Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Previous studies showed that family caregivers of hemodialysis patients have low level of quality of life. However, these caregivers are mostly neglected, and no studies are available on improving their quality of lives. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the effects of supportive educative program on the quality of life in family caregivers of hemodialysis patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

A randomized controlled clinical trial was conducted on 76 family caregivers of hemodialysis patients referred to Shahid Hasheminejad Hemodialysis Center in Tehran, Iran in 2015. The subjects were equally allocated into two groups of 38. Caregivers of patients were randomly assigned into the intervention group and the control group. The intervention group received six training sessions on supportive educative program. Both groups answered demographic information and short form-36 questionnaires before and 6 weeks after the intervention. Descriptive statistics, Chi-square and Fisher exact tests, independent samples t-test, and t-couple, was used to analyze the data.

RESULTS:

No significant difference was found between the baseline mean scores of “quality of life” of the intervention and the control groups (P = 0.775). However, the mean scores of quality of life of the intervention group increased at the end of the study, and the two groups were significantly different in this regard (P < 0.001).

CONCLUSIONS:

Supportive educative program improved the quality of life in caregivers of hemodialysis patients. Therefore, it is suggested that health system managers encourage their staff to implement such programs for improving the health status of the caregivers.

Keywords: Caregivers, hemodialysis, quality of life, supporting, teaching

Introduction

Chronic renal failure (CRF) makes significant changes in the life of patients and their families. About 2–3% of people worldwide and more than 10% of Americans are affected by CRF.[1] The disease is increasing in developing countries so that its prevalence in Iran increased from 238 cases per million people in 2000–354 cases per million in 2006.[2] A few treatment options are available for patients with CRF, including hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and kidney transplantation.[3] Hemodialysis was the most common treatment method known in the world and including 70% of renal replacement therapy in 2014.[1] In Iran, review study shows that 47.7% of all patients with CRF use hemodialysis so that 25,934 patients were under chronic hemodialysis in 2013.[4] Although the widespread availability of hemodialysis prolongs the lives of thousands of patients with end-stage renal diseases; However, these patients suffer from many problems and complications.[5,6]

Hemodialysis patients suffer from high degree of disability, loss of function, and family lives; therefore, they need additional support from others among whom family caregivers play the most significant role in providing suitable support and care,[7,8] and they have the most central role in patient's adapting to and managing this chronic disorder.[6,9]

Chronic illness of a family member and its economic and psychosocial consequences will involve the entire family and affect their lifestyle. Studies show that family caregivers of patients with chronic illness experience a vast range of physical and emotional distress and psychological symptoms, including depression, anxiety, anger, despair, and feelings of guilt and shame.[10,11,12] Furthermore, having the role of a caregiver in the family (an increasing phenomenon) affects the people's quality of life and accordingly has become one of the community health problems.[6,13] Therefore, family caregivers are at risk of becoming ill and are sometimes called hidden patients.[14]

Even though basically, the caregiving role enhances sense of affection and love, gives meaning to their lives, strengthens their family ties, creates sense of self-content, and results in respect for themselves and others.[15] The reality is that taking care of hemodialysis patients at home reduces the quality of life and the ability of the caregiver.[8,13] Studies have showed that family caregivers have an exclusive role in caring for patients undergoing hemodialysis and their quality of life decrease in this situation.[16,17] Similarly, Habibzadeh et al. reported the low caregivers’ “quality of life” in all aspects.

In hemodialysis centers, health professionals are responsible for patient care. However, at home, the patient's relatives undertake this role.[18] These caregivers are often deficient in knowledge and skills related to patient care, lack social support, or support from health-care system. With disease progression, patients became more disabled, and caregivers are confronted with more complex caring needs.[19] In this regard, Mollaoglu et al. showed that caregivers’ most vital educational needs are patients’ nutrition (35/2%), dialysis (27/8%), fistula care (20/4%), caring of catheter (18/8%), CRF knowledge (18%), blood pressure (17/2%), weight control (17/2%), hygiene (3/1%), and sport and travel (6/5%);[18] according to Isenberg and Trisolini's study, most hemodialysis family caregivers reported insufficient knowledge of the disease, control of symptoms, and patient care. In addition, they mostly wanted to know about the food and drug management of their patients.[19]

According to the research results of Belasco et al., 70% of caregivers face two major problems, one of which is associated with the care and treatment of the disease, and the other one related to adjustment with caring responsibilities.[8] In addition, findings show that caregivers suffer anger, stress, and compatibility issues resulting from taking care of chronic patients.[11,20] Hence, caregivers in addition caring skills require applying other skills in stressful situations to facilitate proper relationship with the patient, reduce stress and tension, and increase problem-solving and compatibility abilities.[21,22]

Studies suggest that whenever people placed under stressful situations, effective adaptation can protect them from physical and mental harm and that coping skills of caregivers play vital role in removing tensions and promoting their mental health status.[21,23,24,25] Coping skills is a process through which individuals manage their interaction with the environment. Appropriate coping skill is essential for family members to enhance the quality of life. These skills are divided into two categories: problem-focused and emotion-focused.[26,27] Problem-focused coping skills consist of direct behavioral and mental functions carried out by the individual to change and modify threatening environmental conditions. Direct confrontation, seeking social support, anger management, and communication skills are also parts of problem-focused coping capabilities.[20,25]

The results of other studies have indicated the effect of supportive educative program, which consists of problem-focused skills and strategies for taking care of patients at home, on increasing the quality of life of caregivers of other chronic diseases such as cancer, heart failure, dementia, mental illness, and diabetes.[21,28,29,30,31] In addition, the results of systematic review and descriptive studies confirmed the necessity of implementing supportive educative program to enhance quality of the lives of caregivers.[32,33,34] However, the caregivers of hemodialysis patients are mostly neglected, and few studies are available on home care training for these caregivers[18,35] and no studies are available on the effectiveness of supportive educative on the quality of life in these caregivers. This study aimed to examine the effect of home care training and problem-focused coping strategies (communication skills, anger control, and deep breathing) on the quality of life in family caregivers of hemodialysis patients.

Methods

The present research is a randomized, educational trial study, involving a control group, which investigated the effect of supportive educative program on enhancement quality of life in 76 family caregivers of hemodialysis patients who referred to hemodialysis section of in Shahid Hashemi Nejad Hospital in Tehran in 2015. Inclusion criteria for the caregivers were as follows: being a patient's first-degree relative, having the responsibility for the home care of his or her hemodialysis patient, willingness to participate in the study, at least 18 years of age, writing and reading literacy, having no known psychological or neurological disorders, having no severe family conflict, and not being a health-care worker. Inclusion criteria for the patients were as follows: performing regular hemodialysis for at least 2 months, at least three times a week, and for 3–4 h in each session; having no history of kidney transplantation; and having a family caregiver to do home care. The lack of appropriate cooperation by the caregiver, participation in similar training courses, the occurrence of a family crisis (divorce, financial crisis, the death of a first-degree family member) during the study, a subject's decision to withdraw from the study, the absence of even a training session, and booking the patient on the kidney transplantation list were selected as exclusion criteria.

The required sample size for each group after investing the amounts in the following formula estimated 38.

A two-part instrument was used. The first part included a demographic questionnaire including questions on the caregiver's and the patient's demographic data, such as the caregiver's age, gender, marital status, education level, job, type of family relationship with the patient, financial status, having a known physical illness, and the size of their family as well as the duration of the patient's disease, duration of using regular hemodialysis, history of kidney transplantation, dialysis association membership, having active insurance coverage, and the type of insurance coverage. The Farsi version of the short-form quality of life (SF-36) questionnaire was used as the second part of the study instrument.[36]

Quality of life (SF-36) questionnaire is a universal standard criteria. Its shortened form contains 36 items divided into three levels: (1) Questions, (2) eight scales with any combination of 2–10 questions as physical health (10), bodily pain (2), general health (6), physical role functioning (4), vitality (3), emotional role functioning (3), social functioning (2), mental health (6), and (3) two summary scales forming physical health components (physical function, bodily pain, general health, and physical role functioning), and mental health components (vitality, emotional role functioning, social functioning, and mental health). The mean scale is calculated separately, and the results of each scale vary from 0 to 100. The lowest score on this questionnaire is 0, and maximum score is 100. Zero is the worst case, and the higher scores reflect the better quality of life.[37] This scale was translated to Farsi by Montazeri et al.[36] and its validity and reliability were confirmed through content validity and internal consistency method (0.70–0.85); also, its Cronbach α has been reported in the range of 0.70–0.90.[36] Furthermore, in a preliminary study on the thirty caregivers of patients undergoing hemodialysis, the Cronbach α was calculated as 0.82. However, the data of preliminary study was not used in the final analysis.

After approval of the study was obtained, the first researcher referred to the aforementioned hemodialysis center, and through a file review and interviews with the patients, those with inclusion criteria were found. Then, the researcher made telephone contact with the patient's main caregivers, and through telephone interviews, assessed their eligibility, informed them that a study is starting to investigate caregiver's quality of life, and invited them to participate in the study. Caregivers who agreed to take part were informed that they would be involved the study for about 2 months and would be asked to complete the questionnaires two times, during the study. Then, all of them were invited to attend a session in the hall of the dialysis center to complete the study instrument and were informed that after a while they would be invited to attend several educational sessions. Subsequently, through a coin-tossing method, caregivers of the patients who referred on even or odd days of the week were randomly assigned to either the intervention group or the control group, respectively. Then, the 38 caregivers in the intervention group were allocated into five small subgroups of five to eight, and each subgroup participated in two training sessions on how to take care of hemodialysis patients at home and four training sessions on problem-focused coping strategies (proper communication, anger management, and deep breathing) that were held three sessions per week, in 2 consecutive weeks, and each session lasted for about an hour. All coping skills training sessions were delivered by an expert psychiatric nurse that was previously trained and tested to facilitate group discussions.

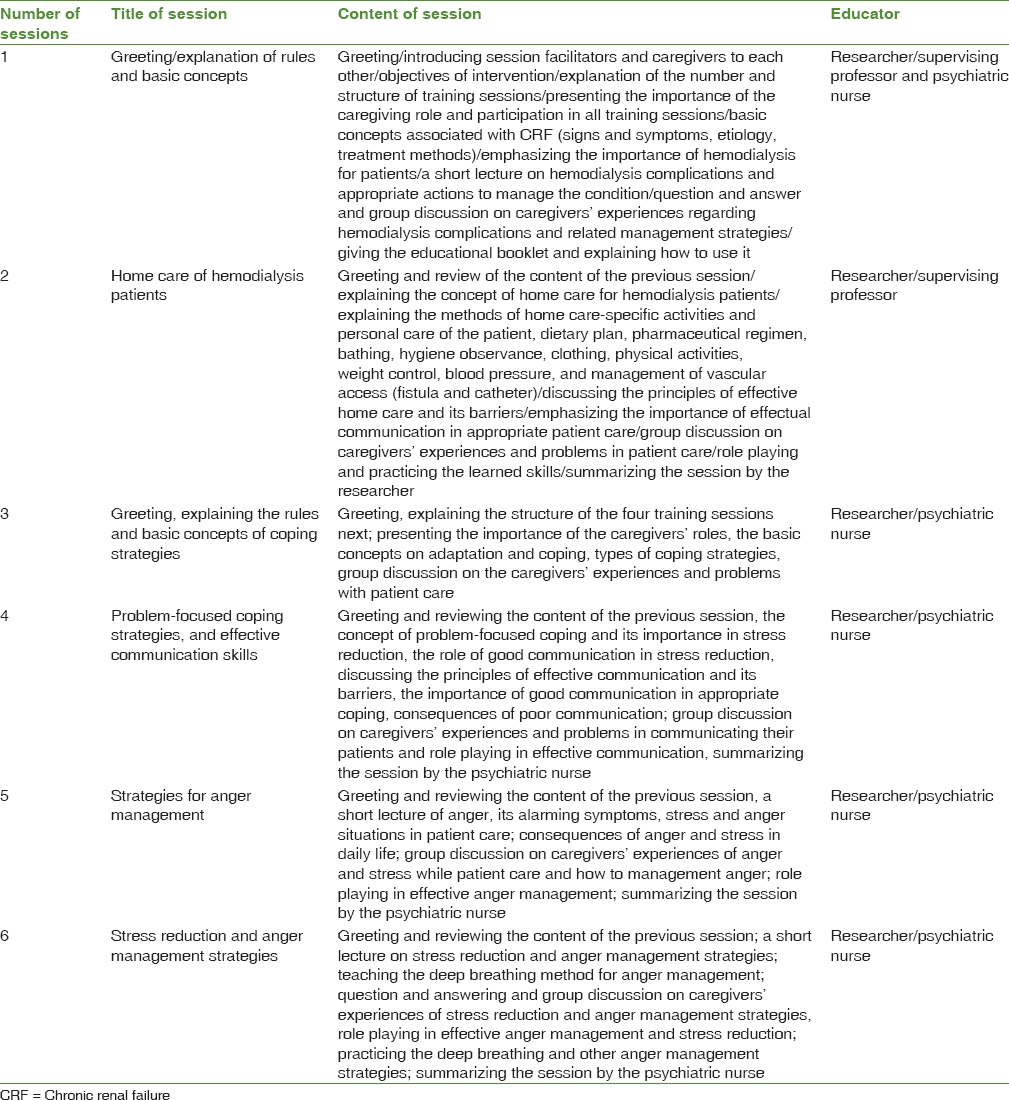

Each session consisted of a combination of a short PowerPoint facilitated lecture, a group discussion, a question and answer period, and a role playing. The researcher motivated the caregivers to present their questions and ambiguities and participate in activities through group discussion and question and answer and finally, summed up what was mentioned at the end of session. The caregivers were asked to practice the skills at home while taking care of patients; the researcher's phone number was given in case of emergent questions. At the end of the first session, an educational booklet related to the issue was given to all the participants to be read and exercised at home. The content validity of the educational booklet was confirmed by 10 nursing professors in the Tehran, Iran, and Shahid-Beheshti Universities of Medical Sciences. The outline of training sessions is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Outline of educational sessions

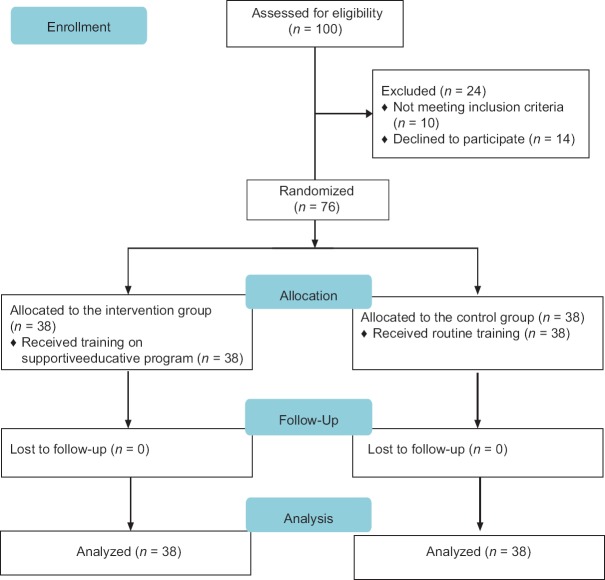

Six weeks after the last educational session, all subjects in the experimental group and the control group were again invited to attend a session in the hall of the dialysis center and responded to the study instrument. The control group received only routine trainings which included educational pamphlets [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The study flow diagram

Permission was also sought from the authorities in the university and the Shahid Hasheminejad Dialysis Center. All participants were briefed about the study's purposes and the voluntary nature of their participation. They all signed a written informed consent, were assured of the anonymity and confidentiality of the data, and were also reminded that they can withdraw from the study at any time. The researchers were sensitive to preserving the participants’ rights according to the Helsinki ethical declaration. To observe ethics, the caregivers in the control group also received the educational booklet after the last assessment.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 21.0 [IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA]. Descriptive statistics such as frequencies, percentage, mean, and standard deviation was calculated. Chi-square test was used to compare the nominal and categorical variables, such as gender, marital status, education level, job, and having a chronic comorbidity, the caregivers’ mean age between the two groups. Fisher's exact test was used to compare the two groups in terms of the patients’ duration of hemodialysis, type of insurance coverage, dialysis association membership, and caregivers’ relationship with the patient and financial status. The independent-samples t-test and t-couple were used to compare the mean quality of life scores between and in the two groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all tests.

Results

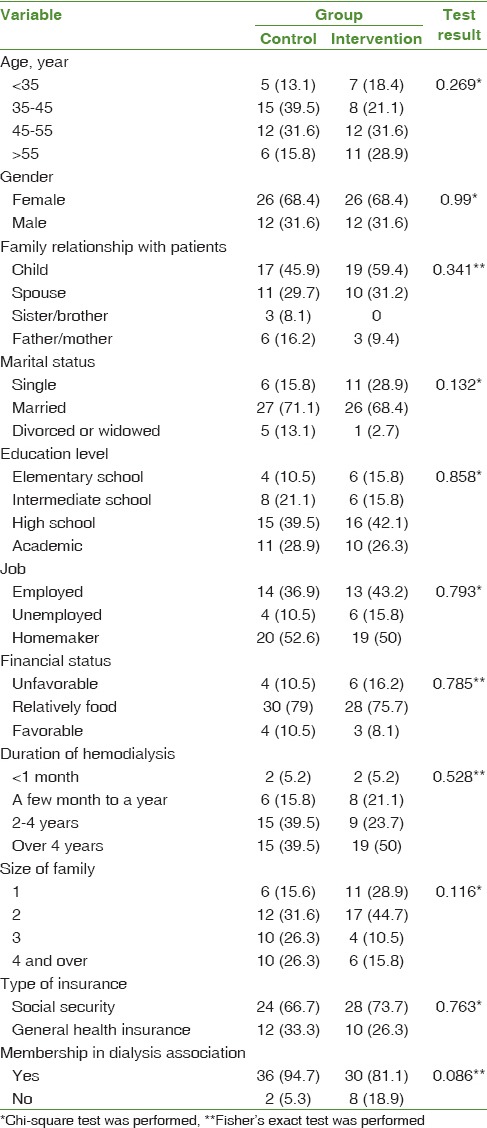

The majority of caregivers (54%) were in age range of 35–55 years, female (68.4%), married (70%), and (77.6%) had no physical disorder. Most of their patients (76.35%) were using regular hemodialysis for more than 2 years, (87/9%) were registered in the dialysis community, and all patients had insurance coverage. No significant difference was found between the mean age of the intervention and the control groups (46.57 ± 10.82 vs. 44.28 ± 8.52 years, P = 0.269). 68.4% of the family caregivers in both groups were female. In addition, the results of Table 2 show that no significant difference was found between the 2 groups with regard to other demographic variables [Table 2].

Table 2.

The distribution of demographic variables in two groups of caregivers

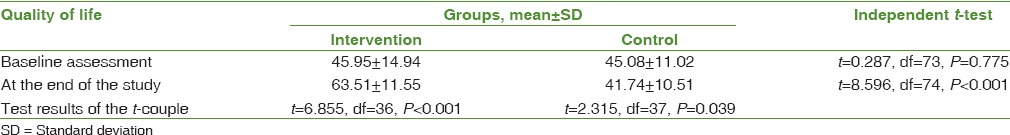

According to the analysis of data and findings of sample t-test, no significant difference was found between the baseline mean “quality of life” scores of the two groups before the intervention (P = 0.039). However, the mean “quality of life” score in the intervention group increased at the end of the study, and the two groups were significantly different in this regard (P < 0.001). In addition, the findings of couple t-test showed that the quality of life of intervention group differed significantly before and after the intervention (P < 0.001) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of the mean quality of life scores in the study groups before and after the intervention

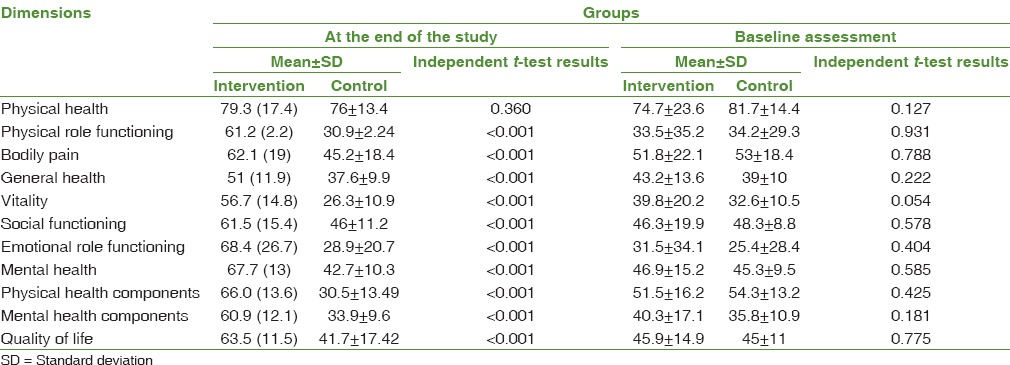

The mean scores of the different domains of “quality of life” were also compared between two groups. Before the intervention, no significant difference was observed between them. However, the mean scores of the intervention group increased in all domains (except in physical domain) after the intervention (P < 0.001) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison of the mean of different domains of quality of life in the study groups before and after the intervention

Discussion

In this study, for the first time, we evaluated the effectiveness of supportive educative program on the quality of life of the family caregivers of hemodialysis patients. The result of present study showed that learning coping strategies and educational program can increase these caregivers’ quality of life.

The mean score of quality of life among caregivers of patients undergoing hemodialysis was 45.5 at the start of the current study that is representative of the low quality of life in these caregivers. Habibzadeh et al. and Belasco et al. also reported that taking care of hemodialysis patients causes a feeling pressure and negative effects on the quality of life of caregivers.[8,17]

The results of the previous studies indicate both insufficient knowledge and skills in the field of patient care.[18,19,32,33,34] Accordingly, train and support necessity for caregivers of patients undergoing hemodialysis to cope with their caring roles and to improve their quality of lives.[8,17,32] However, no interventional studies are available to improve their quality of lives. Just in a study without control group in Turkey, Mollaoglu et al. investigated the effects of education on caregivers’ burden and reported that education was effective in reducing caregivers’ burden.[18] Regarding these results, for the first time, we decided to evaluate the effectiveness of supportive educative program on the quality of lives of caregivers for patients undergoing hemodialysis. The present study showed that home care training (giving information about CRF, hemodialysis, its complications, and how to take care of patients at home) can improve their quality of lives. So that mean and standard deviation of the quality of life of caregivers increased from 45.9 ± 14.9 to 63.5 ± 11.50; this increase implied the efficiency of educative program on the quality of life of caregivers. In addition, educational intervention on caregivers of patients with CVA in Thailand showed the enhanced quality of life of caregivers.[28] Belgacem et al. showed the positive effects of training program on quality of life of caregivers of cancer patients.[38] However, those two studied paid less attention to supporting caregivers and focused merely on training them.

In addition to learning how to take care of patients, coping skills help them ease tensions, comply with their caring role, and promote mental health.[20,22] According to in Grey et al. and Khanjari et al. studies, the quality of life of parents has increased after coping skills training through lecture and group discussion.[21,25] Therefore, considering the decisive role of coping skills in compatibility of caregivers, second part of the intervention program teached problem-focused coping skills such as communication skills, anger management, and deep breathing. The research attempts to encourage the caregivers to make themselves compatible with their role and relieve the tension burdening them so that they can perform their responsibility more effectively.

Etemadifar et al. argued that presenting group support to caregivers of heart failure patients increases the ability and self-esteem of family members to provide better care at home through reducing stress and pressure of their responsibility.[30] Navidian et al. believe that empowering family as a group can promote their quality of patient care and improve their physical and mental health.[29]

After implementing supportive educative program, results of the study show considerable difference in all dimensions of quality of life except physical function between intervention and control groups; most significant increase in intervention group is related to these dimensions: limitations in function due to physical and emotional problems, mental health, vitality, social function, physical pain, general health, and physical function. In general, the score of physical and mental health of quality of life of caregivers in the intervention group is 51.59–66.04, and 40.30–60.99 before and after the intervention, this suggests that although physical health of caregivers have high score after intervention, their mental health has been further increased after the intervention; therefore, based on results, supportive educative program has had great impact on emotional and mental aspects of quality of life. Unlike the score of quality of life of intervention group, the scores of control group subjects indicate significantly decreased in physical function, physical pain, vitality, and physical health 6 weeks after intervention.

Unlike the results of the present study, the results of a study on caregivers of women with breast cancer showed that after the administration of the supportive educative program, their quality of lives in physical, emotional, and mental aspects significantly increased (P < 0.001), but not in the social aspect.[31] Furthermore, in the present study, the caregivers had no consensus over the provided services by the Dialysis Association Society; therefore, the lower score of social domain can be related to the insufficient social support of caregivers from the Dialysis Society. For example, in the study of Habibzadeh et al., despite participants’ membership in Dialysis Association, about 85% of caregivers had reported insufficient support from the society.[17]

Studies have shown that besides knowledge and skills on coping strategies, caregivers of hemodialysis patients need counseling, empathy, and psychological support to cope with their caregiving roles.[32,33,34] Isenberg and Trisolini in 2008 and Khanjari et al. 2014 showed that group discussions and sharing experiences among caregivers are effective in providing ways to give and receive empathy and psychological support.[19,25] Confirming the findings of the previous studies, the present study also showed that these strategies, along with educating the caregivers on problem-focused coping strategies. Furthermore, in the current study, besides group discussion, we used role playing to educate home care and gave caregivers the researcher's phone number to ask any caring questions. It can be acknowledged that using the different methods of education such as role-playing, group discussion, question and answer, and phone consultation was helpful in the better learning and practical application of the learned skills and improving the caregivers’ quality of life.

Most of the caregivers in this study were females who were daughters or wives of the hemodialysis patients. This finding was consistent with previous studies.[18,30] Evidence shows that most of caregivers of the chronic patients in Asian families are females.[18,29,30,31] Mollaoglu et al. have also reported that female family caregivers are usually more sentimental and sensitive to patients caring needs and also have greater ability than men in the management of problems and establishment of intimate relationships with patients.[18] Therefore, it is recommended that future studies pay more attention to the role of woman in taking care of chronic patients.

This study was conducted only on caregivers of patients in a dialysis center; the small sample size and the relatively short follow-up period can be considered limitations to generalize the findings of this study. Therefore, the replication of similar studies with larger sample sizes and longer periods of follow-up is recommended. Moreover, as in any questionnaire study, the caregivers’ responses to the questionnaire might have been affected by their psychological condition, and this was not under the full control of the researchers.

Conclusion

The current study showed the effectiveness of supportive educative program on the quality of life of family caregivers of hemodialysis patients. Based on the results of the present study, we can conclude that training home-care capabilities and problem-focused coping skills to caregivers of hemodialysis patients can promote their quality of life through integrating communication skills in relationship with the patient and relatives, anger management skills, and deep breathing practices in stressful situations. At present, no program is running on educating family caregivers in the health-care system of Iran and caregivers of hemodialysis patients are totally ignored. Authorities and policymakers in the health-care system are responsible to take strategies to integrate educational programs such as the program implemented in the current study the country's health-care system.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (grant no. 94-01-28-25834-110422), and it was recorded I the Registry of Clinical Trials with the code of IRCT 138809032769N1.

Financial support and sponsorship

This resultant article has been part of the master's thesis of the first author and also is the research project approved by Iran University of Medical Sciences (Project No. 94-01-28-25834) and was funded by Research Deputy of Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors are deeply thankful to the authorities in Shahid Hasheminejad Hemodialysis Center and all family caregivers who participated in this study and professors of Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Iran University.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System. USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aghighi M, Mahdavi-Mazdeh M, Zamyadi M, Heidary Rouchi A, Rajolani H, Nourozi S. Changing epidemiology of end-stage renal disease in last 10 years in Iran. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2009;3:192–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arefzadeh A, Lessanpezeshki M, Seifi S. The cost of hemodialysis in Iran. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2009;20:307–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mousavi SS, Soleimani A, Mousavi MB. Epidemiology of end-stage renal disease in Iran: A review article. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2014;25:697–702. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.132242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bag E, Mollaoglu M. The evaluation of self-care and self-efficacy in patients undergoing hemodialysis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16:605–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levey AS, Coresh J. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet J. 2012;379:165–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayoub AM, Hijjazi KH. Quality of life in dialysis patients from the United Arab Emirates. J Family Community Med. 2013;20:106–12. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.114772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belasco A, Barbosa D, Bettencourt AR, Diccini S, Sesso R. Quality of life of family caregivers of elderly patients on hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48:955–63. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janssen DJ, Spruit MA, Wouters EF, Schols JM. Family caregiving in advanced chronic organ failure. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:394–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Low J, Smith G, Burns A, Jones L. The impact of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) on close persons: A literature review. NDT Plus. 2008;1:67–79. doi: 10.1093/ndtplus/sfm046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roth DL, Fredman L, Haley WE. Informal caregiving and its impact on health: A reappraisal from population-based studies. Gerontologist. 2015;55:309–19. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mollaoglu M. Perceived social support, anxiety, and self-care among patients receiving hemodialysis. Dial Transplant J. 2006;35:144–55. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shdaifat EA, Abdul Manaf M. Quality of life of caregivers and patients undergoing haemodialysis at ministry of health, Jordan. Int J Appl Sci Technol. 2012;2:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palma E, Simonetti V, Franchelli P, Pavone D, Cicolini G. An observational study of family caregivers’ quality of life caring for patients with a stoma. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2012;35:99–104. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0b013e31824c2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gauthier A, Vignola A, Calvo A, Cavallo E, Moglia C, Sellitti L, et al. A longitudinal study on quality of life and depression in ALS patient-caregiver couples. Neurology. 2007;68:923–6. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000257093.53430.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alvarez-Ude F, Valdés C, Estébanez C, Rebollo P FAMIDIAL Study Group. Health-related quality of life of family caregivers of dialysis patients. J Nephrol. 2004;17:841–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Habibzadeh H, Jafarizadeh H, Mohammadpoor Y, Kiani P, Lak K, Bahrechi A. A survey on quality of life in hemodialysis patient caregivers. J Nurs Midwifery Urmia Univ Med Sci. 2009;7:128–135. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mollaoglu M, Kayatas M, Yürügen B. Effects on caregiver burden of education related to home care in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Hemodial Int. 2013;17:413–20. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isenberg KB, Trisolini M. Information needs and roles for family members of dialysis patients. Dial Transplant. 2008;37:50–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen HM, Huang MF, Yeh YC, Huang WH, Chen CS. Effectiveness of coping strategies intervention on caregiver burden among caregivers of elderly patients with dementia. Psychogeriatrics. 2015;15:20–5. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grey M, Jaser SS, Whittemore R, Jeon S, Lindemann E. Coping skills training for parents of children with type 1 diabetes: 12-month outcomes. Nurs Res. 2011;60:173–81. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3182159c8f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alnazly EK. Burden and coping strategies among Jordanian caregivers of patients undergoing hemodialysis. Hemodial Int. 2016;20:84–93. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belasco AG, Sesso R. Burden and quality of life of caregivers for hemodialysispatients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:805–12. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.32001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hudson P, Quinn K, Kristjanson L, Thomas T, Braithwaite M, Fisher J, et al. Evaluation of a psycho-educational group programme for family caregivers in home-based palliative care. Palliat Med. 2008;22:270–80. doi: 10.1177/0269216307088187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khanjari S, Seyedfatemi N, Borji S, Haghani H. Effect of coping skills training on quality of life among parents of children with leukemia. Journal of Hayat. 2014;19:15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Folkman S, Lazarus RS. The relationship between coping and emotion: Implications for theory and research. Soc Sci Med. 1988;26:309–17. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90395-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maes S, Leventhal H, De Ridder DT. Coping with chronic diseases. Handbook of Coping: Theory Research Applications. Vol. 1. New York: John Wiley; 1996. pp. 221–51. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oupra R, Griffiths R, Pryor J, Mott S. Effectiveness of supportive educative learning programme on the level of strain experienced by caregivers of stroke patients in Thailand. Health Soc Care Community. 2010;18:10–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Navidian A, Kermansaravi F, Rigi S. The effectiveness of a group psycho-educational program on family caregiver burden of patients with mental disorders. BMC Res Notes J. 2012;5:399. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Etemadifar S, Bahrami M, Shahriari M, Farsani AK. The effectiveness of a supportive educative group intervention on family caregiver burden of patients with heart failure. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2014;19:217–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bahrami M, Farzi S. The effect of a supportive educational program based on COPE model on caring burden and quality of life in family caregivers of women with breast cancer. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2014;19:119–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig JC. Support interventions for caregivers of people with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:3960–5. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abbasi A, Ashrafrezaee N, Asayesh H, Shariati A, Rahmani H, Mollaei E, et al. The relationship between caring burden and coping strategies in hemodialysis patients caregivers. J Nurs Midwifery Urmia Univ Med Sci. 2012;10:533–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aydede SK, Komenda P, Djurdjev O, Levin A. Chronic kidney disease and support provided by home care services: A systematic review. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15:118. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-15-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khorami Markani A, Saheli S, Sakhaei S, Khalkhali HR. The effect of family centered care educational program on home care knowledge among caregivers of patients with chronic renal failure under hemodialysis. J Nurs Midwifery Urmia Univ Med Sci. 2015;13:386–94. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montazeri A, Goshtasebi A, Vahdaninia M, Gandek B. The short form health survey (SF-36): Translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:875–82. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-1014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection, Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Belgacem B, Auclair C, Fedor MC, Brugnon D, Blanquet M, Tournilhac O, et al. A caregiver educational program improves quality of life and burden for cancer patients and their caregivers: A randomised clinical trial. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:870–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]