Abstract

Context

Previous research has identified a large unmet need in provision of specialist-level palliative care services in the hospital. How much of this gap is filled by primary palliative care provided by generalists or non-palliative specialists has not been quantified. Estimates of racial and ethnic disparities have been inconsistent.

Objectives

1) To estimate primary and specialty palliative care delivery and to measure unmet needs in the inpatient setting and 2) to explore racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care delivery.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional, retrospective study of 55,658 adult admissions to two acute care hospitals in the Bronx in 2013. Patients with palliative care needs were identified by criteria adapted from the literature. The primary outcomes were delivery of primary and specialist-level palliative care.

Results

18.5% of admissions met criteria for needing palliative care. Of those, 18% received specialist-level palliative care, an estimated 30% received primary palliative care, and 37% had no evidence of palliative care or advance care planning. Black and Hispanic patients were not less likely to receive specialist-level palliative care (adjusted OR black patients=1.18, 95% CI 0.98, 1.42; adjusted OR Hispanic patients=1.24, 95% CI 1.04, 1.48), but they were less likely to receive primary palliative care (adjusted OR black patients= 0.41, 95% CI 0.20, 0.84; adjusted OR Hispanic patients=0.48, 95% CI 0.25, 0.94).

Conclusions

Even when considering primary and specialty palliative care, hospitalized patients have a high prevalence of unmet palliative care need. Further research is needed understand racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care delivery.

Keywords: Healthcare Disparities, Palliative Care, Health Services Research, Health Communication, Hospital Medicine

Introduction

Despite more than a decade of rapid expansion of palliative care services, many patients still have unmet palliative care needs.1,2 Although hospice use is increasing and death in acute care hospitals is decreasing, admissions to the hospital remain common in the last months of life.3 Addressing palliative care needs in the acute care setting remains an important goal.

With the aging of the population and a more recent recognition of the need to introduce advance care planning and palliative care earlier in the disease process,4,5 it is clear that the specialty palliative care workforce is inadequate to address all of the palliative needs of the U.S. population.6 Recently, there have been calls to increase provision of primary palliative care, defined as palliative care delivered by clinicians without specialty training in palliative care.7 Timely communication should occur during inpatient stays when a change in condition necessitates initiating or revisiting the goals of care. Seriously ill hospitalized patients and families consistently rank effective communication and shared decision-making among their top priorities.8 However, the quantity, quality and type of communication received in the inpatient setting remains very poor.9 Primary palliative care delivered by generalist and non-palliative care specialist clinicians could improve these patient and family experiences. However, no previous studies have quantified provision of primary palliative care in the acute care setting. It is important to know how much primary palliative care is being provided to quantify the remaining unmet needs of these patients.

Black and Hispanic patients enroll in hospice at lower rates compared to white patients.10-14 However, estimates of disparities in palliative care delivery outside of the hospice setting are scarce.14 One study of hospitalized patients with metastatic cancer found that there were no differences in rates of palliative care consultation between white and Hispanic patients, and that black patients were more likely to receive an inpatient palliative care consultation compared to white patients.17 Another study showed no racial or ethnic disparity in palliative care inpatient unit admission or hospice discharge for patients who died after admission for acute neurovascular events.18 These studies suggest that the availability of specialty palliative care in the inpatient setting may mitigate some racial and ethnic disparities in access to these services during admissions. One small chart review study at a Veterans Affairs Hospital showed similar rates of advance care planning by primary teams across racial and ethnic groups.19 Based on this literature, we hypothesized that rates of palliative care consultation and primary palliative care would be similar across racial and ethnic groups. This study aimed to estimate primary and specialty palliative care delivery in the inpatient setting and to explore racial and ethnic differences in palliative care delivery.

Methods

Study Design

This was a cross-sectional, retrospective study of data extracted from our institution's electronic medical records (EMR). This study was conducted as a secondary analysis of data generated by the APPROVE study (National Institutes of Health NHLBI project # UH3HL125119-02, PI M. Gong) of early identification of patients at risk for clinical deterioration or death. Data including laboratory, radiology, and clinical findings, hospital mortality, interventions such as, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, vasopressor use and mechanical ventilation, along with demographic data about the patient were abstracted from a clinical data warehouse (EMR replica) and directed to an identity-based encryption server. The bioinformatics team then extracted clinical data from this server. Additional data on palliative care consultation, admission to the palliative care inpatient unit, hospice discharge, nursing home residence prior to admission, admitting service and major comorbid conditions using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes were extracted from a data repository of Montefiore's Clinical Information System using health care surveillance software (Clinical Looking Glass™; Emerging Health Information Technology, Yonkers, NY) and from chart review. The data were validated with in-depth manual chart review of a random sample of patients. This study reviewed by the Montefiore/Albert Einstein College of Medicine IRB. Written informed consent was waived.

Setting

Montefiore Health System has a long-standing palliative care consultation service, which serves three of the acute care hospitals in the network and inpatient unit located within the largest of the three. The service consists of a racially and ethnically diverse interdisciplinary team of clinicians with more than a decade of experience providing end-of-life care to patients in our urban, low-income, mainly minority population.20,21

Patients

All admissions to Weiler and Moses Hospitals of the Montefiore Medical Center during the calendar year 2013 were included in the analysis. Together these hospitals provide just over 1,000 beds to a diverse population of patients in the Bronx, and >55,000 annual admissions.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Admissions were included if the patient was ≥ 18 years old on the day of admission. Peri-partum, psychiatry and ambulatory surgery admissions were excluded. For the determination of palliative care delivery, the analysis was restricted to admissions with a length of stay of at least 3 days, based on previous literature.22

Study Definitions

The definition of patients with palliative care needs was developed from review of the palliative care literature and review of the literature on mortality prediction.23-30 Criteria used in the literature have been developed by expert opinion and chart review to identify patients with serious illness, high risk of death, high risk of poor functional outcome, and a poor burden/benefit ratio for aggressive medical care. Criteria were adapted for this study for critically ill patients cared for in or away from the intensive care unit by considering vasopressor use and mechanical ventilation separately from ICU stay (Table 1).31 Major comorbidities included malignant neoplasm, heart disease, HIV/AIDS, cerebrovascular disease, renal disease, liver disease, respiratory disease and neurodegenerative disease. ICD-9 codes used to define major comorbidities are listed in the Appendix. To examine the misclassification rate of these criteria for palliative care needs, a random subset of patients identified with palliative care needs were reviewed by an expert in palliative care (E.C.) to confirm the presence of palliative care communication needs, defined as: confirmation or clarification of goals of care with the patient and/or family would be appropriate during the hospitalization given the underlying illness and acute changes in condition.

Table 1. Criteria used to define palliative care needa.

| Criteria for Palliative Care Need |

|---|

|

CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation, ICU = intensive care unit and LOS = hospital length of stay. Multisystem organ failure was defined as three or more of the following: 1) PaO2/FiO2 < 3000, 2) platelet count < 10,000/mm3, 3) increase in creatinine > 2mg/dl during admission, 4) increase in total bilirubin > 2mg/dl during admission, or 5) use of vasopressors.

Evidence of specialist-level palliative care services included documentation of a palliative care consult visit during admission or transfer to the hospital's inpatient palliative care unit. The estimate of primary palliative care services was based on an in-depth chart review conducted of a randomly selected sample of 400 admissions that met criteria for palliative care need. We focused on primary palliative care delivery of end-of-life communication and advance care planning, rather than on symptom management. Evidence of primary palliative care was based on documentation of patient and/or family discussion in the chart. Race and ethnicity were extracted from pre-determined categories in the electronic health record. These are based on the U.S. Census Bureau racial and ethnic categories.

Statistical Analysis

The admission, rather than the patient, was used as the unit of analysis because palliative care needs of individuals can be admission-specific. Descriptive statistics were used to present baseline characteristics. Proportions of patients with a palliative care need, and proportion of patients with a need that received palliative care specialist-level services and primary palliative care were reported. Black, Hispanic and white patients were compared on demographic characteristics, health process variables and measures of comorbidity and illness severity using t-tests for continuous variables and χ2-tests for dichotomous variables. Potential confounders between race and ethnicity and provision of palliative care were considered for inclusion in logistic regression models. Our center is a regional referral center and admissions to specialty services are likely to be from a larger geographic region with a different ethnic and racial makeup, and services differ in their propensities for utilization of palliative care.32 Whether the patient was on a teaching (housestaff) service or a non-teaching (physician assistant) service was considered. Different front-line providers may have different patterns of referral and provision of palliative care and our preliminary work indicated that race and ethnicity of patients on teach and non-teach services ware different. In addition, differences in patient age and underlying comorbidity were examined. Palliative care is differentially utilized depending on diagnoses.33 The SOFA score, as a measure of illness severity, and healthcare utilization variables such as nursing home residence, hospital length of stay and duration of mechanical ventilation were included because these factors were hypothesized to be potentially related to both palliative care provision and race and ethnicity. To evaluate associations between racial and ethnic groups and provision of specialty-level or primary palliative care, logistic regression was used to model each outcome using race and ethnicity as the predictor variables and including all of the above potential confounders that were associated with the outcome at the 0.15 significance level in univariate analysis. Gender and age were forced into the model. Statistical analysis was conducted using statistical software (StataCorp. 2011. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

Based on previous literature on racial disparities in hospice care, we considered a 10% difference in proportion of patients receiving primary or specialist-level palliative care to signify a disparity.14,15,34 We estimated that at least 217 patients would need to be included in each group to obtain 80% power to find a statistically significant difference at the α=0.05 level. This study was powered to detect disparities in specialist-level palliative care determined by extraction from the EMR.

Results

Estimates of Specialty-Level Palliative Care from EMR Database

Of the 58,775 admissions to Montefiore Medical Center in the year 2013, 3,025 peri-partum and ambulatory surgery admissions were excluded, as well as 92 admissions that the researchers were unable to link across key institutional databases, leaving 55,678 admissions for analysis. Demographic characteristics are shown in Table 2. Using the criteria outlined above, we found that 18.5% of admissions met criteria for palliative care need. Black and Hispanic patients were significantly less likely to have a palliative care need compared with white patients (unadjusted OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.71, 0.79 and unadjusted OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.60, 0.67).

Table 2. Characteristics of non-peri-partum, nonsurgical adult admissions at Montefiore Medical Centera.

| Baseline Characteristic | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 55,658 | ||

| Male | 22,241 | 40 | |

| Hispanic | 23,602 | 42 | |

| Race | |||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 18,335 | 33 | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 10,838 | 19 | |

| More than one race | 20,496 | 37 | |

| Other/unknown | 6,989 | 11 | |

| Age, mean ±SD | 59.3 ± 0.08 | ||

| Age ≥80 | 9,163 | 16 | |

| Nursing home resident prior to admission | 1,807 | 3.2 | |

| ICU stay after LOS ≥ 10 days | 410 | 0.7 | |

| MV after LOS ≥ 10 days | 263 | 0.5 | |

| Vasopressor use after LOS ≥ 10 days | 268 | 0.5 | |

| Stage IV malignancy | 2,039 | 3.7 | |

| ICU stay > 1 month | 43 | 0.1 | |

| ICU stay > 14d | 286 | 0.5 | |

| MV > 1 month | 211 | 0.4 | |

| MV >14 d | 474 | 0.9 | |

| ≥ 2 ICU stays during same admission | 151 | 0.3 | |

| Hospital stay ≥ 30 days | 997 | 1.8 | |

| ICH with MV | 146 | 0.3 | |

| CPR performed during admission | 419 | 0.8 | |

| Inpatient death | 1,298 | 2.3 | |

| Palliative care consult | 2,043 | 3.7 | |

| Major comorbidities | |||

| Respiratory disease | 18,178 | 33 | |

| Malignant neoplasm | 6,803 | 12 | |

| Heart disease | 16,073 | 29 | |

| Renal disease | 15,404 | 28 | |

| Neurologic disease | 4,843 | 9 | |

| Dementia | 1,474 | 2.7 | |

| Liver disease | 3,710 | 6.7 | |

| HIV/AIDS | 1,948 | 3.5 | |

| 2 or more major comorbidities | 20,144 | 36 | |

| Multisystem organ failure ≥ 3 systems | 1,621 | 2.9 | |

| Hospice discharge | 533 | 0.96 | |

| Transfer to palliative care unit | 317 | 0.6 | |

| Palliative care/EOL discussion needb | 10,303 | 18.5 |

EOL = End of life, CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation, MV = mechanical ventilation, ICU = intensive care unit, DNR = do-not-resuscitate, DNI = do-not-intubate, ICH = intracranial hemorrhage.

Patients meeting at least one of the following criteria: 1. Inpatient death or CPR, 2. Nursing home resident prior to admission with 2 or more major comorbidities, 3. Age ≥ 80 and 2 or more major comorbidities, 4. ICU stay after hospital length of stay (LOS) ≥ 10 days, 5. Initiation of mechanical ventilation or vasopressors after LOS ≥ 10 days, 6. Stage IV malignancy, 7. ICU stay or mechanical ventilation > 14 days, 8. Hospital LOS ≥ 30 days, 9. Intracranial hemorrhage requiring mechanical ventilation, 10. More than one ICU stay during one admission, 11. Multisystem organ failure ≥ 3 systems.

The analysis of specialist palliative care delivery was restricted to the 8,301 patients with a palliative care need and a hospital LOS ≥ 3 days (Table 3). Of patients with needs, 1,484 or 18% received a palliative care consult during admission and 181 (2.2%) were transferred to the hospital's inpatient palliative care unit.

Table 3. Baseline characteristics and outcomes for the patients with potential palliative care needs and hospital length of stay ≥ 3daysa.

| Characteristic | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 8,301 | ||

| Male | 3, 515 | 42 | |

| Hispanic | 2,931 | 35 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 2,630 | 32 | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 2,357 | 28 | |

| More than one race | 2,583 | 31 | |

| Other/unknown | 731 | 8.8 | |

| Age, mean±SD | 75±15.3 | ||

| Criteria | 1. Inpatient death or CPR | 1,244 | 15 |

| 2. Nursing home resident prior to admission with 2 or more major comorbiditiies | 1,075 | 13 | |

| 3. Age ≥ 80 and 2 or more major comorbidities | 4,342 | 52 | |

| 4. ICU stay after LOS ≥ 10 days | 410 | 4.9 | |

| 5. Initiation of mechanical ventilation or vasopressors after LOS ≥ 10 days | 382 | 4.6 | |

| 6. Stage IV malignancy | 1,674 | 20 | |

| 7. ICU stay or mechanical ventilation > 14 days | 573 | 6.9 | |

| 8. Hospital LOS ≥ 30 days | 997 | 12 | |

| 9. ICH requiring mechanical ventilation | 127 | 1.5 | |

| 10. More than one ICU stay during one admission | 187 | 2.3 | |

| 11. Multisystem organ failure ≥ 3 systems | 752 | 9.1 | |

| Palliative care consult | 1,484 | 18 | |

| Hospice Discharge | 343 | 4.1 | |

| Transfer to IPU | 181 | 2.2 | |

| DNR order | 2,217 | 27 | |

| DNI order | 1,823 | 22 |

LOS= hospital length of stay, CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation, MV = mechanical ventilation, ICU = intensive care unit, DNR = do-not-resuscitate, DNI = do-not-intubate, ICH = intracranial hemorrhage, IPU=Inpatient Palliative Care Unit.

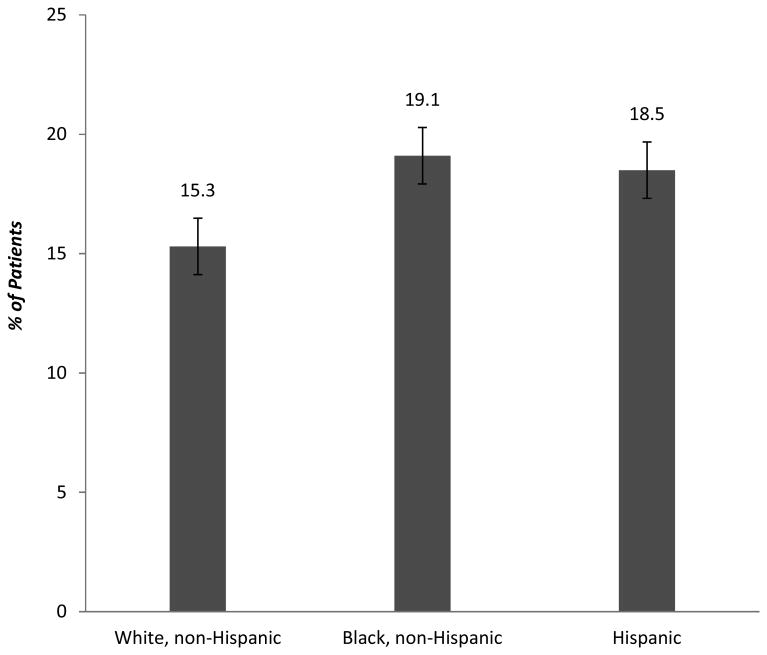

Of the patients meeting criteria for palliative care need, there were differences in demographic, clinical and hospital utilization variables by race and ethnicity: non-Hispanic black patients were more likely to be admitted from a nursing home, to have a malignancy and to have renal disease; non-Hispanic white patients were older, more likely to be male, to have respiratory disease and heart disease and less likely to have neurologic disease, HIV/AIDS and hospital length of stay ≥ 30 days; Hispanic patients were more likely to have dementia and liver disease (Table 4). 15.3% of non-Hispanic white patients, 19.1% of non-Hispanic black patients and 18.5% of Hispanic patients received palliative care specialty services. When adjusting for clinical and demographic variables including age, gender, nursing home residence, admitting service, physician assistant (non-teaching) service, and comorbidities, non-Hispanic black and Hispanic patients not less likely to receive specialist-level palliative care (adjusted OR black patients=1.18, p=0.084, 95% CI 0.98, 1.42; adjusted OR Hispanic patients=1.24, p=0.018, 95% CI 1.04, 1.49) (Figure 1, Table 5).

Table 4. Characteristics of patients with a palliative care need by racial or ethnic group (n=8,301)a.

| White, Non-Hispanic (Reference) | Black, Non-Hispanic | Hispanic | Other | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Characteristics N (%) | n=2,158 | n=2,548 | P-value | n=2,931 | P-value | N=664 | P-value |

| Age, mean±SD | 79.9±12.8 | 73.1±15.8 | <0.001 | 74.1 ±15.4 | <0.001 | 70.3±17.0 | <0.001 |

| Male | 1050 (48.7) | 968 (38.0) | <0.001 | 1187 (40.5) | <0.001 | 310 (46.7) | ns |

| NH resident | 244 (11.3) | 408 (16.0) | <0.001 | 370 (12.6) | =0.153 | 85 (12.8) | ns |

| Service | |||||||

| Medical | 1578 (73.1) | 1889 (74.1) | ns | 2160 (73.7) | ns | 392 (59.1) | <0.001 |

| Surgical | 319 (14.8) | 303 (11.9) | =0.004 | 337 (11.5) | =0.050 | 136 (20.5) | =0.001 |

| Neurology | 51 (2.3) | 50 (1.9) | ns | 47 (1.6) | =0.053 | 19 (2.9) | ns |

| Oncology | 90 (4.2) | 169 (6.6) | <0.001 | 178 (6.1) | =0.003 | 50 (7.5) | =0.001 |

| Gynecology | 29 (1.3) | 49 (1.9) | =0.123 | 48 (1.6) | ns | 33 (5.0) | <0.001 |

| Cardiology | 79 (3.7) | 59 (2.3) | =0.007 | 96 (3.3) | ns | 28 (4.2) | ns |

| PA service | 800 (37.1) | 564 (22.1) | <0.001 | 605 (20.6) | <0.001 | 112 (16.9) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory disease | 1246 (57.7) | 1328 (52.1) | <0.001 | 1606 (54.8) | =0.038 | 348 (52.4) | =0.016 |

| Malignancy | 603 (27.9) | 861 (33.8) | <0.001 | 862 (29.4) | ns | 208 (31.3) | =0.092 |

| Heart disease | 1414 (65.5) | 1369 (53.7) | <0.001 | 1590 (54.2) | <0.001 | 358 (53.9) | <0.001 |

| Renal disease | 1162 (53.8) | 1557 (61.1) | <0.001 | 1581 (53.9) | ns | 367 (55.3) | ns |

| Neurologic | 429 (19.9) | 586 (23.0) | =0.010 | 697 (23.8) | =0.001 | 139 (20.9) | ns |

| Dementia | 212 (9.8) | 228 (8.9) | ns | 393 (13.4) | <0.001 | 42 (6.3) | =0.006 |

| Liver disease | 135 (6.3) | 187 (7.3) | =0.143 | 268 (9.1) | <0.001 | 67 (10.1) | =0.001 |

| HIV/AIDS | 6 (0.3) | 78 (3.1) | <0.001 | 70 (2.4) | <0.001 | 16 (2.4) | <0.001 |

| SOFA ≥ 3 | 169 (7.8) | 216 (8.5) | ns | 255 (8.7) | ns | 112 (16.9) | <0.001 |

| LOS ≥ 30d | 181 (8.4) | 363 (14.2) | <0.001 | 354 (12.1) | <0.001 | 99 (14.9) | <0.001 |

| ICU LOS ≥ 15d | 65 (3.0) | 87 (3.4) | ns | 93 (3.8) | ns | 41 (6.2) | <0.001 |

| MV ≥ 15d | 99 (4.6) | 152 (6.0) | =0.037 | 167 (5.7) | =0.079 | 56 (8.4) | <0.001 |

| Hospital mortality | 284 (13.2) | 326 (12.8) | ns | 369 (12.6) | ns | 118 (17.8) | =0.003 |

| DNR or DNI order | 671 (31.1) | 604 (23.7) | <0.001 | 804 (27.5) | =0.005 | 181 (27.3) | =0.060 |

| Hospice referral | 96 (4.5) | 110 (4.3) | ns | 107 (3.7) | ns | 30 (4.5) | ns |

| Received specialty palliative care | 331 (15.3) | 486 (19.1) | =0.001 | 541 (18.5) | =0.003 | 152 (22.9) | <0.001 |

SOFA = sequential organ failure assessment, LOS= hospital length of stay, MV = mechanical ventilation, ICU = intensive care unit, PA= Physician Assistant, DNR = Do Not Resuscitate, DNI = Do No Intubate.

Fig 1.

Proportion of Patients with a Palliative Care Need Receiving Specialist-Level Palliative Care by Race and Ethnicity (n=8,301).

Table 5. Logistic regression analysis of specialty palliative care delivery (n=8,301)a.

| Independent Variable | Odds Ratio | Standard Error | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White, Non-Hispanic | reference | |||

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 1.18 | 0.11 | 0.98, 1.42 | =0.084 |

| Hispanic | 1.24 | 0.11 | 1.04, 1.49 | =0.018 |

| Other | 1.52 | 0.20 | 1.16, 1.97 | =0.002 |

|

| ||||

| Gender | 1.15 | 0.08 | 1.01, 1.32 | =0.038 |

| Age | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00, 1.01 | =0.152 |

| Hospital Mortality | 9.41 | 0.81 | 7.94, 11.1 | <0.001 |

| Hospital | 0.81 | 0.06 | 0.71, 0.93 | =0.002 |

| PA Service | 0.83 | 0.07 | 0.69, 0.98 | =0.033 |

|

| ||||

| Medical Service | reference | |||

| Surgical Service | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.18, 0.30 | <0.001 |

| Neurology Service | 0.74 | 0.19 | 0.44, 1.23 | =0.246 |

| Oncology Service | 0.58 | 0.08 | 0.44, 0.76 | <0.001 |

| Cardiology Service | 0.57 | 0.14 | 0.35, 0.91 | =0.020 |

| Gynecology Service | 0.52 | 0.12 | 0.33, 0.83 | =0.006 |

|

| ||||

| NH Resident | 0.84 | 0.10 | 0.66, 1.07 | =0.159 |

| SOFA3 | 0.64 | 0.09 | 0.49, 0.83 | =0.001 |

| Dementia | 0.84 | 0.11 | 0.65, 1.09 | =0.195 |

| Cancer | 4.14 | 0.35 | 3.51, 4.88 | <0.001 |

| Heart Disease | 0.97 | 0.07 | 0.83, 1.12 | =0.633 |

| Respiratory Disease | 1.14 | 0.08 | 0.98, 1.32 | =0.075 |

| Neurologic Disease | 1.51 | 0.14 | 1.26, 1.80 | <0.001 |

| Renal Disease | 0.91 | 0.07 | 0.78, 1.05 | =0.195 |

| Liver Disease | 1.36 | 0.16 | 1.08, 1.70 | =0.008 |

| HIV/AIDS | 1.31 | 0.27 | 0.88, 1.97 | =0.186 |

| Time on IMV | 1.03 | 0.00 | 1.02, 1.04 | <0.001 |

| LOS | 1.03 | 0.00 | 1.03, 1.04 | <0.001 |

| ICU stay >14 days | 1.31 | 0.01 | 0.02, 0.06 | <0.001 |

Hospital is an indicator of which of the two acute care hospitals the patient was admitted to, PA=Physician Assistant, NH=Nursing Home, HIV=Human Immunodeficiency Virus, AIDS=Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, LOS= hospital length of stay, IMV = invasive mechanical ventilation, ICU=intensive care unit.

Estimates of Primary Palliative Care and Advance Care Planning From Manual Chart Review

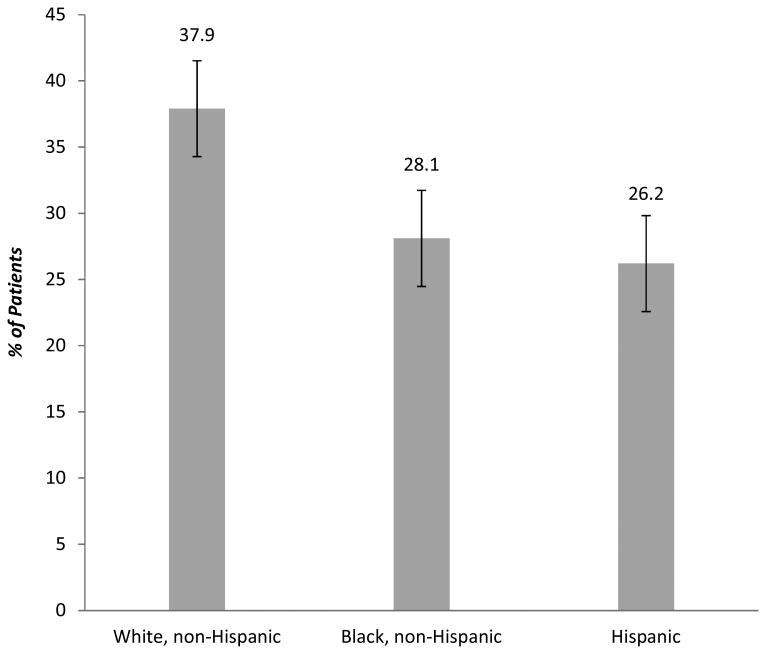

The final data set from the manual chart review included data from 401 admissions meeting criteria for palliative care needs. A total of 121 or 30.2% of admissions included documentation of a discussion with the patient or family about goals of care performed by clinicians not on the palliative care team. A higher proportion of non-Hispanic white patients had documentation of discussion with the patient and or family about goals of care by a clinician other than a palliative care specialist (37.9%) compared with non-Hispanic black (28.1%) and Hispanic (26.2%) patients (adjusted OR non-Hispanic black patients=0.41, p=0.015 95% CI 0.20, 0.84; adjusted OR Hispanic patients=0.48, p=0.032, 95% CI 0.25, 0.94) (Figure 2, Table 6).

Fig 2. Proportion of Patients with a Palliative Care Need Receiving Primary Palliative Care by Race and Ethnicity (n=401).

Table 6. Logistic regression analysis of primary palliative care delivery (n=401)a.

| Independent Variable | Odds Ratio | Standard Error | 95 % CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White, Non-Hispanic | reference | |||

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 0.41 | 0.15 | 0.20, 0.84 | =0.015 |

| Hispanic | 0.48 | 0.16 | 0.25, 0.94 | =0.032 |

| Other | 2.11 | 1.18 | 0.70, 6.34 | =0.182 |

|

| ||||

| Gender | 2.06 | 0.58 | 1.18, 3.57 | =0.010 |

| Age | 1.02 | 0.01 | 1.00, 1.04 | 0.043 |

| Hospital Mortality | 7.41 | 2.95 | 3.39, 16.2 | <0.001 |

| Hospital | 0.67 | 0.18 | 0.40, 1.14 | =0.138 |

| PA Service | 0.53 | 0.19 | 0.26, 1.05 | =0.069 |

|

| ||||

| Medicine Service | Reference | |||

| Surgical Service | 0.24 | 0.12 | 0.09, 0.62 | =0.003 |

| Neurology Service | 0.25 | 0.34 | 0.02, 3.44 | =0.302 |

| Oncology Service | 0.76 | 0.48 | 0.22, 2.60 | =0.662 |

| Cardiology Service | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.06, 2.55 | =0.319 |

| Gynecology Service | 0.71 | 0.78 | 0.08, 6.15 | =0.755 |

|

| ||||

| NH Resident | 2.03 | 0.85 | 0.90, 4.61 | =0.090 |

| SOFA3 | 1.29 | 0.79 | 0.39, 4.29 | =0.675 |

| Dementia | 1.09 | 0.50 | 0.44, 2.68 | =0.846 |

| Cancer | 2.31 | 0.81 | 1.16, 4.61 | =0.017 |

| Heart Disease | 1.43 | 0.41 | 0.82, 2.53 | =0.210 |

| Respiratory Disease | 0.76 | 0.21 | 0.44, 1.31 | =0.326 |

| Neurologic Disease | 2.15 | 0.75 | 1.08, 4.27 | =0.030 |

| Renal Disease | 1.35 | 0.38 | 0.77, 2.35 | =0.326 |

| Liver Disease | 1.02 | 0.47 | 0.41, 2.52 | =0.967 |

| HIV/AIDS | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.06, 3.85 | =0.506 |

| Time on IMV | 1.07 | 0.04 | 1.00, 1.14 | =0.049 |

| LOS | 1.03 | 0.01 | 1.01, 1.05 | =0.002 |

| ICU stay >14 days | 0.73 | 0.61 | 0.14, 3.79 | =0.708 |

Hospital is an indicator of which of the two acute care hospitals the patient was admitted to, PA=Physician Assistant Service, NH=Nursing Home, HIV=Human Immunodeficiency Virus, AIDS=Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, LOS= hospital length of stay, IMV = invasive mechanical ventilation, ICU=intensive care unit.

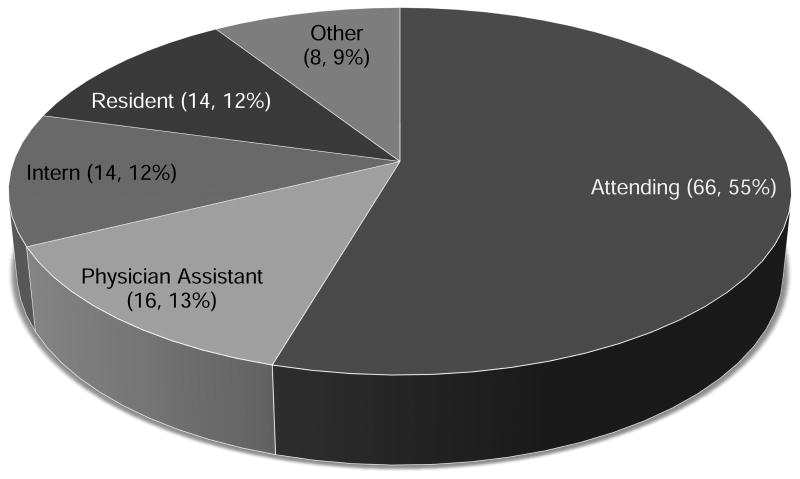

Most of the discussions were documented by the attending physician, but physician assistants, interns and residents documented almost half of these discussions (Figure 3). Of those admissions with a non-palliative care provider family discussion, 43.0% also had palliative care specialist involvement. A total of 149 or 37.2% of patients had no evidence of any palliative care end-of-life communication or advance care planning need met. In total, 172 (42.9%) of patients had a documented health care proxy on file, 12 (3.0%) had a living will on file and 10 (2.5%) had a MOLST form on file.

Fig 3. Provider Documenting Patient or Family Discussion (n, %).

Fifty-four charts of patients with palliative care needs were randomly selected for expert review. Only 2 (3.7%) of these admissions were deemed not appropriate for either primary or secondary palliative care during admission because the admission was uncomplicated and/or goals were clear prior to admission.

Discussion

This study provides the first estimate of primary palliative care delivered in the acute care setting. We found that about 30% of patients had a documented primary palliative care discussion in the chart and that 37% of patients with a palliative care need had no evidence of any palliative care or advance care planning services. This indicates that there remains a large unmet need for provision of palliative care communication to seriously ill patients in the hospital. Further work needs to be done to provide this service to all patients with a need. Strategies to improve provision of primary palliative care may include educational interventions and systems-based interventions such as developing cognitive prompts that can alert primary teams to palliative care needs.

This finding from an institution that serves a racially and ethnically diverse population, confirms estimates of the population of patients needing palliative care in less diverse settings.24-28,35 Recent studies estimated that between 19 and 26% of patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) met criteria for palliative care consultation.23,28 Most recently, Szekendi, et al. estimated that 19% of hospitalized patients had a palliative care need, and about 60% of these patients did not have their need met in the form of specialty-level palliative care services or referral.29 Delivery of specialist-level palliative care varied widely by site, ranging from only 12% to 90%. Other studies show that palliative care services are provided on an average of 4-5% of acute care admissions across the country, which also suggests a large unmet need.36

Further, we found intriguing differences in provision of primary and specialist-level palliative care by race and ethnic group. Specifically, primary teams were less likely to document discussions with black and Hispanic patients and their families but at least as likely to consult palliative care specialists to provide these services to them. We did not expect Hispanic patients to receive specialty level palliative care more often than white patients. Another study found that black patients were more likely to receive palliative care consultation the inpatient setting.17 These findings could be due to more complex needs of black and Hispanic patients, however, our analysis controlled for variables that would indicate complexity of care including comorbidities, measures of intensity of hospital care and acuity of condition.

The lack of primary palliative care for black and Hispanic patients was partially offset by the increase in referral to specialty palliative care services. These findings expand on and illuminate the findings of a previous study, which showed that despite disparities in hospice use, black patients were more likely to receive palliative care consultation services during hospitalization.17 It is reassuring that black and Hispanic patients are receiving the extra layer of support of specialty palliative care services in the hospital, and this could lead to better outcomes for these patients. However, lack of provision of generalist palliative care could cause delays in accessing palliative care. In addition, if the higher rate of referral to specialist-level palliative care is a result of lower comfort with providing primary palliative care, this may lead to poorer outcomes for black and Hispanic patients and increased, rather than decreased disparity in end of life care. As the population of patients with palliative care needs expands, it will be important for all clinicians to provide primary palliative care to meet population needs, and racial and ethnic disparities may widen. Barriers to providing this service to black and Hispanic patients should be investigated.

There are several possible explanations for the lower estimate of primary palliative care in black and Hispanic patients. Clinicians may not initiate conversations with black and Hispanic patients and their families due to implicit bias or they may not feel that they have the requisite skill set in cross-cultural communication. Alternatively, some literature suggests that black patients are more likely to request aggressive medical interventions at end of life,37 and physicians may therefore perceive these discussions to be unwanted. Another possible explanation is that clinicians are less likely to document discussions that do not lead to a change in management, which may be more likely for black and Hispanic patients. Language barriers may also play a role in provision of primary palliative care to Hispanic patients. Our institution is based primarily on hospitalist-housestaff and hospitalist-physician assistant models. Few private physicians follow their patients during admission, making racial and ethnic differences in continuity of care an unlikely explanation for the findings of this study.

Higher specialty referral rates for black and Hispanic patients may reflect lower comfort providing primary palliative care. However, it may also be reflective of an increased need for mediation when clinician and patient perception of the optimal care plan are discordant, as may happen when patients opt for more aggressive medical intervention at end of life. Further research that explores clinician's experience providing primary palliative care and reasons for specialty referral will be needed to distinguish these various explanations.

There are several limitations of this study. We focused on end of life communication and advance care planning. We did not attempt to estimate the need for or provision of advanced illness symptom management. Our estimate of palliative care need was based on data available in the medical record, and is likely to underestimate the palliative needs of patients with cancer or chronic illnesses that do not meet the severity criteria that we chose. In addition, we were limited to measuring discussions and advance directives that were documented in the medical record. It is likely that some discussions occurred that were not documented. Specifically, discussions that did not lead to a change in management or code status may have been less likely to be documented. Conversely, the definition of family discussion used in the chart review template was very liberal and we did not measure the quality of the discussion. Evidence of a family discussion was counted even for very brief documentation such as “code status was discussed with patient's wife.” We did not place restrictions on timing of documentation, e.g. for one patient, the only discussion documented in the chart occurred between episodes of cardiac arrest on the day the patient died.

This study was conducted at two acute care hospitals primarily serving racial and ethnic minority populations. This limits the generalizability of the findings. Another limitation relates to the way race and ethnicity are collected in our institution's electronic health record. The categories available mirror the U.S. Census categories of race and ethnicity. Our institution serves a multitude of different groups within each of the broad categories presented here, including African-Americans, Hispanic Americans, and African, Afro-Caribbean and Hispanic immigrants from many different countries. There are numerous individual and group variations in cultural norms and beliefs that we are unable to capture in a chart review. However, Montefiore received a Robert Wood Johnson grant from 2005-2008 for clinical QI projects (Expecting Success: Excellence in Cardiac Care). As a part of that grant, a significant effort was made to confirm race and ethnicity documentation in our EMR. Finally, there may be unmeasured variables, such as patient religiosity and family dynamics that could confound the relationship between race and ethnicity and provision of palliative care. However, patient's religious beliefs, social support systems and preferences around end of life care should be incorporated in primary palliative care discussions, rather than a barrier to conducting them. More in-depth analysis of the barriers to providing primary palliative care is needed.

Further studies should aim to improve the provision of primary palliative care in the acute care setting, particularly for racial and ethnic minority patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health NHLBI project # UH3HL125119-02 (M.N.G.) and R03 AG050927 (A.A.H.).

Appendix: ICD-9 Codes used to determine comorbidities

Malignant neoplasm

140, 140.1, 140.3, 140.4, 140.5, 140.6, 140.8, 140.9, 141, 141.1, 141.2, 141.3, 141.4, 141.6, 141.8, 141.9, 142, 142.1, 142.2, 142.8, 142.9, 143, 143.1, 143.8, 143.9, 144, 144.1, 144.8, 144.9, 145, 145.1, 145.2, 145.3, 145.4, 145.5, 145.6, 145.8, 145.9, 146, 146.1, 146.2, 146.3, 146.4, 146.6, 146.7, 146.8, 146.9, 147, 147.1, 147.2, 147.3, 147.8, 147.9, 148, 148.1, 148.2, 148.3, 148.8, 148.9, 149, 149.1, 149.8, 149.9, 150, 150.1, 150.2, 150.3, 150.4, 150.5, 150.8, 150.9, 151, 151.1, 151.2, 151.3, 151.4, 151.5, 151.6, 151.8, 151.9, 152, 152.1, 152.2, 152.3, 152.8, 152.9, 153, 153.1, 153.2, 153.3, 153.4, 153.5, 153.6, 153.7, 153.8, 153.9, 154, 154.1, 154.2, 154.3, 154.8, 155, 155.1, 155.2, 156, 156.1, 156.2, 156.8, 156.9, 157, 157.1, 157.2, 157.3, 157.4, 157.8, 157.9, 158, 158.8, 158.9, 159, 159.1, 159.8, 159.9, 160, 160.1, 160.2, 160.3, 160.4, 160.5, 160.8, 160.9, 161, 161.1, 161.2, 161.3, 161.8, 161.9, 162, 162.2, 162.3, 162.4, 162.5, 162.8, 162.9, 163.9, 164, 164.1, 164.2, 164.3, 164.8, 164.9, 165, 165.8, 165.9, 170, 170.1, 170.2, 170.3, 170.4, 170.5, 170.6, 170.7, 170.8, 170.9, 171, 171.2, 171.3, 171.4, 171.5, 171.6, 171.7, 171.8, 171.9, 171.9, 172, 172.1, 172.2, 172.3, 172.4, 172.5, 172.6, 172.7, 172.8, 172.9, 173, 173.01, 173.02, 173.09, 173.1, 173.11, 173.12, 173.19, 173.2, 173.21, 173.22, 173.29, 173.3, 173.31, 173.32, 173.39, 173.4, 173.41, 173.42, 173.49, 173.5, 173.51, 173.52, 173.59, 173.6, 173.61, 173.62, 173.69, 173.7, 173.71, 173.72, 173.79, 173.8, 173.81, 173.82, 173.89, 173.9, 173.91, 173.92, 173.99, 174, 174.1, 174.2, 174.3, 174.4, 174.5, 174.6, 174.8, 174.9, 175, 175.9, 176, 176.1, 176.2, 176.3, 176.4, 176.5, 176.8, 176.9, 179, 180, 180.1, 180.8, 180.9, 181, 182, 182.1, 182.8, 183, 183.2, 183.3, 183.4, 183.5, 183.9, 184, 184.1, 184.2, 184.3, 184.4, 184.8, 184.9, 185, 186, 186.9, 187.1, 187.2, 187.3, 187.4, 187.5, 187.6, 187.7, 187.8, 187.9, 188, 188.1, 188.2, 188.3, 188.4, 188.5, 188.6, 188.7, 188.8, 188.9, 189, 189.1, 189.2, 189.3, 189.4, 189.8, 189.9, 190, 190.1, 190.2, 190.3, 190.4, 190.5, 190.6, 190.7, 190.8, 190.9, 191, 191.1, 191.2, 191.3, 191.4, 191.5, 191.6, 191.7, 191.8, 191.9, 192, 192.1, 192.2, 192.3, 192.8, 192.9, 193, 194, 194.1, 194.3, 194.4, 194.5, 194.6, 194.8, 194.9, 195, 195.1, 195.2, 195.3, 195.4, 195.5, 195.8, 196, 196.1, 196.2, 196.3, 196.5, 196.6, 196.8, 196.9, 197, 197.1, 197.2, 197.3, 197.4, 197.5, 197.6, 197.7, 197.8, 198, 198.1, 198.2, 198.3, 198.4, 198.5, 198.6, 198.7, 198.81, 198.82, 198.89, 199, 199.1, 199.2, 200, 200.01, 200.02, 200.03, 200.04, 200.05, 200.06, 200.07, 200.08, 200.1, 200.11, 200.12, 200.13, 200.14, 200.15, 200.16, 200.17, 200.18, 200.2, 200.21, 200.22, 200.23, 200.24, 200.25, 200.26, 200.27, 200.28, 200.3, 200.4, 200.41, 200.42, 200.43, 200.44, 200.45, 200.46, 200.47, 200.48, 200.5, 200.51, 200.52, 200.53, 200.54, 200.55, 200.56, 200.57, 200.58, 200.6, 200.61, 200.62, 200.63, 200.64, 200.65, 200.66, 200.67, 200.68, 200.7, 200.71, 200.72, 200.73, 200.74, 200.75, 200.76, 200.77, 200.78, 200.8, 200.81, 200.82, 200.83, 200.84, 200.85, 200.86, 200.87, 200.87, 200.88, 201, 201.01, 201.02, 201.03, 201.04, 201.05, 201.06, 201.07, 201.08, 201.1, 201.11, 201.12, 201.13, 201.14, 201.15, 201.16, 201.17, 201.18, 201.2, 201.21, 201.22, 201.23, 201.24, 201.25, 201.26, 201.27, 201.28, 201.4, 201.41, 201.42, 201.43, 201.44, 201.45, 201.46, 201.47, 201.48, 201.5, 201.51, 201.52, 201.53, 201.54, 201.55, 201.56, 201.57, 201.58, 201.6, 201.61, 201.62, 201.63, 201.64, 201.65, 201.66, 201.67, 201.68, 201.7, 201.71, 201.72, 201.73, 201.74, 201.75, 201.76, 201.77, 201.78, 201.9, 201.91, 201.92, 201.93, 201.94, 201.95, 201.96, 201.97, 201.98, 202, 202.01, 202.02, 202.03, 202.04, 202.05, 202.06, 202.07, 202.08, 202.1, 202.11, 202.12, 202.13, 202.14, 202.15, 202.16, 202.17, 202.18, 202.2, 202.21, 202.22, 202.23, 202.24, 202.25, 202.26, 202.27, 202.28, 202.3, 202.4, 202.5, 202.6, 202.7, 202.71, 202.72, 202.73, 202.74, 202.75, 202.76, 202.77, 202.78, 202.8, 202.81, 202.82, 202.83, 202.84, 202.85, 202.86, 202.87, 202.88, 202.9, 202.91, 202.92, 202.93, 202.94, 202.95, 202.96, 202.97, 202.98, 203, 203.01, 203.02, 203.1, 203.11, 203.12, 203.8, 203.81, 203.82, 204, 204.01, 204.02, 204.1, 204.11, 204.12, 204.8, 204.81, 204.82, 204.9, 204.91, 204.92, 205, 205.01, 205.02, 205.1, 205.11, 205.12, 205.2, 205.21, 205.22, 205.3, 205.31, 205.32, 205.8, 205.81, 205.82, 205.9, 205.91, 205.92, 206, 206.01, 206.02, 206.1, 206.11, 206.12, 206.2, 206.21, 206.22, 206.8, 206.81, 206.82, 206.9, 206.91, 206.92, 207, 207.01, 207.02, 207.2, 207.21, 207.22, 207.8, 207.81, 207.82, 208, 208.01, 208.02, 208.1, 208.11, 208.12, 208.2, 208.21, 208.22, 208.8, 208.81, 208.82, 208.9, 208.91, 208.92, 209, 209.01, 209.02, 209.03, 209.1, 209.11, 209.12, 209.13, 209.14, 209.15, 209.16, 209.17, 209.2, 209.21, 209.22, 209.23, 209.24, 209.25, 209.26, 209.27, 209.29, 209.3, 209.31, 209.32, 209.33, 209.34, 209.35, 209.36, 209.7, 209.71, 209.72, 209.73, 209.74, 209.75, 209.79

Respiratory diseases

410, 415, 418.1, 465, 465.8, 465.9, 466, 466.11, 466.19, 480, 480.1, 480.2, 480.3, 480.8, 480.9, 481, 482, 482.1, 482.2, 482.31, 482.32, 482.39, 482.4, 482.41, 482.42, 482.49, 482.81, 482.82, 482.83, 482.89, 482.9, 483, 483.1, 483.8, 484.7, 484.8, 485, 486, 487, 487.1, 487.8, 488.01, 488.02, 488.09, 488.11, 488.12, 488.19, 488.81, 488.82, 488.89, 490, 491, 491.1, 491.2, 491.21, 491.22, 491.8, 491.9, 492, 492.8, 493, 493.01, 493.02, 493.1, 493.11, 493.12, 493.2, 493.21, 493.22, 493.81, 493.82, 493.9, 493.91, 493.92, 494, 494.1, 496, 514, 517.1, 518.51, 518.53, 518.81, 518.83, 518.84, 519.8, 798.9

Heart and cerebrovascular diseases

390, 391, 391.1, 391.2, 391.8, 391.9, 392, 392.9, 394, 394.1, 394.2, 402.11, 402.01, 402.91, 428, 428.1, 428.2, 428.21, 428.22, 428.23, 428.3, 428.31, 428.32, 428.33, 428.4, 428.41, 428.42, 428.43, 428.9, 395, 396, 410, 410.1, 410.2, 410.3, 410.4, 410.5, 410.6, 410.7, 410.8, 410.9, 411, 411, 411.1, 412, 414.1, 414.11, 414.12, 414.8, 414.9, 415, 415, 415.1, 415.11, 415.12, 415.19, 416, 416, 416.1, 416.2, 416.8, 416.9, 417, 417, 417.1, 417.8, 417.9, 420, 420.9, 420.91, 421, 421, 422, 422.9, 422.91, 423, 424, 424, 424.1, 424.2, 424.3, 425, 425, 425.1, 425.2, 425.3, 425.4, 425.5, 425.7, 425.8, 425.9, 427.5, 427.41, 427.4, 429, 429.2, 429.3, 429.4, 429.5, 429.6, 429.7, 429.9, 430, 431, 432, 432.9, 433, 433, 433.1, 433.2, 434, 434, 434, 434.01, 434.1, 434.1, 434.11

Liver disease

571, 571.1, 571.2, 571.3, 572.2, 573.3, 570, 572.8, 571.41, 571.49, 571.4, 571.5, 571.9, 571.6, 572, 572.1, 571.42, 571.8, 573, 573.8, 573.4, 572.3, 572.4, 573.5, 573.9

Renal disease

584.5, 583.6, 584.6, 583.7, 584.7, 584.8, 584.9, 585.1, 585.2, 585.3, 585.4, 585.5, 585.6, 585.9, 593.81, 593.2, 593.1, 593.89, 593, 590.3, 593.82, 593.9, 403.01, 403.11, 403.91

Neurodegenerative disease and stroke, global cerebral ischemia

335.29, 332, 333.4, 340, 335.2, 335.21, 335.22, 335.24, 333, 438.0-438.9, 331-331.2, 331.8, 332, 342, 344.1, 344.81, 348.1, 434.91, 997.01, 348.1

Dementia

290, 290.1, 290.2, 290.3, 290.8, 290.9, 331, 290.4, 290.41, 290, 290.1, 290.11, 290.13, 290.21, 290.8, 290.9, 294.2, 294.21, 797

HIV/AIDS

42

Footnotes

None of the authors have competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Teno JM, Freedman VA, Kasper JD, Gozalo P, Mor V. Is Care for the Dying Improving in the United States? Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2015;18:662–6. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, DC: 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teno JM, Gozalo PI, Bynum JPW, et al. Change in End-of-Life Care for Medicare Beneficiaries: Site of Death, Place of Care and Health Care Transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA. 2013;309:470–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.207624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabow M, Kvale E, Barbour L, et al. Moving Upstream: A Review of the Evidence of the Impact of Outpatient Palliative Care. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2013;16:1540–9. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahia CL, Blais CM. Primary Palliative Care for the General Internist: Integrating Goals of Care Discussions into the Outpatinet Setting. The Ochsner Journal. 2014;14:704–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lupu D. Estimate of Current Hospice and Palliative Medicine Physician Workforce Shortage. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2010;40:899–911. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus Specialist Palliative Care - Creating a More Sustainable Model. NEJM. 2013;368:1173–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Virdun C, Luckett T, Davidson PM, Phillips J. Dying in the hospital setting: A systematic review of quantitative studies identifying the elements of end-of-life care that patients and their families rank as being most important. Palliative Medicine. 2015;29:774–96. doi: 10.1177/0269216315583032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson J, Gott M, Ingleton C. Patient and family experiences of palliative care in hospital: what do we know? An integrative review Palliat Med. 2014;28:18–33. doi: 10.1177/0269216313487568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connor SR, Elwert F, Spence C, Christakis NA. Racial disparity in hospice use in the United States in 2002. Palliat Med. 2008;22:205–13. doi: 10.1177/0269216308089305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nayar P, Qiu F, Watanabe-Galloway S, et al. Disparities in end of life care for elderly lung cancer patients. J Community Health. 2014;39:1012–9. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9850-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Check DK, Samuel CA, Rosenstein DL, Dusetzina SB. Investigation of Racial Disparities in Early Supportive Medication Use and End-of-Life Care Among Medicare Beneficiaries With Stage IV Breast Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.8162. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LoPresti MA, Dement F, Gold HT. End-of-Life Care for People With Cancer From Ethnic Minority Groups: A Systematic Review. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care. 2016;33:291–305. doi: 10.1177/1049909114565658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson KS. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Palliative Care. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2013;16:1329–34. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.9468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Connor S, Elwert F, Spence C, Christakis N. Racial disparity in hospice use in the United States in 2002. Palliative Medicine. 2008;22:205–13. doi: 10.1177/0269216308089305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nayar P, Qiu F, Wantanabe-Galloway S, et al. Disparities in End of Life Care for Elderly Lung Cancer Patients. Journal of Community Health. 2014;39:1012–9. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9850-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma RK, Cameron KA, Chmiel JS, et al. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Inpatient Palliative Care Consultation for Patients With Advanced Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33:3802–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salomon S, Chuang E, Bhupali D, Labovitz D. Race/Ethnicity as a Predictor for Location of Death in Patients With Acute Neurovascular Events. Epub ahead of print. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2017 doi: 10.1177/1049909116687258. doi:1049909116687258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fischer SM, Kutner JS, Sauaia A, Kramer A. Lack of Ethinic Differences in End-of-Life Care in the Veterans Health Administration. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care. 2007;24:277–83. doi: 10.1177/1049909107302295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Mahony S, McHenry J, Blank AE, et al. Preliminary report of the integration of a palliative care team into an intensive care unit. Palliat Med. 2010;24:154–65. doi: 10.1177/0269216309346540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eti S, O'Mahony S, McHugh M, Guilbe R, Blank A, Selwyn P. Outcomes of the acute palliative care unit in an academic medical center. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31:380–4. doi: 10.1177/1049909113489164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Penrod JD, Deb P, Luhrs C, Dellenbaugh C, Zhu CW, Hochman T. Cost and utilization outcomes of patients receiving hospital-based palliative care consultation. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2006;9:855–60. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hua MS, Li G, Blinderman CD, Wunsch H. Estimates of the Need for Palliative Care Consultation across United States Intensive Care Units Using a Trigger-based Model. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2013;189:428–36. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201307-1229OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murtagh F, Bausewein C, Verne J, Groeneveld E, Kaloki Y, Higginson I. How many people need palliative care? A study developing and comparing methods for population-based estimates. Palliative Medicine. 2014;28:49–58. doi: 10.1177/0269216313489367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beynon T, Gomes B, Murtagh FEM, et al. How common are palliative care needs among older people who die in the emergency department? Emerg Med J. 2015;28:491–5. doi: 10.1136/emj.2009.090019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grbich C, Maddocks I, Parker D, et al. Identification of patients with noncancer diseases for palliative care services. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2005;3:5–14. doi: 10.1017/s1478951505050029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McNamara B, Rosenwax LK, Holman CDAJ. A Method for Defining and Estimating the Palliative Care Population. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2006;32:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norton SA, Hogan LA, Holloway RG, Temkin-Greener H, Buckley MJ, Quill TE. Proactive palliative care in the medical intensive care unit: Effects on length of stay for selected high-risk patients. Critical Care Medicine. 2007;35:1530–5. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266533.06543.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szekendi MK, Vaughn J, Lal A, Ouchi K, Williams MV. The Prevalence of Inpatients at 33 U.S. Hospitals Appropriate for and Receiving Referral to Palliative Care. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2016;19:360–72. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rainone F, Blank A, Selwyn PA. The Early Identification of Palliative Care Patients: Preliminary Processes and Estimates From Urban, Family Medicine Practices. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care. 2007;24:137–40. doi: 10.1177/1049909106296973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.ICU Without Walls. Einstein/Montefiore Department of Medicine, 2016. [Accessed 5/3/2016];2016 at https://www.einstein.yu.edu/departments/medicine/medicine.aspx?id=20178.

- 32.Rodriguez R, Marr L, Rajput A, Fahy BN. Utilization of palliative care consultation service by surgical services. Ann Palliat Med. 2015;4:194–9. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2224-5820.2015.09.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, Ersek M, Lipsitz SR, Keating NL. Quality of End-of-Life Care Provided to Patients With Different Serious Illnesses. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1095–102. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramey SJ, Chin SH. Disparity in Hospice Utilization by African American Patients With Cancer. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 2012;29:346–54. doi: 10.1177/1049909111423804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dy SM, Herr K, Bernacki RE, et al. Methodological Research Priorities in Palliative Care and Hospice Quality Measurement. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2016;51:155–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dumanovsky T, Rogers M, Spragens LH, Morrison RS, Meier DE. Impact of Staffing on Access to Palliative Care in U.S. Hospitals Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2015;18:998–9. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barnato AE, Anthony DL, Skinner J, Gallagher PM, Fisher ES. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Preferences for End-of-Life Treatment. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24:695–701. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0952-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]