Summary

Background

There are few effective treatments for advanced urothelial carcinoma after progression following platinum-based chemotherapy. We assessed the activity and safety of nivolumab in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who progressed after prior platinum-based therapy.

Methods

This phase 1/2 multicentre open-label study enrolled patients aged ≥18 years with urothelial carcinoma of the renal pelvis, ureter, bladder, or urethra unselected by programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1). Tumour PD-L1 membrane expression was assessed. Patients received nivolumab 3 mg/kg intravenously every 2 weeks until disease progression or study treatment discontinuation, whichever occurred later. The primary endpoint was objective response rate by investigator assessment. All patients who received at least one dose of any study medication were analysed. Here we report an interim analysis of this ongoing trial. CheckMate 032 is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01928394.

Findings

Between June 2014 and April 2015, 86 patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma were enrolled and 78 were treated with nivolumab monotherapy. At data cutoff (March 24, 2016), minimum follow-up was 9 months. A confirmed investigator-assessed objective response was achieved in 19 (24·4%) of 78 patients (95% CI 15·3–35·4). Grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events occurred in 17 (21·8%) of 78 patients, the most common being laboratory abnormalities: asymptomatic elevated lipase in four (5·1%) and asymptomatic elevated amylase three (3·8%) patients. Serious adverse events were reported in 36 (46·2%) of 78 patients. Two (2·6%) of 78 patients discontinued due to treatment-related adverse events (pneumonitis and thrombocytopenia) and subsequently died.

Interpretation

Nivolumab monotherapy was associated with significant and durable clinical responses and a manageable safety profile in previously treated patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. These data indicate a favourable benefit:risk profile for nivolumab and support further investigation of nivolumab monotherapy in advanced urothelial carcinoma.

Keywords: CheckMate 032, metastatic urothelial carcinoma, nivolumab, PD-L1, programmed death ligand-1

Introduction

Nearly three decades have elapsed since the first paradigm-shifting therapies were developed for the treatment of patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma. The combination regimen methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (MVAC) has never been surpassed in terms of response and survival.1 In 2000, gemcitabine plus cisplatin was recommended as a less toxic alternative, although 37% of patients could not tolerate treatment on the published schedule.2 Decades of research followed exploring cytotoxic frontline chemotherapies,3 but none were able to surpass the therapeutic plateau achieved with MVAC. Notably, approximately 25–50% of patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma are unable to receive cisplatin-based therapy.4 Nonetheless, platinum-based combination chemotherapy remains the front-line standard of care for patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma.4 In the second-line setting, many agents have been tested but have failed to be established as standard of care due to dismal response rates (10% or less). The most intensively studied, vinflunine plus best supportive care, did not significantly improve overall survival (OS; hazard ratio 0·9; 95% CI 0·7–1·1, intent-to-treat population) in a phase 3 trial when compared with best supportive care, although an increase in median OS of 2·6 months was observed with vinflunine in a subsequent analysis of the eligible population (hazard ratio 0·8; 95% CI 0·6–1·0; p=0·0227).5

Immune checkpoint therapy, consisting of blockade of immune inhibitory pathways, has recently led to considerable advances in the treatment of cancer. The potential for this approach in the treatment of urothelial carcinoma is suggested by the effectiveness of immunotherapy with bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG); administered intravesically, BCG induces an immune response against tumour cells and is indicated as adjuvant therapy after surgical resection in high-grade non-muscle–invasive urothelial carcinoma.6 The immune checkpoint inhibitor ipilimumab, which blocks the cytotoxic lymphocyte antigen-4 receptor, has also shown enhanced immune responses and tumour regression in early studies of patients with localised urothelial carcinoma.7,8

A promising target for immunotherapy is the programmed death-1 (PD-1) and programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) immune checkpoint. PD-1 is expressed on T cells and can inhibit T-cell responses on interaction with its ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2; high levels of PD-L1 expression have been found in bladder tumour cells.9,10 A clinical trial with atezolizumab, an antibody that blocks PD-L1, reported response rates of 15% in patients with metastatic or surgically unresectable urothelial carcinoma who were previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy,11 leading to US Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have disease progression during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy or disease progression within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment with platinum-containing chemotherapy.

Treatment with nivolumab, a fully human monoclonal IgG4 antibody that blocks PD-1, rather than blockade of a single ligand, has proven fruitful in multiple solid tumours. Nivolumab has shown improved OS in melanoma, non–small-cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and head and neck cancer, and studies have shown promising clinical activity in multiple additional malignancies including Hodgkin’s lymphoma and microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancer.12–18

Nivolumab has recently been investigated in an ongoing multicentre, open-label, phase 1/2 clinical study of several advanced or metastatic solid tumour types (CheckMate 032).19,20 Here, we report the efficacy and safety of nivolumab monotherapy in a cohort of patients from this study with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (unselected for PD-L1 expression) who were previously treated with platinum-based therapy. Outcomes in patients treated with nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab will be reported separately.

Methods

Study design and participants

CheckMate 032 is a multicentre, open-label, two-stage, multi-arm, phase 1/2 study. Patients with histologically or cytologically confirmed carcinoma of the renal pelvis, ureter, bladder, or urethra were enrolled at 16 sites in five countries (Finland, Germany, Spain, UK, and USA).

Eligible patients had locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma and were unselected based on tumour PD-L1 expression level. They had progressive disease after ≥1 prior platinum-based therapy for metastatic disease or locally advanced unresectable disease, or recurrence within 1 year of completing prior platinum-based neo-adjuvant or adjuvant therapy, or had previously refused standard treatment with chemotherapy for the treatment of metastatic (stage IV) or locally advanced unresectable disease. Patients were aged ≥18 years, with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1. They had measurable disease by CT or MRI (per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors [RECIST] v1.1).21 Baseline laboratory tests required to assess eligibility included white blood cell counts, neutrophils, platelets, haemoglobin, serum creatinine, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate amino transferase, total bilirubin, albumin, lipase, and amylase. Key exclusion criteria included active brain or leptomeningeal metastases; any serious or uncontrolled medical disorder; history of or active, known, or suspected autoimmune disease (vitiligo, type I diabetes mellitus, residual hypothyroidism due to autoimmune thyroiditis, and conditions not expected to recur in the absence of an external trigger were permitted); need for immunosuppressive doses of systemic corticosteroids (>10 mg/day prednisolone equivalents) for at least 2 weeks before study drug administration; and prior therapy with experimental antitumour vaccines or any modulator of T-cell function or checkpoint pathway. Median survival for patients with relapsed advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelium has been reported as approximately 4·6–6·9 months.5

The study was approved by the institutional review board/independent ethics committee for each centre and conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines defined by the International Conference on Harmonisation. All patients provided written informed consent to participate based on the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Procedures

Patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma were enrolled using an interactive voice response system to receive nivolumab 3 mg/kg intravenously every 2 weeks until progression or unacceptable toxicity, whichever occurred later. Patients in the nivolumab monotherapy arm could switch to nivolumab combined with ipilimumab (nivolumab 1 mg/kg + ipilimumab 3 mg/kg; or nivolumab 3 mg/kg + ipilimumab 1 mg/kg intravenously every 3 weeks for four cycles) after progression if they met prespecified criteria (see appendix p4). Treatment beyond RECIST (version 1.1)-defined progression was permitted if nivolumab was tolerated and clinical benefit was noted, based on investigator assessment (see appendix p4). No dose reductions or modifications were permitted. Criteria for dose delay (until resolution of the treatment-related adverse event to grade 1 or lower) have been described previously.19

Tumour assessments (CT and/or MRI) were performed at baseline (within 28 days before the first dose of study medication), every 6 weeks (±1 week) until week 24, and every 12 weeks (±1week) thereafter until disease progression (investigator-assessed per RECIST version 1.1). If study treatment was discontinued for reasons other than disease progression, tumour assessments were continued. Laboratory assessments were performed within 72 hours before dose through week 24, and every alternate dose thereafter. Safety assessments were performed continuously in all treated patients, and adverse events and laboratory values were graded according to the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0. As described previously,19 assessment of tumour PD-L1 protein expression was performed retrospectively by Dako PD-L1 immunohistochemical 28-8 pharmDx kit in pretreatment tumour biopsy specimens, fresh or archived within 3 months prior to treatment start. Multiple pretreatment specimens may have been tested for PD-L1 expression and used to define PD-L1 status. Tumour PD-L1 expression was categorised as positive when staining of tumour-cell membrane (at any intensity) was observed in ≥1% or ≥5% of tumour cells in a section that included ≥100 evaluable tumour cells in any sample (not necessarily the sample collected most proximal to study drug treatment). PD-L1 expression thresholds were chosen based on prior studies in other tumour types.13–15,17

Outcomes

The prespecified primary endpoint of the study was the proportion of patients with an investigator-assessed objective response (confirmed objective response rate [ORR] in the overall study population, defined as the number of patients with complete or partial response as best overall response per RECIST version 1.1 divided by the number of treated patients) based on tumour assessments at the time points described above. For a complete or partial response to be considered as a best overall response, the assessment needed to be confirmed by a second scan no less than 4 weeks after the criteria for response was first met. Tumour response was also reported in the response-evaluable population (those with best overall response in at least one target lesion identified at baseline and during at least one on-study timepoint with target lesion assessment).

Secondary endpoints were safety (incidence of treatment-related adverse events leading to drug discontinuation within the first 12 weeks of treatment), duration of response (time from partial or complete response until progressive disease or death due to any cause), progression-free survival (PFS; time from treatment assignment to the date of the first documented tumour progression or death due to any cause, whichever occurred first), and OS (time between the date of treatment assignment and the date of death due to any cause).

Exploratory endpoints included response by PD-L1 expression (ORR, OS, and PFS) and response (best overall response, duration of response, and time to response) by prognostic factors (including ECOG performance status, liver metastases, visceral involvement [defined as liver, lung, bone, or any non-lymph node], lymph nodes only, and haemoglobin <10 g/dL).

Non-conventional benefiters were also identified. These patients were defined as those who did not experience a best overall response of partial response or complete response prior to initial RECIST v1.1-defined progression, and met at least one of the following criteria: appearance of a new lesion followed by decrease from baseline of ≥10% in the sum of the target lesions; initial increase from nadir ≥20% in the sum of the target lesions followed by reduction from baseline of ≥30%; and initial increase from nadir ≥20% in the sum of the target lesions followed by at least two tumour assessments showing no further progression, defined as a 10% additional increase in the sum of target lesions and new lesions.

Statistical analyses

Patient enrolment followed a one-stage design, with a total sample size of 60–100 patients required to evaluate whether nivolumab resulted in an ORR of clinical interest; an ORR ≤10% was considered not to be of clinical value and an ORR ≥25% was considered of strong clinical interest. The sample size provided 90–97% power to reject the null hypothesis of 10% response rate if the true response rate was 25%, with a two-sided type 1 error rate of 5%. ORR was summarised by a binomial response rate and corresponding two-sided 95% exact CI using the method proposed by Atkinson and Brown.22 Duration of response was summarised for patients who achieved confirmed partial response or complete response using the Kaplan–Meier product-limit method, with median value and two-sided 95% CI. PFS and OS were summarised descriptively using Kaplan–Meier methodology, and median values estimated with two-sided 95% CIs using the Brookmeyer and Crowley method.23 To assess the potential effect of switching to combination therapy on OS, an ad hoc sensitivity analysis of OS was conducted excluding patients who switched to combination therapy. PFS and OS rates at 1 year were also estimated, with associated two-sided CIs calculated using the Greenwood formula. Response by PD-L1 expression was summarised with exact 95% CIs using the Clopper–Pearson method.24 Post-hoc analyses of response according to prognostic risk factors were also undertaken. Primary and secondary efficacy analyses included all patients who were treated with nivolumab monotherapy. Safety analyses included all patients who were enrolled at least 90 days prior to database lock.

We used SAS version 9.02 for all analyses. CheckMate 032 is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01928394.

Role of the funding source

The funder provided the study drug and worked with the investigators to design the study, and to collect, analyse, and interpret the data. All drafts of the report were prepared by the corresponding author with input from all co-authors and editorial assistance from professional medical writers, funded by the sponsor. Raw data were made accessible to the authors and professional medical writers. All authors made the decision to submit the report for publication.

Results

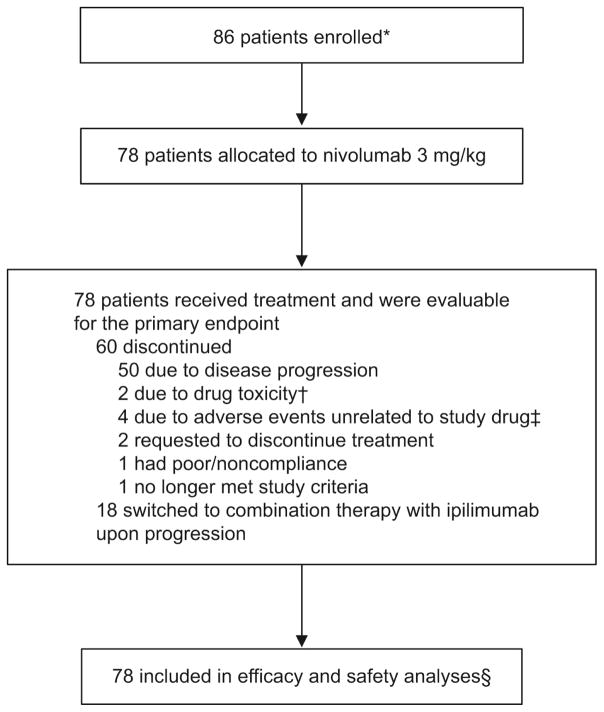

Between June 2014 and April 2015, 86 patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma were enrolled in the nivolumab monotherapy arm and 78 were treated with nivolumab monotherapy (3 mg/kg intravenously once every 2 weeks). At the time of analysis, 60 (76·9%) of 78 patients had discontinued therapy, primarily due to disease progression (n=50; 64·1%; figure 1), and of these, 53 (67·9%) were continuing to be followed. At data cutoff (March 24, 2016), minimum follow-up was 9 months, and patients had received a median of 8·5 doses (range 1–46) of nivolumab.

Figure 1. Patient enrolment and disposition.

*Eight patients not allocated to treatment due to withdrawal of consent (n=1), no longer meets study criteria (n=3), and not reported (n=4).

†Pneumonitis (n=1), thrombocytopenia (n=1).

‡Increased blood creatinine (n=1), hepatitis C infection (n=1), anaemia (n=1), and urosepsis (n=1).

§Not including adverse events in patients who received combination therapies after switching.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are summarised in table 1. Most patients (54 of 78; 69·2%) were men, and two-thirds (52 of 78; 66·7%) had received two or more prior treatment regimens. Three patients had not received prior platinum-containing chemotherapy in any setting. PD-L1 expression could be quantified in 67 patients. Virtually all submitted samples were obtained before the screening period, with 45 biopsies obtained from a primary tumour site and 22 from a metastatic site. At least one Bellmunt risk factor (ECOG performance status >0, liver metastases, or haemoglobin <10 g/dL) was present in 51 (65·4%) of 78 patients.

Table 1.

Baseline patient demographics and clinical characteristics

| Nivolumab (N=78) | |

|---|---|

| Median age, years (min, max) | 65·5 (31, 85) |

| Age category | |

| <65 years | 37 (47%) |

| ≥65 and <75 years | 31 (40%) |

| ≥75 years | 10 (13%) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 54 (69%) |

| Female | 24 (31%) |

| Race | |

| White | 72 (92%) |

| Black or African American | 4 (5%) |

| Asian | 1 (1%) |

| Other | 1 (1%) |

| Smoking status | |

| Current/former | 48 (62%) |

| Never smoker | 29 (37%) |

| Unknown | 1 (1%) |

| Number of prior regimens | |

| 1 | 26 (33%) |

| 2–3 | 42 (54%) |

| >3 | 10 (13%) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 42 (54%) |

| 1 | 36 (46%) |

| Baseline metastatic disease | |

| Visceral | 61 (78%) |

| Liver | 20 (26%) |

| Lymph node only | 13 (17%) |

| Baseline haemoglobin | |

| <10 g/dL | 11 (14%) |

| ≥10 g/dL | 67 (86%) |

| Number of Bellmunt risk factors | |

| 0 | 27 (35%) |

| 1 | 39 (50%) |

| 2 | 8 (10%) |

| 3 | 4 (5%) |

| Quantifiable tumour PD-L1 expression, % | 67 (86%) |

| PD-L1 <1% | 42 (54%) |

| PD-L1 ≥1% | 25 (32%) |

| PD-L1 <5% | 53 (68%) |

| PD-L1 ≥5% | 14 (18%) |

| Indeterminate, not evaluable, or missing | 11 (14%) |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise stated. Percentages according to race do not equal 100% due to rounding.

ECOG=Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

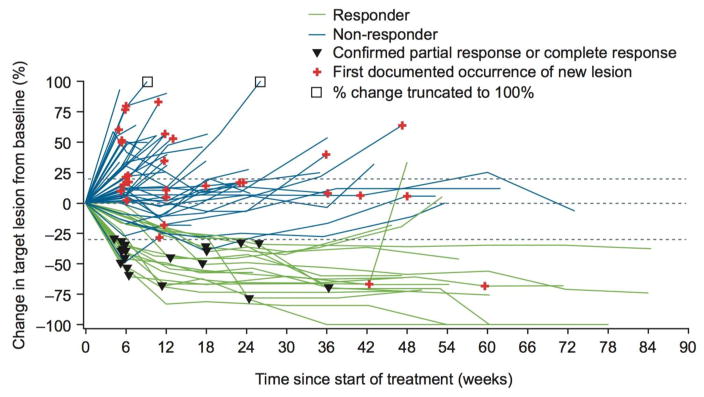

A confirmed investigator-assessed objective response was achieved in 19 (24·4%) of 78 treated patients (95% CI 15·3–35·4), with five patients (6·4%) achieving a complete response and 14 (17·9%) a partial response (table 2). Of 74 evaluable patients, 19 (25·7%) experienced a complete or partial response, resulting in an ORR of 25·7% (95% CI 16·2–37·2). Change in tumour burden over time is shown in figure 2 for evaluable patients who had a target lesion at baseline and at least one on-treatment tumour assessment. Of 31 patients who continued nivolumab monotherapy beyond progression, nine were considered non-conventional benefiters (appendix, p4).

Table 2.

Antitumor activity

| Nivolumab (N=78) | PD-L1 <1% | PD-L1 ≥1% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed objective response, % (95% CI) | 24·4 (15·3–35·4) | 26·2 (13·9–42·0) | 24·0 (9·4–45·1) |

| Best overall response, n (%) | |||

| Complete response | 5 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 4 (16%) |

| Partial response | 14 (18%) | 10 (24%) | 2 (8%) |

| Stable disease | 22 (28%) | 11 (26%) | 8 (32%) |

| Progressive disease | 30 (39%) | 18 (43%) | 8 (32%) |

| Unable to determine | 7 (9%) | 2 (5%) | 3 (12%) |

Figure 2. Change in tumour burden over time.

Responders were evaluable patients with complete or partial response as best overall response per RECIST version 1.1. Evaluable patients were those with a target lesion at baseline and at least one on-treatment tumour assessment.

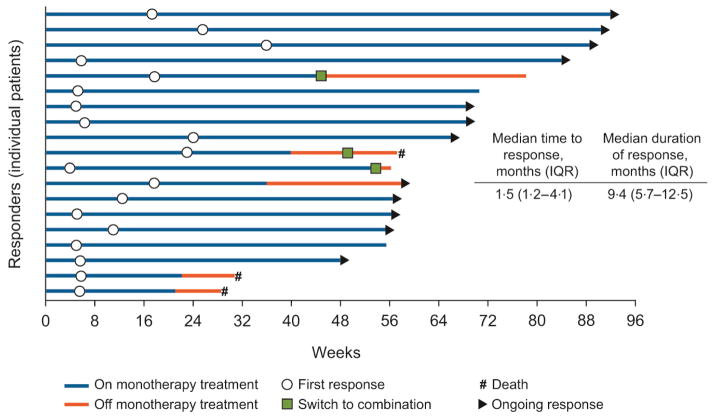

At the time of analysis, the median duration of response was 9·4 months (IQR 5·7–12·5) and the median time to response was 1·5 months (IQR 1·2–4·1). Of 19 responses, 12 had an ongoing response (11 who were still on nivolumab monotherapy), three patients switched to nivolumab plus ipilimumab combination therapy (one who subsequently died), two patients were continuing on nivolumab monotherapy despite no longer being in response, and two patients had died (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Time to and duration of response.

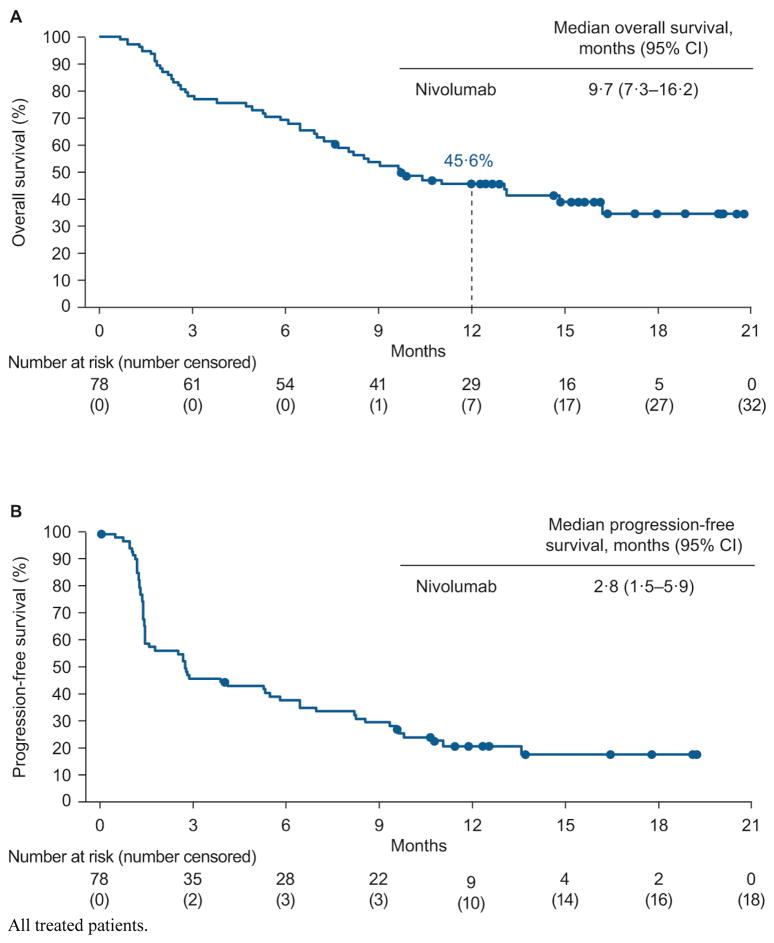

Median OS was 9·7 months (95% CI 7·3–16·2; figure 4A) and 46 of 78 (59·0%) patients had died at the time of data cutoff. One-year OS was 45·6% (95% CI 34·2–56·3). In an ad hoc sensitivity analysis of OS excluding patients who switched to combination therapy, the 1-year OS rate (95% CI) was 43·3% (30·6–55·3). Median PFS in the overall treated population was 2·8 months (95% CI 1·5–5·9; figure 4B) and 1-year PFS was 20·8% (95% CI 12·3–30·9) at the time of analysis. Sixty (76·9%) of 78 patients had had disease progression or died.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival (A) and progression-free survival (B).

An objective response was achieved in six (24·0%; 95% CI 9·4–45·1) of 25 patients with PD-L1 expression ≥1% (complete response in four patients [16·0%] and partial response in two [8·0%] patients), and in 11 (26·2%; 95% CI 13·9–42·0) of 42 patients with PD-L1 expression <1% (complete response in one patient [2·4%] and partial response in ten [23·8%] patients). Tumour reduction from baseline in target lesions is shown by PD-L1 expression in the appendix, p6–7.

Median OS was 16·2 months (95% CI 7·6–not estimable) in patients with PD-L1 expression ≥1% and 9·9 months (7·0–not estimable) in patients with PD-L1 expression <1% (appendix, p8). Median PFS was 5·5 months (95% CI 1·4–11·2) in patients with PD-L1 expression ≥1% and 2·8 months (1·4–6·5) in patients with PD-L1 expression <1% (appendix, p9). Similar results were seen in patients with ≥5% PD-L1 expression (appendix, p11).

In the post-hoc analysis of response by Bellmunt prognostic risk factors,25 an objective response was achieved in 16 (27·6%) of 58 patients without liver metastases and in three (15·0%) of 20 patients with liver metastases. Absence of visceral involvement and lymph node–only involvement were associated with a higher ORR than those with visceral involvement or no lymph node-only involvement, while patients with haemoglobin levels <10 g/dL had a lower ORR than those with levels ≥10 g/dL (table 3).

Table 3.

Objective response rate by prognostic risk factor

| Nivolumab ORR, % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 26·2 (13·9–42·0) |

| 1 | 22·2 (10·1–39·2) |

| Liver metastasis | |

| Yes | 15·0 (3·2–37·9) |

| No | 27·6 (16·7–40·9) |

| Visceral metastasis | |

| Yes | 21·2 (12·1–33·0) |

| No | 41·7 (15·2–72·3) |

| Lymph node only | |

| Yes | 36·4 (10·9–69·2) |

| No | 22·4 (13·1–34·2) |

| Haemoglobin <10 g/dL | |

| Yes | 18·2 (2·3–51·8) |

| No | 25·4 (15·5–37·5) |

ECOG=Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. ORR=objective response rate.

Grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse events occurred in 17 (21·8%) of 78 patients. The most commonly reported grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse events were elevated lipase (n=4 [5·1%]), elevated amylase (3 [3·8%]), fatigue (2 [2·6%]), maculopapular rash (2 [2·6%]), and dyspnoea (2 [2·6%]). Treatment-related adverse events reported in ≥10% of patients are listed in table 4. Treatment-related select adverse events (any grade) were skin (n=33 [42·3%]), gastrointestinal (8 [10·3%]), renal (7 [9·0%]), hepatic (4 [5·1%]), and pulmonary (2 [2·6%]). Additional post-hoc analyses were conducted of immune-mediated adverse events, regardless of causality, occurring within 100 days of last dose of nivolumab. Details are provided in the appendix, p10.

Table 4.

Treatment-related adverse events of any grade reported in ≥10% of patients and all grade 3–4 events

| Nivolumab (N=78) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Grade 1–2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | |

| Any event | 46 (59%) | 17 (22%) | 0 (0%) |

| Fatigue | 26 (33%) | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Pruritus | 23 (29%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Rash, maculopapular | 12 (15%) | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Lipase elevated | 7 (9%) | 4 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Nausea | 9 (12%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Arthralgia | 9 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Anaemia | 8 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Amylase increased | 4 (5%) | 3 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Dyspnoea | 4 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%)* |

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 3 (4%) | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Hyperglycaemia | 4 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 1 (1%) | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| White blood cell count decreased | 2 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Hyponatraemia | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Dermatitis acneiform | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Wheezing | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Acute kidney injury | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Back pain | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Colitis | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

Data presented as n (%); patients with adverse events after crossover from nivolumab 3 mg/kg to combination treatment are excluded. Some patients had more than one adverse event. Two patients had a grade 5 treatment-related event (one case of thrombocytopenia and one case of pneumonitis); both cases are described in greater detail within the appendix, p5.

This patient subsequently developed grade 5 pneumonitis and was counted in the grade 5 rather than the grade 4 total.

Eight (10·3%) of 78 patients experienced a serious adverse event considered to be treatment related. Serious adverse events (each reported as n=1) were colitis (grade 3–4), diarrhoea (grade 1–2), mouth ulceration (grade 1–2), nausea (grade 3–4), oral pain (grade 1–2), thrombocytopenia (grade 5), fatigue (grade 3–4), hyponatraemia (grade 3–4), acute kidney injury (grade 3–4), and pneumonitis (grade 5).

Two (2·6%) of 78 patients discontinued treatment because of treatment-related adverse events (grade 4 pneumonitis and grade 4 thrombocytopenia). Both events were fatal and are described in greater detail within the appendix, p5. Other than disease progression and study drug toxicity as causes of death in patients receiving nivolumab monotherapy, the following additional deaths were reported: three (3·8%) due to unknown causes, and one (1·3%) due to sepsis that was not considered related to study drug. Adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation but not considered related to study drug were increased blood creatinine (grade 2), hepatitis C infection (grade 3), anaemia (grade 3), and urosepsis (grade 3). At least one dose delay was experienced by 28 (35·9%) of 78 patients; 52 doses were delayed from a total of 982 doses received (5·3%), and 34 of 52 doses (65·4%) were delayed due to adverse events.

Discussion

Nivolumab monotherapy is associated with a substantial and durable tumour response, promising survival, and acceptable safety in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who were previously treated with platinum-based therapy. ORR is not dependent on tumour PD-L1 expression and is consistent across patient subgroups based on key prognostic factors.

Patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressive or relapsed disease after platinum-based combination chemotherapy have a poor prognosis, with a median survival of approximately 6 months.5 Multiple chemotherapies tested in the second-line setting have failed to demonstrate significant efficacy and have been associated with considerable toxicity.25–27 More recently, immune checkpoint therapies have demonstrated significant clinical responses across multiple tumour types, including urothelial carcinoma.11–18,28,29 Here, we report an ORR of 24·4% (19 of 78 patients), median OS of 9·7 months, and a 1-year OS rate of 45·6% with the anti–PD-1 antibody nivolumab in patients with refractory metastatic urothelial carcinoma unselected for PD-L1. These results compare favourably with outcomes reported in a recent phase 2 clinical trial in urothelial carcinoma with the anti–PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab.11 ORR in our study appeared consistent across different prognostic risk factor subgroups (limited by small sample size), and the ad hoc sensitivity analysis of OS excluding patients who switched to combination therapy found no adverse impact on the 1-year survival rate.

Nivolumab was also well tolerated in this population; the adverse event profile compares favourably with previously tested chemotherapies and no new safety signals were observed when compared with nivolumab studies across a wide range of tumour types.12–15,17 In addition, in this cohort of patients who tend to have multiple comorbidities and impaired renal function, nivolumab therapy was tolerated over multiple doses, suggesting a manageable tolerability profile in the longer term. Two patients discontinued treatment (due to grade 4 pneumonitis and grade 4 thrombocytopenia). Both events were subsequently fatal and are described in the appendix, p5.

PD-L1 expression on tumour cells, as defined by the Dako immunohistochemical assay, did not correlate with objective responses; patients whose tumours were defined as having ≥1% of tumour cells expressing PD-L1 had an ORR similar to that in patients whose tumours had <1% of tumour cells expressing PD-L1. Patients whose tumours had ≥1% of tumour cells expressing PD-L1 had a median OS of 16·2 months, while those whose tumours had <1% of tumour cells expressing PD-L1 had a median OS of 9·9 months. Longer follow-up is required to clarify whether this translates into differences in long-term OS. Inter-tumour heterogeneity, both between primary and metastatic lesions and between different metastatic lesions, could have contributed to a false-negative PD-L1 result, although this is mitigated by the fact that any positive sample (not necessarily the sample collected most proximal to study drug treatment) would assign a patient as having positive PD-L1 expression. It will be important to determine whether the current data are reproducible in a larger cohort of patients, and further insights will be provided by an ongoing phase 2 study (CheckMate 275; ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT02387996). Given recent data suggesting the prognostic value of PD-L1 immune cell (but not PD-L1 tumour cell) expression as a biomarker of response to atezolizumab in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma,11 further investigation of tumour response with nivolumab according to immune cell PD-L1 expression is warranted.

Limitations of the study include the lack of a standard “current practice” comparator due to the lack of effective treatments in this setting, the small sample size (resulting in low statistical power for subgroup analysis), and the relatively short follow-up period, precluding further insights into the impact of nivolumab on long-term survival. In addition, data on the efficacy and safety of treatment beyond progression, as well as protein expression scoring, were not available but are currently being analysed and will be reported at a later date.

In summary, nivolumab monotherapy led to substantial response rates and durable clinical responses in previously treated patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Clinically meaningful antitumour activity was observed regardless of tumour PD-L1 expression. The safety profile of nivolumab monotherapy was generally manageable in these heavily pretreated patients and consistent with previous reports in other tumour types, suggesting a favourable benefit:risk profile for nivolumab in the treatment of metastatic urothelial carcinoma. These findings will be explored further in the ongoing CheckMate 275 study; initial data suggest that this immune checkpoint therapy has activity in a patient population with limited treatment options.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed using the search terms “metastatic urothelial carcinoma”, “relapsed urothelial carcinoma”, “clinical trials”, “immune response”, “immune checkpoint blockade”, and “immunotherapy”. The search included articles published between December 1994 and May 2014.

The search revealed poor outcomes for patients with recurrent or relapsed urothelial carcinoma, with few treatment options to improve survival. A handful of papers reported early studies investigating immunotherapy in advanced urothelial carcinoma, including BCG therapy. The immune system is an acknowledged target for treatment in urothelial carcinoma; immunotherapy with BCG is standard therapy for superficial urothelial carcinoma, reducing the risk of local recurrence by approximately 60% and leading to 5-year survival rates of approximately 90% in patients with unifocal disease. In addition, CD8 tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) are predictive of survival in muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma; patients with advanced urothelial cancer and higher numbers of CD8 TILs within the tumour (>8) appear to have better disease-free and overall survival than those with similar-staged urothelial carcinoma and fewer intra-tumoural CD8 TILs. Together with the recent promising anti–PD-L1 data reported in advanced urothelial carcinoma, these observations provide the rationale for further investigation of immune checkpoint blockade with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab for recurrent metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

Added value of this study

These are the largest efficacy and safety data sets for an anti–PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor in second-line (and beyond) urothelial carcinoma, a setting in which there are currently limited treatment options. The response rate, duration of responses, and overall survival observed are clinically meaningful and may signify greater clinical activity than other available options.

Implications of all the available evidence

Patients with recurrent metastatic urothelial carcinoma currently have poor clinical prospects due to the lack of effective treatments. A growing body of evidence suggests that immune checkpoint inhibition can offer effective treatment for patients with urothelial carcinoma, as in other tumour types. The results presented here support further development of PD-1 checkpoint inhibition in larger trials of this disease.

Acknowledgments

Funding Bristol-Myers Squibb.

We thank the patients and their families, as well as the participating study teams, for making this study possible; the staff of Dako North America for collaborative development of the automated immunohistochemical assay for PD-L1 assessment; and Ono Pharmaceutical Company Limited. Medical writing and editorial assistance was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb and provided by Rachel Mason, Tom Rees, and Lawrence Hargett of PAREXEL International.

Footnotes

Contributors

Conception and design: P Sharma, MKC.

Collection and assembly of data: P Sharma, MKC, PB, JK, P Spiliopoulou, E Calvo, RNP, PAO, PdB, MM, DTL, DJ, E Chan, JER.

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors.

All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Drafting of the manuscript or critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: All authors.

Declaration of interests

P Sharma reports receiving fees for advisory board participation for Jounce and Kite, fees for consultancy from Jounce, Kite, Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS), AstraZeneca, and Amgen, and stock/stock options with Jounce and Kite.

MKC reports receiving grants from BMS, consultancy fees from AstraZeneca and Moderna, and payment for lectures from Clinical Care Options.

PB reports honoraria from BMS during the conduct of the study, honoraria from Pfizer, MSD, and Orion Pharma, and research funding from Novartis.

JK declares no competing interests.

P Spiliopoulou declares no competing interests.

E Calvo declares no competing interests.

RNP reports receiving a travel grant from BMS for an investigator meeting during the conduct of the study.

PAO reports receiving a grant from BMS and consultancy fees from BMS, Amgen, Celldex, Alexion, and Cytomx.

FdB reports receiving consultancy fees from Tiziana Life Sciences, BMS, MSD, Servier, Eli Lilly, Merck Serono, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novartis, and speaker fees from BMS, Eli Lilly, Roche, and ACCMED.

MM reports receiving consultancy fees from Etubics and Boehringer Ingelheim, and speaker fees from Genentech, Novartis, Sanofi, Regeneron, Lexicon, Ipsen, Onyx, Bayer, Taiho, Merrimack, and Celgene.

DTL declares no competing interests.

DJ reports being an employee of BMS.

E Chan reports receiving a grant from BMS for the conduct of the trial and consultancy fees for advisory board participation from EMD Serono, Taiho, Bayer, Advaxis, Amgen, Lilly, and Castle Biosciences.

CH reports being an employee of and holding stock options with BMS.

C-SL reports being an employee of and holding stock options with BMS.

MT reports being an employee of and holding stock options with BMS.

AA reports being an employee of BMS.

JER reports receiving a grant from BMS for the conduct of the study, consultancy fees from Roche/Genentech, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Agensys, Sanofi US Services, Oncogenex, Onyx, Dendreon, BMS, and Boehringer Ingelheim, grants from Novartis and Roche/Genetech, and holding stock/stock options with Illumina and Merck.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Logothetis CJ, Dexeus FH, Finn L, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing MVAC and CISCA chemotherapy for patients with metastatic urothelial tumors. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1050–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.6.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von der Maase H, Hansen SW, Roberts JT, et al. Gemcitabine and cisplatin versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in advanced or metastatic bladder cancer: results of a large, randomized, multinational, multicenter, phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3068–77. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.17.3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellmunt J, von der Maase H, Mead GM, et al. Randomized phase III study comparing paclitaxel/cisplatin/gemcitabine and gemcitabine/cisplatin in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer without prior systemic therapy: EORTC Intergroup Study 30987. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1107–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.6979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dash A, Galsky MD, Vickers AJ, et al. Impact of renal impairment on eligibility for adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Cancer. 2006;107:506–13. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellmunt J, Fougeray R, Rosenberg JE, et al. Long-term survival results of a randomized phase III trial of vinflunine plus best supportive care versus best supportive care alone in advanced urothelial carcinoma patients after failure of platinum-based chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1466–72. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babjuk M, Burger M, Zigeuner R, et al. EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: update 2013. Eur Urol. 2013;64:639–53. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liakou CI, Kamat A, Tang DN, et al. CTLA-4 blockade increases IFNγ-producing CD4+ICOShi cells to shift the ratio of effector to regulatory T cells in cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14987–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806075105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carthon BC, Wolchok JD, Yuan J, et al. Preoperative CTLA-4 blockade: tolerability and immune monitoring in the setting of a presurgical clinical trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2861–71. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faraj SF, Munari E, Guner G, et al. Assessment of tumoral PD-L1 expression and intratumoral CD8+ T cells in urothelial carcinoma. Urology. 2015;85:703–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inman BA, Sebo TJ, Frigola X, et al. PD-L1 (B7-H1) expression by urothelial carcinoma of the bladder and BCG-induced granulomata: associations with localized stage progression. Cancer. 2007;109:1499–505. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberg JE, Hoffman-Censits J, Powles T, et al. Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1909–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00561-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I, et al. PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:311–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1627–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:123–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1803–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Overman MJ, Kopetz S, McDermott RS, et al. Nivolumab ± ipilimumab in treatment (tx) of patients (pts) with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) with and without high microsatellite instability (MSI-H): CheckMate-142 interim results. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(15 suppl) Abstract 3501. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillison ML, Blumenschein G, Jr, Fayette J, et al. Nivolumab (nivo) vs investigator’s choice (IC) for recurrent or metastatic (R/M) head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC): CheckMate-141. Presented at: American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting; April 16–20, 2016; New Orleans, LA, USA. (Abstract CT099) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antonia SJ, López-Martin JA, Bendell J, et al. Nivolumab alone and nivolumab plus ipilimumab in recurrent small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 032): a multicentre, open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:883–95. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le DT, Bendell JC, Calvo E, et al. Safety and activity of nivolumab monotherapy in advanced and metastatic (A/M) gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer (GC/GEC): Results from the CheckMate-032 study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(4 suppl) Abstract 6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1. 1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atkinson EN, Brown BW. Confidence limits for probability of response in multistage phase II clinical trials. Biometrics. 1985;41:741–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brookmeyer R, Crowley J. A confidence interval for the median survival time. Biometrics. 1982;38:29–41. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clopper CJ, Pearson ES. The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomial. Biometrika. 1934;26:404–13. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choueiri TK, Ross RW, Jacobus S, et al. Double-blind, randomized trial of docetaxel plus vandetanib versus docetaxel plus placebo in platinum-pretreated metastatic urothelial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:507–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.7002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bambury RM, Benjamin DJ, Chaim JL, et al. The safety and efficacy of single-agent pemetrexed in platinum-resistant advanced urothelial carcinoma: a large single-institution experience. Oncologist. 2015;20:508–15. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hainsworth JD, Meluch AA, Litchy S, et al. Paclitaxel, carboplatin, and gemcitabine in the treatment of patients with advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelium. Cancer. 2005;103:2298–303. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma P, Allison JP. Immune checkpoint targeting in cancer therapy: toward combination strategies with curative potential. Cell. 2015;161:205–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma P, Allison JP. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science. 2015;348:56–61. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.