Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Pregnancy is one of the high-risk periods for women's health that the lack of attention to healthy behaviors such as weight control behaviors can lead to adverse consequences on the health of women and also the fetus. Therefore, the aim of this paper was to explore the determinants of weight control self-efficacy among pregnant women using Health Belief Model (HBM).

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

In this cross-sectional study were enrolled 202 pregnant women referring to Health Care Center in Isfahan city, Iran. Sampling method was multistage random. A researcher-made instrument based on HBM structures was used after confirming the valid and reliable. Data were analyzed by software SPSS 21 and descriptive statistics were represented with (frequency, mean and standard deviation) and analytical (Pearson correlation, independent t and liner regression) at the significant level of <0.05.

RESULTS:

The average age of participants was 27.80 ± 5.08. HBM structures were able explained 31% of variance of weight control self-efficacy. Also, of the studied structures, perceived benefits, perceived barriers were statistically significant predictors of weight control self-efficacy, within which perceived barriers (β = 0.391) was the most significant predictor.

CONCLUSION:

The findings of current study showed that the HBM model could be as a suitable framework to identify effective factors for designing educational intervention to improve weight control behaviors among pregnant women.

Keywords: Health belief model, pregnancy, self-efficacy, weight

Introduction

Pregnancy is a period which is critical for the fetal development and crucial to the pregnant mother.[1,2] Disregard for this important period is likely to result in complications such as obesity and overweight in the mother. It is accompanied by short-term and long-term complications in the mother and the infant, including blood-pressure disorders,[3,4] gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, long-term maternal diabetes,[5,6,7] eclampsia, cesarean section,[8] the increased risk of fetal macrosomia, childhood obesity,[9,10] and the increased risk of autism.[11] According to an estimate from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, around 48% of American women exceed the Institute of Medicine guidelines for standard weight gain during pregnancy.[12] A study by Farajzadegan et al. on Iranian women indicates that approximately 55% of them exceed the recommended guidelines during this period.[13] In order to prevent maternal and fetal complications of gestational excess weight gain, it is recommended that all pregnant women for whom nothing is contraindicated do moderate-intensity exercise regularly. Nevertheless, according to available evidence, pregnant women in both developed and developing countries have little inclination to engage in physical activity.[14] Studies demonstrate that some barriers to their engagement are lack of enough time for exercise, a feeling of limitation and restriction due to pregnancy,[15] and fear of harming the fetus.[16] In addition to the above-mentioned barriers to weight maintenance during pregnancy, there are also dietary challenges facing pregnant women, including lack of adequate fruit and vegetable consumption[17] and easy access to sweet foods.[6] Although women in prenatal care are given adequate training in a healthful diet, a high consumption of sweet foods among a large number of pregnant women[18,19] is one of problems which bring about inappropriate weight gain during pregnancy. Hence, it is necessary to identify factors behind dietary behaviors and physical activity, two key elements of weight maintenance. A body of evidence points to a relationship between health beliefs and preventive behaviors.[20,21] As one of frameworks for health education, the Health Belief Model (HBM) is used for discovering the relationship between health beliefs and behavior.[22,23] According to the HBM, a person's decision on and motivation for adopting a behavior depend on his perceptions of a risk posed (perceived susceptibility) and its seriousness (perceived severity), his belief in the efficacy of action taken to reduce the risk of a disease (perceived benefits), barriers to it, and modifying variables such as demographic data. Furthermore, cues to action act as a catalyst and fuel the desire to adopt particular health behaviors.[24] This model has been used in various studies.[25,26] According to a piece of research by Azadbakht et al., perceived barriers, self-efficacy, and perceived severity are the ultimate determinants of health-promoting behaviors among the elderly.[25] Moreover, Saunders et al. have reported in a study that the HBM is an effective model for identifying factors influencing behavior.[26] Considering the significance of weight for pregnant women's health and the identification of factors affecting the self-efficacy of weight-maintenance behaviors, the present study was carried out with the aim of identifying determinants of the self-efficacy of weight-maintenance behaviors among women in Isfahan, Iran, using the HBM.

Materials and Methods

Study population and sampling

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 202 pregnant mothers who had referred to health centers in Isfahan in 2016. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. The sampling technique chosen was cluster random sampling. Thus, first, all districts in Isfahan were categorized into five clusters, namely north, south, west, east, and center. Two health centers were randomly selected from each district. The study comprised a total of 20 health centers. Next, 20 pregnant women's medical records were randomly selected and included in the study – except for 2 health centers where 21 medical records were studied. Then, the people selected were called on the phone, informed about the objectives of the study, and motivated to participate in it. The participants filled out questionnaires in consulting rooms of the centers after receiving the researcher's necessary guidance. Illiterate subjects’ questionnaires were completed in an interview. The inclusion criteria were as follows: consent for participation in the study; the 18–35 age range for pregnant women; the prepregnancy body mass index (BMI) ≥18.5 kg/m2; no diagnosed mental health problem such as anxiety, depression, and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder; gestational age 15 weeks; singleton pregnancy; and no pregnancy complications, including hydramnios (excessive accumulation of amniotic fluid), eclampsia, preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, and morning edema >2+. The prepregnancy BMI was <30 kg/m2.

Data-collection tools

To collect data, a researcher-designed questionnaire based on the HBM constructs was used. The questionnaire had three sections. The first section consisted of demographic questions. These questions were about age, gestational age, level of education, employment status, and monthly household income. The second section was about knowledge. It comprised 11 items. For example: “increasing excessive weight in pregnancy result in fetus death.” The response options were “Yes,” “No,” and “I don’t know,” which were scored 2, 0, and 1, respectively. The third section related to questions concerning the HBM constructs, including perceived susceptibility, for example: “in women who aren’t sick, excessive weight gain in pregnancy isn’t harmful” perceived severity for example: “there is a relationship between maternal mortality and excessive weight gain in pregnancy,” perceived benefits for example “the control of excessive weight will improve my health in pregnancy,” perceived barriers for example: “the control over weight increase in pregnancy is very hard,” perceived self-efficacy for example: “I am certain that I can prevent of excessive weight gain during pregnancy with true nutritional program,” and cues to action for example: “the role of important persons such as: physician and spouse in control of excessive weight gain in pregnancy.” In order to evaluate perceived susceptibility and perceived severity, 7 and 9 items were designed, respectively. Furthermore, 5 items were developed to assess perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and perceived self-efficacy. A 4-point Likert scale (“agree,” “somewhat agree,” “somewhat disagree,” and “disagree”) was used for all of the 6 constructs. In addition, in order to assess cues to action, 5 items were designed and they were scored using a 5-point Likert scale (4 = “very high,” 3 = “high,” 2 = “moderate,” 1 = “low,” and 0 = “very low”). The validity of the questionnaire was evaluated by a panel of experts. In fact, the designed questionnaire was submitted to 6 professors of health education and midwifery. Their comments were applied to it. The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed using the test-retest method. To this end, the questionnaires were handed out to 20 pregnant women whose characteristics were completely similar to those of the case group. They were asked to fill out the questionnaires. After 1 week, they were given to the same pregnant women once more. The completed questionnaires were collected and the Cronbach's alpha coefficient was computed for each construct: knowledge 0.708, perceived susceptibility 0.787, perceived severity 0.798, perceived benefits 0.721, perceived barriers 0.723, perceived self-efficacy 0.733, and cues to action 0.711.

Statistical analysis

The following were used to analyze the collected data: the SPSS software, version 19; indicators of analytical statistics, such as Pearson's correlation, one-way analysis of variance, independent t-test, and linear regression model; and indicators of descriptive statistics, such as frequency, mean, and standard deviation. At all stages of the analysis, the significance level was considered to be <0.05.

Results

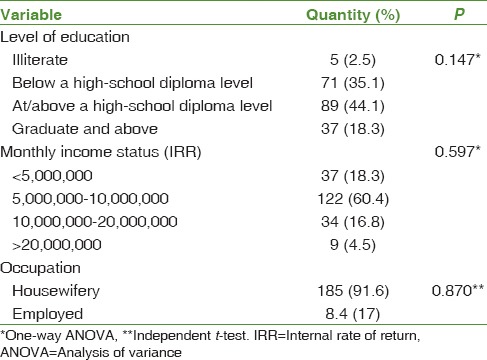

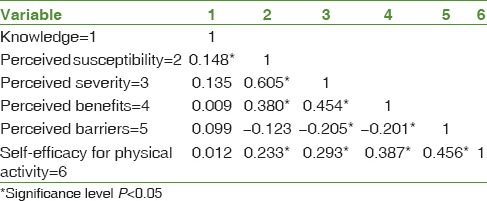

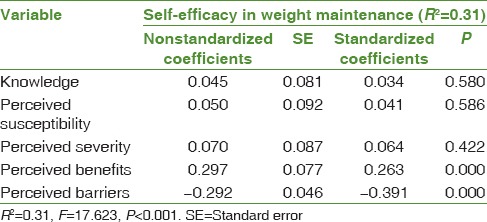

The participants of this study were 202 pregnant women in total. The mean and standard deviation of their age were 5.08 ± 27.80. Most of the participants were at/below a high-school diploma level (44.1%) and were housewives (91.6%). Moreover, a large number of the participants (60.4%) said their monthly incomes were between 5,000,000 and 10,000,000 internal rate of return [Table 1]. The results indicated that there was no statistically significant relationship between the demographic variables and the self-efficacy of physical activity [Table 1]. The mean, standard deviation, and Pearson's correlation coefficient of the HBM constructs are shown in Table 1. According to the results, all the HBM constructs had a significant correlation with the self-efficacy of physical activity. In other words, with a change in the scores of the constructs, the self-efficacy of physical activity too changed. The correlation of the self-efficacy of physical activity with perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, and perceived benefits was positive but the correlation with perceived barriers was negative. Of the HBM constructs, perceived barriers (r = −0.459) had the strongest correlation and perceived susceptibility (r = 0.233) had the weakest correlation. In addition, the results revealed that there was no significant correlation between the self-efficacy of physical activity and knowledge (P = 0.866 and r = 0.012) [Table 2]. According to the linear regression analysis, the HBM constructs could significantly predict 31% of the variance in the self-efficacy of physical activity among pregnant women (R2 = 0.31, F = 17.623, P < 0.001). Among the HBM constructs, perceived benefits and perceived barriers were the only significant predictors of the self-efficacy of physical activity. Perceived barriers were the strongest predictors (β = −0.391) [Table 3].

Table 1.

The relationship between the demographic variables and the self-efficacy of physical activity

Table 2.

The correlation between the health belief model constructs and knowledge

Table 3.

Results of the linear regression analysis for predicting the self-efficacy of physical activity

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the predictive role of the self-efficacy of physical activity among pregnant women. Having knowledge about the level of women's capability to maintain their weight during pregnancy and identifying factors affecting their capability could be effective in designing and implementing educational interventions with the aim of improving their weight-maintenance behaviors. Bandura believes that self-efficacy is a crucial component in a person's performance because it acts as an entity independent from a person's basic skills.[27,28,29,30] Moreover, self-efficacy has been regarded as an essential prerequisite for self-management to change behavior, which could promote health behaviors.[31] In the current study, the correlation between the self-efficacy of physical activity and the HBM constructs was examined and the results showed that the self-efficacy of physical activity had a significant correlation with the constructs of the theory. Meanwhile, the correlation of the self-efficacy of physical activity with perceived barriers (r = 0.459) was stronger but with perceived susceptibility (r = 0.233) was weaker. As was predicted, perceived barriers had a significant negative correlation with the self-efficacy of physical activity. A significant negative correlation means that the fewer barriers to physical activity are, the more enhanced people's capability to maintain weight will be. Consistent with the results of this study, results of studies by Aghamolaei et al. on the self-efficacy of regular physical activity among university students in 2009[32] and Gharlipour Gharghani et al. on factors affecting regular physical activity among emergency medical personnel in 2011[33] demonstrated that there was a statistically significant relationship between perceived barriers and the self-efficacy of exercise. Furthermore, Da Costa and Ireland have reported in a study on regular physical activity among pregnant women in 2013[34] that perceived barriers could cause a reduction in the self-efficacy of physical activity. One of barriers to weight-maintenance behaviors during pregnancy might be their false belief about outcomes of the recommended behaviors. Studies show that, during pregnancy, pregnant women believe that physical activity is likely to cause miscarriage or adverse effects on the mother's health.[35,36] According to these results, it is necessary to identify mothers’ false beliefs about health-promotion behaviors during pregnancy and to propose different solutions for abandoning these beliefs. In this research, there was a significant positive correlation between perceived susceptibility and the self-efficacy of physical activity. Thus, the more susceptible a person feels to be to complications of a disregard for weight maintenance, the more the self-efficacy of weight-maintenance behaviors will be. In line with the findings of this study, Babazadeh et al. in a study on skin-cancer prevention behaviors in 2016[37] and Ghafari et al. in another study on determinants of physical activity among university students in 2014[38] reported that there was a significant relationship between perceived susceptibility and self-efficacy. These findings suggest that his self-efficacy increases if the person considers himself prone to outcomes of his own unhealthy behaviors. Women's perceived susceptibility to self-care behaviors during pregnancy has been reported in a study by Soleiman Ekhtiari et al.[39] Therefore, considering these results, it is recommended that emphasis be put on people's knowledge about outcomes of their own behaviors so as to improve their self-efficacy. There was a significant positive correlation between perceived severity and the self-efficacy of physical activity. This means that the more serious a person considers complications of a disregard for weight maintenance, the more the self-efficacy of weight-maintenance behaviors becomes. Confirming the findings of the present study, Babaei et al. in a study on brucellosis prevention behaviors[40] and Vazini and Baratiin another study on self-care behaviors of patients with type 2 diabetes[41] reported that there was a significant relationship between self-efficacy and perceived severity. According to findings of a study by Akbari et al.,[42] only 25.9% of pregnant women believed that a mother's obesity and overweight during pregnancy could lead to an overweight and obese infant. These results show that pregnant women have no considerable knowledge about the seriousness of complications resulting from overweight and affecting infants’ health. Hence, based on these findings, it is necessary to extend pregnant women's knowledge about complications of overweight and obesity and about the seriousness of their risk to infants’ health. According to the findings of this study, there was also a significant positive correlation between perceived benefits and the self-efficacy of physical activity for weight control in pregnancy. The positive correlation of perceived benefits with the self-efficacy of weight maintenance suggests that the more a person benefits from weight-maintenance behaviors, the more assured and capable he will be of weight-maintenance behaviors adopted. Consistent with the findings of the present study, Salahshoori et al. in a study on university students’ dietary behaviors in 2014[43] declared that there was a significant relationship between perceived benefits and self-efficacy. In a study, Ribiro and Milanez[44] demonstrated that the majority of pregnant women (65%) had a limited knowledge of physical activity during pregnancy. Moreover, according to findings of a study by Mahmoodi et al.,[45] pregnant women obtained the lowest score for physical activity among health-promoting behaviors. These results could suggest that pregnant women are unaware of benefits of health-promoting behaviors, particularly physical-activity behavior, during pregnancy. Therefore, highlighting benefits of healthy behaviors in educational interventions could play a key role in expanding people's capabilities to execute healthy behaviors. According to the linear regression analysis, the HBM constructs could predict 31% of changes in the self-efficacy of physical activity among pregnant women. Perceived barriers and perceived benefits of the predictors were significant among the examined constructs. Moreover, the strongest predictor of the self-efficacy of weight-maintenance behaviors was perceived barriers (β = 0.87) among the significant predictors. These findings indicate that the increase in benefits and decrease in barriers ought to be highlighted so as to promote the self-efficacy of physical activity. Confirming the findings of this study, Borowski and Tamblingin 2015[46] insisted on the increase in benefits and decrease in barriers. In another study on hepatitis B prevention behaviors in 2016,[47] Barzegar Mahmudi et al. showed that the constructs of the model could predict 31% of behavioral changes, which was in line with the results of the present study. Furthermore, in another study by Bishop et al. on patient-safety behavior in 2015,[48] the HBM constructs could predict 42% of behavioral changes in patients. These results revealed that the HBM as a suitable framework could be effective in predicting people's performance. Thus, it is recommended that this model be used as a framework for designing and implementing educational programs.

Conclusion

The findings of the present study revealed that the self-efficacy of physical activity among pregnant women was below average. Moreover, based on the results, the HBM constructs could predict 31% of changes in the self-efficacy of physical activity. Among the constructs, perceived benefits and perceived barriers of predictors were significant and the strongest factor was perceived barriers. Thus, in educational programs, using the HBM and emphasizing perceived benefits and perceived barriers could play an important role in promoting pregnant women's physical activity.

Limitations

One of limitations of this study was related to data collection. Data were collected through a questionnaire using a self-report method. Self-report behavior could lead to information bias.

Financial support and sponsorship

Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (GN: 393694).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for funding the survey (Grant Number: 393694).

References

- 1.Colón-Ramos U, Racette SB, Ganiban J, Nguyen TG, Kocak M, Carroll KN, et al. Association between dietary patterns during pregnancy and birth size measures in a diverse population in Southern US. Nutrients. 2015;7:1318–32. doi: 10.3390/nu7021318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo L, Liu J, Ye R, Liu J, Zhuang Z, Ren A. Gestational weight gain and overweight in children aged 3-6 years. J Epidemiol. 2015;25:536–43. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20140149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kazemian E, Sotoudeh G, Dorosty-Motlagh AR, Eshraghian MR, Bagheri M. Maternal obesity and energy intake as risk factors of pregnancy-induced hypertension among Iranian women. J Health Popul Nutr. 2014;32:486–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tielemans MJ, Erler NS, Leermakers ET, van den Broek M, Jaddoe VW, Steegers EA, et al. A Priori and a posteriori dietary patterns during pregnancy and gestational weight gain: The generation r study. Nutrients. 2015;7:383–99. doi: 10.3390/nu7115476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waring ME, Moore Simas TA, Xiao RS, Lombardini LM, Allison JJ, Rosal MC, et al. Pregnant women's interest in a website or mobile application for healthy gestational weight gain. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2014;5:182–4. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebrahimi F, Shariff ZM, Tabatabaei SZ, Fathollahi MS, Mun CY, Nazari M. Relationship between sociodemographics, dietary intake, and physical activity with gestational weight gain among pregnant women in Rafsanjan City, Iran. J Health Popul Nutr. 2015;33:168–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maslova E, Halldorsson TI, Astrup A, Olsen SF. Dietary protein-to-carbohydrate ratio and added sugar as determinants of excessive gestational weight gain: A prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e005839. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun D, Li F, Zhang Y, Xu X. Associations of the pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational BMI gain with pregnancy outcomes in Chinese women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:5784–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bjermo H, Lind S, Rasmussen F. The educational gradient of obesity increases among Swedish pregnant women: A register-based study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:315. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1624-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharp GC, Lawlor DA, Richmond RC, Fraser A, Simpkin A, Suderman M, et al. Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain, offspring DNA methylation and later offspring adiposity: Findings from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:1288–304. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardner RM, Lee BK, Magnusson C, Rai D, Frisell T, Karlsson H, et al. Maternal body mass index during early pregnancy, gestational weight gain, and risk of autism spectrum disorders: Results from a Swedish total population and discordant sibling study. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:870–83. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gesell SB, Katula JA, Strickland C, Vitolins MZ. Feasibility and initial efficacy evaluation of a community-based cognitive-behavioral lifestyle intervention to prevent excessive weight gain during pregnancy in latina women. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:1842–52. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1698-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farajzadegan Z, Bahrami D, Jafari N. Weight Gain during Pregnancy in Women Attending a Health Center in Isfahan City, Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:682–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seneviratne SN, McCowan LM, Cutfield WS, Derraik JG, Hofman PL. Exercise in pregnancies complicated by obesity: Achieving benefits and overcoming barriers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:442–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leiferman J, Swibas T, Koiness K, Marshall JA, Dunn AL. My baby, my move: Examination of perceived barriers and motivating factors related to antenatal physical activity. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2011;56:33–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2010.00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodrich K, Cregger M, Wilcox S, Liu J. A qualitative study of factors affecting pregnancy weight gain in African American women. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17:432–40. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1011-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agrahar-Murugkar D, Pal PP. Intake of nutrients and food sources of nutrients among the Khasi tribal women of India. Nutrition. 2004;20:268–73. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.George GC, Hanss-Nuss H, Milani TJ, Freeland-Graves JH. Food choices of low-income women during pregnancy and postpartum. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:899–907. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esmaillzadeh A, Samareh S, Azadbakht L. Dietary patterns among pregnant women in the West-North of Iran. Pak J Biol Sci. 2008;11:793–6. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2008.793.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson TD. Hypertension Beliefs and Behaviors of African Americans in Seleceted Cleveland Public Housing [PhD Thesis] USA: Kent State University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonds DE, Camacho F, Bell RA, Duren-Winfield VT, Anderson RT, Goff DC. The association of patient trust and self-care among patients with diabetes mellitus. BMC Fam Pract. 2004;5:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-5-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glance K, Marcus F, Barbara L. Health Behavior and Health Education (Theory, Research, Operation). Translator. Shafiei F. Tehran: Ladan Publication; 1997. pp. 68–84. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strecher VJ, Champion VL, Rosenstock IM, Gochman DS. The Health Belief Model and Health Behavior. 1th ed. New York: Plenum Press Publisher; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shojaezadeh D, Mehrabbaic A, Mahmoodi M, Salehi L. To evaluate of efficacy of education based on health belief model on knowledge, attitude and practice among women with low socioeconomic status regarding osteoporosis prevention. Iran J Epidemiol. 2011;7:30–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Azadbakht M, Garmaroudi GH, Taheri Tanjani P, Sahaf R, Shojaeijadeh D, Gheisvandi E. Health promoting self-care behaviors and its related factors in elderly: Application of health belief model. J Educ Community Health. 2014;1:2–29. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saunders GH, Frederick MT, Silverman SC, Nielsen C, Laplante-Lévesque A. Description of adults seeking hearing help for the first time according to two health behavior change approaches: Transtheoretical model (stages of change) and health belief model. Ear Hear. 2016;37:324–33. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doak CC, Doak LG, Root Jane H. Teaching Patients with Low Literacy Skills. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Co; 1996. pp. 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shannon J, Kirkley B, Ammerman A, Keyserling T, Kelsey K, DeVellis R, et al. Self-efficacy as a predictor of dietary change in a low-socioeconomic-status Southern adult population. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:357–68. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peyman N, Ezzati Rastegar KH. Effect of an educational program on job tension management in nurses, based on self-efficacy theory. Modern Care Sci Quart Birjand Nurs Midwifery Faculty. 2012;9:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy DA, Stein JA, Schlenger W, Maibach E National Institute of Mental Health Multisite HIV Prevention Trial Group. National Institutes of Health. Conceptualizing the multidimensional nature of self-efficacy: Assessment of situational context and level of behavioral challenge to maintain safer sex. National Institute of Mental Health Multisite HIV Prevention Trial Group. Health Psychol. 2001;20:281–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarkar U, Fisher L, Schillinger D. Is self-efficacy associated with diabetes self-management across race/ethnicity and health literacy? Diabetes Care. 2006;29:823–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.04.06.dc05-1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aghamolaei T, Tavafian SS, Hasani L. Exercise self-efficacy, exercise perceived benefits and barriers among students in Hormozgan University of medical sciences. Iran J Epidemiol. 2009;4:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gharlipour Gharghani Z, Sayarpour SM, Moeini B. Associated factors with regular physical activity among emergency medical personnel in Hamadan: Applying health belief model. J Health Syst. 2011;7:710–7. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Da Costa D, Ireland K. Perceived benefits and barriers to leisure-time physical activity during pregnancy in previously inactive and active women. Women Health. 2013;53:185–202. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2012.758219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Solhi M, Ahmadi L, Taghdisi MH, Haghani H. The Effect of Trans Theoretical Model (TTM) on exercise behavior in pregnant women referred to Dehaghan Rural health center in. Iran J Med Educ. 2012;11:942–50. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evenson KR, Moos MK, Carrier K, Siega-Riz AM. Perceived barriers to physical activity among pregnant women. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13:364–75. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0359-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Babazadeh T, Nadrian H, Banayejeddi M, Rezapour B. Determinants of skin cancer preventive behaviors among rural farmers in Iran: An application of protection motivation theory. J Cancer Educ. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s13187-016-1004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghafari M, Nasirzadeh M, Aligol M, Davoodi F, Nejatifar M, Kabiri S, et al. Determinants of physical activity for prevention of osteoporosis among female students of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences: Application of health belief model. Pajoohandeh J. 2014;19:244–50. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soleiman Ekhtiari Y, Majlessi F, Rahimi Foroushani A. Measurement of the constructs of health belief model related to self-care during pregnancy in women referred to South Tehran health network. Community Health. 2015;1:89–98. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Babaei V, Babazadeh T, Kiani A, Garmaroodi G, Batebi A. The role of effective factors in preventive behaviors of brucellosis in stockbreeder of Charaoymaq County: A health belief model. J Fasa Univ Med Sci. 2016;5:470–8. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vazini H, Barati M. Predicting factors related to self-care behaviors among type 2 diabetic patients based on health belief model. J Torbat Heydariyeh Univ Med Sci. 2014;1:16–25. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akbari Z, Tol A, Shojaeizadeh D, Aazam K, Kia F. Assessing of physical activity self-efficacy and knowledge about benefits and safety during pregnancy among women. RJMS. 2016;22:76–87. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salahshoori A, Sharifirad G, Hassanzadeh A, Mostafavi F. An assessment of the role of perceived benefits, barriers and self-efficacy in predicting dietary behavior in male and female high school students in the city of Izeh, Iran. J Educ Health Promot. 2014;3:8. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.127558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ribeiro CP, Milanez H. Knowledge, attitude and practice of women in Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil with respect to physical exercise in pregnancy: A descriptive study. Reprod Health. 2011;8:31. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mahmoodi H, Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Babazadeh T, Mohammadi Y, Shirzadi S, Sharifi-Saqezi P, et al. Health promoting behaviors in pregnant women admitted to the prenatal care unit of Imam Khomeini Hospital of Saqqez. J Educ Community Health. 2015;1:58–65. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Borowski SC, Tambling RB. Applying the health belief model to young individuals’ beliefs and preferences about premarital counseling. Fam J. 2015;23:417–26. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barzegar Mahmudi T, Khorsandi M, Shamsi M, Ranjbaran M. Knowledge, Beliefs and Performance of health volunteers in Malayer city about Hepatitis B: An application of health belief model. Pajouhan Sci J. 2016;14:24–33. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bishop AC, Baker GR, Boyle TA, MacKinnon NJ. Using the health belief model to explain patient involvement in patient safety. Health Expect. 2015;18:3019–33. doi: 10.1111/hex.12286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]