Key Points

Question

How often do youth with opioid use disorder receive buprenorphine or naltrexone, and how has this changed over time?

Findings

In this large, national retrospective cohort of 20 822 youth aged 13 to 25 years with opioid use disorder, medication receipt increased from 2001 to 2014, but only 1 in 4 individuals received buprenorphine or naltrexone. Younger individuals, females, and black and Hispanic youth were less likely to receive a medication.

Meaning

Amidst emerging recommendations calling for expanded access to pharmacotherapy for youth with opioid use disorder, medications may have been historically underutilized and disparities may exist by age, sex, and race/ethnicity.

Abstract

Importance

Opioid use disorder (OUD) frequently begins in adolescence and young adulthood. Intervening early with pharmacotherapy is recommended by major professional organizations. No prior national studies have examined the extent to which adolescents and young adults (collectively termed youth) with OUD receive pharmacotherapy.

Objective

To identify time trends and disparities in receipt of buprenorphine and naltrexone among youth with OUD in the United States.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using deidentified data from a national commercial insurance database. Enrollment and complete health insurance claims of 9.7 million youth, aged 13 to 25 years were analyzed, identifying individuals who received a diagnosis of OUD between January 1, 2001, and June 30, 2014, with final follow-up date December 31, 2014. Analysis was conducted from April 25 to December 31, 2016. Time trends were identified and multivariable logistic regression was used to determine sociodemographic factors associated with medication receipt.

Exposures

Sex, age, race/ethnicity, neighborhood education and poverty levels, geographic region, census region, and year of diagnosis.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Dispensing of a medication (buprenorphine or naltrexone) within 6 months of first receiving an OUD diagnosis.

Results

Among 20 822 youth diagnosed with OUD (0.2% of the 9.7 million sample), 13 698 (65.8%) were male and 17 119 (82.2%) were non-Hispanic white. Mean (SD) age was 21.0 (2.5) years at the first observed diagnosis. The diagnosis rate of OUD increased nearly 6-fold from 2001 to 2014 (from 0.26 per 100 000 person-years to 1.51 per 100 000 person-years). Overall, 5580 (26.8%) youth were dispensed a medication within 6 months of diagnosis, with 4976 (89.2%) of medication-treated youth receiving buprenorphine and 604 (10.8%) receiving naltrexone. Medication receipt increased more than 10-fold, from 3.0% in 2002 (when buprenorphine was introduced) to 31.8% in 2009, but declined in subsequent years (27.5% in 2014). In multivariable analyses, younger individuals were less likely to receive medications, with adjusted probability for age 13 to 15 years, 1.4% (95% CI, 0.4%-2.3%); 16 to 17 years, 9.7% (95% CI, 8.4%-11.1%); 18 to 20 years, 22.0% (95% CI, 21.0%-23.0%); and 21 to 25 years, 30.5% (95% CI, 30.0%-31.5%) (P < .001 for difference). Females (7124 [20.3%]) were less likely than males (13 698 [24.4%]) to receive medications (P < .001), as were non-Hispanic black (105 [14.8%]) and Hispanic (1165 [20.0%]) youth compared with non-Hispanic white (17 119 [23.1%]) youth (P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this first national study of buprenorphine and naltrexone receipt among youth, dispensing increased over time. Nonetheless, only 1 in 4 commercially insured youth with OUD received pharmacotherapy, and disparities based on sex, age, and race/ethnicity were observed.

This population study examines the use of buprenorphine and naltrexone among youth aged 13 to 25 years with opioid use disorder.

Introduction

Drug overdose deaths in the United States—the majority of which are caused by prescription opioids and heroin—have reached an unprecedented level, having tripled from 2000 to 2014 and surpassed annual mortality from motor vehicle crashes. Hospitalizations and emergency department visits for overdose, drug treatment admissions, and new hepatitis C infections related to opioids have risen dramatically over a similar timeframe. Risk for opioid use disorder (OUD) frequently begins in adolescence and young adulthood, with 7.8% of high school seniors reporting lifetime nonmedical prescription opioid use. Two-thirds of individuals in treatment for OUD report that their first use was before age 25 years, and one-third report that it was before 18 years. Intervening early in the development of OUD is critical for preventing premature death and lifelong harm. However, only 1 in 12 adolescents and young adults (collectively termed youth) who need care for any type of addiction receive treatment. Compounding this situation, black and Hispanic youth are even less likely than white youth to receive addiction treatment.

Buprenorphine, a partial opioid agonist, and naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, prevent relapse and overdose among youth with OUD. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved buprenorphine for adolescents (≥16 years) in 2003. Oral naltrexone has been FDA-approved for adults (≥18 years) since 1984, and the FDA approved a long-acting injectable formulation in 2010. Unlike methadone, both buprenorphine and naltrexone can be offered in primary care and subspecialty settings in the United States. However, there is a widespread shortage of physicians who have received the waiver certification required to prescribe buprenorphine and, of all physicians who are certified in the United States, only 1% are pediatricians. Naltrexone does not require special prescriber certification and is not an opioid agonist, and thus may be viewed more favorably by some physicians; nonetheless, it has historically been less commonly prescribed for adults than buprenorphine. Despite the much earlier documented efficacy and FDA approval of buprenorphine and naltrexone, the American Academy of Pediatrics did not release a policy statement calling for the use of pharmacotherapy for youth with OUD until August 2016. The absence of such a statement may have delayed adoption of pharmacotherapy by pediatricians, even despite preexisting recommendations from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and amidst a worsening youth opioid epidemic.

We know of no large-scale studies to date that have examined what percentage of youth with OUD receive pharmacotherapy. Understanding which youth receive medications, which medication (buprenorphine or naltrexone) they receive, and how medication dispensing varies by sociodemographic characteristics is critical to inform the expansion of addiction treatment services, which is a national priority in the United States. We identified trends and disparities in pharmacotherapy for youth during a time of escalating prevalence of OUD.

Methods

Data Source

We used deidentified Optum data (OptumInsight), which contain enrollment records and all inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, and pharmacy claims from a large US commercial health insurer with members in all 50 states and Washington, DC. All members in the data set had prescription drug coverage. The Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institutional Review Board approved the study with waiver of informed consent.

Sample Selection

The primary analytic sample included all youth aged 13 to 25 years who received a diagnosis of OUD between January 1, 2001, and June 30, 2014, with 6 months or more of continuous enrollment following the date of diagnosis (allowing a final date of follow-up of December 31, 2014). We included young adults up to age 25 years, since they often still receive care from pediatric providers, are included in national definitions of youth, and provide a young adult comparison group for adolescents. Consistent with prior research, enrollees were defined as having received a diagnosis of OUD if a claim was filed with a primary or secondary International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis code of 304.0x (opioid type dependence) or 304.7x (combinations of opioid type drug with any other drug dependence) in 1 or more inpatient or emergency department claims or 2 or more outpatient claims. The date of OUD diagnosis was the date of the first qualifying claim.

Variables of Interest

Our primary outcome of interest was receipt of buprenorphine (formulated as buprenorphine or buprenorphine-naloxone combination) or naltrexone (in its oral short-acting or intramuscular extended-release formulation) within 6 months of the first observed OUD diagnosis. Although clinical practice guidelines recommend considering pharmacotherapy as soon as possible after OUD diagnosis, we examined a 6-month timeframe to allow for any delay in linking youth to treatment services. We identified pharmacy claims that included a National Drug Code for buprenorphine (excluding the transdermal buprenorphine patch marketed exclusively for pain control) or naltrexone (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Since intramuscular extended-release naltrexone is often administered in health care settings (rather than being prescribed), an individual was also considered to have received naltrexone if a claim contained Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code J2315 (naltrexone, depot form). Each individual was labeled with a unique identifier and was included in the analytic sample only once at the time of the first observed diagnosis.

Covariates of interest included sex, age at OUD diagnosis, race/ethnicity, geographic region (ie, metropolitan vs nonmetropolitan), neighborhood educational level, and neighborhood poverty level, using previously established cutoff levels. To identify race/ethnicity, we used a combination of 2000 US Census neighborhood characteristics and surname analysis, which is a validated approach with high positive predictive value.

Statistical Analysis

Using the entire sample of 13- to 25-year-old youth with 6 or more months of continuous enrollment, we calculated annual diagnosis rates (ie, number of first observed diagnoses of OUD in a year divided by total person-years contributed) according to age group (13-15, 16-17, 18-20, and 21-25 years).

For all subsequent analyses, we limited the sample to youth who had received an OUD diagnosis. We then identified the proportion of youth who received buprenorphine or naltrexone within 6 months of the diagnosis. Among youth who received pharmacotherapy, we examined linear time trends in receipt of buprenorphine compared with naltrexone, introducing splines with 2 knots defined a priori corresponding to the FDA approval of buprenorphine and buprenorphine-naltrexone in October 2002, and of intramuscular extended-release naltrexone in October 2010. We then identified differences between youth who received buprenorphine compared with naltrexone. Where cell counts were less than 10, categories were excluded or collapsed together to protect confidentiality.

To compare characteristics of youth who did and did not receive pharmacotherapy, we used logistic regression to identify associations between study covariates and medication receipt. We subsequently generated a multivariable model including all study covariates, given the known association of each covariate with access to addiction treatment; we additionally adjusted for year as an indicator variable to account for secular trends. Using this multivariable model and the margins command in Stata, we then calculated the adjusted probability of receiving pharmacotherapy.

To understand the effect of considering a different timeframe for receipt of pharmacotherapy after OUD diagnosis, we conducted sensitivity analyses in which the outcome of interest was receipt of a medication within 3 and 12 months (compared with 6 months) of OUD diagnosis and requiring 3 or more and 12 or more months of continuous enrollment, respectively. We repeated the multivariable model for both timeframes. Analyses were conducted from April 25 to December 31, 2016, using Stata, version 13.1 (StataCorp LP). All statistical tests were 2-sided and considered significant at P < .05.

Results

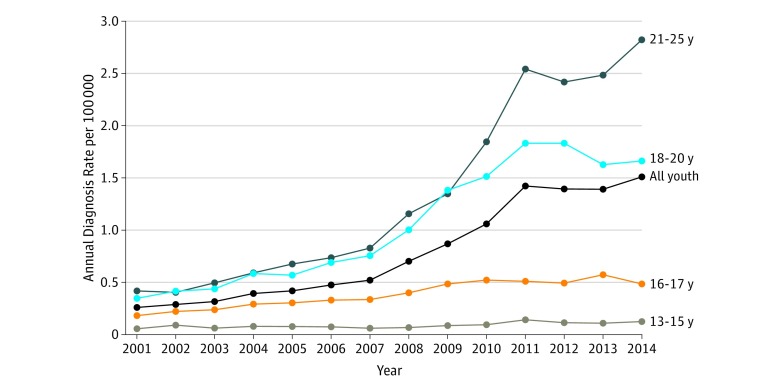

Between January 1, 2001, and June 30, 2014, there were 9 710 131 youth aged 13 to 25 years in the Optum database with 6 or more months of continuous enrollment and, of these youth, 20 822 (0.2%) met the criteria for an OUD diagnosis. Median time observed prior to first OUD diagnosis was 20 months per individual (interquartile range [IQR], 7-45 months). Figure 1 shows the diagnosis rate by calendar year according to age. The overall diagnosis rate increased with each subsequent study year, rising nearly 6-fold, from 0.26 per 100 000 person-years in 2001 to 1.51 per 100 000 person-years in 2014. This rise was driven primarily by increases in diagnoses among young adults (≥18 years), although diagnosis rates for all age categories increased over the study period.

Figure 1. Trends in Annual Rate of New Diagnoses of Opioid Use Disorder Among Youth .

Data obtained from Optum database, January 1, 2001, to December 31, 2014 (N = 20 822).

Table 1 displays the characteristics of the sample. Among youth with OUD, 65.8% were male and mean age (SD) was 21.0 (2.5) years at the time of diagnosis; most youth with OUD came from a predominantly non-Hispanic white neighborhood (82.2%). Compared with the overall sample, youth with OUD were more likely to be male or from a non-Hispanic white neighborhood, metropolitan area, high educational level neighborhood, low poverty level neighborhood, or the Northeast.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Overall Sample .

| Characteristic | Youth, % | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without OUD (n = 9 689 309) |

With OUD (n = 20 822) |

||

| Age of diagnosis, y | |||

| 21-25 | NA | 53.1 | |

| 18-20 | NA | 34.5 | |

| 16-17 | NA | 9.2 | |

| 13-15 | NA | 3.2 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 49.8 | 65.8 | <.001 |

| Female | 50.2 | 34.2 | |

| Race/ethnicitya | <.001 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 68.2 | 82.2 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 2.6 | 0.5 | |

| Hispanic | 10.1 | 5.6 | |

| Asian | 2.9 | 1.1 | |

| Mixed | 16.2 | 10.5 | |

| Geographic region | |||

| Metropolitan | 64.4 | 67.8 | <.001 |

| Nonmetropolitan | 35.6 | 32.2 | |

| Neighborhood educational levelb | |||

| High | 58.5 | 67.4 | <.001 |

| High-middle | 21.9 | 19.9 | |

| Low-middle | 14.1 | 10.2 | |

| Low | 5.5 | 2.5 | |

| Neighborhood poverty levelc | |||

| Low | 44.1 | 54.1 | <.001 |

| Low-middle | 25.5 | 24.9 | |

| High-middle | 20.0 | 15.4 | |

| High | 10.4 | 5.6 | |

| Census region | |||

| South | 44.1 | 41.7 | <.001 |

| Midwest | 29.4 | 26.3 | |

| West | 16.4 | 17.4 | |

| Northeast | 10.1 | 14.6 | |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; OUD, opioid use disorder.

Race/ethnicity data were derived from a combination of geocoded census block group-level race from the 2000 US Census and surname analysis to identify Asian and Hispanic individuals; mixed neighborhoods are those that did not meet a 75% threshold for white, black, or Hispanic ethnicity.

Neighborhood educational level was based on geocoded census block group-level data from the 2000 US census; high education level denotes neighborhoods with less than 15% of individuals with less than high school education; high-middle, 15.0% to 24.9%; low-middle, 25.0% to 39.9%; and low, 40.0% or more of individuals.

Neighborhood poverty was based on geocoded census block group-level data from the 2000 US census: low denotes neighborhoods with less than 5.0% of individuals living below the poverty level; low-middle, 5.0% to 9.9%; high-middle, 10.0% to 19.9%; and high, 20.0% or more.

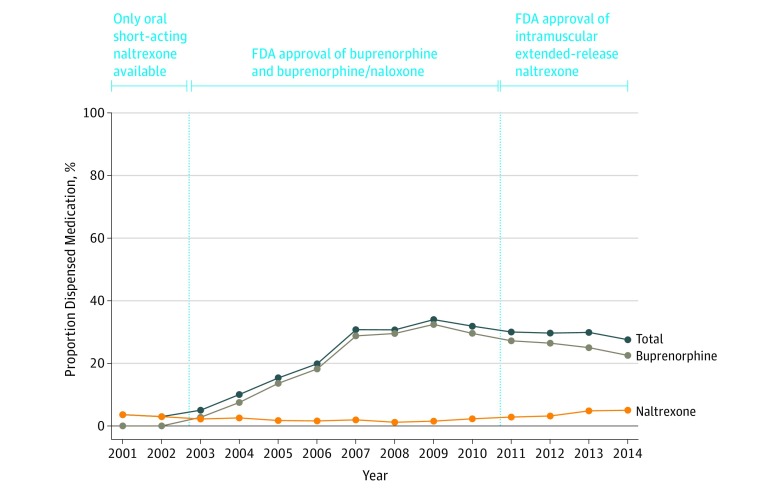

Overall, 5580 (26.8%) youth with OUD received either buprenorphine or naltrexone within 6 months of their first observed diagnosis. Figure 2 shows the percentage of youth who received medications by year. Medication receipt increased more than 10-fold from 2002, the year with the lowest percentage of youth receiving pharmacotherapy (3.0%), to 2009, the year with the highest percentage (31.8%). For the most recent study year (2014), the percentage was 27.5%. Medication receipt increased overall during the study period (odds ratio [OR], 1.11 per year; 95% CI, 1.10-1.12). In analyses handling year as a continuous predictor with splines corresponding to FDA approval of buprenorphine in 2002 and of intramuscular extended-release naltrexone in 2010, the odds of receiving buprenorphine relative to naltrexone increased from 2002 to 2010 (OR, 1.31 per year; 95% CI, 1.22-1.39), but the odds of receiving naltrexone relative to buprenorphine increased from 2010 to 2014 (OR, 1.17 per year; 95% CI, 1.09-1.25).

Figure 2. Trends in the Proportion of Youth Dispensed Buprenorphine or Naltrexone Within 6 Months of Opioid Use Disorder Diagnosis .

Relationship with annual diagnosis rate and introduction of medications by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Data obtained from Optum database, January 1, 2001, to December 31, 2014 (N = 20 822). Youth prescribed both medications during the 6 months following OUD diagnosis were classified according to the first medication they received.

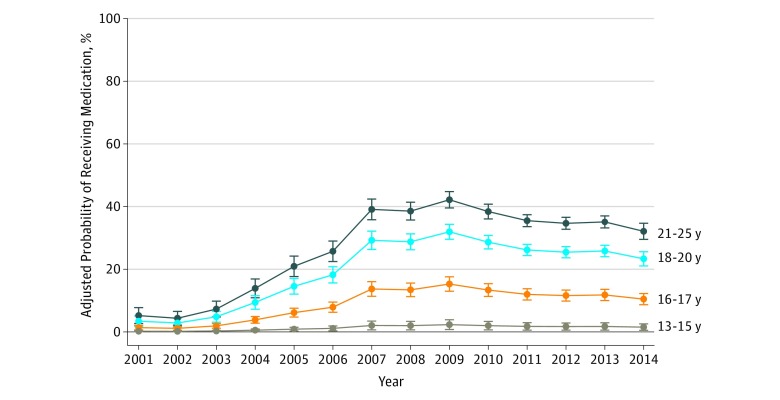

Table 2 displays the percentage of youth who received a medication according to sociodemographic characteristics. In the multivariable model, factors significantly associated with decreased odds of medication receipt included younger age, female sex, non-Hispanic black race, Hispanic ethnicity, and low-middle neighborhood poverty level. Figure 3 shows time trends in the adjusted probability of receiving a medication according to age group. Increases were greatest between 2003 and 2007, with larger increases observed among older youth compared with younger individuals.

Table 2. Sociodemographic Characteristics of 20 822 Youth With Opioid Use Disorder .

| Characteristica | Received Medication, % (n = 5580) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted Probability of Receiving Medication, % (95% CI)b | Adjusted OR (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of diagnosis, y | ||||

| 21-25 (n = 11 050) | 33.0 | 1 [Reference] | 30.5 (30.0-31.5) | 1 [Reference] |

| 18-20 (n = 7186) | 24.0 | 0.64 (0.60-0.69) | 22.0 (21.0-23.0) | 0.64 (0.60-0.69) |

| 16-17 (n = 1925) | 10.0 | 0.23 (0.19-0.26) | 9.7 (8.4-11.1) | 0.25 (0.21-0.29) |

| 13-15 (n = 661) | 1.5 | 0.03 (0.02-0.06) | 1.4 (0.4-2.3) | 0.03 (0.02-0.06) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male (n = 13 698) | 28.7 | 1 [Reference] | 24.4 (23.5-25.3) | 1 [Reference] |

| Female (n = 7124) | 23.1 | 0.75 (0.70-0.80) | 20.3 (19.2-21.3) | 0.79 (0.73-0.84) |

| Race/ethnicityc | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white (n = 17 119) | 27.1 | 1 [Reference] | 23.1 (22.3-23.9) | 1 [Reference] |

| Non-Hispanic black (n = 105) | 18.1 | 0.59 (0.36-0.98) | 14.8 (7.9-21.7) | 0.58 (0.33-0.99) |

| Hispanic (n = 1165) | 23.4 | 0.82 (0.71-0.94) | 20.0 (17.6-22.3) | 0.83 (0.71-0.97) |

| Asian (n = 224) | 24.5 | 0.87 (0.64-1.19) | 19.6 (14.5-24.6) | 0.81 (0.59-1.12) |

| Mixed (n = 2175) | 26.8 | 0.98 (0.89-1.09) | 23.9 (21.9-25.9) | 1.05 (0.93-1.17) |

| Geographic region | ||||

| Metropolitan (n = 13 651) | 26.5 | 1 [Reference] | 22.9 (22.1-23.8) | 1 [Reference] |

| Nonmetropolitan (n = 6473) | 27.2 | 1.04 (0.97-1.11) | 22.9 (21.8-24.1) | 1.00 (0.93-1.07) |

| Neighborhood educational leveld | ||||

| High (n = 14 023) | 26.8 | 1 [Reference] | 22.7 (21.9-23.6) | 1 [Reference] |

| High-middle (n = 4148) | 27.6 | 1.04 (0.96-1.12) | 23.7 (22.3-25.2) | 1.06 (0.97-1.15) |

| Low-middle (n = 2113) | 25.7 | 0.94 (0.85-1.05) | 23.1 (21.0-25.2) | 1.02 (0.90-1.16) |

| Low (n = 518) | 23.4 | 0.83 (0.68-1.02) | 20.7 (16.7-24.7) | 0.89 (0.69-1.14) |

| Neighborhood poverty levele | ||||

| Low (n = 11 225) | 27.6 | 1 [Reference] | 23.7 (22.7-24.7) | 1 [Reference] |

| Low-middle (n = 5179) | 25.8 | 0.91 (0.85-0.98) | 21.9 (20.6-23.1) | 0.90 (0.83-0.98) |

| High-middle (n = 3211) | 25.7 | 0.91 (0.83-0.99) | 22.0 (20.3-23.6) | 0.91 (0.81-1.01) |

| High (n = 1157) | 26.5 | 0.95 (0.83-1.09) | 22.9 (19.9-25.9) | 0.96 (0.80-1.14) |

| Census region | ||||

| South (n = 8688) | 27.0 | 1 [Reference] | 22.8 (21.7-23.8) | 1 [Reference] |

| Midwest (n = 5469) | 26.8 | 0.99 (0.92-1.07) | 23.9 (22.6-25.1) | 1.06 (0.98-1.15) |

| West (n = 3618) | 26.8 | 1.01 (0.92-1.10) | 22.9 (21.4-24.4) | 1.01 (0.91-1.11) |

| Northeast (n = 3044) | 25.9 | 0.95 (0.86-1.04) | 21.9 (20.3-23.4) | 0.95 (0.86-1.05) |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

Where counts do not add to total, data were missing.

Adjusted for all other covariates listed in the table in addition to year that an individual was diagnosed with opioid use disorder (coded as an indicator variable).

Race/ethnicity data were derived from a combination of geocoded census block group-level race from the 2000 US census and surname analysis to identify Asian and Hispanic individuals; mixed neighborhoods are those that did not meet a 75% threshold for white, black, or Hispanic ethnicity.

Neighborhood educational level was based on geocoded census block group-level data from the 2000 US census: high education level denotes neighborhoods with less than 15.0% of individuals with less than high school education; high-middle, 15.0% to 24.9%; low-middle, 25.0% to 39.9%; and low, 40.0% or more of individuals.

Neighborhood poverty was based on geocoded census block group-level data from the 2000 US census: low denotes neighborhoods with less than 5.0% of individuals living below the poverty level; low-middle, 5.0% to 9.9%; high-middle, 10.0% to 19.9%; and high, 20.0% or more.

Figure 3. Proportion of Youth With a Claim Containing an Opioid Use Disorder Diagnosis Who Were Dispensed Any Buprenorphine or Naltrexone According to Age at First Diagnosis .

Data obtained from Optum database, January 1, 2001, to December 31, 2014 (N = 20 822). Error bars represent 95% CIs for the estimate.

Table 3 compares the characteristics of youth who received buprenorphine compared with those who received naltrexone. Youth were less likely to receive buprenorphine than naltrexone if they were younger or female. They were more likely to receive buprenorphine if they were from a nonmetropolitan area; low-middle or low educational level neighborhood; low-middle, high-middle, or high poverty level neighborhood; or from the Midwest.

Table 3. Unadjusted ORs for Receipt of Buprenorphine Relative to Naltrexone Among 5580 Youth With OUD Who Received a Medication: Optum, January 1, 2001, to December 31, 2014.

| Characteristica | Received Medication, %b | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buprenorphine (n = 4976) |

Naltrexone (n = 604) |

||

| Age of diagnosis, yc | |||

| 21-25 (n = 3650) | 90.3 | 9.7 | 1 [Reference] |

| 18-20 (n = 1727) | 87.9 | 12.1 | 0.78 (0.65-0.94) |

| 16-17 (n = 193) | 81.4 | 18.7 | 0.47 (0.32-0.68) |

| Sex | |||

| Male (n = 3931) | 89.7 | 10.3 | 1 [Reference] |

| Female (n = 1649) | 87.8 | 12.2 | 0.82 (0.69-0.99) |

| Race/ethnicityd | |||

| Non-Hispanic white (n = 4644) | 89.1 | 10.9 | 1 [Reference] |

| Other (n = 936) | 89.4 | 10.5 | 1.03 (0.82-1.30) |

| Geographic region | |||

| Metropolitan (n = 3623) | 88.0 | 12.0 | 1 [Reference] |

| Nonmetropolitan (n = 1764) | 91.4 | 8.6 | 1.44 (1.19-1.75) |

| Neighborhood educational levele | |||

| High (n = 3764) | 88.3 | 11.7 | 1 [Reference] |

| High-middle (n = 1146) | 89.7 | 10.3 | 1.15 (0.93-1.43) |

| Low-middle/low (n = 664) | 93.1 | 6.9 | 1.77 (1.29-2.43) |

| Neighborhood poverty levelf | |||

| Low (n = 3106) | 87.7 | 12.3 | 1 [Reference] |

| Low-middle (n = 1335) | 89.9 | 10.1 | 1.25 (1.01-1.53) |

| High-middle (n = 827) | 92.3 | 7.7 | 1.67 (1.27-2.20) |

| High (n = 307) | 92.8 | 7.2 | 1.82 (1.16-2.84) |

| Census region | |||

| South (n = 2342) | 88.6 | 11.4 | 1 [Reference] |

| Midwest (n = 1468) | 91.0 | 9.0 | 1.30 (1.04-1.62) |

| West (n = 981) | 88.4 | 11.6 | 0.97 (0.77-1.23) |

| Northeast (n = 789) | 88.3 | 11.7 | 0.97 (0.75-1.25) |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; OUD, opioid use disorder.

Where counts do not add to total, data are missing.

Buprenorphine includes formulations of buprenorphine or buprenorphine-naloxone combination, and naltrexone includes both oral short-acting naltrexone and intramuscular extended-release naltrexone; if a participant received both medications within 6 months of their first OUD diagnosis, they are classified according to the first medication they received.

Youth aged 13 to 15 years excluded due to low cell counts.

Race/ethnicity data collapsed due to low cell counts; derived were from a combination of geocoded census block group-level race from the 2000 US census and surname analysis to identify Asian and Hispanic individuals; mixed neighborhoods are those that did not meet a 75% threshold for white, black, or Hispanic ethnicity.

Low-middle/low categories combined due to low cell counts; neighborhood educational level was based on geocoded census block group-level data from the 2000 US census: high education level denotes neighborhoods with less than 15.0% of individuals with less than high school education; high-middle, 15.0% to 24.9%; low-middle, 25.0% to 39.9%; and low, 40.0% or more of individuals.

Neighborhood poverty was based on geocoded census block group-level data from the 2000 US census: low denotes neighborhoods with less than 5.0% of individuals living below the poverty level; low-middle, 5.0% to 9.9%; high-middle, 10.0% to 19.9%; and high, 20.0% or more.

Sensitivity analyses examining medication receipt within 3 and 12 months are reported in eTables 2 and 3 in the Supplement, respectively. Although effect sizes across age, sex, and race/ethnicity strata using 3- and 12-month timeframes were similar to those for a 6-month timeframe, adjusted ORs were not significant for non-Hispanic black youth, using a 3-month timeframe, or for non-Hispanic black youth and Hispanic youth, using a 12-month timeframe.

Discussion

In this large national study of buprenorphine and naltrexone dispensing among commercially insured youth with OUD, we found that only 1 in 4 youth received pharmacotherapy within 6 months of diagnosis during the 2001-2014 study period. From 2002 (when buprenorphine was introduced) to 2009, the percentage of youth receiving medication increased more than 10-fold, but subsequently declined amidst escalating OUD diagnosis rates. The odds of receiving pharmacotherapy were lower with younger age and among females compared with males, and non-Hispanic black and Hispanic youth compared with white youth. Overall, buprenorphine was dispensed 8 times more often than naltrexone. Naltrexone was more commonly dispensed to younger individuals and females and to youth in metropolitan areas, higher educational level neighborhoods, and lower poverty level neighborhoods.

Only a minority of youth with OUD received pharmacotherapy, thus revealing a potentially critical treatment gap. This finding reconfirms the 2016 surgeon general’s report that highlighted the large number of youth with untreated addiction and also supports the recent policy statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics calling for expanded access to medications for youth with OUD. Notably, we observed a decrease in the percentage of youth receiving pharmacotherapy from 2009 onward after a preceding rise. This decrease occurred amidst an escalating OUD diagnosis rate, as well as an increasing number of young adults nationwide receiving health insurance under an Affordable Care Act provision allowing coverage under a parent’s plan. Both of these forces likely resulted in an expansion in the number of youth in OUD care, which may not have been accompanied by improved access to medications. National data preceding the Affordable Care Act suggest that youth with commercial insurance are less likely to receive addiction treatment (with or without pharmacotherapy) than are youth with public insurance. In the face of changing national health insurance policies, further studies are needed to understand differences in diagnosis and treatment between commercially and publicly insured youth with OUD.

We found that adolescents younger than 16 years were least likely to receive medications, a finding likely reflecting that buprenorphine, the most common medication dispensed, is FDA approved only for individuals 16 years or older. We also observed that few adolescents received naltrexone, even after the introduction of its long-acting injectable formulation in 2010. Although trials comparing the efficacy of buprenorphine and naltrexone are pending, our results suggest that buprenorphine is much more commonly used; further studies should characterize patient, caregiver, and clinician preferences regarding these medications in addition to treatment outcomes.

Despite the demonstrated efficacy and FDA approval of buprenorphine for adolescents 16 years or older, we found that those aged 16 and 17 years were less likely than young adults 18 years or older to receive pharmacotherapy. It is well established that adolescents experience difficulty accessing addiction treatment. Availability of services for adolescents is limited; fewer than 1 in 3 specialty drug treatment programs in the United States offers care to adolescents. Nationwide, there is a shortage of physicians outside metropolitan areas with a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine and, compounding this, pediatricians who prescribe buprenorphine are rare. Nonetheless, we did not observe lower odds of receiving medication outside metropolitan areas. In one recent national study, access to buprenorphine significantly improved in rural areas from 2002 to 2011. Our results build on these prior findings by highlighting that, even though access to medications may be improving in many locations, use of pharmacotherapy among youth remains low overall. Ensuring access to medications among youth should remain a critical focus to ensure timely and equitable care regardless of location.

Our results suggest that the treatment gap for youth is greater for non-Hispanic black and Hispanic youth as well as for females. Underlying reasons are unclear and may relate to access to care, denial of care, or clinician bias. Prior studies have shown that poorer access to substance use treatment among minorities is in part explained by disparities in health insurance coverage. However, our results indicate that, even with coverage, non-Hispanic black and Hispanic youth are less likely than non-Hispanic white youth to receive medications for OUD. Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health highlight that, although receipt of past-year treatment between 2001 and 2008 among non-Hispanic white adolescents with any type of substance use disorder was low (10.7%), it was significantly lower for non-Hispanic black (6.9%) and Hispanic adolescents (8.5%). Even once they are in treatment, only half of non-Hispanic black and Hispanic adolescents complete treatment—a significantly lower proportion than non-Hispanic white adolescents. Similarly, data suggest that females may experience greater barriers to addiction treatment and demonstrate poorer outcomes compared with males. It is critical that clinicians and policymakers working to expand access to pharmacotherapy for youth ensure that services are disseminated in a way that addresses, rather than worsens, racial/ethnic and sex disparities.

Since most youth with OUD do not receive medications in a timely manner, strategies to improve access to evidence-based treatment for adolescents are needed. One strategy is to increase the number of pediatric addiction subspecialists. With the recent recognition of addiction medicine by the American Board of Medical Specialties, pediatricians and family physicians have new opportunities to pursue board certification and are well poised to disseminate developmentally appropriate services for youth. However, since there are unlikely to be sufficient pediatric addiction subspecialists to address the large number of youth with OUD, an additional strategy is to implement pharmacotherapy in pediatric primary care. This approach is increasingly used to treat adults with OUD and is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, we could not assess the severity of individuals’ addiction. It is possible that older youth or other demographic groups had more severe OUD for which pharmacotherapy was more strongly indicated. Second, our approach likely underestimated the number of youth with OUD since we relied on billing diagnoses. The actual proportion of youth with OUD who receive pharmacotherapy may be even lower than reported herein because many youth go undiagnosed or clinicians may be reluctant to code this sensitive diagnosis. Third, we were unable to assess receipt of methadone. Since provision of methadone to adolescents younger than 18 years is highly restricted, we do not anticipate that many underage youth received methadone; some youth 18 years or older may have received methadone from publicly funded programs. Fourth, our sample included only commercially insured youth; thus, generalizability to populations without private health insurance is unclear. Recent data suggest that adults without health insurance are unlikely to receive pharmacotherapy for OUD, whereas adults with public health insurance may be as likely to receive pharmacotherapy as those with private insurance.

Conclusions

We observed improvements in the percentage of youth receiving pharmacotherapy for OUD between 2001 and 2014, but noted an apparent decrease after 2009 amidst an escalating diagnosis rate and despite the FDA approval of long-acting injectable naltrexone in 2010. There remains substantial room for improvement in the provision of pharmacotherapy to youth with OUD. Both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the 2016 surgeon general’s report highlight that intervention early in the life course of youth addiction is critical for preventing progression to more severe disease, yet our data indicate that medications are underutilized for youth. Adolescents might especially be underserved in the current treatment environment, and female, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic youth appear less likely than their age-matched peers to receive medications. In the face of a worsening opioid crisis in the United States, strategies to expand the use of pharmacotherapy for adolescents and young adults are greatly needed, and special care is warranted to ensure equitable access for all affected youth to avoid exacerbating health disparities.

eTable 1. National Drug Codes Used to Identify Pharmacy Claims for Medications

eTable 2. Sociodemographic Characteristics of 23 312 Youth With Opioid Use Disorder and Odds Ratios (OR) for Receipt of a Medication (Buprenorphine or Naltrexone) Within 3 Months of Diagnosis: Optum, January 1, 2001 to December 31, 2014

eTable 3. Sociodemographic Characteristics of 15 824 Youth With Opioid Use Disorder and Odds Ratios (OR) for Receipt of a Medication (Buprenorphine or Naltrexone) Within 12 Months of Diagnosis: Optum, January 1, 2001 to December 31, 2014

References

- 1.Warner M, Hedegaard H, Chen LH. Trends in Drug-Poisoning Deaths: United States, 1999-2012. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen LH, Hedegaard H, Warner M. Drug-poisoning deaths involving opioid analgesics: United States, 1999-2011. NCHS Data Brief. 2014;(166):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA. 2013;309(7):657-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dart RC, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, et al. Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(3):241-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2000-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64(50-51):1378-1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaither JR, Leventhal JM, Ryan SA, Camenga DR. National trends in hospitalizations for opioid poisonings among children and adolescents, 1997 to 2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(12):1195-1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality The DAWN Report: Highlights of the 2011 Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) Findings on Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits. Rockville, MD: Drug Abuse Warning Network; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 2003-2013 National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services. Rockville, MD: Drug Abuse Warning Network; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zibbell JE, Iqbal K, Patel RC, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Increases in hepatitis C virus infection related to injection drug use among persons aged ≤30 years—Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, 2006-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(17):453-458. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2016: Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levy SJ, Williams JF; Committee on Substance Use and Prevention . Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1):e20161211-e20161211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV Among Youth. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han B, Hedden SL, Lipari R, Copello EAP, Kroutil LA. Receipt of Services for Behavioral Health Problems: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cummings JR, Wen H, Ko M, Druss BG. Race/ethnicity and geographic access to Medicaid substance use disorder treatment facilities in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):190-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saloner B, Stoller KB, Barry CL. Medicaid coverage for methadone maintenance and use of opioid agonist therapy in specialty addiction treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(6):676-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marsch LA, Bickel WK, Badger GJ, et al. Comparison of pharmacological treatments for opioid-dependent adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1157-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fudala PJ, Bridge TP, Herbert S, et al. ; Buprenorphine/Naloxone Collaborative Study Group . Office-based treatment of opiate addiction with a sublingual-tablet formulation of buprenorphine and naloxone. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(10):949-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krupitsky E, Nunes EV, Ling W, Illeperuma A, Gastfriend DR, Silverman BL. Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9776):1506-1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marsch LA, Moore SK, Borodovsky JT, et al. A randomized controlled trial of buprenorphine taper duration among opioid-dependent adolescents and young adults. Addiction. 2016;111(8):1406-1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woody GE, Poole SA, Subramaniam G, et al. Extended vs short-term buprenorphine-naloxone for treatment of opioid-addicted youth: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300(17):2003-2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kampman K, Jarvis M. American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) National Practice Guideline for the Use of Medications in the Treatment of Addiction Involving Opioid Use. J Addict Med. 2015;9(5):358-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenblatt RA, Andrilla CHA, Catlin M, Larson EH. Geographic and specialty distribution of US physicians trained to treat opioid use disorder. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(1):23-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Center for Substance Abuse Treatment Guidelines for the Use of Buprenorphine in the Treatment of Opioid Addiction. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 40. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration National Expenditures for Mental Health Services and Substance Abuse Treatment 1986–2009. HHS Publication No. SMA-13-4740. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Committee on Substance Use and Prevention Medication-assisted treatment of adolescents with opioid use disorders. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20161893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.2015 National Drug Control Strategy. Washington, DC: Office of National Drug Control Policy; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Surgeon General ; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stein BD, Gordon AJ, Sorbero M, Dick AW, Schuster J, Farmer C. The impact of buprenorphine on treatment of opioid dependence in a Medicaid population: recent service utilization trends in the use of buprenorphine and methadone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123(1-3):72-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Rehkopf DH, Subramanian SV. Race/ethnicity, gender, and monitoring socioeconomic gradients in health: a comparison of area-based socioeconomic measures—the public health disparities geocoding project. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1655-1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.US Census Bureau Geographic Areas Reference Manual. Washington, DC: : US Census Bureau; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Census Bureau 2000 Census of Population and Housing. Washington, DC; US Census Bureau; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiscella K, Fremont AM. Use of geocoding and surname analysis to estimate race and ethnicity. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(4, pt 1):1482-1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stein BD, Pacula RL, Gordon AJ, et al. Where is buprenorphine dispensed to treat opioid use disorders? the role of private offices, opioid treatment programs, and substance abuse treatment facilities in urban and rural counties. Milbank Q. 2015;93(3):561-583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saloner B, Carson N, Lê Cook B. Explaining racial/ethnic differences in adolescent substance abuse treatment completion in the United States: a decomposition analysis. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(6):646-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cook BL, Alegría M. Racial-ethnic disparities in substance abuse treatment: the role of criminal history and socioeconomic status. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(11):1273-1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sommers BD, Kronick R. The Affordable Care Act and insurance coverage for young adults. JAMA. 2012;307(9):913-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winstanley EL, Steinwachs DM, Stitzer ML, Fishman MJ. Adolescent substance abuse and mental health: problem co-occurrence and access to services. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2012;21(4):310-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee JD, Nunes EV, Mpa PN, et al. NIDA Clinical Trials Network CTN-0051, Extended-Release Naltrexone vs. Buprenorphine for Opioid Treatment (X:BOT): study design and rationale. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;50:253-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mericle AA, Arria AM, Meyers K, Cacciola J, Winters KC, Kirby K. National trends in adolescent substance use disorders and treatment availability: 2003-2010. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2015;24(5):255-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dick AW, Pacula RL, Gordon AJ, et al. Growth In buprenorphine waivers for physicians increased potential access to opioid agonist treatment, 2002-11. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(6):1028-1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alegria M, Carson NJ, Goncalves M, Keefe K. Disparities in treatment for substance use disorders and co-occurring disorders for ethnic/racial minority youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(1):22-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tuchman E. Women and addiction: the importance of gender issues in substance abuse research. J Addict Dis. 2010;29(2):127-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wood E, Samet JH, Volkow ND. Physician education in addiction medicine. JAMA. 2013;310(16):1673-1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hadland SE, Wood E, Levy S. How the paediatric workforce can address the opioid crisis. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1260-1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Kretsch N, et al. Collaborative care of opioid-addicted patients in primary care using buprenorphine: five-year experience. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(5):425-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.LaBelle CT, Han SC, Bergeron A, Samet JH. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B): statewide implementation of the Massachusetts collaborative care model in community health centers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;60:6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levy SJ, Kokotailo PK; Committee on Substance Abuse . Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):e1330-e1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jaffe JH, O’Keeffe C. From morphine clinics to buprenorphine: regulating opioid agonist treatment of addiction in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70(2)(suppl):S3-S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones CM, Campopiano M, Baldwin G, McCance-Katz E. National and state treatment need and capacity for opioid agonist medication-assisted treatment. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(8):e55-e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abraham AJ, Rieckmann T, Andrews CM, Jayawardhana J. Health insurance enrollment and availability of medications for substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(1):41-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. National Drug Codes Used to Identify Pharmacy Claims for Medications

eTable 2. Sociodemographic Characteristics of 23 312 Youth With Opioid Use Disorder and Odds Ratios (OR) for Receipt of a Medication (Buprenorphine or Naltrexone) Within 3 Months of Diagnosis: Optum, January 1, 2001 to December 31, 2014

eTable 3. Sociodemographic Characteristics of 15 824 Youth With Opioid Use Disorder and Odds Ratios (OR) for Receipt of a Medication (Buprenorphine or Naltrexone) Within 12 Months of Diagnosis: Optum, January 1, 2001 to December 31, 2014