Abstract

Background

Cancer caregiving has been associated with worsening health among caregivers themselves, yet demographic and psychosocial predictors of their long-term health decline are less known. This study examines changes in caregivers' physical health from 2 to 8 years following their family members' cancer diagnosis and prospective predictors of that change.

Methods

Caregivers (N=664; age M=53.20) participated in a nationwide study at 2 (T1), 5 (T2), and 8 (T3) years after their family members' cancer diagnosis. Physical health (MOS SF-12 Physical Component Score) was assessed T1 through T3 as outcome. Predictors were self-reported at T1: caregiver demographics (age, gender, education, income, relationship to patient, and employment status), patient cancer severity (from medical records), and caregiver psychosocial factors (caregiving stress, caregiving esteem, social support, and depressive symptoms). Latent growth modeling tested predictors of caregivers' initial physical health and their physical health change across time.

Results

At T1, caregivers reported slightly better physical health than the U.S. population (M=51.22, p=.002), which declined over the following 6 years (Mslope=-0.27, p<.001). All demographic factors, patient cancer severity, and T1 caregiving stress were related to caregivers' initial physical health (ps<.03). Higher depressive symptoms were unrelated to caregivers' initial physical health, but were the only significant predictor of caregivers' more rapid physical health decline (B=-0.02, p=.004).

Conclusion

Findings highlight the unique contribution of caregivers' depressive symptoms to their physical health decline. Assessing and addressing depressive symptoms among caregivers early in the cancer survivorship trajectory may help to prevent premature health decline among this important, yet vulnerable population.

Keywords: family caregiver, depression, prospective studies, self report, social support

Family caregivers fill a critical role in cancer patients' treatment success, yet caregiving experience increases caregivers' own risk for long-term health decline.1-3 Psychosocial factors are known to play a significant role in caregivers' physical health decline,4,5 but prospective studies of these effects have had limited timeframes. With caregivers at risk for premature disease development relative to non-caregivers,1,3,6 interventions targeting vulnerable caregivers and addressing factors aggravating their physical health decline will be critical to reducing this health disparity. To inform this need, the current study examines a set of risk factors, both relatively stable demographic and more readily modifiable psychosocial factors, as predictors of cancer caregivers' physical health decline from 2 to 8 years following their family members' cancer diagnosis.

Physical health decline is aggravated by prolonged stress, as when caregiving demands exceed perceived resources.7,8 Several caregiver demographic factors have been linked to greater caregiving stress and risk for premature morbidity, such as older age,2,6 female gender,2,6 less education,4,9 lower household income,6 and employment during caregiving.10 The caregiver being the patient's spouse6,9 and the patient having high disease severity10,11 also relate to their higher physical health risk. While the relations of these demographic and patient disease variables with caregivers' health are well-documented through the acute phase after the cancer diagnosis and during treatment, most studies have only examined the first year following the cancer diagnosis and treatment. Less is known about how these factors may identify caregivers at greatest risk for longer-term physical health decline.

Caregivers' subjective experiences through the cancer trajectory also affect their physical health. Caregivers who report greater social support satisfaction12 and deriving self-esteem from caregiving4 exhibit more favorable physical health outcomes. Caregivers' psychological distress is also a powerful predictor of their physical health decline. Caregivers' perceived stress from the cancer experience has been found to relate to their physical health outcomes more strongly than objective measures of caregiving burden.6,13 Depressive symptoms have also been shown strongly related to physical morbidity among both healthy adults14,15 and caregivers specifically.9,12 Although limited in terms of number of studies and maintenance of benefits, psychosocial interventions have helped improve these domains, suggesting that these factors are modifiable.16,17

With cancer caregivers at risk for premature morbidity, three recent Institute of Medicine/National Academy of Medicine reports18-20 and a consensus statement from the National Cancer Institute and National Institute of Nursing Research21 have called for interventions to foster caregivers' health. A better understanding of the risk factors for caregivers' long-term health decline is needed to develop targeted assessment and intervention strategies that use clinical resources effectively. To that end, this prospective, observational study examined associations of a set of risk factors with physical health in a national sample of cancer caregivers from 2 to 8 years following their family members' cancer diagnosis. First, we examined the extent to which caregivers' physical health changed across this period. Next, we tested the extent to which caregivers' demographics, patient cancer severity, and psychosocial factors related to initial levels of physical health at 2 years post-diagnosis as well as their change in physical health over time.

Method

Participants

The National Quality of Life Survey for Caregivers22 was designed to longitudinally assess the impact of cancer on the quality of life of family members and close friends who provide care for cancer survivors. Survivors were identified using multiple state cancer registries as having been diagnosed with one of the 10 most common cancers,23 and were asked to nominate adult family or family-like individuals who provided consistent assistance during their cancer experience. Eligible caregivers were: (a) 18 years of age or older, (b) fluent in either English or Spanish, and (c) a resident of the United States.

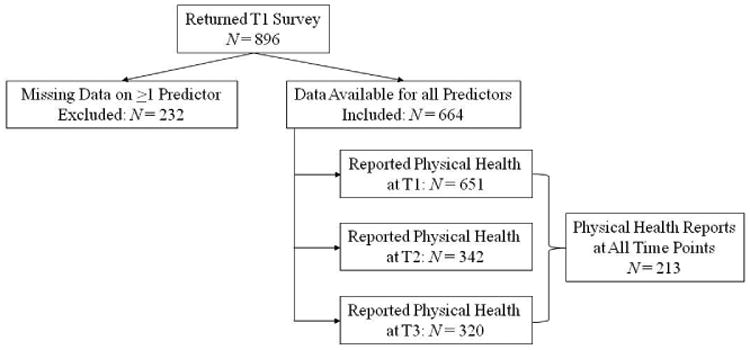

Caregivers (N=896) returned the baseline survey at 2 years post-diagnosis (T1; data collected 2003-2004). Follow-up data collection occurred at 5 years (T2; 2006-2007)24 and 8 years post-diagnosis (T3; 2009-2010).25 Caregivers were included in analyses (N=664) if they provided complete data on all predictor variables at T1; each of the 664 included caregivers provided complete data for the physical health measure for at least 1 time point (see Figure 1). Included caregivers differed from those excluded (due to missing data on any predictor variable; N=232) on the following predictor variables reported at T1: excluded caregivers were older (Ms=58.69 excluded vs. 53.14 included; t(861)=-5.47, p<.001; d=.37) and a greater proportion of the excluded sample reported educational attainment at a high school diploma or less (32.2% vs. 23.0%; χ2(1,875)=7.16, p=.01; φ=.09) and being unemployed (35.9% vs. 23.0%; χ2(1,884)=14.13, p<.001; φ=.13). Compared to included caregivers, those excluded also reported poorer physical health at T1 (Ms=48.42 vs. 51.24; t(830)=3.22, p=.001; d=.22) and T2 (Ms=48.27 vs. 50.51; t(458)=2.16, p=.03; d=.20).

Figure 1. Cancer Caregiver Participation by Time Point.

Note. T1 = 2 years after the patient's diagnosis; T2 = 5 years post-diagnosis; T3 = 8 years post-diagnosis; Physical health reported using the Physical Health Component Scale of the MOS SF-12.

Procedure

This prospective, observational study complied with regulations of the Emory University Institutional Review Board. Nominated caregivers received a packet including an introduction letter, the survey, a self-addressed stamped envelope, and compensation (pre-paid calling card at T1; $10 gift cards at T2, T3). Caregivers self-reported all measures by paper. Informed consent was evidenced by returning the completed survey. For each time point, 2 cycles of mailing and follow-up telephone calls were made across the 8-week data collection period.

Measures

Caregiver physical health

At each time point, caregivers self-reported their levels of physical health using the 12-item Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Health Survey (MOS-SF-12).26 The physical health component score represents a weighted composite of physical functioning, physical limitations to role requirements, bodily pain, and general health subscales. Scores were normalized (U.S. population normalized M=50). Higher scores reflect better physical health.26 This measure has been widely used to measure physical health in studies of cancer caregivers.27-30

Demographic and patient cancer severity predictors of caregiver physical health

Caregivers self-reported their age, gender, education, employment status, and household income at T1. Patients' cancer diagnosis date, stage, and type were obtained from the state cancer registry at T1. The patient's cancer severity was based on mortality rates calculated from cancer type, stage, and time since diagnosis.6,11 Higher scores reflect greater severity of illness.

Psychosocial predictors of caregiver physical health

Caregivers self-reported the following measures at T1.

Caregiving stress

The extent to which caregivers felt overwhelmed by providing care to their family member was measured using the 4-item Stress Overload subscale of the Pearlin Stress Scale.7 Response options ranged from 1 Not at All to 4 Completely. Higher mean scores indicate greater subjective caregiving stress. This scale has shown good internal consistency in prior cancer caregiver samples (Cronbach's α=.79-.80)31,32 and in the current sample (Cronbach's α=.81).

Caregiver esteem

Caregivers' self-esteem related to providing care to their family member was assessed using the 7-item Caregiver Esteem subscale of the Caregiving Reaction Assessment.33 Response options ranged from 1 Strongly Disagree to 5 Strongly Agree. Higher mean scores indicate greater caregiver esteem. This scale has shown good internal consistency in prior cancer caregiver samples (Cronbach's α=.82)4 and in the current sample (Cronbach's α=.73).

Social support

The extent to which caregivers perceived that emotional, informational, and instrumental support were available to them was measured using the 6-item version of the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List.34 Response options ranged from 1 Definitely False to 4 Definitely True. Higher mean scores indicate greater perceived social support availability. This measure has shown good internal consistency in dementia caregiver samples (Cronbach's α=.79)35 and in the current sample (Cronbach's α=.77).

Depressive symptoms

The extent to which family caregivers experienced neurovegetative, affective, and interpersonal symptoms associated with depression was assessed using the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale.36 Response options ranged from 0 Rarely or None of the Time to 3 Most or All of the Time. Higher sum scores indicate greater overall depressive symptomatology. This measure has shown good internal consistency in cancer caregiver samples (Cronbach's α=.87)4 and in the current sample (Cronbach's α=.93).

Analysis Plan

Descriptive information for study variables is presented in Table 1. For all analyses, ps<.05 were considered significant. Central aims of the study were analyzed using latent growth modeling (LGM) using a structural equation modeling (SEM) framework (Mplus 7).37 Missing physical health data were accounted for by Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation. While most unplanned missingness in psychosocial research is at some level missing not at random, we sought to reduce bias produced by this mechanism by including variables associated with missingness in our models.41,42

Table 1. Sample Descriptives for National Sample of Cancer Caregivers (N=664).

| M(SD) | Range | N(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 53.20(12.59) | 18.32–89.98 | – |

| Gender (Female) | – | – | 63.0% |

| Education (Some College or More) | – | – | 77.0% |

| Household Income ($40,000 or More) | – | – | 78.6% |

| Relation to Patient (Spouse) | – | – | 66.1% |

| Employment Status (Employed) | – | – | 77.0% |

| Patient Cancer Severity | 0.16(0.23) | 0–0.94 | – |

| Subjective Caregiving Stress | 1.61(0.62) | 1–4 | – |

| Caregiving Esteem | 4.38(0.50) | 2.43–5 | – |

| Social Support | 3.39(0.63) | 1–6 | – |

| Depressive Symptoms | 10.86(10.32) | 0–55 | – |

|

| |||

| Physical Health | M(SD) | Range | N complete |

| 2 Years Post-Diagnosis (T1) | 51.24(10.06)a | 8.19–70.97 | 651 |

| 5 Years Post-Diagnosis (T2) | 50.51(9.24)b | 16.53–69.16 | 342 |

| 8 Years Post-Diagnosis (T3) | 49.44(9.50)c | 19.95–69.98 | 320 |

Note. Superscript for Physical Health means corresponds to results from single-sample t-tests comparing raw sample mean to the U.S. normalized mean of 50. Pattern of findings using t-tests does not differ from that using Latent Growth Modeling and Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation to compare means to 50.

T1sample mean was significantly greater than 50 (t(650)=3.14, p=.002)

T2 sample mean was not significantly different from 50 (t(341)=1.02, p=.31)

T3 sample mean was not significantly different from 50 (t(319)=-1.05, p=.29)

First, a measurement model of the LGM estimating caregivers' physical health trajectory was tested. The LGM estimated 2 latent parameters: initial level of health (intercept) and change in health (slope) across the 3 assessments.38-40 Linear change by year was estimated by fixing loadings for the 3 physical health indicators to the intercept latent variable to 1 and to the slope latent variable to 0, 3, and 6 for T1 through T3, respectively. To facilitate interpretation, physical health scores were centered at 50 (i.e., normalized mean for the U.S. population), and continuous predictor variables were centered to the sample mean.

Next, SEM was used to test the relations of risk factors measured at T1 with caregivers' initial levels and change in physical health. For both models, fitness was evaluated based on 4 model fit indices: χ2 p>.05, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)<.06, comparative fit index (CFI)>.95, and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR)<.08 indicating adequate model fit to the data.43,44

Results

Caregivers included in the current data analysis returned surveys from 34 states. Specifically, 40% of caregivers responded from the Northeast region, 39% from the Midwest, 18% from the South, and 3% from the West. Participating caregivers overall were middle-aged, primarily female, and relatively well-educated and affluent (Table 1). Most caregivers were the patient's spouse and employed. Overall, caregivers reported that caregiving was “somewhat” stressful, yet boosted their self-esteem, and that social support was “somewhat” available. Caregivers' average reported depressive symptoms fell below the clinical cutoff of 1636 and were comparable to those seen among other studies of cancer caregivers.4,45

As shown in Figure 1, missingness on the outcome variable of physical health ranged from 2% at T1 to 52% at T3, with 68% of the sample missing complete data for the outcome variable for at least 1 time point. Correlates of missingness were examined: there was no correlate of missingness at T1 with any study variable (ps>.06); compared to those with missing data, caregivers with data available at T2 and T3 were older by approximately 3 years and were 1.2 times more likely to be the patients' spouse (ps<.003), but there was no other correlate of missingness (ps>.05). FIML, standard to MPlus 7,37 incorporates data from correlates of missingness included in the model to reduce bias in estimates.

Caregivers' Physical Health 2 to 8 Years Post-Diagnosis

First, the measurement model of the change in caregivers' physical health over time (LGM) was tested for model fit. The measurement model fit the data: χ2(1)=0.13, p=.71; RMSEA=0; CFI=1; SRMR=.004. Caregivers' average initial level of physical health at 2 years post-diagnosis was higher than the normalized mean for the U.S. population of 50 (M=1.22; 95% CI=0.46, 1.98; p=.002), and this varied between caregivers (s2= 69.25; 95% CI=52.55, 85.95; p=.002). On average, caregivers reported a decline in their physical health by approximately ¼ point per year (M=-0.27; 95% CI=-0.41, -0.12; p<.001). The resulting decrease of approximately 1.5 points over the 6 years of the study represents a small effect (d=.16).46 Caregivers did not vary significantly in their rate of physical health decline (s2=0.36; 95% CI=-0.53, 1.26; p=.43). Caregivers' initial level of physical health was unrelated to their rate of change in physical health (Unstandardized estimate=-1.63; 95% CI=-4.93, 1.68; p=.34).

Predicting Caregivers' Physical Health

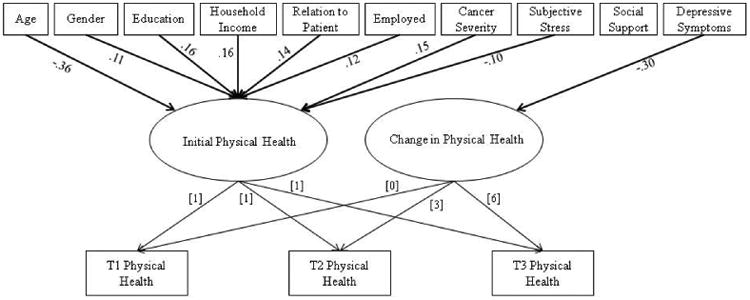

Next, the fit of the structural equation model predicting caregivers' initial level and change in physical health by risk factors was tested (see Figure 2). The specified model fit the data according to 3 model fit indices: RMSEA=.04; CFI=.99; SRMR=.08; yet the χ2 index indicated suboptimal fit: χ2(12)=24.25, p=.02. As this index is sensitive to large sample size and the current model drew from 664 participants, the model was accepted based on adequate fit to the alternative fit indices. Path estimates are shown in Table 2; model identification and significant paths are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Predictors of Initial Level and Change in Physical Health among Cancer Caregivers.

Note. Numeric values without brackets are standardized estimates; numeric values within brackets are factor weights; only significant (p < .05) paths are shown from predictors; Gender = 0 for male, 1 for female; Education = 0 for high school or less, 1 for college or more; Income = 0 for <$40,000, 1 for >$40,000; Relation = 0 for not spouse, 1 for spouse; Employed = 0 for not employed, 1 for employed; T1 = 2 years after the patient's diagnosis, T2 = 5 years post-diagnosis, T3 = 8 years post-diagnosis.

Table 2. Path Estimates.

| Unstandardized | Standardized | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| B | [95% CI] | p | β | |

| Predictors of Initial Level of Physical Health (intercept) | ||||

| Age | -0.25 | [-0.31,-0.18] | <.001 | -.36 |

| Gender | 1.93 | [0.33,3.52] | .02 | .11 |

| Education | 3.28 | [1.58,4.97] | <.001 | .16 |

| Household Income | 3.34 | [1.49,5.19] | <.001 | .16 |

| Relation to Patient | 2.45 | [0.78,4.11] | .004 | .14 |

| Employed | 2.50 | [0.67,4.33] | .01 | .12 |

| Patient Cancer Severity | 5.49 | [2.47,8.50] | <.001 | .15 |

| Subjective Caregiving Stress | -1.38 | [-2.64,-0.12] | .03 | -.10 |

| Caregiving Esteem | 0.55 | [-0.86,1.95] | .45 | .03 |

| Social Support | 0.60 | [-0.71,1.92] | .37 | .04 |

| Depressive Symptoms | -0.02 | [-0.10,0.06] | .62 | -.02 |

| Predictors of Change in Physical Health (slope) | ||||

| Age | 0.003 | [-0.01,0.02] | .68 | .05 |

| Gender | -0.11 | [-0.45,0.23] | .51 | -.07 |

| Education | 0.35 | [-0.71,0.02] | .06 | .18 |

| Household Income | 0.10 | [-0.29,0.49] | .62 | .05 |

| Relation to Patient | -0.22 | [-0.58,0.15] | .25 | -.12 |

| Employed | -0.15 | [-0.54,0.25] | .46 | -.08 |

| Patient Cancer Severity | -0.04 | [-0.67,0.60] | .91 | -.01 |

| Subjective Caregiving Stress | -0.04 | [-0.31,0.24] | .79 | -.03 |

| Caregiving Esteem | -0.20 | [-0.50,0.11] | .20 | -.12 |

| Social Support | -0.03 | [-0.31,0.25] | .83 | .02 |

| Depressive Symptoms | -0.02 | [-0.04,-0.01] | .004 | -.30 |

Note. Gender = 1 for male, 2 for female; Education = 0 for high school or less, 1 for college or more; Income = 0 for <$40,000, 1 for >$40,000; Relation = 0 for not spouse, 1 for spouse; Employed = 0 for not employed, 1 for employed.

Predicting initial level of physical health

Several factors related to caregivers' initial level of physical health 2 years post-diagnosis. Among the demographic factors and patient cancer severity, caregivers who were older, male, not the caregivers' spouse, unemployed, had a high school education or less, household income under $40,000 per year, and provided care to a patient with a better cancer prognosis reported poorer initial physical health. Regarding psychosocial factors, only higher subjective caregiving stress was concurrently related to lower caregiver initial health.

Predicting change in physical health

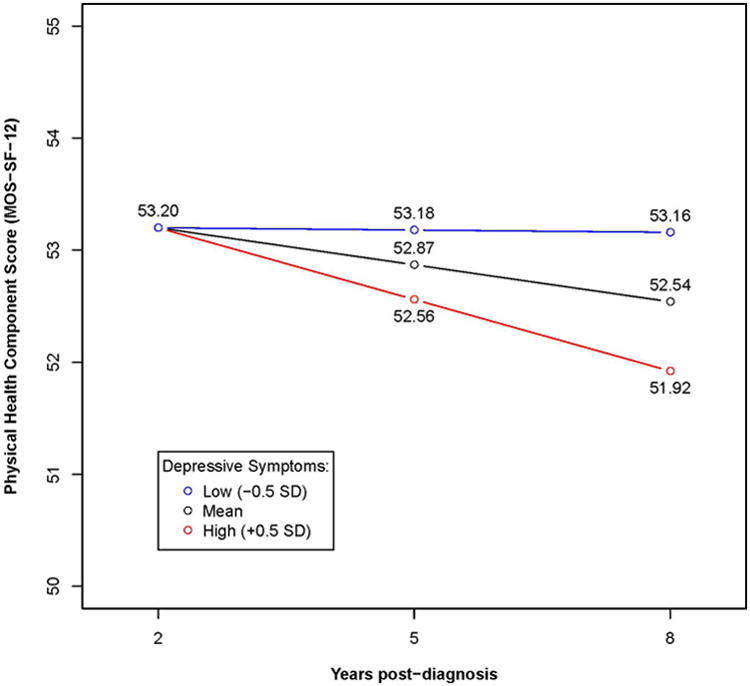

Regarding change in caregivers' physical health across 2 to 8 years after the diagnosis, only caregivers' depressive symptoms was a significant predictor. Caregivers who reported higher depressive symptoms 2 years post-diagnosis showed more rapid physical health decline over the following 6 years. No other factors predicted caregivers' change in physical health. With all other factors held constant at the sample mean, a caregiver who reported high depressive symptoms (i.e., CES-D score 0.5 SD above average) would be expected to show physical health decline at twice the rate of a caregiver with an average level of depressive symptoms (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Demonstration of Predicted Physical Health Report Scores from 2 to 8 Years Post-Diagnosis According to Level of Depressive Symptoms.

Note. Depressive symptoms measured by Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale; Slope and predicted data points estimated holding all predictors to sample mean, Gender = 1 for male, Education = 0 for high school or less, Income = 0 for <$40,000, Relation = 0 for not spouse, Employed = 0 for not employed.

Discussion

This study documents the longest prospective examination of the effects of demographic, patient cancer severity, and psychosocial factors on cancer caregivers' physical health to date. Caregivers' physical health at 2 years post-diagnosis was slightly higher than the national mean; however, that advantage dissipated over the following 6 years, as caregivers experienced a small yet reliable decline in self-reported health. Among a comprehensive set of potential risk factors, only caregivers' depressive symptoms prospectively predicted their physical health decline from 2 to 8 years post-diagnosis.

Caregivers' physical health started somewhat higher and declined less rapidly than documented in prior studies using the SF-12 with cancer caregivers during the patients' active treatment phase.47,48 This may reflect both improved sense of physical health following the acute diagnosis and treatment phase, as well as the fact that larger population-based studies of caregivers tend to show better physical health outcomes relative to samples from smaller and interventional studies.49 At 2 years following the patients' cancer diagnosis, caregivers' initial health was associated primarily with the relatively fixed demographic factors and patients' cancer severity. Findings that caregivers who were older and of lower socioeconomic status reported poorer physical health at T1 fit with prior literature.2,4,6,9

Several other findings are discrepant from prior literature—caregivers who were male, not the patients' spouse, and those with better patient prognosis also reported poorer physical health at T1.6,10,11 These descrepant effects were small, which fits with findings from a meta-analytic study showing that, when caregiver characteristics are associated with their own self-reported physical health, effect sizes are typically minimal.9 In contrast with the demographic risk factors of which all were related to initial physical health, caregivers' perceived stressfulness of the cancer experience was the only psychosocial risk factor concurrently related to caregivers' physical health. Caregiving responsibilities can be complicated by being in poor physical condition one's self, suggesting caregivers' own physical health may represent an important contextual characteristic relevant to the perceived stress of caregiving.50

Perhaps most striking, T1 depressive symptoms—although not concurrently related with physical health—were the only predictor of caregivers' physical health decline, affirming that caregivers' early depressive symptoms have downstream effects on their physical health as long as 6 years later. Findings are consistent with with prior literature demonstrating that caregiver demographic characteristics have been more consistently associated with caregivers' concurrent physical health reports, while psychosocial variables have predicted caregivers' longer-term physical health changes.6,9 The 1.28-point predicted difference between the caregiver with high versus low depressive symptoms 8 years post-diagnosis (see Figure 3), at the population level, translates roughly to 6% higher total healthcare expenditures, 9% higher rate of inpatient hospitalizations, and 5% higher rate of outpatient hospital visits for the caregiver with high symptoms.51 Adverse effects of depression on physical health have been well-documented in the general population.9,14,15 These findings extend evidence to the cancer caregiving context, known to have many psychosocial stressors and challenges, and highlight the importance of depression specifically to caregivers' premature physical health decline.

Depressive symptoms are common among cancer caregivers.52,53 Implementing caregiver depression screening and increasing caregivers' access to effective depression treatments may mitigate the premature physical health decline endemic to cancer caregiving. To date, caregiver distress screening implementation has been limited, yet could be more widely adopted by capitalizing on current efforts to implement routine patient distress screening.54-56 Successful examples of caregiver mental health assessment and referral systems built from patient distress screening models exist, with technology-based assessment using brief and straightforward questions to assess whether a caregiver has been experiencing depression or low mood.57,58

To improve health outcomes, screening must link those identified as reporting high depressive symptoms to timely, effective interventions. Existing psychosocial interventions with caregivers have shown limited effect on caregiver depressive symptoms.59 Developing and refining interventions to successfully address caregivers' depressive symptoms during the acute cancer phase must be a research priority, not only to improve caregivers' quality of life, but also to address the notable health disparities between adults with versus without caregiving experience. To address this double aim, interventions with caregivers may seek to emphasize strategies shown to improve both mental and physical health, such as relaxation, meditation, and exercise.60

Limitations of this study restrict the generalizability of findings. The study sample was primarily non-Hispanic white and well-educated. Moreover, caregivers included in analyses were younger, healthier, and of higher socioeconomic status than those excluded, and younger and non-spousal caregivers were more likely to have missing data at follow-ups, although all differences were small. Study of long-term physical health sequelae of caregiving should be conducted among caregivers of other ethnic groups and those with fewer socioeconomic resources, as health disparities known to exist among these groups are likely amplified by the additive stress from caregiving. Lastly, variables were self-reported and possibly biased by social desirability, and the SF-12 represents a very general measure of physical health quality of life. Future study of caregivers' health may seek to replicate findings with more specific, objective markers of health. Assessing biomarkers, such as genome expression,61 pro-inflammatory cytokines,3,12 and telomerase activity,62 will improve our understanding of biological mechanisms by which caregivers' health is affected by the caregiving experience.

This study provides novel information regarding cancer caregivers' long-term physical health decline, with the longest follow-up to date of caregivers' physical health following providing care to a loved one with cancer. Notably, only caregivers' higher depressive symptoms predicted their accelerated physical health decline from 2 to 8 years following the patients' diagnosis. Providing effective, targeted, and timely psychosocial care for cancer caregivers around the time of their relative's diagnosis and treatment may help to prevent premature health decline among this important, yet vulnerable population.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the ACS National Home Office, intramural research. Writing of this manuscript was supported by the NCI (F31CA189431-01A1 – PI: Kelly Shaffer; T32 CA009461 – PI: Jamie Ostroff; NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748 – PI: Craig Thompson) and ACS Research Scholar Grant (121909-RSG-12-042-01-CPPB – PI: Youngmee Kim).

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Authors contributions statement: Kelly Shaffer was involved in project conceptualization, development of methodology, formal data analysis, resource provision, data management, writing (drafting and revision), visualization, and manuscript supervision. Dr. Shaffer is the guarantor for the content of this manuscript. Youngmee Kim was involved in conceptualization, development of methodology, investigation process, resource provision, data management, writing (drafting and revision), visualization, manuscript supervision, and funding acquisition. Charles Carver was involved in conceptualization, revision and editing, and manuscript supervision. Rachel Cannady was involved in investigation process, data management, revision and editing, project administration, and funding acquisition.

References

- 1.Ji J, Zöller B, Sundquist K, et al. Increased risks of coronary heart disease and stroke among spousal caregivers of cancer patients. Circulation. 2012;125:1742–1747. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.057018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nijboer C, Tempelaar R, Triemstra M, et al. Dynamics in cancer caregiver's health over time: Gender-specific patterns and determinants. Psychol Health. 2001;16:471–488. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rohleder N, Marin TJ, Ma R, et al. Biologic cost of caring for a cancer patient: dysregulation of pro-and anti-inflammatory signaling pathways. J Clin Onc. 2009;27:2909–2915. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.7435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Given CW, et al. Depression and physical health among family caregivers of geriatric patients with cancer–a longitudinal view. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10:456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality. JAMA. 1999;282:2215–2219. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim Y, Carver CS, Shaffer KM, et al. Cancer caregiving predicts physical impairments: Roles of earlier caregiving stress and being a spousal caregiver. Cancer. 2015;121:302–310. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, et al. Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30:583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vitaliano PP, Zhang J, Scanlan JM. Is caregiving hazardous to one's physical health? A meta-analysis Psychol Bull. 2003;129:946. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Correlates of Physical Health of Informal Caregivers: A Meta-Analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62:P126–P137. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.p126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown SL, Smith DM, Schulz R, et al. Caregiving behavior is associated with decreased mortality risk. Psychol Sci. 2009;20:488–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim Y, Baker F, Spillers RL. Cancer caregivers' quality of life: effects of gender, relationship, and appraisal. J Pain Symp Manage. 2007;34:294–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller GE, Cohen S, Ritchey AK. Chronic psychological stress and the regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines: a glucocorticoid-resistance model. Health Psychol. 2002;21:531. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.6.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Son J, Erno A, Shea DG, et al. The caregiver stress process and health outcomes. J Aging Health. 2007;19:871–887. doi: 10.1177/0898264307308568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinquart M, Duberstein P. Depression and cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1797. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosengren A, Hawken S, Ôunpuu S, et al. Association of psychosocial risk factors with risk of acute myocardial infarction in 11 119 cases and 13 648 controls from 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:953–962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Applebaum AJ, Breitbart W. Care for the cancer caregiver: A systematic review. Pall Supp Care. 2013;11:231–252. doi: 10.1017/S1478951512000594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Northouse L, Williams A, Given B, et al. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. J Clin Onc. 2012;30:1227–1234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Medicine. From Cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. 2005. Commission on Cancer Survivorship. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adler NE, Page AEK, editors. Institute of Medicine. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Families Caring for an Aging America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, et al. Caring for caregivers and patients: Research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer. 2016 doi: 10.1002/cncr.29939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim Y, Spillers RL. Quality of life of family caregivers at 2 years after a relative's cancer diagnosis. Psycho-Onc. 2010;19:431–440. doi: 10.1002/pon.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith T, Stein KD, Mehta CC, et al. The rationale, design, and implementation of the American Cancer Society's studies of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2007;109:1–12. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim Y, Spillers RL, Hall DL. Quality of life of family caregivers 5 years after a relative's cancer diagnosis: follow-up of the national quality of life survey for caregivers. Psycho-Onc. 2012;21:273–281. doi: 10.1002/pon.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim Y, Shaffer KM, Carver CS, et al. Quality of life of family caregivers 8 years after a relative's cancer diagnosis: follow-up of the National Quality of Life Survey for Caregivers. Psycho-Onc. 2015 doi: 10.1002/pon.3843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim Y, Ryn M, Jensen RE, et al. Effects of gender and depressive symptoms on quality of life among colorectal and lung cancer patients and their family caregivers. Psycho-Onc. 2014 doi: 10.1002/pon.3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim Y, Wellisch DK, Spillers RL. Effects of psychological distress on quality of life of adult daughters and their mothers with cancer. Psycho-Onc. 2008;17:1129–1136. doi: 10.1002/pon.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lambert SD, Jones BL, Girgis A, et al. Distressed partners and caregivers do not recover easily: adjustment trajectories among partners and caregivers of cancer survivors. Ann Beh Med. 2012;44:225–235. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moser MT, Künzler A, Nussbeck F, et al. Higher emotional distress in female partners of cancer patients: prevalence and patient–partner interdependencies in a 3-year cohort. Psycho-Onc. 2013;22:2693–2701. doi: 10.1002/pon.3331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaugler JE, Hanna N, Linder J, et al. Cancer caregiving and subjective stress: a multi-site, multi-dimensional analysis. Psycho-Onc. 2005;14:771–785. doi: 10.1002/pon.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim Y, Loscalzo MJ, Wellisch DK, et al. Gender differences in caregiving stress among caregivers of cancer survivors. Psycho-Onc. 2006;15:1086–1092. doi: 10.1002/pon.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Given CW, Given B, Stommel M, et al. The caregiver reaction assessment (CRA) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairments. Res Nurs Health. 1992;15:271–283. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770150406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, et al. Social support: Theory, research and applications. Springer; 1985. Measuring the functional components of social support; pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson-Whelen S, Tada Y, MacCallum RC, et al. Long-term caregiving: what happens when it ends? J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110:573. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muthé L, Muthén B. MPlus User's Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bollen KA, Curran PJ. Latent curve models: A structural equation perspective. John Wiley & Sons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muthén BO, Curran PJ. General longitudinal modeling of individual differences in experimental designs: A latent variable framework for analysis and power estimation. Psychol Methods. 1997;2:371. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Willett JB, Sayer AG. Using covariance structure analysis to detect correlates and predictors of individual change over time. Psychol Bull. 1994;116:363–363. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Enders CK. A primer on the use of modern missing-data methods in psychosomatic medicine research. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:427–436. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221275.75056.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu Lt, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim Y, Duberstein PR, Sörensen S, et al. Levels of depressive symptoms in spouses of people with lung cancer: effects of personality, social support, and caregiving burden. Psychosomatics. 2005;46:123–130. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kazis LE, Anderson JJ, Meenan RF. Effect sizes for interpreting changes in health status. Med Care. 1989;27:S178–S189. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Northouse LL, Mood DW, Schafenacker A, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a family intervention for prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer. 2007;110(12):2809–2818. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shaffer KM, Kim Y, Carver CS. Physical and mental health trajectories of cancer patients and caregivers across the year post-diagnosis: A dyadic investigation. Psychol Health. 2016;31(6):655–674. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2015.1131826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Capistrant BD. Caregiving for older adults and the caregivers' health: An epidemiologic review. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2016;3(1):72–80. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fletcher BS, Miaskowski C, Given B, et al. The cancer family caregiving experience: an updated and expanded conceptual model. Eur J Onc Nurs. 2012;16:387–398. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Health Services Advisory Group. Report on a Longitudinal Assessment of Change in Health Status and the Prediction of Health Utilizations, Health Expenditures, and Experiences with Care for Beneficiaries in Medicare Managed Care. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, editor. [Accessed February 22, 2017];2006 http://www.hosonline.org/globalassets/hos-online/publications/hos_longitudinal_utilization_expenditures.pdf.

- 52.Kessler ER, Moss A, Eckhardt SG, et al. Distress among caregivers of phase I trial participants: a cross-sectional study. Supp Care Cancer. 2014;22:3331–3340. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2380-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rhee YS, Yun YH, Park S, et al. Depression in family caregivers of cancer patients: the feeling of burden as a predictor of depression. J Clin Onc. 2008;26:5890–5895. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.3957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cancer Program Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Holland JC, Andersen B, Breitbart WS, et al. Distress management. JNCCN. 2013;11:190–209. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Neuss MN, Polovich M, McNiff K, et al. 2013 updated American Society of Clinical Oncology/Oncology Nursing Society chemotherapy administration safety standards including standards for the safe administration and management of oral chemotherapy. J Onc Prac. 2013;9:5s–13s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.000874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bitz C, Clark K, Vito C, et al. Partners' clinic: an innovative gender strengths-based intervention for breast cancer patients and their partners immediately prior to initiating care with their treating physician. Psycho-Onc. 2015;24:355–358. doi: 10.1002/pon.3604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kauffmann R, Bitz C, Clark K, et al. Addressing psychosocial needs of partners of breast cancer patients: a pilot program using social workers to improve communication and psychosocial support. Supp Care Cancer. 2016;24:61–65. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2721-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, et al. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:317–339. doi: 10.3322/caac.20081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lambert SD, Duncan LR, Kapellas S, et al. A Descriptive Systematic Review of Physical Activity Interventions for Caregivers: Effects on Caregivers' and Care Recipients' Psychosocial Outcomes, Physical Activity Levels, and Physical Health. Ann Beh Med. 2016;50:907–919. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9819-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miller GE, Chen E, Sze J, et al. A functional genomic fingerprint of chronic stress in humans: blunted glucocorticoid and increased NF-κB signaling. Biol Psych. 2008;64:266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Damjanovic AK, Yang Y, Glaser R, et al. Accelerated telomere erosion is associated with a declining immune function of caregivers of Alzheimer's disease patients. J Immunol. 2007;179:4249–4254. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]