Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia. However, the etiopathogenesis of this devastating disease is not fully understood. Recent studies in rodents suggest that alterations in the gut microbiome may contribute to amyloid deposition, yet the microbial communities associated with AD have not been characterized in humans. Towards this end, we characterized the bacterial taxonomic composition of fecal samples from participants with and without a diagnosis of dementia due to AD. Our analyses revealed that the gut microbiome of AD participants has decreased microbial diversity and is compositionally distinct from control age- and sex-matched individuals. We identified phylum- through genus-wide differences in bacterial abundance including decreased Firmicutes, increased Bacteroidetes, and decreased Bifidobacterium in the microbiome of AD participants. Furthermore, we observed correlations between levels of differentially abundant genera and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers of AD. These findings add AD to the growing list of diseases associated with gut microbial alterations, as well as suggest that gut bacterial communities may be a target for therapeutic intervention.

Introduction

Despite decades of research, the etiology underlying the development of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) remains unknown, and there are currently no preventative or disease-modifying treatments available. In the brain, AD pathology is characterized by extracellular plaques composed of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein1. However, what causes these hallmark features is unexplained. In recent years, researchers have proposed a potential role for pathogenic microbes, including those derived from the gut, in the development or exacerbation of AD pathology2–5.

Humans harbor complex communities of microbes, with the vast majority of the microbial population residing in the distal gut. Gut microbes perform key functions for human health including energy extraction, biosynthesis of vitamins, protection against pathogen overgrowth, and education of the immune system6. Microbial colonization of the gut occurs during birth, is highly dynamic through infancy, and resembles adult structure by about 3 years of age7. Thereafter, the composition of the microbiome within an individual remains generally stable8, albeit with substantial interpersonal variation, particularly in elderly individuals9.

Alterations in the composition of this complex ecosystem have been associated with the development of a variety of gastrointestinal and metabolic diseases including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), obesity, diabetes, and insulin resistance10. More recently, the influence of gut microbiota on central nervous system function – often referred to as the gut-brain axis – has received significant attention, and alterations in the gut microbiome have been associated with neurological conditions including autism spectrum disorder, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson’s disease11–13.

With respect to dementia, a recent study in cognitively impaired elderly participants investigated a limited number of pro- and anti-inflammatory gut bacterial taxa and found altered abundance in individuals with positive amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) imaging14. In addition, recent studies in transgenic mouse models of AD have demonstrated that manipulating gut microbiota can influence cerebral amyloid deposition15,16. However, to date there have been no comprehensive surveys of whole gut microbiota in humans with AD. In this study, we performed bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing of DNA isolated from fecal samples in order to characterize the gut microbial communities in individuals with and without a clinical diagnosis of dementia due to AD. In addition, we examined the relationship between gut microbiota and AD pathology as measured by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers of AD.

Results

Study Design and Participant Characteristics

Participants were recruited from the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) and the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention (WRAP) study (see Methods). Gut microbiome compositional analysis was performed on fecal samples collected from home-dwelling participants with dementia due to AD (n = 25), and age- and sex-matched Control participants (n = 25). Table 1 reports participant characteristics. AD and Control groups did not differ with respect to age, sex, ethnicity, BMI, or diabetes status. There was no difference between groups in total score on a 15-item food questionnaire based on the Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) Diet17, which provided a semi-quantitative measure of dietary intake and allowed us to asses dietary differences. As expected, the APOE ε4 genotype was more prevalent in the AD group. The majority of AD participants had very mild or mild dementia, with clinical dementia rating (CDR) scores ranging from 0.5–2. Medication information is reported in Supplementary Table S1. The AD group had a greater number of participants taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and all but one AD participant was taking an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (donepezil or rivastigmine) and/or memantine.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Control | AD | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 25 | 25 | |

| Age (yrs, mean ± SD) | 69.3 ± 7.5 | 71.3 ± 7.3 | 0.346 |

| Sex (% Female) | 72% (18/25) | 68% (17/25) | 0.785 |

| Clinical dementia rating (CDR) score | NA | ||

| 0–normal | 100% (25/25) | 0 | |

| 0.5–very mild dementia | 40% (10/25) | ||

| 1–mild dementia | 36% (9/25) | ||

| 2–moderate dementia | 24% (6/25) | ||

| APOE ε4 genotype | 20% (5/25) | 72% (18/25) | <0.001* |

| Ethnicity (% Caucasian) | 96% (24/25) | 92% (23/25) | 0.552 |

| BMI (kg/m2, median [IQR]) | 26.1 [24.3–33.2] | 26.0 [22.9–29.1] | 0.467 |

| Diabetes diagnosis | 2/25 | 2/25 | 1.000 |

| MIND Diet total score (mean ± SD) | 7.6 ± 2.2 | 6.6 ± 2.7 | 0.160 |

| Bristol stool scale score (mean ± SD) | 3.5 ± 1.7 | 3.8 ± 1.2 | 0.561 |

Composition of the Gut Microbiome of Control and AD Groups

Sequencing of the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene generated a total of 4.8 million sequence reads (mean ± SD: ~96,000 ± 32,000 reads/participant), which were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% similarity and assigned taxonomic classifications down to the lowest phylogenetic level possible (see Methods). The final OTU dataset for AD and Control groups consisted of 972 OTUs classified to 95 genera, 46 families, 24 orders, 17 classes, and 9 phyla. Between groups, there were no differences in percentages of sequences classified to the phylum (Control: 99.6 ± 0.5%, AD: 99.6 ± 0.9%) or genus level (Control: 79.6 ± 7.4%, AD: 83.1 ± 8.1%). Across all 50 participants, the dominant phyla were Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, which respectively made up 78% (78.1 ± 8.7%) and 15% (14.9 ± 8.4%) of total abundance, with lower contributions from Actinobacteria (2.6%), Verrucomicrobia (2.6%), and Proteobacteria (1.1%) (Supplementary Fig. S1). The predominant bacterial families for all participants were Lachnospiraceae (39.1%), Ruminococcaceae (29.6%), and Bacteroidaceae (9.8%), followed by Verrucomicrobiaceae (2.6%), Clostridiales (1.9%), and Bifidobacteriaceae (1.5%) (Supplementary Fig. S1).

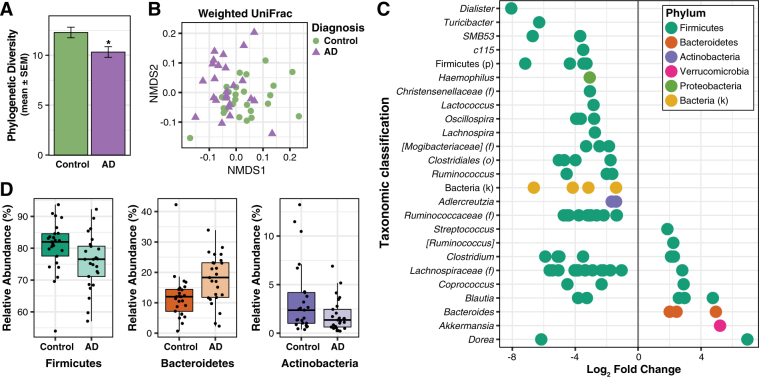

AD is Associated with Changes in the Gut Microbiome

The composition of the gut microbiome was characterized using traditional ecological measures including richness (the number of unique OTUs present in a participant), alpha diversity (the richness and abundance of OTUs within each participant), and beta diversity (the similarity or difference in composition between participants). For microbiome richness estimates, we used the Abundance-based coverage estimator (ACE) and Chao1; these metrics use non-parametric modeling to calculate a conservative estimate of total OTU richness for each participant. The microbiome of AD participants had reduced richness, with both ACE and Chao1 significantly decreased in the AD group compared to the Control group (t-test; ACE: DF = 48, t = 3.05, p = 0.004; Chao1: DF = 48, t = 2.98, p = 0.004) (Supplementary Fig. S2). For alpha diversity metrics, we used the Inverse Simpson and Shannon Indexes, and Faith’s Phylogenetic Diversity (PD), an alpha diversity metric that also incorporates phylogenetic relationships. While there was a trend towards a decrease in the Inverse Simpson Index between Control and AD groups (Mann-Whitney; U = 227.0, p = 0.097), both the Shannon Index and Faith’s PD were significantly decreased in AD participants compared to Control participants (t-test; Shannon: DF = 48, t = 2.44, p = 0.019, PD: DF = 48, t = 2.59, p = 0.013) (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Fig. S2). With respect to beta diversity, Bray-Curtis dissimilarity and UniFrac analysis (weighted and unweighted) demonstrated compositional differences in the microbiome between AD and Control groups (PERMANOVA, Bray-Curtis: F = 2.87, p < 0.001, weighted UniFrac: F = 3.84, p < 0.001; unweighted UniFrac: F = 2.60, p < 0.005) (Fig. 1B, Supplementary Fig. S3).

Figure 1.

Alzheimer’s disease is associated with alterations in gut microbiome composition. (A) Faith’s Phylogenetic Diversity is decreased in the microbiome of AD participants. *p < 0.05. (B) Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plot of weighted UniFrac analysis of relative sample OTU composition. NMDS analysis was limited to two dimensions, with a stress measurement of 0.17. Each dot represents a scaled measure of the composition of a given participant, color- and shape-coded by cohort. (C) Differential abundance analysis identified 14 OTUs that were increased and 68 OTUs that were decreased in AD relative to Control participants (p < 0.05, FDR-corrected). Each point represents an OTU. Data plotted as log2 fold change; OTUs to the right of the zero line are more abundant and OTUs to the left of the zero line are less abundant in AD compared to Control groups. OTUs are organized on the y-axis according to the lowest taxonomic classification possible. (D) OTUs grouped at the phylum level and analyzed using Metastats show that AD participants have decreased abundance of Firmicutes and Actinobacteria, and increased abundance of Bacteroidetes compared to Control participants (p < 0.05, FDR-corrected). Tukey plots show median, IQR, and participant data points for phylum relative abundance.

Differential abundance analysis of taxa at the OTU level revealed that the microbiome of AD participants showed significantly altered abundance of 82 OTUs relative to the Control group, with 14 OTUs more abundant and 68 OTUs less abundant in AD (Fig. 1C, Supplementary Table S2). Plotting these 82 OTUs as a phylogenetic tree-ordered and diagnosis-grouped heat map shows clear differences in OTU abundance distributions between Control and AD groups (Supplementary Fig. S4).

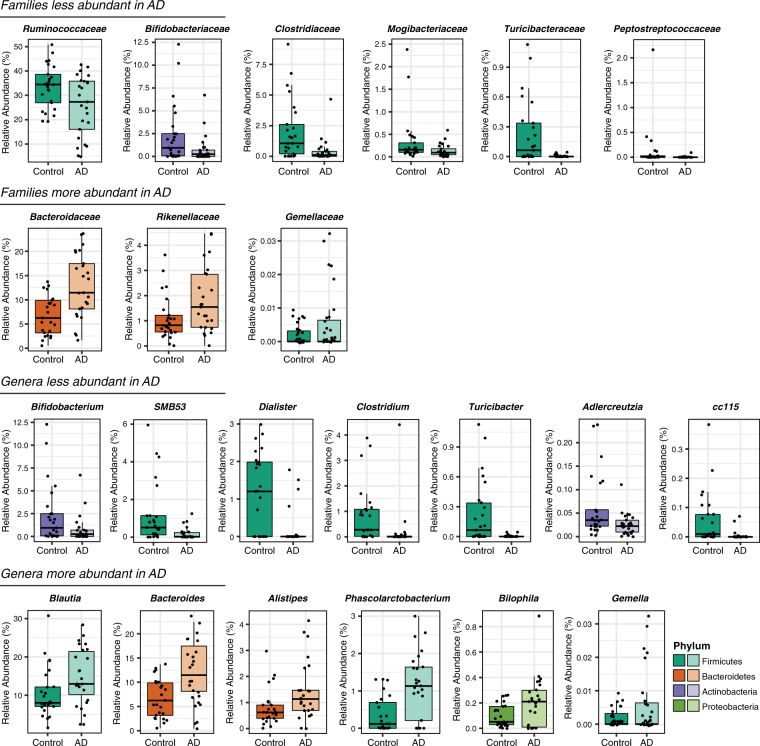

OTUs were taxonomically grouped and differential abundance was analyzed at the phylum, family, and genus levels using Metastats (Supplementary Table S3). At the phylum level, AD participants had decreased abundance of Firmicutes and Actinobacteria, and increased abundance of Bacteroidetes compared to Control participants (Fig. 1D). Within Firmicutes, the families Ruminococcaceae, Turicibacteraceae, Peptostreptococcaceae, Clostridiaceae, and Mogibacteriaceae, and the genera SMB53 (family Clostridiaceae), Dialister, Clostridium, Turicibacter, and cc115 (family Erysipelotrichaceae) were all less abundant in AD participants, while the family Gemellaceae and the genera Blautia, Phascolarctobacterium, and Gemella were more abundant in AD participants (Fig. 2). Within Bacteroidetes, Bacteroidaceae and Rikenellaceae at the family level, and Bacteroides and Alistipes at the genus level were more abundant in AD participants. The decrease in Actinobacteria was reflected by decreased Bifidobacteriaceae at the family level and by decreased Bifidobacterium and Adlercreutzia at the genus level. Additionally, the genus Bilophila in the phylum Proteobacteria was more abundant in AD participants.

Figure 2.

Bacterial families and genera differentially represented in feces from AD participants compared to Control participants (p < 0.05, FDR-corrected). Tukey plots are colored by phylum and show median, IQR, and participant data points for genus or family relative abundance.

Predictive metagenomics analysis (PICRUSt18) identified potential functional changes in the gut microbiome of AD participants. These include increases in predicted gene content in KEGG pathways related to metabolism and biosynthesis, including oxidative phosphorylation, carbohydrate metabolism, and amino acid metabolism (Supplementary Fig. S5), and decreases in predicted gene content in KEGG pathways related to signal transduction and cell motility, including bacterial chemotaxis pathways, secretion systems, bacterial motility proteins, and two-component signal transduction systems.

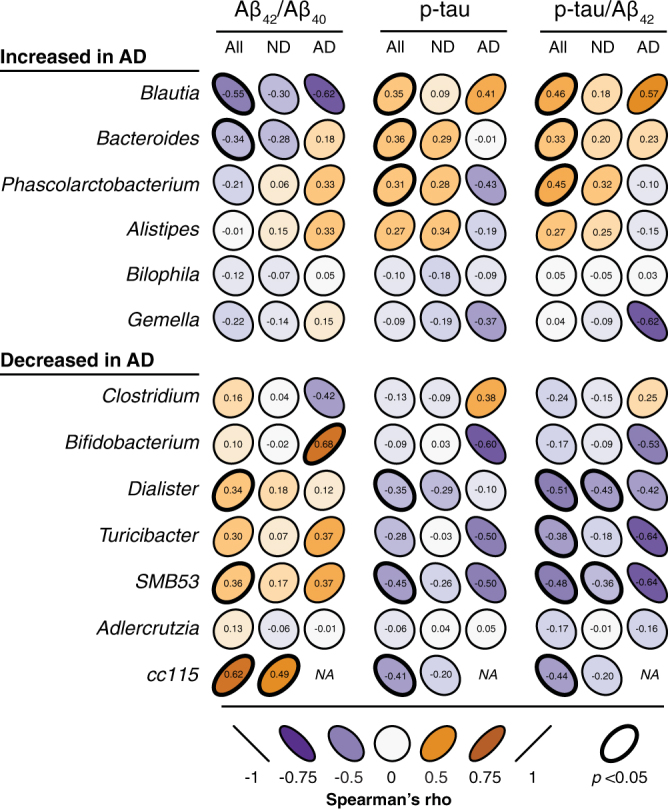

Differentially Abundant Genera Are Correlated with CSF Biomarkers of AD Pathology

Our primary microbiome compositional analysis identified 13 genera as differentially abundant between AD and Control groups. We next examined the relationship between the relative abundance of these 13 taxa and levels of CSF biomarkers in a subset of participants who had also undergone lumbar puncture. This analysis included microbiome and CSF data from 9 AD group participants, and 31 non-demented (ND) participants (10 from the Control group, and an additional 21 largely younger participants not selected in the original random matching with AD participants). Correlations were calculated using data from the total group of 40 participants, as well as separately for ND participants and AD participants. CSF biomarkers included Aβ42/Aβ40, phosphorylated tau (p-tau), the ratio of p-tau/Aβ42, and chitinase-3-like protein 1 (YKL-40). CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 is an indicator of amyloid burden, with lower levels in the CSF reflecting greater amyloid deposition in the brain; p-tau is a marker of neurofibrillary tangles, with higher levels reflecting greater tangle pathology in the brain; the ratio of p-tau/Aβ42 incorporates both aspects of pathology, with higher values implying greater AD pathology19. YKL-40 is a marker of astroglial and/or microglial activation, and has been shown to be elevated in CSF of individuals with dementia due to AD20–22. Supplementary Table S4 reports participant characteristics, CSF biomarker levels, and relative abundances of genera.

Across all 40 participants included in this analysis, we observed generally consistent trends between bacterial relative abundance and CSF biomarkers of AD pathology (Fig. 3). The direction of these trends was largely similar for both AD participants and healthy non-demented participants. For genera that are more abundant in AD, we observed a relationship between increased bacterial abundance and greater AD pathology, which was indicated by predominantly negative correlations between bacterial abundance and CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 (suggesting greater abundance is associated with greater amyloid burden in the brain), and predominantly positive correlations between bacterial abundance and CSF p-tau and p-tau/Aβ42. These relationships were especially strong in those genera with overall greater relative abundance, particularly in Bacteroides and Blautia. Similarly, for those genera that are less abundant in AD, we observed a relationship between decreased bacterial abundance and greater AD pathology, with levels of SMB53 and Dialister showing the strongest correlations with CSF AD biomarkers. Notably, in both more and less abundant genera, the strongest correlations between bacterial abundance and CSF AD biomarkers were in the same direction whether including only AD participants, only healthy non-demented participants, or all participants. Additionally, in AD participants, we observed a relationship between increased abundance of Bacteroides and increased CSF YKL-40 levels, and a relationship between decreased abundance of both Turicibacter and SMB53 and increased CSF YKL-40 levels (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Figure 3.

Bacterial taxa correlate with CSF biomarkers of AD pathology. 13 genera identified as differentially abundant in AD were correlated with CSF biomarkers of AD including the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio (with lower CSF levels reflecting greater amyloid deposition in the brain), phosphorylated tau (p-tau), and the p-tau/Aβ42 ratio (which incorporates both facets of AD pathology). Correlations were calculated separately for all 40 participants (All), 31 non-demented participants (ND), and 9 AD participants (AD). In general, genera identified as more abundant in AD were associated with greater AD pathology, while genera identified as less abundant in AD were associated with less AD pathology. Genera are ordered from most to least abundant. Shape and color of ellipses represent strength of Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (rho). Bolded ellipse borders represent significant correlations (two-sided, p < 0.05 uncorrected).

Discussion

Despite the proposed role of gut microbiota in the development or progression of AD4,5,23, there have been no comprehensive surveys of the gut microbiome in individuals with AD. In this study, we performed bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequencing on DNA isolated from fecal samples in order to compare the composition of the gut microbiome in participants with and without a diagnosis of dementia due to AD. We discovered that the gut microbiome of AD participants has decreased microbial richness and diversity and a distinct composition compared to asymptomatic age- and sex-matched Control participants. We also identified several broad taxonomic differences between AD and Control groups, and determined that levels of differentially abundant genera correlate with CSF biomarkers of AD pathology.

The decreased richness and diversity in our study broadly parallels results observed in other conditions linked to gut microbiome alterations, including obesity, diabetes, IBD, and Parkinson’s disease13,24–26. Furthermore, PICRUst analysis revealed broad functional changes in predicted metabolism, bacterial cell motility, and signal transduction pathways in the gut microbiome of AD participants. While the specific bacteria responsible for these compositional and functional alterations may differ between conditions, it has been proposed that these broad-scale changes in gut microbiota (often referred to as “dysbiosis”) may play important roles in disease progression and maintenance, potentially through immune activation and systemic inflammation27. While it is unclear how the gut influences the development of neuropathology, substantial evidence supports the existence of a gut-brain axis that allows bi-directional communication between the gut and brain through several pathways including neural, endocrine, and immune mechanisms11,28. Within this framework, alterations in gut microbial communities in patients with AD may result in pathophysiological changes in the brain. In support of this hypothesis, a recent study showed that transgenic AD mice raised under germ-free conditions have less cerebral amyloid deposition than conventionally-raised AD mice, indicating that gut microbiota influence the development of amyloid pathology16.

In our study, the phylum Firmicutes as a whole, as well as several families, genera, and 61 OTUs classified within Firmicutes were decreased in the AD group. A reduction in Firmicutes has been reported in the microbiome of individuals with type 2 diabetes25 as well as obesity29 (although others have reported increased Firmicutes in obesity24,30). Notably, diabetes and insulin resistance increase the risk of developing AD31–33. We have recently reported that insulin resistance is associated with decreased cerebral glucose metabolism and increased amyloid deposition in asymptomatic middle-aged adults enriched for risk of AD34,35. Thus, a potential mechanism by which microbial alterations in the gut may influence AD pathology is through promoting the development of insulin resistance and diabetes. While AD and Control groups did not differ with respect to diabetes prevalence (Table 1), sub-clinical differences in insulin or glucose metabolism cannot be ruled out. Further investigation will be needed to explore the relationship between microbiota and insulin resistance in AD.

In participants with AD, we observed an increase in the phylum Bacteroidetes, which was reflected by increased Bacteroidaceae at the family level, and increased Bacteroides at the OTU and genus level. The phylum Bacteroidetes encompasses a diverse and abundant group of gram-negative commensal bacteria in the gut36, including the genus Bacteroides, which has been detected at higher levels in the gut of individuals with type 2 diabetes25 and in patients with Parkinson’s disease13, a neurodegenerative disorder. The major outer membrane component of gram-negative bacteria is lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which is capable of triggering systemic inflammation and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines after translocation from the gut to systemic circulation37. Additionally, in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated an association between bacterial endotoxins (e.g. LPS) and AD pathology. Co-incubation of Aβ peptide with LPS potentiates amyloid fibrillogenesis38, and systemic injection of LPS in wild-type and transgenic AD mice results in greater amyloid deposition and tau pathology39–42. In humans, intestinal permeability increases with age43, and elderly individuals show an association between increased LPS-binding protein (a marker of microbial translocation) and inflammation44. Moreover, a recent study involving postmortem brain tissue from patients with AD showed that LPS and gram-negative E. coli fragments co-localize with amyloid plaques45. Thus, increased abundance of gram-negative intestinal bacteria such as Bacteroides in participants with AD may result in increased translocation of LPS from the gut to systemic circulation, which in turn may contribute to or exacerbate AD pathology through inflammation or other mechanisms.

Additionally, compared to control participants, AD participants in our study exhibited decreased Actinobacteria. These differences were mostly driven by changes in Bifidobacterium. Actinobacteria, particularly members of the Bifidobacterium genus, are an important bacterial inhabitant of the human gut across the lifespan, and their beneficial health effects have been well-documented46,47. In particular, certain species of Bifidobacterium are associated with anti-inflammatory properties and decreased intestinal permeability48. Additionally, supplementation with Bifidobacterium has been shown to decrease LPS levels in the intestine and improve gut mucosal barrier properties in mice49,50. Interestingly, in germ-free mice colonized with human gut microbiota, increased levels of Bifidobacterium are associated with decreased bacterial translocation to systemic circulation, while increased levels of Bacteroides have been shown to increase bacterial translocation51. Considering our present findings, increased Bacteroides and decreased Bifidobacterium in AD participants may represent a gut microbial phenotype with particular propensity for translocation of pro-inflammatory bacterial components. Furthermore, several Bifidobacterium species are widely used as probiotics. A small study of probiotics that included Bifidobacterium demonstrated a change in Mini-Mental State Examination scores after a 12-week intervention among participants with severe dementia52. Taken together with the decreased abundance of Bifidobacterium in AD participants observed in our study, larger trials may be warranted, particularly in earlier disease stages.

Finally, we observed correlations between levels of differentially abundant gut microbiota and CSF biomarkers of AD pathology in a subset of participants that had also undergone lumbar puncture. In general, genera identified as more abundant in AD were associated with greater AD pathology while genera identified as less abundant in AD were associated with less AD pathology. These effects were most prominent when examining CSF p-tau/Aβ42, a composite measure of AD pathology. Interestingly, even among non-demented participants who had undergone lumbar puncture, we found a relationship between genera that were either more or less abundant in AD and markers of amyloid and tau protein, even in the absence of dementia. In particular, Dialister and SMB53 showed the strongest correlations in non-demented participants, with greater abundance of these bacteria associated with less AD pathology, suggesting these bacterial taxa may be protective against development or progression of AD pathology. We also observed significant associations in AD participants between CSF YKL-40 and abundance of Bacteroides, Turicibacter, and SMB53 (family Clostridiaceae). While these findings support a link between altered gut bacterial abundance and glial activation in AD, this relationship is less clear in healthy non-demented individuals and requires further investigation.

A limited number of studies have attempted to address the role of gut microbiota in AD. A recent investigation in cognitively-impaired older adults (without an AD diagnosis) reported increased abundance of the pro-inflammatory bacteria Escherichia/Shigella and decreased abundance of the anti-inflammatory bacteria Eubacterium rectale in individuals with evidence of amyloid deposition on PET imaging compared to individuals who were amyloid negative14. While those results support a link between gut microbiota and brain amyloidosis, the study only investigated the abundance of six pre-selected bacterial taxa using quantitative PCR rather than the broader approach used here. Additionally, in a recent AD mouse microbiome study using 16S rRNA sequencing, APP/PS1 transgenic mice showed increased Helicobacteraceae and Desulfovibrionaceae at the family level, increased Odoribacter and Helicobacter, and decreased Prevotella compared to wild-type mice53. However, while the anatomy and physiology of the gastrointestinal tract of humans and mice share many characteristics54, there are also substantial differences with respect to resident bacterial communities30, which makes comparing taxa and changes in abundance between these studies difficult.

While AD participants were well-matched to our Control participants (suggesting that the gut microbiome differences we observed were not likely the result of age, sex, BMI, or dietary differences between groups), they did differ with respect to the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and AD medications. We did not find differences in microbial richness, diversity, or relative abundance of the 13 genera identified as altered in AD between AD participants taking SSRIs and AD participants not taking SSRIs (Supplementary Table S5), suggesting that these medications are not influencing our results. Nearly all AD participants in our study were taking the AD medications donepezil or rivastigmine (acetylcholinesterase inhibitors), and/or memantine (an NMDA receptor antagonist). It is unknown how these medications affect the gut microbiome. The most common side effects reported for acetylcholine esterase inhibitors are gastrointestinal upset55, both nausea and diarrhea, which could influence microbiota composition. It is worth noting that our participants did not report chronic constipation or diarrhea, and there was no difference between groups on the Bristol stool scale (Table 1), which can be used as a surrogate for stool transit time. Still, we recognize that we cannot completely rule out the effect of AD medication use on our results. Further work, including animal experiments and longitudinal human studies, will be needed to determine the cause-effect relationship between gut microbiota and pathogenesis of AD. Determining the role of gut bacteria in the progression or maintenance of AD may lead to novel interventional approaches that alter or restore healthy gut bacterial composition, or identification of microbial metabolites that are protective against AD.

Methods

Participants

Participants with dementia due to AD (n = 25) were recruited from the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC). Non-demented participants (n = 94) were recruited from both the ADRC and the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention (WRAP) study56. The University of Wisconsin Health Science Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures, and all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants provided written informed consent to be involved in this study.

Exclusion criteria for this study included any significant neurologic disease, history of alcohol/substance dependence, major psychiatric disorders (including major depression), or any other significant medical illness. Microbiome-specific exclusion criteria included: the use of systemic antibiotics in the previous 6 months prior to providing the fecal sample; corticosteroid use (oral, IV, nasal, or inhaled); immune stimulating medications; immunosuppressive agents; large doses of commercial probiotics consumed (greater than or equal to 108 cfu or organisms per day); major dietary change during previous month (defined as eliminating or significantly increasing a major food group); major GI tract surgery in past 5 years (with the exception of cholecystectomy and appendectomy); major bowel resection at any time; active uncontrolled GI disorders or diseases including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), indeterminate colitis, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), persistent, infectious gastroenteritis, colitis or gastritis, persistent or chronic diarrhea of unknown etiology, Clostridium difficile infection (recurrent) or Helicobacter pylori infection (untreated), or chronic constipation.

At the time of fecal sample collection, participants completed a short questionnaire regarding recent antibiotic or probiotic use, as well as current and past gastrointestinal/metabolic conditions. Additionally, participants also completed a 15-item self-report diet questionnaire developed by Martha Clare Morris (Rush University) and based on the MIND Diet17, which allowed us to assess dietary differences between groups. We also used information/data collected from participants at annual and bi-annual ADRC and WRAP study visits including medication use, medical conditions/diagnoses, clinical dementia rating (CDR) scores, and CSF biomarker data (see below). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the height and weight of each participant at their most recent ADRC or WRAP study visit. APOE ε4 genotyping procedures have been described previously57, and participants were categorized as non-carriers (zero ε4 alleles) or APOE ε4 carriers (one or two ε4 alleles). Participants with AD were diagnosed using the NINDS/ADRDA criteria58, and confirmed by a multidisciplinary consensus diagnostic panel.

Of the 119 participants recruited, six non-demented participants were excluded from analyses due to antibiotic or probiotic use at the time of fecal sample collection that was not reported during initial screening. Participants recruited from the WRAP study were largely younger than those recruited from the ADRC, thus for our primary compositional analysis we age- and sex-matched the 25 AD participants 1-to-1 from the remaining 88 asymptomatic control participants using case-control matching in SPSS with an age tolerance of 4.5 years to create an equal-sized Control group. For secondary CSF correlational analysis, we used microbiome and CSF data from 9 AD cohort participants, and 31 non-demented (ND) participants, including 10 from the age- and sex-matched Control cohort, and an additional 21 largely younger participants not included in the primary analysis.

Fecal sample collection and bacterial 16S rRNA sequencing and processing

All participants involved in the study resided at home, where fecal sample collection occurred. Participants returned by overnight delivery sample collection kits, packaged within insulated containers and chilled with frozen gel packs; all samples included in this study arrived chilled and 92% were processed and frozen (see below) the day following home collection by an individual who was blind to the participant’s cohort/diagnosis. Upon receipt, chilled samples were weighed, scored on the Bristol stool scale59, subsampled (~100 mg) into prepared sterile bead beating tubes, and stored at −80 °C until processing.

Fecal samples, suspended in lysis buffer/phenol:chloroform, were processed by bead beating24 and the genomic DNA in the recovered aqueous phase then precipitated with the addition of 0.1-volume 3 M sodium acetate and 1-volume isopropanol, incubated on ice, and centrifuged (4 °C, 20 min at 18,000 x g). After rinsing with 100% ethanol and drying, the DNA pellet was dissolved in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA) then column-purified using the NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up kit (Macherey-Nagel Inc., Bethlehem, PA). DNA concentration was measured using the Qubit BR dsDNA assay (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR). The variable region V4 amplicon of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified in duplicate reactions/sample (plus a no-template control for each primer set) using 8-bp barcoded forward and reverse primers (0.4 μM)60, 12.5 ng template, and KAPA HiFi HotStart DNA polymerase (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA). Reactions were agarose gel-checked and duplicates combined, purified (NucleoSpin columns), and the DNA quantified (Qubit). The final equimolar pool was sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq platform (paired end, 2 × 250-bp).

Sequence processing and cleanup was performed using mothur v1.39.161 and a previously described prototcol60. Briefly, quality-filtered, paired-end duplex sequence reads were combined into contigs, and sequences with ambiguous base pairings, sequences longer that 275-bp, and homopolymers greater than 8-bp were removed. Sequences were then aligned to the SILVA 16S rRNA gene reference alignment database, and chimeric sequences were identified and removed. Finally, remaining sequences with 97% similarity were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using the OptiClust algorithm62 and assigned the lowest possible taxonomic classifications from the GreenGenes reference database (v13.8) using a naive Bayesian classifier requiring an 80% confidence score. As it has been demonstrated that quality-filtering 16S amplicon sequence reads can greatly improve accuracy of microbial community analysis63, OTUs with <0.001% of total sequence reads were filtered out from the dataset to account for sequencing errors.

Microbial community composition and differential abundance statistical analysis

Richness (ACE, Chao1) and alpha diversity (Inverse Simpson, Shannon Index) metrics were calculated at the OTU-level in mothur by performing 1000 iterations of random subsampling to 31,396 reads (the lowest single participant number of sequences) from each participant. Faith’s Phylogenetic Diversity (PD) was calculated from a neighbor-joined phylogenetic tree created in R v3.3.2 using normalized OTU-level data and the vegan, phyloseq, and ape packages. Beta diversity metrics were computed using normalized OTU-level data in R and included Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, and weighted and unweighted UniFrac. To detect differences in richness and alpha diversity between groups, we used independent two-sample t-tests for normally distributed measures or Mann-Whitney U tests for non-normally distributed measures in SPSS. To detect statistical differences in beta diversity metrics between groups, we used permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) in the vegan package in R.

Differential abundance of taxa between AD and Control groups was determined at the OTU level using the DESeq2 package in R. DESeq2 is a statistical method developed to detect differential expression in RNA-seq count data while accounting for library size differences and biological variability64. It has recently been demonstrated that applying these methods to microbiome OTU count data leads to improvements in detecting differential abundance compared to simple proportions or rarefying65. Results were expressed as log2 fold change in AD participants relative to Control participants. Relative abundance comparisons at the genus, family, and phylum levels were performed on normalized data in mothur using 10,000 iterations of Metastats, a statistical method employing non-parametric t-tests, Fisher’s exact tests, and false discovery rate (FDR) correction to detect differentially abundant features66. OTUs present in less than 20 participants and those OTUs that could not be classified down to the desired level were excluded from the Metastats analysis.

PICRUSt predictive functional metagenomics analysis

We used PICRUSt18 to detect predicted functional differences in microbial communities between AD and Control participants. Briefly, OTUs were re-assigned PICRUSt-compatible taxonomic classifications using the GreenGenes version 13.5 reference database, and then normalized by 16S rRNA copy number. The resulting normalized OTU table was then used for prediction of KEGG orthologs (KOs) based on bacterial composition. The weighted nearest sequenced taxon index (NSTI), a quality metric of the phylogenetic distance between the input OTUs of our samples and the reference OTUs used for metagenomic prediction, was 0.07 ± 0.01 (mean ± SD) for our samples. KOs were collapsed into hierarchical KEGG pathways using the categorize by function command in PICRUSt, and the linear discriminate analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe)67 implementation in mothur was used to detect differences in level 2 and level 3 KEGG pathways. LDA scores (log 10) of significantly different pathways were plotted as bars using ggplot2 in R.

CSF collection and microbiome correlation statistical analysis

CSF was collected via lumbar puncture in the morning after a 12hr fast with a Sprotte 25-or 24-gauge spinal needle at the L3/4 or L4/5 interspace using gentle extraction into propylene syringes. CSF (~22 mL) was then combined, gently mixed and centrifuged at 2,000 x g for 10 minutes. Supernatants were frozen in 0.5 mL aliquots in polypropylene tubes and stored at −80 °C.

CSF measures included the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio, phosphorylated tau (p-tau), and the p-tau/Aβ42 ratio. Using the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio normalizes CSF Aβ42 for the total amount of Aβ peptides that are present in CSF and shows better correspondence with brain amyloid deposition as well as superior diagnostic performance than CSF Aβ42 alone68. For the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio, CSF Aβ42 and CSF Aβ40 were quantified separately by electrochemiluminescence (ECL) using an Aβ triplex assay (MSD Human Aβ peptide Ultra-Sensitive Kit, Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD). For p-tau and the p-tau/Aβ42 ratio, CSF P-tau and Aβ42 were quantified using commercially available sandwich ELISAs (INNOTEST β-amyloid1–42, and Phospho-Tau[181 P], respectively; Fujirebio Europe, Ghent, Belgium). YKL-40 was quantified using sandwich ELISAs (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn., USA). CSF assays were performed in two batches and corrected for batch differences as previously described69,70. For correlational statistical analysis, we used the “cor.test” function in R to calculate Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients between CSF biomarker levels and normalized relative abundances for the 13 differentially abundant genera. The correlation matrix was plotted as ellipses using the ellipse package in R.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a University of Wisconsin Institute for Clinical and Translational Research pilot grant awarded to F.E.R. and B.B.B. as part of the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) [UL1TR000427], NIH P50 AG033514 (S.A.), and R01 AG027161 (S.C.J.), R01 AG021155 (S.C.J.), R01 AG037639 (B.B.B.), the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Alzheimer’s Association, the Swedish Brain Foundation, and Torsten Söderberg Foundation at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. We would like to thank Martha Clare Morris at Rush University for sharing her 15-item diet questionnaire, Matthew Beilfuss and Lauren Koenig for assistance with study logistics, participant recruitment and screening, and Andrew J. Steinberger for assistance with sample preparation. Finally, we extend thanks to our committed research participants who made this research possible.

Author Contributions

F.E.R., B.B.B., C.M.C., S.A. and S.C.J. contributed to study concept and experimental design. N.M.V., R.L.K., K.A.D., S.J.H., A.P.M., C.M.C., H.Z., K.B., B.B.B., and F.E.R. participated in data acquisition, analysis, or interpretation. N.M.V., B.B.B., and F.E.R. drafted the manuscript. R.L.K., K.A.D., A.P.M., S.J.H., S.C.J., C.M.C., H.Z., K.B., and S.A. provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-13601-y.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Barbara B. Bendlin, Email: bbb@medicine.wisc.edu

Federico E. Rey, Email: ferey@wisc.edu

References

- 1.Selkoe DJ, Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016;8:595–608. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill JM, et al. Pathogenic microbes, the microbiome, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) Front. Aging. Neurosci. 2014;6:1–5. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao Y, Dua P, Lukiw WJ. Microbial sources of amyloid and relevance to amyloidogenesis and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) J. Alzheimers Dis. Parkinsonism. 2015;5:177. doi: 10.4172/2161-0460.1000177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhattacharjee S, Lukiw WJ. Alzheimer’s disease and the microbiome. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2013;7:1–4. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghaisas S, Maher J, Kanthasamy A. Gut microbiome in health and disease: Linking the microbiome-gut-brain axis and environmental factors in the pathogenesis of systemic and neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016;158:52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chow J, Lee SM, Shen Y, Khosravi A, Mazmanian SK. Host-bacterial symbiosis in health and disease. Adv. Immunol. 2010;107:243–274. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381300-8.00008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koenig JE, et al. Succession of microbial consortia in the developing infant gut microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4578–4585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000081107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Human Microbiome Project Consortium Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claesson MJ, et al. Composition, variability, and temporal stability of the intestinal microbiota of the elderly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4586–4591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000097107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clemente JC, Ursell LK, Parfrey LW, Knight R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: an integrative view. Cell. 2012;148:1258–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fung TC, Olson CA, Hsiao EY. Interactions between the microbiota, immune and nervous systems in health and disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2017;20:145–155. doi: 10.1038/nn.4476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheperjans F, et al. Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson’s disease and clinical phenotype. Mov. Disord. 2015;30:350–358. doi: 10.1002/mds.26069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keshavarzian A, et al. Colonic bacterial composition in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2015;30:1351–1360. doi: 10.1002/mds.26307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cattaneo A, et al. Association of brain amyloidosis with pro-inflammatory gut bacterial taxa and peripheral inflammation markers in cognitively impaired elderly. Neurobiol. Aging. 2017;49:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minter MR, et al. Antibiotic-induced perturbations in gut microbial diversity influences neuro-inflammation and amyloidosis in a murine model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–12. doi: 10.1038/srep30028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harach T, et al. Reduction of Abeta amyloid pathology in APPPS1 transgenic mice in the absence of gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:41802. doi: 10.1038/srep41802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris MC, et al. MIND diet associated with reduced incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:1007–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langille MGI, et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:814–821. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blennow K, Zetterberg H. The past and the future of Alzheimer’s disease CSFbiomarkers - a journey toward validated biochemical tests covering the whole spectrum of molecular events. Front. Neurosci. 2015;9:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hellwig K, et al. Neurogranin and YKL-40: independent markers of synaptic degeneration and neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Alz. Res. Therapy. 2015;7:74. doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0161-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craig-Schapiro R, et al. YKL-40: a novel prognostic fluid biomarker for preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;68:903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosén C, et al. Increased Levels of Chitotriosidase and YKL-40 in Cerebrospinal Fluid from Patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Dis. Extra. 2014;4:297–304. doi: 10.1159/000362164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pistollato F, et al. Role of gut microbiota and nutrients in amyloid formation and pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease. Nutr. Rev. 2016;74:624–634. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuw023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turnbaugh PJ, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–484. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larsen N, et al. Gut microbiota in human adults with type 2 diabetes differs from non-diabetic adults. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dicksved J, et al. Molecular analysis of the gut microbiota of identical twins with Crohn’s disease. ISME J. 2008;2:716–727. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DuPont AW, DuPont HL. The intestinal microbiota and chronic disorders of the gut. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011;8:523–531. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012;13:701–712. doi: 10.1038/nrn3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwiertz A, et al. Microbiota and SCFA in lean and overweight healthy subjects. Obesity. 2009;18:190–195. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ley RE, et al. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:11070–11075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504978102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rawlings AM, et al. Diabetes in midlife and cognitive change over 20 years: a cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014;161:785–793. doi: 10.7326/M14-0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ott A, et al. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of dementia: The Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 1999;53:1937–1942. doi: 10.1212/WNL.53.9.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.la Monte de SM, Wands JR. Review of insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression, signaling, and malfunction in the central nervous system: relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2005;7:45–61. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2005-7106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Willette AA, et al. Association of insulin resistance with cerebral glucose uptake in late middle-aged adults at risk for Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:1013–1020. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.0613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willette AA, et al. Insulin resistance predicts brain amyloid deposition in late middle-aged adults. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:504–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajilić-Stojanović M, de Vos WM. The first 1000 cultured species of the human gastrointestinal microbiota. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014;38:996–1047. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cani PD, et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:1761–1772. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asti A, Gioglio L. Can a bacterial endotoxin be a key factor in the kinetics of amyloid fibril formation? J. Alzheimers Dis. 2014;39:169–179. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheng JG, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced-neuroinflammation increases intracellular accumulation of amyloid precursor protein and amyloid beta peptide in APPswe transgenic mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2003;14:133–145. doi: 10.1016/S0969-9961(03)00069-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kahn MS, et al. Prolonged elevation in hippocampal Aβ and cognitive deficits following repeated endotoxin exposure in the mouse. Behav. Brain. Res. 2012;229:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kitazawa M, Oddo S, Yamasaki TR, Green KN, LaFerla FM. Lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation exacerbates tau pathology by a cyclin-dependent kinase 5-mediated pathway in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:8843–8853. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2868-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sy M, et al. Inflammation induced by infection potentiates tau pathological features in transgenic mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2011;178:2811–2822. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Man AL, et al. Age-associated modifications of intestinal permeability and innate immunity in human small intestine. Clin. Sci. 2015;129:515–527. doi: 10.1042/CS20150046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stehle JR, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein, a surrogate marker of microbial translocation, is associated with physical function in healthy older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. A-Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2012;67:1212–1218. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhan X, et al. Gram-negative bacterial molecules associate with Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology. 2016;87:2324–2332. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Callaghan A, van Sinderen D. Bifidobacteria and their role as members of the human gut microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1–23. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arboleya S, Watkins C, Stanton C, Ross RP. Gut bifidobacteria populations in human health and aging. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Underwood MA, German JB, Lebrilla CB, Mills DA. Bifidobacterium longum subspecies infantis: champion colonizer of the infant gut. Pediatr. Res. 2015;77:229–235. doi: 10.1038/pr.2014.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Z, et al. The role of bifidobacteria in gut barrier function after thermal injury in rats. J. Trauma. 2006;61:650–657. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196574.70614.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Griffiths EA, et al. In vivo effects of bifidobacteria and lactoferrin on gut endotoxin concentration and mucosal immunity in Balb/c mice. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2004;49:579–589. doi: 10.1023/B:DDAS.0000026302.92898.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Romond M-B, et al. Does the intestinal bifidobacterial colonisation affect bacterial translocation? Anaerobe. 2008;14:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Akbari E, et al. Effect of probiotic supplementation on cognitive function and metabolic status in Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized, double-blind and controlled trial. Front. Aging. Neurosci. 2016;8:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shen L, Liu L, Ji H-F. Alzheimer’s disease histological and behavioral manifestations in transgenic mice correlate with specific gut microbiome state. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017;56:385–390. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nguyen TLA, Vieira-Silva S, Liston A, Raes J. How informative is the mouse for human gut microbiota research? Dis. Model. Mech. 2015;8:1–16. doi: 10.1242/dmm.017400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hansen RA, et al. Efficacy and safety of donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Interv. Aging. 2008;3:211–225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sager MA, Hermann B, La Rue A. Middle-aged children of persons with Alzheimer’s disease: APOE genotypes and cognitive function in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2005;18:245–249. doi: 10.1177/0891988705281882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johnson SC, et al. The effect of TOMM40 poly-T length on gray matter volume and cognition in middle-aged persons with APOE ε3/ε3 genotype. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:456–465. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McKhann GM, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1997;32:920–924. doi: 10.3109/00365529709011203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kozich JJ, Westcott SL, Baxter NT, Highlander SK, Schloss PD. Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;79:5112–5120. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01043-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schloss PD, et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:7537–7541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Westcott SL, Schloss PD. OptiClust, an improved method for assigning amplicon-based sequence data to operational taxonomic units. mSphere. 2017;2:1–11. doi: 10.1128/mSphereDirect.00073-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bokulich NA, et al. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:57–59. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq. 2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:31–21. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. Waste not, want not: why rarefying microbiome data is inadmissible. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.White JR, Nagarajan N, Pop M. Statistical methods for detecting differentially abundant features in clinical metagenomic samples. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009;5:1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Segata N, et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12(R60):1–18. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lewczuk P, Lelental N, Spitzer P, Maler JM, Kornhuber J. Amyloid-β 42/40 cerebrospinal fluid concentration ratio in the diagnostics of Alzheimer’s disease: validation of two novel assays. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43:183–191. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Racine AM, et al. Associations between performance on an abbreviated CogState battery, other measures of cognitive function, and biomarkers in people at risk for Alzheimer’s sisease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016;54:1395–1408. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Racine AM, et al. Association of longitudinal white matter degeneration and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of neurodegeneration, inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease in late-middle-aged adults. Brain Imaging Behav. 2017;59:306. doi: 10.1007/s11682-017-9732-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.