Abstract

Introduction

Hearing loss (HL) is prevalent and independently related to cognitive decline and dementia. There has never been a randomized trial to test if HL treatment could reduce cognitive decline in older adults.

Methods

A 40-person (aged 70–84 years) pilot study in Washington County, MD, was conducted. Participants were randomized 1:1 to a best practices hearing or successful aging intervention and followed for 6 months. clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT02412254.

Results

The Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders Pilot (ACHIEVE-P) Study demonstrated feasibility in recruitment, retention, and implementation of interventions with no treatment-related adverse events. A clear efficacy signal of the hearing intervention was observed in perceived hearing handicap (mean of 0.11 to −1.29 standard deviation [SD] units; lower scores better) and memory (mean of −0.10 SD to 0.38 SD).

Discussion

ACHIEVE-P sets the stage for the full-scale ACHIEVE trial (N = 850, recruitment beginning November 2017), the first randomized trial to determine efficacy of a best practices hearing (vs. successful aging) intervention on reducing cognitive decline in older adults with HL.

Keywords: Clinical trials, Cognition, Dementia, Epidemiology, Hearing, Longitudinal study, Memory, Presbycusis

1. Introduction

Novel approaches are urgently needed to reduce risk of age-related cognitive decline, Alzheimer's disease (AD), and other dementias in older adults. In observational studies, hearing loss (HL) is independently associated with accelerated cognitive decline [1], [2] and incident dementia [3], [4]. Hypothesized mechanistic pathways underlying this association include effects of distorted peripheral encoding of sound on cognitive load, brain structure/function, and/or reduced social engagement [5]. Importantly, these pathways may be modifiable with comprehensive HL treatment. HL in older adults is prevalent, affecting nearly two of three adults aged more than 70 years [6], yet hearing aids remain grossly underutilized (<20% of adults with HL [7]). To date, there has never been a randomized trial to determine whether HL treatment could reduce cognitive decline and dementia in older adults. Here, we present the results of the Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders Pilot (ACHIEVE-P) Study, a randomized pilot study of 40 cognitively intact older adults nested within the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, primarily designed to test feasibility of a best practices hearing (vs. successful aging) intervention trial in older adults with audiometric HL, and secondarily, to explore an efficacy signal on 6-month proximal and cognitive outcomes. The 2013 Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional trials checklist [8] is included as Appendix 1.

2. Methods

2.1. Study objectives

The primary objective of this 40-person pilot study was to determine feasibility of recruitment, randomization procedures, retention, and the implementation of study interventions. Although the goal of the pilot study was not to formally test intervention efficacy, secondarily, we assessed for an early efficacy signal on proximal outcomes that may mediate downstream effects of hearing treatment on cognitive functioning and cognitive outcomes gathered 6 months after intervention.

2.2. Participants

ARIC is a prospective study of 15,792 men and women aged 45 to 64 years in 1987 to 1989 from four US communities. ACHIEVE-P participants were recruited from ARIC participants in Washington County, MD, and de novo from surrounding communities. Consistent with the parent study, transportation costs were covered for all participants.

Eligibility criteria included age 70 to 84 years, untreated adult onset bilateral HL (better-hearing ear three-frequency (0.5, 1, and 2 kHz) pure tone average [PTA] ≥30 and <70 decibels hearing level [dBHL]), community-dwelling, fluent English speaker, plans to remain in the area, and cognitively intact (Mini–Mental State Examination score ≥23 if high-school degree or less and ≥25 if some college degree or higher).

Exclusion criteria included dementia diagnosis, self-reported difficulty in two or more activities of daily living [9], medical contraindication to HL treatment, untreatable conductive HL, and unwillingness to regularly wear hearing aids.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and study procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board.

2.3. Best practices hearing intervention

Developed and manualized at the University of South Florida, the hearing intervention consists of evidence-based best practices to address participant's audiological and lifestyle needs. Training for the study audiologist consisted of 2-day onsite training before study start, as well as data monitoring and a site visit for quality assurance.

After baseline and randomization, participants met with the study audiologist for four 1-hour sessions over a period of 10 to 12 weeks. At the first visit, participants' hearing needs were assessed using the Client Oriented Scale of Improvement [10]. Participants received bilateral receiver-in-the-canal hearing aids fit to prescriptive targets using real-ear measures. At each subsequent visit, hearing aids were adjusted to targets and/or needs. Participants were offered assistive listening devices that were paired with their hearing aids (e.g., devices to stream cell phones and television, remote microphones to directly access other speakers in difficult listening environments). Rehabilitative counseling was provided to manage expectations and optimize technology use in real-world settings.

2.4. Successful aging intervention

The successful aging control intervention followed the protocol and materials developed for the 10 Keys to Healthy Aging [11], an evidence-based, interactive health education program for older adults on topics relevant to chronic disease and disability prevention, that was previously implemented in the Aging Successfully with Pain randomized study [12]. Training for the research nurse consisted of online certification and half-day onsite training before study start.

After baseline and randomization, participants met individually with a research nurse certified to administer the program for four 1-hour visits over a period of 10 to 12 weeks; each session focused on a “Key” chosen by the participant.

2.5. Randomization

Randomization procedures were designed and implemented by the study's Data Coordinating Center at the University of North Carolina. Participants were randomized 1:1 to the best practices hearing or successful aging intervention in blocks within strata defined by HL severity in the better-hearing ear, mild (PTA ≥30 and <40 dB), or moderate (PTA ≥40 and <70 dB); field center staff were masked to block size.

2.6. Study outcomes

The Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly (screening version) [13] measures perceived hearing handicap. The 12-item Cohen Social Network Index [14] assesses participation in different types of social relationships (e.g., spouse, family, friends, and religious groups). The 20-item University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale measures subjective feelings of loneliness and social isolation [15]. Depressive symptomatology was measured using the 11-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale [16]. Social, mental, and physical functions were assessed using the Short Form 12 questionnaire [17].

A detailed neurocognitive battery [2], [18] (Table 1) was administered at baseline and 6-months. All measures were administered face-to-face in a quiet room by a certified technician. A standardized protocol was followed to assess participant ability to understand speech in a quiet room to avoid confounding because of inaudibility.

Table 1.

Baseline and 6-month proximal outcomes and cognitive test/domain scores (means, standard deviations)∗ by intervention assignment, Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders Pilot Study, Washington County, MD, N = 40

| Outcomes | Hearing intervention (N = 20) |

Successful aging intervention (N = 20) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (N = 20) | 6-mo (N = 20) | Difference (N = 20) | Baseline (N = 20) | 6-mo (N = 19) | Difference (N = 19) | |

| Proximal outcomes (standardized scores) | ||||||

| Perceived hearing handicap† | 0.11 (1.02) | −1.29 (0.27) | −1.40 (0.96)‡ | −0.10 (1.02) | −0.08 (0.98) | 0.02 (0.68) |

| Loneliness† | 0.27 (1.06) | 0.07 (1.04) | −0.19 (0.87) | −0.29 (0.90) | −0.07 (1.30) | 0.22 (0.94) |

| Depression† | 0.28 (1.17) | 0.23 (1.00) | −0.05 (0.81) | −0.25 (0.72) | −0.25 (0.88) | 0.00 (0.58) |

| Social Network§ | ||||||

| Number of people | −0.21 (0.93) | −0.06 (0.64) | 0.15 (0.74) | 0.25 (1.06) | 0.13 (1.18) | −0.12 (0.70) |

| Diversity | −0.27 (0.75) | −0.10 (0.48) | 0.17 (0.65) | 0.33 (1.16) | −0.09 (1.22) | −0.42 (0.66)¶ |

| Social function | −0.18 (1.14) | −0.18 (1.08) | 0.00 (0.65) | 0.16 (0.83) | −0.10 (1.07) | −0.26 (0.91) |

| Mental function | −0.26 (1.07) | 0.00 (0.87) | 0.26 (0.80) | 0.25 (0.89) | 0.11 (0.90) | −0.14 (0.60) |

| Physical function | −0.08 (0.98) | 0.04 (0.95) | 0.11 (0.76) | 0.00 (1.06) | −0.08 (1.11) | −0.07 (0.40) |

| Cognitive tests (raw scores) | ||||||

| Memory | ||||||

| Delayed word recall | 5.6 (1.6) | 6.1 (1.5) | 0.5 (1.2) | 5.8 (1.9) | 6.8 (2.1) | 1.1 (1.6)¶ |

| Logical memory A | 10.5 (3.6) | 13.2 (3.8) | 2.7 (2.9)‡ | 12.2 (3.1) | 12.9 (2.1) | 0.7 (2.5) |

| Incidental learning | 3.5 (2.2) | 4.3 (2.2) | 0.8 (2.3) | 3.9 (1.7) | 4.1 (2.4) | 0.1 (1.9) |

| Language | ||||||

| Word fluency (F, A, S) | 33.7 (12.3) | 33.6 (13.8) | −0.1 (6.3) | 28.9 (12.3) | 29.3 (11.6) | 0.4 (5.1) |

| Boston Naming Test | 26.7 (2.5) | 27.2 (2.5) | 0.5 (1.4) | 26.6 (4.0) | 26.4 (4.1) | −0.1 (1.7) |

| Speed of processing/executive attention | ||||||

| Trail Making Test A† | 33 (29, 49.5) | 33 (27.5, 42) | −3 (−7.5, 2) | 40 (31.5, 53) | 38 (33, 44) | −1 (−8, 5) |

| Trail Making Test B† | 98 (73, 109.5) | 99.5 (69.5, 118.5) | 5.5 (−13.5, 25.5) | 140.5 (81, 209.5) | 96 (80, 172) | −16 (−34, 14) |

| Digit Symbol Substitution Test | 40.2 (10.2) | 40.8 (11.5) | 0.6 (5.6) | 38.8 (8.9) | 40.0 (9.8) | 1.2 (6.1) |

| Cognitive domains (standardized scores) | ||||||

| Memory | −0.10 (0.99) | 0.38 (0.80) | 0.48 (0.69)¶ | 0.24 (0.84) | 0.43 (0.61) | 0.19 (0.66) |

| Language | 0.15 (0.89) | 0.19 (0.83) | 0.05 (0.38) | −0.11 (1.12) | −0.11 (0.97) | 0.00 (0.42) |

| Executive function | 0.19 (1.02) | 0.22 (0.97) | 0.03 (0.42) | −0.14 (0.96) | 0.03 (0.92) | 0.17 (0.47) |

| Global function | 0.11 (1.04) | 0.27 (0.76) | 0.16 (0.42) | −0.02 (0.91) | 0.12 (0.67) | 0.14 (0.39) |

All scores are summarized as mean (standard deviation) except for the Trail Making Test Part A and the Trail Making Test Part B, which are summarized as median (25th–75th percentiles).

Lower scores are better.

Wilcoxon signed ranks test P value <.001.

Because the social network index was not developed to measure change over short periods of time, questions were adapted from asking about interaction “at least once every 2 weeks” to ask about frequency of interactions “over the past 2 weeks.”

Wilcoxon signed ranks test P value <.01.

To facilitate comparisons, all proximal outcomes were standardized to z-scores. Consistent with previous work [2], standardized cognitive test scores were used to create summary cognitive domain scores in memory, language, and speed of processing/executive attention. A global composite score was created by averaging the three domain-specific z-scores, scaled so that one unit equaled one standard deviation (SD) of that score.

2.7. Statistical analysis

We compared distributions of various characteristics at baseline for meaningful differences between arms. In exploratory analysis, baseline and 6-month proximal and cognitive outcomes were compared within each intervention group using a Wilcoxon signed ranks test; P values are reported only as a guide regarding which outcomes the intervention may possibly impact in the larger study.

3. Results

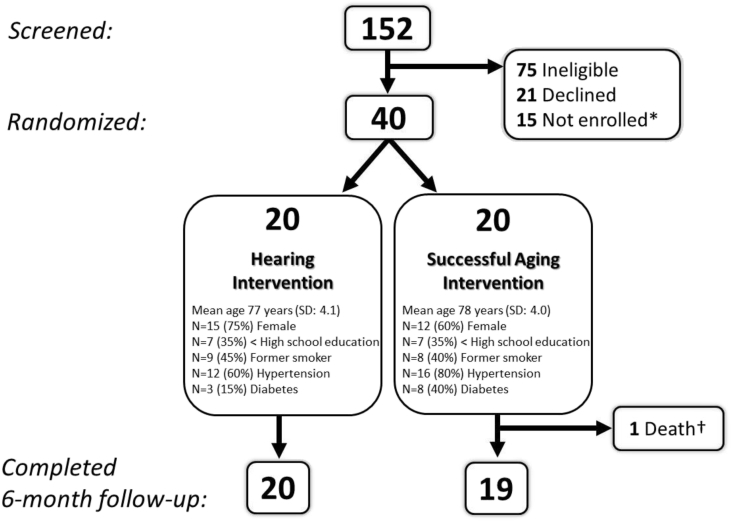

A total of 152 individuals were screened for eligibility, most from the parent study, ARIC (N = 131, 86%). Of those, 75 (49%) were ineligible, 21 (14%) declined participation, 40 were enrolled (N = 27, 68%, from ARIC), and 15 were not enrolled because recruitment targets had been reached (Fig. 1). Recruitment was completed in 12 weeks. The baseline and follow-up clinic visits were completed by almost all participants; one participant randomized to the Successful Aging group did not complete the 6-month follow-up visit because of death (unrelated to study intervention).

Fig. 1.

Participant eligibility, randomization and follow-up, ACHIEVE-Pilot Study, Washington County, MD, N = 40. ∗Eligible but not enrolled because recruitment targets had been reached. †Unrelated to study intervention. Abbreviation: ACHIEVE, Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders.

Both interventions were well tolerated and no treatment-related adverse events were reported. All hearing intervention participants completed all intervention visits (four visits per participant, 80 total visits conducted by the study audiologist). Nineteen of Successful Aging intervention participants completed all intervention visits (four visits per participant). One participant missed one visit because of death; 79 total visits were therefore conducted by the research nurse. In the hearing intervention group, average daily hearing aid use, measured through objective data logged by the hearing aid, was 9.8 hours (SD 6.1), 9.2 hours (SD 3.6), and 9.7 hours (SD 3.8) at the three hearing intervention visits following the visit in which hearing aids were fit, respectively (range 1.8–23 hours).

Distributions of baseline characteristics by the treatment group are shown in Fig. 1. The mean three-frequency PTA for participants in the hearing intervention group was 44 dBHL (SD 6; range 33–53) compared with 47 dBHL (SD 10; range 36–73) in the successful aging group.

Estimated changes in standardized proximal outcomes were qualitatively different by intervention assignment for all measures (Table 1). For participants in the hearing intervention group, estimates of 6-month change in proximal outcomes are consistent with improvement or no change, with the greatest improvement observed in perceived hearing handicap; 0.11 SD (95% confidence interval [CI] −0.37, 0.59) at baseline to −1.29 SD (95% CI −1.41, −1.16) at 6 months (lower scores are better). In contrast, estimates of 6-month change for successful aging participants are consistent with no change or worse function; diversity of social network decreased from 0.33 SD (95% CI −0.23, 0.89) to −0.09 SD (95% CI −0.68, 0.50) in this group.

Consistent with practice effects, mean cognitive test scores were generally higher at 6 months than baseline for both intervention groups, with greatest change observed on a test of delayed memory [19] for the successful aging group (5.8 to 6.8 words recalled) and on the logical memory test [20] for the hearing intervention group (10.5 to 13.2 elements recalled) (Table 1). The greatest estimated improvement in cognitive domain score was in memory in the hearing intervention group (−0.10 SD to 0.38 SD).

4. Discussion

In this pilot study, we demonstrated feasibility of recruitment, retention, and intervention delivery in a randomized trial of HL treatment nested within an observational cohort study. Recruitment goals were met within 12 weeks, and study interventions were well tolerated with good compliance. Nesting of this study in a well-characterized, prospective observational study allowed us to work with experienced, dedicated staff and capitalize on well-established protocols and study staff-participant relationships to maximize operational efficiency and meet ambitious study goals. All participants completed the study, excluding one who died for reasons unrelated to the study intervention. By design, participants in this study are older so as to be at risk for cognitive decline during the study period. Death and attrition are therefore important possible threats to the internal validity of the full-scale 3-year ACHIEVE trial and will be considered in both the design and analysis of that study.

In secondary analyses, we explored an intervention efficacy signal on proximal and cognitive outcomes. The direction of estimated effects of the hearing intervention on these outcomes, including perceived handicap, loneliness, and social network diversity, was consistent with a priori hypotheses that motivated the design of this trial. We did not observe as clear of an efficacy signal in 6-month cognitive outcomes, consistent with the hypothesis that hearing treatment will take longer (>1 year) to impact cognition. Given limitations of this pilot study, however, including small sample size, the magnitude of the effects reported here should not be interpreted as that would be estimated in a fully powered trial [21].

This study sets the stage for the full-scale, National Institute on Aging–funded ACHIEVE trial (N = 850, recruitment anticipated to begin November 2017). ACHIEVE will be the first randomized controlled trial to test the efficacy of a best practices hearing (vs. successful aging) intervention on reducing cognitive decline in older adults with HL.

Research in Context.

-

1.

Systematic review: Literature review included traditional sources (e.g., PubMed). Relevant citations are appropriately cited. In observational studies, hearing loss (HL) is independently associated with accelerated cognitive decline. Hypothesized mechanistic pathways underlying this association—cognitive load, brain structure/function, and/or reduced social engagement—are potentially modifiable through HL treatment. To date, however, there has never been a randomized study of the effect of a hearing intervention on delaying cognitive decline in older adults.

-

2.

Interpretation: Consistent with previous observational data, our findings suggest a positive effect of HL treatment on change in cognitive performance, especially memory, for more than 6 months, and with proximal factors that may mediate a relationship between hearing and cognition (e.g., social network diversity, communication).

-

3.

Future directions: A fully powered definitive randomized trial (N = 850, 3 years follow-up) is needed to determine efficacy of a best practices hearing (vs. successful aging) intervention on reducing cognitive decline in older adults with HL.

Acknowledgments

The Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders Pilot (ACHIEVE-P) Study was supported by National Institute on Aging 1R34AG046548-01A1 and the Eleanor Schwartz Charitable Foundation. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (ARIC) is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts (HHSN268201100005C, HHSN268201100006C, HHSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C, and HHSN268201100012C). Neurocognitive data are collected by U01 HL096812, HL096814, HL096899, HL096902, HL096917, with previous brain magnetic resonance imaging examinations funded by R01-HL70825 and additional support from the National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

References

- 1.Lin F.R., Yaffe K., Xia J., Xue Q.L., Harris T.B., Purchase-Helzner E. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:293–299. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deal J.A., Sharrett A.R., Albert M.S., Coresh J., Mosley T.H., Knopman D. Hearing impairment and cognitive decline: a pilot study conducted within the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181:680–690. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin F.R., Metter E.J., O'Brien R.J., Resnick S.M., Zonderman A.B., Ferrucci L. Hearing loss and incident dementia. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:214–220. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deal J.A., Betz J., Yaffe K., Harris T., Purchase-Helzner E., Satterfield S. Hearing impairment and incident dementia and cognitive decline in older adults: the Health ABC study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72:703–709. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin F.R., Albert M. Hearing loss and dementia—who is listening? Aging Ment Health. 2014;18:671–673. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.915924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin F.R., Thorpe R., Gordon-Salant S., Ferrucci L. Hearing loss prevalence and risk factors among older adults in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:582–590. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chien W., Lin F.R. Prevalence of hearing aid use among older adults in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:292–293. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan A.W., Tetzlaff J.M., Altman D.G., Laupacis A., Gøtzsche P.C., Krleža-Jerić K. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:200–207. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz S., Ford A.B., Moskowitz R.W., Jackson B.A., Jaffe M.W. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dillon H., James A., Ginis J. Client oriented scale of improvement (COSI) and its relationship to several other measures of benefit and satisfaction provided by hearing aids. J Am Acad Audiol. 1997;8:27–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newman A.B., Bayles C.M., Milas C.N., McTigue K., Williams K., Robare J.F. The 10 Keys to Healthy Aging: findings from an innovative prevention program in the community. J Aging Health. 2010;22:547–566. doi: 10.1177/0898264310363772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morone N.E., Greco C.M., Rollman B.L., Moore C.G., Lane B., Morrow L. The design and methods of the aging successfully with pain study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ventry I.M., Weinstein B.E. Identification of elderly people with hearing problems. ASHA. 1983;25:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen S., Doyle W.J., Skoner D.P., Rabin B.S., Gwaltney J.M., Jr. Social ties and susceptibility to the common cold. JAMA. 1997;277:1940–1944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russell D., Peplau L.A., Ferguson M.L. Developing a measure of loneliness. J Pers Assess. 1978;42:290–294. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4203_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohout F.J., Berkman L.F., Evans D.A., Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D (center for epidemiological studies depression) depression symptoms index. J Aging Health. 1993;5:179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ware J., Jr., Kosinski M., Keller S.D. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rawlings A.M., Bandeen-Roche K., Gross A.L., Gottesman R.F., Coker L.H., Penman A.D. Factor structure of the ARIC-NCS neuropsychological battery: an evaluation of invariance across vascular factors and demographic characteristics. Psychol Assess. 2016;28:1674–1683. doi: 10.1037/pas0000293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knopman D.S., Ryberg S. A verbal memory test with high predictive accuracy for dementia of the Alzheimer type. Arch Neurol. 1989;46:141–145. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520380041011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wechsler D. A standardized memory scale for clinical use. J Psychol. 1945;19:87–95. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leon A.C., Davis L.L., Kraemer H.C. The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:626–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]