Abstract

Objective

To examine risk factors associated with use of e-cigarettes only, conventional cigarettes only, and dual use in Korean adolescents and young adults.

Methods

In a cross-sectional study, anonymous questionnaires were completed between April-May, 2015 among 1) 2744 middle and high school students, aged 13–18, from Seoul, Incheon, Gyeonggi, and Cheongju, Korea and 2) 2167 university students, aged 19–29, from fourteen universities in Korea.

Results

The results show that 12.6% of adolescents and 21.2% of university students reported having ever tried e-cigarettes at least once. Among the ever e-cigarette users, 95.1% and 96.3% of adolescents and university students also tried conventional cigarettes, respectively. Dual users were more likely to be male (adolescents: OR 2.63, 95% CI 1.93–3.57; university students: 4.28, 3.21–5.70), have any close friends who smoke (adolescents: 11.56, 7.63–17.53; university students: 11.29, 5.52–23.10), have any siblings who smoke (adolescents: 3.17, 2.25–4.46; university students: 1.78, 1.30–2.43), and have observed teachers smoke cigarettes at school (adolescents: 1.45, 1.05–2.01).

Conclusions

A majority of e-cigarette users were dual users. Friends’ and siblings’ smoking status were significantly associated with dual product use in adolescent and young adult populations. Surveillance of e-cigarette use and implementation of evidence-based behavioral interventions targeting adolescents and young adults are necessary.

Keywords: Electronic cigarettes, Dual use, Adolescents, University students

1. Introduction

Electronic cigarettes (or e-cigarettes) are battery-powered devices that generate an aerosol of vapor without combustion. The e-cigarette liquid (“e-liquid”) usually consists of a combination of propylene glycol and vegetable glycerine as the vehicle, with variable concentrations of nicotine and flavor additives (Etter and Bullen, 2011; WHO, 2009). Experimentation with and regular use of e-cigarettes is growing rapidly in some countries, particularly among adolescents and young adults. This epidemic rise is well documented in the United States (Singh et al., 2016), and some prior studies show that e-cigarette use is also occurring in Korea, motivating the study that we report here (Lee et al., 2014).

Because e-cigarettes have only recently been widely used, the effects of e-cigarettes on human health have not yet been well characterized, but the products have been proposed as offering a harm reduction alternative to conventional, combusted cigarettes (Royal College of Physicians, 2016). The emergence of e-cigarettes may promote cigarette smoking reduction by substituting e-cigarettes for the biochemical and behavioral aspects of cigarette nicotine addiction (Brose et al., 2015), but empirical study of the harm reduction benefits of e-cigarettes has been limited. While e-cigarettes may prove useful for harm reduction, there is rising concern that these products will introduce adolescents and young adults to nicotine and lead to dual use with conventional cigarettes, and possibly to regular use of cigarettes and nicotine addiction (Barrington-Trimis et al., 2015). Consequently, there is a need to track closely the use of e-cigarettes by adolescents and young adults.

To effectively educate and counsel individuals using multiple tobacco products, identification of factors associated with concurrent use is important; however, risk factors for e-cigarette use alone and dual use with conventional cigarettes have received limited attention to date, particularly in Korea. Therefore, the aim of this study is to explore and compare factors associated with e-cigarette use and with dual use in Korean adolescents and university students.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The study participants were recruited for the 2015 Yonsei Health Study, which included 2744 adolescents and 2167 university students. Adolescents aged 13–18 years voluntarily participated in the 20–40 min survey which was conducted in each classroom of middle and high schools located in Seoul, Incheon, Gyeonggi, and Cheongju, Korea. University students were volunteers aged 19 years and older who participated in the same survey conducted at 14 different university campuses located in Seoul, Gyeonggi, GyeongBuk, Gyeongnam, Busan, ChungBuk, Daejeon, Jeonju, Gwangju, and Jeju Island. Middle and high schools and universities were approached and selected because of their diverse demographic characteristics. Adolescents from grade 7 to grade 12 and university students from year 1 to year 4 were included in the analysis. Survey questions were obtained from the Southern California Children’s Health Study (CHS) survey questionnaire and the 2013 Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS; Barrington-Trimis et al., 2015; WHO, 2013). All schools and universities agreed to participate in the study.

2.2. Procedure

Each participant completed an anonymous, written questionnaire that was collected by research staff in the classroom. All participants provided written informed consent, approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Research at Yonsei University (No.4-2015-0078). Each student was given $5 worth of stationery supplies after completion of the survey.

2.3. Measures

Lifetime use of conventional or electronic cigarettes was assessed by asking “Have you ever used cigarettes/e-cigarettes in your life?” (yes/no). Current use of conventional or e-cigarettes was assessed by asking “During the last 30 days, have you used conventional/electronic cigarettes?” (yes/no). Participants who concurrently or ever used both conventional and e-cigarettes were classified as dual users. Smoking of combustible cigarettes by parents, siblings, and peers was assessed for each participant by asking “Do any of your family members (father/mother/siblings/others) or your close friends smoke (none/a few/most/all)? Select all that apply.” Adolescents were also asked whether they had seen school teachers smoking outdoors or on the school premises. Sociodemographic variables included age, gender, type of school (middle/high/university), and field of study. Prior to the survey, a pilot survey was conducted among 15 young adults, aged 20–29 years, working at Severance Hospital and 300 middle and high school students in Cheongju city, Korea to optimize the survey questions.

2.4. Data analysis

The proportion pertaining to each study variable was compared across e-cigarette only users, conventional cigarette only users, and dual user groups. Multinomial logistic regression analyses were performed to assess the independent associations of e-cigarette only use, conventional cigarette only use, and dual use with factors related to ever-/current conventional or e-cigarette use among adolescents and university students. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

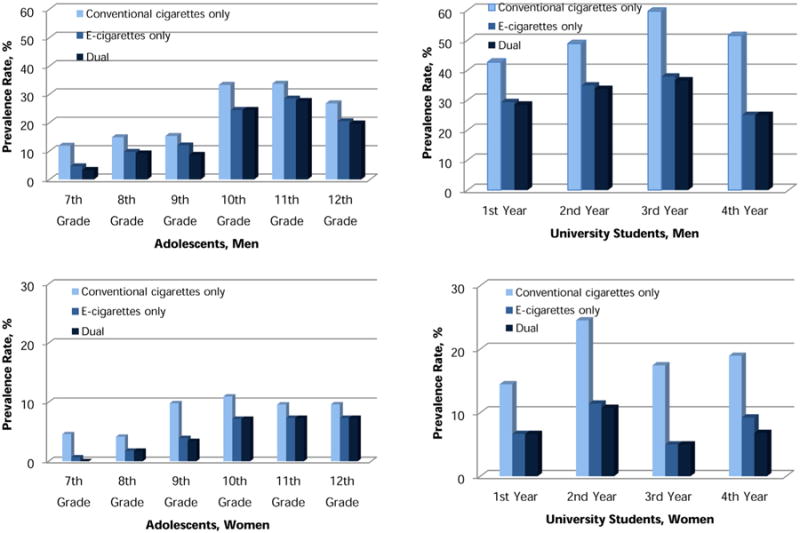

For adolescents and university students, the rates of conventional cigarette only use, e-cigarette only use, and dual use increased with increasing age and grade (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S1 in the online version at DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.08.636).

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of ever conventional cigarette, e-cigarette, and dual use by school year among adolescents and university students.

Table 1 presents findings on ever- and current use of conventional cigarettes only, e-cigarettes only, and dual use groups among the adolescents and the university students. A total of 2246 adolescents (81.9%) and 1363 (62.9%) university students had never smoked a conventional cigarette or used an e-cigarette. Among adolescent males, 7.3% and 1.0% had ever used cigarettes only and e-cigarettes only, respectively, compared with 19.6% and 0.9% of university students who had ever used cigarettes only and e-cigarettes only, respectively. About 12.0% of adolescents and 20.4% of university students reported having ever tried both conventional and e-cigarettes. University students who currently or ever used tobacco products were more likely to be exclusive conventional cigarette only users than e-cigarette only or dual users. Prevalence estimates of ever dual use of conventional and e-cigarettes were higher among male adolescents and university students (17.7% and 31.5%, respectively), compared to female students (5.1% and 7.5%, respectively).

Table 1.

Ever- and last 30 days of conventional cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and dual use among Korean adolescents and university students.

| N (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Total | Male | Female | |

| Adolescents | 2744(100.0) | 1496(100.0) | 1248(100.0) |

| Ever use | |||

| Never user | 2246(81.9) | 1108(74.1) | 1138(91.2) |

| Cigarette only user | 153 (5.6) | 109(7.3) | 44 (3.5) |

| E-cigarette only user | 17(0.6) | 15(1.0) | 2 (0.2) |

| Dual user | 328(12.0) | 264(17.7) | 64(5.1) |

| Last 30 days use | |||

| Never user | 2441 (89.0) | 1243(83.1) | 1198(96.0) |

| Cigarette only user | 130 (4.7) | 103 (6.9) | 27 (2.2) |

| E-cigarette only user | 38(1.4) | 31 (2.1) | 7 (0.6) |

| Dual user | 135 (4.9) | 119(8.0) | 16(1.3) |

| University Students | 2167(100.0) | 1166(100.0) | 1001 (100.0) |

| Ever use | |||

| Never user | 1363 (62.9) | 560 (48.0) | 803 (80.2) |

| Cigarette only user | 345(15.9) | 229(19.6) | 116(11.6) |

| E-cigarette only user | 17(0.8) | 10(0.9) | 7 (0.7) |

| Dual user | 442 (20.4) | 367 (31.5) | 75 (7.5) |

| Last 30 days use | |||

| Never user | 1656(76.4) | 735 (63.0) | 921 (92.0) |

| Cigarette only user | 356(16.4) | 300 (25.7) | 56 (5.6) |

| E-cigarette only user | 27(1.3) | 22(1.9) | 5 (0.5) |

| Dual user | 128 (5.9) | 109 (9.4) | 19(1.9) |

Table 2 summarizes the associations between factors potentially related to conventional cigarette only, e-cigarette only, and dual use among adolescents and university students. Both adolescents and university students who had a close friend who smoked had significantly higher odds of using e-cigarettes in their life-time (adolescents: OR 8.58, 95% CI 5.95–12.37; university students: 8.63, 4.65–16.01), compared to those who did not have any close friend who smoked. This factor showed higher association with lifetime e-cigarette only use than lifetime conventional cigarette only use (adolescents: OR 6.79, 95% CI 5.13–9.01; university students: 4.33, 3.10–6.04). Adolescents who had seen their teachers smoke had about 71% greater risk of currently using e-cigarettes only (OR 1.71, 95% CI 1.12–2.62) but twice the risk of smoking conventional cigarettes (OR 2.02, 95% CI 1.40–2.91). No significant associations were found between current dual use of conventional and e-cigarettes and teacher’s smoking status among adolescents. In addition, parental smoking was not significantly associated with neither ever nor current conventional, e-cigarettes, and dual use in adolescents, but significantly associated with current conventional cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and dual users among university students.

Table 2.

Relationship between factors and ever- and last 30 days e-cigarettes, conventional cigarettes, and dual use among Korean adolescents and university students.

| Variables | Adolescents**

|

University Students**

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Cigarette Only Use OR* (95% CI) |

E-cigarette Only Use OR* (95% CI) |

Dual Use OR* (95% CI) |

Conventional Cigarette Only Use OR* (95% CI) |

E-cigarette Only Use OR* (95% CI) |

Dual Use OR* (95% CI) |

|

| Ever use | ||||||

| Male | 2.44(1.90–3.13)*** | 2.81 (2.08–3.79) | 2.63 (1.93–3.57) | 3.20 (2.57–3.97) | 4.09 (3.09–5.40) | 4.28 (3.21–5.70) |

| Age, year | 1.11 (1.03–1.19) | 1.20(1.10–1.31) | 1.24(1.13–1.35) | 1.11 (1.05–1.16) | 1.02 (0.96–1.08) | 1.02 (0.97–1.08) |

| Any close friends smoking | 6.79(5.13–9.0l) | 8.58 (5.95–12.37) | 11.56 (7.63–17.53) | 4.33 (3.10–6.04) | 8.63 (4.65–16.01) | 11.29 (5.52–23.10) |

| Any siblings smoking | 2.88(2.10–3.94) | 3.25 (2.33–4.55) | 3.17 (2.25–4.46) | 2.14 (1.61–2.84) | 1.75 (1.28–2.38) | 1.78 (1.30–2.43) |

| Parents smoking | 1.21 (0.97–1.52) | 1.10(0.86–1.42) | 1.07 (0.82–1.38) | 1.36(1.12–1.66) | 1.24 (0.99–1.56) | 1.26(1.00–1.58) |

| Teacher smoking | 1.52 (1.15–1.99) | 1.38(1.01–1.89) | 1.45 (1.05–2.01) | – | – | – |

| Last 30days use | ||||||

| Male | 3.28 (2.29–4.70) | 3.82 (2.41–6.07) | 4.31 (2.50–7.44) | 5.16 (3.87–6.87) | 4.05 (2.52–6.51) | 4.09 (2.42–6.89) |

| Age, year | 1.27(1.15–1.40) | 1.22(1.08–1.37) | 1.19(1.04–1.36) | 1.05 (0.99–1.11) | 1.05 (0.97–1.14) | 1.02 (0.93–1.12) |

| Any close friends smoking | 11.78(7.14–19.44) | 12.80(6.63–24.72) | 12.02 (5.76–25.10) | 7.31 (4.11–12.98) | 3.21 (1.46–7.05) | 9.84 (2.39–40.43) |

| Any siblings smoking | 3.76 (2.62–5.40) | 3.18(2.11–4.78) | 4.11 (2.68–6.31) | 2.41 (1.78–3.28) | 1.65 (1.06–2.56) | 1.95 (1.23–3.09) |

| Parents smoking | 1.22(0.92–1.62) | 1.14(0.82–1.60) | 1.09 (0.75–1.57) | 1.25 (1.00–1.56) | 1.76 (1.26–2.47) | 1.56 (1.08–2.25) |

| Teacher smoking | 2.02(l.40–2.9l) | 1.71 (1.12–2.62) | 1.58 (0.99–2.53) | – | – | – |

Adjusted for all variables in the table.

References for each group are non-smoker/non e-cigarette user.

Boldded font indicates statistical significance.

In adolescents, shared factors associated with ever- and current use of conventional cigarettes only, e-cigarettes only, and dual use in the multivariable model include male gender, age, having a close friend who smoked, and having any sibling who smoked. For adolescents, having seen teachers smoking showed a statistically significant risk for both ever- and current use of conventional cigarettes and e-cigarettes. In university students, similar risk factors to adolescents were shared, except for having any parents who smoked.

4. Discussion

This study concurrently examines and compares e-cigarette only use and dual use with cigarette only use among Korean adolescents and university students, providing insights into such use by age. Not surprisingly, university students had higher prevalence of ever- and current conventional cigarette only, e-cigarette only and dual use than adolescents. However, university students who used tobacco products were more likely to be exclusive conventional cigarette only users than e-cigarette only or dual users. We identified tobacco product use by teachers to be a risk factor for use by students. Other strong risk factors were friends’ and siblings’ use of each tobacco product and dual use. All factors, except for parents’ smoking status among university student e-cigarette only users and teachers’ smoking status among adolescent dual users, showed significant associations with conventional cigarette only, e-cigarette only, and dual use among both adolescents and university students.

Other recent surveys have documented substantial use of e-cigarettes. Surveys in the United States (Arrazola et al., 2015; McCarthy, 2015), New Zealand (White et al., 2015), Korea (Lee et al., 2014), France (Tavolacci et al., 2016), and Poland (Goniewicz et al., 2014) have reported high rates of e-cigarette use among adolescents and young adults. For example, a nationally representative survey in the United States found that e-cigarettes were the most commonly used tobacco product among high school students in 2014, and current (past 30 days) use of e-cigarettes increased approximately nine-fold from 2011 to 2014 among high school students (1.5% in 2011; 13.4% in 2014) and tripled among middle school students (1.1% in 2011; 3.9% in 2014) (Arrazola et al., 2015; McCarthy, 2015; Singh et al., 2016). A study in New Zealand documented a substantial increase of e-cigarette ever use among adolescents from 7.9% in 2012 to 20.0% in 2014 (White et al., 2015). There are only a few reports on dual use rates. The e-cigarette and dual use experience rates were 7.8% and 21.8%, respectively, in Poland (Goniewicz et al., 2014) and 1.4% and 8.0%, respectively, in Korea (Lee et al., 2014). In the Korean study, e-cigarette use was significantly higher among current heavier conventional cigarette users compared to never or former conventional cigarette users (Lee et al., 2014).

A previous study of Korean adolescents based on the 2011 Korean Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey found that 9.4% had ever used e-cigarettes, 4.7% had used e-cigarettes in the past 30 days, and 8.0% had ever used cigarettes and e-cigarettes concurrently (Lee et al., 2014). This prevalence was substantially lower than the prevalence of ever e-cigarette use in our study. In our study, the prevalence was twenty-fold higher than those reported in a cross-sectional study of 4341 middle and high school students (0.5%) (Cho et al., 2011). Tenth graders in the 2014 study had the highest e-cigarette use, while 12th graders had the highest conventional cigarette use (Lee et al., 2014). Similar to the previous study, our study found the highest e-cigarette and conventional cigarette use among the 11th graders in males and 10th graders in females. This may be because, with an increase in the amount of time spent, intimacy with peers who smoked may also rise over the course of early adolescent years (Simons-Morton et al., 2001; Simons-Mortan and Farhat, 2010).

Social risk factors for smoking conventional cigarettes identified in the present study are in line with the literature (Hanewinkel and Isensee, 2015; Kuntz and Lampert, 2013; Surís et al., 2015). The 2012 US Surgeon General’s report documented that adolescents are more likely to use tobacco if such use is viewed as acceptable among peers (US FDA, 2012). A recent cross-sectional study of 480 Romanian university students provided evidence that peer use was a stronger predictor of e-cigarette use than familial use. For example, students with friends who had tried e-cigarettes were more likely to experiment with e-cigarettes than those who had a family member who smoked conventional cigarettes. Male gender and history of conventional cigarette use were also strongly associated with e-cigarette use (Lotrean, 2015). A cohort study in New Zealand found factors such as gender and close friends’ smoking status were associated with e-cigarette ever use (White et al., 2015). These results are similar to ours, as all conventional, e-cigarettes, and dual users showed the statistically highest associations for having any close friends smoking. Since e-cigarettes were only recently introduced, determination of potential e-cigarette specific risk factors such as friends’ and family’s vaping is necessary.

This study is subject to several limitations. First, obtaining consent from adolescents may have affected reporting as students might not have been completely assured of the anonymity of the survey. Thus, reporting of cigarette and e-cigarette use may have been biased, likely downwards. Second, because this is self-reported survey, findings are subject to information bias generally; we tried to assure accuracy of responses by having a research staff member present when the data were collected. In addition, female participants may have underreported their smoking status, as smoking is still viewed as culturally unacceptable for women in Korean society (Lee et al., 2011). Third, this is a cross-sectional study with the inherent limitation of not providing information on the natural history of product use. Few studies to date have concurrently examined factors associated with e-cigarette use among Asian adolescents and university students. In our study in Korea, we found trends similar to those previously reported (Lotrean, 2015; White et al., 2015).

In an effort to lower the high rates of smoking among males, the South Korean government completely banned smoking in all bars and restaurants and doubled the price of cigarettes from 2500 won ($2.25) to 4500 won ($4.25) in January, 2015. While Korea lacks strict regulatory action on e-cigarettes, imports and sales have soared following the tax hike. Questions have been raised as to the impact of such changes on patterns of use and sales, especially among the younger population. Some regulators believe e-cigarette use among adolescents may have increased as a result (Han et al., 2015).

A majority of e-cigarette users were dual users. Friends’ and siblings’ smoking status have significant correlation with dual users in adolescent and young adult. There is a clear need for surveillance of e-cigarette use in key populations in Korea—adolescents and young adults. Evidence-based interventions and possibly regulation are needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants and staffs of eleven middle and high schools (Gyeongseong High School, Hongik Design High School, Sannam Middle School, Eunhye High School, Eunhye Middle School, Incheon Gojan High School, Incheon Youngsun High School, Jaeneung High School, Gageong Middle School, Ochang High School, and Jakjeon Middle School) as well as fourteen universities (Chung-ang University, Yonsei University, Kyonggi university, Eulji University, Gangneung-Wonju National University, Pohang University of Science and Technology, Uiduk University, Jinju Health College, Dongseo University, Chungbuk National University, Chungnam National University, Jeonju Kijeon College, Chosun University, and Halla University) for providing all necessary assistance and help. We also thank the staffs of the Institute for Health Promotion at Yonsei University for their help in data collection and technical assistance.

Role of funding source

This research was supported by a grant (14182MFDS977) from Ministry of Food and Drug Safety, Republic of Korea in 2016.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

Christina Jeon made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, data analysis, interpretation of data, drafting the article, revised version and answering all feedback.

Keum Ji Jung contributed to the interpretation of the data, submission, revising the article, and answering all feedback.

Heejin Kimm contributed to the interpretation of the data, submission and revising the article.

Sungkyu Lee contributed to the interpretation of the data, submission and revising the article.

Jessica L. Barrington-Trimis contributed to the interpretation of the data, submission and revising the article.

Rob McConnell contributed to the interpretation of the data, submission and revising the article.

Jonathan M. Samet contributed to the conception and design of the study, interpretation of the data, submission, revising the article, and answering all feedback.

Sun Ha Jee contributed to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of the data, analysis, interpretation of the data, submission, revising the article, and answering all feedback.

Contributors

All authors have participated in the design, execution, and analysis of the paper.

References

- Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, Husten CG, Neff LJ, Apelberg BJ, Bunnell RE, Choiniere CJ, King BA, Cox S, McAfee T, Caraballo RS. Tobacco use among middle and high school students-United States, 2011–2014. MMWR. 2015;64:381–385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrington-Trimis JL, Berhane K, Unger JB, Cruz TB, Huh J, Leventhal AM, Urman R, Wang K, Howland S, Gilreath TD, Chou CP, Pentz MA, McConnell R. Psychosocial factors associated with adolescent electronic cigarette and cigarette use. Pediatrics. 2015;136:308–317. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brose LS, Hitchman SC, Brown J, West R, McNeill A. Is the use of electronic cigarettes while smoking associated with smoking cessation attempts, cessation and reduced cigarette consumption? A survey with a 1-year follow-up. Addiction. 2015;110:1160–1168. doi: 10.1111/add.12917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho JH, Shin EY, Moon SS. Electronic cigarette smoking experience among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2011;49:542–546. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etter JF, Bullen C. Saliva cotinine levels in users of electronic cigarettes. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:1219–1220. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00066011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goniewicz ML, Gawron M, Nadolska J, Balwicki L, Sobczak A. Rise in electronic cigarette use among adolescents in Poland. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:713–715. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanewinkel R, Isensee B. Risk factors for e-cigarette, conventional cigarette, and dual use in German adolescents: a cohort study. Prev Med. 2015;74:59–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JO, Im JS, Yim J, Choi YH, Ko KP, Kim J, Kim HG, Noh Y, Lim YK, Oh DK. Association of cigarette prices with the prevalence of smoking in Korean university students: analysis of effects of the tobacco control policy. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:5531–5536. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.13.5531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntz B, Lampert T. Educational differences in smoking among adolescents in Germany: what is the role of parental and adolescent education levels and intergenerational educational mobility? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10:3015–3032. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10073015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Kimm S, Yun JE, Jee SH. Public health challenges of electronic cigarettes in South Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2011;44:235–241. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2011.44.6.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Grana RA, Glantz SA. Electronic cigarette use among Korean adolescents: a cross-sectional study of market penetration, dual use, and relationship to quit attempts and former smoking. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54:684–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotrean LM. Use of electronic cigarettes among Romanian university students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:358. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1713-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy M. Alarming rise in popularity of e-cigarettes is seen among US teenagers as use triples in a year. BMJ. 2015;350:h2083. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Physicians. Nicotine Without Smoke: Tobacco Harm Reduction. London: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Mortan B, Farhat T. Recent findings on peer group influences on adolescent substance use. J Prim Prev. 2010;31:191–208. doi: 10.1007/s10935-010-0220-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B, Haynie DL, Crump AD, Eitel SP, Saylor KE. Peer and parent influences on smoking and drinking among early adolescents. Health Educ Behav. 2001;28:95–107. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh T, Arrazola RA, Corey CG, Husten CG, Neff LJ, Homa DM, King BA. Tobacco use among middle and high school students-United States, 2011–2015. MMWR. 2016;65:361–367. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6514a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surís JC, Berchtold A, Akre C. Reasons to use e-cigarettes and associations with other substances among adolescents in Switzerland. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;153:140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavolacci MP, Vasiliu A, Romo L, Kotbagi G, Kern L, Lander J. Patterns of electronic cigarette use in current and ever users among college students in France: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011344. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth And Young Adults: A Report Of The Surgeon General US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation. Report On The Scientific Basis Of Tobacco Product Regulation: Third Report Of A WHO Study Group. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. Global Youth Tobacco. Survey (GYTS) WHO; Geneva: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- White J, Li J, Newcombe R, Walton D. Tripling use of electronic cigarettes among New Zealand adolescents between 2012 and 2014. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:522–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.