Abstract

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a biologically relevant signaling molecule in mammals. Along with the volatile substances nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO), H2S is defined as a gasotransmitter. It plays a physiological role in a variety of functions, including synaptic transmission, vascular tone, angiogenesis, inflammation, and cellular signaling. The generation of H2S is catalyzed by cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MST). The expression of CBS and CSE is tissue specific, with CBS being expressed predominantly in the brain, and CSE in peripheral tissues, including lungs. CSE expression and activity are developmentally regulated, and recent studies suggest that CSE plays an important role in lung alveolarization during fetal development. In the respiratory tract, endogenous H2S has been shown to participate in the regulation of important functions such as airway tone, pulmonary circulation, cell proliferation or apoptosis, fibrosis, oxidative stress, and inflammation. In the past few years, changes in the generation of H2S have been linked to the pathogenesis of a variety of acute and chronic inflammatory lung diseases, including asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Recently, our laboratory made the critical discovery that cellular H2S exerts broad-spectrum antiviral activity both in vitro and in vivo, in addition to independent antiinflammatory activity. These findings have important implications for the development of novel therapeutic strategies for viral respiratory infections, as well as other inflammatory lung diseases, especially in light of recent significant efforts to generate controlled-release H2S donors for clinical therapeutic applications.

Keywords: antiviral, H2S donors, hydrogen sulfide

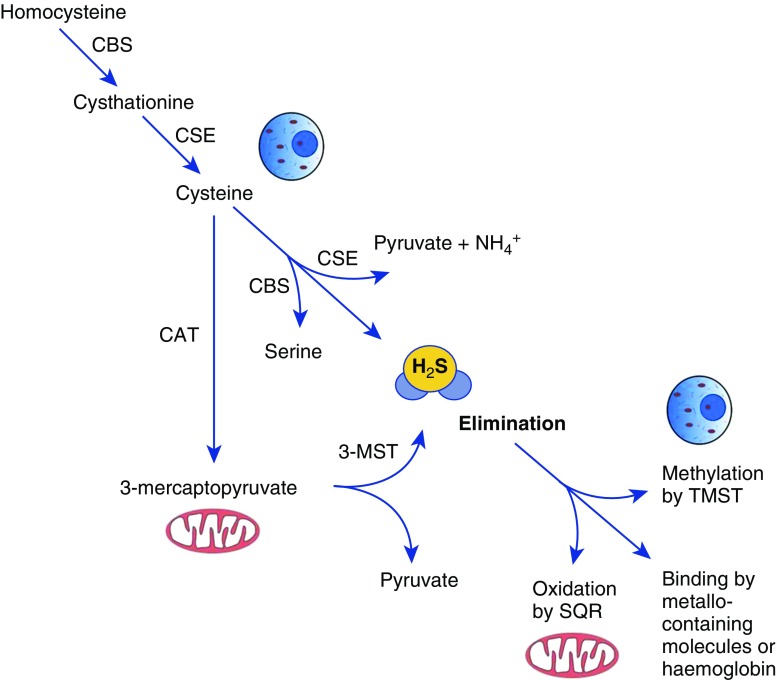

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is colorless gas that is toxic in high concentrations (1) and plays an important role in vital body functions by acting as a gaseous molecular mediator, similarly to nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO) (2). It is synthesized in mammalian cells via two pyridoxal-5′-phosphate–dependent enzymes that are responsible for metabolism of L-cysteine (cystathionine β-synthase [CBS] and cystathionine γ-lyase [CSE]) and a third pathway that involves the combined action of 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MST) and cysteine aminotransferase (CAT) (reviewed in References 3 and 4). Scavenging mechanisms in mammalian cells serve to mitigate the toxic effects of H2S. Free H2S can be oxidized in mitochondria by the enzyme sulfide quinone reductase (5), or methylated in the cytoplasm by thiol-S-methyltransferase (6). Free H2S can also be bound by methemoglobin and by molecules with metal- or disulfide bonds and excreted with biological fluids (7) (Figure 1). Cells in different tissues usually express all enzymes at various levels; however, CSE and CBS are the dominant enzymes responsible for the production of H2S in the cardiovascular system (8, 9) and nervous system (10, 11), respectively. The respiratory system has detectable levels of expression of both CSE and CBS (12). Recently, Madurga and colleagues used laser capture microdissection followed by PCR to show that CBS is predominantly expressed in airway vessels and epithelial cells, whereas CSE is expressed in mouse lung parenchyma (13).

Figure 1.

Intracellular synthesis and degradation of H2S. H2S is produced by cytoplasmic and mitochondrial enzymes (cystathionine γ-lyase [CSE], cystathionine β-synthase [CBS], 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase [3-MST], and cysteine aminotransferase [CAT]) using cysteine or homocysteine as substrates. Intracellular nontoxic H2S levels are actively maintained by oxidation in the mitochondria by the enzyme sulfide quinone reductase (SQR), or methylation in the cytoplasm by thiol-S-methyltransferase (TMST). Free H2S can also be bound by methemoglobin and by molecules with metal- or disulfide bonds and excreted with biological fluids.

Since its discovery as a gasotransmitter, H2S has gained attention as a powerful antiinflammatory, cytoprotective, and vasoactive agent. It has been shown to have antiinflammatory and antioxidant activity, and to modulate ion channel functions and cellular signaling by inhibiting or activating a multitude of signaling pathways (reviewed in References 14 and 15). Although there is no clear consensus on the mechanism of H2S’s action on cellular signaling, H2S has been shown to act as a scavenger for reactive oxygen species, due to its reducing and nucleophilic nature, and to modify proteins by S-sulfhydration, which affects protein function, cellular localization, stability, and resistance to oxidative damage (reviewed in References 16 and 17).

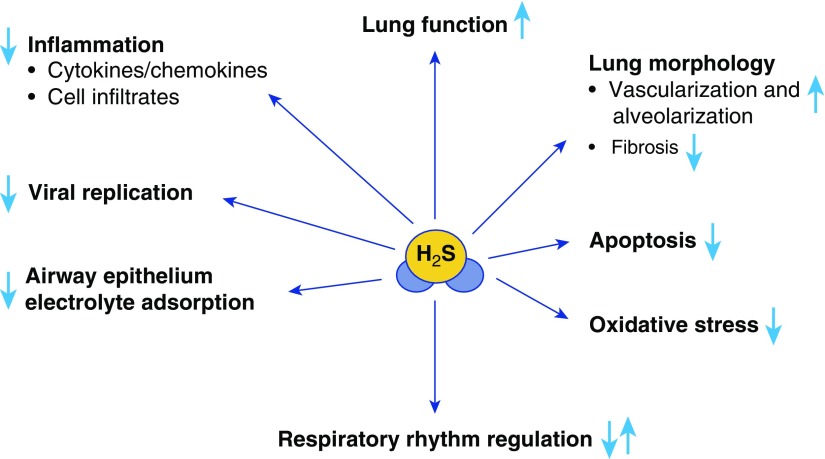

In the respiratory tract, endogenous H2S has been shown to participate in the regulation of important physiological functions such as airway tone, pulmonary circulation, and cell proliferation and apoptosis, and to modulate lung fibrosis, oxidative stress, and inflammation (Figure 2). In the sections below, we describe the role of H2S in physiological and pathological lung conditions, and the potential therapeutic use of H2S donors in various lung diseases.

Figure 2.

Role of H2S in the physiopathology of the airways. Under physiological conditions, H2S participates in regulating respiratory rhythm in the central nervous system and transporting electrolytes, and is necessary for normal development of lung vasculature and alveolarization. In various disease conditions, H2S has been shown to inhibit inflammatory responses, pulmonary fibrosis, and oxidative stress, and to possess broad antiviral activity.

Role of H2S in Lung Physiology and Development

H2S generation has been shown to play a pivotal role in maintaining several respiratory functions. Studies in vitro, using brainstem slices from neonatal rats, showed that H2S is involved in the central control of rhythmic respiration (18, 19). In those studies, the authors found that exogenous H2S could affect respiratory activity in a diphasic mode, with a decrease in the respiratory frequency in the initial stage followed by an increase in the later stage. They also found that endogenous H2S could be produced through the CBS pathway and was involved in controlling the rhythmic respiration of the slices. In addition, they noted that the two opposite modes of the effects of H2S on respiratory activity could be induced by opening ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP) and activating the cyclic adenosine monosphosphate (cAMP) pathway, respectively. Studies in vivo using H2S donors and CBS inhibitors also suggested that H2S likely plays a role in the regulation of respiratory rhythm (20). Different concentrations of sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) and cysteine (Cys), which are H2S donors, were used to explore whether H2S could affect respiratory activity in adult rats. The authors found that low concentrations of NaHS did not significantly affect the rhythmic discharge of the diaphragm, whereas low concentrations of Cys increased it. In addition, moderate concentrations of NaHS and Cys could induce biphasic respiration responses, resulting in changes in rhythm, whereas high concentrations could irreversibly suppress the diaphragmatic discharge.

Exogenous application of H2S has been shown to trigger electrolyte absorption by the respiratory epithelium (reviewed in Reference 21). This effect is achieved via inhibition of Na+/K+-ATPase and KCa channels (22–24), and results in increased mucociliary clearance, which could be beneficial by enhancing the elimination of pathogenic microorganisms (24). Most importantly, H2S has been shown to be involved in lung vascular development and alveolarization (13, 25). Madurga and colleagues found that systemic administration of the H2S slow-releasing donor GYY4137 partially restored arrested alveolarization in an experimental model of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (25). The same group later showed that the H2S-generating enzymes CBS and CSE are also important for normal development of the lung (13). Using pharmacological and functional ablation of expression of these enzymes, they observed a significant decrease in both vascular and alveolar development both in vitro and in vivo (13). In support of a protective role of H2S in the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, CSE expression and activity seem to be developmentally regulated, as demonstrated by studies in human premature infants, newborns, and infants in their first year of life, a period in which this enzyme has been measured and found to be delayed in maturation (26, 27). Lower CSE expression and activity could also play an important pathogenic role in the context of respiratory viral infections that occur in the first year of life, when an intact H2S-generating pathway seems to be an important protective mechanism against disease (see section below).

Role of Endogenous H2S in Airway Diseases

Acute and chronic respiratory diseases constitute a major health burden in both children and adults. It is estimated that chronic respiratory illnesses such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma are the third leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for almost 150,000 deaths in 2015 in the United States alone (28). Similarly, acute viral respiratory illnesses due to paramyxovirus and influenza virus infections are associated with high morbidity and increased mortality in populations at risk, such as infants, the elderly, and immunocompromised patients (29–31). In the past few years, researchers have investigated the role of endogenous H2S in the pathophysiology of several respiratory diseases, including asthma, COPD, rhinitis, cystic fibrosis, and viral infections, as summarized in the paragraphs below.

Asthma

In a rat model of asthma, levels of endogenous H2S were found to be decreased in pulmonary tissue from ovalbumin-treated rats. Serum levels of H2S were correlated positively with H2S levels in lung tissues and peak expiratory flow, and negatively with the proportion of eosinophils and neutrophils in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), inflammatory cell airway infiltration, and goblet cell and airway smooth muscle hyperplasia (32). In a mouse model of asthma, lack of CSE expression resulted in increased airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) after methacholine challenge and increased lung inflammation (33).

Several human studies have shown a decrease in serum and exhaled-breath H2S levels in both adult and pediatric asthmatic populations (34–36). Lower H2S levels were shown to correlate with abnormal pulmonary lung function tests and severity of asthma (34–36). Only one study, performed using sputum samples from adult asthmatic patients, showed the opposite correlation: higher H2S levels were associated with more severe disease (37), possibly due to changes in H2S-producing bacteria in the oral cavity (38). Taken together, these data provide evidence that H2S plays an important protective role in allergic airway disease.

COPD

In a mouse model of tobacco smoke–induced emphysema, 12–24 weeks of smoke exposure was associated with decreased CSE and CBS expression in the lungs (39). In a rat model of chronic smoke exposure, blocking endogenous CSE with propargylglycine (PAG) increased airway reactivity induced by methacholine and significantly aggravated epithelial damage and emphysema, indicating a protective role of endogenous H2S production in the development of the disease (40).

In human studies, serum H2S levels were significantly higher in patients with stable COPD than in patients with acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD), and they were significantly lower in smokers compared with nonsmokers in both the AECOPD patient pool and the healthy control group (41). In patients with stable COPD, serum H2S levels were found to be significantly lower in those with stage III versus stage I obstruction (41). This correlated positively with the percentage of predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) values, and negatively with neutrophils present in induced sputum from patients with acute exacerbation (41). Patients with COPD also displayed lower levels of CSE protein and CBS mRNA (42), and lower levels of exhaled H2S were found in COPD patients with significant eosinophilia and sputum eosinophils, worse lung function, and more frequent exacerbations (43).

Allergic Rhinitis

In a guinea pig model of ovalbumin-induced allergic rhinitis, the levels of serum H2S and CSE mRNA expression in nasal mucosa were significantly reduced and the clinical disease was more severe upon administration of the CSE inhibitor PAG (44, 45). However, two human studies of nasal mucosal samples isolated from patients with allergic rhinitis showed higher levels of H2S, CSE, and CBS mRNA and protein expression (46), and no correlation with either the severity of disease or the presence or absence of polyps (47).

Cystic Fibrosis

An analysis of H2S levels in sputum from patients with cystic fibrosis showed that levels of H2S correlated inversely with the amount of sputum produced (48). Thus, high levels of H2S were associated with lower amounts of sputum and also correlated with a decreased likelihood of inpatient hospitalization and need for supplemental oxygen, suggesting that H2S could be a biomarker of good health in patients with cystic fibrosis (48). However, only 21 patients were included in this study, and thus no clear statistical correlation between H2S and changes in disease progression could be drawn.

Viral Infections

Recent investigations in our laboratory have identified a novel antiviral role for H2S. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection of airway epithelial cells was associated with decreased CSE mRNA and protein expression, a reduced ability to generate intracellular H2S, and increased sulfide quinone reductase expression, leading to increased H2S degradation in virus-infected cells (49). Inhibition of CSE with PAG significantly increased production of cytokines and chemokines in response to RSV infection and was associated with increased viral infectious particle formation (49). These findings were replicated in a mouse model of RSV infection, using mice lacking CSE expression. CSE knockout mice exhibited enhanced clinical disease (assessed by body-weight loss and a validated clinical illness score), increased AHR in response to methacholine challenge (assessed by total body plethysmography), and enhanced viral replication and lung inflammation compared with wild-type mice (50). Together, these data indicate that endogenous H2S plays an important role in controlling viral replication and lung disease in response to RSV infection.

H2S Donors for Treatment of Respiratory Diseases

As noted above, it is becoming increasingly clear that a number of airway diseases are associated with a state of H2S deficiency; therefore, the use of H2S donor molecules may provide a possible therapeutic approach by replenishing and increasing H2S tissue levels. H2S donors include inorganic salts, compounds with organic backbones, amino acids, and naturally occurring compounds (reviewed in Reference 51), as well as H2S-releasing chimeras (H2S-aspirin, H2S-diclofenac, etc.) (reviewed in Reference 52), and some of these are being tested in clinical trials (a list of these trials is available at www.clinicaltrials.gov). In the following section, we discuss the evidence in support of the potential use of H2S donor molecules for therapeutic applications in respiratory diseases (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of H2S Treatment in Animal Models of Lung Diseases

| Disease Model | H2S Donor(s) | Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma (mouse, rat) | NaHS | ↓ Airway hyperresponsiveness | (32) |

| ↓ Inflammation | (33) | ||

| ↓ Oxidative stress | (53) | ||

| ↓ Mast cell degranulation | (54) | ||

| ↓ Fibroblast recruitment and proliferation | |||

| ↓ Pathology | |||

| ↑ Lung function | |||

| COPD (mouse, rat) | NaHS | ↓ Pathology | (39) |

| ↓ Inflammation | (40) | ||

| ↓ Airway hyperresponsiveness | |||

| ↑ Lung function | |||

| ↓ Oxidative stress | |||

| ↓ Apoptosis | |||

| Pulmonary fibrosis (mouse, rat) | NaHS | ↓ Pathology | (56) |

| ↓ Oxidative stress | (57) | ||

| ↓ Inflammation | (58) | ||

| ↓ Fibrosis | |||

| Allergic rhinitis (guinea pig) | NaHS | ↓ Clinical disease | (44) |

| ↓ Inflammation | |||

| Acute lung injury (mouse, rat) | DATS | ↓ Inflammation | (61) |

| GYY4137 | ↓ Oxidative stress | (65) | |

| DTT | ↓ Clinical disease | (73) | |

| RSV infection (mouse) | GYY4137 | ↓ Clinical disease | (50) |

| ↓ Airway hyperresponsiveness | |||

| ↓ Viral replication | |||

| ↓ Inflammation |

Definition of abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DATS, diallyl trisulfide; GYY4137, phosphorodithioate-based donor; DTT, 1,2-dithiole-3-thiones; NaHS, sodium hydrosulfide; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Inorganic Salts

Inorganic salts, such as NaHS, are the H2S donors that are most commonly used to investigate the therapeutic effects of H2S administration in vitro and in vivo, and they have been tested in a variety of respiratory diseases. They are the most cost-effective H2S donors available, but they are also the least controllable, because an immediate release of H2S in solution or biological fluid creates challenges due to potentially toxic effects on the studied system. They have shown a protective effect in numerous in vivo models of lung diseases, as illustrated below. Most studies to date have used concentrations up to 50 μmol/kg of body weight given intraperitoneally, with no reported toxicity.

Exogenous supplementation of H2S using NaHS resulted in improved symptoms in several animal models of asthma (33, 53, 54). In mice with ovalbumin-induced asthma, administration of NaHS 30 minutes before and 8 hours after methacholine challenge was associated with lower AHR, reduced recruitment of inflammatory cells (eosinophils and neutrophils) in BALF, lower levels of Th2 cytokines (including IL-5, IL-13, and eotaxin), and decreased mast cell degranulation and neutrophil recruitment to the lungs (33, 53, 54). A decrease in the glutathione reduced/oxidized (GSH/GSSG) ratio, an indicator of cellular oxidative stress, which occurs in ovalbumin-induced asthma, was also restored by exogenous NaHS treatment (54). Similar results were obtained in a rat model of ovalbumin-induced asthma, which additionally showed a decrease in goblet cell hyperplasia and reduced collagen deposition in NaHS-treated animals (32).

NaHS treatment in a model of ozone exposure, which induces symptoms similar to asthma, was also associated with a better disease outcome. The positive effects of both pre- and postexposure NaHS treatment included decreases in cellular infiltration, proinflammatory cytokine secretion, and AHR in response to methacholine challenge (37). NaHS treatment also restored CSE and CBS mRNA and protein levels, which were significantly reduced in ozone-exposed mice (37).

In rodent models, exogenous H2S administration consistently showed positive effects on several aspects of COPD. In a mouse model of emphysema induced by cigarette smoke, administration of NaHS for 5 days per week for 24 weeks was able to improve lung morphology and reduce inflammatory cell recruitment in BALF (39). NaHS also reduced proinflammatory cytokine levels and decreased bronchial wall thickness caused by cigarette smoke (39). Similarly, in a rat model of cigarette smoke exposure, NaHS treatment decreased cytokine and chemokine secretion and AHR (40). Emphysema caused by ozone was also improved by NaHS treatment. Pretreatment of mice with NaHS prevented the increase in forced residual capacity and decrease in total lung capacity, and prevented a decrease in the ratio of the forced expiratory volume in the first 25 and 50 milliseconds (FEV25 and FEV50, respectively) to the forced vital capacity (FVC) (55). It also decreased lymphocyte, neutrophil, and eosinophil recruitment, as well as bronchial wall remodeling. Postexposure NaHS treatment also provided partial protection against ozone-induced lung injury and emphysema (55).

Administration of NaHS was shown to decrease lung fibrosis and type I collagen deposition in a rat model of pulmonary fibrosis induced by cigarette smoke (56). Additionally, it attenuated the increase in malondialdehyde (a marker of oxidative injury) caused by cigarette smoking, and raised levels of the antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase (56). Smoking raised the levels of the inflammatory mediators C-reactive protein, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, which were also decreased by NaHS administration (56).

In a rat model of bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis, administration of NaHS attenuated the increase in hydroxyproline, a marker of lung collagen deposition, and ameliorated alveolar wall thickening, honeycombing, and collagen deposition. Plasma levels of H2S, which decreased with bleomycin, were also rescued by NaHS treatment (57). In a similar mouse model of bleomycin-induced sclerosis, NaHS treatment reduced the levels of the proinflammatory cytokines ED1, MCP-1, and TGF-β1, as well as lung cellular infiltration and fibrosis, as evidenced by a reduction in collagen deposition, prevention of alveolar collapse, and reduced thickening of alveolar septa (58).

Finally, in a guinea pig model of allergic rhinitis, exogenous administration of NaHS was able to alleviate both the disease symptoms and the underlying inflammatory parameters (44).

Phosphorodithioate-Based Donors

In 2008, Li and colleagues described GYY4137, a Lawesson’s reagent derivative, as a water-soluble H2S donor that showed a slow (in the micromolar range when used at millimolar concentrations) and controllable release of H2S by hydrolysis in a pH-dependent manner (59). Since then, this compound has been widely used and has shown antiinflammatory properties in cultured cells and a variety of animal models of inflammation in vivo (60). GYY4137 has been tested in some models of lung diseases, as illustrated below, with results similar to those obtained with inorganic salts.

A recent study by Zhang and colleagues showed a beneficial effect of GYY4137 treatment in a mouse model of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced acute lung injury (61). Intraperitoneal administration of 50 mg/kg of GYY4137 right before challenge resulted in decreased secretion of LPS-induced proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-8, and increased production of the antiinflammatory cytokine IL-10. GYY4137 treatment was associated with a strong antioxidative effect, as evidenced by reduced levels of H2O2 and malondialdehyde, and restored activity of the antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase and catalase in lung tissues, leading to normalization of the GSH/GSSG ratio (61). Although GYY4137 has not been used in animal models of COPD, GYY4137 treatment showed improvement of COPD-related parameters in an in vitro cell culture model of smoke exposure (42). Alveolar macrophages isolated from rats exposed to cigarette smoke, and U937 cells exposed to cigarette smoke, showed a reduction in proinflammatory mediator secretion upon treatment with the compound (42).

In agreement with the recent finding that endogenous H2S plays an important antiviral and antiinflammatory role in RSV infection, treatment of airway epithelial cells with GYY4137 reduced RSV-induced proinflammatory mediator production and significantly reduced viral replication, even when administered several hours after viral adsorption (49). GYY4137 also significantly reduced replication and inflammatory chemokine production induced by human metapneumovirus and Nipah virus in infected airway epithelial cells, suggesting a broad inhibitory effect of H2S on paramyxovirus infections. GYY4137 treatment had no effect on RSV genome replication or viral mRNA or protein synthesis, but it inhibited syncytia formation and virus assembly/release. GYY4137 inhibition of proinflammatory gene expression occurred by modulation of the activation of the key transcription factors nuclear factor (NF)-кB and interferon regulatory factor (IRF)-3 at a step subsequent to their nuclear translocation (49). Importantly, intranasal delivery of 50 mg/kg of GYY4137 to RSV-infected mice during the first 24 hours after infection significantly reduced viral replication and markedly improved clinical disease parameters and pulmonary dysfunction. Administration of GYY4137 up to 200 mg/kg was not associated with significant toxicity, but did not result in increased benefit. The protective effect of GYY4137 was associated with a significant reduction of viral-induced proinflammatory mediators and lung cellular infiltrates in vivo (50).

In addition to paramyxoviruses, GYY4137 showed a similar antiviral effect in an in vitro model of infection with other highly pathogenic RNA viruses, including influenza A and B, Ebola virus, Far-Eastern subtype tick-borne flavivirus, Rift Valley fever virus, and Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (62). Administration of GYY4137 up to 6 hours after infection dramatically reduced virus replication and production of proinflammatory cytokines, likely due to inhibition of the NF-κB and IRF-3 signaling pathways, similar to what was observed in the case of RSV infection. In contrast to the results for paramyxovirus infection, GYY4173 treatment was associated with decreased influenza A RNA and protein expression (62).

Thiol-Activated H2S Donors

Thiol-activated H2S donors that release H2S in the presence of thiols, such as Cys and GSH, were recently synthesized. This group includes N-mercapto–based donors, S-arylthiooximes, perthiol-based donors, dithioperoxyanhydrides, thioamide- and aryl isothiocyanate–based donors, and gem-dithiol–based donors (reviewed in Reference 51). Preliminary data suggest that a member of the gem-dithiol–based donor family, called TAGDD-1, showed antiviral activity similar to that of GYY4137 when tested in an in vitro model of RSV and influenza virus infection (A.C. and colleagues, unpublished data).

Natural Sulfur-Containing Compounds

Garlic has been shown to contain several sulfur-containing compounds, the most abundant of which is allicin (63). Once extracted from garlic, allicin quickly decomposes into derivatives such as diallyl sulfide (DAS), diallyl disulfide (DADS), and diallyl trisulfide (DATS) (64). Similarly to thiol-activated donors, garlic-derived compounds are believed to release H2S only in the presence of thiols such as GSH. DATS is one of the most studied compounds in various models of inflammatory diseases, both in vitro and in vivo. In relation to respiratory diseases, DATS administration has been shown to have a beneficial effect in naphthalene-induced lung injury (65). DATS treatment was associated with elevation of GSH levels in lung tissue, inhibition of the production of serum TNF-α and IL-8, and suppression of lung inflammatory cell recruitment, in particular neutrophil infiltration (65).

Very limited data are available regarding the possible antiviral activity of DATS. Fang and colleagues showed the anti-cytomegalovirus (CMV) activity of allitridin (DATS) in vivo using clinical isolates of human and mouse CMV strains (66). Studies from the same group showed the beneficial effect of allitridin on liver pathology after CMV infection and reduction of viral load in affected organs (67, 68). The effect of allitridin was attributed to the inhibition of viral gene transcription (69, 70) and to decreased immune tolerance to the infection by reducing amplification of T-regulatory helper cells after CMV infection (71, 72).

Anethole Dithiolethione

Anethole dithiolethione (ADT) and its main metabolite, ADT-OH; 5-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-3H-1,2-dithiole-3-thione, have been used extensively as donors of H2S, and their ease of esterification with other therapeutics has led to a considerable variety of “H2S-donating” drugs, including nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs such as H2S-aspirin and H2S-diclofenac (reviewed in Reference 52). These novel combinatory drugs have been shown to have similar or higher antiinflammatory effects and fewer adverse effects compared with their nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug counterparts. Administration of S-diclofenac (an ADT-diclofenac chimera) in a rat model of LPS-induced septic shock was shown to be more effective in reducing lung myeloperoxidase activity (a sign of lung inflammation) compared with diclofenac alone (73).

Conclusions

H2S is emerging as an important potential therapeutic option for acute and chronic respiratory inflammatory diseases. Significant progress has been made in studying the underlying mechanisms of H2S cellular generation and the potential role of H2S in models of lung diseases in vivo. Future research should focus on continuing to elucidate the basic biology of H2S in the respiratory system and its relationship with the pathophysiology of lung diseases. As it has been shown that the methods commonly used to measure H2S in biological samples are associated with substantial artifacts (74), it is critical to gain a better understanding of the chemistry involved and the problems of the analytical techniques used to measure H2S concentrations. From a therapeutic standpoint, there is a need for further development of safe H2S donors with controllable release and better water solubility, as well as efficient methods for delivering these donors to patients.

Footnotes

This work was partially supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI122142, AI25434, AI062885, and ES026782. N.B. was supported by a UTMB McLaughlin fellowship. M.A. was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award NRSA (TL1) Training Core (TL1TR001440), National Institutes of Health.

Author Contributions: N.B. and M.A.: literature review, drafting of the manuscript; T.I.: manuscript review and critical revisions; R.P.G.: manuscript conception, review, and critical revisions; A.C.: manuscript conception, review, critical revisions, and final approval.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0114TR on May 8, 2017

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Lindenmann J, Matzi V, Neuboeck N, Ratzenhofer-Komenda B, Maier A, Smolle-Juettner FM. Severe hydrogen sulphide poisoning treated with 4-dimethylaminophenol and hyperbaric oxygen. Diving Hyperb Med. 2010;40:213–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Łowicka E, Bełtowski J. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S)—the third gas of interest for pharmacologists. Pharmacol Rep. 2007;59:4–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szabó C. Hydrogen sulphide and its therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:917–935. doi: 10.1038/nrd2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kimura H. Production and physiological effects of hydrogen sulfide. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:783–793. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouillaud F, Blachier F. Mitochondria and sulfide: a very old story of poisoning, feeding, and signaling? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:379–391. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levitt MD, Abdel-Rehim MS, Furne J. Free and acid-labile hydrogen sulfide concentrations in mouse tissues: anomalously high free hydrogen sulfide in aortic tissue. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:373–378. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang G, Cao K, Wu L, Wang R. Cystathionine gamma-lyase overexpression inhibits cell proliferation via a H2S-dependent modulation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation and p21Cip/WAK-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49199–49205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408997200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hosoki R, Matsuki N, Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous smooth muscle relaxant in synergy with nitric oxide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;237:527–531. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao W, Zhang J, Lu Y, Wang R. The vasorelaxant effect of H(2)S as a novel endogenous gaseous K(ATP) channel opener. EMBO J. 2001;20:6008–6016. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abe K, Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous neuromodulator. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1066–1071. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01066.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robert K, Vialard F, Thiery E, Toyama K, Sinet PM, Janel N, London J. Expression of the cystathionine β synthase (CBS) gene during mouse development and immunolocalization in adult brain. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51:363–371. doi: 10.1177/002215540305100311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olson KR, Whitfield NL, Bearden SE, St Leger J, Nilson E, Gao Y, Madden JA. Hypoxic pulmonary vasodilation: a paradigm shift with a hydrogen sulfide mechanism. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R51–R60. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00576.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madurga A, Golec A, Pozarska A, Ishii I, Mižíková I, Nardiello C, Vadász I, Herold S, Mayer K, Reichenberger F, et al. The H2S-generating enzymes cystathionine β-synthase and cystathionine γ-lyase play a role in vascular development during normal lung alveolarization. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;309:L710–L724. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00134.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallace JL, Wang R. Hydrogen sulfide-based therapeutics: exploiting a unique but ubiquitous gasotransmitter. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14:329–345. doi: 10.1038/nrd4433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimura H. Physiological roles of hydrogen sulfide and polysulfides. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2015;230:61–81. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-18144-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paul BD, Snyder SH. H2S signalling through protein sulfhydration and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:499–507. doi: 10.1038/nrm3391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Filipovic MR. Persulfidation (S-sulfhydration) and H2S. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2015;230:29–59. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-18144-8_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu H, Shi Y, Chen Q, Yang W, Zhou H, Chen L, Tang Y, Zheng Y. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide is involved in regulation of respiration in medullary slice of neonatal rats. Neuroscience. 2008;156:1074–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan JG, Hu HY, Zhang J, Zhou H, Chen L, Tang YH, Zheng Y. Protective effect of hydrogen sulfide on hypoxic respiratory suppression in medullary slice of neonatal rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010;171:181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li H, Hou X, Ding Y, Nie L, Zhou H, Nie Z, Tang Y, Chen L, Zheng Y. Effects of H2S on the central regulation of respiration in adult rats. Neuroreport. 2014;25:358–366. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pouokam E, Althaus M. Epithelial electrolyte transport physiology and the gasotransmitter hydrogen sulfide. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:4723416. doi: 10.1155/2016/4723416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Althaus M, Urness KD, Clauss WG, Baines DL, Fronius M. The gasotransmitter hydrogen sulphide decreases Na+ transport across pulmonary epithelial cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166:1946–1963. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01909.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erb A, Althaus M. Actions of hydrogen sulfide on sodium transport processes across native distal lung epithelia (Xenopus laevis) PLoS One. 2014;9:e100971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agné AM, Baldin JP, Benjamin AR, Orogo-Wenn MC, Wichmann L, Olson KR, Walters DV, Althaus M. Hydrogen sulfide decreases β-adrenergic agonist-stimulated lung liquid clearance by inhibiting ENaC-mediated transepithelial sodium absorption. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2015;308:R636–R649. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00489.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madurga A, Mižíková I, Ruiz-Camp J, Vadász I, Herold S, Mayer K, Fehrenbach H, Seeger W, Morty RE. Systemic hydrogen sulfide administration partially restores normal alveolarization in an experimental animal model of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;306:L684–L697. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00361.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viña J, Vento M, García-Sala F, Puertes IR, Gascó E, Sastre J, Asensi M, Pallardó FV. L-cysteine and glutathione metabolism are impaired in premature infants due to cystathionase deficiency. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61:1067–1069. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/61.4.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zlotkin SH, Anderson GH. The development of cystathionase activity during the first year of life. Pediatr Res. 1982;16:65–68. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198201001-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2015: with special feature on racial and ethnic health disparities. Report No. 2016-1232. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics (US); 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall CB, Weinberg GA, Iwane MK, Blumkin AK, Edwards KM, Staat MA, Auinger P, Griffin MR, Poehling KA, Erdman D, et al. The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:588–598. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crowe JE., Jr Human metapneumovirus as a major cause of human respiratory tract disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23(11) Suppl:S215–S221. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000144668.81573.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molinari NA, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Messonnier ML, Thompson WW, Wortley PM, Weintraub E, Bridges CB. The annual impact of seasonal influenza in the US: measuring disease burden and costs. Vaccine. 2007;25:5086–5096. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen YH, Wu R, Geng B, Qi YF, Wang PP, Yao WZ, Tang CS. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide reduces airway inflammation and remodeling in a rat model of asthma. Cytokine. 2009;45:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang G, Wang P, Yang G, Cao Q, Wang R. The inhibitory role of hydrogen sulfide in airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation in a mouse model of asthma. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:1188–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J, Wang X, Chen Y, Yao W. Correlation between levels of exhaled hydrogen sulfide and airway inflammatory phenotype in patients with chronic persistent asthma. Respirology. 2014;19:1165–1169. doi: 10.1111/resp.12372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tian M, Wang Y, Lu YQ, Yan M, Jiang YH, Zhao DY. Correlation between serum H2S and pulmonary function in children with bronchial asthma. Mol Med Rep. 2012;6:335–338. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu R, Yao WZ, Chen YH, Geng B, Lu M, Tang CS. [The regulatory effect of endogenous hydrogen sulfide on acute asthma] Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2007;30:522–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saito J, Zhang Q, Hui C, Macedo P, Gibeon D, Menzies-Gow A, Bhavsar PK, Chung KF. Sputum hydrogen sulfide as a novel biomarker of obstructive neutrophilic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:232–4.e1, 3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Basic A, Dahlén G. Hydrogen sulfide production from subgingival plaque samples. Anaerobe. 2015;35:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han W, Dong Z, Dimitropoulou C, Su Y. Hydrogen sulfide ameliorates tobacco smoke-induced oxidative stress and emphysema in mice. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:2121–2134. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen YH, Wang PP, Wang XM, He YJ, Yao WZ, Qi YF, Tang CS. Involvement of endogenous hydrogen sulfide in cigarette smoke-induced changes in airway responsiveness and inflammation of rat lung. Cytokine. 2011;53:334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen YH, Yao WZ, Geng B, Ding YL, Lu M, Zhao MW, Tang CS. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide in patients with COPD. Chest. 2005;128:3205–3211. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.5.3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun Y, Wang K, Li MX, He W, Chang JR, Liao CC, Lin F, Qi YF, Wang R, Chen YH. Metabolic changes of H2S in smokers and patients of COPD which might involve in inflammation, oxidative stress and steroid sensitivity. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14971. doi: 10.1038/srep14971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang J, Wang X, Chen Y, Yao W. Exhaled hydrogen sulfide predicts airway inflammation phenotype in COPD. Respir Care. 2015;60:251–258. doi: 10.4187/respcare.03519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shaoqing Y, Ruxin Z, Yinjian C, Jianqiu C, Zhiqiang Y, Genhong L. Down-regulation of endogenous hydrogen sulphide pathway in nasal mucosa of allergic rhinitis in guinea pigs. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2009;37:180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu S, Yan Z, Che N, Zhang X, Ge R. Impact of carbon monoxide/heme oxygenase on hydrogen sulfide/cystathionine-γ-lyase pathway in the pathogenesis of allergic rhinitis in guinea pigs. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152:470–476. doi: 10.1177/0194599814567112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park SJ, Kim TH, Lee SH, Ryu HY, Hong KH, Jung JY, Hwang GH, Lee SH. Expression levels of endogenous hydrogen sulfide are altered in patients with allergic rhinitis. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:557–563. doi: 10.1002/lary.23466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hwang JW, Jun YJ, Park SJ, Kim TH, Lee KJ, Hwang SM, Lee SH, Lee HM, Lee SH. Endogenous production of hydrogen sulfide in human sinus mucosa and its expression levels are altered in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with and without nasal polyps. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2014;28:12–19. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2014.28.3972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cowley ES, Kopf SH, LaRiviere A, Ziebis W, Newman DK. Pediatric cystic fibrosis sputum can be chemically dynamic, anoxic, and extremely reduced due to hydrogen sulfide formation. MBio. 2015;6:e00767. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00767-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li H, Ma Y, Escaffre O, Ivanciuc T, Komaravelli N, Kelley JP, Coletta C, Szabo C, Rockx B, Garofalo RP, et al. Role of hydrogen sulfide in paramyxovirus infections. J Virol. 2015;89:5557–5568. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00264-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ivanciuc T, Sbrana E, Ansar M, Bazhanov N, Szabo C, Casola A, Garofalo RP. Hydrogen sulfide is an antiviral and antiinflammatory endogenous gasotransmitter in the airways. Role in respiratory syncytial virus infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;55:684–696. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0385OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao Y, Pacheco A, Xian M. Medicinal chemistry: insights into the development of novel H2S donors. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2015;230:365–388. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-18144-8_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kashfi K, Olson KR. Biology and therapeutic potential of hydrogen sulfide and hydrogen sulfide-releasing chimeras. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85:689–703. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roviezzo F, Bertolino A, Sorrentino R, Terlizzi M, Matteis M, Calderone V, Mattera V, Martelli A, Spaziano G, Pinto A, et al. Hydrogen sulfide inhalation ameliorates allergen induced airway hypereactivity by modulating mast cell activation. Pharmacol Res. 2015;100:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Campos D, Ravagnani FG, Gurgueira SA, Vercesi AE, Teixeira SA, Costa SK, Muscará MN, Ferreira HH. Increased glutathione levels contribute to the beneficial effects of hydrogen sulfide and inducible nitric oxide inhibition in allergic lung inflammation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;39:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li F, Zhang P, Zhang M, Liang L, Sun X, Li M, Tang Y, Bao A, Gong J, Zhang J, et al. Hydrogen sulfide prevents and partially reverses ozone-induced features of lung inflammation and emphysema in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;55:72–81. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0014OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou X, An G, Chen J. Inhibitory effects of hydrogen sulphide on pulmonary fibrosis in smoking rats via attenuation of oxidative stress and inflammation. J Cell Mol Med. 2014;18:1098–1103. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fang L, Li H, Tang C, Geng B, Qi Y, Liu X. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis induced by bleomycin in rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;87:531–538. doi: 10.1139/y09-039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang Z, Yin X, Gao L, Feng S, Song K, Li L, Lu Y, Shen H. The protective effect of hydrogen sulfide on systemic sclerosis associated skin and lung fibrosis in mice model. Springerplus. 2016;5:1084. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2774-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li L, Whiteman M, Guan YY, Neo KL, Cheng Y, Lee SW, Zhao Y, Baskar R, Tan CH, Moore PK. Characterization of a novel, water-soluble hydrogen sulfide-releasing molecule (GYY4137): new insights into the biology of hydrogen sulfide. Circulation. 2008;117:2351–2360. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.753467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rose P, Dymock BW, Moore PK. GYY4137, a novel water-soluble, H2S-releasing molecule. Methods Enzymol. 2015;554:143–167. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang HX, Liu SJ, Tang XL, Duan GL, Ni X, Zhu XY, Liu YJ, Wang CN. H2S attenuates LPS-induced acute lung injury by reducing oxidative/nitrative stress and inflammation. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;40:1603–1612. doi: 10.1159/000453210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bazhanov N, Escaffre O, Freiberg AN, Garofalo RP, Casola A. Broad-range antiviral activity of hydrogen sulfide against highly pathogenic RNA viruses. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41029. doi: 10.1038/srep41029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Borlinghaus J, Albrecht F, Gruhlke MC, Nwachukwu ID, Slusarenko AJ. Allicin: chemistry and biological properties. Molecules. 2014;19:12591–12618. doi: 10.3390/molecules190812591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yagdi E, Cerella C, Dicato M, Diederich M. Garlic-derived natural polysulfanes as hydrogen sulfide donors: friend or foe? Food Chem Toxicol. 2016;95:219–233. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2016.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang F, Zhang Y, Wang K, Liu G, Yang M, Zhao Z, Li S, Cai J, Cao J. Protective effect of diallyl trisulfide against naphthalene-induced oxidative stress and inflammatory damage in mice. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2016;29:205–216. doi: 10.1177/0394632015627160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fang F, Li H, Cui W, Dong Y. Treatment of hepatitis caused by cytomegalovirus with allitridin injection—an experimental study. J Tongji Med Univ. 1999;19:271–274. doi: 10.1007/BF02886960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu XL, Wang H, Li YN, Ge HX, Shu SN, Fang F. Effects of allitridin on acute and chronic mouse cytomegalovirus infection. Arch Virol. 2011;156:1841–1846. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu ZF, Fang F, Dong YS, Li G, Zhen H. Experimental study on the prevention and treatment of murine cytomegalovirus hepatitis by using allitridin. Antiviral Res. 2004;61:125–128. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(03)00087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang J, Wang H, Xiang ZD, Shu SN, Fang F. Allitridin inhibits human cytomegalovirus replication in vitro. Mol Med Rep. 2013;7:1343–1349. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhen H, Fang F, Ye DY, Shu SN, Zhou YF, Dong YS, Nie XC, Li G. Experimental study on the action of allitridin against human cytomegalovirus in vitro: Inhibitory effects on immediate-early genes. Antiviral Res. 2006;72:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li YN, Huang F, Liu XL, Shu SN, Huang YJ, Cheng HJ, Fang F. Allium sativum-derived allitridin inhibits Treg amplification in cytomegalovirus infection. J Med Virol. 2013;85:493–500. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yi X, Feng F, Xiang Z, Ge L. The effects of allitridin on the expression of transcription factors T-bet and GATA-3 in mice infected by murine cytomegalovirus. J Med Food. 2005;8:332–336. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2005.8.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li L, Rossoni G, Sparatore A, Lee LC, Del Soldato P, Moore PK. Anti-inflammatory and gastrointestinal effects of a novel diclofenac derivative. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:706–719. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Olson KR, DeLeon ER, Liu F. Controversies and conundrums in hydrogen sulfide biology. Nitric Oxide. 2014;41:11–26. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]