Abstract

Background

Identifying frailty is key to providing appropriate treatment for older people at high risk of adverse health outcomes. Screening tools proposed for primary care often involve additional workload. The electronic Frailty Index (eFI) has the potential to overcome this issue.

Aim

To assess the feasibility and acceptability of using the eFI in primary care.

Design and setting

Pilot study in one suburban primary care practice in southern England in 2016.

Method

Use of the eFI on the primary care TPP SystmOne database was explained to staff at the practice where a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) clinic was being trialled. The practice data manager ran an eFI report for all patients (n = 6670). Date of birth was used to identify patients aged ≥75 years (n = 589). The eFI was determined for patients attending the CGA clinic (n = 18).

Results

Practice staff ran the eFI reports in 5 minutes, which they reported was feasible and acceptable. The eFI range was 0.03 to 0.61 (mean 0.23) for all patients aged ≥75 years (mean 83 years, range 75 to 102 years). For CGA patients (mean 82 years, range 75 to 94 years) the eFI range was 0.19 to 0.53 (mean 0.33). Importantly, the eFI scores identified almost 12% of patients aged ≥75 years in this practice to have severe frailty.

Conclusion

It was feasible and acceptable to use the eFI in this pilot study. A higher mean eFI in the CGA patients demonstrated construct validity for frailty identification. Practice staff recognised the potential for the eFI to identify the top 2% of vulnerable patients for avoiding unplanned admissions.

Keywords: eFI, electronic Frailty Index, frail older adults, frailty, general practice, older people, primary health care

INTRODUCTION

Frailty is common among older people presenting to primary care clinicians, with a prevalence reported to be around 9–10% in community-dwelling older people.1,2 Importantly, frailty is associated with poor healthcare outcomes, including increased disability, admissions to hospital and care homes, and mortality.3 Frailty is the result of physiological decline during a lifetime, leading to increased vulnerability to stressors.4 However, it is neither a certainty of ageing nor a condition of inevitable deterioration, and may be improved through appropriate interventions.5 The number of people in the UK aged >85 years is anticipated to double between 2010 and 2030, and there is increasing UK and worldwide recognition that primary care clinicians need to know how to identify frailty and other geriatric syndromes.6

A number of frailty assessment tools have been developed,7 but their application in primary care clinical practice has been limited. This may be because many require resources for physical assessment of the patient. For example, the Fried Frailty Phenotype identifies physical frailty in people with three out of five of the following: unintentional weight loss, exhaustion, reduced physical activity, low grip strength, and slow gait speed.8 The first three items are generally self-reported, but grip strength and gait speed are usually measured. Low grip strength and gait speed are included in a number of other approaches to identifying frailty, such as the Gérontopôle Screening Tool,9 and the five-component FRAIL scale,10 where the assessment of gait speed is central. Both low grip strength11 and slow gait speed12 have also been proposed as useful single markers of physical frailty.

Other approaches include the use of self-reported questionnaires, such as the simple PRISMA-7 questions, which has been reported to be suitable for primary health care,13 and the 15-item Groningen Frailty Indicator.14 A Dutch study developed a short form of the Easy-Care assessment questionnaire for use in primary care.15,16 However, the authors reported that the substantial time investment required was a major limitation. Clinical knowledge of the health professional is used to categorise patients’ health and frailty against nine descriptions and visual images in the Canadian Study of Health and Ageing (CSHA) Clinical Frailty Scale.17

How this fits in

The electronic Frailty Index (eFI) has been developed by Clegg and colleagues to identify frailty using routine data held on primary care databases. This pilot study demonstrated that the eFi was simple and quick to use, acceptable to practice staff, and appeared to discriminate older patients referred for comprehensive geriatric assessment from the total practice population. This paper adds to existing evidence that the eFI may be useful in primary care to identify patients living with frailty, and potentially also those suitable for avoiding the unplanned admissions register.

A frailty tool suitable for primary care would ideally predict adverse outcomes, be short and easy to administer, allow stratification, and aid prioritisation of people for full assessment and management through referral for comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA).18 However, implementation of any new process in primary care is recognised as being challenging,19 with a requirement for minimal time demands on stretched primary healthcare services.20 The cumulative deficits approach to determining a Frailty Index (FI) developed by Rockwood and colleagues uses data from existing clinical records and therefore holds promise for use in primary care.21,22 It assesses generalised frailty through determining the proportion of deficits experienced by an individual. These deficits include the presence of long-term conditions, physical, cognitive, or sensory impairments, and psychosocial factors, such as social vulnerability.

A recent breakthrough has been the development by Clegg and colleagues of an electronic Frailty Index (eFI) that is derived automatically from data held in primary healthcare electronic records.23 It was developed using the TPP ResearchOne primary healthcare database, and then validated for use on the TPP SystmOne and The Health Improvement Network (THIN) primary care electronic health record databases. The work used anonymised data from 931 541 patients aged 65 to 95 years, using 36 deficits to calculate an eFI score based on the deficits present as a proportion of the total number possible. Population quartiles were used to derive four categories: fit older people, and those with mild, moderate, and severe frailty. Importantly, these categories had predictive validity for mortality and admission to hospital and care home at 1, 3, and 5 years. It was concluded that implementation of the eFI into routine primary care could facilitate the delivery of evidence-based interventions and improve health service planning.

As part of an evaluation of a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) clinic in primary care, the authors of this study found that searching for Read codes in the practice electronic health records to identify frail patients was time consuming. The practice data manager reported that search time for audits of clinical practice using these codes similarly impeded the maintenance of the practice avoiding unplanned admissions (AUA) register, an NHS priority for GPs to identify and proactively case manage their top 2% of vulnerable patients.

The participating primary care practice used the TPP SystmOne EHR system for routine clinical practice, and employed a practice data manager to administer the database. The authors aimed to assess the feasibility and acceptability of running an eFI report in a pilot study in one primary care practice in England.

METHOD

Patients and setting

All patients aged ≥75 years registered at one suburban primary care practice in southern England were included (n = 589). A CGA clinic run by a consultant geriatrician was established in the practice between February and June 2016. The GPs and specialist elderly care nurse were encouraged to refer any patients they thought suitable for an in-depth CGA, which took 60 to 90 minutes to conduct. Taxis were provided to maximise participation of older people who had difficulty accessing the practice, but patients unable to attend the clinic were excluded.

Data collection

Data collection took place between February and June 2016. The practice data manager was provided with instructions by one of the authors on the six commands required to run an eFI report for the entire practice list (n = 6670). Date of birth was then used to identify patients aged ≥75 years (n = 589). Data collected were age, sex, eFI, and whether the patient had been referred to the CGA clinic (n = 18). Individual identifiers (name, address, NHS number) were removed prior to data entry. The acceptability of running the eFI report was assessed during interviews with the practice data manager, practice manager, a GP, and practice nurse.

Data analysis

Data were entered into a database and analysed using descriptive statistics (summation, minimum, maximum, mean, standard deviation, median, and prevalence). Data for all patients aged ≥75 years, including those referred to the new CGA clinic, were categorised by eFI scores using Clegg’s criteria as follows:

score 0 to 0.12 represents patients without frailty;

>0.12 to 0.24 represents patients with mild frailty;

>0.24 to 0.36 represents patients with moderate frailty; and

>0.36 represents patients with severe frailty.

The prevalence of each eFI category was generated using IBM SPSS version 22 for all patients aged ≥75 years and for those referred to the CGA clinic. Construct validity was assessed by comparing the difference between the mean eFI scores for all patients aged ≥75 years and those referred to the CGA clinic.

RESULTS

The age, sex, and eFI score for all 589 patients aged ≥75 years, including those referred to the CGA clinic, were collected from the primary care EHR databases by the practice data manager (Table 1). This process was completed in 5 minutes. The mean eFI scores were the same for both males and females within each group. However, the score of 0.23 for the total practice population of older people corresponded with the mild frailty category, whereas those referred to the CGA clinic had a mean score of 0.33, well within the moderate frailty category.

Table 1.

Age, sex, and eFI scores for all patients aged ≥75 years and those referred for CGA at one primary healthcare practice

| Patients aged ≥75 years (n= 589) | CGA referrals aged ≥75 years (n= 18) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | |

| Mean age (range), years | 82.3 (75 to 102) | 83.0 (75 to 101) | 82.7 (75 to 102) | 83.9 (75 to 94) | 79.6 (75 to 89) | 81.3 (75 to 94) |

|

| ||||||

| Mean eFI (SD) Range | 0.23 (0.11) | 0.23 (0.12) | 0.23 (0.12) | 0.33 (0.10) | 0.33 (0.10) | 0.33 (0.09) |

| 0.03 to 0.56 | 0.03 to 0.61 | 0.03 to 0.61 | 0.25 to 0.53 | 0.19 to 0.52 | 0.19 to 0.53 | |

|

| ||||||

| eFI median | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.31 |

CGA = comprehensive geriatric assessment. eFI = electronic Frailty Index. SD = standard deviation.

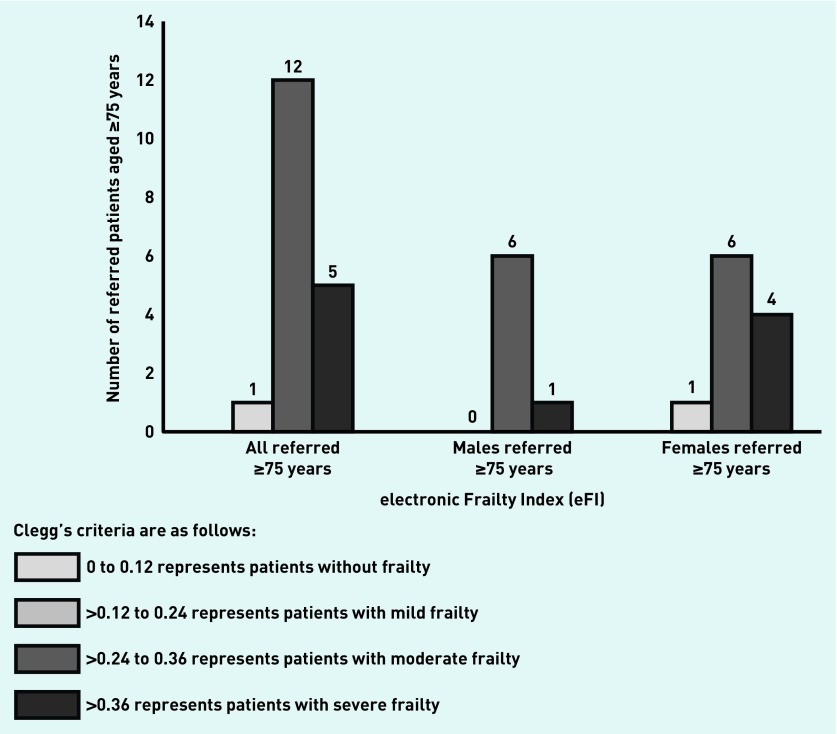

The prevalence of each eFI category was summated for all 589 patients aged ≥75 years registered at the participating practice (247 males, 342 females) (Figure 1), and then for all patients aged ≥75 years referred for a CGA at the GP practice (seven males, 11 females) (Figure 2). The frequencies of individual eFI scores for all 589 patients aged 75 years and over are shown in Figure 3. In all, 212 (36.0%) patients aged ≥75 years were categorised as having mild frailty, 189 (32.0%) as moderate frailty, and 69 (11.7%) as severe frailty. Patients referred for a CGA included 6.3% of those categorised as moderately frail and 7.2% of those with severe frailty.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of electronic Frailty Index (eFI) categories for all patients aged ≥75 years.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of electronic Frailty Index (eFI) categories for 18 patients aged ≥75 years referred to the comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) clinic.

Figure 3.

Frequencies of electronic Frailty Index (eFI) for all patients aged ≥75 years.

The data manager and practice manager reported that the few minutes taken to run the eFI report was acceptable, and noted that it had the potential to identify the 2% of patients for the AUA register. The GP and nurse comments in reply to the interviewers’ questions are shown below:

‘I played with it the other day. It was great, and you could pull up your top three patients and all sorts of things.’

(GP)

‘There were patients we all know, and often they’re on our complex care register, and there’s a few younger ones that, I suppose, it’s pulled up … which we need to look at.’

(Nurse)

DISCUSSION

Summary

The eFI report was simple to run and acceptable to practice staff. The eFI was developed as a method of identifying frailty in primary care, and in this small pilot study it was feasible to stratify older patients by frailty score in a few minutes (researcher input helped instruct the database manager but did not reduce the time required to produce the eFI report for the whole database). The higher mean eFI score of those patients referred for CGA compared with the total practice population of older patients adds construct validity to the use of the eFI. Importantly, the eFI scores identified almost 12% of patients aged ≥75 years in this practice to have severe frailty. The majority of patients referred to the CGA clinic had moderate frailty scores, but in proportion to the total practice population the referrals for moderate and severe frailty were similar at around 7%. This may reflect the study requirement to attend the clinic at the practice, which excluded those who were housebound, or GP decision making around selection of patients, but further investigation is required.

The same eFI report simultaneously provided information for the essential practice task of avoiding unplanned admissions, which resulted in an immediate time saving for the primary care practice.

Strengths and limitations

This was a small pilot study in a single primary care practice in southern England. The practice has a clinical rather than a research focus, and this was a pragmatic evaluation of the eFI in a time-pressured primary care practice in the NHS. Nevertheless, the practicality of running an eFI report in primary care to stratify an older population by frailty score was demonstrated. However, the eFI is not currently available on all EHR databases and is a screening tool, so the need for clinical judgement remains.

Comparison with existing literature

The finding that 11.7% of the total practice population had high frailty scores is in keeping with current literature that estimates the prevalence of frailty at around 10%.2 The British Geriatrics Society has called for all health and social care staff to assess older people for frailty at each encounter,5 and there is recognition that time-pressured primary care staff need a simple and quick tool to achieve this.20 The management of frailty requires a screening tool to identify patients for in-depth assessment through a CGA process.7

Implications for research and practice

This pilot study adds to existing evidence that the eFI is quick and simple to use, and could be important in primary care to stratify practice populations by frailty, and also identify the most vulnerable patients for the AUA register. Additionally, researchers in primary health care may find eFI a practical and effective method to screen populations to identify potential study participants living with frailty. The experience of using the eFI in this study would support the need for further evaluation in clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff and patients of the participating primary care practice for their time and cooperation.

Funding

This pilot study was one component of research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) Wessex. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health. This study was supported by the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Southampton. Helen Clare Roberts and Avan Sayer received support from the NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre.

Ethical approval

This pilot was one component of a study approved by the NHS South Central Research Ethics Committee (15/SC/0711).

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Mijnarends DM, Schols JM, Meijers JM, et al. Instruments to assess sarcopenia and physical frailty in older people living in a community (care) setting: similarities and discrepancies. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(4):301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clegg A, Rogers L, Young J. Diagnostic test accuracy of simple instruments for identifying frailty in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2015;44(1):148–152. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rockwood K, Mitnitski A, Song X, et al. Long-term risks of death and institutionalization of elderly people in relation to deficit accumulation at age 70. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(6):975–979. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, et al. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner G, Clegg A. Best practice guidelines for the management of frailty: a British Geriatrics Society, Age UK and Royal College of General Practitioners report. Age Ageing. 2014;43(6):744–747. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cesari M, Prince M, Thiyagarajan JA, et al. Frailty: an emerging public health priority. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(3):188–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dent E, Kowal P, Hoogendijk EO. Frailty measurement in research and clinical practice: a review. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;31:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tavassoli N, Guyonnet S, Abellan Van Kan G, et al. Description of 1108 older patients referred by their physician to the ‘geriatric frailty clinic (GFC) for assessment of frailty and prevention of disability’ at the Gérontopôle. J Nutr Health Aging. 2014;18(5):457–464. doi: 10.1007/s12603-014-0462-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morley JE, Malmstrom TK, Miller DK. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(7):601–608. doi: 10.1007/s12603-012-0084-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Syddall H, Cooper C, Martin F, et al. Is grip strength a useful single marker of frailty? Age Ageing. 2003;32(6):650–666. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afg111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castell MV, Sanchez M, Julian R, et al. Frailty prevalence and slow walking speed in persons age 65 and older: implications for primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutorius FL, Hoogendijk EO, Prins BA, van Hout HP. Comparison of 10 single and stepped methods to identify frail older persons in primary care: diagnostic and prognostic accuracy. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:102. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0487-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuurmans H, Steverink N, Lindenberg S, et al. Old or frail: what tells us more? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(9):M962–M965. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.9.m962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Kempen JA, Schers HJ, Jacobs A, et al. Development of an instrument for the identification of frail older people as a target population for integrated care. Br J Gen Pract. 2013 doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X664289. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp13X664289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craig C, Chadborn N, Sands G, et al. Systematic review of EASY-care needs assessment for community-dwelling older people. Age Ageing. 2015;44(4):559–565. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173(5):489–495. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romero-Ortuno R. Frailty in primary care. In: Theou O, Rockwood K, editors. Frailty in aging Biological, clinical and social implications. Basel: Karger; 2015. pp. 85–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lau R, Stevenson F, Ong BN, et al. Addressing the evidence to practice gap for complex interventions in primary care: a systematic review of reviews protocol. BMJ Open. 2014;4(6):e005548. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson M, Walter F. Increases in general practice workload in England. Lancet. 2016;387(10035):2270–2272. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00743-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(7):722–727. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Searle SD, Mitnitski A, Gahbauer EA, et al. A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr. 2008;8:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clegg A, Bates C, Young J, et al. Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age Ageing. 2016;45(3):353–360. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]