Abstract

Guided by research on psychological safety, we used longitudinal survey data from a sample of 182 dual-earner male-female couples to examine the role of supportive coparenting in mediating relations between adult attachment orientations and parenting stress/satisfaction, and further considered whether parenting self-efficacy moderated relations between supportive coparenting and parenting stress/satisfaction. Path analyses using IBM SPSS AMOS 22 and bootstrapping techniques indicated that fathers’ (but not mothers’) perceptions of supportive coparenting at 3 months postpartum mediated the associations between their attachment anxiety in the third trimester of pregnancy and their parenting stress and satisfaction at 9 months postpartum. Additional tests of moderation revealed that mothers’ perceptions of greater supportive coparenting were associated with lower parenting stress only when their parenting self-efficacy was low, but fathers’ perceptions of greater supportive coparenting were associated with greater parenting satisfaction only when their parenting self-efficacy was high. Implications and limitations are discussed.

The transition to parenthood is an important phase in adult development when existing relationships are transformed and new relationships forged (Antonucci & Mikus, 1988; Belsky & Rovine, 1984). As such, how well new parents navigate this transition has important implications for the well-being of the entire family system. One relationship that emerges across the transition to parenthood is the coparenting relationship between adults that share responsibility for rearing the child (Schoppe-Sullivan, Mangelsdorf, Frosch, & McHale, 2004). Theory and research has consistently identified the quality of coparenting as an important factor in each parent’s adult development, the quality of new parents’ parenting (Feinberg, Jones, Kan, & Goslin, 2010), the child’s socioemotional development (Teubert & Pinquart, 2010), and the continuing evolution of the marital or couple relationship (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2004).

This paper introduces the coparenting relationship as a critical context in which new parents – particularly fathers – may experience psychological safety as they navigate the transition to parenthood. Taking a Relational Developmental Systems Perspective (Lerner, 2015), we view the coparenting relationship as a context within which both parents undergo a major transition in adult development. Coparenting occurs within multilevel systems that also have implications for the exchanges and meanings that are derived for each adult. Each parent may have considerable agency within the coparenting relationship, but ultimately behaviors and actions are the result of co-construction between the individual and context. Our study zooms in on this salient context for adult development and examines ways that the interactions that adults have in coparenting collaboratively generate meaning and have implications for the future.

In particular, our goal was to examine how individual and contextual features operate together via co-action (Lerner, 2015) to make the transition to parenthood a psychologically safe time that facilitates adaptation and adult development. We used longitudinal survey data from a sample of 182 dual-earner male female couples to test supportive coparenting as a mediator of relations between expectant parents’ attachment orientations and their adjustment to parenthood, and further considered whether supportive coparenting would be most closely related to the adjustment of new parents with less confidence in their parenting abilities.

Supportive Coparenting and Psychological Safety

According to holism, the whole is distinct from the sum of its parts (Overton, 2015). The study of coparenting, or the ways in which parents relate to each other in their roles as parents (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2004), reflects an attempt to understand the family system at a more holistic level. Coparenting relationships are distinguished from couple relationships between adults in the family by virtue of their inclusion of the child, which makes these relationships inherently triadic. The quality of a coparenting relationship is chiefly characterized by the extent to which parents support versus undermine each other’s parenting and relationship with the child (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2004). Greater supportive coparenting has been consistently linked to parents’ development as providers of higher-quality parenting and their ongoing parent-child relationships (e.g., Brown, Schoppe-Sullivan, Mangelsdorf, & Neff, 2010), especially for fathers and their children. Supportive coparenting involves acknowledging and appreciating one’s partner’s contributions to parenting, providing emotional support, and engaging in effective communication about parenting strategies and decisions (Feinberg, Brown, & Kan, 2012).

Although the workplace and family are different contexts for human development, they share similarities in the interpersonal risks involved in beginning a new role, such as becoming a parent (Wanless, this issue). According to Edmondson and Lei (2014), psychological safety in the workplace reflects employees’ perceptions of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks, such as sharing new ideas or admitting that they do not know how to do something. If employees experience psychological safety, they feel comfortable that taking these kinds of risks will not result in shame, embarrassment, or ridicule, and therefore feel a reduced need for self-protection and are more able to focus on achieving collective goals. Thus, a work environment characterized by psychological safety supports individuals’ contributions to a shared enterprise, and enables personal engagement, which further enhances learning and performance.

Similarly, individuals who perceive psychological safety in their families may experience successful adaptation at challenging major life transitions such as the transition to parenthood (Wanless, this issue). At this transition, parents must assume new roles and develop new identities (Belsky & Rovine, 1984). Successful adaptation requires willingness to take interpersonal risks and the ability to sustain engagement in the face of uncertainty (Wanless, this issue). In the current U.S. sociopolitical context, this transition may be particularly stressful. The parent role is highly valued, and the standards for “good parenting” are lofty (Roxburgh, 2012). But, even as the number of dual-earner families has increased (Kotila, Schoppe-Sullivan, & Kamp Dush, 2013), there have been few concomitant improvements in social policies to support working parents. Thus, new parents may perceive even the routine activities of parenting as “high-stakes” moments in which they fear harsh judgment by others, including their partners.

Fathers, in particular, may be sensitive to the extent to which mothers support their parenting (Schoppe-Sullivan, Brown, Cannon, Mangelsdorf, & Sokolowski, 2008). Expectations for fathers to be actively involved in raising their young children are higher than ever before (Gerson, 2009). Although fathers’ involvement in childrearing has increased, even mothers in dual-earner families remain more likely to assume the role of primary caregiver for children, and mothers are still viewed by many as the natural parenting “experts” with fathers assuming a helpful, but secondary, role (Kotila et al., 2013). This state of affairs may lead new fathers to experience particular vulnerability as they are developing identities as parents. If new fathers do not feel like they can offer ideas and opinions about parenting without experiencing shame or feeling ridiculed by their partners, they may experience poor adjustment to their parental role. However, if fathers perceive that mothers support their parenting, they may experience psychological safety in the context of the coparenting relationship that facilitates their adjustment to parenthood. Consistent with these notions, previous research indicates that supportive coparenting relationships are associated with fathers’ greater engagement in parenting, higher-quality father-child relationships, and lower parenting stress (Brown et al., 2010; Fagan & Lee, 2014; Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2008). In other words, supportive coparenting relationships seem to enable fathers to be active agents in their development as parents.

Adult attachment, coparenting, and adjustment to parenthood

Whether in the workplace or family, individuals bring with them characteristics that guide their perceptions of the degree of interpersonal risk present in a particular situation and how much psychological safety is needed (Wanless, this issue). A substantial body of literature in the attachment theory tradition has informed us that individuals’ early relationship experiences are carried forward in the form of internal working models that are connected to the development and course of relationships throughout the lifespan (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2012). These working models contain expectations regarding whether other people are likely to provide support when needed and whether one is worthy of receiving such support (Bowlby, 1973). Attachment research in the social psychology tradition has identified anxiety (fear of rejection and/or abandonment) and avoidance (discomfort with closeness and depending on others) as two important dimensions of adults’ working models of attachment (Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998).

Adults’ attachment anxiety and avoidance appear to color their perceptions and behavior in a variety of relational contexts (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2012), and take on particular significance at the transition to parenthood. Several empirical studies have shown that adult attachment orientations are related to new parents’ psychological adjustment to their parental roles (e.g., Alexander, Feeney, Hohaus, & Noller, 2001; Feeney, 2003; Simpson, Rholes, Campbell, Tran, & Wilson, 2003). Alexander et al. (2001) reported that new fathers with greater relationship anxiety perceived parenthood as more stressful than other fathers. And, in Rholes, Simpson, Blakely, Lanigan, and Allen’s intriguing research (1997) that examined adult attachment styles and feelings about future parenthood among college students, more avoidant individuals expect to be easily aggravated by children and to experience less satisfaction from the parenting role and report less desire to become parents.

Although few studies have examined associations between parents’ self-reported anxiety and avoidance and the quality of their coparenting relationships, Simpson et al. (2003) demonstrated that more anxious expectant mothers were more likely to show sharp declines in perceiving spousal support particularly across the prenatal to postnatal period. And, in Feeney’s study (2003), insecure parents were more likely to be dissatisfied with their partner's contributions to the division of child care labor. Moreover, two studies that have examined associations between adult attachment orientations and broader indices of family functioning have demonstrated that adults with greater anxiety and avoidance are more likely to have families characterized by lower cohesion and adaptability and higher triangulation and conflict (Mikulincer & Florian, 1999; Pedro, Ribeiro, & Shelton, 2015).

The role of parenting self-efficacy

In the organizational research literature, employees’ confidence in their knowledge has been identified as an important moderator of the association between their perceived psychological safety in the workplace and their willingness to share knowledge with others (Siemsen, Roth, Balasubramanian, & Anand, 2009). In particular, Siemsen and colleagues (2009) reported that psychological safety was only associated with employees’ knowledge-sharing when employees were less confident in their knowledge. In contrast, when employees had high confidence in their knowledge, they were more willing to share it regardless of perceived psychological safety. The “parenting equivalent” of employees’ confidence is parenting self-efficacy. Parents high in self-efficacy believe that they can parent competently and effectively (Teti & Gelfand, 1991). Just as highly confident employees may demonstrate high engagement and performance at work whether or not their environment is one that they perceive to be psychologically safe, highly confident parents may experience positive adjustment to parenthood regardless of the supportiveness of their partner’s coparenting. In other words, consistent with the notion of adaptive developmental regulations (Lerner, 2015), it is the fit between the individual and context that is critical for developmental outcomes.

The Present Study

In this investigation, we examined the role of supportive coparenting as a source of psychological safety for new parents by using longitudinal survey data from dual-earner couples who were followed across their transition to parenthood from the third trimester of pregnancy through 9 months postpartum. We focused on parenting stress (Kazdin & Whitley, 2003) and satisfaction (Pistrang, 1984) as important and well-established indicators of new parents’ adjustment to parenthood. In particular, we tested whether supportive coparenting at 3 months postpartum mediated relations between expectant parents’ attachment anxiety and avoidance and their parenting stress and satisfaction at 9 months postpartum. In these mediation analyses, we controlled for expectant parents’ perceptions of the couple relationship, which are known to be associated with attachment orientations, coparenting relationship quality, and parental adjustment (Fagan & Lee, 2014; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2012; Van Egeren, 2004).

We anticipated that new parents’ perceptions of the support they received in coparenting would mediate, or link, their attachment orientations and adjustment to parenthood, with this connection especially prominent for fathers, whose experiences of parenting may be sensitive to the psychological safety via supportive coparenting provided by mothers (e.g., Brown et al., 2010; Fagan & Lee, 2014). We recognize that this is only one way in which individual and contextual features may operate together via co-action (Lerner, 2015) to make the transition to parenthood a psychologically safe time that facilitates adaptation and adult development. Thus, we considered these pathways in the context of the larger developing family system.

To further consider the fit between individual and context, we tested whether mothers’ and fathers’ parenting self-efficacy moderated the associations between their perceptions of supportive coparenting and their parenting stress and satisfaction. Consistent with psychological safety research (Siemsen et al., 2009), we expected supportive coparenting to be most relevant to new parents’ adjustment to parenthood when they had lower levels of parenting self-efficacy.

Method

Participants and Procedure

A longitudinal study of couples that were transitioning to parenthood provided a basis for this analysis. Recruitment occurred during pregnancy and took place between 2008 and 2009 in a large city in the Midwestern U. S. Recruitment occurred via childbirth education classes, newspaper advertisements, and flyers at local businesses and doctors’ offices. The study required that couples be English-speaking, 18 years or older, and married or cohabiting. In addition, couples were required to be expecting their first biological child. Lastly, both partners had to be employed full-time with both anticipating a return to work after the birth of their child.

Recruitment resulted in 182 expectant couples. Expectant fathers were 30 years old (M = 30.20; SD = 4.81) and expectant mothers were 28 years old (M = 28.24; SD = 4.02). The median family income of $79,500. A bachelor’s degree was earned by 75% of expectant mothers and 65% of expectant fathers. The majority of participants identified as White (85% of mothers and 86% of fathers). The remaining participants identified as Black (6% of mothers and 7% of fathers), Asian (3% of all parents), and other races and/or multiracial (6% of mothers and 5% of fathers). In addition, some participants identified as Hispanic (4% of mothers and 2% of fathers).

Participating couples were assessed via interview, observation, and questionnaires in the third trimester of pregnancy and at 3, 6, and 9 months postpartum. For this study, we focused on survey data collected from both partners in the third trimester of pregnancy and at 3 and 9 months postpartum. For data used in this study, the amount missing in the third trimester was negligible (2% for expectant mothers and 4% for expectant fathers). At 3 months postpartum, 5% of mothers and 9% of fathers did not provide data, and at 9 months postpartum missing data increased to 16% for mothers and 18% for fathers. T-tests and chi-square analyses considered potential differences in key variables and demographic characteristics for couples who contributed data at 3 and 9 months postpartum versus those who did not. Couples who did not contribute data at 3 months were characterized by lower levels of maternal dyadic adjustment, t(178) = −2.24, p < .05, although they did not differ on attachment anxiety or avoidance or paternal dyadic adjustment. Regarding demographics, couples who did not contribute data at 3 months were more likely to have mothers who had not completed a bachelor’s degree, χ2(1) = 6.42, p < .05, and more likely to have non-white mothers, χ2(1) = 15.05, p < .001, and fathers, χ2(1) = 8.56, p < .01. There were no statistically significant differences in key or demographic variables between couples who contributed data at 9 months and those who did not.

Measures: Third Trimester of Pregnancy

Attachment anxiety and avoidance

Expectant mothers and fathers completed the 36-item Experiences in Close Relationships questionnaire (Brennan et al., 1998). Participants demonstrated their level of anxiety by indicating their agreement or disagreement with statements such as, “I worry a lot about my relationship” on a 7-point Likert scale. Using the same scale, participants showed their avoidance level through items such as, “I get uncomfortable when a romantic partner wants to be very close.” Cronbach’s alphas for anxiety and avoidance, respectively, were .90 and .92 for mothers and .90 and .88 for fathers.

Couple relationship perceptions

The brief 4-item Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Sabourin, Valois, & Lussier, 2005) was administered to expectant mothers and fathers. Respondents rated the three adjustment questions (e.g., “How often do you discuss or have you considered divorce, separation, or terminating your relationship?”) from 1 = never and 6 = all the time. In addition, participants rated their overall level of happiness in the relationship from 0 = extremely unhappy and 6 = perfect. One item from the brief DAS was dropped due to low item-total correlations. Cronbach’s alphas for the brief DAS were .64 for mothers and .63 for fathers.

Measures: Three Months Postpartum

Perceptions of supportive coparenting

Mothers and fathers completed Feinberg et al.’s (2012) Coparenting Relationship Scale. For this study, we focused on the 6-item coparenting support subscale, which required respondents to rate to what degree they felt supported by their partner with respect to parenting on a 7-point scale (0 = not true of us; 6 = very true of us). Example items included, “When I’m at my wits end as a parent, my partner gives me the extra support I need” and “My partner tells me I am doing a good job or otherwise lets me know I am being a good parent.” Cronbach’s alphas were .86 for mothers and .85 for fathers.

Parenting self-efficacy

Mothers and fathers completed the 10-item Parenting Self-Efficacy Scale (Teti & Gelfand, 1991), which included items such as ‘‘When your baby is upset, fussy or crying, how good are you at soothing him or her?’’ Items were rated from 1 = not good at all to 4 = very good. Cronbach’s alphas were .81 for mothers and .80 for fathers.

Measures: Nine Months Postpartum

Parenting stress

Mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress was measured using 5 items from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (Abidin, 1995; Filippone & Knab, 2005). Respondents rated items such as “Being a parent is harder than I thought it would be” on a scale of 1 = strongly agree to 4 = strongly disagree (α = .66 for mothers and .59 for fathers). Items were reverse scored so higher scores indicated greater parenting stress.

Parenting satisfaction

Mothers’ and fathers’ parenting satisfaction was measured using the 24-item Motherhood/Fatherhood Satisfaction/Meaning Scale (Pistrang, 1984). The questionnaire included statements such as, “My baby makes me feel useful,” with responses ranging from 1 = never to 5 = very often (α = .78 for mothers and .92 for fathers).

Results

Analysis Plan

Descriptive statistics and correlations among the variables of interest were computed. Mediation models were tested using path analyses in IBM SPSS AMOS 22. Full information maximum likelihood estimation was used to estimate parameters without replacing missing data by using all available information from each case. Model fit was assessed according to multiple criteria outlined by Hu and Bentler (1999): the Chi-square test, which indicates adequate fit if non-significant, the Comparative Fit Index (values > .95 are acceptable), and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA; values < .06 are acceptable).

To test our mediation hypotheses, we estimated indirect effects by computation of the product of the path coefficient linking the independent variable and the mediator and the path coefficient linking the mediator and the dependent variable. The significance of these indirect effects was determined via bootstrapping. We used the bootstrapping function in AMOS to obtain 2000 random samples to derive estimates of the indirect effects and their 95% confidence intervals. This approach to testing mediation is preferred because it maximizes statistical power and because the product measure of indirect effect is distributed non-normally (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002; MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). Hypotheses concerning moderation were tested and resulting significant interactions graphed and probed using the SPSS macro developed by Hayes and Matthes (2009).

Preliminary Analyses

As shown in Table 1, descriptive statistics reflected the low-risk nature of this sample. In other words, levels of attachment anxiety and (especially) avoidance were relatively low, as were levels of parenting stress. In contrast, these parents perceived high levels of support from their partners in coparenting, and reported relatively high levels of parenting satisfaction and parenting self-efficacy. Mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of dyadic adjustment, supportive coparenting, parenting stress, and parenting self-efficacy were positively and significantly correlated (Table 2). Regarding anticipated associations, expectant mothers and fathers with greater attachment anxiety and avoidance perceived receiving less supportive coparenting from their partners, and mothers and fathers who perceived receiving more supportive coparenting reported less parenting stress and greater parenting satisfaction. There were also significant associations between mothers’ and fathers’ characteristics. When fathers were more avoidant, mothers perceived lower dyadic adjustment and less supportive coparenting. When mothers perceived more supportive coparenting, greater satisfaction in parenting, and greater parenting self-efficacy, fathers perceived less parenting stress. Fathers reported greater parenting satisfaction when mothers reported greater parenting self-efficacy.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Mothers’ and Fathers’ Psychological Safety and Coparenting Variables

| M | SD | n | M | SD | n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors (Mother’s characteristics) | (Father’s characteristics) | ||||||

| 1. Avoidance | 1.87 | 0.80 | 179 | 8. Avoidance | 2.13 | 0.71 | 174 |

| 2. Anxiety | 3.10 | 1.06 | 180 | 9. Anxiety | 2.64 | 1.01 | 175 |

| 3. Dyadic adjustment | 0.00 | 0.76 | 180 | 10. Dyadic adjustment | 0.00 | 0.76 | 175 |

| 4. Supportive coparenting at three months | 4.99 | 1.07 | 174 | 11. Supportive coparenting at three months | 4.89 | 0.99 | 166 |

| 5. Parenting stress at nine months | 2.07 | 0.50 | 153 | 12. Parenting stress at nine months | 2.00 | 0.46 | 150 |

| 6. Parenting satisfaction at nine months | 3.86 | 0.52 | 153 | 13. Parenting satisfaction at nine months | 3.68 | 0.51 | 151 |

| 7. Parenting self-efficacy | 3.45 | 0.31 | 174 | 14. Parenting self-efficacy | 3.15 | 0.41 | 171 |

Table 2.

Correlations of Mothers’ and Fathers’ Psychological Safety and Coparenting Variables

| Mother’s Characteristics

|

Father’s Characteristics

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

| Predictors (Mother’s characteristics) |

||||||||||||||

| 1. Avoidance | - | |||||||||||||

| 2. Anxiety | .31*** | - | ||||||||||||

| 3. Dyadic adjustment | −.40*** | −.19** | - | |||||||||||

| 4. Supportive coparenting at three months | −.24** | −.19* | .37*** | - | ||||||||||

| 5. Parenting stress at nine months | .04 | .08 | −.09 | −.18* | - | |||||||||

| 6. Parenting satisfaction at nine months | −.15 | −.01 | .19* | .19* | −.29*** | - | ||||||||

| 7. Parenting self-efficacy | .00 | −.08 | .06 | .23** | −.32*** | .30*** | - | |||||||

| (Father’s characteristics) | ||||||||||||||

| 8. Avoidance | .10 | .09 | −.24** | −.18* | −.09 | −.09 | .10 | - | ||||||

| 9. Anxiety | .04 | .07 | −.04 | −.12 | .02 | −.07 | .04 | .40*** | - | |||||

| 10. Dyadic adjustment | −.14 | −.07 | .43*** | .18* | .02 | .14 | −.01 | −.51*** | −.13 | - | ||||

| 11. Supportive coparenting at three months | −.05 | .02 | .26** | .26** | −.05 | .14 | −.05 | −.32*** | −.24** | .48*** | - | |||

| 12. Parenting stress at nine months | −.03 | −.01 | −.06 | −.20* | .22** | −.19* | −.20* | .18* | .32*** | −.24** | −.42*** | - | ||

| 13. Parenting satisfaction at nine months | .13 | .06 | .02 | .07 | .06 | .13 | .20* | −.15 | .01 | .11 | .22** | −.35*** | - | |

| 14. Parenting self-efficacy | .13 | .04 | −.09 | .06 | −.00 | .02 | .22** | −.12 | −.33*** | .07 | .29*** | −.47*** | −.34*** | - |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Mediation Analyses

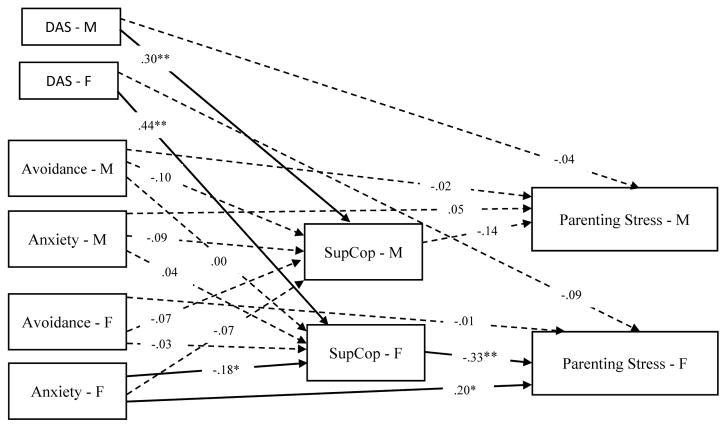

First, a model testing mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of supportive coparenting at 3 months postpartum as mediators of relations between expectant parents’ attachment anxiety and avoidance and their parenting stress at 9 months postpartum was tested. This model controlled for associations of each expectant parent’s perceptions of dyadic adjustment with their perceptions of supportive coparenting and with their parenting stress. As shown in Figure 1, the model fit the data well, χ2(10) = 10.33, p = .41; CFI = .999; RMSEA = .013. Expectant mothers’ and fathers’ dyadic adjustment were each positively associated with their perceptions of supportive coparenting at 3 months postpartum. Of the attachment variables, only expectant fathers’ greater attachment anxiety was associated with lower perceptions of supportive coparenting by fathers at 3 months postpartum. In turn, fathers’ (but not mothers’) perceptions of greater supportive coparenting were associated with lower parenting stress at 9 months postpartum. In addition, expectant fathers’ greater attachment anxiety remained significantly associated with greater parenting stress at 9 months postpartum. With respect to mediation, the indirect effect of expectant fathers’ attachment anxiety on their parenting stress via their perceptions of supportive coparenting was significant (95% CI = 0.024 – 0.166), as was the indirect effect of expectant fathers’ dyadic adjustment on their parenting stress via their perceptions of supportive coparenting (95% CI = −0.083 – −.011).

Figure 1.

Path analysis model testing perceptions of supportive coparenting as mediators of relations between expectant parents’ attachment anxiety and avoidance with their parenting stress at 9 months postpartum. Standardized path coefficients are shown, with solid lines representing significant paths and dashed lines representing nonsignificant paths. All covariances were estimated but are not shown. M = Mother; F = Father; DAS = Dyadic adjustment; SupCop = Supportive Coparenting. Χ2(10) = 10.33, p = .41; CFI = .999; RMSEA = .013. *p < .05 **p < .01.

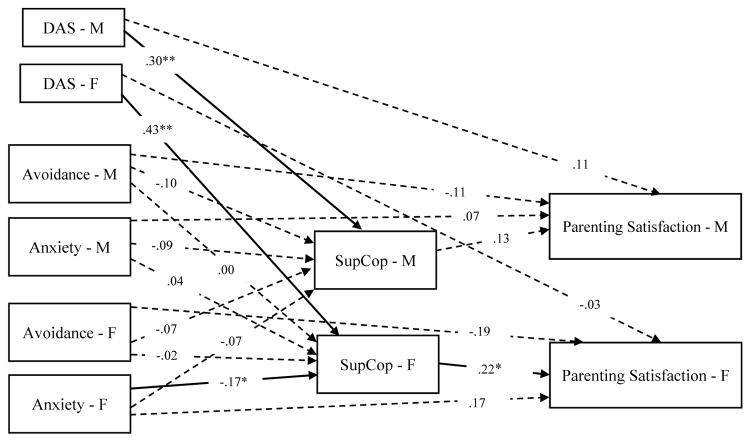

Next, an analogous model testing mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of supportive coparenting at 3 months postpartum as mediators of relations between expectant parents’ attachment anxiety and avoidance and their parenting satisfaction at 9 months postpartum was tested. This model controlled for associations of each expectant parent’s perceptions of dyadic adjustment with their perceptions of supportive coparenting and with their parenting satisfaction. As shown in Figure 2, the model fit the data well, χ2(10) = 6.75, p = .75; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .000. The associations of expectant parents’ dyadic adjustment and attachment orientations with their perceptions of supportive coparenting were the same as in the first model. Fathers’ (but not mothers’) perceptions of greater supportive coparenting were associated with greater parenting satisfaction at 9 months postpartum. In contrast to the model for parenting stress, fathers’ attachment anxiety was not directly associated with their parenting satisfaction. With respect to mediation, the indirect effect of expectant fathers’ attachment anxiety on their parenting satisfaction via their perceptions of supportive coparenting was significant (95% CI = 0.016 – 0.153), as was the indirect effect of expectant fathers’ dyadic adjustment on their parenting satisfaction via their perceptions of supportive coparenting (95% CI = −0.069 – −.005).

Figure 2.

Path analysis model testing perceptions of supportive coparenting as mediators of relations between expectant parents’ attachment anxiety and avoidance with their parenting satisfaction at 9 months postpartum. Standardized path coefficients are shown, with solid lines representing significant paths and dashed lines representing nonsignificant paths. All covariances were estimated but are not shown. M = Mother; F = Father; DAS = Dyadic adjustment; SupCop = Supportive Coparenting. Χ2(10) = 6.75, p = .75; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00. *p < .05 **p < .01.

Moderation Analyses

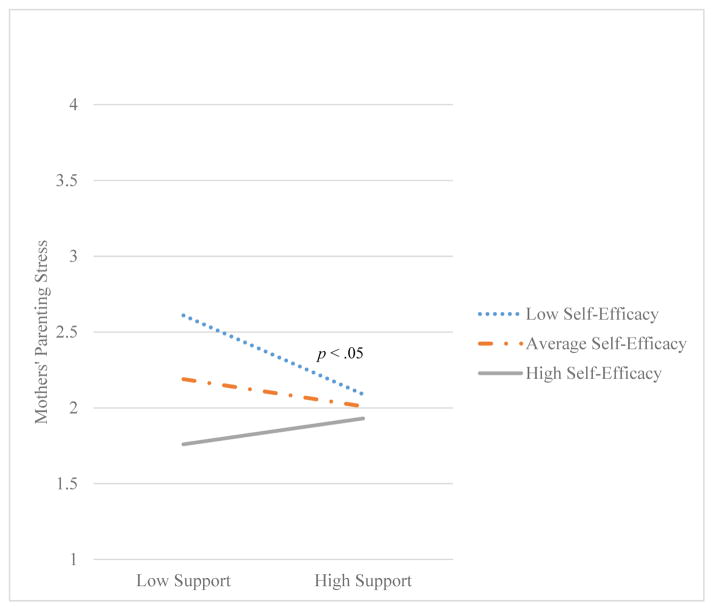

Hierarchical regressions indicated that two of the four significant interactions tested were significant predictors of parental adjustment. Mothers’ parenting self-efficacy moderated the association between her perceptions of supportive coparenting postpartum and parenting stress, ΔR2 = .02, p = .05; B = .27, SE = .13. Simple slopes analyses (Figure 3) indicated that only when mothers’ parenting self-efficacy was low was supportive coparenting negatively associated with parenting stress, B = −.13, SE = .05, p < .05. When mothers’ parenting self-efficacy was average or high, her perceptions of supportive coparenting and parenting stress were not related.

Figure 3.

Parenting Self-Efficacy Moderates the Association between Supportive Coparenting and Mothers' Parenting Stress

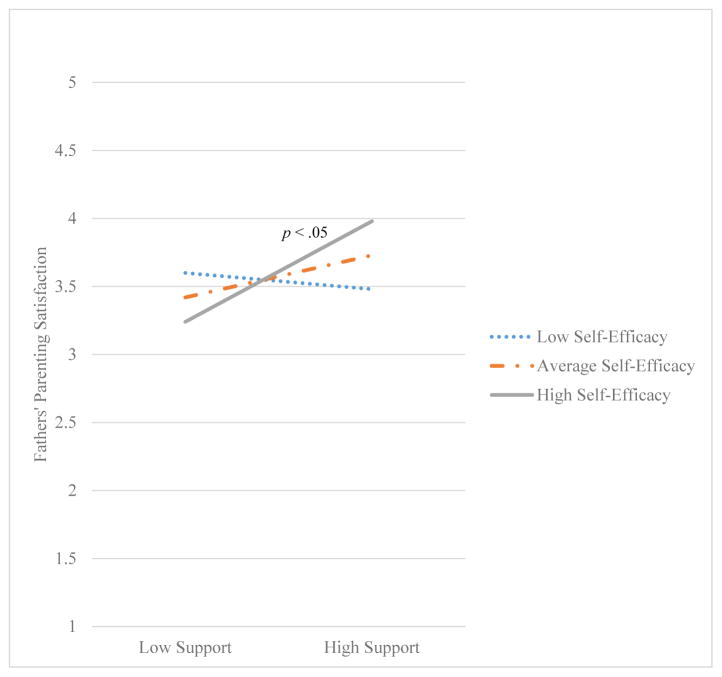

Fathers’ parenting self-efficacy moderated the association between his perceptions of supportive coparenting and his parenting satisfaction, ΔR2 = .03, p < .05; B = .22, SE = .11 (see Figure 4). Simple slopes analyses indicated that only when fathers’ parenting self-efficacy was high was supportive coparenting positively associated with parenting satisfaction, B = .16, SE = .07, p < .05. When fathers’ parenting self-efficacy was average or low, there was no association between his perceptions of supportive coparenting and his parenting satisfaction.

Figure 4.

Parenting Self-Efficacy Moderates the Association between Supportive Coparenting and Fathers' Parenting Satisfaction

Discussion

This study was the first to link the coparenting and organizational literatures by providing evidence that supportive coparenting relationships may be an important context in which new parents – especially fathers – experience psychological safety. Using data from 182 dual-earner male-female couples, we demonstrated that new fathers’ perceptions of supportive coparenting mediated relations between their attachment anxiety in the third trimester of pregnancy and their parenting stress and satisfaction at 9 months postpartum. An analogous mediation process did not appear to operate for mothers. Further, consistent with the notion of adaptive developmental regulations (Lerner, 2015), the fit of the individual and context was relevant to parental adjustment. Parents’ parenting self-efficacy moderated relations between their perceptions of supportive coparenting and their adjustment. When mothers with low levels of parenting self-efficacy perceived their partners as highly supportive of their parenting they experienced lower parenting stress, and when fathers with high parenting self-efficacy perceived their partners as highly supportive of their parenting they experienced greater parenting satisfaction.

Regarding fathers, we found that greater attachment anxiety in the third trimester of pregnancy was associated with perceptions of lower coparenting support at 3 months postpartum, which was in turn associated with greater parenting stress and less parenting satisfaction at 9 months postpartum. That fathers’ attachment anxiety and not avoidance was associated with lower perceptions of supportive coparenting and poorer adjustment to parenthood is consistent with the literature on adult attachment and the transition to parenthood (Simpson et al., 2003). Avoidant individuals are less likely to seek the partner’s support, whereas anxious individuals seek support but find it unsatisfying (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2012). Even after accounting for supportive coparenting, expectant fathers’ greater attachment anxiety continued to be associated with greater parenting stress one year later. Although our mediation model presumed that attachment orientations led to supportive coparenting, which led to parental adjustment, there are certainly feedback loops operating (Wanless, this issue), such that attachment orientations, coparenting, and parental adjustment coevolve over time. For example, new fathers with greater attachment anxiety may experience poor fit in their coparenting relationships, which may exacerbate parenting stress. Fathers experiencing parenting stress may receive less supportive responses from their coparents, which could intensify their stress and attachment anxiety.

We did not find similar results for mothers, however. In the mediation model, expectant mothers’ attachment anxiety and avoidance were not associated with their parenting stress or satisfaction via supportive coparenting. Mothers’ attachment orientations may be linked with their adjustment to parenthood in other ways. That supportive coparenting was more closely associated with parental adjustment for fathers than for mothers was as hypothesized, and reflects the particular sociopolitical context in which the couples we studied were embedded, in which expectations for fathers’ involvement in parenting are strong (Gerson, 2009), but mothers still have higher status as parents (Kotila et al., 2013). Thus, fathers’ adaptation to parenthood may be closely intertwined with perceptions of mothers’ support of their parenting.

It would be misguided to conclude, however, that perceptions of supportive coparenting were irrelevant to the parental adjustment of new mothers. Moderation analyses – which considered the fit between the individual and context – revealed that for mothers with low parenting self-efficacy, perceptions of stronger supportive coparenting from their partners were linked to lower parenting stress. In other words, for less confident mothers, perceptions of support for their parenting efforts by their partners appeared to bolster their parental adjustment. This finding is consistent with the psychological safety literature, which has shown that a psychologically safe work environment matters most for employee knowledge sharing when employees are less confident in their knowledge (Siemsen et al., 2009).

Moreover, it would also be premature to conclude that high parenting satisfaction is accompanied by high supportive coparenting for all fathers. In fact, supportive coparenting appeared to enhance the parenting satisfaction of only those fathers with relatively high levels of parenting self-efficacy. This was an unexpected finding, but perhaps highly confident and competent fathers rightfully expect support for their efforts, and when they do receive it from their coparenting partners are more satisfied with the parenting experience than other fathers, but when they do not receive it from their coparenting partners are more dissatisfied with the parenting experience than other fathers. These speculations await confirmation in future research. Overall, results of our moderation analyses show that as one variable shifts, the ways all the other pieces of the system function and interact with each other change as well. This becomes a qualitative transformation that impacts every aspect of the system.

Another important component of the developing family system is the preexisting couple relationship, which appears to be an important foundation for the psychological safety coparents may experience in the early postpartum months. Expectant parents’ perceptions of the couple relationship were consistently associated with their perceptions of supportive coparenting in the early postpartum months, consistent with prior research (e.g., Van Egeren, 2004). In addition, for fathers, perceptions of supportive coparenting mediated relations between perceptions of the couple relationship and parenting stress and satisfaction at 9 months postpartum.

The contributions of this study must be viewed in light of its limitations. The measures used in this study were self-reports, and individuals’ perceptions of interpersonal interactions are critical to psychological safety. That said, self-reports are subject to associated biases and shared method variance, and future research should incorporate alternative measures of adult attachment and observations of coparenting behavior. We also note that the measures of parenting stress and dyadic adjustment demonstrated only modest internal consistency in this sample. Finally, the sample we studied is not representative of the general population of new parents and whether these findings generalize to coparents other than dual-earner male-female couples is unknown.

In sum, coparenting relationships may serve as a haven of psychological safety for new parents, and especially new fathers in dual-earner families in the U.S., who are experiencing a profound, life-changing transformation of roles and relationships in a sociopolitical time characterized by changing roles for fathers, high expectations for parents, and few policy supports. Continuing to seek a better understanding of the ways in which strong coparenting relationships may promote feelings of psychological safety for new parents will help ensure that the transition to parenthood is a period of successful adaptation and the growth of individual strengths and developmental assets for all members of the family system.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the many graduate and undergraduate students who recruited for, and collected, entered, and coded the data of, the New Parents Project as well as the families who participated in the research. The New Parents Project was funded by the National Science Foundation (CAREER 0746548, Schoppe-Sullivan), with additional support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD; 1K01HD056238, Kamp Dush), and The Ohio State University’s Institute for Population Research (NICHD R24HD058484) and program in Human Development and Family Science.

References

- Abidin RR. Parenting Stress Index. 3. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander R, Feeney J, Hohaus L, Noller P. Attachment style and coping resources as predictors of coping strategies in the transition to parenthood. Personal Relationships. 2001;8(2):137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Mikus K. The power of parenthood: Personality and attitudinal changes during the transition to parenthood. In: Michaels GY, Goldberg WA, editors. The transition to parenthood: Current theory and research. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1988. pp. 62–84. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Rovine M. Social-network contact, family support, and the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1984;46(2):455–462. doi: 10.2307/352477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and anger. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1998. pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GL, Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Mangelsdorf SC, Neff C. Observed and reported supportive coparenting as predictors of infant-mother and infant-father attachment security. Early Child Development and Care. 2010;180(1–2):121–137. doi: 10.1080/03004430903415015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson AC, Lei Z. Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior. 2014;1:23–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J, Lee Y. Longitudinal associations among fathers' perception of coparenting, partner relationship quality, and paternal stress during early childhood. Family Process. 2014;53(1):80–96. doi: 10.1111/famp.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney JA. Adult attachment, involvement in infant care, and adjustment to new parenthood. Journal of Systemic Therapies. 2003;22(2):16–30. doi: 10.1521/jsyt.22.2.16.23344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME, Brown LD, Kan ML. A multi-domain self-report measure of coparenting. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2012;12(1):1–21. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2012.638870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME, Jones DE, Kan ML, Goslin MC. Effects of family foundations on parents and children: 3.5 years after baseline. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24(5):532–542. doi: 10.1037/a0020837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippone M, Knab J. Fragile Families Scales Documentation and Question Sources for One-Year Questionnaires. Center for Research on Child Well-Being; 2005. Retrieved from http://www.fragilefamilies.princeton.edu/documentation/core/scales/ff_1yr_scales.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gerson K. The unfinished revolution: Coming of age in a new era of gender, work, and family. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Matthes J. Computational procedures for proving interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41(3):924–936. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.3.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Whitley MK. Treatment of parental stress to enhance therapeutic change among children referred for aggressive and antisocial behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(3):504–515. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.3.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotila LE, Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Kamp Dush CM. Time in parenting activities in dual-earner families at the transition to parenthood. Family Relations. 2013;62(5):795–807. doi: 10.1111/fare.12037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM. Promoting positive human development and social justice: Integrating theory, research and application in contemporary developmental science. International Journal of Psychology. 2015;50(3):165–173. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(1):83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39(1):99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Florian V. The association between spouses' self-reports of attachment styles and representations of family dynamics. Family Process. 1999;38(1):69–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1999.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Adult attachment orientations and relationship processes. Journal of Family Theory & Review. 2012;4(4):259–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-2589.2012.00142.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Overton WF. Handbook of child psychology and developmental science, 7th edition. Volume 1: Theory and method. Wiley; 2015. Processes, relations, and relational-developmental-systems; pp. 9–62. [Google Scholar]

- Pedro MF, Ribeiro T, Shelton KH. Romantic attachment and family functioning: The mediating role of marital satisfaction. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0150-6. Advance online publication. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pistrang N. Women's work involvement and experience of new motherhood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1984;46(2):433–447. doi: 10.2307/352475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rholes WS, Simpson JA, Blakely BS, Lanigan L, Allen EA. Adult attachment styles, the desire to have children, and working models of parenthood. Journal of Personality. 1997;65(2):357–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1997.tb00958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roxburgh S. Parental time pressures and depression among married dual-earner parents. Journal of Family Issues. 2012;33(8):1027–1053. doi: 10.1177/0192513X11425324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sabourin S, Valois P, Lussier Y. Development and validation of a brief version of the dyadic adjustment scale with a nonparametric item analysis model. Psychological Assessment. 2005;17(1):15–27. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.17.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Brown GL, Cannon EA, Mangelsdorf SC, Sokolowski MS. Maternal gatekeeping, coparenting quality, and fathering behavior in families with infants. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22(3):389–398. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Mangelsdorf SC, Frosch CA, McHale JL. Associations between coparenting and marital behavior from infancy to the preschool years. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(1):194–207. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemsen E, Roth AV, Balasubramanian S, Anand G. The influence of psychological safety and confidence in knowledge on employee knowledge sharing. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management. 2009;11(3):429–447. doi: 10.1287/msom.1080.0233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Rholes WS, Campbell L, Tran S, Wilson CL. Adult attachment, the transition to parenthood, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84(6):1172–1187. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teti DM, Gelfand DM. Behavioral competence among mothers of infants in the first year: The mediational role of maternal self-efficacy. Child Development. 1991;62(5):918–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teubert D, Pinquart M. The association between coparenting and child adjustment: A meta-analysis. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2010;10(4):286–307. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2010.492040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Egeren LA. The development of the coparenting relationship over the transition to parenthood. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2004;25(5):453–477. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wanless SB. Considering the role of psychological safety in human development. Research in Human Development in press. [Google Scholar]