Abstract

Introduction

Aducanumab (BIIB037), a human monoclonal antibody selective for aggregated forms of amyloid beta, is being investigated as a disease-modifying treatment for Alzheimer's disease (AD).

Methods

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled single ascending-dose study investigated the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics (PK) of aducanumab in patients with mild-to-moderate AD. Eligible patients were sequentially randomized 6:2 to aducanumab (0.3, 1, 3, 10, 20, 30, and 60 mg/kg) or placebo.

Results

The primary outcome was safety and tolerability. Doses ≤30 mg/kg were generally well tolerated with no severe or serious adverse events (SAEs). All three patients who received 60 mg/kg aducanumab developed SAEs of symptomatic amyloid-related imaging abnormalities, which completely resolved by weeks 8–15. Aducanumab Cmax, AUC0–last, and AUCinf increased in a dose-proportional manner.

Discussion

In this single-dose study, aducanumab demonstrated an acceptable safety and tolerability profile and linear PK at doses ≤30 mg/kg (clinicaltrials.govNCT01397539).

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Monoclonal antibody, Clinical trial, Pharmacokinetics, Adverse events

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is characterized by progressive memory loss and decline in cognitive function and accounts for 50%–75% of dementia cases [1]. Pathologically, AD is defined by the presence in the brain of extracellular neuritic plaques containing aggregated amyloid beta (Aβ) peptide and intraneuronal neurofibrillary tangles containing phosphorylated tau proteins.

The “amyloid cascade hypothesis” proposes that the accumulation of Aβ, resulting from an imbalance between Aβ production and clearance in the brain, is the main driver of AD pathogenesis [2], [3]. Aβ, a peptide generated by sequential enzymatic cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (APP), exists in several isoforms, including Aβ40 and Aβ42. These monomeric peptides have a tendency to aggregate into higher molecular weight oligomers, which may transit into insoluble fibrils that deposit in the brain as amyloid plaques [4]. The deposition of Aβ plaques occurs long before any clinical symptoms and as many as 20 years before the onset of dementia [5], [6]. Evidence suggests that both soluble oligomers and amyloid plaques are neurotoxic [7], [8], [9], [10], and clearance of amyloid plaques can lead to normalization of calcium homeostasis, neuronal activity, and reduction of oxidative stress in the brain of an animal model of AD [11], [12], [13], [14].

Currently approved therapies for AD provide only modest symptomatic benefit and do not attenuate the course of the disease (are not disease modifying). The screening of libraries of human memory B cells for reactivity against aggregated Aβ led to the molecular cloning, sequencing, and recombinant expression of aducanumab (BIIB037), a human anti-Aβ monoclonal antibody that selectively targets aggregated forms of Aβ, including soluble oligomers and insoluble fibrils. Preclinical studies in Tg2576 mice showed brain penetration and target engagement of aducanumab, leading to a reduction of brain amyloid burden [15]. Aducanumab is currently being investigated as a disease-modifying treatment for AD.

The objectives of the present study (clinicaltrials.gov NCT01397539) were to investigate the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics (PK) of aducanumab after single ascending-dose administration in patients with mild-to-moderate AD. This was the first study of aducanumab in humans.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This was a single-dose-escalation, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 1 multicenter study (clinicaltrials.gov NCT01397539). Eligibility criteria included: age 55 to 85 years; and a clinical diagnosis consistent with (1) probable AD according to National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disease and Stroke and Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association criteria [16] and (2) dementia of Alzheimer's type according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–Text Revision criteria [17]; and a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of 14–26.

Patients were scheduled to be enrolled into seven sequential cohorts of eight patients each randomized 6:2 to receive aducanumab (0.3, 1, 3, 10, 20, 30, and 60 mg/kg) or matching placebo. For the last cohort, a ratio of APOE ε4 carriers to noncarriers of at least 1:1 was planned but was not achieved due to early termination of that cohort after five patients had been enrolled (three for 60 mg/kg and two for placebo). Patients received a single dose, administered by intravenous (IV) infusion after dilution into saline, on day 1 at the study clinic. Randomization was performed by a centralized Interactive Voice and Web Response System. A dose of 0.3 mg/kg was predicted to provide a mean aducanumab exposure (area under the serum concentration—time profile from time 0 extrapolated to infinite time [AUCinf]) in humans of up to approximately 1000 μg•h/mL. This predicted human exposure calculation assumed human clearance of approximately 7 mL/day/kg (based on allometric scaling and considering human clearance values reported for similar compounds). A dose of 60 mg/kg was predicted to provide a mean exposure that would not exceed the mean exposure in Tg2576 mice given 500 mg/kg (402,000 μg•h/mL). Tg2576 mice are a commercially available animal model of AD that, with aging, accumulate amyloid in the central nervous system and are considered the most relevant pharmacologic species to evaluate the toxicity profile of aducanumab. Before escalation to the next dose level, the Data Safety Review Committee reviewed unblinded safety data for all patients in the current cohort through 21 days after dosing and before escalation to the highest dose for all patients from all previous cohorts through 11 weeks after dosing. Patients were followed-up for 24 weeks after dosing.

The primary objective of this study was to assess the safety and tolerability of a range of aducanumab doses administered as single IV infusions in patients with AD. Secondary objectives were to assess the PK and to evaluate the immunogenicity of aducanumab after single-dose administration. Exploratory objectives were to assess the effects of aducanumab on potential plasma biomarkers and on cognition.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation and Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and ethics committee approval was obtained at each participating site. All patients provided written informed consent.

2.2. Study assessments

Vital signs, physical and neurologic examinations, clinical chemistry and hematology, and urinalysis were assessed during inpatient observation and at eight follow-up visits on days 3 and 4 and weeks 1, 2, 3, 6, 11, and 24 after dosing. Electrocardiograms (12-lead paper ECGs) were performed during inpatient observation and at weeks 1 and 24 after dosing. Continuous cardiac monitoring using Holter monitoring was performed during the study treatment infusion and for 12 hours after the end of the infusion. ECGs were read by the investigator and reported as normal, abnormal-no adverse event (AE), or abnormal-AE. All AEs and serious AEs (SAEs) were monitored and recorded continuously throughout the study.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans (including T1, T2, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, and gradient echo) taken at screening and at weeks 3, 11, and 24 were evaluated by each site's local radiologist and by a central reader (Bioclinica Inc.), who performed blinded assessment of all MRIs for ARIA-edema/effusion (ARIA-E) and/or ARIA-microhemorrhage/hemosiderosis (ARIA-H). Radiographic evidence of ARIA-E was followed with serial MRI until resolution. Radiographic evidence of incident hemorrhage(s) was followed-up with MRI within approximately 2 weeks of observation to assess stability.

Samples were collected at pre-infusion, ≤10 minutes, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours, and weeks 1, 2, 3, 6, 11, and 24 after dosing, with periodic biomarker sampling. A validated sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to quantify concentrations of aducanumab in serum. Microtiter plates were coated with anti-idiotype aducanumab antibody, followed by blocking, washing, and incubation with 1/100 diluted calibrators, controls, and samples. A horseradish-peroxidase–conjugated anti-human IgG and tetramethyl benzidine (TMB) substrate were used to detect bound aducanumab. The standard curve range was 0.2–10 μg/mL for aducanumab in human serum. Samples measuring above 10 μg/mL were reanalyzed at an appropriate dilution. Sample results below 0.2 μg/mL were reported as below the limit of quantitation.

Anti-drug antibodies (ADA) were measured in serum using a screening assay based on a bridging solution ELISA format. Samples (including positive and negative controls) were diluted 1:100 with phosphate-buffered saline/Casein containing an equimolar mixture of biotin-aducanumab and digoxigenin (DIG)-aducanumab and incubated overnight at 2–8°C. The bridging complexes formed of ADA, biotin-aducanumab, and DIG-aducanumab molecules were captured on a streptavidin-coated Nunc plate and detected using anti-DIG–HRP conjugate and TMB substrate. Enzymatic reaction was stopped by the addition of sulfuric acid. Absorbance read at 450 nm was proportional to the amount of ADA. A sample was considered positive when: average (sample signal) ≥ screening assay cut point (1.16 × mean negative control signal).

Samples that tested positive in the screening assay were further evaluated in a confirmatory assay using excess unlabeled aducanumab in a competitive binding format to demonstrate the specificity of the binding interactions in the antibody and/or labeled drug complex. Briefly, serum samples were incubated overnight with either labeled drugs alone or labeled drugs with excess unlabeled aducanumab (final concentration 20 μg/mL) added. After the overnight step, the remainder of the assay procedure was the same as for the screening assay. Percentage inhibition of signal by the excess unlabeled drug should be ≥ confirmatory cut point to confirm the sample as a true positive. The titer was also assessed for confirmed positive samples using the screening assay as the reciprocal of the lowest sample dilution, where: average (sample signal) ≥ titration assay cut point (1.16 × mean negative control signal).

Aβ40 and Aβ42 were measured in plasma using the qualified MULTI-SPOT Human/Rodent (4G8) Abeta Triplex Ultra-Sensitive Assay (Meso Scale Discovery) per manufacturer's protocol.

The Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (13 items; ADAS-Cog 13) was administered at day 1 and at weeks 3 and 24.

2.3. Statistical analysis

For all analyses, all patients assigned to placebo were treated as a single group. The safety population was defined as all patients who were randomized and dosed with study treatment. The PK analysis population also had at least one measureable aducanumab serum concentration. Other analyses populations also had at least one postdose sample collected for the parameter being studied.

AEs were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities classification and summarized by treatment group, by severity, and relationship to study treatment based on investigator assessment. PK parameters were calculated using noncompartmental methods and summary statistics presented by treatment group. Summary statistics for the potential biomarkers and measurements were presented by treatment group.

The sample size was not based on statistical considerations. Cohorts of 8 patients were considered adequate to initially characterize the safety, tolerability, and PK profile of aducanumab.

3. Results

3.1. Patients

A total of 53 patients were randomized and received treatment (39 with aducanumab and 14 with placebo) between June 2011 and August 2013 at three sites in the United States (see Acknowledgments). One patient withdrew from the study. Three patients received the highest dose of 60 mg/kg. Per protocol, further dosing at 60 mg/kg, was terminated after two of these patients presented with ARIA-E; however, the third patient had already been randomized and received treatment.

Baseline patient demographics and characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 67.7 years (range, 55–84 years), and 36% of patients were apolipoprotein E ε4 (APOE ε4) carriers (heterozygote 23%; homozygote 13%). There were higher percentages of APOE ε4 carriers in the 10-mg/kg (67%) and 30-mg/kg (50%) aducanumab groups than in the other groups (placebo [29%]; 0.3, 1, 20, and 60 mg/kg [each 33%]; 3 mg/kg [17%]). The median time since first AD symptom was 4.9 years (range, 1.6–17.0 years) and since first AD diagnosis was 2.6 years (0.5–12.9 years). The mean (standard deviation [SD]) screening MMSE score was 21.3 (3.6). The mean (SD) ADAS-Cog 13 score was 20.7 (12.9) but was not consistent across treatment groups at approximately 2 times higher in the 10-mg/kg treatment group than in the placebo and 0.3- and 20-mg/kg treatment groups.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and characteristics

| Characteristic | Placebo (N = 14) | Aducanumab dose (mg/kg) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.3 (N = 6) | 1 (N = 6) | 3 (N = 6) | 10 (N = 6) | 20 (N = 6) | 30 (N = 6) | 60 (N = 3) | ||

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 66.9 (8.7) | 72.0 (8.4) | 67.0 (8.8) | 63.0 (5.0) | 72.7 (4.5) | 66.8 (8.9) | 63.3 (9.0) | 73.7 (9.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 5 (36) | 4 (67) | 2 (33) | 3 (50) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 0 |

| Ethnic origin, n (%) | ||||||||

| Asian | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Black or African American | 1 (7) | 1 (17) | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| White | 13 (93) | 4 (67) | 6 (100) | 5 (83) | 5 (83) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 3 (100) |

| Other | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| APOE ε4 carriers, n (%) | 4 (29) | 2 (33) | 2 (33) | 1 (17) | 4 (67) | 2 (33) | 3 (50) | 1 (33) |

| Weight, kg, mean (SD) | 78 (16) | 80 (16) | 72 (15) | 71 (11) | 62 (9) | 68 (6) | 66 (3) | 76 (12) |

| Years since first AD symptoms, median (range) | 4.9 (2.4–12.9) | 7.0 (2.0–17.0) | 6.3 (2.7–11.2) | 5.0 (2.5–7.5) | 4.2 (2.7–6.7) | 4.9 (3.8–7.8) | 2.9 (1.6–9.1) | 3.6 (2.6–7.6) |

| Years since first AD diagnosis, median (range) | 2.6 (0.9–12.9) | 2 (1.0–12.9) | 3.8 (0.5–6.3) | 3.9 (2.0–4.5) | 3.2 (0.6–6.7) | 2.5 (0.8–4.8) | 1.9 (0.9–4.7) | 2.6 (0.6–2.6) |

| MMSE, mean (SD) | 22.1 (2.4) | 23.0 (1.9) | 22.0 (3.4) | 18.3 (2.7) | 18.3 (4.9) | 23.0 (3.1) | 19.8 (4.6) | 24.7 (1.5) |

| ADAS-Cog 13, mean (SD) | 17.0 (6.5) | 16.8 (10.3) | 19.2 (6.8) | 26.6 (16.4) | 32.8 (20.8) | 15.0 (8.7) | 23.6 (18.0) | 19.6 (9.0) |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; ADAS-Cog 13, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (13 items); APOE ε4, apolipoprotein E ε4; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; SD, standard deviation.

Donepezil was the most common concomitant medication taken overall (28 patients [53%]). Other concomitant AD medications were memantine (6 [11%]), rivastigmine (3 [6%]), and galantamine (2 [4%]).

3.2. Safety and tolerability

All enrolled patients received treatment and were included in the safety population. Of 39 patients who received aducanumab, 21 (54%) experienced an AE, with AEs in 10 patients (26%) considered to be treatment related (Table 2). The most common AEs (≥10% of patients) with aducanumab were headache (8 patients [21%]), diarrhea (5 [13%]), and upper respiratory tract infection (4 [10%]); in the placebo group, headache was reported by two patients (14%) and diarrhea by one patient (7%; Table 2). ARIA-E was observed in all three patients who received 60 mg/kg and was assessed as serious. One of these three patients (APOE ε4 noncarrier) was reported to have severe treatment-related ARIA (symptomatic ARIA-E and ARIA-H; in this case, one new incident microhemorrhage) on day 22, which had completely resolved on MRI by day 106. An attendant symptom, mild gait disturbance, was observed on day 56 and resolved by day 84. Another of these three patients (APOE ε4 noncarrier) had mild treatment-related symptomatic ARIA-E on day 22 with mild diarrhea, moderate cognitive disorder, headache, and pyrexia (moderate fever), and severe pain, all starting on day 2 and resolving within 1–2 days. ARIA-E completely resolved on MRI by day 78. The third patient (APOE ε4 carrier) had moderate treatment-related symptomatic ARIA-E on day 31, which had completely resolved on MRI by day 59. This patient had “flu-like” symptoms beginning 2–4 days after dose that included severe headache and malaise with resolution between 2–14 days. Complete resolution of ARIA-E was reported for each patient. No cases of ARIA were observed at aducanumab doses ≤30 mg/kg.

Table 2.

Safety and tolerability: AE summary and most common AEs∗

| Adverse event | Placebo (N = 14) | Aducanumab dose (mg/kg) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.3 (N = 6) | 1 (N = 6) | 3 (N = 6) | 10 (N = 6) | 20 (N = 6) | 30 (N = 6) | 60 (N = 3) | Total (N = 39) | ||

| Summary of AEs | |||||||||

| Any AE, n (%) | 5 (36) | 1 (17) | 5 (83) | 2 (33) | 4 (67) | 1 (17) | 5 (83) | 3 (100) | 21 (54) |

| Moderate or severe AE, n (%) | 2 (14) | 0 | 2 (33) | 1 (17) | 2 (33) | 0 | 1 (17) | 3 (100) | 9 (23) |

| Severe AE, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (100) | 3 (8) |

| SAE, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (100) | 3 (8) |

| Discontinuing or withdrawing due to an AE, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Treatment-related AE, n (%) | 2 (14) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 0 | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 3 (50) | 3 (100) | 10 (26) |

| Most common AEs∗ | |||||||||

| Headache, n (%) | 2 (14) | 0 | 2 (33) | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 3 (50) | 2 (67) | 8 (21) |

| Diarrhea, n (%) | 1 (7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 2 (67) | 5 (13) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (33) | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 1 (33) | 4 (10) |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; SAE, serious adverse event.

Reported by ≥ 10% of patients who received aducanumab.

Doses of aducanumab up to 30 mg/kg were well tolerated with no severe AEs or SAEs. SAEs were only reported by the three patients who received 60 mg/kg aducanumab (reported above); there were 4 AEs assessed as severe (ARIA, headache, malaise, and pain; each in one patient), and all were assessed as treatment related. The most common treatment-related AEs (≥2 patients at a particular dose level) were headache (3 and 2 patients at 30 and 60 mg/kg, respectively), ARIA (3 patients at 60 mg/kg), and diarrhea and pyrexia (each 2 patients at 60 mg/kg). There were no deaths, discontinuations, or withdrawals due to AEs.

Clinical laboratory results, vital signs, physical, and neurologic examinations, and ECG findings were as expected or consistent with a population of older patients with mild-to-moderate AD. No subject had ECGs (12-lead or Holter) reported as an abnormal AE.

The analysis population for immunogenicity included all enrolled patients. No patients were positive for anti-aducanumab antibodies related to aducanumab treatment. Two aducanumab-treated patients (2 of 39 [5%]), both in the 3-mg/kg dose group, and two patients (2 of 14 [14%]) in the placebo group were positive for ADA before and after treatment. The titers of ADA in positive patient samples were low, within one or two dilutions from the detection limit and remained stable throughout time within acceptable ±2-fold variability of titers. There was no impact of anti-drug activity on safety.

3.3. PK

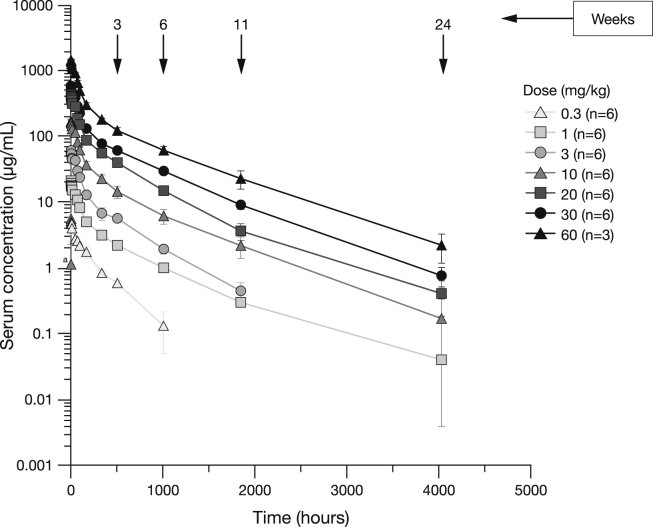

Mean aducanumab serum concentrations throughout time are illustrated in Fig. 1. Quantifiable mean concentrations of aducanumab generally reached a maximum (Cmax) within the first 30 minutes post end of the 2-hour infusion at 10, 20, 30, and 60 mg/kg. A summary of PK parameters is shown in Table 3. Mean Cmax and area AUCinf increased dose-proportionally between 0.3 mg/kg and 60 mg/kg. Median time to Cmax (Tmax) ranged from 2.5 to 3.3 hours. Mean clearance, terminal elimination half-life (t½), and volume of distribution (data not shown) did not appear to be affected by increasing doses.

Fig. 1.

Serum concentration (mean ± SE) of aducanumab (logarithmic scale) over time after a single dose. aOne patient in the 10 mg/kg group had a measurable concentration of aducanumab at the pre-dose sample (0) time. Abbreviation: SE, standard error.

Table 3.

Summary of PK parameters of aducanumab

| Parameter | Mean (SE)∗ |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aducanumab dose (mg/kg) | |||||||

| 0.3 (N = 6) | 1.0 (N = 6) | 3.0 (N = 6) | 10.0 (N = 6) | 20.0 (N = 6) | 30.0 (N = 6) | 60.0 (N = 3) | |

| AUCinf, μg•h/mL | 1000 (100) | 4420 (443) | 10,400 (1020) | 31,400 (5210) | 76,600 (6070) | 124,000 (8180) | 279,000 (21,400) |

| AUClast, μg•h/mL | 797 (76) | 4090 (415) | 10,100 (942) | 30,300 (5020) | 75,600 (6170) | 124,000 (7940) | 277,000 (20,300) |

| t1/2, h | 326 (59) | 709 (235) | 377 (39) | 478 (99) | 465 (56) | 571 (42) | 606 (61) |

| Cmax, μg/mL | 6.5 (0.8) | 21.8 (1.1) | 66.9 (3.6) | 182.7 (19.7) | 460.0 (10.3) | 628.7 (32.4) | 1530.0 (37.9) |

| Tmax,∗ h | 3.3 (2.1–147.0) | 2.5 (2.5–3.0) | 3.2 (2.6–4.6) | 3.0 (2.5–6.0) | 2.8 (2.6–3.0) | 3.0 (2.6–4.5) | 2.6 (2.2–3.6) |

| Cl, mL/h/kg | 0.31 (0.03) | 0.24 (0.02) | 0.30 (0.03) | 0.39 (0.09) | 0.27 (0.02) | 0.25 (0.02) | 0.22 (0.02) |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the serum concentration–time profile; AUCinf, AUC from time 0 extrapolated to infinite time; AUClast, AUC from time 0 to time of last quantifiable concentration; Cmax, maximum serum concentration; Cl, systemic clearance; SE, standard error; Tmax, time to Cmax; PK, pharmacokinetic; t1/2, terminal elimination half-life.

All patients treated were evaluable for PK parameters.

Tmax is median (range).

The presence of ADA in two aducanumab-treated patients at baseline and during the study had no impact on aducanumab concentrations in serum.

3.4. Pharmacodynamics

Exploratory objectives were to assess the effects of aducanumab on potential blood biomarkers and cognition. There was no significant effect of aducanumab on plasma Aβ between 0.3- and 30-mg/kg doses (Fig. 2). The highest dose of 60 mg/kg aducanumab appeared to demonstrate an increase in both Aβ40 and Aβ42. However, at 60 mg/kg, both Aβ40 and Aβ42 also demonstrated higher baseline/pre-dose values and higher patient variability (may be due to small sample size) than the lower dose cohort patients (mean baseline values: Aβ40—383, 453, 331, 311, 358, 345, 346, and 614 pg/mL; Aβ42—59, 67, 59, 54, 64, 54, 52, and 85 pg/mL for placebo, 0.3, 1.0, 3.0, 10, 20, 30, 60 mg/kg, respectively). No effect was observed for change in mean ADAS-Cog 13 scores after administration of aducanumab (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Mean (SE) Aβ40 and Aβ42 plasma levels (extracted) after a single dose of aducanumab or placebo. an = 13 at W3 and W6; bn = 5 at W3. Abbreviations: D, day; H, hour; SE, standard error; W, week.

Fig. 3.

Change from baseline in ADAS-Cog 13 Score (Mean ± SE) after a single dose of aducanumab at weeks 3 and 24. Abbreviations: ADAS-Cog 13, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale; SE, standard error.

4. Discussion

This was the first study of aducanumab in humans. The study was conducted in patients with mild-to-moderate AD to enable characterization of the initial safety, tolerability, and PK of single escalating-doses of aducanumab. Aducanumab demonstrated acceptable safety and tolerability, and linear PK at single doses up to 30 mg/kg—the maximum tolerated dose. The only SAEs were symptomatic ARIA-E, which developed in all 3 patients who received the highest dose of 60 mg/kg; follow-up MRIs showed that these events completely resolved. One of these 3 patients was an APOE ε4 carrier. Interim results from the 12-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase of a phase 1b multiple-dose study of aducanumab in patients with prodromal or mild AD have also reported dose-dependent ARIA as the main safety and tolerability finding and showed dose- and time-dependent reductions in Aβ plaque with aducanumab [18].

It is well recognized that treatment with some amyloid-targeting drug candidates, including the monoclonal antibodies bapineuzumab and gantenerumab, are associated with incident cases of ARIA [19], [20]. These rates of ARIA, however, may be under-represented in small single-dose studies which may have variable APOE ε4 status distribution between dose cohorts. These abnormalities can include ARIA-E and ARIA-H and are readily detectable by standard MRI sequences (fluid attenuated inversion recovery [FLAIR]/T2 for ARIA-E and T2*/gradient echo for ARIA-H) [21]. In the single ascending-dose study of bapineuzumab, ARIA were observed in 3 of 10 patients who received 5 mg/kg bapineuzumab, with no cases in the 0.5- and 1.5-mg/kg groups, and all resolved over time [22]. Retrospective analysis of data from three phase 2 studies and the results of two phase 3 studies of bapineuzumab showed that ARIA-E incidence increased with dose and APOE ε4 copy number and most cases were identified after the first or second dose [19], [21]. In our study, ARIAs were only observed in the 60-mg/kg dose group. Further studies should stratify/enroll patients based on APOE ε4 status to ensure that the clinical trial population reflects the AD population.

There were no treatment-induced immunogenicity responses against aducanumab. All 4 ADA-positive patients had pre-existing ADA activity that remained relatively constant throughout the study. It is not known at this time if this pre-existing activity was caused by anti-aducanumab antibodies or some other matrix components. For example, labeled drug in the ADA assay could potentially be bridged by some Aβ peptide aggregates in circulation that are recognized by aducanumab. There was no apparent impact of anti-drug activity on PK or safety.

Mean AUCinf in this study was between approximately 1000 μg•h/mL at 0.3 mg/kg aducanumab (as predicted, see Methods) and 279,000 μg•h/mL at 60 mg/kg. The mean exposure at 60 mg/kg did not exceed the mean exposure in APP Tg2576 transgenic mice given 500 mg/kg (402,000 μg•h/mL). Aducanumab Cmax and AUCinf increased in a dose-proportional manner between 0.3 mg/kg and 60 mg/kg. Tmax was comparable between the dose groups. Increasing doses of aducanumab did not alter its clearance, t½, or volume of distribution.

Exploratory objectives of this study were to assess the effects of aducanumab on potential plasma biomarkers and on cognition. Systemic administration of antibodies that bind to soluble Aβ typically leads to an increase in plasma Aβ concentrations due to stabilization of the peptide in circulation [22]. Although there was an increase in plasma levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42 at 60 mg/kg, aducanumab did not appear to significantly affect plasma levels of Aβ40 or Aβ42 at the lower doses (0.3 mg/kg to 30 mg/kg). The largely unaffected soluble Aβ levels are consistent with the very low affinity of aducanumab for soluble monomeric Aβ. At 60 mg/kg, both Aβ40 and Aβ42 also demonstrated higher baseline/pre-dose values and higher patient variability than the lower dose cohort patients, thus complicating the interpretation. No dose-dependent response was observed for change in mean ADAS-Cog 13 scores after single-dose administration of aducanumab.

The limitations of the present study include the small sample size of the cohorts and the use of a sequential, dose-escalation design rather than a parallel-arm design. Thus, the analysis using a pooled placebo group does not align the randomization in the study design.

In summary, a single dose of aducanumab up to 30 mg/kg was well tolerated and the PK well behaved. Dose-limiting transient ARIAs were observed in the 60-mg/kg dose group, resulting in termination of further dosing in that cohort. Increasing doses of aducanumab (0.3–60 mg/kg) did not alter its overall clearance indicating linear PK. No unexpected safety concerns associated with the use of aducanumab in patients with mild-to-moderate AD were observed. The results of this study support the continued evaluation of aducanumab as a potential disease-modifying therapy for patients with AD.

Research in context.

-

1.

Systematic review: A standard literature search (e.g., PubMed) was used to search for original articles, and further relevant information was identified from authors' own experience and knowledge of the recent literature.

-

2.

Interpretation: This is the first study of aducanumab in humans. This study provides an initial characterization of the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetic profile of aducanumab after escalating single-dose administration in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease (AD). Aducanumab was well tolerated at doses up to 30 mg/kg. The dose-limiting toxicity was transient amyloid-related imaging abnormalities, which were observed in all three patients at 60 mg/kg aducanumab. Serum aducanumab exposures were dose proportional. There were no treatment-induced immunogenicity responses against aducanumab. Soluble amyloid beta levels were largely unaffected—consistent with aducanumab-binding properties.

-

3.

Future directions: These results support the further evaluation of the clinical pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and safety of this potential disease-modifying therapy for AD.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the study patients and their family members, and the investigators (Dr Craig Curtis, Compass Research Ph 1, LLC, Orlando, FL; Dr Beth Safirstein, MD Clinical, Hallandale Beach, FL; and Dr Hakop Gevorkyan, California Clinical Trials Medical Group, Glendale, CA) and their site personnel. Medical writing support, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Annette Smith, PhD, at Complete Medical Communications and was funded by Biogen.

The study was funded by Biogen.

Author contributions: J.F., L.W., A.M., J.O., and J.S. wrote the article; J.F. and J.S. designed the research; L.W., H.S., K.L., and J.S. performed the research; J.F., L.W., A.M., J.O., and J.S. analyzed the data. Biogen reviewed and provided feedback on the paper. The authors had full editorial control of the paper and provided their final approval of all content.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: L.W., A.M., and J.O. are employees of Biogen and may hold stocks/stock options in Biogen. J.F., H.S., K.L., and J.S. are former employees of Biogen. Current affiliations are J.F., retired; K.L., Dedham High School, Dedham, MA, USA; and J.S., F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland.

References

- 1.Alzheimer's Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2009. Available at: https://www.alz.co.uk/research/files/WorldAlzheimerReport.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2016.

- 2.Hardy J., Selkoe D.J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardy J.A., Higgins G.A. Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256:184–185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hampel H., Shen Y., Walsh D.M., Aisen P., Shaw L.M., Zetterberg H. Biological markers of amyloid beta-related mechanisms in Alzheimer's disease. Exp Neurol. 2010;223:334–346. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villemagne V.L., Burnham S., Bourgeat P., Brown B., Ellis K.A., Salvado O. Amyloid ß deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer's disease: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:357–367. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jack C.R., Jr., Wiste H.J., Lesnick T.G., Weigand S.D., Knopman D.S., Vemuri P. Brain beta-amyloid load approaches a plateau. Neurology. 2013;80:890–896. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182840bbe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koffie R.M., Meyer-Luehmann M., Hashimoto T., Adams K.W., Mielke M.L., Garcia-Alloza M. Oligomeric amyloid beta associates with postsynaptic densities and correlates with excitatory synapse loss near senile plaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4012–4017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811698106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuchibhotla K.V., Goldman S.T., Lattarulo C.R., Wu H.Y., Hyman B.T., Bacskai B.J. Abeta plaques lead to aberrant regulation of calcium homeostasis in vivo resulting in structural and functional disruption of neuronal networks. Neuron. 2008;59:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer-Luehmann M., Spires-Jones T.L., Prada C., Garcia-Alloza M., de C.A., Rozkalne A. Rapid appearance and local toxicity of amyloid-beta plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2008;451:720–724. doi: 10.1038/nature06616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer-Luehmann M., Mielke M., Spires-Jones T.L., Stoothoff W., Jones P., Bacskai B.J. A reporter of local dendritic translocation shows plaque-related loss of neural system function in APP-transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12636–12640. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1948-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rozkalne A., Spires-Jones T.L., Stern E.A., Hyman B.T. A single dose of passive immunotherapy has extended benefits on synapses and neurites in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Brain Res. 2009;1280:178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spires-Jones T.L., Mielke M.L., Rozkalne A., Meyer-Luehmann M., de C.A., Bacskai B.J. Passive immunotherapy rapidly increases structural plasticity in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;33:213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hock C., Konietzko U., Streffer J.R., Tracy J., Signorell A., Muller-Tillmanns B. Antibodies against beta-amyloid slow cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2003;38:547–554. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xue D., Zhao M., Wang Y.J., Wang L., Yang Y., Wang S.W. A multifunctional peptide rescues memory deficits in Alzheimer's disease transgenic mice by inhibiting Abeta42-induced cytotoxicity and increasing microglial phagocytosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;46:701–709. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bussiere T., Weinreb P.H., Dunstan R.W., Qian F., Arast M.F., Li M. Differential in vitro and in vivo binding profiles of BIIB037 and other anti-abeta clinical antibody candidates. Neurodegener Dis. 2013;11(Suppl 1) [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKhann G., Drachman D., Folstein M., Katzman R., Price D., Stadlan E.M. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Psychiatric Association . 4th ed. 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sevigny J., Chiao P., Williams L., Chen T., Ling Y., O'Gorman J. Aducanumab (BIIB037), an anti-amyloid beta monoclonal antibody, in patients with prodromal or mild Alzheimer's disease: Interim results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase 1b study. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:P277. (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salloway S., Sperling R., Fox N.C., Blennow K., Klunk W., Raskind M. Two Phase 3 Trials of Bapineuzumab in Mild-to-Moderate Alzheimer's Disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:322–333. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostrowitzki S., Deptula D., Thurfjell L., Barkhof F., Bohrmann B., Brooks D.J. Mechanism of Amyloid Removal in Patients with Alzheimer Disease Treated With Gantenerumab. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:198–207. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sperling R., Salloway S., Brooks D.J., Tampieri D., Barakos J., Fox N.C. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) in Alzheimer's disease patients treated with bapineuzumab: A retrospective analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:241–249. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70015-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Black R.S., Sperling R.A., Safirstein B., Motter R.N., Pallay A., Nichols A. A single ascending dose study of bapineuzumab in patients with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24:198–203. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181c53b00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]