Abstract

Context

Despite the recent promotion of communication guides to improve decision making with patients nearing the end of their lives, these conversations remain challenging. Deeper and more comprehensive understanding of communication barriers that undermine discussions and decisions with patients at risk of dying from heart failure (HF) is vital for informing communication in health care.

Objectives

To explore experiences and perspectives of patients with advanced HF, their caregivers, and providers, regarding conversations for patients at risk of dying from HF.

Methods

Following Research Ethics Board approval, index patients with advanced HF (New York Heart Association III or IV) and consenting patient-identified care team members were interviewed. A team sampling unit was formed when the patient plus at least two additional team members participated in interviews. Team members included health professionals (e.g., cardiologist, family physician, HF nurse practitioner, social worker, and specialists, such as respirologist, nephrologist, palliative care physician), family caregivers (e.g., daughter, spouse, roommate, close friend), and community members (e.g., minister, neighbor, regular taxi driver). Our data set included 209 individual interviews clustered into 50 team sampling units at five sites from three Canadian provinces. Key informants, identified as practicing experts in the field, reviewed our initial findings with attention to relevance to practice as a form of triangulation. Iterative data collection and analysis followed constructivist grounded theory procedures with sensitizing concepts drawn from complexity theory. To ensure confidentiality, all participants were given a pseudonym.

Results

Participants’ reports of their perceptions and experiences of conversations related to death and dying suggested two main dimensions of such conversations: instrumental and existential. Instrumental dimensions included how these conversations were planned and operationalized as well as the triggers and barriers to these discussions. Existential dimensions of these conversations included evasive maneuvers, powerful emotions, and the phenomenon of death without dying. Existential dimensions appeared to have a basis in issues of mortality and could strongly influence conversations related to death and dying.

Conclusion

Conversations for patients at risk of dying from HF have both instrumental and existential dimensions, in which routines and relationships are inseparable. Our current focus on the instrumental aspects of these conversations is necessary but insufficient. The existential dimensions of conversations related to death are profound and may explain why these conversations have struggled to achieve their desired effect. To improve this communication, we need to also attend to existential dimensions, particularly in terms of their impact on the occurrence of these conversations, the nature of relationships and responses within these conversations, and the fluidity of meaning within these conversations.

Keywords: Death and dying conversations, existential, emotion, mortality salience, end-of-life conversations for heart failure

Introduction

Providers struggle to navigate communication related to dying and death for patients with chronic illness such as heart failure (HF).1 Recent discussions articulate communication barriers that must be overcome to systematize and improve decision making at the end of life (EOL).1,2 But HF patients, caregivers, and health care providers (HCPs) remain largely reluctant to communicate about disease progression, prognosis, expectations for future care, death and dying, and palliative care (PC).3–5 With a growing population of patients facing life-altering health care choices in the context of chronic fatal illnesses like HF, we need to better understand the continuing elusiveness of meaningful and productive discussions for care at the EOL.6

In the past decade, guides to systematically conduct decision-making conversations have emerged in the literature as breaking bad news7 or goals-of-care (GOC) conversations.1 These guides encourage providers to share information regarding diagnosis, illness trajectory and prognosis, and to explore important goals, fears, acceptable functional outcomes, and motivation to seek health care.1,8 This systematic approach to talking about death is expected to improve decision making among patients with chronic life-limiting disease, their substitute decision makers, and HCPs.8 Reflecting this expectation, institutional, medical, and public campaigns have used the approach to promote advance care planning.8–10

The impact of such programs, however, has been disappointing. Numerous barriers have been identified that seem to overwhelm the guides’ effectiveness.6,10–12 Most recently, surveys describing barriers have included the following: patients’/family members’ struggle to accept poor prognosis, limitations, and complications of treatments; disagreements among patients, family members, and physicians regarding GOC; physicians’ struggles with prognostic uncertainty; and time intensiveness of GOC discussions.6 These authors concluded that research that moves beyond the limitations of retrospective survey data collection is required to advance our understanding of the complexity of communication and decision making for patients approaching the end of their lives.6 Toward that end, this qualitative multicenter study aimed to explore experiences and perspectives of patients with advanced HF, their caregivers, and providers, regarding conversations for patients at risk of dying from HF.

Methods

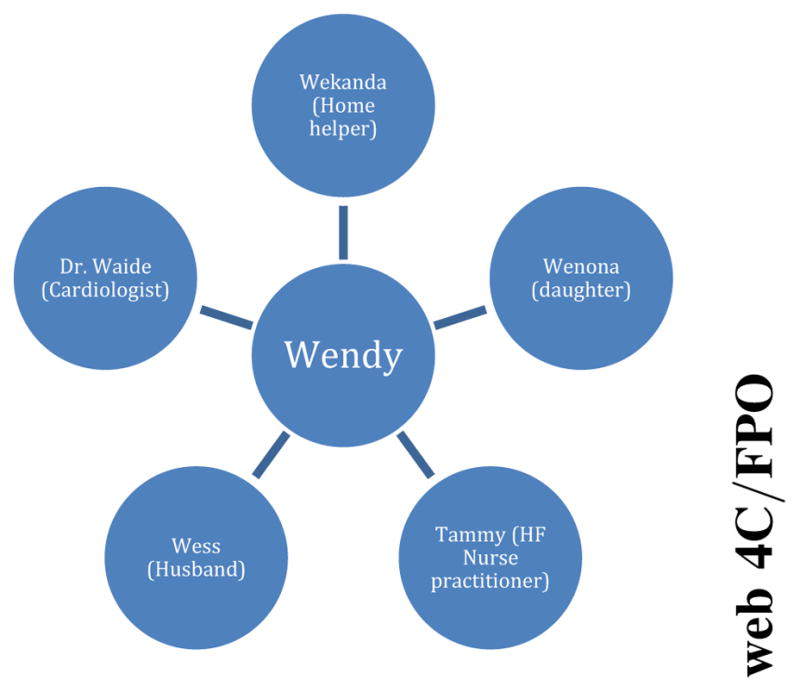

The study used constructivist grounded theory methodology.13,14 Data collection involved an innovative recruitment strategy to explore HF care practices and conversations.15–17 We invited patients with advanced HF (New York Heart Association III or IV) from five study sites in three Canadian provinces to participate in semistructured interviews. Interviews asked patients to reflect on their experience of living with HF, and their goals, needs, concerns, and hopes for the future. At the end of each interview, participants were asked to explicitly identify the key members of their health care team—loosely defined as individuals who provide some degree of supportive HF care. Interview protocols from the study have been published previously.18 With the participant’s permission, each patient-identified team member was invited to participate in an interview. Not all team members agreed to participate; a team sampling unit (TSU) was formed when the patient plus at least two additional team members participated in interviews.16 Team members included health professionals (e.g., cardiologist, family physician, HF nurse practitioner, social worker, and specialists such as respirologist, nephrologist, PC physician), family caregivers (e.g., daughter, spouse, roommate, close friend), and community members (e.g., minister, neighbor, regular taxi driver). Figure 1 illustrates the TSU for patient Wendy (pseudonym). Key informants, identified as practicing experts in the field, were interviewed as a form of triangulation, to review our initial findings and challenge, refine, or elaborate our interpretations with attention to relevance to practice.19 All interviews were audiorecorded, transcribed verbatim, and deidentified with pseudonyms assigned for each participant. The Research Ethics Board at each site approved this study.

Fig. 1.

Team sampling unit for Wendy (all names are pseudonyms).

Sensitizing concepts from complex adaptive systems (CASs) theory informed the data collection and analysis procedures.20 CAS is a useful orientation toward complex problems in which the parts are not fully knowable, interact unpredictably, and produce unintended outcomes.21 Greater than the sum of its parts, a CAS’ individual components are best approached as entangled and dynamically interacting.22,23 These concepts from CAS theory informed both our TSU method of data collection and our analytical approach, which emphasized relationships among the parts of the HF care team over the parts (individuals) themselves.

A multidisciplinary research team including PC providers, cardiologists, family physicians, a psychiatrist, and social scientists analyzed the data, going from open to focused to more interpretive, conceptual stages of coding.13,14 Transcripts were coded using words or phrases that described participants’ experiences and perspectives that were then grouped into preliminary themes. As these themes came into better focus, subgroups of research team members were organized to take forward the iterative in-depth analysis. L. L. participated in all analytical subgroups to help trace relationships among themes and keep analytical groups mutually informed. Published articles describing findings from these analyses include the following: who patients identify as their HF care team;17 how teams work adaptively in response to emerging system issues;16 and how team members converge and diverge in their perceptions of and approaches to the HF care needs of the patient.18

This is the first article from the study to focus on the issue of how HF team members perceive and experience conversations relating to death and dying and GOC. A subset of the research team—including four providers practicing in PC—(A. M. C., K. A. L., L. L., D. M., J. S., and V. M. S.) met regularly to conduct the iterative analysis focused on this theme, initially termed The Conversation. Sufficiency of data14 was judged to be met when all thematic categories were thoroughly described and their inter-relationships mapped.

Results

Our data set included 209 individual interviews clustered into 50 TSUs. Each TSU consisted of an index patient and 2–19 other individuals, including a variety of health professionals, family members, and other caregivers (Table 1).17

Table 1.

Index Patients: Demographics17

| Index Patients | Sex, n (%)

|

Age Range | Followed by HF Clinic, n (%) | Palliative Care Consult, n (%) | Deaths During Study Period, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||||||

| All sites | 62 | 45 (73) | 17 (27) | 39–93 | 49 (79) | 5 (8) | 7 (11) |

| Site 1 | 19 | 13 (68) | 6 (32) | 49–91 | 18 (95) | 0 (0) | 3 (16) |

| Site 2 | 12 | 8 (67) | 4 (33) | 52–92 | 6 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Site 3 | 11 | 8 (73) | 3 (27) | 39–93 | 9 (82) | 1 (9) | 4 (36) |

| Site 4 | 12 | 9 (75) | 3 (25) | 46–91 | 9 (75) | 4 (33) | 0 (0) |

| Site 5 | 8 | 7 (88) | 1 (12) | 54–84 | 7 (88) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

HF = heart failure.

Every TSU contained references to conversations relating to death, either in patient, caregiver, or health professional interviews, or across multiple interviews. Participants’ reflections about these conversations fell into two broad categories: instrumental dimensions and existential dimensions. These categories are described later with illustrative quotations; to ensure confidentiality, all participants were given a pseudonym.

Instrumental Dimensions of Conversations Relating to Death and Dying

Instrumental dimensions refer to participants’ reports regarding the operations of the conversation. These were:

Descriptions about how conversations were planned, initiated, and conducted; including triggers and potential barriers, and

Their perceptions about potential triggers for, and barriers to, these conversations.

A few participants’ portrayed conversations about death and dying as a routine part of HF care. For instance, one participant depicted a smooth and straightforward exchange: the family physician “was very blunt … ‘you’re dying’, and I said ‘well, what chance’ and he said ‘well, about 1 in 5 chances of living very long’. (Edward)” More commonly, however, participants described these conversations as delicate maneuvers, dependent on particular triggers for their initiation, and subject to a number of potential barriers. The main triggers described by health professional participants included a change in clinical status, a patient’s initiation, or a required organizational guide. As one physician summarized:

there are two big times …One is if the patient opens the door and when the patient says, what’s my outlook here? …how long have I got? What’s going to happen to me? And the other time is the crisis time when they’re struggling and it’s appearing that we’re not going to be able to get them a lot better (Dr. N. [family physician]).

The presence of such triggers, however, did not guarantee that a decision-making conversation would occur. Participants described at length barriers such as prognostic uncertainty, insufficient time, and role perception. As one cardiologist explained, “It’s a very difficult topic to discuss, because prognosis can be difficult to estimate.” (Dr. T). Insufficient consultation time could cause physicians “not even to broach the subject because … it’s going to take 20, 30 or more minutes that you do not have” (Dr. M. [cardiologist]). Furthermore, there was no consensus about who was responsible for the conversations. On the one hand, family physicians expressed that such conversations were “the family physician’s job” (Dr. O. [family physician]). However, they also asserted their need for other team members to play a role: “I’m … happy to have the critical conversations. But, it’s pretty difficult to have them if a cardiologist has never said to them ‘There’s nothing more we can do for you.”’ (Dr. Q. [family physician]).

Existential Dimensions of Conversations Regarding Death and Dying

We characterized as existential dimensions any participant report regarding psychological aspects of conversations relating to death and dying, particularly issues of mortality and its avoidance. Existential dimensions included three main subthemes:

Evasive maneuvers,

Powerful emotions, and

Death without dying

Evasive maneuvers were any instance in which patients, families, or HCPs reported avoiding conversations about or knowledge of the patient’s health status. One form of evasion was refusing to engage in a palliative approach to care, as a patient reflected on past experiences: “Every time I’ve been in the hospital someone has come [to have conversations] … And, I always say, ‘I do not want you.’ (Siegfried [patient]).”

Patients’ evasive maneuvers often prompted similar evasions by their HCPs, who acknowledged following the patient’s lead in this regard because of prognostic uncertainty or a desire to protect the patient’s feelings, or both:

If I get a signal from a patient …, that they’re not ready to talk about it, I back off in a hurry. If I get the signal that they do not want to hear about that, well … I’m going to go where the patient is at. (Dr. U. [family physician]).

Even when HCPs endeavored to have a conversation regarding death and dying, information about mortality could be evaded. For instance, a patient’s spouse admitted that learning her husband could die “was a shock because, they may have been saying it, and I just wasn’t hearing it …I did not want to hear it so I did not hear it. (Annie [wife]). Similarly, Diane perceived her mother to be unconsciously avoiding information about her impending death:

If she sits down and makes plans it’s admitting … that things are not going the way she wanted them to … that she is not healthy. So by not telling me everything that the doctors are telling her, she does not have to contend with making those plans and those choices … (Diane [daughter]).

Although many HCPs and family participants reported frustration or concern about such evasive maneuvers, they nevertheless respected them and did not advocate for pushing a patient or family member past this stance.

The second existential dimension subtheme was the emotional power within conversations regarding death and dying. One family member described her experience of a conversation about her father as horrible. (Respondent is crying.) … When they say that his heart does not function as much as it should, it’s not nice to hear that … he’s going to die. (Continues crying.) And you do not have any control over it … (Nancy [daughter]).

The presence of such powerful emotions could fundamentally limit decision-making and planning conversations. Wenona described in detail her attempt to assist her mother in planning for her death, which was going well while they were dealing with simple planning details such as “’would you want a window open, would you want music playing?’ So we were able to get her to talk about that and we wrote it down.” However, Wenona has been unable to help her mother move past such concrete details to grapple with the fundamental issue of her mortality:

As soon as you start to move towards, ‘Do you want CPR?’ … Mom just kind of sat there looking horrified … It just could not come out of her mouth. She still just kind of looked at me like, ‘I do not want to think about this right now. I do not want to talk about it. I think I’m going to make lunch.” (Wenona [daughter]).

This example illustrates vividly how, even with ongoing communication within a supportive family relationship, conversations relating to planning for death and dying can be stifled by powerful emotions.

Many HCP participants related similar experiences in which the patient’s powerful desire to live hindered the development of a plan for dying. One nephrologist recounted seeing a long-time patient who “was ticked off as all get out because [palliative care] was talking about dying at home and keeping him comfortable and he just rejected all of that .... He sure as heck wasn’t ready to die.” (Dr. Ti. [nephrologist]).

The third existential dimension of these conversations was death without dying. This theme captured a pattern in the data of team members focusing on the fact of death without attending to the process of dying. There was a conspicuous paucity of attention to the process of dying in our data. Despite discussion about death, the concept of dying—which could be a period of terminal functional decline before an expected death—rarely occurs in the data set. Some participants acknowledged death as being close, yet it remained disconnected from current day events, off in the future, or ignored entirely despite imminent risk. As three HCPs eloquently asserted: “[Discussions focus on] their will and their burial plot, but that space in between, where they are dying, is something that I think people are wholly unprepared for … I mean, death, yes, but how you die, no.” (key informants).

A recurring instance of this lack of attention to the dying process involved the issue of do-not-resuscitate (DNR)/code status orders. HCP participants reported stories of hospitalized patients with advanced HF who should have had their risk of sudden death addressed and documented but did not. As one cardiologist complained: “All of a sudden you’re getting called by the nurses frantic because a 93-year old on the ward is starting to crash. You ask, what are the resuscitation orders? Well, there’s nothing in the chart …” (Dr. M. [cardiologist]).

The absence of documented resuscitation status discussions in such cases was a powerful example of potential death without evidence of considering the dying process. However, the presence of a DNR order did not necessarily mean that members of the HF care team conceived of the patient as dying. Even the sickest patients were rarely explicitly characterized as dying and when these patients died, their death was sometimes portrayed as a surprise. For example, after the death of study participant patient Ophelia, her HF nurse, Odessa admitted:

… her dying, it was actually quite shocking. We were surprised. We were not expecting her to die this soon because we were still trying to actively sort out her medical problems. We were quite shocked, even though we know her medical condition was still poor. We were not expecting that.

This team had discussed the potential of death with Ophelia, and she had requested DNR. The instrumental dimension of the code status order was addressed but not the existential issue of acknowledging Ophelia’s dying process despite her evolving severe illness. This example demonstrates her death was instrumentally an expected death, yet, existentially an unexpected death, an example of death without dying.

Discussion

In this study, participants described both instrumental and existential dimensions of conversations relating to death and dying. The instrumental dimensions overlap with known barriers to EOL communication;5,24–27 the existential dimensions, however, represent a novel contribution to our understanding of this genre of communication.

The existing literature on challenges with EOL communication focuses on instrumental issues such as organizational, procedural, and medical barriers.1 This focus reflects the implicit premise that planning for death is, or should be, a predictable and linear practice. Our description of existential dimensions, by contrast, challenges this premise and draws attention to the ways in which conversations relating to death and dying among HF care teams demonstrate features of CASs. In complexity science, the system and external environments are not constant; the system comprises uncertainty and paradox, and the individuals function as independent creative decisionmakers.28 To explore these conversations, we consider the inseparable influences29 of existential on instrumental dimensions where relationships and routines are inseparable. We found that a myriad of existential dimensions, such as evasive maneuvers, powerful emotions, and death without dying infuse conversations relating to death.

Evasive maneuvers depicted patients and/or families avoiding the conversation or not hearing the message, and HCPs avoiding the conversation as they grapple with prognostic uncertainty, and respect for patient preferences for information shared. Powerful emotions limit decisionmaking even within a supportive family relationship, and when confronted with these factors, HCPs were found to redirect conversations away from the focus on and planning for death. Our moniker death without dying relates to our observations that conversations could include current illness discussion and planning for eventual death but startlingly omit planning for or reference to the dying process. Under-recognition of the dying process can be problematic; as overdiagnosing or underdiagnosing dying alters health care decisions30 and undermines dying as a reliable trigger for such conversations. It would seem that a variety of existential dimensions impacted the nature of these conversations, and we would argue that attending to emergent aspects of the existential dimensions should be expected and navigated.

Some existing EOL conversation guides acknowledge existential dimensions but may oversimplify them.31,32 Minimizing the existential and overemphasizing the instrumental components in these conversations may result in a checklist of steps to ascertain the patient preferences,1 sidestepping the practical possibility that the patient’s preference may be to evade the conversation altogether. Checklist-driven approaches are useful only once the complex problem has been understood.28 We speculate that the oversimplification of existential dimensions may explain the limited impact of popular EOL communication guides.6,33 For example, in the study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT),33 the lack of change in decisionmaking despite deliberate environmental interventions may represent this very phenomena. It has been argued that the SUPPORT study insufficiently addressed the deeply held desire of patients “to not be dead,”34 something categorized as an existential dimension of the conversation.

Palliative providers have recognized that existential issues complicate experiences around death, prompting attention to relationships, meaning making, spirituality, and legacies.31,32,35 The barriers and opportunities for training regarding existential and/or spiritual experiences are being explored.36 Training aimed at existential caring for oncology and hospice nurses bolstered their confidence in communication about existential issues but did not improve their attitudes toward the care of dying patients. It remains to be determined if patient or family dying experiences are impacted by these heightened nursing skills.37 Nursing care approaching their patient’s spiritual and existential suffering is challenging: rewarding if the patient finds peace but creating professional helplessness if the patient does not.38 In addition, guidelines suggest that PC teams attend to existential concerns.39 Recently, chaplains integrated in PC programs report to being involved in relationship building, existential distress, GOC discussions, and care at the time of death.40

The power and inescapability of existential dimensions within conversations relating to death is well illustrated by the theory of mortality salience, which posits that the awareness of one’s own mortality creates existential anxiety.41 Solomon et al.41 theorizes that humans manage the terror of being mortal through a predictable set of behaviors born out in the theory of terror management, including distancing oneself from the notion of death, aligning with others who have similar values, and striving for immortality. Accordingly, conversations relating to one’s death, regardless of how they are instrumentally set up, act as mortality salience triggers, provoking existential behaviors in individuals engaged in these conversations.41 Therefore, not only do patients and families evade existential discussions about dying but also HCPs, policymakers, and health system designers may as well. This may help to explain how expert clinicians in our study could report being surprised by the death of a severely ill patient, or, their inclination to respect patients’ lead in evading discussion of death and dying. Lannaman et al.42 argued that conversations regarding death and dying are awkward and out of context in a curative setting. A conversational impasse is established as patients claim they want bad news and to discuss dying, yet, avoid this in their crisis, whereas physicians wanting EOL conversations are motivated to avoid them. The field needs to acknowledge this fundamental tension and do more than instrumentalize it as a set of steps to follow, triggers to respond to, or barriers to overcome.

Existential dimensions of conversations relating to death and dying, we would contend, can overpower the best-laid instrumental plans. Decisionmaking for patients with HF is complex and occurs across family relationships, health care roles and systems such as community care, family medicine, cardiac, renal and PC, and locations of care such as home, clinic, and hospital, while the patient’s health state and preferences evolve. Complex systems are difficult to understand, describe, predict, and manage, and their problems are rarely amenable to simple solutions29 such as straightforward EOL conversation guides. Fortunately, complexity science theorizes that problems can be moved forward even if they cannot be solved.28 In light of this, we support further advancing existential initiatives36–40 as core components of future research exploring conversations and decision-making for dying and death as a CAS to help us achieve more meaningful caring for patients dying with HF.

Limitations

Our institutional research ethics approval required that explicit discussions about death and dying with patients or caregivers occurred only if these participants initiated them. Consequently, patient and care-giver narratives about death and dying were emergent and variable across the sample, and it is possible that patient participants had had EOL conversations that they did not mention in the interview. Our TSU methodology offered the opportunity to learn of such conversations from other team members but not to understand the patient’s experience if they did not offer it. HCPs, however, were explicitly asked about their perspectives regarding PC integration for HF and EOL conversations.

Conclusion

Conversations relating to death and dying for patients at risk of dying from HF have both instrumental and existential dimensions. Existential dimensions should be expected and navigated because they influence relationships in ways that impact EOL communication routines. The power of such existential dimensions may explain why our current focus on the instrumental dimensions of EOL conversations has been insufficient. To improve communication relating to death and dying for HF patients, we need to also attend to existential dimensions, especially in terms of their impact on the occurrence of these conversations, the nature of relationships and responses within these conversations, and the fluidity of meaning within these conversations.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support from the Heart Failure/Palliative Care Teamwork Research Group: Malcolm Arnold, Joanna Bates, Fred Burge, Samuel Burnett, Sherri Burns, Karen Harkness, Gil Kimel, Donna Lowery, Allan McDougall, Robert McKelvie, Laura Nimmon, Stuart Smith, Patricia Strachan, Glendon Tait, and Donna Ward. They also thank Dr. Sheldon Solomon for his support in aiding their understanding and discussion regarding mortality salience. They acknowledge that Table 1 in this article is reprinted from an open access journal.17 The authors received financial support for the research of this article from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and it was supported by the Innovation Fund of the Alternative Funding Plan of the Academic Health Sciences Centers of Ontario.

References

- 1.Bernacki RE, Block SD for American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1994–2003. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.You JJ, Fowler RA, Heyland DK for Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network (CARENET) Just ask: discussing goals of care with patients in hospital with serious illness. CMAJ. 2014;186:425–432. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harding R, Selman L, Beynon T, et al. Meeting the communication and information needs of chronic heart failure patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36:149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strachan PH, Ross H, Rocker GM, Dodek PM, Heyland DK for Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network (CARENET) Mind the gap: opportunities for improving end-of-life care for patients with advanced heart failure. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25:635–640. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(09)70160-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Momen NC, Barclay SIG. Addressing ‘the elephant on the table’: barriers to end of life care conversations in heart failure—a literature review and narrative synthesis. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2011;5:312–316. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e32834b8c4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.You JJ, Downar J, Fowler RA, et al. For Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network (CARENET) Barriers to goals of care discussions with seriously ill hospitalized patients and their families: a multicenter survey of clinicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:549–556. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, et al. SPIKES—a six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5:302–311. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-4-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hewison A, Lord L, Bailey C. “It’s been quite a challenge”: redesigning end-of-life care in acute hospitals. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13:609–618. doi: 10.1017/S1478951514000170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Speak up. [Accessed August 31, 2016];What is advance care planning? Available from www.advancecareplanning.ca/what-is-advance-care-planning/

- 10.National POLST Paradigm. [Accessed August 31, 2016];POLST & advance care planning. Available from polst.org/polst-advance-care-planning/

- 11.Butler M, Ratner E, McCreedy E, Shippee N, Kane RL. Decision aids for advance care planning: an overview of the states of the science. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:408–418. doi: 10.7326/M14-0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan RJ, Webster J. End-of-life care pathways for improving outcomes in caring for the dying. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD008006. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008006.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: SAGE; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. 2. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lingard LA, McDougall A, Schulz V, et al. Understanding palliative care on the heart failure care team: an innovative research methodology. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:901–911. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tait GR, Bates J, LaDonna KA, et al. Adaptive practices in heart failure care teams: implications for patient-centered care in the context of complexity. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2015;8:365–376. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S85817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LaDonna KA, Bates J, Tait GR, et al. for Heart Failure/Palliative Care Teamwork Research Group. ‘Who is on your health-care team?’ Asking individuals with heart failure about care team membership and roles. Health Expect. 2016;20:198–210. doi: 10.1111/hex.12447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lingard L, Sue-Chue-Lam C, Tait GR, et al. for Heart Failure/Palliative Care Teamwork Research Group. Pulling together and pulling apart: influences of convergence and divergence on distributed healthcare teams. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s10459-016-9741-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thurmond VA. The point of triangulation. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2001;33:253–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stacey RD, Griffin D, Shaw P. Complexity and management: Fad or radical challenge to systems thinking? 1. New York: Routledge; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zimmerman B, Lindberg C, Plesk P. Edgeware: Lessons from complexity science for health care leaders. 2. Irving, CA: VHA Incorporated; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Capra F. The web of life: A new scientific understanding of living systems, 1st ed. New York: Anchor Books; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stacey RD. Ways of thinking about public sector governance. In: Stacey RD, Griffin D, editors. Complexity and the Experience of Managing in Public Sector Organizations. London: Routledge; 2006. pp. 15–39. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gadoud A, Jenkins SMM, Hogg KJ. Palliative care for people with heart failure: summary of current evidence and future direction. Palliat Med. 2013;27:822–828. doi: 10.1177/0269216313494960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnes S, Gott M, Payne S, et al. Communication in heart failure: perspectives from older people and primary care professionals. Health Soc Care Community. 2006;14:482–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Low J, Pattenden J, Candy B, Beattie JM, Jones L. Palliative care in advanced heart failure: an international review of the perspectives on recipients and health professionals on care provision. J Card Fail. 2011;17:231–252. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barclay S, Momen N, Case-Upton S, Kuhn I, Smith E. End-of-life care conversations with heart failure patients: a systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:e49–e62. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X549018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fraser SW, Greenhalgh T. Coping with complexity: educating for capability. BMJ. 2001;323:799–803. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7316.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kannampallil TG, Schauer GF, Cohen T, Patel VL. Considering complexity in healthcare systems. J Biomed Inform. 2011;44:943–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parry R, Seymour J, Whittaker B, Bird L, Cox K. NHS National End of Life Care Programme: Sue Ryder Care Centre for the Study of Supportive, Palliative and End of Life Care. The University of Nottingham; Nottingham, UK: 2013. [Accessed December 1, 2016]. Rapid evidence review: Pathways focused on the dying phase in end of life care and their key components. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/212451/review_academic_literature_on_end_of_life.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Block SD. Perspectives on care at the close of life. Psychological considerations, growth and transcendence at the end of life: the art of the possible. JAMA. 2001;285:2898–2905. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.22.2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The Conversation Project. [Accessed September 6, 2016]; Available at: http://theconversationproject.org/

- 33.Connors AF, Dawson NV, Desbiens NA for the SUPPORT Principal Investigators. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients: the study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT) JAMA. 1995;274:1591–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finucane TE. How gravely ill becomes dying: a key to end-of-life care. JAMA. 1999;282:1670–1672. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.17.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chochinov HM, Kristajanson LJ, Breitbart W, et al. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:753–762. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70153-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keall R, Clayton JM, Butow P. How do Australian palliative care nurses address existential and spiritual concerns? Facilitators, barriers and strategies. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23:3197–3205. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henoch I, Danielson E, Strang S, Browall M, Melin-Johansson C. Training intervention for health care staff in the provision of existential support to patients with cancer: a randomized, controlled study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46:785–794. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tornøe KA, Danbolt LJ, Kvigne K, Sørlie V. The challenge of consolation: nurses’ experiences with spiritual and existential care for the dying—a phenomenological hermeneutical study. BMC Nurs. 2015;14:62. doi: 10.1186/s12912-015-0114-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. [Accessed April 1, 2017];National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care: Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. (3). Available at: http://www.nationalconsensusproject.org/DisplayPage.aspx?Title=Summary%20of%202013%20Revisions.

- 40.Jeuland J, Fitchett G, Schulman-Green D, Kapo J. Chaplains working in palliative care: who are they and what they do. J Palliat Med. 2017;20:502–508. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Solomon S, Greenberg T, Pyszczynski T. The worm at the core: On the role of death in life. New York: Random House; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lannamann JW, Harris LM, Bakos AD. Ending the end-of-life communication impasse: a dialogic intervention. In: Sparks L, O’Hair D, Kreps G, editors. Cancer, Communication, and Aging. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press; 2008. pp. 293–318. [Google Scholar]