Significance

Acute infection with intracellular pathogen results in the expansion and effector differentiation of pathogen-specific CD8+ T cells, most of which die after pathogen clearance. The factors and steps controlling CD8+ T cell differentiation in response to acute infection are not fully understood. We find FOXO1 and TCF7 drive postinfection immune memory characteristics in cells expressing low TIM3, where TCF7 actively down-regulates the cytotoxic molecule GZMB and reduces terminally differentiated KLRG1high effector abundance. We further report the creation of a continuum of CD8+ T cell phenotypes, ranging from terminal effector cells to long-lived immune-memory cells, dependent on FOXO1 and TCF7. We conclude FOXO1 and TCF7 are essential to oppose cytotoxic/terminal differentiation programs and enable full phenotypic diversity of postinfection CD8+ T cells.

Keywords: immunology, host, pathogen, CD8+ T cell, immune memory

Abstract

The factors and steps controlling postinfection CD8+ T cell terminal effector versus memory differentiation are incompletely understood. Whereas we found that naive TCF7 (alias “Tcf-1”) expression is FOXO1 independent, early postinfection we report bimodal, FOXO1-dependent expression of the memory-essential transcription factor TCF7 in pathogen-specific CD8+ T cells. We determined the early postinfection TCF7high population is marked by low TIM3 expression and bears memory signature hallmarks before the appearance of established memory precursor marker CD127 (IL-7R). These cells exhibit diminished TBET, GZMB, mTOR signaling, and cell cycle progression. Day 5 postinfection, TCF7high cells express higher memory-associated BCL2 and EOMES, as well as increased accumulation potential and capacity to differentiate into memory phenotype cells. TCF7 retroviral transduction opposes GZMB expression and the formation of KLRG1pos phenotype cells, demonstrating an active role for TCF7 in extinguishing the effector program and forestalling terminal differentiation. Past the peak of the cellular immune response, we report a gradient of FOXO1 and TCF7 expression, which functions to oppose TBET and orchestrate a continuum of effector-to-memory phenotypes.

Intracellular pathogens are sequestered from a multitude of innate and humoral immune defenses; however, CD8+ T cells provide a mechanism for their antigen-specific clearance via recognition of intracellular-derived peptides presented on MHC class I molecules. Acute infection and subsequent priming by antigen-presenting cells result in the massive expansion of pathogen-specific CD8+ T cells, the majority of which die by apoptosis within weeks after antigen clearance. A subset of responding CD8+ T cells differentiates into long-lived memory cells, which are maintained in equilibrium with the total lymphocyte pool via homeostatic proliferation, and have abundant proliferative and differentiation potential. These properties confer durable and transferable host protection to pathogen rechallenge (1).

The molecular programming of CD8+ T cell differentiation has been extensively investigated, and many events that specify terminal effector vs. memory precursor cells have been described (2–4). Although several models of T cell memory exist, available evidence indicates that all cells of a given TCR have a similar capacity to form (or not form) memory cells immediately postactivation (5). An important question yet to be fully answered is the composition of the molecular switch or series of molecular switches that program the terminal differentiation vs. memory fate characteristics of individual T cells (3).

Previous studies determined the HMG-box–containing transcription factor 7 (TCF7) [National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) ID 21414; also known as T cell factor one (Tcf-1)] is essential for the establishment of T cell memory (6, 7). Further studies showed that FOXO1 is essential for CD8+ T cells to become memory cells postactivation (8–11), and TCF7 expression postactivation is dependent on FOXO1 (8). However, multiple aspects of early and postpeak CD8+ T cell differentiation downstream of FOXO1 have not been explored. In this report, we show that, whereas FOXO1 is dispensable for naive T cell expression of TCF7, it is essential for the expression of TCF7 in a small subset of T cells within days following primary infection. We found the emergent TCF7-expressing population could be identified by decreased abundance of TIM3, and it exhibited diminished hallmarks of effector cells, including granzyme B (GZMB) and TBET. Enforced TCF7 played an active role in decreasing GZMB expression and reducing KLRG1+ cell abundance. Past the peak of infection, we found FOXO1-positive regulation of TCF7 and opposition of TBET is essential for full phenotypic diversity during the CD8+ T cell immune response to acute infection—orchestrating a continuum of cellular differentiation phenotypes, from terminal effector to memory precursor.

Results

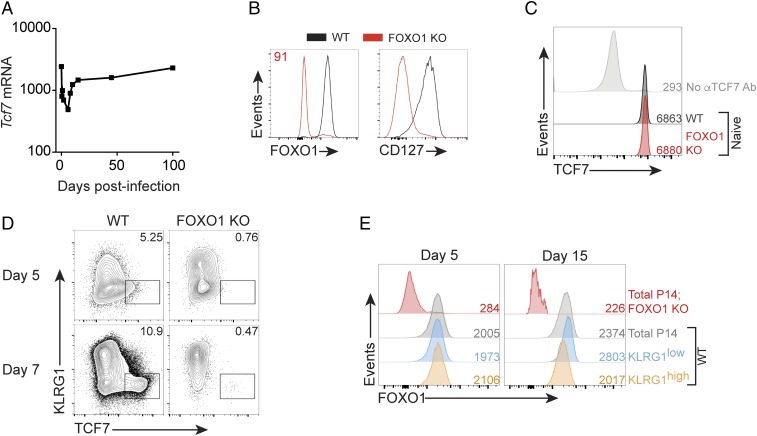

Naive CD8+ T Cell TCF7 Expression Is FOXO1 Independent.

TCF7 is essential for early T cell specification in the thymus (12, 13) and functional CD8+ T cell memory (6, 7). Tcf7 mRNA is highly expressed in naive cells, and then, upon activation of pathogen-specific cells during infection, it is rapidly down-regulated, only to be again expressed in memory T cells (Fig. 1A) (14). FOXO1 is also essential for memory T cell function and is required for postactivation expression of TCF7 (8–10). First, we verified efficient deletion of Foxo1: >90% of naive Foxo1f/f/dLck-cre+/− P14+/− CD8+ T cells did not express FOXO1 protein, and we observed marked down-regulation of FOXO1 target CD127 (Fig. 1B). We then tested whether FOXO1 was required for TCF7 protein expression in naive CD8+ T cells and found naive Foxo1f/f/dLck-cre+/− P14+/− T cells express the equivalent high amounts of TCF7 found in WT P14 T cells (Fig. 1C; Foxo1f/f/dLck-cre+/− hereafter referred to as “FOXO1 KO”).

Fig. 1.

Naive CD8+ T cell TCF7 expression is FOXO1 independent. (A) Tcf7 mRNA abundance in antigen-specific OT-I CD8+ T cells responding to acute infection with Listeria monocytogenes-OVA; primary data are from GSE15907. (B) FOXO1 and CD127 protein abundance in naive splenic WT P14 and naive Foxo1f/f/dLck-cre+/− (FOXO1 KO) P14 T cells. Inset indicates percentage of FOXO1 KO P14 cells low for FOXO1 protein. Representative experiment of two. (C) Naive (CD44low) WT P14 and FOXO1 KO P14 splenic CD8+ T cells were immunostained for TCF7. Inset numbers indicate TCF7 geometric mean fluorescence intensity (gMFI). Performed three times with similar results. (D) A 1:1 mix of WT P14 and FOXO1 KO P14 cells (1 × 104 total) were transferred into WT mice at day −1, and hosts were infected with LCMV-ARM on day 0. P14 cells were immunostained on days shown; Inset indicates percentage in gate. FOXO1-negative cells plotted for KO. Representative experiment of two. (E) FOXO1 immunostaining of KLRG1 subsets in P14 cells at days 5 and 15 postinfection; from a different experiment from that in D. Inset numbers indicate gMFI; experiment representative of two.

FOXO1-Dependent, Bimodal TCF7 Expression in Postinfection CD8+ T Cells.

P14 TCR-transgenic CD8+ T cells recognize a C57BL/6 immunodominant epitope of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) glycoprotein-1 (GP1), allowing adoptive transfer of specific numbers of LCMV-specific, naive CD8+ T cells to C57BL/6 recipient mice (15). We performed a mixed WT P14 and FOXO1 KO P14 adoptive transfer to determine the kinetics of TCF7 expression in P14 T cells after acute infection with LCMV-Armstrong (LCMV-ARM). Relative to WT, we found that the TCF7high population was markedly reduced in FOXO1 KO T cells at days 5 and 7 postinfection (Fig. 1D). These data show that FOXO1 is required for the majority of TCF7 expression by day 5 postinfection. Because FOXO1 is essential for T cell memory responses and is less abundant in KLRG1high cells at day 7 postinfection (8–10), we investigated whether FOXO1 abundance could predict CD8+ T cell memory precursor phenotype cells at day 5 postinfection. In contrast to day 15 postinfection where differences were apparent, on day 5 postinfection we found total FOXO1 abundance was indistinguishable between KLRG1low and KLRG1high cells (Fig. 1E). Therefore, total FOXO1 abundance could not be used to discern early memory precursors at day 5 postinfection.

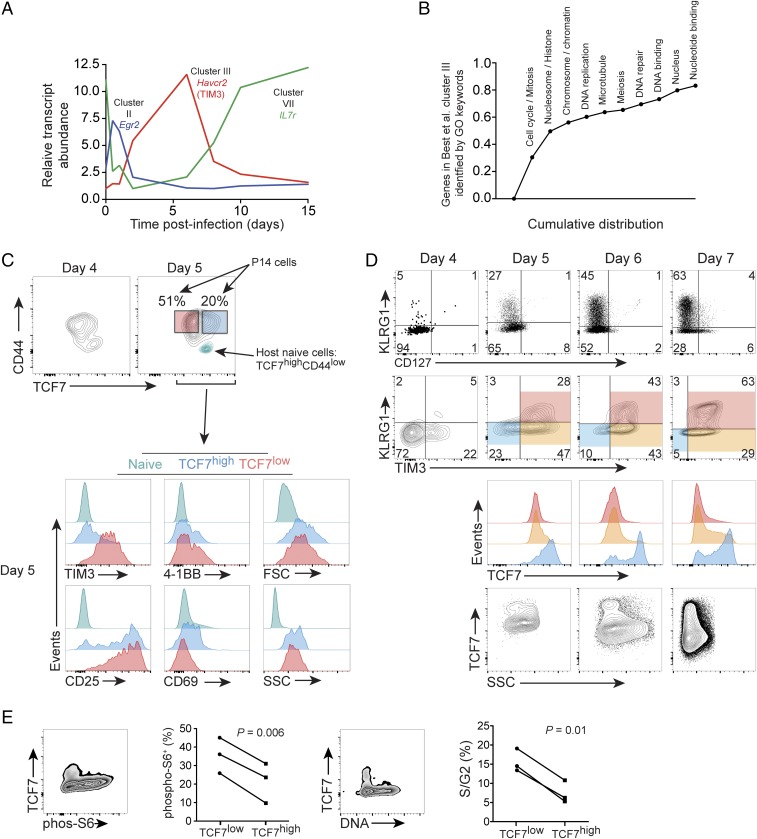

Low TIM3 Marks the Postinfection TCF7high Population.

Large-scale bioinformatics projects have identified the changes in gene expression in CD8+ T cells responding to infection (16, 17). By grouping similar gene expression patterns in response to infection, the Immgen Project identified 10 clusters of dynamically regulated genes in a time course of CD8+ T cells responding to acute infection (selected genes presented in Fig. 2A) (16). We reasoned these data would allow for identification of cell surface markers which accompany early steps in memory differentiation or terminal differentiation. Retrospective analysis of gene expression in early postinfection CD8+ T cell differentiation, before the expression of KLRG1, revealed the enrichment of cluster III transcripts in cell populations that were likely to become terminally differentiated KLRG1high cells (16). Cluster III, comprising 251 unique genes, does not contain prototypical terminal effector vs. memory precursor regulators, but rather genes associated with cell cycle progression and proliferation (Fig. 2B). Given that the peak expression of cluster III gene set takes place from approximately day 2 to day 5 postinfection, near the time that terminal effector vs. memory precursor decisions occur, we wondered whether cell surface markers contained within cluster III could reveal an early, nontraditional marker of pathogen-specific CD8+ T cells likely to become terminally differentiated.

Fig. 2.

Low TIM3 marks the postinfection TCF7high population. Ten clusters of dynamically regulated genes in a time course of CD8+ T cells responding in vivo to infection were identified by Best et al. (16); primary data are from GSE15907. (A) Kinetics of gene expression of selected transcripts from cluster II, III, and naive/memory-associated cluster VII; cell surface molecule TIM3 (Havcr2) pertains to cluster III. (B) Greater than 80% of genes in cluster III were tagged with one or more of the GO identifiers listed; genes in cluster III were screened for the identifiers in the order listed Left to Right, resulting in a cumulative distribution. (C–E) A total of 1 × 104 P14 cells was adoptively transferred to WT host mice on day −1 and was infected with LCMV-ARM on day 0. (C, Above) Day 4 and day 5 postinfection P14 expression of TCF7 and CD44. For day 5, the naive host CD8+ population (CD44low) from the same sample is plotted in teal for intrasample reference of high TCF7 and low CD44. (Below) The expression of indicated proteins, FSC-A and SSC-A, on day 5 using the color-coded gates established in the day 5 contour plot above. (D) CD127 and TIM3 vs. KLRG1 on total P14 cells from day 4 to 7 postinfection. TCF7 expression within the indicated shaded gates is then plotted below. Total P14 SSC-A vs. TCF7 for indicated days is shown below. Where present, Insets indicate the percentage of the gated population. Note absolute values of immunofluorescence may vary among days, as immunostaining was performed independently each day. Experiments in C and D performed twice with similar results. (E) Gates were established on the P14+KLRG1− adoptively transferred cells, and immunostaining for phospho-S6 or determination of DNA content with DRAQ5 was performed at day 6–7 postinfection. The percent positive for phospho-S6 or in S/G2 of the cell cycle was determined; n = 3, three independent experiments, Student’s paired t test.

Within cluster III, TIM3 (Havcr2) was judged to be the most promising among six genes encoding cell surface proteins—markers that might be readily used to distinguish effector vs. memory precursor cells. In agreement with the Immgen data, we further established that TIM3 is most highly expressed from day 5 to day 6 postactivation (Fig. S1). TIM3 is poorly expressed at day 4 when nearly all cells were CD25+, and when the majority of cells exhibited detectable expression of early activation markers 4-1BB, CD69, and LAG3 (Fig. S1). We found that, on day 5 postactivation, the absence of TIM3, but not of 4-1BB, CD25, or CD69, correlated with TCF7 expression (Fig. 2C). By day 5–6 postinfection, as predicted by the association of cluster III with terminal differentiation, we found that it was possible to identify the postinfection TCF7high subset by gating on TIM3lowKLRG1low cells (Fig. 2D). We further tested 17 cell surface proteins associated with activation for correlation with known memory precursor protein ID3 (18, 19), and found TIM3 to best inversely correlate with ID3high P14 cells (Fig. S2). Based on the results from Fig. 2 and Figs. S1 and S2, we hypothesized that TIM3 would provide a readily determined, cell surface assessment of a sustained cellular activation and proliferation signature key to terminal differentiation, inverse to that of TCF7 expression, and thus would mark cells likely to become terminally differentiated.

Fig. S1.

Activation marker regulation on virus-specific CD8+ T cells responding to LCMV-Armstrong infection. A total of 1 × 104 P14 cells was transferred into WT hosts on day −1 and hosts were infected with LCMV-Armstrong on day 0. (Top) Activation markers vs. CD44 on days 4–7 postinfection. “Large dot” plots were used for day 4 to allow visualization of limited events. (Bottom) As above, but plotting vs. KLRG1. Insets (in corners) indicate quadrant percentages. Centered Insets indicate the gMFI of indicated marker for KLRG1low (Center Bottom) or KLRG1high (Center Top). Results are representative of three experiments.

Fig. S2.

Early postinfection virus-specific ID3high cells are TIM3low. Previous results demonstrated cells expressing high ID3 and low ID2 postinfection had increased memory potential (18) and that ID3 was associated with and could drive memory cell formation (19). A total of 1 × 104 ID3GFP+/− P14 cells was transferred into WT hosts at day −1 and hosts were infected with LCMV-Armstrong on day 0. Splenocytes were analyzed at day 6 postinfection. (A, Left) A congenic marker-positive, P14+CD127negKLRG1neg EEC gate was established, along with a subsequent gate for ID3 GFP positivity. (Right) Depicted are host naive CD44low congenic marker negative (dark gray), ID3GFP+/− GFP-negative P14 EEC (light blue), and ID3GFP+/− GFP-positive P14 EEC (green). The TCF7 staining protocol quenched the GFP reporter; therefore, TCF7 vs. ID3 was not performed. All stains for the proteins indicated in A, Right, were performed using phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated antibodies; FMO indicates fluorescence minus one, where all fluorescent antibodies were present except for PE. (B) Correlation of cell surface marker expression with ID3 expression (on the same data as that in A) was performed as follows: a histogram marker gate for expression was established on KLRG1lowID3high and KLRG1lowID3low using the FMO control on day 6 postinfection. The percent KLRG1lowID3high or KLRG1lowID3low cells expressing the marker were then plotted. Note that, of the markers tested, the lack of TIM3 expression was most accurate at correlating with ID3 expression, as shown by the location of TIM3 in the Top Left of the plot in B. Results representative of two experiments.

TCF7high Cells Have Increased Accumulation and Differentiation Potential.

Using the absence of cell surface TIM3 to identify the TCF7high population, we sorted TIM3lowKLRG1low, TIM3highKLRG1low, and KLRG1high P14 cells from WT hosts at day 5 postinfection with LCMV-ARM, as indicated in Fig. S3A. We then transferred ∼1 × 104 cells of these sorted populations into infection-matched recipients. On day 17, we isolated splenocytes from the infection-matched recipient mice and immunostained to identify the transferred cells. We found the transferred TIM3lowKLRG1low cells had increased capacity to form CD127highKLRG1low memory precursor cells, and greater than 10-fold more were recovered compared with the transfer of TIM3highKLRG1low cells (Fig. S3 B and C). As a control, we also sorted and transferred CD127lowKLRG1high cells, which are known to have poor proliferative potential and to be largely terminally differentiated (20). As expected, CD127lowKLRG1high cells did not accumulate well vs. TIM3lowKLRG1low cells, and as with TIM3highKLRG1low cells, ∼10-fold fewer were recovered vs. the TIM3lowKLRG1low population. These data are consistent with the TIM3lowKLRG1low population, which is highly enriched for postinfection TCF7high cells, possessing increased accumulation and differentiation potential.

Fig. S3.

The postinfection TIM3low population exhibits increased accumulation and memory-precursor differentiation potential. A total of 1 × 104 P14 cells was transferred into WT hosts on day −1 and hosts were infected with LCMV-Armstrong on day 0. (A) Experimental diagram for infection-matched, adoptive transfer of P14 cells. (B) Fold increase of adoptively transferred cells recovered from spleens of infection-matched recipients at day 17 relative to those transferred in at day 5 postinfection. Note designation as “(a),” “(b),” or “(c)” corresponds to color-coded sorted populations in A. (C) Cell surface CD127/KLRG1 phenotype of cells recovered at day 17 postinfection. Experiment performed once with n as shown in A; P values are from Student’s unpaired t test. Error bars indicate SEM.

The light-scattering properties of cells comprising the TCF7high vs. TCF7low population were similar at day 5, and then decreased in the TCF7high subset at day 6 and remained lower at day 7 postinfection (Fig. 2 C and D). Along with CD44 (Fig. 2C and Fig. S1), these data are consistent with TCF7high cells having undergone activation and blastogenesis by day 5, and then dropping out of the cellular growth and proliferation program from day 6 to 7.

Previous studies have shown that mTORC1 (21, 22) and cell cycle progression (4) are associated with CD8+ T cell terminal differentiation. We hypothesized that mTOR, a regulator of anabolic pathways and growth via its control of protein translation and ribosome biogenesis (23), would be lower in TCF7high cells. In adoptively transferred P14 cells at day 7 postinfection, we gated on KLRG1− cells and stained for TCF7 and mTOR target phospho-ribosomal protein S6 (p-S6). We found that postinfection TCF7high cells had lower p-S6 than TCF7low cells (Fig. 2E). To assay for changes in cell cycle, we stained for total DNA content and found TCF7high cells were less likely to be in S or G2 in the cell cycle (Fig. 2E). We also found CD25-, GZMB-, and TIM3-negative cells, which are enriched for the TCF7high population, contained fewer cells incorporating BrdU (Fig. S4) and exhibited decreased side light scatter (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these data revealed that the postinfection TCF7high population exhibited less cellular growth and proliferation, as indicated by decreased mTOR activity, light scattering, S/G2 positivity, and BrdU incorporation.

Fig. S4.

Day 5.5 postinfection CD25low, GZMBlow, and TIM3low subsets contain a prominent BrdUneg fraction. A total of 1 × 104 P14 cells was transferred into WT hosts at day −1 and hosts were infected with LCMV-Armstrong on day 0. P14 splenocytes were analyzed at day 5.5 postinfection after a 6-h in vivo pulse with BrdU. The 103 fluorescence for BrdU is indicated on axes and was used as the approximate threshold for BrdU positivity. (Left) Indicated activation markers vs. BrdU. (Center Left) Gates on activation marker vs. KLRG1. (Center Right) BrdU histograms on gated populations, and (Right) percent positive of the populations. This experiment was performed once; n = 2.

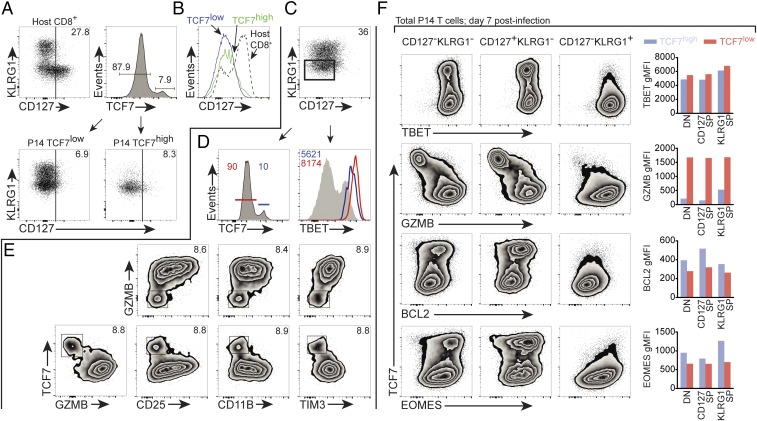

TCF7high EEC Exhibit Memory Precursor Phenotype.

We have shown the absence of TIM3 expression marks TCF7high phenotype cells on days 5–7 postinfection (Fig. 2C), and furthermore, this population has superior accumulation and differentiation capacity (Fig. S3). These data suggest that TCF7 (and the lack of TIM3) is marking the emergent memory precursor population.

As CD127 is an established marker for postinfection CD8+ memory precursor T cells (24), we set out to test whether differential TCF7 and TIM3 expression preceded CD127 in emerging memory phenotype T cells. First, we gated on host CD8+ T cells as a positive control for CD127 immunostaining (Fig. 3A, Top Left). Then, gating on TCF7low and TCF7high P14 T cells on day 6 following LCMV-ARM infection, we found these populations expressed similarly low levels of CD127, whether viewed by dot plot vs. KLRG1 (Fig. 3A; below) or via histogram of CD127 (Fig. 3B). These data indicate that, at day 6 postinfection, there is a significant pathogen-specific population expressing abundant TCF7 in the absence of cell surface CD127.

Fig. 3.

TCF7high EEC exhibit memory precursor phenotype. A total of 1 × 104 P14 cells was adoptively transferred to WT host mice on day −1 and hosts were infected with LCMV-ARM on day 0. (A and B) Total P14 TCF7high and TCF7low cells on day 6 postinfection express similarly low CD127, viewed by either (A) dot plot vs. KLRG1 or (B) histogram; note positive control of total host CD8+ T cells. P14 TCF7low (solid, blue); P14 TCF7high (solid, green); total host CD8+ cells (dotted, black). (C–E) A congenic marker-positive, P14+CD127lowKLRG1low early effector cell (EEC) gate was established (C) and used for D and E. (D) TCF7 and TBET immunostaining on P14 EEC. Histogram at Right depicts TBET abundance in TCF7low (red trace corresponds to red marker population at Left) and TCF7high (blue trace corresponds to blue marker population at Left) subsets. For reference, gray filled trace at Right depicts TBET abundance in host splenic CD4−CD8α−, a population which contains both TBET+ and TBET− cells. (E) The TCF7high fraction is GZMBlow, CD25low, CD11Blow, and TIM3low. Where present, Inset indicates percentage of gated population, except in D, Right, where Inset indicates gMFI of TBET. (F) Expression of indicated proteins was determined on P14+ cells gated on indicated CD127/KLRG1 populations on day 7 postinfection; bar graphs depict gMFI for indicated proteins in CD127/KLRG1 populations further subsetted for TCF7high vs. TCF7low. Blue bars depict TCF7high-gated cells, while red bars depict TCF7low-gated cells. Representative sample of three independent experiments. Data in D and E are from different experiments, where the EEC gate varied from 36% in D to 38% in E.

Naive CD8+ T cells exhibit a CD127highKLRG1low phenotype, but within the first few days postinfection, the vast majority of antigen-specific cells have the phenotype CD127lowKLRG1low (24). While debate still exists in the field, available evidence suggests that from this pathogen-specific CD127lowKLRG1low “early effector cell” (EEC) population emerges single-positive CD127lowKLRG1high (terminal effector) and CD127highKLRG1low (memory precursor) cells (3, 20, 24). We established an EEC gate on adoptively transferred P14 T cells at day 6 postinfection with LCMV-ARM (Fig. 3C) and analyzed TCF7 expression. We found that P14 EEC included populations that were clearly positive and negative for TCF7 (Fig. 3D, Left). We have shown postinfection P14 cells are CD44high by day 6 postinfection (Fig. 2C and Fig. S1), and we verified they were Vα2 TCR+ (Fig. S5A), which is consistent with postactivation, P14 TCR-transgenic EEC.

Fig. S5.

Properties of TCF7low and TCF7high postinfection, pathogen-specific cells. A total of 104 P14 T cells was transferred at day −1 to WT hosts and hosts were infected on day 0 with LCMV-Armstrong. (A) Vα2+ vs. TCF7 immunostaining on P14 EEC, day 6 postinfection. (B) Day 5 postinfection TCF7 vs. GZMB staining of total CD8+ (including host non–pathogen-specific cells; black) and transferred virus-specific P14 cells (green). (C) Total P14 cells at indicated day postinfection subdivided into TCF7high and TCF7low gates. (D) Immunophenotype of TCF7low and high cells at days postinfection indicated in C. Day 5 negative control for GZMB is gated on total CD8+ cells (including pathogen-specific and non–pathogen-specific host cells) from the same immunostain. (E) Graphical display of immunophenotype of transferred P14 T cells. (Left) TCF7pos of the total P14 gate (black), TCF7low of KLRG1high gate (red), and TCF7high of KLRG1low gate (blue); (Center Left) TIM3 positivity of TCF7neg (red) and TCF7pos gates (blue). (Center Right) KLRG1 positivity of TCF7low (red) and TCF7high gates (blue). (Right) GZMB positivity of TCF7low (red), TCF7high (blue) gates. These results are representative of two independent experiments.

We determined whether differential TBET expression could be detected in TCF7high and TCF7low EEC, as postinfection memory precursor cells express lower TBET vs. terminally differentiated cells (20). TBET is essential to CD8+ T cell effector differentiation and function (25), and previous studies have demonstrated that graded expression of this factor controls terminal effector vs. memory precursor differentiation: high TBET results in more KLRG1high terminally differentiated cells, whereas lower TBET results in more CD127high memory precursor cells (20, 26). Furthermore, small changes in TBET abundance have been associated with CD8+ T cells with distinct effector vs. memory identities (26). Consistent with this, we found that the putative memory precursor EEC TCF7high population exhibited diminished TBET vs. TCF7low cells (Fig. 3D).

Studies have shown that GZMB abundance and cytotoxic capacity are comparable between KLRG1high and KLRG1low cells at day 3.5 postinfection (4). However, at day 12 and day 19 postinfection, CD127highKLRG1low memory precursor cells have less abundant GZMB expression vs. KLRG1high cells, which maintain moderately elevated GZMB expression (8). In day 6 TCF7high EEC, we found low GZMB (Fig. 3E), consistent with the eventual phenotype adopted by CD127highKLRG1low memory precursor cells. Further analysis demonstrated that all P14 cells were GZMB+ at day 5, but rapidly transitioned to TCF7highGZMBlow and TCF7lowGZMBhigh subsets 1 d later (Fig. S5 B–E).

CD25, the α-chain of the high-affinity IL-2 receptor, is expressed on all P14 cells at approximately day 4–5 postinfection with LCMV-ARM (Fig. S1) (27). A previous study showed that CD8+ T cells which exhibit prolonged expression of CD25 are more likely to become terminally differentiated KLRG1high cells (27). Although at day 5 nearly all P14 cells were CD25high (Fig. 2C and Fig. S1), at day 6, we observed that P14 TCF7high EEC are CD25low (Fig. 3E). Notably, not all CD25low cells are TCF7high; hence reduced CD25 expression is not sufficient to identify TCF7high cells (Fig. 3E). Neutrophil and macrophage-associated CD11B is also expressed by a subset of postactivation CD8+ T cells (28), and we found that the P14 EEC TCF7high population expressed low amounts of CD11B. Finally, we observed that the expression of TIM3 is inversely associated with TCF7 within the EEC population (Fig. 3E), as it was in total postinfection P14 T cells (Fig. 2D). In summary, in postinfection, pathogen-specific CD8+ P14 cells, we have found high TCF7 abundance at day 6–7 postinfection correlates with diminished TIM3, CD11B, CD25, GZMB, and TBET in the poorly understood CD127−KLRG1− (EEC) population. These data are consistent with FOXO1-driven TCF7 expressed in cells destined to become memory cells, before the expression of CD127.

After characterizing day 6 expression of TCF7 in EEC, we set out to determine how TCF7high and TCF7low P14 populations differed at the peak of the cellular response to LCMV-ARM, approximately 7 d postinfection, within subsets delineated by the expression of CD127 and KLRG1. We found that, within CD127−KLRG1−, CD127+KLRG1−, and CD127−KLRG1+ subsets, TCF7 correlated with increased BCL2 and EOMES and decreased TBET and GZMB (Fig. 3F). Therefore, FOXO1-driven TCF7 is associated with diminished effector and increased memory phenotype in all day 7 postinfection CD127/KLRG1 subsets tested.

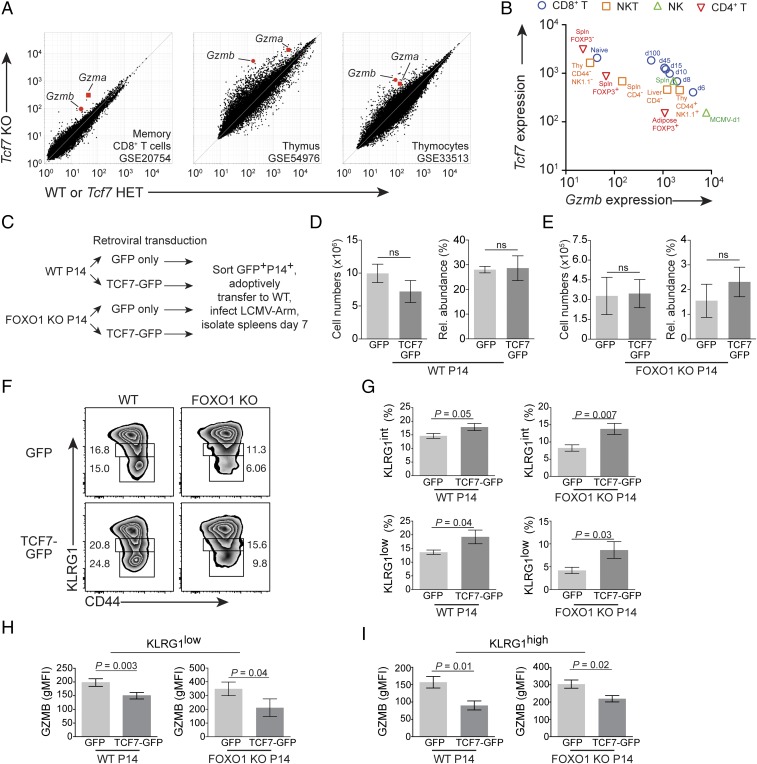

Tcf7 Transduction Forestalls Terminal Differentiation and Diminishes GZMB.

As we observed that TCF7 protein expression was reciprocal to GZMB (Fig. 3 E and F), we wondered whether this was also the case at the level of transcription. In three different microarray studies of Tcf7-deficient T cells, Gzma and Gzmb were found to be among the most highly up-regulated transcripts (Fig. 4A; primary data from refs. 6, 29, and 30). Postinfection FOXO1 KO P14 cells, which poorly express TCF7, also exhibited elevated GZMB abundance (8). We next set out to investigate whether this relationship existed beyond T cells: indeed, we observed an inverse relationship between Tcf7 and Gzmb in natural killer (NK), NKT, and CD4+ T cell lineages (Fig. 4B; primary data from ref. 31).

Fig. 4.

Tcf7 forestalls phenotypic terminal differentiation and opposes immune cell Gzmb. (A) Gzma and Gzmb expression in three published microarray studies containing Tcf7 mutant CD8+ T cells. (Left) Peripheral, postinfection memory CD8+ T cells; (Center) thymus; and (Right) mouse DN1 stage thymocytes (Lin− CD44+CD25−KIT+). Inset summarizes cell type and NCBI GEO accession number. (B) Plot of Gzmb vs. Tcf7 gene expression; color/shape indicate cell type. Note further annotation in plot (i.e., CD44, NK1.1), tissue/organ (i.e., adipose, spleen), or infection (i.e., MCMV, day 1 postinfection shown for NK cells responding to MCMV). For CD8+ T cells, d6, d8, d10, d15, d45, and d100 indicate days postinfection with Listeria monocytogenes-OVA. Primary data in B are from GSE15907. (C) Experimental diagram for retroviral transduction. (D–I) WT P14 GFP+-gated and FOXO1 KO P14+GFP+-gated cell numbers and phenotypes following protocol in C. Cell number and relative abundance of (D) WT and (E) FOXO1 KO. Representative KLRG1 immunophenotype with (F) KLRG1low and KLRG1int gates shown, and (G) pooled KLRG1 phenotype data. GZMB expression in (H) KLRG1low and (I) KLRG1high P14 cells. Error bars are SEM; P values are from Student’s unpaired t test. GFP, n = 9; WT GFP-TCF7, n = 7; FOXO1 KO GFP, n = 7; FOXO1 KO GFP-TCF7, n = 6. Retroviral transduction and TCF7-dependent decrease in GZMB were observed three times; pooled data are from three independent experiments plotted in G–I.

To address whether TCF7 expression could drive lower GZMB expression, we used retroviral GFP or TCF7-GFP vectors to transduce P14 cells, and then challenged them in vivo with LCMV-ARM infection (Fig. 4C). TCF7 transduction did not alter cellular number or relative abundance of transduced P14 cells vs. GFP alone (Fig. 4 D and E). We first examined KLRG1 phenotype of the GFP vs. TCF7-GFP transduced cells, and found that forced expression of TCF7 reduced the relative abundance of KLRG1high cells and increased the percentage of KLRG1int and KLRG1low cells; this effect occurred in both WT and FOXO1 KO cells (Fig. 4 F and G).

We next determined whether forced TCF7 expression would lower GZMB abundance in effector CD8+ T cells in vivo. Controlling for KLRG1 phenotype, we found that TCF7-GFP retroviral transduction, but not control GFP transduction, decreased GZMB expression in both KLRG1low (Fig. 4H) and KLRG1high phenotype P14 cells (Fig. 4I). These results also occurred in FOXO1 KO P14 cells, partially ablating the GZMBhigh phenotype observed in these cells (8) (Fig. 4 H and I). Therefore, TCF7 not only promotes memory-associated EOMES (6), but decreases KLRG1high cell abundance and plays an active role in extinguishing the cytotoxic effector program by reducing cellular GZMB.

FOXO1-Driven TCF7 Generates an Effector-to-Memory Continuum.

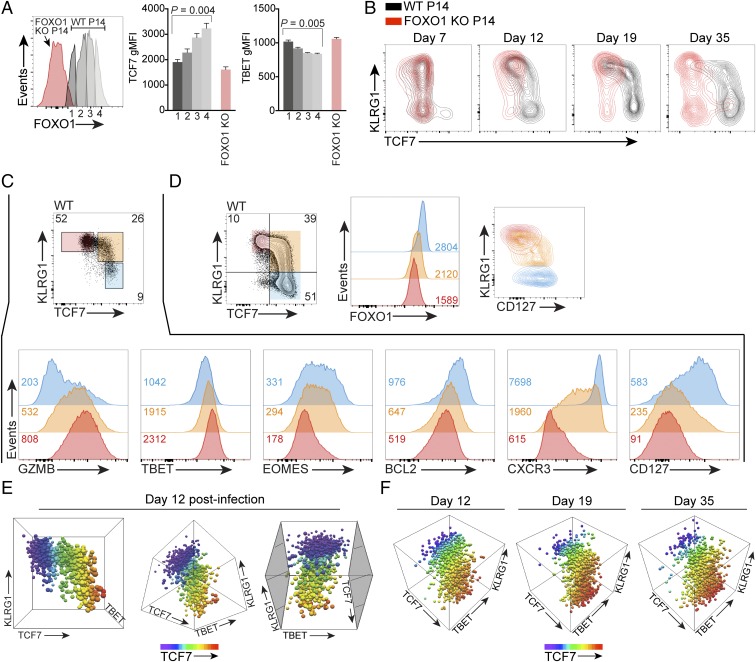

We next set out to determine how the FOXO1-TCF7 circuit affects postpeak effector vs. memory phenotype—the cells that are essential to protect against proximate pathogen rechallenge (32). By isolating four populations of increasing FOXO1 abundance in WT P14 T cells responding to LCMV-ARM at day 12 postinfection (Fig. 5A), we observed FOXO1 inversely correlated with TBET expression and positively correlated with TCF7 expression (P < 0.005 for FOXO1 vs. TBET and FOXO1 vs. TCF7, one-way ANOVA). Notably, the FOXO1 KO, which was coadoptively transferred alongside the WT P14 cells, exhibited the highest TBET and lowest TCF7 abundance (Fig. 5A; additional time points in Fig. S6).

Fig. 5.

FOXO1 establishes an effector-to-memory continuum. (A) A mixed transfer of a total of 1 × 104 WT and FOXO1 KO P14 cells was performed on day −1, followed by LCMV-ARM infection on day 0. (Left) Adoptively transferred WT P14 cells were gated into four subsets based on FOXO1 expression: these gates were labeled 1–4 and are depicted in grayscale. From the same transfer and immunostain, FOXO1 KO cells are depicted in red. The TBET and TCF7 gMFI was determined from WT P14 gates 1–4 and FOXO1 KO P14 T cells. Error bars indicate SEM, n = 3; P value from one-way ANOVA of gMFI of TCF7 or TBET in gates 1–4. (B) Adoptive transfer and infection as in A; TCF7 vs. KLRG1 in WT P14 and FOXO1 KO P14 cells on indicated day postinfection. (C and D) Single transfer of 1 × 104 WT P14 cells on day −1, followed by LCMV-ARM infection on day 0. (C) Color coding of the indicated TCF7 vs. KLRG1 populations in the dot plot corresponds to the three traces depicted in the histograms below, where Insets indicate gMFI. In dot plot, numbers indicate percentage of the population gated. (D, Left) Day 12 postinfection color-coded gates of TCF7/KLRG1 subsets in WT P14 cells. FOXO1 abundance (Center) and CD127/KLRG1 abundance (Right) for the gated populations at Left. All results in A–D observed in two additional experiments from days 12–19 postinfection. (E) Three-dimensional bubble plots of indicated protein abundance, day 12 postinfection P14 T cells; same dataset rotated from Left to Right; gray shading added to plot at Right to aid in visualization. EOMES abundance is proportional to bubble size, TCF7 relative abundance is further depicted by color spectrum. (F) As in E, but for indicated time points and without depiction of EOMES; from a different experiment than E. Results from B–D are from different experiments.

Fig. S6.

Kinetics of FOXO1-dependent effector-to-memory continuum. (A–F) A total of 1 × 104 (1:1 mix of WT P14 and FOXO1 KO P14) cells was transferred i.v. to WT hosts on day −1 and hosts were infected with LCMV-ARM on day 0. Data are from a different experiment from that in Fig. 5 A and C–E. (A and B) Day 12 postinfection. (A) A histogram of total WT P14 cells was subdivided into four levels of FOXO1 abundance (“1–4”) and displayed on the same histogram; FOXO1 KO cells from the same host were plotted in red (“KO”). At Right, the abundance of TCF7 and TBET in the four WT P14 FOXO1 subsets is plotted, as well as from the FOXO1 KO P14 cells. (B) Gates were established on TCF7 vs. KLRG1 populations (Left), and the abundance of indicated molecules was determined (Right); Inset is gMFI. Total FOXO1 KO P14 abundance of indicated molecule from same host is shown in gray. (C and D) As before, but for day 19 postinfection. (E and F) As before, but for day 35 postinfection. Fluorescently conjugated antibody mixtures were prepared independently for each time point; comparisons of absolute immunofluorescence values (i.e., gMFI) between days may not be meaningful.

We then wanted to determine the kinetics of TCF7 expression. We immunostained for TCF7 and KLRG1 from day 7 to day 35 postinfection (Fig. 5B); we observed a prominent, FOXO1-dependent TCF7+KLRG1+ population from day 12 to day 35 postinfection. Given that TCF7 expression is associated with memory differentiation, and KLRG1 with terminal differentiation, we decided to further characterize postinfection P14 cells by selecting three TCF7 vs. KLRG1 populations (Fig. 5 C and D, Left). First, we found that a gradient of FOXO1 expression across the three TCF7/KLRG1 populations was established (Fig. 5D, Center), which could not be easily discerned by CD127 expression alone (Fig. 5D, Right). In this context, FOXO1 was associated positively with an increasing memory signature (Fig. 5C; histograms of CD127, BCL2, EOMES) and decreasing effector signature (Fig. 5C, histograms of GZMB, TBET; additional time points in Fig. S6).

Previous studies established the role of TBET gradients in terminal effector vs. memory differentiation (20, 26). To determine the aspects of terminal effector vs. memory phenotypes that require FOXO1, we examined FOXO1 KO cells and isolated subsets based on increasing KLRG1, a correlate of TBET expression (20). In addition to a lack of TCF7 (shown Fig. 5B), in the absence of FOXO1, key phenotypic changes associated with KLRG1 expression were diminished or absent (Fig. S7). GZMB varied in these subsets, but by a lesser degree compared with WT cells (Fig. 5A), whereas the expression of EOMES and BCL2 was uniformly low across the spectrum of KLRG1 expression in FOXO1 KO T cells. In contrast, the amount of TBET and CXCR3 was still distinct for each of the subsets defined by KLRG1 expression (Fig. S7 C–E). Taken together with Fig. 5 A–D, these results demonstrate graded expression of FOXO1 is required to establish corresponding gradients of TCF7, EOMES, BCL2, and in part, effector-associated GZMB; this FOXO1-dependent regulation of molecules occurs in cells expressing low and high levels of KLRG1. We did not assess whether the gradient of FOXO1 controls differentiation decisions (i.e., whether a cell becomes KLRG1low or high).

Fig. S7.

Effector vs. memory phenotyping in the absence of FOXO1: TBET and CXCR3 vary with KLRG1 expression, but not EOMES or BCL2. Mixed transfer of a 1:1 mix of 1 × 104 total WT P14 and FOXO1 KO P14 cells at day −1, followed by LCMV-Armstrong infection on day 0. A FOXO1 KO P14 gate was established using a congenic marker on splenic cells, day 12 postinfection. (A and B) Three-dimensional bubble plots of indicated markers in WT and FOXO1 KO P14 T cells, TCF7 abundance depicted by color spectrum; same dataset rotated. (C) Three gates of KLRG1 expression on FOXO1 KO P14 cells were established as indicated by the colored boxes. (D) Representative samples of the populations in C analyzed by histogram; Inset is the geometric mean. (E) Average geometric mean for populations from C; n = 4; error bars are SEM; P value from one-way ANOVA; “ns” indicates not significant (value of P > 0.05). Results are representative of three experiments performed from day 12 to 19 postinfection.

To further illustrate this effector-to-memory continuum, we used 3D bubble plots and a color gradient to depict four parameters in day 12 antigen-specific P14 cells (Fig. 5E; the fourth parameter, EOMES, is denoted by bubble size). The three plots show the same dataset rotated to demonstrate specific aspects of the gradients of TCF7, TBET, EOMES, and cell surface KLRG1. We note that these populations have further gradients in BCL2 and GZMB (Figs. 3F and 5C and Fig. S6). In summary, our results add FOXO1 and TCF7 gradients as a countercurrent to the established gradient of TBET in the molecular programming of effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation. Additional 3D bubble plot time points are presented in Fig. 5F.

To put our findings into the context of other reports, we immunostained for CD27 and CD43 (Fig. S8): postinfection, pathogen-specific CD8+CD27−CD43− phenotype T cells have been reported to possess both effector and memory properties (32). TCF7 vs. KLRG1 immunostaining of postinfection CD27 vs. CD43 P14 subsets revealed that CD27−CD43− cells contain all three subsets of TCF7 vs. KLRG1 we described in Fig. 5C, including a predominant population of TCF7+KLRG1+ cells (Fig. S8). Since we have shown that TCF7 vs. KLRG1 subsets correlate with the effector-to-memory continuum identified in this report (Fig. 5 A–F and Fig. S6), the fact that the CD27−CD43− subset contains a spectrum of TCF7 vs. KLRG1 cells may explain their capacity for both persistence after infection and immediate effector function (32). Differentiation of WT P14 vs. FOXO1 KO P14 cells, as measured by CD27 and CD43 subsets, is presented in Fig. S8C.

Fig. S8.

CD27/CD43 correspondence to TCF7/KLRG1 and CD127/KLRG1 subsets of postinfection CD8+ T cell populations. Transfer of a 1:1 mix of 1 × 104 total WT P14 and FOXO1 KO P14 T cells at day −1, followed by LCMV-Armstrong infection on day 0. (A) Splenic WT P14 CD27/CD43 gating to establish three populations; Insets indicate gate percentage. TCF7 vs. KLRG1 expression of populations at Left are depicted in contour plots at Right. Black Inset indicates gate percentage, and red Inset indicates percentage of parent P14 gate. (B) CD27/CD43 subsets were identified first and then overlaid in CD127 vs. KLRG1 contour plots; from a different experiment from that in A. n = 2, experiment performed twice. (C) As in A, but from a separate experiment where WT and FOXO1 KO P14 T cells could be better distinguished. Representative experiment of two.

We wanted to further ascertain how TCF7 expression relates to CD44, another marker of CD8+ T cell differentiation. KLRG1+ cells express lower CD44 (24). On day 12 postinfection, we found that CD44 positively correlated with TCF7 and EOMES (Fig. S9A). The TCF7highCD44high population was GZMBlow (Fig. S9B). We then determined TCF7 and CD44 expression using the established CD127 vs. KLRG1 gating strategy (Fig. S9C). Applying the observations from Fig. S9 A–C, we determined by selectively gating on KLRG1 and CD44 expression, two populations with <20% or >90% TCF7 expression can be defined on day 12 postinfection (Fig. S9D). Using only CD44, it was also possible to identify TCF7high and TCF7low cells, but with much of the total P14 population excluded (Fig. S9E). Therefore, taking our earlier observations into account, our report establishes that day 5 to day 7 postinfection TCF7 expression correlates with an absence of TIM3 (Figs. 2 and 3), while day 12 TCF7 expression correlates with specific CD44 vs. KLRG1 subsets (Fig. S9). Although some postinfection cells are excluded, these gating strategies nevertheless allow straightforward and accurate cell surface identification of the TCF7high and TCF7low populations.

Fig. S9.

CD44 and/or KLRG1 allow partial identification of postpeak TCF7highKLRG1+ cells. A total of 1 × 104 congenically distinct P14 cells was transferred to WT hosts on day −1 and hosts were infected with LCMV-Armstrong on day 0. Cells were characterized on day 12 postinfection. (A) The highest CD44-expressing cells were as follows: (Left) KLRG1low+int, (Center) TCF7high, and (Right) EOMEShigh. Inset indicates Pearson correlation “r” for 1,000 events of the two variables displayed in each plot, where r = 1 is a perfect correlation and r = −1 is a perfect inverse correlation. (B) Three-dimensional bubble plots demonstrating the day 12 postinfection, WT P14 TCF7high cells are GZMBlow CD44high; color gradient indicates TCF7 expression. (C, Left) CD127 vs. KLRG1 analysis of CD44 vs. TCF7 expression. (Center) CD44 is primarily useful in distinguishing TCF7high cells in the KLRG1high populations, and (Right) CD127lowKLRG1high cells have lower CD44. (D) CD44 and KLRG1 gating scheme, which accounts for 60% of total KLRG1int+high cells, can enrich the TCF7pos population to 90%. (E) Subsets generated by taking the highest or lowest 10% of CD44 expression of KLRG1int+high cells also enriched for TCF7low vs. TCF7pos cells to >80%, but excluded more of the total KLRG1int+high population. All results depicted are representative of two experiments.

FOXO1/TCF7-Centric Model of CD8+ T Cell Differentiation.

We present a summary of our findings and hypotheses for CD8+ T cell effector vs. memory differentiation (Fig. S10). The day 5–7, postactivation TCF7high phenotype is associated with an absence of TIM3 expression, lower mTOR signaling, and fewer cells in S/G2 of the cell cycle; we hypothesize this is associated with FOXO1 nuclear localization, which drives postinfection TCF7 expression and reinforces sustained exit from the cell cycle. These TCF7high cells have increased memory-associated EOMES and BCL2 expression and diminished expression of GZMB, and TCF7 up-regulation is detectable before expression of CD127. In contrast, TCF7low cells express TIM3 on the cell surface from approximately day 5 to 6. TIM3 is first expressed before KLRG1, and then coexpressed on a subset of cells with KLRG1 (Fig. S1). We hypothesize TCF7low cells reflect nuclear exclusion of FOXO1, which enables sustained cellular proliferation, and a decreased opposition of terminal differentiation regulator TBET (11, 20). Past the peak of infection, a continuum of effector-to-memory cells exist (Fig. 5D), as represented here (Fig. S10) by the TCF7intKLRG1int population, which expresses intermediate quantities of FOXO1, TCF7, TBET, EOMES, and GZMB.

Fig. S10.

FOXO1/TCF7 regulate postinfection CD8+ T cell differentiation. FOXO1 determines TCF7 expression exclusively in postinfection CD8+ T cells. It is also required for the suppression of TBET, and thus, the FOXO1 gradient sets up the subsequent events that include differential expression of effector and memory factors. TCF7high cells exhibit lower GZMB, TBET, activation markers, mTOR signaling, and cells in S/G2. TCF7high-enriched cells are more likely to form CD127high memory precursors vs. TCF7low cells, and they have greater expansion potential and capacity to differentiate. A gradient of FOXO1 and TCF7 function counter to TBET to create a continuum of effector-to-memory phenotypes. This figure represents a summary of our experimental findings; we did not test specific models of T cell memory formation.

Discussion

The effector vs. memory programming of CD8+ T cells is of intense basic and applied research interest (2, 33). CD8+ T cells which express CD127 (IL7R) postinfection have increased memory potential (24), although CD127 (8, 34) itself is a cytokine receptor that does not directly regulate cell specification (35). On the contrary, the HMG box-containing TCF7 was shown to play an essential role in T cell memory (6, 7); this suggests TCF7 may be a more accurate predictor of T cell memory differentiation than CD127. Despite a significant population of TCF7high cells, we observed few of these cells expressed CD127 on days 5–6 postinfection.

TCF7 is activated via the WNT pathway; however, in memory T cells, there are conflicting reports concerning the role of the canonical WNT pathway member β-catenin (36, 37), with the potential for TCF7 to act independently of β-catenin, as occurs in LTI cells (38). TCF7 is required for CD8+ T cell recall responses, favors development of CD62Lhigh cells, and directly up-regulates the T-box transcription factor, EOMES (6). EOMES, in turn, has been shown to be key for memory CD8+ T cells to compete for survival and to respond to recall challenges (39).

Our previous studies determined that FOXO1 is essential to TCF7 expression in memory cells, and that the Tcf7 locus contained multiple FOXO1 genomic binding sites, as determined by ChIP-seq (8). However, this report determined that TCF7 in naive cells is FOXO1 independent, and therefore, the transfer of the regulation of Tcf7 expression to FOXO1 after antigen simulation is a critical molecular switch in T cell memory differentiation. We determined day 5 postinfection TCF7 expression after the adoptive transfer of 1 × 104 virus-specific T cells. Although this constitutes a precursor frequency higher than that of the naive repertoire (40), we note it is lower than that of recent studies examining early T cell effector/memory decisions resulting from the transfer of 106 or more antigen-specific T cells. Whether TCF7 is maintained in a small subset of postactivation cells or reexpressed selectively in memory precursor cells was not determined by our study.

Cellular proliferation is essential for certain differentiation programs (41). Extended proliferation has been associated with the KLRG1high fate (4), and terminal differentiation tends to occur after multiple infections (42). Conversely, FOXO proteins are positive regulators of cellular quiescence and inhibitors of cell cycle progression: they up-regulate cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (p15, p19, p27), and down-regulate cyclins and Rb phosphorylation in multiple cell types (43, 44). We found TIM3 to be a unique indicator of activation contained within a cluster of genes associated with early cellular proliferation, and past reports suggested enrichment of this cluster could presage T cell terminal differentiation (16). As predicted by informatics analysis, we found TIM3 expression to be the most accurate cell surface molecule tested to mark cells with low expression of TCF7 on day ∼5 postinfection. We further observed that TCF7low cells were more likely to be positive for mTOR targets and be in the S/G2 phases of the cell cycle, supporting a role for proliferation in terminal differentiation. Altogether, a key novelty of our report is that the TIM3low/TCF7high-associated gene expression program of decreased cellular proliferation precedes a drop in cell size, loss of CD25 expression, and induction of CD127, and identifies an early FOXO1-dependent memory phenotype population.

The BACH2 transcriptional repressor opposes AP-1, and Bach2 KO CD8+ T cells exhibit increased activation and KLRG1high terminal differentiation. We note that one of the most differentially and directly regulated transcripts in Bach2 KO CD8+ T cells was Havcr2/TIM3 (45, 46), and Roychoudhuri et al. (45) demonstrated that Bach2 retroviral transduction resulted in a decrease in light scattering of cells, similar to what we observed in the post-day 5 TIM3low/TCF7high population. We have shown Bach2 appears to be a direct FOXO1 target in CD8+ T cells (ref. 8 and GSE46525). These data are consistent with TIM3 marking cells with low FOXO1-driven BACH2 activity, and conversely, high AP-1 activity. Taking into account the similar CD8+ T cell numbers we observed despite forced TCF7 expression, these data suggest the decreased cell size and cell cycle positivity we found in TCF7high cells may occur do to upstream activity of FOXO1, BACH2, and other factors.

TBET is essential for cytotoxic T cell differentiation (25), retroviral TBET drives terminal effector differentiation (20), and a gradient of TBET expression is associated with the spectrum of differentiation states (26). We have shown here that FOXO1 also exists in a gradient in memory precursor-to-terminally differentiated cells, and drives a corresponding gradient of TCF7 in postinfection CD8+ T cells. Taken together with prior reports that FOXO1 opposes TBET (11), these data may place FOXO1 as a proximal regulator of terminal effector vs. memory precursor differentiation. We hypothesize extended stimulation, cell cycle progression, and inflammation results in prolonged FOXO1 nuclear exclusion, a lack of TBET opposition, and subsequent effector cell differentiation by TBET-mediated silencing of TCF7 as reported for CD4+ (47) and CD8+ T cells (48). A report of cellular activation driving FOXO1 nuclear exclusion and TCF7 diminution further highlights this circuit in driving B- and T cell differentiation decisions (49).

We found that key cytotoxic mediator GZMB, and thus immune cell effector function, is opposed by FOXO1-driven TCF7. This circuit couples effector function and terminal differentiation to cellular stimulation via pathogen/antigen receptor, or activating cytokine. While the reduction in GZMB was significant, we did not observe complete repression of GZMB. We anticipate other FOXO1-dependent mechanisms beyond TCF7 may also diminish GZMB expression, such as the aforementioned AP-1 repressor BACH2 (45, 46). We also found that enforced TCF7 expression reduced the abundance of the KLRG1high population, but did not entirely block its formation. These data demonstrate that, whereas TCF7 plays a role in maintaining memory precursor phenotype, memory precursor and KLRG1 differentiation are further controlled by FOXO1 itself and other downstream factors beyond TCF7. In summary, TCF7, downstream of FOXO1, exerts control over postactivation cellular differentiation to acute infection, contributing not only to diminishing GZMB, but also limiting terminal differentiation phenotype.

We observed that a gradient of FOXO1-driven TCF7 functions with the established TBET gradient to orchestrate a continuum of effector-to-memory phenotypes, with corresponding gradients of nearly every effector and memory molecule tested, including BCL2, GZMB, EOMES, CXCR3, CD127, and KLRG1. At day 12, we found CXCR3 to have intermediate expression on the TCF7+KLRG1+ population; others have reported CXCR3 as a marker of KLRG1high cells with an intermediate phenotype (3, 26): our data provide a transcription factor basis beyond TBET for the intermediate terminal effector vs. memory precursor phenotype of these cells. While our data confirm the existence of a continuum of effector-to-memory cell phenotypes, we have not established how specific cells transition within this gradient over time. This diversity of cell phenotypes may provide immunity to proximate pathogen rechallenge and enable clearance of semipersistent pathogens or those occupying difficult-to-access peripheral niches, both at the peak of the cellular response and beyond.

Materials and Methods

Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting.

Antibody staining performed with anti–4-1BB (17B5), anti-CD8α (53-6.7), anti-CD25 (PC61.5), anti-CD44 (IM7), anti-CD45.1 (A20), anti-CD45.2 (104), anti-CD62L (MEL-14), anti-CD69 (H1.2F3), anti-CD127 (A7R34), anti-CD244 (244F4), anti-GITR (DTA-1), anti-EOMES (Dan11mag), anti-KLRG1 (2F1), anti–LAG-3 (C9B7W), anti-TBET (4B10), anti–PD-1 (J43), anti–TIM-3 (RMT3-23), and anti-Vα2 (B20.1; all from eBioscience); anti-GZMB (MHGB05; Life Technologies); anti–phospho-ribosomal protein S6 (D57.2.2E), anti-TCF7 (C63D9; unconjugated or Alexa Fluor 488), and anti-FOXO1 (C29H4; Cell Signaling Technologies) on a BD LSR II Fortessa. In some cases, anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 or 647 was used to detect FOXO1 and TCF7 primary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific). DNA was determined with DRAQ5 following the manufacturer’s instructions (Biostatus). Cell sorting was performed on a BD FACS Aria II. Flow cytometry 3D data were analyzed/generated on FlowJo (Tree Star Software). BrdU assessment performed according to manufacturer’s instructions (BD Pharmingen).

Mice, Infection, and Adoptive T Cell Transfers.

Unless indicated, C57BL/6J mice were used as host mice. Mice were bred and housed in specific pathogen-free conditions in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Guidelines of the University of California, San Diego. Foxo1f/f (50), dLck-cre+/− (51), P14 TCR-transgenic (15), or ID3GFP+/− mice (18), all backcrossed to C57BL/6, were bred/used as described. Foxo1f/f/dLck-cre+/− are referred to in this report as “FOXO1 KO,” and P14+/− TCR-transgenic CD8+ T cells are referred to as “P14.” Single-cell suspensions of spleens were generated by teasing between frosted slides, hypotonic RBC lysis, and passage through 70-μm strainer. Adoptive transfers of P14 cells were performed by enumerating P14 cells and resuspending allowing adoptive transfer via 200-μL tail vein injection. Acute infections were performed with 2 × 105 pfu of LCMV-ARM i.p. ID3GFP+/− mice/P14 cells behave similarly to WT (18, 52) and were used for some phenotypic experiments. For Fig. S3, splenocytes from P14 donor mice were depleted of CD44high cells using anti-CD44/magnetic beads before adoptive transfer (Miltenyi Biotec).

Tcf7 Retroviral Transduction.

Bicistronic retroviral vector MigR1 expressing WT TCF7 was obtained from Avinash Bhandoola, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda (13). Retroviruses were packaged by transient transfection of 293T cells with the retroviral vector along with pCLeco as described (53). For retroviral transduction of antigen-specific P14 cells, naive WT or FOXO1 KO P14 cells purified by negative selection (Miltenyi Biotec) were activated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 plus 100 U/mL IL-2 for 18 h, spinfected with control or TCF7-expressing retrovirus with 8 μg/mL polybrene, and incubated 48 h at 37 °C. GFP+ cells were sorted and transferred into recipients (5–20 × 103 cells per mouse), and after 24 h infected with 5 × 105 pfu of LCMV-ARM.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the S.M.H. and A.W. Goldrath laboratories for comments, suggestions, and reagents; Avinash Bhandoola for the TCF7 retroviral construct; and Mark P. Rubinstein, Martin H. Stradner, Cédric Auffray, and Bruno Martin for manuscript discussions. A.L.D. was supported by NIH Grant F32AI082933, the UCSD Cancer Biology Fellowship, and the Goldrath laboratory. A.D. and C.-Y.L. were supported by Grant R01AI103440 from the NIH (to S.M.H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1618916114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. Memory CD8 T-cell differentiation during viral infection. J Virol. 2004;78:5535–5545. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.5535-5545.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang JT, Wherry EJ, Goldrath AW. Molecular regulation of effector and memory T cell differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:1104–1115. doi: 10.1038/ni.3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaech SM, Cui W. Transcriptional control of effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:749–761. doi: 10.1038/nri3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarkar S, et al. Functional and genomic profiling of effector CD8 T cell subsets with distinct memory fates. J Exp Med. 2008;205:625–640. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerlach C, et al. One naive T cell, multiple fates in CD8+ T cell differentiation. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1235–1246. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou X, et al. Differentiation and persistence of memory CD8+ T cells depend on T cell factor 1. Immunity. 2010;33:229–240. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeannet G, et al. Essential role of the Wnt pathway effector Tcf-1 for the establishment of functional CD8 T cell memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:9777–9782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914127107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hess Michelini R, Doedens AL, Goldrath AW, Hedrick SM. Differentiation of CD8 memory T cells depends on Foxo1. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1189–1200. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim MV, Ouyang W, Liao W, Zhang MQ, Li MO. The transcription factor Foxo1 controls central-memory CD8+ T cell responses to infection. Immunity. 2013;39:286–297. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tejera MM, Kim EH, Sullivan JA, Plisch EH, Suresh M. FoxO1 controls effector-to-memory transition and maintenance of functional CD8 T cell memory. J Immunol. 2013;191:187–199. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao RR, Li Q, Gubbels Bupp MR, Shrikant PA. Transcription factor Foxo1 represses T-bet-mediated effector functions and promotes memory CD8+ T cell differentiation. Immunity. 2012;36:374–387. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yui MA, Rothenberg EV. Developmental gene networks: A triathlon on the course to T cell identity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:529–545. doi: 10.1038/nri3702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber BN, et al. A critical role for TCF-1 in T-lineage specification and differentiation. Nature. 2011;476:63–68. doi: 10.1038/nature10279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willinger T, et al. Human naive CD8 T cells down-regulate expression of the WNT pathway transcription factors lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1 and transcription factor 7 (T cell factor-1) following antigen encounter in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2006;176:1439–1446. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pircher H, Bürki K, Lang R, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Tolerance induction in double specific T-cell receptor transgenic mice varies with antigen. Nature. 1989;342:559–561. doi: 10.1038/342559a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Best JA, et al. Immunological Genome Project Consortium Transcriptional insights into the CD8+ T cell response to infection and memory T cell formation. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:404–412. doi: 10.1038/ni.2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He B, et al. CD8+ T cells utilize highly dynamic enhancer repertoires and regulatory circuitry in response to infections. Immunity. 2016;45:1341–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang CY, et al. The transcriptional regulators Id2 and Id3 control the formation of distinct memory CD8+ T cell subsets. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1221–1229. doi: 10.1038/ni.2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ji Y, et al. Repression of the DNA-binding inhibitor Id3 by Blimp-1 limits the formation of memory CD8+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1230–1237. doi: 10.1038/ni.2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joshi NS, et al. Inflammation directs memory precursor and short-lived effector CD8+ T cell fates via the graded expression of T-bet transcription factor. Immunity. 2007;27:281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Araki K, et al. mTOR regulates memory CD8 T-cell differentiation. Nature. 2009;460:108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature08155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pollizzi KN, et al. mTORC1 and mTORC2 selectively regulate CD8+ T cell differentiation. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:2090–2108. doi: 10.1172/JCI77746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayer C, Grummt I. Ribosome biogenesis and cell growth: mTOR coordinates transcription by all three classes of nuclear RNA polymerases. Oncogene. 2006;25:6384–6391. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaech SM, et al. Selective expression of the interleukin 7 receptor identifies effector CD8 T cells that give rise to long-lived memory cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1191–1198. doi: 10.1038/ni1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sullivan BM, Juedes A, Szabo SJ, von Herrath M, Glimcher LH. Antigen-driven effector CD8 T cell function regulated by T-bet. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15818–15823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2636938100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joshi NS, et al. Increased numbers of preexisting memory CD8 T cells and decreased T-bet expression can restrain terminal differentiation of secondary effector and memory CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:4068–4076. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalia V, et al. Prolonged interleukin-2Ralpha expression on virus-specific CD8+ T cells favors terminal-effector differentiation in vivo. Immunity. 2010;32:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McFarland HI, Nahill SR, Maciaszek JW, Welsh RM. CD11b (Mac-1): A marker for CD8+ cytotoxic T cell activation and memory in virus infection. J Immunol. 1992;149:1326–1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tiemessen MM, et al. The nuclear effector of Wnt-signaling, Tcf1, functions as a T-cell-specific tumor suppressor for development of lymphomas. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Germar K, et al. T-cell factor 1 is a gatekeeper for T-cell specification in response to Notch signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:20060–20065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110230108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heng TS, Painter MW. Immunological Genome Project Consortium The Immunological Genome Project: Networks of gene expression in immune cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1091–1094. doi: 10.1038/ni1008-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olson JA, McDonald-Hyman C, Jameson SC, Hamilton SE. Effector-like CD8+ T cells in the memory population mediate potent protective immunity. Immunity. 2013;38:1250–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Couzin-Frankel J. Breakthrough of the year 2013. Cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2013;342:1432–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.342.6165.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kerdiles YM, et al. Foxo1 links homing and survival of naive T cells by regulating L-selectin, CCR7 and interleukin 7 receptor. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:176–184. doi: 10.1038/ni.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hand TW, Morre M, Kaech SM. Expression of IL-7 receptor alpha is necessary but not sufficient for the formation of memory CD8 T cells during viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11730–11735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705007104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prlic M, Bevan MJ. Cutting edge: β-Catenin is dispensable for T cell effector differentiation, memory formation, and recall responses. J Immunol. 2011;187:1542–1546. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao DM, et al. Constitutive activation of Wnt signaling favors generation of memory CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:1191–1199. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Q, et al. T cell factor 1 is required for group 2 innate lymphoid cell generation. Immunity. 2013;38:694–704. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Banerjee A, et al. Cutting edge: The transcription factor eomesodermin enables CD8+ T cells to compete for the memory cell niche. J Immunol. 2010;185:4988–4992. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Badovinac VP, Haring JS, Harty JT. Initial T cell receptor transgenic cell precursor frequency dictates critical aspects of the CD8+ T cell response to infection. Immunity. 2007;26:827–841. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ueno H, Nakajo N, Watanabe M, Isoda M, Sagata N. FoxM1-driven cell division is required for neuronal differentiation in early Xenopus embryos. Development. 2008;135:2023–2030. doi: 10.1242/dev.019893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wirth TC, et al. Repetitive antigen stimulation induces stepwise transcriptome diversification but preserves a core signature of memory CD8+ T cell differentiation. Immunity. 2010;33:128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katayama K, Nakamura A, Sugimoto Y, Tsuruo T, Fujita N. FOXO transcription factor-dependent p15(INK4b) and p19(INK4d) expression. Oncogene. 2008;27:1677–1686. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmidt M, et al. Cell cycle inhibition by FoxO forkhead transcription factors involves downregulation of cyclin D. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7842–7852. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.7842-7852.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roychoudhuri R, et al. BACH2 regulates CD8+ T cell differentiation by controlling access of AP-1 factors to enhancers. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:851–860. doi: 10.1038/ni.3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roychoudhuri R, et al. BACH2 represses effector programs to stabilize Treg-mediated immune homeostasis. Nature. 2013;498:506–510. doi: 10.1038/nature12199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oestreich KJ, Huang AC, Weinmann AS. The lineage-defining factors T-bet and Bcl-6 collaborate to regulate Th1 gene expression patterns. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1001–1013. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dominguez CX, et al. The transcription factors ZEB2 and T-bet cooperate to program cytotoxic T cell terminal differentiation in response to LCMV viral infection. J Exp Med. 2015;212:2041–2056. doi: 10.1084/jem.20150186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin WH, et al. Asymmetric PI3K signaling driving developmental and regenerative cell fate bifurcation. Cell Rep. 2015;13:2203–2218. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.10.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paik JH, et al. FoxOs are lineage-restricted redundant tumor suppressors and regulate endothelial cell homeostasis. Cell. 2007;128:309–323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang DJ, et al. Selective expression of the Cre recombinase in late-stage thymocytes using the distal promoter of the Lck gene. J Immunol. 2005;174:6725–6731. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Monticelli LA, et al. Transcriptional regulator Id2 controls survival of hepatic NKT cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:19461–19466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908249106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xue HH, et al. Serine phosphorylation of Stat5 proteins in lymphocytes stimulated with IL-2. Int Immunol. 2002;14:1263–1271. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]