Highlights

Despite the supposed integration of “population and public health” (PPH), issues in the areas of research funding, the public health workforce and ethics continue to present challenges to the field’s unity.

The authors argue that overcoming these challenges is a worthwhile goal for the future of population well-being in Canada.

Introduction

“Are population and public health truly a unified field, or is population health simply attaching itself to public health as a means of gaining credibility?”

This commentary was prompted by the above question, which was asked during K. L.’s PhD candidacy exam. In response, K. L. cited recent developments in the field to support her conviction that population and public health (PPH) existed positively as a unified discipline. However, through conversations that ensued over the subsequent weeks and months, we concluded that this issue goes deeper than the existence of departments and organizations labelled “population and public health,” and may benefit from debate and discussion, particularly for the incoming generation of PPH scholars. In this commentary, we argue that (1) the PPH label at times implies a coherence of ideas, values and priorities that may not be present; (2) it is important and timely to work towards a more unified PPH; and (3) both challenges to and opportunities for a more unified PPH exist, which we illustrate using the broad areas of research funding, the public health workforce and PPH ethics.

Argument 1: The PPH label implies a coherence that may not be present

In our experience, the PPH label at times conveys the impression of a coherence of ideas, values and priorities that may not exist. The impression of coherence is conveyed in many ways; for example, by PPH

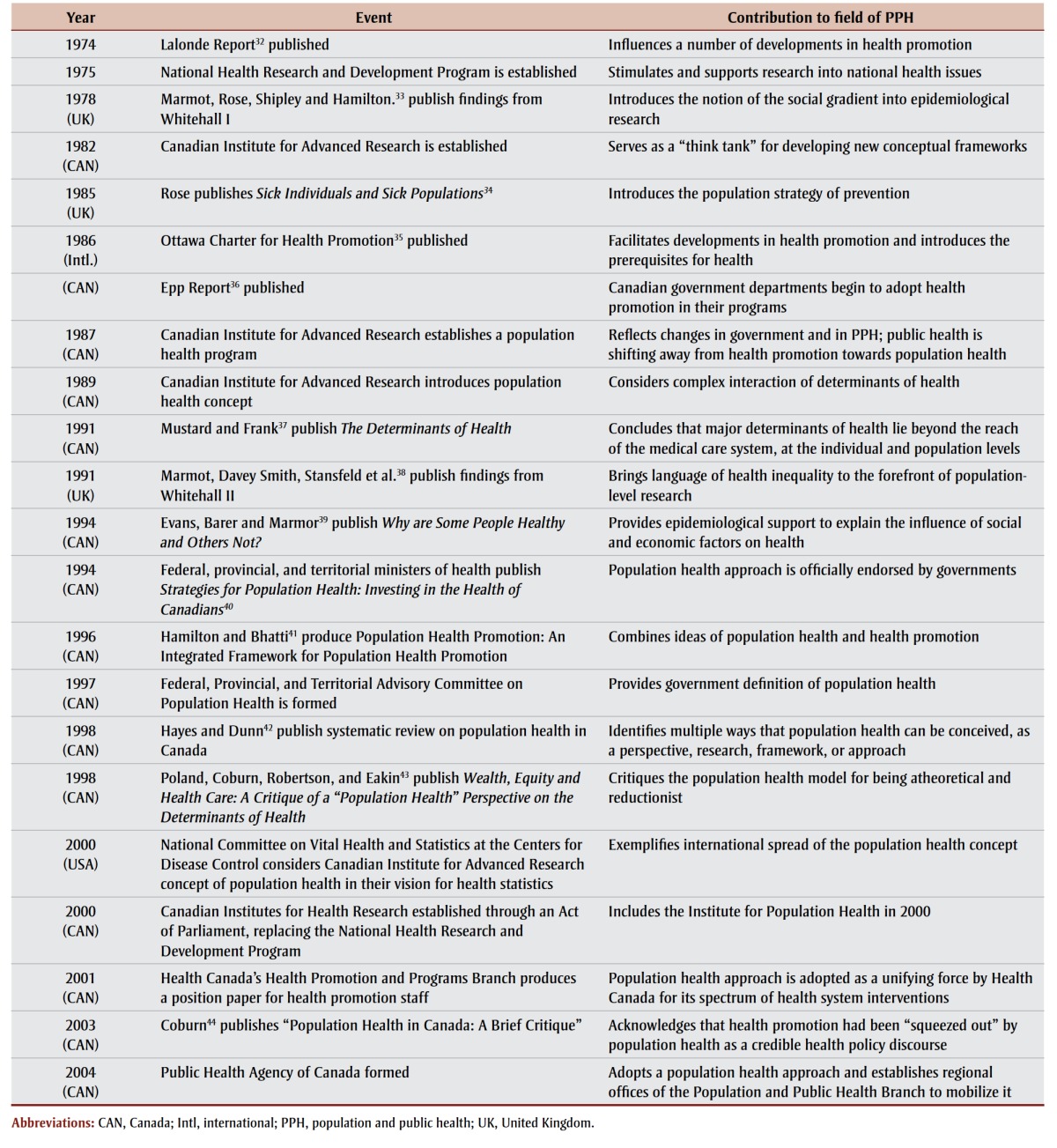

graduate training programs that exist in universities in Calgary,1 Vancouver,2 Ottawa3 and Waterloo;4 by the existence of PPH departments within health systems;5,6 and by various historical developments (see Table 1). Yet, the coherence is not always present in practice. K. L., for example, recalls meeting a fellow graduate student at a national public health meeting who remarked that they were used to “no one knowing what [population health] is” and that they “usually just say public health,” thus implying that they are—at least to some extent or to some audiences—the same. A contrasting example is L. M.’s experience, as an academic who would describe herself as a “population/ public health researcher,” of being regarded by colleagues within public health as “not really a public health person” because she does not have a health professional degree. Therefore, the need to clarify the boundaries and future of PPH remains, particularly due to the increasing number of trainees in this field.

TABLE 1. Historical timeline of key events in the development of “population and public health,” 1974–2004.

|

Argument 2: It is important and timely to work towards a more unified PPH

A key question at the heart of our commentary is whether PPH should be a unified discipline. Some have asserted that the answer is “no.”7 Arguments against a unified PPH include important points such as the concern that PPH is too broad in scope to be useful or that it carries the potential of diluting the urgency of public health.7

We disagree, and feel that efforts toward a more unified PPH are both important and timely. These efforts are important because embracing the social determinants of health (SDOH) and thinking critically about health inequities, which PPH aims to do,8 is necessary to accept a holistic conceptualization of health and to overcome professional and organizational silos that prevent intersectoral action on health and health equity. In some cases, overcoming silos includes offsetting historical changes to the public health system. For example, in many Canadian jurisdictions, “health” presently constitutes its own ministry (e.g. Alberta Health or Health Canada), implying a separation from other determinants of well-being, whereas formerly it was broader in scope (e.g. the federal Department of Pensions and National Health [1928] and Department of National Health and Welfare [1944]).9,10

It is timely to work towards a more unified PPH. Unlike even 20 years ago, there are now many programs of study in Canadian universities for students who do not necessarily intend to go into public health in its conventional sense (e.g. public health nursing or a public health and preventive medicine specialty) but rather who wish to pursue an academic career, or to apply principles of PPH in a range of sectors. The Bachelor of Health Sciences Program at the University of Calgary, and in particular the Health and Society specialization within that program, is an excellent example. We disclose that this relatively recent trend describes us: we were both drawn to the idea of a unified PPH because it represented a way to bring together health and social sciences/ humanities in a way that is connected to, but importantly steps outside of, the formal health sector and professions.

Argument 3: Important challenges and opportunities for an integrated field to exist

To permit reflection on PPH, we identify three (of potentially many) areas that appear to create cleavage in the field: research funding, the public health workforce and PPH ethics. For each area, with the intention of opening a dialogue, we identify what we see as key challenges and opportunities.

1. Research funding

Challenge: The 2009 announcement by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada that they would no longer fund health research created a challenge for PPH as an interdisciplinary field, as it left many social scientists working within PPH to navigate the different funding landscape and procedures of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR).11 This change highlighted the different norms and expectations for social sciences versus traditional health research (e.g. structure of research grant applications, authorship, length and pace of publications, emphasis on theory), 12 as well as the areas of research considered viable and worthwhile. These differences, arguably, may particularly disadvantage those who are most poised to contribute rich theoretical and critical scholarship to PPH.

Opportunity: The integration of social and health sciences is essential to PPH. As a national funding agency and guiding body for health research in Canada, CIHR provides a forum where challenges to integration can be overcome. One example is the significant efforts that have been made by CIHR’s Institute of Population and Public Health (IPPH) to shift the peer review landscape to facilitate fair and transparent evaluation of interdisciplinary applicants by reviewers with appropriate expertise through specific, priority-driven competitions.13 Though the challenges noted above have not disappeared, it seems that important progress is being made.

2. Public health workforce

Challenge: To a large extent, the public health workforce (e.g. physicians, public health inspectors, laboratory workers, nurses) remains situated within the health sector (i.e. in health services organizations or ministries of health). This arrangement presents a challenge for action on the SDOH and health equity, which is at the forefront of PPH and by definition goes beyond the regulatory and legal frameworks of public health. Action on the SDOH may fall outside the scope of day-to-day public health work providing services and programs to the public.14 Additionally, the legislative framework that mandates public health in jurisdictions may not support an integrative PPH. For example, Alberta’s Public Health Act: Revised Statues of Alberta 200015 makes no mention of the SDOH, or even of chronic disease. These issues may present a source of cleavage between the large number of experts working within public health’s core functions (e.g. disease prevention, and communicable disease prevention in particular) and the stated aim of PPH to broadly influence population health (i.e. via social policy interventions, outside of the health system).

Opportunity: Despite these sources of cleavage, significant opportunities do exist and in some cases progress has been made within the professional and regulatory arms of public health towards a more unified field. Brassolotto, Raphael and Baldeo,14 for instance, have documented that in Ontario some health units actively pursue advocacy and action on the SDOH in addition to their delivery of more traditional public health services. Public Health Ontario, for example, has incorporated addressing determinants of health and reducing health inequities throughout the Ontario Public Health Standards. 16

Legislative progress has also been made in some jurisdictions. In British Columbia, the Public Health Act (SBC 2008) includes chronic disease as a health impediment, which at least in theory allows for the minister to incorporate the social determinants of health or equity concerns when developing a plan “to identify, prevent and mitigate” its adverse effects.17 Quebec’s Public Health Act (S-2.2) goes further, by allowing the minister of health, public health director and institutions to intervene not only to prevent disease and trauma, but also to consider “social problems that have an impact on the health of the population”18,p.4 through acting on the SDOH. An example of this is Quebec’s promotion and implementation of healthy public policies through health impact assessment.19 Finally, in recent years, the Public Health Agency of Canada has attempted to define the ever-expanding PPH workforce, through core competencies for public health work and the harmonization of information on the diverse postsecondary and postgraduate training opportunities that exist in PPH.20,21 Such attempts present the opportunity to better understand some of the features of PPH that permit intersectoral action and build on them, toward a more integrative PPH workforce and field of practice.

3. Efforts to advance the ethical foundations of PPH

Challenge: As public health practice is predominantly situated within the health care system, its ethical guidelines have traditionally been sanctioned by bioethical principles (i.e. autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, respect for human rights) and guided by the moral theory of utilitarianism (i.e. the public good).22 However, as noted elsewhere,23,24 these bioethics principles have proven inadequate to fully meet the challenges of PPH, where intervention activities include structural interventions that apply to whole populations and may therefore conflict with the will of the public to the benefit of the population (e.g. community water fluoridation). This tension has led to the creation of critical subdisciplines (e.g. public health ethics) to encourage advancements to ethical thinking in ways that respond to this need (e.g. the Nuffield Council on Bioethics’ stewardship model).25

Opportunity: There is an exciting trend in evolving critical scholarship on some of the unique challenges that exist for population health interventions sanctioned under public health ethical frameworks. For instance, there is scholarly debate around the merits and drawbacks of population-wide, or universal, interventions in PPH that, on the one hand, identifies potential negative consequences of the population-level approach,26,27and, on the other, argues for the leverage and potential equity of that approach.28 This work will contribute to an increasingly robust intellectual foundation for PPH. Relatedly, some ethical frameworks that better incorporate aspects of population health have emerged that respond to the field’s need for transparency and minimal restriction, social justice and equity.23,29-31 Such work may facilitate greater unification of PPH, as it begins to tackle the issue of how to balance the utilitarian aspect of public health, which many view as its key asset, alongside thoughtful consideration of the possible unintended consequences of this approach toward improving health for all.

Conclusion

As PPH continues to evolve throughout the twenty-first century and enrollment in “population and public health” interdisciplinary graduate programs continues to grow, we believe that the question of whether and how to better integrate PPH will remain relevant and important. We recognize that the areas we have considered above (i.e. research, the public health workforce and PPH ethics) are not mutually exclusive and represent only a few examples among many others that likely exist.

We encourage future research and discussion on the topic and we hope that this paper prompts further debate and discussion among PPH leaders, workers and trainees.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr. Margaret Russell for asking the question that prompted this reflection. Kelsey Lucyk is supported by an Alberta Innovates—Health Solutions Graduate Studentship. Lindsay McLaren is supported by an Applied Public Health Chair (see http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e /49128.html) funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Institute of Population and Public Health; Institute of Musculoskeletal Health and Arthritis); the Public Health Agency of Canada; and Alberta Innovates—Health Solutions.

References

- University of Calgary. Calgary (AB):: 2017 [modified 2017 Feb; cited 2017 Apr 4]. CHS Graduate Student Competencies & Requirements in Population and Public Health [Internet]. . Available from: http://wcm.ucalgary.ca/gse/files/gse/competencies_population_public_health_2017.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- University of British Columbia School of Population and Public Health. Vancouver (BC):: [date unknown; cited 2017 Apr 4]. Master of public health (MPH) [Internet]. . Available from: https://www.grad.ubc.ca/prospective-students/graduate-degree-programs/master-of-public-health . [Google Scholar]

- University of Ottawa. Ottawa (ON):: cited 2017 Apr 4]. Graduate and postdoctoral studies [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.grad.uottawa.ca/Default.aspx?tabid=1727&page=SubjectDetails&Kind=H&SubjectId=97 . [Google Scholar]

- University of Waterloo. Waterloo (ON):: [date unknown; cited 2017 Apr 4]. School of Public Health and Health Systems [Internet]. . Available from: https://uwaterloo.ca/public-health-and-health-systems/future-graduate-students/research-based-programs/public-health-and-health-systems-phd . [Google Scholar]

- Alberta Health Services. Edmonton (AB):: 2017 [cited 2017 Apr 4]. Population, public and indigenous health: strategic clinical network [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.albertahealthservices.ca/scns/Page13061.aspx . [Google Scholar]

- Regina Qu’Appelle Health Region. Regina (SK):: 2015 [cited 2017 Apr 4]. Population and Public Health [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.rqhealth.ca/departments/population-and-public-health . [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein M. Rethinking the meaning of public health. J Law Med Ethics. 2002;30((2)):144–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2002.tb00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank J. Why “population health”? Can J Public Health. 1995;86((3)):162–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung-Gertler J. Toronto (ON):: 2008 Nov 26 [updated 2014 Aug 5; cited 2017 Apr 4]. Health Canada. In: The Canadian Encyclopedia [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/health-canada . [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Ottawa (ON):: 2008 [modified 2008 Apr 4; cited 2017 Apr 4]. History [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/about_apropos/history-eng.php . [Google Scholar]

- Halbersma J. University Affairs magazine. Ottawa (ON):: 2014 Oct 8 [cited 2017 Apr 4]. It’s time for social scientists to apply for CIHR grants [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.universityaffairs.ca/opinion/in-my-opinion/time-social-scientists-apply-cihr-grants/ . [Google Scholar]

- Albert K. Erasing the social from social science: the intellectual costs of boundary-work and the Canadian Institute of Health Research. Canadian J of Sociol. 2014;39((3)):393–420. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Ottawa (ON):: 2014 [updated 2014 Dec 22; cited 2017 Apr 4]. Changes to the Institutes and reforms of open programs and peer review [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48930.html . [Google Scholar]

- Brassolotto J, Raphael D, Baldeo N. Epistemological barriers to addressing the social determinants of health among public health professionals in Ontario, Canada: a qualitative inquiry. Crit Public Health. 2014;24((3)):321–36. [Google Scholar]

- Province of Alberta. Alberta Queen’s Printer; Edmonton (AB): 2016. Public Health Act, Revised Statutes of Alberta 2000, Chapter P-37. p. 64 p. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long- Term Care. Queen’s Printer of Ontario; 2016 [Publication No. Toronto (ON): Ontario public health standards, 2008 [revised May 2016]. p. 020646]. [Google Scholar]

- Province of British Columbia. Victoria (BC):: 2008 [updated 2017 Mar 8; cited 2017 Apr 4]. Public Health Act, SBC 2008, chapter 28 [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.bclaws.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/00_08028_01 . [Google Scholar]

- Gouvernement du Québec. Éditeur officiel du Québec; 2016 [updated] Québec City (QC): Public Health Act, chapter S-2.2. p. 36 p. [Google Scholar]

- Institut national de santé publique Québec. Montréal (QC):: [date unknown; cited 2017 Apr 4]. Health impact assessment [Internet]. . Available from: http://politiquespubliques.inspq.qc.ca/en/evalutaion.html . [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). PHAC; 2008 [Catalogue No. Ottawa (ON): Core competencies for public health in Canada, release 1.0. pp. HP5–51/2008]. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Ottawa (ON):: [modified 2016 Jul 25; cited 2017 Apr 4]. Plan your career in public health [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/php-psp/training-eng.php . [Google Scholar]

- Kass N. An ethics framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91((11)):1776–82. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upshur RE. Principles for the justification of public health intervention. Can J Public Health. 2002;93((2)):101–3. doi: 10.1007/BF03404547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott L, Hatfield J, McIntyre L. A scoping review of unintended harm associated with public health interventions: towards a typology and an understanding of underlying factors. Int J Public Health. 2014;59((1)):3–14. doi: 10.1007/s00038-013-0526-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuffield Council on Bioethics. London (UK):: 2007 [cited 2017 Apr 4]. Public health: ethical issues [Internet]. . Available from: http://nuffieldbioethics.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Public-health-ethical-issues.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Ramos Salas X. The ineffectiveness and unintended consequences of the public health war on obesity. Can J Public Health. 2015;106((2)):e79–e81. doi: 10.17269/cjph.106.4757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell K, McCullough L, Salmon A, Bell J. ‘Every space is claimed’: smokers’ experiences of tobacco denormalisation. Sociol Health Illn. 2010;32((6)):914–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren L, McIntyre L, Kirkpatrick S. Rose’s population strategy of prevention need not increase social inequalities in health. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39((2)):372–7. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels N. Equity and population health: toward a broader bioethics agenda. Hastings Cent Rep. 2006;36((4)):22–35. doi: 10.1353/hcr.2006.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P, Gruskin S. Defining equity in health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57((4)):254–8. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.4.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faden RR, Powers M. Health inequities and social justice: the moral foundations of public health. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2008;51((2)):151–7. doi: 10.1007/s00103-008-0443-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde M. Health and Welfare Canada; 1974 [Catalogue No. Ottawa (ON): A new perspective on the health of Canadians: a working document. pp. H31–1374]. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M, Rose G, Shipley M, Hamilton P. Employment grade and coronary heart disease in British civil servants. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1978;32((4)):244–9. doi: 10.1136/jech.32.4.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol. 1985;14((1)):32–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/14.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization; Geneva (CH): 1986. Ottawa charter for health promotion. p. 5 p. [Google Scholar]

- Epp J. Health and Welfare Canada; Ottawa (ON): 1986. Achieving health for all: A framework for health promotion. [Google Scholar]

- Mustard J, Frank J. Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, Population Health Program; Toronto (ON): 1991. The determinants of health. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M, Davey Smith G, Stansfeld S, et al. Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. Lancet. 1991;337((8754)):1387–93. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93068-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans R, Barer M, Marmor T, editors. Aldine de Gruyter; New York (NY): 1994. Why are some people healthy and others not? The determinants of health of populations. p. 378 p. [Google Scholar]

- Federal. Provincial and Territorial Advisory Committee on Population Health. Health Canada; 1994 [Catalogue No. Ottawa (ON): Strategies for population health: investing in the health of Canadians. pp. H39–316/1994E]. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton N, Bhatti T. Ottawa (ON):: 1996 [cited 2017 Apr 4]. Population health promotion: an integrated model of population health and health promotion [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ph-sp/php-psp/index-eng.php . [Google Scholar]

- Hayes M, Dunn J. Population health in Canada: a systematic review. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Policy Research Networks Inc. ; 1998 [CPRN Study No:H|01|]. [Google Scholar]

- Poland B, Coburn D, Robertson A, Eakin J. Wealth, equity and health care: a critique of a “population health” perspective on the determinants of health. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46((7)):785–98. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00197-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn D, Denny K, Mykhalovskiy E, McDonough P, Robertson A, Love R. Population health in Canada: a brief critique. Am J Public Health. 2003;93((3)):392–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.3.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]