions (score range 1–5) with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction.

External reviewer evaluations of intervention group participants

Because physicians often self-report their competence inaccurately,56,57 external reviewers rated each subject using the Modified Kalamazoo Communication Assessment Tool (MKCAT), containing nine domains, each rated from 1 to 5 (poor–excellent). This tool has excellent reliability and validity.58,59 Scoring anchors were not previously provided, so anchors (e.g., behavior that constitutes a 3 vs. a 4) were devised and field tested with 11 multidisciplinary physicians, a PC psychologist, and two medical education experts until final approval.48

Two reviewers experienced in performance ratings, psychosocial research and bioethics were recruited from the medical student body, and trained over four sessions, using frame-of-reference training; five videos were used, providing a range of physician-family encounters. Videos were randomly ordered,60 and reviewers were blinded to the order. Utilizing a fully-crossed design (subset of participants rated by multiple raters), both reviewers then watched another 20% (10/51) of videos.61 A goal inter-rater reliability, measured by the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC), was set at ≥0.7 before dividing the remaining 70% of videos between the two reviewers (n = 18 each).62 ICC was 0.72. Weighted kappa, assigning increased weight to values within one point (128/135 scores), was 0.70.

Palliative care consultation rate

New PC consultations, average daily census (ADC) and hospital admissions from the Divisions of Pediatric Cardiology, Critical Care, Hematology/Oncology/Stem Cell Transplant, and Neonatology at Lucile Packard Children's Hospital Stanford (simulation site) were tracked in the six months preintervention (02/2014–07/2014), study period (08/2014–11/2014), and six months post-intervention (12/2014–05/2015). Outpatient visit data were collected for the Divisions of Cardiology and Hematology/Oncology/Stem Cell Transplant.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome was the difference in mean from baseline to three months for the Self-Efficacy Summary Score between the intervention and control groups. Secondary outcomes were the between-group difference in means over three months for the perceived Adequacy of Medical Education Summary Score and Knowledge Total score. Based on equal number of participants in the groups, power 0.8, alpha 0.05, SD 15, and true difference in means of 15, sample size estimation was 17 participants per group.63

Descriptive statistics were used to estimate the frequencies, mean, and SD of the study variables. Between-group differences in baseline characteristics and outcome measures were assessed using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables, and two-sample t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. The PPCQ five-point scale was converted to a binary variable with 4/5 being “comfortable” and 1/2/3 being “uncomfortable.” Multivariate logistic regression was used to determine whether the proportion of fellows moving from uncomfortable to comfortable changed over three months.

To assess within-group fellow communication competence, scores from the two blinded external reviewers were assessed for improvement and retention over time, initially with a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), and in post hoc analysis with paired t-test comparing performance in simulation #1 to simulations #2 and #3.

Difference in proportions z-score testing was used to compare the within-group proportions of PC consultations in the six months preintervention to post-intervention when normalized to ADC, hospital admissions, and outpatient visits. For all analyses, a two-tailed significance level was set at p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4, Enterprise Guide 6.1 (Cary, NC).

Results

Subject characteristics

Thirty-five eligible fellows enrolled: 17 fellows in the intervention (simulation-based) group, and 18 fellows in the control (didactic) group (Fig. 1). Demographic characteristics, prior PC education and experiences (Table 1), and baseline PPCQ Summary Scores were similar between the two groups (Table 2). Fellows had experienced similar types of education except for lecture-based education in residency (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/jpm).

Table 1.

Demographic Information for the Intervention and Control Groups at Baseline

| Simulation group (n = 17) | Didactic group (n = 18) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Mean (SD) | n (%) | Mean (SD) | p | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 14 (82) | 14 (78) | 1.0 | ||

| Male | 3 (18) | 4 (22) | |||

| Age, years | 32.1 (2.6) | 32.1 (1.7) | 0.94 | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 2 (13) | 2 (12) | 1.00 | ||

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 14 (88) | 15 (88) | |||

| Race | |||||

| White | 8 (50) | 16 (89) | 0.006* | ||

| Asian | 8 (50) | 1 (6) | |||

| Mixed | 1 (6) | ||||

| Year of fellowship | |||||

| First year | 6 (35) | 6 (33) | 0.64 | ||

| Second year | 7 (41) | 5 (28) | |||

| Third year | 4 (24) | 7 (39) | |||

| Subspecialty | |||||

| Critical care | 4 (24) | 5 (28) | 0.75 | ||

| Cardiology | 4 (24) | 2 (11) | |||

| Hematology/oncology | 7 (41) | 7 (39) | |||

| Neonatology | 2 (12) | 4 (22) | |||

| Religion | |||||

| Atheist/agnostic | 3 (19) | 8 (44) | 0.08 | ||

| Catholic/Christian | 8 (50) | 8 (44) | |||

| Hindu | 4 (25) | 0 (0) | |||

| Other/did not specify | 1 (6) | 2 (11) | |||

| Prior palliative care education | |||||

| Medical school | 0.60 | ||||

| 0 hours | 2 (12) | 1 (6) | |||

| 1–5 hours | 10 (59) | 9 (50) | |||

| 6+ hours | 5 (29) | 8 (44) | |||

| Residency | 0.32 | ||||

| 1–5 hours | 6 (35) | 10 (56) | |||

| 6 hours | 11 (65) | 8 (44) | |||

| Fellowship | 0.67 | ||||

| 0 hours | 4 (24) | 2 (11) | |||

| 1–5 hours | 8 (47) | 9 (50) | |||

| 6+ hours | 5 (29) | 7 (39) | |||

| Prior palliative care discussions | |||||

| Observed in fellowship | 0.40 | ||||

| 0 | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | |||

| 1–5 | 9 (53) | 7 (39) | |||

| 6+ | 7 (41) | 11 (61) | |||

| Led in residency | 0.06 | ||||

| 0 | 13 (77) | 7 (39) | |||

| 1–5 | 4 (24) | 10 (56) | |||

| 6+ | 1 (6) | ||||

| Led in fellowship | 1.0 | ||||

| 0 | 7 (41) | 7 (39) | |||

| 1–5 | 8 (47) | 8 (44) | |||

| 6+ | 2 (12) | 3 (17) | |||

| Prior DNR/DNI discussions | |||||

| Observed in fellowship | 0.79 | ||||

| 0 | 2 (12) | 2 (11) | |||

| 1–5 | 9 (53) | 7 (39) | |||

| 6+ | 6 (35) | 9 (50) | |||

| Led in residency | 0.73 | ||||

| 0 | 7 (41) | 5 (28) | |||

| 1–5 | 9 (53) | 12 (67) | |||

| 6+ | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | |||

| Led in fellowship | 1.0 | ||||

| 0 | 5 (29) | 4 (22) | |||

| 1–5 | 7 (41) | 8 (44) | |||

| 6+ | 5 (29) | 6 (33) | |||

| Cared for n patients who died | |||||

| As the resident on call/service | 0.56 | ||||

| 0 | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | |||

| 1–5 | 12 (71) | 9 (50) | |||

| 6+ | 4 (24) | 8 (44) | |||

| As the fellow on call/service | 0.28 | ||||

| 0 | 3 (18) | 1 (6) | |||

| 1–5 | 8 (47) | 6 (33) | |||

| 6+ | 6 (35) | 11 (61) | |||

One person in the didactic group did not self-report ethnicity. Percentage may not equal 100% due to rounding.

p significant at <0.05, obtained using Fisher's exact test (categorical variables) and two-sample t-test (continuous variables).

DNI, do not intubate; DNR, do not resuscitate; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Summary Scores for Self-Efficacy, Fellow Assessment of Prior Medical Education, and Knowledge Over Time

| Baseline | After three months | Δ in means within group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation mean (SD) | Didactic mean (SD) | Simulation mean (SD) | Didactic mean (SD) | Simulation mean (SD) | Didactic mean (SD) | Δ b/t groups | p | |

| Self-efficacy summarya | 79.3 (13.1) | 79.5 (16.9) | 95.7 (10.0) | 86.4 (12.1) | +16.4 (8.7) | +6.1 (9.0) | +10.3 | 0.003* |

| Limited self-efficacy summaryb | 45.9 (9.2) | 48.1 (10.4) | 59.1 (6.1) | 50.8 (8.9) | +13.1 (7.3) | +2.6 (6.8) | +10.5 | <0.001* |

| Medical education summaryc | 14.2 (6.5) | 18.6 (6.2) | 21.6 (4.9) | 19.1 (5.4) | +7.4 (5.2) | +0.4 (5.7) | +7.1 | <0.001* |

| Knowledge testd | 7.3 (1.8) | 6.4 (1.0) | 8.4 (1.2) | 8.2 (1.0) | +1.1 (1.9) | +1.8 (1.3) | −0.7e | 0.20 |

p significant at <0.05, by Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Range 23–115 (p = 0.97 between groups at baseline).

Range 14–70 (14 a priori-designated questions which curriculum was focused upon).

Range 6–30 (p = 0.05 between groups at baseline).

Range 0–10 (p = 0.10 between groups at baseline).

Negative score reflects larger increase in didactic than simulation-based group.

Fellow self-assessment data

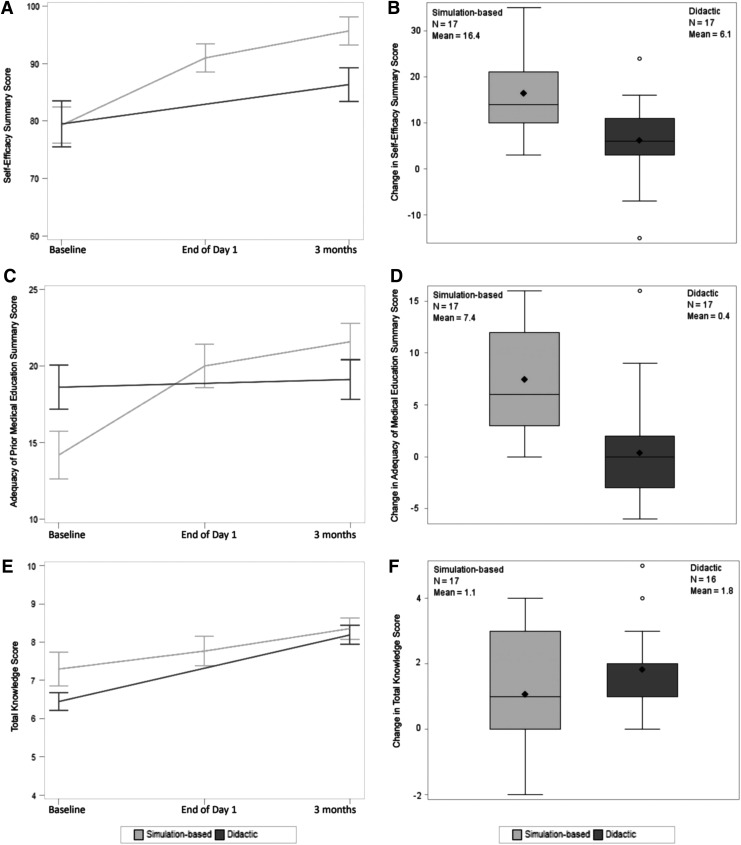

As assessed by the PPCQ Self-Efficacy Summary Score, over three months, the intervention group had improved self-efficacy (comfort) in pediatric PC compared to the control group (Δ between groups 10.3, p = 0.003) (Table 2, Fig. 3A, B, and Supplementary Table S2). Fellow comfort in the simulation group persisted at three months. Compared to the control group, more fellows in the intervention group rated themselves as “somewhat or very comfortable” with different PC tasks at the end of the intervention; this was notable for questions related to the simulation themes: (1) leading end-of-life discussions (increase of 53% vs. 9%, p = 0.002); (2) making a recommendation for no further cure-directed therapy (increase of 47% vs. decrease of 2%, p = 0.03), and (3) leading discussions where the family does not agree with the medical team (increase of 53% vs. 13%, p = 0.07) (Supplementary Table S3).

FIG. 3.

(A) Self-efficacy summary score at study time points. (B) Self-efficacy score mean change between simulation-based and didactic groups (p = 0.003). (C) Adequacy of medical education summary score. (D) Adequacy of medical education score mean change between groups (p < 0.001). (E) Total knowledge score. (F) Knowledge score mean change between groups (p = 0.20).

As assessed by the PPCQ Medical Education Summary Score, over three months, the intervention group felt they had received better PC training compared to the control group (Δ between groups 7.1, p < 0.001) (Table 2, Fig. 3C, D, and Supplementary Table S4).

Both groups PPCQ Knowledge test scores improved; there was no difference between groups (Δ between groups 0.7 favoring didactic group, p = 0.20) (Table 2 and Fig. 3E, F).

On a five point scale, the intervention group strongly agreed that the simulations felt realistic (4.5, SD 0.6), were similar to situations encountered in the hospital (4.8, SD 0.4), and enhanced their communication skills (4.8, SD 0.4). Despite a longer average time spent, intervention group participants more often felt that the time spent was appropriate (82% vs. 56%), valuing interactive time in simulation scenarios and debriefing. Only five control group fellows self-reported use of the educational videos and readings. Compared to controls, intervention group participants more strongly agreed that their PC education was useful (p = 0.02), would be used in clinical practice (p = 0.04), and recommended the education (p = 0.004) (Supplementary Table S5).

Palliative care communication competence

Repeated measures ANOVA (Table 3, pa) testing initially showed that fellows had improved communication competence scores over time. However, as plotting of individual results showed an initial rise in skills followed by some drop-off, post hoc analysis was undertaken assessing whether significance resulted from differences between simulation #1 and #2 (pb) or simulation #1 and #3 (pc). Intervention group fellows showed improvement over day one (pb) in four domains of the MKCAT58,59: relationship building (p = 0.01), opening the discussion (p = 0.03), gathering information (p = 0.01), and communicating accurate information (p = 0.04, paired t-test). However, these gains were not sustained over time (pc) (Table 3).

Table 3.

External Reviewer Ratings of Simulation Group Fellows

| Simulation-based education group only | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation #1 | Simulation #2 | Simulation #3 | ||||

| Modified Kalamazoo communication skills assessment58,59 | Mean (SD) n = 17 | Mean (SD) n = 17 | Mean (SD) n = 17 | pa | pb | pc |

| External reviewer assessment: | ||||||

| Builds a relationship | 3.6 (0.6) | 4.1 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.7) | 0.04* | 0.01* | 0.38 |

| Opens the discussion | 3.4 (0.7) | 4.0 (0.6) | 3.4 (0.6) | 0.01* | 0.03* | 1.0 |

| Gathers information | 3.4 (0.7) | 4.1 (0.8) | 3.5 (0.8) | 0.01* | 0.01* | 0.58 |

| Understands the patient's and families perspective | 2.7 (0.8) | 2.9 (0.9) | 3.0 (1.1) | 0.59 | 0.62 | 0.32 |

| Shares information | 3.0 (0.8) | 3.0 (0.8) | 2.9 (1.0) | 0.95 | 0.77 | 0.91 |

| Reaches agreement | 3.3 (0.4) | 3.4 (0.9) | 3.3 (0.9) | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.17 |

| Provides closure | 3.2 (0.7) | 2.9 (0.7) | 3.0 (0.5) | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.10 |

| Demonstrates empathy | 3.2 (0.7) | 3.8 (0.9) | 3.2 (1.1) | 0.08 | 0.06 | 1.0 |

| Communicates accurate information | 3.5 (0.9) | 4.1 (0.8) | 3.7 (0.7) | 0.11 | 0.04* | 0.50 |

p significant at <0.05.

Repeated-measures ANOVA over three simulations (pa). Post hoc analysis using paired t-test showed significance was not a result of difference between simulation #1 and simulation #3 (pc), but rather between simulation #1 and simulation #2 (pb).

ANOVA, analysis of variance.

Palliative care consultation rates

At the simulation-based institution, PC consultations increased 64% from the divisions of Pediatric Cardiology, Critical Care, Hematology/Oncology/Stem Cell Transplant, and Neonatology in the six months post-intervention (n = 41) compared to the six months preintervention (n = 25). The post-intervention proportion of consultations was higher when normalized to the ADC (43.2% vs. 28.4%, p = 0.04) or clinic visits (0.4% vs. 0.2%, p = 0.009), but not when normalized to inpatient admissions (2.7% vs. 1.8%, p = 0.11).

Discussion

In this two-site prospective study, simulation-based training resulted in sustained improvement in fellow comfort and perceived adequacy of PC education, was more highly rated than didactic education, and may correlate with increased utilization of specialty PC services. While external reviewers saw short-term improvement in some communication skills, these were not sustained over three months.

This simulation-based PC communication study is the first prospective, longitudinal, multispecialty, multi-institution trial comparing simulation-based education to didactic education for learning PC communication skills. Previous simulation-based communication studies mostly focused on delivery of information, for example, “breaking bad news,” rather than complex goals of care discussions,39,64 and measured self-efficacy after one day, providing little data about a fellow's development. A study that assessed fellows over 6–12 months lacked a control group,47 and thus, it remained unknown whether the improvement seen was due to usual training experiences or the educational intervention. This study builds upon prior authors' work and recommendations by utilizing a control group to monitor the baseline change in skills acquired through fellowship training, and external reviewer assessments to provide a proxy for family perception of fellow performance.57

Excellent communication is the central tenet of providing high quality shared decision making, symptom management, and PC concordant with family values. As the complexity of pediatric care grows, quality interactions with HCPs become more important in a child's healthcare journey.4,8 Yet, many pediatricians and subspecialists are uncomfortable with incorporating PC communication skills throughout a child's disease course.12,14,15,17,20 While sub-specialty PC teams can be beneficial in this regard, there are too few teams on which to rely.2,6 Therefore, improving the quality of PC communication by all clinicians is a priority.2,6,7

Several features make this program unique. The published curriculum and questionnaire make this easily reproducible.48,55 Consistent with other studies, trainees preferred experiential learning,39 and felt more comfortable after the intervention. However, control group data indicate that comfort also improves through usual training coupled with didactic education. Therefore, the interval improvement of the intervention group over the control group reflects the effect of the simulation-based training over a commonly used medical education training model.

This study was designed to underestimate results in several ways. Without the ability to reflect on what was learned, fellows' self-reported baseline scores may be higher than their true skill level. This response shift bias underestimates program effect, and could be reduced by using a retrospective pretest design where participants assess both their pre- and post-intervention self-efficacy at the same time, improving overall accuracy.65,66 Despite improvement, some fellows report a maximum comfort lower than “5” due to the difficulty of the content; self-reporting proficiency or competence may allow for greater score variability. In practice, simulation programs would generally have fellows participate in groups, watch other fellows' performances, and debrief as a group, which would maximize skill acquisition.45 Lastly, increasing the complexity of the scenarios is designed to build skills incrementally, but reviewers are less likely to rate simulation #3 as being significantly better than simulation #1.

Study limitations

There are several limitations to this study. Factors limiting recruitment included the small size of pediatric fellowships and lack of protected time. Participants likely had a greater interest in PC communication than nonparticipants, leading to selection bias. Although there may be institutional confounders (PC culture, diversity of residency training, patient demographics and complexity) that limit comparability across institutions, there were minimal differences in demographic, educational variables, baseline PPCQ scores, and factors influencing participation.

Despite making didactic education readily accessible, only five control group fellows fully used the material provided during the study period, limiting analysis across groups. Didactic training is expected to improve content knowledge more than skill-based competencies; thus, it is unsurprising that there was no difference in the knowledge outcome. The low didactic group participation rate reflects the practical difficulty of relying on self-directed didactic education during busy training years. It may be more appropriate to interpret results as a comparison of simulation-based education to the current fellowship training curriculum.

External reviewers generally felt that fellows had improved over the study time. However, their scores did not confirm a sustained increase in communication competence analogous to the increase in comfort that fellows' perceived. Lack of statistical improvement could be secondary to: lack of power for this outcome, a change in the validity of the MKCAT after adding scoring anchors that often clustered scores in the 3–4 range, short simulation time limiting fellow ability to score highly on all communication domains, and the increased difficulty of simulation #3 as compared to #1. While a different scoring scale or utilizing parents of seriously ill children could yield different results, the potential for psychological distress due to the highly emotional nature of the scenarios made this unfeasible for our parent groups.

PC consultation rate was obtained only from the four departments from which fellows participated at the simulation-based site. Consultation numbers do not include complex care, gastroenterology, genetics/metabolism, nephrology, neurology, and pulmonology. The change in consultation rate could be secondary to increased recognition of the broad PC services available, and dissemination to other team members, but correlation does not imply causation. While no other institutional interventions occurred to account for this change, the direct participation of a fellow in a decision for consultation cannot be measured. PC consultation data were not available from the control site; it is unknown whether PC consultations would have changed in a similar fashion.

Future directions

As this is pilot work, further refinement is necessary in self-reported and external measurement tools targeting pediatric patients and parents. In building a curriculum, scenario complexity can be increased by modifying the disease, participants, cultural, language, psychosocial variables, and using mixed modalities (live parent and patient mannequin). Future trials could study small educational fractions provided at more frequent intervals to assess skill retention, or evaluate patient and parent-reported outcomes (perception of fellow communication skills, rates of anxiety or depression, and frequency or timing of goals of care discussions). Finding ways to make the education less costly and more efficient will be key to its continued use. Once a curriculum leads to sustained improvements by self- and external-rating, it could be more widely disseminated through online platforms or national programs.

Conclusions

Acquisition of the cognitive and communication skills necessary to competently and compassionately deliver PC has historically been thought to occur via clinical exposure. Pediatric studies indicate that this assumption is incorrect. On-the-job experience is limited and variable in quality, leading to suboptimal communication, and unnecessary physical, psychosocial, and spiritual suffering. Despite limitations of simulation education including its lack of focus on knowledge and the need for more frequent sessions to attain better retention, this simulation-based curriculum is one method for learning PC communication skills. In addition, this training is easily adapted and scaled in complexity, thereby creating challenging and valuable learning experiences for senior trainees and experienced physicians alike.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Nancy Contro, LCSW, and the parents from the Lucile Packard Children's Hospital Stanford Palliative Care—Family Partners group for their involvement in the education component of the video, the Center for Advanced Pediatric and Perinatal Education (CAPE) staff (Julie Arafeh, Barb Beebe, and Alba Rivera) for simulation time and expertise, Vyjeyanthi (VJ) Periyakoil, MD, for palliative care mentorship, Kiruthiga Nandagopal, PhD, and Sylvia Bereknyei, PhD for medical education mentorship, Alice Whittemore, PhD and Rita Popat, PhD for statistical mentorship, Brian Greffe MD, Joanne Hilden, MD, Thomas Parker, MD, Brian Jackson, MD, and Austine Siomos, MD at the Children's Hospital Colorado, University of Colorado for assistance with recruitment, and Jenna Braverman and Jason Batten for providing external reviews to each video, for which they were compensated. This work was supported by (1) the Child Health Research Institute, Lucile Packard Foundation for Children's Health Innovations in Patient Care Grant, Stanford CTSA (UL1 RR025744/UL1 TR001085) awarded to K. Brock, which provided salary support for authors H.C., B.S., J.G., and L.P., payment for external reviewers, simulation lab support, study subject reimbursements, RedCap utilization, and video editing; (2) the KL2 component of the Stanford Clinical and Translational Science Award to Spectrum (NIH KL2 TR 001083) that provided salary, tuition, and travel stipend support to K. Brock; (3) the Rathmann Family Foundation Educators-4-CARE (E4C) Medical Education Fellowship in Patient-Centered Care through the Stanford University School of Medicine—Office of Medical Education, in conjunction with the Stanford Center for Medical Education Research and Innovation, which provided salary, technological and travel support to K. Brock, and (4) the Endowment for the CAPE, which supports the simulation lab and personnel.

Author Disclosure Statement

The other authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose and have no relevant corporate sponsors.

References

- 1.Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA: Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: A population-based study of Washington State, 1980–1997. Pediatrics 2000;106(1 Pt 2):205–209 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine: When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families—Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuhlthau K, Kahn R, Hill KS, et al. : The well-being of parental caregivers of children with activity limitations. Matern Child Health J 2010;14:155–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer EC, Ritholz MD, Burns JP, et al. : Improving the quality of end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit: Parents' priorities and recommendations. Pediatrics 2006;117:649–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meert KL, Eggly S, Pollack M, et al. : Parents' perspectives on physician-parent communication near the time of a child's death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2008;9:2–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospice and Palliative Medicine and Committee on Hospital Care: Pediatric Palliative Care and Hospice Care Commitments, Guidelines, and Recommendations. Pediatrics 2013;132:966–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine: Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Contro N, Larson J, Scofield S, et al. : Family perspectives on the quality of pediatric palliative care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002;156:14–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolarik RC, Walker G, Arnold RM: Pediatric resident education in palliative care: A needs assessment. Pediatrics 2006;117:1949–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liben S, Papadatou D, Wolfe J: Paediatric palliative care: Challenges and emerging ideas. Lancet 2008;371:852–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serwint JR, Rutherford LE, Hutton N: Personal and professional experiences of pediatric residents concerning death. J Palliat Med 2006;9:70–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michelson KN, Ryan AD, Jovanovic B, et al. : Pediatric residents' and fellows' perspectives on palliative care education. J Palliat Med 2009;12:451–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheetz MJ, Bowman MA: Pediatric palliative care: An assessment of physicians' confidence in skills, desire for training, and willingness to refer for end-of-life care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2008;25:100–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Contro NA, Larson J, Scofield S, et al. : Hospital staff and family perspectives regarding quality of pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics 2004;114:1248–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baker JN, Torkildson C, Baillargeon JG, et al. : National survey of pediatric residency program directors and residents regarding education in palliative medicine and end-of-life care. J Palliat Med 2007;10:420–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rider EA, Volkan K, Hafler JP: Pediatric residents' perceptions of communication competencies: Implications for teaching. Med Teach 2008;30:e208–e217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCabe ME, Hunt EA, Serwint JR: Pediatric residents' clinical and educational experiences with end-of-life care. Pediatrics 2008;121:e731–e737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orgel E, McCarter R, Jacobs S: A failing medical educational model: A self-assessment by physicians at all levels of training of ability and comfort to deliver bad news. J Palliat Med 2010;13:677–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levetown M, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on B: Communicating with children and families: From everyday interactions to skill in conveying distressing information. Pediatrics 2008;121:e1441–e1460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roth M, Wang D, Kim M, et al. : An assessment of the current state of palliative care education in pediatric hematology/oncology fellowship training. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2009;53:647–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.File W, Bylund CL, Kesselheim J, et al. : Do pediatric hematology/oncology (PHO) fellows receive communication training? Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014;61:502–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feraco AM, Brand SR, Mack JW, et al. : Communication skills training in pediatric oncology: Moving beyond role modeling. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2016;63:966–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kersun L, Gyi L, Morrison WE: Training in difficult conversations: A national survey of pediatric hematology-oncology and pediatric critical care physicians. J Palliat Med 2009;12:525–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Litrivis E, Singh AL, Moonian A, et al. : An assessment of end-of-life-care training: Should we consider a cross-fellowship, competency-based simulated program? J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012;34:488–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boss RD, Hutton N, Donohue PK, et al. : Neonatologist training to guide family decision making for critically ill infants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009;163:783–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schiffman JD, Chamberlain LJ, Palmer L, et al. : Introduction of a pediatric palliative care curriculum for pediatric residents. J Palliat Med 2008;11:164–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamada NK, Fuerch JH, Halamek LP: Impact of standardized communication techniques on errors during simulated neonatal resuscitation. Am J Perinatol 2016;33:385–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett SC, Finer N, Halamek LP, et al. : Implementing delivery room checklists and communication standards in a multi-neonatal ICU quality improvement collaborative. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2016;42:369–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng A, Duff J, Grant E, et al. : Simulation in paediatrics: An educational revolution. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12:465–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boulet JR, Ben-David MF, Ziv A, et al. : Using standardized patients to assess the interpersonal skills of physicians. Acad Med 1998;73(10 Suppl):S94–S96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. : Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:453–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szmuilowicz E, el-Jawahri A, Chiappetta L, et al. : Improving residents' end-of-life communication skills with a short retreat: A randomized controlled trial. J Palliat Med 2010;13:439–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freer JP, Zinnerstrom KL: The palliative medicine extended standardized patient scenario: A preliminary report. J Palliat Med 2001;4:49–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weissman DE, Ambuel B, von Gunten CF, et al. : Outcomes from a national multispecialty palliative care curriculum development project. J Palliat Med 2007;10:408–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fujimori M, Shirai Y, Asai M, et al. : Effect of communication skills training program for oncologists based on patient preferences for communication when receiving bad news: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2166–2172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warm EJ, Romer AL: Introducing end-of-life care into the University of Cincinnati Internal Medicine Residency Program. J Palliat Med 2003;6:809–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tulsky JA, Arnold RM, Alexander SC, et al. : Enhancing communication between oncologists and patients with a computer-based training program: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:593–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown CM, Lloyd EC, Swearingen CJ, et al. : Improving resident self-efficacy in pediatric palliative care through clinical simulation. J Palliat Care 2012;28:157–163 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tobler K, Grant E, Marczinski C: Evaluation of the impact of a simulation-enhanced breaking bad news workshop in pediatrics. Simul Healthc 2014;9:213–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carter BS, Swan R: Pediatric palliative care instruction for residents: An introduction to IPPC. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2012;29:375–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haut C, Michael M, Moloney-Harmon P: Implementing a program to improve pediatric and pediatric ICU nurses' knowledge of and attitudes toward palliative care. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2012;14:71–79 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lindsay J: Introducing nursing students to pediatric end-of-life issues using simulation. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2010;29:175–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baughcum AE, Gerhardt CA, Young-Saleme T, et al. : Evaluation of a pediatric palliative care educational workshop for oncology fellows. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007;49:154–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harris LL, Placencia FX, Arnold JL, et al. : A structured end-of-life curriculum for neonatal-perinatal postdoctoral fellows. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2015;32:253–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Youngblood AQ, Zinkan JL, Tofil NM, et al. : Multidisciplinary simulation in pediatric critical care: The death of a child. Crit Care Nurse 2012;32:55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bateman LB, Tofil NM, White ML, et al. : Physician communication in pediatric end-of-life care: A simulation study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2016;33:935–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gerhardt CA, Grollman JA, Baughcum AE, et al. : Longitudinal evaluation of a pediatric palliative care educational workshop for oncology fellows. J Palliat Med 2009;12:323–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brock K, Cohen H, Sourkes B, et al. :. Teaching Pediatric Fellows Palliative Care Through Simulation and Video Intervention: A Practical Guide to Implementation MedEdPORTAL Publications, Washington, DC, 2015. www.mededportal.org/publication/10284 (last accessed September2016)

- 49.Meier D: Center to Advance Palliative Care. The Human Connection of Palliative Care: Ten Steps for What To Say and Do [video]. 2013. www.youtube.com/watch?v=7kQ3PUyhmPQ (Last accessed June2015)

- 50.National Institute for Nursing Research: Pediatric Palliative Care. 2014. www.youtube.com/watch?v=lzT52wo8bQk (Last accessed June2015)

- 51.National Institute for Nursing Research: Starting a Conversation about Pediatric Palliative Care. 2014. www.youtube.com/watch?v=hKK24Bp1elQ (Last accessed June2015)

- 52.National Institute for Nursing Research: Pediatric Palliative Care: A Personal Story. 2014. www.youtube.com/watch?v=-hOBYFS_Z68 (Last accessed June2015)

- 53.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization: Pediatric Hospice Palliative Care—NHF. 2013. www.youtube.com/watch?v=xEbYbM_HY0s (Last accessed June2015)

- 54.Friedrichsdorf SJ, Kang TI: The management of pain in children with life-limiting illnesses. Pediatr Clin North Am 2007;54:645–672, x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brock KE, Cohen HJ, Popat RA, et al. : Reliability and validity of the pediatric palliative care questionnaire for measuring self-efficacy, knowledge, and adequacy of prior medical education among pediatric fellows. J Palliat Med 2015;18:842–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, et al. : Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: A systematic review. JAMA 2006;296:1094–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dickson RP, Engelberg RA, Back AL, et al. : Internal medicine trainee self-assessments of end-of-life communication skills do not predict assessments of patients, families, or clinician-evaluators. J Palliat Med 2012;15:418–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Calhoun AW, Rider EA, Meyer EC, et al. : Assessment of communication skills and self-appraisal in the simulated environment: Feasibility of multirater feedback with gap analysis. Simul Healthc 2009;4:22–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peterson EB, Calhoun AW, Rider EA: The reliability of a modified Kalamazoo Consensus Statement Checklist for assessing the communication skills of multidisciplinary clinicians in the simulated environment. Patient Educ Couns 2014;96:411–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Random Number Generator and Randomly Select a Subset of Subjects were Calculated using the GraphPad QuickCalcs Website: http://graphpad.com/quickcalcs/randomN1.cfm and http://graphpad.com/quickcalcs/randomSelect1 (Last accessed December2014)

- 61.Hallgren KA: Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: An overview and tutorial. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol 2012;8:23–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cicchetti D: Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assessment 1994;6:284–290 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dupont WD, Plummer WD, Jr.: Power and sample size calculations for studies involving linear regression. Control Clin Trials 1998;19:589–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Greenberg LW, Ochsenschlager D, O'Donnell R, et al. : Communicating bad news: A pediatric department's evaluation of a simulated intervention. Pediatrics 1999;103:1210–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Howard G, Dailey P: Response-shift bias: A source of contamination of self-report measures. J Appl Psychol 1979;64:144–150 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Davis G: Using retrospective pre-post questionnaire to determine program impact. J Extens https://www.joe.org/joe/2003August/tt4.php (last accessed April2017)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.