Abstract

Background

Both the CMS Hospital Compare Star rating and surgical case volume have been publicized as metrics that help patients identify high-quality hospitals for complex care such as cancer surgery. The current study evaluates the relationships between CMS' Star rating, surgical volume, and short-term outcomes following major cancer surgery.

Methods

We used national Medicare data to evaluate the relationship between hospital Star ratings and cancer surgery volume quintile. We then fit multi-level logistic regression models to examine the association between cancer surgery outcomes and both Star rankings and surgical volumes. Lastly, we used a graphical approach to compare how well Star ratings and surgical volume predict cancer surgery outcomes.

Results

We identified 365,752 patients undergoing major cancer surgery for 1 of 9 cancer types at 2,550 hospitals. Star rating is not associated with surgical volume (p<0.001). However, both Star rating and surgical volume are correlated with four short-term cancer surgery outcomes (mortality, complication rate, readmissions, and prolonged length of stay). Adjusted predicted probabilities for 5 and 1 star hospitals were 2.3 vs. 4.5% mortality, 39 vs. 48% complications, 10 vs. 15% readmissions, and 8 vs. 16% prolonged length of stay. Adjusted predicted probabilities for hospitals with the highest and lowest quintile cancer surgery volume were: 2.7% vs. 5.8% mortality, 41 vs. 55% complications, 12.2 vs. 11.6% readmissions, and 9.4 vs. 13% prolonged length of stay. Furthermore, volume and Star rating are similarly correlated with mortality and complications, while Star rating is better correlated with readmissions and prolonged length of stay.

Conclusions

In the absence of other information, our findings suggest that the Star rating may be useful to help patients select a hospital for major cancer surgery. However, more research is needed before these ratings can supplant surgical volume as a measure of surgical quality.

Keywords: Quality, cancer surgery, outcomes, patient decision making, publicly available hospital ratings

Introduction

Selecting a hospital for cancer surgery is challenging. Likewise, the best way for patients to determine where to obtain hospital-based health care remains a topic of debate both in the lay press and the scientific literature (1-4). In an attempt to help patients make such decisions, several private and public organizations have released rating guides that rank hospitals according to various measures of quality and safety (5-7).

The newest measure in this area is the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services' (CMS) Hospital Compare Star rating system. This program uses complex methodology — based on a hospital's performance with mortality, safety, readmissions, patient experience, care effectiveness, care timeliness, and efficient use of medical imaging — to assign each hospital a Star rating ranging from 1 (lowest score) to 5 (highest score). The stated goal for this program is “To help millions of patients and their families learn about the quality of hospitals, compare facilities in their area side-by-side, and ask important questions about care quality when visiting a hospital or other health care provider (8).” While the Star ratings have the benefit of being publically available, the system has been criticized by some as being inaccurate, and there is little empirical data that validates the relationship between Star ratings and important patient outcomes, including with major cancer surgery (9).

In contrast, arguably the best structural measure of quality for major cancer surgery is surgical case volume. Illustrating this point, several prominent health systems have issued a volume pledge for select surgical procedures, including some major cancer operations, as a way to demonstrate their commitment to transparency and high quality care(10). For the most part, however, the impact of this metric remains limited by the fact that hospital surgical volumes are not routinely available to the public.

In this context, an important question is whether — for major cancer surgery — a hospital's annual surgical volume correlates strongly with its Hospital Compare Star rating. Furthermore, it is unknown whether one of these measures more strongly predicts important patient outcomes. The availability of such data would not only clarify the relevance of the Star rating system for patients in need of major cancer surgery, it would also provide a better sense of its potential value as a quality metric for a broader range of conditions. Accordingly, we used data from the Hospital Compare program and national Medicare claims to evaluate the relationship between CMS' Star rating and surgical volume for hospitals performing major cancer surgery. We also examined the frequency of short-term adverse outcomes based on Star rating versus surgical volumes, and assessed the relative predictive value of these measures for short-term adverse outcomes after major cancer surgery.

Methods

Data sources

We utilized three data sets to perform this analysis. We used the 100% Medicare Provider Analysis and Review File from 2011 to 2013 to identify the patient cohort, clinical data, and outcomes of interest. We also used the 2016 Hospital Compare publically available data to identify hospital Star ranking, and the American Hospital Association Annual survey to evaluate hospital characteristics.

Study population

Our study population included Medicare beneficiaries aged 66 to 99 years who underwent a major extirpative surgery for colorectal, prostate, bladder, esophageal, kidney, liver, lung, ovarian, or pancreatic cancer from January 1, 2011 through November 30, 2013. Since we wanted to answer the question of whether a typical patient can use the Hospital Compare Star rating system to choose a hospital for major cancer surgery, we excluded patients based on two criteria. First, because they represent more complex operations with inherently different outcomes, we excluded patients who had 2 or more different oncologic procedures on the same day. Second, because patients with synchronous malignancies or staged procedures are also often more complex and may only be performed by select centers with the appropriate resources, we excluded those who had more than one procedure ≤ 180 days apart. Finally, in order to improve statistical reliability, we also excluded hospitals with fewer than ten oncologic procedures during the period of interest. These exclusions accounted for only 1.7% of the entire patient cohort (n=6,504).

Finally, we excluded patients who received surgery at hospital that lacked CMS Star ratings.

Exposure Variables

For each patient, we first identified the hospital at which the patient had the extirpative cancer surgery. We then determined the CMS Star rating (i.e., 1,2,3,4 or 5-Star) and average annual cancer surgery volume for the hospital where the surgery occurred. The Star rating is a composite score comprised of 64 possible measures that are currently part of CMS' Hospital Compare program. The individual measures are assigned to 7 different categories: mortality, safety, readmissions, patient experience, care effectiveness, care timeliness, and efficient use of medical imaging. In order to receive a Star rating, a hospital has to report a minimum of 3 measures in at least 3 categories, including for one of the outcome categories (mortality, safety, and readmissions). CMS calculates a hospital's Star rating using only the measures on which the hospital chooses to report. The rating is publically available as part of CMS' overall Hospital Compare program(12).

For each hospital, we assigned the cancer surgery volume based on the cumulative number of cases for all 9 cancers included in our analysis, averaged over the 3 years of data in our cohort: bladder, colon, esophageal, kidney, liver, lung, ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancer. We classified hospitals into quintiles based on this volume measure (5 quintiles, 1=lowest volume, 5=highest volume), and assigned patients to the volume quintile of their treating hospital. We used overall cancer surgical volume for these analyses, rather than individual procedure volume, because we believe that this composite measure reflects the most policy-relevant volume metric, and one that could be considered reasonably analogous to the composite star ratings available from Hospital Compare.

Outcome measures

We measured 4 outcomes occurring within 30 days of the index cancer surgery: mortality, complications, prolonged length of stay, and hospital readmissions. Complications were defined using established methods, (13-15) and included infections, bleeding, gastrointestinal, neurologic, pulmonary, renal, cardiac, and others. Prolonged length of stay was defined as a hospital stay exceeding the 90th percentile for an individual procedure (11).

Statistical Analysis

We first performed univariate statistical analyses to compare patient and hospital characteristics across Star rating categories and surgical volume strata. We also used univariate statistical tests to evaluate the relationship between hospital Star ratings and cancer surgery volume quintile.

Next, we examined the association between cancer surgery outcomes and both Star rankings and surgical volumes. To do this, we fit multi-level logistic regression models, controlling for both patient (age, sex, race, and Elixhauser comorbidities) and hospital (hospital bed number, urban vs. rural location, region, and teaching status) characteristics.

We then used a graphical approach to compare how well Star ratings and surgical volume predict cancer surgery outcomes. We show how the outcomes compare not only across Star ratings and volume quintiles, but also across hospitals ranked into quintiles by the 4 cancer surgery outcomes. If the Star ratings or surgical volume predict cancer surgery outcomes, they will show similar patterns, graphically, to the cancer surgery outcomes.

To do this, we first divided hospitals into quintiles based on actual performance with each outcome measure. For example, a new hospital mortality rate quintile variable was created from the actual mortality rates for individual hospitals. By definition, this new measure represents the greatest possible relationship that could be attained between the outcome and any measurement rating system restricted to 5 quintiles and a linear line (e.g., Star rating or surgical volume); necessarily, therefore, this relationship represents a “gold standard” for comparing other hospital performance measures. Graphically, the slope of the line that is closest to the slope for the outcome measurement represents the better measure for predicting the outcome. A horizontal line would represent no association between the measurement strata and outcome (R2=0).

We repeated this analysis for the Star rating and surgical volume measurement categories for each cancer surgery outcome. Namely, we calculated mean hospital outcome by rating quintile, fit the best line through means, and calculated the slope of the line. The measurement (surgical volume or Star rating) with the steeper relative slope represents the measurement that, on average, better predicts the outcome.

Finally, we performed several sensitivity analyses to examine the robustness of our findings. In order to analyze case-mix differences, we calculated the share of high- (> 2 comorbidities) and low- risk (<=2 co-morbidities) patients in hospitals across Star ratings; computed the percent share of each cancer type that contributed to a hospital's total cancer surgery volume and compared this percent share across Star ratings; and we performed our primary analyses at the hospital level, which weighted each hospital's cancer specific outcome measures by the representative share of that cancer in our national sample. Second, to evaluate whether small numbers of procedures altered our findings, we repeated our primary analyses limiting hospitals to those with the highest cancer surgery volume (top 50% and 75%). Third, we examined outcome stability over time. Fourth, in order to evaluate the impact of reporting patterns on Star ratings, we compared the number of measurement categories that each hospital reported to the Hospital Compare program across Star ratings, and stratified outcomes by the number of reported measures among 5 Star hospitals. Fifth, in order to evaluate if our findings are clinically relevant in addition to policy relevant, we measured the correlation between overall cancer surgical volume quintile and cancer-specific surgical volume quintile.

All analyses were performed using STATA 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas), at the 5% significance level. The University of Michigan institutional review board deemed this study exempt from review.

Results

We identified 384,519 patients who underwent major cancer surgery for one of 9 cancers at 2,667 hospitals in the United States. Among this group, 365,752 patients were treated in 2,550 hospitals that were assigned a Star rating in Hospital Compare. Overall, five percent of hospitals were assigned a 1 Star rating, 23% 2 Stars, 46% 3 Stars, 25% 4 Stars, and 3% 5 Stars. Median annual cancer surgery surgical volume for each volume quintile was 5.0, 11.3, 22.1, 43.7, and 98.3, respectively.

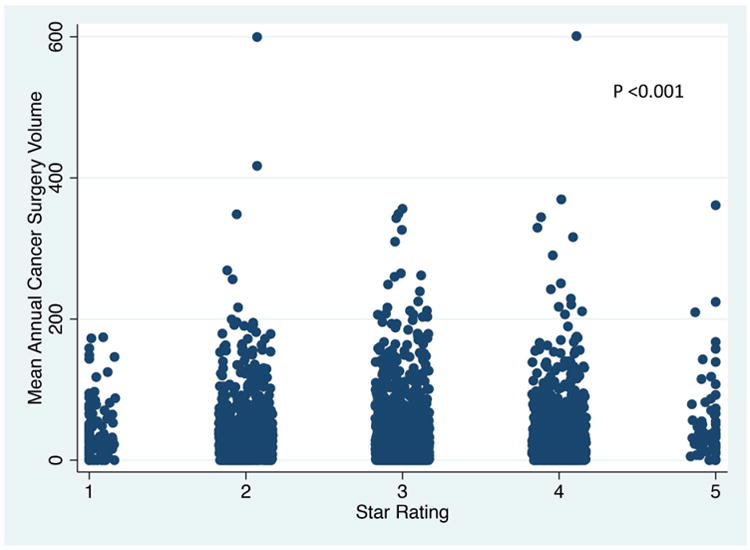

Table 1 presents differences in patient characteristics according to Star rankings and volume quintiles. As illustrated in Figure 1, Star rating had little to no association with surgical volume. Illustrating this point, twenty-four percent of 5 Star hospitals were high volume hospitals, while 16% of 1 Star hospitals were in the highest quintile for overall cancer surgery volume (p<0.001).

Table 1. Patient and Hospital Characteristics by A) CMS' Hospital Compare Star rating and b) Surgical volume quintile.

| A) Star rating | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Star | 2 Star | 3 Star | 4 Star | 5 Star | P-value | ||

| (Lowest) | (Highest) | ||||||

| Patient Characteristics | |||||||

| Age (mean) | 74.4 | 74.5 | 74.5 | 74.5 | 74.5 | 0.0327 | |

| Male Sex (%) | 56.5 | 57.9 | 57.5 | 58.4 | 62.2 | <0.001 | |

| Race (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Caucasian | 75.0 | 84.5 | 87.2 | 88.9 | 90.0 | ||

| African American | 17.5 | 10.6 | 7.4 | 5.8 | 5.1 | ||

| Other | 7.5 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 5.3 | 4.8 | ||

| Number of Comorbidities (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| 0 | 9.9 | 9.6 | 10.0 | 10.5 | 12.4 | ||

| 1 | 20.1 | 20.9 | 21.0 | 21.5 | 22.0 | ||

| 2 | 23.0 | 22.9 | 22.6 | 22.4 | 22.8 | ||

| 3 | 18.6 | 18.8 | 18.4 | 17.8 | 17.4 | ||

| ≥4 | 28.4 | 27.9 | 28.0 | 27.8 | 25.4 | ||

| Hospital Characteristics | |||||||

| Geographic region (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Northeast | 39.7 | 23.3 | 15.4 | 13.1 | 6.4 | ||

| Midwest | 11.6 | 15.5 | 24.8 | 40.0 | 42.9 | ||

| South | 31.4 | 43.0 | 38.0 | 28.2 | 33.3 | ||

| West | 17.4 | 18.1 | 21.8 | 18.7 | 17.5 | ||

| Number of beds (%) | 0.302 | ||||||

| <200 | 81.0 | 75.6 | 80.3 | 76.4 | 71.4 | ||

| 200-399 | 13.2 | 14.8 | 11.7 | 14.2 | 15.9 | ||

| 400-599 | 3.3 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 6.1 | 4.8 | ||

| >=600 | 2.5 | 4.7 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 7.9 | ||

| Hospital profit status (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| For-profit | 18.2 | 21.1 | 18.5 | 10.5 | 14.3 | ||

| Nonprofit | 50.4 | 64.3 | 69.4 | 78.2 | 77.8 | ||

| Public | 31.4 | 14.6 | 12.2 | 11.3 | 7.9 | ||

| Teaching hospital (%) | 59.5 | 41.8 | 30.7 | 30.0 | 33.3 | <0.001 | |

| Urban location (%) | 87.6 | 79.1 | 67.1 | 73.2 | 81.0 | <0.001 | |

| B. Surgical volume quintile | |||||||

| 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | P-value | ||

| (Lowest) | (Highest) | ||||||

| Patient Characteristics | |||||||

| Age (mean) | 77.1 | 76.3 | 75.5 | 74.8 | 74.0 | <0.001 | |

| Male Sex (%) | 48.3 | 51.1 | 53.9 | 56.5 | 60.1 | <0.001 | |

| Race (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Caucasian | 86.5 | 85.7 | 84.9 | 86.5 | 86.9 | ||

| African American | 7.9 | 9.1 | 9.2 | 8.0 | 7.9 | ||

| Other | 5.6 | 5.2 | 5.9 | 5.5 | 5.2 | ||

| Number of Comorbidities (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| 0 | 6.7 | 7.3 | 7.6 | 9.0 | 11.3 | ||

| 1 | 16.2 | 16.6 | 17.7 | 19.8 | 22.6 | ||

| 2 | 21.5 | 21.1 | 21.6 | 22.2 | 23.2 | ||

| 3 | 19.6 | 19.3 | 19.3 | 18.5 | 17.9 | ||

| ≥4 | 35.9 | 35.6 | 33.8 | 30.5 | 25.0 | ||

| Hospital Characteristics | |||||||

| Geographic region (%) | 0.025 | ||||||

| Northeast | 12.4 | 19.1 | 19.0 | 19.7 | 17.5 | ||

| Midwest | 32.2 | 26.0 | 25.2 | 23.8 | 24.2 | ||

| South | 36.1 | 36.9 | 36.4 | 43.2 | 38.0 | ||

| West | 19.4 | 18.0 | 19.4 | 22.4 | 20.3 | ||

| Number of beds (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| <200 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 83.9 | 6.1 | ||

| 200-399 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 16.1 | 50.0 | ||

| 400-599 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 25.4 | ||

| >=600 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 18.5 | ||

| Hospital profit status (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| For-profit | 22.0 | 18.6 | 22.4 | 13.2 | 8.9 | ||

| Nonprofit | 58.0 | 66.4 | 64.8 | 76.0 | 83.3 | ||

| Public | 20.0 | 15.1 | 12.8 | 10.8 | 7.9 | ||

| Teaching hospital (%) | 15.1 | 18.0 | 28.8 | 39.9 | 71.1 | <0.001 | |

| Urban location (%) | 37.3 | 58.7 | 78.2 | 91.9 | 97.6 | <0.001 | |

Figure 1. Relationship between CMS' Hospital Compare Star rating and average annual major cancer surgery volume among hospitals in the United States.

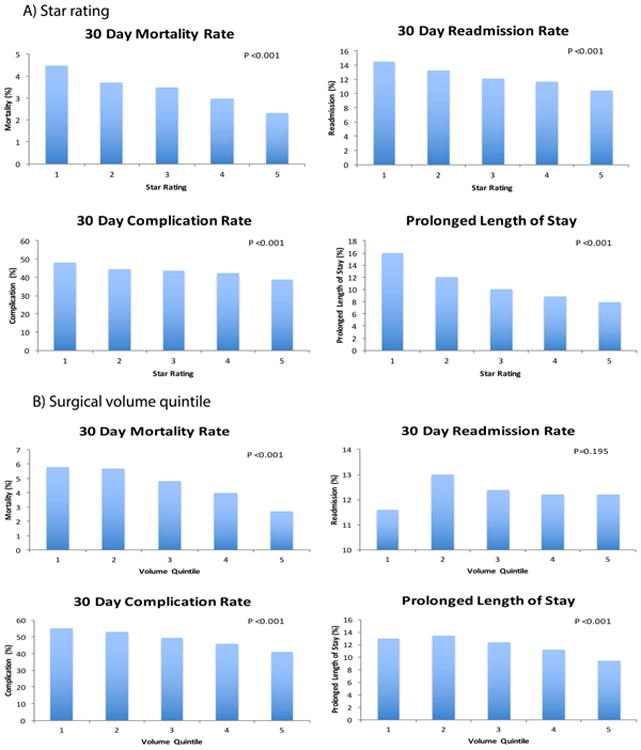

Across all hospitals and all procedures, the average frequency of our measured 30-day outcomes were as follows: 3.4% mortality rate, 43.7% complication rate, 12.3% readmission rate, and 10.3% prolonged length of stay. In univariate and multivariable analyses, both the Hospital Compare Star ratings and surgical volume quintiles were inversely associated with the occurrence of each short-term cancer surgery outcome (Table 2, Figure 2). After controlling for patient and hospital characteristics, 5 Star hospitals had a 2.3% mortality rate compared to a 4.5% rate for 1 Star hospitals, complication rates for 5- and 1- Star hospitals were 39% and 48% (p<0.001), readmission rates were 10% and 15% (p<0.001) and prolonged length of stay were 8% and 16% (p<0.001) for 5- and 1- Star hospitals, respectively. With respect to surgical volume, average mortality rate was 2.7% vs. 5.8% for the highest and lowest volume hospitals, respectively (p<0.001); rates of complications were 41% vs. 55% (p<0.001), readmissions were 12.2% vs. 11.6% (p=0.195); and prolonged length of stay was 9.4% vs. 13%, (p<0.001), for hospitals in the highest- and lowest- quintiles, respectively.

Table 2. Unadjusted overall cancer surgery outcomes by A) CMS' Hospital Compare Star Rating B) Surgical volume quintile.

| A) Star rating | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Star | 2 Star | 3 Star | 4 Star | 5 Star | P-value | |

| (Lowest) | (Highest) | |||||

| 30 Day Mortality Rate | 4.4 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 2.3 | <0.001 |

| 30 Day Complication Rate | 47.1 | 44.5 | 43.6 | 43.1 | 39.3 | <0.001 |

| 30 Day Readmissions | 14.5 | 13.2 | 12.1 | 11.6 | 10.3 | <0.001 |

| Prolonged Length of Stay | 14.7 | 11.7 | 10.0 | 8.9 | 7.7 | <0.001 |

| B) Surgical volume quintile | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | P-value | |

| (Lowest) | (Highest) | |||||

| 30 Day Mortality Rate | 5.8 | 5.6 | 4.8 | 4.0 | 2.7 | <0.001 |

| 30 Day Complication Rate | 55.0 | 52.8 | 49.7 | 45.9 | 40.7 | <0.001 |

| 30 Day Readmissions | 11.6 | 13.0 | 12.4 | 12.2 | 12.3 | 0.018 |

| Prolonged Length of Stay | 13.1 | 13.6 | 12.6 | 11.1 | 9.2 | <0.001 |

Figure 2. Adjusted* overall cancer surgery outcomes by A) CMS' Hospital Compare Star Rating B) Surgical volume quintile.

*Models adjusted for age, sex, race, comorbidities (using the Elixhauser method), hospital bed number, urban vs. rural location, region, and teaching status

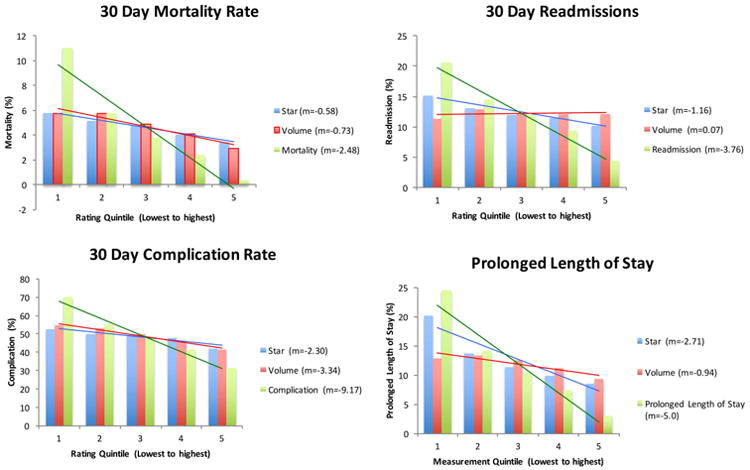

Figure 3 presents a comparison of the performance of Star ratings and surgical volume for predicting each of the cancer surgery outcomes. For 30-day mortality, the line fit to actual mortality quintiles has a slope of -2.48. This is in comparison to slopes of -0.58 for Star rating and -0.73 for surgical volume, suggesting that, on average, surgical volume and Star rating are similarly associated with mortality rate. We observed a comparable relationship for complication rate (Figure 3). This is in contrast to the slopes for readmission rate and prolonged length of stay, which suggest a stronger relationship with Star rating than with surgical volume.

Figure 3. Comparison of goodness-of-fit lines for CMS' Hospital Compare Star rating and cancer surgery volume relative to actual measured outcomes.

m = slope of best-fit line

The bar graph presents the mean outcome by measurement quintile.The line is the best-fit line through the means. The slope of the line that is closest to the slope for the outcome measurement (green line) represents the better measure for predicting the outcome. A horizontal line signifies no association.

Our sensitivity analyses identified no substantive changes to our principal findings. In our examination of hospital reporting and Star rating, 95% of hospitals reported either 6 or 7 measures, and there was a similar share of hospitals across Star categories that reported on the full 7 measures (89% for 1 Star vs. 84% for 5 Star hospitals). Among 5 Star hospitals, mean mortality, complication rate, and prolonged length of stay were highest for those reporting 3 outcome measures (the maximum allowable). Readmission rates were highest among hospitals reporting 2 outcome measures. Lastly, our analysis of the correlation between overall cancer surgical volume and cancer-specific volume demonstrated that cancer-specific volume is at least moderately correlated with overall cancer surgery volume for 7 of 9 cancers (Supplementary Table 1).

Discussion

Across a national sample of hospitals in the United States, we observed no association between CMS Hospital Compare Star ratings and annual cancer surgery volumes. However, higher Star ratings and larger surgical volumes were both associated with better short-term cancer surgery outcomes including lower rates of mortality, complications, readmissions, and prolonged length of stay. On average, surgical volume and Star rating were similarly correlated with mortality and complication rates, while Star rating had a stronger relationship with readmissions and prolonged length of stay. Collectively, these findings suggest that in the absence of other information, Star rating may be useful to help patients select a hospital for major cancer surgery, but more research is needed before these ratings can supplant surgical volume as a measure of surgical quality.

Our findings are consistent with previous work that has convincingly demonstrated a strong association between higher surgical volumes and better short- and long-term outcomes after major cancer surgery (16-19). Importantly, however, our observation that there is little, if any, correlation between Star rating and surgical volume for cancer surgery indicates that the Hospital Compare measure cannot be used as a publically available proxy for case volume. In other words, choosing a hospital with a high Star rating does not mean that a patient is selecting a high volume facility.

At the same time, we also identified a significant, inverse association between hospital Star ratings and short-term cancer surgery outcomes. This is a new finding and, in many ways, discordant with previous literature demonstrating inconsistencies amongst differing public reporting systems(9). Moreover, despite the potentially important implications of this finding for patients seeking cancer care; many have criticized the methodology used to create the Star ranking as both flawed and excessively opaque (2, 20-22).

In this context, there are several potential reasons for the observed association between Star rating and short-term cancer surgery outcomes that need to be addressed before Star ratings can supplant surgical volume as a measure of surgical quality. Included among these is the possibility that Star rankings will prove to be an accurate measure of hospital performance with major cancer surgery. However, alternative explanations must also be considered. Although we controlled for measurable patient co-morbidities, and carefully assessed case mix differences between the hospitals, it remains possible that the observed association reflects residual unmeasured differences in cancer severity or comorbidity among patients in the different Star rating categories. Our finding could also reflect a tautological relationship (i.e., a finding that is true because of the way it was conceived) to the extent that some of the outcomes we measured (e.g., readmissions) are also used to assign Star ratings in the first place. While it is difficult to empirically examine this concern, it is worth noting that the Hospital Compare methodology does not include any cancer-specific quality measures. Instead, the Hospital Compare methodology predominately reflect outcomes, processes and satisfaction with care for cardiac and pulmonary disease, and stroke. In fact, only 9 out of 64 possible measures contributing to the Star ratings could directly apply to patients undergoing major cancer surgery, the majority of which would be demonstrated in our complication outcome.

Finally, the observed association could also reflect the effect of hospitals with small case numbers or hospitals that “gamed” the Star rating system by reporting fewer measures (2). While valid, these concerns are mitigated by findings from our sensitivity analyses demonstrating no differences in our findings after excluding hospitals with low surgical volumes, as well as the findings that 95% of hospitals reported 6 or 7 measures, and that the proportion of hospitals reporting on all 7 measures was similar across rating categories (89% for 1 Star vs. 84% for 5 Star hospitals). Moreover, among hospitals with a 5 Star rating, those reporting the maximum number of outcome measures (3) had higher mortality rates, higher complication rates and increased length of stay compared to those reporting fewer measures, which is counter to the argument that “gaming” is occurring.

Our study has several limitations. First, we only examined short-term cancer surgery outcomes for nine types of cancer. As a result, our findings may not apply for other outcomes and tumors. That being said, the cancer sites included in our analysis comprise about 46% of the estimated newly diagnosed invasive cancers in 2016 in the United States (23). Second, while we are equating the outcomes measured in this analysis with quality of care for cancer surgery, there are obviously many other measures that could be considered, including longer-term or patient reported outcome measures. It is also true, however, that the outcomes assessed herein can be defined and measured accurately using claims data, and that they are widely used to measure and compare surgical quality. Third, the care delivered occurred prior to the Star rating. However, CMS devised the Star rating system based on previous years' measures and our sensitivity analyses demonstrated that outcomes did not vary over time. Fourth, while we excluded some patients undergoing cancer surgery to increase generalizability and statistical reliability, this step may result in a biased sample. However, given the very small proportion of cases (1.7% of the total sample) affected by our exclusion criteria, the implications for our overall findings are likely limited. Last, we used overall surgical volume when one could argue that the more clinically relevant measure is cancer-specific volume. Nonetheless, we selected overall volume because it is more consistent with evaluating the hospital as a whole and comparable to the Five Star Hospital Compare system. Furthermore, our sensitivity analysis indicated that cancer-specific volumes correlated fairly well to overall cancer surgical volumes.

These limitations notwithstanding, our findings have important implications for patients, policymakers, payers, and hospital administrators. For patients, our analyses support using surgical volume, when available, as a guide for choosing where to have major cancer surgery. Our findings also suggest a potential role for the Hospital Compare Star rankings; however, given the preliminary nature of this measure, surgical volume currently remains a more acceptable metric of a hospital's average short- and long- term cancer surgery outcomes.

For CMS policymakers, our findings do suggest that Star ratings may capture real differences between hospitals for cancer surgery outcomes. Nevertheless, important questions still remain about how hospitals gets into one category versus another, about the opacity of the measurement methodology, and about the extent to which reporting differences influence a hospital's rating. Thus, while our findings do provide support for additional assessment of these measures, several concerns must be addressed before the Star rating can be viewed as an actionable and reliable measure of quality. An important next step would be to analyze how the measure performs for disease states (e.g., gastrointestinal bleeds) that are far removed from the conditions contributing to the measure. Finally, because our findings suggest that Star rankings may have some validity as a hospital quality measure, hospital administrators may view these results as additional motivation to measure and improve performance on the various processes and outcomes that collectively yield the Hospital Compare Star measure.

Moving forward, additional research needs to be performed on case-mix differences, tautology, reporting bias, and other procedures and diagnoses. It will also be important to examine the stability of this measure over time, and its relationship with other measures of cancer care quality. Thus, while the Hospital Compare Star rating appears to correlate with short-term cancer surgery outcomes, more evaluation is required before it can be used to make selecting a hospital for cancer surgery any easier.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1: Correlation between cancer surgical volume and cancer-specific volume

Acknowledgments

Funding: This project was supported by the National Cancer Institute: (1-R01-CA-174768-01-A1 to David C. Miller and Deborah R. Kaye 5-T32-CA-180984-03).

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions: DRK: Conception, design, data analysis, interpretation, writing, and review; ECN: Conception, design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript review; CE: Conception, design, data analysis, interpretation, writing, and review; ZE: Data analysis, interpretation, and review; JMD: design, data interpretation, review; LAH: design, data interpretation, review; DCM: Conception, design, data analysis, interpretation, writing, and review

References

- 1.Pronovost PJ. Why Surgical Volumes Should Be Public. [Accessed: November 2016];2016 Available at: http://health.usnews.com/health-news/blogs/second-opinion/articles/2016-11-18/why-surgical-volumes-should-be-public?src=usn_tw.

- 2.Xu S, Grover A. CMS' Hospital Quality Star Ratings Fail to Pass the Common Sense Test. [Accessed: November 2016];Health Affairs Blog: Health Affairs. 2016 Nov; Available at: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/11/14/cms-hospital-quality-star-ratings-fail-to-pass-the-common-sense-test/

- 3.@krchhabra. “Reporting surgical volumes would be more useful & less misleading than “outcomes”/star ratings”. Twitter feed. 2016 Nov 27; 10:12 AM. Available at: https://twitter.com/krchhabra/status/802938217666408448.

- 4.@RAdamsDudleyMD. “More evidence of assoc bw social factors & hosp ratings: hosps in cities w stressed out populations get fewer stars”. Twitter feed. 2016 Nov; Available at: https://twitter.com/search?q=%40RAdamsDudleyMD.%20%22More%20evidence%20of%20assoc%20bw%20social%20factors%20%26%20hosp%20ratings%3A%20hosps%20in%20cities%20w%20stressed%20out%20populations%20get%20fewer%20stars&src=typd.

- 5.Goodrich K, Conway P. CMS Hospital Star Ratings First Step in Effort to Improve Quality Measures. AAMC News: Association of American Medical Colleges; Oct 4, 2016. [Accessed: Oct 2016]. Available at: https://news.aamc.org/patient-care/article/cms-star-ratings-effort-improve-quality-measures. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Comarow A. FAQ: How and Why We Rank and Rate Hospitals. [Accessed: Oct 2016];US News and World Report Best Hospitals: US News and World Report. 2016 Aug 11; Available at: http://health.usnews.com/health-care/best-hospitals/articles/faq-how-and-why-we-rank-and-rate-hospitals.

- 7.Merrill AL, Jha AK, Dimick JB. Clinical Effect of Surgical Volume. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374(14):1380–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMclde1513948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. First release of the overall Hospital Compare Quality Star Rating on Hospital Compare. [Accessed: August 2016];2016 Jul 27; Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2016-Fact-sheets-items/2016-07-27.html.

- 9.Austin JM, Jha AK, Romano PS, et al. National hospital ratings systems share few common scores and may generate confusion instead of clarity. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2015;34(3):423–30. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sternberg S. Hospitals Move to Limit Low-Volume Surgeries. [Accessed August 2016];US News and World Report. 2015 May 19; Available at: https://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2015/05/19/hospitals-move-to-limit-low-volume-surgeries.

- 11.Herrel LA, Norton EC, Hawken SR, Ye Z, et al. Early impact of Medicare accountable care organizations on cancer surgery outcomes. Cancer. 2016;122(17):2739–46. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Datasets | Data.Medicare.gov [Internet] [cited July 25, 2016];2016 Available from: https://data.medicare.gov/data/hospital-compare.

- 13.Iezzoni LI, Mackiernan YD, Cahalane MJ, et al. Screening inpatient quality using post-discharge events. Medical care. 1999;37(4):384–98. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199904000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osborne NH, Nicholas LH, Ryan AM, et al. Association of hospital participation in a quality reporting program with surgical outcomes and expenditures for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2015;313(5):496–504. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan HJ, Norton EC, Ye Z, et al. Long-term survival following partial vs radical nephrectomy among older patients with early-stage kidney cancer. JAMA. 2012;307(15):1629–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finks JF, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD. Trends in Hospital Volume and Operative Mortality for High-Risk Surgery. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364(22):2128–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1010705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morche J, Mathes T, Pieper D. Relationship between surgeon volume and outcomes: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Systematic reviews. 2016;5(1):204. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0376-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trinh QD, Bjartell A, Freedland SJ, et al. A systematic review of the volume-outcome relationship for radical prostatectomy. European urology. 2013;64(5):786–98. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, et al. Surgeon Volume and Operative Mortality in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349(22):2117–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MEDPAC. RE: Hospital Star Rating System Letter to: Andrew Slavitt, Acting Administrator for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed: October 2016];2016 Sep 22; Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/comment-letters/20160922_hospitalstarratings_medpac_comment_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

- 21.MacLean C, Shapiro L. Does the Hospital Compare 5-Star Rating Promote Public Health. [Accessed: October 2016];Health Affairs Blog: Health Affairs. 2016 Sep 8; Available at: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/09/08/does-the-hospital-compare-5-star-rating-promote-public-health/

- 22.Bilimoria KY, Barnard C. The New CMS Hospital Quality Star Ratings: The Stars Are Not Aligned. JAMA. 2016;316(17):1761–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.13679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2016;66(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: Correlation between cancer surgical volume and cancer-specific volume