Abstract

Introduction

This study explores clinicians' views on and experiences with when, how, and by whom decisions about diagnostic testing for Alzheimer's disease are made and how test results are discussed with patients.

Methods

Following a preparatory focus group with 13 neurologists and geriatricians, we disseminated an online questionnaire among 200 memory clinic clinicians.

Results

Respondents were 95 neurologists and geriatricians (response rate 47.5%). Clinicians (74%) indicated that decisions about testing are made before the first encounter, yet they favored a shared decision-making approach. Patient involvement seems limited to receiving information. Clinicians with less tolerance for uncertainty preferred a bigger say in decisions (P < .05). Clinicians indicated to always communicate the diagnosis (94%), results of different tests (88%–96%), and risk of developing dementia (66%).

Discussion

Clinicians favor patient involvement in deciding about diagnostic testing, but conversations about decisions and test results can be improved and supported.

Keywords: Shared decision making, Communication, Dementia, Alzheimer, Diagnostic testing

1. Introduction

The NIA-AA criteria state that diagnostic tests for Alzheimer's disease (AD), such as MRI and biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), should be used “when available and deemed appropriate by the clinician” [1]. Information on when to use which test or how to involve patients and their families in this decision is not specified, leaving room for broad practice variation in diagnostic testing. At the same time, there has been a shift toward earlier diagnosis of AD, which has led to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to AD being regarded as a formal diagnosis in the AD spectrum [2]. A diagnosis of AD or MCI may have great social, emotional, and practical implications for patients and their families, whereas at present, there is still no cure available. On the other hand, an early diagnosis could have the advantage for patients and their families to be more involved in management decisions and planning of care and help them prepare for the future [3]. Moreover, it may meet their needs to minimize uncertainty about the nature of the patient's symptoms and what may lay ahead [4]. However, test results do not always offer patients and their families the certainty or reassurance they were seeking for [5]. Results of different diagnostic tests may be equivocal or conflicting, making it challenging for clinicians to interpret these results and discuss them with the patient, especially in the context of MCI [6].

All these issues contribute to the diagnostic challenges in AD, that is, how to decide about diagnostic testing, and how to communicate test results to patients and caregivers. As it is likely that patients will weigh the advantages and disadvantages of testing differently, clinicians and patients can engage in a shared decision-making (SDM) process to ensure patients' views and preferences are considered in deciding about testing [7], [8]. SDM has been studied extensively in other clinical contexts [9], but only a few studies are available in the context of MCI and dementia. These studies show that although both patients and their caregivers prefer to be actively involved in decisions regarding their care [10], [11], [12], especially, patients are involved to a limited extent only [13], [14]. However, these previous studies involved patients with an established diagnosis of MCI or dementia and concerned SDM in the context of decisions about subsequent disease, symptom, or care management.

As a first step in studying SDM in the diagnostic care of AD, the aim of this study was to explore clinicians' views on and experiences with (1) when and how to decide about diagnostic testing for AD, (2) the role of the patient and clinician(s) involved in this decision, and (3) which test results to communicate to patients and how. Finally, we assessed whether clinicians' views and experiences were associated with their characteristics (sociodemographic, work-related, and tolerance for uncertainty in care).

2. Methods

2.1. Design

This study was conducted as part of a larger project on the (cost)effectiveness of diagnostic tests for AD and MCI [15]. To explore emerging issues as a preparation to a survey, we first conducted an in-person focus group with Dutch neurologists and geriatricians working in a memory clinic. We then disseminated an online survey among >200 neurologists and geriatricians working at one of the 120 Dutch (local) memory clinics.

2.2. Focus group

Neurologists and geriatricians who registered for a 1-day national conference on dementia were invited to participate in a focus group. During the 2-hour focus group, which was led by a psychologist experienced in conducting focus groups (E.M.A.S.), we discussed clinicians' dilemmas regarding diagnostic testing for AD (e.g., how and when it is decided to initiate which diagnostic tests), the role of the patient in this decision, and which test results or diagnostic labels are communicated to the patient and how. The audio recording of the focus group discussion was transcribed verbatim and analyzed using MaxQDA software.

2.3. Survey

Based on the literature and the themes that emerged from the focus group, we developed an online survey to assess clinicians' views nationwide. The patients' caregivers have an important role in this setting, but given that SDM in diagnostic care is still novel, we decided to present patients and caregivers as one party in this survey. At the start of the survey, we explicitly stated to read “patients and caregivers” whenever we spoke of “patients.” The survey contained the following scales and items to address our aims:

-

-

Clinicians' sociodemographic and work-related characteristics, such as age, gender, specialty (neurology or geriatrics), type of hospital (academic, nonacademic teaching hospital, nonteaching hospital, or other), and level of experience (years since specialization and number of new patients per month).

-

-

The Physicians' Reaction to Uncertainty Scale to assess clinicians' affective reactions to uncertainty in health care. This scale consists of items that address the emotional reactions and concerns engendered in clinicians who face clinical situations that are not easily resolved and clinicians' behavior to cope with those emotions and concerns [16]. We used the subscales “Anxiety due to uncertainty” and “Reluctance to disclose uncertainty to patients (excluding one item on the use of treatments)” (six-point Likert scale strongly disagree to strongly agree). Scores were calculated by summing the responses to the items of the two subscales, with a higher score meaning less tolerance for uncertainty (score range 9–54).

Scales and items that are related to deciding about testing:

-

-

Clinicians' perceived reason for the prediagnostic clinician-patient encounter (see Table 1, make a top three) [17].

-

-

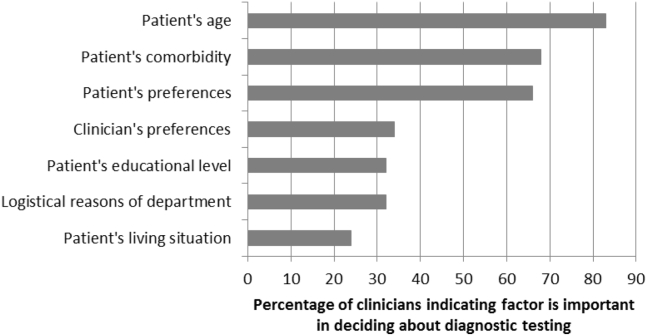

The extent to which clinicians perceive that the decision about whether to initiate testing has been made before the prediagnostic clinician-patient encounter (six-point Likert scale not at all to very much); who has the biggest say in this decision (select one from treating specialist, multidisciplinary team, general practitioner, and patient/caregiver); and which factors are important in this decision (see Fig. 1, select one or more).

-

-

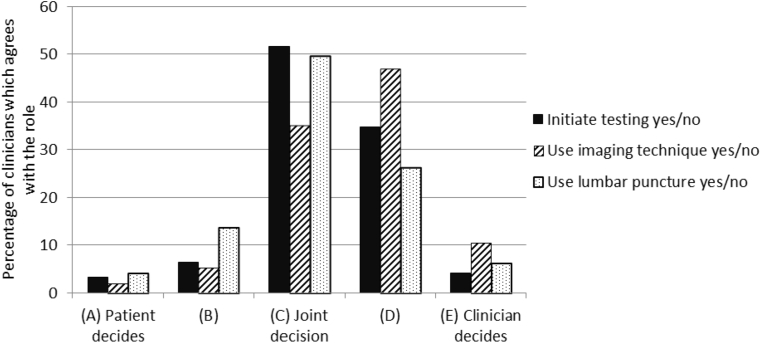

The Control Preferences Scale [18], [19] to assess clinicians' preferred role in deciding about whether to (1) initiate diagnostic testing, (2) use imaging techniques, and (3) perform lumbar puncture for CSF biomarkers. Answer categories ranged from (1) the patient makes the decision alone, through (2) the patient makes the decision after considering the doctor's opinion, (3) the patient and doctor make the decision together, (4) the doctor makes the decision after considering the patient's opinion, to (5) the doctor makes the decision alone.

-

-

An adapted version of the nine-item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire [20] in which clinicians responded to nine statements on SDM-related behavior they generally execute (see Table 2, six-point Likert scale completely disagree to completely agree).

-

-

Whether clinicians use aids to communicate about the decision to initiate diagnostic testing (no/yes); and if so, which (open, optional question).

Table 1.

Reasons for the prediagnostic clinician-patient encounter

| Most important, N (%) | In top 3, N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Explaining diagnostic route | 23 (24) | 61 (64) |

| Deciding whether to initiate diagnostic testing | 23 (24) | 41 (43) |

| Conducting diagnostic tests | 16 (17) | 52 (55) |

| Explaining possible diagnosis/prognosis | 10 (11) | 28 (29) |

| Deciding which tests to initiate | 8 (8) | 51 (54) |

| Explaining content of different diagnostic tests | 2 (2) | 26 (27) |

| Explaining practical issues around illness | 1 (1) | 9 (10) |

Fig. 1.

Importance of factors in deciding about diagnostic testing.

Table 2.

Perceived role in decision making (adapted version of SDM-Q-9)

| In general, I… | Mean score (0–5 scale) |

|---|---|

|

3.1 |

|

2.8 |

|

3.2 |

|

3.3 |

|

4.0 |

|

2.2 |

|

2.7 |

|

2.5 |

|

3.9 |

Abbreviation: SDM-Q-9, nine-item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire.

Items that are related to communication of test results:

-

-

Whether clinicians communicate the following outcomes of testing: (1) diagnosis, (2) outcomes of neuropsychological examination, (3) outcomes of structural brain imaging, (4) outcomes of lumbar puncture (select one from never, sometimes, often, or always).

-

-

How diagnosis of cognitive symptoms of mild severity is discussed with patients (select one or more from as memory loss, as MCI, as possible early AD, as possible early dementia, by emphasizing that there is no AD or dementia, and other) [2].

-

-

Eight statements on the potential benefits, drawbacks, and limitations of communicating MCI as a clinical diagnosis (see Table 3, five-point Likert scale strongly disagree to strongly agree) [2].

-

-

Whether the probability of developing AD is discussed with patients with MCI (select from no, yes, and only on request of the patient/caregiver).

-

-

Whether clinicians use visual aids to communicate test results (select from always, often, sometimes, or never) and if so, which (open, optional question); whether patients receive written information on their diagnosis (select from no, yes, and only on request of patient/caregiver) and if so, what kind of information (select from general information and personalized information).

Table 3.

Perceptions of benefits, drawbacks, and limitations of MCI as a clinical diagnosis [2]

| Strongly disagree (%) | Somewhat disagree (%) | Neither agree nor disagree (%) | Somewhat agree (%) | Strongly agree (%) | Mean score (1–5 scale) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benefits | ||||||

| 1. Labeling the problem is helpful for patients and family members | 1 | 2 | 7 | 26 | 64 | 4.4 |

| 2. Diagnosis is useful so the patient can be more involved in planning for the future | 1 | 5 | 10 | 47 | 37 | 4.1 |

| 3. Diagnosis can be useful in motivating the patient to engage in risk-reduction activities | 4 | 7 | 23 | 44 | 21 | 3.7 |

| 4. Certain medications can be useful in treating some patients with MCI | 42 | 20 | 21 | 15 | 2 | 2.1 |

| Drawbacks and limitations | ||||||

| 5. MCI is too difficult to diagnose accurately or reliably | 18 | 23 | 27 | 24 | 7 | 2.8 |

| 6. Diagnosing MCI causes unnecessary worry for patients and family members | 27 | 34 | 19 | 18 | 2 | 2.3 |

| 7. MCI is usually better described as early Alzheimer's disease | 43 | 40 | 14 | 3 | 0 | 1.7 |

| 8. There is no approved treatment for MCI so it does not make sense to diagnose it | 52 | 35 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 1.6 |

Abbreviation: MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

A personal invitation to complete the anonymous online survey was sent to all neurologists and geriatricians of the Dutch Memory Clinic Network. A reminder was sent 3 and 5 weeks after the initial invitation.

2.4. Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to report clinicians' characteristics and responses to our questionnaire. To compare groups, we used t-tests, ANOVAs as appropriate. We studied associations using Spearman's rho analysis. Significance testing was done two-sided at α = 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Focus group

Ten neurologists and three geriatricians participated in the focus group. There were six male and seven female participants, which were affiliated to an academic hospital (N = 2), nonacademic teaching hospital (N = 6), nonteaching hospital (N = 3), or both an academic and nonacademic teaching hospital (N = 2).

Analyses suggested considerable practice variation in deciding about diagnostic testing and communicating test results. Clinicians indicated different approaches in whether and when (1) tests are performed parallel or sequential, (2) imaging techniques are used (CT and/or MRI), (3) extensive neuropsychological testing is conducted immediately or only if deemed necessary at a later stage, and (4) CSF biomarkers are obtained. In some clinics but not in others, factors as patient's age or educational level guide decisions on diagnostic testing. Different approaches emerged in the involvement of type of clinician (neurologist and/or geriatrician) in the pretesting phase. Most memory clinics have some sort of multidisciplinary team meeting, but this could take place either before or after performing the tests, and there was considerable variation in disciplines present in these meetings.

Clinicians indicated to value the patient's involvement in the decision on whether to initiate diagnostic testing, but they felt that ultimately, the decisions on which diagnostic test(s) to use should be made by the clinician.

Some clinicians indicated to briefly discuss possible test results in the pretesting encounter, to prepare patients and their families for possible outcomes, and because of patients' cognitive decline. Most indicated to find it difficult to present MCI as a diagnosis and were therefore hesitant to literally do so because of the uncertainty on the prognosis and the lack of adequate treatment. Clinicians mentioned that an alternative to presenting MCI as the diagnosis is to merely tell the patient that there are reasons to schedule a follow-up consultation.

3.2. Survey

We approached 208 clinicians to fill in the survey, of which eight (3.8%) could not be reached. Of the remaining 200 clinicians, 95 (47.5%) completed the survey. With the exception of two, all respondents completed their specialist training as neurologist or geriatrician. Demographic and work-related characteristics of respondents are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Characteristics of questionnaire respondents (N = 95)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Mean age, years ± SD (range) | 46 ± 8.8 (30–65) |

| Male gender | 46 (48) |

| Medical specialty | |

| Neurology | 47 (50) |

| Geriatrics | 48 (50) |

| Median time since specialization, years (range) | 10 (1–30) |

| Median number of new patients per month (range) | 12 (2–50) |

| Current institution∗ | |

| Academic | 8 (9) |

| Nonacademic teaching hospital | 46 (48) |

| Nonteaching hospital | 37 (39) |

| Other (both academic and nonacademic) | 3 (3) |

| Mean score Physicians' Reaction to Uncertainty Scale ± SD (range)† | 22.45 ± 5.8 (9–34) |

N = 1 missing.

Two subscales were used: “anxiety due to uncertainty” and “reluctance to disclose uncertainty to patients (excluding one item on the use of treatments).”

On the Physicians' Reaction to Uncertainty Scale, geriatricians revealed more tolerance for uncertainty than neurologists (M = 21.24 ± 6.3 and 23.64 ± 5.1, P < .05). There were no other associations between clinicians' tolerance for uncertainty and clinicians' age, gender, experience, or type of hospital (academic/nonacademic).

3.3. Prediagnostic encounter

Respondents indicated the most important reasons for the prediagnostic encounter were (1) explaining the diagnostic route and (2) deciding whether to initiate diagnostic testing (both N = 23, 24%; see Table 1). At the same time, most of the respondents (N = 70, 74%) indicated that decisions to initiate diagnostic testing are made before the start of the consultations (median score = 5 on 1–6 scale). According to the respondents, it is primarily the clinician (N = 57, 60%), followed by the patient/caregiver (N = 20, 21%), the multidisciplinary team (N = 12, 13%), and least often the general practitioner (N = 5, 5%) who have the biggest say in the decision to initiate testing. Clinicians consider patient's age and comorbidity the most important factors in this decision (Fig. 1).

3.4. Preferred and perceived role in decision making

Fig. 2 depicts the respondents' preferences regarding their role in deciding about diagnostic testing for AD. Clinicians who are less tolerant of uncertainty preferred to have a bigger say in decisions about whether to initiate diagnostic testing (Spearman's ρ = 0.27, P < .01) and whether to use imaging techniques (Spearman's ρ = 0.21, P < .05).

Fig. 2.

Clinicians' decisional role preferences for three possible decisions about diagnostic testing for AD. Abbreviation: AD, Alzheimer's disease.

Regarding their perceived role in decision making, respondents scored a mean of 28.1 ± 7.5 (0–45 scale) on the adapted nine-item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire (see Table 2). Of the specific SDM behaviors, clinicians indicated to most often provide information and make the final decision (i.e., highest scores on items 4, 5, and 9) and to least often discuss patient's preferences (i.e., lowest scores on items 6, 7, and 8). Clinicians with more years of experience indicated to involve patients more in decision making (ρ = 0.27, P < .01). Otherwise, there were no associations between preferred or perceived role in decision making and clinicians' age, gender, specialization, experience, type, or hospital (academic/nonacademic) or tolerance for uncertainty.

Twenty-two respondents (23%) indicated to use aids to communicate about the decision to initiate diagnostic testing. The aids that were mentioned were information leaflets (N = 19), web sites (N = 8), and drawings (N = 1).

3.5. Communication of test results

Respondents indicated that they always (N = 89, 94%) or often (N = 3, 3%) communicate the diagnosis to the patient. They indicated to always communicate results of different tests (neuropsychological tests: N = 91, 96%; imaging techniques: N = 90, 95%; lumbar puncture: N = 84, 88%), whenever such tests were used.

Respondents showed wide variation in the terms used to convey a diagnosis of cognitive symptoms of mild severity. They most often indicated to use MCI (N = 70, 74%), followed by memory loss (N = 41, 43%), possible early dementia (N = 30, 32%), emphasize that there is no AD or dementia (N = 17, 18%), or possible early AD (N = 15, 16%). In case of one of these diagnoses, two thirds of the clinicians (N = 63, 66%) indicated to always discuss the risk of developing dementia, while one of four (N = 24, 25%) said to do so only on request of the patient or caregiver, and six (7%) indicated to not convey these risks.

When we asked how clinicians evaluated the use of the label MCI, clinicians agreed more strongly with the perceived benefits than with the drawbacks (Table 3), indicating that they see the value of communicating MCI as a diagnosis to patients, even when they do not always use the specific terminology in clinical practice.

There was wide variation in the reported use of visual aids to communicate test results (always N = 31, 33%; often N = 36, 38%; sometimes N = 25, 26%; or never N = 2, 2%). Aids that were mentioned in the open (optional) questions were “looking together at the MRI and/or CT scans” (N = 10) or “drawings of the possible course of illness” (N = 1). Written information (leaflets) on the patient's diagnosis and/or on the test results is given always (N = 59, 62%) or on request of the patient/caregiver (N = 28, 30%). When such written information is provided, this could be either general information (N = 52, 55%) or individualized information (N = 33, 35%).

4. Discussion

This study shows that neurologists and geriatricians favor an SDM approach in deciding about diagnostic testing for AD. Yet, actual patient involvement still appears to be limited. Both the focus group and the online survey revealed considerable practice variation in deciding about diagnostic testing and communicating test results.

Clinicians indicated that deciding about diagnostic testing was among the most important reasons for the prediagnostic encounter but also felt that the decision has usually been made before this encounter. This could suggest a major role for patients, caregivers, and referring general practitioners in the decision, but their role is limited, according to the clinicians. Clinicians possibly assign themselves the major decisional role because they assume that patient's characteristics such as age and comorbidity are decisive, because they assume that all patients who are referred actually prefer to undergo testing, or because they assume that in light of the cognitive decline, patients are less able to decide what is best for them. Therefore, it may well be that when clinicians indicate to consider patients' preferences, they refer to these assumed preferences. Clinicians especially preferred patient involvement in decisions about performing a lumbar puncture, but less so for neuroimaging. This difference may be due to the physical impact of the procedures, as well as the lower threshold in local clinical guidelines to recommend imaging techniques.

Although clinicians felt decisions about testing are often made before the prediagnostic encounter, they still felt as involving patients to a great extent. Clinicians' self-report scores were higher than what is usually revealed in SDM observational studies [21]. Patient involvement seems to be limited however to offering them information, while other aspects of SDM such as creating choice awareness, discussing patient's preferences, and supporting deliberation are mostly neglected [22]. This is consistent with findings from a systematic review on SDM behavior in multiple disease contexts [21], and in line with long-led beliefs that providing patients with information is the most important aspect of SDM [9]. In addition, it may explain why the most common aids used by clinicians to discuss decisions about testing are informational tools, such as leaflets or web sites. These findings highlight the need to create awareness among clinicians on how to best bring SDM into practice and to provide them with the necessary knowledge, skills, and tools to do so.

Our focus group showed that clinicians find it difficult to convey an MCI diagnosis, as its implications are quite uncertain. On the other hand, nearly all clinicians in our survey (94%) indicated they always disclose the diagnosis to the patient. This is unexpectedly high compared with outcomes of earlier Western European surveys, in which between 39%–68% of clinicians indicated to communicate a dementia diagnosis to the patient [23], [24], [25]. Characteristics of the Dutch clinicians might be a possible explanation for this, but it is also likely that the beliefs on disclosing a dementia diagnosis have changed since these studies, which were mostly performed over 15 years ago. Indeed, in the last decade, progress has been made in the knowledge of AD and the diagnostic options available. In addition, the interest in communication around dementia diagnosis has increased [3]. We found variation in terms used to describe a diagnosis of cognitive symptoms of mild severity, which is consistent with findings from a survey in the United States [2]. Also in line with their findings, we found that clinicians value the benefits of communicating MCI as a clinical diagnosis to the patient more than the potential drawbacks. Future research should focus on observing routine conversations to assess whether and how diagnosis and test results are discussed with patients, how this information is interpreted by patients, and how conversation tools could aid in improving or simplifying these discussions.

In recent years, there has been a debate whether SDM approaches should differ according to the amount of uncertainty involved in a particular decision [26], [27], [28]. Indeed our study showed that clinicians who are less tolerant for uncertainty in health care prefer a more paternalistic approach in medical decision making, which is particularly interesting because of the uncertainty involved in both the prediagnostic and postdiagnostic phases of dementia care. Uncertainty about the patient's symptoms could lead patients to undergo diagnostic testing, but these tests could also lead to new uncertainties, as—especially in MCI or early AD—it is unclear how symptoms will progress and there is no cure available. On the other hand, the same test results may provide an explanation for patients' symptoms and may open the avenue to new options such as in care management. Finding the right timing to initiate testing and optimizing conversations about uncertainties are therefore crucial.

The field of SDM research and implementation is developing rapidly, but still little is known about communication and decision making on diagnostic testing in general, and more specifically for AD. Our study is timely in providing first insights in these topics, which are increasingly acknowledged to be of the utmost importance in high-quality patient-centered care [29]. Among the strengths of our study is that we were able to assess views and experiences of a heterogeneous and nationwide sample of involved clinicians, with a fairly good response rate [2]. Nevertheless, there is a possibility of response bias, in which clinicians with an interest in psychosocial care were more likely to participate. Another possible limitation is that outcomes are self-reported and may be subject to social desirability bias. Therefore, in an observational follow-up study, we are currently examining the communication between clinicians, patients, and their caregivers in routine pretesting and post-testing encounters. Combining results from the present survey study with observer-based findings will help us identify hurdles for effective communication and patient involvement in AD diagnostic care. In future research, the individual roles of patients, caregivers, and general practitioners in deciding about diagnostic testing should also be further explored.

In conclusion, our study showed that clinicians involved in decisions about diagnostic testing for AD favor an SDM approach with their patients and believe they actively involve patients in routine care. Nonetheless, their repertoire of SDM behavior may be broadened to also include other relevant steps of the SDM process besides information giving, such as creating choice awareness, discussing patient's preferences, and supporting deliberation. Most clinicians favored open and complete communication of diagnostic test results and the diagnosis to the patient, but they indicated large variation in how they do so. Clinicians should be provided with the necessary knowledge, skills, and tools to have conversations with their patients on decisions regarding diagnostic testing and on test results.

Research in Context.

-

1.

Systematic review: Decision making about diagnostic testing for Alzheimer's disease can be complex and little is known about clinicians’ views on and experiences with involving patients in decisions.

-

2.

Interpretation: We found that clinicians favor a shared decision-making (SDM) approach en that they intend to involve patients and caregivers in routine decision making. Yet, their SDM behavior seems limited to providing information, neglecting other relevant SDM elements. Clinicians who have less tolerance for uncertainty in health care prefer a more paternalistic approach, which is interesting in light of the uncertainty involved in both the prediagnostic and postdiagnostic phases of dementia care. Clinicians report various ways of communicating test results.

-

3.

Future directions: Observational research is needed to assess conversations and decision making behaviors in routine care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participating clinicians for their efforts. The authors also thank Sanne Schepers for her contribution in recruiting participants. This study is funded by ZonMW-Memorabel (ABIDE; grant number 70.73305-98-205), a project in the context of the Dutch Deltaplan Dementie. The authors thank ZonMw Memorabel for their support. Study sponsors had no involvement in the study design, the collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, the writing of the article, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Appendix. Focus group participants

The focus group participants were as follows: Niki M. Schoonenboom, MD, PhD and Hester van der Kroon, MD (Spaarne Gasthuis, Haarlem); Barbera van Harten, MD, PhD (Medisch Centrum Leeuwarden, Leeuwarden); Gerwin Roks, MD, PhD (Sint Elisabeth Ziekenhuis, Tilburg); Henry Weinstein, MD, PhD (Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis, Amsterdam); Annelies. W.E. Weverling, MD and Richard Molenaar, MD (Alrijne Ziekenhuis, Leiden); Rob J. van Marum, MD, PhD (Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, ’s-Hertogenbosch); Jules J. Claus, MD, PhD and Dirk Herderschee, MD, PhD (Tergooi Ziekenhuis, Blaricum); Femke Bouwman, MD, PhD, Tanja van den Berg, MD, and Henry Weinstein, MD, PhD (Alzheimer Center, Amsterdam); Lilian Vroegindeweij, MD (van Weel-Bethesda Ziekenhuis, Dirksland).

ABIDE study group

Amsterdam, the Netherlands (Alzheimer Center and Department of Neurology, Amsterdam Neuroscience, VU University Medical Center): Wiesje M. van der Flier, PhD, Philip Scheltens, MD, PhD, Femke H. Bouwman, MD, PhD, Marissa D. Zwan, PhD, Ingrid S. van Maurik, MSc, Arno de Wilde, MD, Wiesje Pelkmans, MSc, Colin Groot, MSc, Ellen Dicks, MSc, Els Dekkers (Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Amsterdam Neuroscience, VU University Medical Center), Bart N.M. van Berckel, MD, PhD, Frederik Barkhof, MD, PhD, Mike P. Wattjes, MD, PhD (Neurochemistry laboratory, Department of Clinical Chemistry, Amsterdam Neuroscience, VU University Medical Center), Charlotte E. Teunissen, PhD, Eline A. Willemse, MSc (Department of Medical Psychology, University of Amsterdam, Academic Medical Center) Ellen M. Smets, PhD, Marleen Kunneman, PhD, Sanne Schepers, MSc (BV Cyclotron), E. van Lier, MSc; Haarlem, the Netherlands (Spaarne Gasthuis): Niki M. Schoonenboom, MD, PhD; Utrecht, the Netherlands (Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery, Brain Center Rudolf Magnus, University Medical Center Utrecht): Geert Jan Biessels, MD, PhD, Jurre H. Verwer, MSc (Department of Geriatrics, University Medical Center Utrecht), Dieneke H. Koek, MD, PhD (Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine), Monique G. Hobbelink, MD (Vilans Centre of Expertise in Long-Term Care), Mirella M. Minkman, PhD, Cynthia S. Hofman, PhD, Ruth Pel, MSc; Meppel, the Netherlands (Espria): Esther Kuiper, MSc; Berlin, Germany (Piramal Imaging GmbH): Andrew Stephens, MD, PhD; Rotrkreuz, Switzerland (Roche Diagnostics International Ltd.): Richard Bartra-Utermann, MD.

Memory clinic panel

The members of the memory clinic panel are as follows: Niki M. Schoonenboom, MD, PhD (Spaarne Gasthuis, Haarlem); Barbera van Harten, MD, PhD, Niek Verwey, MD, PhD, and Peter van Walderveen, MD (Medisch Centrum Leeuwarden, Leeuwarden); Ester Korf, MD, PhD (Admiraal de Ruyter Ziekenhuis, Vlissingen); Gerwin Roks, MD, PhD (Sint Elisabeth Ziekenhuis, Tilburg); Bertjan Kerklaan, MD, PhD (Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis, Amsterdam); Leo Boelaarts, MD (Medisch Centrum Alkmaar, Alkmaar); Annelies. W.E. Weverling, MD (Diaconessenhuis, Leiden); Rob J. van Marum, MD, PhD (Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, ’s-Hertogenbosch); Jules J. Claus, MD, PhD (Tergooi Ziekenhuis, Hilversum); Koos Keizer, MD, PhD (Catherina Ziekenhuis, Eindhoven).

References

- 1.McKhann G.M., Knopman D.S., Chertkow H., Hyman B.T., Jack C.R., Jr., Kawas C.H. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts J.S., Karlawish J.H., Uhlmann W.R., Petersen R.C., Green R.C. Mild cognitive impairment in clinical care: a survey of American Academy of Neurology members. Neurology. 2010;75:425–431. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181eb5872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Werner P., Karnieli-Miller O., Eidelman S. Current knowledge and future directions about the disclosure of dementia: a systematic review of the first decade of the 21st century. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:e74–e88. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gulbrandsen P., Clayman M.L., Beach M.C., Han P.K., Boss E.F., Ofstad E.H. Shared decision-making as an existential journey: aiming for restored autonomous capacity. Patient Educ Couns. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joosten-Weyn Banningh L., Vernooij-Dassen M., Rikkert M.O., Teunisse J.P. Mild cognitive impairment: coping with an uncertain label. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:148–154. doi: 10.1002/gps.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petersen R.C. Mild cognitive impairment. Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn) 2016;22:404–418. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hargraves I., LeBlanc A., Shah N.D., Montori V.M. Shared decision making: the need for patient-clinician conversation, not just information. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:627–629. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunneman M., Montori V.M., Castaneda-Guarderas A., Hess E. What is shared decision making? (and what it is not) Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23:1320–1324. doi: 10.1111/acem.13065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stacey D., Legare F., Col N.F., Bennett C.L., Barry M.J., Eden K.B. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamann J., Bronner K., Margull J., Mendel R., Diehl-Schmid J., Buhner M. Patient participation in medical and social decisions in Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:2045–2052. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirschman K.B., Joyce C.M., James B.D., Xie S.X., Karlawish J.H. Do Alzheimer's disease patients want to participate in a treatment decision, and would their caregivers let them? Gerontologist. 2005;45:381–388. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karel M.J., Gurrera R.J., Hicken B., Moye J. Reasoning in the capacity to make medical decisions: the consideration of values. J Clin Ethics. 2010;21:58–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taghizadeh Larsson A., Osterholm J.H. How are decisions on care services for people with dementia made and experienced? A systematic review and qualitative synthesis of recent empirical findings. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26:1849–1862. doi: 10.1017/S104161021400132X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller L.M., Whitlatch C.J., Lyons K.S. Dementia; London, England: 2014. Shared decision-making in dementia: a review of patient and family carer involvement. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Wilde A, van Maurik IS, Kunneman M, et al. Alzheimer's Biomarkers In Daily Practice (ABIDE) project: rationale and design. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) (accepted). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Gerrity M.S., White K.P., DeVellis R.F., Dittus R.S. Physicians' reactions to uncertainty: refining the constructs and scales. Motiv Emot. 1995;19:175–191. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunneman M., Engelhardt E.G., ten Hove F.L., Marijnen C.A.M., Portielje J.E.A., Smets E.M. Deciding about (neo-)adjuvant rectal and breast cancer treatment: missed opportunities for shared decision making. Acta Oncol. 2016;55:134–139. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2015.1068447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Degner L.F., Sloan J.A., Venkatesh P. The Control Preferences Scale. Can J Nurs Res. 1997;29:21–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salkeld G., Solomon M., Short L., Butow P.N. A matter of trust–patient's views on decision-making in colorectal cancer. Health Expect. 2004;7:104–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2004.00257.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kriston L., Scholl I., Holzel L., Simon D., Loh A., Harter M. The 9-item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire (SDM-Q-9). Development and psychometric properties in a primary care sample. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Couet N., Desroches S., Robitaille H., Vaillancourt H., Leblanc A., Turcotte S. Assessments of the extent to which health-care providers involve patients in decision making: a systematic review of studies using the OPTION instrument. Health Expect. 2013 doi: 10.1111/hex.12054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stiggelbout A.M., van der Weijden T., De Wit M.P., Frosch D., Legare F., Montori V.M. Shared decision making: really putting patients at the centre of healthcare. BMJ. 2012;344:e256. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tarek M.E., Segers K., Van Nechel C. What Belgian neurologists and neuropsychiatrists tell their patients with Alzheimer disease and why: a national survey. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:33–37. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31817d5e4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clafferty R.A., Brown K.W., McCabe E. Under half of psychiatrists tell patients their diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. BMJ. 1998;317:603. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7158.603b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson H., Bouman W.P., Pinner G. On telling the truth in Alzheimer's disease: a pilot study of current practice and attitudes. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12:221–229. doi: 10.1017/s1041610200006347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fried T.R. Shared decision making—finding the sweet spot. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:104–106. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1510020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Portnoy D.B., Han P.K., Ferrer R.A., Klein W.M., Clauser S.B. Physicians' attitudes about communicating and managing scientific uncertainty differ by perceived ambiguity aversion of their patients. Health Expect. 2013;16:362–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00717.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simpkin A.L., Schwartzstein R.M. Tolerating uncertainty—the next medical revolution? N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1713–1715. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1606402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.IOM (Institute of Medicine) Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, D.C.2001.