Abstract

The RNASEL gene (2’, 5’-oligoisoadenylate synthetase-dependent) encodes a ribonuclease that plays a significant role in the apoptotic and antiviral activities of interferons. Various studies have used polymorphisms in the RNASEL gene to evaluate prostate cancer risk but studies that show an association between RNASEL Arg462Gln (1385G>A, R462Q, rs486907) polymorphism and prostate cancer risk are somewhat inconclusive. To assess the impact of RNASEL Arg462Gln polymorphism on prostate cancer risk, we conducted a meta-analysis of all available studies including 11,522 patients and 10,976 control subjects. The overall results indicated no positive association between the variant and prostate cancer risk. However, in a subgroup analysis by ethnicity, obvious associations were observed in Hispanic Caucasians for allelic contrast (OR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.00 - 1.39, Pheterogeneity = 0.010), homozygote comparison (OR = 1.50, 95% CI = 1.02 – 2.20, Pheterogeneity = 0.001), and the recessive genetic model (OR = 1.44, 95% CI = 1.01 - 2.05, Pheterogeneity = 0.002) ; and in African descendants for homozygote comparison (OR = 2.59, 95% CI = 1.29 – 5.19, Pheterogeneity = 0.194) and the recessive genetic model (OR = 2.61, 95% CI = 1.30 – 5.23, Pheterogeneity = 0.195). In conclusion, the RNASEL Arg462Gln polymorphism may contribute to the risk of developing prostate cancer in African descendants and Hispanic Caucasians. Further larger and well-designed studies are warranted to evaluate this association in detail.

Keywords: RNASEL, polymorphism, prostate cancer, meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer (PCa) is one of the most common types of neoplasm in the Western world. In United States, prostate cancer is the most prevalent cancer, with 217,730 new cases predicted to occur in 2010 [1]. The etiology of PCa is still poorly understood, but exposure to hormones, infectious agents, or dietary carcinogens may contribute to inflammation of the prostate [2, 3]. Intraprostatic inflammation may affect the tissue microenvironment, promoting genetic damage, and driving cellular proliferation, which may lead to prostate carcinogenesis [4, 5]. Prior studies have suggested that family history is the most reproducible and significant risk factor. Men with a brother or father diagnosed with PCa were twice as likely to develop this cancer as men with no relatives affected [6].

Ribonuclease L (RNASEL), which is considered to be a tumor-suppressor gene, plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of prostate cancer through inflammation and infection. RNASEL is on chromosome 1q24-25 and encodes Ribonuclease L, a significant enzyme of the interferon-induced antiviral 2-5A system [7]. Mutation of RNASEL can lead to dysfunction of Ribonuclease L in regulating single-stranded RNA cleavage, cellular viral defense, and tumor suppressor activities, such as stress-mediated apoptosis and regulation of protein synthesis [8–9].

Extensive epidemiological studies had been conducted to explore the association between RNASEL polymorphism and prostate cancer risk. A G-to-A transversion at nucleotide position 1385 (rs486907), which results in a glutamine instead of arginine at amino acid position 462 (R462Q), is one of the most widely investigated polymorphisms in RNASEL. Nevertheless, the association between the RNASEL R462Q polymorphism and prostate cancer risk is controversial because of conflicting case–control studies. Therefore, in this meta-analysis from all eligible studies published to date [10–32], we used enhance statistical power to understand the effect of this variant.

RESULTS

Study characteristics

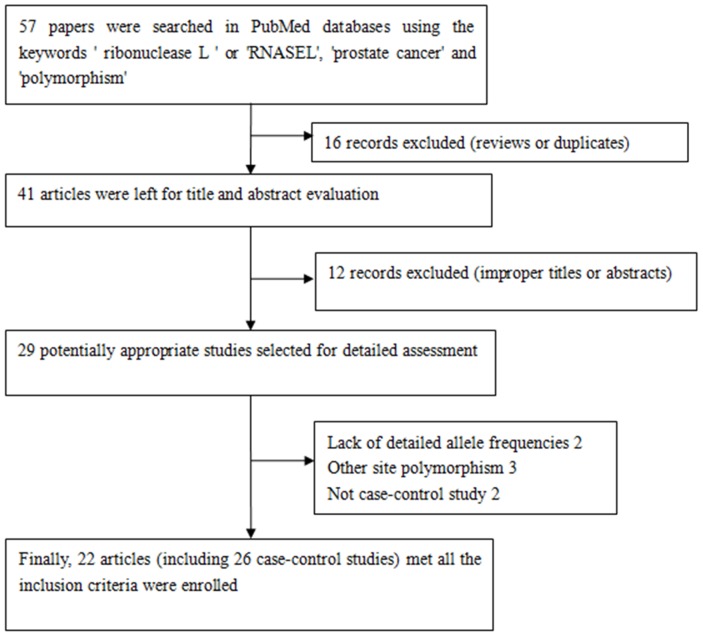

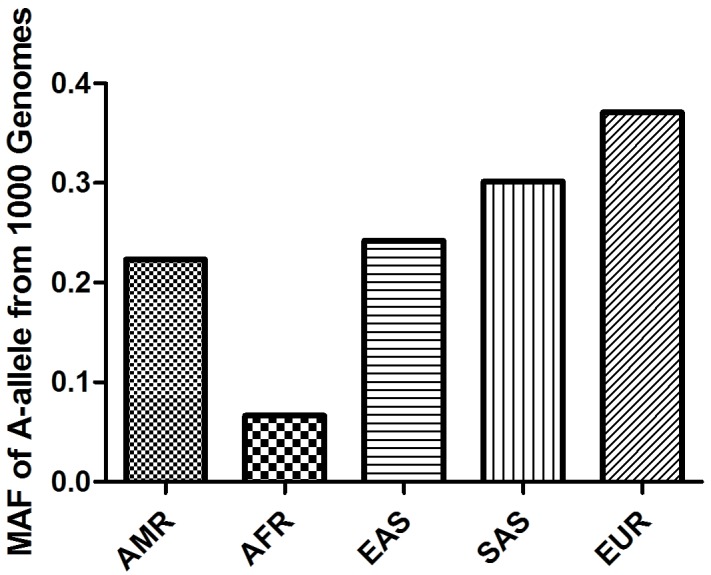

A total of 22 articles (including 26 case–control studies) met all the inclusion criteria and were included (Figure 1). The genotype distribution of the control population was consistent with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in 19 of the publications. Characteristics of the eligible studies are summarized in Table 1. In general, 11,522 prostate cancer patients and 10,976 control subjects with the RNASEL Arg462Gln polymorphism were evaluated. In the ethnic subgroups, 17 case–control studies were performed with European descendants, three with Asian descendants, and four with African descendants. We checked the Minor Allele Frequency (MAF) reported for the five main worldwide populations in the 1000 Genomes Browser: East Asian, 0.2421; European, 0.3708; African, 0.0666; American, 0.2233; and South Asian, 0.3016. The MAF in our analysis was 0.3034 and 0.2900 in the case and control group, respectively (Figure 2). Hospital-based controls were carried out in 15 of the studies. TaqMan real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), the classical genotyping method, was utilized in 10 comparisons. Five studies used the GoldenGate platform or Sequenom MassARRAY platform genotyping method. Six publications had genotype frequency information for familial and sporadic prostate cancer cases.

Figure 1. Flowchart illustrating the search strategy used to identify association studies for RNASEL Arg462Gln polymorphism and prostate cancer risk.

Table 1. Study characteristics of RNASEL Arg462Gln (1385G>A) polymorphism included in this meta-analysis.

| First author | Year | Country | Ethnicity | Source of | Genotype method | Sample size of case | Sample size of control | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| control | GG | GA | AA | Total | MAF | HWE | GG | GA | AA | Total | MAF | HWE | |||||

| Babaei | 2015 | Iran | Asian | HB | PCR | 20 | 15 | 5 | 40 | 0.313 | 0.421 | 44 | 32 | 4 | 80 | 0.250 | 0.551 |

| Alvarez-Cubero | 2015 | Spain | Hispanic | HB | Goldengate assay | 80 | 120 | 37 | 237 | 0.409 | 0.468 | 61 | 114 | 41 | 216 | 0.454 | 0.342 |

| Winchester | 2015 | USA | Non-Hispanic | PB | Goldengate assay | 352 | 407 | 105 | 864 | 0.357 | 0.445 | 330 | 372 | 129 | 831 | 0.379 | 0.157 |

| San Francisco | 2014 | Chile | Hispanic | PB | Taqman | 43 | 31 | 9 | 83 | 0.295 | 0.351 | 28 | 14 | 4 | 46 | 0.239 | 0.267 |

| Reza | 2012 | Iran | Asian | HB | Taqman | 64 | 73 | 44 | 181 | 0.445 | 0.014 | 14 | 4 | 1 | 19 | 0.158 | 0.364 |

| Sakuma | 2011 | USA | Caucasian | HB | Real-time PCR | 43 | 55 | 12 | 110 | 0.359 | 0.366 | 11 | 21 | 8 | 40 | 0.463 | 0.723 |

| Beuten | 2010 | USA | Hispanic | HB | Goldengate assay | 75 | 64 | 17 | 156 | 0.314 | 0.550 | 126 | 91 | 7 | 224 | 0.234 | 0.048 |

| Meyer | 2010 | USA | Caucasian | PB | Sequenom MassARRAY | 529 | 547 | 159 | 1235 | 0.350 | 0.346 | 505 | 546 | 159 | 1210 | 0.357 | 0.551 |

| Martinez-Fierro | 2010 | Mexico | Mixed | HB | Taqman | 9 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 0.091 | 0.041 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 0.182 | 0.197 |

| Agalliu | 2010 | USA | Non-Hispanic | PB | Pyrosequencing | 467 | 414 | 84 | 965 | 0.302 | 0.566 | 572 | 556 | 109 | 1237 | 0.313 | 0.110 |

| Wang | 2009 | USA | Caucasian | PB | Taqman | 100 | 121 | 27 | 248 | 0.353 | 0.282 | 88 | 132 | 33 | 253 | 0.391 | 0.130 |

| Fischer | 2008 | Germany | Non-Hispanic | HB | Real time PCR | 51 | 29 | 7 | 87 | 0.247 | 0.331 | 42 | 24 | 4 | 70 | 0.229 | 0.816 |

| Robbins | 2008 | USA | African | HB | Sequenom MassARRAY | 183 | 55 | 5 | 243 | 0.134 | 0.718 | 225 | 66 | 5 | 296 | 0.128 | 0.950 |

| Shea | 2008 | USA | African | PB | PCR | 187 | 41 | 2 | 230 | 0.098 | 0.881 | 362 | 88 | 2 | 452 | 0.102 | 0.168 |

| Shook | 2007 | USA | African | HB | Taqman | 45 | 13 | 10 | 68 | 0.243 | <0.001 | 111 | 31 | 3 | 145 | 0.128 | 0.633 |

| Shook | 2007 | USA | Hispanic | HB | Taqman | 72 | 62 | 16 | 150 | 0.313 | 0.629 | 136 | 96 | 7 | 239 | 0.230 | 0.039 |

| Shook | 2007 | USA | Non-Hispanic | HB | Taqman | 187 | 183 | 60 | 430 | 0.352 | 0.162 | 221 | 225 | 57 | 503 | 0.337 | 0.981 |

| Cybulski | 2007 | Poland | Non-Hispanic | PB | PCR-RFLP | 245 | 376 | 116 | 737 | 0.412 | 0.153 | 177 | 252 | 82 | 511 | 0.407 | 0.625 |

| Daugherty | 2007 | USA | Non-Hispanic | HB | TaqMan | 463 | 505 | 148 | 1116 | 0.359 | 0.578 | 554 | 602 | 188 | 1344 | 0.364 | 0.235 |

| Daugherty | 2007 | USA | African | HB | TaqMan | 73 | 23 | 2 | 98 | 0.138 | 0.905 | 277 | 98 | 5 | 380 | 0.142 | 0.261 |

| Maier | 2005 | Germany | Non-Hispanic | PB | PCR | 133 | 171 | 59 | 363 | 0.398 | 0.746 | 73 | 97 | 37 | 207 | 0.413 | 0.629 |

| Nam | 2005 | Canada | Mixed | PB | Mass spectrometry | 477 | 409 | 110 | 996 | 0.316 | 0.117 | 521 | 459 | 112 | 1092 | 0.313 | 0.464 |

| Wiklund | 2004 | Sweden | Non-Hispanic | PB | TaqMan | 597 | 778 | 247 | 1622 | 0.392 | 0.804 | 297 | 384 | 115 | 796 | 0.386 | 0.611 |

| Nakazato | 2003 | Japan | Asian | HB | PCR | 69 | 32 | 0 | 101 | 0.158 | 0.059 | 71 | 26 | 8 | 105 | 0.200 | 0.020 |

| Rokman | 2002 | Finland | Non-Hispanic | HB | PCR | 88 | 106 | 39 | 233 | 0.395 | 0.464 | 69 | 84 | 23 | 176 | 0.369 | 0.745 |

| Wang | 2002 | USA | Caucasian | PB | PCR | 389 | 427 | 102 | 918 | 0.344 | 0.347 | 193 | 233 | 67 | 493 | 0.372 | 0.802 |

HWE: Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium of controls, HB: Hospital-based; PB: Population-based; MAF: Minor Allele Frequency.

Figure 2. A-allele frequencies for the RNASEL Arg462Gln polymorphism in the controls stratified by ethnicity.

Vertical line, A-allele frequency; Horizontal line, ethnicity type.

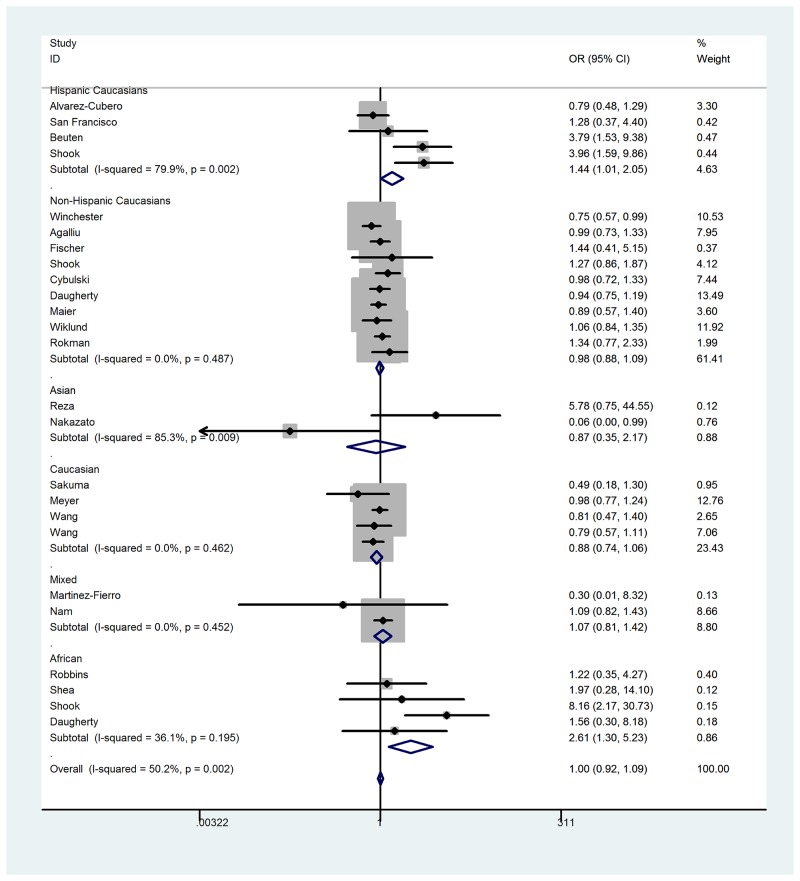

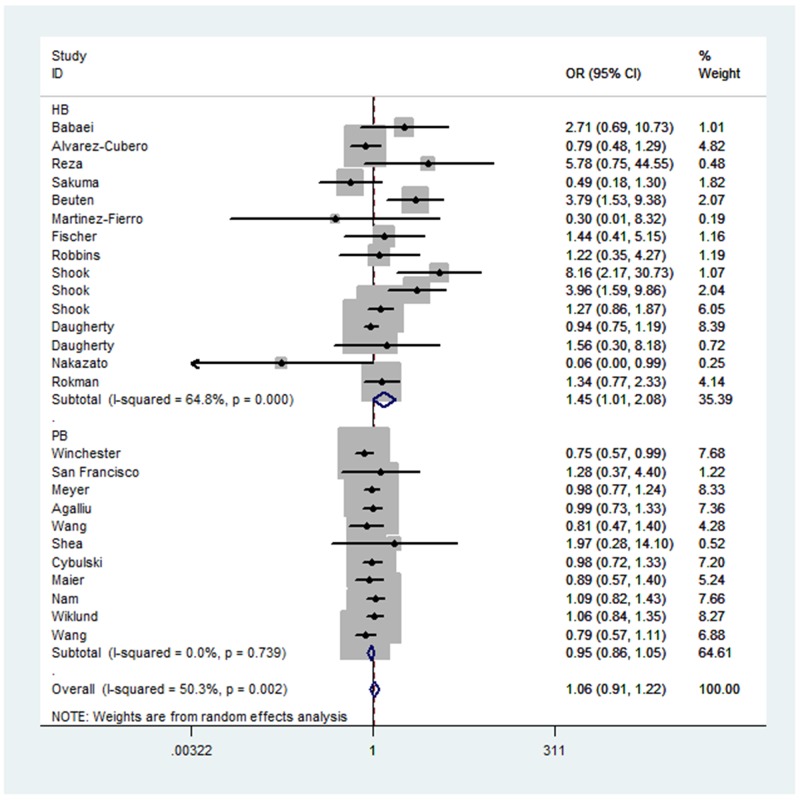

Quantitative synthesis

When all the eligible studies were pooled into the analysis (Table 2), no positive association was observed for allelic contrast (fixed-effects OR = 0.99, 95% CI = 0.95 - 1.03, Pheterogeneity = 0.004, P = 0.758, I2 = 47.9), homozygote comparison (fixed-effects OR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.91 - 1.09, Pheterogeneity = 0.001, P = 0.968, I2 = 54.2), heterozygote comparison (fixed-effects OR = 1.01, 95% CI = 0.92 - 1.10, Pheterogeneity = 0.029, P = 0.861, I2 = 37.6), the dominant genetic model (fixed-effects OR = 0.99, 95% CI = 0.93 - 1.04, Pheterogeneity = 0.361, P = 0.653, I2 = 7.0), and the recessive genetic model(fixed-effects OR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.92 – 1.09, Pheterogeneity = 0.002, P = 0.960, I2 = 50.3). However, in the subgroup analysis by ethnicity, obvious associations between the RNASEL Arg462Gln polymorphism and prostate cancer risk were observed in African descendants for homozygote comparison (fixed-effects OR = 2.59, 95% CI = 1.29 – 5.19, Pheterogeneity = 0.194, P = 0.008, I2 = 36.3), and the recessive genetic model (fixed-effects OR = 2.61, 95% CI = 1.30 – 5.23, Pheterogeneity = 0.195, P = 0.007, I2 = 36.1); and for Hispanic Caucasians for the recessive genetic model (fixed-effects OR = 1.44, 95% CI = 1.01 - 2.05, Pheterogeneity = 0.002, P = 0.046, I2 = 79.9), homozygote comparison (fixed-effects OR = 1.50, 95% CI = 1.02 – 2.20, Pheterogeneity = 0.001, P = 0.039, I2 = 82.3), and allelic contrast (fixed-effects OR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.00 - 1.39, Pheterogeneity = 0.010, P = 0.050, I2 = 73.5). No association was observed in Asian descendants for allelic contrast (fixed-effects OR = 1.30, 95% CI = 0.93 – 1.83, Pheterogeneity = 0.004, P = 0.126, I2 = 82.2), homozygote comparison (fixed-effects OR = 1.49, 95% CI = 0.70 – 3.17, Pheterogeneity = 0.013, P = 0.303, I2 = 76.9), and the recessive genetic model (fixed-effects OR = 1.23, 95% CI = 0.57 – 2.63, Pheterogeneity = 0.019, P = 0.600, I2 = 74.8); non-Hispanic Caucasians for allelic contrast (fixed-effects OR = 0.99, 95% CI = 0.94 – 1.04, Pheterogeneity = 0.856, P = 0.641, I2 = 0) homozygote comparison (fixed-effects OR = 0.98, 95% CI = 0.87 – 1.10, Pheterogeneity = 0.631, P = 0.701, I2 = 0), and the recessive genetic model (fixed-effects OR = 0.98, 95% CI = 0.88 – 1.09, Pheterogeneity = 0.487, P = 0.680, I2 = 0); and mixed descendants for allelic contrast (fixed-effects OR = 1.01, 95% CI = 0.89 – 1.15, Pheterogeneity = 0.381, P = 0.886, I2 = 0), homozygote comparison (fixed-effects OR = 1.06, 95% CI = 0.79 – 1.42, Pheterogeneity = 0.453, P = 0.692, I2 = 0), and the recessive genetic model (fixed-effects OR = 1.07, 95% CI = 0.81 – 1.42, Pheterogeneity = 0.452, P = 0.610, I2 = 0) (Figure 3). Furthermore, a significant association was also observed under the recessive genetic model (random-effects OR = 1.45, 95% CI = 1.01 – 2.08, Pheterogeneity < 0.001, P = 0.046, I2 = 64.8) between the RNASEL polymorphism and hospital-based controls (Figure 4). Interestingly, in a stratified analysis by the type of prostate cancer, a positive association was observed in familial prostate cancer for allelic contrast (fixed-effects OR = 0.89, 95% CI = 0.79 – 0.99, Pheterogeneity = 0.209, P = 0.028, I2 = 31.8) and homozygote comparison (fixed-effects OR = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.61 – 0.98, Pheterogeneity = 0.136, P = 0.037, I2 = 42.9), but not in sporadic prostate cancer for allelic contrast (fixed-effects OR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.94 – 1.10, Pheterogeneity = 0.774, P = 0.671, I2 = 0) and homozygote comparison (fixed-effects OR = 1.06, 95% CI = 0.89 – 1.27, Pheterogeneity = 0.640, P = 0.503, I2 = 0).

Table 2. Stratified analyses of the RNASEL Arg462Gln polymorphism on prostate cancer risk.

| Variables | Na | Cases/ | A-allele vs. G-allele | AA vs. GG | AA vs. GA+GG | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | OR(95%CI) | P | Pheterb | I2 | OR(95%CI) | P | Pheterb | I2 | OR(95%CI) | P | Pheterb | I2 | ||

| Total | 26 | 11522/10976 | 0.99(0.95-1.03 | 0.758 | 0.004 | 47.9 | 1.00(0.91-1.09 | 0.968 | 0.001 | 54.2 | 1.00(0.92-1.09 | 0.960 | 0.002 | 50.3 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||||

| Asian | 3 | 322/204 | 1.30(0.93-1.83 | 0.126 | 0.004 | 82.2 | 1.49(0.70-3.17 | 0.303 | 0.013 | 76.9 | 1.23(0.57-2.63 | 0.600 | 0.019 | 74.8 |

| African | 4 | 639/1273 | 1.12(0.91-1.37 | 0.281 | 0.056 | 60.3 | 2.59(1.29-5.19 | 0.008 | 0.194 | 36.3 | 2.61(1.30-5.23 | 0.007 | 0.195 | 36.1 |

| Caucasian | 4 | 2511/1996 | 0.92(0.84-1.00 | 0.058 | 0.371 | 4.4 | 0.84(0.70-1.02 | 0.081 | 0.319 | 14.6 | 0.88(0.74-1.06 | 0.173 | 0.462 | 0 |

| Hispanic Caucasians | 4 | 626/725 | 1.18(1.00-1.35 | 0.050 | 0.010 | 73.5 | 1.50(1.02-2.20 | 0.039 | 0.001 | 82.3 | 1.44(1.01-2.05 | 0.046 | 0.002 | 79.9 |

| Non-Hispanic Caucasians | 9 | 6417/5675 | 0.99(0.94-1.04 | 0.641 | 0.856 | 0 | 0.98(0.87-1.10 | 0.701 | 0.631 | 0 | 0.98(0.88-1.09 | 0.680 | 0.487 | 0 |

| Mixed | 2 | 1007/1103 | 1.01(0.89-1.15 | 0.886 | 0.381 | 0 | 1.06(0.79-1.42 | 0.692 | 0.453 | 0 | 1.07(0.81-1.42 | 0.610 | 0.452 | 0 |

| Source of control | ||||||||||||||

| Hospital-based | 15 | 3261/3848 | 1.06(0.98-1.14 | 0.120 | 0.001 | 63.1 | 1.47(0.99-2.20 | 0.059 | <0.001c | 67.9 | 1.45(1.01-2.08 | 0.046 | <0.001c | 64.8 |

| Population-based | 11 | 8261/7128 | 0.97(0.92-1.01 | 0.169 | 0.802 | 0 | 0.94(0.84-1.04 | 0.235 | 0.709 | 0 | 0.95(0.86-1.05 | 0.296 | 0.739 | 0 |

| Type of prostate cancer | ||||||||||||||

| Sporadic Pca | 6 | 2838/2934 | 1.02(0.94-1.10 | 0.671 | 0.774 | 0 | 1.06(0.89-1.27 | 0.503 | 0.640 | 0 | 1.07(0.91-1.26 | 0.441 | 0.679 | 0 |

| Familial Pca | 5 | 1313/1967 | 0.89(0.79-0.99 | 0.028 | 0.209 | 31.8 | 0.77(0.61-0.98 | 0.037 | 0.145 | 31.8 | 0.81(0.65-1.02 | 0.070 | 0.210 | 31.7 |

a Number of comparisons

b P value of Q-test for heterogeneity test(Pheter).

c Random effects model was performed when Pheter <0.001; otherwise, fixed effects model was used.

Figure 3. Forest plot of prostate cancer risk associated with RNASEL Arg462Gln polymorphism (recessive genetic model) in the stratified analysis by ethnicity.

The squares and horizontal lines correspond to the study-specific OR and 95% CI. The area of the squares reflects the weight (inverse of the variance). The diamond represents the summary OR and 95% CI. Separate details were summarized in Table 1.

Figure 4. Forest plot of prostate cancer risk associated with RNASEL Arg462Gln polymorphism (recessive genetic model of AA vs. GA + GG) by source of control.

The squares and horizontal lines correspond to the study-specific OR and 95% CI. The area of the squares reflects the weight (inverse of the variance). The diamond represents the summary OR and 95% CI.

Publication bias

The Egger’s test and Begg’s funnel plot were carried out to assess the publication bias of the literature. No obvious evidence of publication bias was found (A-allele vs. G-allele, t = 1.72, P = 0.098; AA vs. GG, t = 1.77, P = 0.089; GA vs. GG, t = 1.75, P = 0.094; AA + GA vs. AA, t = 1.23, P = 0.231; AA vs. GA + GG, t = 1.77, P = 0.090)

DISCUSSION

Published studies have shown evidence that RNASEL is a constitutively expressed latent endo-ribonuclease that mediates proapoptotic and antiviral activities of the IFN-inducible 2-5A system [7–9]. Mutation carriers in the RNASEL gene have loss of heterozygosity and are deficient in functional RNase L activity [33]. However, previous reports showing association between RNASEL polymorphism and prostate cancer susceptibility are contradictory. The general goal of this pooled analysis is to quantitatively analyze previous studies to understand the true relationship between RNASEL polymorphism and prostate cancer. Here, previous case-control studies with information between the RNASEL polymorphism and different types of Caucasians (Hispanic and Non-Hispanic) were included. As a result, some new findings were observed in our meta-analysis.

Our results indicated that the RNASEL Arg462Gln polymorphism may be associated with increased prostate cancer in African descendants (under homozygote comparison and the recessive genetic model) and Hispanic Caucasians (under allelic contrast, homozygote comparison, and the recessive genetic model), but not in Asian descendants and Non-Hispanic Caucasians. Furthermore, in a stratified analysis by source of control, the RNASEL Arg462Gln variant was found to increase prostate cancer risk in hospital-based studies (under the recessive genetic model). Nevertheless, several caveats limit generalization of these results. First, detailed information, such as age, prognostic parameters, environmental factors, and life-style, were not considered. Second, because different types of prostate cancer influence susceptibility, we tried to assess the effect of this polymorphism to different types of prostate cancer but not all data was compatible. Third, positive findings may be published faster than that those with “negative” results, which may result in a time-lag bias [34]. In addition, more environmental interactions, such as smoking habits, dietary factors, hormone exposure, toxins, and infectious agent, need to be added to the meta-analysis in the future.

Other limitations of the meta-analysis need to be addressed. First, while it is possible that the Arg462Gln polymorphism contributes to cancer, the combined effects of multiple environmental or genetic components predominate in the development of carcinoma, and may mask the effect of the polymorphism [35]. Second, the present analysis was based on unadjusted estimates. A more precise analysis with individual data is needed to evaluate combinatorial effects of the polymorphism [36]. Despite these concerns, the current analysis has some advantages compared with the individual studies. First, a substantial number of cases and controls were pooled from different studies, which significantly enhance the statistical power of this analysis. Second, the quality of case-control studies enrolled in our analysis was satisfactory based on the selection criteria. Third, no obvious publication bias was observed, which indicates that the conclusions were relatively stable and the publication bias might not influence the conclusions of the present meta-analysis.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis showed evidence that the RNASEL Arg462Gln polymorphism may contribute to the risk for developing prostate cancer in African descendants and Hispanic Caucasians, but not for other descendants. Further well-designed and prospective studies, particularly focused on gene-environment interactions, are warranted. These future studies should lead to a comprehensive understanding of the association between the RNASEL Arg462Gln polymorphism and prostate cancer risk.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy and identification of relevant studies

PubMed database searches were conducted using the following keywords: “ribonuclease L” or “RNASEL”, “prostate cancer”, and “polymorphism” (last search updated on March 01, 2017). References of the relevant articles and retrieved paper were also screened by hand search. Eligible studies had to meet all the following criteria: (a) used an unrelated case–control design; (b) contained information about available genotype frequency; (c) published in English; and (d) included the full-text article.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were collected on the genotype of rs486907 G/A (R462Q) according to prostate cancer. For each publication, the data extraction and methodological quality assessment were conducted by two of the investigators independently to ensure accuracy of the data. Disagreement was resolved by discussion between the two investigators. If they could not reach a consensus, the problem was discussed by all investigators to reach a consensus. The following parameters from each study were recorded: first author’s name, publication date, ethnicity, sources of cancer cases and controls, sample size in cases and controls, and the number of cases and controls with wild-type and variant allele, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Crude ORs with 95% CIs were utilized to evaluate the strength of association between the RNASEL polymorphism and prostate cancer based on genotype frequencies in cases and controls. Five genetic contrasts were used to assess the association: allelic contrast (A-allele vs. G-allele), homozygote comparison (AA vs. GG), heterozygote comparison (GA vs. GG), the dominant genetic model (AA + GA vs. GG), and the recessive genetic model (AA vs. GA + GG). Subgroup analysis was stratified by ethnicity, source of control (hospital-based and population-based), and smoking exposure. We utilized the random effects model and fixed effects model to calculate the pooled OR. Heterogeneity assumption was evaluated by a chi-square-based Q test. P value lower than 0.001 for the Q-test indicates lack of heterogeneity among studies, hence the pooled OR was utilized by the random effects model (DerSimoniane and Laird method [37] or by the fixed-effects model (the Mantel-Haenszel method [38]). HWE was checked by the Pearson chi-square test for goodness of fit. A Z-test was used to evaluate statistical significance of the summary OR, and P value of ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. We also utilized the I2 statistic to test heterogeneity, with I2 >75%, 25–75%, and < 25% to represent high, moderate, and low degree of inconsistency, respectively [39]. We determined significance of the intercept by t-test suggested by Egger (P < 0.01 was considered representative of significant publication bias) [40]. All statistical analyses were performed with STATA version 11.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX), utilizing two-sided P values.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

FUNDING

This study was supported by the foundation of High-Level Medical Talents Training Project (No.2016CZBJ035) and Changzhou 23rd Science and Technology Project (International Science and Technology Collaboration), Project No. CZ20160017.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Marzo AM, Platz EA, Sutcliffe S, Xu J, Gronberg H, Drake CG, Nakai Y, Isaacs WB, Nelson WG. Inflammation in prostate carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:256–269. doi: 10.1038/nrc2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vral A, Magri V, Montanari E, Gazzano G, Gourvas V, Marras E, Perletti G. Topographic and quantitative relationship between prostate inflammation, proliferative inflammatory atrophy and low-grade prostate intraepithelial neoplasia: a biopsy study in chronic prostatitis patients. Int J Oncol. 2012;41:1950–1958. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palapattu GS, Sutcliffe S, Bastian PJ, Platz EA, De Marzo AM, Isaacs WB, Nelson WG. Prostate carcinogenesis and inflammation: emerging insights. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1170–1181. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thapa D, Ghosh R. Chronic inflammatory mediators enhance prostate cancer development and progression. Biochem Pharmacol. 2015;94:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinberg GD, Carter BS, Beaty TH, Childs B, Walsh PC. Family history and the risk of prostate cancer. Prostate. 1990;17:337–347. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990170409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silverman RH. A scientific journey through the 2-5A/RNase L system. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2007;18:381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Roy F, Salehzada T, Bisbal C, Dougherty JP, Peltz SW. A newly discovered function for RNase L in regulating translation termination. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:505–512. doi: 10.1038/nsmb944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiang Y, Wang Z, Murakami J, Plummer S, Klein EA, Carpten JD, Trent JM, Isaacs WB, Casey G, Silverman RH. Effects of RNase L mutations associated with prostate cancer on apoptosis induced by 2,5-oligoadenylates. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6795–6801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winchester DA, Till C, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, Santella RM, Johnson-Pais TL, Leach RJ, Xu J, Zheng SL, Thompson IM, Lucia MS, Lippmann SM, Parnes HL, et al. Variation in genes involved in the immune response and prostate cancer risk in the placebo arm of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. Prostate. 2015;75:1403–1418. doi: 10.1002/pros.23021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alvarez-Cubero MJ, Martinez-Gonzalez LJ, Saiz M, Carmona-Saez P, Alvarez JC, Pascual-Geler M, Lorente JA, Cozar JM. Prognostic role of genetic biomarkers in clinical progression of prostate cancer. Exp Mol Med. 2015;47:e176. doi: 10.1038/emm.2015.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.San Francisco IF, Rojas PA, Torres-Estay V, Smalley S, Cerda-Infante J, Montecinos VP, Hurtado C, Godoy AS. Association of RNASEL and 8q24 variants with the presence and aggressiveness of hereditary and sporadic prostate cancer in a Hispanic population. J Cell Mol Med. 2014;18:125–133. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakuma T, Hué S, Squillace KA, Tonne JM, Blackburn PR, Ohmine S, Thatava T, Towers GJ, Ikeda Y. No evidence of XMRV in prostate cancer cohorts in the Midwestern United States. Retrovirology. 2011;8:23. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-8-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer MS, Penney KL, Stark JR, Schumacher FR, Sesso HD, Loda M, Fiorentino M, Finn S, Flavin RJ, Kurth T, Price AL, Giovannucci EL, Fall K, et al. Genetic variation in RNASEL associated with prostate cancer risk and progression. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1597–1603. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beuten J, Gelfond JA, Franke JL, Shook S, Johnson-Pais TL, Thompson IM, Leach RJ. Single and multivariate associations of MSR1, ELAC2, and RNASEL with prostate cancer in an ethnic diverse cohort of men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:588–599. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agalliu I, Leanza SM, Smith L, Trent JM, Carpten JD, Bailey-Wilson JE, Burk RD. Contribution of HPC1 (RNASEL) and HPCX variants to prostate cancer in a founder population. Prostate. 2010;70:1716–1727. doi: 10.1002/pros.21207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang MH, Helzlsouer KJ, Smith MW, Hoffman-Bolton JA, Clipp SL, Grinberg V, De Marzo AM, Isaacs WB, Drake CG, Shugart YY, Platz EA. Association of IL10 and other immune response- and obesity-related genes with prostate cancer in CLUE II. Prostate. 2009;69:874–885. doi: 10.1002/pros.20933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robbins CM, Hernandez W, Ahaghotu C, Bennett J, Hoke G, Mason T, Pettaway CA, Vijayakumar S, Weinrich S, Furbert-Harris P, Dunston G, Powell IJ, Carpten JD, Kittles RA. Association of HPC2/ELAC2 and RNASEL non-synonymous variants with prostate cancer risk in African American familial and sporadic cases. Prostate. 2008;68:1790–1797. doi: 10.1002/pros.20841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shea PR, Ishwad CS, Bunker CH, Patrick AL, Kuller LH, Ferrell RE. RNASEL and RNASEL-inhibitor variation and prostate cancer risk in Afro-Caribbeans. Prostate. 2008;68:354–359. doi: 10.1002/pros.20687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daugherty SE, Hayes RB, Yeager M, Andriole GL, Chatterjee N, Huang WY, Isaacs WB, Platz EA. RNASEL Arg462Gln polymorphism and prostate cancer in PLCO. Prostate. 2007;67:849–854. doi: 10.1002/pros.20537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiklund F, Jonsson BA, Brookes AJ, Strömqvist L, Adolfsson J, Emanuelsson M, Adami HO, Augustsson-Bälter K, Grönberg H. Genetic analysis of the RNASEL gene in hereditary, familial, and sporadic prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7150–7156. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakazato H, Suzuki K, Matsui H, Ohtake N, Nakata S, Yamanaka H. Role of genetic polymorphisms of the RNASEL gene on familial prostate cancer risk in a Japanese population. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:691–696. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rökman A, Ikonen T, Seppälä EH, Nupponen N, Autio V, Mononen N, Bailey-Wilson J, Trent J, Carpten J, Matikainen MP, Koivisto PA, Tammela TL, Kallioniemi OP, Schleutker J. Germline alterations of the RNASEL gene, a candidate HPC1 gene at 1q25, in patients and families with prostate cancer. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:1299–1304. doi: 10.1086/340450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang L, McDonnell SK, Elkins DA, Slager SL, Christensen E, Marks AF, Cunningham JM, Peterson BJ, Jacobsen SJ, Cerhan JR, Blute ML, Schaid DJ, Thibodeau SN. Analysis of the RNASEL gene in familial and sporadic prostate cancer. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:116–123. doi: 10.1086/341281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maier C, Haeusler J, Herkommer K, Vesovic Z, Hoegel J, Vogel W, Paiss T. Mutation screening and association study of RNASEL as a prostate cancer susceptibility gene. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1159–1164. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nam RK, Zhang WW, Jewett MA, Trachtenberg J, Klotz LH, Emami M, Sugar L, Sweet J, Toi A, Narod SA. The use of genetic markers to determine risk for prostate cancer at prostate biopsy. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8391–8397. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cybulski C, Wokołorczyk D, Jakubowska A, Gliniewicz B, Sikorski A, Huzarski T, Debniak T, Narod SA, Lubiński J. DNA variation in MSR1, RNASEL and E-cadherin genes and prostate cancer in Poland. Urol Int. 2007;79:44–49. doi: 10.1159/000102913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinez-Fierro ML, Leach RJ, Gomez-Guerra LS, Garza-Guajardo R, Johnson-Pais T, Beuten J, Morales-Rodriguez IB, Hernandez-Ordoñez MA, Calderon-Cardenas G, Ortiz-Lopez R, Rivas-Estilla AM, Ancer-Rodriguez J, Rojas-Martinez A. Identification of viral infections in the prostate and evaluation of their association with cancer. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:326. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reza MA, Fahimeh G, Reza MH. Evaluation of xenotropic murine leukemia virus and its R426Q polymorphism in patients with prostate cancer in Kerman, southeast of Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:3669–3673. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.8.3669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fischer N, Hellwinkel O, Schulz C, Chun FK, Huland H, Aepfelbacher M, Schlomm T. Prevalence of human gammaretrovirus XMRV in sporadic prostate cancer. J Clin Virol. 2008;43:277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shook SJ, Beuten J, Torkko KC, Johnson-Pais TL, Troyer DA, Thompson IM, Leach RJ. Association of RNASEL variants with prostate cancer risk in Hispanic Caucasians and African Americans. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5959–5964. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Babaei F, Ahmadi A, Rezaei F, Jalilvand S, Ghavami N, Mahmoudi M, Abiri R, Kondori N, Nategh R, Mokhtari Azad T. Xenotropic Murine Leukemia Virus-Related Virus RNase L R462Q Variants in Iranian Patients With Sporadic Prostate Cancer. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2015;17:e19439. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.19439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carpten J, Nupponen N, Isaacs S, Sood R, Robbins C, Xu J, Faruque M, Moses T, Ewing C, Gillanders E, Hu P, Bujnovszky P, Makalowska I, et al. Germline mutations in the ribonuclease L gene in families showing linkage with HPC1. Nat Genet. 2002;30:181–184. doi: 10.1038/ng823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ioannidis JP. Effect of the statistical significance of results on the time to completion and publication of randomized efficacy trials. JAMA. 1998;279:281–286. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.4.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei Q, Cheng L, Amos CI, Wang LE, Guo Z, Hong WK, Spitz MR. Repair of tobacco carcinogen-induced DNA adducts and lung cancer risk: a molecular epidemiologic study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1764–1772. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.21.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirschhorn JN, Lohmueller K, Byrne E. A comprehensive review of genetic association studies. Genet Med. 2002;4:45–61. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22:719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]