Abstract

Choices have consequences. Immune cells survey and migrate throughout the body and sometimes take residence in niche environments with distinct communities of cells, extracellular matrix, and nutrients that may differ from those in which they matured. Imbedded in immune cell physiology are metabolic pathways and metabolites that not only provide energy and substrates for growth and survival, but also instruct effector functions, differentiation, and gene expression. This review of immunometabolism will reference the most recent literature to cover the choices that environments impose on the metabolism and function of immune cells and highlight their consequences during homeostasis and disease.

INTRODUCTION

Cells of the immune system possess particular sets of skills – skills that are vital for host defense and tissue homeostasis, but also cause disease if not properly controlled – skills that make them altogether fairly peculiar. Unlike other cells in the body, immune cells possess the ability to respond to environmental signals and assume a wide variety of distinct functional fates. Immune cells can morph from dormant sentinels into pathogen killing machines, migrate from one tissue to another, modulate surface receptor expression, clonally expand, secrete copious amounts of effector molecules, or exert controlling effects over neighboring cells. After the burst of activity following an immune response, these specialized cells can die, creating space and limiting tissue damage in a particular environment, or return to resting states that allow them to persist for extended periods of time in readiness for a secondary response.

The activation, growth and proliferation, engagement of effector functions, and return to homeostasis of immune cells are intimately linked and dependent on dynamic changes in cellular metabolism. The utilization of particular metabolic pathways is controlled on one level by growth factors and nutrient availability dictated by competition between other interacting cells, and on another level by the exquisite balance of internal metabolites, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and reducing and oxidizing substrates. Studying immune cells, particularly lymphocytes and myeloid cells, has lent deep insight into how cells differentiate and coordinate their behaviors with metabolism under a wide array of settings.

Leukocytes are also nomads and settlers. They migrate from the place where they develop to survey the entire body, and sometimes take up residence in tissues in which they did not originate. In doing so, they must adapt to an ecosystem comprised of unique cells, extracellular matrix, growth factors, oxygen, nutrients, and metabolites. How do they do this and what are the genetic, metabolic, and immunological consequences of these adaptations? In this review, we explore the interactions between immune cells and the tissue environments they inhabit, how these impinge on their metabolism, how their metabolism instructs their function and fate, and how these relationships contribute to tissue homeostasis and disease pathology. The central concepts of immune cell metabolism have been covered extensively in several reviews (Buck et al., 2015; MacIver et al., 2013; O’Neill and Pearce, 2016; O’Neill et al., 2016; Pearce et al., 2013), and thus will not be discussed at length here.

THE TUMOR MICROENVIRONMENT

Recent breakthroughs in immunotherapy have shown that eliciting immune responses against multiple types of cancer can lead to considerably longer-lasting remissions, or in some cases complete regression of metastatic disease (Ribas, 2015). Although it is well known that cancer cells can evade immune recognition through “immunoediting”, the process by which antitumor immune responses, especially those from tumor infiltrating T lymphocytes (TILs), select for cancer cell clones that no longer express detectable tumor antigens (Vesely and Schreiber, 2013), the advent of effective cancer immunotherapies has shown that additional mechanisms of immunosuppression exist that limit or impair antitumor immunity. Thus, considerable efforts are underway to elucidate other mechanisms that restrain antitumor responses to develop new and more efficacious forms of therapy.

At the forefront of these mechanisms to consider is how immune cell metabolism, and thus immune cell function, is altered by the tumor microenvironment. Tumors are a major disturbance to tissue homeostasis, creating metabolically demanding environments that encroach on the metabolism and function of the stroma and infiltrating immune cells. The unrestrained cell growth seen in cancer is often supported by aerobic glycolysis, the same metabolic pathway needed to fuel optimal effector functions in many immune cells (Pearce et al., 2013). At minimum, this similarity creates a competition for substrates between tumors and immune cells. The demand for nutrients, essential metabolites, and oxygen imposed by proliferative cancer cells, in combination with their immunosuppressive by-products, creates harsh environmental conditions in which immune cells must navigate and adapt (Figure 1). How tumor and immune cells share or compete for resources in this environment, and how such relationships regulate antitumor immunity are important questions to address.

Figure 1. Metabolic tug-of-war within the tumor microenvironment.

The balance of nutrients and oxygen within the tumor microenvironment controls immune cell function. Glucose and amino acid consumption by tumor cells can outpace that of infiltrating immune cells, specifically depriving them of nutrients to fuel their effector function. Poorly perfused tumor regions drive hypoxia response programs in tumor cells, macrophages, and T cells. Increased HIF-1α activity in response to hypoxia or other mechanisms promotes glycolysis and increases concentrations of suppressive metabolites and acidification of the local environment. As a by-product of glycolysis, lactate concentration increases, which is coordinately utilized by tumor cells to fuel their metabolism, promotes macrophage polarization, and directly suppresses T cell function. The ability of T cells to target tumors is further limited by their upregulation of co-inhibitory receptors and engagement with their ligands on neighboring tumor cells and macrophages. As T cells progressively enter a dysfunctional state, their mitochondrial mass and oxidative capacity declines ultimately leading to their failure to meet bioenergetic demands to sustain effector functions and control tumor cell growth.

Hypoxia

When tumor growth exceeds the vasculature’s ability to fully perfuse the tumor microenvironment with oxygen, regions of hypoxia are established and induction of the hypoxia-responsive transcription factor HIF-1α intensifies cancer cell glucose utilization and lactate release (Eales et al., 2016). Using 13C-labeled glucose, Hensley and colleagues traced the fate of glucose within healthy lung tissue and tumors of patients with non-small lung cell carcinoma and found that even within a single tumor, heterogeneity in glucose utilization exists (Hensley et al., 2016). Lesser-perfused regions of the lung tumors were associated with higher glucose metabolism whereas higher-perfused regions could utilize circulating lactate, transported through monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1), as an alternative TCA cycle substrate (Sonveaux et al., 2008). Lactate metabolism in oxygenated cancer cells also increases glutaminolysis (Pérez-Escuredo et al., 2015). How this metabolic heterogeneity in tumor cells relates to intratumoral immune cell function has not been well elucidated, but exposure of NK and T cells to high concentrations of lactate impairs their activation of the transcription factor NFAT and production of the cytokine IFN-γ (Brand et al., 2016). Lactic acid also disrupts T cell motility and causes loss of cytolytic function in CD8 T cells (Haas et al., 2015). Moreover, decreasing conversion of pyruvate to lactate by genetic targeting of lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) in tumors helps to restore T cell infiltration and function (Brand et al., 2016), linking lactate production to immunosuppression observed in the tumor microenvironment (Figure 1).

Lactate uptake by tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) also stimulates tumor progression by inducing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and arginase I (Arg1) expression through HIF-1α (Colegio et al., 2014). Moreover, chronic VEGF signaling in hypoxic areas leads to elevated glycolysis in endothelial cells, resulting in excessive endothelial sprouting and abnormal leaky vasculature (Goveia et al., 2014). Interestingly, inhibition of REDD1, a hypoxia-induced inhibitor of mTOR, in TAMs increases their rates of glycolysis to a level that competes with neighboring endothelial cells for glucose and suppresses their angiogenic activity. This metabolic tug-of-war over glucose helps restore vascular integrity, improve oxygenation within the tumor, and prevent metastases (Wenes et al., 2016), providing an example of an intimate metabolic relationship that exists between cells in tumors.

Hypoxia also has considerable effects on TIL function, proliferation, and migration (Vuillefroy de Silly et al., 2016). Increases in HIF-1α activity by culturing T cells in physiologic normoxia (~3–5% O2), genetic deletion of von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) factor, or inhibiting activity of the oxygen-sensing prolyl-hydroxylase (PHD) family of proteins, enhances CD8 T cell glycolysis and effector functions and promotes antitumor immunity (Clever et al., 2016; Doedens et al., 2013; Finlay et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2011). HIF-1α is also needed for the production of the metabolite S-2-hydroxyglutarate (S-2HG), which can drive epigenetic remodeling in activated CD8 T cells and enhance IL-2 production and antitumor defenses (Tyrakis et al., 2016).

Thus, one may expect that hypoxia would potentiate HIF-1α activity and TIL effector functions in tumors, however this is not what is observed. In addition to signals received from TIL IFN-γ (Noman et al., 2014), HIF-1α also induces the expression of the suppressive ligand PD-L1 in tumor cells, TAMs, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and this can lead to TIL suppression via PD-1 (Figure 1). Moreover, recent work in both mouse and human tumors showed that CD8 TILs lose mitochondrial mass, membrane potential, and oxidative capacity, particularly within the most dysfunctional PD-1+ CD8 T cells (Scharping et al., 2016). The loss of mitochondrial function in TILs correlated with diminished expression of PPAR-gamma coactivator 1α (PGC1α) over time and a block in their proliferation and IFN-γ production. Perhaps severe hypoxia ultimately diminishes TIL effector functions. Indeed, respiratory supplementation of oxygen or treatment with metformin decreased intratumoral hypoxia and relieved several immunosuppressive features in the tumor microenvironment; the latter also served as an adjunct therapy that enhanced the antitumor effects of PD-1 blockade (Hatfield et al., 2015; Scharping et al., 2017). These findings suggest that remodeling the hypoxic tone in tumors may be an essential component to developing more efficacious forms of immunotherapy for patients.

Nutrient alterations and competition within the tumor microenvironment

Apart from hypoxia, the competition for nutrients and metabolites between tumor cells and infiltrating immune cells can be fierce, consequently influencing signal transduction, gene expression, and the metabolic activities of these neighboring cells. For example, tumor cells manipulate surrounding adipocytes to increase lipolysis to whet their appetite for fatty acids (Nieman et al., 2011). Cancer associated fibroblasts degrade tryptophan that not only starves immune cells in the local environment of an essential amino acid, but also leads to the production of the immunosuppressive metabolite kynurenine (Hsu et al., 2016). Moreover, glucose is a critical substrate for the antitumor functions of effector T cells and M1 macrophages, which both require engagement of aerobic glycolysis for their activation and full effector functions (Buck et al., 2015; O’Neill and Pearce, 2016). Augmented aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells and endothelial cells places immune cells and their neighbors at odds (Figure 1). Glucose deprivation represses Ca2+ signaling, IFN-γ production, cytotoxicity, and motility in T cells and pro-inflammatory functions in macrophages (Cham et al., 2008; Chang et al., 2013; Chang et al., 2015; Macintyre et al., 2014). Several recent studies have demonstrated that the glycolytic activities of cancer cells may restrict glucose utilization by TILs, thereby impairing antitumor immunity (Chang et al., 2015; Ho et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2015). Increasing glycolysis rates of tumor cells through overexpression of the glycolysis enzyme hexokinase 2 (HK2) suppressed glucose-uptake and IFN-γ production in TILs and created more immunoevasive tumors (Chang et al., 2015; Ho et al., 2015). Zhao and colleagues found that glucose restriction imposed by ovarian cancer leaves microRNA repression of the methyltransferase EZH2 intact in CD8 T cells, reducing their survival and functional capacity (Zhao et al., 2015). Thus, tumor cells can selfishly coerce or outcompete neighboring cells for glucose to supply their own metabolic demands in a manner that simultaneously suppresses immune defenses.

Amino acid deprivation in the tumor microenvironment serves as another metabolic checkpoint regulating antitumor immunity. Glutaminolysis in tumor cells is critical to replenish metabolites through anaplerotic reactions, which could result in competition for glutamine between tumor cells and TILs (Jin et al., 2015; Pérez-Escuredo et al., 2015). Glutamine controls mTOR activation in T cells and macrophages and is also a key substrate for protein O-GlcNAcylation and synthesis of S-2HG that regulate effector T cell function and differentiation (Sinclair et al., 2013; Swamy et al., 2016; Tyrakis et al., 2016). TAMs, MDSCs, and tolerizing dendritic cells (DCs) can suppress TILs through expression of essential amino acid (EAA)-degrading enzymes such as Arg1 and indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) (Figure 1) (Lee et al., 2002; Munn et al., 2002; Rodriguez, 2004; Uyttenhove et al., 2003). Indeed, inhibitors of Arg1 and IDO are under investigation as therapeutic targets in clinical trials (Adams et al., 2015). Several recent studies have highlighted the critical roles of other amino acids such as arginine, serine, and glycine in driving T cell expansion and antitumor activity, but how the availability of these fluctuate within the tumor microenvironment is not clear (Geiger et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2017). Currently, a knowledge gap exists on how the availability of various nutrients and metabolites vary across tumor types, genotypes, or even spatially within tumors to affect antitumor immune responses.

Bioactive lipids, modified lipoproteins, and cholesterol metabolism within the tumor are also important mediators of immune cell function. Like macrophages in atherosclerotic plaques, DCs in the tumor can accumulate oxidized lipoproteins through scavenger receptor mediated internalization and formation of lipid droplets, which can ultimately impair their ability to cross-present tumor antigens and activate T cells (Cubillos-Ruiz et al., 2015; Ramakrishnan et al., 2014). Expression of lectin-type oxidized LDL receptor 1 (LOX-1) selectively marks MDSCs and oxidized lipid uptake and lipoprotein metabolism contributes to their T cell suppressive functions (Condamine et al., 2016). In addition, blocking cholesterol esterification in TILs by targeting ACAT1 pharmacologically or genetically increases intracellular levels of cholesterol and confers superior T cell responses in a model of melanoma (Yang et al., 2016). It is possible that as immune cells adapt to different tumor microenvironments and the limited availability of “immune stimulatory” nutrients, they become more dependent on alternative fuel sources (such as fats or lactate) that are less conducive to supporting antitumor effector functions. In summary, more elaborate knowledge of these forms of metabolic cross talk or competition between cells within tumors is needed before one can begin to think about how to manipulate these relationships in a manner that alters tumor progression.

Metabolic Exhaustion in TILs and Checkpoint Blockade

As TILs adapt to the tumor microenvironment, they progressively lose their ability to respond to T cell receptor (TCR) stimuli, produce effector cytokines, and proliferate – a process termed functional exhaustion or hyporesponsiveness. This is in part due to the upregulation of several inhibitory receptors like PD-1, LAG3, TIGIT, and CTLA-4 that desensitize T cells to tumor antigens (Wherry and Kurachi, 2015) (Figure 1). PD-1, its ligand PD-L1, and CTLA-4 are important checkpoints for T cells in tumors and the targets of a new and powerful class of cancer treatments that elicit effective and durable responses in patients across multiple cancer types (Ribas, 2015). Interestingly, both chronic exposure to antigen or environmental triggers such as glucose deprivation can upregulate PD-1 (Chang et al., 2013; Wherry and Kurachi, 2015). PD-1 not only suppresses TCR, PI3K and mTOR signaling in T cells, but also dampens glycolysis and promotes fatty acid oxidation (FAO) – features that may enhance the accumulation of suppressive regulatory CD4 T (Treg) cells in tumors (Bengsch et al., 2016; Parry et al., 2005; Patsoukis et al., 2015). Indeed, blockade of PD-1 re-energizes anabolic metabolism and glycolysis in exhausted T cells in an mTORC1 dependent manner (Chang et al., 2015; Staron et al., 2014). This breathes caution into the types of drug combinations one may consider with α-PD-1:PD-L1 blockade or other forms of immunotherapy. Metabolic interventions, such as the use of mTOR inhibitors, must be targeted specifically to avoid unintended compromises of immune cell function. The PD-1:PD-L1 axis may also directly affect the metabolic activity of tumor cells (Figure 1). It was shown that PD-L1 expression correlated with the rates of glycolysis and the expression of glycolytic enzymes in those cells (Chang et al., 2015). Furthermore, checkpoint blockade antibodies including α-PD-L1 led to an increase in extracellular glucose in tumors in vivo that likely contributed to the improved TIL function and subsequent tumor regression observed. On this note, tumor cell-intrinsic PD-1 expression may counterintuitively increase intrinsic mTOR signaling and tumor growth (Kleffel et al., 2015). Collectively, these findings suggest there may be broader role of the PD-1:PD-L1 axis in cellular metabolism that extends beyond T cells.

Balancing metabolism and designing effective immunotherapies

Improving the proportion of patients that respond to immunotherapy is an intense area of study, ranging from the search for biomarkers of response, target discovery, to testing new combination therapies. Likely, the most effective therapies will coordinately target co-inhibitory receptor to ligand interactions and restore a T cells’ ability to utilize metabolic substrates necessary to sustain their effector functions. Although not discussed at length here, other factors impinging on immune cell metabolism that one should consider in designing anticancer immunotherapies are the accessibility of growth factor cytokines that modulate nutrient transporter expression on immune cells and the fact that immune cells migrate into tumors to exert their effector functions, a metabolically demanding process. When cells move, their intracellular architecture, controlled in part by the actin cytoskeleton, is continuously remodeled. In an elegant dissection of PI3K-dependent growth factor signaling in epithelial cells, Hu and colleagues found cytoskeletal dynamics and glycolysis to be uniquely intertwined (Hu et al., 2016). The authors showed that addition of growth factors or insulin activated Rac downstream of PI3K, causing a disruption of the actin cytoskeleton. Loss of this structural integrity released bound aldolase from filamentous F-actin, increasing its catalytic activity. Chemical and genetic inhibition of PI3K, Rac, or actin dynamics modulated glycolysis via mobilization of aldolase (Figure 2). It will be interesting in future studies to explore how other glycolytic enzymes or even the mitochondria in immune cells restructure their metabolic activity through changes in cytoskeletal morphology in response to growth factor or pathogen-derived signals and whether this regulatory circuit can be therapeutically targeted, especially since directed cellular migration is such an integral feature of how the disseminated immune system can focus its attention on points of infection or damage.

Figure 2. Recent highlights in the restructuring of intracellular architecture and metabolism.

Immune cell function is a product of their metabolic state. Growth factor signaling, actin rearrangement, and glucose metabolism are closely intertwined. Actin-bound aldolase can be freed from the cytoskeleton downstream of growth factor signaling to mediate glycolysis. Engagement of this pathway is central to the activation and downstream effector functions of DCs, M1 macrophages, and T cells. T cells can dynamically restructure their mitochondria through processes like mitochondrial fission and fusion to signal changes in metabolism and to promote their long-term survival in the transition to memory cells.

Additionally, manipulating metabolic enzyme expression to help T cells adapt to metabolic perturbations in the tumor microenvironment may be another viable strategy to improve antitumor immunity (Clever et al., 2016; Doedens et al., 2013; Ho et al., 2015; Scharping et al., 2016), especially for adoptive cell therapy, a personalized form of cancer treatment that allows for the manipulation and expansion of a patient’s antitumor T cells prior to re-infusion. Seemingly paradoxical is the observation that dampening effector T cell differentiation by impairing glycolysis and boosting mitochondrial FAO and OXPHOS, metabolic pathways which favor the formation of resting memory T cell populations, potentiates effector T cell survival and functional capacity against tumors used in adoptive cell therapy (Buck et al., 2016; Sukumar et al., 2013). On the one hand, the engagement of aerobic glycolysis by activated T cells generates by-products of intermediary metabolism that supply substrates used to build biomass and fuel proliferation, provides an avenue for cells to support the equilibrium of reducing and oxidizing equivalents used to release energy, such as NAD+/NADH, and regulates the efficient production of effector cytokines critical for tumor regression (Buck et al., 2015; Chang et al., 2015; Pearce et al., 2013). However, activation initiated by TCR ligation and binding with costimulatory molecules also augments OXPHOS in T cells (Chang et al., 2013; Sena et al., 2013). Mitochondria undergo biogenesis and take on a grossly punctate and dispersed morphology with expanded cristae junctions (Buck et al., 2016; Ron-Harel et al., 2016) (Figure 2). During this process, the mitochondrial proteome remodels itself to increase mitochondrial one-carbon metabolism. Knockdown of SHMT2, the first enzyme in this pathway, impairs CD4 T cell survival and proliferation in vivo (Ron-Harel et al., 2016). The generation of mitochondrial-derived ROS is also critical for the activation and expansion of antigen-specific T cells (Sena et al., 2013). As previously discussed, TILs that cannot sustain mitochondrial function have compromised functionality within the tumor microenvironment and rescuing mitochondrial biogenesis in effector T cells improves antitumor immunity (Bengsch et al., 2016; Scharping et al., 2016).

However, dampening regulators of glycolytic metabolism, such as mTOR or c-Myc, and increasing mitochondrial FAO-dependent OXPHOS favors the formation of long-lived memory T cells (Araki et al., 2009; Cui et al., 2015; O’Sullivan et al., 2014; Pearce et al., 2009; Pollizzi et al., 2016; van der Windt et al., 2012; Verbist et al., 2016) (Figure 2). More recent evidence postulates that while oxidative metabolism and FAO characterizes the generation of long-lived stable central memory T cells (Cui et al., 2015; O’Sullivan et al., 2014; Pearce et al., 2009; van der Windt et al., 2012), augmenting glycolysis genetically via VHL deletion favors the formation of effector memory T cells instead, which have low levels of TCF-1, a transcription factor that is expressed in stable populations of central memory T cells capable of self-renewal (Phan et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2010). It was also recently shown that activated lymphocytes unequally eliminate aged mitochondria in sibling cells and that this process can determine differentiation versus self-renewal (Adams et al., 2016). Maintenance of mitochondria in some cells was linked to anabolism, PI3K/mTOR activation, glycolysis, and inhibited autophagy while mitochondrial clearance in others was associated with catabolism, FoxO1 transcription factor activity, and self-renewal. Thus, mitochondrial maintenance can drive differentiation over self-renewal, illustrating how these organelles lie at the center of cell fate decisions.

In addition to mitochondrial stasis versus clearance, memory T cells also have distinct mitochondrial morphology from effector T cells. Effector T cells have more “fissed” mitochondria whereas memory T cells have more “fused” mitochondrial networks with tight cristae suggesting a requirement for mitochondrial fusion in memory T cell metabolism and homeostasis. Consistent with this observation, antigen-specific T cells lacking the inner mitochondrial membrane fusion protein Opa1 fail to generate memory T cells after bacterial infection and have impaired survival in vitro (Buck et al., 2016). The activation, proliferation, and function of Opa1 deficient effector T cells however, remain intact. Opa1−/− T cells have augmented rates of glycolysis and possess mitochondria with diminished OXPHOS efficiency and malformed cristae compared to controls. It was shown that in quiescent T cells, such as naïve and memory T cells, mitochondrial fusion ensured tight cristae associations that allowed for efficient electron transport chain (ETC) function (Figure 2). Tight cristae result in dense packing of ETC complexes, which have been found to associate in specialized configurations termed respiratory supercomplexes or respirasomes. Supercomplexes facilitate efficient transfer of electrons and minimize proton leak during ATP production (Cogliati et al., 2013). CD8 T cells express high levels of methylation-controlled J protein (MCJ), a member of the DnaJ family of chaperones (Champagne et al., 2016). MCJ localizes to the inner membrane of mitochondria and associates with complex I of the ETC. By doing so, it negatively regulates the assembly of complex I into supercomplexes. MCJ deficiency was found to enhance naïve and activated CD8 T cell OXPHOS and a unique attribute was its role in the secretion, but not the translation, of effector cytokines. Increased respiration efficiency improved the survival of MCJ−/− effector T cells, which also induced superior protective immunity against viral challenge.

Repurposing the knowledge gained from such studies, boosting oxidative capacity and efficiency through enforcement of mitochondrial fusion or dampening glycolysis with 2-DG, extends the survival and antitumor function of CD8 T cells in models of adoptive cell therapy (Buck et al., 2016; Sukumar et al., 2013). Although aerobic glycolysis initiates and sustains effector functions of activated T cells, augmenting metabolic pathways that support long-lived memory T cells improves T cell responses against tumors, demonstrating a need to strike a balance between these processes, seemingly trading off heightened activation and effector functions of TILs with their sustained functionality and increased survival in the tumor microenvironment. Indeed, modification of the signaling domains within chimeric antigen receptor T cells, used in an alternative form of adoptive cell therapy, with 4-1BB augments mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism, enhancing their persistence (Kawalekar et al., 2016). As our capability to selectively reprogram T cell metabolism and reinvigorate tumor-specific T cells improves, there is much promise to provide greater therapeutic benefits to more patients, especially to those with previously incurable cancers.

THE GUT ENVIRONMENT

While the tumor microenvironment is often depicted as nutrient restrictive, the mammalian gastrointestinal tract represents a metabolically rich and diverse tissue system. Its primary function is to digest and absorb nutrients with the aid of microbial species contained within the lumen. A single layer of epithelial cells is all that separates these commensal microbes from the rest of the body. The majority of intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) are absorptive enterocytes that digest and transfer nutrients, however additional specialized epithelial lineages exist with a diverse array of functions. For example, goblet and Paneth cells secrete mucins and antimicrobial peptides that fortify the barrier against potentially pathogenic microbes, microfold (M) and goblet cells assist in the transferring of luminal antigens across the epithelial barrier for sampling by mucosal DCs, and Tuft cells are important for sensing and responding to protozoa and helminths. Together with intestinal resident immune cells including innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs), helper T cells and B cells, a balancing act between barrier protection and microbial tolerance with surveillance and inflammation is maintained (Figure 3). While the relationship between gut commensal microbes and immune cell development and function and also how IECs interface with immune system regulation has recently been reviewed (Kurashima and Kiyono, 2017), we examine the unique constraints that this environment presents on cellular immunometabolism.

Figure 3. Model of metabolic relationships in the gastrointestinal tract.

The gut serves as a direct interface with the outside world and the foods we consume. A single epithelial cell layer separates the contents of the intestinal lumen from the lamina propria where DCs, macrophages, ILCs, and T cells reside. Peyer’s patches are interspersed along the epithelium, which in addition to supporting sampling of luminal antigens by DCs and M cells, house germinal centers that maturate IgA-secreting B cells with Tfh cell help. B cells augment glycolysis upon activation and depend on pyruvate import via Mpc2 for longevity as long-lived plasma cells (LLPCs). Plasma cell hunger for glucose may restrict this nutrient from Tfh cells, however Tfh cells downregulate glycolysis in response to expression of their lineage defining transcription factor Bcl6. In addition, GCs contain areas of hypoxia that impinge on B cell function like class switch recombination (CSR). Commensal bacteria produce metabolites such as short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) from the fermentation of dietary fiber, which influence B cell metabolism and promote IgA secretion. The presence of SCFAs and vitamins support maintenance of barrier function by promoting the development and survival of Tregs and ILCs, respectively. Homeostatic signals secreted by gut resident immune cells (e.g. IL-10) may also modulate metabolism and therefore control their activation state.

While IECs control the intake of nutrients from the luminal environment of the gut, a recent study provides evidence that the way they are structured and uniquely placed controls their metabolic activity and function (Kaiko et al., 2016). The layer of epithelia in the small intestine are organized into crypts and villi, which form invaginations that serve to optimize surface area whereby nutrients can be absorbed. At the base of the colonic crypt lie epithelial stem/progenitor cells that differentiate into specialized IECs as they migrate up the crypt-villus axis until they are eventually lost from the epithelial layer. This process of self-renewal from the crypt is continuous and therefore is a site of active proliferation (Kurashima and Kiyono, 2017). Kaiko, Ryu and colleagues screened microbiota derived products for their impact on intestinal epithelial progenitors and identified the short chain fatty acid (SCFA) butyrate as a potent inhibitor of intestinal stem cell proliferation at physiologic concentrations present within the lumen (Kaiko et al., 2016). They further found that differentiated colonocytes located at the forefront of the villi metabolized butyrate to fuel OXPHOS, thereby limiting its access to underlying progenitor cells, which do not readily utilize this substrate. Either removal of the ability to metabolize butyrate via deletion of acyl-CoA dehydrogenase or increased abundance of butyrate prevented the rapid regeneration of epithelial tissue after gut injury. Thus a combination of physical separation in the crypt and fermentation of butyrate by mature colonocytes protects the proliferating progenitor pool of IECs (Figure 3).

B and Tfh cell metabolism

Another unique structural feature of the gut are the Peyer’s patches, aggregates of gut associated lymphoid tissue (Reboldi and Cyster, 2016). Found in the small intestine, they represent a specialized lymphoid compartment continuously exposed to food- and microbiome-derived antigens. Due to this exposure, Peyer’s patches are rich in germinal centers (GCs), which are comprised of B, T, stromal, and follicular DCs. B cells segregate into zones where they undergo cycles of proliferation and differentiation and compete for signals directing class switch recombination (CSR) and survival from T follicular helper (Tfh) cells, allowing further maturation of the antibody repertoire.

Although the literature on B and Tfh cell metabolism is still developing, it has been shown that B cell activation induced by either α-IgM ligation or LPS increases Glut1 expression and glucose uptake downstream of PI3K and mTOR signaling (Caro-Maldonado et al., 2014; Doughty et al., 2006; Jellusova and Rickert, 2016; Lee et al., 2013; Woodland et al., 2008). Glycolysis and OXPHOS are augmented as well as mitochondrial mass (Caro-Maldonado et al., 2014; Doughty et al., 2006; Dufort et al., 2007). Increased glucose acquisition also fuels de novo lipogenesis necessary for B cell proliferation and growth of intracellular membranes. Inhibition of the fatty acid synthesis (FAS) enzyme ATP-citrate lyase in splenic B cells results in reduced expansion and expression of plasma cell differentiation markers (Dufort et al., 2014). Although apoptosis inducing factor (AIF) is required for T cell survival via ETC complex I function and respiration, AIF deficiency in B cells has no impact on their development or survival because of their reliance on glucose metabolism (Milasta et al., 2016). B cells cultured in galactose fail to expand unlike T cells, which can activate and proliferate in the presence of either galactose or glucose (Chang et al., 2013; Milasta et al., 2016). Glycogen synthase 3, which promotes the quiescence and survival of circulating naïve B cells, tempers increases in glycolytic metabolism downstream of CD40 costimulatory receptor signaling and sustains the survival of B cells subjected to glucose restriction (Jellusova et al., 2017). On the other hand, the transition to durable humoral immunity by long-lived plasma cells (LLPCs) was shown to be dependent on mitochondrial pyruvate import and metabolism (Figure 3). Glucose supports antibody glycosylation, but LLPCs acquire more glucose than their short-lived counterparts and their long-term survival is dependent on their ability to siphon glucose-derived pyruvate into the mitochondria during times of metabolic stress (Lam et al., 2016).

It is interesting to speculate that with the constant proliferation of GC B cells in the gut and the importance of glucose and glycolysis in activated plasma cells, access to glucose would become limiting for other cells that occupy this microniche. A few studies suggest that Tfh cells have evolved to be uniquely suited to survive under these constraints. It has been shown that Tfh cells have less mTORC1 activation and reduced glycolysis compared to Th1 cells (Ray et al., 2015). In part, this may be due to expression of their lineage defining transcription factor Bcl6, which can suppress glycolysis potentiated by c-Myc and HIF-1α (Johnston et al., 2009; Nurieva et al., 2009; Oestreich et al., 2014). Consistent with this, overexpression of Bcl6 reduces glycolysis in T cells, and inhibition of mTOR using shRNA favors Tfh cell development over Th1 cells in vivo after viral infection (Ray et al., 2015) (Figure 3). However, a more recent study using mice with conditional deletions of mTORC1 and mTORC2 via OX40 and CD4 cre recombinase observed a requirement of mTOR signaling in Tfh cell development and GC formation within Peyer’s patches (Zeng et al., 2016). The former applied retroviral mTOR shRNA, which requires T cells be fully activated prior to knockdown, while this more recent report used mice where mTOR was excised during T cell development or at the moment of T cell activation, which may explain the disparity between the studies.

In addition to possibly limiting quantities of glucose substrate within GCs, these microniches contain areas of hypoxia, resulting in HIF-1α activation (Abbott et al., 2016; Cho et al., 2016). B cells placed under hypoxic conditions had reduced activation induced deaminase expression and subsequently underwent less CSR to the pro-inflammatory IgG2c isotype when cultured in conditions that promote IgG production (Cho et al., 2016). In contrast, B cells cultured in IgA-promoting conditions during hypoxia were unaffected, yielding comparable levels of IgA to cells kept at normoxia and highlighting how lymphocyte function may be fine-tuned to varying oxygen tension in tissues (Figure 3). B cells isolated from mice with constitutive activation of HIF-1α by deletion of its suppressor VHL had defects in IgG2c production, which was attributed to diminished mTORC1 activation. B cells from Raptor deficient heterozygotes also yielded fewer IgG antibodies (Cho et al., 2016). A separate study found that the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin dampens CSR, yielding the formation of lower affinity, more cross reactive B cell antibodies, which offered broad protection against heterosubtypic flu infection (Keating et al., 2013). Both mTORC1 and HIF-1α promote aerobic glycolysis (O’Neill et al., 2016). However, the metabolic activities of the cells cultured under different isotype conditions while under hypoxia were not explored. A separate study examining mitochondrial function and specifically mitochondrial ROS found that B cells with augmented mitochondrial mass, respiration, and ROS stratified cells that underwent CSR marked by IgG1 expression apart from CD138+ plasma cells (Jang et al., 2015). The differences seen in mitochondrial function between the B cell populations were in part due to differential regulation of heme synthesis by mitochondrial ROS, however how the mitochondria affects CSR to other isotypes was not assessed. Cytokines initiate CSR to distinct isotypes and signals derived from these growth factors might be responsible for the differences in metabolic signaling and suggest varying requirements to initiate metabolic programs and CSR in B cells. Secretion of IgA predominates the gut and is critical to maintaining barrier protection and bacterial homeostasis (Kurashima and Kiyono, 2017). The apparent stability of CSR to the IgA isotype under hypoxia and impaired pro-inflammatory IgG2c subtype might have evolved to ensure tolerance with the microbiome, while concurrently providing a stringent method of selection of antibodies produced during inflammatory responses to pathogen-derived antigens.

Nutrients and immune signals in the gut

The metabolic relationship between commensals and immune cells in the gut is further illustrated by the finding that SCFAs derived from the fermentation of dietary fiber by gut microbiota promote B cell metabolism and boost antibody responses in both mouse and human B cells (Kim et al., 2016). Supplementation with dietary fiber or the SCFAs acetate, propionate, and butyrate increases intestinal IgA production, as well as systemic IgG during infection (Figure 3). Culturing B cells with SCFAs was shown to raise acetyl-CoA levels and increase mitochondrial mass, lipid content, and FAS leading to increased plasma cell differentiation and metabolic activity (Kim et al., 2016). Part of this phenotype could be attributed to histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition, an established effect of SCFA supplementation.

In addition to their effects on B Cells, SCFAs can promote the development and function of colonic Treg cells via induction of Foxp3 in a HDAC dependent manner (Arpaia et al., 2013; Furusawa et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2013) (Figure 3). Treg cells are critical to maintaining commensal tolerance by the immune system through suppression of aberrant T cell responses. Unlike other activated T helper subsets, Treg cells have been described to primarily rely on OXPHOS driven by FAO (Newton et al., 2016). However, signals downstream of TLR ligation can augment glycolysis and proliferation of Treg cells and reduce their ability to suppress T cell responses (Gerriets et al., 2016). Retroviral enforced expression of Foxp3 promotes OXPHOS and dampens glucose uptake and glycolysis, whereas Treg cells transduced with Glut1 decreased Foxp3 expression after adoptive transfer in vivo and fail to suppress T cell-mediated colitis in a model of inflammatory bowel disease. These findings suggest that during inflammation and microbial infection, Treg cells may temporarily lose their regulatory function to give way to robust T cell responses and participate as more conventional effector helper T cells. Increases in NaCl either from supplementation in vitro or diet in vivo inhibit the suppressive function of human Treg cells via serum/glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 (SGK1), which integrates signals from PI3K and mTORC2 to regulate sodium controlled signal transduction (Hernandez et al., 2015). However, a study of human Treg cells found that the glycolytic enzyme enolase-1 was required for their suppressive activity through its control of Foxp3-E2 splice variants (De Rosa et al., 2015). Depending on environmental cues and metabolites, it appears that Treg cell metabolism can be modulated, affecting their function.

As discussed, increases in SCFAs either from diet, infection, or exogenous treatment impinge on metabolic processes including HDAC activation (Rooks and Garrett, 2016). A recent study suggests that activation of the HDAC sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) negatively impacts Th9 cell differentiation (Wang et al., 2016b). The exposure of CD4 T cells to distinct cytokine cocktails differentiates them into separate helper lineages. However, perturbing metabolism also modulates CD4 T cell fate. A yin and yang relationship between Th17 and Treg cell differentiation has been established. Th17 cells are particularly glycolytic and depend on engagement of this pathway downstream of mTOR and HIF-1α activation. Dampening glycolysis through deletion of HIF-1α or with the inhibitor 2-DG in T cells impairs Th17 development and instead promotes Treg cells, even under Th17-inducing culture conditions (Dang et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2011). Suppression of mTOR with rapamycin or genetic ablation also augments production of Treg cells (Delgoffe et al., 2009; Kopf et al., 2007), and pharmacological inhibition of de novo fatty acid synthesis prevents Th17 differentiation and instead enforces a Treg cell phenotype (Berod et al., 2014).

Although the metabolic characteristics of other CD4 T cell subsets have been compared (Michalek et al., 2011), little was known about Th9 cell metabolism. Th9 cells are characterized by their ability to produce IL-9 and can be generated from naïve cells in culture using the cytokines TGF-β and IL-4. They are implicated in autoimmunity, melanoma, and worm infections (Kaplan et al., 2015). Wang and colleagues found that Th9 cells are highly glycolytic, in part from their active suppression of SIRT1 expression via the kinase TAK1 (Wang et al., 2016b). SIRT1 was previously shown to negatively control HIF-1α as well as mTOR (Lim et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2013). In line with this, Th9 cell development was augmented in SIRT1-deficient T cells whereas retroviral enforced expression of SIRT1 or dampening of aerobic glycolysis by chemical or genetic means impaired Th9 cell differentiation (Wang et al., 2016b). Th9, Th17, and Treg cells all share the cytokine TGF-β for their development, but then depend on additional cytokine signals for their eventual fates. Given their divergent metabolic phenotypes, as well as HDAC requirements, it would be interesting to explore further whether variances in intracellular levels of SCFA metabolites for example, might couple with environment signals to influence their eventual metabolic and developmental pathway.

Apart from its effect on CD4 T cells, the SCFA acetate also has been shown to affect secondary recall responses from CD8 memory T cells (Balmer et al., 2016). Germ-free mice reconstituted with commensal microbes, or oral or systemic infection with bacterial species, elevated serum acetate concentrations. Memory T cells generated in vitro or in vivo cultured with acetate levels observed during these infections secreted more IFN-γ and augmented glycolysis after restimulation. Acetate can be quickly converted into acetyl-CoA, which can condense with oxaloacetate into citrate in the mitochondria to fuel the TCA cycle and OXPHOS, be used as a substrate for FAS, or participate in post translational modification (PTM) of proteins including histones (Pearce et al., 2013). Balmer and colleagues mechanistically tied their results to lysine acetylation of the glycolytic enzyme GAPDH. GAPDH activity has been shown to regulate T cell production of IFN-γ (Chang et al., 2013; Gubser et al., 2013). Although the study demonstrated that the enzymatic activity of GAPDH was altered by acetylation of K217, whether this PTM was critical to acetate-dependent increases in IFN-γ protein was not explored. In a separate report, CD4 T cells deficient in LDHA expression had defects in IFN-γ production, which stemmed from widespread lack of acetylation of the Ifng locus (Peng et al., 2016). LDHA is the critical enzyme that defines aerobic glycolysis, converting pyruvate to lactate. Culturing cells in galactose impairs aerobic glycolysis, as galactose enters glycolysis at a significantly lower rate than glucose via the Leloir pathway (Bustamante and Pedersen, 1977), a result confirmed by tracing galactose metabolism in T cells (Chang et al., 2013). Reducing GADPH engagement from glycolysis in this fashion permits moonlighting function by this abundantly expressed protein. It was shown that GAPDH binds to the 3′UTR of AU-rich containing cytokine mRNAs, preventing their efficient translation (Chang et al., 2013). Peng and colleagues argue against GAPDH posttranscriptional control of T cell function during aerobic glycolysis deficiency via LDHA deletion because modification of the 3′UTR of Ifng did not rescue defects in cytokine production in their system. However as the authors demonstrated, LDHA-deficient cells have defects in Ifng mRNA production, whereas cells forced to respire in galactose remain transcriptionally competent for Ifng as those cultured in glucose. Supplementation with the SCFA acetate rescued their epigenetic defect and cytokine production. These studies show that aerobic glycolysis regulates both transcriptional and translational functions in T cells.

While products generated from the microbiome can modulate the metabolism of immune cells and shift the balance between tolerance and inflammation, there are hints that immune driven signals central to gut homeostasis may also mediate their effects through metabolic modulation. One such example is the pleotropic anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. Most hematopoietic cells produce and sense IL-10 and its importance for maintaining tolerance with the intestinal microbiota is clearly evident from observations that IL-10 or IL-10R deficient mice develop spontaneous colitis (Kuhn et al., 1993; Spencer et al., 1998). IL-10R deficiency in macrophages is also sufficient to recapitulate onset of severe colitis in mice (Shouval et al., 2014; Zigmond et al., 2014). Further, mice with a myeloid cell-specific deficiency in STAT3, which is activated downstream of the IL-10R by JAK1, develop chronic enterocolitis as they age (Takeda et al., 1999). In experiments that shed light on the importance of aerobic glycolysis engagement in DC activation, it was found that treatment of DCs with recombinant IL-10 blocked increases in their glycolytic rate after LPS stimulation (Krawczyk et al., 2010). Cells subjected to IL-10R blockade further upregulated glycolysis after activation compared to controls. It is tempting to speculate that one of the ways IL-10 might be anti-inflammatory is through inhibition of metabolic reprogramming to aerobic glycolysis during innate immune cell activation (Figure 3). Coincidentally, STAT3 was found to localize to mitochondria and interact with ETC complexes, which helped maintain efficient OXPHOS in the heart (Wegrzyn et al., 2009). Whether traditional cell surface cytokine-receptor signaling could modulate levels of mitochondrial STAT3 was not explored. Of interest, CD8 T cells with a conditional deletion of the IL-10R fail to form memory T cells (Laidlaw et al., 2015), which depend on FAO driven OXPHOS for their generation after infection (Cui et al., 2015; Pearce et al., 2009; van der Windt et al., 2012).

The gut is one example of a tissue that presents distinct metabolic challenges for immune cells, which affect their steady state and protective versus inflammatory responses. Other examples, such as skin, provide the potential for commensal organisms to metabolically affect immune cell function, a topic reviewed elsewhere (Hand et al., 2016). The intestinal tract is constantly subjected to fluctuations in diet and sometimes the intake of invasive pathogens can also deprive metabolic substrates from immune cells. The bacterium Salmonella typhimurium produces a putative type II asparaginase that depletes available asparagine needed for metabolic reprogramming of activated T cells via c-Myc and mTOR (Torres et al., 2016). The use of asparaginase for acute lymphoblastic leukemia treatment highlights the potential for the depletion of extracellular arginine to significantly affect cellular function (DeBerardinis and Chandel, 2016). Lack of dietary vitamin B1 decreases the number of naïve B cells in Peyer’s patches due to their dependence on this TCA cycle cofactor, while leaving IgA+ plasma cells intact in the lamina propria (Kunisawa et al., 2015). Although ILC metabolism has only recently been explored (Monticelli et al., 2016; Wilhelm et al., 2016), it was found that in settings of vitamin A deficiency, type 2 ILCs sustain their function via increased acquisition and utilization of fatty acids for FAO (Wilhelm et al., 2016) (Figure 3). The internal balance between polyunsaturated fats and saturated fatty acids can also determine the pathogenicity of Th17 cells; cells that help maintain mucosal barrier immunity and contribute to pathogen clearance (Wang et al., 2015). Long chain fatty acids (LCFA) promote Th1 and Th17 cell polarization and mice fed with LCFA have exacerbated T cell-mediated autoimmune responses, whereas mice fed with SCFA are protected (Haghikia et al., 2015). If the internal lipidome of Th17 cells can alter their function from protective to inflammatory as well as their access to LCFA versus SCFA in the small intestine, it begs the question of how other tissue systems with a rich diversity of fat deposits and cells, such as the adipose tissue, modulate the metabolism and function of resident immune cells. Indeed, a recent study has found that the survival and function of resident memory T cells depends on exogenous lipid uptake and metabolism mediated by fatty acid binding proteins 4 and 5 (Pan et al., 2017).

ORGANISMAL METABOLISM AND IMMUNE CELL FUNCTION

Thus far, we have examined the affects of distinct niches in which immune cells come to inhabit that mold their metabolic and functional fates. The tumor microenvironment represents one instance of a pathophysiological situation that immune cells may encounter, whereas the gastrointestinal tract is an example of a physiological tissue system that immune cells come to occupy (Figure 4). During acute or chronic inflammation induced by infection, diet, cancer, or injury, a feed forward loop may exist where effector molecules, released from immune cells responding to these various localized insults to homeostasis, also modulate systemic metabolism and these changes to organismal metabolism then feed back onto the metabolism of immune cells, altering their subsequent function. Much has been done in the last decades in the regard to associations between diet and inflammation with pathological metabolic syndromes such as diabetes and insulin resistance or cardiovascular diseases (Font-Burgada et al., 2016). However, the relationship between changes in whole body metabolism and immunometabolism remains largely an uncharted area waiting to be explored (Man et al., 2017).

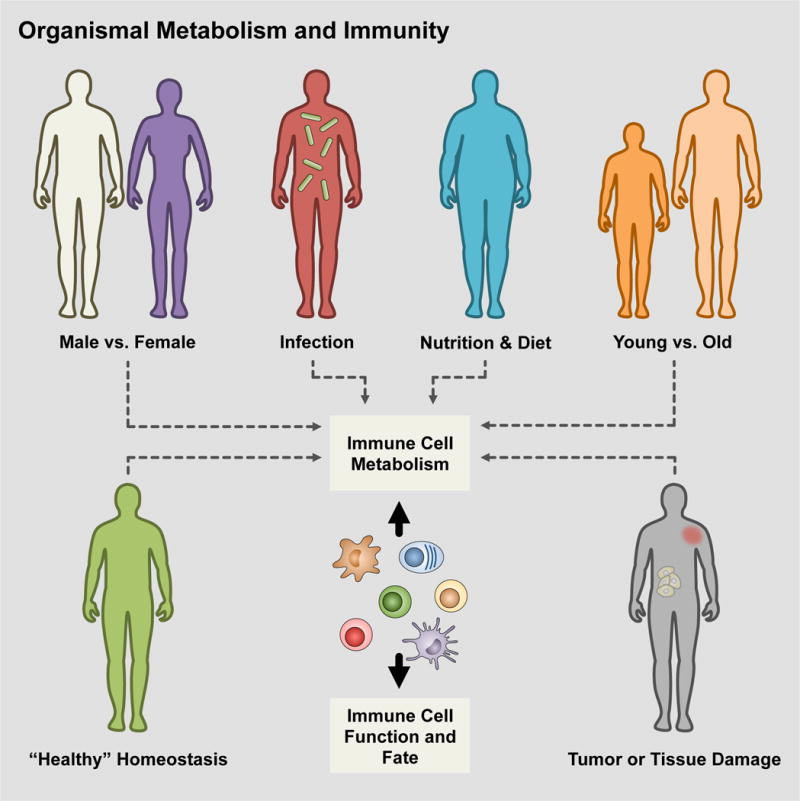

Figure 4. Tying organismal metabolism to cellular metabolism and immunity.

Throughout the course of life, organisms are exposed to a variety of factors that influence their systemic metabolism and the relationship between these and immune cell metabolism is only beginning to be explored. As research moves forward, it will be important to understand how these challenges integrate with immune response programs and whether our current paradigms and models regarding immunometabolism match up or must be modified accordingly under these circumstances.

Chronic low-grade inflammation is a well-established major risk factor for a plethora of diseases including heart disease, diabetes, metabolic syndromes, and cancer (Hotamisligil, 2017; Park et al., 2010), but our understanding of how inflammation contributes to the pathogenesis of these complex diseases is murky. Part of the complexity is due to the local, regional, and systemic actions of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α. These are generally considered to be produced in response to local tissue damage or infection, which can regulate not only the metabolic activities of neighboring cells, but also act on distal sensors that control host metabolism (Febbraio, 2014). For example, circulating IL-6 levels are elevated in patients with chronic inflammation, which can modulate fatty acid metabolism and cell survival in many tissues including skeletal muscle, hepatocytes, the central nervous system (CNS), and neuroendocrine system (Saltiel and Olefsky, 2017).

In obesity and consumption of a high fat diet (HFD), macrophages accumulate within adipose tissue recruited by dying enlarged adipocytes, and produce the inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α (Cinti et al., 2005; McLaughlin et al., 2017). Locally, IL-6 can induce lipolysis in neighboring adipocytes and impair lipoprotein lipase, decreasing adipocyte lipid storage. The rise in circulating IL-6 and free fatty acids (FFAs) has broad secondary effects on local and distal tissue microenvironments and can promote local insulin resistance, which can be reversed with therapeutic blockade of IL-6. IL-6 alone can also antagonize insulin receptor signaling and induce insulin resistance (McLaughlin et al., 2017). Interestingly, increased serum triglycerides and LDL is one of the most frequent reported adverse events in patients who receive Toclizumab, an IL-6 receptor blockade antibody, suggesting that IL-6 may play an important role in lipid homeostasis during inflammatory conditions (Schultz et al., 2010).

Increased circulating FFAs have consequences on immune cell function. Accumulation of FFAs in macrophages promotes ROS generation, which in turn augments activation of the NLRP3-ASC inflammasome (Guo et al., 2015). Inflammasome activation increases tissue inflammation through IL-1β and IL-18 secretion via cleavage activation by caspase-1 and pyroptosis (Rathinam and Fitzgerald, 2016). FFA-induced inflammasome activation promotes insulin resistance, mediated by the secretion of IL-1β. However, inflammasome activation may exhibit functional specificity for certain FFAs, as not all saturated fatty acids are capable of inflammasome activation. A HFD consisting of mostly monounsaturated fatty acids, while still promoting obesity in mice, does not induce inflammasome activation and the development of insulin resistance (Finucane et al., 2015). Tying into FFA metabolism, NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4) deficient mouse and human macrophages stimulated in vitro with ATP, nigericin, or silica have impaired caspase-1 activation and subsequent IL-1β and IL-18 maturation, although TNF-α production remains intact (Moon et al., 2016). Moon and colleagues found that inflammasome activation was also diminished in NOX4−/− mice after Streptococcus pneumoniae challenge. This defect was identified as an inability of NOX4 deficient cells to augment Cpt1a dependent FAO during inflammasome activation. Consistent with this observation, Cpt1a deficient macrophages were unable to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, but enforced expression of Cpt1a in NOX4 deficient macrophages rescued inflammasome activation and cytokine release. However, exactly how NOX4 regulates Cpt1a protein levels and FAO and whether extracellular FFAs may contribute to this process was left unresolved.

Why do inflammatory cytokines exert systemic changes to metabolism on other cells? Perhaps in the case of acute infections, inflammatory cytokines do so to create a temporary period of local and/or systemic insulin resistance, which could allow for redirection of glucose to immune cells, such as T cells, to fuel their rapid division and meet their bioenergetic demands. However when inflammation persists, like in cancer, obesity, or chronic infection, prolonged disruption of metabolic homeostasis could lead to immune cell dysfunction, dysregulated systemic metabolism, and ultimately cachexia (Porporato, 2016). Cachexia is a multi-organ syndrome of rapid weight loss and appetite and is one of the most obvious morbidities in cancer patients. The specific etiology of cachexia is debated and cancer-associated cachexia is not exclusive to tumor burden or therapies, suggesting that the state of cancer itself promotes progression of metabolic dysfunction. TNF-α was originally considered the major driver of cachexia as implied by its original name, “cachectin”. However, blockade of TNF-α is insufficient to prevent cachexia, and more recent studies point to the involvement of IL-6 in this process (Porporato, 2016). Chronic inflammation in the tumor microenvironment is a source of IL-6 production that leads to an increase in its systemic levels in cancer patients. IL-6 mediated liberation of fatty acids from systemic lipid stores, in concert with decreases in insulin availability or responsiveness, may instigate a catabolic state that becomes unhinged where lipolysis and also ketosis pillages energy stores within subcutaneous adipose tissue and skeletal muscle culminating in a wasting disorder (Flint et al., 2016; Odegaard et al., 2007). The extent to which immune cell metabolism is affected by systemic substrate availability in vivo, and how cachexia, as well as other situations, like consumption of ketogenic diets, influences nutrient depots and ultimately utilization by immune cells remains to be investigated.

Feeding behaviors can also affect host immune fitness (Figure 4). The gut-brain axis controls appetite, sensory of luminal contents, and digestion. The hypothalamus also regulates so called “sickness behaviors”, such as sickness-associated anorexia and reduced energy expenditure, but it is still not clear why sickness behaviors occur and more importantly what benefit they might provide to the host response to infection or inflammation. Wang and colleagues asked whether the fed or fasted state was more protective against infection with various pathogens (Wang et al., 2016a). Bypassing the anorexic response induced by infection with food or glucose supplementation increased lethality during Listeria monocytogenes or LPS challenge.

Glucose-mediated death was due in part to enhanced neuronal dysfunction, as the mice succumbed to epileptic seizures. The authors suggested that increased ROS disrupted neural function, however whether the enhanced morbidity was dependent on ROS and its cellular source was not identified. Giving mice 2-DG to impair glucose catabolism improved their survival. However, glucose supplementation was protective when mice were challenged with influenza or Poly(I:C). Viral infection promoted ER stress responses that were mitigated by glucose consumption. On the other hand, temporary ketosis was required for survival from LPS induced sepsis, suggesting that ketones are protective against hypothalamic inflammation and ROS-mediated neuronal damage. Ketogenic diets have been effective to reduce epileptic seizures and the potential benefits of ketogenic diets have been debated for other conditions such as cancer (Allen et al., 2014). However, pre-fasting or feeding the mice a ketogenic diet for 1–3 days prior to LPS stimulation made them more susceptible to its lethal effects, suggesting that in order to be protective, ketogenic metabolism should be temporally coordinated to the course of infection (Wang et al., 2016a). Interestingly, specific ketone bodies have been shown to minimize inflammation in other instances by blocking NLRP3 inflammasome activation in bone marrow-derived macrophages and human monocytes (Youm et al., 2015).

Some pathogens have evolved strategies to take advantage of modulating feeding behaviors to promote their own fitness. A recent report by Rao and colleagues suggests that Salmonella typhimurium inhibits infection-induced anorexia upon oral infection by antagonizing caspase-1 activity downstream of inflammasome activation to decrease IL-1β signaling to the hypothalamus via the vagus nerve (Rao et al., 2017). Disrupting this adaptation in Salmonella by genetic deletion of its ubiquitin ligase SlrP resulted in modulation of the gut-brain axis. Infection with SlrP deficient Salmonella augmented IL-1β maturation, resulting in changes to hypothalamic appetite regulation, whereby the mice decreased food consumption and exhibited greater weight loss that ultimately diminished host survival. Severing the gut-CNS connection surgically or force-feeding the mice reversed this anorexic response and increased lethality induced by SlrP-deficient Salmonella infection. The studies by Wang et al. and Rao et al. help give some mechanistic insight into the exciting interconnection between feeding behaviors and disease susceptibility versus tolerance, but also show that there is still much to learn about precisely how different pathogens and routes of infection affect this process. We have highlighted only a few examples where, going through the arc of life, many other organismal factors and changes may occur that influence immune cell metabolism, which directly impacts immune cell function and fate (Figure 4). Investigating how these perturbations affect not only our overall health will be challenging, but also interesting for further research.

OUTLOOK

Immunology for some time became a field that sought reductionist approaches to simplify a complex network of cells. Out of necessity, immunologists had to speak a common language or jargon that often excluded scientists in other disciplines. After many decades of hard work, great strides have been made in our understanding of the immune system and now immunologists are better equipped to cross over into other disciplines. It is this ‘take a step back and look’ approach that has led a number of laboratories to focus on metabolism and how this affects the immune system as well as its greater impact in tissue physiology.

It is obvious to most biologists that metabolism is integrated into every cellular process and fate decision. After all, everything must eat to survive. However, what is perhaps less appreciated is that the immune system is like a liquid organ unto itself. At their inception, immune cells are poised to respond to unknown stimuli, nutrients, pathogens and are akin to special agents with contingency plans, ready to respond to one disaster scenario after another, or may be relegated to pushing paperwork at the office maintaining the status quo. We have only highlighted some examples of the complexity of the situations and environments that immune cells face that provide various metabolic instructional cues throughout this review. This ability to rapidly change and adapt at any given second means that immune cells must intimately integrate their cellular metabolism in a way that most other organ and cell systems in the body do not have to, which we hope this review has shown and inspires research into many questions that remain to be explored. Coupling the unique benefits of studying immunometabolism is the added bonus of the enormous clinical relevance of these cells in human health and disease. First defining and then exploiting their unique metabolism may continue to yield new targets for therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Edward Pearce and members of the Pearce laboratories for their insight and critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (R01CA181125 and R01AI091965 to E.L.P.; R37AI066232, R01CA195720, R01CA196660, P50CA196530 Yale SPORE in Lung Cancer, PI, Herbst, R to S.M.K.; Ruth L. Kirschtein National Research Service Award 5T32HL007974 to R.T.S.), the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award to E.L.P.), the MRA Team Science Award (to S.M.K.), the Max Planck Society, and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE-1143954 to M.D.B.). We regret that we are unable to cite all relevant studies due to space limitations.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

E.L.P. is on the scientific advisory board of Immunomet. The authors declare no additional conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbott RK, Thayer M, Labuda J, Silva M, Philbrook P, Cain DW, Kojima H, Hatfield S, Sethumadhavan S, Ohta A, et al. Germinal Center Hypoxia Potentiates Immunoglobulin Class Switch Recombination. J Immunol. 2016;197:4014–4020. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams JL, Smothers J, Srinivasan R, Hoos A. Big opportunities for small molecules in immuno-oncology. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2015;14:603–622. doi: 10.1038/nrd4596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams WC, Chen YH, Kratchmarov R, Yen B, Nish SA, Lin WW, Rothman NJ, Luchsinger LL, Klein U, Busslinger M, et al. Anabolism-Associated Mitochondrial Stasis Driving Lymphocyte Differentiation over Self-Renewal. Cell Rep. 2016;17:3142–3152. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen BG, Bhatia SK, Anderson CM, Eichenberger-Gilmore JM, Sibenaller ZA, Mapuskar KA, Schoenfeld JD, Buatti JM, Spitz DR, Fath MA. Ketogenic diets as an adjuvant cancer therapy: History and potential mechanism. Redox Biol. 2014;2:963–970. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki K, Turner AP, Shaffer VO, Gangappa S, Keller SA, Bachmann MF, Larsen CP, Ahmed R. mTOR regulates memory CD8 T-cell differentiation. Nature. 2009;460:108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature08155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arpaia N, Campbell C, Fan X, Dikiy S, van der Veeken J, deRoos P, Liu H, Cross JR, Pfeffer K, Coffer PJ, et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature. 2013;504:451–455. doi: 10.1038/nature12726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balmer ML, Ma EH, Bantug GR, Grahlert J, Pfister S, Glatter T, Jauch A, Dimeloe S, Slack E, Dehio P, et al. Memory CD8(+) T Cells Require Increased Concentrations of Acetate Induced by Stress for Optimal Function. Immunity. 2016;44:1312–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengsch B, Johnson AL, Kurachi M, Odorizzi PM, Pauken KE, Attanasio J, Stelekati E, McLane LM, Paley MA, Delgoffe GM, et al. Bioenergetic Insufficiencies Due to Metabolic Alterations Regulated by the Inhibitory Receptor PD-1 Are an Early Driver of CD8(+) T Cell Exhaustion. Immunity. 2016;45:358–373. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berod L, Friedrich C, Nandan A, Freitag J, Hagemann S, Harmrolfs K, Sandouk A, Hesse C, Castro CN, Bahre H, et al. De novo fatty acid synthesis controls the fate between regulatory T and T helper 17 cells. Nat Med. 2014;20:1327–1333. doi: 10.1038/nm.3704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand A, Singer K, Koehl GE, Kolitzus M, Schoenhammer G, Thiel A, Matos C, Bruss C, Klobuch S, Peter K, et al. LDHA-Associated Lactic Acid Production Blunts Tumor Immunosurveillance by T and NK Cells. Cell Metab. 2016;24:657–671. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck MD, O’Sullivan D, Pearce EL. T cell metabolism drives immunity. J Exp Med. 2015;212:1345–1360. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck Michael D, O’Sullivan D, Geltink Klein, Ramon I, Curtis, Jonathan D, Chang C-H, Sanin David E, Qiu J, Kretz O, Braas D, van der Windt, Gerritje JW, et al. Mitochondrial Dynamics Controls T Cell Fate through Metabolic Programming. Cell. 2016;166:63–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante E, Pedersen PL. High aerobic glycolysis of rat hepatoma cells in culture: role of mitochondrial hexokinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:3735–3739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.9.3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caro-Maldonado A, Wang R, Nichols AG, Kuraoka M, Milasta S, Sun LD, Gavin AL, Abel ED, Kelsoe G, Green DR, et al. Metabolic Reprogramming Is Required for Antibody Production That Is Suppressed in Anergic but Exaggerated in Chronically BAFF-Exposed B Cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2014;192:3626–3636. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cham CM, Driessens G, O’Keefe JP, Gajewski TF. Glucose deprivation inhibits multiple key gene expression events and effector functions in CD8+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:2438–2450. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne DP, Hatle KM, Fortner KA, D’Alessandro A, Thornton TM, Yang R, Torralba D, Tomas-Cortazar J, Jun YW, Ahn KH, et al. Fine-Tuning of CD8(+) T Cell Mitochondrial Metabolism by the Respiratory Chain Repressor MCJ Dictates Protection to Influenza Virus. Immunity. 2016;44:1299–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CH, Curtis JD, Maggi LB, Jr, Faubert B, Villarino AV, O’Sullivan D, Huang SC, van der Windt GJ, Blagih J, Qiu J, et al. Posttranscriptional control of T cell effector function by aerobic glycolysis. Cell. 2013;153:1239–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CH, Qiu J, O’Sullivan D, Buck MD, Noguchi T, Curtis JD, Chen Q, Gindin M, Gubin MM, van der Windt GJ, et al. Metabolic Competition in the Tumor Microenvironment Is a Driver of Cancer Progression. Cell. 2015;162:1229–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SH, Raybuck AL, Stengel K, Wei M, Beck TC, Volanakis E, Thomas JW, Hiebert S, Haase VH, Boothby MR. Germinal centre hypoxia and regulation of antibody qualities by a hypoxia response system. Nature. 2016;537:234–238. doi: 10.1038/nature19334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinti S, Mitchell G, Barbatelli G, Murano I, Ceresi E, Faloia E, Wang S, Fortier M, Greenberg AS, Obin MS. Adipocyte death defines macrophage localization and function in adipose tissue of obese mice and humans. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:2347–2355. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500294-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clever D, Roychoudhuri R, Constantinides MG, Askenase MH, Sukumar M, Klebanoff CA, Eil RL, Hickman HD, Yu Z, Pan JH, et al. Oxygen Sensing by T Cells Establishes an Immunologically Tolerant Metastatic Niche. Cell. 2016;166:1117–1131. e1114. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogliati S, Frezza C, Soriano ME, Varanita T, Quintana-Cabrera R, Corrado M, Cipolat S, Costa V, Casarin A, Gomes LC, et al. Mitochondrial cristae shape determines respiratory chain supercomplexes assembly and respiratory efficiency. Cell. 2013;155:160–171. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colegio OR, Chu NQ, Szabo AL, Chu T, Rhebergen AM, Jairam V, Cyrus N, Brokowski CE, Eisenbarth SC, Phillips GM, et al. Functional polarization of tumour-associated macrophages by tumour-derived lactic acid. Nature. 2014;513:559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature13490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condamine T, Dominguez GA, Youn JI, Kossenkov AV, Mony S, Alicea-Torres K, Tcyganov E, Hashimoto A, Nefedova Y, Lin C, et al. Lectin-type oxidized LDL receptor-1 distinguishes population of human polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer patients. Science Immunology. 2016;1:aaf8943–aaf8943. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaf8943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubillos-Ruiz JR, Silberman PC, Rutkowski MR, Chopra S, Perales-Puchalt A, Song M, Zhang S, Bettigole SE, Gupta D, Holcomb K, et al. ER Stress Sensor XBP1 Controls Anti-tumor Immunity by Disrupting Dendritic Cell Homeostasis. Cell. 2015;161:1527–1538. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui G, Staron MM, Gray SM, Ho PC, Amezquita RA, Wu J, Kaech SM. IL-7-Induced Glycerol Transport and TAG Synthesis Promotes Memory CD8+ T Cell Longevity. Cell. 2015;161:750–761. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang EV, Barbi J, Yang HY, Jinasena D, Yu H, Zheng Y, Bordman Z, Fu J, Kim Y, Yen HR, et al. Control of T(H)17/T(reg) balance by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Cell. 2011;146:772–784. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa V, Galgani M, Porcellini A, Colamatteo A, Santopaolo M, Zuchegna C, Romano A, De Simone S, Procaccini C, La Rocca C, et al. Glycolysis controls the induction of human regulatory T cells by modulating the expression of FOXP3 exon 2 splicing variants. Nature Immunology. 2015;16:1174–1184. doi: 10.1038/ni.3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBerardinis RJ, Chandel NS. Fundamentals of cancer metabolism. Sci Adv. 2016;2:e1600200. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgoffe GM, Kole TP, Zheng Y, Zarek PE, Matthews KL, Xiao B, Worley PF, Kozma SC, Powell JD. The mTOR kinase differentially regulates effector and regulatory T cell lineage commitment. Immunity. 2009;30:832–844. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doedens AL, Phan AT, Stradner MH, Fujimoto JK, Nguyen JV, Yang E, Johnson RS, Goldrath AW. Hypoxia-inducible factors enhance the effector responses of CD8(+) T cells to persistent antigen. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:1173–1182. doi: 10.1038/ni.2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doughty CA, Bleiman BF, Wagner DJ, Dufort FJ, Mataraza JM, Roberts MF, Chiles TC. Antigen receptor-mediated changes in glucose metabolism in B lymphocytes: role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling in the glycolytic control of growth. Blood. 2006;107:4458–4465. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufort FJ, Bleiman BF, Gumina MR, Blair D, Wagner DJ, Roberts MF, Abu-Amer Y, Chiles TC. Cutting Edge: IL-4-Mediated Protection of Primary B Lymphocytes from Apoptosis via Stat6-Dependent Regulation of Glycolytic Metabolism. The Journal of Immunology. 2007;179:4953–4957. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.4953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufort FJ, Gumina MR, Ta NL, Tao Y, Heyse SA, Scott DA, Richardson AD, Seyfried TN, Chiles TC. Glucose-dependentde NovoLipogenesis in B Lymphocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2014;289:7011–7024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.551051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eales KL, Hollinshead KER, Tennant DA. Hypoxia and metabolic adaptation of cancer cells. Oncogenesis. 2016;5:e190. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2015.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Febbraio MA. Role of interleukins in obesity: implications for metabolic disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014;25:312–319. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay DK, Rosenzweig E, Sinclair LV, Feijoo-Carnero C, Hukelmann JL, Rolf J, Panteleyev AA, Okkenhaug K, Cantrell DA. PDK1 regulation of mTOR and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 integrate metabolism and migration of CD8+T cells. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2012;209:2441–2453. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finucane OM, Lyons CL, Murphy AM, Reynolds CM, Klinger R, Healy NP, Cooke AA, Coll RC, McAllan L, Nilaweera KN, et al. Monounsaturated fatty acid-enriched high-fat diets impede adipose NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated IL-1beta secretion and insulin resistance despite obesity. Diabetes. 2015;64:2116–2128. doi: 10.2337/db14-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint TR, Janowitz T, Connell CM, Roberts EW, Denton AE, Coll AP, Jodrell DI, Fearon DT. Tumor-Induced IL-6 Reprograms Host Metabolism to Suppress Anti-tumor Immunity. Cell Metab. 2016;24:672–684. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Font-Burgada J, Sun B, Karin M. Obesity and Cancer: The Oil that Feeds the Flame. Cell Metab. 2016;23:48–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]