Abstract

Aims

Opioid dependence is associated with high morbidity and mortality. Buprenorphine (BUP) is approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat opioid dependence. There is a lack of clear consensus on the appropriate dosing of BUP due to interpatient physiological differences in absorption/disposition, subjective response assessment and other patient comorbidities. The objective of the present study was to build and validate robust physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models for intravenous (IV) and sublingual (SL) BUP as a first step to optimizing BUP pharmacotherapy.

Methods

BUP‐PBPK modelling and simulations were performed using SimCyp® by incorporating the physiochemical properties of BUP, establishing intersystem extrapolation factors‐based in vitro–in‐vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) methods to extrapolate in vitro enzyme activity data, and using tissue‐specific plasma partition coefficient estimations. Published data on IV and SL‐BUP in opioid‐dependent and non‐opioid‐dependent patients were used to build the models. Fourteen model‐naïve BUP‐PK datasets were used for inter‐ and intrastudy validations.

Results

The IV and SL‐BUP‐PBPK models developed were robust in predicting the multicompartment disposition of BUP over a dosing range of 0.3–32 mg. Predicted plasma concentration–time profiles in virtual patients were consistent with reported data across five single‐dose IV, five single‐dose SL and four multiple dose SL studies. All PK parameter predictions were within 75–137% of the corresponding observed data. The model developed predicted the brain exposure of BUP to be about four times higher than that of BUP in plasma.

Conclusion

The validated PBPK models will be used in future studies to predict BUP plasma and brain concentrations based on the varying demographic, physiological and pathological characteristics of patients.

Keywords: buprenorphine, intravenous, opioid dependence, PBPK, pharmacokinetics, sublingual

What is Already Known about this Subject

Opioid dependence has no cure and is associated with high morbidity and mortality.

Buprenorphine (BUP) is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of opioid dependence.

Currently, there is a lack of clear consensus on BUP dosing due to interpatient physiological differences, subjective response assessments and comorbidities.

What this Study Adds

Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models of intravenous (IV) and sublingual (SL) BUP were developed and validated using 14 independent BUP PK studies among healthy opioid‐dependent and non‐opioid‐dependent patient populations.

These models are robust in predicting IV and SL BUP exposure following single and multiple BUP doses up to 32 mg.

Introduction

Drug overdose and associated deaths have become a nationwide crisis in the United States 1. Data from the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that deaths associated with drug overdose are predominantly driven by the increase in opioid abuse 2, 3, 4. Broadly speaking, the term ‘opioid’ applies to any endogenous or exogenous substance that interacts with the opioid receptors present in the body 5. Because of their efficacy in pain management, prescription opioids, such as morphine, hydromorphone, oxycodone, hydrocodone and fentanyl are routinely used in patients 6. Besides blocking the pain signalling pathway, opiates also activate the brain reward system and produce euphoric effects. This makes them highly addictive with prolonged exposure 7, 8.

Opioid dependence is associated with high morbidity and mortality 9, 10, and there is no cure for it. Medication‐assisted maintenance therapies can reduce the complications of opioid dependence, as a means of decreasing illicit drug use 11, 12. Currently, methadone, buprenorphine (BUP) and naltrexone are the three primary pharmacotherapies approved for treating opioid dependence. The effectiveness of methadone as a maintenance treatment for opioid dependence has been demonstrated in many clinical studies 13, 14. As a full mu‐opioid receptor agonist, methadone has the potential for abuse; consequently, methadone maintenance treatment requires daily patient clinic visits for dosing. Naltrexone is a mu‐opioid receptor antagonist; it can reduce illicit drug use by blocking euphoric effects and has no potential for abuse, but poor patient retention hampers its routine clinical use 11, 15.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved BUP for treating opioid addiction in 2002. Compared with methadone, BUP is a relatively new drug that has several advantages in clinical practice. BUP exhibits a mixed agonist–antagonist opioid effect 16, 17, and is highly specific towards kappa (antagonist) and mu (partial agonist) opioid receptors; it is roughly 50–100 times more potent than morphine 18. BUP has a ceiling dose–response profile, which limits the risk of major life‐threatening adverse effects associated with mu‐opioid receptor agonists such as respiratory depression 19. Because of this profile, BUP can provide competitive antagonism to other illicit opioids. In recent times, a sublingual (SL) formulation of BUP (Subutex®) has been shown to be more favourable due to its safety profiles and ease of administration 20. Suboxone®, a SL BUP formulation in combination with naloxone (full mu‐opioid receptor antagonist), is another product which was developed and approved to avoid intravenous (IV) abuse.

Despite the proven efficacy of BUP in treating opioid addiction, a meta‐analysis showed that patients on BUP had 1.26 times the relative risk of discontinuing the treatment compared with patients receiving methadone 14. In addition, a randomized phase IV study found BUP to be associated with a 54% patient dropout rate compared with 26% in the methadone group 21. Several factors can have an impact on the outcomes of BUP therapy and in turn affect its compliance – e.g. the lack of clear consensus on induction and on a maintenance dosing regimen for BUP; subjectivity of the clinical opioid withdrawal (COW) scale that is used to determine the dose 22; and the confounding effects of factors such as mental health comorbidities and smoking, as well as concomitant medication use that can confound COW scoring and the selection of improper BUP dosing. In addition, there is high interpatient variability in the bioavailability of BUP due to differences in the extent of SL absorption 23.

A better understanding of the physiological and drug formulation parameters affecting BUP pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic profiles is needed to develop a more objective dosing regimen of BUP. Physiologically based PK (PBPK) modelling is a comprehensive and relatively inexpensive strategy to address the impact of various clinical pharmacotherapeutic factors that affect drug dosing. The PBPK modelling approach incorporates a drug's physiochemical properties, human physiological variables and population variability estimates to predict drug exposure 24. As population PBPK models incorporate anatomical, physiological and metabolic attributes, any physiological alterations induced by disease, age, gender, genetic polymorphism and other pathophysiological conditions can be captured by such a model. To the best of our knowledge, the use of PBPK modelling in predicting BUP exposure has not been explored in adult populations. The objective of the present study was to build robust, validated PBPK models for IV and SL BUP formulations in an attempt to be able to predict the impact of patient covariates on the optimal dosing of BUP in patients.

Methods

BUP PBPK modelling and simulations were conducted using the SimCyp® population‐based simulator v15.1 (Simcyp Limited, Sheffield, UK). WinNonLin software (Phoenix WinNonLin®: version 6.4, Pharsight Corp, Mountainview, CA, USA) was used to simulate steady‐state exposure after administration of the SL formulation. A systematic and extensive literature search in MEDLINE through Pubmed was performed to identify published physicochemical properties (Table 1), plasma protein binding, in vitro disposition and metabolic profiles of BUP. Similar strategies were used to identify published clinical trials using IV and SL BUP (Tables 5, 8 9). These data were tabulated and digitized, where necessary, for PBPK model building or model validation. The bibliographies of selected articles were also reviewed to identify additional relevant information. GetData Graph Digitizer V.2.26 25 was used to digitize published BUP clinical PK data.

Table 1.

Summary of buprenorphine physiochemical parameters

| Parameter | Value | Source/reference |

|---|---|---|

| MW (g mol –1 ) | 467.64 | Pubchem/DrugBank |

| Log P o:w | 4.98 | Avdeef et al. 26 |

| Compound type | Diprotic base | |

| pKa1, pKa2 | 9.62, 8.31 | Avdeef et al. 26 |

| B/P | 0.55 | Mistry et al. 27 |

| f u a | 0.03 | Walter et al. 28 |

B/P, blood to plasma partition coefficient; fu, plasma fraction unbound; logPo:w, logarithm of the octanol to water partition coefficient; MW, molecular weight; pKa, negative logarithm of the acid dissociation constant

fu was fitted by a nonlinear mixed‐effect modelling strategy using the parameter estimation module of Simcyp. The Nelder–Mead method was used for the minimization. An fu value of 0.04, published by Walter et al. 28, was used as the initial estimate

General workflow for model building and model validation

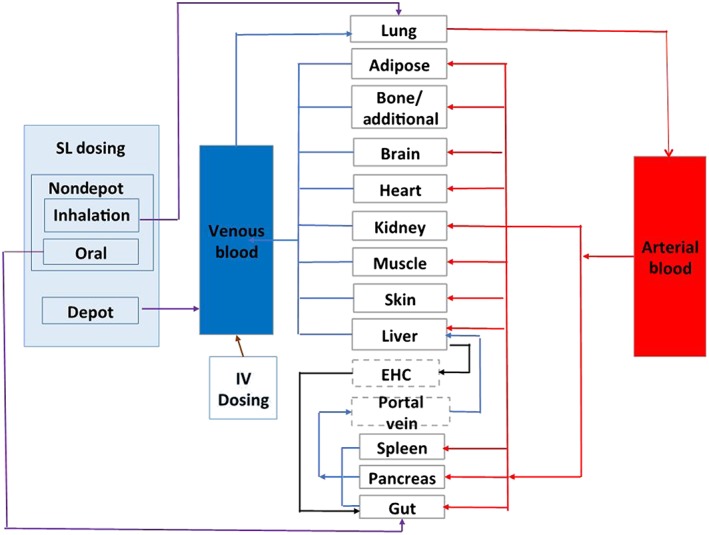

A full PBPK model was initially developed for the IV BUP formulation using physiochemical properties (Table 1) 26, 27, 28, (Table 2) in vitro metabolic profiles (Tables 3, 4) 29, 30, 31 and published IV BUP clinical PK data in healthy subjects (Table 5). In the IV model, BUP was modelled to enter the systemic circulation through venous blood (Figure 1). Several model‐naïve IV BUP clinical PK datasets were used to perform inter‐ and intrastudy validations by comparing the mean area under the plasma drug concentration–time curve (AUC) and the observed maximum concentration (Cmax) after administration of a dose between the observed and predicted data. After establishing a validated IV BUP PBPK model, an SL BUP PBPK model was built by incorporating an SL absorption component to the IV model. The SL route of administration involves a drug being absorbed through the reticulated vein underneath the oral mucosa, and then enter systemic circulation via the facial vein, in addition to a portion of the formulation being swallowed orally 32. In order to simulate this, we built a customized administration route that involved the inhalation route to mimic the SL absorption, oral absorption to mimic the portion of the drug that is swallowed, and a depot release component to mimic the slow release of drug from the buccal tissue into the systemic circulation (Figure 1). Following model building for the SL route, we performed inter‐ and intrastudy validations similar to those for the IV model by comparing the mean AUC and Cmax values of the predicted model and observed data. Model performance was assessed by inter‐ and intrastudy validations. For the intrastudy validations, we used the clinical PK data from different dosing ranges from the same study that was used to build the PBPK profiles. For interstudy validations, we used data from several model‐naïve clinical PK studies that were not used in model building. For the validations, we performed visual plots of fitted and data predicted against the observed mean concentration–time profiles. The 5th to 95th percentile intervals (PIs) were calculated to show the overall interpatient variability. The goal was to use IV and SL BUP PBPK models to predict AUC, which represents the systemic exposure over time following a dose, and compare it with the observed data. The criterion for model validation was that the difference between the mean predicted and observed AUC in 100 virtual subjects should fall ±25% for the IV model and ±50% for the SL model. A wider criterion was chosen for the SL model to mimic extent of the inherent interpatient variability in dose administration and absorption.

Table 2.

Distribution parameters for the buprenorphine profile

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Model | Full PBPK |

| V ss (l kg –1 )‐predicted a | 2.48 |

| V ss (l kg –1 )‐observed b | 2.77 |

| Tissue partition coefficients (K p ) | |

| Adipose | 0.0044 |

| Bone/additional c | 35 |

| Brain | 3.41 |

| Gut | 2.69 |

| Heart | 0.83 |

| Kidney | 1.29 |

| Liver | 2.13 |

| Lung | 0.29 |

| Pancreas | 2.20 |

| Muscle | 1.31 |

| Skin | 1.60 |

| Spleen | 1.31 |

| K p scalar d | 0.225 |

PBPK, physiologically based pharmacokinetic; Vss, Volume of distribution at steady state

Vss predicted and Kp values for all tissue were predicted by the corrected Poulin and Theil method 35, 36, 37

Bullingham et al. 33

The bone/additional compartment Kp value was optimized using the Simcyp® parameter estimation module, and the Nelder–Mead method was used for the minimization. The predicted Kp value, 3.73, by the Poulin and Theil method, was used as the initial value, and (0.001, 100) as the boundaries

Kp scalar was optimized using the Simcyp® parameter estimation module, and the Nelder–Mead method was used for the minimization. The default Kp scalar, 1, was used as the initial value, and (0.01, 100) as the boundaries.

Table 3.

Intrinsic clearance and intersystem extrapolation factor (ISEF) values associated with enzymes primarily involved in buprenorphine metabolism

| Enzyme | Value | Source/reference |

|---|---|---|

| CYP3A4 | ||

| V max (pmol min –1 per pmol of isoform) | 10.4 | Picard et al. 29 |

| K m (μM) | 13.6 | Picard et al. 29 |

| f umic | 0.1 | Cubitt et al. 30 |

| ISEF | 2.355 | Calculated from Equation (3) |

| CYP2C8 | ||

| V max (pmol min –1 per pmol of isoform) | 1.4 | Picard et al. 29 |

| K m (μM) | 12.4 | Picard et al. 29 |

| f umic | 0.1 | Cubitt et al. 30 |

| ISEF | 8.33 | Calculated from Equation (3) |

| UGT1A1 | ||

| Cl int (μl min –1 per pmol of isoform) | 0.0162 | Oechsler et al. 31 |

| f umic | 0.1 | Cubitt et al. 30 |

| ISEF | 0.636 | Calculated from Equation (3) |

| UGT1A3 | ||

| Cl int (μl min –1 per pmol of isoform) | 0.0155 | Oechsler et al. 31 |

| f umic | 0.1 | Cubitt et al. 30 |

| ISEF | 6.65 | Calculated from Equation (3) |

| UGT2B7 | ||

| Cl int (μl min –1 per pmol of isoform) | 0.0116 | Oechsler et al. 31 |

| f umic | 0.1 | Cubitt et al. 30 |

| ISEF | 5.19 | Calculated from Equation (3) |

CLint, sum of Vmax/Km of metabolic pathways; CYP, cytochrome P450; fumic, Fraction of unbound drug in the in vitro microsomal incubation; Km, Michaelis–Menten constant; UGT, UDP‐glucuronosyltransferase; Vmax, maximum rate of metabolism

Table 4.

Values used in Equation (2) to scale recombinantly expressed human cytochrome P450 (CYP) data to the entire human body (adapted from a healthy population in SimCyp®)

| Drug metabolizing enzyme | Abundance (pmol/mg protein) | CV% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2C8 | 24 | 81 | |

| CYP3A4 | 137 | 41 | |

| UGT1A3 | 23 | 36 | |

| UGT2B7 | 71 | 30.4 | |

| UGT1A1 | EM | 48 | 24 |

| PM | 0.42 | 50.8 | |

| IM | 0.72 | 39.9 | |

| UM | 1.46 | 30 | |

| Mean population liver volume (l) | 1.65056 | ||

| Mean population liver density (g l –1 ) | 1080 | ||

| Mean population MPPGL (mg g –1 ) | 39.79066 | ||

With the exception of UGT1A1, only EMs were included for CYP2C8, CYP3A4, UGT1A3 and UGT2B7 in a SimCyp healthy population. CV, coefficient of variation; EM, extensive metabolizer; IM, intermediate metabolizer; PM, poor metabolizer; UM, ultra‐rapid metabolizer; UGT, UDP‐glucuronosyltransferase

Table 5.

Intravenous buprenorphine clinical pharmacokinetic studies

| No. | n | Subject | Age range | Dosage | Cmax | AUC0–∞ | t1/2 | CLtotal | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Male /female) | |||||||||

| (mg) | (ng ml–1) | (ng•h ml–1) | (h) | (l h–1) | |||||

| (years | |||||||||

| 1 | 25 (19/6) | Healthy female and male non‐opioid‐dependent users | 20–53 | 0.3 | 2.32 | 5.20 | 8.6 | 58 | Bai et al. 43 |

| 2 | 6 (6/0) | Healthy male non‐opioid‐dependent users | 32–39 | 2 | 21.6 | 41.4 | 21.8 | 49.8 | Huestis et al. 42 |

| 4 | 56.3 | 75.9 | 27.5 | 53.2 | |||||

| 8 | 110.8 | 153.3 | 28 | 52.4 | |||||

| 12 | 164.5 | 245.1 | 22.3 | 54.7 | |||||

| 16 | 174.8 | 269.1 | 25.6 | 60 | |||||

| 3 | 9 (8/1) | Opioid‐dependent | 21–42 | 4 | 69.7 | 70.4a | 32.1 | NA | Harris et al. 44 |

| 4 | 6 (5/1) | Healthy female and male non‐opioid‐dependent users | 21–38 | 1 | 14.3 | 18.4 | 16.2 | 62.5 | Mendelson et al. 45 |

AUC0–∞, area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0 to infinity after a dose; Cmax: maximum plasma concentration; CLtotal, total clearance; t1/2, half‐life

The AUC from Harris et al. 44 was reported as 0–24 h

Figure 1.

Compartmental structure of the full buprenorphine intravenous (IV) and sublingual (SL) physiologically based pharmacokinetic models. The schematic shows how IV and SL administrations were modelled. EHC, enterohepatic circulation

AUC0–t is the drug exposure between time zero and t hours (the last blood collection time point) and this was estimated using the trapezoidal method. AUC0–∞ is the drug exposure between zero hours and infinity, and this was estimated by the summation of AUC0–t and extrapolated exposure from Clast to infinity (AUClast –∞ = Clast/k), where AUClast –∞ is the area under the curve from the time of dosing to the last measurable concentration, Clast is the concentration corresponding to the last measurable concentration, and k is the terminal disposition rate constant. CLtotal was calculated using the following equation: CL = dose/AUC0–∞. We were also interested in predicting other BUP PK parameters, such as total clearance (CLtotal) and Cmax, as well as their corresponding population variability limits.

IV buprenorphine – PBPK model development

Distribution profile

The volume of distribution at steady state (Vss), 2.77 l kg–1, reported by Bullingham et al. 33, was used as a reference to build the PBPK distribution component. A predicted Vss of 2.48 l kg–1 was estimated using reported BUP physicochemical properties as well as estimated tissue‐to‐plasma partition coefficients (Kp) for all major tissue‐specific physiological compartments (Table 2). Vss (Equation (1)) is estimated by serial addition of plasma volume (Vp), erythrocyte volume (Ve) and volumes associated with each major tissue (Vt) 34.

| (1) |

where E:P represents erythrocyte‐to‐plasma partitioning. The E:P is estimated using the SimCyp® parameter estimation modules based on the blood‐to‐plasma ratio and haematocrit.

Tissue‐specific Kp values for BUP for the full PBPK model were estimated using the corrected Poulin and Theil method 35, 36, 37. Furthermore, sequential sensitivity analysis was performed to identify and optimize tissue Kp values further, utilizing nonlinear mixed‐effects modelling methods. In the final model, Kp estimates for just the bone/additional compartment had to be optimized and Kp values for all other organ and tissues remained as the predicted values. Table 2 summarizes distribution parameters used in the BUP simulations. A hypothetical additional compartment was incorporated along with the bone, and the Kp value for this combined compartment was predicted and optimized using nonlinear mixed effects modelling methods, using the parameter estimator module of Simcyp®.

Clearance profile

BUP is extensively metabolized to nor‐BUP by N‐dealkylation, and both BUP and nor‐BUP are then further conjugated to BUP glucuronide and nor‐BUP glucuronide, respectively 38. The N‐dealkylation is mediated primarily by cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) and CYP2C8, and the glucuronidation is mainly mediated by UDP‐glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A1, 1A3 and 2B7 29, 38, 39, 40. Together, these enzymes are responsible for the majority of BUP metabolism, with a minor contribution from other CYP450 and UGT enzymes. Established in vitro–in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) methods using enzyme‐specific microsomal BUP metabolism parameters and intersystem extrapolation factor (ISEF)‐based estimates were used to extrapolate recombinant in vitro enzyme activities to in vivo intrinsic clearances (Equation (2)) 41.

| (2) |

where CLint is the sum of Vmax/Km of metabolic pathways (i) for each of involved enzyme (j), Vmax is the maximum rate of metabolism, Km is the BUP Michaelis–Menten constant for each individual enzyme, rhCYPs are the recombinantly expressed human cytochrome P450s, MPPGL is the amount of microsomal protein per g of human liver, CYPj abundance is the amount of jth enzyme in pmol for every mg of microsomal protein in the human liver. The CYPj abundance, MPPGL and liver weight are assigned by SimCyp® V.15 for each individual virtual population, which are parts of the predicted population variability (Table 4).

ISEF is used to scale the activity of a unit amount of each enzyme in the recombinant microsomal system to human liver microsomes, and scaling of rhCYP data to the entire human body is accomplished through Equation (2). ISEF values for each drug‐metabolizing enzyme can be calculated with either Vmax and Km or CLint, as given by the following equations:

| (3) |

| (4) |

CYPj abundance (HLM) is the estimated abundance of the jth CYP enzyme in a human liver. The intrinsic clearance of BUP and ISEF values associated with enzymes primarily involved in BUP metabolism are listed in Table 3.

IV BUP clinical PK studies: model validation

BUP clinical PK studies in healthy opioid‐dependent and non‐opioid‐dependent subjects listed in Table 5 were considered for the study. The 72‐h PK profile from Huestis et al. 42 was used for model development (8 mg) and intrastudy validation (2, 4, 12 and 16 mg). One hundred virtual healthy subjects, spread over 10 trials, were used for each PBPK simulation. Data from Bai et al. 43, Harris et al. 44 and Mendelson et al. 45 were used for interstudy validation. As mentioned above, mean AUC was primarily compared between observed datasets and predicted simulations. The population variability from the virtual population is presented in the concentration–time plots as 5th and 95th percentile plots. Due to the lack of individual concentration–time profiles reported for each observed study, and limitations involved in digitizing the observed variability data, we were not able to compare predicted population variability with observed population variability. The basic demographic information such as age and gender were matched when performing the simulations.

SL BUP PBPK model development

Absorption profile

Modelling and simulation of SL administration is not available in the current version of Simcyp®. A customized depot and nondepot combination approach was used to simulate SL administration. The nondepot component included an inhalation route to mimic the SL arterial absorption of BUP and an oral route to represent the portion of the SL formulation that is swallowed and subjected to absorption and metabolism in the gastrointestinal tract. The depot route of drug absorption was used to mimic the slow release of BUP from surrounding buccal tissue following SL absorption. BUP is a multiphasic drug; the SL and oral components explained two disposition phases, and the depot component explained the disposition during the terminal elimination phase. The percentage contribution of each route is listed in Table 6. A first‐order absorption model was used to predict the oral absorption profile (Table 7).

Table 6.

Sublingual (SL) buprenorphine dosing allocation between depot and nondepot components

| Total SL dose | Depot | Nondepot | Nondepot breakdown | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (37.5% of total dose) | (62.5% of total dose) | SL | Oral | |

| 4 mg | 1.5 mg | 2.5 mg | 10% | 90% |

| 8 mg | 3 mg | 5 mg | 10% | 90% |

| 12 mg | 4.5 mg | 7.5 mg | 10% | 90% |

| 16 mg | 6 mg | 10 mg | 7% | 93% |

| 24 mg | 9 mg | 15 mg | 7% | 93% |

| 32 mg | 12 mg | 20 mg | 7% | 93% |

Table 7.

First‐order absorption model parameter values

| Parameter | Value | Reference/source |

|---|---|---|

| f a | 0.80 | Parameter estimation module |

| K a (1 h –1 ) | 2.34 | Parameter estimation module |

| Q gut (l h –1 ) | 8.12 | Predicted |

| f uGut | 1 | User input |

fa, fraction of absorption; fuGut, unbound fraction within enterocyte; Ka, absorption rate constant; Qgut, nominal flow from gut model

SL BUP clinical PK studies: model validation

BUP clinical PK studies in healthy opioid‐dependent and non‐opioid‐dependent patients listed in Table 8 were used for the study. The 72‐h PK data from Ciraulo et al. 46 were used for model building (8 mg) and intrastudy validation (4, 8, 16 and 24 mg). Data from Harris et al. 47 and McAlear et al. 48 was used for inter‐study validation. Data from Compton et al. 49 and Greenwald et al. 50 were used for the validation of multiple‐dose simulations. One hundred virtual healthy subjects, spread over 10 trials, were used for each of the PBPK simulations.

Table 8.

Sublingual buprenorphine (BUP) clinical pharmacokinetic single‐dose studies considered for modelling

| n | Age range | BUP/NAL | Cmax | AUC0–t a | t1/2 | Tmax | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Subject | (Male/female) | (years) | (mg) | (ng ml–1) | (ng•h ml–1) | (h) | (h) |

| Harris et al. 47 | Healthy female and male non‐opioid‐dependent users | 8 (7/1) | 22–42 | 4/1 | 1.84 | 12.52 | NA | 1.06 |

| 8/2 | 3.00 | 20.22 | NA | 1.01 | ||||

| 16/4 | 5.95 | 34.89 | NA | 0.79 | ||||

| 16/0 | 5.47 | 32.63 | NA | 1.04 | ||||

| McAleer et al. 48 | Opioid‐naïve healthy male subjects | 27 (27/0) | 19–42 | 2/0 | 1.6 | NA | NA | 1.5 |

| 8/0 | 4.0 | 31.81 | 30.02 | 1.02 | ||||

| 12/0 | 5.4 | 41.61 | 25.63 | 1.00 | ||||

| 16/0 | 6.4 | 52.00 | 23.89 | 0.75 | ||||

| 8/2 | 3.2 | 24.55 | 25.51 | 1.00 | ||||

| 8/2 | 3.2 | 24.60 | 26.79 | 1.00 | ||||

| Ciraulo et al. 46 | Healthy non‐opioid‐dependent users | 23 (16/7) | 21–45 | 4/0 | 2 | 9.37 | NA | 1.09 |

| 8/0 | 2.65 | 19.92 | NA | 1.15 | ||||

| 16/0 | 4.42 | 34.94 | NA | 0.94 | ||||

| 24/0 | 5.41 | 48.81 | NA | 0.92 | ||||

| 15 (14/1) | 21–55 | 4/1 | 2.33 | 13.09 | NA | 0.96 | ||

| 8/2 | 3.53 | 23.23 | NA | 1.04 | ||||

| 16/4 | 5.83 | 39.38 | NA | 1.08 | ||||

| 24/6 | 6.44 | 47.55 | NA | 0.96 |

AUC0–t, area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0 to time t after a dose; Cmax, maximum plasma concentration; t1/2, half‐life; NA, not available; NAL, naloxone; Tmax, time to maximum concentration

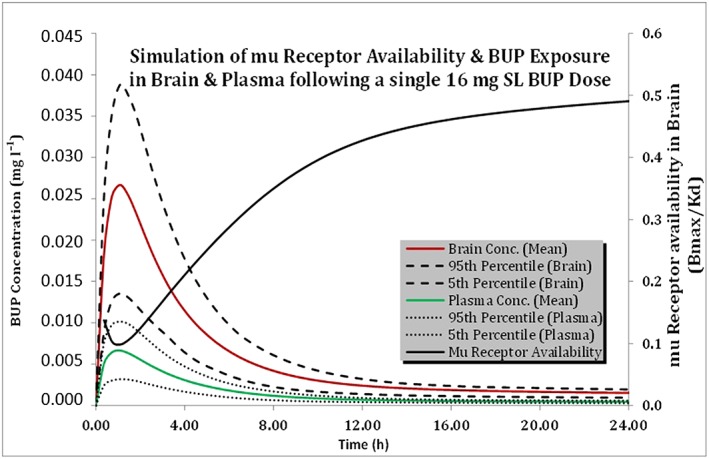

BUP exposure in the plasma and the corresponding mu‐opioid receptor availability were predicted, along with predicted BUP brain concentrations, using the validated SL BUP PBPK model (16 mg dose) and the relationship between plasma concentration and mu‐opioid receptor availability reported by Greenwald et al. 50. The BUP brain Kp value (Table 2) estimated using the corrected Poulin and Theil method 35, 36, 37 was used to simulate the BUP exposure profile in the brain compartment.

Similarly to the IV BUP model validation, mean AUC and Cmax were compared primarily between the observed datasets and predicted simulations. The population variability from the virtual population is presented in the concentration–time plots as 5th and 95th percentile plots. Due to the lack of individual concentration–time profiles reported for each observed study and limitations involved in digitizing the observed variability data in the literature, we were not able to compare predicted population variability with observed population variability. Basic demographic information such as age and gender were matched in the simulations.

Virtual patient population

The Simcyp® virtual healthy volunteer patient population was used to simulate single‐dose IV and SL BUP exposure. During model building and validation steps for both models, demographic details of the reported patient populations in the PK studies considered (Tables 5, 8, 9) were matched with those from the virtual healthy patient population, to avoid altered physiology‐based differences. No changes were made to the Simcyp® healthy volunteer patient population file.

Table 9.

Sublingual buprenorphine (BUP) clinical pharmacokinetic multiple‐dose studies considered for modelling

| Reference | Subject | n (Male/female) | Age range | BUP/NAL | Cmax | AUC0–24 | t1/2 | Tmax |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (years) | (mg) | (ng ml–1) | (ng•h ml–1) | (h) | (h) | |||

| Compton et al. 49 | Healthy female and male opioid‐dependent user | 16 (NP) | 18–65 | 16/0 | 6.88a | 54.7 | NA | NA |

| 15 (NP) | 24/0 | 9.1a | 81.1 | NA | NA | |||

| 10 (NP) | 32/0 | 13.93a | 103.0 | NA | 0.94 | |||

| Greenwald et al. 50 | Healthy female and male opioid‐dependent users | 5 (3/2) | 34–45 | 2/0 | 0.85a | 6.5 | NA | 0.9 |

| 16/0 | 6.3 | 48.6 | NA | 1.2 | ||||

| 32/0 | 13.2 | 96.0 | NA | 1.2 |

AUC0–24, area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0 to 24 h after a dose; Cmax, maximum plasma concentration; CLtotal, total clearance; NA, not available; NP, not provided; t1/2, half‐life

Values calculated from graph digitized data

As the virtual patient population was used for all PBPK simulations, and published clinical PK data were used to build and validate our PBPK models, this work was not submitted for approval to an ethics committee.

SL BUP steady‐state exposure simulations

As SimCyp® is unable to perform virtual multiple dosing and drug–drug interaction simulations for custom‐defined models, we used it to predict single‐dose SL BUP concentration–time profiles for 100 virtual subjects; following this, Phoenix® WinNonlin® was used to characterize single‐dose PK parameters and simulate SL BUP steady‐state PK. A two‐compartment, first‐order absorption, with a lag‐time PK model (Model 12) within the WNL5 classic modelling module was used to predict the concentration–time profile after a single dose. The Gauss ‐Newton (Levenberg and Hartley) technique is the term that is used by the software, WinNonlin. This means to use the Gauss‐Newton minimization method with the Levenbeg and Harley modification. For the multiple dose simulation, the generated micro‐rate constants were used as the user supplied initial parameter values that derived from single dose analysis through the same PK model.

Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 52, and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16 53, 54.

Results

BUP exposure prediction following a single IV BUP dose in healthy subjects

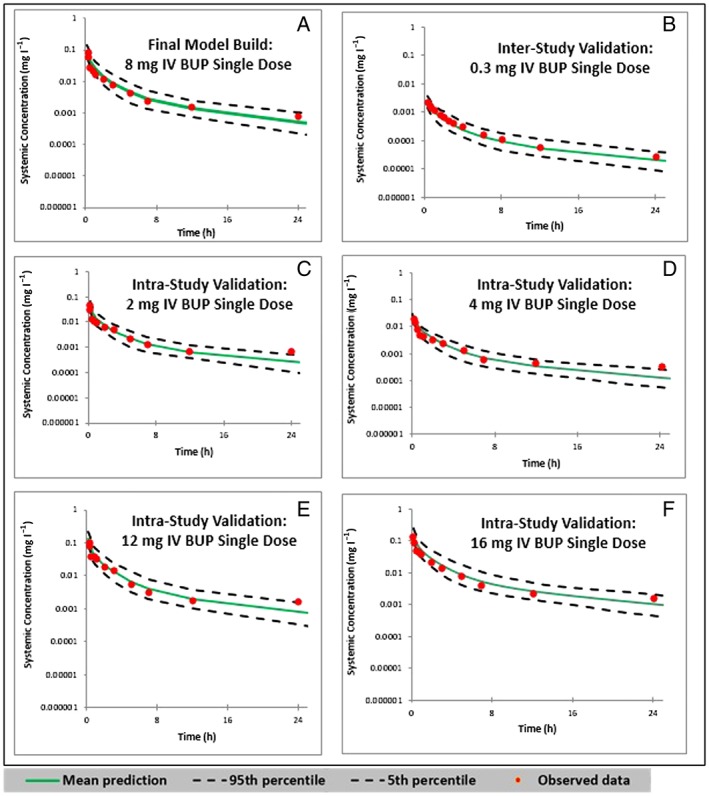

The predicted concentration–time profile of the final BUP PBPK model following an 8 mg IV BUP dose was within the range of the observed data published by Huestis et al. 42. The predicted means of the concentration–time profiles and 90% PI overlaid with the observed data for the first 24 h of the 72‐h dataset are shown in Figure 2. As shown in Figure 2A, the observed data were within the 90% PI of the variability observed around the predicted mean exposure. The predicted and observed mean concentration–time profiles were visually similar. This was true for the inter‐ and intrastudy validation plots, as shown in Figures 2B–F. The accuracies of the predicted means of AUC0–∞ and CLtotal were within 85–115% of the observed means (Table 10). These limits held true for all doses (2, 4, 12 and 16 mg) tested for intrastudy validation.

Figure 2.

Predicted and observed concentration–time profiles following a single intravenous (IV) push doses of buprenorphine (BUP). (A) Plot of the final model built with a single dose of 8 mg IV BUP, in comparison with the observed data from Huestis et al. 43. (B) Interstudy validation plot with a single dose of 0.3 mg IV BUP, as observed by Bai et al. 43. (C, D, E and F) Intrastudy validation plots with single doses of 2, 4, 12 and 16 mg IV BUP, respectively, as observed by Huestis et al. 42 0–24 h pharmacokinetic simulations are shown here

Table 10.

Goodness of fit for intravenous buprenorphine model in healthy subjects

| Process | Data source | Dose (mg) | AUC0–∞ | CLtotal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Predicted (90% CI) | Diff. | Observed | Predicted (90% CI) | Diff. | |||

| (mg•h l–1) | (mg•h l–1) | (%) | (l h–1) | (l h–1) | (%) | |||

| Final model | Huestis et al. 42 | 8 | 0.153 | 0.151 (0.0821–0.2688) | 1.3 | 52.4 | 53.1 (29.8–97.4) | 1.3 |

| Intrastudy validation | 2 | 0.0414 | 0.0379 (0.0209–0.0665) | −8.5 | 49.8 | 52.8 (30.1–95.7) | 6.0 | |

| 4 | 0.0759 | 0.0756 (0.0419–0.1314) | 0.4 | 53.2 | 52.9 (30.4–95.5) | 0.6 | ||

| 12 | 0.245 | 0.226 (0.123–0.402) | 7.7 | 54.7 | 53.1 (29.8–97.6) | 2.9 | ||

| 16 | 0.2691 | 0.2886 (0.1561–0.5125) | 7.2 | 60.0 | 55.4 (31.2–102.5) | −7.6 | ||

| Interstudy validation | Bai et al. 43 | 0.3 | 0.0052 | 0.0049 (0.0025–0.0087) | 9.1 | 57.7a | 61.2 (34.5–120) | 13 |

| Harris et al. 44 | 4 | 0.0704b | 0.0727 (0.0534–0.0958) | 3.3 | NP | NP | NP | |

| Mendelson et al. 45 | 1 | 0.0184 | 0.0181 (0.00993–0.0313) | −1.6 | 62.5 | 55.2 (31.9–100.7) | −11.7 | |

AUC0–∞, area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0 to infinity after a dose; CI, confidence interval; CLtotal, total body clearance; Diff., difference; NP, not provided

Bai et al. 43 did not report CL, so the observed CL was calculated by using dose/the reported AUC0–∞

Harris et al. 44 only reported AUC0–24, and CL was not available. Difference (%) = [(predicted – observed mean value)/observed mean value]*100

The model was further validated by two model‐naïve clinical PK datasets (Bai et al. 43, Harris et al. 44, and Mendelson et al. 45) for interstudy validations, and the comparisons are listed in Table 10. The accuracies of the predicted means of AUC and CL were within 85–115% of the observed means. These limits held true for all doses (0.3, 1, 4 mg) tested for interstudy validation.

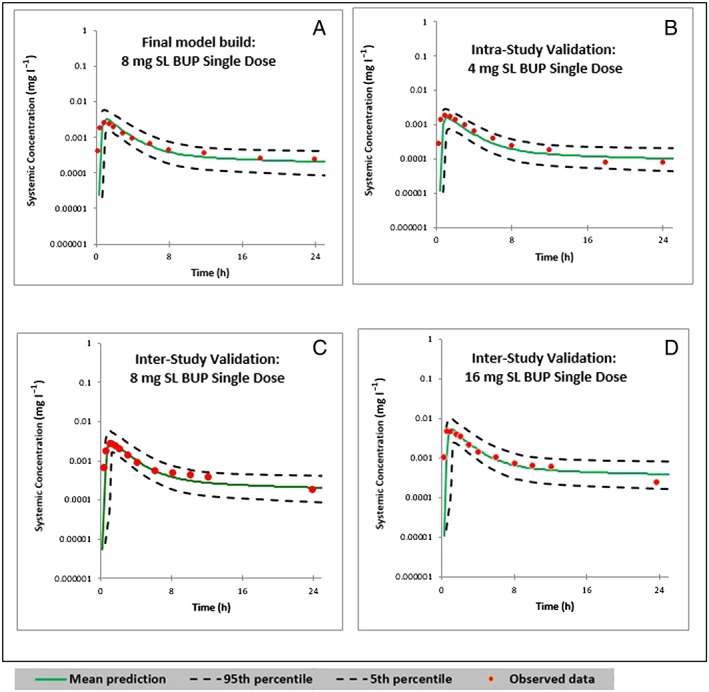

Modelling prediction following a SL of BUP in healthy volunteers

The predicted means of concentration–time profiles and 90% PI overlaid with the observed data are showed in Figure 3. As shown in Figure 3A, the observed data were within the 90% PI of the variability observed around the predicted mean exposure. Moreover, the predicted and observed mean concentration–time profiles were visually similar. This was true for the inter‐ and intrastudy validation plots, as shown in Figures 3B–D. The accuracies of the predicted means of AUC were within 75–125% of the observed means for all inter‐ and intrastudy validations, with the exception of a 24 mg single‐dose study, in which the accuracy was +137%. The accuracies of the predicted means of Cmax were within 80–125% for all the studies (Table 11).

Figure 3.

Predicted and observed concentration–time profiles following single sublingual (SL) doses of buprenorphine (BUP) in 100 virtual healthy subjects. (A) Plot of the final model built with an 8 mg SL single dose of BUP, in comparison with the observed data from Ciraulo et al. 46. (B) Intrastudy validation plot with a single dose of 4 mg SL BUP, as observed by Ciraulo et al. 46. (C and D) Interstudy validation plots with a single dose of 8 mg and 16 mg SL BUP, respectively, as observed by Harris et al. 47. The 0–24 h period in 48 h and 72 h simulations are shown here

Table 11.

Goodness of fit for sublingual buprenorphine model in healthy subjects

| Process | Data source | Dose (mg) | AUC0–∞ | CLtotal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Predicted (90% CI) | Diff. | Observed | Predicted (90% CI) | Diff. | |||

| (mg•h l–1) | (mg•h l–1) | (%) | (l h–1) | (l h–1) | (%) | |||

| Final model | Ciraulo et al. 46 | 8 | 0.0199 | 0.0221 (0.0100–0.0423) | 11.0 | 0.00265 | 0.00329 (0.0016–0.0057) | 24.2 |

| Intrastudy validation | 4 | 0.0094 | 0.0110 (0.0050–0.0211) | 18.1 | 0.002 | 0.00164 (0.0008–0.02518) | 18 | |

| 16 | 0.0349 | 0.0395 (0.0175–0.0764) | 13.2 | 0.00442 | 0.00547 (0.0025–0.0095) | 23.8 | ||

| 24 | 0.04881 | 0.0606 (0.0258–0.114) | 24.1 | 0.00541 | 0.00738 (0.00372–0.0139) | 36.4 | ||

| Interstudy validation | Harris et al. 47 | 4 | 0.01252 | 0.00938 (0.00408–0.0174) | −25.1 | 0.00184 | 0.00155 (0.0008–0.0029) | −15.8 |

| 8 | 0.0202 | 0.0184 (0.0825–0.0355) | 8.9 | 0.003 | 0.00326 (0.00162–0.00596) | 8.7 | ||

| 16 | 0.03489 | 0.0317 (0.014–0.0631) | 9.1 | 0.00595 | 0.00547 (0.00246–0.0100) | 8.1 | ||

| McAleer et al. 48 | 8 | 0.02689 | 0.0227 (0.00967–0.0423) | −15.6 | 0.004 | 0.0031 (0.0016–0.0059) | 22.5 | |

| 12 | 0.03652 | 0.034 (0.0145–0.0635) | −6.9 | 0.0054 | 0.00466 (0.00241–0.0806) | −13.7 | ||

| 16 | 0.04619 | 0.0404 (0.0171–0.0760) | −12.5 | 0.0064 | 0.0049 (0.0025–0.0092) | −23.4 | ||

AUC0–∞, area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0 to infinity after a dose; Cmax, maximum plasma concentration; CI, confidence interval; Diff., difference

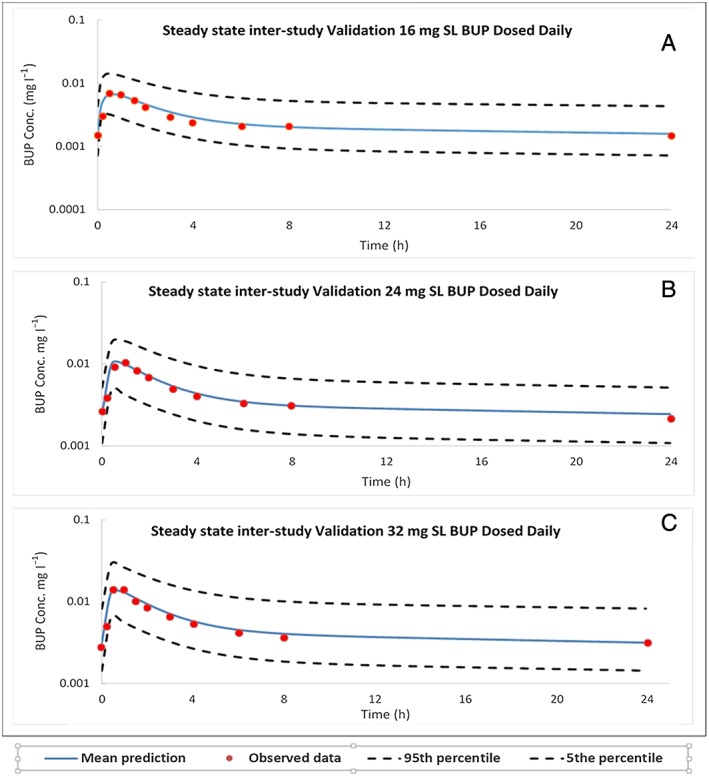

The model was further validated by two model‐naïve clinical PK datasets published by Harris et al. 47 and McAleer et al. 48 (Table 11) as a measure of interstudy validation. The accuracies of the predicted means of AUC were within 85–115% of the observed means, and the accuracy of the predicted means of Cmax were within 80–125% of the observed means. Doses of 16, 24 and 32 mg SL BUP at steady state were also validated against studies published by Compton et al. 49 (Figure 4) and Greenwald et al. 50. The accuracies of AUC and Cmax are tabulated in Table 12. The accuracy limits for these comparisons were between 85% and 115%.

Figure 4.

Steady‐state predicted and observed concentration–time profiles following daily sublingual (SL) doses of buprenorphine (BUP) in healthy subjects. (A, B, and C) Interstudy validation plots with 16 mg, 24 mg and 32 mg SL BUP, respectively, as observed by Compton et al. 49

Table 12.

Goodness of fit for sublingual buprenorphine models in healthy volunteers at steady state

| Process | Data source | Dose (mg) | AUCss, 0–24 | Cmax,ss | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Predicted (90% CI) | Diff. | Observed | Predicted (90% CI) | Diff. | |||

| (mg•h l–1) | (mg•h l–1) | (%) | (mg l–1) | (mg l–1) | (%) | |||

| Interstudy validation | Compton et al. 49 | 16 | 0.05472 | 0.05508 (0.00255–0.139) | 0.7 | 0.0068 | 0.0065 (0.0032–0.0142) | 4.4 |

| 24 | 0.08112 | 0.08252 (0.0379–0.1767) | 1.7 | 0.0091 | 0.0099 (0.0487–0.0191) | 8.8 | ||

| 32 | 0.10301 | 0.1099 (0.0504–0.2670) | 6.7 | 0.0139 | 0.0133 (0.0065–0.0288) | 4.3 | ||

| Greenwald et al. 50 | 16 | 0.0486 | 0.05508 (0.00255–0.139) | 13.3 | 0.0063 | 0.0065 (0.0032–0.0142) | 3.2 | |

| 32 | 0.096 | 0.1099 (0.0504–0.2670) | 14.5 | 0.0132 | 0.0133 (0.0065–0.0288) | 0.8 | ||

AUCss, 0–24, area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0 to infinity after a dose at steady state; Cmax,ss, maximum plasma concentration at steady state; CI, confidence interval; Diff., difference

Difference (%) = [(predicted – observed mean value)/observed mean value]*100

We were able to predict the brain concentrations of BUP using the model developed. BUP brain exposure was predicted to be about four times higher than that of the plasma (brain AUC0–72 h: 0.195 mg•h l–1; plasma AUC0–72 h: 0.0536 mg•h l–1). We were able to use the mu‐opioid receptor availability data from Greenwald et al. 55 to illustrate the relationship between the brain/plasma concentration of BUP and mu‐opioid receptor occupancy (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Predicted plasma and brain concentration–time profiles following a 16 mg sublingual (SL) dose of buprenorphine (BUP) in healthy subjects; mu‐opioid receptor availability is simulated on the secondary axis. Conc., concentration

Discussion

In the present study, we built and validated full PBPK models of IV and SL BUP in healthy opioid‐dependent and non‐opioid‐dependent patient populations across a wide range of BUP doses. The full PBPK models incorporate enzymatic metabolism of BUP, its disposition into 13 major tissues in the body and three modes of absorption following the SL dosage forms. The models are robust in representing the multicompartment first‐order disposition of BUP. The predicted concentration–time profiles in the study‐matched virtual patient population were consistent with observed data across 14 independent studies (five IV single dose, five SL single dose and four SL multiple dose) among healthy opioid‐dependent and non‐opioid‐dependent patient populations. The predicted IV BUP PK parameters fell within the 85–115% range of the corresponding PK parameters calculated from the IV BUP observed studies. The predicted SL BUP PK parameters fell within the 75–137% range of the corresponding PK parameters calculated from single‐dose SL BUP observed studies. This range was 100–115% when comparing steady‐state SL BUP PK parameters. Both models were robust in predicting BUP exposure after IV and SL administration in a healthy population in the dose range 4–32 mg.

BUP is a lipophilic drug with a large volume of distribution (200–400 l) 56. The semi‐log concentration–time profile after IV administration shows a rapid drop in systemic concentration followed by a slower terminal phase, indicating that BUP is a multicompartment drug with three distinct phases of disposition. It undergoes metabolism by various hepatic and gut CYP450 and UGT enzymes, making it susceptible to extensive first‐pass metabolism 27, 38, 57. A mass balance study following radiolabelled IV BUP administration reported 30% of the dose recovered in the urine, and 69% in the faeces. The breakdown of BUP free drug, parent drug and its metabolites, with sources of metabolism, from this mass balance study is shown in Table 13 58. The relative contribution of CYP450 enzymes (71.8%) appears to be much higher than that of UGT enzymes (28.2%) when comparing the known major metabolites of BUP (N‐BUP, BUP‐Glu and N‐BUP‐Glu). We would speculate that the relative contribution of CYP450 enzymes following SL administration would be much higher than 71.8% as there is a higher abundance of CYP3A4 and CYP2C8 enzymes in the gut compared with UGT1A1, 1A3, and 2B7 enzymes. In the proposed SL BUP PBPK model, the modelled relative contributions of CYP450 and UGT enzymes are 95.46% and 4.54%, respectively. These relative contributions were estimated from recombinant CYP and UGT activities reported in the referenced in vitro study and ISEF‐based extrapolations 29, 30, 31. Currently, we cannot validate the exact relative contribution of these enzymes as there is no published SL BUP mass balance study, and we acknowledge this as a limitation of the PBPK models. The lack of a SL BUP mass balance study and the overestimation of the contribution of CYP450 enzymes is a limitation of the proposed model. Currently, SimCyp® does not allow us to perform multiple dose/steady‐state simulations for Customized models that involve multiple routes of absorption (SL BUP model). We could not perform steady‐state simulations of SL BUP for the purposes of checking the effect of drug–drug interactions with known CYP3A4 inhibitors, such as ketoconazole, to verify the magnitude of CYP3A4 involvement.

Table 13.

Results from mass balance study following administration of radiolabelled intravenous buprenorphine (BUP) 58

| Drug/metabolite | Enzyme | Urine (%) | Faeces (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free BUP | – | 1.0 | 33 |

| BUP‐Glu | UGTs | 9.4 | 5 |

| N‐BUP | CYP450s | 2.7 | 21 |

| N‐BUP‐Glu | CYP450s > UGTs | 11 | 2 |

| Other | CYP450s or UGTs | 5.9 | 8 |

| Total | 30.0 | 69.0 | |

| Relative contribution of CYP450 and UGT enzymes (%) | |||

| When considering N‐BUP, BUP‐Glu and N‐BUP‐Glu | CYP450s | 71.82 | |

| UGTs | 28.18 | ||

BUP‐Glu, buprenorphine glucuronide; CYP, cytochrome; N‐BUP, norbuprenorphine; N‐BUP‐Glu, norbuprenorphine glucuronide; UGT, UDP‐glucuronosyltransferase

Based on various in vitro transporter studies, there is no conclusive evidence for the involvement of ATP binding cassette and solute carrier drug transporters in BUP disposition 59. Due to its poor oral bioavailability (F = 10–15%) 51, 60, the SL route of administration is the preferred route and is currently approved by the FDA. The half‐life of BUP after SL administration is longer than with IV administration, suggesting a slow release of the drug from a depot to the systemic circulation after SL administration, in addition to the rapid initial absorption 56.

Physiologically, drug absorption following SL administration involves a combination of rapid passive absorption across the SL mucosal membrane, a slow depot release from the buccal tissue depot space, as well as gut absorption from the portion of the formulation that is swallowed. To mimic the three distinct phases, our SL PBPK model incorporates SL, oral and buccal depot release of the drug. Based on the drug absorption and disposition profiles reported in studies considered for building the model, we divided the dose into the following routes: 62.5% nondepot, which comprises 7–10% SL passive absorption into the circulation and 90–93% absorption in the gastrointestinal tract; the remaining 37.5% of the dose was attributed to the depot release from the buccal tissue. The percentage distribution of the dose among these routes was optimized and validated with model‐naïve clinical PK datasets of SL BUP. Due to the multicompartment disposition profile of BUP, the half‐life reported for BUP in the literature after SL BUP administration is likely to differ, based on the length of the PK study period; prospective single‐dose PK studies of 12 h, 48 h and 72 h in duration would yield sequentially increasing calculated half‐lives for BUP after SL administration 42, 43, 44.

BUP exposure (Cmax and AUC) increases in a linear dose‐proportional manner after IV administration. The BUP exposure vs. dose relationship after SL administration is linear only between the dose range 4–12 mg; beyond 16 mg, the exposure increase is not dose proportional (Subutex® Drug Monograph); this is consistent with published data 47. This behaviour does not suggest the saturation of hepatic metabolism or gut metabolism. We believe that this nonlinearity is due to differences in the absorption profile, and that the adjustment of the percentage dose contribution to the oral component for doses beyond 16 mg (Table 6) corrected for this.

BUP PK profiles after SL administration exhibited a large interstudy variability, especially for the Cmax and time to maximum concentration (Tmax), in single‐dose administration studies. The large interstudy variability is probably due to variability in the SL administration technique – i.e. there could be a difference in the proportion of the formulation that is swallowed vs. absorbed after SL administration; some patients may not follow directions and may chew the formulation; some patients may retain the SL formulation for varying residence times in the mouth; and some may take whole tablets, while others may cut or crush the product before use.

In order to treat opioid substance dependence, BUP has to cross the brain–blood barrier and bind to mu‐opioid receptors. However, currently there are no studies reporting BUP concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid. Greenwald et al. 55 studied the mu‐opioid receptor occupancy in the brains of heroin‐dependent patients and reported a logarithmic relationship between BUP plasma concentrations and mu‐opioid receptor binding potential or availability in the brain (Bmax/Kd). They also found that a plasma concentration of at least 1 ng ml–1 is needed for 50% mu‐opioid receptor occupancy, suppressing drug withdrawal symptoms and showing efficacy 55.

We were able to illustrate the applicability of the developed model and brain concentration–time profiles to the mu‐opioid receptor occupancy data published by Greenwald et al. 55. Given the lipophilic properties of BUP, its brain exposure was about four times higher than that of the plasma (brain AUC0–72 h: 0.195 mg•h l–1; plasma AUC0–72 h: 0.0536 mg•h l–1). The mean plasma BUP concentration in healthy subjects falls below the 1 ng ml–1 threshold about 9 h following a 16 mg dose, suggesting a loss of efficacy beyond this time range (Figure 5).

Although BUP metabolites such as BUP‐3‐glucuronide, nor‐BUP and nor‐BUP‐3‐glucuronide may be biologically active, their concentrations in the brain are very low 61, 62 and their contribution towards the antinociceptive effect is limited. For these reasons, we did not incorporate the metabolite profiles of BUP in the present study.

Using the PBPK model developed, we will be able to predict the plasma and brain concentrations of BUP in patients of varying age, gender and body weight, to optimize BUP pharmacotherapy individually. These PBPK models could also be potentially extrapolated to special patient populations such as pregnant women, paediatric patients, patients with compromised liver function and others. We have not presented any data on the predictability of the impact of covariates here but plan to publish these in future manuscripts.

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

We would like to acknowledge Certara for providing us with Simcyp® academic licences and the necessary training. This work is partially funded by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD, HD047905) through the Obstetric Pharmacology Research Center (OPRC).

Kalluri, H. V. , Zhang, H. , Caritis, S. N. , and Venkataramanan, R. (2017) A physiologically based pharmacokinetic modelling approach to predict buprenorphine pharmacokinetics following intravenous and sublingual administration. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 83: 2458–2473. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13368.

References

- 1. Warner M, Chen LH, Makuc DM, Anderson RN, Miniño AM. Drug poisoning deaths in the United States, 1980–2008. NCHS Data Brief 2011; 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Control CfD, Prevention . Wide‐ranging online data for epidemiologic research (WONDER). CDC. National Center for Health Statistics: Atlanta, GA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Calcaterra S, Glanz J, Binswanger IA. National trends in pharmaceutical opioid related overdose deaths compared to other substance related overdose deaths: 1999–2009. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013; 131: 263–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Control CfD, Prevention . CDC grand rounds: prescription drug overdoses – a US epidemic. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012; 61: 10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Akil H, Watson SJ, Young E, Lewis ME, Khachaturian H, Walker JM. Endogenous opioids: biology and function. Annu Rev Neurosci 1984; 7: 223–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, Ely EW, Gélinas C, Dasta JF, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit: executive summary. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2013; 70: 53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ballantyne JC, LaForge SK. Opioid dependence and addiction during opioid treatment of chronic pain. Pain 2007; 129: 235–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, Adler JA, Ballantyne JC, Davies P, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain 2009; 10: 113 30. e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Degenhardt L, Hall W. Extent of illicit drug use and dependence, and their contribution to the global burden of disease. Lancet 2012; 379: 55–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hulse G, English D, Milne E, Holman C. The quantification of mortality resulting from the regular use of illicit opiates. Addiction 1999; 94: 221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication‐assisted therapies – tackling the opioid‐overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 2063–2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fullerton CA, Kim M, Thomas CP, Lyman DR, Montejano LB, Dougherty RH, et al. Medication‐assisted treatment with methadone: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv 2014; 65: 146–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marsch LA. The efficacy of methadone maintenance interventions in reducing illicit opiate use, HIV risk behavior and criminality: a meta‐analysis. Addiction 1998; 93: 515–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barnett PG, Rodgers JH, Bloch DA. A meta‐analysis comparing buprenorphine to methadone for treatment of opiate dependence. Addiction 2001; 96: 683–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Johansson BA, Berglund M, Lindgren A. Efficacy of maintenance treatment with naltrexone for opioid dependence: a meta‐analytical review. Addiction 2006; 101: 491–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Walsh SL, Preston KL, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. Acute administration of buprenorphine in humans: partial agonist and blockade effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1995; 274: 361–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martin W. History and development of mixed opioid agonists, partial agonists and antagonists. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1979; 7: 273S–279S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Downing JW, Leary WP, White ES. Buprenorphine: a new potent long‐acting synthetic analgesic. Comparison with morphine. Br J Anaesth 1977; 49: 251–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Walsh SL, Preston KL, Stitzer ML, Cone EJ, Bigelow GE. Clinical pharmacology of buprenorphine: ceiling effects at high doses. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1994; 55: 569–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fudala PJ, Bridge TP, Herbert S, Williford WO, Chiang CN, Jones K, et al. Office‐based treatment of opiate addiction with a sublingual‐tablet formulation of buprenorphine and naloxone. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 949–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Teruya C, Schwartz RP, Mitchell SG, Hasson AL, Thomas C, Buoncristiani SH, et al. Patient perspectives on buprenorphine/naloxone: a qualitative study of retention during the starting treatment with agonist replacement therapies (START) study. J Psychoactive Drugs 2014; 46: 412–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wesson DR, Ling W. The clinical opiate withdrawal scale (COWS). J Psychoactive Drugs 2003; 35: 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. De Boer A, De Leede L, Breimer D. Drug absorption by sublingual and rectal routes. Br J Anaesth 1984; 56: 69–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhao P, Zhang L, Grillo JA, Liu Q, Bullock JM, Moon YJ, et al. Applications of physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling and simulation during regulatory review. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011; 89: 259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fedorov S. GetData graph digitizer. Available at http://www getdata‐graph‐digitizer.com (last accessed November 2016).

- 26. Avdeef A, Barrett DA, Shaw PN, Knaggs RD, Davis SS. Octanol‐, chloroform‐, and propylene glycol dipelargonat‐water partitioning of morphine‐6‐glucuronide and other related opiates. J Med Chem 1996; 39: 4377–4381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mistry M, Houston JB. Glucuronidation in vitro and in vivo. Comparison of intestinal and hepatic conjugation of morphine, naloxone, and buprenorphine. Drug Metab Dispos 1987; 15: 710–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Walter DSIC. Absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of buprenorphine in animals and humans. New York: Wiley‐Liss, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Picard N, Cresteil T, Djebli N, Marquet P. In vitro metabolism study of buprenorphine: evidence for new metabolic pathways. Drug Metab Dispos 2005; 33: 689–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cubitt HE, Houston JB, Galetin A. Relative importance of intestinal and hepatic glucuronidation‐impact on the prediction of drug clearance. Pharm Res 2009; 26: 1073–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oechsler S, Skopp G. An in vitro approach to estimate putative inhibition of buprenorphine and norbuprenorphine glucuronidation. Int J Leg Med 2010; 124: 187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Narang N, Sharma J. Sublingual mucosa as a route for systemic drug delivery. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci 2011; 3: 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bullingham RE, McQuay HJ, Moore A, Bennett MR. Buprenorphine kinetics. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1980; 28: 667–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sawada Y, Hanano M, Sugiyama Y, Harashima H, Iga T. Prediction of the volumes of distribution of basic drugs in humans based on data from animals. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm 1984; 12: 587–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Berezhkovskiy LM. Volume of distribution at steady state for a linear pharmacokinetic system with peripheral elimination. J Pharm Sci 2004; 93: 1628–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Poulin P, Schoenlein K, Theil FP. Prediction of adipose tissue: plasma partition coefficients for structurally unrelated drugs. J Pharm Sci 2001; 90: 436–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Poulin P, Theil FP. A priori prediction of tissue:plasma partition coefficients of drugs to facilitate the use of physiologically‐based pharmacokinetic models in drug discovery. J Pharm Sci 2000; 89: 16–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cone EJ, Gorodetzky CW, Yousefnejad D, Buchwald WF, Johnson RE. The metabolism and excretion of buprenorphine in humans. Drug Metab Dispos 1984; 12: 577–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chang Y, Moody DE. Glucuronidation of buprenorphine and norbuprenorphine by human liver microsomes and UDP‐glucuronosyltransferases. Drug Metab Lett 2009; 3: 101–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chang Y, Moody DE, McCance‐Katz EF. Novel metabolites of buprenorphine detected in human liver microsomes and human urine. Drug Metab Dispos 2006; 34: 440–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Proctor NJ, Tucker GT, Rostami‐Hodjegan A. Predicting drug clearance from recombinantly expressed CYPs: intersystem extrapolation factors. Xenobiotica 2004; 34: 151–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Huestis MA, Cone EJ, Pirnay SO, Umbricht A, Preston KL. Intravenous buprenorphine and norbuprenorphine pharmacokinetics in humans. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013; 131: 258–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bai SA, Xiang Q, Finn A. Evaluation of the pharmacokinetics of single‐ and multiple‐dose buprenorphine buccal film in healthy volunteers. Clin Ther 2016; 38: 358–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Harris DS, Jones RT, Welm S, Upton RA, Lin E, Mendelson J. Buprenorphine and naloxone co‐administration in opiate‐dependent patients stabilized on sublingual buprenorphine. Drug Alcohol Depend 2000; 61: 85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mendelson J, Upton RA, Everhart ET, Jacob P 3rd, Jones RT. Bioavailability of sublingual buprenorphine. J Clin Pharmacol 1997; 37: 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ciraulo DA, Hitzemann RJ, Somoza E, Knapp CM, Rotrosen J, Sarid‐Segal O, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of multiple sublingual buprenorphine tablets in dose‐escalation trials. J Clin Pharmacol 2006; 46: 179–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Harris DS, Mendelson JE, Lin ET, Upton RA, Jones RT. Pharmacokinetics and subjective effects of sublingual buprenorphine, alone or in combination with naloxone: lack of dose proportionality. Clin Pharmacokinet 2004; 43: 329–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. McAleer SD, Mills RJ, Polack T, Hussain T, Rolan PE, Gibbs AD, et al. Pharmacokinetics of high‐dose buprenorphine following single administration of sublingual tablet formulations in opioid naive healthy male volunteers under a naltrexone block. Drug Alcohol Depend 2003; 72: 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Compton P, Ling W, Moody D, Chiang N. Pharmacokinetics, bioavailability and opioid effects of liquid versus tablet buprenorphine. Drug Alcohol Depend 2006; 82: 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Greenwald MK, Johanson CE, Moody DE, Woods JH, Kilbourn MR, Koeppe RA, et al. Effects of buprenorphine maintenance dose on mu‐opioid receptor availability, plasma concentrations, and antagonist blockade in heroin‐dependent volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003; 28: 2000–2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Abbo LA, Ko DJC, Maxwell LK, Galinsky RE. Pharmacokinetics of buprenorphine following intravenous and oral transmucosal administration in dogs. Vet Ther 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Southan C, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Alexander SPH, et al. The IUPHAR/BPS guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2016: towards curated quantitative interactions between 1300 protein targets and 6000 ligands. Nucleic Acids Res 2016; 44: D1054–D1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Alexander SPH, Davenport AP, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: G protein‐coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol 2015; 172: 5744–5869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Alexander SPH, Fabbro D, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol 2015; 172: 6024–6109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Greenwald M, Johanson CE, Bueller J, Chang Y, Moody DE, Kilbourn M, et al. Buprenorphine duration of action: mu‐opioid receptor availability and pharmacokinetic and behavioral indices. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 61: 101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kuhlman JJ Jr, Lalani S, Magluilo J Jr, Levine B, Darwin WD. Human pharmacokinetics of intravenous, sublingual, and buccal buprenorphine. J Anal Toxicol 1996; 20: 369–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lewis JW, Walter D. Buprenorphine‐background to its development as a treatment for opiate dependence. NIDA Res Monogr 1992; 121: 5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Everhart ET, Cheung P, Mendelson J, Upton R, Jones RT. The mass balance of buprenorphine in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1999; 65: 152. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hassan HE, Myers AL, Coop A, Eddington ND. Differential involvement of P‐glycoprotein (ABCB1) in permeability, tissue distribution, and antinociceptive activity of methadone, buprenorphine, and diprenorphine: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. J Pharm Sci 2009; 98: 4928–4940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Welsh C, Valadez‐Meltzer A. Buprenorphine: a (relatively) new treatment for opioid dependence. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2005; 2: 29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Brown SM, Holtzman M, Kim T, Kharasch ED. Buprenorphine metabolites, buprenorphine‐3‐glucuronide and norbuprenorphine‐3‐glucuronide, are biologically active. Anesthesiology 2011; 115: 1251–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Brown SM, Campbell SD, Crafford A, Regina KJ, Holtzman MJ, Kharasch ED. P‐glycoprotein is a major determinant of norbuprenorphine brain exposure and antinociception. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2012; 343: 53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]