Abstract

Adrenal ganglioneuromas (GNs) constitute rare, differentiated tumors which originate from neural crest cells. GNs are usually hormonally silent and tend to be discovered incidentally on imaging tests. Adrenalectomy is the gold standard for the treatment of primary adrenal GNs. Nevertheless, preoperative differential diagnosis of GNs remains extremely challenging, and thus histopathological examination is required in order to confirm the diagnosis of GN. Overall, prognosis after surgical resection seems to be excellent, without any recurrences or need for adjuvant therapy.

Keywords: Ganglioneuroma, Neurogenic tumors, Neural crest, Adrenalectomy

Core tip: Adrenal ganglioneuromas (GNs) are uncommon, differentiated tumors which originate from neural crest cells. These lesions are usually discovered incidentally because they tend to be hormonally silent. Even though, surgery is the gold standard for the treatment of adrenal GNs, the process of preoperative differential diagnosis remains extremely challenging. Therefore, histologic examination is necessary in order to confirm this rare diagnosis. In general, there is no need for adjuvant treatment and the overall prognosis of these patients is excellent.

INTRODUCTION

Ganglioneuromas (GNs) constitute rare, differentiated tumors which originate from neural crest cells[1]. As such, they are usually located in the retroperitoneal space (32%-52%) or in the posterior mediastinum (39%-43%). Less commonly, GNs can be seen in the cervical region (8%-9%) as well[2,3]. Interestingly enough, thoracic tumors have been found to be larger than non-thoracic ones at the time of diagnosis[4]. Adrenal GNs occur most frequently in the fourth and fifth decades of life, whereas GNs of the retroperitoneum and posterior mediastinum are usually encountered in children and younger adults. GNs seem to develop in females and males with equal rates; yet most of our data derive from case reports or small case series[5-7]. Nonetheless, a familial predisposition as well as an association with Turner syndrome and multiple endocrine neoplasia II have also been suggested[5].

Commonly, adrenal GNs are hormonally silent and as a result can be asymptomatic; even when the lesion is of substantial size[5,8]. On the other hand, it has been reported that up to 30% of patients with GNs may have elevated plasma and urinary catecholamine levels, but without exhibiting any symptoms of catecholamine excess[4]. Additionally, it has been noted that ganglion cells can secrete vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), whilst pluripotent precursor cells sometimes produce steroid hormones, such as cortisol and testosterone[9,10].

IMAGING

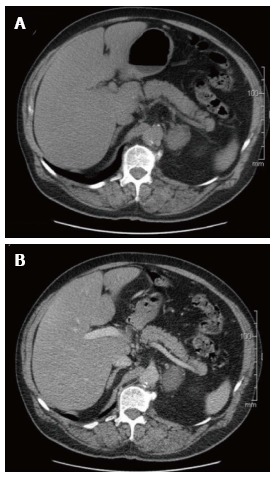

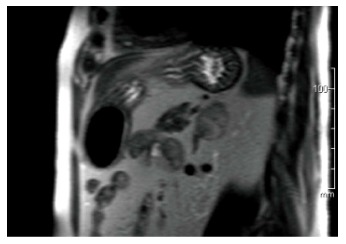

Adrenal GNs are usually discovered incidentally due to the widespread use of computed tomography (Figure 1) and MRI (Figure 2) imaging techniques[2,11]. Particularly, GNs account for approximately 0.3%-2% of all adrenal incidentalomas[12-14]. In most cases, ultrasonography reveals a well-circumscribed, homogenous, hypo-echogenic lesion[15]. Furthermore, CT findings are usually compatible with a well-defined, lobular-shaped, solid, encapsulated mass. These tumors can been seen ranging from iso-attenuating to hypo-attenuating lesions compared to muscle signals[15]. Usually, the mass surrounds major blood vessels without imposing compression or occlusion[16]. Fine, punctate calcifications are found at a frequency ranging from 20% to 69% and are considered highly indicative of GNs[5,11]. On magnetic resonance imaging, T1-weighted images tend to have homogeneously low or intermediate signal, whereas T2-weighted images have heterogeneously intermediate or high signal[17]. Arguably, the latter is caused by the presence of the myxoid matrix along with a relatively low number of ganglion cells[18]. Furthermore, gadolinium administration can result in delayed and progressive enhancement of the lesion[8,15].

Figure 1.

Axial computed tomography of left adrenal ganglioneuroma: Well-defined, solid, encapsulated mass (in intravenous contrast). A: Non-enhanced image; B: Enhanced image (venous phase).

Figure 2.

Coronal magnetic resonance imaging of left adrenal ganglioneuroma: A coronal T1-weighted out-of-phase image shows intracellular lipid and no signal loss within the lesion.

In reality, the aforementioned radiology findings are not pathognomonic of adrenal GNs[15]. Particularly the preoperative misdiagnosis rate of adrenal GNs based on CT and MRI findings has been attested to be 64.7%[5]. Also, MIBG (131-metaiodobenzylguanidine) scintigraphy produces similar results in GNs, ganglioneuroblastomas and neuroblastomas[2,15]. Recently, PET scans have been proclaimed to facilitate the diagnostic process. Particularly, Standardized Uptake Value (SUV) of 3.0 or higher has been suggested to distinguish malignant from benign adrenal lesions with 100% sensitivity and 98% specificity[19]. However, Adas et al[20] did report an adrenal GN with a SUV of 4.1 that was determined to be histologically benign. Taking everything into consideration, preoperative differential diagnosis of GNs remains extremely challenging and includes a variety of lesions, such as ganglioneuroblastoma, neuroblastoma, composite pheochromocytoma, adrenal cortical adenoma and adrenocortical carcinoma[2,21].

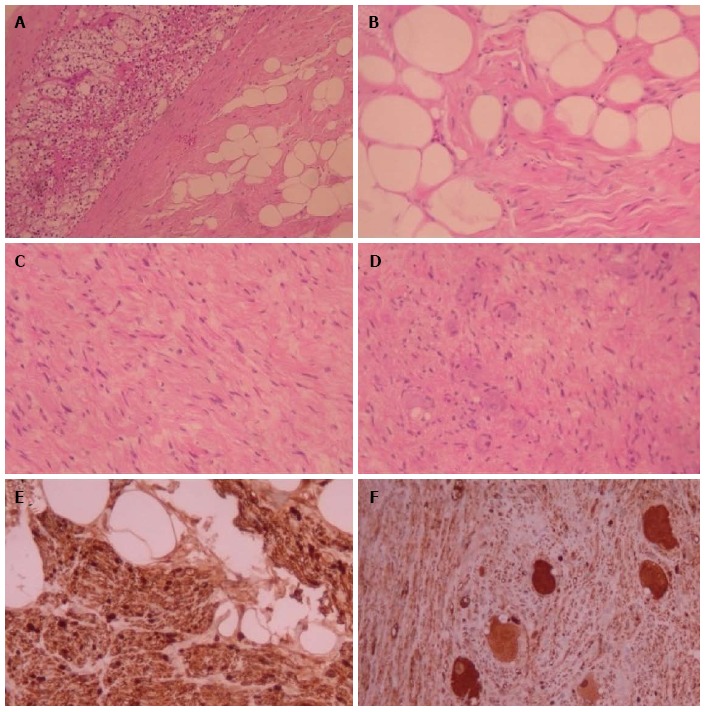

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES

Ultimately, histopathological examination is required in order to confirm the diagnosis of GN (Figure 3). In the vast majority of cases, GNs are histologically benign lesions GNs which can be classified into two main categories[4]. Firstly, “mature type” GNs comprise of mature Schwann cells, ganglion cells and perineural cells within a fibrous stroma whilst completely lacking neuroblasts and mitotic figures[8]. Secondly, “maturing type” GNs consist of similar cellular populations with miscellaneous maturation degrees, ranging from fully mature cells to neuroblasts. Nevertheless, detection of neuroblasts is typically indicative of neuroblastomas or ganglioneuroblastomas. These types of neurogenic tumors have the potential to evolve into GNs[15]. Characteristically, GNs exhibit immunohistochemical reactivity for specific markers such as S-100, vimentin, synaptophysin and neuron-specific enolase[17].

Figure 3.

Histopathologic features of adrenal ganglioneuromas. A: Margin between adrenocortical parenchyma and adrenal ganglioneuroma with Schwann cells in adipose stroma (H and E × 100); B: Schwann cells in adipose stroma (H and E × 400); C: Schwann and ganglion cells in non-adipose stroma (H and E × 200); D: Schwann cells and multiple ganglion cells (H and E × 200); E: Protein S100 (+) Schwann cells (immunostaining × 400); F: Neuron-specific enolase (+) ganglion cells (immunostaining × 200). H and E: Hematoxylin and eosin.

GENETIC FEATURES

The tyrosine kinase receptor ERBB3 is one of the most commonly up-regulated genes in GNs[22]. Additionally, recent case series have found high expression of GATA3 in all of their GN tumors (100%) meaning that this may be a very reliable marker for GNs[23,24]. Lastly, the coexistence of GN with neuroblastoma has been associated with a hemizygous deletion of 11q14.1-23.3. Indeed, the predisposition to the development of neurogenic tumors may be attributed to the deletion of the NCAM1 and CADM1 genes which lie in 11q[25]. In contrast to neuroblastomas though, GNs do not seem to exhibit MYCN gene amplifications[4].

MANAGEMENT

Last but not least, literature is consistent with the fact that when dealing with large (> 6 cm) adrenal incidentalomas there is a 25% probability of the lesion being an adrenocortical carcinoma. Geoerger et al[4] described local lymph node involvement in two GN patients and one case of distant metastasis to soft tissues in their 49-patient case series. Nonetheless, malignant GNs remain extremely rare occurrences[21]. Ultimately, surgery constitutes the gold standard for the treatment of primary adrenal GNs[4,26]. Even though, laparoscopic adrenalectomy is usually the procedure of choice, a number of variables (e.g., hormonal activity, tumor location, and proximity to adjacent structures) also need to be taken into account when deciding on the best approach to operate on these rare tumors[24]. Of note, wide excisions are unnecessary since adrenal GNs rarely metastasize or recur. Postoperatively, there is no need for adjuvant therapy in patients with adrenal GNs and their prognosis is excellent[4,21].

CONCLUSION

Adrenal GNs are uncommon, differentiated tumors which originate from neural crest cells. These lesions are usually discovered incidentally and tend to be hormonally silent. Even though, adrenalectomy is the gold standard for the treatment of adrenal GNs, the process of preoperative differential diagnosis remains extremely challenging. Ultimately, histologic examination is necessary in order to confirm this rare diagnosis. Postoperatively, there is no need for adjuvant treatment and the overall prognosis of these patients is excellent.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: April 26, 2017

First decision: May 23, 2017

Article in press: July 7, 2017

P- Reviewer: Letizia C, Lim SJ, Yoshida S, Yu SP S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

Contributor Information

Konstantinos S Mylonas, Division of Pediatric Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02114, United States; Surgery Working Group, Society of Junior Doctors, 11852 Athens, Greece.

Dimitrios Schizas, Surgery Working Group, Society of Junior Doctors, 11852 Athens, Greece; First Department of Surgery, Laiko General Hospital, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, 11527 Athens, Greece.

Konstantinos P Economopoulos, Surgery Working Group, Society of Junior Doctors, 11852 Athens, Greece; Department of Surgery, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710, United States. economopoulos@sni.gr.

References

- 1.Joshi VV. Peripheral neuroblastic tumors: pathologic classification based on recommendations of international neuroblastoma pathology committee (Modification of shimada classification) Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2000;3:184–199. doi: 10.1007/s100240050024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rha SE, Byun JY, Jung SE, Chun HJ, Lee HG, Lee JM. Neurogenic tumors in the abdomen: tumor types and imaging characteristics. Radiographics. 2003;23:29–43. doi: 10.1148/rg.231025050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zografos GN, Kothonidis K, Ageli C, Kopanakis N, Dimitriou K, Papaliodi E, Kaltsas G, Pagoni M, Papastratis G. Laparoscopic resection of large adrenal ganglioneuroma. JSLS. 2007;11:487–492. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geoerger B, Hero B, Harms D, Grebe J, Scheidhauer K, Berthold F. Metabolic activity and clinical features of primary ganglioneuromas. Cancer. 2001;91:1905–1913. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010515)91:10<1905::aid-cncr1213>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qing Y, Bin X, Jian W, Li G, Linhui W, Bing L, Huiqing W, Yinghao S. Adrenal ganglioneuromas: a 10-year experience in a Chinese population. Surgery. 2010;147:854–860. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linos D, Tsirlis T, Kapralou A, Kiriakopoulos A, Tsakayannis D, Papaioannou D. Adrenal ganglioneuromas: incidentalomas with misleading clinical and imaging features. Surgery. 2011;149:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li L, Shao J, Gu J, Wang X, Qu L. Adrenal ganglioneuromas: experience from a retrospective study in a Chinese population. Urol J. 2014;11:1485–1490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allende DS, Hansel DE, MacLennan GT. Ganglioneuroma of the adrenal gland. J Urol. 2009;182:714–715. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koch CA, Brouwers FM, Rosenblatt K, Burman KD, Davis MM, Vortmeyer AO, Pacak K. Adrenal ganglioneuroma in a patient presenting with severe hypertension and diarrhea. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2003;10:99–107. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0100099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaisa NT, Klöppel G, Brehmer B, Neulen J, Stephan P, Knüchel R, Donner A. [Virilizing adrenal ganglioneuroma: A rare differential diagnosis in testosterone secreting adrenal tumours] Pathologe. 2009;30:407–410. doi: 10.1007/s00292-009-1145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Majbar AM, Elmouhadi S, Elaloui M, Raiss M, Sabbah F, Hrora A, Ahallat M. Imaging features of adrenal ganglioneuroma: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:791. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasperlik-Zaluska AA, Roslonowska E, Slowinska-Srzednicka J, Otto M, Cichocki A, Cwikla J, Slapa R, Eisenhofer G. 1,111 patients with adrenal incidentalomas observed at a single endocrinological center: incidence of chromaffin tumors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1073:38–46. doi: 10.1196/annals.1353.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bjornsson B, Birgisson G, Oddsdottir M. Laparoscopic adrenalectomies: A nationwide single-surgeon experience. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:622–626. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9729-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JH, Chai YJ, Kim TH, Choi JY, Lee KE, Kim HY, Yoon YS, Kim HH. Clinicopathological Features of Ganglioneuroma Originating From the Adrenal Glands. World J Surg. 2016;40:2970–2975. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3630-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lonergan GJ, Schwab CM, Suarez ES, Carlson CL. Neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, and ganglioneuroma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2002;22:911–934. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.4.g02jl15911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zugor V, Schott GE, Kühn R, Labanaris AP. Retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma in childhood--a presentation of two cases. Pediatr Neonatol. 2009;50:173–176. doi: 10.1016/S1875-9572(09)60058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sasaki S, Yasuda T, Kaneto H, Otsuki M, Tabuchi Y, Fujita Y, Kubo F, Tsuji M, Fujisawa K, Kasami R, et al. Large adrenal ganglioneuroma. Intern Med. 2012;51:2365–2370. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Otal P, Mezghani S, Hassissene S, Maleux G, Colombier D, Rousseau H, Joffre F. Imaging of retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma. Eur Radiol. 2001;11:940–945. doi: 10.1007/s003300000698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mackie GC, Shulkin BL, Ribeiro RC, Worden FP, Gauger PG, Mody RJ, Connolly LP, Kunter G, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Wallis JW, et al. Use of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in evaluating locally recurrent and metastatic adrenocortical carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2665–2671. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adas M, Koc B, Adas G, Ozulker F, Aydin T. Ganglioneuroma presenting as an adrenal incidentaloma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:131. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-8-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shawa H, Elsayes KM, Javadi S, Morani A, Williams MD, Lee JE, Waguespack SG, Busaidy NL, Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, Jimenez C, et al. Adrenal ganglioneuroma: features and outcomes of 27 cases at a referral cancer centre. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2014;80:342–347. doi: 10.1111/cen.12320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilzén A, Krona C, Sveinbjörnsson B, Kristiansson E, Dalevi D, Øra I, De Preter K, Stallings RL, Maris J, Versteeg R, et al. ERBB3 is a marker of a ganglioneuroblastoma/ganglioneuroma-like expression profile in neuroblastic tumours. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:70. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nonaka D, Wang BY, Edmondson D, Beckett E, Sun CC. A study of gata3 and phox2b expression in tumors of the autonomic nervous system. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1236–1241. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318289c765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ordóñez NG. Value of GATA3 immunostaining in tumor diagnosis: a review. Adv Anat Pathol. 2013;20:352–360. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3182a28a68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shiohama T, Fujii K, Hino M, Shimizu K, Ohashi H, Kambe M, Nakatani Y, Mitsunaga T, Yoshida H, Ochiai H, et al. Coexistence of neuroblastoma and ganglioneuroma in a girl with a hemizygous deletion of chromosome 11q14.1-23.3. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170A:492–497. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Economopoulos KP, Mylonas KS, Stamou AA, Theocharidis V, Sergentanis TN, Psaltopoulou T, Richards ML. Laparoscopic versus robotic adrenalectomy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2017;38:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.12.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]