Abstract

Background

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) cure rates have been similar in patients with and without HIV co-infection; however, in the ION-4 study, black patients treated with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir were significantly less likely to achieve cure (90%) compared to non-black patients (99%). There are limited real world data on the effectiveness of oral direct acting antivirals (DAAs) in predominantly minority HIV/HCV co-infected populations.

Methods

We analyzed HCV treatment outcomes among 255 HCV co-infected patients initiating DAAs between February 2014 and March 2016 in an urban clinic in Baltimore, Maryland. To facilitate adherence, patients received standardized HIV nurse/pharmacist support which included nurse visits and telephone calls.

Results

The median age was 43 years, 88% were black, 73% male, 69% had a history of injection drug use, 45% a history of hazardous alcohol use and 57% a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis. Median CD4 count was 577 (IQR 397–820) cells/mm3; most (97%) were on antiretroviral therapy, had HIV RNA <20 copies/ml (87%) and were infected with HCV genotype 1 (98%). Over 60% had significant fibrosis [FIB4 score 1.45–3.25 (44%) and >3.25 (17%, cirrhosis)] and 30% were HCV treatment experienced. The majority of patients received ledipasvir/sofosbuvir with or without ribavirin (91%) and were treated for 12 weeks. Overall, the sustained virologic response rate was 97% (95% confidence interval [CI] 93–98) and did not vary by race (black, 96% [95% CI 93–98]; Non-black 97%, [95% CI 83–99]), history of injection drug use, alcohol use or psychiatric diagnosis.

Conclusion

HCV treatment was highly effective among HIV-infected patients who received care within an integrated nurse/pharmacist adherence support program. These results suggest that race and psychosocial comorbidity may not be barriers to HCV elimination.

Keywords: co-infection, minority populations, treatment support, direct acting antivirals, effectiveness

Introduction

Approximately 30% of HIV infected individuals in the United States are co-infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) (1). The prevalence of HCV/HIV coinfection however varies globally ranging from 6% overall to over 80% in HIV infected people who inject drugs (2). HCV/HIV co-infection is associated with accelerated liver disease progression to end stage liver disease and liver related mortality and is a leading cause of death among HIV-infected persons in the era of effective antiretroviral therapy (3, 4). Successful HCV treatment leading to viral cure is associated with reductions in liver related morbidity and mortality in HIV-infected individuals. In clinical trials, HIV-infected persons treated with interferon-free, direct acting antiviral (DAA) regimens have had high rates of HCV cure similar to the rates observed in persons with HCV monoinfection (6–9). However, some real world cohorts have reported lower HCV cure rates in HIV-infected persons compared to HIV uninfected individuals in the oral DAA era (10, 11) highlighting the need for a better understanding of factors that may negatively impact HCV treatment outcomes among individuals infected with HIV and a need for interventions to address these factors. Additionally, trial data and limited real world experience also suggest that HCV treatment may be less effective in certain subpopulations of persons with HIV co-infection (6, 12).

In particular, African-Americans bear a disproportionate burden of both HIV and HCV infection. Disparities in HCV treatment outcomes have historically been widened by lower rates of spontaneous and treatment-related HCV clearance related, in part, to the higher preponderance of unfavorable IL28B/IFNL4 genotypes in this population which greatly impaired the response to interferon-based HCV treatments (13, 14). In contrast, treatment with oral DAAs, which target the hepatitis C virus, are markedly less impacted by host genetic polymorphisms leading to high HCV cure rates in persons with and without the unfavorable IL28B/IFNL4 genotypes including African-Americans (15). However, in some clinical trial and real world settings, HCV cure rates with oral HCV DAAs have been lower in black compared to non-black patients. For example, in the ION-4 study, HIV-infected black patients treated with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (LDV/SOF) for 12 weeks were significantly less likely to achieve cure (90%) compared to non-black patients (99%) and in the Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Case Registry for HCV, African-American race was independently associated with a 30% decreased likelihood of SVR following treatment with LDV/SOF (6, 12).

In this regard, there are limited real world data on the effectiveness of oral DAAs in predominantly minority HIV/HCV co-infected populations and on the potential for clinically significant drug interactions between DAAs and antiretrovirals used to treat HIV. We evaluated the effectiveness and safety of DAA therapy among the first 255 HIV/HCV co-infected patients consecutively treated in an inner city, predominantly black HIV clinical practice.

Methods

Study Population

This analysis included data collected from 255 HIV/HCV co-infected adults who received medical care in the Johns Hopkins HIV clinical practice and had previously enrolled in ongoing prospective observational cohort studies of HIV and HIV/HCV clinical outcomes. The cohort has previously been described (16). All such persons who initiated oral DAA therapy at the contiguous Johns Hopkins HCV clinical practice between February 2014 and March 2016 were included in this analysis. The Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine approved the research study and all participants provided written informed consent.

Setting

The Johns Hopkins HIV and HCV clinical practice provides medical care to persons infected with HIV, HCV or both viruses in a predominantly black inner city population from the Baltimore metropolitan region. The Johns Hopkins HCV care model provides comprehensive HCV care within the HIV care infrastructure. HIV care is provided by clinical care teams including a clinician, nurse and social worker to ensure continuity of care for each individual. Patients are referred to HCV providers who assess HCV disease stage and the need for DAAs. Pharmacists and providers also assess the potential for drug interactions between intended DAAs, antiretroviral treatment (ART) and other medications. If changes to the ART regimens are recommended, changes to the patient’s HIV treatment are coordinated with the individual’s HIV care team prior to HCV treatment. Prescriptions for DAAs are processed by a trained team of pharmacists and technicians at the Johns Hopkins Outpatient Pharmacy who facilitate prior authorization, re-assess potential drug interactions and longitudinally track all patients during treatment to ensure that monthly medication refills are delivered seamlessly.

During HCV treatment, all patients follow an individualized HCV treatment plan to facilitate adherence. The intensity of support provided is based on the assessment of the patient’s HIV and HCV care team who assign one of three color-coded levels of treatment support: Green level patients receive minimal intervention and are permitted to initiate HCV treatment on their own; Yellow level patients receive moderate intensity support including a mandated nurse visit to initiate DAAs with on-site delivery of the first DAA prescription; and Red level patients receive significant support including a mandatory nurse visit to initiate DAAs with on-site hand off of the first month DAA prescription followed by frequent (up to weekly) visits with their nurse, pharmacist or HCV provider during the course of HCV therapy. Patients at all 3 levels of support can also attend the pharmacotherapy clinic for medication counseling; at least one pharmacotherapy clinic assessment is strongly recommended for patients with chronic kidney disease, liver transplant, those prescribed more than 10 medications or if there was a drug interaction that required a change in drug therapy.

For most Yellow and Red level patients, the DAA initiation visit is conducted by their long-standing HIV nurse who provides adherence counseling and a customized calendar with dates for DAA refills, safety blood draws, and nurse and clinician visits. Telephone contact occurs within one week of treatment initiation for all patients to assess for any concerns including side effects and adherence. Subsequent nurse contacts include a monthly reminder for DAA refills, clinical care visits, and phlebotomy for HCV RNA, complete blood count (when ribavirin is prescribed) and chemistries including testing for levels of alanine aminotransferase and creatinine. All patients are scheduled to see HCV providers at DAA treatment week 4 or 6, end of treatment (EOT) and post-treatment week 12. Persons who fail to complete scheduled HCV treatment milestones are referred to a peer navigator for intensive follow-up including home visits.

Data Collection

The primary outcome of interest was sustained virologic response (SVR) defined as an undetectable HCV RNA 12 weeks or more after EOT. EOT was defined as the last day of therapy based on start dates from pharmacy data and confirmed with recorded stop dates in the electronic medical record. Non-SVR was defined as HCV RNA detected after EOT using HCV RNA assays with a lower limit of quantification of 15 IU/ml.

Patient demographic and other baseline characteristics were determined at HCV treatment initiation and included age, sex, race, height, weight, ART regimen, CD4 cell count, HIV and HCV RNA level, history of health-related behaviors (e.g. drug and alcohol use), history of mental health diagnoses and liver staging. Prescribed medications, diagnoses and laboratory tests were abstracted from the electronic medical record. Additional data on HIV treatment adherence, illicit drug and alcohol use were collected through Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview (ACASI) Software and were available on a subset (70%) of the population within 12 months of and prior to HCV treatment initiation. Liver disease staging was assessed by liver elastography (FibroScan, EchoSens, Paris France) or FIB-4 (calculated from the patient’s age, AST and AST levels and platelet count). Fasting liver stiffness measurements > 12.5 KPA by elastography or FIB-4 score > 3.25 were considered evidence of cirrhosis (17, 18). Hazardous alcohol use was defined as > 4 drinks on any day or >14 drinks per week for men and >3 drinks on any day or > 7 drinks per week for women or an alcohol use disorders identification test C (AUDIT-C) score of 4 or above (19). Active illicit drug or alcohol use was defined as use in the three months preceding HCV treatment.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population with respect to demographics and risk behaviors. Proportions were compared using Chi-square tests to assess factors associated with HCV SVR. P values <0.05 were considered to be significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4.

Results

A total of 255 HIV/HCV co-infected patients previously enrolled in the Johns Hopkins HIV or HIV/HCV clinical cohort studies initiated oral DAAs between February 2014 and March 2016. The majority of individuals were male (73%), black (88%) and had a median age of 43 years [interquartile range (IQR) 38–50]. The predominant mode of HIV transmission was injection drug use (69%). The majority reported comorbid diagnoses including a psychiatric diagnosis (57%), history of illicit drug use (73%) and tobacco use (82%). Most were infected with HCV genotype 1a (76%) and had evidence of advanced liver disease (62%) based on a FIB-4 score of 1.45 or greater. Seventeen had evidence of cirrhosis based on a FIB 4 score of >3.25. Approximately, 30% had been previously treated for hepatitis C with peginterferon-based therapies (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of HIV/HCV infected patients receiving oral DAA HCV treatment

| Characteristic at HCV treatment initiation | N=255 |

|---|---|

| Age, median, years (IQR) | 43 (38, 50) |

| Sex, n, % male | 187 (73.3) |

| Race, n, % | |

| Black | 223 (87.5) |

| White | 28 (11.0) |

| Median body mass index (IQR)# | 27.1 (23.3, 31.0) |

| * HIV transmission risk factor, n, % | |

| Injection drug use | 175 (68.6) |

| Men who have sex with men | 42 (16.5) |

| Heterosexual | 130 (51.0) |

| History of drug use, n, % | 187 (73.3) |

| History of hazardous alcohol use, n, % | 114 (44.7) |

| ‡ Active illicit drug or hazardous alcohol use | 46 (26.3) |

| Ongoing tobacco use, n, % | 208 (81.6) |

| Any prior psychiatric diagnosis, n, % | 146 (57.3) |

| History of diagnosed depression, n, % | 91 (35.7) |

| Prior HCV treatment experience | 76 (29.8) |

| CD4 T cell count, median cells/mm3 (IQR) | 577 (397, 820) |

| On antiretroviral therapy | 247 (96.9) |

| HIV RNA, ≤20 copies/ml | 214 (86.6) |

| HIV RNA >20 copies/ml | 33 (13.4) |

| Not on antiretroviral therapy | 325 (20–1785) |

| HIV RNA median, IQR | 8 (3.1) |

| Change in antiretroviral prior to HCV treatment due to drug interaction | 325 (20–1785) |

| Yes | 78 (30.6) |

| No | 177 (69.4) |

| HCV Genotype, n, % | |

| 1a | 193 (75.7) |

| 1b | 56 (22.0) |

| other | 5 (2.0) |

| Liver elastography (FibroScan) score, median (IQR)£ | 9.2 (6.6, 14.3) |

| <8.8 | 107 (47.4) |

| >=8.8 – <12.5 | 52 (23.0) |

| >=12.5 | 67 (29.7) |

| FIB-4 score n, % | |

| <1.45 | 98 (38.4) |

| 1.45–3.24 | 113 (44.3) |

| >3.25 | 44 (17.3) |

| Albumin mg/dL, median IQR | 4.2 (3.9, 4.4) |

| Hemoglobin mg/dL, median IQR | 13.4 (12.1, 14.4) |

| Platelet x 109/mL, median IQR | 183 (138, 220) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase level, units/L, median IQR | 44 (34, 62) |

| Alanine aminotransferase level, units/L, median IQR | 39 (27, 60) |

| Median Creatinine Clearance(IQR)# | 97.0 (IQR: 77.4, 117.0) |

HCV-hepatitis C virus; DAA- direct acting agent.

Patients may have more than one transmission risk factor

Data only available in 179 of 255 (70%) patients. Active use defined as self-reported use in the preceding 3 months. Hazardous alcohol use defined as > 4 drinks on any day or >14 drinks per week.

Fibroscan data not available on 29 patients

Data not available for 10 patients

Additional behavioral data collected prior to and within one year of HCV treatment by ACASI was available for 179 patients (70%). Approximately 89% of patients reported very good to excellent adherence to ART with 86% denying any missed doses in the preceding week. Active illicit drug use varied by drug type with 14%, 8%, and 6% reporting marijuana, cocaine and heroin use, respectively. Active alcohol use was reported in 30% and current hazardous levels of alcohol use reported in 7% of patients based on an AUDIT-C score of 4 or above.

The majority (97%) were on antiretroviral therapy and had HIV RNA less than 20 copies/ml (87%); the median CD4 cell count was 577 (IQR 397–820) cells/mm3. Eight patients were not taking antiretrovirals. Changes in ART regimen prior to HCV treatment occurred in 78 (31%) of patients. Most changes occurred in patients who were on a ritonavir-boosted HIV-1 protease inhibitor and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and involved substitution of a protease inhibitor by the HIV-1 integrase inhibitor dolutegravir (18). Of 54 patients receiving efavirenz, antiretroviral therapy was switched from efavirenz to another agent in 15 prior to HCV therapy initiation. Among those prescribed ART, 127 (51%) were prescribed an HIV-1 integrase inhibitor (raltegravir, dolutegravir or elvitegravir) and 39 (16%) prescribed efavirenz. TDF was part of the antiretroviral regimen for 78 (32%) patients; of whom, 11 received TDF in combination with a ritonavir-boosted HIV-1 protease inhibitor (Table 2).

Table 2.

Antiretroviral regimens received by patients during HCV therapy

| Antiretroviral therapy regimen | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| TDF + Integrase inhibitor | |

| Raltegravir | 11 (4.3) |

| Dolutegravir | 19 (7.5) |

| Elvitegravir | 2 (<1) |

| No TDF + Integrase inhibitor | |

| Dolutegravir | 65 (25.4) |

| Raltegravir | 30 (11.7) |

| TDF + Boosted protease inhibitor | |

| Atazanavir/ritonavir | 5 (1.9) |

| Darunavir/ritonavir | 6 (2.3) |

| No TDF + Boosted protease inhibitor | |

| Atazanavir/ritonavir | 15(5.8) |

| Darunavir/ritonavir | 42 (16.4) |

| TDF + Nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor | |

| Efavirenz | 29 (11.4) |

| Rilpivirine | 4 (1.6) |

| Other NNRTI | 2 (<1) |

| No TDF + Nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor | |

| Efavirenz | 10 (3.9) |

| Etravirine | 19 (7.5) |

| Rilpivirine | 7 (2.7) |

Antiretroviral therapy categories are not mutually exclusive

Of 255 patients who initiated DAAs, the majority received ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (LDV/SOF) (231 patients, 91%); including 229 without and 2 with ribavirin. Twelve patients received simeprevir plus sofosbuvir (SIM + SOF, 5%) including 3 with and 9 without ribavirin. A minority of patients received sofosbuvir plus ribavirin (SOF + RBV; 6 patients; 2%) or paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir plus dasabuvir (ProD) plus ribavirin (5 patients, 2%).

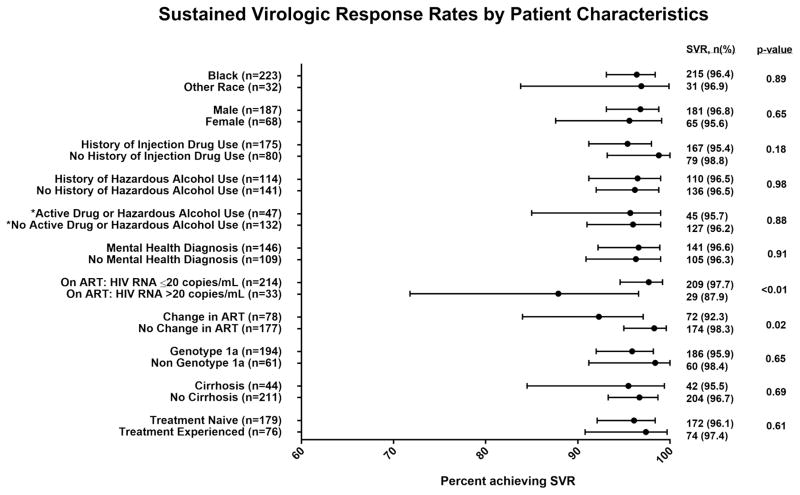

HCV cure rates

Two hundred and forty-six (96.5%) of 255 patients achieved SVR. Among patients receiving LDV/SOF with or without ribavirin, SVR in patients receiving therapy for 12 weeks (n=185) and 24 weeks (n=36) was 97.3% and 100% respectively. The SVR rate among patients who completed the prescribed course of LDV/SOF (n=221) was 96.8% whereas among 10 patients who had less than 12 weeks, the SVR rate was 70%. All patients who received SIM +SOF ± RBV (n=12), ProD + RBV (n=5) and SOF + RBV (n=6) achieved SVR. SVR did not vary by race, sex, CD4 cell count, HCV genotype/subtype, cirrhosis status or prior HCV treatment experience (Figure 1). SVR did not vary significantly according to the type of ART regimen. Among 34 individuals infected with genotype 1a who received efavirenz and ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, SVR overall was 97.1% and did not vary significantly by black or non- black race (25/26 (96.1%) versus 8/8 (100%) p=0.6). However, patients who had complete HIV suppression (HIV RNA < 20 copies/ml) were more likely to achieved SVR than those not fully suppressed (SVR 97.7% versus 87.9%; p=0.01) (Figure 1). Additionally, patients who switched their ART regimen prior to HCV treatment had a lower SVR rate compared to those who remained on the same ART (SVR 92.3% versus 98.3%; p=0.02). SVR rates were also similar in persons with a history of injection drug use, hazardous alcohol use or psychiatric comorbid disease compared to those without these conditions. Information on drug and alcohol use was assessed by ACASI in 179 persons a median of 94 (IQR: 44, 168; range: 0, 362) days prior to HCV treatment. Active illicit drug use (excluding marijuana and including cocaine, amphetamines, heroin, injection drug, or prescription opioid misuse) was reported in 12% of participants. There was no significant difference by drug use: 97% (95% CI: 93, 99) among those who did not report drug use (n=158); 90% (95% CI: 70, 99) among those who did (n=21); p=0.16. When marijuana was included, the proportion of individuals reporting drug use in the preceding 3 months increased to 22%. There was no significant difference by drug including marijuana use: 96% (95% CI: 92, 99) among those who did not report drug use (n=139); 95% (95% CI: 83, 99) among those who did (n=40); p=0.69. Additionally, 7% of individuals reported hazardous levels of alcohol use. There was no significant difference in SVR by alcohol use: 96% (95% CI: 92, 98) among those who did not report hazardous alcohol use (n=166); 100% (95% CI: 75, 100) among those who reported hazardous alcohol use (n=13); p=0.45. Overall, 26% reported either drug or hazardous alcohol use in the preceding 3 months. There was no significant difference by drug or alcohol use: 96% (95% CI: 91, 99) among those who did not report either alcohol or drug use (n=133); 96% (95% CI: 85, 99) among those who reported alcohol or drug use (n=46); p=0.88.

Figure 1.

Failure to achieve SVR

Overall, only 9 patients failed to achieve SVR; all had been prescribed 12 weeks of LDV/SOF. Among these 9 patients, 5 experienced virologic relapse after completion of the full treatment course, 3 discontinued LDV/SOF prematurely and 1 patient died of unknown causes after treatment week 3 (Table 4). Eight of these patients were of black race, 6 were male, 5 had evidence of cirrhosis and 1 was treatment experienced. The failure to achieve SVR was attributed to non-adherence/premature discontinuation in 4 patients, an inadequate HCV treatment course of 12 weeks of LDV/SOF in 2 patients (one patient with prior treatment experience and cirrhosis and another patient with decompensated cirrhosis; both patients should have received ribavirin or had treatment extended to 24 weeks according to the HCV treatment guidance(20)). Among the 3 other patients who did not achieve SVR, the treatment course was adequate but potentially complicated by concomitant proton pump inhibitor use (n=2) and recurrent diarrhea including an admission for recurrent clostridium difficile diarrhea (n=1). Among the 5 patients who experienced HCV relapse, all 4 who had resistance testing at the time of HCV recurrence had resistance associated substitutions (RASs) related to the NS5A inhibitor ledipasvir. One patient had the sofosbuvir RAS, L159; none had the RAS at NS5B position 282 (S282T) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Characteristics of nine patients in whom HCV cure was not achieved following prescription of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir

| No | Age | Race | Sex | Comorbidities | HIV RNA (copies/mL) and CD4 Count/mm3 |

HCV baseline viral load IU/ml |

HCV genotype |

HCV Treatment experienced (Yes/No) |

Cirrhosis (Yes/No) |

HCV treatment duration |

HCV Resistance at failure |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 53 | AA | M | Injection drug use | 301 50 |

14700000 | 1a | No | No | 2 weeks | Not tested | Self-discontinuation due to dizziness and lightheadedness |

| 2 | 45 | AA | M | Recurrent clostridium difficile colitis | 173 <20 |

3460000 | 1a | No | Yes | 12 weeks | L31M | |

| 3 | 31 | AA | M | Depression; alcohol dependence | 110 24 |

8530000 | 1a | No | Yes | 4 weeks | H580, Q80K | Non-adherence due to incarceration |

| 4 | 64 | AA | F | Depression; GERD | 440 <20 |

14400000 | 1a | No | No | 12 weeks | L159F, C316W, L31M Y93H | Concomitant proton pump inhibitor use |

| 5 | 66 | AA | M | New HCC diagnosis | 637 <20 |

15000000 | 1a | Yes IFN+RBV 2006 | Yes | 12 weeks | Not tested | Premature discontinuation in setting of new HCC diagnosis |

| 6 | 44 | W | M | Decompensated cirrhosis | 248 <20 |

3949540 | 1a | No | Yes | 12 weeks | H58P | Inadequate HCV treatment |

| 7 | 55 | AA | M | Diabetes | 713 50 |

3532070 | 1b | No | No | 12 weeks | Y93H, Q54Y | Efavirenz and proton pump inhibitor use |

| 8 | 57 | AA | F | Diabetes, recent IDU, off opioid agonist therapy | 597 20 |

7360000 | 1a | No | Yes | 6weeks | Not tested | Non-adherence |

| 9 | 48 | AA | F | Depression | 482 <20 |

334000 | 1a | No | No | 3 week | N/A | Death in week 3 Cause unknown |

HCV: Hepatitis C Virus, AA: African American, W: White, M: Male F: Female, IDU: Injection drug use, GERD: Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease, HCC: Hepatocellular Cancer, IFN: Interferon, RBV: Ribavirin

Safety

One patient with pre-existing stage 5 chronic kidney disease [serum creatinine 3.2 and estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 24 ml/min/1.73 square meter] and biopsy proven focal segmental glomerulosclerosis experienced an increase in creatinine to 4.2 after 6 weeks of LDV/SOF and, at treatment week 8 was switched to PrOD to complete a 12 week course of HCV therapy. At the end of treatment, the patient’s serum creatinine was 5.1 and estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was 14 ml/min/1.73 square meter and remained impaired through post-treatment follow-up; the patient subsequently initiated hemodialysis. Other than this patient, there were no other significant changes in renal function assessed by serum creatinine elevations observed over the course of HCV therapy, including among patients taking concurrent LDV and TDF. The mean change in creatinine was an increase of approximately 0.1–0.2 mg/dl in patients on all ART regimens including those receiving tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in combination with a ritonavir boosted HIV-1 protease inhibitor (Table 3).

Table 3.

Changes in creatinine by ART regimen pre and post HCV treatment in patients treated with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir

| HAART Regimen | N | Mean | Median (IQR) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not on ART | 4 | −0.05 | −0.1 (−0.2, 0.1) | −0.2, 0.1 |

| TDF + Integrase inhibitor | 23 | 0.09 | 0.1 (0, 0.2) | −0.2, 0.6 |

| No TDF + Integrase inhibitor | 72 | 0.09 | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.2) | −0.4, 0.9 |

| TDF + Boosted Protease inhibitor | 3 | 0.13 | 0.1 (0, 0.3) | 0, 0.3 |

| NO TDF + Boosted Protease inhibitor | 45 | 0.10 | 0.1 (0, 0.2) | −0.4, 0.9 |

| TDF + NNRTI | 25 | 0.02 | 0 (0, 0.1) | −0.3, 0.3 |

| No TDF + NNRTI | 25 | 0.18 | 0.1 (0, 0.2) | −0.4, 2.4 |

| By change in ART | ||||

| No change | 108 | 0.07 | 0.1 (0, 0.1) | −0.4, 0.9 |

| Change | 41 | 0.13 | 0.1 (0, 0.2) | −0.3, 2.4 |

• Creatinine available up to 12 weeks before and after LDV/SOF treatment in only in 149 patients

Among 135 patients who had HIV RNA < 20 copies/ml prior to HCV treatment and had HIV RNA measured during or within 12 weeks of DAA completion, 15 (11%) had an increase in their HIV RNA to greater than 20 copies/ml but <100 copies/ml (HIV RNA blip). The frequency of HIV RNA blips was similar in patients who switched ART (8%) and in those who did not (13%) (P value=0.45). No patient had persistent loss of HIV suppression during and after HCV treatment. Only one patient self-discontinued DAA treatment after 2 weeks of therapy due to perceived adverse events which included dizziness and muscle spasms. This patient did not achieve SVR and the symptoms persisted after discontinuation of LDV/SOF. The patient subsequently admitted to poor oral intake and chronic constipation; symptoms resolved with intravenous fluids.

Discussion

In this real world cohort of predominantly black, inner city HIV/HCV co-infected patients, treated with oral DAAs, we observed high SVR rates (above 95%). Despite the high prevalence of psychiatric disease, and addiction disorders, the observed SVR rate was similar to that observed in registration clinical trials (6–9). These HCV cure rates were consistently high regardless of race, cirrhosis status and HCV treatment experience.

The finding of high rates of SVR across racial groups in this study contrasts with the results of two other studies. Among 115 black patients with HIV/HCV genotype 1 coinfection treated in the ION-4 trial of LDV/SOF for 12 weeks, the SVR rate of 90% (95% CI 83–95) was significantly lower than the SVR rate of 99% (95% CI 97–100) reported among the 220 patients of other races (6). In addition, in the real-world Department of Veterans Affairs HCV case registry cohort, black veterans were significantly less likely to achieve SVR (12). In our study, we found SVR rates of 96% among the 223 black patients with HIV/HCV coinfection treated with DAAs which was comparable to the SVR rate of 97% among the 32 patients of other races studied. Our data suggest that black race is not associated with reduced SVR rates in HIV/HCV co-infected patients actively engaged in collocated HIV care and HCV treatment support programs.

Indeed, the consistently high rates of SVR in our cohort, regardless of race or other potentially negative predictors of SVR such as a drug or hazardous alcohol use or mental health diagnoses may be related to the unique HCV care model implemented in our clinical practice which is centered on care delivery by the patient’s HIV care nurse with support from an integrated specialty pharmacy. Patients had routine contact (within the first week of treatment initiation and at least monthly thereafter) with the health care team for the duration of the HCV treatment course; the intensity of this contact was specifically tailored to the individual patient’s need for treatment support. While data on patient adherence was not available, we hypothesize that frequent contact with patients during HCV therapy led to higher rates of DAA adherence, which in turn led to high SVR rates. Others have hypothesized that HIV medication adherence may be improved by greater frequency of visits or contact with the health care system (21–23). Our hypothesis is also supported by another study in HIV/HCV co-infected patients in which attendance at HCV treatment follow up appointments was associated with a higher rate of SVR (24).

High rates of SVR in our study contrasts with findings from two previous studies (10, 11). Lower SVR rates in one study may be related to the predominant use of sofosbuvir plus simeprevir in the early interferon era (10). The characterization of the HIV infected population and the model of care utilized to provide HCV care could not be extracted from the other study (11). It is thus difficult to ascertain potential explanations for the lower SVR rates reported in the second study.

The observed high SVR rates in our study may also be related to treatment of a cohort of patients engaged in established HIV care with a proven record of antiretroviral adherence as evidenced by HIV RNA suppression to less than 20 copies/ml in most patients prior to HCV treatment. This observation supports the critical role for HCV medication adherence and the importance of treatment support interventions to optimize patient outcomes with DAAs. It is important to note that HIV RNA suppression and SVR rates were uniformly high regardless of recent illicit drug and/or alcohol use which was self-reported by ~ 26% of patients prior to HCV treatment. This is consistent with the outcomes reported in the C-EDGE Co-STAR study in which patients on opioid substitution therapy achieved high rates of SVR despite active drug use in more than 60% of patients with HCV mono- and HIV/HCV co-infection (25). Taken together, these data do not support the practice of withholding HCV treatment in the setting of active substance use but rather support the recommendation of the AASLD/IDSA Guidelines Panel to deliver HCV care to persons who use drugs or alcohol in settings that support HCV treatment adherence and emphasize harm reduction strategies (20). This may serve to increase the likelihood of HCV cure and decrease that of HCV reinfection through injection drug use or high-risk sex.

In our analysis, one predictor of failure to achieve SVR was an HIV RNA greater than 20 copies/mL prior to HCV treatment. In clinical trials of HCV DAAs, participants were generally required to have documented HIV suppression at the time of enrollment and there is limited data about treatment in persons not fully suppressed; which may represent incomplete adherence to antiretroviral therapy. While we did not have data for adherence to DAA therapy, patients with incomplete HIV suppression during ART may also be more likely to miss doses of HCV DAA therapy. In this regard, the short, finite course of HCV treatment (84 days for most patients) may serve to magnify the impact of DAA non-adherence on increasing the risk of HCV treatment failure. Our observation also suggests that the absence of HIV suppression in persons prescribed ART may be an important biomarker of individuals for whom more intensive adherence interventions are needed prior to initiating HCV treatment. Interestingly, we also observed that patients who had changes to their HIV treatment regimen to avoid the potential for drug interaction with HCV DAA were less likely to achieve SVR compared to those who were on stable ART. The reason for this observation is not clear since the incidence of blips in HIV RNA to detectable levels during HCV treatment was similar in both groups. We hypothesize that the combination of a relatively new antiretroviral regimen and a new HCV DAA regimen may have led to confusion about which medications to take or not take in the period surrounding an ART switch and HCV DAA initiation. These data support the selection of HCV DAA regimens that do not have anticipated drug interactions with the patient’s long-standing ART, and for increased vigilance and adherence support throughout the course of HCV treatment for patients in whom ART changes are considered necessary.

It is reassuring that the use of oral DAA therapy in our real world setting was safe with no significant changes in renal function related to oral DAA therapy observed in the majority of patients. Despite ART changes in 30% of patients, the majority of patients maintained HIV viral suppression during the course and for 12 weeks after HCV treatment completion. Additionally most patients were able to complete their recommended HCV therapy with only one discontinuation due to perceived adverse events. These observations are consistent with the safety and tolerability profile of DAA regimens observed in clinical trial populations.

Our study has multiple strengths including our ability to characterize the cohort in detail according to demographic, behavioral and HIV and HCV disease state characteristics. The inclusion of both black and non-black patients also provided an opportunity to compare outcomes in different races. The limitations of our study include its single clinical site and observational nature. Additionally, the number of patients, especially those with non-genotype 1a HCV infection were limited. However, HCV treatment outcomes in the oral DAA era among HIV-infected populations and the impact of behavioral factors and care models are just emerging. We thus believe that findings from this well-characterized cohort of HIV-infected individuals are instructive. The outcomes described were among patients who chose to enroll in the ongoing cohort study and were engaged in HIV care. Although enrollment into the cohort is not restricted based on any demographic, clinical or behavioral factors, those who declined to enroll may have been different from those who chose to enroll in the cohort. However, the prevalence of negative predictors of HIV treatment outcomes in this group, including drug and alcohol use and the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants were similar to those of the general clinic and other inner city HIV infected populations and, and so we believe that the impact of non-participation in the cohort was minimal. With implementation of appropriate care models, including structured models for treatment adherence and support such as those implemented though the Johns Hopkins HIV/HCV care model and described in this manuscript, we expect that our HCV treatment outcomes should be reproducible.

In conclusion, we found high rates of SVR among urban HIV-infected patients who received care using a standard nurse/pharmacist adherence support program. Our results from an urban clinical practice suggest that race and psychosocial comorbidity may not be barriers to HCV elimination and is indeed feasible in populations of HIV infected individuals engaged in care.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support

This work was supported by NIH/NIDA grants R01DA16065, R37DA013806 (to DT), U01DA036935, K24DA034621 (to MS), K23DA041294 (to OFN) and P30 AI094189

Abbreviations

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- LDV/SOF

ledipasvir/sofosbuvir

- DAAs

direct acting antivirals

- ART

antiretroviral treatment

- EOT

end of treatment

- SVR

sustained virologic response

- ACASI

Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview

- TDF

tenofovir disoproxil fumarate

- SIM + SOF

simeprevir plus sofosbuvir

- SOF + RBV

sofosbuvir plus ribavirin

- ProD

paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir plus dasabuvir

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

References

- 1.Sherman KE, Rouster SD, Chung RT, Rajicic N. Hepatitis C Virus prevalence among patients infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus: a cross-sectional analysis of the US adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2002;34(6):831–7. doi: 10.1086/339042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Platt L, Easterbrook P, Gower E, McDonald B, Sabin K, McGowan C, et al. Prevalence and burden of HCV co-infection in people living with HIV: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(7):797–808. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00485-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirk GD, Mehta SH, Astemborski J, Galai N, Washington J, Higgins Y, et al. HIV, age, and the severity of hepatitis C virus-related liver disease: a cohort study. Annals of internal medicine. 2013;158(9):658–66. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-9-201305070-00604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti HIVdSG. Smith C, Sabin CA, Lundgren JD, Thiebaut R, Weber R, et al. Factors associated with specific causes of death amongst HIV-positive individuals in the D:A:D Study. Aids. 2010;24(10):1537–48. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833a0918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Limketkai BN, Mehta SH, Sutcliffe CG, Higgins YM, Torbenson MS, Brinkley SC, et al. Relationship of liver disease stage and antiviral therapy with liver-related events and death in adults coinfected with HIV/HCV. JAMA. 2012;308(4):370–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.7844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naggie S, Cooper C, Saag M, Workowski K, Ruane P, Towner WJ, et al. Ledipasvir and Sofosbuvir for HCV in Patients Coinfected with HIV-1. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;373(8):705–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rockstroh JK, Nelson M, Katlama C, Lalezari J, Mallolas J, Bloch M, et al. Efficacy and safety of grazoprevir (MK-5172) and elbasvir (MK-8742) in patients with hepatitis C virus and HIV co-infection (C-EDGE CO-INFECTION): a non-randomised, open-label trial. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(8):e319–27. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sulkowski MS, Eron JJ, Wyles D, Trinh R, Lalezari J, Wang C, et al. Ombitasvir, paritaprevir co-dosed with ritonavir, dasabuvir, and ribavirin for hepatitis C in patients co-infected with HIV-1: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2015;313(12):1223–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wyles DL, Ruane PJ, Sulkowski MS, Dieterich D, Luetkemeyer A, Morgan TR, et al. Daclatasvir plus Sofosbuvir for HCV in Patients Coinfected with HIV-1. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;373(8):714–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arias A, Aguilera A, Soriano V, Benitez-Gutierrez L, Lledo G, Navarro D, et al. Rate and predictors of treatment failure to all-oral HCV regimens outside clinical trials. Antivir Ther. 2016 doi: 10.3851/IMP3061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cachay ER, Wyles D, Hill L, Ballard C, Torriani F, Colwell B, et al. The Impact of Direct-Acting Antivirals in the Hepatitis C-Sustained Viral Response in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Patients With Ongoing Barriers to Care. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2(4):ofv168. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofv168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Backus LI, Belperio PS, Shahoumian TA, Loomis TP, Mole LA. Real-world effectiveness of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir in 4,365 treatment-naive, genotype 1 hepatitis C-infected patients. Hepatology. 2016;64(2):405–14. doi: 10.1002/hep.28625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas DL, Thio CL, Martin MP, Qi Y, Ge D, O’Huigin C, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2009;461(7265):798–801. doi: 10.1038/nature08463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, Simon JS, Shianna KV, Urban TJ, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature. 2009;461(7262):399–401. doi: 10.1038/nature08309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas DL. Advances in the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. Top Antivir Med. 2012;20(1):5–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore RD, Keruly JC, Bartlett JG. Improvement in the health of HIV-infected persons in care: reducing disparities. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2012;55(9):1242–51. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, Sola R, Correa MC, Montaner J, et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43(6):1317–25. doi: 10.1002/hep.21178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirk GD, Astemborski J, Mehta SH, Spoler C, Fisher C, Allen D, et al. Assessment of liver fibrosis by transient elastography in persons with hepatitis C virus infection or HIV-hepatitis C virus coinfection. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2009;48(7):963–72. doi: 10.1086/597350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alcoholism NIoAAa. The Physicians’ Guide to Helping Patients With Alcohol Problems. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1995. Publication NIH 95–3769. [Google Scholar]

- 20.AASLD-IDSA. [Accessed January 16, 2017];Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. http://www.hcvguidelines.org.

- 21.Lucas GM, Chaisson RE, Moore RD. Highly active antiretroviral therapy in a large urban clinic: risk factors for virologic failure and adverse drug reactions. Annals of internal medicine. 1999;131(2):81–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-2-199907200-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mugavero MJ, Lin HY, Allison JJ, Giordano TP, Willig JH, Raper JL, et al. Racial disparities in HIV virologic failure: do missed visits matter? Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2009;50(1):100–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818d5c37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mugavero MJ, Lin HY, Willig JH, Westfall AO, Ulett KB, Routman JS, et al. Missed visits and mortality among patients establishing initial outpatient HIV treatment. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2009;48(2):248–56. doi: 10.1086/595705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lakshmi S, Alcaide M, Palacio AM, Shaikhomer M, Alexander AL, Gill-Wiehl G, et al. Improving HCV cure rates in HIV-coinfected patients - a real-world perspective. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(6 Spec No):SP198–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dore GJ, Altice F, Litwin AH, Dalgard O, Gane EJ, Shibolet O, et al. Elbasvir-Grazoprevir to Treat Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Persons Receiving Opioid Agonist Therapy: A Randomized Trial. Annals of internal medicine. 2016;165(9):625–34. doi: 10.7326/M16-0816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]