Abstract

During the past decade, there has been a continuous exploration of how virtual environments can be used to facilitate motor recovery and relearning after neurological impairment. There are two goals for using virtual environments: to improve patients’ rehabilitation outcomes beyond our current capabilities or to supplement labor-intensive and time consuming therapies with technology-based interventions. After over a decade of investigation, it seems appropriate to determine whether we are succeeding in meeting such goals.

Keywords: hemiplegia, motor rehabilitation, stroke, virtual reality

Introduction

Evolving ideas in neuroscience, computer science, and biomedical engineering have greatly influenced the development of a new generation of interventions for physical rehabilitation. During the past decade, there has been a continuous exploration of how virtual environments can be used to facilitate motor recovery and relearning after neurological impairment. The literature clearly shows a progression of articles, initially describing the potential applications of this technology, to feasibility studies testing out newly developed systems, and to small clinical trials. The construction of virtual environments that are used to rehabilitate motor deficits has progressed from simple two-dimensional self-timed reaching activities to more complex, immersive three-dimensional externally paced gaming activities, which incorporate important tactile information and interaction forces into what had been an essentially visual and auditory experience.

Combining adaptive robotic systems that interface with virtual environments has broadened the group of people that can utilize virtual reality (VR) and gaming technology for motor rehabilitation. The breadth of the VR systems ranges from expensive customized systems to less costly commercially available devices. The basis for the use of virtual environments in motor rehabilitation evolved from the concepts of adaptive activity-based neuroplasticity, task-oriented motor training, and the need for high doses of repetitive practice. The goals have been to either improve patients’ rehabilitation outcomes beyond our current capabilities, or to supplement labor-intensive and time consuming therapies with technology-based interventions.

After over a decade of investigation, it seems appropriate to ask “How are we doing?” In two recently published reviews [1, 2], the authors found that the use of virtual reality (including interactive gaming) showed slightly better outcomes compared with conventional therapy for people post stroke. However, there is limited evidence regarding the translation of these selected outcomes to real-world activities of daily living and functioning. Importantly, the studies included in these reviews used comparison groups that received alternate interventions or no interventions, but these groups did not necessarily receive interventions with comparable training intensity. This compromises the interpretation of the benefits of training in VR and leaves us to continue to wonder at how much progress we have achieved in this field. For the reasons stated above, it is time to parse out what we have learned during this past decade of ongoing investigations on the use of virtual environments for motor rehabilitation. This paper examined a number of important questions, including the following:

Have virtual reality/robotic interventions provided value in terms of intensity and dosing?

Do the quantitative/qualitative outcome measures that we have been using allow us to evaluate our subject’s progress meaningfully?

Do we know whether these interventions have been of personal value to the subjects?

Can these systems be implemented within the patient-client management models that are currently used in physical rehabilitation?

Are we utilizing the potential sensory and perceptual aspects of virtual reality in the most beneficial way?

Do we have an understanding of the underlying changes in brain connectivity and function elicited by VR interventions?

Finding answers to these questions will provide a critical substrate for all future works.

Virtual reality as a tool to provide intensive intervention dosing

The rehabilitation of neuromotor deficits has currently focused on repetitive task-oriented training and progressive practice. This motor learning principle parallels the principle of “use-dependent” repeated practice, which is purported to affect neuroplasticity and to modify neural organization. One of the difficulties in designing rehabilitation programs congruent with the literature, which supports repetitive task practice, is the labor-intensive nature of these interventions. Difficulties in the provision of adequate training volumes for persons with stroke are well documented [3]. Typical rehabilitation programs do not provide enough repetitions to elicit neuroplasticity.

In a study of 36 outpatient therapy sessions for persons with strokes, Lang observed that subjects performed an average of 27 repetitions of functional activities during these sessions. This volume of intervention stands in stark contrast to training volumes of 500–600 repetitions of tasks performed by animal subjects in stroke rehabilitation studies [4], and to the 600–800 repetitions of activity per hour [5–9] reported in virtual rehabilitation and robotic studies. This ability to deliver intensive, repeated task practice has been one of the underlying hallmarks of the benefits of VR interventions.

To date, most of the studies that investigated the therapeutic use of VR or VR/robotics have focused on superiority trials that utilized control comparison groups, which received either no care or the usual standard of clinical care [1]. However, three recently completed randomized control trials [RCTs], each testing an innovative therapeutic intervention (but not necessarily using virtual reality), have compared the putative intervention to both intensive comparison control groups and usual care groups, thus providing us with important information regarding this issue. In both the LEAPS trial, body-weight supported treadmill training (BWSTT) in stroke patients [10] and the SCILTS trial [11], BWSTT in persons with spinal cord injury, outcomes in terms of walking speed have been found to be equivalent between BWSTT and the equally intense comparison groups. In a study of patients, which used robot-assisted therapy for upper limb impairment post-stroke, improvement in the Fugl-Meyer score was better for patients receiving robot-assistive therapy than those receiving usual care, but worse than for those receiving intensive comparison therapy [12]. There was a consistent pattern across these three studies, i.e., there was no difference between the experimental and the intensive control groups, but both of these conditions were better than usual care. Thus, each study showed an effect not necessarily of the particular intervention but that of the intensity and increased dosage provided. Moreover, a cost-analysis done as part of a previous study [12] did not yield significant cost differences between the robot-assisted therapy and the intensive comparison study. However, in the future, one would expect that human supervised training will probably not become less costly, while technology based treatment will. This will definitely affect the cost equivalence.

There are several important take-away messages from these outcomes. 1) We can no longer design studies just with usual clinical care control groups; the comparison group must be of equal task intensity. 2) The use of VR/robotics as a tool for the delivery of treatment intensity is effective, but may not be superior to dose-matched training without VR/robotics. If repetition and skill learning are important for motor learning and recovery of function, do we need to determine what VR technology can add over and above real-world task practice ? What can training within an interactive virtual environment uniquely contribute to skill learning and improved motor control? It is vital to study how we can utilize the potential sensory and perceptual affordances of virtual reality in the most beneficial way, in order to provide improved motor learning experiences. Finally, it is necessary to reflect on methods to ease the transition of these elements into the current therapeutic frameworks for clinical practice. Looking to the future, we need to explore and develop rehabilitation applications of VR using such elements as task parameter and workspace scaling, on-line adaptive algorithms, modification of visual or proprioceptive feedback, and grading of the volume/speed/location/complexity of the task. The overarching question emerges, “How we can manipulate these elements, available through virtual environments, to facilitate motor skill development and effect excitability and functional connectivity of appropriate neural networks in the sensorimotor cortex?

Manipulating elements in VR to facilitate motor skill development

Activity scaling

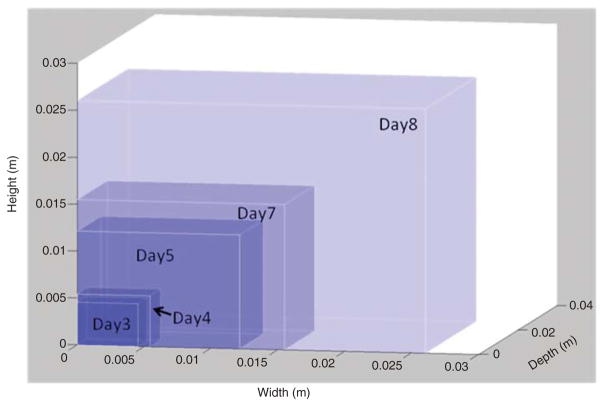

A skilled movement is characterized by consistency, stability, flexibility, and adaptability. These features are achieved through practice-dependent changes in kinematic and force errors [13]. With practice, one progresses through the stages of skill acquisition, eventually achieving a movement that is autonomous with fewer errors. Evidence suggests that repetitive practice resulting in “actual motor skill acquisition or motor learning” may be a more potent stimulus for “driving representational plasticity in the primary motor cortex”, than the simple repetition of activities that are well within the movement capabilities of a subject [14, 15]. Thus, activity scaling might be a critical issue related to neuroplasticity when considering the need for continuous skill development. Virtual environments are particularly well-suited to the systematic scaling of movements and task activities. The size of virtual workspaces, target sizes, and activity speeds and forces can be increased in small gradients throughout the training period, thus creating a gradually increasing level of difficulty for any task. Contrary to that, physical fatigue during large volume training sessions also presents challenges during motor training. Motor fatigue can be easily addressed in VR training through the same type of modifications [16]. Figure 1 shows the continuing changes in workspace volume over the course of the training period. It has been proposed that a favorable learning experience occurs when the task in neither too difficult nor too easy [17, 18]. The Cameirao study used a reaching task, in which the moving spheres move toward the participant who has to intercept them, the speed of the moving spheres, the interval between appearance of the spheres, and the horizontal spread of the spheres (i.e., size of the workspace) were all manipulated based upon patient success rate. In this study, the difficulty was increased by 10% when the participant intercepted more than 70% of the spheres, and was decreased when < 50% of the spheres were intercepted [17].

Figure 1.

In a training exercise with three-dimensional arm reaching, workspace expands gradually and continuously throughout the training period.

The distribution of the virtual targets in space and their distance from the subject can be controlled either through an online adaptive algorithm or by the therapy supervisor.

Activity scaling can be automated using online adaptive algorithms

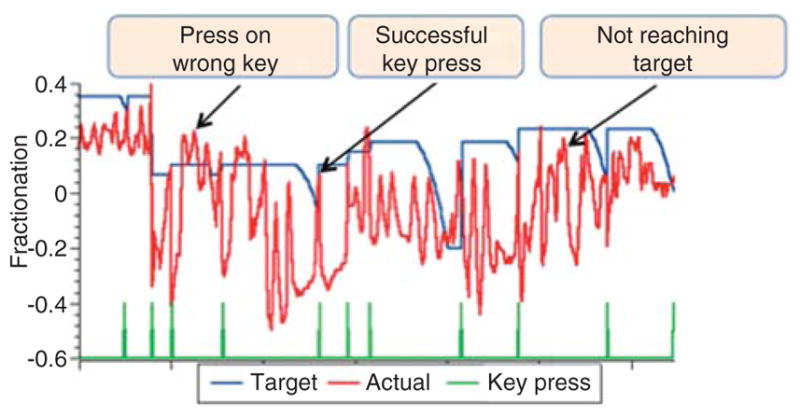

These can provide a controlled, systematic method to gradually increase or decrease the demands of an activity. We use these algorithms in several of our simulations. The Virtual Piano simulation consists of a complete virtual piano that plays the appropriate notes as they are pressed by the virtual fingers while the subject is wearing an instrumented glove. This simulation was designed to help improve the ability of subjects post-stroke to move each finger in isolation (fractionation). Fractionation is calculated as the difference in the amount of flexion in the finger joints between the cued finger and the most flexed non-cued finger. The best possible fractionation score is achieved when there is full flexion of the cued finger and the biomechanically allowable extension of the non-cued fingers. Task difficulty is manipulated to demand more isolated finger flexion, which in turn, elicits a key press as participants succeed, and less fractionation if their performance diminishes. Initial target fractionation is calculated based on each subject’s actual fractionation. If the actual fractionation reaches 90% of target fractionation, the next initial target fractionation is increased by 8% of the previous target fractionation; otherwise, the next initial target fractionation is decreased by 10% of previous target fractionation. Figure 2 shows an example of variation in the adjustable fractionation target based on an individual subject ’ s actual ability to isolate their fingers at each attempted key press. The blue line indicates the target fractionation, the red line is the actual fractionation, and the green line indicates when a key is successfully pressed. The left box shows the scenario when the subject reaches the target fractionation, but the finger is not aligned with the piano correct key. The right box shows the scenario when the subject fails to reach the target fractionation and the target is lowered.

Figure 2.

Adjustable fractionation target based on an individual subject’s actual ability to isolate their fingers at each attempted key press.

The blue line indicates the target fractionation, the red line indicates actual fractionation, and the green line indicates when key is successfully pressed. Left box shows the scenario when the subject reaches the target fractionation but presses the wrong key. The right box shows the scenario when the subject fails to reach the target fractionation and the target is lowered.

In the Hammer Task, we utilize an algorithm that increases and decreases the target area of the cylinder to be hammered. The Hammer Task trains a combination of three-dimensional reaching with two different repetitive distal movements. In one version of the game, the subjects reach towards a virtual wooden cylinder and then use finger extension or flexion to hammer the cylinders into the floor. The other version uses forearm supination and pronation to hammer the virtual wooden cylinders into a wall. The haptic effects allow the subject to feel the collision between the hammer and target cylinders as they are pushed through the floor or wall. Hammering sounds accompany collisions as well. The subjects receive feedback regarding the time it takes them to complete the series of hammering tasks. The programmed adaptive algorithm increases and decreases the target area of the cylinder to be hammered, which in turn, decreases and increases demand for hand stability as determined by the efficiency of elbow-shoulder coordination. This adaptation is related to the time it takes a subject to hammer each cylinder.

Visual motor discordance

Gain scaling

We have also used scaling of the gain between the amount of movement of the subject’s limb and of its virtual representation in several simulations. A gain algorithm is used to reinforce the amount of wrist rotation or finger extension needed to hammer the cylinders. If a subject is able to finish hammering the cylinder before it disappears, gain decreases and requires a bigger range of wrist rotation/finger extension to generate a displacement of the cylinder. A gain modification is also available in a Space Pong Game, in which we can decrease the gain from patient movement to virtual movement. This increases the amount of finger movement required to produce paddle movement, which is necessary to intercept the moving ball. We used this gain modification in a case study [16] when the subject had difficulty controlling his fingers to produce effective paddle movement, as evidenced by very low accuracy scores. After the first week of training, we decreased the gain from finger movement to paddle movement from 100% to 70%, which increased the amount of finger movement required to produce paddle movement. Gain was increased by 15% on day 6 and back to 100% on day 9 of the trial as the subject ’s accuracy scores increased.

Tunik [19] and co-workers investigated the effect of gain manipulation on neural circuits. In the experiments, in which the fingers of the hands in the VR display moved either 65%, 25% or 175% of the subjects’ actual movement, there was a definite effect of this visual manipulation on neural circuits. The discordance in gain between executed movement and observed feedback was associated with an increase in activation in contralateral M1. Analysis of movement kinematics confirmed that actual movement performance did not confound this result. A parsimonious explanation is that both low-gain feedback (25% and 65% conditions) and high-gain feedback (175% condition) up-regulated neural activity in the motor system as if M1 was acting to reduce the discrepancy between the intended action and the feedback indicating the finger is not moving as expected. Two complementary approaches to these manipulations utilize large patient movements compared with avatar movement for up-regulating the motor cortex, or large avatar movements when compared with patient movement that allows patients with very little active movement to generate purposeful avatar movements with their paretic upper extremity [19, 20].

Error augmentation

This is another example of an adaptive training method that uses visual distortions. In this paradigm, subjects post-stroke use their hemiparetic arm, which is supported by a robot to follow a trajectory path outlined on the computer screen by the therapist. The computer measures and magnifies the subject ’ s movement error in relation to the preferred trajectory, thereby forcing the subjects to improve their control. Error augmentation can be provided both visually and by forces generated by the robot. Although the clinical measures showed mixed results, and did not indicate functional gains, the results indicated that error augmentation was superior to an equal dosing of simple massed practice for skill development [21, 22].

Commercially available VR exercise systems

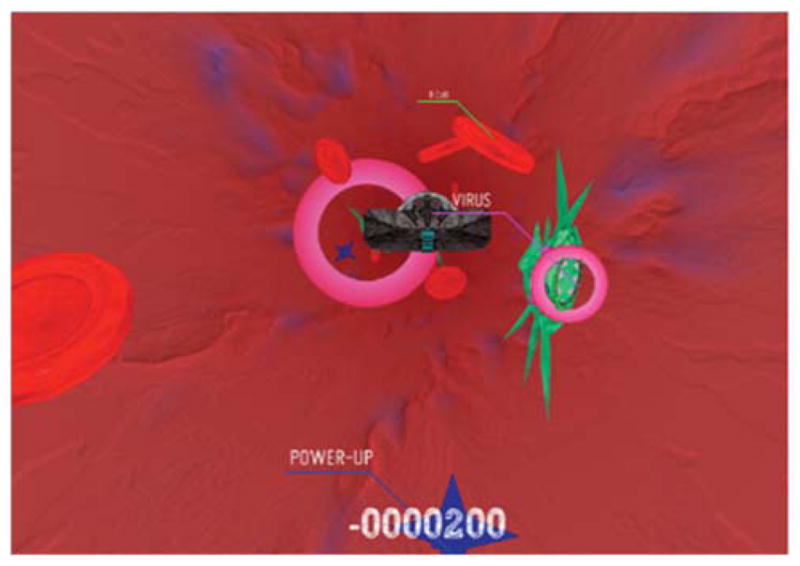

Two lines of inquiry, one utilizing lab-based customized systems and another examining consumer gaming technology for the rehabilitation of persons with disabilities, have been developed over several years. It is clear that lab-based systems are significantly more flexible and, therefore, usable for a larger percentage of persons with disabilities. The haptic component available in lab-based systems is a useful tool in the beginning of rehabilitation, when one is trying to initiate useful movement. For example, we have recently developed a library of therapeutic gaming activities, which utilize interactive environments and a six-degree-of-freedom robotic arm, suitable for both children [23, 24] and adults [9]. In a Spaceship game (Figure 3), subjects navigate a space ship in the presence of various objects moving towards the subject, with the aim of avoiding collisions with objects-invaders and intercepting “good” objects (Figure 3). Therapists or assistants supervising the therapy are able to adjust, using an intuitive, easy-to-use graphical user interface, various parameters of the game, including the speed of the moving space ships and objects, the size of the workspace and objects as well as the objects’ density, to gradually increase the difficulty of the motor task. Targets can be concentrated in quadrants to emphasize range of movement to a specific area of the patient’ s reachable space. In addition, we are able to manipulate various haptic effects provided by the robotic arm that subjects move in 3D space during the gaming activity: the magnitude of impact absorbed when colliding with invaders, the amount of anti-gravity arm support, and the amount of damping provided by the robot to stabilize the paretic arm, among others.

Figure 3.

Screen shot of the Spaceship Game.

The commercial gaming systems cannot provide kinematic outcome data nor can they be modified for individual patient impairment levels. However, the affordability of consumer-oriented systems and the entertainment values, which can be delivered by these platforms, bring considerable advantages. One can envision a rehabilitation sequence wherein the patient progresses from using complex adaptable lab-based systems during the in-patient/outpatient phase of rehabilitation, to continued use of home-based commercial systems similar to the concept of physical fitness and life-long exercise. Long-term adherence to home training and exercise programs is an important consideration in the management of patients with permanent disabilities. The design of rehabilitation activities for consumer platforms by engineers and therapists, who are experienced in accommodating the abilities and goals of persons with disabilities, is an area that needs to be explored for rehabilitation gaming to remain relevant.

Sensitivity of outcome measures

Various outcome measures that are currently being used in virtual reality/robotic research of arm and hand rehabilitation address outcomes at the three levels of function, which are determined by the World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, to describe health and function. The most common measures used are the Fugl-Meyer (FM), which tests impairments at the body function level; the Action Research Arm Test (ARAT); the Wolf Motor Function Test, the Jebsen Test of Hand Function and the Nine-Hole Peg Test, all at the activity level; and the Stroke Impact Scale, which tests at the participation level. Given the heterogeneity of the populations most often served by the VR interventions and the wide variation in patient outcomes, pertinent questions deal with whether these measures are sensitive enough to provide measurable evidence of the patient ’ s progress and functional change. These questions also have to address the ways by which we can further expand our ability to understand the impact of these newer interventions and their effect on long-term function. In a case study assessing long-term changes in paretic upper limb function [25], clinical assessments indicated that motor function (measured by FM) and functional abilities (measured by ARAT) plateaued by about eight weeks while the kinematic outcomes demonstrated ongoing recovery for six months. The authors suggested that standard clinical assessments used in clinical trials may not be sufficiently sensitive to capture further improvement due to a ceiling effect. The complex nature of neurorehabilitation may call for an integration or combination of quantitative and qualitative data in order to maximize the strength and minimize the weaknesses of each form of measurement, and to develop a more complete understanding of this complex phenomenon.

Conclusions

In conclusion, several areas of study are indicated to continue the development of VR environments and interventions aimed at fostering beneficial changes in motor rehabilitation. The first would be to expand the study of virtual interventions to include persons in the acute phase of recovery. Further, continued study of the manipulation of task difficulty (using either online algorithms or therapist mediated modifications) and the use of visuomotor discordance (including manipulation of the ratio of active patient movement to avatar movement) are areas to be studied to explore and determine the contributions unique contributions motor rehabilitation that can be made by practicing in virtual environments. Finally, further evolution of our clinical outcome measures is sorely needed. In addition to the need for more sensitive clinical measures, studies of interventions using virtual reality/robotics should include multiple types of measurements, possibly mixed method research designs, repeated kinematic analyses, and imaging studies, in order to understand recovery at both the functional and the neural levels.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grants RO3 HD42161 and R01 HD58301 and by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center (Grant # H133E050011).

Contributor Information

Alma S. Merians, Department of Rehabilitation and Movement Sciences, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, 65 Bergen Street, Newark, NJ 07107, USA.

Gerard Fluet, Department of Rehabilitation and Movement Sciences, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark, NJ, USA.

Eugene Tunik, Department of Rehabilitation and Movement Sciences, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark, NJ, USA.

Q. Qiu, Department of Rehabilitation and Movement Sciences, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark, NJ, USA

Soha Saleh, Department of Rehabilitation and Movement Sciences, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark, NJ, USA.

Sergei Adamovich, Department of Rehabilitation and Movement Sciences, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark, NJ, USA; and New Jersey Institute of Technology, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Newark, NJ, USA.

References

- 1.Laver KE, George S, Thomas S, Deutsch JE, Crotty M. Virtual reality for stroke rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;7:CD008349. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008349.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saposnik G, Levin M. Virtual reality in stroke rehabilitation: a meta-analysis and implications for clinicians. Stroke. 2011;42:1380–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.605451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lang C, Macdonald J, Gnip C. Counting repetitions: an observational study of outpatient therapy for people with hemiparesis post-stroke. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007;3:3–11. doi: 10.1097/01.npt.0000260568.31746.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleim JA, Jones TA. Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity: implications for rehabilitation after brain damage. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2008;51:225–39. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adamovich S, Merians A, Boian R, Tremaine M, Burdea G, Recce M, et al. A virtual reality based exercise system for hand rehabilitation post stroke. Presence. 2005;14:161–74. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2004.1404364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Housman SJ, Scott KM, Reinkensmeyer DJ. A randomized controlled trial of gravity-supported, computer-enhanced arm exercise for individuals with severe hemiparesis. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009;23:505–14. doi: 10.1177/1545968308331148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krebs HI, Mernoff S, Fasoli SE, Hughes R, Stein J, Hogan N. A comparison of functional and impairment-based robotic training in severe to moderate chronic stroke: a pilot study. Neuro Rehabil. 2008;23:81–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lum PS, Burgar CG, Shor PC. Evidence for improved muscle activation patterns after retraining of reaching movements with the MIME robotic system in subjects with post-stroke hemiparesis. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2004;12:186–94. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2004.827225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merians A, Fluet GG, Qiu Q, Saleh S, Lafond I, Adamovich SV. Robotically facilitated virtual rehabilitation of arm transport integrated with finger movement in persons with hemiparesis. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2011;8:27. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-8-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duncan PW, Sullivan KJ, Behrman AL, Azen SP, Wu SS, Nadeau SE, et al. Body-weight-supported treadmill rehabilitation after stroke. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2026–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dobkin B, Apple D, Barbeau H, Basso M, Behrman A, Deforge D, et al. Weight-supported treadmill vs over-ground training for walking after acute incomplete SCI. Neurology. 2006;66:484–93. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000202600.72018.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lo AC, Guarino P, Krebs HI, Volpe BT, Bever CT, Duncan PW, et al. Multicenter randomized trial of robot-assisted rehabilitation for chronic stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009;23:775–83. doi: 10.1177/1545968309338195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krakauer JW. Motor learning: its relevance to stroke recovery and neurorehabilitation. Curr Opin Neurol. 2006;19:84–90. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000200544.29915.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plautz EJ, Milliken GW, Nudo RJ. Effects of repetitive motor training on movement representations in adult squirrel monkeys: role of use versus learning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2000;74:27–55. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1999.3934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Remple MS, Bruneau RM, VandenBerg PM, Goertzen C, Kleim JA. Sensitivity of cortical movement representations to motor experience: evidence that skill learning but not strength training induces cortical reorganization. Behav Brain Res. 2001;23:133–41. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fluet GG, Merians AS, Qui Q, Lafond I, Saleh S, Ruano V, et al. Robots integrated with virtual reality simulations for customized motor training in a person with upper extremity hemiparesis: acase study. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2012;36:79–86. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0b013e3182566f3f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cameirao MS, Badia SB, Oller ED, Verschure PF. Neurorehabilitation using the virtual reality based rehabilitation gaming system: methodology, design, psychometrics, usability and validation. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2010;7:48. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-7-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jack D, Boian R, Merians AS, Tremaine M, Burdea GC, Adamovich SV, et al. Virtual reality-enhanced stroke rehabilitation. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2001;9:308–18. doi: 10.1109/7333.948460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tunik E, Saleh S, Adamovich S. Visuomotor discordance during visually-guided hand movement in Virtual Reality modulates sensorimotor cortical activity in healthy and hemiparetic subjects. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2013 Jan 9; doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2013.2238250. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bagce HF, Saleh S, Adamovich SV, Tunik E. Visuomotor discordance in virtual reality: effects on online motor control. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med BiolSoc. 2011:7262–65. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2011.6091835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patton JL, Stoykov ME, Kovic M, Mussa-Ivaldi FA. Evaluation of robotic training forces that either enhance or reduce error in chronic hemiparetic stroke survivors. Exp Brain Res. 2006;168:368–83. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patton JL, Wei YJ, Bajaj P, Scheidt RA. Visuomotor learning enhanced by augmenting instantaneous trajectory error feedback during reaching. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e46466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qiu Q, Ramirez DA, Saleh S, Fluet GG, Parikh HD, Kelly D, et al. The New Jersey Institute of Technology Robot-Assisted Virtual Rehabilitation (NJIT-RAVR) system for children with cerebral palsy: a feasibility study. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2009;6:40. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-6-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fluet GG, Qiu Q, Kelly DF, Parikh HD, Ramirez D, Saleh S, et al. Intefacing a haptic robotic system with complex virtual environments to treat impaired upper extremity motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Neurorehabil. 2010;13:335–45. doi: 10.3109/17518423.2010.501362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Kordelaar J, van Wegen EE, Nijland RH, de Groot JH, Meskers CG, Harlaar J, et al. Assessing longitudinal change in coordination of the paretic upper limb using on-site 3-dimensional kinematic measurements. Phys Ther. 2012;92:142–51. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]