ABSTRACT

In the foodborne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes, arsenic resistance is encountered primarily in serotype 4b clones considered to have enhanced virulence and is associated with an arsenic resistance gene cluster within a 35-kb chromosomal region, Listeria genomic island 2 (LGI2). LGI2 was first identified in strain Scott A and includes genes putatively involved in arsenic and cadmium resistance, DNA integration, conjugation, and pathogenicity. However, the genomic localization and sequence content of LGI2 remain poorly characterized. Here we investigated 85 arsenic-resistant L. monocytogenes strains, mostly of serotype 4b. All but one of the 70 serotype 4b strains belonged to clonal complex 1 (CC1), CC2, and CC4, three major clones associated with enhanced virulence. PCR analysis suggested that 53 strains (62.4%) harbored an island highly similar to LGI2 of Scott A, frequently (42/53) in the same location as Scott A (LMOf2365_2257 homolog). Random-primed PCR and whole-genome sequencing revealed seven novel insertion sites, mostly internal to chromosomal coding sequences, among strains harboring LGI2 outside the LMOf2365_2257 homolog. Interestingly, many CC1 strains harbored a noticeably diversified LGI2 (LGI2-1) in a unique location (LMOf2365_0902 homolog) and with a novel additional gene. With few exceptions, the tested LGI2 genes were not detected in arsenic-resistant strains of serogroup 1/2, which instead often harbored a Tn554-associated arsenic resistance determinant not encountered in serotype 4b. These findings indicate that in L. monocytogenes, LGI2 has a propensity for certain serotype 4b clones, exhibits content diversity, and is highly promiscuous, suggesting an ability to mobilize various accessory genes into diverse chromosomal loci.

IMPORTANCE Listeria monocytogenes is widely distributed in the environment and causes listeriosis, a foodborne disease with high mortality and morbidity. Arsenic and other heavy metals can powerfully shape the populations of human pathogens with pronounced environmental lifestyles such as L. monocytogenes. Arsenic resistance is encountered primarily in certain serotype 4b clones considered to have enhanced virulence and is associated with a large chromosomal island, Listeria genomic island 2 (LGI2). LGI2 also harbors a cadmium resistance cassette and genes putatively involved in DNA integration, conjugation, and pathogenicity. Our findings indicate that LGI2 exhibits pronounced content plasticity and is capable of transferring various accessory genes into diverse chromosomal locations. LGI2 may serve as a paradigm on how exposure to a potent environmental toxicant such as arsenic may have dynamically selected for arsenic-resistant subpopulations in certain clones of L. monocytogenes which also contribute significantly to disease.

KEYWORDS: Listeria monocytogenes, arsenic resistance, genomic island, heavy metal resistance, hypervirulent clones

INTRODUCTION

Listeria monocytogenes is the only species in the genus Listeria that causes human disease (listeriosis) transmitted via contaminated foods and manifested with severe symptoms and high mortality (1, 2). Of the three serotypes (1/2a, 1/2b, and 4b) involved in the majority (>95%) of human clinical cases, serotype 4b has been implicated in numerous outbreaks and contributes to a large portion of sporadic cases, although it is generally less common in foods and food processing facilities (3–6). Outbreaks and sporadic illnesses have frequently involved a small number of clonal groups of serotype 4b, previously designated epidemic clone I (ECI), ECIa (also referred to as ECIV), and ECII (7–9). Based on multilocus sequence typing (MLST), ECI, ECIa, and ECII correspond to clonal complex 1 (CC1), CC2, and CC6, respectively, which, together with the newly described CC4, have been recently shown to constitute widely disseminated clones of L. monocytogenes (6, 10, 11).

Analysis of serotype 4b L. monocytogenes from sporadic listeriosis in 2003 to 2008 in the United States revealed that arsenic resistance was exhibited among 27% of ECI (CC1) and 70% of ECIa (CC2) isolates and was strongly associated with arsenic resistance genes (arsA1 and arsA2) identified in the CC2 strain Scott A (9, 12–14). In the Scott A genome, these genes are part of an arsenic resistance cassette within a 35-kb chromosomal region termed Listeria genomic island 2 (LGI2) (12–14). In Scott A, LGI2 is inserted in the LMOf2365_2257 homolog (lmo2224 in strain EGD-e) (13, 14). Besides the arsenic resistance cassette, LGI2 harbors a cadmium resistance cassette and genes putatively involved in DNA integration, conjugation, and pathogenicity (12, 14, 15). However, limited information is currently available on LGI2 in other arsenic-resistant strains of L. monocytogenes. In this study, we investigated the LGI2 content and genomic location in a panel of 85 arsenic-resistant strains of L. monocytogenes of diverse genotypes, sources, and serotypes.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Arsenic-resistant strains were primarily serotype 4b and CC1, CC2, and CC4.

Analysis of our laboratory's Listeria strain collection revealed that 114 of 618 serotype 4b isolates (ca. 18%) were resistant to arsenic. Within serotype 4b, arsenic resistance was most frequently encountered in CC2 (84% of the available CC2 strains), followed by CC1 (35%) and CC4 (24%), while it was not encountered in CC6 strains and was detected only in 4% of serotype 4b strains of other clonal groups. Arsenic resistance was encountered in six of 50 (12%) serotype 1/2c isolates but was less common in serotype 1/2a (9/472; ca. 2%) and especially in serotype 1/2b (1/320; ca. 0.3%). A panel of 85 isolates derived from diverse sources and including 70 serotype 4b, all available serotype 1/2a (n = 9), the one available serotype 1/2b, and five serotype 1/2c strains were chosen for further analysis (Table 1). The strong propensity of arsenic resistance in serotype 4b has been repeatedly noted before (16–18), but the underlying eco-evolutionary mechanisms remain to be elucidated.

TABLE 1.

Arsenic-resistant L. monocytogenes strains used in this study

| Serotypea | Strainb | State or province and/or country | Yr | Sourceg | CCh | LGI2 insertion site | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4b | OLM 9 | USA | 1933 | A | CC1 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 15 | USA | 1934 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 18 | USA | 1934 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 61 | Ontario, Canada | 1951 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 93 | Ontario, Canada | 1954 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 98 | Nova Scotia, Canada | 1955 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 142 | Newfoundland, Canada | 1961 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 152 | Newfoundland, Canada | 1963 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | J4187 | WI, USA | 2006 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_2257 | 9 |

| 4b | J4600c | OK, USA | 2007 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_2257 | 20 |

| 4b | OLM 10c,d | MA, USA | 1933 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_0902 | 19 |

| 4b | OLM 125d | Ontario, Canada | 1959 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_0902 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 147d | Canada | 1961 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_0902 | This study |

| 4b | Hummusd | NAf | 1997 | E/F | CC1 | LMOf2365_0902 | This study |

| 4b | LW-A1d | NA | 2000 | E/F | CC1 | LMOf2365_0902 | 18 |

| 4b | LW-A45d | NA | 2001 | E/F | CC1 | LMOf2365_0902 | 18 |

| 4b | LW-A46d | NA | 2001 | E/F | CC1 | LMOf2365_0902 | 18 |

| 4b | J2213c,d | AZ, USA | 2003 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_0902 | 9, 14, 20 |

| 4b | J2302d | CA, USA | 2003 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_0902 | 9, 14, 20 |

| 4b | J2353d | IL, USA | 2003 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_0902 | 9, 14 |

| 4b | J2584d | VT, USA | 2003 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_0902 | 9, 14 |

| 4b | J3232d | OK, USA | 2004 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_0902 | 9, 14 |

| 4b | 2005-446d | NC, USA | 2005 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_0902 | This study |

| 4b | J3916d | NM, USA | 2006 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_0902 | 9, 14 |

| 4b | J4274d | NH, USA | 2006 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_0902 | 9, 14 |

| 4b | J5080d | NM, USA | 2008 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_0902 | 9, 14 |

| 4b | J5095d | MD, USA | 2008 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_0902 | 9, 14 |

| 4b | J5136d | SC, USA | 2008 | C | CC1 | LMOf2365_0902 | 9, 14 |

| 4b | RM15655d | CA, USA | 2012 | E/F | CC1 | LMOf2365_0902 | This study |

| 4b | BS-26c | NA | NA | E/F | CC1 | LMOf2365_0902 | 20, 18 |

| 4b | J3422c | LA, USA | 2005 | C | CC1 | Intergenicj | 20 |

| 4b | FDA 100c | NA | 1986 | E/F | CC2 | LMOf2365_2418 | 20 |

| 4b | OLM 11c | CT, USA | 1933 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | 19 |

| 4b | OLM 77 | Ontario, Canada | 1954 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 78 | Ontario, Canada | 1954 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 102 | Nova Scotia, Canada | 1955 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 117 | Nova Scotia, Canada | 1956 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 118 | Nova Scotia, Canada | 1956 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 120 | Ontario, Canada | 1957 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 121 | Ontario, Canada | 1957 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 124 | Ontario, Canada | 1958 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 127 | Newfoundland, Canada | 1959 | A | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 138 | Ontario, Canada | 1961 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 144 | Brazil | 1961 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | 4b1 | Germany | 1962 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 151 | Newfoundland, Canada | 1963 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 153 | Newfoundland, Canada | 1963 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | OLM 157 | Ontario, Canada | 1964 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 4b | Scott Ac | MA, USA | 1983 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | 12, 43 |

| 4b | FDA 11 | NA | 1987 | E/F | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | 18 |

| 4b | LW-A58 | NA | 2001 | E/F | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | 18 |

| 4b | J3290 | ME, USA | 2004 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | 9 |

| 4b | LW-A84 | NA | 2004 | E/F | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | 18 |

| 4b | J3419 | CA, USA | 2005 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | 9 |

| 4b | J3768 | CO, USA | 2005 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | 9 |

| 4b | LW-A101 | NA | 2005 | E/F | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | 18 |

| 4b | LW-A102 | NA | 2005 | E/F | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | 18 |

| 4b | LW-A103 | NA | 2005 | E/F | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | 18 |

| 4b | LW-A104 | NA | 2005 | E/F | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | 18 |

| 4b | J3921 | CT, USA | 2006 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | 9 |

| 4b | J4503 | NY, USA | 2007 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | 9 |

| 4b | J4948 | GA, USA | 2008 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | 9 |

| 4b | J4954 | CT, USA | 2008 | C | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | 9 |

| 4b | J1-220c | MA, USA | 1983 | NA | CC2 | LMOf2365_2257 | 42 |

| 4b | F8027c | NA | NA | E/F | CC315 | LMOf2365_0072 | 20 |

| 4b | OLM 12 | CT, USA | 1934 | C | CC4 | LMOf2365_2679 | This study |

| 4b | J2422 | RI, USA | 2003 | C | CC4 | LMOf2365_2679 | 9 |

| 4b | J3618 | NJ, USA | 2005 | C | CC4 | LMOf2365_2679 | 9 |

| 4b | J4434 | TN, USA | 2007 | C | CC4 | LMOf2365_2679 | 9 |

| 4b | RM16550 | CA, USA | 2012 | E/F | CC4 | LMOf2365_2679 | This study |

| 1/2c | 2008-911c | NC, USA | 2008 | C | CC9 | LMOf2365_2335 | 20 |

| 1/2c | LW-A124e | NA | 2005 | E/F | NDi | ND | This study |

| 1/2c | BUG916e | NA | NA | NA | ND | ND | This study |

| 1/2c | NC140e | NC, USA | NA | E/F | ND | ND | This study |

| 1/2c | NC191e | NC, USA | NA | E/F | ND | ND | This study |

| 1/2b | F7493 | NA | 1989 | E/F | ND | LMOf2365_2257 | This study |

| 1/2a | 2012-0070c | NC, USA | 2012 | E/F | CC14 | LMOf2365_0271 | 20 |

| 1/2a | OLM 29e | England | 1938 | A | CC31 | ND | This study |

| 1/2a | L1014ae | VA, USA | 2004 | E/F | CC8 | ND | This study |

| 1/2a | FDC 102956e | NA | 2002 | NA | ND | ND | This study |

| 1/2a | 192Ae | NC, USA | 2004 | E/F | ND | ND | This study |

| 1/2a | 2004-363e | NC, USA | 2004 | C | ND | ND | This study |

| 1/2a | L1009ae | VA, USA | 2004 | A | ND | ND | This study |

| 1/2a | L1508ae | VA, USA | 2005 | E/F | ND | ND | This study |

| 1/2a | BUG923 | NA | NA | NA | ND | ND | This study |

Serotype was determined with the PCR-based serotyping scheme devised by Doumith et al. (33).

Bold, strains PCR positive for all tested LGI2 genes.

Strain with a sequenced genome.

PCR positive for only two of the tested LGI2 genes (arsA2 and ardA).

PCR negative for all tested LGI2 genes.

NA, not available.

A, C, and E/F represent animal, clinical, and environment/food isolates, respectively.

The CC was determined as described in Materials and Methods.

ND, not determined.

Intergenic region between LMOf2365_2381 and LMOf2365_2382.

Of the 70 serotype 4b arsenic-resistant strains, all but one were members of well-known clonal complexes, including 31, 33, and 5 strains of CC1, CC2, and CC4, respectively (Table 1). CC1, CC2, CC4, and CC6 (formerly designated ECII) are major, disseminated clones of L. monocytogenes (6, 10, 11). Noteworthy in being overrepresented among human isolates and in their capacity to cause invasive disease in individuals with relatively few or no known comorbidities, CC1, CC2, CC4, and CC6 are considered to constitute “hypervirulent clones” (6). Interestingly, as mentioned above, none of the 55 CC6 strains in our collection were found to be arsenic resistant, as also was reported before for clinical isolates from sporadic listeriosis or from food isolates (9, 18).

LGI2 can reside in different chromosomal loci among arsenic-resistant strains of L. monocytogenes.

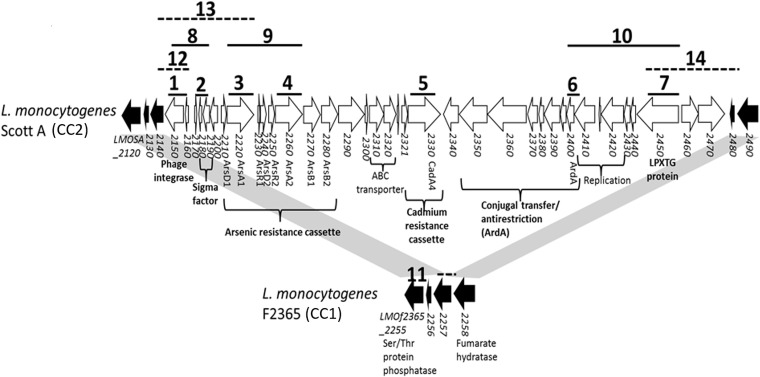

In L. monocytogenes Scott A (CC2), LGI2 is inserted in the LMOf2365_2257 homolog (14). To localize LGI2 in other strains, we first employed PCR with LMOf2365_2257 primers (PCR 11) (Fig. 1), with the hypothesis that LGI2 insertion in this gene would render the PCR product too large for amplification while the expected product would be obtained from strains with an intact LMOf2365_2257 homolog. Insertion of LGI2 in this gene was confirmed with PCR targeting the LMOf2365_2257 homolog and an LGI2-internal gene (PCRs 12 to 14) (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Genomic organization of LGI2 in L. monocytogenes Scott A. Genes within LGI2 are shown in white, whereas LGI2-flanking ORFs in strain F2365 are in black. Solid and dashed black lines indicate expected amplicons from PCRs with the corresponding numbers that were conducted to examine LGI2 diversity and confirm location within the LMOf2365_2257 homolog, respectively (Table 3).

Of the 85 arsenic-resistant strains, 43 (ca. 51%) harbored LGI2 within the LMOf2365_2257 homolog, and all but one were serotype 4b. These included 32 of the 33 CC2 strains, 10 of the 31 CC1 strains, and the sole arsenic-resistant strain of serotype 1/2b, strain F7493 (Tables 1 and 2). PCR with primers derived from different sequences on the Scott A LGI2 revealed that all serotype 4b strains with LGI2 insertions in this locus were PCR positive for all tested targets, while the serotype 1/2b strain F7493 was positive for only three of the tested LGI2 targets, arsA2, ardA, and LMOSA_2450 (Table 1).

TABLE 2.

Location of LGI2 in arsenic-resistant L. monocytogenes

| Serotype (no. of strains) | CCa | LGI2 insertion site(s)b | Tn554 arsAc |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4b (70) | CC1 (31) | LMOf2365_0902 (20), LMOf2365_2257 (10), intergenic region between LMOf2365_2381 and LMOf2365_2382 (1 [strain J3422]) | None |

| CC2 (33) | LMOf2365_2257 (32), LMOf2365_2418 (1 [strain FDA 100]) | None | |

| CC4 (5) | LMOf2365_2679 (5) | None | |

| CC315 (1; F8027) | LMOf2365_0072 (1) | None | |

| 1/2a (9) | CC14 (1; 2012-0070) | LMOf2365_0271 (1) | None |

| CC8 (1; L1014a) | ND | 1 | |

| CC31 (1; OLM 29) | ND | 1 | |

| NDd (6) | ND | 5 | |

| 1/2b (1) | ND (1; F7493) | LMOf2365_2257 (1) | None |

| 1/2c (5) | ND (4) | ND | 4 |

| CC9 (1; 2008-911) | LMOf2365_2335 (1) | 1 | |

| Total (85) | 12 |

CC, clonal complex based on MLST designations; the number of strains with the specific CC is shown in parentheses, followed by the strain designation for singletons.

The LGI2 insertion site corresponds to homologous loci in the genome of L. monocytogenes F2365 (40). The number of strains with the same insertion site is indicated in parentheses.

Number of strains PCR-positive for Tn554-associated arsA.

ND, not determined.

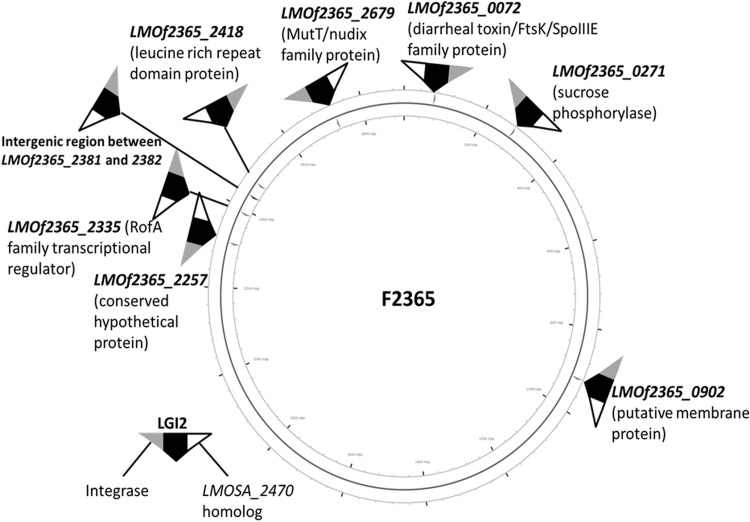

Random-primed PCR and sequencing of the PCR product were employed to determine the LGI2 location in 11 arsenic-resistant strains that harbored LGI2 outside the LMOf2365_2257 homolog. LGI2 locations were also examined via analysis of whole-genome sequence (WGS) data from 10 strains chosen to represent different serotypes (4b, 1/2a, and 1/2c), genotypes, and LGI2 locations (Table 1). In all cases, the WGS data confirmed the LGI2 insertion sites identified through PCR targeting LMOf2365_2257 or via random-primed PCR. This led to identification of seven new LGI2 insertion sites, dispersed across the chromosome (Table 2 and Fig. 2). LGI2 insertions were in coding sequences, with the exception of one strain (J3422, CC1), which harbored LGI2 in the intergenic region between the LMOf2365_2381 and LMOf2365_2382 homologs, encoding a hypothetical protein and FeS assembly protein SufB, respectively (Table 2 and Fig. 2). The locations of the islands would be expected to disrupt various genes, including homologs of LMOf2365_0072 (encoding a putative diarrheal toxin), LMOf2365_0271 (encoding sucrose phosphorylase), LMOf2365_0902 (encoding a membrane protein), LMOf2365_2335 (encoding a RofA family transcriptional regulator), LMOf2365_2418 (encoding a leucine-rich repeat domain protein), and LMOf2365_2679 (encoding a MutT/nudix family protein) (Table 2 and Fig. 2). LGI2 integration in this locus was encountered only in CC4 (Table 2).

FIG 2.

Diversity in LGI2 insertion sites in arsenic-resistant L. monocytogenes. Insertion sites identified via random-primed PCR and WGS analysis are shown in the corresponding locations in the genome of L. monocytogenes F2365 (40). The circular genome map and LGI2 insertion sites were generated with CGView Server (http://stothard.afns.ualberta.ca/cgview_server/index.html) (41) using the F2365 genome retrieved from NCBI (GenBank accession no. AE017262.2). LGI2 insertion sites are marked as arrows and LGI2 is shown as a black triangle, with termini occupied by the phage integrase gene (LMOSA_2150 homolog) and the LMOSA_2470 homolog colored in gray and white, respectively.

A marked preference for specific LGI2 insertion sites was noted in CC2 and CC4: the island was inserted in LMOf2365_2257 in 32 of the 33 CC2 strains, while all five CC4 strains harbored LGI2 in LMOf2365_2679 (Table 2). However, a diversity of insertion sites was discovered in CC1 strains, in which LIG2 was found in three different insertion sites, including the LMOf2365_2257 homolog (Table 2). No evidence was obtained for strains harboring more than one copy of LGI2.

LGI2 sequences have been diversified in certain strains, especially in CC1.

Early evidence for diversity in LGI2 content was obtained by PCR testing of the 85 arsenic-resistant strains with primers derived from seven genes in the LGI2 of Scott A. All CC2 strains (n = 33) and all five CC4 strains were PCR positive for all tested LGI2 genes, as were the single strain (F8027) of CC315 and the serotype 1/2a strain 2012-0070 (Table 1), while the serotype 1/2c strain 2008-911 was positive for all tested targets except LMOSA_2330. However, of the 31 arsenic-resistant CC1 strains, only 12 were PCR positive for all LGI2 target genes; the remaining 19 yielded the expected amplicons for only two of the target sequences, arsA2 and ardA (Table 1).

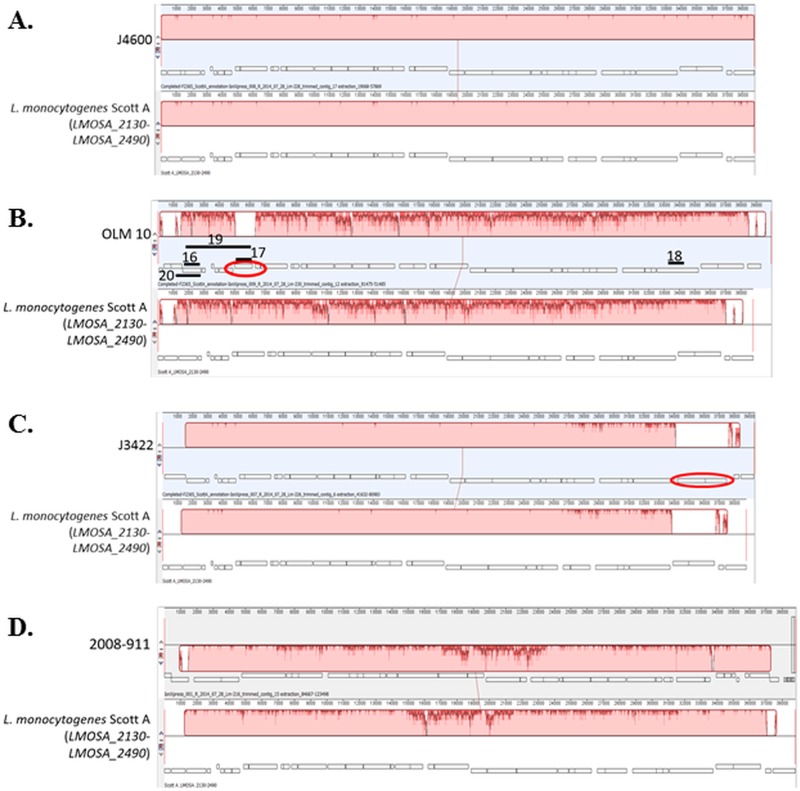

Of the 10 arsenic-resistant strains for which WGS data were available, six, i.e., the serotype 4b strains J4600 (CC1), BS-26 (CC1), FDA 100 (CC2), OLM 11 (CC2), and F8027 (CC315) and the serotype 1/2a strain 2012-0070 (CC14), were PCR positive for all targeted LGI2 sequences (Table 1). WGS data from these strains confirmed that all six harbored LGI2 which was virtually identical in content among themselves and with Scott A (Fig. 3A and data not shown). The shared LGI2 content between OLM 11 (19) and J4600 (20) was especially noteworthy, considering that these two strains belonged to different CCs (CC2 and CC1, respectively) and were isolated 74 years apart (1933 and 2007, respectively) (Table 1).

FIG 3.

WGS-based comparisons between LGI2 sequences and the LGI2 in strain Scott A. The strains are J4600 (A), OLM 10 (B), J3422 (C), and 2008-911 (D). Locus tags for the genes at the 5′ and 3′ ends in the Scott A region are shown in parentheses. Alignment was obtained with Mauve equipped within Geneious 9.1. ORFs are shown in rectangles, with those below the center line indicating reverse orientation. Color blocks represent homologous regions, with the height of dark pink peaks signifying the extent of diversity. Hence, within blocks, highly homologous regions are shaded in light pink, whereas divergent regions have multiple dark pink peaks. Ovals indicate ORFs identified in the LGI2 of the corresponding sequenced strain but absent from Scott A LGI2. For panel B, solid black lines indicate expected amplicons from PCRs 16 to 20 (Table 3).

PCR-based evidence for LGI2 diversification among CC1 strains that were PCR positive only for arsA2 and ardA was supported by WGS-based analysis of OLM 10 (19) and J2213 (20), two of the 19 CC1 strains with this PCR profile (Table 1). WGS analysis revealed that in these strains the LGI2 genes constitute syntenic but diversified homologs (63 to 89% identity at the nucleotide sequence level) of their Scott A counterparts (Fig. 3B and data not shown). The exception was six genes located at one end of LGI2 (homologs of LMOSA_2420-LMOSA_2470) that showed over 90% identity with Scott A (Fig. 3B). Both strains harbored the LGI2 in the LMOf2365_0902 homolog; in fact, all other strains with the same PCR profile harbored this LGI2 in the same location (Table 1). In addition, the LGI2 content was virtually identical between OLM 10 and J2213, in spite of their large temporal distance (70 years) (19, 20). Analysis of the sequence data suggested that negative PCR data originally obtained with these strains were due to sequence diversification in relevant primer sequences (data not shown). The LMOf2365_0902 homolog was found to be the integration site in a total of 20 strains, 19 of which were CC1 and PCR positive only for arsA2 and ardA, while one (strain BS-26) was CC1 and PCR positive for all tested LGI2 genes (Tables 1 and 2).

WGS analysis also revealed that the diversified LGI2 in OLM 10 and J2213 harbored a gene encoding a putative cystathionine γ-synthase (GenBank accession no. WP_047584133.1) which was not present in the LGI2 of Scott A (Fig. 3B). PCR with primers derived from this gene (Table 3 and Fig. 3B) indicated that it was present in all 19 CC1 strains with the same PCR profile (PCR positive only for arsA2 and ardA) (data not shown). Taken together, the data suggest that a large portion (19/31, 61%) of arsenic-resistant CC1 strains share a unique and diversified LGI2, designated here LGI2-1, found exclusively in this clonal complex and also harboring a putative cystathionine γ-synthase gene. The extent to which this gene mediates unique stress-related adaptations in these strains, such as those shown with cystathionine γ-synthase of the fungal agent Botrytis cinerea in relation to resistance to osmotic, oxidative, and thermal stresses (21), remains to be determined.

TABLE 3.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Target | PCR(s)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| LMOSA_2150F | GATCTGCACTGCGTTCTTC | LMOSA_2150 | 1, 8 |

| LMOSA_2150R | GAAGCCCAGCAAACTTATCG | LMOSA_2150 | 1, 12, 21, 22 |

| LMOSA_2180F | CTGGATCAAAATTGCGGAC | LMOSA_2180 | 2 |

| LMOSA_2180R | TACCACTAATTGAACAAGCC | LMOSA_2180 | 2, 8 |

| LMOSA_2220F | CAACTTTGACCCTGTGGAG | LMOSA_2220 | 3, 9 |

| LMOSA_2220R | CTTTCCATTCAATCACTGCG | LMOSA_2220 | 3, 13 |

| pLI37_F | CAACCAGATCAGTTACCATTAAC | LMOSA_2260 | 4 |

| pLI37_R | TGCTTCTCCAGAGATTTCTTCTG | LMOSA_2260 | 4, 9 |

| LMOSA_2330F | GCATACGTACGAACCAGAAG | LMOSA_2330 | 5 |

| LMOSA_2330R | CAGTGTTTCTGCTTTTGCTCC | LMOSA_2330 | 5 |

| LMOSA_2400F | GTCGTTTGCTTGATAGAGGCG | LMOSA_2400 | 6, 10 |

| LMOSA_2400R | GGGCGATGGTTTGAACTACC | LMOSA_2400 | 6 |

| LMOSA_2450F | TAATAGCCAGCAACTCCAGC | LMOSA_2450 | 7, 14, 22 |

| LMOSA_2450R | GAAAAAGACCGCTTGTCTCTG | LMOSA_2450 | 7, 10 |

| F2365_2257F | ACATTGCGAGAACACCTTGG | LMOf2365_2257 | 11, 12, 13 |

| F2365_2257R | GATTTATCGGCGCAATGACG | LMOf2365_2257 | 11, 14 |

| LMOSLCC2372_2751F | TAACCAATAAGCCAACACCG | LMOSLCC2372_2751 | 15 |

| LMOSLCC2372_2751R | CTTCTTTCCACTTCCCGAGC | LMOSLCC2372_2751 | 15 |

| OLM10_1F | ATCCGCCATTGCACAGAGAG | LMOSA_2150 homolog in OLM 10 | 16, 19 |

| OLM10_1R | CGTGCGGTGGCTCAAATTTT | LMOSA_2150 homolog in OLM 10 | 16, 20 |

| OLM10_2F | GCGGAGAAATTGGTGAACGG | Cystathionine γ-synthase gene in OLM 10 | 17 |

| OLM10_2R | ACAACTAGCCCTGCGGTTAC | Cystathionine γ-synthase gene in OLM 10 | 17, 19 |

| OLM10_3F | GAGTAGGGAACGTAAGCCCG | LMOSA_2450 homolog in OLM 10 | 18 |

| OLM10_3R | CCGCTGGCTCCTTTCAGTTA | LMOSA_2450 homolog in OLM 10 | 18 |

| Marq207 | GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTACNNNNNNNNNNGTAAT | Random primer with adaptor (first amplification) | 21 |

| Marq208 | GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTAC | Primer annealing to the adaptor region of Marq207 (second, nested amplification) | 21 |

| LMOSA_2150R2 | GCTATGTTACAGGAATGGCG | LMOSA_2150 | 21 |

| LMOSA_2470F | GGAAGTCAGAGATAAGCTG | LMOSA_2470 | 21,22 |

| LMOSA_2470F2 | CTTAGAAGAACTGGACTCTG | LMOSA_2470 | 21 |

| F2365_0072F | GACTAAGTTGCCGAGTGAAC | LMOf2365_0072 | 22 |

| F2365_0072R | ATCGTGTCAGCAACATGTGG | LMOf2365_0072 | 22 |

| F2365_0271F | CGTTACCCATGGTGATGCTG | LMOf2365_0271 | 22 |

| F2365_0271R | CGCTGATTTGGAATGTTTTAG | LMOf2365_0271 | 22 |

| F2365_0902F | CCGTTTTCCGCGCCATTAATAG | LMOf2365_0902 | 20, 22 |

| F2365_0902R | GCAGTAGTAACTTTGACCGC | LMOf2365_0902 | 22 |

| F2365_2335F | CACTAGTCGGAATATCCCTC | LMOf2365_2335 | 22 |

| F2365_2335R | GCGGAATATATGGAGACTTC | LMOf2365_2335 | 22 |

| F2365_2381F | CTCGCGCTCTCTAAGTAATTC | LMOf2365_2381 | 22 |

| F2365_2382R | CTGGTAAAGGCCAACGTCAAG | LMOf2365_2382 | 22 |

| F2365_2418F | CTGCTTGGTGCGATAAAATC | LMOf2365_2418 | 22 |

| F2365_2418R | GATACAGTTCCCTTACCAGC | LMOf2365_2418 | 22 |

| F2365_2679F | CTGAACAGCAGACTCGTAAG | LMOf2365_2679 | 22 |

| F2365_2679R | GAACGGATGCAGATGTTTGGC | LMOf2365_2679 | 22 |

WGS-based analysis of LGI2 revealed sequence divergence in two other strains, J3422 (serotype 4b; CC1) and 2008-911 (serotype 1/2c; CC9) (Fig. 3C and D). In the place of LMOSA_2460 and LMOSA_2470 homologs found near one end of LGI2 in other sequenced strains, J3422 harbored two new open reading frames (ORFs), which encode a hypothetical protein and a nucleotidyltransferase (Fig. 3C). These WGS findings explained the failure of random-priming PCR with a primer targeting LMOSA_2470 and also the unsuccessful PCR between the LMOSA_2470 and LMOf2365_2381 homologs for this strain (data not shown). In fact, for strain J3422, an amplicon obtained with primers annealing to LMOSA_2450 and LMOf2365_2381 was used to obtain the LGI2 sequence close to the LMOf2365_2381 homolog, revealing its intergenic region insertion site (Table 2), which was later confirmed by WGS.

In the case of the serotype 1/2c strain 2008-911, the region between LMOSA_2320 and LMOSA_2350 had noticeably diverged (approximately 80 to 85% identity for genes in this region, except for the LMOSA_2340 homolog with 92% identity) from its counterparts in Scott A (Fig. 3D). Sequence analysis indicated that the negative PCR results for one of the genes in this region, LMOSA_2330, were due to divergence in primer regions. The location of LGI2 in this strain was also unique, i.e., the LMOf2365_2335 homolog (Table 2).

An alternative arsenic resistance determinant associated with Tn554 was frequently identified among arsenic-resistant strains of serotype 1/2a and 1/2c but was not detected in serotype 4b.

The majority (70/85) of arsenic-resistant L. monocytogenes strains in our panel were of serotype 4b. The remaining 15 strains included 9 of serotype 1/2a, 5 of serotype 1/2c, and one serotype 1/2b strain (Table 1). Most (11/15) of these strains were PCR negative for all tested LGI2 genes (Table 1). As discussed above, clear evidence for LGI2 was obtained only for the serotype 1/2a strain 2012-0070 and the serotype 1/2c strain 2008-911. PCR evidence for some of the targeted LGI2 genes was also obtained for the serotype 1/2a strain BUG923 (PCR positive for ardA and LMOSA_2450) and the serotype 1/2b strain F7493 (PCR positive for ardA, LMOSA_2450, and arsA2). In the absence of WGS data for these two strains, we cannot exclude the possibility that they harbor a divergent LGI2, with sequence diversity accounting for PCR-negative results for some of the target sequences.

The identification of arsenic-resistant serotype 1/2a and 1/2c strains that were PCR negative for the LGI2-associated arsA1 and arsA2 suggested that an alternative determinant(s) conferred arsenic resistance in these strains. A Tn554-associated arsenic resistance cassette harboring arsA was earlier identified through WGS of a serotype 1/2c strain (13). PCR with primers derived from the Tn554-associated arsA (LMOSLCC2372_2751) revealed that, with the sole exception of strain 192A, our serotype 1/2a and 1/2c arsenic-resistant strains that were PCR negative for the LGI2-associated arsA1 and arsA2 were in fact PCR positive for the Tn554-associated arsA (PCR15) (Table 2). Sequencing of the amplicons from four such strains revealed that they were highly conserved among themselves and with Tn554-associated arsA (data not shown). Furthermore, Tn554-associated arsA was detected via PCR and WGS analysis outside LGI2 in the above-discussed serotype 1/2c strain 2008-911, which also harbored LGI2-associated arsA1 and arsA2 (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, none of the 70 serotype 4b arsenic-resistant strains were PCR positive for Tn554-associated arsA (Table 2), and this determinant was also not detected via WGS analysis among any of the eight sequenced serotype 4b strains. The findings suggest that in serotype 4b, in which arsenic resistance is most commonly encountered, LGI2-associated arsenic resistance genes appear to be the key contributor to resistance, while in serotypes 1/2a and 1/2c, resistance to arsenic is mediated largely by Tn554. The relative scarcity of arsenic resistance among serogroup 1/2 strains and the finding that resistance in these strains tended to be mediated by Tn554 rather than LGI2 may also reflect specific outcomes of adaption to selection pressures in food and food processing environments, where serogroup 1/2 strains tend to predominate (5, 6). A similar scenario may operate with premature stop codon mutations in inlA which result in the absence of wall-associated internalin and are common among strains of serogroup 1/2 from food and food processing facilities but are rare in serotype 4b (5, 6, 22).

Heavy metal resistance is becoming increasingly recognized as an important adaptation of several other bacterial pathogens (23–30). L. monocytogenes has a pronounced lifestyle as a saprotroph (31), and genetic determinants that render this bacterium resistant to arsenic may confer fitness advantages in arsenic-contaminated soil or water (32). The propensity of LGI2 to be associated with serotype 4b, a leading serotype for human invasive listeriosis (1, 3, 7), and especially with CC1, CC2, and CC4, which are three of the four major clones of this pathogen associated with enhanced virulence (6), also raises the possibility that arsenic resistance and other LGI2 determinants might contribute to virulence. Such potential contributions remain to be characterized. Our group is currently constructing strain derivatives with and without LGI2, which will be useful in elucidating the potential contribution of LGI2 to virulence in L. monocytogenes.

Various features of LGI2, including its sequence content and putative phage integrase-mediated insertion into the chromosome, suggest that it represents a mobile genetic element in L. monocytogenes (12, 13) (Fig. 1). Our data show that LGI2 can be integrated in diverse locations on the chromosome, even though certain integration sites, such as LMOf2365_2257, LMOf2365_2679, and LMOf2365_0902 homologs, predominate. Multiple lines of evidence presented in our study also suggest that LGI2 has undergone diversification in arsenic-resistant L. monocytogenes strains. It was especially noteworthy that the majority of arsenic-resistant CC1 strains harbored a markedly diversified LGI2 (LGI2-1), which also harbored a novel gene. These two types of LGI2 islands in CC1 may reflect differences in ecological niches, reservoirs, or adaptations of the corresponding strains, warranting further studies.

In conclusion, our assessment of the diversity and variable location of the genomic island LGI2 suggests that this may be essentially a “floating island” capable of mobilizing various accessory genes, including heavy metal resistance cassettes, into different genomic locations in L. monocytogenes. The impact of LGI2 on the population structure and biology of L. monocytogenes is to be further characterized; however, the putative functions of LGI2 genes and the expected inactivation of various chromosomal genes by the insertion of LGI2 support the hypothesis that this genomic island may contribute to environmental fitness, enhanced pathogenicity, and an accelerated evolution. Additional research is warranted to enhance our understanding of LGI2 and other mobile elements circulating in the L. monocytogenes population, potentially driving this pathogen's evolution and accessory gene acquisition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, determination of arsenic resistance, and growth conditions.

The 85 arsenic-resistant strains of L. monocytogenes originated from diverse sources and included serotypes 4b (n = 70), 1/2a (n = 9), 1/2b (n = 1), and 1/2c (n = 5) (Table 1). Serotype designations were confirmed by the multiplex PCR scheme of Doumith et al. (33). Arsenic resistance was assessed as previously described (16), and all strains displayed resistance to 500 μg/ml of sodium arsenite. Cultures were routinely grown at 37°C in brain heart infusion (BHI) (Becton, Dickinson and Co., Sparks, MD) or on BHI plates with 1.2% agar (Becton, Dickinson and Co.).

MLGT and MLST-based ST and CC designation.

Multilocus genotyping (MLGT) haplotypes were determined as previously described (34–36). Determination of MLST-based sequence type (ST) designations corresponding to each MLGT haplotype was based on whole-genome sequence (WGS) analysis of a strain panel representing diverse haplotypes (Y. Chen, T. Ward, and P. Evans, unpublished) and will be described in a separate presentation. For the arsenic-resistant strains with genomes sequenced in this study, the ST was also determined from in silico analysis of the WGS data. MLST-based clonal complexes (CCs) were based on the ST-CC correspondence data obtained from the Pasteur Institute MLST database (http://bigsdb.pasteur.fr/perl/bigsdb/bigsdb.pl?db=pubmlst_listeria_seqdef_public, accessed 11 November 2016).

PCR-based analysis of LGI2 diversity.

Arsenic-resistant strains were analyzed by PCR using primers derived from seven genes within LGI2 (PCRs 1 to 10) (Fig. 1; primer sequences are listed in Table 3). Amplified regions were chosen to include open reading frames (ORFs) at different sites in LGI2 and putatively mediating functions of special biological relevance (Fig. 1).

LGI2 insertion site identification.

The location of LGI2 was first investigated with PCR using primers F2365_2257F and F2365_2257R derived from LGI2-flanking sequences homologous to LMOf2365_2257 (PCR 11) (Fig. 1 and Table 3). To confirm the LGI2 location in the LMOf2365_2257 homolog, all strains that were PCR positive for the genes close to the ends of LGI2 (LMOSA_2150, LMOSA_2220, and LMOSA_2450) were examined by PCR using primers annealing to the LMOf2365_2257 homolog and the corresponding LGI2 gene (F2365_2257F and LMOSA_2150R, F2365_2257F and LMOSA_2220R, and LMOSA_2450F and F2365_2257R) (PCRs 12 to 14, respectively) (Fig. 1; primers are listed in Table 3). To determine the LGI2 insertion site in strains harboring LGI2 outside the LMOf2365_2257 homolog, random-primed PCR was employed as described by Cao et al. with modifications (37). Specifically, genomic DNA was used as the template for PCR using an arbitrary primer with an adaptor (Marq207) and primers specific to terminal genes of LGI2 at both ends (LMOSA_2150R and LMOSA_2470F, targeting LMOSA_2150 and LMOSA_2470, respectively) (Table 3). The PCR amplicon was used as the template in a second, nested PCR employing primer Marq208, which anneals to the adaptor region of Marq207, and a nested, gene-specific primer annealing further downstream of the gene-specific primer used in the first PCR (LMOSA_2150R2 and LMOSA_2470F2) (Table 3). The PCR products were purified with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and sequenced by Eurofins MWG Operon (Huntsville, AL) using the gene-specific primers employed in the second PCR. Sequencing results were analyzed with BLASTN against the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PROGRAM=blastn&PAGE_TYPE=BlastSearch&LINK_LOC=blasthome) (38). The insertion sites identified through random-primed PCR were confirmed with PCR amplifying the flanking region and the region between the flanking gene and a gene internal to LGI2 (Table 3).

WGS and in silico analysis of LGI2.

WGS data were obtained from a panel of 10 arsenic-resistant strains (Table 1) as described previously (19, 20). In addition, WGS data were previously available for strains ScottA and J1-220 (Table 1). Regions homologous to the Scott A LGI2 were identified and analyzed with Geneious 9.1 (Biomatters Ltd., Newark, NJ). To identify LGI2 counterparts in these genomes, Scott A LGI2 and its flanking regions (from LMOSA_2130 to LMOSA_2490) were used for BLASTN against the sequenced genomes, and hits from BLAST searches were aligned against the Scott A LGI2 region. Regions homologous to LGI2 and their flanking regions were initially annotated by finding genes exhibiting over 75% similarity to their homologs in Scott A and F2365. To identify additional genes potentially harbored on LGI2 of the sequenced strains, ORFs over 250 bp were identified, and those absent from the Scott A LGI2 were added to the annotation. These genes were further analyzed with BLASTP, BLASTN, and alignment with Scott A. To identify deletions and insertions, sequenced LGI2 regions were aligned against the Scott A LGI2 region with Mauve available in Geneious 9.1 (39). The insertion sites of the sequenced LGI2 regions were identified by aligning these regions against the F2365 genome (40). The sequence of the novel gene identified in LGI2 of OLM 10 and J2213 was used to design new primers for testing other strains (Table 3).

Presence of the Tn554-associated putative arsenic resistance determinant.

All strains in the panel were PCR tested for the Tn554-associated arsenic resistance determinant arsA (13) using primers LMOSLCC2372_2751F and LMOSLCC2372_2751R (Table 3). The arsA PCR amplicons from strains 2004-363, BUG916, LW-A124, and FDC 102956 were sequenced, and strain 2004-363 was used as positive control.

Accession number(s).

The LGI2-flanking sequences and Tn554-associated arsA sequences were deposited in NCBI (GenBank accession no. KR229741 to KR229747 and KR229748 to KR229751, respectively).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Robin Siletzky, Nathane Orwig, and Thomas Usgaard for expert technical support. We thank Wen Lin, Lewis Graves, Bala Swaminathan, Peter Gerner-Smidt, P. Cossart, Lisa Gorski, Susan Grayson, and Leslie Wolf for strains investigated in this study. We thank Yi Chen and Peter Evans for providing information on the correspondence between MLGT haplotypes and MLST designations. We are grateful to Vikrant Dutta and Mira Rakic-Martinez for insightful feedback and support.

This study is based upon work that was partially supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), under award number USDA NIFA grant 2011-2012-67017-30218, by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), NIH, under award number P30ES025128 Center for Human Health and the Environment, and by the USDA's Agricultural Research Service.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this article is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Painter J, Slutsker L. 2007. Listeriosis in humans, p 85–110. In Ryser ET, Marth EH (ed), Listeria, listeriosis, and food safety, 3rd ed CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scallan E, Griffin PM, Angulo FJ, Tauxe RV, Hoekstra RM. 2011. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—unspecified agents. Emerg Infect Dis 17:16–22. doi: 10.3201/eid1701.P21101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swaminathan B, Gerner-Smidt P. 2007. The epidemiology of human listeriosis. Microbes Infect 9:1236–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varma JK, Samuel MC, Marcus R, Hoekstra RM, Medus C, Segler S, Anderson BJ, Jones TF, Shiferaw B, Haubert N, Megginson M, McCarthy PV, Graves L, Gilder TV, Angulo FJ. 2007. Listeria monocytogenes infection from foods prepared in a commercial establishment: a case-control study of potential sources of sporadic illness in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 44:521–528. doi: 10.1086/509920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward TJ, Evans P, Wiedmann M, Usgaard T, Roof SE, Stroika SG, Hise K. 2010. Molecular and phenotypic characterization of Listeria monocytogenes from U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service surveillance of ready-to-eat foods and processing facilities. J Food Prot 73:861–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maury MM, Tsai YH, Charlier C, Touchon M, Chenal-Francisque V, Leclercq A, Criscuolo A, Gaultier C, Roussel S, Brisabois A, Disson O, Rocha EP, Brisse S, Lecuit M. 2016. Uncovering Listeria monocytogenes hypervirulence by harnessing its biodiversity. Nat Genet 48:308–313. doi: 10.1038/ng.3501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng Y, Siletzky RM, Kathariou S. 2008. Genomic divisions/lineages, epidemic clones, and population structure, p 337–358. In Liu D. (ed), Handbook of Listeria monocytogenes, 1st ed CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Knabel SJ. 2007. Multiplex PCR for simultaneous detection of bacteria of the genus Listeria, Listeria monocytogenes, and major serotypes and epidemic clones of L. monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:6299–6304. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00961-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee S, Ward TJ, Graves LM, Tarr CL, Siletzky RM, Kathariou S. 2014. Population structure of Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b isolates from sporadic human listeriosis cases in the United States from 2003 to 2008. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:3632–3644. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00454-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantinelli T, Chenal-Francisque V, Diancourt L, Frezal L, Leclercq A, Wirth T, Lecuit M, Brisse S. 2013. “Epidemic clones” of Listeria monocytogenes are widespread and ancient clonal groups. J Clin Microbiol 51:3770–3779. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01874-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ragon M, Wirth T, Hollandt F, Lavenir R, Lecuit M, Le Monnier A, Brisse S. 2008. A new perspective on Listeria monocytogenes evolution. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000146. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Briers Y, Klumpp J, Schuppler M, Loessner MJ. 2011. Genome sequence of Listeria monocytogenes Scott A, a clinical isolate from a food-borne listeriosis outbreak. J Bacteriol 193:4284–4285. doi: 10.1128/JB.05328-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuenne C, Billion A, Mraheil MA, Strittmatter A, Daniel R, Goesmann A, Barbuddhe S, Hain T, Chakraborty T. 2013. Reassessment of the Listeria monocytogenes pan-genome reveals dynamic integration hotspots and mobile genetic elements as major components of the accessory genome. BMC Genomics 14:47–2164-14–47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee S, Rakic-Martinez M, Graves LM, Ward TJ, Siletzky RM, Kathariou S. 2013. Genetic determinants for cadmium and arsenic resistance among Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b isolates from sporadic human listeriosis patients. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:2471–2476. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03551-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parsons C, Lee S, Jayeola V, Kathariou S. 2017. Novel cadmium resistance determinant in Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 83:e02580-16. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02580-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mullapudi S, Siletzky RM, Kathariou S. 2008. Heavy-metal and benzalkonium chloride resistance of Listeria monocytogenes isolates from the environment of turkey-processing plants. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:1464–1468. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02426-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLauchlin J, Hampton MD, Shah S, Threlfall EJ, Wieneke AA, Curtis GD. 1997. Subtyping of Listeria monocytogenes on the basis of plasmid profiles and arsenic and cadmium susceptibility. J Appl Microbiol 83:381–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1997.00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ratani SS, Siletzky RM, Dutta V, Yildirim S, Osborne JA, Lin W, Hitchins AD, Ward TJ, Kathariou S. 2012. Heavy metal and disinfectant resistance of Listeria monocytogenes from foods and food processing plants. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:6938–6945. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01553-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dutta V, Lee S, Ward TJ, Orwig N, Altermann E, Jima D, Parsons C, Kathariou S. 2016. Draft genome sequences of two historical Listeria monocytogenes strains from human listeriosis cases in 1933. Genome Announc 4:e01364-16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01364-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dutta V, Lee S, Ward TJ, Orwig N, Altermann E, Jima DD, Parsons C, Kathariou S. 2017. Genome sequences of Listeria monocytogenes strains with resistance to arsenic. Genome Announc 5:e00327-17. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00327-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shao W, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Lv C, Ren W, Chen C. 2016. Involvement of BcStr2 in methionine biosynthesis, vegetative differentiation, multiple stress tolerance and virulence in Botrytis cinerea. Mol Plant Pathol 17:438–447. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacquet C, Doumith M, Gordon JI, Martin PM, Cossart P, Lecuit M. 2004. A molecular marker for evaluating the pathogenic potential of foodborne Listeria monocytogenes. J Infect Dis 189:2094–2100. doi: 10.1086/420853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mourao J, Novais C, Machado J, Peixe L, Antunes P. 2015. Metal tolerance in emerging clinically relevant multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype 4,[5],12:i:− clones circulating in Europe. Int J Antimicrob Agents 45:610–616. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joerger RD, Hanning IB, Ricke SC. 2010. Presence of arsenic resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Kentucky and other serovars isolated from poultry. Avian Dis 54:1178–1182. doi: 10.1637/9285-022210-Reg.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abraham S, O'Dea M, Trott DJ, Abraham RJ, Hughes D, Pang S, McKew G, Cheong EY, Merlino J, Saputra S, Malik R, Gottlieb T. 2016. Isolation and plasmid characterization of carbapenemase (IMP-4) producing Salmonella enterica Typhimurium from cats. Sci Rep 6:35527. doi: 10.1038/srep35527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eppinger M, Radnedge L, Andersen G, Vietri N, Severson G, Mou S, Ravel J, Worsham PL. 2012. Novel plasmids and resistance phenotypes in Yersinia pestis: unique plasmid inventory of strain Java 9 mediates high levels of arsenic resistance. PLoS One 7:e32911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martins Simoes P, Rasigade JP, Lemriss H, Butin M, Ginevra C, Lemriss S, Goering RV, Ibrahimi A, Picaud JC, El Kabbaj S, Vandenesch F, Laurent F. 2013. Characterization of a novel composite staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec-SCCcad/ars/cop) in the neonatal sepsis-associated Staphylococcus capitis pulsotype NRCS-A. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:6354–6357. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01576-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larsen J, Andersen PS, Winstel V, Peschel A. 2017. Staphylococcus aureus CC395 harbours a novel composite staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec element. J Antimicrob Chemother 72:1002–1005. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Argudin MA, Lauzat B, Kraushaar B, Alba P, Agerso Y, Cavaco L, Butaye P, Porrero MC, Battisti A, Tenhagen BA, Fetsch A, Guerra B. 2016. Heavy metal and disinfectant resistance genes among livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Vet Microbiol 191:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perreten V, Chanchaithong P, Prapasarakul N, Rossano A, Blum SE, Elad D, Schwendener S. 2013. Novel pseudo-staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec element (ΨSCCmec57395) in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius CC45. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:5509–5515. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00738-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freitag NE, Port GC, Miner MD. 2009. Listeria monocytogenes-from saprophyte to intracellular pathogen. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:623–628. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2014. Soil quality—urban technical note no. 3. Heavy metal soil contamination. http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/nrcs142p2_053279.pdf Accessed 23 March 2017.

- 33.Doumith M, Buchrieser C, Glaser P, Jacquet C, Martin P. 2004. Differentiation of the major Listeria monocytogenes serovars by multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol 42:3819–3822. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.8.3819-3822.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ward TJ, Ducey TF, Usgaard T, Dunn KA, Bielawski JP. 2008. Multilocus genotyping assays for single nucleotide polymorphism-based subtyping of Listeria monocytogenes isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:7629–7642. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01127-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ducey TF, Page B, Usgaard T, Borucki MK, Pupedis K, Ward TJ. 2007. A single-nucleotide-polymorphism-based multilocus genotyping assay for subtyping lineage I isolates of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:133–147. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01453-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee S, Ward TJ, Graves LM, Wolf LA, Sperry K, Siletzky RM, Kathariou S. 2012. Atypical Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b strains harboring a lineage II-specific gene cassette. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:660–667. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06378-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cao M, Bitar AP, Marquis H. 2007. A mariner-based transposition system for Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:2758–2761. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02844-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Darling AE, Mau B, Perna NT. 2010. progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS One 5:e11147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nelson KE, Fouts DE, Mongodin EF, Ravel J, DeBoy RT, Kolonay JF, Rasko DA, Angiuoli SV, Gill SR, Paulsen IT, Peterson J, White O, Nelson WC, Nierman W, Beanan MJ, Brinkac LM, Daugherty SC, Dodson RJ, Durkin AS, Madupu R, Haft DH, Selengut J, Van Aken S, Khouri H, Fedorova N, Forberger H, Tran B, Kathariou S, Wonderling LD, Uhlich GA, Bayles DO, Luchansky JB, Fraser CM. 2004. Whole genome comparisons of serotype 4b and 1/2a strains of the food-borne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes reveal new insights into the core genome components of this species. Nucleic Acids Res 32:2386–2395. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grant JR, Stothard P. 2008. The CGView Server: a comparative genomics tool for circular genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 36:W181–W184. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Y, Strain EA, Allard M, Brown EW. 2011. Genome sequences of Listeria monocytogenes strains J1816 and J1-220, associated with human outbreaks. J Bacteriol 193:3424–3425. doi: 10.1128/JB.05048-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ward TJ, Usgaard T, Evans P. 2010. A targeted multilocus genotyping assay for lineage, serogroup, and epidemic clone typing of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:6680–6684. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01008-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]