Abstract

Purpose

Survivors of childhood cancer may experience financial burden as a result of health care costs, particularly because these patients often require long-term medical care. We sought to evaluate the prevalence of financial burden and identify associations between a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs (≥ 10% of annual income) and issues related to financial burden (jeopardizing care or changing lifestyle) among survivors of childhood cancer and a sibling comparison group.

Methods

Between May 2011 and April 2012, we surveyed an age-stratified, random sample of survivors of childhood cancer and a sibling comparison group who were enrolled in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Participants reported their household income, out-of-pocket medical costs, and issues related to financial burden (questions were adapted from national surveys on financial burden). Logistic regression identified associations between participant characteristics, a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs, and financial burden, adjusting for potential confounders.

Results

Among 580 survivors of childhood cancer and 173 siblings, survivors of childhood cancer were more likely to have out-of-pocket medical costs ≥ 10% of annual income (10.0% v 2.9%; P < .001). Characteristics of the survivors of childhood cancer that were associated with a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket costs included hospitalization in the past year (odds ratio [OR], 2.3; 95% CI, 1.1 to 4.9) and household income < $50,000 (OR, 5.5; 95% CI, 2.4 to 12.8). Among survivors of childhood cancer, a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs was significantly associated with problems paying medical bills (OR, 8.9; 95% CI, 4.4 to 18.0); deferring care for a medical problem (OR, 3.0; 95% CI, 1.6 to 5.9); skipping a test, treatment, or follow-up (OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.1 to 4.0); and thoughts of filing for bankruptcy (OR, 6.6; 95% CI, 3.0 to 14.3).

Conclusion

Survivors of childhood cancer are more likely to report spending a higher percentage of their income on out-of-pocket medical costs, which may influence their health-seeking behavior and potentially affect health outcomes. Our findings highlight the need to address financial burden in this population with long-term health care needs.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, cost sharing in the United States health care system has brought renewed attention to the issue of high out-of-pocket medical expenditures.1 Most health insurance plans do not cover all health care–related expenses, and cost sharing in the form of copayments, deductibles, and coinsurance may add substantially to the out-of-pocket costs incurred by patients. Although the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was created to improve access to affordable health care, including provisions to promote care for patients with preexisting medical conditions, high-deductible health plans may still leave patients underinsured.2,3 Underinsurance pertains to people who incur significant out-of-pocket medical expenses, generally > 10% of their family’s yearly income.4-9 Underinsured patients may be at a particularly high risk of experiencing financial burden, especially when faced with a serious illness, such as cancer.

The rising cost of cancer care and growing out-of-pocket medical expenses for adult patients with cancer have led to an increased focus on the financial burden experienced by these individuals.4,5,10 Research has demonstrated that the financial burden experienced by patients with cancer may negatively impact their treatment outcomes, including quality of life, symptom burden, and survival.11-13 Patients who experience financial burden may not properly adhere to prescribed therapies in an effort to defray costs14-16 and, thus, jeopardize their health care.17-19 Whereas these studies among adults with cancer provide compelling evidence with regard to the adverse effects of financial burden in this population, efforts to understand the financial burden among survivors of childhood cancer are lacking.

Despite advances in treatment and survival for children with cancer, many survivors of childhood cancer develop chronic health conditions, which results in a need for long-term medical care and places them at elevated risk for premature mortality20-23; however, survivors of childhood cancer frequently experience challenges obtaining necessary follow-up health care. Previous research using data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) demonstrated that many survivors reported restrictive and costly health insurance plans.24 Research suggests that uninsured survivors received less risk-based, survivor-focused care than those with health insurance.25 A qualitative study that involved CCSS participants demonstrated that uninsured survivors expressed considerable worry about the financial burden imposed by high health care costs.26 Thus, survivors of childhood cancer often encounter obstacles obtaining adequate insurance coverage, thereby putting them at risk for high out-of-pocket expenditures and, ultimately, financial burden.

In the present analysis, we sought to evaluate financial burden as a result of medical costs among survivors of childhood cancer and a sibling comparison group, and identify the relationship between high out-of-pocket medical costs (≥ 10% of annual household income) and adverse consequences of financial burden. In a previous study, we found that survivors report higher out-of-pocket expenses compared with siblings, particularly uninsured survivors.26a Although prior work has used high out-of-pocket costs as a surrogate for financial burden, few studies have examined the relationship between out-of-pocket costs and the adverse consequences of financial burden, such as jeopardizing medical care or changing lifestyle to cope with the burden, particularly among survivors of childhood cancer. Moreover, factors associated with the vulnerability of survivors to high out-of-pocket costs have not been fully examined. By identifying risk factors for high out-of-pocket medical costs and studying the consequences of these costs, we hope to aid in the development of interventions that will address the financial burden experienced by survivors of cancer.

METHODS

Study Design

Between May 2011 and April 2012, we performed a cross-sectional study of a randomly selected, age-stratified sample of survivors and a sibling comparison group who were enrolled in the CCSS. The institutional review boards of St Jude Children’s Research Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital and Partners Healthcare approved the study.

Study Population

The CCSS is a multi-institutional cohort study with longitudinal follow-up to describe and compare health outcomes of survivors of childhood cancer with those of siblings. Eligible survivors included those who were diagnosed with cancer before 21 years of age, received their initial treatment between 1970 and 1986, and survived ≥ 5 years from diagnosis. The CCSS includes survivors of leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Wilms tumor, tumors of the CNS, neuroblastoma, soft-tissue sarcoma, and bone tumor. The original CCSS cohort had 14,357 survivors and 4,023 randomly selected nearest-age siblings.27,28 Participants for the current analysis were identified from the original cohort’s 25 participating centers in the United States.

Data Collection

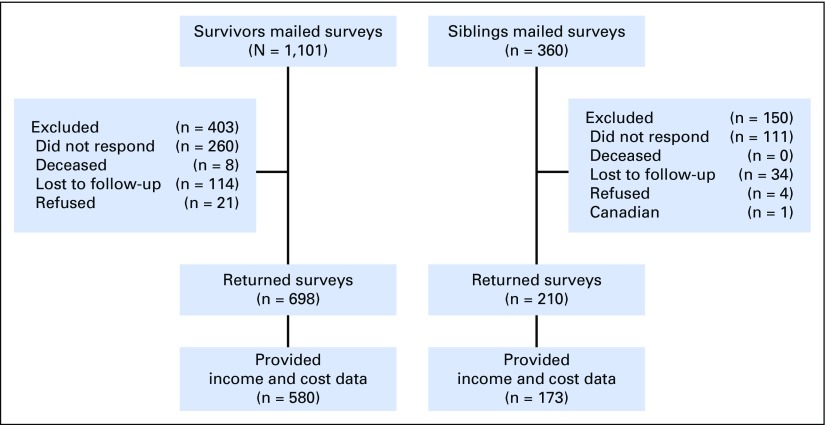

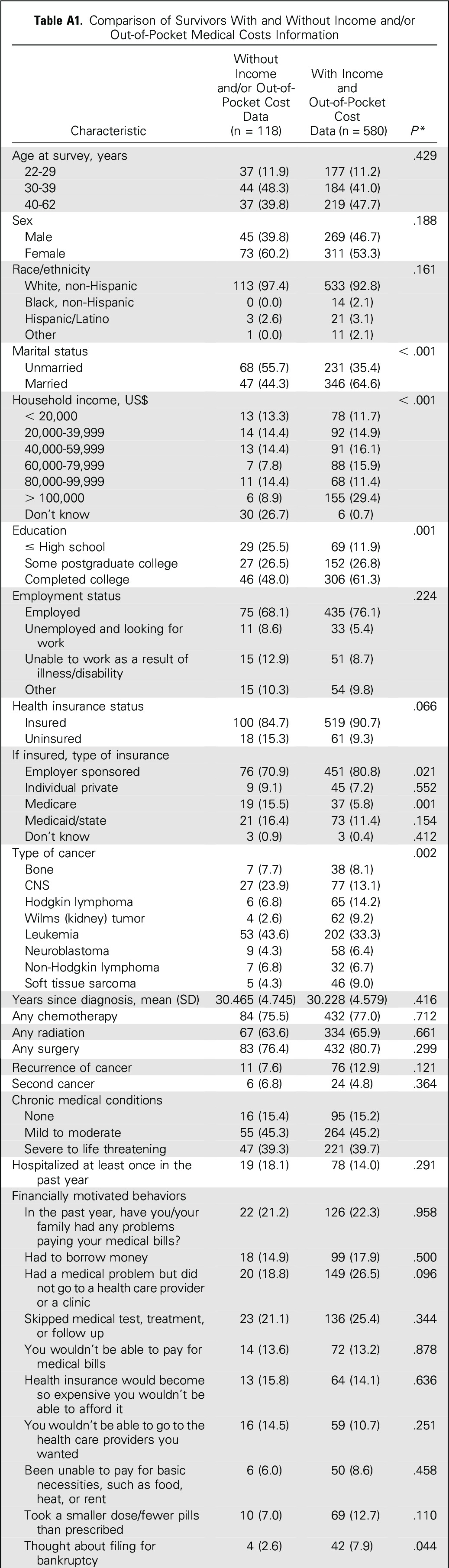

For the current study, we randomly selected 1,101 survivors from three age strata (current age younger than 30 years, 30 to 39 years, ≥ 40 years of age). Participants completed surveys either by mail or online. The sample (Fig 1) included 698 completed survivor surveys (63.4% response rate) and 210 sibling surveys (58.3% response rate). For the current study, we had information about income and out-of-pocket medical costs for 580 survivors and 173 siblings. Compared with those who did not provide their income and/or out-of-pocket medical costs, survivors who did report this information were more likely to be married, with more education, and have higher household incomes (Appendix Table A1, online only).

Fig 1.

Flow diagram.

Survey Measures

We developed surveys by adapting national surveys on insurance and financial burden, such as the National Health Interview Survey, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, and Commonwealth Fund Health Insurance Survey, and with an initial qualitative study.26,29-33 On the basis of participants’ responses to the first survey question, “Do you currently have health insurance that covers doctor and hospital care?” we asked them to complete either an insured or an uninsured version of the survey.34 Surveys assessed participants’ current marital status, employment status, household income, and insurance characteristics. We obtained data about sociodemographic, health care use, and cancer and treatment-related factors from CCSS baseline and follow-up surveys. We used the most recent follow-up survey to collect information regarding the severity of chronic health conditions (eg, heart failure, cognitive impairment, coronary artery disease, renal failure) classified as none, mild, moderate, severe, or life-threatening or disabling using the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 3), as previously published.20

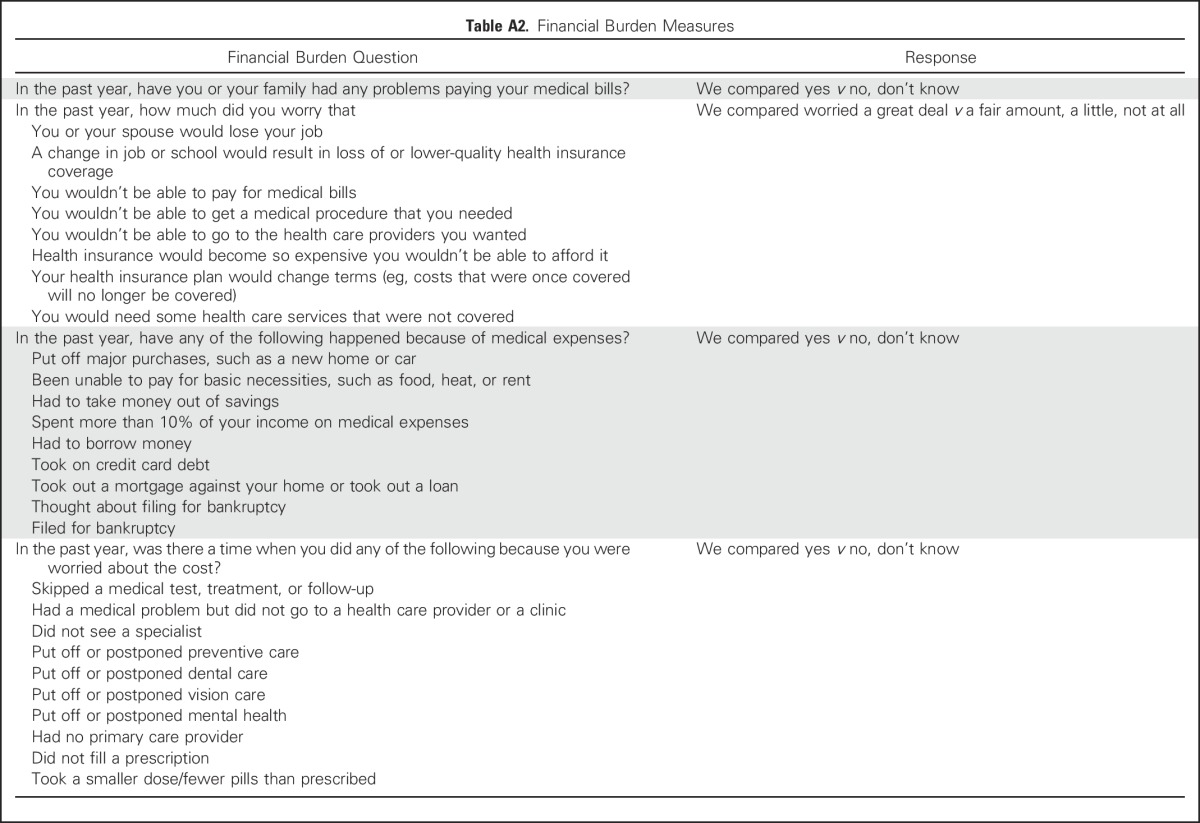

Issues Related to Financial Burden

We asked participants to answer “yes,” “no,” or “don’t know” to issues related to financial burden listed in the following questions (Appendix Table A2, online only): “In the past year, have you/your family had any problems paying your medical bills?”; “In the past year, have any of the following happened because of medical expenses?”; and “In the past year, was there a time when you did any of the following because you were worried about the cost?” We also asked participants, “In the past year, how much did you worry that?” with the following responses: “a great deal”; “a fair amount”; “a little”; or “not at all.”

Out-of-Pocket Medical Costs

We collected information about participants’ out-of-pocket medical costs and household income over the past year, then took the ratio of these variables to determine the percentage of household income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs. To assess out-of-pocket medical costs, we asked participants, “During the past year, about how much did you/your family spend out-of-pocket for your medical care? Include out-of-pocket expenses for prescription drugs, copayments, and deductibles, but do not include health insurance premiums or any costs paid by your health insurance.” We defined higher out-of-pocket medical costs to be ≥ 10% of household income, which was consistent with previous studies.4-9

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to describe the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics for survivors and siblings. We also compared survivors with a higher and lower percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs, but not for siblings, given the small number of siblings (n = 5) with higher out-of-pocket medical costs. To identify characteristics associated with higher out-of-pocket medical costs, we conducted multivariable logistic regression analysis, simultaneously evaluating those characteristics associated with spending ≥ 10% of their household income on out-of-pocket medical costs during the past year in univariate analyses.

To examine associations between a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs and issues related to financial burden, we used logistic regression models, adjusting for potential confounders (eg, marital status, presence of insurance, employment, and household income). We fit models with each indicator of financial burden as the outcome and used out-of-pocket medical costs ≥ 10% of household income as the key risk factor. All reported P values are two-sided and considered significant at an α-level of .05. All analyses incorporated weighting to account for the stratified sampling design so that results were representative of the age distribution in the CCSS cohort.35

RESULTS

Participants

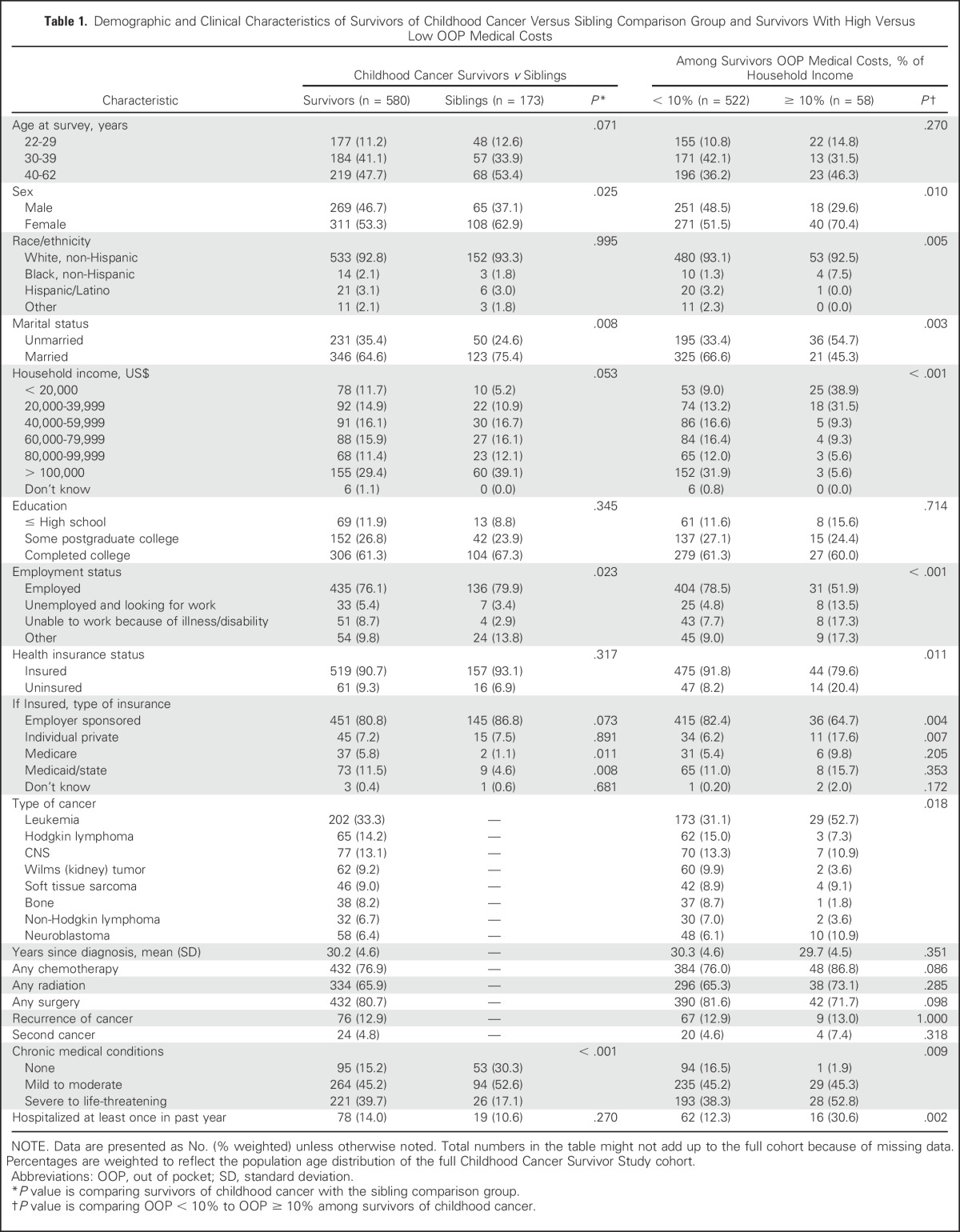

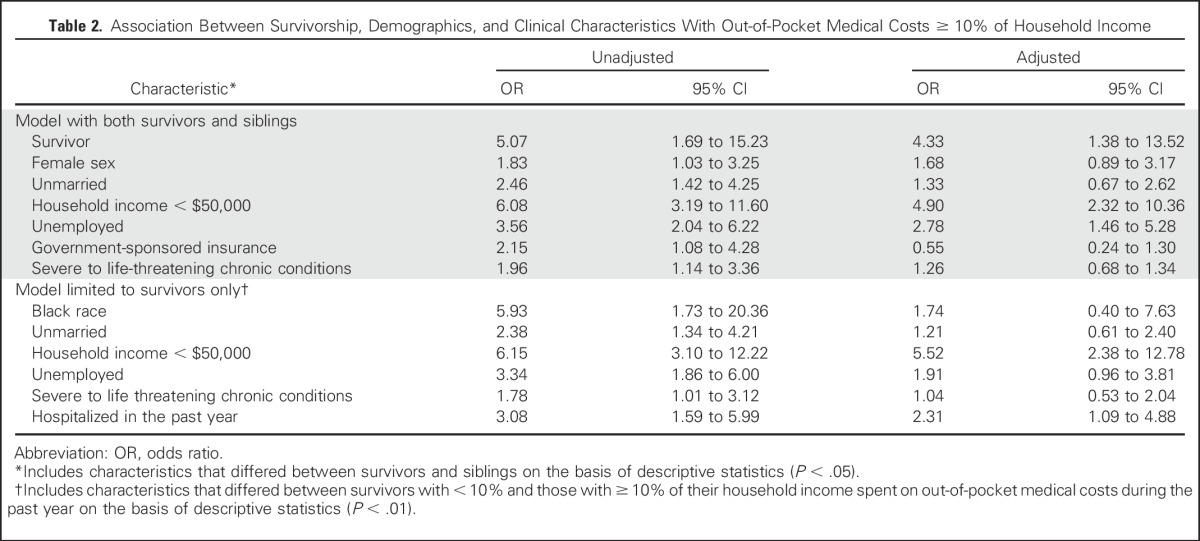

Survivors in our sample were more likely to be male (46.7% v 37.1%; P = .025), unmarried (35.4% v 24.6%; P = .008), and have severe to life-threatening chronic medical conditions (39.7% v 17.1%; P < .001) compared with siblings (Table 1). Survivors were more likely to have Medicare (5.8% v 1.1%; P = .011) and Medicaid/state insurance (11.5% v 4.6%; P = .008). Among survivors, mean time since cancer diagnosis was 30.2 years. Ten percent (58 of 580) of survivors had higher out-of-pocket medical costs, defined as spending ≥ 10% of their household income on out-of-pocket medical costs during the past year, which was significantly greater than the proportion of siblings with higher out-of-pocket medical costs (2.9% [5 of 173 siblings]; P < .001). In both unadjusted and adjusted models, survivors had significantly greater odds of experiencing a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs compared with siblings (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Survivors of Childhood Cancer Versus Sibling Comparison Group and Survivors With High Versus Low OOP Medical Costs

Table 2.

Association Between Survivorship, Demographics, and Clinical Characteristics With Out-of-Pocket Medical Costs ≥ 10% of Household Income

Characteristics Associated With a Higher Percentage of Income Spent on Out-of-Pocket Medical Costs

Survivors with a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs were more likely to be female (70.4% v 51.5%; P = .01), unmarried (54.7% v 33.4%; P = .003), and have private insurance (17.6% v 6.2%; P = .007) compared with those with lower out-of-pocket medical costs (Table 1). Survivors with a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs were more likely to have severe to life-threatening chronic medical conditions (52.8% v 38.3%; P = .009). In addition, those with a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs were less likely to be employed (51.9% v 78.5%; P < .001) and to have health insurance (79.6% v 91.8%; P = .011). We also found differences between those with higher and lower percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs regarding race/ethnicity (P = .005), household income (P < .001), and type of cancer (P = .018). Of note, we found no difference between the higher and lower out-of-pocket medical cost groups regarding the receipt of prior chemotherapy, radiation, or surgery.

To identify survivor characteristics associated with a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs, we conducted a multivariable analysis adjusting for characteristics that differed between those with higher and lower percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs during the past year (Table 2). We found that household income < $50,000 (odds ratio [OR], 5.5; 95% CI, 2.4 to 12.8) and being hospitalized at least once in the past year (OR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.1 to 4.9) were independently associated with a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs.

Financial Burden

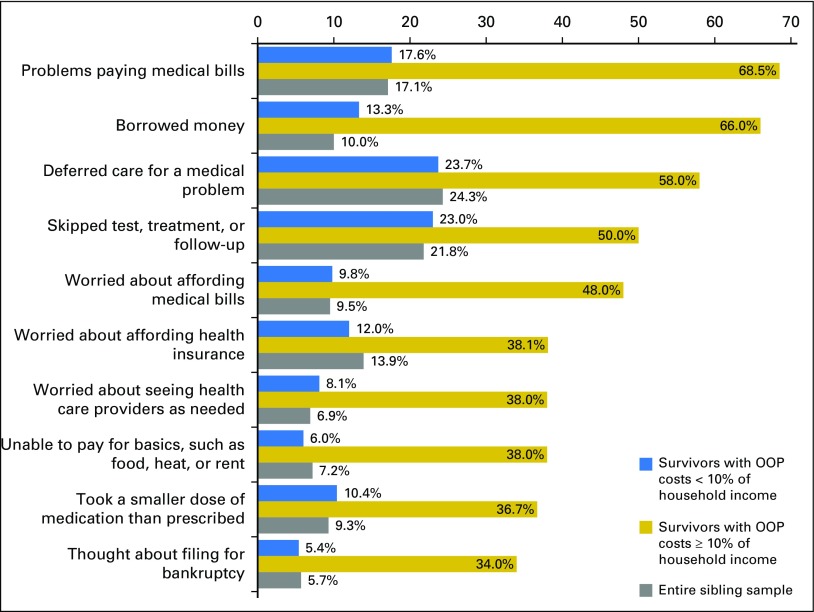

Figure 2 shows the prevalence of survivors’ and siblings’ self-reported financial burden. Survivors with a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs were more likely to report problems paying medical bills (68.5% v 17.6%; P < .001) compared with those with lower percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs. In addition, survivors with higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs were more likely to report deferring care (58.0% v 23.7%; P < .001); skipping a test, treatment, or follow-up (50.0% v 23.0%; P < .001); worrying about affording health insurance (38.1% v 12.0%; P < .001); taking a smaller dose of medication than prescribed (36.7% v 10.4%; P < .001); and thoughts of filing for bankruptcy (34.0% v 5.4%; P < .001).

Fig 2.

Financial burden among survivors of childhood cancer and siblings. OOP, out of pocket.

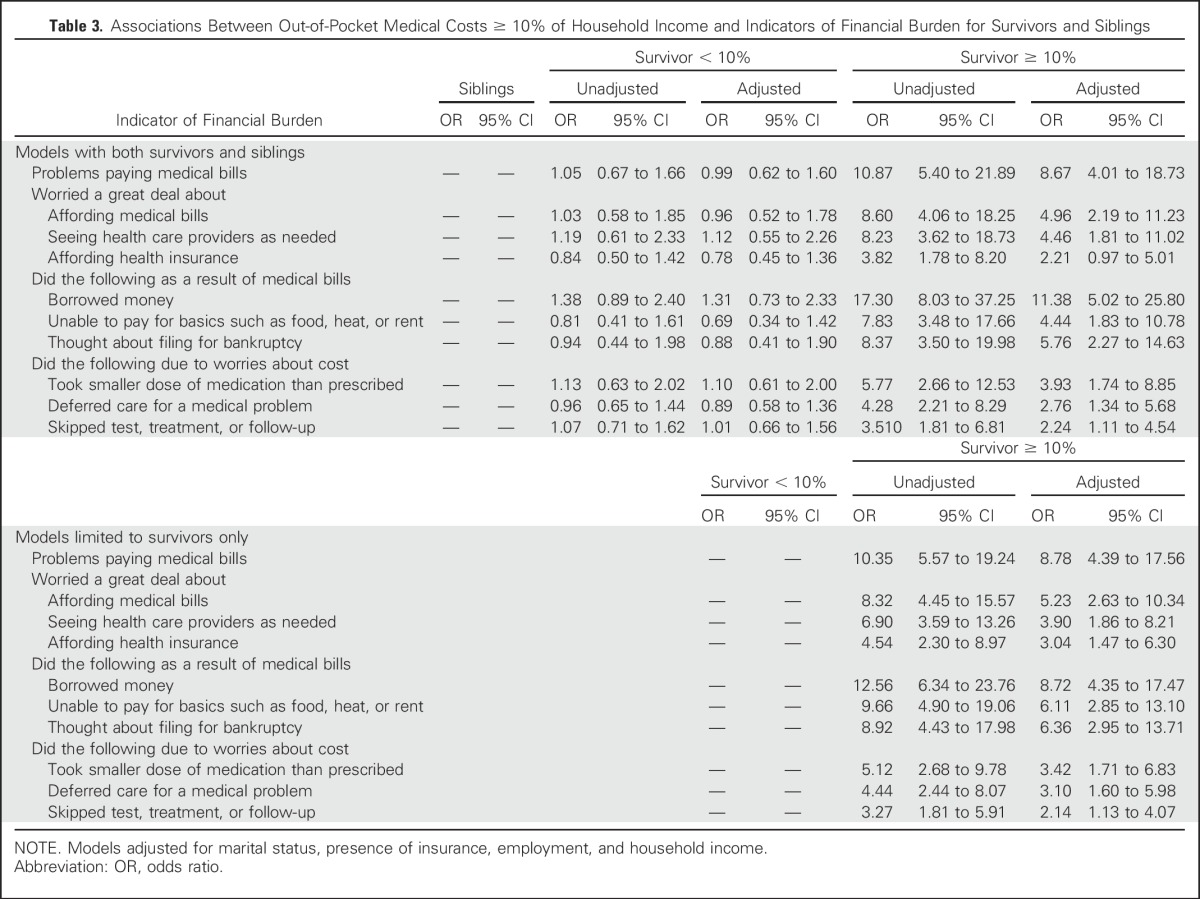

In both unadjusted and adjusted regression models, we found that survivors with out-of-pocket medical costs ≥ 10% of their annual household income were significantly more likely to report issues with financial burden compared with both siblings and survivors with lower out-of-pocket medical costs (Table 3). Because only five siblings spent ≥ 10% of their household income on out-of-pocket medical costs during the past year, we were unable to group siblings by high and low percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs. In adjusted models, survivors with a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs were more than eight times as likely to report problems paying medical bills compared with siblings (OR, 8.7; 95% CI, 4.0 to 18.7) and the group of survivors with lower out-of-pocket medical costs (OR, 8.8; 95% CI, 4.4 to 17.6). We also found significant associations between a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs and other self-reported indicators of financial burden, which included worrying about seeing health care providers as needed, thoughts of filing for bankruptcy, deferring care, and taking a smaller dose of medication than prescribed.

Table 3.

Associations Between Out-of-Pocket Medical Costs ≥ 10% of Household Income and Indicators of Financial Burden for Survivors and Siblings

DISCUSSION

In a national cohort of adult survivors of childhood cancer, we identified a relatively high prevalence of financial burden and demonstrated that survivors with a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs carry a significantly disproportionate financial burden compared with both a sibling comparison group and those with lower percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket costs. Of note, we found that survivors of cancer with higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket costs were more likely to report worries about seeing health care providers as needed, thoughts of filing for bankruptcy, and actions that may jeopardize their health, such as deferring care and not adhering to prescribed treatment. Importantly, survivors in our study, on average, were > 30 years from their cancer diagnosis and yet many still struggle with high out-of-pocket medical costs and resulting financial burden. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that survivors’ out-of-pocket medical costs put them at risk for experiencing adverse effects related to financial burden, which underscores the need to address high out-of-pocket medical expenditures in this population.

Of importance, our findings demonstrate that survivors have a greater risk for spending a higher percentage of their income on out-of-pocket medical expenses compared with a sibling control group. In addition, we identified characteristics of survivors who were more likely to spend ≥ 10% of their income on out-of-pocket medical expenses. Specifically, those with a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket costs were more likely to be unemployed, hospitalized in the past year, have more severe chronic medical conditions, and have lower incomes. These are vulnerable populations at particularly high risk for experiencing financial burden related to high medical costs who may ultimately suffer worse health outcomes by foregoing medical care.19,36-38 Thus, we have identified patient characteristics that can be used to proactively target these individuals with programs to address their financial concerns.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report associations between a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs and financial burden in adult survivors of childhood cancer. The behaviors adopted by survivors in our study in response to financial burden may have detrimental impacts on their survivorship care, quality of life, and even survival.11-19 A more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between high out-of-pocket medical expenses and adverse effects of financial burden on survivors of cancer could be instrumental in identifying those who are at risk for spending a higher percentage of their income on out-of-pocket medical costs to address their financial burden and improve health outcomes; informing policy change to help meet the unique needs of survivors of cancer; and understanding how both higher out-of-pocket costs and financial burden influence patients’ approaches to their medical care and decision-making. Therefore, our study identifies the unique and most commonly endorsed issues related to financial burden in survivors of cancer with a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs, and underscores the need to better understand and address high out-of-pocket costs in this population when striving to improve the quality of their care.

Our study marks the first step in understanding the prevalence, risk, and magnitude of financial burden in adult survivors of childhood cancer, and our findings have important policy implications. Survivors of childhood cancer represent a population with preexisting health conditions who are at particularly high risk for financial burden, which can negatively influence health outcomes, especially as cost sharing increases.13,16,36,37 Future research is needed to determine the extent to which survivors may experience greater financial burden as insurance plans are restructured and barriers to affordable health care persist. Efforts to ensure the systematic assessment of survivors’ financial concerns may become increasingly important, and health systems should encourage early and ongoing communication between clinicians and patients about the financial consequences of their care. Future efforts to address the financial burden of survivors of cancer should investigate the efficacy of incorporating financial discussions within survivorship clinics and/or care plans and focus on developing programs that involve financial services, patient navigators, and/or social work.

Several limitations of our study warrant discussion. First, we collected data from a cohort with limited racial and ethnic diversity; thus, our findings may not generalize to more diverse populations. Second, this is a cross-sectional study, and, therefore, we cannot confirm the directionality of the associations we found. Moreover, we asked participants to self-report their out-of-pocket medical costs, and these estimates may be limited by their ability to accurately recall out-of-pocket expenses. Of note, we followed the standard self-report practice of national surveys, including the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey and National Health Interview Survey, in asking participants to recall their income and out-of-pocket expenses.30,32,39 Third, we may have underestimated the strength of the relationship between a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical expenses and issues related to financial burden, as the survivors who reported their income and out-of-pocket costs had higher incomes and more education than did those for whom we lack this information. Fourth, we lack longitudinal data regarding changes in financial burden and out-of-pocket medical costs, and studies suggest that financial burden may vary throughout the survivorship course.19,38 In addition, we conducted the survey before the launch of the ACA health insurance exchanges, and, therefore, future investigators should study how the ACA influenced both high out-of-pocket medical costs and financial burden among survivors of cancer. Although the ACA seeks to protect those with preexisting conditions, prior work suggests that survivors of childhood cancer lack understanding of the ACA and have concerns about potential cost increases.35,40 We hope that our findings help to serve as a comparison for future efforts to understand the impact of current policy decisions on the financial burden experienced by survivors of cancer.

In summary, we identified that financial burden is common among adult survivors of childhood cancer and demonstrated associations between financial burden and a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs. Of note, a substantial minority of survivors in our cohort spent ≥ 10% of their household income on out-of-pocket medical expenses. Importantly, we found that survivors with a higher percentage of income spent on out-of-pocket medical costs were more likely to have lower incomes and to be hospitalized in the past year. In addition, we demonstrated that those with higher out-of-pocket medical costs were more likely to report financial burden and were at risk for behaviors that were potentially detrimental to their health outcomes. These findings underscore the long-term risks of high out-of-pocket medical expenses and potential economic threats to survivors’ quality of life after a diagnosis of childhood cancer. Future research that focuses on addressing the adverse consequences of the financial burden experienced by survivors of cancer is warranted and should account for the impact that out-of-pocket medical costs can have on this vulnerable population with long-term health care needs.

Appendix

Table A1.

Comparison of Survivors With and Without Income and/or Out-of-Pocket Medical Costs Information

Table A2.

Financial Burden Measures

Footnotes

Supported by the Livestrong Foundation, National Cancer Institute Grant No. CA55727 (to G.T.A.), and by a grant to St Jude Children’s Research Hospital from the Cancer Center Support Grants (CA21765).

Presented at the 2015 American Society of Clinical Oncology Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium, Boston, MA, October 9-10, 2015.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Ryan D. Nipp, Anne C. Kirchhoff, Douglas Fair, Julia Rabin, Karen Kuhlthau, Giselle K. Perez, Leslie L. Robison, Gregory T. Armstrong, Paul C. Nathan, Kevin C. Oeffinger, Wendy M. Leisenring, Elyse R. Park

Collection and assembly of data: Ryan D. Nipp, Anne C. Kirchhoff, Julia Rabin, Kelly A. Hyland, Leslie L. Robison, Gregory T. Armstrong, Wendy M. Leisenring, Elyse R. Park

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Financial Burden in Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Ryan D. Nipp

No relationship to disclose

Anne C. Kirchhoff

Stock or Other Ownership: Medtronic (I)

Douglas Fair

No relationship to disclose

Julia Rabin

No relationship to disclose

Kelly A. Hyland

No relationship to disclose

Karen Kuhlthau

Stock or Other Ownership: Alnylam (I), Eli Lilly (I), Laboratory Corporation of America (I), Merck (I), Novo Nordisk (I), Pfizer (I), Johnson & Johnson

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche

Giselle K. Perez

No relationship to disclose

Leslie L. Robison

No relationship to disclose

Gregory T. Armstrong

No relationship to disclose

Paul C. Nathan

No relationship to disclose

Kevin C. Oeffinger

No relationship to disclose

Wendy M. Leisenring

No relationship to disclose

Elyse R. Park

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Ward E, Halpern M, Schrag N, et al. : Association of insurance with cancer care utilization and outcomes. CA Cancer J Clin 58:9-31, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wharam JF, Ross-Degnan D, Rosenthal MB: The ACA and high-deductible insurance--strategies for sharpening a blunt instrument. N Engl J Med 369:1481-1484, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health and Human Services :Compilation of patient protection and Affordable Care Act, May 2010. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ppacacon.pdf

- 4.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. : The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: A pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist 18:381-390, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schoen C, Doty MM, Robertson RH, et al. : Affordable Care Act reforms could reduce the number of underinsured US adults by 70 percent. Health Aff (Millwood) 30:1762-1771, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Short PF, Banthin JS: New estimates of the underinsured younger than 65 years. JAMA 274:1302-1306, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banthin JS, Cunningham P, Bernard DM: Financial burden of health care, 2001-2004. Health Aff (Millwood) 27:188-195, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gabel JR, McDevitt R, Lore R, et al. : Trends in underinsurance and the affordability of employer coverage, 2004-2007. Health Aff (Millwood) 28:w595-w606, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banthin JS, Bernard DM: Changes in financial burdens for health care: national estimates for the population younger than 65 years, 1996 to 2003. JAMA 296:2712-2719, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ubel PA, Abernethy AP, Zafar SY: Full disclosure—Out-of-pocket costs as side effects. N Engl J Med 369:1484-1486, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kale HP, Carroll NV: Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among US cancer survivors. Cancer 122:283-289, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steel JL, Geller DA, Kim KH, et al. : Web-based collaborative care intervention to manage cancer-related symptoms in the palliative care setting. Cancer 122:1270-1282, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. : Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 34:980-986, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neugut AI, Subar M, Wilde ET, et al. : Association between prescription co-payment amount and compliance with adjuvant hormonal therapy in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 29:2534-2542, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Streeter SB, Schwartzberg L, Husain N, et al. : Patient and plan characteristics affecting abandonment of oral oncolytic prescriptions. J Oncol Pract 7:46s-51s, 2011. (suppl 3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zullig LL, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. : Financial distress, use of cost-coping strategies, and adherence to prescription medication among patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract 9:60s-63s, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nipp R, Zullig L, Peppercorn J, et al. : Coping with cancer treatment-related financial burden. J Clin Oncol 32, 2014. (suppl 31; abstr 161) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hershman DL, Shao T, Kushi LH, et al. : Early discontinuation and non-adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 126:529-537, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, et al. : Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer 119:3710-3717, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. : Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med 355:1572-1582, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, et al. : Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. JAMA 309:2371-2381, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armstrong GT, Kawashima T, Leisenring W, et al. : Aging and risk of severe, disabling, life-threatening, and fatal events in the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol 32:1218-1227, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armstrong GT, Chen Y, Yasui Y, et al. : Reduction in late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med 374:833-842, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park ER, Li FP, Liu Y, et al. : Health insurance coverage in survivors of childhood cancer: The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 23:9187-9197, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nathan PC, Greenberg ML, Ness KK, et al. : Medical care in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol 26:4401-4409, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park ER, Kirchhoff AC, Zallen JP, et al. : Childhood Cancer Survivor Study participants’ perceptions and knowledge of health insurance coverage: Implications for the Affordable Care Act. J Cancer Surviv 6:251-259, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26a.Park ER, Kirchhoff AC, Perez-Lougee G, et al. : Childhood Cancer Survivor Study participants’ health insurance coverage experiences. Poster presentation at the annual meeting of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. San Antonio, TX, April 22-25, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robison LL, Armstrong GT, Boice JD, et al. : The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: A National Cancer Institute-supported resource for outcome and intervention research. J Clin Oncol 27:2308-2318, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leisenring WM, Mertens AC, Armstrong GT, et al. : Pediatric cancer survivorship research: Experience of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 27:2319-2327, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reference deleted.

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention : National health interview survey. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm

- 31.Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative : National survey of children with special health care needs. http://www.childhealthdata.org/learn/NS-CSHCN

- 32.US Department of Health and Human Services : Medical expenditure panel survey. http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/

- 33.The Commonwealth Fund : 1997 Commonwealth Fund/Kaiser Family Foundation national survey of health insurance. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/interactives-and-data/surveys/biennial-health-insurance-surveys/1997/kaiser-commonwealth-1997-national-survey-of-health-insurance

- 34.St Jude Children’s Research Hospital : The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: Questionnaires. https://ccss.stjude.org/tools-and-documents/questionnaires.html

- 35.Park ER, Kirchhoff AC, Perez GK, et al. : Childhood Cancer Survivor Study participants’ perceptions and understanding of the Affordable Care Act. J Clin Oncol 33:764-772, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nipp RD, Zullig LL, Samsa G, et al. : Identifying cancer patients who alter care or lifestyle due to treatment-related financial distress. Psychooncology 25:719-725, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zafar SY, McNeil RB, Thomas CM, et al. : Population-based assessment of cancer survivors’ financial burden and quality of life: A prospective cohort study. J Oncol Pract 11:145-150, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP, Jr, et al. : Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: Findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 34:259-267, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuhlthau KA, Nipp RD, Shui A, et al. : Health insurance coverage, care accessibility and affordability for adult survivors of childhood cancer: A cross-sectional study of a nationally representative database. J Cancer Surviv 10:964-971, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moy B, Polite BN, Halpern MT, et al. : American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement: Opportunities in the patient protection and affordable care act to reduce cancer care disparities. J Clin Oncol 29:3816-3824, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]