Abstract

Globally, our social worlds are becoming increasingly racially and ethnically diverse. Despite this, little attention has been given to how children negotiate this diversity. In this study we examine whether a value-in-diversity storybook intervention encourages young children to engage in intergroup contact with racially diverse peers. The lunchroom seating behaviour of 4- to 6-year-olds attending three racially diverse primary schools was recorded at three different points during a one-week period. Seating behaviour was coded based on the race of the children and levels of segregation were calculated (Campbell et al., 1996). Before hearing the story, we observed racial self-segregation; children were more likely to sit with same-race peers. However, immediately following the story, children were no longer significantly racially segregated. This effect was not maintained; up to 48 hours later children again showed evidence of racial self-segregation. Our findings suggest that exposure to racially diverse peers alone is not sufficient for promoting intergroup contact. We argue that it is vital to develop sustainable teacher-led interventions if we are to harness the potential of diverse school settings for bolstering intergroup relations.

Keywords: diversity, intergroup contact, intergroup behaviour, children

Our world is becoming increasingly diverse; by 2056 racial/ethnic minorities are expected to account for one third of the total U.K. population (Coleman, 2010). Evidence suggests that placing value-in-diversity, rather than adopting a colourblind approach to race, has positive outcomes for intergroup relations with adults (e.g., Rattan & Ambady, 2013). However, little research has examined how such approaches to race may affect children’s behaviour in diverse settings (c.f. Apfelbaum, Pauker, Sommers, & Ambady, 2010). To address this gap in the literature we examine whether promoting a value-in-diversity mind-set can facilitate 4- to 6-year-olds’ interactions with their diverse peers in school.

Promoting Intergroup Contact in Education

Diverse classrooms increase the opportunity for intergroup friendships to form (Moody, 2001; Turner, Tam, Hewstone, Kenworthy, & Cairns, 2013), but more than physical proximity is necessary to promote positive intergroup contact and cross-race friendships (Turner & Cameron, 2016; Wessell, 2009). For example, research examining intergroup behaviour in diverse settings has demonstrated that children and young people do not spontaneously engage in intergroup contact with diverse peers (e.g., Echols, Solomon, & Graham, 2014; McCauley, Plummer, Moskalenko, & Mordkoff, 2001; McKeown, Stringer & Cairns, 2016). Thus, while diverse classrooms can offer the exciting opportunity to promote positive intergroup interactions (Hewstone, 2015), aspects of the school environment may support or hinder students engagement in positive intergroup interactions (Thijs & Verkuyten, 2014).

Negotiating Racial Diversity

A school climate that values diversity can foster inclusive peer relations. Western societies have two dominant strategies for managing racial diversity: colourblindness and multiculturalism. A colourblind approach emphasizes disregarding racial categories and treating people as individuals (Rattan & Ambady, 2013). However, striving to avoid race may ironically lead to more tension in race-relevant situations (Pauker, Apfelbaum, & Spitzer, 2015). By contrast, a multicultural strategy places value in diversity by acknowledging and celebrating racial group memberships (Rattan & Ambady, 2013).

Although different approaches for managing diversity are used across classrooms, little empirical research has examined whether these strategies promote positive intergroup relations in childhood. A recent study conducted by Apfelbaum and colleagues (2010) found that predominately White 8- to 11-year-olds who read a value-in-diversity (where racial differences were valued) compared to colourblind (where racial differences were minimised) story were more likely to detect racial discrimination when it occurred and describe incidents in a way that encouraged teacher intervention (Apfelbaum et al., 2010; see also Levy et al., 2005). Thus, some evidence suggests promoting a value-in-diversity mindset may encourage positive intergroup relations in childhood.

The Present Research

To date there is a lack of behavioural-focused research with young children in racially diverse contexts. This gap is important to fill, as research in this area will contribute to our theoretical understanding of segregation, contact, and diversity strategies in young children—a population that would benefit greatly from targeted interventions based on theory.

Here, we examined whether 4- to 6-year-olds will be more likely to interact with their diverse peers after hearing a value-in-diversity storybook (Apfelbaum et al., 2010). Typically, researchers have examined racial segregation among older children, however, since 4- to 6-year-olds can consistently categorise others by race and demonstrate biases that favour the racial ingroup (see Pauker, Williams, & Steele, 2016; Raabe & Beelmann, 2011, for reviews), it is possible that children will demonstrate racially segregated behaviour in the early school years (e.g., Fishbein & Imai, 1993). Based on previous research demonstrating behaviour change following a contact-based intervention amongst adolescents (McKeown, Cairns, Stringer, & Rae, 2012), we expect to observe racial segregation before children hear the value-in-diversity story (Time 1) but that such racial segregation will decrease after hearing the story (Time 2). To examine the longevity of the intervention, we also observed children’s behaviour up to 48 hours after they heard the story (Time 3).

Method

Participants

Students in Reception and Year 1 classes (aged 4- to 6-years) from three racially diverse primary schools in Southwest England participated. Averaging across the three time points, our sample consisted of White (44.61%), Black (45.94%), and East Asian or South Asian (9.45%) boys (64.46%) and girls (35.54%). We observed the self-selected seating behaviour of children at Time 1 (n =176), at Time 2 (n =173), and at Time 3 (n =180).

Materials and Procedure

Reception and Year 1 children intermingled and self-selected their seats in the lunchroom. We recorded where children sat on three separate days over the course of one school week. On the first day we measured baseline seating behaviour. On the second day, classroom teachers read their students a value-in-diversity story (adapted from Apfelbaum et al., 2010). The story focused on a teacher’s efforts to promote racial equality by acknowledging and valuing the racial differences of students in her class and took approximately 10 minutes. This was followed by approximately 10 minutes of discussion centered on the key message of the story. This classroom activity was designed to promote a value-in-diversity mind-set in the listeners. Immediately following the story (Time 2) and up to 2 days later (Time 3),1 we recorded who children sat next to in the lunchroom to determine if the story influenced seating behaviour.

Coding for Behaviour

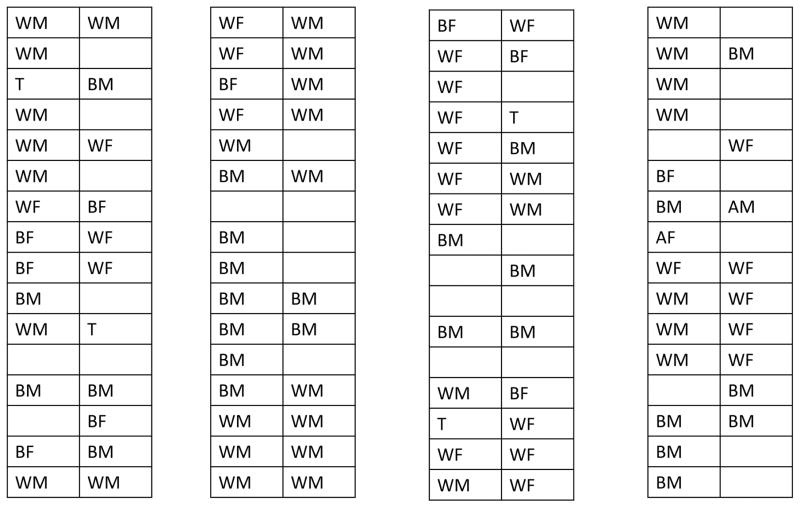

In two schools, the two first authors took photographs of the lunchroom to later independently code children by race (White, Black, Asian); they cross-checked categorisations for consistency and resolved discrepancies through discussion. In the remaining school, manual coding took place in the lunchroom; the first two authors independently coded the room and then immediately cross-checked the categorisations and resolved any discrepancies on-site while the children were still present. In all cases, the researchers reached 100% agreement on race categorisations. See Figure 1 for an example of coding.

Figure 1.

Results

Calculating Segregation

Race segregation was calculated using the Campbell et al. (1966) seating aggregation index: I value. The index measures voluntary clustering in row wise contingencies by calculating the number of expected adjacencies under random conditions and comparing it to the actual adjacencies found.2 Negative I values indicate more segregation compared to what would be expected by chance and positive I values indicate less segregation than what would be expected by chance.

For each lunchroom, separate I values were calculated for each data collection point based on the children’s race. I values for Black, White, and Asian children were averaged into a single score that reflected race segregation. Thus for each time point, the seating behaviour of over 170 children was collapsed into three I values (one for each lunchroom) representing race segregation.

Analysis of Segregation

A series of one-sample t-tests comparing I scores to 0 were conducted to examine whether seating behaviour revealed significant segregation as compared to chance. See Table 1 for descriptive statistics.

Table 1.

Mean I values (SD) for race segregation at Time 1, Time 2 and Time 3.

| Race Segregation | |

|---|---|

| Time 1 (Pre-Story) | −.43* (.12) |

| Time 2 (Immediately Post-Story) | −.32 (.23) |

| Time 3 (Up to 48 hours Post-Story) | −.41* (.09) |

At Time 1, children demonstrated significant self-segregation and were more likely to sit next to same-race peers, t(2) = -6.13, p = .03, d = 3.54. However, immediately following the value-in-diversity storybook intervention, children no longer demonstrated significant race segregation, t(2) = -2.44, p = .14, d = 1.14. This effect was not maintained up to 48 hours later, t(2) = -8.35, p = .014, d = 4.82; at Time 3 children were again significantly more likely to self-segregate by race as compared to chance.

Discussion

In this study, we examined whether a value-in-diversity storybook intervention would be successful in encouraging young children (aged 4- to 6-years) to interact with diverse peers. When left to their own devices (Time 1), children showed evidence of racial segregation. Demonstrating the effectiveness of promoting a value-in-diversity mind-set for facilitating intergroup contact, immediately after hearing the story (Time 2), children no longer showed racially segregated behaviour. Unfortunately, this effect was short-lived. Up to 48 hours after hearing the story (Time 3), children again demonstrated significant racial segregation.

Our findings highlight that a multicultural approach to diversity can facilitate intergroup contact even amongst very young children. Building on previous research where a value-in-diversity mind-set successfully altered children’s perceptions of racial discrimination (Apfelbaum et al. 2010), we provide evidence that the same storybook intervention effectively altered 4- to 6-year-olds’ behaviour. Together these results suggest that teaching children to manage racial diversity using strategies that value diversity can effectively promote positive intergroup relations in childhood.

Determining which diversity strategies best promote intergroup contact in childhood may be important for reducing outgroup prejudice (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). On its own, exposure to racial diversity is a necessary but not sufficient condition for intergroup contact (McKeown et al., 2016; Turner & Cameron, 2016; Wessell, 2009). To promote intergroup contact we need to go beyond merely bringing racially diverse children together. Even when surrounded by diverse peers, children tended to self-segregate by race (Time 1). It was only immediately after hearing a value-in-diversity story that children no longer displayed racially segregated seating behaviour (Time 2), but this effect was short-lived.

Our findings suggest that intergroup contact may be sustained in young children through messages that place value in racial diversity, but such messages need to be integrated into the curriculum and adopted at a broader institutional level rather than simply communicated in a one-shot intervention (Thijs & Verkuyten, 2014). If we are to harness the potential of diverse school settings for bolstering intergroup relations, it is vital to develop sustainable teacher-led interventions.

Limitations and Future Directions

We provide evidence that an easily administered classroom-based intervention can alter young children’s intergroup behaviour (at least temporarily). Although speculative, in line with research with older children, it is possible that the value-in-diversity storybook intervention changes perceptions of inclusive norms (e.g., Tropp, O’Brien & Migacheva, 2014), reduces bias through increasing exposure to counterstereotypical exemplars (e.g., Gonzalez, Steele, & Baron, 2017) or reduces anxiety about interacting with racially diverse peers (Stephan & Stephan, 1985). Further research is needed to examine the mechanism underlying the observed behavioural change.

The applied nature of this research constrained our experimental design. In the lunchrooms, children from different classrooms had the opportunity to interact with each other making it unclear which child initiates the contact. Therefore, we were unable to include a comparison control condition due to potential difficulties in interpreting the effects. Thus, we utilised a pre- and post-test design to compare seating behaviour before and after the storybook intervention across three diverse settings. This design lends confidence to our interpretation that behaviour changed as a result of the intervention and not because of to school- or class-specific effects. However, future experimental research is needed to replicate these results. Finally, our focus on behaviour was innovative and allowed us to examine changes in direct contact. But to more fully capture the impact of diversity during childhood, future research should encompass a wide variety of antecedents (e.g., school norms, peer norms) and consequences (e.g., behaviour, academic performance) over a longer period of time.

Conclusion

We provide evidence that promoting a value-in-diversity mind-set encouraged intergroup contact amongst young children attending racially diverse schools. Given the benefits of intergroup contact for positive intergroup relations, it is important to evaluate how we can best encourage intergroup friendship formation in diverse settings. Whilst our findings show that even young children racially segregate themselves, we demonstrate that promoting value in racial diversity can lead children to integrate with diverse peers in the lunchroom. Therefore, using strategies that value diversity in a sustained way is a vital step in promoting diverse friendships in early childhood.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the schools, teachers, parents, and children who generously provided us with the opportunity to conduct this research.

Sponsors: This research was supported by a University of Bristol Faculty of Social Sciences and Law Strategic Research Initiatives Scheme awarded to the second author and a NICHD award R00HD065741 to the third author.

Footnotes

Time 3 observations occurred the following day for one school and two days later for two schools because of previously scheduled school activities.

We chose this index because children sat in rows in the lunchroom and because informal observations revealed that children interacted more with the peers next to them than those across the table.

Contributor Information

Shelley McKeown, University of Bristol, UK.

Amanda Williams, University of Bristol, UK.

Kristin Pauker, University of Hawai’i, USA.

References

- Apfelbaum EP, Pauker K, Sommers SR, Ambady N. In blind pursuit of racial equality? Psychological Science. 2010;21:1587–1592. doi: 10.1177/0956797610384741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DT, Kruskal WH, Wallace WP. Seating Aggregation as an Index of attitude. Sociometry. 1966;29:1–15. doi: 10.2307/2786006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman D. Projections of the ethnic minority populations of the United Kingdom 2006–2056. Population and Development Review. 2010;36:441–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echols L, Solomon BJ, Graham S. Same spaces, different races: What can cafeteria setting patterns tell us about intergroup relations in middle school? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2014;20:611–620. doi: 10.1037/a0036943. doi:10/1037/a0036943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein HD, Imai S. Preschoolers select playmates on the basis of gender and race. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1993;14:303–316. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez AM, Steele JR, Baron AS. Reducing children’s implicit racial bias through exposure to positive outgroup exemplars. Child Development. 2017;88:123–130. doi: 10.111/cdev.12582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewstone M. Consequences of diversity for social cohesion and prejudice: The missing dimension of intergroup contact. Journal of Social Issues. 2015;71:417–438. doi: 10.1111/josi.12120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levy SR, West TL, Bigler RS, Karafantis DM, Ramirez L, Velilla E. Messages about the uniqueness and similarities of people: Impact on US Black and Latino youth. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2005;26:714–733. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2009.06.001. [Google Scholar]

- McCauley C, Plummer M, Moskalenko S, Mordkoff JB. The exposure index: A measure of intergroup contact. Journal of Peace Psychology. 2001;7:321–336. doi: 10.1207/S15327949PAC0704_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown S, Cairns E, Stringer M, Rae G. Micro-ecological behavior and intergroup contact. Journal of Social Psychology. 2012;152:340–358. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2011.614647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown S, Stringer M, Cairns E. Classroom segregation: where do students sit and what does it mean for intergroup relations? British Educational Research Journal. 2016;40:40–55. doi: 10.1002/berj.3200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moody J. Race, School Integration, and Friendship Segregation in America. American Journal of Sociology. 2001;107:679–716. [Google Scholar]

- Pauker K, Apfelbaum EP, Spitzer B. When societal norms and social identity collide: The race talk dilemma for racial minority children. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1948550615598379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauker K, Williams A, Steele JR. Children’s racial categorization in context. Child Development Perspectives. 2016;10:33–38. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90:751–783. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raabe T, Beelmann A. Development of ethnic, racial, and national prejudice in childhood and adolescence: A multinational meta-analysis. Child Development. 2011;82:1715–1737. doi: 10.111/j/1467-8624.2011.01668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattan A, Ambady N. Diversity ideologies and intergroup relations: An examination of colorblindness and multiculturalism. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2013;43:12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan WG, Stephan C. Intergroup anxiety. Journal of Social Issues. 1985;41:157–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1985.tb01134.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thijs J, Verkuyten M. School ethnic diversity and students’ interethnic relations. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 2014;84:1–21. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropp LR, O’Brien TC, Migacheva K. How peer norms of inclusion and exclusion predict children’s interest in cross-ethnic friendships. Journal of Social Issues. 2014;70:151–166. doi: 10.1111/josi.12052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RN, Cameron L. Confidence in contact: A new perspective on promoting cross-group friendship among children and adolescents. Social Issues and Policy Review. 2016;10:212–246. doi: 10.1111/sipr.12023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RN, Tam T, Hewstone M, Kenworthy J, Cairns E. Contact between Catholic and Protestant school children in Northern Ireland. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2013;43:E216–E228. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wessel T. Does diversity in urban space enhance intergroup contact and tolerance? Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography. 2009;91:5–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0467.2009.00303.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]