Abstract

Background

Epigenetic abnormalities play important roles in nasopharyngeal cancer (NPC), however, the epigenetic changes associated with abnormal cell proliferation remain unclear.

Methods

We detected epigenetic change of ZNF671 in NPC tissues and cell lines by bisulfite pyrosequencing. We evaluated zinc finger protein 671 (ZNF671) expression in NPC cell lines and clinical tissues using real-time PCR and western blotting. Then, we established NPC cell lines that stably overexpressed ZNF671 and knocked down ZNF671 expression to explore its function in NPC in vitro and in vivo. Additionally, we investigated the potential mechanism of ZNF671 by identifying the mitotic spindle and G2/M checkpoint pathways pathway downstream genes using gene set enrichment analysis, flow cytometry and western blotting.

Results

ZNF671 was hypermethylated in NPC tissues and cell lines. The mRNA and protein expression of ZNF671 was down-regulated in NPC tissues and cell lines and the mRNA expression could be upregulated after the demethylation agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine treatment. Overexpression of ZNF671 suppressed NPC cell proliferation and colony formation in vitro; silencing ZNF671 using a siRNA had the opposite effects. Additionally, overexpression of ZNF671 reduced the tumorigenicity of NPC cells in xenograft model in vivo. The mechanism study determined that overexpressing ZNF671 induced S phase arrest in NPC cells by upregulating p21 and downregulating cyclin D1 and c-myc.

Conclusions

Epigenetic mediated zinc finger protein 671 downregulation promotes cell proliferation and enhances tumorigenicity by inhibiting cell cycle arrest in NPC, which may represent a novel potential therapeutic target.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13046-017-0621-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: ZNF671, Hypermethylation, Proliferation, Tumorigenicity, Nasopharyngeal carcinoma

Background

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is the most common head and neck cancer in Southern China and Southeast Asia [1]. Although local and regional control has improved since the introduction of intensity-modulated radiation therapy and chemoradiotherapy, approximately 30% of patients eventually develop recurrence and/or distant metastasis [2]. Therefore, improved understanding the molecular mechanisms that regulate NPC progression is essential to develop novel treatment strategies.

Uncontrolled proliferation is a pathological characteristic of cancer cells. Protein kinase complexes composed of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) determine the progression of cells through the cell cycle. Cyclins function as the regulatory subunit and CDKs function as the catalytic subunit of the activated heterodimer complexes, which orchestrate coordinated entry into the S phase of the cell cycle [3]. Dysregulation of cell cycle components can lead to uncontrolled tumor cell proliferation and cancer [4, 5]. Clinical trials targeting CDK inhibitors have shown promise for the treatment of cancer [6, 7]; therapeutic strategies targeting cell cycle-related proteins may be effective for the treatment of myeloma and breast cancer. However, the mechanisms leading to malignant proliferation in NPC remain poorly characterized.

DNA methylation is a critical epigenetic modification involved in regulation of gene expression [8]. Dysregulated methylation of specific genes has been shown to increase NPC cell growth, invasion and migration, and may contribute to the progression and recurrence of NPC [9–11]. In a previous study, we employed Illumina Human Methylation 450 K Beadchips to perform genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of 48 samples (between 24 nasopharyngeal carcinoma tissues and 24 normal nasopharyngeal epithelial tissues) to identify aberrantly methylated genes (GSE52068) [10]. One of the top-ranked hypermethylated genes, zinc finger protein 671 (ZNF671), which contains C2H2-type zinc fingers (ZFs) and a Krüppel associated box (KRAB) domain, is a member of the KRAB-ZFP family of mammalian transcriptional repressors [12, 13] that play important roles in regulation of cell differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis and tumor suppression [14, 15]. Recent studies have demonstrated that ZNF671 is epigenetically silenced by DNA methylation and functions as a tumor suppressor in multiple carcinomas [16–18]. However, little is known about the function and mechanism of action of ZNF671 in NPC.

Here, we report that ZNF671 is downregulated and the ZNF671 promoter is hypermethylated in NPC cell lines and tissues. Overexpression of ZNF671 suppressed, while silencing ZNF671 promoted, NPC cell proliferation and colony formation in vitro and tumorigenicity in vivo. Further studies demonstrated overexpression of ZNF671 inhibited NPC cell proliferation and tumorigenicity by inducing S phase cell cycle arrest.

Methods

Cell culture and clinical specimens

Human NPC cell lines (CNE1, CNE2, HNE1, HONE1, SUNE1, 5-8F, 6-10B) were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco-BRL, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Human immortalized nasopharyngeal epithelial cell line (NP69, N2Tert) were cultured in keratinocyte serum-free medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with bovine pituitary extract (BD influx, Biosciences, USA). 293 T cells were obtained from the ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) and maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS. Four freshly frozen NPC samples and four normal nasopharyngeal epithelium samples were collected from patients undergoing biopsy at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from NPC cell lines using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions, cDNA was synthesized using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and amplified with Platinum SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix-UDG reagents (Invitrogen) using the CFX96 sequence detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) with the following primers: ZNF671 forward, 5′- GACTTAGACCTGGTTGTTGG -3′ and reverse, 5′- GTATTTAGCCAGGTGTAAGGT-3′. GAPDH was used as control for normalization.

Western blotting

RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was used to isolate proteins and the Bradford method, to determine protein concentrations. Proteins (20 μg) were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE, Beyotime), transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and incubated with primary anti-ZNF671 (1:500; Proteintech, Chicago, IL, USA), anti-cyclin D1 (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-c-myc (1:1000; Proteintech) or anti-p21 (1:1000; Proteintech) antibodies overnight at 4 °C, followed by species-matched secondary antibodies. Bands were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence.

DNA isolation and bisulfite pyrosequencing analysis

NPC cell lines were treated with or without 10 μmol/L 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (DAC; Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany) for 72 h, with the drug/media replaced every 24 h. DNA was isolated using the EZ1 DNA Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), then 1–2 μg DNA was treated with sodium bisulfite using the EpiTect Bisulfite kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Bisulfite pyrosequencing primers were designed using PyroMark Assay Design Software 2.0 (Qiagen), and were: PCR forward primer: 5′-GAATTTAGGTTAGGGATAGTTTGAT-3′ (F); PCR reverse primer: 5′-CCAAAAAAAAAATATTTCAATACC-3′ (R); sequencing primer: 5′-GG ATAGTTTGA TAGAAATAAAATG-3′(S). The PyroMark Q96 System (Qiagen) was used for the sequencing reactions and to quantify methylation.

Stable cell line establishment and ZNF671 small interfering RNAs (siRNAs)

The pSin-EF2-puro-ZNF671-HA or pSin-EF2-puro-vector plasmids were obtained from Land. Hua Gene Biosciences (Guangzhou, China); pSin-EF2-puro-Vector plasmid was used as a control. Stably transfected cells were selected using puromycin and confirmed using RT-PCR. SiRNAs targeting ZNF671 were obtained from GenePharma Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China); siRNA #1 targets ZNF671-Homo-626 cDNA (sense strand: CCUUACACCUGGCUAAAUATT; antisense strand: UAUUUAGCCAGGUGUAAGGTT) and siRNA #2 targets ZNF671-Homo-279 cDNA (sense strand: GGAAGAAUGGGAGCUUCUUTT; antisense strand: AAGAAGCUCCCAUUCUUCCTT).

Cell proliferation and colony formation assays

For the CCK-8 assay, cells (1 × 103) were seeded into 96-well plates, incubated for 0–4 days, stained with CCK-8 (Dojindo, Tokyo, Japan), and absorbance values were determined at 450 nm using a spectrophotometer. For the colony formation assay, cells (0.3 × 103) were seeded into 6-well plates, cultured for 2 weeks and the colonies were fixed in methanol, stained with crystal violet and counted.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells (2 × 105) were seeded into 6-well plates, cultured for 24 h, serum-starved for 24 h to synchronize cells at the G1/S checkpoint, trypsinized, washed with ice-cold PBS, fixed in 70% ethanol, and stored at −20 °C until analysis. Before staining, cells were gently resuspended in cold PBS and RNase A was added into cell suspension tube incubated at 37 °C for 30 min, followed by incubation with propidium iodide (PI) (Beyotime) for 20 min at room temperature. The fluorescence intensity of the cells was analyzed by flow cytometry (Gallios; Beckman-Coulter, Germany).

Animal experiments

BALB/c-nu mice (4–6 weeks old) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Beijing, China), and CNE2-vector or CNE2-ZNF671 cells (1 × 106) were subcutaneously inoculated into the dorsal flank. Tumor size was measured every 3 days and tumor volumes were calculated using the equation: volume = D × d2 × π/6, where D and d represent the longest and shortest diameters, respectively. All animal research was conducted in accordance with the detailed rules approved by the Animal Care and Use Ethnic Committee of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center and all efforts were made to minimize animal suffering.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

The GSEA software tool (version 2.0.13, www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/) was used to identify KEGG pathways (MSigDB, version 4.0) that show an overrepresentation of up- or downregulated genes between ZNF671 high expression (n = 15) and ZNF671 low expression (n = 16) in GSE12452. Briefly, an enrichment score was calculated for each gene set (i.e., KEGG pathway) by ranking each gene by their expression difference using Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistic, computing a cumulative sum of each ranked in each gene set, and recording the maximum deviation from zero as the enrichment score.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments, and values are expressed as the mean ± SD. Differences between two groups were analyzed using the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; p < 0.05 was considered significant. All data from this study has been deposited at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center for future reference (number RDDB2017000075).

Results

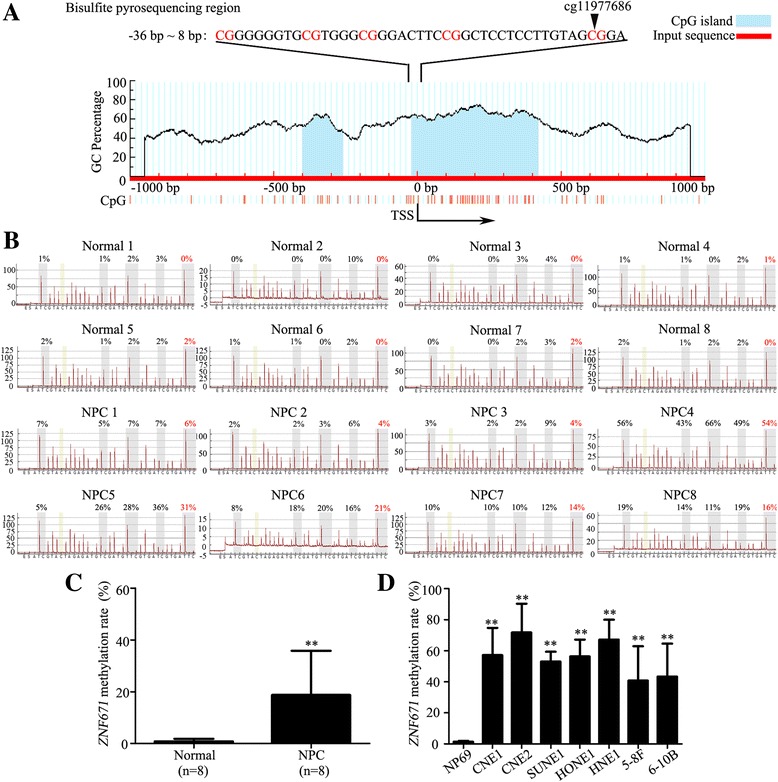

The ZNF671 promoter is hypermethylated in NPC

To confirm our previous methylation data (GSE52068) (Additional file 1: Figure S1A), the promoter methylation level of ZNF671 was detected by bisulfite pyrosequencing analysis in other NPC (n = 8) and normal tissues (n = 8). The CpG islands and region selected for bisulfite pyrosequencing in the ZNF671 promoter region are shown in Fig. 1a. The methylation of ZNF671 (cg11977686) in NPC tissues were significantly increased compared with normal tissues (Fig. 1b and c). Similarly, ZNF671 (cg11977686) methylation levels in the NPC cell lines (CNE1, CNE2, SUNE1, HONE1, HNE1, 5-8F and 6-10B) were also increased compared with human immortalized normal nasopharyngeal epithelial cell line (NP69) (Fig. 1d and Additional file 1: Figure S1B; P < 0.05). These results indicate that ZNF671 promoter is hypermethylated in NPC.

Fig. 1.

ZNF671 is hypermethylated in NPC. a Schematic illustration of the ZNF671 promoter CpG islands and bisulfite pyrosequencing region. Input sequence: red region; CpG islands: blue region; TSS: transcription start site; cg11977686: CG site identified in our previous genome-wide methylation analysis; red text: CG sites for bisulfite pyrosequencing; bold red text: most significantly altered CG site in ZNF671. b and c Bisulfite pyrosequencing analysis of the ZNF671 promoter region (b) and the average methylation levels (c) in normal (n = 8) and NPC (n = 8) tissues. Red text: cg11977686 CG site. d Bisulfite pyrosequencing analysis of ZNF671 promoter region, as determined by bisulfite pyrosequencing analysis, in NP69 and NPC (CNE1, CNE2, SUNE1, HONE1, HNE1, 5-8F and 6-10B) cell lines. d Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of ZNF671 mRNA expression in NPC cell lines after DAC treatment. All experiments were performed at least three times; data are mean ± SD. **P < 0.01 vs. control, Student’s t-test

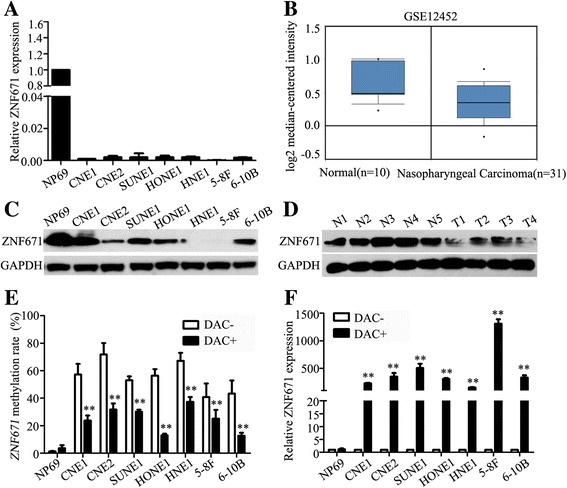

Promoter hypermethylation contributes to downregulation of ZNF671 in NPC

To know the association between ZNF671 expression and its promoter methylation status in NPC, quantitative RT-PCR revealed ZNF671 mRNA was significantly downregulated in all seven NPC cell lines compared to normal nasopharyngeal epithelial NP69 cells (Fig. 2a). Analysis of microarray-based high-throughput NPC datasets (GSE12452) confirmed ZNF671 was downregulated in NPC tissues compared to normal nasopharyngeal tissues (Fig. 2b; P < 0.05). Furthermore, western blotting showed ZNF671 protein expression was downregulated in both the NPC cell lines and freshly frozen NPC tissues (n = 4) compared to normal samples (n = 4) (Fig. 2c and d; P < 0.05). To determine whether the downregulation of ZNF671 results from its promoter hypermethylation, immortalized normal nasopharyngeal epithelial cell line and NPC cell lines were treated with or without the demethylation drug 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (Decitabine, DAC). The ZNF671 methylation level were substantially decreased (Fig. 2e and Additional file 2: Figure S2; P < 0.05), while the ZNF671 mRNA were significantly increased (Fig. 2f; P < 0.05) in NPC cell lines compared with immortalized normal nasopharyngeal epithelial cell. The findings suggest that ZNF671 is downregulated in NPC and the downregulation of ZNF671 is associated with the hypermethylation of ZNF671 in NPC.

Fig. 2.

Promoter hypermethylation contributes to downregulation of ZNF671 in NPC. a Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of ZNF671 mRNA expression in NP69 and NPC cell lines. b ZNF671 mRNA is downregulated in the GSE12452 nasopharyngeal carcinoma dataset. c-d Western blotting analysis of ZNF671 in NPC (CNE1, CNE2, SUNE1, HONE1, HNE1, 5-8F and 6-10B) cell lines and NPC (T, n = 4) and normal nasopharyngeal epithelial tissues (N, n = 4). e and f ZNF671 methylation levels measured via bisulfite pyrosequencing analysis (e) and relative ZNF671 mRNA levels measured via real-time RT–PCR analysis (f) with (DAC+) or without (DAC−) DAC treatment in NP69 and NPC cell lines. All experiments were repeated at least three times; data are mean ± SD; P-values were calculated using the Student’s t-test

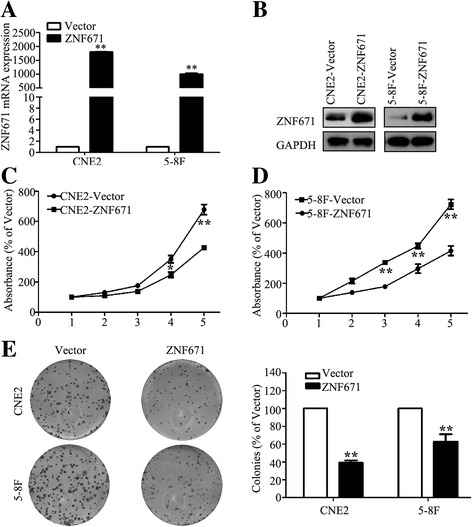

ZNF671 suppresses NPC cell proliferation in vitro

To assess the effects of ZNF671 on proliferation and metastasis in NPC, we subjected CNE2 and 5-8F cells stably overexpressing ZNF671 or the control vector to the CCK8, colony formation and Transwell migration and invasion assays. As shown in Fig. 3a and b, qPCR and western blotting validated that ZNF671 mRNA and protein level was obviously elevated after stably overexpressing ZNF671 in NPC cells. The CCK8 assay demonstrated that the cell viability of CNE2 and 5-8F cells stably overexpressing ZNF671 remarkably was much slower than that of cells expressing vector plasmid (Fig. 3c and d). Overexpressing ZNF671 reduced the colony formation ability of CNE2 and 5-8F cells (Fig. 3e), but did not significantly affect cell migratory or invasive ability (Additional file 3: Figure S3). These findings indicate that ZNF671 inhibits the proliferation abilities of NPC cells in vitro.

Fig. 3.

Effects of ZNF671 overexpression on NPC cell viability and colony formation ability in vitro. a qPCR analysis of ZNF671 mRNA expression in CNE-2 and 5-8F cells stably overexpression ZNF671. b Western blotting analysis of ZNF671 expression in CNE-2 and 5-8F cells stably overexpression ZNF671. c-d The CCK-8 assay showed overexpression of ZNF671 reduced the viability of CNE2 (c) and 5-8F (d) cells. e The colony formation assay showed overexpression of ZNF671 suppressed colony-forming ability. All experiments were performed at least three times; data are mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. control, Student’s t-test

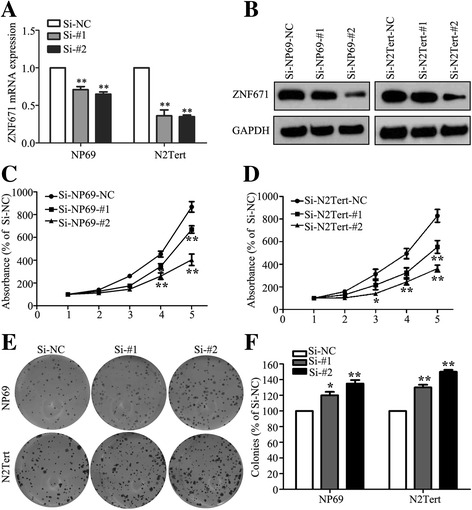

Silencing ZNF671 promotes NPC cell proliferation in vitro

To further investigate whether silencing of ZNF671 affects the proliferation abilities of NPC cells, we transiently transfected NP69 and N2Tert cells with siZNF671 or control siRNA, and performed the CCK8 and colony formation assays. As shown in Fig. 4a and b, qPCR and western blotting confirmed that the ZNF671 mRNA and protein level was remarkably decreased after silencing of ZNF671 in NPC cells. The CCK8 assay that cells transfected with siZNF671 grew faster than cells transfected with control siRNA (Fig. 4c and d). Knocking down ZNF671 promoted NPC cell colony formation capability as determined by the colony formation ability (Fig. 4e). Collectively, these results indicate that silencing ZNF671 promotes cell proliferation in NPC.

Fig. 4.

Effects of ZNF671 silencing on NPC cell viability and colony formation in vitro. a qPCR analysis of ZNF671 silence in NP69 and N2Tert cells. b Western blotting analysis of ZNF671 silence in NP69 and N2Tert cells. c-d Silencing ZNF671 increased the proliferation (c) and colony formation (d) ability of nasopharyngeal epithelial NP69 and N2Tert cells. All experiments were performed at least three times; data are mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. control, Student’s t-test

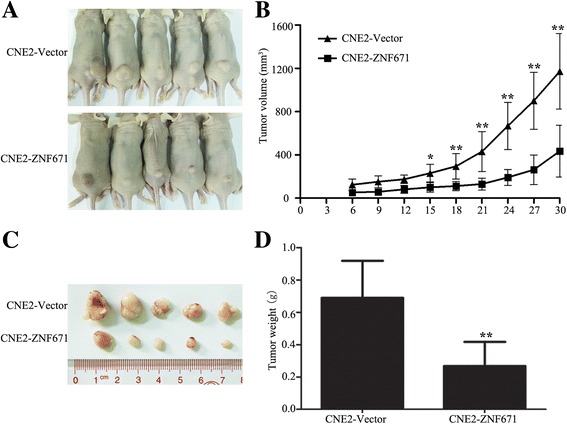

ZNF671 inhibits tumorigenicity in an in vivo model of NPC

Next, the effect of ZNF671 on the tumorigenicity of human NPC cells was examined in vivo. As shown in Fig. 5a and b, the tumors in the group injected with cells stably overexpressing ZNF671 grew at a slower rate and had smaller volumes than the vector control tumors. When the mice were sacrificed on day 30, the tumors formed by ZNF671-overexpressing cells were significantly lighter than vector control tumors (0.69 ± 0.18 g vs. 0.27 ± 0.14 g; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; Fig. 5c and d). Taken together, these results indicate that downregulation of ZNF671 enhances the tumorigenicity of NPC cells in vivo.

Fig. 5.

ZNF671 reduces the tumorigenicity of NPC cells in vivo. a BALB/c mice were injected with the indicated cells. Images of the mice and tumors formed at 30 days after injection. b Growth curves of tumor volume. c Images of the excised tumors. d Excised tumor weight. Data are mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. control, Student’s t-test

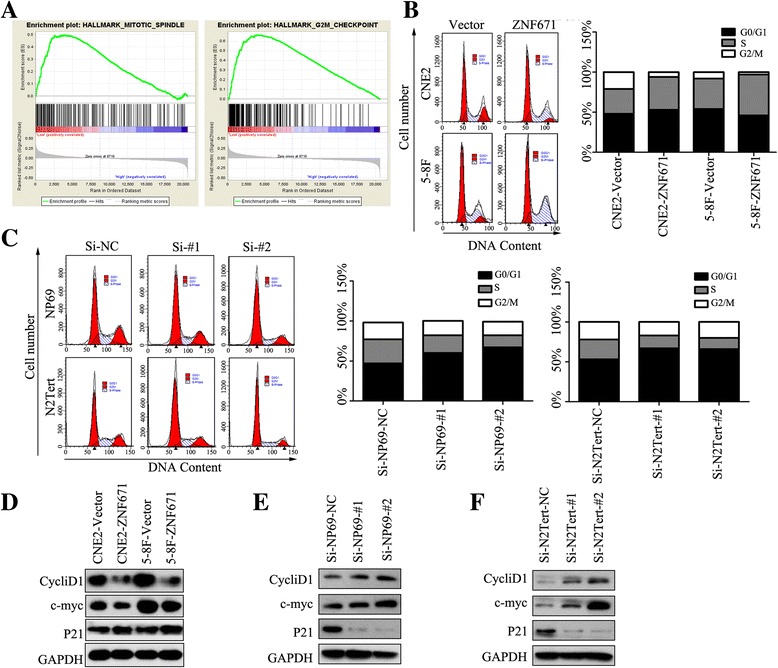

ZNF671 inhibits NPC cell proliferation by inducing S phase cell cycle arrest

To further investigate the mechanism by which ZNF671 inhibits cell proliferation in NPC, we performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) in the GEO database to identify pathways potentially linked to ZNF671. As shown in Fig. 6a, pathways related to hallmarks of the mitotic spindle and G2/M checkpoint genes were enriched in GSE12452 database. Indeed, we observed enrichment of gene sets associated with cancer, including the mitotic spindle and G2/M checkpoint pathways, in ZNF671-high expressing tumors; conversely, these pathways were not enriched in ZNF671-low expressing tumors.

Fig. 6.

ZNF671 induces cell cycle arrest at the S phase. a GSEA enrichment plots revealed that enrichment of mitotic spindle and G2/M checkpoint pathways was associated with downregulation of ZNF671. b-c Flow cytometry analysis of cell cycle distribution in cells overexpressing ZNF671 and (c) after silencing ZNF671. d-f Western blot analysis of proteins related to the S phase in cells overexpressing ZNF671 and (e-f) after silencing ZNF671

Flow cytometry confirmed that overexpression of ZNF671 significantly decreased the percentage of cells in the G2/M phase (20.67% ± 0.34% vs. 6.40% ± 0.22% in CNE2 cells, 8.47% ± 1.20% vs. 4.04% ± 0.56% in 5-8F cells; P < 0.05) and increased the proportion of cells in the S phase (30.88% ± 0.12% vs. 41.12% ± 0.28% in CNE2 cells, 36.64% ± 0.92% vs. 51.94% ± 0.23% in 5-8F cells; P < 0.05; Fig. 6b). Conversely, silencing ZNF671 decreased the percentage of cells in the S phase (from 27.92% ± 4.3% to 14.05% ± 0.73% and 20.29% ± 1.6% in NP69-Si#1 and NP69-Si#2 cells, and from 25.21% ± 0.10% to 17.69% ± 4.32% and 16.18% ± 1.38% in N2Tert-Si#1 and N2tert-Si#2 cells; Fig. 6c; P < 0.05). Furthermore, bioinformatics analysis indicated that ZNF671 is involved in regulation of the cycle-related proteins cyclin D1 and p21. Overexpression of ZNF671 decreased the protein levels of cyclin D1 and c-myc, and increased p21 (Fig. 6d). Additionally, silencing ZNF671 increased the expression of cyclin D1 and c-myc and decreased the expression of p21 (Fig. 6e and f). Taken together, these data indicate that downregulation of ZNF671 in NPC promotes cell proliferation by preventing S phase cell cycle arrest.

Discussion

This study demonstrates ZNF671 is downregulated in NPC, consistent with our previous analysis of publicly available NPC datasets [13], due to promoter hypermethylation. Moreover, overexpressing ZNF671 reduced NPC cell viability and colony formation in vitro, enhanced tumorigenicity in vivo, and induced cell cycle arrest. These results provide new mechanistic understanding of the ability of ZNF671 to regulate cell proliferation in NPC.

Local recurrence and distant metastasis are the major patterns of treatment failure in NPC. Most cancers are caused by accumulation of genomic or epigenetic alterations [19–24], and epigenetic alterations play an important role in the development of NPC [9, 25]. Several studies have indicated that aberrantly methylated genes could serve as prognostic biomarkers for NPC [26–28]. Thus, exploration of the mechanisms by which gene methylation contributes to progression and recurrence are important strategies for improving prognosis and designing targeted therapies for NPC.

ZNF671, a member of the KRAB-ZF family, is silenced by promoter methylation in renal cell, cervical carcinoma and urothelial carcinoma [16, 18, 29]. A number of ZNF proteins function as tumor suppressors, and are epigenetically silenced by DNA methylation in multiple human cancers [14, 30]. We demonstrated ZNF671 mRNA and protein expression are downregulated in NPC cell lines and tissues. Furthermore, overexpression of ZNF671 suppressed NPC cell viability and colony formation in vitro and reduced tumorigenicity in vivo. These findings indicate that ZNF671 functions as a tumor suppressor in NPC, consistent with its role in urothelial carcinoma [16].

Several individual components of the cell cycle machinery are subject to aberrant methylation, which contributes to malignancy in several cancers [31–33]. The S phase cell cycle check point ensures synthesis of DNA and proteins and is a crucial regulator of cell cycle progression, while the G2/M checkpoint allows cells to enter mitosis [34, 35]. Cyclin D1 and p21 cyclin-dependent kinases are major regulators of S phase progression [36–38]. Recent studies showed the transcriptionally repressive ZNF-KRAB domain can recruit KRAB-associated protein-1 (KAP1) [12, 13, 39] and other co-repressors, and KRAB-ZFP forms heterochromatin with chromobox 5 (CBX5), SET domain bifurcated 1 (SETDB1) and various histone deacetylases (HDACs) to epigenetically silence KRAB-ZNF target genes [40–42]. Our bioinformatic analysis showed ZNF671 affects NPC cell proliferation by regulating the mitotic spindle and G2/M checkpoint pathways. Flow cytometry and western blotting confirmed overexpression of ZNF671 induced S phase cell cycle arrest and blocked G2/M phase progression by downregulating cyclin D1 and c-myc and upregulating p21.

Conclusions

The potential tumor suppressor ZNF671 is epigenetically silenced by promoter methylation in NPC. Downregulation of ZNF671 promotes NPC cell proliferation and tumorigenicity by facilitating cell cycle progression. These findings provide new insight into the molecular mechanisms that regulate NPC progression and may help to identify novel therapeutic targets and strategies.

Additional files

ZNF671 is hypermethylated in NPC. (A) Methylation levels of ZNF671 in Normal (n = 24) and NPC (n = 24) tissues from the genome-wide methylation microarray data. Mean ± ± SD; Student’s t-tests. (B) Bisulfite pyrosequencing analysis of the ZNF671 promoter region in NP69 and NPC (CNE1, CNE2, SUNE1, HONE1, HNE1, 5-8F and 6-10B) cell lines. Red words: CG site of cg11977686. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. control, Student’s t-test. (TIFF 831 kb)

ZNF671 is hypermethylated in NPC cells. Bisulfite pyrosequencing analysis of the ZNF671 promoter region in NP69 and NPC (CNE1, CNE2, SUNE1, HONE1, HNE1, 5-8F and 6-10B) cell lines following treatment with DAC. Red words: CG site of cg11977686. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. control, Student’s t-test. (TIFF 861 kb)

ZNF671 has no effect on affect NPC migratory and invasive ability. (A) Migration ability was measured using a wound healing assay (200 ×) and (B) Transwell assay with Matrigel (200 ×) in CNE2 and SUNE1 cells with the vector or ZNF671 overexpression. Scale bar: 100 μm; data are mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. control, Student’s t-test. (TIFF 1066 kb)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Nature Science Foundation of China (81372409; 81572658); the Science and Technology Project of Guangzhou City, China (2014 J4100182); the National Science & Technology Pillar Program during the Twelfth Five-year Plan Period (2014BAI09B10); and the Program of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities (B14035).The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish or the preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CCK-8

Cell counting kit-8

- DAC

5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- GSEA

Gene set enrichment analysis

- HDAC

Histone deacetylase

- NPC

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- PAGE

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PI

Propidium iodide

- RT-PCR

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

- siRNA

Small interfering RNA

Authors’ contributions

JZ, XW, NL and YL carried out all experiments, prepared figures and drafted the manuscript. XY, QH, XT and YW participated in data analysis and interpretation of results. PZ, NL, JM and YS designed the study and participated in data analysis. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards and according to the Declaration of Helsinki and according to national and international guidelines and has been approved by the ethics committee of Sun Yat-sen university Cancer center.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13046-017-0621-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Jian Zhang, Email: zhangjian@sysucc.org.cn.

Xin Wen, Email: wenxin1@sysucc.org.cn.

Na Liu, Email: liun1@sysucc.org.cn.

Ying-Qin Li, Email: liyingq@sysucc.org.cn.

Xin-Ran Tang, Email: tangxr@sysucc.org.cn.

Ya-Qin Wang, Email: wangyaq@sysucc.org.cn.

Qing-Mei He, Email: heqm@sysucc.org.cn.

Xiao-Jing Yang, Email: yangxiaoj@sysucc.org.cn.

Pan-Pan Zhang, Email: zhangpp@sysucc.org.cn.

Jun Ma, Phone: +86-20-87343469, Email: majun2@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Ying Sun, Phone: +86-20-87342370, Email: sunying@sysucc.org.cn.

References

- 1.Cao SM, Simons MJ, Qian CN. The prevalence and prevention of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in China. Chin J Cancer. 2011;30:114–119. doi: 10.5732/cjc.010.10377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai SZ, Li WF, Chen L, Luo W, Chen YY, Liu LZ, Sun Y, Lin AH, Liu MZ, Ma J. How does intensity-modulated radiotherapy versus conventional two-dimensional radiotherapy influence the treatment results in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80:661–668. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nigg EA. Cyclin-dependent protein kinases: key regulators of the eukaryotic cell cycle. BioEssays. 1995;17:471–480. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ai MD, Li LL, Zhao XR, Wu Y, Gong JP, Cao Y. Regulation of survivin and CDK4 by Epstein-Barr virus encoded latent membrane protein 1 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell lines. Cell Res. 2005;15:777–784. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li X, Liu F, Lin B, Luo H, Liu M, Wu J, Li C, Li R, Zhang X, Zhou K, et al. miR150 inhibits proliferation and tumorigenicity via retarding G1/S phase transition in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2017;10 doi: 10.3892/ijo.2017.3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.O'Leary B, Finn RS, Turner NC. Treating cancer with selective CDK4/6 inhibitors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13:417–430. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar SK, LaPlant B, Chng WJ, Zonder J, Callander N, Fonseca R, Fruth B, Roy V, Erlichman C, Stewart AK, et al. Dinaciclib, a novel CDK inhibitor, demonstrates encouraging single-agent activity in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma. Blood. 2015;125:443–448. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-573741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baylin SB, Jones PA. A decade of exploring the cancer epigenome - biological and translational implications. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:726–734. doi: 10.1038/nrc3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruce JP, Yip K, Bratman SV, Ito E, Liu FF. Nasopharyngeal cancer: molecular landscape. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3346–3355. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.7846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang W, Liu N, Chen XZ, Sun Y, Li B, Ren XY, Qin WF, Jiang N, YF X, Li YQ, et al. Genome-wide identification of a Methylation gene panel as a prognostic biomarker in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:2864–2873. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tian F, Yip SP, Kwong DL, Lin Z, Yang Z, VW W. Promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes in serum as potential biomarker for the diagnosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37:708–713. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Witzgall R, O'Leary E, Leaf A, Onaldi D, Bonventre JV. The Kruppel-associated box-a (KRAB-A) domain of zinc finger proteins mediates transcriptional repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:4514–4518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urrutia R. KRAB-containing zinc-finger repressor proteins. Genome Biol. 2003;4:231. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-10-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng Y, Geng H, Cheng SH, Liang P, Bai Y, Li J, Srivastava G, Ng MH, Fukagawa T, Wu X, et al. KRAB zinc finger protein ZNF382 is a proapoptotic tumor suppressor that represses multiple oncogenes and is commonly silenced in multiple carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6516–6526. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng L, Pan H, Li S, Flesken-Nikitin A, Chen PL, Boyer TG, Lee WH. Sequence-specific transcriptional corepressor function for BRCA1 through a novel zinc finger protein, ZBRK1. Mol Cell. 2000;6:757–768. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeh CM, Chen PC, Hsieh HY, Jou YC, Lin CT, Tsai MH, Huang WY, Wang YT, Lin RI, Chen SS, et al. Methylomics analysis identifies ZNF671 as an epigenetically repressed novel tumor suppressor and a potential non-invasive biomarker for the detection of urothelial carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:29555–29572. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tian Y, Arai E, Gotoh M, Komiyama M, Fujimoto H, Kanai Y. Prognostication of patients with clear cell renal cell carcinomas based on quantification of DNA methylation levels of CpG island methylator phenotype marker genes. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:772. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansel A, Steinbach D, Greinke C, Schmitz M, Eiselt J, Scheungraber C, Gajda M, Hoyer H, Runnebaum IB, Durst M. A promising DNA methylation signature for the triage of high-risk human papillomavirus DNA-positive women. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniele G, Simonetti G, Fusilli C, Iacobucci I, Lonoce A, Palazzo A, Lomiento M, Mammoli F, Marsano RM, Marasco E, et al. Epigenetically induced ectopic expression of UNCX impairs the proliferation and differentiation of myeloid cells. Haematologica. 2017;102:1204–1214. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.163022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell. 2007;128:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adeegbe D, Liu Y, Lizotte PH, Kamihara Y, Aref AR, Almonte C, Dries R, Li Y, Liu S, Wang X, et al. Synergistic Immunostimulatory effects and therapeutic benefit of combined Histone Deacetylase and Bromodomain inhibition in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:852-867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Zhang Y, Yuan Y, Liang P, Guo X, Ying Y, Shu XS, Gao M, Jr, Cheng Y. OSR1 is a novel epigenetic silenced tumor suppressor regulating invasion and proliferation in renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:30008–30018. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Croes L, Op de Beeck K, Pauwels P, Vanden Berghe W, Peeters M, Fransen E, Van Camp G. DFNA5 promoter methylation a marker for breast tumorigenesis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:31948–31958. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ngollo M, Lebert A, Daures M, Judes G, Rifai K, Dubois L, Kemeny JL, Penault-Llorca F, Bignon YJ, Guy L, et al. Global analysis of H3K27me3 as an epigenetic marker in prostate cancer progression. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:261. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3256-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li LL, Shu XS, Wang ZH, Cao Y, Tao Q. Epigenetic disruption of cell signaling in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Chin J Cancer. 2011;30:231–239. doi: 10.5732/cjc.011.10080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ye M, Huang T, Ni C, Yang P, Chen S. Diagnostic capacity of RASSF1A promoter Methylation as a biomarker in tissue, brushing, and blood samples of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. EBioMedicine. 2017;18:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren X, Yang X, Cheng B, Chen X, Zhang T, He Q, Li B, Li Y, Tang X, Wen X, et al. HOPX hypermethylation promotes metastasis via activating SNAIL transcription in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14053. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang W, Cai R, Chen QQ. DNA Methylation biomarkers for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: diagnostic and prognostic tools. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:8059–8065. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.18.8059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arai E, Chiku S, Mori T, Gotoh M, Nakagawa T, Fujimoto H, Kanai Y. Single-CpG-resolution methylome analysis identifies clinicopathologically aggressive CpG island methylator phenotype clear cell renal cell carcinomas. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:1487–1493. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Severson PL, Tokar EJ, Vrba L, Waalkes MP, Futscher BW. Coordinate H3K9 and DNA methylation silencing of ZNFs in toxicant-induced malignant transformation. Epigenetics. 2013;8:1080–1088. doi: 10.4161/epi.25926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moghaddaskho F, Eyvani H, Ghadami M, Tavakkoly-Bazzaz J, Alimoghaddam K, Ghavamzadeh A, Ghaffari SH. Demethylation and alterations in the expression level of the cell cycle-related genes as possible mechanisms in arsenic trioxide-induced cell cycle arrest in human breast cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1010428317692255. doi: 10.1177/1010428317692255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei F, Ding L, Wei Z, Zhang Y, Li Y, Qinghua L, Ma Y, Guo L, Lv G, Liu Y. Ribosomal protein L34 promotes the proliferation, invasion and metastasis of pancreatic cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7:85259–85272. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sak A, Kubler D, Bannik K, Groneberg M, Strunz S, Kriehuber R, Stuschke M. Epigenetic silencing and activation of transcription: influence on the radiation sensitivity of glioma cell lines. Int J Radiat Biol. 2017;93:494–506. doi: 10.1080/09553002.2017.1270472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun H, Hou H, Lu P, Zhang L, Zhao F, Ge C, Wang T, Yao M, Li J. Isocorydine inhibits cell proliferation in hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines by inducing G2/m cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36808. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang W, Luo J, Xiang F, Liu X, Jiang M, Liao L, Hu J. Nucleolin down-regulation is involved in ADP-induced cell cycle arrest in S phase and cell apoptosis in vascular endothelial cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barr AR, Cooper S, Heldt FS, Butera F, Stoy H, Mansfeld J, Novak B, Bakal C. DNA damage during S-phase mediates the proliferation-quiescence decision in the subsequent G1 via p21 expression. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14728. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xie J, Yu H, Song S, Fang C, Wang X, Bai Z, Ma X, Hao S, Zhao HY, Sheng J. Pu-erh tea water extract mediates cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:190. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li H, Yang S, Yu G, Shen L, Fan J, Xu L, Zhang H, Zhao N, Zeng Z, Hu T, et al. Aptamer internalization via Endocytosis inducing S-phase arrest and priming Maver-1 lymphoma cells for Cytarabine chemotherapy. Theranostics. 2017;7:1204–1213. doi: 10.7150/thno.17069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Margolin JF, Friedman JR, Meyer WK, Vissing H, Thiesen HJ, Rauscher FJ., 3rd Kruppel-associated boxes are potent transcriptional repression domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:4509–4513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Underhill C, Qutob MS, Yee SP, Torchia J. A novel nuclear receptor corepressor complex, N-CoR, contains components of the mammalian SWI/SNF complex and the corepressor KAP-1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40463–40470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007864200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schultz DC, Ayyanathan K, Negorev D, Maul GG, Rauscher FJ., 3rd SETDB1: a novel KAP-1-associated histone H3, lysine 9-specific methyltransferase that contributes to HP1-mediated silencing of euchromatic genes by KRAB zinc-finger proteins. Genes Dev. 2002;16:919–932. doi: 10.1101/gad.973302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sripathy SP, Stevens J, Schultz DC. The KAP1 corepressor functions to coordinate the assembly of de novo HP1-demarcated microenvironments of heterochromatin required for KRAB zinc finger protein-mediated transcriptional repression. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8623–8638. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00487-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ZNF671 is hypermethylated in NPC. (A) Methylation levels of ZNF671 in Normal (n = 24) and NPC (n = 24) tissues from the genome-wide methylation microarray data. Mean ± ± SD; Student’s t-tests. (B) Bisulfite pyrosequencing analysis of the ZNF671 promoter region in NP69 and NPC (CNE1, CNE2, SUNE1, HONE1, HNE1, 5-8F and 6-10B) cell lines. Red words: CG site of cg11977686. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. control, Student’s t-test. (TIFF 831 kb)

ZNF671 is hypermethylated in NPC cells. Bisulfite pyrosequencing analysis of the ZNF671 promoter region in NP69 and NPC (CNE1, CNE2, SUNE1, HONE1, HNE1, 5-8F and 6-10B) cell lines following treatment with DAC. Red words: CG site of cg11977686. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. control, Student’s t-test. (TIFF 861 kb)

ZNF671 has no effect on affect NPC migratory and invasive ability. (A) Migration ability was measured using a wound healing assay (200 ×) and (B) Transwell assay with Matrigel (200 ×) in CNE2 and SUNE1 cells with the vector or ZNF671 overexpression. Scale bar: 100 μm; data are mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. control, Student’s t-test. (TIFF 1066 kb)