Abstract

Imaging markers that are reliable, reproducible and sensitive to neurodegenerative changes in progressive multiple sclerosis (MS) can enhance the development of new medications with a neuroprotective mode-of-action. Accordingly, in recent years, a considerable number of imaging biomarkers have been included in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials in primary and secondary progressive MS. Brain lesion count and volume are markers of inflammation and demyelination and are important outcomes even in progressive MS trials. Brain and, more recently, spinal cord atrophy are gaining relevance, considering their strong association with disability accrual; ongoing improvements in analysis methods will enhance their applicability in clinical trials, especially for cord atrophy. Advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques (e.g. magnetization transfer ratio (MTR), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), spectroscopy) have been included in few trials so far and hold promise for the future, as they can reflect specific pathological changes targeted by neuroprotective treatments. Position emission tomography (PET) and optical coherence tomography have yet to be included. Applications, limitations and future perspectives of these techniques in clinical trials in progressive MS are discussed, with emphasis on measurement sensitivity, reliability and sample size calculation.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, progressive, imaging, outcome, trial

Introduction

During the last 20 years, over a dozen of disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) received the approval for the treatment of relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), being facilitated by screening the anti-inflammatory activity of putative treatments using active magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) lesions as outcomes in phase 2 trials. On the contrary, the paucity of active medications for both primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS) and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS) is striking. In view of this, the Progressive MS Alliance recently suggested to develop and to validate biomarkers of progression that could make clinical trials for progressive multiple sclerosis (MS) less time- and resource-consuming, when compared with conventional clinical measures.1 This could be achieved with the identification of reliable, reproducible and sensitive-to-change imaging outcomes.

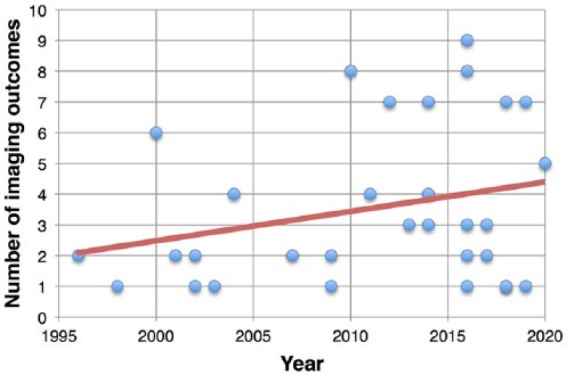

Several MRI measures reflect the neurodegenerative pathology of progressive MS and hold promise for clinical trial applications in this population. Along with the use of conventional MRI metrics (e.g. brain volume, lesion count and volume), advanced MRI techniques and optical coherence tomography (OCT) are also emerging as candidate imaging outcomes of MS progression. Indeed, the number of imaging outcomes included in clinical trials for progressive MS has almost doubled from 2.3 ± 1.5, in the decade 1996–2006, to 4.1 ± 2.6 in most recent years (2007 to current) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Clinical trials and imaging outcomes. Scatter plot shows the number of imaging outcomes used in clinical trials conducted from 1996 up to recent years (the expected conclusion date has been used for ongoing clinical trials).

In this review, we will discuss imaging biomarkers, which have been included in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials for progressive MS and those emerging for the future. Methodological and statistical drawbacks will be also discussed.

Brain lesion count and volume

Lesion counts were the first MRI-derived outcome for MS clinical trials and include the number of gadolinium-enhancing and new/enlarging T2 lesions, and their related volumes. Lesion measures are the best biomarker of active inflammation in MS, allowing the screen for early disease activity in phase 2 clinical trials in RRMS.2 On the contrary lesion-derived measures play a secondary – but not negligible – role in the study of progressive MS. In PPMS, the burden of T2-visible lesion load and of gadolinium-enhancing lesions is low, despite clinical severity3 and seems to have only a minimal impact on the disability accrual over time.4

MRI measures of focal brain lesions are the most common imaging metric in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials in progressive MS.5–30

Future clinical trials on progressive MS might include these outcomes if the presence of inflammation is expected and targeted. Indeed, trials might pick populations with relatively high inflammatory activity, depending on inclusion/exclusion criteria (e.g. 24.7%–27.5% of PPMS patients presented with Gd-enhancing lesions at baseline visit of the ORATORIO trial).7 However, clinical outcomes might be difficult to predict based on results on lesion measures. Indeed, the use of DMTs specifically designed for RRMS in clinical trials in progressive MS can result in a positive effect on lesion count and volume measures but not on neurodegenerative clinical (e.g. disability progression) and imaging outcomes (e.g. brain and spinal cord (SC) atrophy), as occurred in the INFORMS trial.5,31 Similarly, use of interferon-beta in SPMS was associated with fewer active lesions, but no effect was established on clinical disability.32

Global and regional brain atrophy

Brain atrophy is detectable on MRI scans from the earliest clinical stages of MS and is a biomarker of irreversible neurodegenerative processes.33 Global brain atrophy has been associated with the degree of disability in large cohorts of both RR and progressive MS.34,35 Besides, improvements in MRI post-processing have allowed to segment white matter (WM) and grey matter (GM) (both cortical and deep) separately, allowing refinement of association with clinical features.36,37 Regional volumes might show a greater change over time,12 resulting in higher sensitivity and smaller sample size when compared with global measures.38

Intriguingly, brain atrophy has not been associated with relapse risk in RRMS, suggesting that atrophy is probably driven more by (possibly independent) neurodegenerative changes than inflammatory lesions, which further support the use of this measure in progressive MS.33

There are several methods to quantify whole-brain atrophy. In general, brain tissue volume needs to be normalized for head size, and longitudinal changes can be detected using registration- and segmentation-based techniques. Registration-based methods compare longitudinally acquired images and measure changes in brain surface; structural image evaluation using normalization of atrophy (SIENA) is the most popular example. Segmentation-based techniques measure brain volume on a single scan and then determine change over time indirectly and include brain parenchymal fraction (BPF) (which is the ratio of brain parenchymal volume to the total volume within the brain surface contour).33,39 In comparative analyses, brain atrophy measured with registration-based techniques showed better reproducibility40 and higher power to detect treatment effect, when compared with segmentation-based.41,42

Whole-brain atrophy has been included in several phase 2 and 3 clinical trials in progressive MS as primary8,9,12,15,43–46 or secondary outcome (Table 1).5–7,11,13,14,16–18,21–24,26,30,50–52

Table 1.

Clinical trials in progressive MS using imaging outcomes.

| Study | Design | Intervention | Brain atrophy | Regional brain atrophy | T2 lesions | T2 lesion volume | T1 lesions | Gd+ lesions | CUA lesions | MTR | DTI | fMRI | Spinal cord | OCT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPMS | FUMAPMS | Phase 2 N = 90 |

Dimethyl fumarate vs placebo | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | ||||

| IPPoMS | Phase 2

N = 85 |

Idebenone | O | ||||||||||||

| ARPEGGIO | Phase 2

N = 374 |

Laquinimod vs placebo | O | O | |||||||||||

| ORATORIO, Montalban et al.7 | Phase 3

N = 732 Duration = 120 weeks |

Ocrelizumab 600 mg vs placebo (2:1) | P | P | P | ||||||||||

| INFORMS, Lublin et al.5 | Phase 3

N = 823 Duration = 36 months |

Fingolimod 0.5 mg vs placebo (1:1.5) | N | P | P | P | N | ||||||||

| OLYMPUS, Hawker et al.11 | Phase 2/3

N = 439 Duration = 96 weeks |

Rituximab 1000 mg vs placebo | N | N | |||||||||||

| Montalban et al.47 | Phase 2

N = 71 Duration = 24 months |

Interferon beta-1b (250 μg on alternate days) vs placebo | N | ||||||||||||

| PROMISE, Wolinsky et al.27 | Phase 3

N = 943 Duration = 36 months |

Glatiramer acetate vs placebo | N | N | |||||||||||

| Leary et al.48 | Phase 2

N = 50 Duration = 24 months |

Interferon beta-1a (30 μg vs 60 μg per week) vs placebo | N | ||||||||||||

| Kalkers et al.49 | Phase 2

N = 16 Duration = 24 months |

Placebo for 12 months vs riluzole for following 12 months (2 × 50 mg per day) | N | ||||||||||||

| SPMS | CBAF312A2304 | Phase 3

N = 1651 |

Siponimod vs placebo | O | O | O | O | O | |||||||

| NCT02057159 | Phase 2/3 | NeuroVax vs placebo | O | ||||||||||||

| MS-SMART | Phase 2

N = 445 |

Amiloride vs riluzole vs fluoxetine vs placebo (1:1:1:1) | O | ||||||||||||

| Abili-T43 | Phase 2

N = 183 |

Tcelna vs placebo | O | ||||||||||||

| B7493-W | Phase 2/3

N = 54 |

Lipoic acid vs placebo | O | ||||||||||||

| ASCEND23 | Phase 3

N = 889 |

Natalizumab 300 mg vs placebo | O | O | O | ||||||||||

| MS-STAT, Chataway et al.8 | Phase 2

N = 140 Duration = 24 months |

Simvastatin 80 mg vs placebo (1:1) | P | P | N | ||||||||||

| NCT00395200, Connick et al.14 | Phase 2

N = 10 Duration = 20 + 10 months |

Autologous mesenchymal stem cells transplantation, open label (before vs after treatment) | N | P | N | N | N | N | |||||||

| MAESTRO, Freedman et al.21 | Phase 3

N = 612 Duration = 2 years |

MBP8298 500 mg vs placebo | N | N | N | N | |||||||||

| Lamotrigine trial, Kapoor et al.12 | Phase 2

N = 120 Duration = 2 years |

Lamotrigine 400 mg vs placebo (1:1) | N | N | N | N | N | ||||||||

| ESIMS, Hommes et al.6 | Phase 3

N = 318 Duration = 27 months |

IVIG vs placebo (1:1) | P | N | |||||||||||

| NA-SPMS, The North American Study Group on Interferon beta-1b in Secondary Progressive MS19 | Phase 3

N = 939 Duration = 3 years |

Interferon beta-1b 250 μg and 160 μg/m2 vs placebo (1:1:1) | P | ||||||||||||

| IMPACT, Cohen et al.28 | Phase 3

N = 436 Duration = 24 months |

Interferon beta-1a 60 µg/week IM vs placebo | P | P | |||||||||||

| SPECTRIMS, Li et al.20 | Phase 3

N = 618 Duration = 3 years |

Interferon beta-1a 44 μg and 22 μg vs placebo | P | P | P | ||||||||||

| Cladribine MRI Study Group, Rice et al.25 | Phase 2

N = 159 Duration: 24 months |

Cladribine 0.7 mg/kg and 2.1 mg/kg vs placebo | N | P | P | ||||||||||

| EU-SPMS, European Study Group on Interferon beta-1b in Secondary Progressive MS10 | Phase 3

N = 718 Duration = 36 months |

Interferon beta-1b vs placebo (1:1) | P | ||||||||||||

| Karussis et al.29 | Phase 2

N = 30 Duration = 6 months |

Linomide 2.5 mg vs placebo | P | P | |||||||||||

| PPMS and SPMS | SPRINT-MS, Fox et al.15 | Phase 2

N = 255 Duration = 96 weeks |

Ibudilast 100 mg vs placebo (1:1) | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | ||||

| NCT01144117, Schreiber et al.17 | Phase 2

N = 50 Duration = 24 weeks |

Erythropoietin 48000 UI vs placebo | N | N | |||||||||||

| ACTiMuS, Rice et al.24 | Phase 2

N = 80 |

Early vs late autologous bone marrow cellular therapy | O | O | O | O | O | O | |||||||

| FLUOX-PMS, Cambron et al.16 | Phase 2

N = 120 Duration = 108 weeks |

Fluoxetine 40 mg vs placebo | O | O | O | O | O | ||||||||

| NAPMS, Romme Christensen et al.18 | Phase 2

N = 24 Duration = 60 weeks |

Natalizumab 300 mg open label (before vs after treatment) | P | P | N | P | P | P | |||||||

| CUPID, Zajicek et al.,26 | Phase 3

N = 498 Duration = 3 years |

Dronabinol vs placebo (1:1) | N | N | N |

MS: multiple sclerosis; Gd+ lesions: Gadolinium-enhancing lesions; CUA: combined unique active; MTR: magnetization transfer ratio; DTI: diffusion tensor imaging; fMRI: functional magnetic resonance imaging; OCT: optical coherence tomography; PPMS: primary progressive multiple sclerosis; SPMS: secondary progressive multiple sclerosis; IM: intramuscular; IVIG: intravenous immunoglobulin G.

Phase 2 and 3 clinical trials conducted in PPMS, SPMS and mixed populations (PPMS and SPMS) of patients, with study design, intervention and results on different MRI outcomes (O: ongoing; P: positive treatment effect; N: no effect detected).

The first trial demonstrating a beneficial effect on global brain atrophy (using simvastatin) was a phase 2 trial study in SPMS.8 Positive results have been reported also in the phase 3 ORATORIO study in PPMS.7 A number of ongoing trials are measuring global brain atrophy, and their results should become available over the next several years (Table 2).

Table 2.

Phase 3 clinical trials in progressive MS evaluating brain atrophy.

| Clinical trials | Sample size recruited (treatment vs placebo) | Volume change (treatment vs placebo) | Duration | Methods | Effect size potentially detectable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORATORIO, Montalban et al.7 | 488 vs 244 (PPMS) | PBVC: −0.90% ± 1.12 vs −1.09% ± 1.15 (p = 0.02) | From week 24 to 120 | SIENA | 26.7% |

| INFORMS, Lublin et al.5 | 336 vs 487 (PPMS) | PBVC: −1.49% ± 1.35 vs −1.53% ± 1.35 (p = 0.673) | From baseline to month 36 | SIENA | 15.8% |

| CUPID, Zajicek et al.26 | 329 vs 164 (182 vs 91 in the MRI sub-study population) (PPMS and SPMS) | PBVC: −1.95% ± 1.51 vs −1.82% ± 1.47 (p = 0.94) | From baseline to year 3 | SIENA | 33.5% |

| OLYMPUS, Hawker et al.11 | 292 vs 147 (PPMS) | Volume change: −10.8 cm3 ± 40.3 vs −9.9 cm3 ± 37.0 (p = 0.62) | From baseline to week 96 | BPF | >99% |

| ESIMS, Fazekas et al.51 | 159 vs 159 (SPMS) | PCF: −0.62% ± 0.88 vs −0.88% ± 0.91 (p = 0.0093) | From baseline to month 27 | Six-slice volume | 32.5% |

MS: multiple sclerosis; PPMS: primary progressive multiple sclerosis; PBVC: percentage of brain volume change; SIENA: structural image evaluation using normalization of atrophy; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; SPMS: secondary progressive multiple sclerosis; BPF: brain parenchymal fraction; PCF: partial cerebral fraction.

Phase 3 clinical trials in progressive MS which included brain atrophy as outcome measure. Characteristics of trials (sample size, duration) and of MRI measures (results and technique applied) are reported. The effect size potentially detectable has been calculated based on placebo arm results and sample.

Regional brain atrophy has been used as secondary outcome in a few trials, where measures were obtained from GM, WM,12 putamen, thalamus and optic nerve.14 Considering that MS does not affect the brain uniformly, the detection of regional pathology might be predictive of more specific clinical features, when compared with whole-brain measures.53 However, standardization of software for analysis is needed to make widespread application in clinical trials possible.54

Overall, measures of global and regional brain atrophy are gaining relevance in clinical trials on progressive MS, reflective of improvements in measurement techniques allowing good reproducibility and sensitivity to change. Nevertheless, there are several possible limitations, including changes in magnet, gradients, coils, distortion corrections and image-contrast changes. Patients treated with anti-inflammatory treatments have a slight decrease in the brain volume in the first 6–12 months (pseudoatrophy), compared with placebo, due to the resolution of inflammation and oedema.55,56 A possible solution is to re-baseline subjects after 6 months,57,58 although longer periods may be required for more toxic types of treatment (e.g. chemotherapy during bone marrow transplantation).59 However, rebaselining carries the risk of losing power because of reduced time of observation on treatment. In the OPERA II trial (one of the two phase 3 trials for ocrelizumab in RRMS), statistical significance in brain volume change was lost when analysing data from week 24 to 96, instead of baseline to week 96.60

A reversible fluctuation of brain volumes can also occur because of variations in dehydration status.61

Advanced MRI techniques

Conventional neuroimaging techniques lack specificity with regard to different pathophysiological substrates of MS and are not able to explain the heterogeneous and long-term clinical evolution of the disease.58,62–64 Advanced MRI techniques, such as magnetization transfer ratio (MTR), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), may provide higher pathological specificity for the more destructive aspects of the disease (i.e. demyelination and neuroaxonal loss) and be more closely associated with clinical correlates.55,65 Moreover, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is contributing to the definition of the role of cortical reorganization after MS tissue damage.37

MTR values reflect the efficiency of the magnetization exchange between mobile protons in tissue water and those bound to the macromolecules, such as myelin. MTR has been associated with disease progression in PPMS.35,66 In view of this, MTR has been included in several clinical trials in progressive MS and has been measured in GM, WM, T2 lesions, putamen, thalamus and optic nerve.13–15,18

DTI measures brain tissue microstructure by the exploitation of the properties of water diffusion. From the tensor, it is possible to calculate the magnitude of diffusion, reflected by mean diffusivity (MD), and diffusion anisotropy, which is a measure of tissue organization, generally expressed as fractional anisotropy (FA). In line with this, MD is increased and FA is decreased in T2 lesions, WM and GM from MS patients.67,68 DTI has been assessed across multiple scanners/platforms and is suitable for multi-centre studies.69,70 DTI is the most frequently used advanced MRI metric in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials in progressive MS, and is able to detect significant variations in brain microstructure during typical trial duration.18 MD and FA have been measured in pyramidal tracts, WM, GM and lesions in different trials in progressive MS.13,15,16,18,24 More specific measures such as axial and radial diffusivity can be calculated as measures of the mobility of water along and perpendicular to axons (reflecting axonal density and demyelination, respectively);65 however, they have not been included in clinical trials in progressive MS so far.

fMRI provides signal related to brain activation based on blood oxygen consumption and blood flow in the brain and has only been included in a single clinical trial on progressive MS.24

MRS can measure brain levels of several metabolites.71,72 The most commonly measured is total N-acetyl-asparate (NAA), a marker of axonal loss and metabolic dysfunction.73 NAA has been included in a few clinical trials in RRMS74 and one in PPMS.75

Spinal cord atrophy

SC atrophy is a common and clinically relevant aspect of progressive MS. A reduction in the cross-sectional area (CSA) of the SC over time is thought to reflect the development of atrophy (i.e. demyelination and neuronal/axonal loss).76,77

In clinically definite MS, the rate of cord atrophy has been reported to vary between 1% and 5% per year.77–81 Higher rates were found in progressive patients.77,82 Development of cord atrophy is considered to be one of the main substrates of disability accumulation. It can account for 77% of disability progression after 5 years.83–85

A few clinical trials in progressive MS have included SC atrophy as outcome measure (Table 1).12,13,24,31,47–49 Its more widespread use has been hampered by challenges to obtain high reproducibility and responsiveness to changes when measuring such a small structure. Small absolute changes in SC area are difficult to detect in a multi-centre setting, where there may be a great variability of imaging protocols and scanners.40 The acquisition of high-quality SC MRI can be affected by artefacts (e.g. breathing, pulsation of blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)), and this may limit the precision of SC atrophy measurements. As a consequence, sample size estimates obtained for current measurement techniques are fairly large and generally prohibitive, when compared with brain atrophy. Development of registration-based techniques to measure SC atrophy may address this concern as will be discussed below.86

Position emission tomography

Position emission tomography (PET) is a quantitative imaging technique, which investigates cellular and molecular processes in vivo using positron-emitting molecules, ideally binding a selective target.72,87,88 As MS is a complex and multifactorial disease, various radioligands have been tested. Amyloid tracers, measuring myelin loss and repair, and11 C-flumazenil, reflecting neuronal integrity, might be of interest for clinical trials on neuroprotective compounds.63,88–91

To date, no large MS clinical trials have included PET, reflecting its invasive nature and high costs. In the future, the development of standardized and less-expensive procedures might represent a trigger for the application of this technique in small phase 1 and 2a clinical trials.6

OCT

OCT is a non-invasive method to obtain high spatial resolution images of the retina, measuring retinal nerve fibre layer (RNFL) thickness and macular volume.

RNFL is thinner in patients with MS than in healthy controls, even in patients with MS who have not experienced episodes of optic neuritis.92 Therefore, OCT measures a more diffuse pathological process which better corresponds to overall central nervous system damage.93,94

RNFL and macular volume have been included in a few clinical trials on progressive MS (Table 1),14–16,24 so far without demonstrable neuroprotective effects.

OCT is a fast, non-invasive, easy-to-use imaging method producing quantitative measures reliably, with great potential in MS for testing neuroprotective strategies over a short time frame.33 Like brain volume, RNFL is sensitive to biological variations. However, there is the need for high-quality acquisitions and appropriate image processing, performed by trained examiners following specific consensus criteria.

Design issues

Measurement sensitivity

Quantitative MRI measures are strongly dependent not only on acquisition parameters but also on processing methods, presenting with different sensitivity to change, reproducibility and measurement error.

Clinical trials results can be affected by the analysis.41 For instance, in a clinical trial of teriflunomide in RRMS, changes were measured by BPF, a segmentation-based technique, and no significant effect was found initially.95 However, in a post hoc analysis, the use of a registration-based automated technique (SIENA) revealed that teriflunomide was associated with significant reductions in brain volume loss.96

Similarly, the conventional way of estimating SC atrophy is using segmentation-based methods, such as the cervical cord CSA97,98 and the upper cervical cord area (UCCA),99 that are measured at each time point with subsequent calculation of percentage change between time points. More recently, GBSI (generalized boundary shift integral) has been suggested as a novel registration-based method to estimate cervical SC atrophy directly between scans, possibly reducing sample sizes.86

The number of observations over time can increase sensitivity to change. However, at least for brain atrophy, the effect of increasing the number of observations is modest, when compared with the effect of increasing the duration of follow-up.100

Sample size

Sample size calculation is a pivotal aspect of planning clinical trials and is based on the primary outcome of the study, generally being imaging for phase 2 and clinical for phase 3 trials.101,102 Imaging outcome measures are often included as secondary or exploratory variables in all patients in phase 3 clinical trials, even though they might require a smaller sample size to detect significant difference. A caveat though is that the size of the treatment effect may differ between clinical and imaging outcomes; that is, 30% reduction in rate of brain volume may not equate in 30% reduction in disability progression.

In order to further explore this issue, we estimated the treatment effect on brain atrophy which could have been detected in populations recruited in phase 3 clinical trials in progressive MS (Table 2), based on the actual sample size and the measured rates of brain atrophy in the placebo arm (we accepted a power of 80% and the α error was set at 0.05). Most recent studies would have been able to detect 15%–30% treatment effects on brain atrophy,5,7,26 in line with actual detected statistical effect (17.5% relative difference in the ORATORIO trial).

Inclusion criteria can also impact sample size. For instance, in RRMS populations, the rate of inflammatory activity is high, and measures of inflammatory activity (new or enlarging T2 lesions, new T1 lesions and Gd-enhancing lesions) can lead towards relatively lower sample sizes, compared with progressive MS.103,104 For instance, when considering the number of enhancing lesions, the detection of 50% treatment effect for interferon-beta treatment requires about 120 patients per arm in RRMS trials and a threefold number in SPMS.105 By contrast, use of imaging markers more specific for progressive features (e.g. brain atrophy) will reduce the sample size needed in clinical trials in PPMS and SPMS. Advanced MRI techniques, such as MTR, might also require smaller sample sizes,106,107 in particular when trials with neuroprotective agents are conducted in selected populations.

Sample size can be affected also by variability of imaging outcomes. For instance, BPF measurement can have up to 0.00283% variance due to patient repositioning, physiological variations and inflammatory lesion occurrence.108 Measurement precision can affect the standard deviation of the measure which is a major determinant of the sample size.42 Increasing the number of scans performed in clinical trials and improving imaging analysis techniques (e.g. registration vs segmentation) can reduce these sources of variability and, accordingly, sample size.

Overall, DMTs can have a specific effect on each MRI outcome and thus the sample size should be estimated depending on the expected efficacy profile in the selected population. As such, MRI may be particularly useful in early-phase clinical studies on novel therapeutic agents, where drugs can be easily screened before they are taken forward to larger scale studies,109 as is common practice for anti-inflammatory drugs in phase 2 RRMS studies.

Conclusion and future perspectives

Progressive MS represents a unique opportunity for studying imaging markers of neurodegeneration, with equal bearing on relapsing forms of the disease. Several imaging candidates hold promise for filling the unmet need of biomarkers in progressive MS, by capturing the effect on neurodegeneration, although inflammatory markers remain important in this stage of the disease. Brain volume loss is the best examined and most robust outcome with attainable sample sizes and first positive results, though treatment effects tend to be more modest than those seen for inflammatory MRI markers. Brain volume is already being applied as primary outcome measure in phase 2 trials and as secondary exploratory measure in phase 3 trials in progressive MS. Results from these trials will help establish the importance of brain atrophy in tracking MS progression.46 SC MRI holds great promise for future trials due to higher rates of atrophy and better sensitivity to change compared with brain volume changes. However, robust application in clinical trials requires implementation of techniques with lower measurement noise, such as registration-based methods; in part, these can be validated using historical data sets. Advanced MRI measures (such as MTR, DTI and fMRI), due to their greater specificity, might shed light on mechanisms of action of new medications and should be included when clinical trials aim at exploring drug potentials for neuroprotection and tissue repair. In clinical trial design, the inclusion/exclusion of patients with specific MRI characteristics might help in identifying groups who are more likely to respond to a given medication and, so, in further reducing the sample size needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Professors Olga Ciccarelli, Robert J Fox, Alex Rovira and Bruno Stankoff for sharing their slides presented at the ECTRIMS Focused Workshop ‘Advancing Trial Design in Progressive Multiple Sclerosis’, for the preparation of the present manuscript. This review is part of a special issue derived from the 5th Focused ECTRIMS Workshop, ‘Advancing Trial Design in Progressive Multiple Sclerosis’, held in Rome, Italy, on 9–10 March 2017. The authors acknowledge the contributions of workshop attendees. F.B. is supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at UCLH.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Marcello Moccia, NMR Research Unit, Queen Square MS Centre, UCL Institute of Neurology, University College London, London, UK; Multiple Sclerosis Clinical Care and Research Centre, Department of Neuroscience, Reproductive Sciences and Odontostomatology, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy.

Nicola de Stefano, Department of Medicine, Surgery and Neuroscience, University of Siena, Siena, Italy.

Frederik Barkhof, NMR Research Unit, Queen Square MS Centre, UCL Institute of Neurology, University College London, London, UK; Translational Imaging Group, UCL Institute of Healthcare Engineering, University College London, London, UK; Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

References

- 1. Zaratin P, Comi G, Coetzee T, et al. Progressive MS alliance industry forum: Maximizing collective impact to enable drug development. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2016; 37: 808–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sormani MP, Bruzzi P. MRI lesions as a surrogate for relapses in multiple sclerosis: A meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12: 669–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miller D, Leary S. Primary-progressive multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2007; 6: 903–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Khaleeli Z, Ciccarelli O, Mizskiel K, et al. Lesion enhancement diminishes with time in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2010; 16: 317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lublin F, Miller DH, Freedman MS, et al. Oral fingolimod in primary progressive multiple sclerosis (INFORMS): A phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 387: 1075–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hommes OR, Sørensen PS, Fazekas F, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: Randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2004; 364: 1149–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Montalban X, Hauser SL, Kappos L, et al. Ocrelizumab versus placebo in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 209–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chataway J, Schuerer N, Alsanousi A, et al. Effect of high-dose simvastatin on brain atrophy and disability in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (MS-STAT): A randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2014; 383: 2213–2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. ClinicalTrials.gov. A phase 2 clinical study in subjects with primary progressive multiple sclerosis to assess the efficacy, safety and tolerability of two oral doses of laquinimod either of 0.6 mg/day or 1.5 mg/day (experimental drug) as Compared to Placebo, 2016, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02284568

- 10. Placebo-controlled multicentre randomised trial of interferon β-1b in treatment of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. European Study Group on Interferon beta-1b in secondary progressive MS. Lancet 1998; 352: 1491–1497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hawker K, O’Connor P, Freedman MS, et al. Rituximab in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis: Results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Ann Neurol 2009; 66: 460–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kapoor R, Furby J, Hayton T, et al. Lamotrigine for neuroprotection in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial. Lancet Neurol 2010; 9: 681–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. ClinicalTrials.gov. Dimethyl fumarate treatment of primary progressive multiple sclerosis (FUMAPMS), 2016, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02959658

- 14. Connick P, Kolappan M, Crawley C, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: An open-label phase 2a proof-of-concept study. Lancet Neurol 2012; 11: 150–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fox RJ, Coffey CS, Cudkowicz ME, et al. Design, rationale, and baseline characteristics of the randomized double-blind phase II clinical trial of ibudilast in progressive multiple sclerosis. Contemp Clin Trials 2016; 50: 166–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cambron M, Mostert J, Haentjens P, et al. Fluoxetine in progressive multiple sclerosis (FLUOX-PMS): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014; 15: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schreiber K, Magyari M, Sellebjerg F, et al. High-dose erythropoietin in patients with progressive multiple sclerosis: A randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Mult Scler 2017; 23: 675–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Romme Christensen J, Ratzner R, Bornsen L, et al. Natalizumab in progressive MS. Neurology 2014; 82: 1499–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Panitch H, Miller A, Paty D, et al. ; The North American Study Group. Interferon beta-1b in secondary progressive MS: Results from a 3-year controlled study. Neurology 2004; 63: 1788–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li DKB, Zhao GJ, Paty DW. Randomized controlled trial of interferon-beta-1a in secondary progressive MS: MRI results. Neurology 2001; 56: 1505–1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Freedman MS, Traboulsee A, Bar-Or A, et al. A phase III study evaluating the efficacy and safety of MBP8298 in secondary progressive MS. Neurology 2011; 77: 1551–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. ClinicalTrials.gov. Exploring the efficacy and safety of siponimod in patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (EXPAND), https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01665144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23. ClinicalTrials.gov. A clinical study of the efficacy of natalizumab on reducing disability progression in participants with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (ASCEND in SPMS), https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01416181

- 24. Rice C, Marks D, Ben-Shlomo Y, et al. Assessment of bone marrow-derived Cellular Therapy in progressive Multiple Sclerosis (ACTiMuS): Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2015; 16: 463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rice GP, Filippi M, Comi G. Cladribine and progressive MS: Clinical and MRI outcomes of a multicenter controlled trial. Cladribine MRI Study Group. Neurology 2000; 54: 1145–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zajicek J, Ball S, Wright D, et al. Effect of dronabinol on progression in progressive multiple sclerosis (CUPID): A randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12: 857–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wolinsky J, Narayana P, O’Connor P, et al. Glatiramer acetate in primary progressive multiple sclerosis: Results of a multinational, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Neurol 2007; 61: 14–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cohen J, Cutter G, Fischer J, et al. Benefit of interferon beta-1a on MSFC progression in secondary progressive MS. Neurology 2002; 59: 679–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Karussis DM, Lehmann D, Linde A. Treatment of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis with the immunomodulator linomide: A double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study with monthly magnetic resonance imaging evaluation. Neurology 1996; 47: 341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. ClinicalTrials.gov. A study of NeuroVaxTM, a therapeutic TCR peptide vaccine for SPMS of multiple sclerosis, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02057159

- 31. Yaldizli Ö, MacManus D, Stutters J, et al. Brain and cervical spinal cord atrophy in primary progressive multiple sclerosis: Results from a placebo-controlled phase III trial (INFORMS). In: ECTRIMS, https://onlinelibrary.ectrims-congress.eu/ectrims/2015/31st/116684/oezguer.yaldizli.brain.and.cervical.spinal.cord.atrophy.in.primary.progressive.html

- 32. La Mantia L, Vacchi L, Rovaris M, et al. Interferon β for secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013; 84: 420–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ontaneda D, Fox RJ. Imaging as an outcome measure in multiple sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics 2017; 14: 24–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rovaris M, Judica E, Sastre-Garriga J, et al. Large-scale, multicentre, quantitative MRI study of brain and cord damage in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2008; 14: 455–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Khaleeli Z, Ciccarelli O, Manfredonia F, et al. Predicting progression in primary progressive multiple sclerosis: A 10-year multicenter study. Ann Neurol 2008; 63: 790–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fisniku LK, Chard DT, Jackson JS, et al. Gray matter atrophy is related to long-term disability in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2008; 64: 247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rocca MA, Absinta M, Filippi M. The role of advanced magnetic resonance imaging techniques in primary progressive MS. J Neurol 2012; 259: 611–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Healy B, Valsasina P, Filippi M, et al. Sample size requirements for treatment effects using gray matter, white matter and whole brain volume in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009; 80: 1218–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rudick R, Fisher E, Lee J, et al. Use of the brain parenchymal fraction to measure whole brain atrophy in relapsing-remitting MS. Multiple Sclerosis Collaborative Research Group. Neurology 1999; 53: 1698–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Durand-Dubief F, Belaroussi B, Armspach JP, et al. Reliability of longitudinal brain volume loss measurements between 2 sites in patients with multiple sclerosis: Comparison of 7 quantification techniques. Am J Neuroradiol 2012; 33: 1918–1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sormani M, Rovaris M, Valsasina P, et al. Measurement error of two different techniques for brain atrophy assessment in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2004; 62: 1432–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Anderson VM, Fernando KT, Davies GR, et al. Cerebral atrophy measurement in clinically isolated syndromes and relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis: A comparison of registration-based methods. J Neuroimaging 2007; 17: 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. ClinicalTrials.gov. Study of Tcelna (Imilecleucel-T) in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (Abili-T), https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01684761

- 44. ClinicalTrials.gov. Lipoic acid for secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (MS), https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01188811

- 45. ClinicalTrials.gov. MS-SMART: Multiple sclerosis-secondary progressive multi-arm randomisation trial (MS-SMART), 2016, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01910259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46. Barkhof F, Giovannoni G, Hartung H, et al. ARPEGGIO: A randomized, placebo-controlled study to evaluate oral laquinimod in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS). Neurology 2015; 84: P7210. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Montalban X, Sastre-Garriga J, Tintoré M, et al. A single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of interferon beta-1b on primary progressive and transitional multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2009; 15: 1195–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Leary S, Miller D, Stevenson V, et al. Interferon beta-1a in primary progressive MS: An exploratory, randomized, controlled trial. Neurology 2003; 60: 44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kalkers N, Barkhof F, Bergers E, et al. The effect of the neuroprotective agent riluzole on MRI parameters in primary progressive multiple sclerosis: A pilot study. Mult Scler 2002; 8: 532–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Selmaj K, Li DK, Hartung H-P, et al. Siponimod for patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (BOLD): An adaptive, dose-ranging, randomised, phase 2 study. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12: 756–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fazekas F, Sørensen P, Filippi M, et al. MRI results from the European Study on Intravenous Immunoglobulin in Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis (ESIMS). Mult Scler 2005; 11: 433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. ClinicalTrials.gov. Idebenone for primary progressive multiple sclerosis, 2016, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01854359

- 53. Jasperse B, Vrenken H, Sanz-Arigita E, et al. Regional brain atrophy development is related to specific aspects of clinical dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Neuroimage 2007; 38: 529–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Popescu V, Schoonheim MM, Versteeg A, et al. Grey matter atrophy in multiple sclerosis: Clinical interpretation depends on choice of analysis method. PLoS ONE 2016; 11: e0143942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Barkhof F, Calabresi PA, Miller DH, et al. Imaging outcomes for neuroprotection and repair in multiple sclerosis trials. Nat Rev Neurol 2009; 5: 256–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wattjes M, Rovira A, Miller D, et al. Evidence-based guidelines: MAGNIMS consensus guidelines on the use of MRI in multiple sclerosis – Establishing disease prognosis and monitoring patients. Nat Rev Neurol 2015; 11: 597–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. De Stefano N, Giorgio A, Battaglini M, et al. Reduced brain atrophy rates are associated with lower risk of disability progression in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis treated with cladribine tablets. Mult Scler. Epub ahead of print 1 January 2017. DOI: 10.1177/1352458517690269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sormani MP, Arnold DL, De Stefano N. Treatment effect on brain atrophy correlates with treatment effect on disability in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2014; 75: 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lee H, Narayanan S, Brown RA, et al. Brain atrophy after bone marrow transplantation for treatment of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2017; 23: 420–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hauser SL, Bar-Or A, Comi G, et al. Ocrelizumab versus interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 221–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Nakamura K, Brown RA, Araujo D, et al. Correlation between brain volume change and T2 relaxation time induced by dehydration and rehydration: Implications for monitoring atrophy in clinical studies. Neuroimage Clin 2014; 6: 166–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Friese MA, Schattling B, Fugger L. Mechanisms of neurodegeneration and axonal dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol 2014; 10: 225–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bodini B, Louapre C, Stankoff B. Advanced imaging tools to investigate multiple sclerosis pathology. Presse Med 2015; 44: e159–e167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Popescu V, Agosta F, Hulst HE, et al. Brain atrophy and lesion load predict long term disability in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013; 84: 1082–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Enzinger C, Barkhof F, Ciccarelli O, et al. Nonconventional MRI and microstructural cerebral changes in multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol 2015; 11: 676–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Khaleeli Z, Sastre-Garriga J, Ciccarelli O, et al. Magnetisation transfer ratio in the normal appearing white matter predicts progression of disability over 1 year in early primary progressive multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007; 78: 1076–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Mottershead J, Schmierer K, Clemence M, et al. High field MRI correlates of myelin content and axonal density in multiple sclerosis – A post-mortem study of the spinal cord. J Neurol 2003; 11: 1293–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Rovaris M, Gass A, Bammer R, et al. Diffusion MRI in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2005; 65: 1526–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Fox R, McColl R, Lee J, et al. A preliminary validation study of diffusion tensor imaging as a measure of functional brain injury. Arch Neurol 2008; 65: 1179–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Grech-Sollars M, Hales P, Miyazaki K, et al. Multi-centre reproducibility of diffusion MRI parameters for clinical sequences in the brain. NMR Biomed 2015; 28: 468–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Gülin Ö. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy of degenerative brain diseases. Cham: Springer, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Moccia M, Ciccarelli O. Molecular and metabolic imaging in multiple sclerosis. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2017; 27: 343–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. De Stefano N, Filippi M, Miller D, et al. Guidelines for using proton MR spectroscopy in multicenter clinical MS studies. Neurology 2007; 69: 1942–1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Filippi M, Rocca MA, Pagani E, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of oral laquinimod in multiple sclerosis: MRI evidence of an effect on brain tissue damage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014; 85: 852–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Sajja B, Narayana P, Wolinsky J, et al. Longitudinal magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging of primary progressive multiple sclerosis patients treated with glatiramer acetate: Multicenter study. Mult Scler 2008; 14: 73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Brex P, Leary SM, O’Riordan JI, et al. Measurement of spinal cord area in clinically isolated syndromes suggestive of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001; 70: 544–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Gass A, Rocca MA, Agosta F, et al. MRI monitoring of pathological changes in the spinal cord in patients with multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2015; 14: 443–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Losseff N, Webb S, O’Riordan J, et al. Spinal cord atrophy and disability in multiple sclerosis. A new reproducible and sensitive MRI method with potential to monitor disease progression. Brain 1996; 119: 701–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Furby J, Hayton T, Altmann D, et al. A longitudinal study of MRI-detected atrophy in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2010; 257: 1508–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Rashid W, Davies G, Chard D, et al. Upper cervical cord area in early relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: Cross-sectional study of factors influencing cord size. J Magn Reson Imaging 2006; 23: 473–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Rashid W, Davies G, Chard D, et al. Increasing cord atrophy in early relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A 3 year study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006; 77: 51–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Rocca M, Horsfield M, Sala S, et al. A multicenter assessment of cervical cord atrophy among MS clinical phenotypes. Neurology 2011; 76: 2096–2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Brownlee WJ, Altmann DR, Alves Da, Mota P, et al. Association of asymptomatic spinal cord lesions and atrophy with disability 5 years after a clinically isolated syndrome. Mult Scler 2017; 23: 665–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Kearney H, Schneider T, Yiannakas MC, et al. Spinal cord grey matter abnormalities are associated with secondary progression and physical disability in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015; 86: 608–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kearney H, Rocca MA, Valsasina P, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging correlates of physical disability in relapse onset multiple sclerosis of long disease duration. Mult Scler 2014; 20: 72–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Prados F, Yiannakas M, Cardoso MJ, et al. Computing spinal cord atrophy using the Boundary Shift Integral: A more powerful outcome measure for clinical trials? In: ECTRIMS, http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1519778/

- 87. De Paula Faria D, Copray S, Buchpiguel C, et al. PET imaging in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2014; 9: 468–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Matthews PM, Datta G. Positron-emission tomography molecular imaging of glia and myelin in drug discovery for multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2015; 10: 557–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Matthews PM, Comley R. Advances in the molecular imaging of multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2009; 5: 765–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Freeman L, Garcia-Lorenzo D, Bottin L, et al. The neuronal component of gray matter damage in multiple sclerosis: A [(11) C]flumazenil positron emission tomography study. Ann Neurol 2015; 78: 554–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Mallik S, Samson RS, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, et al. Imaging outcomes for trials of remyelination in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014; 85: 1396–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Fisher J, Jacobs D, Markowitz C, et al. Relation of visual function to retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in multiple sclerosis. Ophthalmology 2006; 113: 324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Costello F, Hodge W, Pan Y, et al. Tracking retinal nerve fiber layer loss after optic neuritis: A prospective study using optical coherence tomography. Mult Scler 2008; 14: 893–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Herrero R, Garcia-Martin E, Almarcegui C, et al. Progressive degeneration of the retinal nerve fiber layer in patients with multiple sclerosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012; 53: 8344–8349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Wolinsky JS, Narayana PA, Nelson F, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging outcomes from a phase III trial of teriflunomide. Mult Scler 2013; 19: 1310–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Radue E-W, Sprenger T, Gaetano L, et al. Teriflunomide slows brain volume loss in relapsing MS: A SIENA analysis of the TEMSO MRI dataset. In: ECTRIMS, https://onlinelibrary.ectrims-congress.eu/ectrims/2015/31st/116702/ernst.wilhelm.radue.teriflunomide.slows.brain.volume.loss.in.relapsing.ms.a.html?f=m1

- 97. Kearney H, Yiannakas M, Abdel-Aziz K, et al. Improved MRI quantification of spinal cord atrophy in multiple sclerosis. J Magn Reson Imaging 2014; 39: 617–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Prados F, Cardoso M, Yiannakas M, et al. Fully automated grey and white matter spinal cord segmentation. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 36151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Lukas C, Sombekke M, Bellenberg B, et al. Relevance of spinal cord abnormalities to clinical disability in multiple sclerosis: MR imaging findings in a large cohort of patients. Radiology 2013; 269: 542–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Altmann DR, Jasperse B, Barkhof F, et al. Sample sizes for brain atrophy outcomes in trials for secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2009; 72: 595–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Kadam P, Bhalerao S. Sample size calculation. Int J Ayurveda Res 2010; 1: 55–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Van Den Elskamp IJ, Boden B, Dattola V, et al. Cerebral atrophy as outcome measure in short-term phase 2 clinical trials in multiple sclerosis. Neuroradiology 2010; 52: 875–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Molyneux PD, Miller DH, Filippi M, et al. The use of magnetic resonance imaging in multiple sclerosis treatment trials: Power calculations for annual lesion load measurement. J Neurol 2000; 247: 34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Sormani MP, Bruzzi P, Miller DH, et al. Modelling MRI enhancing lesion counts in multiple sclerosis using a negative binomial model: Implications for clinical trials. J Neurol Sci 1999; 163: 74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Sormani MP, Rovaris M, Bagnato F, et al. Sample size estimations for MRI-monitored trials of MS comparing new vs standard treatments. Neurology 2001; 57: 1883–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Van den Elskamp IJ, Knol DL, Vrenken H, et al. Lesional magnetization transfer ratio: A feasible outcome for remyelinating treatment trials in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2010; 16: 660–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Sormani MP, Calabrese M, Signori A, et al. Modeling the distribution of new MRI cortical lesions in multiple sclerosis longitudinal studies. PLoS ONE 2011; 6: e26712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Sampat MP, Healy BC, Meier DS, et al. Disease modeling in multiple sclerosis: Assessment and quantification of sources of variability in brain parenchymal fraction measurements. Neuroimage 2010; 52: 1367–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Chataway J, Nicholas R, Todd S, et al. A novel adaptive design strategy increases the efficiency of clinical trials in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2011; 17: 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]