Abstract

Introduction:

To address challenges Canadians face within their food environments, a comprehensive, multistakeholder, intergovernmental approach to policy development is essential. Food environment indicators are needed to assess population status and change. The Ontario Food and Nutrition Strategy (OFNS) integrates the food, agriculture and nutrition sectors, and aims to improve the health of Ontarians through actions that promote healthy food systems and environments. This report describes the process of identifying indicators for 11 OFNS action areas in two strategic directions (SDs): Healthy Food Access, and Food Literacy and Skills.

Methods:

The OFNS Indicators Advisory Group used a five-step process to select indicators: (1) potential indicators from national and provincial data sources were identified; (2) indicators were organized by SD, action area and data type; (3) selection criteria were identified, pilot tested and finalized; (4) final criteria were applied to refine the indicator list; and (5) indicators were prioritized after reapplication of selection criteria.

Results:

Sixty-nine potential indicators were initially identified; however, many were individual-level rather than system-level measures. After final application of the selection criteria, one individual-level indicator and six system-level indicators were prioritized in five action areas; for six of the action areas, no indicators were available.

Conclusion:

Data limitations suggest that available data may not measure important aspects of the food environment, highlighting the need for action and resources to improve system-level indicators and support monitoring of the food environment and health in Ontario and across Canada.

Keywords: nutrition policy; public health surveillance; healthy diet; food supply; health promotion,; environmental health; food environment;

Highlights

Key food environment features are included in the Ontario Food and Nutrition Strategy (OFNS), which aims to improve the health of Ontarians through policy and programs that promote healthy food systems and environments.

The OFNS Indicators Advisory Group used publicly available data to identify seven early indicators of healthy food access and food literacy; however, data availability and quality were limited.

Limitations suggest that available data may not measure important aspects of the food environment, highlighting the need for action and resources to improve systemlevel indicators and support monitoring of the food environment and health in Ontario and across Canada.

Health of Canadians and the food environment: the need for monitoring and surveillance

The contribution of diet to overall health and the development of cancer and other chronic disease is well documented.1,2,3 Yet, in general, Canadian diets are not consistent with recommended healthy eating patterns or advice.4,5,6,7 Additionally, a number of economic and social factors such as education, income and food insecurity influence diet and importantly affect Canadian health and health care costs.8,9,10

physical, economic, policy and sociocultural surroundings, opportunities and conditions that influence food choices and nutritional status.11,12 The food environment in Canada has changed substantially over recent decades with the growth of global food systems that include large-scale retail stores, fast food outlets and highly processed food products that may be negatively associated with health.13,14,15 These changes relate to the four key food environment features of (1) geographic food access; (2) availability; (3) affordability; and (4) food quality, which affect food choices and eating patterns16,17 and interact with the socioeconomic disparities18 that challenge the health of Canadians.

To address the challenges Canadians generally face within their food environments, a coordinated intergovernmental and multistakeholder approach to food policy development is essential and must consider the broader environmental influences that affect health and wellbeing. 11-12,19 Such an approach necessarily relies on evidence-informed decision making and the ability to track and compare outcomes of research, programs and policies related to the food environment. Recent international and Canadian reports have identified an important role for comprehensive and regular monitoring of the food environment, as well as diet, health and inequality measures to assess population status and tailor policy and program development.11-12,16 Although previous food environment assessments have been undertaken across Canada,16 there appears to be a lack of strategies that integrate food, agriculture and nutrition at the provincial and federal levels and that comprehensively include multiple factors related to the food environment and health. This report describes an Ontario initiative that integrates multiple sectors and factors, reviews available indicators and supports efforts across Canada to develop provincial and national strategies and surveillance systems to improve the food environment and Canadian health. A comprehensive description of the initiative is detailed elsewhere.20,21

The Ontario Food and Nutrition Strategy

The Ontario Food and Nutrition Strategy (OFNS) is an expert- and evidenceinformed strategy for improving the health and well-being of Ontarians through food policies and programs that also contribute to reducing the financial burden of chronic disease.21 The OFNS was collaboratively developed by individuals from 26 key organizations representing agriculture, food, health, education and Indigenous interests. Between 2009 and 2016, contributions from a broad group of stakeholders were also incorporated via numerous consultations. Fifty-nine organizations from academia; municipal, provincial and federal government; and public health and civil society provided feedback through in-person meetings and online consultations (237 online submissions were received). Based on this broad development process, the OFNS outlined a comprehensive, multistakeholder, coordinated approach to food policy development that works across the food, agriculture and nutrition sectors. The intended impact is to make healthy food the preferred and easiest choice for Ontarians by promoting diverse, healthy and resilient food systems and environments that improve diet and health, and contribute to an equitable and prosperous economy.

To achieve this, the OFNS identified three key strategic directions (SDs):21,p.6

Healthy Food Access (SD1): “access to and the means to choose and obtain safe, healthy, local and culturally acceptable food”;

Food Literacy and Skills (SD2): “information, knowledge, skills, relationships, capacity and environments to support healthy eating and make healthy choices where [Ontarians] live, gather, work, learn and play”; and

Healthy Food Systems (SD3): “diverse, healthy and resilient food systems that promote health and contribute to an equitable and prosperous economy.”

The three strategic directions encompass 25 targeted action areas in total, which are described in a separate report.21

While aspects of the food environment are included in all three OFNS strategic directions, this report describes work undertaken to identify early indicators to monitor and inform progress in the 11 action areas of Healthy Food Access (SD1) and Food Literacy and Skills (SD2). Key food environment features—food access, availability, affordability, quality—are clearly identifiable in SD1, and are also embedded in SD2 through restrictions on advertising, increased access to information on healthy eating and other environmental factors that influence food literacy and affect dietary outcomes and health.22,23,24,25 Salient aspects of the food environment should be measured using valid and reliable provincial indicators; given the relative newness of this field, it is expected that food environment definitions and indicators may evolve in future reports to encompass the complexity of factors that influence food choice.16,17

Process for identifying early indicators of the food environment

An OFNS Indicators Advisory Group (“the Advisory Group”) was formed with representation from municipal boards of health, provincial and national government agencies and academic and nongovernmental organizations to scan and identify existing data sources and determine the best available indicators of healthy food access and food literacy as the initial measures for Ontario. The project also aimed to identify data gaps and articulate considerations for future data collection to promote the robust monitoring and evaluation of issues that influence food access and literacy. Based on criteria from the National Health Service (UK), the Advisory Group defined indicators as succinct measures that describe and help users understand, compare and improve the current food system and environment.26,p.5

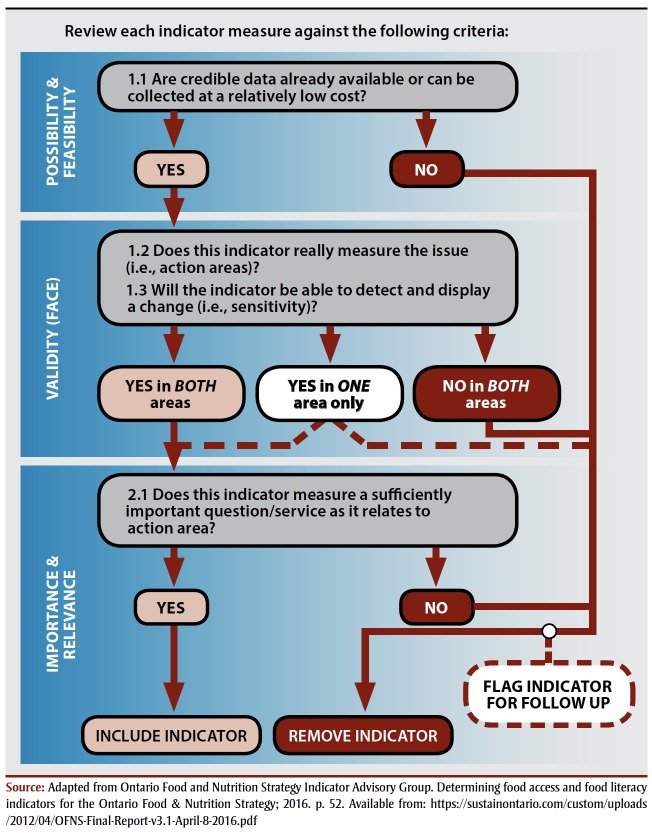

The Advisory Group used a five-step process to identify, review, select and prioritize indicators for Healthy Food Access, and Food Literacy and Skills (Figure 1), that included the use of quality criteria during indicator selection (Figure 2). Step 1 consisted of an environmental scan of national and provincial reports, other documents and data sources that provide system- level as well as behaviour- and knowledge-based data or indicators relevant to one or both OFNS strategic directions and their action areas. Although the intent was mainly to identify system-level indicators, data collection began with a broad set of available data in case systemlevel indicators were unavailable. Step 2 involved extracting and organizing possible indicators for each SD into detailed spreadsheets by action area and data type. Step 3 entailed identifying indicator selection criteria26,27,28 by pilot testing their application to a sample of potential indicators (done by a subgroup of the Advisory Group). Final criteria were based on fundamental issues of data possibility and feasibility, face validity and importance and relevance within a public health context. 29,30 Step 4 included using final selection criteria to create a short list of indicators for each strategic direction. Step 5 involved prioritizing indicators on the short list using a consensus-building technique after each Advisory Group subgroup member independently reapplied the selection criteria and ranked the importance of indicators within each action area. This process resulted in the final list of indicators for each strategic direction.

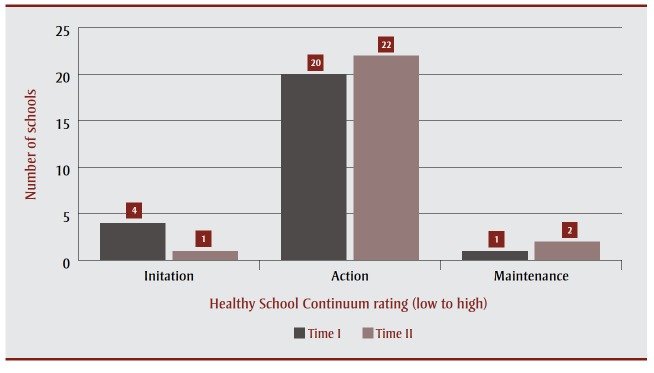

figure 1. Indicator selection process and outcomes for two strategic directions in the Ontario Food and Nutrition Strategy, 2016.

figure 2. Quality criteria and indicator selection pathway for two strategic directions in the Ontario Food and Nutrition Strategy, 2016.

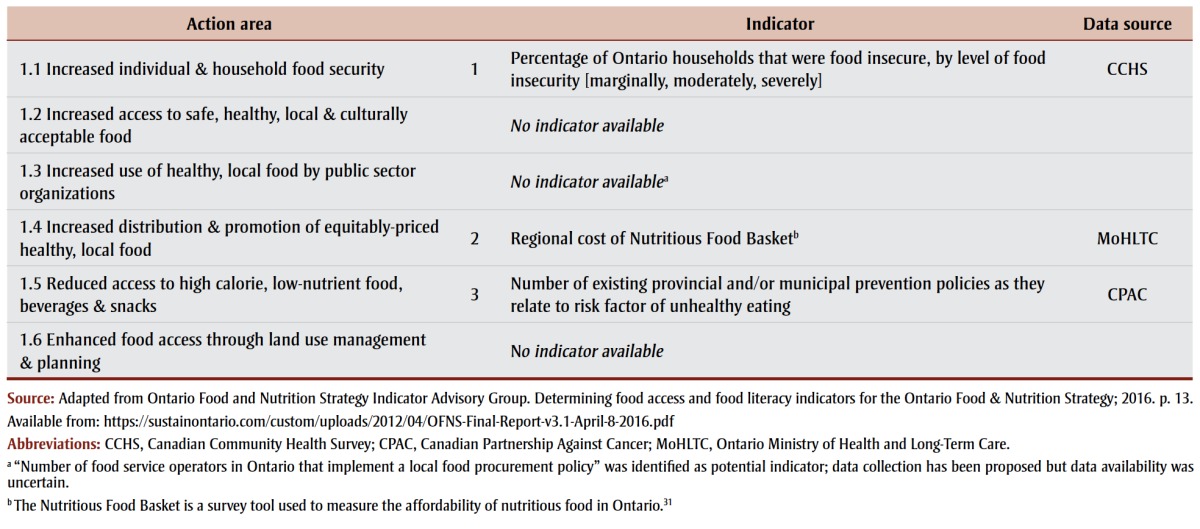

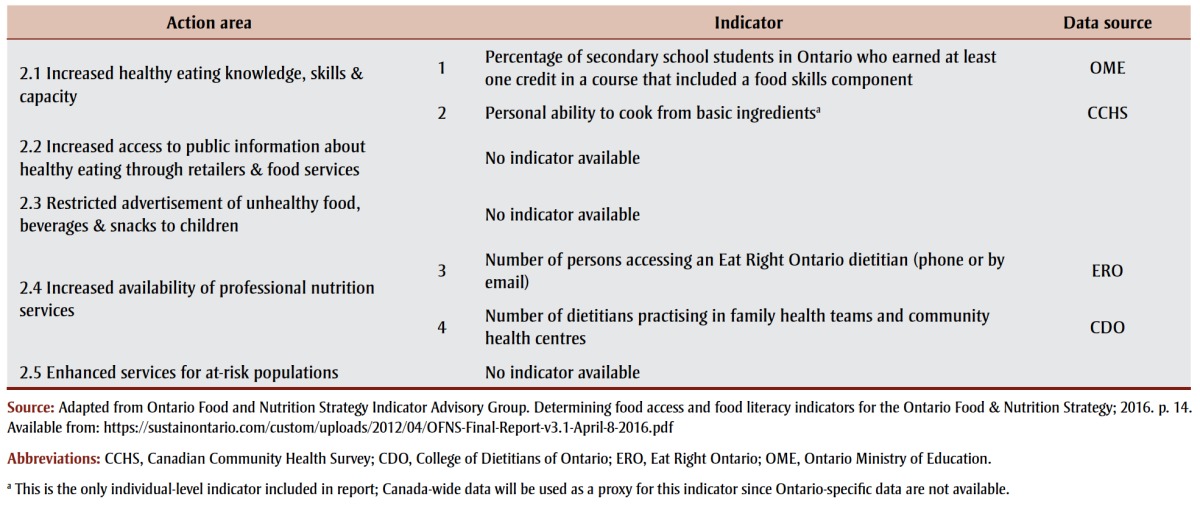

Overall, 69 indicators were proposed from the environmental scan and organized into 11 action areas. The initial assessment excluded 34 items that were predominantly measures of individual nutrition behaviour or knowledge, resulting in a long-list of 35 indicators. After first application of the selection criteria, 28 indicators remained. From these, six system-level indicators were prioritized as well as one individual-level “global” indicator of food skills (ability to cook from basic ingredients; SD2). Three prioritized indicators for Healthy Food Access included systemlevel measures of household food insecurity, cost of the Nutritious Food Basket31 and municipal and provincial healthy eating policies, in three of six action areas (Table 1). Four prioritized indicators for Food Literacy and Skills included three system-level measures of student food skills education, dietitian access and dietitian supply, and one individual-level measure of general cooking skills in two of five action areas (Table 2). For six of the 11 action areas, there were no indicators available. Overall, although certain early indicators of food access, literacy and the food environment were identified, the general scarcity of system-level data and the many data gaps suggest that the adequacy and scope of existing publicly available data to comprehensively measure and monitor important aspects of the food environment are limited.

TABLE 1. Action areas and indicators for the Healthy Food Access strategic direction (SD1) of the Ontario Food and Nutrition Strategy.

|

TABLE 2. Action areas and indicators for the Food Literacy and Skills strategic direction (SD2) of the Ontario Food and Nutrition Strategy.

|

Limitations and future considerations for identifying indicators in Ontario and beyond

A major challenge in identifying OFNS indicators was the need to rely on existing data sources, which revealed several limitations in data availability and quality. This led to the identification of early indicators that were often constrained (e.g. based on face validity rather than more robust validity criteria), as well as the overall dearth of system-level data for many action areas. Although national surveys were viewed as potential sources of proxy provincial data, they do not appear to include food environment variables other than food insecurity, suggesting an absence of system-level data at the national level as well.

Furthermore, although numerous indicators had been proposed after the initial document scan, most were not retained, including several that were considered downstream measures of specific dietary knowledge or behaviours (e.g. self-reported skills in peeling, chopping and slicing vegetables or fruits) rather than desired upstream indicators of the food system and environment. Overall, these limitations highlight the need for system-level provincial indicators that are diverse, robust and based on measures that have been rigorously tested for validity and reliability.17 Additionally, although members of the Advisory Group were aware that recent provincial initiatives had proposed to collect food environment data, as noted in the action area for increased use of healthy, local food in public sector organizations (Table 1), current data availability was uncertain. This suggests that improved communication and coordination will be needed among partners to collect and share relevant data and create a comprehensive monitoring plan.

Working within these data limitations, however, the Advisory Group prioritized indicators that they considered the “best available,” although these may not sufficiently assess critical aspects of the food environment, or adequately monitor its impact, trends or change. While this paper describes the process and challenges of selecting indicators for Ontario, it is useful to consider that other Canadian jurisdictions face similar issues related to the availability of regular, consistent and valid food environment data, as suggested in a recent report by Health Canada.16

Next steps for the Ontario Food and Nutrition Strategy

The Ontario Food and Nutrition Strategy21 was launched in January 2017 and will be implemented through a shared delivery model whereby stakeholder groups and partners lead and support work in selfidentified areas of interest and expertise. The seven indicators prioritized in this report will form the initial monitoring framework for two of the OFNS strategic directions. Dependent on funding, data for these indicators will be analyzed to provide a modest baseline assessment of food access, food literacy and the food environment in Ontario, and reanalyzed longitudinally to determine the extent of change over time. This initial monitoring will help identify where efforts and resources are needed to support improvements in surveillance and outcomes, including through the development of provincial and national policies. Opportunities for additional funding will be explored to support the identification of indicators for the third and final strategic direction, Healthy Food Systems, and advancement of strategies to encourage the systematic, ongoing collection of provincial and national data for all OFNS actions.

To our knowledge, few, if any, other provinces have developed comprehensive food, agriculture and nutrition strategies that address the complexity of contributions to the food environment and health. This shortcoming also appears to extend to the federal level, where separate (rather than integrated) healthy eating and agrifood policies are being developed.32,33 Nonetheless, the data limitations identified in this report may assist multiple stakeholders to advocate for robust surveillance systems that consider all or select aspects of OFNS action areas,21 particularly since many are shared with other provincial, national and international initiatives such as the Report Card on Healthy Food Environments and Nutrition for Children in Canada34 and the International Network for Food and Obesity/ non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support (INFORMAS).11-12 This overlap in effort will serve to enhance opportunities and synergies to create, test and implement valid and comprehensive measures of food access, food literacy and the food environment that will be able to monitor and inform provincial, national and international programs and ultimately improve the diet and health of Canadians.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ahalya Mahendra (Public Health Agency of Canada), Brian Cook (Toronto Public Health), Colleen Smith (Ag-Scape), Jocelyn Sacco (Public Health Ontario), June Matthews and Paula Dworatzek (Brescia University College at Western University), Leslie Whittington- Carter (Dietitians of Canada), Lisa Mardlin VandeWalle (Registered Dietitian, Private Practice), Lyndsay Davidson (Chatham Kent Public Health Unit), Rhona Hanning (University of Waterloo), and Ryan Turnbull (Eco-Ethonomics) for their contributions to the OFNS Indicators Advisory Group and their dedication to identifying and prioritizing indicators for this project.

This work was made possible by financial support from the Public Health Agency of Canada and in-kind support from Cancer Care Ontario and Ontario Public Health Association. Figures and tables were adapted with permission from the Ontario Food and Nutrition Strategy Group and the OFNS Indicators Advisory Group. Comprehensive descriptions of the strategy and the indicators work are provided elsewhere. 20,21

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors' contributions

RT, LR, EM, and BAB contributed to the design of the study; BAB, EM, RT, MRB, and LR performed data analysis and interpretation; BAB and EM drafted the manuscript; and BAB, EM, RT, MRB and LR revised for critical content. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Geneva (CH):: 2010 [cited 2016 Oct 24]. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010 [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd_report_full_en.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- World Cancer Research Fund. American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR). AICR; Washington: 2007. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. p. 537 p. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Seattle (WA):: 2012 [cited 2016 Oct 24]. 4 p. Global burden of disease (GBD) profile: Canada [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/country_profiles /GBD/ihme_gbd_country_report_canada.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Jessri M, Nishi SK, L’Abbé MR. Assessing the nutritional quality of diets of Canadian adults using the 2014 Health Canada surveillance tool tier system. Nutrients. 2016;7:10447–68. doi: 10.3390/nu7125543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessing the nutritional quality of diets of Canadian children and adolescents using the 2014 Health Canada Surveillance Tool Tier System. BMC Public Health [Internet]. Jessri M, Nishi SK, L’Abbé MR. 16:381 doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3038-5. . Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3038-5 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garriguet D. Canadians’ eating habits. Health Rep. 2009;18((2)):17–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garriguet D. Diet quality in Canada. Health Rep. 2009;20((3)):41–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick SI, Tarasuk V. Food insecurity is associated with nutrient inadequacies among Canadian adults and adolescents. J Nutr. 2008;138((3)):604–12. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.3.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarasuk V, Cheng J, de Oliveira C, Dachner N, Gundersen C, Kurdyak P. Association between household food insecurity and annual health care costs. CMAJ. 2015;187((14)):E429–E436. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.150234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald T, Rosella LC, Calzavara A, et al. Looking beyond income and education: socioeconomic status gradients among future high-cost users of health care. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49((2)):161–71. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinburn B, Vandevijvere S, Kraak V, et al. Monitoring and benchmarking government policies and actions to improve the healthiness of food environments: a proposed Government Healthy Food Environment Policy Index. Obes Rev. 2013;14 Suppl 1:24–37. doi: 10.1111/obr.12073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinburn B, Sacks G, Vandevijvere S, et al. INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support): overview and key principles. Obes Rev. 2013;14 Suppl 1:1–12. doi: 10.1111/obr.12087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro CA, Moubarac J-C, Cannon G, Ng SW, Popkin B. Ultra-processed products are becoming dominant in the global food system. Obes Rev. 2013;14 Suppl 2:21–8. doi: 10.1111/obr.12107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moubarac JC, Martins AP, Claro RM, Levy RB, Cannon G, Monteiro A. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and likely impact on human health. Evidence from Canada. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16((12)):2240–8. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012005009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrington WE, White E. Mortality outcomes with intake of fast-food items and sugar-sweetened drinks among older adults in the Vitamins and Lifestyle (VITAL) study. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19((18)):3319–26. doi: 10.1017/S1368980016001518. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1368980016001518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. Ottawa (ON):: 2013 [cited 2016 Oct 24]. Measuring the food environment in Canada [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.foodsecuritynews.com/resource-documents/MeasureFoodEnvironm_EN.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon RA, Reedy J, Morrissette MA, Lytle LA, Yaroch AL. Measures of the food environment: a compilation of the literature, 1990-2007. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36 Suppl 4:S124–S133. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent Institute. Ottawa (ON):: 2014 [cited 2016 Oct 24]. Haves and have-nots: deep and persistent wealth inequality in Canada [Internet]. . Available from: https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/broadbent/pages/32/attachments/original/1430002827/Haves_and_Have-Nots.pdf?1430002827 . [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes C, Jewell J, Allen K. A food policy package for healthy diets and the prevention of obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases: the NOURISHING framework. Obes Rev. 2013;14 Suppl 2:159–68. doi: 10.1111/obr.12098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Food and Nutrition Indicator Advisory Group. Toronto (ON):: 2017 [cited 2017 Oct 24]. Determining food access and food literacy indicators for the Ontario Food and Nutrition Strategy [Internet]. . Available from: https://sustainontario.com/custom/uploads/2012/04/OFNS-Final-Report-v3.1-April-8-2016.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Food and Nutrition Strategy Group. Toronto (ON):: 2017 [cited 2017 Feb 1]. Ontario food and nutrition strategy: a comprehensive evidence informed plan for healthy food and food systems in Ontario [Internet]. . Available from: http://sustainontario.com/work/ofns/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2017/07/Ontario_Food_and_Nutrition_Strategy_Report.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Vidgen HA, Gallegos D. Defining food literacy and its components. Appetite. 2014;76:50–9. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard A, Brichta J. Ottawa (ON):: 2013 [cited 2016 Oct 24]. What’s to eat: improving food literacy in Canada [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.conferenceboard.ca/e-library/abstract.aspx?did=5727 . [Google Scholar]

- Cullen T, Hatch J, Martin W, Higgins JW, Sheppard R. Food literacy: definition and framework for action. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2015;76((3)):140–5. doi: 10.3148/cjdpr-2015-010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenhall C. Ottawa (ON):: 2010 [cited 2016 Oct 24]. Improving cooking and food preparation skills: a synthesis of evidence to inform program and policy development [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/alt_formats/pdf/nutrition/child-enfant/cfps-acc-synthes-eng.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Pencheon D. Coventry (UK):: 2008 [cited 2016 Oct 24]. The good indicators guide: understanding how to use and choose indicators [Internet]. . Available from: https://www.k4health.org/sites/default/files/TheGoodIndicatorsGuide.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt MT, Roberts KC, Bennett TL, Driscoll ER, Jayaraman G, Pelletier L. Monitoring chronic diseases in Canada: the Chronic Disease Indicator Framework. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2014;34 Suppl 1:1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health Commission of Canada. Ottawa (ON):: 2015 [cited 2016 Oct 24]. Informing the future: mental health indicators for Canada [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/English/document/68796/informing-future-mental-health-indicators-canada . [Google Scholar]

- Rychetnik L, Frommer M, Hawe P, Shiell A. Criteria for evaluating evidence on public health interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56((2)):119–27. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.2.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron R, Jolin MA, Walker A, McDermott N, Gough M. Linking science and practice: toward a system for enabling communities to adopt best practices for chronic disease prevention. Health Promot Pract. 2001;2((1)):35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Ministry of Health Promotion. Toronto (ON):: 2010. Nutritious food basket guidance document [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/oph_standards/docs/guidance/nutritiousfoodbasket_gr.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Trudeau J. Ottawa (ON):: 2015 [cited 2017 Feb 1]. Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food mandate letter [Internet]. . Available from: http://pm.gc.ca/eng/minister-agriculture-and-agri-food-mandate-letter . [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Ottawa (ON):: 2016 [modified 2016 Oct 24; cited 2017 Feb 1]. Healthy eating strategy [Internet]. . Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/food-nutrition/healthy-eating-strategy.html . [Google Scholar]

- Olstad DL, Raine KD, Nykiforuk CI. Development of a report card on healthy food environments and nutrition for children in Canada. Prev Med. 2014;69:287–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]