Abstract

Background

Provider financial incentives are being increasingly adopted to help improve standards of care while promoting efficiency.

Aim

To review the UK evidence on whether provider financial incentives are an effective way of improving the quality of health care.

Design and setting

Systematic review of UK evidence, undertaken in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations.

Method

MEDLINE and Embase databases were searched in August 2016. Original articles that assessed the relationship between UK provider financial incentives and a quantitative measure of quality of health care were included. Studies showing improvement for all measures of quality of care were defined as ‘positive’, those that were ‘intermediate’ showed improvement in some measures, and those classified as ‘negative’ showed a worsening of measures. Studies showing no effect were documented as such. Quality was assessed using the Downs and Black quality checklist.

Results

Of the 232 published articles identified by the systematic search, 28 were included. Of these, nine reported positive effects of incentives on quality of care, 16 reported intermediate effects, two reported no effect, and one reported a negative effect. Quality assessment scores for included articles ranged from 15 to 19, out of a maximum of 22 points.

Conclusion

The effects of UK provider financial incentives on healthcare quality are unclear. Owing to this uncertainty and their significant costs, use of them may be counterproductive to their goal of improving healthcare quality and efficiency. UK policymakers should be cautious when implementing these incentives — if used, they should be subject to careful long-term monitoring and evaluation. Further research is needed to assess whether provider financial incentives represent a cost-effective intervention to improve the quality of care delivered in the UK.

Keywords: efficiency, general practice, health policy, hospitals, motivation, quality of health care

INTRODUCTION

In the UK, events including inquiries into care failings at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust and paediatric cardiac surgery at Bristol Royal Infirmary have made safety and quality of care a major priority for health professionals, politicians, and the general public.1,2 Policies aiming to improve healthcare quality frequently focus on provider financial incentives,2–6 which are being increasingly used across the NHS to promote efficiency while maintaining or improving standards of care.2,5,7–9

Provider financial incentives traditionally consist of four main approaches:

capitation;

fee for service;

salary; and

block budgets.

Since the last decade, pay-for-performance and reputational payments (public reporting or PR) are also being implemented.4 The UK Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF), introduced in April 2004, represents the world’s largest primary care pay-for-performance programme, aiming to reward general practices for delivering good-quality care.9

There is uncertainty about the effectiveness of provider financial incentives in improving the quality and safety of care.10,11 This article reviews and critically appraises the evidence on whether provider financial incentives are an effective way of improving the quality of care delivered by health systems. As the international evidence has been systematically reviewed in previous work,4,5,7,12 this review focuses on the UK literature, aiming to specifically inform UK decision makers.

METHOD

A systematic review of the UK literature assessing the use of provider financial incentives to improve the quality of health care was performed; Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations were adhered to.13 A senior expert librarian designed and conducted a comprehensive search of the MEDLINE and Embase databases from inception until August 2016 using the Ovid portal. The search terms used were: provider; providers; physicians; hospital; financial incentives; payment; reimbursement; fees; payment system; patient safety; quality of care; quality of healthcare; quality of health care; Britain or United Kingdom or UK or England or Northern Ireland or Wales or Scotland.

Two authors, working independently, screened all titles and abstracts for eligibility; records considered potentially relevant were retrieved in full text and assessed. Reference lists of review articles were also screened to identify additional relevant articles. Any disagreements were discussed with the senior researcher and resolved by consensus. Information was extracted independently by two authors and disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus.

How this fits in

Provider financial incentives are increasingly being used in the NHS to promote efficiency while improving the quality of health care. This systematic review concludes that the effects of UK provider financial incentives on care quality are unclear — using such incentives may, in fact, be counterproductive to their desired aim of improving the quality and efficiency of health care.

English-language, original articles that assessed the relationship between UK provider financial incentives and a quantitative measure of the quality of health care were included. All included articles assessed financial incentives as the independent variable, and quality of health care as the dependent variable. Articles were excluded if there was no comparison group or baseline analysis before the intervention. After identifying the articles to be included in the review, all publications by each included author were screened on 1 September 2016 to identify any other relevant articles for inclusion.

Petersen et al ’s5 method of ranking effect was used:

positive: showed improvement for all measures of quality of care;

intermediate: showed improvement in some measures of quality, but not all;

negative: showed a worsening of measures of quality.

Articles showing no effects were documented as such.5 The quality of included papers was assessed using the quality assessment checklist published by Downs and Black;14 certain questions (namely 15 and 23–27) of the checklist were omitted due to the nature of included evidence. Owing to the heterogeneity of including studies, meta-analysis was not conducted and results are presented descriptively.

RESULTS

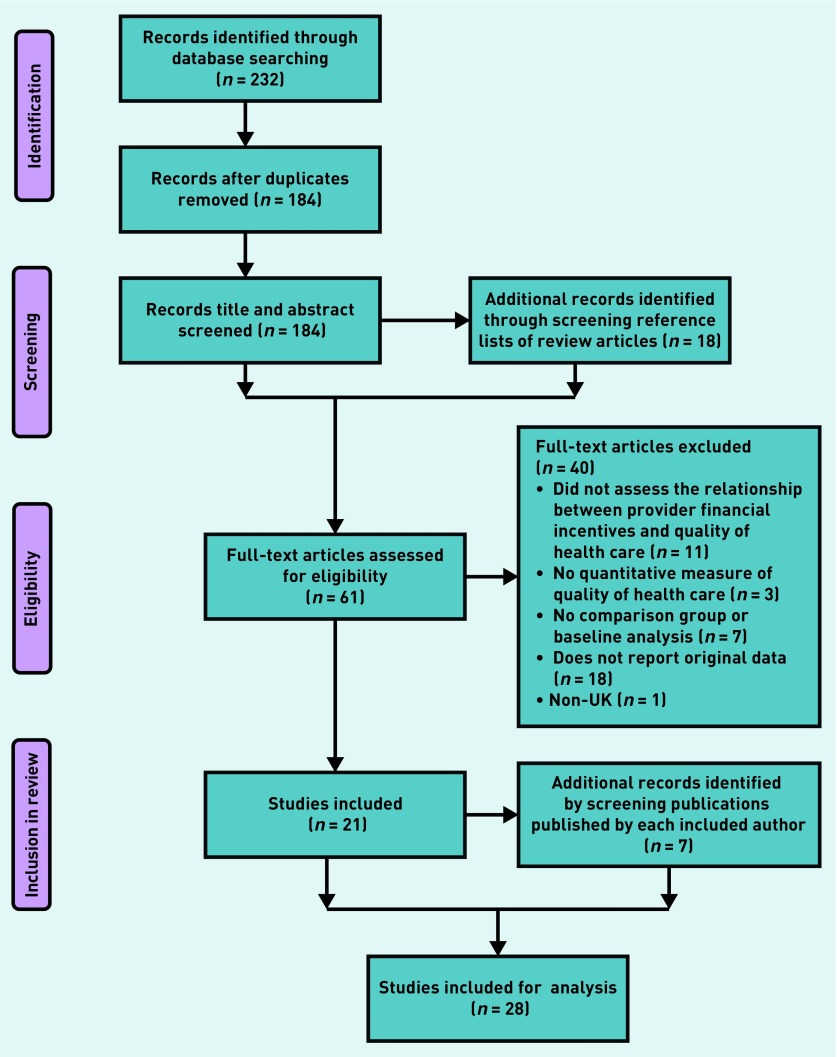

The systematic search revealed 232 publications. Removing duplicates left 184 publications, of which the title and abstract were screened. Sixty-one articles were full-text assessed; 21 fulfilled the criteria for inclusion. The PRISMA flowchart can be seen in Figure 1. After screening all other publications by each included author, seven additional papers were included, resulting in 28 articles for analysis. Study designs included difference-in-differences regression analyses, regression discontinuity design, synthetic control method, retrospective analyses, probit modelling, longitudinal studies, cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, and interrupted time series analyses.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of study selection process.

Appendix 1 summarises the 28 included studies along with their quality scores. One study, assessing the effects of Payment by Results on acute care hospitals, showed an intermediate effect on quality of care.15 Five articles examined the impact of pay for performance in hospitals — two studies showed a positive effect,16,17 two an intermediate effect,18,19 and one a negative effect.20 Twenty-one articles assessed the impact of the pay-for-performance QOF scheme in the primary care setting, with seven studies showing a positive effect,13,21–26 13 showing an intermediate effect,11,27–38 and one showing no effect.39 One article reporting on the effects of the QOF on the UK population level showed no effect.40

In total, nine articles reported positive effects of financial incentives, 16 reported intermediate effects, two reported no effect, and one reported a negative effect.

Studies reporting positive effects

Allen et al 17 found that the introduction of a best-practice tariff in English hospitals was associated with reductions in postoperative length of stay and a lower proportion of laparoscopic cholecystectomies being converted to open procedures. The impact of the Advancing Quality pay-for-performance programme on hospital mortality was assessed by Sutton et al,16 who found significant reductions in mortality during the 18-month study period. An earlier study by Sutton et al 21 assessed the quality of care following implementation of the QOF scheme; it showed that annual recording rates of blood pressure, smoking status, cholesterol, body mass index, and alcohol consumption had increased by 19.9%. Five studies22–25,41 investigating clinical outcomes of patients with diabetes after implementation of the QOF found significant improvements in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels, total cholesterol, and blood pressure levels. Fichera et al 26 identified that the introduction of the QOF was followed by improved lifestyle behaviours for individuals with targeted health conditions.

Studies reporting intermediate effects

Farrar et al15 found that the introduction of Payment by Results in acute care hospitals was associated with a significant reduction in in-hospital mortality, but there was no significant change in 30-day post-surgical mortality or emergency re-admission after being treated for hip fracture. Studies by Kristensen et al18 and McDonald et al19 reported that, although the Advancing Quality pay-for-performance programme in English hospitals led to initial reductions in hospital mortality, these reductions were greater in non-participating hospitals16 and, by the end of the follow-up period, were not maintained.18,19

Vamos et al 33 and Alshamsan et al 34 examined the impact of the QOF on the achievement of national targets for blood pressure, HbA1c levels, and cholesterol. Vamos et al 33 showed that, after the QOF had been implemented, there were significant improvements for cholesterol and blood pressure, but not for HbA1c level. Alshamsan34 found that:

HbA1c levels significantly worsened compared with the baseline;

cholesterol levels initially reduced in white and black patients, but not in South Asian patients; and

3 years later, cholesterol levels significantly increased in white patients.

The QOF was associated with initial improvements in blood pressure but these were not sustained in the post-QOF implementation period. Similar findings were obtained by Lee et al.36 A local version of the QOF, assessed by Pape et al,35 led to higher target achievements for hypertension, heart disease, and stroke; however, this was driven by higher rates of exception reporting and there were no improvements in mean blood pressure, cholesterol, or HbA1c levels.

The impact of the QOF scheme on diabetes management was assessed by Millett et al,27 who found that, although there were improvements for patients with diabetes who had comorbidities, there was a negative impact on those with diabetes and no comorbidities. Longitudinal studies by Campbell et al 11,28 showed initial improvements in quality of care for patients with asthma and diabetes, but not for those with coronary heart disease; the rate of improvement slowed for all conditions. Continuity of care was found to reduce immediately after the implementation of the QOF.11

Calvert et al,29 investigating the impact of the QOF on diabetes management, showed that existing improvement rates in glycaemic control, cholesterol levels, and blood pressure reduced after implementation of the QOF. There was no improvement in the number of patients with type 2 diabetes and HbA1c levels of >10%; in addition, the QOF may have increased the number of patients with type 2 diabetes and HbA1c levels of ≤7.5%.

Millett et al 30 found that the introduction of the QOF was followed by reductions in mean blood pressure for white, black, and South Asian groups. However, HbA1c levels were only significantly reduced for white groups, potentially increasing ethnic inequity. A similar study by Hamilton et al 38 found reduced disparities in diabetes outcomes between males and females post-QOF, but there was a widening of age group disparities.

Two studies31,32 examined the achievement rates of quality indicators after the QOF scheme was introduced. Although there were significant increases in the rate of improvement of incentivised quality indicators, for non-incentivised indicators there was no significant effect in the first year and, by 2007, achievement rates were significantly lower than expected.31,32 The impact of a local QOF initiative on smoking cessation was assessed by Hamilton et al,37 who found increased recording of smoking status and smoking cessation advice. However, age, social, and ethnic inequalities were associated with these findings.

Studies reporting no effect

Serumaga et al 39 assessed the effect of the QOF on patients with hypertension and found:

no significant change in blood-pressure monitoring, control, or treatment intensity; and

no effects on hypertension-related adverse outcome or all-cause mortality.

Similarly Ryan et al40 found no significant associations between the introduction of the QOF and changes in population mortality.

Studies reporting negative effects

Kreif et al 20 re-analysed data from the study by Sutton et al16 and found that the Advancing Quality pay-for-performance programme was associated with statistically significant increases in mortality for non-incentivised conditions, with no significant reductions in incentivised conditions.

Quality of included studies

Quality scores for the included studies ranged from 15 to 19, out of a maximum of 22 points. Points often missed on the quality checklist were for failing to:

describe characteristics of included patients;

describe distributions of potential confounders;

report adverse events;

describe characteristics of patients lost to follow-up; and

take into account patient loss to follow-up.

Other missed criteria included:

providing estimates of random variability;

reporting actual probability values for the main outcomes;

adjusting for different lengths of patient follow-up; and

recruitment of patients from the same population.

DISCUSSION

Summary

Twenty-eight eligible UK studies assessed the use of provider financial incentives to improve the quality of health care. Six studies reported on the effects in hospitals,15–20 21 focused on the general practice setting,11,13,21–39 and one article reported at the UK population level.40 Nine articles reported positive effects of incentives on quality of care,16,17,21–26,41 16 reported intermediate effects,11,15,18,19,27–38 two reported no effect,39,40 and one reported a negative effect.20 Quality assessment scores for the included articles ranged from 15 to 19, out of a maximum of 22 points.

There is evidence of adverse effects including worsening of quality outcomes,27,34 reduced continuity of care,11 increased inequity among ethnic groups and age groups,30,34,36–38 increased exception reporting,35 and non-incentivised conditions having higher mortality levels and receiving poorer quality of care.20,31

The different study designs employed by the articles in the review do not appear to lean towards a higher-quality score or effect size. Similarly, articles with the highest-quality scores do not appear to lean towards a positive, intermediate, or negative ranking effect.

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review may be affected by publication bias, as healthcare decision makers may not wish to publish studies showing negative effects of financial incentives. The authors acknowledge that, by only including UK evidence, potentially informative international studies were excluded. However, this study is particularly relevant to UK policymakers, being the only systematic review evaluating the effectiveness of UK provider financial incentives on improving the quality of care.

All included studies had a baseline or comparison group, and quality assessment of included articles was conducted using a validated and transparent quality checklist. Quality assessment scores suggest that, within the constraints of this research area, most of the included articles were of high quality. Owing to the nature of research into financial incentives, it is very difficult to perform randomised controlled trials, adjust for confounding, report on all adverse events, and account for patients lost to follow-up.

The generalisability of findings is limited, with the majority of studies focusing on the QOF incentive as opposed to other types of provider financial incentives. The impact of the QOF is particularly difficult to assess as the incentive was implemented nationwide, leaving no clear control group. Moreover, the quality of care was already improving before the QOF was implemented and it is unclear whether improvements exceeded previous trends after the incentive — especially considering that quality outcomes have been measured for fewer than 3 years post-implementation.11,28,29,41 The amount of UK evidence available that assesses the effects of Payment by Results is limited — only one study was identified.15

Comparison with existing literature

International research also suggests that the effects of provider financial incentives on healthcare quality are unclear and that the evidence base is unable to support widespread implementation into health policy.9,42–45 There have been no randomised control trials evaluating provider financial incentives, and the majority of studies have no control groups and lack generalisability.10,42 Studies with control groups have mixed results, and relatively few significant improvements are reported.7,10,42,46

A number of adverse effects to provider financial incentives have been reported internationally. These include reduced clinician job satisfaction,47 declining continuity of care,11 diverting focus from quality of care to quality of record keeping,42 increased gaming,48 and exception reporting.42 Mendelson et al,45 in their recent systematic review, concluded that there was no clear evidence to suggest that pay-for-performance programmes improve patient outcomes in any healthcare setting. Markovitz and Ryan44 systematically assessed whether these apparently disappointing results of provider incentives are masked by heterogeneity of patient and catchment factors, organisational and institutional capabilities, and programme characteristics — they found that accounting for this heterogeneity does not sufficiently alter the conclusion that provider financial incentives have largely failed to improve healthcare quality.

Implications for research

These findings suggest that the effects of UK provider financial incentives on healthcare quality are unclear. Included studies lack consensus: the majority show an improvement in some quality measures, but not all, and demonstrate that, although incentives may initially improve quality, these improvements can plateau or even decline.11,18,19,32–34,41 This uncertainty is also apparent when considering the effects of different types of financial incentive on quality of care.

Despite uncertainly about their effectiveness, provider financial incentives receive widespread political attention and are increasingly being implemented.42 UK policymakers should be cautious — if implemented, these incentives should be subject to careful long-term monitoring and evaluation so that the origins of shortcomings can be understood and acted on.

Another factor to bear in mind is that provider financial incentives are expensive; the total annual expenditure for the QOF alone is approximately £1 billion.10 Given the unclear effects on healthcare quality, these significant costs do not appear to be justified and, added to that, the use of provider financial incentives may be counterproductive to the intended aim of improving healthcare efficiency.10 Further research is needed to assess whether UK provider financial incentives do, or do not, represent a cost-effective intervention to improve the quality of care delivered.

Appendix 1. Included studies and quality assessment scoresa

| Study, year | Aim | Setting | Study design | Comparison group | Incentives | Quality measure | Analysis and results | Overall effect | Quality score (out of 22 points) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farrar et al (2009)15 | To examine whether the introduction of PbR was associated with changes in volume, cost, and quality of care between 2003/2004 and 2005/2006 | Acute care hospitals in England | Difference-in-differences analysis; retrospective analysis of patient-level secondary data with fixed-effects models | Trusts in England and providers in Scotland not implementing PbR in the relevant years | PbR (a fixed-tariff case mix-based payment system) | Changes in in-hospital mortality, 30-day post-surgical mortality, and emergency re-admission after treatment for hip fracture | The only result with statistical significance was the difference in the change in in-hospital mortality for foundation trusts compared with Scotland. This was the only evidence of improved quality of care. There was no evidence that quality of care reduced due to the incentive | Intermediate | 15 |

| Kristensen et al (2014)18 | To assess the long-term effects of the Advancing Quality pay-for-performance programme on quality of care | 24 hospitals in the north-west region in England providing emergency care | Difference-in-differences regression analysis to compare risk-adjusted mortality for an 18-month period before the programme and 18 (short-term) and 24 (long-term) months after the programme | Performance 18-months before the programme, and hospitals not participating | Advancing Quality pay-for-performance programme | Measures of quality of care related to five clinical categories: acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, pneumonia, conditions requiring coronary artery bypass grafting, hip or knee surgery. Hospital 30-day in hospital risk-adjusted mortality | In the short- and long-term periods, average performance reported by participating hospitals improved and hospital mortality fell. Performance improvement slowed over time and, for some measures, plateaued. Reduction in hospital mortality was greater in hospitals not participating in the programme. By the end of the 42-month follow-up period, reduced mortality in the participating hospitals was no longer significant. In the longer term, mortality for conditions not covered by the programme fell more in participating hospitals than in the control hospitals, raising the possibility of a positive spill-over effect on care for conditions not covered by the programme. Short-term relative reductions in mortality for conditions linked to financial incentives in hospitals participating in a pay-for-performance programme were not maintained | Intermediate | 19 |

| Tahrani et al (2008)25 | To assess the impact of practice size on diabetes care in Shropshire pre- and post-QOF | GP practices in Shropshire | Observational longitudinal study | Patients achieving QOF quality indicators pre-QOF | Pay-for-performance scheme (QOF) | Achievement of glycaemic control targets | Post-QOF, there was significant improvement in achieving glycaemic control targets in both large and small practices | Positive | 15 |

| Ryan et al (2016)40 | To assess whether the QOF was associated with reduced population mortality | UK population-level data | Retrospective cohort design | Combination of high-income countries not exposed to pay-for-performance | Pay-for-performance scheme (QOF) | The primary outcome was age-adjusted and sex-adjusted mortality per 100 000 people for chronic disorders that were targeted by the QOF. Secondary outcomes were age-adjusted and sex-adjusted mortality for ischaemic heart disease, cancer, and a composite of all non-targeted conditions | Introduction of the QOF was not significantly associated with changes in population mortality for the composite outcome or all non-targeted conditions | No effect | 19 |

| Pape et al (2015)35 | To assess the impact of a local version of the QOF in patients with cardiovascular disease and diabetes | General practices in Hammersmith and Fulham | Difference-in-differences analysis | Performance in the 2 years before the QOF; national comparison | A local version of the QOF | Mean values and achievement of clinical targets for BP, total cholesterol, and HbA1c levels | The intervention led to significantly higher target achievements for hypertension, CHD, and stroke. However, the increase was driven by higher rates of exception reporting for all conditions except for stroke. There were no statistically significant improvements in mean BP, cholesterol, or HbA1c levels. Achievement of targets was mainly attributed to increased exception reporting by practices with no clear improvements in overall clinical quality | Intermediate | 17 |

| McDonald et al (2015)19 | To identify the impact of the Advancing Quality Programme on key stakeholders and clinical practice in the north-west region of England | Hospitals in the north-west region of England | Between-region difference-in-differences analysis; triple-difference analysis | Comparison with the rest of England, comparison with non-incentivised conditions | Advancing Quality pay-for-performance programme | Risk-adjusted mortality rates for pneumonia, heart failure, and myocardial infarction | The Advancing Quality incentive was associated with significant reductions in mortality during the first 18 months of the programme. Findings at 42 months are less clear, with the possibility that short-term improvements were not sustained | Intermediate | 19 |

| Lee et al (2011)36 | To assess whether the QOF resulted in a change in the quality of care for CHD, stroke, and hypertension in white, black, and South Asian patients; and whether the QOF reduced disparities in the quality of care | General practices in Wandsworth, London, England. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series to account for previous time trend | Retrospective cohort | Baseline trend 2000–2003 | Pay-for-performance scheme (QOF) | Systolic and diastolic BP and cholesterol | The QOF resulted in significant short-term improvements in BP control. Benefit varied between ethnic groups. There was a statistically significant short-term reduction in systolic BP in white and black, but not in South Asian, patients with hypertension. There were no statistically significant reductions in cholesterol level in any ethnic group in patients with stroke | Intermediate | 16 |

| Hamilton et al (2016)37 | To assess the impact of a local-version QOF on smoking-cessation activities, and on inequalities in the provision of cessation advice | General practices in Hammersmith and Fulham, London, England | Before and after study | Performance 27 months pre-QOF | Local version of the QOF | Smoking status recorded, receipt of smoking cessation advice, smoking status | Recording of smoking status significantly increased for males and females. Younger patients remained less likely to be asked about smoking than older patients. White patients were less likely to be asked than those from other ethnic groups. Smoking-cessation advice significantly increased for men and women. Smoking prevalence significantly reduced for men and for women. White patients and those from more deprived areas remained more likely to be smokers than other groups | Intermediate | 16 |

| Hamilton et al (2010)38 | To assess the impact of the QOF on quality of diabetes management within age, sex, and socioeconomic groups | General practices | Retrospective cohort study | Performance pre-QOF (1997–2003) | Pay-for-performance scheme (QOF) | Achievement of national targets for HbA1c levels, BP, and total cholesterol | Post-QOF, disparities in HbA1c levels, BP, and cholesterol narrowed between men and women. Younger patients < (45 years) with diabetes benefited less from the QOF than older patients, resulting in a widening of age-group disparities. Patients living in affluent and deprived areas derived a similar level of benefit from pay for performance | Intermediate | 18 |

| Fichera et al (2016)26 | To assess whether the introduction of the QOF affected the population’s weight, smoking, and drinking behaviours | General practices | Regression discontinuity design | Population weight, smoking, and drinking behaviours pre-QOF | Pay-for-performance scheme (QOF) | Population weight, smoking, and drinking behaviours | Post-QOF, individuals with the targeted health conditions improved their lifestyle behaviours. This was only statistically significant for smoking, which reduced by 0.7 cigarettes per person per day, equal to 18% of the mean | Positive | 18 |

| Allen et al (2016)17 | To asses the effects of the new Best Practice Tariff on patient care for patients undergoing cholecystectomy | Hospitals in England | Difference-in-differences and differential spline analyses between the pre-2010 payment policy and the post-2010 payment policy | Performance before the 2010 payment policy (24 months before). Control group comprising other procedures for which similar day-case rates are recommended but a separate day-case price was not introduced | Best practice tariff | Proportion of cholecystectomies occurring as a day-case procedure, proportion performed laparoscopically, re-admission rates, death rates, length of stay | The tariff led to an almost 6% increase in the day-case rate. Patients benefited from a lower proportion of procedures reverted to open surgery during a planned laparoscopic procedure and from a reduction in long stays. There was no evidence that readmission and death rates were affected | Positive | 18 |

| Sutton et al (2012)16 | To assess the association of the Advancing Quality pay-for-performance programme with 30-day hospital mortality | 24 hospitals in the north-west region in England providing emergency care | Difference-in-differences regression analysis to compare mortality 18 months before and after introduction of the programme | Mortality in patients admitted for pneumonia, heart failure, or acute myocardial infarction, and mortality in patients with six other conditions in the 132 other hospitals in England | Advancing Quality pay-for-performance programme | 30-day in-hospital mortality; potential effects on six clinical conditions not incentivised by the scheme (acute renal failure, alcoholic liver disease, intracranial injury, paralytic ileus, and duodenal ulcer) | Mortality for conditions included in the Advancing Quality scheme decreased significantly during the 18-month period. The largest reduction was for pneumonia, with non-significant reductions for acute myocardial infarction and heart failure | Positive | 19 |

| Sutton et al (2010)21 | To estimate the effects of the QOF on quality of care provided over the period 2000/2001– 2005/2006 | General practices | Dynamic panel probit models using individual patient records from 315 general practices over the period 2000/2001– 2005/2006 | Scottish Programme for Improving Clinical Effectiveness in Primary Care (SPICE-PC) data before the introduction of the QOF | Pay-for-performance scheme (QOF) | Annual recording of BP, smoking status, cholesterol, body mass index, and alcohol consumption | The rates of recording increased for all risk factor groups post QOF. The effect on incentivised factors was larger on the targeted patient groups (19.9 percentage points) than on the untargeted groups (5.3 percentage points) | Positive | 15 |

| Kreif et al (2016)20 | To assess the Advancing Quality pay-for-performance programme on quality of care | 24 hospitals in the north-west region in England providing emergency care | Re-analysis of data from Sutton et al (2012), using the synthetic control method | Mortality in patients admitted for pneumonia, heart failure, or acute myocardial infarction, and mortality in patients with six other conditions (acute renal failure, alcoholic liver disease, intracranial injury, paralytic ileus, and duodenal ulcer) in the 132 other hospitals in England | Advancing Quality pay-for-performance programme | 30-day in-hospital mortality for incentivised conditions (pneumonia, heart failure, and acute myocardial infarction), and mortality for six clinical conditions not incentivised by the scheme (acute renal failure, alcoholic liver disease, intracranial injury, paralytic ileus, and duodenal ulcer) | For the incentivised conditions, the pay-for-performance scheme did not significantly reduce mortality and there was a statistically significant increase in mortality for non-incentivised conditions | Negative | 19 |

| Alshamsan et al (2012)34 | To examine the long-term effects of the QOF on ethnic disparities in diabetes outcomes | General practices | Interrupted time series analysis | Patient data before the intervention (2000–2004) | Pay-for-performance scheme (QOF) | Annual recording of BP, cholesterol, and HbA1c levels | Before introduction of the QOF, HbA1c levels were decreasing in all three ethnic groups. Post-QOF, HbA1c levels significantly increased in each ethnic group when compared with the pre-QOF trend. Pre-QOF mean cholesterol was decreasing in all ethnic groups. The QOF was initially followed by significant additional reductions in cholesterol levels in white and black patients, but not in South Asian patients. Over the next 3 years, the trend for cholesterol remained the same for black and South Asian patients, but significantly increased in white patients. The QOF was associated with initial improvements in systolic BP in white and black patients, but these improvements were only sustained in black patients. Initial improvements in diastolic BP in white patients were not sustained post-QOF | Intermediate | 15 |

| Vamos et al (2011)33 | To estimate the impact of the QOF on quality of diabetes care | General practices | Interrupted time series analysis | Baseline trend pre-QOF (1997–2003) | Pay-for-performance scheme (QOF) | Achievement of national treatment targets for BP, HbA1c levels, and cholesterol | Post-QOF, compared with underlying trends, there were significant improvements in reaching national targets for cholesterol and BP, but not for HbA1c level | Intermediate | 15 |

| Millett et al (2009)27 | To assess the impact of the QOF on diabetes management | General practices | Cohort study comparing 2004 and 2005 treatment target results with that of the predicted underlying (pre-intervention) trend in patients with diabetes | Predicted underlying (pre-intervention) trend in diabetes patients | Pay-for-performance scheme (QOF) | Achievement of diabetes treatment targets for BP, HbA1c levels, and cholesterol | During the first 2 years of pay-for-performance, there was an increase in the percentage of patients with diabetes and comorbidities that reached BP and cholesterol targets (3.1% for BP and 4.1% for cholesterol). Similar improvements were found in patients with diabetes without comorbidity, except for cholesterol control in 2004 (−0.2% [95% CI = −1.7 to 1.4) The percentage of patients meeting the HbA1c-level target in the first 2 years of pay-for-performance was significantly lower than predicted | Intermediate | 17 |

| Millett et al (2007)23 | To assess the clinical outcomes of patients with diabetes before and after the introduction of the new pay-for-performance scheme in primary care | General practices | Population-based longitudinal survey, using electronic general practice records | Population before the introduction of the incentive | Pay-for-performance scheme (QOF) | Achievement of national treatment targets for HbA1c levels, BP, and total cholesterol | There was a significant increase in the number of patients reaching treatment targets for HbA1c levels, BP, and total cholesterol post-implementation of the new contract | Positive | 17 |

| Gulliford et al (2007)22 | To assess whether diabetic metabolic targets improved after the new GP pay-for-performance scheme | General practices | Retrospective cohort study and cross-sectional study | Population data trends over time pre-intervention (2000–2005) | Pay-for-performance scheme (QOF) | Achievement of national treatment targets for HbA1c levels, cholesterol, and BP | The proportion of patients achieving targets for HbA1c levels, BP, and cholesterol increased each year, with the biggest increase in 2005 (post-intervention) | Positive | 17 |

| Campbell et al (2007)28 | To assess whether quality improvement after the GP pay-for-performance contract reflects improvements that were already under way, or if improvements were accelerated | General practices | Longitudinal cohort study | Primary care practices in England at two time points (1998 and 2003) before pay-for-performance programme | Pay-for-performance scheme (QOF) | Quality of clinical care for CHD (15 indicators), asthma (12 indicators), and diabetes (21 indicators). An overall score for quality of care was calculated for each patient | Quality of care for CHD, asthma, and diabetes improved between 2003 and 2005, continuing the earlier trend. The increase in the rate of improvement between 2003 and 2005 was statistically significant for asthma (P<0.001) and diabetes (P = 0.002). Although the rate of improvement of CHD scores increased, this was not statistically significant (P= 0.07) | Intermediate | 19 |

| Calvert et al (2009)29 | To examine the management of diabetes between 2001 and 2007, and to assess whether changes in the quality of care in diabetes management in the UK reflected existing trends or were a result of the QOF | General practices | Retrospective cohort study | Cohort of patients 3 years pre-QOF | Pay-for-performance scheme (QOF) | Annual prevalence of diabetes. Glycaemic control, cholesterol levels, BP levels 3 years pre-and 3 years post-QOF | Significant improvements in outcomes were observed during the 6-year period with yearly improvements pre-QOF. Post-QOF, rates of improvement in glycaemic control, cholesterol levels, and BP reduced. The QOF did not result in improved quality of care in patients with type 1 diabetes, and did not reduce the number of patients with type 2 diabetes who had HbA1c levels >10%. Introduction of the QOF may have increased the number of patients with type 2 diabetes and HbA1c levels of ≤ 7.5% | Intermediate | 15 |

| Campbell et al (2009)11 | To assess quality of care improvement post-introduction of the GP pay-for-performance scheme. To report on trends in patient reports of communication with their doctor, on access to care, and on continuity of care | General practices | Interrupted time series analysis and patient questionnaires | Family practices at two time points (1998 and 2003) pre-introduction of the pay-for-performance programme | Pay-for-performance scheme (QOF) | Overall clinical quality score for each patient (the number of indicators for which appropriate care was provided, divided by the number of indicators relevant to that patient) | Quality of care for asthma and diabetes increased between 2003 and 2005 (P<0.001). Quality of care did not increase for heart disease. By 2007, rate of improvement slowed for all conditions (P<0.001) and the quality of aspects of care not associated with an incentive reduced for patients with asthma or heart disease. When compared with the pre-QOF improvement rate, the improvement rate post-2005 was unchanged for asthma or diabetes and was reduced for heart disease (P= 0.02). No significant changes were seen in patients’ reports on access to care or on interpersonal aspects of care. The level of continuity of care, which had been constant, reduced immediately post-QOF (P<0.001) and continued at that reduced level | Intermediate | 19 |

| Kontopantelis et al (2013)41 | To assess the effect of the QOF on incentivised aspects of diabetes care for patients, on variation in the impact depending on patient/practice characteristics, and on inequalities of care | General practices | Interrupted time series analysis | Data for patients at three pre-implementation time points (2000/2001, 2001/2002, and 2002/2003) | Pay-for-performance scheme (QOF) | 17 QOF diabetes indicators | Quality of care improved pre-QOF. In the first year of the QOF, quality improved 14.3% more than the pre-incentive trend. By the third year, the improvement-above trend was smaller, but still statistically significant (7.3%). After 3 years of QOF incentives, levels of care varied significantly for patient sex, age, years of previous care, number of comorbidities, and practice diabetes prevalence | Positive | 19 |

| Millett et al (2009)30 | To asses the effect of the QOF on the quality of diabetes care in ethnic groups in an urban setting in the UK | Urban setting, south-west London, England | Longitudinal cohort study | Data collected pre QOF (June–October 2013) | Pay-for-performance scheme (QOF) | Mean BP and HbA1c levels | Introduction of the QOF was followed by reductions in mean BP. These reductions were significantly greater than those predicted by the trend in the white, black, and South Asian groups. HbA1c levels were significantly lower than those predicted by the trend in the white group, but not in the black or South Asian groups. The degree of improvement differed between ethnic groups, potentially indicating increasing inequity in care | Intermediate | 17 |

| Serumaga et al (2011)39 | To assess the effect of the QOF on quality of care of patients with hypertension | Primary care | Interrupted time series analysis | Data collected 3 years pre-QOF | Pay-for-performance scheme (QOF) | BP centiles, BP monitoring and control, BP treatment intensity, incidence of hypertension-related outcomes, all-cause mortality. Quality of care for patients with hypertension was stable or improving pre-QOF | The QOF incentive did not result in changes in BP monitoring, control, or treatment intensity. The QOF had no effect on incidence of stroke, myocardial infarction, renal failure, heart failure, or all-cause mortality | No effect | 18 |

| Doran et al (2011)32 | To examine changes in performance post-QOF for activities that were, and were not, part of the scheme | Primary care | Longitudinal analysis of achievement rates | Projected trends pre-incentive (2000/2001– 2002/2003) | Pay-for-performance scheme (QOF) | Achievement rates of selected quality indicators | In the pre-QOF period, achievement rates improved for most indicators. In the first year of the QOF scheme (2004/2005), there were significant increases in rate of improvement (22 of the 23 incentivised indicators). This rate of improvement plateaued after 2004/2005, but quality of care in 2006/2007 remained higher than that predicted by pre-incentive trends for 14 incentivised indicators. For non-incentivised indicators, there was no effect on performance in the first year of the QOF scheme but, by 2006/2007, achievement rates were significantly below those predicted by pre-incentive trends | Intermediate | 16 |

| Tahrani et al (2007)24 | To assess the impact of the QOF on the quality of diabetes care in Shropshire | Primary care | Observational retrospective study | Data on quality indicator achievement 15 months pre-QOF | Pay-for-performance scheme (QOF) | Achievement rates of selected quality indicators | There were significant improvements in the number of patients achieving quality targets post-QOF | Positive | 15 |

| Steel et al (2007)31 | To assess the relationship between the introduction of the QOF and changes in recorded quality of care | Primary care | Observational retrospective study | Data on quality indicators collected pre-QOF (2003) | Pay-for-performance scheme (QOF) | Achievement rates of selected quality indicators for asthma, hypertension, osteoarthritis, and depression | There were significant increases (P<0.01) in achievement rates for the six indicators linked to incentive payments: from 75% (2003) to 91% (2005). There was a significant increase (P<0.01) for 15 other indicators linked to ‘incentivised conditions’: from 53% (2003) rates to 64% (2005). Achievement of non-incentivised conditions did not increase significantly (P= 0.19): 35% (2003) to 36% (2005). | Intermediate | 16 |

Based on Downs and Black quality assessment checklist.14 BP = blood pressure. CHD = coronary heart disease. HbA1c = glycated haemoglobin. PbR = Payment by Results. QOF = Quality and Outcomes Framework.

Funding

This study received no funding.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Jarman B. Quality of care and patient safety in the UK: the way forward after Mid Staffordshire. Lancet. 2013;382(9892):573–575. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61726-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshall L, Charlesworth A, Hurst J. The NHS payment system: evolving policy and emerging evidence. London: Nuffield Trust; 2014. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/the-nhs-payment-system-evolving-policy-and-emerging-evidence (accessed 7 Jun 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsai TC, Jha AK, Gawande AA, et al. Hospital board and management practices are strongly related to hospital performance on clinical quality metrics. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(8):1304–1311. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roland M, Dudley RA. How financial and reputational incentives can be used to improve medical care. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(Suppl 2):2090–2115. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petersen LA, Woodard LD, Urech T, et al. Does pay-for-performance improve the quality of health care? Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(4):265–272. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine . Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christianson J, Leatherman S, Sutherland K. Financial incentives, healthcare providers and quality improvements. London: Health Foundation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallagher N, Cardwell C, Hughes C, O’Reilly D. Increase in the pharmacological management of type 2 diabetes with pay-for-performance in primary care in the UK. Diabet Med. 2015;32(1):62–68. doi: 10.1111/dme.12575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott A, Sivey P, Ait Ouakrim D, et al. The effect of financial incentives on the quality of health care provided by primary care physicians. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;9:CD008451. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008451.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maynard A, Bloor K. Will financial incentives and penalties improve hospital care? BMJ. 2010;340:c88. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell SM, Reeves D, Kontopantelis E, et al. Effects of pay for performance on the quality of primary care in England. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(4):368–378. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0807651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dudley RA, Miller RH, Korenbrot TY, Luft HS. The impact of financial incentives on quality of health care. Milbank Q. 1998;76(4):649–686. 511. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Altman DG, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J. PRISMA statement. Epidemiology. 2011;22(1):128. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181fe7825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farrar S, Yi D, Sutton M, et al. Has payment by results affected the way that English hospitals provide care? Difference-in-differences analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b3047. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sutton M, Nikolova S, Boaden R, et al. Reduced mortality with hospital pay for performance in England. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(19):1821–1828. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1114951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allen T, Fichera E, Sutton M. Can payers use prices to improve quality? Evidence from English hospitals. Health Econ. 2016;25(1):56–70. doi: 10.1002/hec.3121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kristensen SR, Meacock R, Turner AJ, et al. Long-term effect of hospital pay for performance on mortality in England. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(6):540–548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDonald R, Boaden R, Roland M, et al. A qualitative and quantitative evaluation of the Advancing Quality pay-for-performance programme in the NHS North West. Health Services and Delivery Research. 2015;3:23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kreif N, Grieve R, Hangartner D, et al. Examination of the synthetic control method for evaluating health policies with multiple treated units. Health Econ. 2016;25(12):1514–1528. doi: 10.1002/hec.3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sutton M, Elder R, Guthrie B, Watt G. Record rewards: the effects of targeted quality incentives on the recording of risk factors by primary care providers. Health Econ. 2010;19(1):1–13. doi: 10.1002/hec.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gulliford MC, Ashworth M, Robotham D, Mohiddin A. Achievement of metabolic targets for diabetes by English primary care practices under a new system of incentives. Diabet Med. 2007;24(5):505–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Millett C, Gray J, Saxena S, et al. Ethnic disparities in diabetes management and pay-for-performance in the UK: the Wandsworth Prospective Diabetes Study. PLoS Med. 2007;4(6):e191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tahrani AA, McCarthy M, Godson J, et al. Diabetes care and the new GMS contract: the evidence for a whole county. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(539):483–485. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tahrani AA, McCarthy M, Godson J, et al. Impact of practice size on delivery of diabetes care before and after the Quality and Outcomes Framework implementation. Br J Gen Pract. 2008. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp08X319729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Fichera E, Gray E, Sutton M. How do individuals’ health behaviours respond to an increase in the supply of health care? Evidence from a natural experiment. Soc Sci Med. 2016;159:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Millett C, Bottle A, Ng A, et al. Pay for performance and the quality of diabetes management in individuals with and without co-morbid medical conditions. J R Soc Med. 2009;102(9):369–377. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2009.090171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell S, Reeves D, Kontopantelis E, et al. Quality of primary care in England with the introduction of pay for performance. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(2):181–190. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr065990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calvert M, Shankar A, McManus RJ, et al. Effect of the quality and outcomes framework on diabetes care in the United Kingdom: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;338:b1870. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Millett C, Netuveli G, Saxena S, Majeed A. Impact of pay for performance on ethnic disparities in intermediate outcomes for diabetes: a longitudinal study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(3):404–409. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steel N, Maisey S, Clark A, et al. Quality of clinical primary care and targeted incentive payments: an observational study. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(539):449–454. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doran T, Kontopantelis E, Valderas JM, et al. Effect of financial incentives on incentivised and non-incentivised clinical activities: longitudinal analysis of data from the UK Quality and Outcomes Framework. BMJ. 2011;342:d3590. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vamos EP, Pape UJ, Bottle A, et al. Association of practice size and pay-for-performance incentives with the quality of diabetes management in primary care. CMAJ. 2011;183(12):E809–E816. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alshamsan R, Lee JT, Majeed A, et al. Effect of a UK pay-for-performance program on ethnic disparities in diabetes outcomes: interrupted time series analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(3):228–234. doi: 10.1370/afm.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pape UJ, Huckvale K, Car J, et al. Impact of ‘stretch’ targets for cardiovascular disease management within a local pay-for-performance programme. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119185. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee JT, Netuveli G, Majeed A, Millett C. The effects of pay for performance on disparities in stroke, hypertension, and coronary heart disease management: interrupted time series study. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e27236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamilton FL, Laverty AA, Huckvale K, et al. Financial incentives and inequalities in smoking cessation interventions in primary care: before-and-after study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(3):341–350. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamilton FL, Bottle A, Vamos EP, et al. Impact of a pay-for-performance incentive scheme on age, sex, and socioeconomic disparities in diabetes management in UK primary care. J Ambul Care Manage. 2010;33(4):336–349. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e3181f68f1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serumaga B, Ross-Degnan D, Avery AJ, et al. Effect of pay for performance on the management and outcomes of hypertension in the United Kingdom: interrupted time series study. BMJ. 2011;342:d108. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ryan AM, Krinsky S, Kontopantelis E, Doran T. Long-term evidence for the effect of pay-for-performance in primary care on mortality in the UK: a population study. Lancet. 2016;388(10041):268–274. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kontopantelis E, Reeves D, Valderas JM, et al. Recorded quality of primary care for patients with diabetes in England before and after the introduction of a financial incentive scheme: a longitudinal observational study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(1):53–64. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Houle SK, McAlister FA, Jackevicius CA, et al. Does performance-based remuneration for individual health care practitioners affect patient care? A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(12):889–899. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-12-201212180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flodgren G, Eccles MP, Shepperd S, et al. An overview of reviews evaluating the effectiveness of financial incentives in changing healthcare professional behaviours and patient outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD009255. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Markovitz AA, Ryan AM. Pay-for-performance: disappointing results or masked heterogeneity? Med Care Res Rev. 2016. Jan 7, p. pii. 1077558715619282. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Mendelson A, Kondo K, Damberg C, et al. The effects of pay-for-performance programs on health, health care use, and processes of care: a systematic review. Ann Int Med. 2017;166(5):341–353. doi: 10.7326/M16-1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lindenauer PK, Remus D, Roman S, et al. Public reporting and pay for performance in hospital quality improvement. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):486–496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maisey S, Steel N, Marsh R, et al. Effects of payment for performance in primary care: qualitative interview study. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2008;13(3):133–139. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2008.007118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamblin R. Regulation, measurements and incentives. The experience in the US and UK: does context matter? J R Soc Promot Health. 2008;128(6):291–298. doi: 10.1177/1466424008096617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]