Abstract

The canonical mechanism of gramicidin (gA) channel formation is transmembrane dimerization of nonconducting subunits that reside in opposite bilayer leaflets. The channels do not open and close; they appear and disappear due to subunit association and dissociation. Many different types of experiments support this monomer ↔ dimer mechanism. Recently, however, this mechanism was challenged, based on experiments with lipid vesicle-incorporated gA under conditions where vesicle fusion could be controlled. In these experiments, sustained channel activity was observed long after fusion had been terminated, which led to the proposal that gA single-channel current transitions result from closed-open transitions in long-lived bilayer-spanning dimers. This proposal is at odds with 40 years of experiments, but involves the key assumption that gA monomers do not exchange between bilayers. We tested the possibility of peptide exchange between bilayers using three different types of experiments. First, we demonstrated the exchange of gA between 1,2-dierucoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DC22:1PC) or 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DC18:1PC) lipid vesicles using a fluorescence assay for gA channel activity. Second, we added gA-free DC22:1PC vesicles to both sides of planar DC18:1PC bilayers preincubated with gA, which reduced channel activity up to 10-fold. Third, we added gA-containing DC22:1PC vesicles to one or both sides of DC18:1PC planar bilayers, which produced much higher channel activity when the gA-containing vesicles were added to both sides of the bilayer, as compared to one side only. All three types of experiments show that gA subunits can exchange between lipid bilayers. The exchange of subunits between bilayers thus is firmly established, which becomes a crucial consideration with respect to the mechanism of channel formation.

Introduction

Gramicidin (gA) channels are monovalent cation-conducting channels (1). As originally predicted by Urry (2), gA channels are bilayer-spanning antiparallel dimers (3, 4, 5, 6), formed by two single-stranded, right-handed β6.3-helical subunits (7, 8, 9, 10). The channels usually are considered to form by the transmembrane dimerization of two nonconducting subunits (11) (Fig. 1 A), meaning that gA single-channel current transitions denote the appearance or disappearance of conducting dimers, not close ↔ open transitions. Recently it has been proposed, nevertheless, that the current transitions denote open ↔ close transitions in stable bilayer-spanning dimers (12) (Fig. 1 B), a suggestion that is at variance with a large body of experimental evidence.

Figure 1.

Two different proposals for gA channel formation. (A) Given here is the canonical model in which gA channels form by reversible transmembrane dimerization of two nonconducting subunits, one from each bilayer leaflet (as emphasized by the subunit coloring). (B) Given here is the model of Jones et al. (12), in which gA channels exist as dimers that can switch between nonconducting (gray) and conducting (colored) bilayer-spanning states. (In model B, the gA subunits do not dissociate, or dissociate very slowly, once two monomers join together.) To see this figure in color, go online.

That gA channels form by reversible dimerization of nonconducting subunits has been concluded based on five different lines of evidence:

-

1.

Conductance relaxations caused by a voltage-induced (13), pressure-induced (14), or photoinactivation-induced (15) shift in the distribution between nonconducting and conducting gA conformers, as well as analysis of conductance fluctuations (16), show that gA channels form by a reversible monomer ↔ dimer reaction;

-

2.

Conductance-concentration relations determined using fluorescently labeled (3) and water-soluble (4) gA analogs, and bilayer-incorporated gA (6) show that the conductance (at low [gA]) varies as [gA]2, and that all gA dimers are conducting channels (3);

-

3.

The covalently linked gA dimer, malonyl-bis-desformyl-gramicidin A (17), forms channels with lifetimes that are about two orders-of-magnitude longer than the wild-type gA (18);

-

4.

Heterodimer analysis of the number, distribution, and orientation of conducting channels formed between two chemically different gA analogs (5, 19, 20) show that gA channels are dimers; and

-

5.

The pattern of channel formation observed when two different gA analogs are added asymmetrically, to opposite sides of the bilayer, shows that gA channels form by transmembrane dimerization of nonconducting subunits (11)—and effectively excludes that the channels form by the transmembrane insertion of preformed dimers from one or the other leaflet.

Jones et al. (12) proposed an alternative model for gA channel formation, where the single-channel current transitions arise from conformational changes within stable bilayer-spanning dimers (Fig. 1 B). This model was based on experiments in which gA was incorporated into large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) that were fused with a planar bilayer over a time course of a few minutes. The gA single-channel activity was observed to commence shortly after fusion was terminated, and the channel appearance rate continued to increase over the next 10–50 min. The persistent channel activity was interpreted to imply that the recorded gA channel activity was due to conformational transitions (closed ↔ open) in stable bilayer-spanning dimers.

An alternative interpretation of the results of Jones et al. (12) is that the sustained channel activity was caused by direct transfer of gA from the source LUVs to the interrogated planar bilayer without vesicle fusion. Transfer of gA between lipid vesicles has been proposed previously based on comparisons of the ion release from lipid vesicles and the amount of gA/vesicle (21, 22), or the reduction in gA activity after the incubation of gA-containing LUVs with an excess of gA-free vesicles (23), but see (24) for an alternative view. We therefore explored further the possibility that gA is able to undergo facile transfer from one lipid bilayer to another (whether in planar bilayers or lipid vesicles). Using several independent experimental methods, we find that gA indeed exchanges readily between lipid bilayers, thus providing a mechanism to explain the sustained channel activity observed by Jones et al. (12).

Materials and Methods

Materials

1,2-dierucoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DC22:1PC) and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DC18:1PC) were from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster AL). n-Decane was >99.8% pure for gas chromatography from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The naturally occurring mixture of gramicidins A, B, and C that is produced by B. brevis was from Sigma-Aldrich. Historically, this mixture has been called gramicidin D, after R. Dubos who discovered the gramicidins (25); it contains 80–85% [Val1]gA (26). [Val1]gA (gA) was purified from the native mixture by HPLC (27). Here, we use the abbreviation “gA” for both the native mixture, used in the fluorescence quench experiments, and the HPLC-purified [Val1]gA, used in the single-channel experiments. The fluorophore, disodium salt of 8-aminonaphthalene-1,3,6-trisulfonic acid (ANTS), was from Invitrogen (Eugene, OR). All other chemicals were of the highest available purity from Sigma-Aldrich; CsCl was roasted at 500°C for 24 h before use.

Methods

Formation of large unilamellar vesicles. LUVs were formed from DC18:1PC or DC22:1PC. Four different types of LUVs were prepared (Fig. 2): type-A, which is not loaded with fluorophore and has no gramicidin incorporated into the LUV membrane (−gA, −ANTS); type-B, which is not loaded with ANTS but with gramicidin incorporated into the LUV membrane (+gA, −ANTS); type-C, which is loaded with ANTS but with no gramicidin incorporated into the LUV membrane (−gA, +ANTS); and type-D, which is loaded with fluorophore and with gramicidin incorporated into the LUV membrane (+gA, +ANTS).

Figure 2.

The four vesicle types used in this study. Types A and B are not loaded with ANTS, and therefore are invisible in the fluorescence quench experiments; types C and D are loaded with ANTS, and therefore are visible in the fluorescence quench experiments. Types A and C lack gA in the membrane; types B and D have gA incorporated into the membrane. The gramicidin-free type-A LUVs serve as sinks for the removal of gA from the ANTS-loaded gA-containing type-D LUVs. The gramicidin-containing type-B LUVs serve as donors for transfer of channels to the gA-free type-C LUVs. To see this figure in color, go online.

The lipids were dried under a nitrogen jet, and dried further in a desiccator under vacuum overnight. Before drying, the lipids used for producing type-B and -D LUVs were mixed with gA at a gramicidin/lipid molar ratio of 1:2000 (for the DC22:1PC experiments, where the gA monomer ↔ dimer equilibrium is shifted toward the nonconducting monomers) or 1:16,000 (for the DC18:1PC experiments, where the gA monomer ↔ dimer equilibrium is shifted toward the conducting dimers), to have comparable quench rates. (The LUV diameter is ∼130 nm, as determined by electron microscopy or dynamic light scattering, meaning that there are ∼150,000 phospholipids in a vesicle.) For type-A and -B LUVs, the lipid film was hydrated in 140 mM NaNO3, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.0 at room temperature overnight, and the volume was adjusted to yield a 10-mM lipid suspension (type-B also contained 5 μM gA, for the DC22:1PC experiments, or 0.6 μM gA, for the DC18:1PC experiments). For type-C and type-D, the lipid film was hydrated in 100 mM NaNO3, 25 mM ANTS (Na+ salt), 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.0 at room temperature overnight, adjusting the volume yield a 10-mM lipid suspension (type-D also contained 5 μM gA, for the DC22:1PC experiments, or 0.6 μM gA, for the DC18:1PC experiments). The lipid, or lipid-gramicidin, suspensions were sonicated in a model No. 3510 Bath Sonicator (https://www.bransonic.com/) at 90 W power for 1 min, subjected to five freeze-thaw cycles, and extruded 21 times at room temperature with a mini-extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids) using a 0.1-μm polycarbonate membrane filter. The type-C and -D suspensions were passed through a PD-10 desalting column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) to remove unencapsulated ANTS. The final lipid concentration in the LUV stock suspensions was ∼5 mM. These suspensions were stored in the dark at 12.5°C for a maximum of 7 days.

gA exchange. The exchange of gA between different bilayer membranes was explored using two different experimental approaches: exchange between lipid vesicles, using stopped-flow fluorescence quench measurements to monitor the time course of exchange; and exchange between planar bilayers and lipid vesicles using single-channel electrophysiology. All experiments were done at 25°C.

Fluorescence spectrometry. The exchange of gA between phospholipid vesicles was monitored using an SX20 Stopped-Flow Spectrofluorometer (Applied Photophysics, Leatherhead, United Kingdom) to measure the time course of Tl+-induced ANTS fluorescence quenching. Because the Tl+-induced fluorescence quenching varies as a function of the intravesicular [Tl+], the time course of fluorescence quenching becomes a measure of the time course of the changes in intravesicular [Tl+] and the initial rate of fluorescence quenching provides a measure of the initial rate of Tl+ influx into the ANTS-loaded LUVs (28, 29, 30), which will vary with changes in the number of conducting channels in the LUV membrane. It thus becomes possible to determine the time course of gramicidin exchange between different LUV preparations (the four types described above).

The experiments were done at a sampling rate of 5000 points/s and an excitation wavelength of 352 nm; the fluorescence signal was recorded above 455 nm using a high-pass filter and Pro-Data control software (Applied Photophysics). The inevitable variation in LUV sizes means that the time course of fluorescence quenching cannot be described by a single exponential decay. Rather, the time course is the sum of exponential decays with time constants, and weights, that reflect the distribution of vesicle sizes and the number of conducting channels in the vesicle membrane, and the quench rates were obtained by fitting a stretched exponential (31),

| (1) |

where F(t) and F(0) denote the fluorescence at times t and 0, respectively; τ0 is a parameter with dimensions of time; and β is a parameter that describes the deviation from the single exponential, 0 < β ≤ 1) to the fluorescence quench time course for each mixing reaction and evaluating the quench rate at 2 ms (the instrumental dead time is ∼1.5 ms):

| (2) |

For each experimental condition, the quench rate was determined from at least five repeated mixing trials, for three or more independently made LUV preparations, and normalized to the quench rate at time zero.

Single-channel electrophysiology. DC18:1PC/n-decane bilayers were formed across a 400-μm-diameter hole in a Teflon partition separated by two 2.5 mL 1.0 M CsCl (10 mM HEPES, pH 7) solutions. gA single-channel activity was recorded using a 3900 Patch-Clamp Amplifier (Dagan, Minneapolis, MN). The current signal was filtered at 1 kHz, digitized at 20 kHz, and digitally filtered at 50 Hz. The exchange of gA between planar bilayers and LUVs was monitored using two different protocols.

In the first protocol, the transfer of gA from the planar bilayer to the LUVs was monitored by adding ∼100 fM [Val1]gA, in DMSO (total DMSO concentration <0.2%, a concentration that has no effect on gA channel function (29)) to both sides of the bilayer. The electrolyte solutions were stirred for 60 s, a +100 mV potential difference was then applied, and channel activity was recorded. When channel activity had reached an apparently steady state (after ∼20 min), the aqueous solutions were stirred for 60 s to ensure maximum gA partitioning into the bilayer, then 40 μL of the electrolyte solution was added to both sides of the bilayer and the solutions were stirred for another 60 s (the Salt Control) to ensure that gA activity had reached its highest level and that addition of additional volume did not alter the channel activity. Approximately five min after the Salt Control, 40 μL of gramicidin-free DC22:1PC LUVs (type-A in Fig. 2) were added to both sides of the bilayer (to yield a final lipid concentration in the chamber of ∼80 μM), the solutions were stirred for ∼60 s and channel activity was recorded for the next 30–60 min (until the bilayer became unstable).

In the second protocol, the transfer of gA from the LUVs to the planar bilayer was monitored by adding 40 μL of gA-containing DC22:1PC LUVs (type-B in Fig. 2) to the cis side of a gA-free DC18:1PC/n-decane bilayer, with an equal amount of electrolyte solution added to the trans side (the final lipid and gramicidin concentrations in the cis chamber were ∼80 μM and 40 nM, respectively). The solutions were stirred for 60 s, a +100 mV potential was then applied and channel activity recorded. After 20 min, 40 μL of gA-containing DC22:1PC vesicles were added to the trans side of the bilayer, with an equal volume of electrolyte solution added to the cis side, and the solutions were stirred for 60 s before resuming the recording of channel activity.

Statistical analysis of single-channel experiments. To evaluate the transfer of gA into and out of planar lipid bilayers, as well as the statistical behavior of the gA channels in the planar bilayer, all-point histograms were constructed from the current traces using the software Origin 8.1 (OriginLabs, Northampton, MA). To monitor the transfer from the planar bilayer to the LUV, we examined the pattern of channel appearances after gA had been added. For every 5 min segment, the last 3 min were used to construct the all-point histogram, which was fitted with a multipeak Gaussian distribution to determine the area under each peak—corresponding to 0, 1, 2, … conducting channels; the number of channel events was determined from the single-channel current transition histograms, as the number of transition divided by 2. It thus was possible to determine the total number of channel events (ntot), the time-averaged number of conducting channels (〈n〉), and the maximum number of simultaneously conducting channels (nmax).

We then compared the distribution of the number, n, of simultaneously conducting channels with predictions based on either the Poisson distribution:

| (3) |

where P(n) is the probability of observing n simultaneously conducting channels, and μ is the average number of simultaneously conducting channels, estimated as 〈n〉, or the binomial distribution:

| (4) |

where B(n) is the probability of observing n simultaneously conducting channels, nmax is the total number of (nonconducting and conducting) channels, and p is the probability that a channel is in the conducting state, estimated as 〈n〉/nmax.

The comparison was done using χ2 tests of goodness of fit (32) for each recording period (Control, every 5 min; Salt Control, every 5 min; Vesicle Addition, every 5 min; see Fig. 9 in Results). For comparisons to the Poisson distribution, the degrees of freedom, df, was nmax − 2, where nmax denotes the maximum number of simultaneously conducting channels; for comparisons to the binomial distribution, df was nmax − 3.

Figure 9.

Evaluating models of gA channel formation using Poisson and binomial distribution fits to the data. The three panels denote the results from three different experiments where we were able to observe single-channel activity for >50 min (the current trace in Fig. 6 is from Experiment 2). For each experiment, the average number of conducting channels (〈n〉) and the maximal number of conducting channels (nmax) were determined from the current traces (e.g., Fig. 6), and the distribution of the number of conducting channels (0, 1, 2, … nmax) in each 3-min test period (the different conditions are defined in the legend to Fig. 7) was compared to predictions based on the Poisson and binomial distributions. For the binomial fits, the number of gA dimers (conducting and nonconducting) was estimated as the maximal number of observed channels, nmax and as 1.5⋅nmax (∗) or 2⋅nmax (∗∗), to account for a possible underestimate of nmax. To see this figure in color, go online.

Results

We first show the results of experiments that monitor the exchange of gA between LUVs using fluorescence quench measurements; then we show the results of experiments that monitor the exchange of gA between LUVs and planar lipid bilayers using single-channel electrophysiology.

Gramicidin can exchange between phospholipid vesicles

We used LUVs prepared from either DC22:1PC or DC18:1PC; for each lipid, we used four different types of LUVs (Fig. 2). Type-A (−gA, −ANTS) and type-B (+gA, −ANTS) LUVs are silent in the stopped-flow fluorescence measurements, contributing only background noise due to light scattering. Type-C (−gA, +ANTS) and type-D (+gA, +ANTS) LUVs are visible, but we observe Tl+ quenching of the ANTS fluorescence only in those LUVs that have gA embedded in the membrane.

To assay for gA exchange between vesicles, we mixed different vesicle types (defined in Fig. 2) at a 4:1 ratio (final total lipid concentration ∼1.25 mM) and monitored their gA activity after incubating different vesicle mixtures for times ranging from 10 min to 40 h (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

gA exchange between DC22:1PC LUVs, as monitored by changes in the time course of Tl+-induced fluorescence quenching. Four different LUV mixtures were tested; each LUV type or mixture was incubated at 25°C for the indicated period, and the fluorescence quench rates were determined using stopped-flow spectrofluorometry. The quench rates were normalized to the rates determined for the standard (type-D) LUVs after 10 min incubation; the type-C and -D LUVs served as control for membrane integrity. To monitor the removal of gA subunits, type-D (+ANTS, +gA) LUVs were incubated with type-A (−ANTS, −gA) or type-B (−ANTS, +gA) LUVs at a 1:4 ratio of D to A or B; after 10 min, there is a twofold reduction in the quench rate for the D+4A mixture, with little further change (see also Fig. 4). (The mixture of types D and B served as positive control because any exchange of gA should not affect the average number of gA subunits in type-D.) To monitor the insertion of gA subunits (and formation of gA channels), type-C (+ANTS, −gA) LUVs were incubated with type-A (−ANTS, −gA) or -B (−ANTS, +gA) LUVs at a 4:1 ratio of types C to A or B; after 16 h, there was a 25% increase in the quench rate for the C+4B mixture (see also Fig. 4). (The mixture of types A and C served as negative control, as there was no gA that could partition into type-C.) To see this figure in color, go online.

To assay for transfer of gA out of lipid bilayers, we incubated type-D LUVs (+gA, +ANTS) with type-A LUVs (−gA, −ANTS) denoted D+4A. As a negative control, we incubated type-D LUVs (+gA, +ANTS) with type-B LUVs (+gA, −ANTS) denoted D+4B. To assay for transfer of gA into lipid bilayers, we incubated type-C LUVs (−gA, +ANTS) with type-B LUVs (+gA, −ANTS), denoted C+4B. As a negative control, we incubated type-C LUVs (−gA, +ANTS) with type-A LUVs (−gA, −ANTS) denoted C+4A.

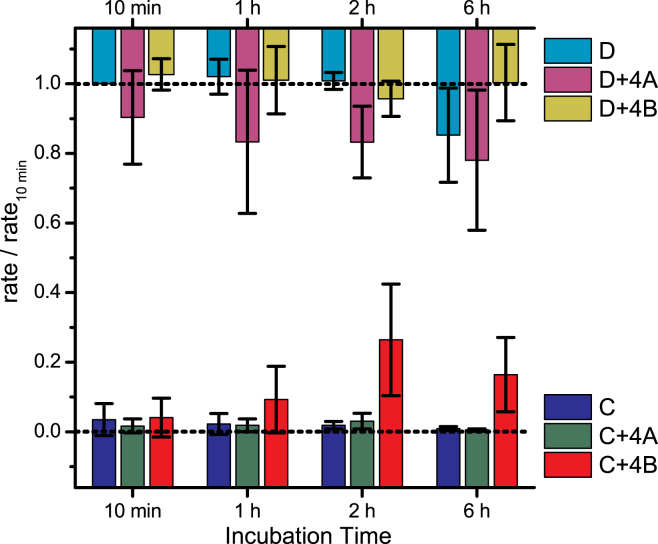

Fig. 4 shows the results for gA transfer among several combinations of lipid vesicles composed of DC22:1PC after incubating the different vesicle mixtures for 10 min, 1, 16, and 40 h, testing for efficiency gA exchange.

Figure 4.

Summary of results on gA exchange between DC22:1PC vesicles. The fluorescence quench rates, determined in experiments like those in Fig. 3, were normalized to the rates determined for the standard vesicle (type-D) after 10 min incubation, where the average quench rate was 37 ± 10 s–1, mean ± SD (n = 5). For the experiments in the top row, the D+4A mixture monitors the removal of gA subunits (bilayer-spanning channels) from type-D LUVs. The D+4B mixture served as positive control, and type-D by itself serves as control for membrane integrity. For the experiments in the bottom row, the C+4B mixture monitors the insertion of bilayer-spanning gA channels into type-C LUVs, and the C+4A mixture served as a negative control. Mean ± SD (n = 3–5) except 40 h D+4B, which is mean ± range/2 (n = 2). To see this figure in color, go online.

gA extraction from type-D to type-A occurs relatively quickly. By 10 min, the quench rate had decreased by >50%, relative to the control type-D LUVs, continued to decrease slightly over the next hour, and then was stable up to 40 h. There was no decrease in the quench rate in the D+4B experiment, and we conclude that gA exchanges readily between the outer leaflets of phospholipid vesicles.

In contrast to these results, there was little increase in the quench rate over the first hour in the C+4B experiment; at 16 and 40 h, the quench rate was about one-third of the control rate observed with the control, type-D, LUVs. There was no increase in the quench rate in the C+4A experiment.

This asymmetry between the time course of the decrease in quench rates in the extraction experiments and the increase in quench rates in the insertion experiments reflects the asymmetry between gA channel disappearances and appearances. In the extraction (D+4A) experiments, the number of conducting channels (in the type-D LUVs) decreases as gA monomers are extracted from the outer vesicle leaflets, meaning that the time course of the reduction in the quench rate will be similar to the time course of extraction of gA from the vesicles. In the insertion (C+4B) experiments, the formation of conducting channels (in the type-C vesicles) requires two steps: first, the insertion of gA monomers into the outer leaflet; and second, the transfer of gA from the outer to the inner leaflet, a process that is known to be slow (11). The results in Fig. 4 are consistent with such a two-step process for channel formation.

When testing for exchange of gA between DC18:1PC (Fig. 5), the quench rates in the D+4A experiments decreased much more slowly than in the DC22:1PC experiments; at 10 min, we observed only a 10% reduction in the quench rate; at 1, 2, and 6 h, the quench rate was reduced ∼20%. (The experiments were not continued for longer times because the vesicles began to become unstable after 6 h, as evidenced by the quench rates observed with the type-D vesicles alone.) Again, there was no reduction in quench rate in the D+4B experiments. In the insertion experiments, the quench rates increased with a similar time course as the decrease observed in the extraction experiments, suggesting that the transfer of gA across DC18:1PC bilayers is faster than the transfer across DC22:1PC bilayers.

Figure 5.

Summary of results on gA exchange between DC18:1PC vesicles. The fluorescence quench rates, determined in experiments similar to those in Fig. 3 but with DC18:1PC LUVs, were normalized to the rates determined for the standard vesicle (type-D) after 10 min incubation, where the average quench rate was 89 ± 15 s–1, mean ± SD (n = 8). For the experiments in the top row, the D+4A mixture monitors the removal of gA subunits (bilayer-spanning channels) from type-D LUVs. The D+4B mixture served as positive control, and type-D by itself serves as control for membrane integrity. For the experiments in the bottom row, the C+4B mixture monitors the insertion of bilayer-spanning gA channels into type-C LUVs, and the C+4A mixture served as a negative control. Mean ≥ SD (n = 3–6) except for the 2 h experiments, which is mean ± range/2 (n = 2). To see this figure in color, go online.

Gramicidin can exchange between phospholipid vesicles and planar lipid bilayers

We also explored whether gA can exchange between lipid vesicles and planar bilayers using single-channel electrophysiology on planar lipid DC18:1PC/n-decane bilayers that had or had not been doped with gA. DC22:1PC LUVs were used as transfer vehicles to extract or insert gA from the cis or trans side of the planar bilayer, and the gA channel activity was recorded.

gA monomers can be extracted from planar lipid bilayers using lipid vesicles

To monitor whether gA can be extracted from the bilayer (Fig. 6), gA was first added to the aqueous phase (1.0 M CsCl, unbuffered) on both sides of the bilayer, which led to the expected increase in channel activity for 10–20 min, at which time the gA channel activity (time-averaged number of channels in the membrane) reached an apparent equilibrium.

Figure 6.

Extraction of gA subunits from planar lipid bilayers using gA-free vesicles. Current traces were recorded from a planar DC18:1PC/n-decane bilayer that had been doped with 100 fM gA, added through the aqueous phase, which had been stirred for 60 s, and gA channel activity was monitored. Over the first 15 min (after gA addition), channel activity increased to reach an apparent equilibrium, where the average number of conducting channels was 2.4. The aqueous phases then were stirred for one min, which caused some membrane instability (periods of membrane instability are denoted by the gray box; they were not included in the analysis) but no further increase in channel activity. After 25 min, 40 μL 1.0 M CsCl was added to both aqueous phases, as control for the later addition of lipid vesicles, and the solutions were stirred for 60 s (indicated by solid box), which led to minimal change in channel activity; the average number of conducting channels after 5 min was 2.2. Then 40 μL of gA-free DC22:1PC lipid vesicles (type-A) were added to both sides of the bilayer, to a final lipid concentration of 80 μM in the aqueous phases, which were stirred for 60 s (again indicated by solid box), and channel activity was monitored over the next 70 min (only the first 30 min was used for analysis). The current trace fragments below the trace show segments at higher time resolution, sampled at the locations indicated by (∗) below the time axis for the main trace. 1.0 M CsCl, 100 mV.

To ascertain whether gA incorporation into the bilayer had reached its maximum, the solution was stirred for 1 min, which led to minimal changes in channel activity (Control). Then 40 μL 1.0 M CsCl was added to the aqueous phases (2.5 mL, on each side of the bilayer) and the solutions were stirred for 60 s, which led to minimal changes in channel activity (Salt Control). Then 40 μL of a DC22:1PC-LUV-containing solution was added to both sides of the bilayer, the solutions were stirred for 60 s, and the channel activity was recorded for 20 min or longer (until the membrane became unstable). The addition of gA-free LUVs led to a reduction in channel activity; by 20 min, the average number of conducting channels had decreased to 20% of the activity before vesicle addition. (In the absence of vesicles, the number of conducting channels varies little after the steady state has been reached, e.g., see the first 30 min in the current trace in Fig. 6.) Fig. 7 summarizes results for this experiment plus two others where channel activity could be monitored for >45 min.

Figure 7.

gA single-channel activity in planar DC18:1PC/n-decane bilayers before and after addition of gA-free DC22:1PC vesicles. The average number of conducting channels over consecutive observation periods was determined from single-channel current traces, like Fig. 6. Each data point denotes the average number of conducting gA channels observed over 3 min, normalized to the maximum number (nmax) observed in the particular current trace (10–15 min after gA addition). The three stages in the experiments were: Control, after gA addition but before any manipulation; Salt Control, where first the aqueous phases were stirred for 60 s to test whether the system had reached apparent equilibrium, followed by the addition of 40 μL electrolyte to the aqueous phase on each side of the bilayer, then stirred for 60 s and channel activity was determined; and Vesicle Addition, where gA-free DC22:1PC vesicles were added to both sides of the bilayer to a final lipid concentration (in the aqueous phases) of 80 μM and the solutions were stirred for 60 s and channel activity was monitored. 1.0 M CsCl, 100 mV. Mean ± SD (n = 3).

gA monomers can be transferred into planar lipid bilayers from lipid vesicles

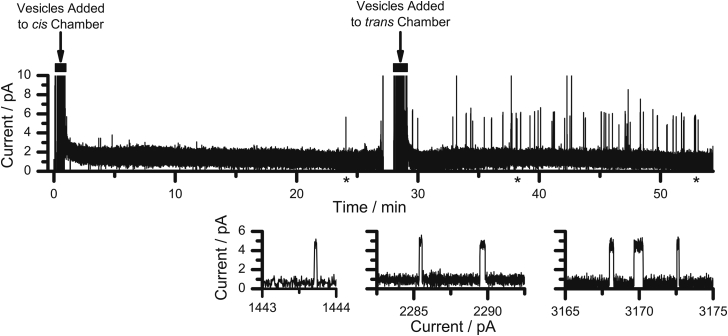

To monitor whether gA can be inserted into planar lipid bilayers from lipid vesicles, we first added 40 μL of gA-containing DC22:1PC vesicles (type-D; see Fig. 2) to the cis side of a gA-free DC18:1PC/n-decane bilayer. (We chose DC22:1PC vesicles because of the relatively fast extraction of gA from DC22:1PC vesicles in the experiments with LUVs; see Figs. 3 and 4.) The aqueous phases were stirred for 60 s, and there was minimal gA channel activity over the next 30 min (Fig. 8, first half of trace). When an equal amount of gA-containing vesicles was added to the trans chamber, followed by stirring for 60 s, gA channel activity was observed within a few min (Fig. 8, second half of trace). Similar results were obtained in two additional experiments where single-channel channel activity could be recorded for >50 min.

Figure 8.

Insertion of gA subunits into planar lipid bilayers from gA-containing DC22:1PC vesicles. In the first half of the trace, lasting 27 min, DC22:1PC vesicles (80 μM lipid, 40 nM gA) were added only to the cis chamber, the aqueous phases were stirred for 60 s (indicated by a solid box), and channel activity was recorded. There is only one identifiable channel event (marked by (∗) below the time axis for the main trace) after 24 min of recording, which is shown at higher resolution in the first of the three currents in the bottom of the figure. Then the same amount of gA-containing DC22:1PC vesicles were added to the trans chamber, the solutions were stirred for 60 s (again indicated by a solid box), and gA channel activity was observed. The second and third current trace fragments below the trace show segments at higher time resolution, sampled at the locations indicated by (∗) below the time axis for the main trace. 1.0 M CsCl, 100 mV.

gA channel activity is described by the Poisson distribution

The two gating schemes in Fig. 1 predict different distributions of gA channel appearances. In the canonical model (Fig. 1 A), a large number of nonconducting subunits that have a low probability of forming conducting dimers, and the distribution of the number of conducting gA channels, should be described by the Poisson distribution, as was found by Hladky and Haydon (33) (see also (34)). In the intrinsic gating model (Fig. 1 B), a small number of bilayer-spanning dimers exist in either conducting or nonconducting states, and the distribution of the number of conducting gA channels should be described by the binomial distribution.

We evaluated whether the distribution of the number of conducting gA channels was described better by the Poisson or binomial distribution for three single-channel experiments (one of which, Experiment 2, is shown in Fig. 6); see Materials and Methods. In all three experiments, the Poisson distribution produced better fits than the binomial distribution as evaluated using the χ2-goodness fit tests (Fig. 9). A few trials—Vesicle 15–18 min in Experiment 1 (Fig. 9; TOP), and Control 5–8 min, Control 10–13 min, and Vesicle 15–18 min in Experiment 3 (Fig. 9; BOTTOM)—were better described by the binomial distribution, although the numbers of channel events in the vesicle experiments were very low. Fits of the binomial distribution to the results depend on the total number of (conducting and nonconducting) channels in the membrane, which may have been underestimated. We therefore repeated the tests using a total number of channels in the membrane that was 50 or 100% higher than the observed nmax (Binomial∗ and Binomial∗∗, respectively, in Fig. 9), which did not alter the key conclusion—that the Poisson distribution provides the better fit to the observed distributions.

Discussion

The linear gramicidins are among the most hydrophobic naturally occurring peptides (35) with very low aqueous solubility (21, 36), which could suggest that they exchange poorly, if at all, between lipid bilayer membranes. The experimental evidence is mixed, however; Clement and Gould (24) concluded that gA did not exchange between lipid vesicles, whereas Kemp and Wenner (21), Bruggemann and Kayalar (22), and Rokitskaya et al. (23) concluded that gA most likely is able to exchange between lipid bilayers, although definitive proof was lacking.

In this study, we show that gA exchanges between lipid bilayers, a result that provides important constraints on models for the gramicidin channel current transitions. We further show that the distribution of gA single-channel appearances is better predicted by Poisson statistics than binomial statistics, consistent with the canonical mechanism for gA channel formation. We first discuss our results on the exchange of gA between LUVs, which provide further evidence that the Trp-rich carboxyethanolamide end of β6.3-helical gA channels anchors the subunits to the bilayer/solution interface. We then discuss the exchange of gA between LUVs and planar lipid bilayers, and the statistical distribution of channel appearances.

The linear gramicidins exchange between unilamellar lipid vesicles

We have shown that gA subunits exchange between lipid vesicles by monitoring the decrease in fluorescence quench rates when ANTS-loaded LUVs with membrane-incorporated gA (type-D) are mixed with ANTS- and gA-free LUVs (type-A), and the increase in quench rate when ANTS-loaded, gA-free LUVs (type-C) are mixed with ANTS-free LUVs with membrane-incorporated gA (type-B).

The interbilayer exchange of the hydrophobic gA is reminiscent of the exchange of cholesterol and phospholipids between lipid vesicles (37), and the reversible partitioning of amphipathic peptides into lipid vesicles (e.g., Schwarz and Beschiaschvili (38)) implies that there may be interbilayer transfer of amphipathic peptides. But, apart from the studies of Mazzuca et al. (39) and Rokitskaya et al. (23), we are not aware of studies that explicitly probed the exchange of peptides between vesicles, and Rokitskaya et al. concluded that “the binding of gA to liposomes [is] … practically irreversible due to its high hydrophobicity.”

When assaying for gA extraction from DC22:1PC vesicles using the D+4A mixture, the quench rate had decreased by >50% within 10 min. In contrast, assaying for gA insertion into DC22:1PC vesicles using the C+4B mixture, there was little or no increase in quench rate over the first 1 h, and the quench rate had increased to only ∼40% of the control rate in type-D vesicles after 40 h. The asymmetry between the decrease in quench rate in the former experiment and the increase in quench rate in the latter experiment shows that the rate-limiting step in the transfer of gA channels between different vesicle populations is the translocation of gA subunits across the vesicle membrane, which is necessary for forming the conducting channel by transmembrane dimerization (11).

The exchange of gA between DC18:1PC LUVs displayed more variability than in the DC22:1PC LUVs, which likely is due to the lower gA/lipid molar ratios (1:16,000 in DC18:1PC LUVs versus 1:2000 in DC22:1PC LUVs—meaning that there are, on average, only ∼10 gA monomers per DC18:1PC LUV, compared to ∼75 monomers per DC22:1PC LUV). Nevertheless, the results show that the decrease in quench rate is slower for the DC18:1PC LUVs vesicle transfer than with the DC22:1PC LUVs. (Due to the energetic cost of dimerization, a greater surplus of inactive gA monomers is needed to maintain the same number of conducting channels in the thicker DC22:1PC LUVs, as compared to the thinner DC18:1PC LUVs.)

gA is conformationally polymorphic in DC22:1PC bilayers

The difference in the time course of the decrease in quench rate in the DC18:1PC and DC22:1PC is striking, but is most likely a simple consequence of the different conformational preferences of gA in the two membrane environments (with different hydrophobic thicknesses). In the thinner DC18:1PC bilayer, there will be little hydrophobic mismatch between the dimeric gA channels and the host bilayer. The gA monomer ↔ monomer equilibrium therefore will be shifted toward the conducting, single-stranded β6.3 dimers, where the Trp residues at the carboxyethanolamide terminus of the subunit in the inner leaflet will anchor the subunit and slow the rate of extraction from the vesicle. In the thicker DC22:1PC bilayer, the hydrophobic mismatch between the dimeric gA channels and the host bilayer is greater, and the gA monomer ↔ monomer equilibrium will be shifted toward the nonconducting monomers, which would be expected to exchange faster than the bilayer-spanning dimers. The greater hydrophobic mismatch in DC22:1PC also leads to a shift toward double-stranded dimers (40, 41). This conformational polymorphism may explain why several conformers are observed in solid-state NMR experiments in DC22:1PC (42); it may also contribute toward the more rapid exchange observed in DC22:1PC LUVs.

The linear gramicidins exchange between unilamellar lipid vesicles and planar lipid bilayers

We also explored whether gA is able to exchange between lipid vesicles and planar lipid bilayers, the system used by Jones et al. (12). We found that gA can move from planar lipid bilayers to gA-free DC22:1PC LUVs (Figs. 6 and 7), and from DC22:1PC LUVs to planar lipid bilayers (Fig. 8). In the latter experiments, there was little channel activity if the gA-containing LUVs were added to only one side, but channel activity was readily detectable after addition of gA-containing LUVs to both sides of the bilayer, consistent with a slow transmembrane transfer of gA. These results are consistent with the slow increase in quench rate in the fluorescence quench experiments that monitored the insertion of gA into LUVs, as well as single-channel experiments that demonstrated slow transfer of gA across lipid bilayers (11, 43, 44).

gA single-channel activity is better described by Poisson than by binomial statistics

Previous experiments (33, 45) have shown that gA channel activity in planar lipid bilayer experiments is well described by the Poisson distribution, which suggests the bilayers host a large number of nonconducting gA monomers with a low probability of forming channels. In the model proposed by Jones et al. (12), there would be only a small number of channels in the interrogated bilayer, in which case the distribution of conducting channels should be predicted better by the binomial distribution. We therefore tested whether the distribution of conducting channels (0, 1, 2, ⋅⋅⋅) was described better by the Poisson distribution or the binomial distribution. This analysis (Fig. 9) shows that our results are described better by the Poisson distribution.

This result is not surprising because single-channel experiments are done at gA/lipid molar ratios of ∼10−8–10−6, depending on the area of the bilayer that is studied, or ∼100 gA monomers in each leaflet of the planar membrane (20, 46). The ratio between the total number of gA subunits and the number of conducting channels thus is 10−3–10−2, which a priori suggests that the channels should obey Poisson statistics. Further support for this argument is that the recombination probability in two dimensions is one (47, 48). That is, even if the area density of gA subunits in a bilayer is very low, any two subunits that form a channel and then dissociate will eventually recombine (to form a channel).

Implications for gA channel formation

Our experiments do not directly probe the mechanism underlying gA single-channel current transitions, but the demonstration that gA exchanges between lipid bilayers, at timescales relevant for the experiments of Jones et al. (12), together with the mathematical truism that the two subunits in a dissociating dimer will recombine at some later time (47, 48), invalidates two key assumptions made by Jones et al. (12) when they proposed their model. Taken together with the numerous experiments with the canonical transmembrane dimerization mechanism, summarized in the Introduction, we conclude that the predominant mechanism for gA channel formation is by transmembrane dimerization of nonconducting monomeric subunits.

We cannot, however, account for one set of experiments in Jones at al. (12) that employed the wild-type [Val1]gA and a Trp → Phe-substituted gA analog [Phe9,11,13,15]gA (denoted gM (49)), which was separately incorporated into LUVs that then were fused to planar lipid bilayers. One would expect that these gA analogs would form both homodimeric and heterodimeric channels (19, 20, 50), but Jones et al. (12) observed only two resolvable conductance peaks, corresponding to the [Val1]gA/[Val1]gA and gM/gM homodimers, a result that we, with randomly mixed subunits, only observe when the two gA analogs have different handedness (e.g., Koeppe II et al. (50)). But the more hydrophobic gM may not exchange with the same ease as gA, in which case the insertion of gM subunits could be limited by vesicle fusion; this may lead to slower mixing of the gA and gM subunits.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that gA exchanges freely between lipid bilayers (whether between pairs of lipid vesicles or between a lipid vesicle and a planar bilayer), but crosses a lipid bilayer leaflet slowly. Although our experiments do not directly probe the mechanism of gramicidin channel formation, our results do not support the internal gating model proposed by Jones et al. (12), but are fully consistent with more than 40 years of experimental studies in support of the canonical model for gA channel formation—by transmembrane dimerization of nonconducting subunits.

Author Contributions

K.L., H.I.I., R.E.K., and O.S.A. designed the experiments and planned the analysis. K.L. and H.I.I. did the fluorescence experiments. K.L. did the electrophysiology experiments. K.L. and H.I.I. did the data analysis. K.L., H.I.I., R.E.K., and O.S.A. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Thasin Peyear for assistance with the dynamic light scattering experiments, and Ruchi Kapoor, Radda Rusinova, and R. Lea Sanford for stimulating discussions.

Research reported in this article was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award No. R01GM021342 and American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) Supplement No. GM021342-35S1 (to O.S.A.).

Editor: Joseph Mindell.

Footnotes

Kevin Lum and Helgi I. Ingólfsson contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Hladky S.B., Haydon D.A. Discreteness of conductance change in bimolecular lipid membranes in the presence of certain antibiotics. Nature. 1970;225:451–453. doi: 10.1038/225451a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Urry D.W. The gramicidin A transmembrane channel: a proposed π(L,D) helix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1971;68:672–676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.3.672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veatch W.R., Mathies R., Stryer L. Simultaneous fluorescence and conductance studies of planar bilayer membranes containing a highly active and fluorescent analog of gramicidin A. J. Mol. Biol. 1975;99:75–92. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apell H.J., Bamberg E., Läuger P. Formation of ion channels by a negatively charged analog of gramicidin A. J. Membr. Biol. 1977;31:171–188. doi: 10.1007/BF01869403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cifu A.S., Koeppe R.E., II, Andersen O.S. On the supramolecular organization of gramicidin channels. The elementary conducting unit is a dimer. Biophys. J. 1992;61:189–203. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81826-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogt T.C.B., Killian J.A., Andersen O.S. Influence of acylation on the channel characteristics of gramicidin A. Biochemistry. 1992;31:7320–7324. doi: 10.1021/bi00147a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arseniev A.S., Barsukov I.L., Ovchinnikov YuA. 1H-NMR study of gramicidin A transmembrane ion channel. Head-to-head right-handed, single-stranded helices. FEBS Lett. 1985;186:168–174. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)80702-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ketchem R., Roux B., Cross T. High-resolution polypeptide structure in a lamellar phase lipid environment from solid state NMR derived orientational constraints. Structure. 1997;5:1655–1669. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Townsley L.E., Tucker W.A., Hinton J.F. Structures of gramicidins A, B, and C incorporated into sodium dodecyl sulfate micelles. Biochemistry. 2001;40:11676–11686. doi: 10.1021/bi010942w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen T.W., Andersen O.S., Roux B. Structure of gramicidin a in a lipid bilayer environment determined using molecular dynamics simulations and solid-state NMR data. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:9868–9877. doi: 10.1021/ja029317k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Connell A.M., Koeppe R.E., 2nd, Andersen O.S. Kinetics of gramicidin channel formation in lipid bilayers: transmembrane monomer association. Science. 1990;250:1256–1259. doi: 10.1126/science.1700867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones T.L., Fu R., Busath D.D. Gramicidin channels are internally gated. Biophys. J. 2010;98:1486–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bamberg E., Läuger P. Channel formation kinetics of gramicidin A in lipid bilayer membranes. J. Membr. Biol. 1973;11:177–194. doi: 10.1007/BF01869820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hickok N.J., Kustin K., Veatch W. Relaxation spectra of gramicidin dimerization in a lipid bilayer membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1986;858:99–106. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(86)90295-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rokitskaya T.I., Antonenko Y.N., Kotova E.A. Photodynamic inactivation of gramicidin channels: a flash-photolysis study. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1996;1275:221–226. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(96)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zingsheim H.P., Neher E. The equivalence of fluctuation analysis and chemical relaxation measurements: a kinetic study of ion pore formation in thin lipid membranes. Biophys. Chem. 1974;2:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(74)80045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Urry D.W., Goodall M.C., Mayers D.F. The gramicidin A transmembrane channel: characteristics of head-to-head dimerized (L,D) helices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1971;68:1907–1911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.8.1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bamberg E., Janko K. The action of a carbonsuboxide dimerized gramicidin A on lipid bilayer membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1977;465:486–499. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(77)90267-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veatch W., Stryer L. The dimeric nature of the gramicidin A transmembrane channel: conductance and fluorescence energy transfer studies of hybrid channels. J. Mol. Biol. 1977;113:89–102. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durkin J.T., Koeppe R.E.I., II, Andersen O.S. Energetics of gramicidin hybrid channel formation as a test for structural equivalence. Side-chain substitutions in the native sequence. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;211:221–234. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90022-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kemp G., Wenner C. Solution, interfacial, and membrane properties of gramicidin A. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1976;176:547–555. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(76)90198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruggemann E.P., Kayalar C. Determination of the molecularity of the colicin E1 channel by stopped-flow ion flux kinetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:4273–4276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.12.4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rokitskaya T.I., Kotova E.A., Novikova O.D. Single channel activity of OmpF-like porin from Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1858:883–891. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clement N.R., Gould J.M. Kinetics for development of gramicidin-induced ion permeability in unilamellar phospholipid vesicles. Biochemistry. 1981;20:1544–1548. doi: 10.1021/bi00509a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dubos R.J. Studies on a bactericidal agent extracted from a soil bacillus: I. Preparation of the agent. Its activity in vitro. J. Exp. Med. 1939;70:1–10. doi: 10.1084/jem.70.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abo-Riziq A., Crews B.O., de Vries M.S. Spectroscopy of isolated gramicidin peptides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2006;45:5166–5169. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greathouse D.V., Koeppe R.E., II, Andersen O.S. Design and characterization of gramicidin channels. Methods Enzymol. 1999;294:525–550. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)94031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore H.P., Raftery M.A. Direct spectroscopic studies of cation translocation by Torpedo acetylcholine receptor on a time scale of physiological relevance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1980;77:4509–4513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.8.4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ingólfsson H.I., Andersen O.S. Screening for small molecules’ bilayer-modifying potential using a gramicidin-based fluorescence assay. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2010;8:427–436. doi: 10.1089/adt.2009.0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ingólfsson H.I., Sanford R.L., Andersen O.S. Gramicidin-based fluorescence assay; for determining small molecules potential for modifying lipid bilayer properties. J. Vis. Exp. 2010:2131. doi: 10.3791/2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berberan-Santos M., Bodunov E., Valeur B. Mathematical functions for the analysis of luminescence decays with underlying distributions 1. Kohlrausch decay function (stretched exponential) Chem. Phys. 2005;315:171–182. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snedecor G.W., Cochran W.G. 8th Ed. Blackwell; Ames, IA: 1989. Statistical Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hladky S.B., Haydon D.A. Ion transfer across lipid membranes in the presence of gramicidin A. I. Studies of the unit conductance channel. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1972;274:294–312. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(72)90178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andersen O.S., Finkelstein A., Cass A. Effect of phloretin on the permeability of thin lipid membranes. J. Gen. Physiol. 1976;67:749–771. doi: 10.1085/jgp.67.6.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Segrest J.P., Feldmann R.J. Membrane proteins: amino acid sequence and membrane penetration. J. Mol. Biol. 1974;87:853–858. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haydon D.A., Hladky S.B. Ion transport across thin lipid membranes: a critical discussion of mechanisms in selected systems. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1972;5:187–282. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500000883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McLean L.R., Phillips M.C. Mechanism of cholesterol and phosphatidylcholine exchange or transfer between unilamellar vesicles. Biochemistry. 1981;20:2893–2900. doi: 10.1021/bi00513a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwarz G., Beschiaschvili G. Thermodynamic and kinetic studies on the association of melittin with a phospholipid bilayer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1989;979:82–90. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(89)90526-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mazzuca C., Orioni B., Stella L. Fluctuations and the rate-limiting step of peptide-induced membrane leakage. Biophys. J. 2010;99:1791–1800. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mobashery N., Nielsen C., Andersen O.S. The conformational preference of gramicidin channels is a function of lipid bilayer thickness. FEBS Lett. 1997;412:15–20. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00709-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Galbraith T.P., Wallace B.A. Phospholipid chain length alters the equilibrium between pore and channel forms of gramicidin. Faraday Discuss. 1998;111:159–164. doi: 10.1039/a808270g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mo Y., Cross T.A., Nerdal W. Structural restraints and heterogeneous orientation of the gramicidin A channel closed state in lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 2004;86:2837–2845. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74336-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Girshman J., Greathouse D.V., Andersen O.S. Gramicidin channels in phospholipid bilayers with unsaturated acyl chains. Biophys. J. 1997;73:1310–1319. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78164-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gu H., Lum K., Koeppe R.E., 2nd The membrane interface dictates different anchor roles for “inner pair” and “outer pair” tryptophan indole rings in gramicidin A channels. Biochemistry. 2011;50:4855–4866. doi: 10.1021/bi200136e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andersen O.S. Ion transport through simple membranes. In: Giebisch G.H., Purcel E.F., editors. Renal Function. The Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation; New York: 1978. pp. 71–99. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sawyer D.B., Koeppe R.E., II, Andersen O.S. Gramicidin single-channel properties show no solvent-history dependence. Biophys. J. 1990;57:515–523. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82567-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pólya G. Über eine aufgabe der wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung betreffend die Irrfahrt im straßennetz. Math. Ann. 1921;84:149–160. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adam G., Delbrück M. Reduction of dimensionality in biological diffusion processes. In: Davidson N., Rich A., editors. Structural Chemistry and Molecular Biology. W. H. Freeman; San Francisco, CA: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heitz F., Spach G., Trudelle Y. Single channels of 9, 11, 13, 15-destryptophyl-phenylalanyl-gramicidin A. Biophys. J. 1982;40:87–89. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(82)84462-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koeppe R.E., II, Providence L.L., Andersen O.S. On the helix sense of gramicidin A single channels. Proteins. 1992;12:49–62. doi: 10.1002/prot.340120107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]