Abstract

Background

Evidence-based HIV treatment adherence interventions have typically shown medium-sized effects on adherence. Prior evidence-based HIV treatment adherence interventions have not been culturally tailored specifically for Black/African Americans, the population most affected by HIV disparities in the U.S., who exhibit lower adherence than do members of other racial/ethnic groups.

Purpose

We conducted a randomized controlled trial of Rise, a 6-month culturally congruent adherence counseling intervention for HIV-positive Black men and women.

Methods

Rise was delivered by a trained peer counselor who used a problem-solving approach to address culturally congruent adherence barriers (e.g., medical mistrust, HIV stigma) and assisted with linkage to supportive services. A total of 215 participants were randomized to the intervention group (n = 107) or a wait-list control group (n = 108). Adherence was assessed daily via electronic monitoring.

Results

In a repeated measures multivariate logistic regression model of dichotomous adherence (using a clinically significant cut-off of 85% of doses taken), adjusted for socio-demographic and medical covariates, adherence in the intervention group improved over time relative to the control group, OR = 1.30 per month (95% CI = 1.12–1.51) p < 0.001, representing a large cumulative effect after 6 months (OR = 4.76, Cohen’s d = 0.86).

Conclusions

Rise showed a larger effect on adherence than prior HIV adherence intervention studies. For greater effectiveness, interventions to improve adherence among Black people living with HIV may need to be customized to address culturally relevant barriers to adherence. (ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT01350544).

Keywords: Adherence, Antiretroviral treatment, Black/African American, HIV, Intervention

Compared to individuals of other races/ethnicities, Black people living with HIV are less likely to adhere to antiretroviral treatment and to be virally suppressed (1–3). Research indicates that culturally relevant factors (e.g., stigma, medical mistrust) contribute to HIV-related disparities (4–8), in addition to structural factors (e.g., poverty) and psychosocial issues (e.g., mental health) (9,10). However, no randomized controlled trial has tested an antiretroviral treatment adherence intervention that was designed to be culturally congruent for Black patients (i.e., customized to fit their values, beliefs, traditions, and practices). Given that antiretroviral treatment adherence interventions typically involve large numbers of Black participants, lack of cultural congruence may be one possible explanation for the observed inconsistent results of prior intervention studies (11–16).

We conducted a randomized controlled trial of Rise, a culturally congruent adherence intervention for HIV-positive Black adults (17). Rise draws on elements from community-based treatment education programs that have been associated with improved adherence (18,19). Led by a trained peer counselor, Rise is unique in its placement in community settings, instead of medical clinics, where most evidence-based adherence intervention evaluation tests have been conducted (20). Moreover, non-research federal funding for adherence programs for people living with HIV has been shifting from community to medical settings (21). Given high levels of medical mistrust in Black communities, community-based adherence programs led by non-medical counselors may have greater effectiveness than those in clinics.

Rise is grounded in social-ecological theory positing that disparities arise from multiple levels of influence (22). At the individual level, Rise uses client-centered counseling to reduce adherence barriers by building treatment knowledge and adherence skills, self-efficacy, and motivation (key predictors of adherence, based on the information-motivation-behavioral skills model) (23), and acknowledging and addressing cultural issues associated with nonadherence (e.g., medical mistrust, discrimination, internalized stigma) (7,8,24). At the structural level, Rise counselors provide assistance with linkage to supportive services (e.g., substance use treatment, housing assistance), using client-centered counseling to assess unmet needs and problem solve around structural barriers to getting services; such assistance has been related to HIV medication use (25) and treatment retention (26).

Per recommendations for the design of culturally congruent HIV interventions (27,28), when designing Rise, we took into account four primary survival mechanisms historically used by Black Americans to cope with oppression: (1) adaptive duality or “role flexing” (changing speech and behavior to appear acceptable to the group one is interacting with, such as presenting different, more submissive, behaviors to authority figures than to one’s close social network); (2) collectivist identity (interconnectedness; putting group ahead of individual); (3) indirect communication patterns (not directly or not assertively conveying one’s needs); and (4) mistrust of outsiders. Through its placement in trusted and respected community agencies and use of non-medical, trained lay counselors knowledgeable about (and from) clients’ communities and cultures, Rise addresses adaptive duality and mistrust of outsiders. Counselors engender client trust because they are not viewed as part of the medical system or seen as medical authority figures, leading clients to be less likely to “role flex” and more likely to present adherence issues accurately and directly (19). Counselors acknowledge historical and current challenges, including racism, that lead to mistrust and mental health-, substance use-, and poverty-related issues, and provide assistance with getting services to address these needs. Counselors address HIV and sexual orientation stigma as reasons for internalized stigma, and how stigma and consequent non-disclosure are barriers to medication-taking, care retention, and support-seeking (29). Counselors guide participants through stress reduction strategies for coping with life stressors, including stigma, that contribute to nonadherence. Rise taps into cultural notions of collectivist identity by working with clients to identify individuals in their social networks who can help with care and treatment. By using motivational interviewing techniques, a non-confrontational counseling style that encourages open communication in an accepting context (30), counselors counteract indirect communication patterns with frank conversations about care and treatment, as well as structural barriers to adherence and retention in care, inviting clients to be honest about their adherence levels and to openly discuss barriers that might be stigmatized (e.g., homelessness, substance use). Rise counselors directly address mistrust and promote critical processing of misconceptions about treatment, and supply clients with accurate information to counteract and replace inaccurate beliefs.

Prior antiretroviral treatment adherence interventions using counseling have generally shown medium-sized effects (i.e., Cohen’s d of about .5) on adherence for people living with HIV (12–16). Thus, we hypothesized that Rise would be associated with improved adherence among intervention participants relative to control participants, especially due to the integration of culturally congruent elements.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted from April, 2013–September, 2015 in Los Angeles County, California, where 48,908 individuals were known to be living with HIV/AIDS as of 12/31/14, 20% of whom were Black (31). In 2013, Black people living with HIV in Los Angeles County had the lowest rates of linkage to care within three months of diagnosis (72%) and viral suppression (74%), whereas Whites had the highest rates of both (83% and 89%, respectively) (31).

All intervention sessions and assessments were conducted at AIDS Project Los Angeles (APLA), the largest community-based AIDS service organization in Los Angeles County. APLA’s Community Advisory Board, comprised of clients and staff from APLA and additional local organizations primarily serving Black people living with HIV, was convened 1–3 times per year throughout the study to provide input on design, recruitment, and interpretation of results.

Randomization

A total of 215 Black participants were randomized to one of two conditions: the Rise intervention (n = 107), or a control group of usual care as received from primary HIV care providers (n = 108). Blocked randomization (with permuted block size) was used to ensure balance. The interviewer was blind to treatment assignment until after the participant completed the baseline assessment.

Intervention Structure

Rise consisted of one-month of core intervention sessions (three 60-minute counseling sessions at weeks 1, 2, and 4, and a group HIV education session during the first month), followed by two booster sessions (weeks 12 and 20). If participants exhibited nonadherence (<90% of prescribed doses taken, based on electronically monitored adherence data) in the prior month, they were offered up to two additional biweekly booster sessions following each of the two booster sessions. Thus, participants received three core individual counseling sessions and one core group session in the first month, followed by 2–6 booster sessions over the next four months (i.e., between 5 and 9 individual sessions and 1 group session in total).

A detailed description of the intervention protocol is available in a prior publication (17). In Session 1, the counselor provided psychoeducation about adherence, viral suppression, and drug resistance, as well as accurate information to dispel any misconceptions. Discrimination and disparities as potential reasons for medical mistrust were explicitly acknowledged. A needs assessment with special attention to social support was conducted and referrals for any unmet basic (e.g., housing) and mental health needs were provided. An Individual Service Plan of short- and long-term goals was developed in Session 1 and reviewed in each session.

The remaining sessions focused on adherence barriers. The counselor reviewed adherence (using electronically monitored adherence output). Clients identified barriers that may contribute to missed doses (e.g., side effects, stigma) and reviewed the stages of problem solving: defining the problem, deciding on a goal, generating possible solutions, selecting a potential solution, planning the solution’s implementation, and evaluating the solution’s effectiveness (at the next session). Together with the client, the counselor identified contextual cues that influence adherence to derive strategies for managing and controlling cues, and helped clients to determine how to integrate medication into daily routines.

Usual Care Control

Participants assigned to the control condition received routine ongoing care and treatment from their healthcare provider, including behavioral and supportive services. Most patients had some access to adherence support through the Ryan White medical case management program, which includes assessment of service needs (including an adherence assessment and reasons for missed doses/appointments), and coordination of medical and social services. In routine care, inquiries about adherence issues are common but not systematic, nor are the methods used to address adherence problems. The use of a usual care control group provided a direct comparison to what is currently being used in practice, which is relevant for informing program development and policy change, and to justify Rise, which requires more resources and complexity than usual care.

Counselor Training and Supervision

One Black peer counselor with in-depth knowledge of HIV and Black communities in Los Angeles conducted all sessions. The counselor was given a two-day training that included clinical information about HIV, antiretroviral treatment, confidentiality protection, HIPAA regulations, crisis intervention, referral resources for supportive services, adherence barriers, mental health and substance abuse assessment, study and intervention objectives, systematic use of the intervention manual, and role playing to master intervention exercises. The counselor was trained to use a motivational interviewing style (30) to help clients develop problem-solving skills to identify and overcome adherence barriers. The counselor did not adhere strictly to motivational interviewing, but was trained to ask open-ended questions, use reflective listening, and motivate change by highlighting discrepancies between behaviors or thoughts and stated health goals, and respecting client autonomy.

All sessions were audio-recorded. The supervisor (a PhD-level clinical psychologist) listened to all sessions of the first two clients, and then all recorded sessions of every fifth participant thereafter, after which he provided feedback during biweekly supervision sessions on fidelity to the intervention protocol and motivational interviewing spirit, based on a standard checklist (32). The supervisor’s ratings on the checklist informed the focus of supervision meetings with the counselor. Nearly all ratings were consistently high across sessions.

Participant Eligibility and Recruitment

Participants were recruited using flyers and outreach to staff and clients of relevant community organizations in Los Angeles County, referrals from providers, and radio and print advertisements. Eligibility criteria included: (1) age ≥18 years; (2) self-identification as Black/African American (if mixed race, primarily identify as Black/African American); (3) on antiretroviral treatment, as verified by prescription bottles and/or medical records; and (4) self-reported adherence problems [reported missing ≥1 dose in the past month, less than 100% adherence in the past month (a different criterion than the study outcome because self-reported adherence may be overestimated), sometimes stopping antiretroviral treatment if they felt worse, and/or missing any doses last weekend]. Participants were not eligible if they were currently participating in another adherence intervention or not willing to have their adherence electronically monitored. (No participant was excluded due to either of these criteria.)

Participants provided written informed consent and signed a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) form for release of medical record information. The Human Subjects Protection Committee of the RAND Corporation approved the study. A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health. The Clinical Trial Registration Number is NCT01350544.

Assessment and Analysis

Participants completed audio computer-assisted self-interviews at baseline and 3- and 6- months post-baseline. Interviewers downloaded electronically monitored adherence data and updated contact information at 1.5, 3, 4.5, and 6-months post-baseline.

Participants were paid $30 at baseline and 3- and 6-month follow-up, and $10 at 1.5 and 4.5-months post-baseline for visiting the study site to download adherence data. Participants received a $20 bonus for completing all assessments and another $20 bonus for updating contact information at any point during the study. Intervention participants received a snack and $10 per session to cover transportation costs.

Audio computer-assisted self-interview

The instrument included measures of age, race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, annual household income, employment status, level of education, housing status, and incarceration history (whether they had spent any time in a correctional facility, jail, prison, or detention center when they were 18 years old or older). Participants reported the month and year when they were diagnosed with HIV (from which the length of time diagnosed was calculated), and whether they had received HIV care in the last 6 months. Participants also reported the percentage of prescribed doses taken in the last month, an adherence item that has been validated against viral load (33). (Note that the present analysis used data from the baseline audio computer-assisted self-interview only; data from the follow-up audio computer-assisted self-interviews were not included in this analysis.)

Electronically monitored adherence

Adherence was electronically monitored daily for 6 months using the Medication Event Monitoring System (AARDEX, Inc.), which uses bottle caps that record times and dates when the medication bottle is opened. At baseline, the interviewer assisted participants in moving a one-month supply of one antiretroviral medication to the research-supplied bottle with an electronic monitoring cap. If more than one antiretroviral medication was prescribed, the medication with the most complex dosing schedule was used; if all medications had the same dosing schedule, the base of the drug regimen (non-nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor, protease inhibitor, or integrase strand transfer inhibitor) was monitored (34). At each time-point, participants were asked to report instances when the cap was not used as intended in the past two weeks (e.g., bottle opened without removing a dose); responses were used to adjust estimates of the percentage of doses taken (35). Electronic monitoring software was used to calculate the percentage of total scheduled doses taken at each follow-up time-period (“continuous adherence”). We dichotomized this continuous measure into greater than or equal to 85% of doses taken (“dichotomous adherence”) vs. less than 85% of doses taken, consistent with research suggesting clinically significant effects at this level (36–38).

Dichotomous and continuous measures of adherence provide different, complementary information about adherence and thus the utility of the intervention. The dichotomous measure represents the extent to which the sample achieves an optimal level of adherence that is needed to sustain good treatment outcomes (i.e., suppressed HIV viral load) and is the standard for evaluating intervention efficacy. The continuous measure provides a more complete sense of the adherence performance of the individual and sample, allowing for an evaluation of how the intervention moves adherence along the full range. In addition, research has shown that a change in mean adherence by 10% translates to a significant effect on HIV viral load (39), which highlights the value of additionally evaluating the intervention in terms of continuous adherence.

HIV outcomes

At enrollment, we asked participants to self-report HIV viral load and CD4 count, as well as to provide permission to collect medical records data on these indicators. We categorized viral load as undetectable (<50 copies of virus per milliliter of blood plasma) or detectable, whether self-reported or abstracted from medical records. Medical record viral load values, available for 166 participants, were prioritized for analyses. For the 49 participants for whom we could not obtain medical records data, we used baseline self-report. (Note that medical record availability did not differ by intervention condition.) We attempted to collect viral load and CD4 count from medical records at follow-up, but clinic assessments of these variables did not match the timing of the study assessments (e.g., some assessments fell during or well before or after the intervention period, rather than immediately before and after). Thus, we could not test the effects of Rise on viral suppression.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables. To assess Rise’s effects on adherence, we used generalized linear mixed models, specifically, repeated measures logistic regressions predicting dichotomous adherence at baseline and 1.5-, 3-, 4.5-, and 6-months post-baseline, with an intervention indicator, time (in months; we assumed a linear trend over time for adherence), an interaction term between intervention and time, an indicator for baseline report of adherence, sociodemographic and medical covariates, and baseline viral load. Parallel linear regressions were used to predict continuous adherence. Post-estimation contrasts were used to estimate changes in adherence within each treatment arm. Post-hoc ordinary logistic regressions were used to predict adherence separately at each follow-up time-point with intervention, baseline self-reported adherence, socio-demographic and medical covariates, and baseline viral load. Covariates included baseline sociodemographic and medical variables significantly or marginally associated with either intervention condition (age, low income, viral load) or adherence over time (age, incarceration), and any additional individual characteristics related to adherence in prior research (gender, education) (7,40). After conducting the main study analyses, we conducted sensitivity analyses using different adherence cut-points for the dichotomous adherence variable (80%, 90%). The primary analysis approach was intention-to-treat, in which all participants with baseline self-reported adherence and any electronically monitored adherence data were included, regardless of their level of participation in the intervention (i.e., number of sessions attended). All analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC), and the MI procedure was used for imputation of missing covariate data (missing at a level of 0–1.4%). Sample size was determined with a power analysis assuming .80 power and an alpha level of .05 that would allow for detection of a small-to-medium effect size in adherence between intervention arms.

Results

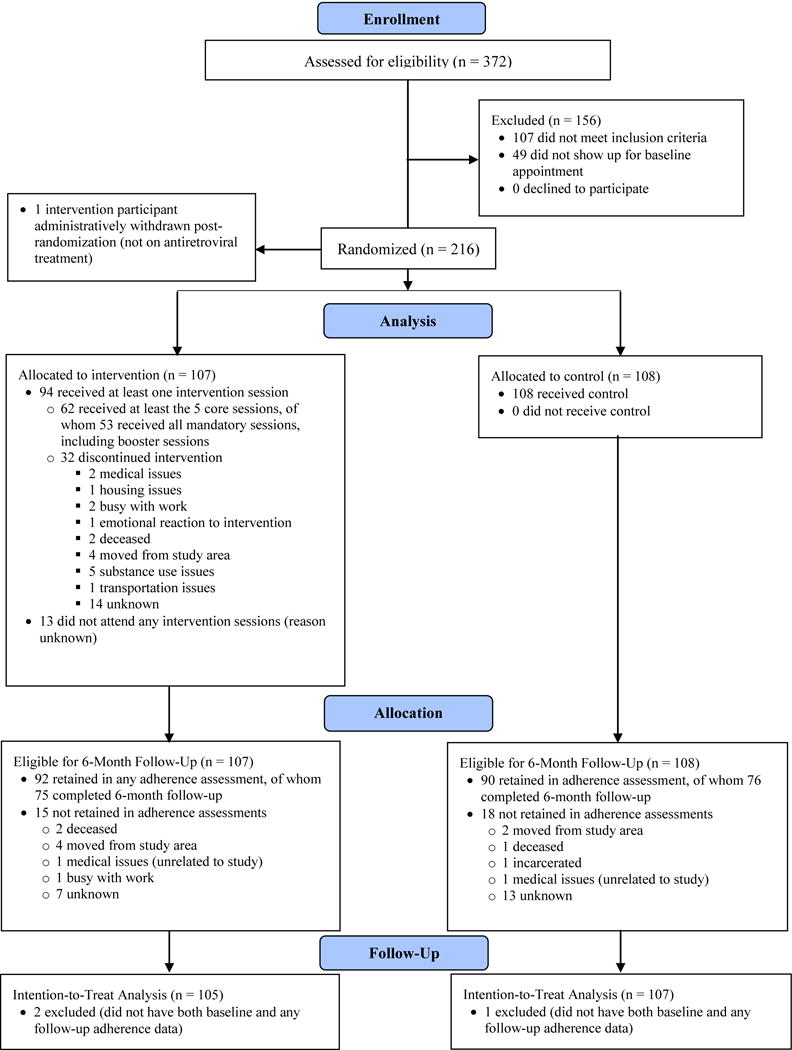

Participant Flow (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of study participants in the intervention and control groups

A total of 372 individuals were screened for eligibility, of whom 216 agreed to participate, 156 were excluded (107 did not meet inclusion criteria, 49 were eligible but failed to show up for the baseline appointment), and 1 case was removed post-randomization because the participant was not on antiretroviral treatment. A total of 107 participants were randomized to the intervention condition, and 108 to the control condition (after excluding the single administrative removal). Of the 215 participants, 182 (92 intervention, 90 control) provided electronically monitored adherence data (the primary intervention outcome) at any follow-up time-point after baseline, and 151 (75 intervention, 76 control) provided electronically monitored adherence data at 6-months post-baseline (the last follow-up assessment). For the purposes of the present analysis, participants were only excluded if they were missing adherence data at both baseline and follow-up; they were included if they had baseline self-reported adherence or electronically monitored adherence data at any time-point. Of the 215 participants, only 3 participants (2 intervention, 1 control) were excluded due to missing adherence data at both baseline and follow-up, resulting in a final analysis sample of 212 (with 105 in the intervention arm and 107 in the control arm).

Of the 107 assigned to the intervention group, 94 (88%) completed core session 1, 89 (83%) completed core sessions 1 and 2, and 84 (79%) completed core sessions 1–3. In addition, 78 (73%) of all participants completed the first booster session, and 64 (60%) completed the first and second booster sessions. Thirteen participants did not show up to any intervention sessions. Only 38 (36%) attended the group session.

Descriptive Characteristics

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics overall and by condition. Intervention and control participants did not significantly differ on most baseline characteristics. However, Rise participants were older on average.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Baseline Sample, Overall and by Study Condition

| Baseline Characteristic | Overall (N=215) M(SD) or % |

Intervention (N=107) M(SD) or % |

Control (N=108) M(SD) or % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 48.5 (SD=10.2) | 50.1 (10.0) | 47.0 (10.2) * |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 73.0 | 72.9 | 73.2 |

| Female | 23.7 | 25.2 | 22.2 |

| Transgender | 3.3 | 1.9 | 4.6 |

| Latino Ethnicity | 6.5 | 6.1 | 6.9 |

| Sexual Orientation | |||

| Straight | 36.3 | 39.3 | 33.3 |

| Gay man | 42.8 | 39.3 | 46.3 |

| Lesbian | 1.9 | 2.8 | 0.9 |

| Bisexual Man | 13.5 | 13.1 | 13.9 |

| Bisexual Woman | 1.4 | 1.9 | 0.9 |

| Not Sure | 1.4 | 1.9 | 0.9 |

| Other | 2.8 | 1.9 | 3.7 |

| Education | |||

| 7th to 11th Grade | 18.6 | 21.5 | 15.7 |

| High School diploma or GED | 32.6 | 30.8 | 34.3 |

| Some college | 37.7 | 37.4 | 38.0 |

| College degree | 6.1 | 6.5 | 5.6 |

| Some graduate school | 3.3 | 3.7 | 2.8 |

| Graduate degree | 1.9 | 0.0 | 3.7 |

| Income | + | ||

| None | 9.9 | 9.4 | 10.3 |

| >$0–<$10K | 55.9 | 50.0 | 61.7 |

| $10K–$20K | 24.9 | 33.0 | 16.8 |

| >$20K–$30K | 8.5 | 7.6 | 9.4 |

| >$30K–$40K | 0.9 | 0.0 | 1.9 |

| Housing Status | |||

| Rent/Own | 62.3 | 64.5 | 60.2 |

| Treatment facility | 5.1 | 1.9 | 8.3 |

| Subsidized/Sect. 8 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 7.4 |

| Friend/relative | 8.8 | 7.5 | 10.2 |

| Temporary or transitional | 10.2 | 12.2 | 8.3 |

| Homeless | 5.1 | 5.6 | 4.6 |

| Other | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Employment Status | |||

| Full time | 2.3 | 0.9 | 3.7 |

| Part time | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.7 |

| Unemployed | 62.3 | 66.4 | 58.3 |

| Retired | 15.4 | 13.1 | 17.6 |

| Other | 16.3 | 15.9 | 16.7 |

| Ever Incarcerated | 54.7 | 55.1 | 54.2 |

| Length of Time Diagnosed HIV+ | 15.4 years (SD=8.4) | 15.5 (7.9) | 15.3 (8.8) |

| Viral Load Undetectable (baseline) | 55.9 | 62.3 | 49.5+ |

| Received HIV care in last 6 months | 95.4 | 95.3 | 95.4 |

p < .10 and

p<.05 comparing intervention vs. control groups.

Note: Statistical significance was determined with t tests for continuous characteristics, Mantel-Haenszel Chi-Square for ordinal characteristics, Fisher’s Exact for binary characteristics, and Chi-square tests for all other characteristics. For age, t (213) = −2.23, p = 0.03.

Effects of Rise on Adherence

As shown in Table 2, in the intervention and control groups, only about half of participants showed optimal adherence (≥85% of doses taken), and on average participants took about 80% of their doses at baseline. Table 3 shows the results from the repeated measures logistic regression model with a dichotomous adherence outcome. As indicated by the significant interaction term, adherence in the intervention group increased over time relative to the control group, OR (CI) = 1.30 (1.12–1.51), p < .001. This odds ratio represented the relative odds of adherence per month after the intervention. The effect size (Cohen’s d) of 0.86 after 6 months of follow-up was calculated by exponentiating the per-month (unrounded) odds ratio by 6 (OR = 1.2972976 = 4.76), converting the six-month odds ratio into a log-odds [ln (4.76) = 1.56], and then dividing this log-odds by 1.81, resulting in a large effect size of 0.862 (1.56/1.81) (41).

Table 2.

Intervention-Control Group Differences at Each Follow-Up Time-Point for Dichotomous Adherence (≥85% of Doses Taken) and Continuous Adherence (Percentage of Doses Taken)

| Dichotomous Adherence | Continuous Adherence | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control % | Intervention % | Intervention-Control Difference OR (95% CI), p | Cohen’s d | Control [M(SD)] | Intervention [M(SD)] | Intervention-Control Difference b (SE), p | Cohen’s d | |

| Baseline | 52 | 54 | ----- | ----- | 77.96 (23.15) |

80.13 (21.74) |

----- | ----- |

| 1.5 Month Follow-Up (n = 164) |

48 | 52 | 1.07 (0.54–2.09), p=.85 |

.03 | 64.47 (33.87) |

75.33 (26.46) |

9.03 (4.66), p=.055 |

.29 |

| 3 Month Follow-Up (n = 161) |

38 | 56 | 1.97 (0.99–3.92), p=.055 |

.37 | 63.01 (33.03) |

75.55 (26.17) |

9.12 (4.24), p=.03 |

.30 |

| 4.5 Month Follow-Up (n = 148) |

36 | 59 | 2.34 (1.14–4.80), p=.02 |

.47 | 61.46 (33.25) |

78.16 (26.68) |

11.73 (4.87), p=.02 |

.38 |

| 6 Month Follow-Up (n = 148) |

29 | 56 | 3.47 (1.60–7.53), p=.002 |

.69 | 56.24 (34.40) |

77.71 (24.09) |

16.35 (4.64), p<.001 |

.52 |

Notes: Baseline values are based on self-reports, and follow-up values are based on electronic monitoring. All odds ratios and effect sizes are adjusted for baseline self-reported adherence, socio-demographic covariates [age, gender, low income, low education, history of incarceration (since age 18), and viral suppression]. (Adherence rates are unadjusted.)

Table 3.

Repeated Measures Regression Models Comparing Intervention Group to Control Group, and Within Intervention and Control Groups, Over Time for Dichotomous and Continuous Adherence (n = 212)

| Dichotomous Adherence | Intervention vs. Control | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Intervention1 | 0.87 (0.47–1.61) | .66 |

| Time (Months After Baseline)2 | 0.79 (0.69–0.91) | <.001 |

| Baseline Time-Point | 1.01 (0.60–1.73) | .96 |

| Intervention × Time (Intervention effect)3 | 1.30 (1.12–1.51) | <.001 |

| Socio-Demographic Covariates | ||

| Age (continuous) | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) | .01 |

| Female Gender | 0.77 (0.45–1.33) | .35 |

| Low Income | 1.41 (0.84–2.37) | .20 |

| Low Education | 0.87 (0.45–1.68) | .68 |

| Ever Incarcerated | 0.82 (0.51–1.32) | .41 |

| Viral Load (undetectable) | 2.00 (1.21–3.29) | .007 |

| Continuous Adherence | B (SE) | p |

| Intervention1 | 0.86 (3.36) | .80 |

| Time (Months After Baseline)2 | −2.46 (0.62) | <.001 |

| Baseline Time-Point | 7.98 (2.56) | .002 |

| Intervention × Time3 | 3.16 (0.70) | <.001 |

| Socio-Demographic Covariates | ||

| Age (continuous) | 0.49 (0.15) | <.001 |

| Female Gender | −0.21 (3.14) | .95 |

| Low Income | 2.70 (3.02) | .37 |

| Low Education | 1.65 (3.75) | .66 |

| Ever Incarcerated | −4.10 (2.79) | .14 |

| Viral Load (undetectable) | 13.94 (2.91) | <.001 |

The intervention main effect represents the difference in adherence between the intervention and control group without taking into account the effect of time.

The “time” main effect represents change in adherence per month for the control group, in this case a significant decrease over time.

This interaction represents the change in the intervention group relative to the control group, per month. For dichotomous adherence, one month after baseline (time = 1), a participant in the intervention group was 1.30 times more likely to be adherent than a participant in the control group. The odds ratio at 6 months is calculated from the unrounded one-month odds ratio as 1.2976 = 4.76; the log-odds is ln(4.76) = 1.56, a Cohen’s d effect size of 0.86 (1.56/1.81). For continuous adherence, after 6 months, the intervention effect is 3.16 × 6 = 18.96, i.e., a positive change in adherence of 19% relative to the control group.

Post-hoc logistic regressions predicting adherence separately at each follow-up time-point, adjusted for covariates, indicated superior adherence among Rise (vs. control) participants at months 4.5 and 6 (Table 2). Post-estimation within-group contrasts from the repeated measures model indicated that adherence in the control group significantly decreased (OR = 0.79, 95% CI 0.69–0.91, p < 0.001), whereas adherence in the intervention group remained stable per month (OR = 1.03, 95% CI 0.90–1.17, p = 0.68).

Results were similar for continuous adherence (Table 3). In the overall repeated measures linear regression model, the intervention by time interaction was significant, revealing a 3.16% increase per month in the intervention group’s average adherence relative to the control group. At 6 months, the model estimated a relative difference of 19.0% (3.16 × 6) at 6 months. Post-hoc logistic regressions indicated greater adherence among intervention compared to control participants at months 3, 4.5, and 6 (Table 2). Adherence in the control group significantly decreased over time (b[se] = −2.46 [0.62], p < 0.001), whereas adherence in the intervention group remained stable (b[se] = 0.70 [0.62], p = 0.26).

The interaction effects for dichotomous adherence in the overall repeated measures sensitivity analyses were significant, consistent with the results for the 85% adherence cut-off [OR = 1.28 per month, p = .001, d = 0.83 at 6 months for the 80% adherence cut-off, and OR = 1.19 per month, p = 0.02, d = 0.56 at 6 months for the 90% adherence cut-off].

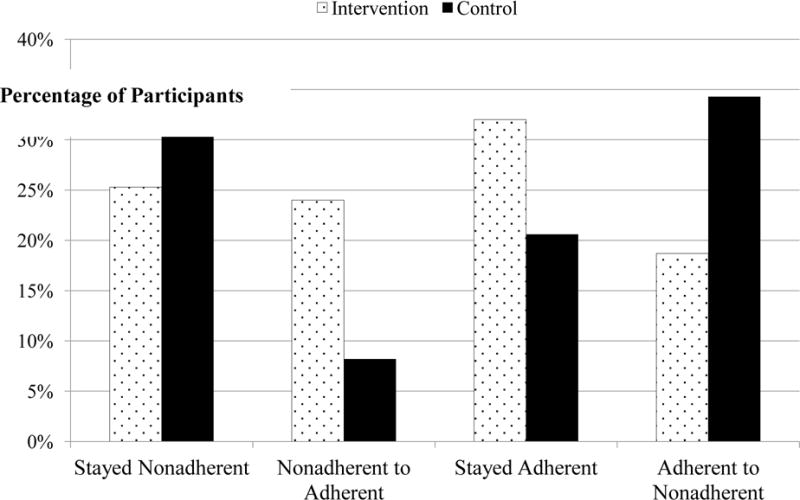

We graphed adherence patterns in the intervention and control groups, using the adherence benchmark of at least 85% of doses taken (a more conservative criterion than used for study entry) (Figure 2). A total of 37.0% of control participants, versus 25.3% of intervention participants, were non-adherent at baseline and remained non-adherent at follow-up; only 8.2% of control participants versus 24.0% of intervention participants started the study as non-adherent and became adherent over time. Only 20.6% of control participants stayed adherent from baseline to follow-up, but 32.0% of intervention participants maintained adherence over time. Only 18.7% of intervention participants, versus 34.3% of control participants, started the study as adherent but dropped to non-adherent by the end of the study.

Figure 2.

Adherence and non-adherence patterns from baseline to 6-month follow-up

Discussion

In this randomized controlled trial of a community-based, culturally congruent adherence intervention for Black people living with HIV, we found large effects on adherence over time. No randomized controlled trials to our knowledge have tested an adherence intervention specifically tailored for HIV-positive Black persons, who generally show low adherence and viral suppression rates (1,42). Moreover, previous meta-analyses have indicated at best medium effect sizes for HIV treatment adherence interventions, with a substantial number showing non-significant results (12–16). Our findings suggest that culturally tailoring interventions for Black HIV-positive persons may increase their effectiveness and that lack of cultural congruence may be one possible explanation for prior mixed adherence intervention results.

The intervention effect was largely due to significant declines in adherence in the control group and a stable pattern of optimal adherence in the intervention group. Thus, at a minimum, Rise helped to stem a natural decrease in adherence, which could have substantial impact on maintaining viral suppression. These findings are consistent with prior research indicating that antiretroviral treatment adherence declines with time (42), and prior intervention research (e.g., Smart Couples, an evidence-based antiretroviral treatment adherence intervention in the CDC compendium) showing stable adherence in the intervention group over time (43). Moreover, adherence may have continued to decline over time in the control group because the control group did not receive tailored, ongoing adherence counseling (to problem solve how to overcome adherence barriers). Sustained adherence support, tailored to clients’ needs as in Rise, may be important for maintaining optimal adherence over time.

The combination of self-reported baseline adherence and reactance to electronic monitoring likely inflated initial adherence levels, potentially masking any adherence improvements in the intervention condition. Adherence at baseline was assessed via self-report, which has been shown to be overestimated (44,45). Thereafter, adherence was measured by electronic monitoring, which may have been artificially inflated due to reactance in the first month of monitoring (i.e., a Hawthorne effect: when participants who are aware that their adherence is being monitored improve their adherence in response). Research suggests that reactance to electronic monitoring is highest in the first month (42), which would have applied to the present study’s first adherence follow-up assessment.

Although Rise showed a large effect on adherence, the mechanisms underlying this effect were not elucidated by the results. The intervention was hypothesized to reduce internalized stigma and medical mistrust, but in post-hoc mediation analyses (results not shown), we did not find significant intervention effects on these constructs. One potential explanation is that our measures of stigma and mistrust may have been too general to adequately capture the ways in which the intervention led to greater adherence. For example, participants’ trust in and rapport with the intervention counselor specifically may have been driving the results, rather than their general trust in healthcare and support from their network as a whole.

Several limitations should be noted. Results are limited in generalizability to the specific setting and population studied and may be less applicable to HIV-positive Black/African Americans in other regions. We were unable to test the effects of Rise on viral suppression. Given that adherence measured through electronic monitoring has been shown to be moderately associated with viral load in prior research (45), Rise’s large effects on adherence suggest that the intervention likely affected viral load as well. In addition, we did not specifically test whether cultural tailoring led to the large intervention effect. However, based on community advisory board input, it would have been challenging to conduct the present study, and to recruit and retain participants, if the intervention had not been culturally congruent. We also found lower retention in the booster sessions than in the core intervention sessions, and poor attendance for the group session, suggesting that participation in the core individual counseling sessions may have been driving the intervention effect. Other limitations include the lack of longer-term follow-up and that baseline adherence was assessed by self-report (although electronically monitored adherence was used at follow-up).

Another limitation is that we did not test which intervention component was driving the effect. We believe that both components (i.e., culturally congruent client-centered counseling and assistance with structural barriers) are essential and synergistic in overcoming adherence barriers. In particular, Rise’s core counseling sessions may help to overcome psychosocial and culturally relevant barriers such as mistrust, and in turn motivate clients to adhere; however, entrenched structural barriers such as transportation issues need to be addressed in tandem with psychosocial barriers, so that clients have the means to realize the goal of optimal adherence.

Future research should test Rise in a randomized controlled trial that includes long-term follow-up and examines viral suppression, and that omits the group session, which was not well-attended. Implementation science studies are also needed to help translate effective antiretroviral treatment adherence interventions for widespread use. Even if HIV treatment adherence interventions are shown to be effective in randomized controlled trials, issues of implementation—including costs, logistics, and scalability—are important to address for interventions to be disseminated and sustained. Furthermore, for greater effectiveness, interventions to improve adherence among Black people living with HIV may need to be customized to address culturally relevant barriers to adherence, including high levels of medical mistrust and HIV stigma (5–8), and placed in communities in addition to medical settings.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health (grant number R01 MD006058). This work was also supported in part by the Center for HIV Identification, Prevention, and Treatment (CHIPTS) NIMH grant MH58107. We are grateful to Sean Lawrence, Brian Risley, and Kieta Mutepfa for their contributions to and guidance on the data collection and intervention procedures, and to the members of the AIDS Project Los Angeles Community Advisory Board for their contributions throughout every stage of the study.

Footnotes

Authors Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards

All authors (Bogart, Mutchler, McDavitt, Klein, Cunningham, Goggin, Ghosh-Dastidar, Rachal, Nogg, Wagner) declare that they have no conflict of interest. All procedures, including the informed consent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Contributor Information

Laura M. Bogart, RAND Corporation.

Matt G. Mutchler, California State University, Dominguez Hills, CA, and AIDS Project Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA.

Bryce McDavitt, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, and AIDS Project Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA.

David J. Klein, RAND Corporation.

William E. Cunningham, University of California, Los Angeles

Kathy J. Goggin, Children's Mercy Kansas City, Kansas, City, MO, and University of Missouri - Kansas City Schools of Medicine and Pharmacy, Kansas City, MO.

Bonnie Ghosh-Dastidar, RAND Corporation.

Nikki Rachal, AIDS Project Los Angeles.

Kelsey A. Nogg, AIDS Project Los Angeles.

Glenn J. Wagner, RAND Corporation.

References

- 1.HIV in the United States: The stages of care. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simoni JM, Huh D, Wilson IB, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in ART adherence in the United States: Findings from the MACH14 study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(5):466–472. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825db0bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV care outcomes among blacks with diagnosed HIV - United States, 2014. MMWR. 2017;66(4):97–103. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6604a2. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/166/wr/mm6604a6602.htm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Earnshaw V, Bogart LM, Dovidio J, Williams D. Stigma and racial/ethnic HIV disparities: Moving towards resilience. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):225–236. doi: 10.1037/a0032705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, Green HD, Mutchler MG, Klein DJ, McDavitt B. Social network characteristics moderate the association between stigmatizing attributions about HIV and non-adherence among black americans living with HIV: A longitudinal assessment. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49(6):865–872. doi: 10.1007/s12160-015-9724-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, Green HD, et al. Medical mistrust among social network members may contribute to antiretroviral treatment nonadherence in African Americans living with HIV. Soc Sci Med. 2016;164:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, Galvan FH, Klein DJ. Longitudinal relationships between antiretroviral treatment adherence and discrimination due to HIV-serostatus, race, and sexual orientation among African American men with HIV. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40(2):184–190. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9200-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bogart LM, Wagner G, Galvan FH, Banks D. Conspiracy beliefs about HIV are related to antiretroviral treatment nonadherence among African American men with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(5):648–655. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c57dbc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rumptz MH, Tobias C, Rajabiun S, et al. Factors associated with engaging socially marginalized HIV-positive persons in primary care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(suppl 1):S30–S39. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham WE, Andersen RM, Katz MH, et al. The impact of competing subsistence needs and barriers on access to medical care for persons with Human Immunodeficiency Virus receiving care in the United States. Med Care. 1999;37(12):1270–1281. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199912000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaiyachati KH, Ogbuoji O, Price M, Suthar AB, Negussie EK, Barnighausen T. Interventions to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A rapid systematic review. AIDS. 2014;28(Suppl 2):S187–204. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathes T, Pieper D, Antoine SL, Eikermann M. Adherence-enhancing interventions for highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients – A systematic review. HIV Medicine. 2013;14(10):583–595. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simoni JM, Amico KR, Smith L, Nelson K. Antiretroviral adherence interventions: Translating research findings to the real world clinic. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2010;7(1):44–51. doi: 10.1007/s11904-009-0037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amico KR, Harman JJ, Johnson BT. Efficacy of antiretroviral therapy adherence interventions: A research synthesis of trials, 1996 to 2004. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41(3):285–297. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000197870.99196.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charania MR, Marshall KJ, Lyles CM, et al. Identification of evidence-based interventions for promoting hiv medication adherence: Findings from a systematic review of U.S.-based studies, 1996–2011. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(4):646–660. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0594-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Complete listing of medication adherence evidence-based behavioral interventions. 2015 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/interventionresearch/compendium/ma/complete.html.

- 17.Wagner GJ, Bogart LM, Mutchler MG, McDavitt B, Mutepfa KD, Risley B. Increasing antiretroviral adherence for HIV-positive African Americans (project Rise): A treatment education intervention protocol. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5(1):e45. doi: 10.2196/resprot.5245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, Mutchler MG, et al. Community HIV treatment advocacy programs may support treatment adherence. AIDS Educ Prev. 2012;24(1):1–14. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2012.24.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mutchler MG, Wagner G, Cowgill BO, McKay T, Risley B, Bogart LM. Improving HIV/AIDS care through treatment advocacy: Going beyond client education to empowerment by facilitating client–provider relationships. AIDS Care. 2011;23(1):79–90. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.496847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simoni JM, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Marks G, Crepatz N. Efficacy of interventions in improving highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence and HIV-1 RNA viral load: A meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(suppl 1):S23–S35. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248342.05438.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Redefining Case Management. Rockville, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufman MR, Cornish F, Zimmerman RS, Johnson BT. Health behavior change models for HIV prevention and AIDS care: Practical recommendations for a multi-level approach. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66(Suppl 3):S250–S258. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Starace F, Massa A, Amico KR, Fisher JD. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy: An empirical test of the information-motivation-behavioral skills model. Health Psychol. 2006;25(2):153–162. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith R, Rossetto K, Peterson BL. A meta-analysis of disclosure of one’s HIV-positive status, stigma and social support. AIDS Care. 2008;20(10):1266–1275. doi: 10.1080/09540120801926977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz MH, Cunningham WE, Fleishman JA, et al. Effects of case management on unmet needs and utilization of medical care and medications among HIV-infected persons. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(8):557–565. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-8_part_1-200110160-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gardner LI, Metsch LR, Anderson-Mahoney P, et al. Efficacy of a brief case management intervention to link recently diagnosed HIV-infected persons to care. AIDS. 2005;19(4):423–431. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000161772.51900.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams JK, Wyatt GE, Wingood G. The four C’s of HIV prevention with African Americans: Crisis, condoms, culture, and community. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7(4):185–193. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0058-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wyatt GE. Enhancing cultural and contextual intervention strategies to reduce HIV/AIDS among African Americans. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(11):1941–1945. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sayles JN, Wong MD, Cunningham WE. The inability to take medications openly at home: Does it help explain gender disparities in HAART use? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006;15(2):173–181. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Division of HIV and STD Programs Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. 2014 Annual HIV/STD Surveillance Report. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moyers T, Martin T, Manuel J, Miller WR. The motivational interviewing treatment integrity (MITI) code, version 2.0. New Mexico: University of New Mexico, Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse and Addictions; Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simoni JM, Kurth AE, Pearso CR, Pantalone DW, Merrill JO, Frick PA. Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: A review with recommendations for research and clinical management. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):227–245. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9078-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnsten JH, Demas PA, Grant RW, et al. Impact of active drug use on antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(5):377–381. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10644.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bangsberg DR, Hecht FM, Charlebois ED, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitors, HIV-1 viral load, and development of drug resistance in an indigent population. AIDS. 2000;14(4):357–366. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003100-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bangsberg DR. Less than 95% adherence to nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy can lead to viral suppression. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(7):939–941. doi: 10.1086/507526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kobin AB, Sheth NU. Levels of adherence required for virologic suppression among newer antiretroviral medications. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(3):372–379. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shuter J, Sarlo JA, Kanmaz TJ, Rode RA, Zingman BS. HIV-infected patients receiving Lopinavir/Ritonavir-based antiretroviral therapy achieve high rates of virologic suppression despite adherence rates less than 95% J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45(1):4–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318050d8c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu H, Miller LG, Hays RD, et al. Repeated measures longitudinal analyses of HIV virologic response as a function of percent adherence, dose timing, genotypic sensitivity, and other factors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41(3):315–322. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000197071.77482.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meyer JP, Zelenev A, Wickersham JA, Williams CT, Teixeira PA, Altice FL. Gender disparities in HIV treatment outcomes following release from jail: Results from a multicenter study. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):434–441. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chinn S. A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2000;19(22):3127–3131. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001130)19:22<3127::aid-sim784>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson IB, Bangsberg DR, Shen J, et al. Heterogeneity among studies in rates of decline of antiretroviral therapy adherence over time: Results from the multisite adherence collaboration on HIV 14 study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64(5):448–454. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Remien RH, Stirratt MJ, Dolezal C, et al. Couple-focused support to improve HIV medication adherence: A randomized controlled trial. AIDS. 2005;19(8):807–814. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000168975.44219.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wagner GJ, Rabkin JG. Measuring medication adherence: Are missed doses reported more accurately than perfect adherence? AIDS Care. 2000;12(4):405–408. doi: 10.1080/09540120050123800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arnsten JH, Demas PA, Farzadegan H, et al. Antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users: Comparison of self-report and electronic monitoring. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(8):1417–1423. doi: 10.1086/323201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]