Abstract

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most prevalent and aggressive malignancies worldwide. Studies seeking to advance the overall understanding of lncRNA profiling in HCC remain rare.

Methods

The transcriptomic profiling of 12 HCC tissues and paired adjacent normal tissues was determined using high-throughput RNA sequencing. Fifty differentially expressed mRNAs (DEGs) and lncRNAs (DELs) were validated in 21 paired HCC tissues via quantitative real-time PCR. The correlation between the expression of DELs and various clinicopathological characteristics was analyzed using Student’s t-test or linear regression. Co-expression networks between DEGs and DELs were constructed through Pearson correlation co-efficient and enrichment analysis. Validation of DELs’ functions including proliferation and migration was performed via loss-of-function RNAi assays.

Results

In this study, we identified 439 DEGs and 214 DELs, respectively, in HCC. Furthermore, we revealed that multiple DELs, including NONHSAT003823, NONHSAT056213, NONHSAT015386 and especially NONHSAT122051, were remarkably correlated with tumor cell differentiation, portal vein tumor thrombosis, and serum or tissue alpha fetoprotein levels. In addition, the co-expression network analysis between DEGs and DELs showed that DELs were involved with metabolic, cell cycle, chemical carcinogenesis, and complement and coagulation cascade-related pathways. The silencing of the endogenous level of NONHSAT122051 or NONHSAT003826 could significantly attenuate the mobility of both SK-HEP-1 and SMMC-7721 HCC cells.

Conclusion

These findings not only add knowledge to the understanding of genome-wide transcriptional evaluation of HCC but also provide promising targets for the future diagnosis and treatment of HCC.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Long non-coding RNA, RNA sequencing, Co-expression network, Cell migration

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most prevalent and aggressive malignancies worldwide [1], with incidence rates continuing to increase rapidly [2]. As a multistage progress, HCC typically arises from cirrhotic livers and is usually associated with viral hepatitis (hepatitis B and C viruses), foodstuffs contaminated with aflatoxin B1 (AFB1), alcohol abuse, and obesity [3]. Hepatocarcinogenesis is a complex progress, the initiation, promotion and progression of which is often involved with an accumulation of genetic and epigenetic changes [4]. In spite of the discovery and progression of the underlying molecular mechanisms of HCC, the current death rates continue to increase [2, 5].

Recently, growing evidence has suggested that long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), defined as transcripts larger than 200 nucleotides in length without evident protein coding functions, are capable of influencing multiple biological process through various mechanisms as guides, scaffolds, and decoys [6–8]. Moreover, reports have revealed that lncRNAs also have played a key role in gene regulation in cancer, affecting various aspects including proliferation, survival, migration or genomic stability [9–11]. Especially in HCC, several lncRNAs including highly up-regulated in liver cancer (HULC) [12], high expression in HCC (HEIH) [13], lncRNA associated with microvascular invasion in HCC (MVIH) [14], lncRNA metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT-1) [15], maternally expressed gene-3 (MEG3) [16] and H19 [17], are usually deregulated and act as important regulators of cancer progression, providing potential biomarkers and candidate therapeutic targets for HCC diagnosis and treatment. Nevertheless, knowledge on the systematic profiling and characterization of HCC transcriptome (lncRNAs in particular) remains far from adequate.

In this study, with the application of RNA high-throughput sequencing (RNA-seq), we sequenced the transcriptome of 24 matched tissue samples (primary tumor and paired adjacent normal tissues) from 12 Chinese HCC patients, and validated the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and lncRNAs (DELs) in 21 pairs of HCC tissue samples using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). Next, we analyzed the association between DELs and clinicopathological characteristics, and found several lncRNAs that might serve as biomarkers of diagnosis and prognosis in HCC patients. Furthermore, the co-expression network between DEGs and DELs was applied to predict the potential functional and regulatory mechanisms of lncRNAs in HCC, and the possible functions of lncRNAs on HCC cells were experimentally validated.

Findings

Patients’ information and tissue collection

Tissue samples of fresh-frozen human primary hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and paired adjacent normal liver tissues (3 cm away from tumor) were collected from 24 Chinese patients undergoing surgery from October 2012 to October 2013 at the Department of Surgical Oncology, the First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, China. The liver tissues were immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen after surgery, and stored at −80 °C until use. The diagnosis of HCC was histologically confirmed via pathological examinations by two independent pathologists, and all the HCC tissues were assessed by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Patients had no preoperative treatments. Twelve randomly selected paired samples (RNA-seq Set) were used for RNA sequencing as a discovery cohort, and 21 paired samples (Real-Time PCR Set, 9 were included in the RNA-seq Set) were used for qRT-PCR as a validation cohort. Clinicopathological features, including age, gender, HBV infection, tumor size, differentiation grade, serum α-fetoprotein (AFP) concentration, tissue immunohistochemical (IHC) staining status of AFP, and portal vein tumor thrombosis (PVTT) are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of the patients included in this study

| RNA-seq Set | Real-Time PCR Set | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median Age at Surgery (Range) | 55(35–70) | 55(35–74) | 56(35–74) |

| ≤50 | 5 | 9 | 9 |

| >50 | 7 | 12 | 15 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 8 | 18 | 18 |

| Female | 4 | 3 | 6 |

| HBsAg(+/−) | |||

| – | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| + | 10 | 18 | 20 |

| Serum AFP (ng/ml) | |||

| ≤20 | 6 | 11 | 12 |

| >20 | 6 | 10 | 12 |

| Tumor Size (cm) | |||

| ≤5 | 10 | 14 | 17 |

| >5 | 2 | 7 | 7 |

| Tumor Differentiation | |||

| Well/Moderate | 7 | 11 | 13 |

| Poor | 5 | 10 | 11 |

| PVTT | |||

| – | 8 | 15 | 17 |

| + | 4 | 6 | 7 |

| IHC staining of AFP | |||

| – | 4 | 9 | 10 |

| + | 8 | 12 | 14 |

| Total Number of patients | 12 | 21a | 24 |

a9 patients in the RNA-seq Set were included. HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen, AFP alpha-fetoprotein, PVTT portal vein tumor thrombosis, IHC immunohistochemistry

RNA-seq profiling of 12 HCC samples with paired adjacent normal liver tissues

To systematically identify the transcriptome of HCC, we performed RNA-seq on 12 HCC samples with paired adjacent normal liver tissues using Illumina Hiseq2500. Approximately 5.4 billion paired raw reads and 5.2 billion paired clean reads were generated for all 12 patients (average 45.2 million raw reads and 43 million clean reads each). After alignment, an average of 60 million reads mapped to human genome were acquired for each paired sample, accounting for 69.9% of the total clean reads. Specifically, the total of mapped annotated genes or long-noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) was 53.6 million and 35.5 million (62.4% and 41.7%), respectively, for each patient.

Identification of differentially expressed genes in HCC

After aligning all the reads to the human genome reference consortium GRCh37, we identified a total of 31,237 transcripts, including 29,427 transcripts in HCC tissues (T) and 29,280 in the paired adjacent normal tissues (N). Unsupervised Principal Components Analysis (PCA) of mRNAs demonstrated that HCC tissue samples can be distinctively separated from adjacent normal tissue samples.

Furthermore, we identified as many as 439 statistically significant differentially expressed genes (DEGs), the fold change of which was greater than 2 or less than 1/2 between T and paired N in at least half of the samples sequenced. Generally, there were 139 up-regulated and 300 down-regulated DEGs in HCC. The heat map of DEGs via hierarchical clustering analysis was generated and is displayed in Fig. 1a. Particularly, we noticed that only one gene named CENPF was up-regulated in all 12 pairs, while 12 genes including CFP, FOS, MT1 family, and NAT2 were down-regulated in all samples.

Fig. 1.

Expression differences and enrichment analysis of mRNAs in HCC tumor vs. paired adjacent normal tissues. a Hierarchical clustering analysis of 439 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between 12 HCC tumor and paired adjacent normal tissue samples (log2-fold change >2 or <−2 and P < 0.05). Columns represent each gene, and rows represent each patient. The relative expression levels of mRNAs are depicted into color scale ranging from green (down-regulation) to red (up-regulation). b Real-time PCR validation of 25 DEGs in 21 HCC tumor and paired adjacent normal tissue samples, and 22 DEGs of statistical significance are presented in a box diagram (P < 0.05) with median bar indicated inside. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) is used as a reference gene. c Pie charts of the top ten KEGG pathways of 439 DEGs enriched by DAVID. d Pie charts of top ten GO terms for biological process. e Pie charts of the top ten terms for genetic associated diseases

To better understand the enrichment of DEGs, we applied the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) [18, 19] to analyze the distribution of DEGs through KEGG pathways, Gene Oncology (GO) and Genetic associated Disease database. Among the top 10 enriched KEGG pathways, most were related to metabolism except for the cell cycle and p53 signaling pathway, which were closely associated with tumor growth and development (Fig. 1c). We randomly selected 25 DEGs (15 down-regulated and 10 up-regulated) among the top enriched KEGG pathway terms, and validated their expression in 21 paired HCC tissues via qRT-PCR. As displayed in Fig. 1b, 22 DEGs (88%) were significantly dysregulated, 15 down-regulated and 7 up-regulated, in HCC. For GO, most were cell cycle related in the top 10 enriched terms, as well as terms involving oxidation reduction, proteolysis and response to wounding (Fig. 1d). In those terms related to disease, the metabolic related gene set was the most enriched term, while cancer related terms ranked third (Fig. 1e).

Identification of novel differentially expressed lncRNAs in HCC

By aligning the transcript reads to human ncrna_NONCODEv4 [20], we obtained a total of 71,106 (accounting for 77%) transcripts, including 65,302 in T and 65,433 in N. Similarly, by the same criteria as DEGs, we identified 214 differentially expressed lncRNA (DELs) transcripts in HCC, with 90 up-regulated and 104 down-regulated (Fig. 2a), much less than the number of DEGs (439). This finding is also consistent with previous reports showing that lncRNAs display higher expression variation than mRNAs [21]. We noted that the expression of four lncRNA transcripts, namely, NONHSAT001093, NONHSAT065819, NONHSAT142698, and NONHSAT142707, were down-regulated in all 12 patients, while the expression levels of NONHSAT056213, NONHSAT091576 and NONHSAT122271 were elevated in 10 out of 12 patients.

Fig. 2.

Expression differences of lncRNAs in HCC tumor vs. paired adjacent normal tissue samples. a Hierarchical clustering analysis of 214 differentially expressed lncRNAs (DELs) in HCC tumor samples. b Real-time PCR validation of 25 DELs in 21 HCC paired samples, and 17 of statistical significance are presented in box diagrams (P < 0.05). Beta-actin served as an internal control

We randomly selected 25 DELs (16 down-regulated and 9 up-regulated), and verified their expression using qRT-PCR. As depicted in Fig. 2b, 17 DELs (68%) displayed significant dysregulation, 11 of which were down-regulated and 6 of which were up-regulated in HCC tissues. Meanwhile, we cross-referenced the expression profiles of these 25 DELs in TCGA database containing 200 HCC tissue samples and 50 normal control samples (TCGA Liver hepatocellular carcinoma, LIHC) from TANRIC [22], and found that 16 out of 17 DELs were consistent with our qRT-PCR results.

Clinical relevance of novel DELs in HCC

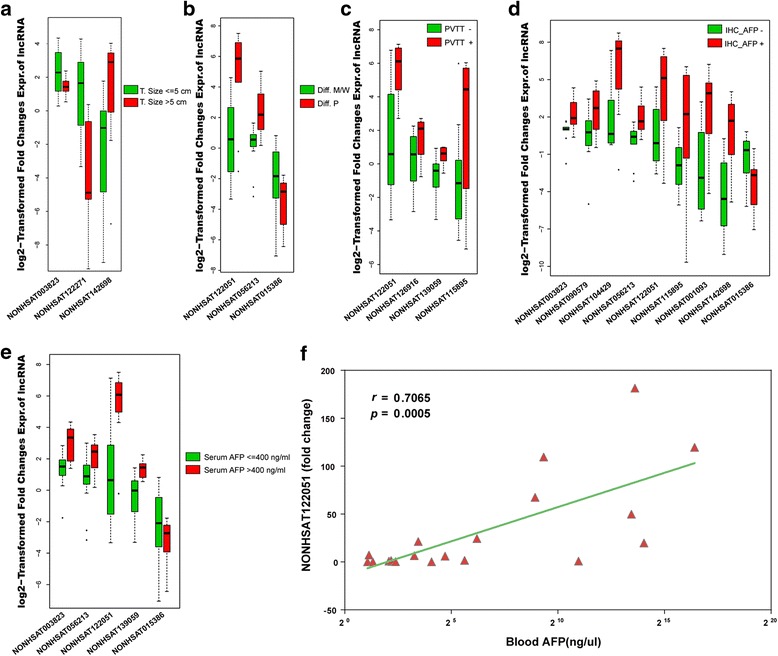

To further explore the association between DELs and clinicopathological characteristics of the HCC patients, we analyzed the expression profiles of 25 selective DELs based on the results of qRT-PCR. As presented in Fig. 3a, the expression levels of NONHSAT003823, NONHSAT122271 and NONHSAT142698 were significantly correlated with tumor size. Regarding tumor histologic differentiation, NONHSAT122051 and NONHSAT056213 were associated with poor differentiation, while NONHSAT015386 was up-regulated in well/ moderate differentiation grade (Fig. 3b). In contrast, NONHSAT122051, NONHSAT126916, NONHSAT139059 and NONHSAT115895 were positively correlated with portal vein tumor thrombosis (PVTT, Fig. 3c). It is of note that the expression levels of NONHSAT003823, NONHSAT056213, NONHSAT122051 and NONHSAT015386 were remarkably correlated with both the serum concentration and the tissue immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of α-fetoprotein (AFP) (Fig. 3d, e). Specifically, the expression level of NONHSAT122051 was linearly correlated with the serum AFP concentration with the p value of 0.0005 (Fig. 3f), suggesting that NONHSAT122051 may serve as a novel biomarker candidate for HCC.

Fig. 3.

Correlation analysis of DELs with clinicopathologic characteristics of HCC. a The relative expression of DELs in 14 HCC patients with tumor size no larger than 5 cm vs. 7 patients with tumor size greater than 5 cm. The expression levels of DELs are normalized by the paired adjacent normal samples as fold changes and log2 transformed (P < 0.05, similarly hereinafter). b The relative expression of DELs in 11 patients with tumor histologic differentiation grade of well (W) or moderate (M) vs 10 with poor (P) differentiation grade. c The relative expression of DELs in 15 patients without portal vein tumor thrombosis (PVTT) and 6 patients with PVTT. d The relative expression of DELs in 9 HCC patients with negative immunohistochemistry staining of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) in tumor tissues and 12 with positive staining. e The relative expression of DELs in 14 HCC patients with serum AFP level no more than 400 ng/ml, and 7 with more than 400 ng/ml. f The linear analysis of the relative expression of NONHSAT122051 and serum AFP concentration (r = 0.7065, P = 0.0005)

Co-expression network of DEGs and DELs in HCC

Because the biological functions of lncRNAs are largely unknown, we sought to explore potential functions by analyzing their co-expressed mRNA network. By analyzing the correlation between 439 DEGs and 214 DELs, we constructed a co-expression network containing a total of 2961 lncRNA-mRNA pairs, the absolute r value of which is above 0.8. Among these pairs, 262 were located on the same chromosome (cis-acting), accounting for only 8.8%. While most of these pairs (2698, 91.2%) were on the different chromosome (trans-acting), suggesting that most of the regulation of lncRNA and mRNA expression was in a trans way. These findings are also consistent with previous reports [23, 24].

Of the 2961 pairs, there were only 195 and 373 unique lncRNAs or mRNAs, respectively. Most of the lncRNAs (167, 85.6%) were differentially co-expressed with more than one mRNA. Likewise, 308 mRNA (82.6%) displayed a differential relationship with more than one lncRNA. Only 28 lncRNAs and 65 mRNAs showed single differential co-expression, suggesting that lncRNAs and mRNAs may tend to interact with each other in a complex network. Similar to the results of total DEGs enrichment, most of the enriched pathways involving the differentially co-expressed DEGs were metabolism related. The top enriched pathway, namely, metabolic pathways, contained 626 co-expression pairs, involving 55 DEGs and 119 DELs (Fig. 4a). It is noteworthy that cell cycle, chemical carcinogenesis, and complement and coagulation cascade-related pathways were listed within the top 10, containing 28, 59, and 58 DELs, respectively (Fig. 4b-d.), suggesting that these DELs may also play an important role during tumorigenesis and malignant progression.

Fig. 4.

The co-expression network between DEGs and DELs in HCC. a The co-expression network of metabolic pathway containing 626 connections between 119 DELs and 55 DEGs with absolute r value larger than 0.8. The orange boxes represent DEGs, and the blue hexagons represent the DELs. The edges between DEGs and DELs indicate the potential correlation, of which the color and the thickness standing for different correlation coefficient were marked within the frame. b The co-expression network of cell cycle pathway containing 52 connections between 28 DELs and 12 DEGs. c The co-expression network of chemical carcinogenesis pathway containing 113 connections between 59 DELs and 11 DEGs. d The co-expression network of complementary and coagulation cascades pathway containing 179 connections between 58 DELs and 10 DEGs

Functional validation of novel DELs in HCC

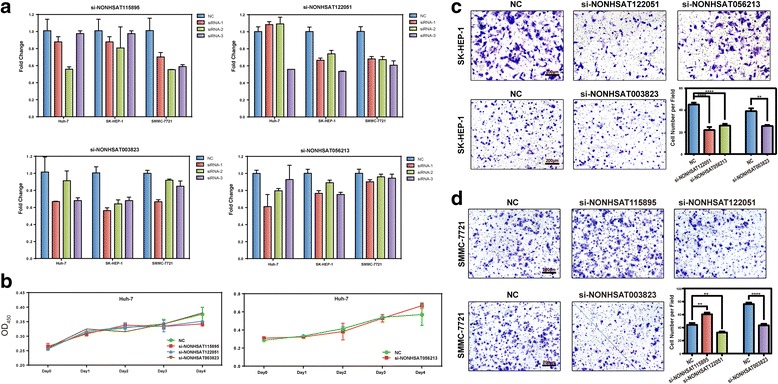

To investigate the potential biological functions of the DELs in HCC, loss-of-function assays were used by silencing the endogenous lncRNA levels in HCC cell lines via small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). Based on the knock-down effects (Fig. 5a), we transfected siRNA with the best efficiency into the HCC cell lines for each DEL. Despite little effect on the HCC cell proliferation (Fig. 5b), we did notice that they may have an impact on the cell migration ability. As shown in Fig. 5c, d, silencing the expression of NONHSAT122051 or NONHSAT003826 significantly attenuated the mobility of both SK-HEP-1 and SMMC-7721 HCC cells, indicating that they might play a potential pro-metastasis role in HCC development. In contrast, the knockdown of NONHSAT115895 remarkably promoted the migration of SMMC-7721, but the difference was of no statistical significance in SK-HEP-1, possibly due to the inefficient knock down (data not shown). Similarly, NONHSAT560213 could promote the migration of SK-HEP-1 cells, but no such significant difference was observed in SMMC-7721 (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

RNAi assay of candidate DELs regulating HCC cell proliferation and migration. a The relative expression levels of NONHSAT15985, NONHSAT122051, NONHSAT003823, and NONHSAT056213 in Huh-7, SK-HEP-1 or SMMC-7721 cells transfected with siRNAs or negative control (NC). b CCK-8 assay of Huh-7 cells transfected with siRNAs of NONHSAT115895, NONHSAT122051, NONHSAT003823, NONHSAT056213, or negative control (NC). Mean values are plotted as shown, and bars indicate SEM in triplet. c Transwell migration assays of SK-HEP-1 cells transfected with negative control (NC) or siRNAs for NONHSAT122051, NONHSAT056213, or NONHSAT003823. Representative images are shown, along with the quantification of five randomly selected fields. The values are depicted as the mean ± SEM; asterisks indicate significance. d Transwell migration assays of SMMC-7721 cells transfected with NC or siRNAs for NONHSAT115895, NONHSAT122051, or NONHSAT003823. Transwell assays were performed in triplicate, and the representative images are displayed

In recent transcriptomic studies, increasing evidence that long non-coding RNAs play a key regulatory role in gene regulation and chromatin remodeling has attracted more research attention. Despite accumulating evidence that lncRNA played an important role in cancers, the research on lncRNAs’ clinicopathological correlation with cancer, especially in HCC, are still far from adequate. It has been reported that the expression levels of CCAT1 [25], H19 [26], MEG3 [26], PANDAR [27], MALAT1 [28] and SPX [29] were significantly associated with serum AFP levels, while the expression levels of SPRY4-IT1 [30], SNHG1 [31], HNF1A-AS1 [32], HOTAIR [33], DDX5 [34] and GAS5 [35] were correlated with tumor differentiation. Moreover, GAS5, as well as SNHG3 [36], was also correlated with PVTT. A recent study using RNA-seq focused on the deregulated lncRNAs in HCC, especially with PVTT, identified multiple candidate lncRNAs for HCC tumorigenesis and metastasis, but failed to distinguish PVTT-specific lncRNAs from HCC tumor tissues [37]. In this study, we found that the up-regulation of NONHSAT056213, NONHSAT139059 and NONHSAT122051, as well as the down-regulation of NONHSAT015386 in HCC were positively correlated with the HCC clinicopathological features including poor tumor differentiation, PVTT, tissue or serum AFP levels. It is interesting to note that NONHSAT001093, NONHSAT115895 and NONSHAT142698 were down-regulated in HCC, but negatively correlated with tumor size, PVTT or AFP levels. Moreover, the expression of NONHSAT003823 was positively correlated with tissue or serum AFP levels, but negatively correlated with tumor size. The detailed biological functions and molecular regulation mechanisms of these DELs require further exploration.

Although research has indicated that lncRNAs are fine-tuners and key regulators in various aspects of cell transformation and metastasis especially in cancer, the exact functions of lncRNAs are not well understood [38–40]. To further functionally characterize lncRNAs, the analysis strategy named Guilt-By-Association (GBA) [41–43], which was originally derived from the strategy used for the data analysis of microarrays to identify gene sets sharing the similar features, was applied to construct a co-expression network of DELs and DEGs [44]. In our study, NONHSAT028824 were differentially co-expressed with 60 DEGs, most of which were metabolism related. We noticed that by genomic location there is a 588 bp overlap between NONHSAT028824 and apolipoprotein F (APOF), which may explain the high co-expression profiling (r = 0.9873). APOF is the protein component of apolipoproteins highly expressed restrictedly in liver [45], the aberrant expression of which would result in abnormality of lipid metabolism [46, 47], but its role in carcinogenesis remains unknown. In contrast, 3 out of 7 DEGs with the largest number of co-expressed DELs are members of complementary and coagulation cascades pathway (F11, C8A and C3P1). Recent reports indicate that the complement cascade facilitates oncogenesis and metastasis by sustaining proliferation, preventing apoptosis, promoting angiogenesis, invasion and migration, and suppressing antitumor immunity (reviewed in [48]). Similarly, the coagulation system can be activated by cancer cells and plays a role in tumor progression [49]. Our findings provide a novel thought on functional annotation of lncRNAs for future downstream experimental validation in HCC.

It is of particular note that NONHSAT122051 possibly serves as a novel promising biomarker for HCC. The loss-of-function experiment also demonstrated that NONHSAT122051 could significantly promote HCC cell migration. We noticed that the chromosome location of NONHSAT122051 overlaps with the coding gene paternally expressed 10 (PEG10), which could promote proliferation, migration and invasion in multiple cancer cells [50–52]. Furthermore, the abnormal expression of PEG10 is detected in various cancers [50, 53–56] including hepatocellular carcinoma [57]. It has been reported that the expression of lncRNAs is strikingly cell type-specific in normal tissues [58] and more cancer type-specific than protein coding genes [59]. Additionally, the relatively stable secondary structures of lncRNAs facilitates their detection as free RNAs, making them an ideal class of biomarkers for early detection, diagnosis and prognosis of cancers [9].

Due to the lack of sufficient tissue samples of HCC patients, we were unable to validate our findings in a larger cohort. The expression of about one-third (8, 32%) of DELs had no statistical significance between tumor and normal tissue samples. Nevertheless, resorting to the TCGA database in TANRIC, we found that a total of 21 DELs out of 25 displayed significantly differential expression in HCC, including 5 DELs failed in our qRT-PCR validation.

Conclusion

Taken together, we identified a number of DEGs and DELs in HCC and further analyzed the clinicopathological correlation, as well as the potential functions of DELs. Our current findings may shed light on the overall understanding of HCC-specific lncRNAs, providing novel targets for the diagnosis and treatment of HCC.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the members of our laboratory for their helpful discussion. We thank Ribobio (Guangzhou, China) for the RNAi experiment support.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81,272,354, 31,401,144).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they were used in the current research program, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AFB1

Aflatoxin B1

- AFP

Alpha-fetoprotein

- APOF

Apolipoprotein F

- DAVID

Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery

- DEG

Differentially expressed mRNA

- DEL

Differentially expressed lncRNA

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GBA

Guilt-By-Association

- GO

Gene Oncology

- H&E

Hematoxylin and eosin

- HBsAg

Hepatitis B surface antigen

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HEIH

High expression in HCC

- HULC

Highly up-regulated in liver cancer

- IHC

Immunohistochemical

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- lncRNA

Long non-coding RNA

- MALAT-1

Metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1

- MEG3

Maternally expressed gene-3

- MVIH

LncRNA associated with microvascular invasion in HCC

- PCA

Principal Components Analysis

- PEG10

Paternally expressed 10

- PVTT

Portal vein tumor thrombosis

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- RIN

RNA integrity number

- RNA-seq

RNA high-throughput sequencing

- siRNA

Small interfering RNAs

Authors’ contributions

The study was conceived, designed and coordinated by JY, MDL, LJL and FSW. LJW, HXY and QFW collected the clinical samples and clinicopathological data. SJN, JWZ and QZ performed the RNA sequencing and real-time PCR validation. XHM, LS and QYC analyzed data. JY and KKS performed the functional assays. All authors wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study and the usage of these tissue samples were approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, and all subjects in this study provided signed written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farazi PA, DePinho RA. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: from genes to environment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:674–687. doi: 10.1038/nrc1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aravalli RN, Steer CJ, Cressman EN. Molecular mechanisms of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2008;48:2047–2063. doi: 10.1002/hep.22580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maluccio M, Covey A. Recent progress in understanding, diagnosing, and treating hepatocellular carcinoma. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:394–399. doi: 10.3322/caac.21161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ponting CP, Oliver PL, Reik W. Evolution and functions of long noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2009;136:629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Mattick JS. Long non-coding RNAs: insights into functions. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:155–159. doi: 10.1038/nrg2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batista PJ, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNAs: cellular address codes in development and disease. Cell. 2013;152:1298–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huarte M. The emerging role of lncRNAs in cancer. Nat Med. 2015;21:1253–1261. doi: 10.1038/nm.3981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunner AL, Beck AH, Edris B, Sweeney RT, Zhu SX, Li R, Montgomery K, Varma S, Gilks T, Guo X, et al. Transcriptional profiling of long non-coding RNAs and novel transcribed regions across a diverse panel of archived human cancers. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R75. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-8-r75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibb EA, Brown CJ, Lam WL. The functional role of long non-coding RNA in human carcinomas. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:38. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Panzitt K, Tschernatsch MM, Guelly C, Moustafa T, Stradner M, Strohmaier HM, Buck CR, Denk H, Schroeder R, Trauner M, Zatloukal K. Characterization of HULC, a novel gene with striking up-regulation in hepatocellular carcinoma, as noncoding RNA. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:330–342. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang F, Zhang L, Huo XS, Yuan JH, Xu D, Yuan SX, Zhu N, Zhou WP, Yang GS, Wang YZ, et al. Long noncoding RNA high expression in hepatocellular carcinoma facilitates tumor growth through enhancer of zeste homolog 2 in humans. Hepatology. 2011;54:1679–1689. doi: 10.1002/hep.24563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan SX, Yang F, Yang Y, Tao QF, Zhang J, Huang G, Yang Y, Wang RY, Yang S, Huo XS, et al. Long noncoding RNA associated with microvascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma promotes angiogenesis and serves as a predictor for hepatocellular carcinoma patients’ poor recurrence-free survival after hepatectomy. Hepatology. 2012;56:2231–2241. doi: 10.1002/hep.25895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin R, Maeda S, Liu C, Karin M, Edgington TS. A large noncoding RNA is a marker for murine hepatocellular carcinomas and a spectrum of human carcinomas. Oncogene. 2007;26:851–858. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braconi C, Kogure T, Valeri N, Huang N, Nuovo G, Costinean S, Negrini M, Miotto E, Croce CM, Patel T. microRNA-29 can regulate expression of the long non-coding RNA gene MEG3 in hepatocellular cancer. Oncogene. 2011;30:4750–4756. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matouk IJ, DeGroot N, Mezan S, Ayesh S, Abu-lail R, Hochberg A, Galun E. The H19 non-coding RNA is essential for human tumor growth. PLoS One. 2007;2:e845. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie C, Yuan J, Li H, Li M, Zhao G, Bu D, Zhu W, Wu W, Chen R, Zhao Y. NONCODEv4: exploring the world of long non-coding RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D98–103. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kornienko AE, Dotter CP, Guenzl PM, Gisslinger H, Gisslinger B, Cleary C, Kralovics R, Pauler FM, Barlow DP. Long non-coding RNAs display higher natural expression variation than protein-coding genes in healthy humans. Genome Biol. 2016;17:14. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0873-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, Han L, Roebuck P, Diao L, Liu L, Yuan Y, Weinstein JN, Liang H. TANRIC: an interactive open platform to explore the function of lncRNAs in cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75:3728–3737. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guttman M, Donaghey J, Carey BW, Garber M, Grenier JK, Munson G, Young G, Lucas AB, Ach R, Bruhn L, et al. lincRNAs act in the circuitry controlling pluripotency and differentiation. Nature. 2011;477:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature10398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu W, Wagner EK, Hao Y, Rao X, Dai H, Han J, Chen J, Storniolo AM, Liu Y, He C. Tissue-specific co-expression of long non-coding and coding RNAs associated with breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32731. doi: 10.1038/srep32731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deng L, Yang SB, Xu FF, Zhang JH. Long noncoding RNA CCAT1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by functioning as let-7 sponge. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2015;34:18. doi: 10.1186/s13046-015-0136-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Z, Lu Y, Xu Q, Tang B, Park CK, Chen X. HULC and H19 played different roles in overall and disease-free survival from Hepatocellular carcinoma after curative hepatectomy: a preliminary analysis from gene expression omnibus. Dis Markers. 2015;2015:191029. doi: 10.1155/2015/191029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng W, Fan H. Long non-coding RNA PANDAR correlates with poor prognosis and promotes tumorigenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomed Pharmacother. 2015;72:113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang Z, Huang L, Shen S, Li J, Lu H, Mo W, Dang Y, Luo D, Chen G, Feng Z. Sp1 cooperates with Sp3 to upregulate MALAT1 expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2015;34:2403–2412. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pan Q, Long X, Song L, Zhao D, Li X, Li D, Li M, Zhou J, Tang X, Ren H, Ding K. Transcriptome sequencing identified hub genes for hepatocellular carcinoma by weighted-gene co-expression analysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:38487–38499. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jing W, Gao S, Zhu M, Luo P, Jing X, Chai H, Tu J. Potential diagnostic value of lncRNA SPRY4-IT1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2016;36:1085–1092. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.4859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang M, Wang W, Li T, Yu X, Zhu Y, Ding F, Li D, Yang T. Long noncoding RNA SNHG1 predicts a poor prognosis and promotes hepatocellular carcinoma tumorigenesis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;80:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Z, Wei X, Zhang A, Li C, Bai J, Dong J. Long non-coding RNA HNF1A-AS1 functioned as an oncogene and autophagy promoter in hepatocellular carcinoma through sponging hsa-miR-30b-5p. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;473:1268–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao JZ, Li J, Du JL, Li XL. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR is a marker for hepatocellular carcinoma progression and tumor recurrence. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:1791–1798. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang H, Xing Z, Mani SK, Bancel B, Durantel D, Zoulim F, Tran EJ, Merle P, Andrisani O. RNA helicase DEAD box protein 5 regulates Polycomb repressive complex 2/Hox transcript antisense intergenic RNA function in hepatitis B virus infection and hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatology. 2016;64:1033–1048. doi: 10.1002/hep.28698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang L, Li C, Lan T, Wu L, Yuan Y, Liu Q, Liu Z. Decreased expression of long non-coding RNA GAS5 indicates a poor prognosis and promotes cell proliferation and invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma by regulating vimentin. Mol Med Rep. 2016;13:1541–1550. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang T, Cao C, Wu D, Liu L. SNHG3 correlates with malignant status and poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:2379–2385. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Y, Chen L, Gu J, Zhang H, Yuan J, Lian Q, Lv G, Wang S, Wu Y, Yang YT, et al. Recurrently deregulated lncRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14421. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gutschner T, Diederichs S. The hallmarks of cancer: a long non-coding RNA point of view. RNA Biol. 2012;9:703–719. doi: 10.4161/rna.20481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bartonicek N, Maag JL, Dinger ME. Long noncoding RNAs in cancer: mechanisms of action and technological advancements. Mol Cancer. 2016;15:43. doi: 10.1186/s12943-016-0530-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang C, Li X, Zhao H, Liu H. Long non-coding RNAs: potential new biomarkers for predicting tumor invasion and metastasis. Mol Cancer. 2016;15:62. doi: 10.1186/s12943-016-0545-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quackenbush J. Computational analysis of microarray data. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:418–427. doi: 10.1038/35076576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quackenbush J. Genomics. Microarrays--guilt by association. Science. 2003;302:240–241. doi: 10.1126/science.1090887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liao Q, Liu C, Yuan X, Kang S, Miao R, Xiao H, Zhao G, Luo H, Bu D, Zhao H, et al. Large-scale prediction of long non-coding RNA functions in a coding-non-coding gene co-expression network. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:3864–3878. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang X, Driscoll DM, Morton RE. Molecular cloning and expression of lipid transfer inhibitor protein reveals its identity with apolipoprotein F. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1814–1820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morton RE, Gnizak HM, Greene DJ, Cho KH, Paromov VM. Lipid transfer inhibitor protein (apolipoprotein F) concentration in normolipidemic and hyperlipidemic subjects. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:127–135. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700258-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Green PS, Vaisar T, Pennathur S, Kulstad JJ, Moore AB, Marcovina S, Brunzell J, Knopp RH, Zhao XQ, Heinecke JW. Combined statin and niacin therapy remodels the high-density lipoprotein proteome. Circulation. 2008;118:1259–1267. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.770669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rutkowski MJ, Sughrue ME, Kane AJ, Mills SA, Parsa AT. Cancer and the complement cascade. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8:1453–1465. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Falanga A, Marchetti M, Vignoli A. Coagulation and cancer: biological and clinical aspects. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:223–233. doi: 10.1111/jth.12075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deng X, Hu Y, Ding Q, Han R, Guo Q, Qin J, Li J, Xiao R, Tian S, Hu W, et al. PEG10 plays a crucial role in human lung cancer proliferation, progression, prognosis and metastasis. Oncol Rep. 2014;32:2159–2167. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Akamatsu S, Wyatt AW, Lin D, Lysakowski S, Zhang F, Kim S, Tse C, Wang K, Mo F, Haegert A, et al. The placental gene PEG10 promotes progression of Neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Cell Rep. 2015;12:922–936. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiong J, Qin J, Zheng Y, Peng X, Luo Y, Meng X. PEG10 promotes the migration of human Burkitt's lymphoma cells by up-regulating the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9. Clin Invest Med. 2012;35:E117–E125. doi: 10.25011/cim.v35i3.16587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu DC, Yang ZL, Jiang S. Identification of PEG10 and TSG101 as carcinogenesis, progression, and poor-prognosis related biomarkers for gallbladder adenocarcinoma. Pathol Oncol Res. 2011;17:859–866. doi: 10.1007/s12253-011-9394-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peng YP, Zhu Y, Yin LD, Zhang JJ, Wei JS, Liu X, Liu XC, Gao WT, Jiang KR, Miao Y. PEG10 overexpression induced by E2F-1 promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in pancreatic cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36:30. doi: 10.1186/s13046-017-0500-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li X, Xiao R, Tembo K, Hao L, Xiong M, Pan S, Yang X, Yuan W, Xiong J, Zhang Q. PEG10 promotes human breast cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion. Int J Oncol. 2016;48:1933–1942. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2016.3406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kainz B, Shehata M, Bilban M, Kienle D, Heintel D, Kromer-Holzinger E, Le T, Krober A, Heller G, Schwarzinger I, et al. Overexpression of the paternally expressed gene 10 (PEG10) from the imprinted locus on chromosome 7q21 in high-risk B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:1984–1993. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bang H, Ha SY, Hwang SH, Park CK. Expression of PEG10 is associated with poor survival and tumor recurrence in Hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res Treat. 2015;47:844–852. doi: 10.4143/crt.2014.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cabili MN, Trapnell C, Goff L, Koziol M, Tazon-Vega B, Regev A, Rinn JL. Integrative annotation of human large intergenic noncoding RNAs reveals global properties and specific subclasses. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1915–1927. doi: 10.1101/gad.17446611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yan X, Hu Z, Feng Y, Hu X, Yuan J, Zhao SD, Zhang Y, Yang L, Shan W, He Q, et al. Comprehensive genomic characterization of long non-coding RNAs across human cancers. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:529–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they were used in the current research program, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.