Abstract

Background

Antigen-negative red cell transfusion is required for transfusion-dependent patients. We developed multiplex PCR for red cell genotyping and calculated the possibility of finding compatible predicted phenotypes in Thai blood donor populations according to red cell alloantibodies found among Thai patients.

Methods

600 DNA samples obtained from unrelated healthy central and northern Thai blood donors were tested with the newly developed multiplex PCR for FY*A, FY*B, JK*A, JK*B, RHCE*e, RHCE*E, DI*A and GYP*Hut, GYP*Mur, GYP*Hop, GYP*Bun, and GYP*HF allele detections. Additionally, the possibility of finding compatible predicted phenotypes in two Thai blood donor populations was calculated to estimate the minimal number of tests needed to provide compatible blood.

Results

The validity of multiplex PCR using known DNA controls and the phenotyping and genotyping results obtained by serological and PCR-SSP techniques were in agreement. The possibility of finding at least one compatible blood unit for patients with multiple antibodies was comparable in Thai populations.

Conclusions

The multiplex PCR for red cell genotyping simultaneously interprets 7 alleles and 1 hybrid GP group. Similar strategies can be applied in other populations depending on alloantibody frequencies in transfusion-dependent patients, especially in a country with limited resources.

Keywords: Multiplex PCR, Red cell genotyping, Transfusion-dependent patients, Thais

Introduction

The International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT) Working Party on Red Cell Immunogenetics and Terminology assigned 346 blood group antigens, of which 308 are clustered within 36 blood group systems [1]. Alloantibodies can occur after transfusion or pregnancy if the patient is lacking the corresponding red cell antigens. Clinically significant alloantibodies play a critical role in transfusion medicine by causing either acute or delayed hemolytic transfusion reactions (HTRs) and hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDFN) ranging from mild to severe grades [2,3,4,5].

Frequencies of red cell alloantibody specificities among transfusion-dependent patients vary depending on blood group antigen distribution as well as racial and ethnic differences [6,7,8,9,10]. In Thailand, the prevalence of patients with thalassemia is high. Regarding the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Thalassemia, the antigen typing of Rh (C, c, E, e) and MNS hybrid glycophorins (GPs), especially in MNS7 (Mia), is minimally required before the first transfusion. Red cell antigen typing of other Kidd, Duffy, Kell, MNS, Lewis and P1PK systems is beneficial to predict antibody specificities in patients with multiple antibodies [11]. In the meantime, antigen typing to provide phenotype-matched donors is implemented to reduce alloimmunization or HTRs [2,3].

Classic serological techniques are used to type several red cell antigens [2]. To overcome some serology limitations, the application of molecular techniques for blood group polymorphisms can make predicting blood group phenotypes possible [12,13]. At present, individual red cell genotyping for MNS hybrid GPs as well as the Kidd, Duffy and Diego blood group systems using polymerase chain reaction with sequence-specific primers (PCR-SSP), has successfully been performed in Thai blood donors [14,15,16,17]. Concerning a previous study in multitransfused Thai patients requiring blood transfusions, the identified antibody specificity results could be divided in two groups: single antibody (52.4%) and multiple antibodies (47.6%) [18]. Hence, the individual testing of each blood group system in cases of multiple antibodies requires test steps and becomes more time-consuming than using multiplex PCR genotyping. A recent application of multiplex PCR for red cell genotyping demonstrated that this technique could offer rapid and reproducible genotyping results for 35 red cell antigens [19]. Therefore, this study aimed to develop multiplex PCR for red cell genotyping compared with individual PCR testing and to calculate the possibility of finding compatible predicted phenotypes among Thai blood donor populations according to alloantibodies found among Thai patients.

Material and Methods

Subjects

600 DNA samples obtained from unrelated healthy Thai blood donors were included in this study. 300 samples of central Thai blood donors were from the National Blood Centre, Thai Red Cross Society, Bangkok, and 300 samples of northern Thai blood donors were from the Blood Bank, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject. This study was approved by the Committee on Human Rights Related to Research Involving Human Subjects, Thammasat University, Pathumtani, Thailand.

300 DNA samples of central Thais were phenotyped for Fya, Fyb, Jka, Jkb, E, and e antigens using gel technique (Bio-Rad, Morat, Switzerland). The Dia and Mia were typed using human anti-Dia (CE-Immundiagnostika GmbH, Eschelbronn, Germany) and human anti-Mia (National Blood Centre, Thai Red Cross Society, Bangkok, Thailand) by conventional tube technique. Moreover, these 300 DNA samples were genotyped for Duffy, Kidd, Rh E/e, Diego, and MNS hybrid GPs by PCR-SSP [14,15,16,17]. All samples were genotyped using newly developed multiplex PCR. In addition, 300 unknown phenotypes and genotypes of northern Thais were also genotyped by multiplex PCR.

DNA Controls

12 known DNA samples consisting of different phenotypes of Duffy, Kidd, Rh E/e, and Diego blood group antigens and MNS hybrid GPs, confirmed by DNA sequencing, were used as controls. In addition, 2 DNA samples from Fy(a-b-) phenotypes of FY*02N.01 (c.1–67T>C) and 1 DNA sample from Jk(a-b-) phenotypes of JK*02N.01 (c.342-1g>a) were also included.

Primers

Sequences of the primer combinations used in the two primer mixtures (MIX A and MIX B), the allele detected, the product size, and the specific antigens of each mixture are shown in table 1. Primers were designed by NCBI software. Regarding the results from alloantibodies found among Thai patients, the following eight allele detections were available using the two primer mixtures: MIX A included FY*A, JK*A, RHCE*e, and DI*A allele detections predicting Fya, Jka, e, and Dia antigens; MIX B included FY*B, JK*B, RHCE*E and GYP*Hut, GYP*Mur, GYP*Hop, GYP*Bun, and GYP*HF allele detections predicting Fyb, Jkb, E antigens and GP.Hut, GP.Mur, GP.Hop, GP.Bun, and GP.HF. Moreover, Jka, Dia and MNS hybrid GPs primers were identical to those previously described [14,15,16,17] while other primers were newly designed. All primers were tested for their specificities with known DNA for each genotype.

Table 1.

Primers sequences of two reaction mixtures and product sizes used in the multiplex PCR for red cell genotyping

| Primer name | Target allele | Sequences (5’→3’) | Product size, bp | Concentration of primer in multiplex, µmol/l | Specific antigen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mix A | |||||

| FY-AB-Forward | CTCATTAGTCCTTGGCTCTTAT | 0.4 | |||

| FY-A-Reverse | FY*A | AGCTGCTTCCAGGTTGGCCC | 711 | 0.4 | Fya |

| JK-AB-Forward [15] | CATGCTGCCATAGGATCATTGC | 0.4 | |||

| JK-A-Reverse [15] | JK*A | CCAGAGTCCAAAGTAGATGTC | 301 | 0.4 | Jka |

| RH-e-Forward | TGTTCTGGCCAAGTGTCAACTCAG | 0.4 | |||

| RH-CE-Reverse | RHCE*e | GTGTGCTAGTCCTGTTAGACCC | 202 | 0.4 | e |

| DI-AB-Forward [17] | GGTGTGATAGGCACTGACCC | 0.4 | |||

| DI-A-Reverse [17] | DI*A | GGGCCAGGGAGGCCA | 130 | 0.4 | Dia |

| Mix B | |||||

| FY-AB-Forward | CTCATTAGTCCTTGGCTCTTAT | 0.4 | |||

| FY-B-Reverse | FY*B | AGCTGCTTCCAGGTTGGCCT | 711 | 0.4 | Fyb |

| JK-AB-Forward | CATGCTGCCATAGGATCATTGC | 0.4 | |||

| JK-B-Reverse | JK*B | CCAGAGTCCAAAGTAGATGTT | 301 | 0.4 | Jkb |

| RH-E-Forward | TGTTCTGGCCAAGTGTCAACTCTC | 0.2 | |||

| RH-CE-Reverse | RHCE*E | GTGTGCTAGTCCTGTTAGACCC | 202 | 0.2 | E |

| MNS-Hybrids-Forward [14] | GYP*Hut, GYP*Mur, GYP*Hop | CCCTTTCTCAACTTCTCTTATATGCAGATAA | 0.4 | GP.Hut, GP.Mur | |

| MNS-Hybrids-Reverse [17] | GYP*Bun and GYP*HF | GAGCAACTATTTAAAACTAAGAACATACCGG | 148,151* | 0.4 | GP.Hop, GP.Bun and GP.HF |

| Internal control | |||||

| HGH-Forward | TGCCTTCCCAACCATTCCCTTA | 0.4 | |||

| HGH-Reverse | HGH | CCACTCACGGATTTCTGTTGTGTTTC | 434 | 0.4 | |

148 bp were product of GP.Mur, GP.Hop and GP.Bun; 151 bp were product of GP.Hut and GP.HF.

PCR-SSP of Each Red Cell Genotyping

The PCR conditions of each red cell genotyping are described as follows.

Regarding the individual genotyping of Duffy, Kidd and Diego blood group systems and MNS hybrid GPs by the PCR-SSP technique, the primers and PCR conditions were identical to previous reports [14,15,16,17].

The primers of Rh E/e genotyping were newly designed (table 1). Individual tests for Rh E/e genotyping included two PCR reaction mixtures. For each PCR reaction, 1 µl of genomic DNA (50 ng/µl) was amplified in a total volume of 10 µl using 1 µl of 10 µmol/l forward primers and 1 µl of 10 µmol/l reverse primers. In addition, co-amplification of the human growth hormone (HGH) gene using 1 µl of 10 µmol/l HGH-forward primer and 1 µl of 10 µmol/l HGH-reverse primer was run as the internal control. PCR was performed with 5 µl of PCR reaction mixture (OnePCR Plus, GeneDireX Inc., Taipei, Taiwan) in a T100 Thermal cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). The cycling parameters for the PCR program consisted of 1 cycle at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, 61 °C for 40 s, and 72 °C for 30 s with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. Thereafter, PCR products were electrophoresed at 100 V with 1.5% agarose gel using 1X Tris borate ethylenediaminetetraacetate (TBE) buffer and visualized under blue-light transilluminator.

DNA Sequencing

Genomic DNA of randomly repeated 30 samples was sequenced to confirm the multiplex PCR results. Fragments of 931, 430, 560, 598 and 882 bps were obtained from PCR amplification of FY, JK, RHCE, DI and GYP target genes, respectively. The amplified FY gene fragment contained both single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs (c.1–67T>C and c.125G>A); while the amplified gene fragments of JK, RHCE and DI contained SNPs c.838G>A, c.676G>C and c.2561C>T, respectively. In addition, the amplified GYP hybrid fragment contained the GP hybrid genes of GYP*Hut, GYP*Mur, GYP*Hop, GYP*Bun, and GYP*HF.

Each gene target of PCR amplification for DNA sequencing was similar to PCR mixtures and conditions. Sequences of primer pairs of each gene target are shown in table 2. For each PCR reaction, 2 µl of genomic DNA (50 ng/µl) was amplified in a total volume of 50 µl using 1 µl of 10 µmol/l forward primers and 1 µl of 10 µmol/l reverse primer for each reaction. The PCR was performed with 25 µl of 2X PCR reaction mixture (Phusion High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix; New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and 21 µl of sterile distilled water in T100 Thermal cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

Table 2.

Primers sequences and product sizes used in the DNA sequencing

| Primer name | Target gene | Sequences (5’→3’) | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duffy | |||

| SE-FY-Forward | GTGTAGTCCCAACCAGCCAA | ||

| SE-FY-Reverse | FY | AGGATACCCAGGACACTGGT | 931 |

| Kidd | |||

| JK-AB-Forward | CATGCTGCCATAGGATCATTGC | ||

| SE-JK-Reverse | JK | TAGTCATGAGCAGCCCTCCCC | 430 |

| Rh E/e | |||

| SE-RHCE-Forward | AGAGCTCCACTGTAGAGGCA | ||

| SE-RHCE-Reverse | RHCE | TCACAGAGCAGGTTCAGGAG | 560 |

| Diego | |||

| SE-DI-Forward | TTAGGGGTCCAGCTCACTCA | ||

| SE-DI-Reverse | DI | TGACCGCATCTTGCTTCTGT | 598 |

| MNS-hybrid glycophorins | |||

| SE-MNS-hybrid-Forward | CAGCATTTCTCTAAAGGCTAAATAAGAAGATGTA | ||

| SE-MNS-hybrid-Reverse | GYP | CTGATTTATGCCATAGCCACTGTA | 882 |

PCR was performed under the conditions described below, starting with 94 °C for 2 min (initial denaturation). The cycle parameters of the PCR program began with the first step of 10 cycles of 10 s at 94 °C and 60 s at 69 °C followed by 20 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 60 s at 62 °C and 30 s at 72 °C. The last step was a final extension for 5 min at 72 °C. PCR products were electrophoresed at 100 V with a 1.5% agarose gel containing 10,000X fluorescent DNA gel stain (SYBR Safe DNA gel stain, Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) using 1X TBE buffer. Products were visualized under a blue-light transilluminator. Thereafter, the PCR products were purified using the gel extraction kit (Real genomics HiYield Gel/PCR DNA Extraction Kit; RBCBioscience, Taipei, Taiwan), and eluted fragments were then sequenced (1st BASE DNA Sequencing Services, Selangor, Malaysia) using those PCR primers.

Red Cell Genotyping by Multiplex PCR

The multiplex PCR for red cell genotyping contained two reaction mixes (A and B) of each different amplification target for each mix, as shown in table 1. Each reaction mix contained four-specific primer pairs, and one HGH-specific primer pair was used as the internal control. The PCR reaction mixtures consisted of 12.5 µl of the 2X PCR reaction mixture (Green Hot Start PCR Master Mix, Biotechrabbit GmbH, Hennigsdorf, Germany), 1 µl (50–150 ng) of genomic DNA, 1 µl of each blood group-specific primer (MIX A: FY-AB-Forward and FY-A-Reverse, JK-AB-Forward and JK-A-Reverse, RH-e-Forward and RH-CE-Reverse as well as DI-AB-Forward and DI-A-Reverse; MIX B: FY-AB-Forward and FY-B-Reverse, JK-AB-Forward and JK-B-Reverse, RH-E-Forward and RH-CE-Reverse as well as MNS-hybrids-Forward and MNS-hybrids-Reverse), 1 µl of HGH primers (HGH-Forward and HGH-Reverse) and 1.5 µl of PCR grade water in a final volume of 25 µl. The final concentrations of each primer used for multiplex PCR are shown in table 1.

PCR amplification of two multiplex sets was performed in a T100 Thermal cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The cycling parameters for the PCR program consisted of 1 cycle at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, 61 °C for 40 s, 72 °C for 30 s, with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products were electrophoresed at 100 V with a 1.5% agarose gel containing 10,000X fluorescent DNA gel stain (SYBR Safe DNA gel stain) using 1X TBE buffer. Products were visualized under a blue-light transilluminator.

To increase the validity and reliability of the evaluation, the technicians were blinded from the PCR-SSP results. In the case of any discrepant results of genotyping obtained by multiplex PCR and PCR-SSP, DNA sequencing was performed.

DNA Sequencing

The primers and PCR conditions of DNA sequencing in each gene target are described above (see ‘DNA Sequencing’).

Statistical Analysis

Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and accuracy of the newly developed multiplex PCR technique were calculated and compared with PCR-SSP techniques. The sensitivity of the multiplex PCR was tested using all known allele samples with concentrations ranging from 10 to 300 ng/µl. In addition, 30 samples were randomly repeated for genotyping using the multiplex PCR technique to test reproducibility, and all samples were sequenced to confirm the results of multiplex PCR. Genotype frequencies were calculated using the gene-counting method and computed to predict phenotypes. The differences in predicted phenotypes between the two groups were compared using the chi-square test. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The possibility of finding compatible predicted phenotypes in Thai blood donor populations according to developed alloantibodies among transfusion-dependent Thai patients was calculated to estimate the minimal number of tests needed to provide compatible blood [20].

The number of testing unit(s) required to find at least one compatible unit was calculated as shown below.

Testing numbers = 1 / (frequencies of corresponding antigen-negative donor predicted phenotype among Thai populations (%) / 100).

Results

Red Cell Genotyping by Multiplex PCR

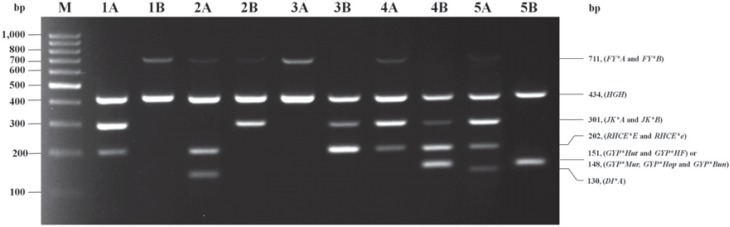

The results of a two-tube multiplex PCR were used to distinguish seven alleles and one group of MNS hybrid GPs. Multiplex MIX A could differentiate FY*A, JK*A, RHCE*e, and DI*A alleles with the amplified PCR product sizes of 711, 301, 202, and 130 bps. Moreover, multiplex MIX B could differentiate FY*B, JK*B, RHCE*E alleles and hybrid GPs of GYP*Hut, GYP*Mur, GYP*Hop, GYP*Bun, and GYP*HF with amplified PCR product sizes of 711, 301, 202, and 151 (GYP*Hut and GYP*HF) or 148 (GYP*Mur, GYP*Hop and GYP*Bun) bps. In each multiplex set, the HGH internal control presented an expected band of 434 bp, showing that PCR amplification had occurred optimally. These genotyping results by in-house multiplex PCR are shown in figure 1.

Fig. 1.

A representative gel showing red cell genotyping by multiplex PCR. Each of two reaction mixes (MIX A and MIX B) is designed to five alleles. The 434 bp amplification product of the HGH control primer is present in all lanes. The genotype was deduced from the presence or absence of amplification products specific for each RBC allele indicated on the right border. Lane M: DNA ladder marker (GeneRuler 100 bp; Fermentas, Carlsbad, CA, USA); The predicted phenotypes of Lane 1A to Lane 1B: Fy(a-b+), Jk(a+b-), ee, Di(a-) and Mi(a-); Lane 2A to 2B: Fy(a+b+), Jk(a-b+), ee, Di(a+) and Mi(a-); Lane 3A to 3B: Fy(a+b-), Jk(a-b+), EE, Di(a-) and Mi(a-); Lane 4A to 4B: Fy(a+b-), Jk(a+b+), Ee, Di(a-) and Mi(a+); Lane 5A to 5B: Fy(a+b-), Jk(a+b-), ee, Di(a+) and Mi(a+).

Validation of Multiplex PCR

Regarding in-house multiplex PCR for red cell genotyping, distinguishing seven alleles and one group of MNS hybrid GPs, validation verified the multiplex amplicons using known DNA controls, and a non-template control (water) served for contamination. The validated genotyping results of 12 DNA controls were in agreement. Moreover, multiplex PCR was performed using 300 DNA samples of central Thais, and each corresponding multiplex amplicon concurred with phenotyping and genotyping results obtained by serological and PCR-SSP techniques. Therefore, multiplex PCR had sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values as well as accuracy of 100%. To test the developed multiplex PCR for reproducibility regarding the presence or absence amplicons and DNA sequencing, multiplex PCR was performed on 30 randomly repeated DNA samples. The results from all samples were similar to those of the first round of testing. In addition, the sensitivity of the multiplex system was evaluated using positive and negative DNA controls, and multiplex PCR with identical PCR conditions was performed on ranging DNA concentrations from 10 to 300 ng/µl. Specific amplicons could accurately be identified up to an initial DNA concentration of 20 ng/µl.

Frequencies of Predicted Phenotypes by Multiplex PCR in Two Thai Blood Donor Populations

The validated multiplex PCR for red cell genotyping was implemented among 300 unknown DNA samples from northern Thais, and the genotyping results were computed to predicted phenotypes, as shown in table 3. A total of 600 Thai blood donors were genotyped for the presence of predicted phenotypes from Duffy, Kidd, Rh E/e, and Diego blood group systems as well as MNS hybrid GPs. The details of genotypes and predicted phenotypes are shown in table 3. For the Duffy blood group system, Fy(a+b-) was the most common predicted phenotype observed among central and northern Thais (86.3% and 87.7%), and no Fy(a-b-) was observed. Notably, only one central Thai donor exhibited the Fy(a-b+) phenotype. For the Kidd blood group system, Jk(a+b+) was the most common predicted phenotype among central and northern Thais (44.7% and 49.7%). For the Rh blood group system, the ee phenotype was the most common among central and northern Thais (65.7% and 69.3%). The Dia antigen was observed at 5.0% and 3.7% of central and northern Thais, respectively. In addition, the predicted phenotype of GP.Hut, GP.Mur, GP.Hop, GP.Bun, and GP.HF was significantly higher among northern Thais (22.3%) than among central Thais (9.3%).

Table 3.

Frequencies of predicted phenotypes by multiplex PCR in two Thai populations

| Genotype | Predicted phenotype | Central Thais |

Northern Thais |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | ||

| Duffy blood group | |||||

| FY*A/FY*A | Fy(a+b–) | 259/300 | 86.3 | 263/300 | 87.7 |

| FY*A/FY*B | Fy(a+b+) | 40/300 | 13.3 | 37/300 | 12.3 |

| FY*B/FY*B | Fy(a–b+) | 1/300 | 0.3 | 0/300 | 0.0 |

| FY*02N.01/FY*02N.01 | Fy(a–b–) | 0/300 | 0.0 | 0/300 | 0.0 |

| Kidd blood group | |||||

| JK*A/JK*A | Jk(a+b–) | 83/300 | 27.7 | 75/300 | 25.0 |

| JK*A/JK*B | Jk(a+b+) | 134/300 | 44.7 | 149/300 | 49.7 |

| JK*B/JK*B | Jk(a–b+) | 83/300 | 27.7 | 76/300 | 25.3 |

| Rh blood group | |||||

| RHCE*E/RHCE*E | EE | 10/300 | 3.3 | 6/300 | 2.0 |

| RHCE*E/RHCE*e | Ee | 93/300 | 31.0 | 86/300 | 28.7 |

| RHCE*e/RHCE*e | ee | 197/300 | 65.7 | 208/300 | 69.3 |

| Diego blood group | |||||

| DI*A | Di(a+) | 15/300 | 5.0 | 11/300 | 3.7 |

| Di(a–) | 285/300 | 95.0 | 289/300 | 96.3 | |

| MNS hybrid glycophorins | |||||

| GYP*Hut, GYP*Mur, GYP*Hop, GYP*Bun and GYP*HF | GP.Hut, GP.Mur, GP.Hop, GP.Bun and GP.HF(+) | 28/300 | 9.3* | 67/300 | 22.3* |

| GP.Hut, GP.Mur, GP.Hop, GP.Bun and GP.HF(–) | 272/300 | 90.7* | 233/300 | 77.7* | |

p < 0.001.

The Possibility of Finding Compatible Phenotype Blood for Patients in Thai Populations

According to the alloantibodies found in transfusion-dependent Thai patients, the possibility of finding compatible blood units was calculated from frequencies of predicted phenotypes in two Thai populations (table 4). For example, considering patients with anti-Fya development, the odds of finding one compatible blood unit using the predicted Fy(a-b+) phenotype among Thais was estimated. The testing numbers of one compatible unit were 300 units and more than 300 units among central and northern Thai donors. Alternatively, the chance of finding at least one compatible blood unit for a patient with multiple antibodies was calculated. When a patient had anti-e + anti-Jka, the EE and Jk(a-b+) phenotypes would be needed. Hence, the frequencies of corresponding compatible donors were calculated as 3.3% × 27.7% for central Thais and 2.0% × 25.3% for northern Thais. The testing numbers for one compatible unit were 109 and 198, respectively. Similar calculations were performed for other alloantibodies found in Thai populations (table 4).

Table 4.

The possibility of finding compatible donors in two Thai blood populations according to alloantibodies in transfusion-dependent Thai patients

| Alloantibodies in Thai patients [18] | Frequencies of compatible donor, % |

Testing numbers of finding at least one compatible unit |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Thais | Northern Thais | Central Thais | Northern Thais | |

| Single antibody | ||||

| Anti-Mia | 90.7 | 77.7 | 2 | 2 |

| Anti-E | 65.7 | 69.3 | 2 | 2 |

| Anti-Jka | 27.7 | 25.3 | 4 | 4 |

| Anti-Jkb | 27.7 | 25.0 | 4 | 4 |

| Anti-Dia | 95.0 | 96.3 | 2 | 2 |

| Anti-Fyb | 86.3 | 87.7 | 2 | 2 |

| Anti-e | 3.3 | 2.0 | 31 | 50 |

| Anti-Fya | 0.3 | 0.0 | 300 | >300* |

| Multiple antibodies | ||||

| Two antibodies | ||||

| Anti-E + anti-Mia | 65.7 + 90.7 | 69.3 + 77.7 | 2 | 2 |

| Anti-E + anti-Jka | 65.7 + 27.7 | 69.3 + 25.3 | 6 | 6 |

| Anti-Jka + anti-Mia | 27.7 + 90.7 | 25.3 + 77.7 | 4 | 5 |

| Anti-E + anti-Jkb | 65.7 + 27.7 | 69.3 + 25.0 | 6 | 6 |

| Anti-Fyb + anti-Mia | 86.3 + 90.7 | 87.7 + 77.7 | 2 | 2 |

| Anti-E + anti-Fyb | 65.7 + 86.3 | 69.3 + 87.7 | 3 | 2 |

| Anti-Jkb + anti-Mia | 27.7 + 90.7 | 25.0 + 77.7 | 4 | 6 |

| Anti-e + anti-Mia | 3.3 + 90.7 | 2.0 + 77.7 | 34 | 65 |

| Anti-E + anti-Dia | 65.7 + 95.0 | 69.3 + 96.3 | 2 | 2 |

| Anti-Dia + anti-Mia | 95.0 + 90.7 | 96.3 + 77.7 | 2 | 2 |

| Anti-e + anti-Jka | 3.3 + 27.7 | 2.0 + 25.3 | 109 | 198 |

| Three antibodies | ||||

| Anti-E + anti-Mia + anti-Jka | 65.7 + 90.7 + 27.7 | 69.3 + 77.7 + 25.3 | 7 | 8 |

| Anti-E + anti-Mia + anti-Fyb | 65.7 + 90.7 + 86.3 | 69.3 + 77.7 + 87.7 | 3 | 3 |

| Anti-E + anti-Mia + anti-Jkb | 65.7 + 90.7 + 27.7 | 69.3 + 77.7 + 25.0 | 7 | 8 |

| Anti-E + anti-Mia + anti-Dia | 65.7 + 90.7 + 95.0 | 69.3 + 77.7 + 96.3 | 2 | 2 |

| Anti-Jka + anti-Mia + anti-Fyb | 27.7 + 90.7 + 86.3 | 25.3 + 77.7 + 87.7 | 8 | 6 |

Fy(a-b+) phenotype was not found in 300 Northern Thais.

Discussion

Various techniques in determining the genetic basis of blood group polymorphisms are used as a complementary tool to overcome problematic cases, especially in transfusion-dependent patients. Selection of molecular techniques depends on the sensitivity and specificity of each technique, equipment, cost, test time, and throughputs. Commercially available high-throughput genotyping techniques such as BioArray Human Erythrocyte Antigen (HEA) BeadChip, BLOODchip Reference, and ID CORE XT have been introduced in the area of blood group genotyping with several designs and platforms [21,22,23] but are not suitable for a country with limited resources. The multiplex PCR technique can be used as an alternative for routine blood bank laboratory implementation because of its suitability to simultaneously detect several blood group alleles while keeping cost competitive [24]. The multiplex PCR technique has successfully been developed to detect 35 red cell antigens among Austrian blood donors containing six reaction mixes [19]. This type of multiplex PCR has been found inappropriate with clinically significant red cell antigens in Thai and other populations. In this study, we developed the two-tube multiplex PCR to detect red cell antigens according to common alloantibodies found among Thai patients. A similar strategy to develop in-house multiplex PCR could be successfully implemented in other countries.

Test validity and reproducibility of the developed multiplex PCR revealed high fidelity based on 100% concordance between the phenotyping and genotyping results of 300 donor samples. Interestingly, this technique could determine a predicted Fy(a-b-) phenotype associated with homozygous FY*02N.01 (c.1–67T>C), when the bands of 711 bps in both mixtures were not demonstrated. On the other hand, several types of homozygosity for a silent gene at the Kidd locus resulting in the null Jk(a-b-) phenotype could not differentiate the identified JK*A- and JK*B-carrying mutations using this multiplex PCR. As a result, we suggested that Jk(a-b-) phenotype screening by the direct urea lysis test should be used for mass screening among blood donors which could be performed in parallel with multiplex PCR [25]. Both Fy(a-b-) and Jk(a-b-) phenotypes were remarkably rare among Thai and other populations [4]. Even though the occurrence of the MNS7 phenotype is associated with GP.Hut, GP.Mur, GP.Hop, GP.Bun, GP.HF and GP.Vw, we did not include GYP*Vw detection because the prevalence of GP.Vw is less common in populations [4,14].

Following the implementation of the multiplex PCR in two Thai populations, the genotyping results could be computed for predicted phenotypes, and those results were compared. The frequencies of predicted phenotypes were almost comparable in Thai populations. Only the predicted phenotypes of GP.Hut, GP.Mur, GP.Hop, GP.Bun and GP.HF were significantly higher in northern Thais than in central Thais, similar to other studies among Thai, Asian and European populations [14,26]. Moreover, the Di(a+) phenotype has not commonly been included in commercial screening and panel cells because the prevalence is low, except in Asians of Mongoloid origin [4,27]. In this study, the prevalence of the Di(a+) antigen was high not only among Thais but also in other populations such as Southeast Asians, Brazilians, and American Natives [28,29]. Hence, to prevent an alloimmunization or delayed HTRs, DI*A allele detection should be included in the multiplex PCR.

Classic serological techniques for phenotyping are expensive, and some antisera are not marketed, e.g., anti-Mia. More time and higher costs are required to screen rare phenotypes among blood donors, especially in emergency situations. The application of multiplex PCR to type these patients before transfusion would be useful to reduce alloimmunization risks because clinically significant red cell antigens can be identified. Moreover, among patients with positive DAT who had multiple antibodies, extended genotyping is beneficial to confirm antibody specificities and to identify antigen-negative blood units. In this study, we found that the number of testing units for most patients with multiple antibodies did not exceed 10 units because antibody combinations were specific to high-frequency antigen-negative populations. Nevertheless, individual testing for each antigen may not be suitable to find antigen-negative blood units. The implementation of multiplex-PCR is beneficial for transfusion-dependent patients for the following reasons: i) The results can be obtained even with a low concentration of DNA (20 ng/µl) within 2 h. ii) Multiplex PCR uses fewer tubes and less reagents, and the cost is approximately Eur 4.00/test, which is 50% less than PCR-SSP, and similar to the application of multiplex PCR to detect other genetic polymorphisms [30,31]. iii) Its simplicity and reproducibility is proper for routine testing.

Multiplex PCR for red cell genotyping based on frequencies of alloantibodies in Thai populations simultaneously interprets seven alleles and one hybrid GP group with accurate and consequential typing results to identify compatible blood donors for transfusion-dependent patients. A similar strategy can be applied in other countries with limited resources.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in the subject matter of the manuscript. The authors did not receive any financial support in addition to the project grant mentioned.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grants of the Higher Education Research Promotion and National Research University Project of Thailand, Office of the Higher Education Commission. We thank Mr. Morakot Emthip, Histocompatibility and Immunogenetics Laboratory, National Blood Centre, Thai Red Cross Society for providing DNA controls.

References

- 1.Storry JR, Castilho L, Chen Q, Daniels G, Denomme G, Flegel WA, Gassner C, de Haas M, Hyland C, Keller M, Lomas-Francis C, Moulds JM, Nogues N, Olsson ML, Peyrard T, van der Schoot CE, Tani Y, Thornton N, Wagner F, Wendel S, Westhoff C, Yahalom V. International society of blood transfusion working party on red cell immunogenetics and terminology: report of the Seoul and London meetings. ISBT Sci Ser. 2016;11:118–122. doi: 10.1111/voxs.12280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fung MK, Grossman BJ, Hillyer CD, Westhoff CM. Technical Manual. 18th ed. Bethesda: AABB; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poole J, Daniels G. Blood group antibodies and their significance in transfusion medicine. Transfus Med Rev. 2007;21:58–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reid M, Lomas-Francis C, Olsson ML. The Blood Group Antigen Factsbook. 3rd ed. New York: Elsevier; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniels G. Human Blood Groups. 3rd ed. Malden: Blackwell Science; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yazdanbakhsh K, Ware RE, Noizat-Pirenne F. Red blood cell alloimmunization in sickle cell disease: pathophysiology, risk factors, and transfusion management. Blood. 2012;120:528–537. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-327361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell-Lee SA, Kittles RA. Red blood cell alloimmunization in sickle cell disease: listen to your ancestors. Transfus Med Hemother. 2014;41:431–435. doi: 10.1159/000369513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elhence P, Solanki A, Verma A. Red blood cell antibodies in thalassemia patients in northern India: risk factors and literature review. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2014;30:301–308. doi: 10.1007/s12288-013-0311-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chao YH, Wu KH, Lu JJ, Shih MC, Peng CT, Chang CW. Red blood cell alloimmunisation among Chinese patients with β-thalassaemia major in Taiwan. Blood Transfus. 2013;11:71–74. doi: 10.2450/2012.0153-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rujirojindakul P, Flegel WA. Applying molecular immunohaematology to regularly transfused thalassaemic patients in Thailand. Blood Transfus. 2014;12:28–35. doi: 10.2450/2013.0058-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fucharoen S, Tanphaichitr VS, Torcharus K, Viprakasit V, Mekaewkunchorn A. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Thalassemia Syndromes (in Thai). Bangkok: P.A.Living; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guelsin GA, Sell AM, Castilho L, Masaki VL, Melo FC, Hashimoto MN, Higa TT, Hirle LS, Visentainer JE. Benefits of blood group genotyping in multi-transfused patients from the south of Brazil. J Clin Lab Anal. 2010;24:311–316. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peyrard T. Use of genomics for decision-making in transfusion medicine: laboratory practice. ISBT Sci Ser. 2013;8:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palacajornsuk P, Nathalang O, Tantimavanich S, Bejrachandra S, Reid ME. Detection of MNS hybrid molecules in the Thai population using PCR-SSP technique. Transfus Med. 2007;17:169–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2007.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Intharanut K, Grams R, Bejrachandra S, Sriwanitchrak P, Nathalang O. Improved allele-specific PCR technique for Kidd blood group genotyping. J Clin Lab Anal. 2013;27:53–58. doi: 10.1002/jcla.21561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nathalang O, Intharanut K, Siriphanthong K, Nathalang S, Kupatawintu P. Duffy blood group genotyping in Thai blood donors. Ann Lab Med. 2015;35:618–623. doi: 10.3343/alm.2015.35.6.618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nathalang O, Panichrum P, Intharanut K, Thattanon P, Nathalang S. Distribution of DI*A and DI*B allele frequencies and comparisons among Central Thai and Other populations. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0165134. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kupatawintu P, Emthip M, Sungnoon D, Ovataga P, Manakul V, Limtamaporn S, Tubrod J. Unexpected antibodies of patients, blood samples sent for testing at NBC. TRCS. (in Thai) J Hematol Transfus Med. 2010;20:255–262. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jungbauer C, Hobel CM, Schwartz DW, Mayr WR. High-throughput multiplex PCR genotyping for 35 red blood cell antigens in blood donors. Vox Sang. 2012;102:234–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2011.01542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lingerfelter B, Gibbs FG, Sosler SD. Detection and identification of antibodies. In: Harmening DM, editor. Modern Blood Banking and Transfusion Practices. Baltimore: F.A. Davis Company; 1999. pp. 263–264. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hashmi G, Shariff T, Zhang Y, Cristobal J, Chau C, Seul M, Vissavajjhala P, Baldwin C, Hue-Roye K, Charles-Pierre D, Lomas-Francis C, Reid ME. Determination of 24 minor red blood cell antigens for more than 2000 blood donors by high-throughput DNA analysis. Transfusion. 2007;47:736–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avent ND, Martinez A, Flegel WA, Olsson ML, Scott ML, Nogués N, Písăcka M, Daniels G, van der Schoot E, Muñiz-Diaz E, Madgett TE, Storry JR, Beiboer SH, Maaskant-van Wijk PA, von Zabern I, Jiménez E, Tejedor D, López M, Camacho E, Cheroutre G, Hacker A, Jinoch P, Svobodova I, de Haas M. The BloodGen project: toward mass-scale comprehensive genotyping of blood donors in the European Union and beyond. Transfusion. 2007;47((suppl 1)):40S–46S. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karpasitou K, Drago F, Crespiatico L, Paccapelo C, Truglio F, Frison S, Scalamogna M, Poli F. Blood group genotyping for Jk(a)/Jk(b), Fy(a)/Fy(b), S/s, K/k, Kp(a)/Kp(b), Js(a)/Js(b), Co(a)/Co(b), and Lu(a)/Lu(b) with microarray beads. Transfusion. 2008;48:505–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flegel WA, Wagner FF, Müller TH, Gassner C. Rh phenotype prediction by DNA typing and its application to practice. Transfus Med. 1998;8:281–302. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3148.1998.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deelert S, Thippayaboon P, Sriwai W, Sriwanitchrak P, Tubrod J, Kupatawintu P, Nathalang O. Jk(a-b-) phenotype screening by the urea lysis test in Thai blood donors. Blood Transfus. 2010;8:17–20. doi: 10.2450/2009.0104-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandanyingyong D, Pejrachandra S. Studies on the Miltenberger complex frequency in Thailand and family studies. Vox Sang. 1975;28:152–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1975.tb02753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Figueroa D. The Diego blood group system: a review. Immunohematology. 2013;29:73–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Novaretti MC, Ruiz AS, Dorlhiac-Llacer PE, Chamone DA. Application of real-time PCR and melting curve analysis in rapid Diego blood group genotyping. Immunohematology. 2010;26:66–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delaney M, Harris S, Haile A, Johnsen J, Teramura G, Nelson K. Red blood cell antigen genotype analysis for 9087 Asian, Asian American, and Native American blood donors. Transfusion. 2015;55:2369–2375. doi: 10.1111/trf.13163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kengkate M, Butthep P, Kupatawintu P, Kanunthong S, Chantratita W, Nathalang O. Genotyping of HPA-1 to -7 and -15 in the Thai population using multiplex PCR. Transfus Med. 2012;22:272–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2012.01153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nathalang O, Intharanut K, Siriphanthong K, Sasikarn W, Nathalang S. Development of a Multiplex PCR for Human Neutrophil Antigens-1, -3, -4 and -5 Genotyping among Thai Blood Donors. Clin Lab. 2016;62:2227–2232. doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2016.160432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]