Abstract

Background

This study examined the use of psychosocial services (i.e. social work, psychiatric, psychological, and spiritual/pastoral services) among Latina and Non-Latina White breast cancer survivors.

Methods

Survivors who received treatment in a Comprehensive Cancer Center in New York completed a mailed questionnaire about interest in help for distress, and psychosocial service use. Descriptive and non-parametric statistics were used to explore ethnic differences in use of, and interest in, psychosocial services.

Results

Thirty three percent of breast cancer survivors reported needing mental health or psychosocial services after their cancer diagnosis (33% Latinas, 34% Whites); 34% of survivors discussed with their oncologist or cancer care provider their emotional problems or needs after the diagnosis (30% Latinas, 36% Whites). Only 40% of the survivors who reported needing services received a referral for psychosocial services (42% Latinas, 39% Whites). Sixty six percent of survivors who reported needing services had contact with a counselor or mental health professional (psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker) after their diagnosis (57% Latinas, 71% Whites), and 61% of those needing services reported receiving psychosocial services (53% Latinas, 67% Whites). Whites were significantly more likely than Latinas to have contact with a social worker (33% vs. 17%, respectively) and to receive psychotropic medication (15% vs. 0%, respectively). However, Latinas were significantly more likely to receive spiritual counseling than Whites (11% vs. 3%, respectively).

Conclusion

Our study revealed gaps for both groups; however, the gaps differed by group. It is crucial to study and address potential differences in the psychosocial services availability, acceptability and help-seeking behaviors of ethnically diverse cancer patients and survivors.

Keywords: Latinas, Healthcare Disparities, Minority Health, Psychosocial services, Depression

Introduction

A diagnosis of cancer has a significant impact on the psychosocial milieu of patients. Some studies report depression rates of up to 58% among cancer patients (Massie 2004) and 19% of patients with clinical levels of anxiety (Linden et al. 2012). In 2010, 20% of the 1.5 million Americans who were diagnosed with cancer belonged to an ethnic minority group (U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group 2013). Further, near 126,000 new cases of cancer among Latinos were diagnosed in 2015 (American Cancer Society 2015). A body of literature has shown that Latinos have poorer psychological outcomes when compared to other ethno-cultural groups (Luckett et al. 2011, Yanez, Thompson, and Stanton 2011). Latina breast cancer patients report almost twice the rate of depressive symptoms (Eversley et al. 2005), and report poorer mental health than non-Latino whites (Bowen et al. 2007), while Latinos with prostate cancer report lower health related quality of life (QOL) (Krupski et al. 2005) than do non-Hispanic white and African-American patients. Furthermore, Latinos with varied cancer diagnoses have high rates of clinically significant depression and significant rates of depression recurrence after 24 months (Ell et al. 2011). It is alarming that even though Latino cancer patients are at higher risk for poor mental health outcomes, they are less likely than non-Latino whites to receive psychological and psychiatric services, and other psychosocial interventions (Luckett et al. 2011). This is likely due to mental illness stigma, limitations imposed by language differences and acculturation levels (Acosta 1979, August et al. 2011), lack of insurance or underinsurance (Carson, Le Cook, and Alegria 2010), and discrimination (Finch, Kolody, and Vega 2000), among other reasons.

Culture, language, and income are commonly acknowledged sociodemographic factors that influence quality of care and optimal distress screening (Mitchell, Vahabzadeh, and Magruder 2011). Distress management in ethnic minority cancer patients presents unique patient-, provider- and system-related barriers and challenges. A discussion of mental health concerns with a healthcare professional after the cancer diagnosis and being of white ethnicity have been identified as the strongest predictors of receipt of mental health services (Kadan-Lottick et al. 2005). Ell and colleagues (Ell et al. 2005), found in their study of ethnic minority women with cancer that 24% reported moderate to severe levels of depressive disorder, but only 12% of women meeting criteria for major depression reported receiving medications for depression, and only 5% of such women reported seeing a counselor or participating in a cancer support group. Among severely depressed ethnic minority patients, only between 2–6% were receiving counseling and/or antidepressants (Ell et al. 2005).

Starting in 2015, the Commission on Cancer, which accredits the centers that treat almost 70% of all new cancers diagnosed in the US, has required providers to evaluate patients for distress and refer them to programs for help (Commission on Cancer 2012). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), has published guidelines to screen, evaluate and refer patients to psychosocial services, which include mental health, social work and/or spiritual/chaplaincy services (National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2003). However, little research has been conducted to document the prevalence of psychosocial distress and its management in ethnic minority and other ethno-cultural or linguistic groups.

This study examines differences by Latina versus non-Latina white ethnicity in the use of psychosocial services by breast cancer survivors. We explore differences in patients’ receipt of services before and after their cancer diagnosis, and their current use of, and interest in, psychosocial services. This study seeks to identify important factors ranging from ethnicity, education, language, and literacy that may contribute to health disparities and discrepancies in patient satisfaction in order to help address these disparities.

Methods

Procedures and Participants

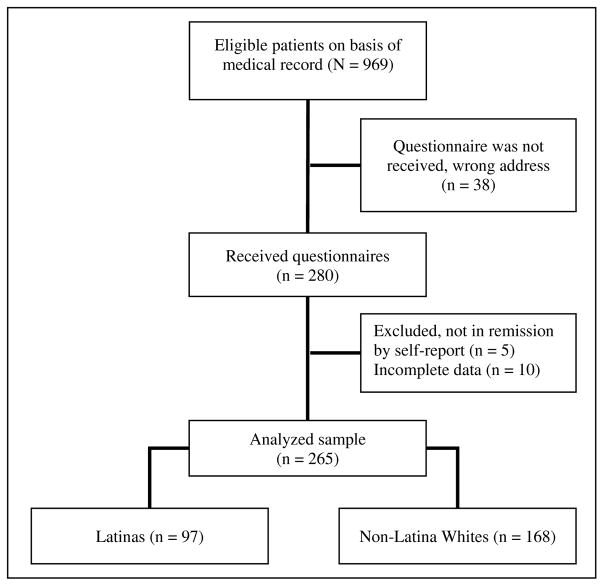

A comprehensive review of medical records in an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center in New York City revealed 409 Latina and 5146 non-Latina White patients who had been treated during 2009–2014 and who were considered to be in remission. A random sample of 10% of the non-Latina whites and all 409 of the Latinas were selected for this study. A questionnaire packet was mailed to the 409 Latina and 514 non-Latina White eligible breast cancer survivors. The Latina patients received two versions of the questionnaire, one in English and one in Spanish. Instructions were included asking patients to choose the questionnaire of their preferred language. All patients who preferred Spanish completed the questionnaire in Spanish. A reminder letter was sent two weeks after the original package was mailed. Two hundred eighty survivors completed and mailed the packet back (see Figure 1), for a response rate of 30%. Questionnaires from 265 survivors were considered evaluable (15 cases had missing data for psychosocial services use). Eligible participants were adult survivors (age 21 or older) with a breast cancer diagnosis (identified through their medical records), who had received cancer care in our comprehensive cancer center, who were in remission (identified through their medical records),

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram with cohort selection

Measures

The questionnaire contained demographic, medical, and psychosocial services sections. These included questions assessing age, education, religion, marital status, socioeconomic status, family composition, living situation, employment status, ethnicity, race, language preference, birthplace, years living in the United States, insurance status and time since diagnosis, and questions about survivors’ history of use of psychosocial services prior to and after the cancer diagnosis. The survey also assessed patients’ preferences for services, type of counseling, delivery format, type of mental health professional, and barriers to accessing the services. The type of mental health professional was defined utilizing the NCCN Distress Management Guidelines to include social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, and religious counselors (i.e. priests, pastoral counselors, or ministers). Additionally, we assessed the use of type of psychosocial services recommended by the NCCN Distress Management Guidelines including individual counseling, family therapy, couple therapy, support groups, group therapy, and pharmacotherapy. The survey was based on prior literature (Mosher et al. 2010, Weinberger, Nelson, and Roth 2011, Moadel, Morgan, and Dutcher 2007), and on the clinical experience of the authors with Latino populations in mental health and cancer disparities (Gany et al. 2011).

Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS 22 software package. First, the demographic characteristics of the 168 participants who completed and returned the survey were described using descriptive statistics. Then, the self-reported use of psychosocial services prior to and after the cancer diagnosis was described. The use of psychosocial services was assessed by type of service (i.e. individual therapy, pharmacology, etc.) and type of professionals (i.e. psychologist, psychiatrist, etc.). The frequency of use of service was assessed for the full sample and for the two ethnic groups, non-Latina Whites and Latinas. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample by ethnicity. T-test and χ2 analyses were used to evaluate differences between groups in the patterns of use and interest in psychosocial services. We used a two-sided significance level of a = 0.05. All analyses were restricted to available cases.

Bivariate logistic regression models were used to identify factors significantly associated with contact with mental health professionals and receipt of mental health services after a diagnosis of cancer. Type of mental health professional (social worker, religious counselor, psychiatrist, or psychologist), and type of mental health services (individual counseling, family therapy, couple therapy, group counseling, support group, or pharmacotherapy) after the cancer diagnosis were analyzed separately. Individuals were included in the analysis if they stated that they needed counseling or mental health services after their cancer diagnosis (n=116). These classifications were reduced to binomial outcomes for the purpose of analysis (i.e. contact with mental health professionals, yes or no). Potential explanatory variables included socio-demographics (age, marital status, employment status, and education level), ethnicity, preferred language, birthplace, and medical factors (private health insurance, time since diagnosis). Because of the limited sample size (n=116) we only conducted binary logistic regression models. Unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95 % confidence intervals were calculated to assess the relationship of demographic factors, type of insurance and time since diagnosis with the use of services and contact with professionals. A two-sided p significant level of less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participants

Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations of the demographics of the study participants. About two thirds of the sample was married or partnered (63%). Latinas had lower levels of education; 30% had a high school education or less, compared to 17% of the non-Latina Whites (χ2 = 8.29, p < .05). One third of the Latinas preferred only Spanish for their care; 30% of the Latina and 91% of the non-Latina Whites were born in the continental USA, although Latinas were also frequently born in Puerto Rico (22%) and South America (22%). One quarter of the sample (25%) had been diagnosed with breast cancer less than two years ago.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Breast Cancer Survivors by Ethnicity

| No. (%) or Mean (SD) of Participants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Total (N =265) | Latinas (n =97) | NL Whites (n =168) | χ2 | |

| Age1 | 61.16 (11.20) | 60.38 (11.40) | 61.64 (11.08) | −0.86 |

| Marital Status | 1.82 | |||

| Married or partnered | 166 (62.9) | 55 (57.3) | 111 (66.1) | |

| Single | 19 (7.2) | 8 (8.3) | 11 (6.5) | |

| Separated | 5 (1.9) | 3 (3.1) | 2 (1.2) | |

| Divorced | 42 (15.9) | 20 (20.8) | 22 (13.1) | |

| Widowed | 32 (12.1) | 10 (10.4) | 22 (13.1) | |

| Education | 8.29* | |||

| 12th grade/high school graduate | 58 (22.9) | 29 (30.0) | 29 (17.0) | |

| Some college or Associate’s degree | 60 (22.6) | 21 (2.1) | 39 (22.9) | |

| College Graduate | 55 (20.8) | 20 (21.1) | 35 (20.6) | |

| Post college/Graduate school | 92 (34.7) | 25 (26.3) | 67 (39.4) | |

| Employment | 4.40 | |||

| Employed- Full Time | 51 (33.3) | 23 (29.9) | 28 (36.8) | |

| Employed- Part Time | 28 (18.3) | 11 (14.3) | 17 (22.4) | |

| Retired | 58 (37.9) | 32 (41.6) | 26 (34.2) | |

| Unemployed | 8 (5.2) | 4 (5.2) | 4 (5.2) | |

| Unable to work | 8 (5.2) | 7 (9.1) | 1 (1.3) | |

| Birth Place | ||||

| US | 182 (69.0) | 29 (30.2) | 153 (91.1) | |

| Puerto Rico | 21 (8.0) | 21 (21.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Caribbean | 16 (6.0) | 16 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Central America | 7 (2.7) | 7 (7.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| South America | 21 (8.0) | 21 (21.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Europe | 17 (6.4) | 2 (2.1) | 15 (8.9) | |

| Preferred language | ||||

| English | 202 (76.2) | 34 (35.1) | 168 (100) | |

| Both equally | 32 (12.1) | 32 (33.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Spanish | 31 (11.7) | 31 (32.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Questionnaire language | ||||

| English | 234 (88.3) | 66 (68.1) | 168 (100) | |

| Spanish | 31 (11.7) | 31 (32.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Health Insurance | 1.89 | |||

| Private | 38 (31.7) | 13 (25.0) | 25 (36.8) | |

| Medicare or Medicaid | 82 (68.3) | 39 (75.0) | 43 (63.2) | |

| Time since diagnosis | 1.81 | |||

| 0–11 months | 12 (4.7) | 5 (5.8) | 7 (4.2) | |

| 1–2 years | 52 (20.6) | 14 (16.3) | 38 (22.8) | |

| 3–5 years | 152 (60.1) | 52 (60.5) | 100 (59.9) | |

| 6 years or more | 37 (14.6) | 15 (17.4) | 22 (13.2) | |

Note. Percentages may not equal 100% due to rounding

Frequencies might not be based on a total of 265 participants due to missing data

SD: Standard deviation

t-test was conducted,

p<.05

Use of Psychosocial Services by Ethnicity

Table 2 demonstrates the use of psychosocial services by ethnicity. Only one third of the sample (34%) reported having a discussion with their oncologist or cancer care provider about emotional problems or needs after the diagnosis (36% non-Latina Whites and 31% Latinas) (see Table 2). The most common reason why survivors did not have such discussions was because they did not need mental health services; non-Latina Whites (56%) were more likely to cite this reason than Latina survivors (36%,χ2 = 6.04, p < .001) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Use of Psychosocial Services by Ethnicity

| Total (n=265) | Latinas (n=97) | NL Whites (n=168) | χ2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Contact with professionals prior to the cancer diagnosis | 82 | (30.9) | 32 | (33.0) | 50 | (29.8) | 0.30 |

| Social Worker | 35 | (13.2) | 10 | (10.3) | 25 | (14.9) | 1.12 |

| Psychologist | 41 | (15.5) | 13 | (13.4) | 28 | (16.7) | 0.50 |

| Psychiatrist | 28 | (10.6) | 8 | (8.2) | 20 | (11.9) | 0.87 |

| Spiritual counselor | 21 | (7.9) | 13 | (13.4) | 8 | (4.8) | 6.29* |

| Discussion with oncologist or cancer care provider about emotional problems or needs after the diagnosis | |||||||

| Yes | 89 | (33.8) | 29 | (30.5) | 60 | (35.7) | 0.73 |

| No | 174 | (66.2) | 66 | (69.5) | 108 | (64.3) | |

| I had no need for services | 84 | (48.3) | 24 | (36.4) | 60 | (55.6) | 6.04* |

| Oncologist/Provider did not ask. | 38 | (21.8) | 12 | (18.2) | 26 | (24.1) | 0.83 |

| Oncologist/Provider is only interested in medical/physical issues. | 29 | (16.7) | 13 | (19.7) | 16 | (14.8) | 0.70 |

| I do not want to burden the oncologist/provider with my emotional problems. | 24 | (13.8) | 12 | (18.2) | 12 | (11.1) | 1.72 |

| Oncologist/Provider has no time to discuss my emotional concerns. | 20 | (11.5) | 6 | (9.1) | 14 | (13.0) | 0.60 |

| I do not feel comfortable discussing my emotional concerns with my medical provider. | 18 | (10.3) | 9 | (13.6) | 9 | (8.3) | 1.24 |

| Oncologist/Provider will send me to a mental health professional and I don’t want to be referred. | 7 | (4.0) | 5 | (7.6) | 2 | (1.9) | 3.48† |

| Need for mental health or psychosocial services after the cancer diagnosis | 116 | (43.3) | 47 | (49.0) | 69 | (40.1) | 1.96 |

| Contact with professionals after the cancer diagnosis | 76 | (65.5) | 27 | (57.4) | 49 | (71.0) | 2.28 |

| Social Worker | 31 | (26.7) | 8 | (17.0) | 23 | (33.3) | 3.80* |

| Psychologist | 36 | (31.0) | 11 | (23.4) | 25 | (36.2) | 2.15 |

| Psychiatrist | 30 | (25.9) | 13 | (27.7) | 17 | (24.6) | 0.13 |

| Religious counselor | 7 | (6.0) | 5 | (10.6) | 2 | (2.9) | 2.95† |

| Use of psychosocial services after the cancer diagnosis | 71 | (61.2) | 25 | (53.2) | 46 | (66.7) | 2.14 |

| Individual Counseling | 63 | (54.3) | 25 | (53.2) | 38 | (55.1) | 0.04 |

| Family Therapy | 4 | (3.4) | 3 | (6.4) | 1 | (1.4) | 2.04 |

| Couples Therapy | 8 | (6.9) | 2 | (4.3) | 6 | (8.7) | 0.86 |

| Group Therapy/Support group | 9 | (7.8) | 2 | (4.3) | 7 | (10.1) | 1.36 |

| Pharmacotherapy | 10 | (8.6) | 0 | (0) | 10 | (14.5) | 7.45 ** |

Note.

p<.10,

p<.05,

p<.01

Prior to the cancer diagnosis (see Table 2), 31% of the survivors had any contact with a psychosocial services provider, including social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, or a religious counselor. Latinas (13%) were more likely to have previous contact with a religious counselor than non-Latina Whites (5%, χ2 = 6.29, p < .01) (see Table 2). Prior to the diagnosis both groups had a similar frequency of contact with the other professionals.

As demonstrated in Table 2, recalling the time after their cancer diagnosis, 43% of the survivors (49% Latinas and 40% non-Latina Whites) expressed that they wanted or needed psychosocial services after the diagnosis. Of the survivors who reported needing services after the cancer diagnosis, two thirds (66%) reported having contact with psychosocial services providers and 61% reported using psychosocial services after the diagnosis. Non-Latina whites were more likely to have had contact with social workers (33%) than Latinas (17%, χ2 = 3.80, p < .05), and to use psychotropic medications (15%) than Latinas (0%, χ2 = 3.80, p < .01). There were no significant differences between the groups on contact with psychiatrists and psychologists or the use of counseling or psychotherapy.

Table 3 depicts in unadjusted logistic analyses, Latinas were less likely to have contact with mental health professionals (OR = 0.42, CI = 0.19–0.94). Further, survivors with lower education were less likely to have contact with mental health professionals (OR = 0.21, CI = 0.06–0.81) and to use psychosocial services (OR = 0.27, CI = 0.07–0.99).

Table 3.

Unadjusted Logistic Regression Models Predicting Likelihood of Not Receiving Psychosocial Services of No Contact with Psychosocial Care Professionals in Survivors with Psychosocial Needs After the Cancer Diagnosis (n=116)

| Contact with mental health professionals1 | Receipt of services2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| OR | CI | OR | CI | |

| Age | ||||

| Younger than 50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 50–65 years old | 0.38 | (.13–1.16) † | 0.46 | (0.17–1.27) |

| Older than 65 | 0.39 | (.11–1.37) | 0.71 | (0.21–2.35) |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Non-married | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Married | 0.56 | (0.23–1.36) | 0.45 | (0.18–1.07) † |

| Education | ||||

| High School or less | 0.21 | (0.06–0.81)* | 0.27 | (0.07–1.01)* |

| Some college | 0.59 | (0.20–1.71) | 0.89 | (0.31–2.57) |

| College graduate | 0.62 | (0.22–1.79) | 0.50 | (0.18–1.36) |

| Graduate school | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Employment | ||||

| Employed | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Retired | 0.71 | (0.23–2.18) | 0.63 | (0.21–1.90) |

| Unemployed or unable to work | 0.19 | (0.02–1.99) | 0.21 | (0.02–2.19) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 1.00 | |||

| Latina | 0.42 | (0.19–0.94)* | .57 | (.26–1.24) |

| Language Preference | ||||

| English | 1.00 | |||

| Spanish | 0.94 | (0.22–4.01) | 0.67 | (0.17–2.66) |

| Birthplace | ||||

| USA | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Puerto Rico | 1.38 | (0.27–7.14) | 1.65 | (0.32–8.53) |

| Latin America | 0.48 | (0.18–1.32) | 0.47 | (0.17–1.28) |

| Europe | 0.26 | (0.04–1.68) | 0.31 | (0.05–2.00) |

| Years living in US | ||||

| Born in USA | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| More than 20 | 0.39 | (0.15–1.04) † | 0.47 | (0.18–1.23) |

| 20 or less years | 0.98 | (0.18–5.44) | 1.18 | (0.21–6.50) |

| Type of insurance | ||||

| Private | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Public | 0.68 | (0.18–2.48) | 0.74 | (0.21–2.58) |

| Time since Diagnosis | ||||

| Less than 2 years | 1.78 | (0.64–4.94) | 0.52 | (0.23–1.18) |

| 2–6 years | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

Note.

p<.10,

p<.05

Professionals included social workers, psychiatrists, religious counselors, and/or psychologists

Type of mental health services included individual, family, couple, pharmacotherapy, or group counseling/support groups

Twenty-seven percent of the survivors (21% Latinas, 32% non-Latina Whites) are currently using psychosocial services. A quarter of the survivors (25% overall, non-Latina 24%, Latina 28%) are interested in obtaining psychosocial services. Although the difference is not statistically significant, non-Latina whites have more contact with psychologists (17%) and psychiatrists (15%) than Latina survivors (7%, 6%, respectively).

Discussion

This study evaluated ethnic differences in contact with providers of and use of psychosocial services by breast cancer survivors after their cancer diagnosis and during the survivorship phase. The same proportion of Latina and non-Latina white survivors reported needing psychosocial services after their cancer diagnosis, although non-Latina white survivors had contact with psychosocial services more frequently. Among the survivors who reported needing help for their psychosocial needs, Latina survivors were less likely to have contact with a social worker and to receive pharmacotherapy. In addition, survivors with less education were less likely to access psychosocial services, and to have contact with mental health professionals.

These disparities in use of services might be due to different patterns of general use of psychosocial services for ethnic minorities and individuals with lower education. For example, a large majority of Latina survivors expressed not wanting to take medication for their emotional difficulties. Acceptance of pharmacotherapy, could affect Latina patients’ outlook on seeking services from psychologists and psychiatrists. Mental health providers need to be aware and understanding of the resistance to pharmacotherapy from Latina survivors when forging the therapeutic alliance.

About a third of the total sample had a discussion with their oncologist or cancer care provider about their emotional problems or needs. Health care communication comprises a dual approach, patient and physician communication. A reciprocal relationship among both parts aims to improve exchange of information and address disinformation. Researches with Latinos and Latinas and African Americans report lack of knowledge or disinformation related to cancer treatment and psychosocial needs compared to non-Latina whites. Survivors reported not having these conversations because they had no need and because the provider was not interested or did not ask. It is critical that emotional well-being discussions be incorporated by oncologists or cancer care providers as part of medical check-ups to ensure that such conversations can occur. An assessment should be included in the routine ongoing cancer care plan.

Other differences in use of services by Latinas could be due to different help seeking behaviors. For instance, Latina survivors were more likely to seek help from their spiritual counselors and pastoral services, which distinguishes them from their non-Latina White counterparts. Our findings are consistent with previous studies that concluded Latinos endorse a greater interest in religious/spiritual counseling in the cancer context than their non-Latina White counterparts. (Yanez et al. 2016, Yanez, Stanton, and Maly 2012, Hunter-Hernandez, Costas-Muniz, and Gany 2015, Jurkowski, Kurlanska, and Ramos 2010). It has been demonstrated that religion can promote the use of health services in Latino religious communities (Leyva et al. 2014), and parishes have expressed their support to provide cancer care to their communities (Allen et al. 2014). To address this preference, religious leaders and pastoral counselors could create services and a network of care for Latina survivors. Such a network could be mutually beneficial as it could inform and improve psychologists and psychiatrists’ delivery of psychosocial services and referrals to Latinas, and religious leaders and pastoral services could expand their cancer care network and their health programming for their congregations.

Results illustrated the need to educate patients and cancer care providers about patients’ needs surrounding psychosocial issues and to create interventions that address cultural and linguistic issues. Patients need to receive information about how to access mental health services and cancer providers need to screen patients for distress and provide referrals when needed. Cancer care providers also need to be aware of and receive information about patients’ psychosocial needs and knowledge gaps, and about how to address patients’ concerns and questions. Mental health providers of cancer patients also need to be informed and receive training to provide culturally responsive services and to address concerns about medical interpretation in the context of mental health services delivery.

Providers should have an active role in screening for distress and identifying the psychosocial needs of patients. Some patients might not bring up their emotional issues and distress feelings spontaneously, for a variety of reasons. Therefore, in addition to communicating effectively, it is incumbent on providers to actively screen for psychosocial distress in ethnically diverse patients. The NCCN recommends the distress thermometer as screening tool (National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2003). The distress thermometer is a quick screening tool used to measure psychosocial distress. It includes a visual analogue scale that resembles a thermometer and an accompanying list of 34 problems grouped into five categories (practical, family, emotional, spiritual/religious and physical). This tool has been studied, validated, and used in multiple languages, including Spanish. Screening for psychosocial distress will likely help to identify patients in need of services but might also improve communication about distress with providers, and help to normalize and reduce mental health stigma.

This study has several limitations. First, the study was retrospective – the sample population was a cohort of breast cancer survivors replying to questions retrospectively about unmet needs and psychosocial service use in the period following news of their cancer diagnosis. Women were responding during remission, anywhere from one to five years post active treatment. Second, the study has a small sample of 265 participants (97 Latinas and 168 non-Latina whites). Even though, we sent a similar number of surveys the response rate of the non-Latina whites was higher than for Latinas. Given that Latinas showed lower educational levels than the non-Latina whites survivors, it is possible that the lower response rate amongst Latinas was due to lower literacy in this group. Further, another possible reason for the lower response supported by the research literature is disengagement. Disengagement from official institutions has been put forward as a reason to explain low response rates amongst ethnic minority groups (Groves and Couper 2012). Disengagement is often the result of lack of understanding of research and suspicion about the purpose or the merit of the research (Groves and Couper 2012). It is likely that patients with lower reading levels or patients who did not understand the purpose or importance of this study chose not to participate in this self-administered survey. Third, this is a single-site study – the sample was recruited from only one comprehensive cancer center limiting its generalizability. Fourth, all participants were already receiving cancer care in a comprehensive cancer center and had insurance; these results might not represent the experience of uninsured patients and patients who receive care in a more limited-resource environment. Fifth, the study relied on self-report, which potentially lead to subjective accounts of psychological needs. Additionally, due to the small sample of participants the results were not adequately powered to fully evaluate all possible covariates and cofounders; hence, it is possible that other factors such as education, language, literacy, and insurance could explain the differences found between both groups of women. Lastly, the study does not delve into other type of patient centered interventions outside of the NCCN Distress Management Guidelines recommendations, such as web-based interventions or other Complementary and Alternative Medicine interventions which could impact the distress and overall psychological health and well-being. Given the limitation noted above, this study makes important contributions to the literature indicative of the need for a larger scale study with a larger sample size, an enhanced study design, and a standardized methodology that uses evidence-based, standardized measures and tools to assess depression and distress.

Conclusion

The results gathered from this study can help inform the development of targeted psychosocial services and interventions to address the mental health preferences, needs, and service barriers of breast cancer survivors. Ethnically diverse patients often have different attitudes, needs, and preferences for psychosocial services. Previous literature shows that when appropriate treatment is well-delivered to minorities, results are comparable to those of white patients (Schraufnagel et al. 2006). Hence, it is crucial to study and address potential differences in psychosocial services availability, acceptability and help-seeking behaviors of ethnically diverse cancer patients and survivors to help lessen the disparities in contact with providers and use of psychosocial services. The study identifies critical factors from ethnicity, education, language and literacy that may constitute to health disparities and discrepancies in survivors’ overall satisfaction. The findings suggest the need for more culturally contextual research in the area of psychosocial services use in order to break disparities in the area of psychosocial services (Yanez et al. 2016).

Acknowledgments

Funding Support

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute # U54-13778804 CCNY/MSKCC Partnership, Memorial Sloan Kettering Center Grant: P30 CA008748 and training grant: T32CA009461 and the New York Community Trust. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the views of the awarding agencies.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Acosta FX. Barriers between mental health services and Mexican Americans: an examinations of a paradox. Am J Community Psychol. 1979;7(5):503–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00894047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen Jennifer D, Leyva Bryan, Torres María Idalí, Ospino Hosffman, Tom Laura, Rustan Sarah, Bartholomew Amanda. Religious Beliefs and Cancer Screening Behaviors among Catholic Latinos: Implications for Faith-based Interventions. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved. 2014;25(2):503–526. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for Hispanics/Latinos 2015–2017. American Cancer Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- August KJ, Nguyen H, Ngo-Metzger Q, Sorkin DH. Language concordance and patient-physician communication regarding mental health needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(12):2356–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen Deborah J, Alfano Catherine M, McGregor Bonnie A, Kuniyuki Alan, Bernstein Leslie, Meeske Kathy, Baumgartner Kathy B, Fetherolf Josala, Reeve Bryce B, Smith Ashley Wilder, Ganz Patricia A, McTiernan Anne, Barbash Rachel Ballard. Possible socioeconomic and ethnic disparities in quality of life in a cohort of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res & Treat. 2007;106(1):85–95. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9479-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson N, Le Cook B, Alegria M. Social determinants of mental health treatment among Haitian, African American, and White youth in community health centers. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(2 Suppl):32–48. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Cancer. Cancer Program Standards 2012 Version 1.2.1: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. American College of Surgeons; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ell K, Sanchez K, Vourlekis B, Lee PJ, Dwight-Johnson M, Lagomasino I, Muderspach L, Russell C. Depression, correlates of depression, and receipt of depression care among low-income women with breast or gynecologic cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(13):3052–3060. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ell K, Xie B, Kapetanovic S, Quinn DI, Lee PJ, Wells A, Chou CP. One-year follow-up of collaborative depression care for low-income, predominantly Hispanic patients with cancer. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(2):162–70. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eversley R, Estrin D, Dibble S, Wardlaw L, Pedrosa M, Favila-Penney W. Post-treatment symptoms among ethnic minority breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32(2):250–6. doi: 10.1188/05.onf.250-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, Kolody B, Vega WA. Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41(3):295–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gany Francesca, Ramirez Julia, Nierodzick Mary Lynn, McNish Thelma, Lobach Iryna, Leng Jennifer. Cancer portal project: A multidisciplinary approach to cancer care among Hispanic patients. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2011;7(1):31–8. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves RM, Couper MP. Nonresponse in Household Interview Surveys. Wiley; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter-Hernandez M, Costas-Muniz R, Gany F. Missed Opportunity: Spirituality as a Bridge to Resilience in Latinos with Cancer. Journal of Religion & Health. 2015;54(6):2367–2375. doi: 10.1007/s10943-015-0020-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkowski JM, Kurlanska C, Ramos BM. Latino Women’s Spiritual Beliefs Related to Health. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2010;25(1):19–25. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.080923-QUAL-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadan-Lottick NS, Vanderwerker LC, Block SD, Zhang B, Prigerson HG. Psychiatric disorders and mental health service use in patients with advanced cancer: a report from the coping with cancer study. Cancer. 2005;104(12):2872–81. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupski Tracey L, Sonn Geoffrey, Kwan Lorna, Maliski Sally, Fink Arlene, Litwin Mark S. Ethnic variation in health-related quality of life among low-income men with prostate cancer. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(3):461–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyva Bryan, Allen Jennifer D, Tom Laura S, Ospino Hosffman, Torres Maria Idali, Abraido-Lanza Ana F. Religion, Fatalism, and Cancer Control: A Qualitative Study among Hispanic Catholics. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2014;38(6):839–849. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.38.6.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, Greig D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;141(2–3):343–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckett T, Goldstein D, Butow PN, Gebski V, Aldridge LJ, McGrane J, Ng W, King MT. Psychological morbidity and quality of life of ethnic minority patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Oncology. 2011;12(13):1240–8. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massie MJ. Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;(32):57–71. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, Vahabzadeh A, Magruder K. Screening for distress and depression in cancer settings: 10 lessons from 40 years of primary-care research. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20(6):572–584. doi: 10.1002/pon.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moadel Alyson B, Morgan Carole, Dutcher Janice. Psychosocial needs assessment among an underserved, ethnically diverse cancer patient population. Cancer. 2007;109(2 Suppl):446–54. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher CE, DuHamel KN, Rini CM, Li Y, Isola L, Labay L, Rowley S, Papadopoulos E, Moskowitz C, Scigliano E, Grosskreutz C, Redd WH. Barriers to mental health service use among hematopoietic SCT survivors. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45(3):570–9. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Distress management. Clinical practice guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2003;1(3):344–74. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2003.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraufnagel TJ, Wagner AW, Miranda J, Roy-Byrne PP. Treating minority patients with depression and anxiety: what does the evidence tell us? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(1):27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2010 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. Atlanta: U.S.: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger MI, Nelson CJ, Roth AJ. Self-reported barriers to mental health treatment among men with prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2011;20(4):444–6. doi: 10.1002/pon.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanez B, McGinty HL, Buitrago D, Ramirez AG, Penedo FJ. Cancer Outcomes in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States: An Integrative Review and Conceptual Model of Determinants of Health. J Lat Psychol. 2016;4(2):114–129. doi: 10.1037/lat0000055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanez B, Stanton AL, Maly RC. Breast cancer treatment decision making among Latinas and non-Latina Whites: a communication model predicting decisional outcomes and quality of life. Health Psychol. 2012;31(5):552–61. doi: 10.1037/a0028629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanez B, Thompson EH, Stanton AL. Quality of life among Latina breast cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(2):191–207. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0171-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]